Abstract

Background:

The milk casein-derived biologically active tripeptides, isoleucyl-prolyl-proline (Ile-Pro-Pro) and valyl-prolyl-proline (Val-Pro-Pro), have documented antihypertensive effect probably related to reduced angiotensin formation. It has been suggested that these tripeptides may reduce arterial stiffness and improve endothelial function. Our aim was to evaluate whether the milk-based drink containing Ile-Pro-Pro and Val-Pro-Pro influence arterial stiffness, measured as augmentation index (AIx), and endothelial function in man.

Methods:

In a double-blind parallel group intervention study, 89 hypertensive subjects received daily peptide milk containing a low dose of tripeptides (5 mg/day) for 12 weeks and a high dose (50 mg/day) for the following 12 weeks, or a placebo milk drink to titrate the dose–response effect. Arterial stiffness was assessed by pulse wave analysis at the beginning and end of each intervention period. Endothelial function was tested by examining pulse wave reflection response to sublingual nitroglycerin and salbutamol inhalation. Blood pressure was measured by using office and 24-h ambulatory blood pressure measurement.

Results:

At the end of the second intervention period, AIx decreased significantly in the peptide group compared with the placebo group (peptide group −1.53% (95% confidence interval (CI) −2.95 to −0.12), placebo group 1.20% (95% CI 0.09–2.32), P=0·013). No change in endothelial function index was observed (peptide group 0.02 (95% CI −0.06 to 0.08), placebo group 0.04 (95% CI −0.04 to 0.12), P=0.85). There were no statistically significant differences between the effects of the peptide and placebo treatment on office and 24-h ambulatory blood pressure.

Conclusions:

Long-term treatment with Lactobacillus helveticus-fermented milk containing bioactive peptides reduces arterial stiffness expressed as AIx in hypertensive subjects.

Keywords: bioactive peptides, hypertension, arterial stiffness, endothelial function, pulse wave analysis, aortic augmentation index

Introduction

The milk-derived tripeptides isoleucyl-prolyl-proline (Ile-Pro-Pro) and valyl-prolyl-proline (Val-Pro-Pro) lower blood pressure and attenuate the development of hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats after long-term oral intake (Sipola et al., 2001, 2002a). The mechanisms behind the antihypertensive effects are partly unknown, but inhibition of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system seems to be involved (Masuda et al., 1996; Nakamura et al., 1996; Sipola et al., 2002a). Milk-derived peptides improve vascular response in vitro probably through stimulation of endothelial nitric oxide (NO) release (Sipola et al., 2002b). It has been shown in experimental and clinical trials that the tripeptides Ile-Pro-Pro and Val-Pro-Pro can be absorbed at least partly from the intestine (Foltz et al., 2007; Jauhiainen et al., 2007b). Blood pressure-lowering effects of milk products containing Ile-Pro-Pro and Val-Pro-Pro tripeptides have been shown in several clinical trials (Seppo et al., 2003; Jauhiainen et al., 2005) and a meta-analysis of 12 randomized controlled trials found that the ingestion of tripeptides Ile-Pro-Pro and Val-Pro-Pro for 4–21 weeks decreases systolic blood pressure by 4.8 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure by 2.2 mm Hg (Xu et al., 2008). Another meta-analysis by Pripp (2008) included intervention studies on both milk tripeptides and other peptides derived from food, and found a significant effect on systolic blood pressure of −5.1 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure of −2.4 mm Hg. By contrast, two recent studies suggested that milk tripeptides have no significant blood pressure-lowering effects (Engberink et al., 2008; van der Zander et al., 2008). The antihypertensive effects of milk-derived peptides have recently been reviewed (FitzGerald et al., 2004; López-Fandiño et al., 2006; Hong et al., 2008; Korhonen 2009).

Impaired endothelial NO synthesis, endothelial dysfunction, is one of the central elements in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, and is strongly related to hypertension and dyslipidemia (Panza et al., 1990; Vapaatalo and Mervaala, 2001). An association between endothelial dysfunction and arterial stiffness has recently been shown (Wilkinson et al., 2002b). Arterial stiffness is an independent predictor of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality and has been associated with hypertension (Boutouyrie et al., 2002). Earlier studies have suggested that milk tripeptides may improve arterial stiffness (Jauhiainen et al., 2007a) and vascular endothelial function in hypertensive subjects (Hirota et al., 2007).

