Abstract

Hepatitis C virus screening was conducted among 8,226 residents 25–65 years of age in 4 counties of China; virus prevalence was 0.9%. A subsequent case–control study indicated blood transfusion (odds ratio [OR] 4.55), esophageal balloon examination (OR 3.78), and intravenous injection (OR 5.83) were associated with infection.

Keywords: HCV, hepatitis, infection, risk factor, esophageal balloon examination, viruses, dispatch

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection shows clear differences in prevalence among geographic regions, according to World Health Organization data (1). HCV prevalence also varies over time and with behavioral changes (2,3). HCV prevalence in the People’s Republic of China nationwide was estimated at 3.2% in a 1992 survey (4), but studies have reported regional prevalence rates ranging from 0% to 31.9% (5–7). In developing countries, transmission of HCV typically results primarily from iatrogenic factors, such as blood transfusion and inadequate sterilization or reuse of medical equipment (8), but in industrialized countries, risk resulting from these factors has been greatly reduced (9,10).

In an esophageal endoscopic survey (2006–2008) in Anyang, Henan Province, China, blood screening for the HCV antibody was carried out in all participants. Because HCV infection is an important public health issue, a case–control study was performed among HCV-positive case-patients with matched controls to evaluate risk factors for HCV infection in the area where the esophageal endoscopic survey was conducted.

The Study

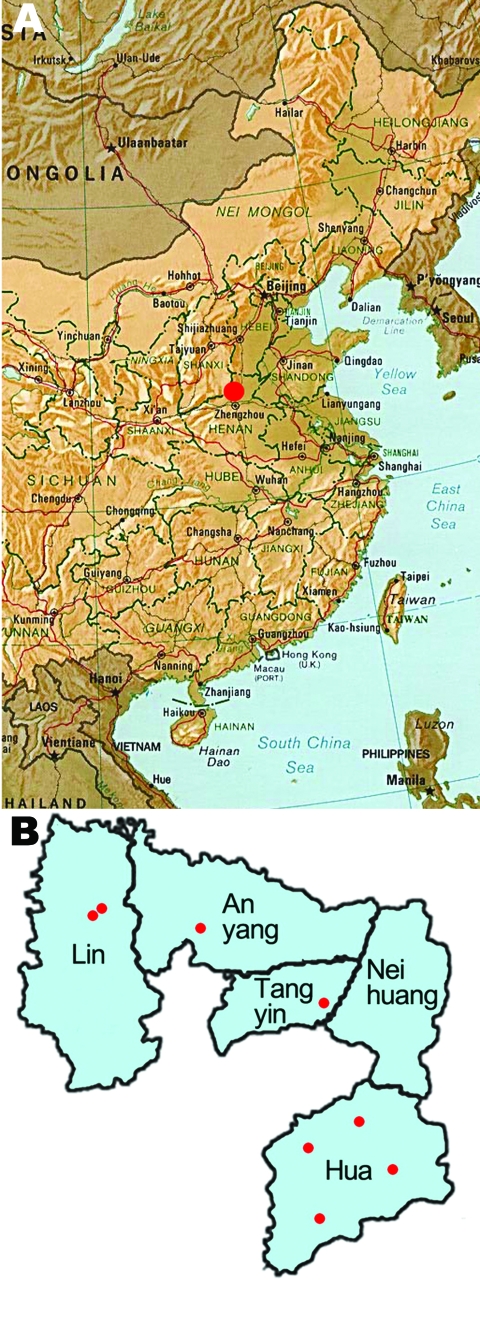

An endoscopic survey (2006–2008) for esophageal cancer was conducted in 8 villages of 4 counties of Anyang, Henan Province, China (Figure). The villages were selected on the basis of population size, location, and village administrative capabilities. A total of 10,240 permanent residents were eligible for the survey; 8,226 (80.3%) persons 25–65 years of age (median age 42.0, M:F sex ratio 1.00:1.18) without cardiovascular or psychological diseases were interviewed and had blood drawn. A total of 74 participants were seropositive for HCV in this screening; 69 of them were enrolled in the subsequent case–control study. Each seropositive person was matched with 3 negative controls randomly selected from seronegative participants (2.5%) of the same village, gender, and age (±2 years). A questionnaire regarding lifetime risk factors for HCV infection was given to HCV seropositive case-patients and matched controls. The Institutional Review Board of the School of Oncology, Peking University, China, approved this study. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Figure.

