Abstract

This study examined associations of generalized and social anxiety with (1) age at first use of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana and (2) interval from first use to first problem use of each substance. Participants were 503 males who comprised the youngest cohort (first assessed in the first grade) of the Pittsburgh Youth Study, a longitudinal community-based study of boys. Annual assessments of generalized and social anxiety, delinquency, and substance use from first grade through high school were included. Both types of anxiety predicted earlier first use of alcohol and tobacco, and generalized anxiety predicted earlier first use of marijuana. Both types of anxiety predicted the progression from first use to problems related to marijuana. The effect of generalized anxiety tended to be significant above and beyond the effect of delinquency, while the effect of social anxiety on risk for first use of substances was not. Overall, the associations between anxiety and substance use and related problems depend on the class of substance and the type of anxiety.

Keywords: Anxiety, Alcohol, Tobacco, Marijuana, Substance use

Anxiety disorders and substance use disorders (SUDs) tend to co-occur within individuals (Grant et al. 2004; Swendsen et al. 1998). The “self-medication” model of substance use (Sher 1991) and the concept of “negative affect alcoholism” (Zucker 1987) are based on the theory that people who experience uncomfortable negative feelings, such as depression or anxiety, may use substances to help them cope with these feelings. These feelings may lead to problems related to heavy substance use as people find the use of substances reinforcing (because it decreases uncomfortable feelings) and therefore increase the frequency and quantity of their use.

There is evidence that anxiety can increase risk for SUDs and SUDs can increase risk for anxiety disorders (see review by Kushner et al. 2000). However, these associations may vary when it comes to substance use as opposed to abuse or dependence (e.g., Rodgers et al. 2000). These associations may also differ by type of anxiety (Kaplow et al. 2001)and/or type of substance (as discussed by Kushner et al. 2000). The purpose of this study was to examine, in a community-based sample of boys: (1) the associations between generalized anxiety and social anxiety and the age at first use of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana; and (2) the associations between these types of anxiety and the progression from first use of each substance to first occurrence of problems related to use of that substance.

Longitudinal Associations Between Generalized and Social Anxiety and Substance Use

We consider generalized and social anxiety separately for several reasons. First, they have been shown in factor-analytic studies to be separate constructs with unique patterns of comorbidity (Lahey et al. 2008). Second, it is possible that each type of anxiety may relate to different reasons for, and therefore different patterns of, substance use. For example, a socially anxious person may use a substance in an effort to fit in with others who are using. Conversely, that person might avoid heavy use of some substances due to their disinhibiting effects; that is, a socially anxious individual might fear doing something embarrassing while under the influence. A person with generalized anxiety may use a substance in an attempt to relax. Conversely, that person might be anxious about possible negative consequences of use, which could be protective. Third, as reviewed below, prior research has found somewhat differing associations between generalized and social anxiety and substance use-related problems. Although substance involvement may lead to anxiety, consistent with the purpose of this study, the following literature review focuses on the possibility that anxiety predicts substance involvement.

Alcohol

Overall, anxiety predicts alcohol dependence (e.g., Kushner et al. 1999), though among adults, both abstainers and heavy alcohol users report higher anxiety than light and moderate drinkers (Rodgers et al. 2000). However, longitudinal studies examining how different subtypes of anxiety predict risk for alcohol use and problems are sparse. Anxiety/ withdrawal among adolescent boys was associated with lower levels of alcohol use disorder symptoms and lower risk of alcohol dependence by early adulthood (Pardini et al. 2007). Generalized anxiety among 9-to-13-year-olds was associated with increased risk for the initiation of alcohol use (Kaplow et al. 2001). Among older youth, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) was associated with the progression from first drink to alcohol dependence (Sartor et al. 2006). Therefore, it seems likely that generalized anxiety is associated with increased risk for alcohol use and dependence, while social anxiety may be related to lower risk for alcohol problems, at least among adolescents.

Tobacco

There has been little longitudinal research on the possibility that generalized and/or social anxiety predict tobacco use and dependence. One study found that social anxiety was associated with increased risk for the development of tobacco dependence (Sonntag et al. 2000), though another study found a delayed onset of smoking in adolescents with anxiety disorders (Costello et al. 1999). Several studies reported no prospective association between anxiety disorders and smoking during adolescence (Johnson et al. 2000; McGee et al. 1998; Patton et al. 1998).

Marijuana

Similarly, little research has addressed the possibility that generalized and/or social anxiety predict marijuana use and related problems. Among young adults, social anxiety was concurrently related to marijuana use problems, but not marijuana use frequency (Buckner et al. 2007). We are unaware of studies that examine whether generalized anxiety predicts marijuana use and related problems.

This review suggests that there are differences in the associations between anxiety and substance use and related problems depending on the type of anxiety and the type of substance. Therefore, in this study we consider both of these factors. In addition, there are developmental differences in links between anxiety and externalizing behaviors (e.g., Marmorstein 2007) and normative changes in substance use (e.g., Maggs and Schulenberg 2005); thus, there may be developmental differences in the nature of these associations. Therefore, we examine potential developmental changes in associations between anxiety and substance use.

There also may be differences in associations by gender; in this study, we only examine boys for several reasons. In addition to the practical reason that only boys were included in this sample, two conceptual reasons supported our decision to examine only boys. First, there is some indication that there may be gender differences in the links between anxiety and substance use and related problems (see review by Armstrong and Costello 2002); therefore simply combining males and females may mask important information about these associations. Second, due to the higher prevalence of internalizing disorders among females, some studies of links between internalizing disorders and substance use use all-female samples (e.g., Bardone et al. 1996; Hill et al. 2000; Rao et al. 2000). This study focusing on boys helps to address that imbalance in the literature.

Because delinquent behavior is associated with anxiety, early use of substances, and substance problems (e.g., Marmorstein 2007; van Kammen et al. 1991), it was considered important to assess whether any anxiety-substance links remained significant beyond the effects of this known “third variable” that is associated with both problems. We also examined whether anxiety interacted with delinquency in order to assess whether the effects of anxiety varied based on the level of delinquency, due to evidence that there may be interaction effects between these problems (Ensminger et al. 1982).

The Current Study

The goal of the current study was to examine, in a community-based sample of boys, the associations of generalized and social anxiety with substance use patterns. We focused on two different measures of substance use: (1) age at first use of alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana, and (2) length of time between first use and the onset of substance use-related problems.