Our purpose was to examine whether a long-term intervention with a milk product fermented with Lactobacillus helveticus to produce Ile-Pro-Pro and Val-Pro-Pro has an impact on arterial stiffness and endothelial function, in addition to its documented blood pressure-lowering effects.

Materials and methods

Subjects

Eighty-nine subjects participated in this double-blind randomized placebo-controlled parallel group study. The inclusion criteria were systolic blood pressure between 140 and 155 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure between 85 and 99 mm Hg, and age between 25 and 55 years. Exclusion criteria were smoking, blood pressure-lowering medication, secondary hypertension, unstable coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, malignant diseases, alcohol abuse, milk allergy and pregnancy. A total of 396 mildly to moderately hypertensive subjects responded to the recruitment in the Helsinki area. Of the 216 subjects who entered the 4-week run-in period, 122 did not fulfill the inclusion criteria during the period when 24-h ambulatory blood pressure recording was used and were excluded. One subject from the peptide group and four from the placebo group withdrew from the study right after the run-in period. A total of 89 subjects (54 males and 35 females) were included in the final analysis.

Design

After the 4-week run-in period, subjects were randomly allocated to a peptide group that received a L. helveticus-fermented milk product containing bioactive peptides or to a placebo group that received a placebo drink with similar appearance and taste. To test the dose–response effect, two different peptide concentrations were used. During the first 12 weeks of intervention, the subjects were given daily 200 ml of the test product with low doses of the tripeptides (see below) or placebo. For the following 12 weeks, the peptide group received two daily 200 ml doses of the test product containing a high concentration (see below) of the tripeptides or placebo drink. During the run-in period, the subjects received a daily 200 ml dose of a commercial fermented milk product different to the peptide product or the placebo product to become familiar with the trial procedure.

The subjects were asked to maintain their normal lifestyle and dietary habits, and register their daily use of the products and any adverse events. Arterial stiffness and endothelial function testing was performed at the beginning and at the end of each intervention period by an experienced clinician (MR). The entire study was conducted in a double-blinded manner. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Joint Authority for the Hospital District of Helsinki and Uusimaa. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Test products

The peptide test product during the first 12-week intervention period was L. helveticus LBK-16 H fermented milk with a low concentration of peptides (Ile-Pro-Pro 1.2 mg/100 g and Val-Pro-Pro 1.3 mg/100 g) (Valio Ltd., Helsinki, Finland) measured according to Masuda et al. (1996) During the following 12-week period, a peptide product with higher concentrations was given (Ile-Pro-Pro 5.8 mg/100 g and Val-Pro-Pro 6.6 mg/100 g). More detailed data on the product composition are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Nutritional composition of the peptide product and the control product

| Peptide product | Control product | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First intervention period | Second intervention period | First intervention period | Second intervention period | |

| Energy (kJ/100 g) | 320 | 320 | 260 | 260 |

| Protein (g/100 g) | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| Fat (g/100 g) | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Carbohydrate (g/100 g) | 15 | 15 | 12 | 12 |

| Calcium (mg/100 g) | 150 | 150 | 84 | 84 |

| Potassium (mg/100 g) | 240 | 240 | 130 | 130 |

| Sodium (mg/100 g) | 35 | 35 | 27 | 27 |

| Ile-Pro-Pro (mg/100 g) | 1.2 | 5.8 | — | — |

| Val-Pro-Pro (mg/100 g) | 1.3 | 6.6 | — | — |

Arterial stiffness

Arterial stiffness was assessed by pulse wave analysis (SphygmoCor; AtCor Medical, Sydney, Australia). Blood pressure was recorded twice in the dominant arm in a lying position (Omron M4, Omron Matsusaka, Japan). Radial artery waveforms were recorded with a high-fidelity micromanometer (SPC-301; Millar Instruments, Houston, TX, USA) from the wrist of the dominant arm. A generalized validated transfer function was then used to generate a corresponding central (ascending aortic) waveform (Chen et al., 1997). The aortic augmentation index (AIx) was calculated as the augmentation of the aortic systolic blood pressure by the reflected pulse wave, expressed as a percentage of the aortic pulse pressure. AIx was adjusted to a heart rate of 75 beats/min calculated by the software that was used in the analyses (Wilkinson et al., 2000). The time to return of the reflected wave (Tr) was calculated as the time from the beginning of the derived aortic systolic pressure waveform to the inflection point. Tr can be used as a substitute for pulse wave velocity (a higher pulse wave velocity will result in a shorter Tr) (London et al., 1992). Subjects were studied after a minimum 12-h fast in the morning between 0700 to 1000 hours and were asked to refrain from alcohol consumption and heavy exercise on the day before measurements. Studies were conducted in a quiet room after a 15-min rest. All measurements were performed by the same trained physician (MR).