A) Map of eastern China showing the location of Anyang (red dot). B) Villages (red dots) targeted in the 2006–2008 hepatitis C virus prevalence study.

Serum samples were separated from blood samples by centrifugation and tested for HCV in the Anyang Cancer Hospital for case-patients from Anyang, Lin, and Tangyin counties, and in the Hua County Hospital for case-patients from Hua County. ELISAs were performed to evaluate for HCV antibody (Diagnostic Kit for HCV ELISA 3.0; AutoBio Co., Zhengzhou, China). HCV-positive case-patients submitted an additional blood sample for a confirmatory HCV test in Anyang Cancer Hospital. Positivity for HCV antibody in these 2 tests was independently confirmed at Beijing Friendship Hospital by ELISA (Diagnostic Kit HCV 3.0; Abbott GmbH & Co. KG, Wiesbaden-Delkenheim, Germany). We determined the positive predictive value of the anti-HCV tests conducted in China to be 98.3% by using the testing result of the Abbott diagnostic kit as a standard. Assays were monitored with internal and external quality controls.

We examined group differences using the χ2 test. Univariate and multivariate conditional logistic regression were used to identify significant factors for HCV infection. Data entry and statistical analysis were conducted using Epi Data 3.1 (www.cdc.gov/epiinfo) and SAS 9.1.3 (SAS, Cary, NC, USA); p<0.05 was considered significant.

Seventy-four (0.9%) of 8,266 participants were HCV positive. Prevalence of infection varied significantly with age (p<0.001) and county of origin (p<0.001) but not with gender (Table 1). HCV prevalence was significantly higher in participants >50 years of age. Prevalence was highest in Lin County (2.8%), followed by Anyang County (0.7%), Tangyin County (0.4%), and Hua County (0.2%) (Table 1). The Lin County >50-year-old group showed an 18.25-fold higher risk for HCV infection (95% confidence interval [CI] 9.29–35.83) when compared with non–Lin County participants <50 years of age (data not shown).

Table 1. Demographic distribution and HCV infection status of participants (n = 8,226) in an esophageal endoscopic survey for HCV, Anyang, China, 2006–2008*.

| Variable | Total no. (%) | HCV-positive, no. (%) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | |||

| <50 | 5,766 (70.1) | 37 (0.6) | <0.001 |

| >50 |

2,460 (29.9) |

37 (1.5) |

|

| Sex | |||

| M | 3,782 (46.0) | 31 (0.8) | 0.479 |

| F |

4,444 (54.0) |

43 (1.0) |

|

| County | |||

| Hua | 4,022 (48.9) | 7 (0.2) | <0.001 |

| Anyang | 838 (10.2) | 6 (0.7) | |

| Lin | 1,980 (24.1) | 55 (2.8) | |

| Tangyin | 1,386 (16.8) | 6 (0.4) |

*HCV, hepatitis C virus.

Univariate conditional logistic regression was used to evaluate possible risk factors based on information collected from the 69 HCV-positive participants and 207 matched controls. Transfusion with blood and blood products, intravenous injection, and procedures including Caesarean section, acupuncture, gastroscopy, and esophageal balloon examination were associated with higher risk for HCV infection. No instances of hemodialysis, organ transplantation, drug use, or homosexual behavior were identified. However, when these risk factors were analyzed in a multivariate model, only blood transfusion (odds ratio [OR] 4.55, 95% CI 1.34–15.42), intravenous injection (OR 5.83, 95% CI 2.66–12.80), and esophageal balloon examination (OR 3.78, 95% CI 1.32–10.79) were significant (Table 2). A repeat analysis of participants from Lin County produced almost identical results (data not shown).