Age of onset was considered important to examine since it relates to risk for use-related disorders, with those youth who try substances early being at increased risk for problem drinking (Warner and White 2003), alcohol abuse and dependence (e.g., Grant and Dawson 1997), internalizing disorders, antisocial personality, and drug use disorders (Flory et al. 2004). The limited findings from studies on alcohol indicate that use (without associated problems) and use-related problems may have different associations with anxiety. Therefore, the progression from first use to the first occurrence of a problem related to use was also considered. Self-medication models of substance use would posit that the anxiolytic effects of substances would render them especially reinforcing for anxious individuals (e.g., Ashton 2001;Lewis 1996). This would suggest that anxious individuals would progress to heavy use—and perhaps related problems—more quickly than non-anxious individuals.

Our hypotheses were derived from both theory and prior research. Based on the self-medication model of substance use, it was hypothesized that both types of anxiety would be associated with an earlier age at first use of these substances. In addition, we hypothesized that both types of anxiety would predict a shorter interval from first use to the onset of substance-related problems, though we expected these effects to be stronger for generalized compared to social anxiety due to the fact that generalized anxiety is more ongoing (i.e., not limited to discrete episodes of being around other people) and therefore might more easily lead to chronic use. We tentatively expected that once delinquency was accounted for, the effects of anxiety would be attenuated; this was expected to be particularly the case for social anxiety.

Methods

Participants

Participants (n=503) for this study were the youngest cohort of the Pittsburgh Youth Study, a community-based study of boys. Annual assessments of boys attending public school beginning in first grade (average age = 6.2 at the screening assessment) and continuing through high school were used in this study. Out of the 1004 families of first-grade boys who were contacted, 84.6% agreed to participate. There were no significant differences in racial composition or achievement test scores between participants and those who refused to participate. Of those who were initially screened, the 30% who were deemed as exhibiting the most antisocial behavior (based on self, parent, and teacher ratings) and another randomly-selected 30% of the screened sample from the remaining 70% were included in the follow-up assessments. Attrition has been low; at each assessment, at least 82% of the boys participated, and 70% participated in all assessments. There was no consistent pattern of selective attrition based on race, socioeconomic status, initial risk status, serious offending, or substance use.

Over half (56.4%) of the participants were African-American, and most of the rest were Caucasian. One-third of the boys' families were receiving public assistance or food stamps at screening. Informed consent was obtained at each assessment. This study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Medical School's Institutional Review Board. Additional information regarding the study design and sample demographics can be found in Loeber et al. (1998, 2008).

Measures

Anxiety

Annual measures of generalized anxiety and social anxiety (shyness/ withdrawal) were taken from rationally-derived scales of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; completed by the primary caretaker), Youth Self Report (YSR; completed by the youth), and Teacher Report Form (TRF; completed by a teacher; all forms are described in Achenbach 1991). These scales assess similar symptoms but are worded for parent, child, and teacher informants, respectively. If any informant reported that the youth exhibited the behavior “sometimes” or “often,” the youth was considered to exhibit that behavior; behaviors were counted to calculate the score. Assessments of these constructs were based on slightly different combinations of the specific measures at different ages, as appropriate given the ages at which each measure is normed and the likelihood of each informant being aware of symptoms (e.g., teachers of older adolescents would be less likely to know the youths well).

It is possible to use either empirically-derived or rationally-derived scales when compiling CBCL, YSR, and TRF data, and there are advantages and disadvantages of each approach. A number of studies have comprehensively discussed the issues involved in choosing which approach to use (Achenbach and Dumenci 2001; Achenbach et al. 2003; Krueger and Piasecki 2002; Lengua et al. 2001; Lengua and Sadowski 2001), so we do not do so here. We chose to use rationally-derived scales that approximate the DSM categories of generalized anxiety disorder and social anxiety disorder primarily because the DSM approach predominates in clinical work and in studies of links between anxiety and substance use and related disorders.

Generalized Anxiety

Generalized anxiety was assessed using a scale constructed from 7 CBCL items, 8 TRF items, and 7 YSR items (range of scores = 0 to 8; mean = 2.20, SD = 1.79). Youth were rated on characteristics such as “nervous, high-strung, or tense.” The average alpha reliability of this scale in this sample was 0.61 across waves.

Social anxiety

Social anxiety-related behavior was assessed using a scale constructed from 7 CBCL items, 7 TRF items, and 7 YSR items (range of scores = 0 to 7; mean = 3.03, SD = 1.87). Youth were rated on characteristics such as “refuses to talk” and “likes to be alone.” The average alpha reliability of this scale in this sample was 0.60 across waves.

Delinquency

The Delinquency Seriousness Classification score was based on the type(s) of delinquent behavior engaged in by the participant using parent, youth, and teacher reports. The development of this scale, along with support for its concurrent and predictive validity, is described in Farrington et al. (1996) and Loeber et al. (1998). Scores corresponded to behavior as follows: 0 = no delinquency; 1 = low-level vandalism or theft; 2 = vandalism at school or outside the home (damage less than $100), arson (no or minor damage), theft (less than $5) or shoplifting, or minor fraud; 3 = gang fighting, vandalism (damage greater than $100), arson (major damage), theft (over $5), stealing a purse or wallet, stealing from a car, dealing in stolen goods, joyriding, or major fraud; 4 = forcible theft, breaking and entering, vehicle theft, sex offenses, or attacking someone with intent to hurt or kill; 5 = engaging in two or more offenses that would each qualify for a score of 4.

Age at first substance use

Ages at first use of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana were assessed via interviews with the participant. Alcohol use was not counted if the reason for drinking was “special occasion or religious ritual” or “with adults at dinner.” If the reported age was less than 5, it was re-coded to 5. The average ages of onset among participants who used each substance by age 18 were: alcohol mean = 12.52, SD = 3.72, median = 13; tobacco mean = 13.33, SD = 3.66, median = 14; marijuana mean = 14.79, SD = 2.36, median = 15. The age at first use of different substances was moderately correlated; Pearson correlations were 0.34, 0.41, and 0.33 for age at first use of alcohol and tobacco, alcohol and marijuana, and tobacco and marijuana, respectively (all significant at the p<0.001 level).