Endothelial function

Vascular endothelial function was studied using the pulse wave analysis method (Wilkinson et al., 2002a). This method examines the effects of an adrenergic β2-agonist salbutamol and nitroglycerin on the AIx. The reduction of AIx induced by inhalation of salbutamol reflects activation of the L-arginine–NO pathway in endothelial cells, whereas the response to nitroglycerin is an endothelium-independent measure of vasodilatory capacity. After the baseline recordings of AIx, a 500 μg tablet of nitroglycerin (Nitro, Orion, Espoo, Finland) was administered sublingually. AIx was measured after 3, 5, 10, 15 and 20 min. A second baseline recording of AIx was made 60 min later, and immediately after that two 200 μg inhalations of salbutamol (Ventoline Evohaler, GlaxoSmithKline, London, UK) were given with a spacer device (Volumatic, GlaxoSmithKline). AIx was measured 3, 5, 10, 15 and 20 min later. The responses to nitroglycerin and salbutamol were defined as the maximum change from the respective baseline after drug administration. An endothelial function index was calculated as the AIx change induced by salbutamol divided by the AIx change induced by nitroglycerin, expressed as a percentage.

Twenty-four-h ambulatory blood pressure measurement

At the beginning and end of the intervention periods, blood pressure was measured with an automatic 24-h blood pressure recorder (SpaceLab ABP 90207, Redmont, CA, USA) four times an hour during the daytime and twice an hour during the night. The measurement was accepted if at least 80% of the readings were successful; otherwise, the measurement was repeated.

Blood sampling

Blood samples were drawn at the beginning and at the end of the two interventions (three times during the study) after an overnight (12-h) fast. Total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglycerides were measured enzymatically, and low-density lipoprotein was calculated by the Friedewald equation (Friedewald et al., 1972). C-reactive protein was determined using a turbidimetric immunoassay (Wako Chemicals, Neuss, Germany) with a detection limit of 0.1 mg/l. At every visit, the subjects were weighed and body mass index was calculated. No significant changes were seen during the study periods in these variables.

Statistical analysis

Analysis was performed according to the intention-to-treat principle with the last-observation-carried-forward approach. The results were expressed as the mean or median, s.d. or interquartile range, and 95 percent confidence intervals (95% CIs). Statistical comparison of within-groups in outcome measurements was performed using paired t-test. The changes in measurements between groups were analyzed using analysis of covariance with the baseline value as the covariable.

Role of the funding source

The study was financially supported by the Finnish Funding Agency for Technology and Innovations (TEKES) and The Academy of Finland. The funding source had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation or writing of the manuscript.

Results

The clinical characteristics of the subjects at baseline are presented in Table 2. The subjects reported that they did not change their dietary intake or physical activity during the study, and their compliance was excellent. These variables were followed by recording forms.

Table 2.