Table 2. Conditional logistic analysis of risk factors associated with hepatitis C virus infection, Anyang, China, 2006–2008*.

| Risk factor† | Response | Total no. | HCV negative, no. (%) | HCV positive, no. (%) | OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol consumption |

No | 258 | 195 (94.2) | 63 (91.3) | 1 | |

| Yes |

18 |

12 (5.8) |

6 (8.7) |

1.71 (0.54–5.39) |

|

|

| Blood donation |

No | 261 | 199 (96.1) | 62 (89.9) | 1 | |

| Yes |

15 |

8 (3.9) |

7 (10.1) |

3 (0.99–9.09) |

|

|

| Blood transfusion |

No | 248 | 197 (95.2) | 51 (73.9) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes |

28 |

10 (4.8) |

18 (26.1) |

6.32‡ (2.73–14.6) |

4.55§ (1.34–15.42) |

|

| Blood products transfusion |

No | 249 | 191 (92.3) | 58 (84.1) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes |

27 |

16 (7.7) |

11 (15.9) |

2.49§ (1.03–6.05) |

0.99 (0.28–3.5) |

|

| Intramuscular injection |

No | 39 | 32 (15.5) | 7 (10.1) | 1 | |

| Yes |

237 |

175 (84.5) |

62 (89.9) |

1.77 (0.69–4.59) |

|

|

| Intravenous injection |

No | 153 | 136 (65.7) | 17 (24.6) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes |

123 |

71 (34.3) |

52 (75.4) |

6.75‡ (3.41–13.36) |

5.83‡ (2.66–12.8) |

|

| Visited a dentist |

No | 136 | 103 (49.8) | 33 (47.8) | 1 | |

| Yes |

140 |

104 (50.2) |

36 (52.2) |

1.09 (0.62–1.9) |

|

|

| Had surgery |

No | 210 | 171 (82.6) | 39 (56.5) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes |

66 |

36 (17.4) |

30 (43.5) |

3.78‡ (2.01–7.1) |

2.29 (0.92–5.71) |

|

| Shared nail clippers |

No | 66 | 51 (24.6) | 15 (21.7) | 1 | |

| Yes |

210 |

156 (75.4) |

54 (78.3) |

1.17 (0.62–2.23) |

|

|

| No. sexual partners |

1 | 262 | 194 (93.7) | 68 (98.6) | 1 | |

| >1 |

14 |

13 (6.3) |

1 (1.4) |

0.21 (0.03–1.66) |

|

|

| Pierced ears |

No | 173 | 129 (62.3) | 44 (63.8) | 1 | |

| Yes |

103 |

78 (37.7) |

25 (36.2) |

0.88 (0.4–1.96) |

|

|

| Acupuncture |

No | 215 | 168 (81.2) | 47 (68.1) | 1 | |

| Yes |

61 |

39 (18.8) |

22 (31.9) |

2.15§ (1.11–4.13) |

1.61 (0.69–3.76) |

|

| Gastroscopy |

No | 246 | 190 (91.8) | 56 (81.2) | 1 | |

| Yes |

30 |

17 (8.2) |

13 (18.8) |

2.92§ (1.27–6.72) |

2.06 (0.63–6.7) |

|

| Esophageal balloon examination | No | 240 | 190 (91.8) | 50 (72.5) | 1 | |

| Yes | 36 | 17 (8.2) | 19 (27.5) | 5.95‡ (2.44–14.5) | 3.78§ (1.32–10.79) |

*HCV, hepatitis C virus; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval. †Blood transfusion, blood products transfusion, intravenous injection, operation, acupuncture, gastroscopy, and esophageal balloon examination were included in the multivariate model. ‡p<0.01. §p<0.05.

Conclusions

In this 2006–2008 study, overall HCV prevalence was 0.9%, with prevalence highest in the >50-year-old group of Lin County (4.7%). In a 2000 study of 55- to 84-year-old Lin County residents, the prevalence of HCV was 9.6% (7). Several possible reasons could explain these differences. One is that the average age in the previous study (range 64–84 years) was greater than that in our study (range 25–65 years); older persons were more likely to be infected in both the previous study and our study. The time interval between these 2 studies might also have contributed to the change in HCV prevalence.

A case–control study was performed to identify HCV infection risk factors. Blood transfusion and medical intravenous injection with reusable glass syringes and needles, which are established HCV risk factors, were associated with HCV infection (10,11). In addition, esophageal balloon examination, a less commonly identified route of HCV infection, also increased the risk for HCV infection. In the recent past (1980–2000), esophageal balloon examination, which was designed for early cytologic detection of esophageal lesions, was relatively common in China for diagnosis and screening of persons in high-risk populations (12). In this technique, the patient swallows a balloon covered with a cotton net. The balloon is inflated within the patient’s stomach. Exfoliated esophageal cells are then scraped off the mucosa by pulling out the balloon. Bleeding of esophageal mucosa can occur. The balloon and cotton net were designed to be nonreusable. Nonetheless, on some occasions, balloons were reused after manual cleaning. This technique is no longer widely used; however, Lin County is a high-risk area for esophageal cancer. Screening for esophageal cancer using balloon examination was performed in this region before 2000. Reuse of balloons and occasional bleeding during the procedure may have caused transmission of HCV in this population.