Age at first substance problem

When the participants were approximately age 20, they were administered the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS; Robins and Helzer 1988), a structured psychiatric interview. Other studies have supported the reliability and construct validity of the DIS (reviewed by Malgady et al. 1992). As part of this interview, they were asked about symptoms of abuse and dependence on different substances. When a participant reported experiencing at least one symptom, he was asked at what age the first symptom occurred. This age was used as a measure of the onset of problems related to the use of that substance.

Intervals between first substance use and first substance problem were of interest in this study. The mean years between these onsets (among participants who experienced both) was 4.41 (SD = 3.26) for alcohol, 2.93 (SD = 2.98) for tobacco, and 1.81 (SD = 2.15) for marijuana. The median age at first problem was 16 for alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana.

Statistical Analyses

We used survival analysis, a type of analysis used to examine predictors of whether and when events occur (e.g., Singer and Willett 2003). Survival analysis is more appropriate than basic regression analysis in this case because it deals appropriately with “censored” cases (those whose time of event occurrence is unknown, either because it occurred outside of the period of observation or because it did not occur at all). Survival analyses were conducted using the logit model for discrete time (PROC LOGISTIC in the SAS version 9.1), as is appropriate for events that occur continuously but have been divided into discrete time categories (such as the first use of a substance, which can occur on any day but here was divided into year-long age categories).

All analyses were conducted using lagged anxiety variables, so that the results would represent how anxiety during the previous year predicted the onset of substance use or problems during the subsequent year. Lagged delinquency variables were also used when delinquency was entered into the models as another independent variable.

To examine risk for first use of substances, first, overall analyses examining the slope of risk (linear, quadratic, and/or cubic) for each substance were conducted. Then four sets of survival analyses were conducted: (1) overall associations between each type of anxiety and age at first use of each substance; (2) the same basic models described in #1, but adjusting for the effects of delinquency; (3) the same basic models described in #1, but including interactions between each type of anxiety and linear time, to examine whether the effects of each type of anxiety were consistent across time; and (4) the same basic models described in #1, but including interactions between each type of anxiety and delinquency, to examine whether the effects of anxiety differed based on the level of delinquency. When nested models were examined, we used Akaike's Information Criterion (AIC) and Schwarz Criterion (SC) to compare model fit.

To examine risk for problems related to substance use, the data were centered on age at first use. Therefore, a participant who first used alcohol at age 12 and developed alcohol problems at age 15 would appear in the data as having problems 3 years after his first use. Overall analyses examining the slope of the risk (linear, quadratic, and/or cubic) for each substance were conducted. Four sets of survival analyses, analogous to those presented above but using time from first use to first problem as the dependent variable, were then conducted. Finally, a fifth model including the interaction between age of first use and linear time was examined. In all these time-to-first-problem analyses, age at first use of the substance was adjusted for (individuals who never used a substance were excluded). This adjustment was considered important because early age at first use is a risk factor for substance problems (Grant and Dawson 1997), so including it in the model enhanced our ability to assess unique associations between anxiety and risk for initial substance problem. All analyses were rerun not adjusting for age at first use, and the pattern of significant results remained the same.

This type of analysis comes with assumptions, most notably the proportional odds assumption (e.g., Singer and Willett 2003). This assumption was met, as evidenced by the non-significant time-by-anxiety interaction terms (Model 3 in each set of analyses) and the fact that these models did not fit better than models without these terms (Model 1 in each set of analyses).

Because time-varying predictors (i.e., the level of each type of anxiety at each age) were used, the interpretation of parameters is not entirely straightforward. The overall survival function represents the probability that a given participant will “survive” to that time point (in this case, not try the substance by that time point or not develop substance problems prior to that time point). The odds ratios presented represent the difference from that overall survival function that is associated with a 1-unit increase in the predictor (generalized or social anxiety). As an example, for an analysis examining social anxiety predicting first use of alcohol, an odds ratio of 2.0 would indicate that a 1-point higher score on the social anxiety scale (which amounts to somewhat more than one-half of a standard deviation, as described above) would predict that the participant would be at twice the risk of using alcohol for the first time in the following year (compared to his risk with a 1-point lower social anxiety score).

Results

Substance use was examined through age 20 (because anxiety measures were available through high school, the last assessment for most participants was at age 18; when age 19 and 20 assessments were available, they were included). Most participants had used all three substances by age 18 (78.9%, 56.5%, and 55.5% had used alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana, respectively).

At all ages, generalized anxiety and social anxiety were significantly associated with each other (average r=0.50 across ages). Generalized and social anxiety were less-strongly correlated with delinquent behavior (average r=0.19 and 0.20, respectively).

Age at First Use of Substances

As indicated by the fit statistics presented in the left half of Table 1, a slope model including a cubic term was appropriate for age of onset of each substance. AIC indicated that the cubic model was best for all substances and SC indicated that the cubic model was best for tobacco and marijuana and approximately equivalent to the quadratic model for alcohol. Therefore, risk for first use increased slowly during the initial assessment periods, increased rapidly during the middle assessment periods, and then increased less rapidly during the later assessment periods.

Table 1.

Fit Statistics for Linear, Quadratic, and Cubic Models of Time Representing Age at First Substance Use and Time to First Substance-Related Problem

| Age at first use |

Time to first problem |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol |

Tobacco |

Marijuana |

Alcohol |

Tobacco |

Marijuana |

|||||||

| AIC | SC | AIC | SC | AIC | SC | AIC | SC | AIC | SC | AIC | SC | |

| Linear | 2671.97 | 2684.95 | 2245.17 | 2258.62 | 2202.76 | 2216.32 | 858.82 | 872.19 | 1026.82 | 1039.44 | 672.27 | 684.94 |

| Quadratic | 2661.94 | 2681.42 | 2208.37 | 2228.56 | 2023.30 | 2043.65 | 804.56 | 824.62 | 1001.56 | 1020.50 | 635.60 | 654.61 |

| Cubic | 2658.08 | 2684.04 | 2185.42 | 2212.33 | 2012.38 | 2039.51 | 803.69 | 830.44 | 996.58 | 1021.82 | 634.16 | 659.51 |

AIC Akaike's information criterion; SC Schwarz criterion

Odds ratios derived from analyses examining associations between generalized and social anxiety and age at first use of substances are presented in Table 2, along with significance levels derived from the associated chi-square tests of significance. We present chi-square values for interaction effects to ease interpretation.

Table 2.