Baseline demographic and clinical data at baseline

| Placebo (N=44) | Peptide (N=45) | |

|---|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 27 (61) | 27 (60) |

| Age, years, mean (s.d.) | 49 (5) | 49 (5) |

| Body mass index, kg/cm2, mean (s.d.) | 28.5 (3.9) | 27.6 (3.6) |

| Waist–hip ratio (s.d.) | 0.94 (0.08) | 0.90 (0.10) |

| Blood pressure, mmHg, mean (s.d.) | ||

| Systolic | 154.6 (13.9) | 151.3 (14.8) |

| Diastolic | 94.2 (8.8) | 95.2 (12.2) |

| Mean arterial pressure, mean (s.d.) | 113.8 (9.8) | 116.8 (10.2) |

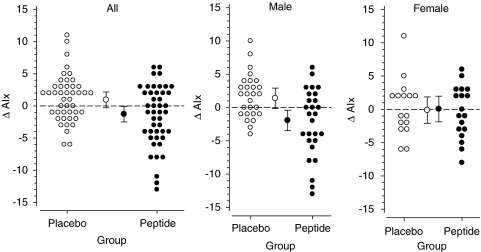

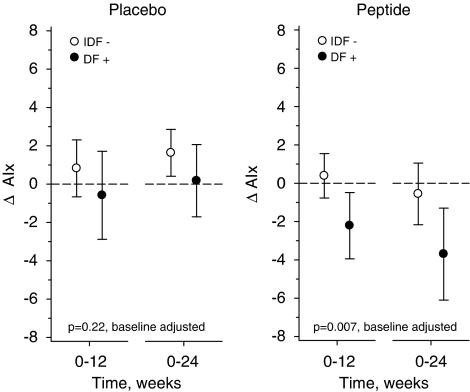

No significant changes in the hemodynamic parameters were observed after 12 weeks of low-dose treatment. The hemodynamic characteristics at baseline and the changes to the end of the high-dose treatment (24 weeks) are presented in Table 3. At week 24, AIx was decreased significantly from the baseline (P=0.013) in the peptide group versus the placebo (Table 3, Figure 1). A subgroup analysis for further studies, males versus females, was also performed. The changes between the groups were more pronounced in males. At 24 weeks, the baseline AIx values had decreased significantly in males in the peptide group versus the placebo (peptide −2.30% (95% CI −4.31 to −0.28), placebo 1.74% (95% CI 0.44 to 3.04), P=0.004). In contrast, the changes of AIx in women were similar in both groups (peptide −0.39% (95% CI −2.34 to 1.56), placebo 0.35% (95% CI −1.77 to 2.48), P=0.90) (Figure 1). When analyzing the effects in subjects who fulfilled the International Diabetes Federation criteria for metabolic syndrome (MS) (subjects had central obesity, hypertension, and either reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol or raised triglycerides level. Fasting blood glucose values were not measured and therefore probably only part of the MS subjects was identified), results showed that the difference between the genders could be explained by MS (Figure 2). The treatment effect was highly significant in subjects with MS but not in subjects who did not fulfill these criteria.

Table 3.

Hemodynamic characteristics in the beginning of the intervention and change to 24 weeks

| Baseline | Change to 24 weeks | P-valuea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo mean (s.d.) | Peptide mean (s.d.) | Placebo mean (95% CI) | Peptide mean (95% CI) | ||

| Aix, %-units | 20.0 (8.4) | 24.3 (8.4) | 1.20 (0.09 to 2.32) | −1.53 (−2.95 to −0.12) | 0.013 |

| AIx GTN, %-units | −3.82 (9.26) | 0.07 (9.73) | 1.20 (−0.74 to 3.15) | 0.33 (−1.31 to 1.98) | 0.79 |

| AIx salbutamol, %-units | 7.95 (11.24) | 11.71 (10.80) | 0.82 (−1.12 to 2.75) | −0.64 (−2.41 to 1.12) | 0.61 |

| Tr, ms | 147 (8) | 143 (9) | −1.9 (−3.7 to −0.2) | 0.5 (−1.1 to 2.1) | 0.13 |

| EFI | 0.31 (0.16) | 0.32 (0.16) | 0.04 (−0.04 to 0.12) | 0.02 (−0.06 to 0.08) | 0.85 |

| Office blood pressure, mm Hg | |||||

| Systolic | 151 (15) | 155 (14) | −2.6 (−5.7 to 0.6) | −4.6 (−8.4 to −0.8) | 0.58 |

| Diastolic | 95 (12) | 94 (9) | −1.7 (−3.6 to 0.08) | −3.7 (−6.1 to −1.3) | 0.14 |

| Twenty-four-h blood pressure, mm Hg | |||||

| Systolic | −1.4 (−4.0 to 1.3) | −4·6 (−6.9 to −2.3) | P=0.22 | ||

| Diastolic | −1.5 (−3.3 to 0.3) | −2.7 (−4.2 to −1.2) | P=0.55 | ||

Abbreviations: AIx, the aortic augmentation index; CI, confidence interval; EFI, an endothelial function index; Tr, the time to return of the reflected wave.

Analysis of covariance with body mass index and baseline measure as covariates.

Figure 1.

Augmentation index (AIx) change to 24 weeks. Bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 2.

The changes of augmentation index (AIx) to 24 weeks on subjects with (IDF+) or without metabolic syndrome (IDF−) according to the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) definition for metabolic syndrome.