A nationwide survey for HCV infection in China was performed in 1992; prevalence was 3.1% for residents in rural areas. However, prevalence of viral infection was not consistent across regional populations, similar to what was observed in the present study (4). On the basis of these regional differences in HCV distribution and the potential risk factors identified in this study, we strongly suggest that unregulated medical procedures may confer substantial risk for HCV spread.

Chronic infection will develop in ≈75%–85% of persons infected with HCV, and cirrhosis of the liver will develop in up to 20% of chronically infected persons. Hepatocellular carcinoma will develop in ≈3%–4% of patients with HCV-associated cirrhosis each year (13–15). Given the serious social and economic effect of this HCV epidemic, strengthening administrative regulation of medical practice, especially in rural areas, and providing appropriate education to the public about HCV infection and its transmission should be given higher priority in public health policy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Hui Zhuang for advice on HCV detection and Michael A. McNutt for editing the manuscript.

This work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of China (30430710) and “863” Key Projects of National Ministry of Science and Technology Grants 2006AA2Z467 and 2006AA02AA403 to Y.K.

Biography

Ms Liu is a PhD candidate at Peking University School of Oncology. Her research interests include viral infection and the etiology of esophageal cancer.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Liu F, Chen K, He Z, Ning T, Pan Y, Cai H, et al. Hepatitis C seroprevalence and associated risk factors, Anyang, China. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet]. 2009 Nov [date cited]. Available from http://www.cdc.gov/EID/content/15/11/1819.htm

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Hepatitis C: global prevalence. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 1997;72:341–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen J. The scientific challenge of hepatitis C. Science. 1999;285:26–30. 10.1126/science.285.5424.26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baldo V, Baldovin T, Trivello R, Floreani A. Epidemiology of HCV infection. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14:1646–54. 10.2174/138161208784746770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xia G, Liu C, Cao H, Bi S, Zhan M, Su C. Prevalence of hepatitis B and C virus infections in the general Chinese population. Results from a nationwide cross-sectional seroepidemiological study of hepatitis A, B, C, D, and E virus infections in China, 1992. Int Hepatol Commun. 1996;5:62–73. 10.1016/S0928-4346(96)82012-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shimbo S, Zhang ZW, Gao WP, Hu ZH, Qu JB, Watanabe T, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B and C infection markers among adult women in urban and rural areas in Shaanxi Province, China. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1998;29:263–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang S. Seroepidemiological study on hepatitis C virus infection among blood donors from various regions in China [in Chinese]. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 1993;14:271–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang M, Sun XD, Mark SD, Chen W, Wong L, Dawsey SM, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection, Linxian, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:17–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frank C, Mohamed MK, Strickland GT, Lavanchy D, Arthur RR, Magder LS, et al. The role of parenteral antischistosomal therapy in the spread of hepatitis C virus in Egypt. Lancet. 2000;355:887–91. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)06527-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun CA, Chen HC, Lu SN, Chen CJ, Lu CF, You SL, et al. Persistent hyperendemicity of hepatitis C virus infection in Taiwan: the important role of iatrogenic risk factors. J Med Virol. 2001;65:30–4. 10.1002/jmv.1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shepard CW, Finelli L, Alter MJ. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:558–67. 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70216-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prati D. Transmission of hepatitis C by blood transfusions and other medical procedures: a global review. J Hepatol. 2006;45:607–16. 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dawsey SM, Shen Q, Nieberg RK, Liu SF, English SA, Cao J, et al. Studies of esophageal balloon cytology in Linxian, China. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1997;6:121–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Institutes of Health. NIH consensus statement of management of hepatitis C: 2002. NIH Consens State Sci Statements. 2002 Jun10–12;19:1–46. [PubMed]

- 14.Rustgi VK. The epidemiology of hepatitis C infection in the United States. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:513–21. 10.1007/s00535-007-2064-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strader DB, Wright T, Thomas DL, Seeff LB. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2004;39:1147–71. 10.1002/hep.20119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]