Odds Ratios (95% Confidence Intervals) and Chi-Square Values Representing Risk for First Use of Substances Associated with a 1-Point Increase in Predictor Variablesa

| Generalized Anxiety |

Social Anxiety |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Alcohol | ||||||||

| Time | 0.12*** (0.05–0.29) | 0.10*** (0.04–0.26) | 0.12*** (0.05–0.29) | 0.10*** (0.04–0.26) | 0.12*** (0.05–0.30) | 0.10*** (0.04–0.26) | 0.11*** (0.05–0.29) | 0.10*** (0.04–0.25) |

| Time2 | 1.21*** (1.12–1.31) | 1.22*** (1.13–1.33) | 1.22*** (1.12–1.31) | 1.22*** (1.13–1.33) | 1.21*** (1.12–1.31) | 1.22*** (1.13–1.33) | 1.22*** (1.12–1.32) | 1.23*** (1.13–1.33) |

| Time3 | 1.00*** (0.99–1.00) | 1.00*** (0.99–1.00) | 1.00*** (0.99–1.00) | 1.00*** (0.99–1.00) | 1.00*** (0.99–1.00) | 1.00*** (0.99–1.00) | 1.00*** (0.99–1.00) | 1.00*** (0.99–1.00) |

| Anxiety | 1.18*** (1.12–1.26) | 1.09* (1.02–1.16) | 1.20*** (1.13–1.28) | 1.07 (1.00–1.14) | 1.13*** (1.06–1.20) | 1.04 (0.98–1.11) | 1.14* (1.07–1.22) | 1.02 (0.95–1.09) |

| Delinquency | 1.69*** (1.56–1.84) | 1.68*** (1.54–1.83) | 1.71*** (1.58–1.86) | 1.70*** (1.56–1.85) | ||||

| Anxiety*time | χ2=1.68 | χ2=0.63 | ||||||

| Anxiety*delinquency | χ2=1.31 | χ2=3.21 | ||||||

| AIC | 2459.65 | 2297.23 | 2459.97 | 2297.91 | 2474.60 | 2301.93 | 2475.98 | 2300.70 |

| SC | 2491.05 | 2334.84 | 2497.65 | 2341.79 | 2506.01 | 2339.55 | 2513.66 | 2344.58 |

| Tobacco | ||||||||

| Time | 0.06*** (0.02–0.16) | 0.06*** (0.02–0.17) | 0.06*** (0.02–0.17) | 0.06*** (0.02–0.17) | 0.06*** (0.02–0.16) | 0.06*** (0.02–0.17) | 0.06*** (0.02–0.18) | 0.06*** (0.02–0.17) |

| Time2 | 1.30*** (1.18–1.42) | 1.29*** (1.17–1.41) | 1.30*** (1.18–1.42) | 1.29*** (1.17–1.41) | 1.29*** (1.18–1.41) | 1.29*** (1.17–1.41) | 1.28*** (1.17–1.41) | 1.29*** (1.17–1.41) |

| Time3 | 0.99*** (0.99–1.00) | 0.99*** (0.99–1.00) | 0.99*** (0.99–1.00) | 0.99*** (0.99–1.00) | 0.99*** (0.99–1.00) | 0.99*** (0.99–1.00) | 0.99*** (0.99–1.00) | 0.99*** (0.99–1.00) |

| Anxiety | 1.17*** (1.09–1.25) | 1.09* (1.02–1.17) | 1.16 (1.08–1.25) | 1.07 (0.99–1.16) | 1.16*** (1.09–1.25) | 1.06 (0.99–1.14) | 1.14 (1.06–1.24) | 1.06 (0.98–1.15) |

| Delinquency | 1.54*** (1.42–1.68) | 1.53*** (1.40–1.67) | 1.55*** (1.42–1.68) | 1.54*** (1.41–1.68) | ||||

| Anxiety*time | χ2=0.09 | χ2=0.94 | ||||||

| Anxiety*delinquency | χ2=0.83 | χ2=1.55 | ||||||

| AIC | 2105.77 | 2007.90 | 2107.69 | 2009.08 | 2108.64 | 2009.46 | 2109.71 | 2009.90 |

| SC | 2138.18 | 2046.72 | 2146.57 | 2054.37 | 2141.04 | 2048.28 | 2148.59 | 2055.19 |

| Marijuana | ||||||||

| Time | 0.32 (0.03–3.07) | 0.17 (0.02–1.44) | 0.33 (0.03–3.25) | 0.17 (0.02–1.52) | 0.34 (0.04–3.24) | 0.19 (0.02–1.67) | 0.34 (0.03–3.43) | 0.18 (0.02–1.62) |

| Time2 | 1.19* (1.01–1.41) | 1.25** (1.06–1.47) | 1.19* (1.00–1.42) | 1.24* (1.05–1.46) | 1.19* (1.00–1.41) | 1.24* (1.05–1.46) | 1.19 (1.00–1.42) | 1.24* (1.05–1.47) |

| Time3 | 0.99** (0.99–1.00) | 0.99** (0.99–1.00) | 0.99** (0.99–1.00) | 0.99** (0.99–1.00) | 0.99** (0.99–1.00) | 0.99** (0.99–1.00) | 0.99* (0.99–1.00) | 0.99** (0.99–1.00) |

| Anxiety | 1.09** (1.02–1.17) | 0.98 (0.91–1.06) | 1.09 (0.97–1.22) | 1.00 (0.92–1.09) | 1.06 (0.99–1.14) | 0.94 (0.87–1.01) | 1.06 (0.94–1.20) | 0.92 (0.85–1.00) |

| Delinquency | 1.89*** (1.73–2.08) | 1.90*** (1.73–2.08) | 1.92*** (1.75–2.11) | 1.92*** (1.75–2.11) | ||||

| Anxiety*time | χ2=0.01 | χ2=0.00 | ||||||

| Anxiety*delinquency | χ2=0.96 | χ2=0.79 | ||||||

| AIC | 1905.10 | 1708.44 | 1907.09 | 1709.48 | 1909.27 | 1705.84 | 1911.27 | 1707.05 |

| SC | 1937.93 | 1747.78 | 1946.48 | 1755.38 | 1942.11 | 1745.18 | 1950.67 | 1752.95 |

Model 1: baseline (time, anxiety); Model 2: time, anxiety, delinquency; Model 3: time, anxiety, interaction of time and anxiety; Model 4: time, anxiety, delinquency, interaction of anxiety and delinquency. When interaction effects are included in a model, we present main effect odds ratios of the variables included in the interaction; those odds ratios represent the effect of one variable at the mean of the other variable