Tr increased from the baseline value in the peptide group and decreased in the placebo group (Table 3). The difference between the groups was not significant. However, when comparing males only, the difference between the groups was significant (peptide 1.7 ms (95% CI −0.44 to 3.9), placebo −2.1 ms (95% CI −4.1 to −0.1), P=0.022). In females, no difference from the baseline level was observed (peptide −1.4 ms (95% CI −3.7 to 0.9), placebo −1.6 ms (95% CI −5.2 to 1.9), P=0.58).

There were no differences between the groups in endothelial function test (endothelial function index) (Table 3). No differences were seen between males and females (males: peptide −0.012 (95% CI −0.10 to 0.08), placebo 0.08 (95% CI −0.03 to 0.20, P=0.39) (females: peptide 0.06 (95% CI −0.05 to 0.16), placebo −0.02 (95% CI −0.16 to 0.11), P=0.17).

Systolic and diastolic blood pressures decreased in both groups from the baseline to 24 weeks (Table 3). Compared with the placebo group, both systolic and diastolic office blood pressure values decreased by 2.0 mm Hg in the peptide group. Similarly, 24-h ambulatory systolic and diastolic blood pressure decreased in the peptide group by 3.2 and 1.2 mm Hg, respectively, compared with the placebo group. However, the differences between the groups did not reach statistical significance.

Serum total cholesterol values tended to be lower in the peptide group (total cholesterol; peptide group −0.21 mmol/l (95% CI −0.43 to 0.01), placebo group 0.034 mmol/l (95% CI −0.16 to 0.23), P=0.077, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; peptide group −0.13 mmol/l (95% CI −0.31 to 0.052), placebo group 0.018 mmol/l (95% CI −0.16 to 0.19), P=0.17). No significant differences between the groups were seen in the change of C-reactive protein levels: (peptide group −0.14 (95% CI −0.77 to 0.49), placebo group 0.026 (95% CI −0.43 to 0.48), P=0.86).

Discussion

Arterial stiffness is an independent predictor of cardiovascular mortality in hypertensive subjects (Laurent et al., 2001; Narkiewicz et al., 2007). This study shows that in addition to its established antihypertensive effects, bioactive peptide-containing milk drinks improve arterial stiffness measured by analysis of pulse wave reflection in hypertensive subjects. This finding is in line with our earlier study, which suggested that milk tripeptides improve arterial stiffness calculated as an aortic arterial stiffness index in hypertensive subjects (Jauhiainen et al., 2007a). In this study, the treatment was more effective with subjects who fulfilled the International Diabetes Federation criteria for MS. The result is important, because a 10% elevation in AIx increases the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events by 28% in patients with coronary artery disease and patients with MS are a high-risk group (Chirinos et al., 2005).

Compared with the placebo group, systolic and diastolic blood pressure in 24-h readings decreased in the peptide group by 3.2 and 1.2 mm Hg, respectively. The difference between the groups was not statistically significant, but it may have clinical significance, because it has been estimated that a decrease in systolic blood pressure by 2 mm Hg would reduce the risk for stroke and myocardial infarction by ∼4% (Selmer et al., 2000).

Hirota et al. (2007) used plethysmography as an index of vascular endothelial function and reported that milk tripeptides improved the vascular endothelial dysfunction. By contrast, our finding that reduction of pulse wave reflection induced by β2-adrenergic stimulation was not significantly improved suggests indirectly that improved endothelial NO release capacity is not the mechanism by which L. helveticus-fermented milk exerts its favorable circulatory effects.

Structural arterial stiffening is a slow process caused by changes in the extracellular matrix of the arterial walls. As the present intervention lasted for 24 weeks, it is unlikely that any major modifications of the elastic properties of the arterial walls had occurred. A more likely mechanism behind the finding is reduced functional arterial tone. The fact that we detected an effect on Tr suggests that the effect is not confined to increased peripheral resistance in the arterioles, but rather that medium-sized conduit arteries are also affected.

Milk protein-derived peptides (α-lactorphin, β-lactorphin and Ile-Pro-Pro) have beneficial effects on arterial tone in spontaneously hypertensive rat in vitro (Sipola et al., 2002b; Jäkälä et al., 2009). The effect of Ile-Pro-Pro and Val-Pro-Pro seems to be related to ACE-inhibitory activity (Ahimastos et al., 2005; López-Fandiño et al. 2006; Hong et al., 2008).

Another mechanism that must be considered is the fact that the functional stiffness of the large arteries is affected by the distensive effect that blood pressure exerts on the arterial walls (O'Rourke and Gallagher, 1996). Given that both systolic and diastolic blood pressure diminished in the intervention group, AIx reduction could to some extent be explained by lowered blood pressure. In any case, regardless of the underlying mechanism, reduced arterial stiffness is beneficial to cardiovascular health by reducing cardiac afterload and central systolic augmentation.

AIx values could also be influenced by cholesterol and C-reactive protein levels (Libby et al., 2000; Venugopal et al., 2002; Verma et al., 2002). In this study, the changes in these markers were minor and cannot explain the finding. This study could not show an effect of bioactive tripeptides on vasodilatation caused by the pharmacological stimulation of endothelial NO release. However, as basal NO release by the endothelium is an important determinant of pulse wave reflection, it can be speculated that the bioactive peptides improve basal endothelial NO release, although the maximal capacity of NO release is unaffected.

In addition to these suggested mechanisms, the positive effect on arterial stiffness could also be influenced by the mineral composition of peptide milk. Calcium has been shown to enhance vasorelaxation in experimental trials (Mäkynen et al., 1996; Jones et al., 1997). Potassium and magnesium also have beneficial effects on vascular function (Mervaala et al., 1994; Mäkynen et al., 1995; Tolvanen et al., 1998). On the other hand, the electrolyte concentrations did not differ markedly between the test and placebo drinks.

When evaluating the strengths and limitations of this study, the authors see many strengths. The number of recruited subjects was quite marked, about 400. Of them, more than half were selected for the 4-week run-in period, during which again about half were excluded on the basis of strict criteria of hypertension in an ambulatory 24-h blood pressure registration. Thus, the final material (89 subjects) was quite homogeneous and regarded as moderately hypertensive. The subjects were motivated, seemed to follow the instructions carefully and not to change their living habits (nutrition intake, physical activity), which were recorded. Daily intake of test drinks was also recorded and the compliance was excellent. Furthermore, dose titrating, which has not been used in many previous studies, was one of our advantages. The authors have long experience and expertise in carrying out clinical trials generally and especially in the cardiovascular field. The long treatment periods (3 months each) guaranteed the stabilization of the treatment effects.

A limitation to the study can be regarded as the lack of power calculations because of the absence of previous data. Also, the lack of fasting glucose analyses was a weakness and the number of subjects in the subgroup analysis was therefore very small. More detailed cardiovascular reactivity tests might have given some more information. Two more clinical studies using more sophisticated methods of clinical physiology are in progress.

In conclusion, we found that the long-term intake of L. helveticus-fermented milk containing Ile-Pro-Pro and Val-Pro-Pro tripeptides reduces arterial stiffness expressed as AIx in hypertensive subjects.

Conflict of interest

Tiina Jauhiainen, Katariina Wuolle and Riitta Korpela are employees of Valio Research Centre. Heikki Vapaatalo is a member of the scientific advisory board of MSD Finland Ltd, Santen Ltd, Finland and Valio Ltd, Finland.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Minna Hietala for skilled assistance and Assistant Professor Anu Turpeinen for her skilled help with the manuscript. The test products were provided by Valio Ltd. The study was financially supported by the Finnish Funding Agency for Technology and Innovations (TEKES), The Academy of Finland and the Folkhälsan Research Foundation.