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001;

p<.10;

n=503; AIC Akaike's information criterion; SC Schwarz criterion

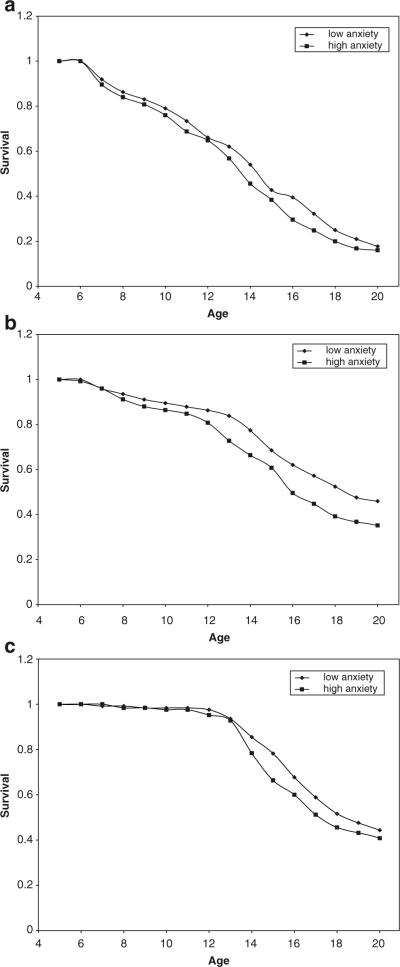

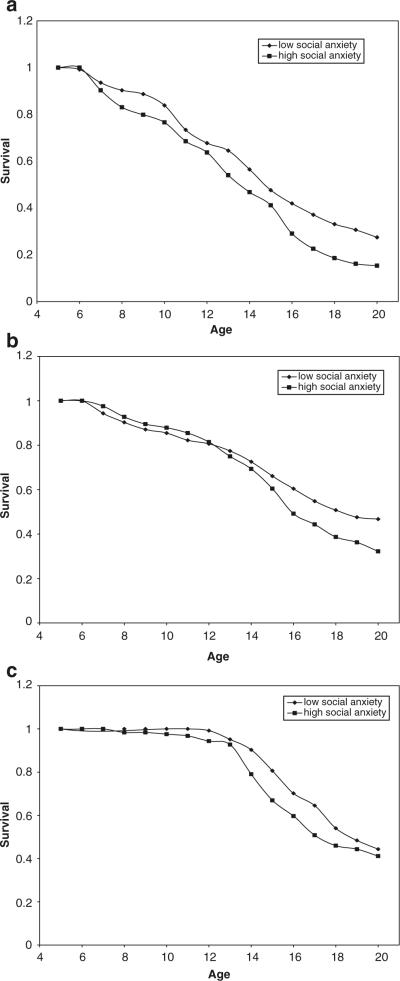

Overall effects of generalized and social anxiety are presented in the “Model 1” (anxiety alone) and “Model 2” (adjusting for the effects of delinquency) columns of Table 2. Both generalized and social anxiety predicted increased risk for the first use of alcohol during the following year (Figs. 1a and 2a). Generalized anxiety, but not social anxiety, remained significant when delinquent behavior was adjusted for. Both generalized and social anxiety predicted increased risk for first use of tobacco during the following year (Figs. 1b and 2b) Generalized anxiety, but not social anxiety, remained significant when delinquent behavior was adjusted for. Generalized anxiety predicted increased risk for first use of marijuana during the following year (Fig. 1c). However, once delinquent behavior was adjusted for, generalized anxiety was no longer significant. Social anxiety was not a significant predictor of risk of first use of marijuana (Fig. 2c), with or without adjusting for delinquent behavior.

Fig. 1.

(a) Survival plots for high (75th percentile) and low (25th percentile) levels of generalized anxiety, depicting age at first use of alcohol; (b) Survival plots for high (75th percentile) and low (25th percentile) levels of generalized anxiety, depicting age at first use of tobacco; (c). Survival plots for high (75th percentile) and low (25th percentile) levels of generalized anxiety, depicting age at first use of marijuana

Fig. 2.

(a) Survival plots for high (75th percentile) and low (25th percentile) levels of social anxiety, depicting age at first use of alcohol; (b) Survival plots for high (75th percentile) and low (25th percentile) levels of social anxiety, depicting age at first use of tobacco; (c) Survival plots for high (75th percentile) and low (25th percentile) levels of social anxiety, depicting age at first use of marijuana

We next added terms representing the interaction effect of linear time with each type of anxiety to the basic models (“Model 3” columns in Table 2). For all substances, this interaction term was non-significant, and models with these terms did not fit better than models that included only main effects. Therefore, there is no evidence for developmental differences from childhood through late adolescence in associations between generalized or social anxiety and first use of substances.

We next added terms representing the interaction effect of delinquent behavior with each type of anxiety to the basic models (“Model 4” columns in Table 2). No significant interactions between anxiety and delinquent behavior were found, and models with these terms did not fit better than models that included only main effects. Thus, there is no evidence that delinquent behavior moderated the associations between anxiety and first use of substances.

Risk for Substance-related Problems

As indicated by the fit statistics presented in the right half of Table 1, a slope model including a quadratic term for time was appropriate for alcohol and marijuana, indicating that risk for related problems increased after first use, then leveled off. For tobacco, a model including a cubic term was appropriate, indicating that the slope of risk increased slowly shortly after first use, increased more rapidly later, and then leveled off.

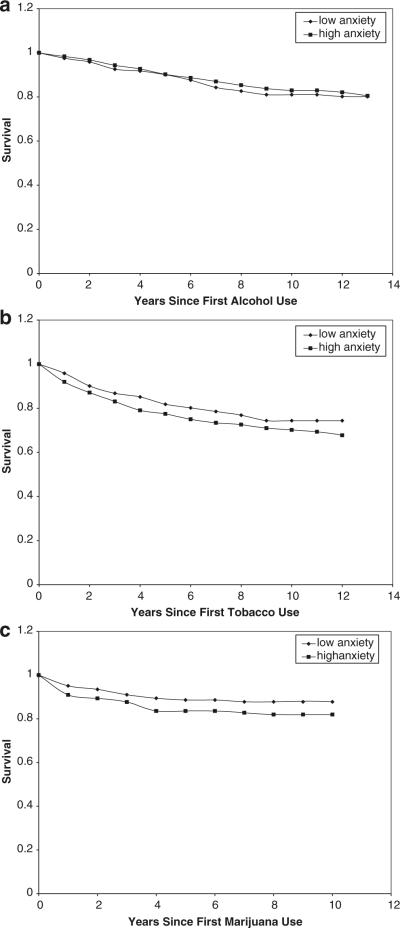

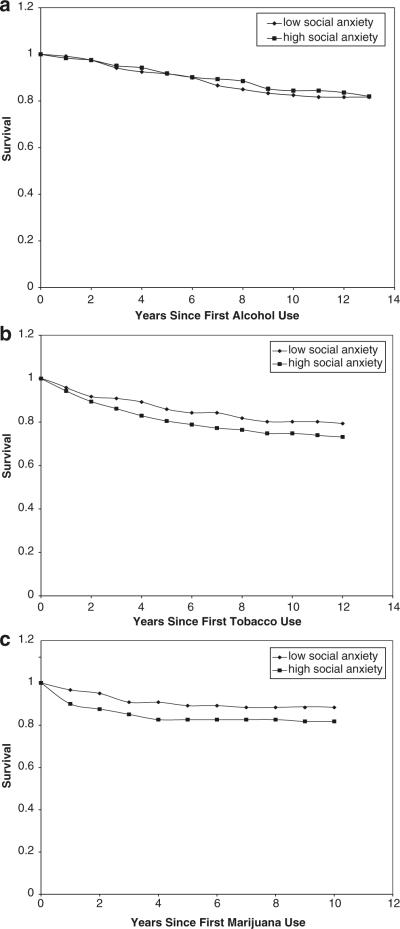

Results of analyses examining associations between generalized and social anxiety and time between first use of a substance and first problem related to that substance are presented in Table 3. As presented in the “Model 1” columns of Table 3, neither generalized nor social anxiety was significantly associated with time from first use to first problem for alcohol or tobacco (Figs. 3a, b and 4a, b). In contrast, both types of anxiety were associated with increased risk for marijuana problems during the following year, once the participant had used marijuana (Figs. 3c and 4c). After adjusting for delinquency (“Model 2” columns in Table 3), this effect remained significant for social anxiety and dropped below significance for generalized anxiety (p=0.11).

Table 3.

Odds Ratios (95% Confidence Intervals) Representing Risk for First Problem Related to the Use of Each Substance Associated with a 1-Point Increase in Predictor Variablesa

| Generalized Anxiety |

Social Anxiety |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

| Alcohol (n=412) | ||||||||||

| Time | 352.76*** (35.25–99) | 278.41*** (27.00–99) | 304.92*** (29.21–99) | 279.05*** (27.05–99) | 379.48*** (37.14–99) | 366.08*** (35.99–99) | 264.57*** (25.76–99) | 548.43*** (37.43–99) | 271.52*** (26.37–99) | 394.10*** (37.94–99) |

| Time2 | 0.84*** (0.78–0.90) | 0.84*** (0.79–0.91) | 0.85*** (0.79–0.91) | 0.85*** (0.79–0.91) | 0.84*** (0.78–0.90) | 0.84*** (0.78–0.90) | 0.85*** (0.79–0.91) | 0.83*** (0.76–0.90) | 0.85*** (0.79–0.91) | 0.84*** (0.78–0.90) |

| Age at 1st use | 0.97 (0.92–1.03) | 0.98 (0.93–1.04) | 0.97 (0.92–1.03) | 0.98 (0.93–1.04) | 0.91 (0.78–1.08) | 0.97 (0.92–1.03) | 0.98 (0.93–1.04) | 0.97 (0.92–1.03) | 0.98 (0.92–1.04) | 0.91 (0.78–1.08) |

| Anx | 1.03 (0.92–1.15) | 0.98 (0.87–1.10) | 0.94 (0.66–1.34) | 0.98 (0.86–1.11) | 1.03 (0.92–1.15) | 1.03 (0.91–1.17) | 0.96 (0.84–1.09) | 1.16 (0.80–1.70) | 0.94 (0.82–1.08) | 1.03 (0.91–1.17) |

| Delinq | 1.33*** (1.16–1.53) | 1.33** (1.16–1.53) | 1.34*** (1.17–1.54) | 1.36 (1.18–1.58) | ||||||

| Anx*time | χ2=0.28 | χ2=0.52 | ||||||||

| Anx*delinq | χ2=0.01 | χ2=0.71 | ||||||||

| Age at 1st use*time | χ2=0.59 | χ2=0.61 | ||||||||

| AIC | 772.46 | 752.05 | 774.18 | 754.04 | 773.87 | 772.43 | 751.79 | 774.00 | 753.08 | 773.82 |

| SC | 805.20 | 791.31 | 813.47 | 799.85 | 813.16 | 805.17 | 791.05 | 813.29 | 798.89 | 813.11 |

| Tobacco (n=301) | ||||||||||

| Time | 0.06 (0.00–1.19) | 0.05 (0.00–1.05) | 0.05 (0.00–1.01) | 0.05 (0.00–1.02) | 0.06 (0.00–1.28) | 0.07 (0.00–1.57) | 0.07 (0.00–1.45) | 0.12 (0.00–3.12) | 0.07 (0.00–1.52) | 0.08 (0.00–1.71) |

| Time2 | 1.34* (1.07–1.69) | 1.35* (1.07–1.70) | 1.36** (1.08–1.72) | 1.36** (1.08–1.71) | 1.34* (1.06–1.68) | 1.32* (1.05–1.68) | 1.33* (1.05–1.68) | 1.27 (0.99–1.64) | 1.33* (1.05–1.68) | 1.32* (1.04–1.67) |

| Time3 | 0.99** (0.99–1.00) | 0.99** (0.99–1.00) | 0.99** (0.99–1.00) | 0.99** (0.99–1.00) | 0.99** (0.99–1.00) | 0.99** (0.99–1.00) | 0.99** (0.99–1.00) | 0.99* (0.99–1.00) | 0.99** (0.99–1.00) | 0.99** (0.99–1.00) |