References

- Ahimastos AA, Natoli AK, Lawler A, Blombery PA, Kingwell BA. Ramipril reduces large-artery stiffness in peripheral arterial disease and promotes elastogenic remodeling in cell culture. Hypertens. 2005;45:1194–1199. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000168945.44069.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutouyrie P, Tropeano AI, Asmar R, Gautier I, Benetos A, Lacolley P, et al. Aortic stiffness is an independent predictor of primary coronary events in hypertensive patients: a longitudinal study. Hypertens. 2002;39:10–15. doi: 10.1161/hy0102.099031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Nevo E, Fetics B, Pak P, Yin F, Maughan W, et al. Estimation of central aortic pressure waveform by mathematical transformation of radial tonometry pressure. Validation of generalized transfer function. Circulation. 1997;95:1827–1836. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.7.1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirinos JA, Zambrano JP, Chakko S, Veerani A, Schob A, Willens HJ, et al. Aortic pressure augmentation predicts adverse cardiovascular events in patients with established coronary artery disease. Hypertens. 2005;45:980–985. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000165025.16381.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engberink MF, Schouten EG, Kok FJ, van Mierlo LA, Brouwer IA, Geleijnse JM. Lactotripeptides show no effect on human blood pressure: results from a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Hypertension. 2008;51:399–405. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.098988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FitzGerald RJ, Murray BA, Walsh DJ. Hypotensive peptidesa from milk proteins. J Nutr. 2004;134:980–988. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.4.980S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foltz M, Meynen EE, Bianco V, van Platerink C, Koning TM, Kloek J. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitory peptides from a lactotripeptide-enriched milk beverage are absorbed intact into the circulation. J Nutr. 2007;137:953–958. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.4.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972;18:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota T, Ohki K, Kawagishi R, Kajimoto Y, Mizuno S, Nakamura Y, et al. Casein hydrolysate containing the antihypertensive tripeptides Val-Pro-Pro and Ile-Pro-Pro improves vascular endothelial function independent of blood pressure-lowering effects: contribution of the inhibitory action of angiotensin-converting enzyme. Hypertens Res. 2007;30:489–496. doi: 10.1291/hypres.30.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong F, Ming L, Yi S, Zhanxia L, Yongquan W, Chi L. The antihypertensive effect of peptides: a novel alternative to drugs. Peptides. 2008;29:1062–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jäkälä P, Jauhiainen T, Korpela R, Vapaatalo H. Milk protein-derived bioactive milk peptides Ile-Pro-Pro and Val-Pro-Pro protect endothelial function in vitro in spontaneously hypertensive rats. JFF. 2009;1:266–273. [Google Scholar]

- Jauhiainen T, Rönnback M, Vapaatalo H, Wuolle K, Kautiainen H, Korpela R. Lactobacillus helveticus fermented milk reduces arterial stiffness in hypertensive subjects. Int Dairy J. 2007a;17:1209–1211. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2010.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jauhiainen T, Vapaatalo H, Poussa T, Kyrönpalo S, Rasmussen M, Korpela R. Lactobacillus helveticus fermented milk lowers blood pressure in hypertensive subjects in 24-h ambulatory blood pressure measurement. Am J Hypertens. 2005;18:1600–1605. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jauhiainen T, Wuolle K, Vapaatalo H, Kerojoki O, Nurmela K, Lowrie C, et al. Oral absorption, tissue distribution and excretion of a radiolabelled analog of a milk derived antihypertensive peptide Ile-Pro-Pro in the rat. Int Dairy J. 2007b;17:1216–1223. [Google Scholar]

- Jones PJ, MacDougall DE, Ntanios F, Vanstone CA. Dietary phytosterols as cholesterol-lowering agents in humans. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1997;75:217–227. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-75-3-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korhonen H. Milk-derived bioactive peptides: from science to applications. JFF. 2009;1:177–187. [Google Scholar]

- Laurent S, Boutouyrie P, Asmar R, Gautier I, Laloux B, Guize L, et al. Aortic stiffness is an independent predictor of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in hypertensive patients. Hypertens. 2001;37:1236–1241. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.5.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby P, Aikawa M, Kinlay S, Selwyn A, Ganz P. Lipid lowering improves endothelial functions. Int J Cardiol. 2000;74 (Suppl 1:S3–S10. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(99)00105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London G, Guerin A, Pannier B, Marchais S, Benetos A, Safar M. Increased systolic pressure in chronic uremia. Role of arterial wave reflections. Hypertens. 1992;20:10–19. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.20.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Fandiño R, Otte J, van Camp J. Physiological, chemical and technological aspects of milk-protein-derived peptides with antihypertensive and ACE-inhibitory activity. Int Dairy J. 2006;16:1277–1293. [Google Scholar]