| Age at 1st use | 0.98 (0.93–1.02) | 0.98 (0.93–1.03) | 0.98 (0.93–1.02) | 0.98 (0.93–1.03) | 0.92 (0.84–1.01) | 0.98 (0.93–1.02) | 0.98 (0.93–1.03) | 0.97 (0.93–1.02) | 0.98 (0.93–1.03) | 0.92 (0.84–1.01) |

| Anx | 1.04 (0.94–1.15) | 1.03 (0.93–1.15) | 1.09 (0.90–1.31) | 1.02 (0.91–1.14) | 1.04 (0.93–1.15) | 0.97 (0.87–1.08) | 0.95 (0.85–1.06) | 0.88 (0.72–1.07) | 0.95 (0.85–1.07) | 0.96 (0.86–1.08) |

| Delinq | 1.08 (0.95–1.23) | 1.07 (0.94–1.22) | 1.11 (0.98–1.26) | 1.10 (0.97–1.25) | ||||||

| Anx*time | χ2=0.32 | χ2=1.26 | ||||||||

| Anx*delinq | χ2=0.76 | χ2=0.59 | ||||||||

| Age at 1stuse*time | χ2=2.02 | χ2=2.08 | ||||||||

| AIC | 923.32 | 909.77 | 924.99 | 911.01 | 923.29 | 923.38 | 909.19 | 924.11 | 910.60 | 923.29 |

| SC | 960.33 | 952.92 | 968.18 | 960.33 | 966.48 | 960.39 | 952.35 | 967.30 | 959.92 | 966.48 |

| Marijuana (n=294) | ||||||||||

| Time | 34.65*** (6.77–177.40) | 30.61*** (5.94–157.68) | 38.94*** (6.81–222.72) | 30.64*** (5.95–157.84) | 35.18*** (6.82–181.43) | 32.66*** (6.28–169.76) | 29.61*** (5.67–154.59) | 25.15*** (4.46–141.87) | 30.26*** (5.76–159.04) | 33.44*** (6.38–175.42) |

| Time2 | 0.90*** (0.85–0.95) | 0.90*** (0.86–0.95) | 0.90*** (0.85–0.95) | 0.90*** (0.86–0.95) | 0.90*** (0.85–0.95) | 0.90*** (0.86–0.95) | 0.91*** (0.86–0.96) | 0.91*** (0.86–0.96) | 0.90*** (0.86–0.95) | 0.90*** (0.85–0.95) |

| Age at 1stuse | 0.91* (0.83–1.00) | 0.92* (0.84–1.01) | 0.91* (0.83–1.00) | 0.92# (0.83–1.01) | 0.89 (0.73–1.09) | 0.91# (0.83–1.00) | 0.93# (0.84–1.01) | 0.91# (0.84–1.00) | 0.92# (0.84–1.01) | 0.88 (0.72–1.08) |

| Anx | 1.14* (1.01–1.28) | 1.11 (0.98–1.26) | 1.20 (0.92–1.57) | 1.12# (0.99–1.28) | 1.14# (1.00–1.28) | 1.20# (1.04–1.37) | 1.17* (1.01–1.35) | 1.09 (0.80–1.47) | 1.15 (0.99–1.33) | 1.20* (1.04–1.38) |

| Delinq | 1.12 (0.96–1.30) | 1.13 (0.97–1.31) | 1.10 (0.94–1.29) | 1.09 (0.93–1.29) | ||||||

| Anx*time | χ2=0.19 | χ2=0.51 | ||||||||

| Anx*delinq | χ2=0.74 | χ2=0.84 | ||||||||

| Age at 1stuse*time | χ2=0.06 | χ2=0.14 | ||||||||

| AIC | 613.25 | 612.77 | 615.06 | 614.02 | 615.18 | 610.83 | 610.76 | 612.33 | 611.92 | 612.69 |

| SC | 644.26 | 649.96 | 652.28 | 657.42 | 652.41 | 641.85 | 647.96 | 649.55 | 655.32 | 649.92 |

Model 1: baseline (time, age at first use, anxiety); Model 2: time, age at first use, anxiety, delinquency; Model 3: time, age at first use, anxiety, interaction of time and anxiety; Model 4: time, age at first use, anxiety, delinquency, interaction of anxiety and delinquency; Model 5: time, age at first use, anxiety, and interaction of age at first use and time. When interaction effects are included in a model, we present main effect odds ratios of the variables included in the interaction; those odds ratios represent the effect of one variable at the mean of the other variable

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001;

p<0.10;

AIC Akaike's information criterion; SC Schwarz criterion; anx anxiety; delinq delinquency

Fig. 3.

(a) Survival plots for high (75th percentile) and low (25th percentile) levels of generalized anxiety, depicting time from first use to first alcohol-related problem; (b) Survival plots for high (75th percentile) and low (25th percentile) levels of generalized anxiety, depicting time from first use to first tobacco-related problem; (c) Survival plots for high (75th percentile) and low (25th percentile) levels of generalized anxiety, depicting time from first use to first marijuana-related problem

Fig. 4.

(a) Survival plots for high (75th percentile) and low (25th percentile) levels of social anxiety, depicting time from first use to first alcohol-related problem; (b) Survival plots for high (75th percentile) and low (25th percentile) levels of social anxiety, depicting age time from first use to first tobacco-related problem; (c) Survival plots for high (75th percentile) and low (25th percentile) levels of social anxiety, depicting time from first use to first marijuana-related problem

We next added terms representing the interaction of linear time and each type of anxiety to the basic models (“Model 3” columns in Table 3). For all substances, this interaction term was non-significant, and models with these terms did not fit better than models that included only main effects. Therefore, there is no evidence for developmental differences in associations between generalized or social anxiety and time from first use to first substance-related problem.

We next added terms representing the interaction of delinquent behavior with each type of anxiety to the basic models (“Model 4” columns in Table 3). No significant interactions between anxiety and delinquent behavior were found, indicating that delinquent behavior did not moderate the links between anxiety and the onset of substance problems once use was initiated.

We next entered a term representing the interaction effect of age at first use with linear time to the basic models (“Model 5” columns in Table 3). No significant interactions were found, indicating that the effect of time was not moderated by age at first use.

Discussion

The results of this study indicate that the effects of anxiety on substance involvement depended on the type of anxiety, the type of substance, and whether age of first use or time to development of substance problems was examined. Our first goal was to examine the effects of generalized and social anxiety on age at first use of alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana. The effects of both types of anxiety on age at first use were stronger for alcohol and tobacco use than for marijuana use, with high levels of either type of anxiety predicting earlier ages of first use. Our second goal was to examine the effects of generalized and social anxiety on the interval from first use to first problem related to the use of these substances. Both types of anxiety predicted heightened risk for the development of marijuana problems, but not alcohol or tobacco problems.