- Mäkynen H, Kähonen M, Arvola P, Wuorela H, Vapaatalo H, Pörsti I. Dietary calcium and magnesium supplements in spontaneously hypertensive rats and isolated arterial reactivity. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;115:1455–1462. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb16637.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäkynen H, Kähönen M, Wu X, Arvola P, Pörsti I. Endothelial function in deoxycorticosterone-NaCl hypertension: effect of calcium supplementation. Circulation. 1996;93:1000–1008. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.5.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda O, Nakamura Y, Takano T. Antihypertensive peptides are present in aorta after oral administration of sour milk containing these peptides to spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Nutr. 1996;126:3063–3068. doi: 10.1093/jn/126.12.3063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mervaala EM, Paakkari I, Laakso J, Nevala R, Teravainen TM, Fyhrquist F, et al. Replacement of salt by a novel potassium- and magnesium-enriched salt alternative improves the cardiovascular effects of ramipril. Br J Pharmacol. 1994;111:1189–1197. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb14871.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y, Masuda O, Takano T. Decrease of tissue angiotensin I-converting enzyme activity upon feeding sour milk in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1996;60:488–489. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narkiewicz K, Kjeldsen SE, Oparil S, Hedner T. Hypertension ans cardiovascular disease: Is arterial stiffness the heart of the matter. Blood Pressure. 2007;16:236–237. doi: 10.1080/08037050701645033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Rourke MF, Gallagher DE. Pulse wave analysis. J Hypertens Suppl. 1996;14:S147–S157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panza JA, Quyyumi AA, Brush JE, Jr, Epstein SE. Abnormal endothelium-dependent vascular relaxation in patients with essential hypertension. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:22–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199007053230105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pripp AH. Effect of peptides derived from food proteins on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Food Nutr Res. 2008;52:1–9. doi: 10.3402/fnr.v52i0.1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selmer RM, Kristiansen IS, Haglerod A, Graff-Iversen S, Larsen HK, Meyer HE, et al. Cost and health consequences of reducing the population intake of salt. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2000;54:697–702. doi: 10.1136/jech.54.9.697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seppo L, Jauhiainen T, Poussa T, Korpela R. A fermented milk high in bioactive peptides has a blood pressure lowering effect in hypertensive subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:326–330. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.2.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sipola M, Finckenberg P, Korpela R, Vapaatalo H, Nurminen M-L. Effect of long-term intake of milk products on blood pressure in hypertensive rats. J Dairy Res. 2002a;69:103–111. doi: 10.1017/s002202990100526x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sipola M, Finckenberg P, Santisteban J, Korpela R, Vapaatalo H, Nurminen M-L. Long-term intake of milk peptides attenuates development of hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2001;52:745–754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sipola M, Finckenberg P, Vapaatalo H, Pihlanto-Leppala A, Korhonen H, Korpela R, et al. Alpha-lactorphin and beta-lactorphin improve arterial function in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Life Sci. 2002b;71:1245–1253. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(02)01793-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolvanen JP, Makynen H, Wu X, Hutri-Kahonen N, Ruskoaho H, Karjala K, et al. Effects of calcium and potassium supplements on arterial tone in vitro in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;124:119–128. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Zander K, Bots ML, Bak AA, Koning MM, de Leeuw PW. Enzymatically hydrolyzed lactotripeptides do not lower blood pressure in mildly hypertensive subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:1697–1702. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vapaatalo H, Mervaala E. Clinically important factors influencing endothelial function. Med Sci Monit. 2001;7:1075–1085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venugopal SK, Devaraj S, Yuhanna I, Shaul P, Jialal I. Demonstration that C-reactive protein decreases eNOS expression and bioactivity in human aortic endothelial cells. Circulation. 2002;106:1439–1441. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000033116.22237.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma S, Wang CH, Li SH, Dumont AS, Fedak PW, Badiwala MV, et al. A self-fulfilling prophecy: C-reactive protein attenuates nitric oxide production and inhibits angiogenesis. Circulation. 2002;106:913–919. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000029802.88087.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson IB, Hall IR, MacCallum H, Mackenzie IS, McEniery CM, van der Arend BJ, et al. Pulse-wave analysis: clinical evaluation of a noninvasive, widely applicable method for assessing endothelial function. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002a;22:147–152. doi: 10.1161/hq0102.101770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson IB, MacCallum H, Flint L, Cockcroft JR, Newby DE, Webb DJ. The influence of heart rate on augmentation index and central arterial pressure in humans. J Physiol. 2000;525 (Part 1:263–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00263.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson IB, Qasem A, McEniery CM, Webb DJ, Avolio AP, Cockcroft JR. Nitric oxide regulates local arterial distensibility in vivo. Circulation. 2002b;105:213–217. doi: 10.1161/hc0202.101970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu JY, Qin LQ, Wang PY, Li W, Chang C. Effect of milk tripeptides on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrition. 2008;24:933–940. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]