These differences in effects depending on the substance and the examination of substance use versus problems are intriguing. People report expecting that these substances will help them relax (e.g., Kassel et al. 2003; Schafer and Brown 1991); for this reason, one would expect that anxious people would try these substances at earlier ages than would non-anxious people. This assumption is consistent with our findings for alcohol and tobacco that youth with either type of anxiety were at increased risk of earlier first use of these substances. However, most studies on expectancies have been conducted using samples of adults, and often with samples of individuals who may have already tried substances. Children and adolescents who have never used these substances may have different expectancies regarding their effects (and those expectancies may differ by age). Among youth who have never used marijuana, anxiety-reduction expectancies may not predominate. Alternatively, perhaps the illicit nature of marijuana makes anxious youth less likely to try it due to worries about getting caught; this could explain the positive effect of anxiety on first use of tobacco but not marijuana.

When the interval between first substance use and first use-related problem was examined, the opposite pattern emerged: there were non-significant effects of anxiety for alcohol and tobacco, but significant effects for marijuana. Perhaps once anxious youths overcome the anticipatory anxiety associated with trying marijuana, they discover that it helps them relax (Ashton 2001) and they begin to use it regularly. This effect might not happen with tobacco, since its anxiolytic effects seem to be most prominent in regular smokers (Morissette et al. 2007). It is unclear, however, why this effect was not found for alcohol; it would seem that anxious youths would find its anxiolytic effects (Lewis 1996) reinforcing and would therefore be at heightened risk for a relatively quick development of problems. However, data from studies of rats indicate that adolescents may be less sensitive to the anxiolytic effects of alcohol than adults (Varlinskaya and Spear 2002); if this finding translates to humans, this could explain this lack of an association between anxiety and time from first use to first problem. In addition, there is minimal and conflicting evidence that alcohol reduces social anxiety (Carrigan and Randall 2003), so this could explain the lack of effect for social anxiety in particular. Alternatively, it is possible that anxious youths fear the loss of control that accompanies heavy alcohol use; this concern, if present, could be protective.

Some, but not all, associations between anxiety and substance use and problems were attenuated when the effect of delinquent behavior was accounted for. Although the overall associations between generalized and social anxiety and the initiation of substance use and related problems were quite similar, the apparent link between social anxiety in particular and risk for initial substance use was related to co-occurring delinquent behavior. It is not clear why these differences emerged. One possibility is that social anxiety may limit the peer networks of shy youth, thereby limiting access to substances to those who also affiliate with delinquent peers (perhaps related to their own delinquency). It is also possible that socially anxious youth may use substances in an attempt to fit in with their peers. If their friends use substances—and are therefore more likely to engage in delinquent behaviors—this would put socially anxious youth at risk for substance use. In contrast, if their friends do not use substances, socially anxious youth would not be at risk for substance use. Generalized anxiety, in contrast, may not restrict peer affiliations, and therefore generalized anxiety and delinquency may exert separate (additive) effects on substance use. Youth who are generally anxious may use substances to cope with anxiety; this pathway would not be dependent on delinquent or substance-using peers. Future research incorporating measures of peer networks would be useful for testing these possibilities.

The results of this study are consistent with Kaplow et al. (2001), who reported that generalized anxiety was associated with increased risk for the initiation of alcohol use. However, they are not consistent with Sartor et al. (2006), who reported that GAD was associated with the progression from first drink to alcohol dependence. Perhaps this association is only present when diagnosable cases of GAD or alcohol dependence are considered.

This study had limitations. The sample was comprised only of males; it is not clear whether these results would apply to females. The participants were all from one geographic area; it is not clear how the results would generalize to adolescents from other communities. The measures of anxiety and delinquent behavior were based on questionnaire data from youth, parents, and teachers and the measures of substance use and problems were based on self-reports by youth; all of these measures are subject to biased responding. The internal consistency reliabilities of the anxiety scales were relatively low; although this was expected because they were constructed based on the similarity of items to DSM criteria and not based on maximizing internal consistency, these low alpha reliabilities may have led to underestimates of the effects of the predictor variables.

Despite these caveats, the results of this study indicate that boys with higher compared to lower levels of generalized and/or social anxiety are at risk for trying both tobacco and alcohol at earlier ages; in addition, boys with higher levels of generalized anxiety are at higher risk for trying marijuana at earlier ages. However, the effect of social anxiety on initial use of substances diminishes once the effect of delinquent behavior is accounted for. In addition, boys with higher compared to lower levels of either of these types of anxiety are at risk for a relatively more rapid development of marijuana problems once they have used marijuana.

There are several implications for prevention that can be drawn from this study. First, anxious children are an appropriate target group for prevention efforts aimed at delaying the onset of substance use. Second, among socially anxious youth, those with co-occurring delinquent behavior are particularly at risk for early substance use. Third, it is important to intervene with anxious youth who have used marijuana as quickly and effectively as possible, since they are at high risk for the rapid development of marijuana-related problems. This study also has implications for research in this area: specifically, it highlights the importance of considering different types of anxiety and different classes of substances separately when examining the associations between anxiety and substance use and related problems.

Acknowledgements

Preparation of this paper was supported, in part, by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (K01DA022456, DA411018 and DA17552), the National Institute on Mental Health (MH73941 and MH50778), and the U.S. Department of Justice (96-MU-FX-0020). Points of view or opinions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official positions or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice or the National Institutes on Drug Abuse And Mental Health. The authors thank Rebecca Stallings for her help with the data preparation.

References

- Achenbach TM. Integrative guide to the 1991 CBCL/4–18, YSR, and TRF Profiles. University of Vermont, Department of Psychology; Burlington: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Dumenci L. Advances in empirically based assessment: revised cross-informant syndromes and new DSM-oriented scales for the CBCL, YSR, and TRF: Comment on Lengua, Sadowski, Friedrich, and Fisher (2001) Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:699–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Dumenci LL, Rescorla L. DSM-oriented and empirically based approaches to constructing from the same item pools. Journal of Clinical and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32:328–40. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3203_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong TD, Costello EJ. Community studies on adolescent substance use, abuse, or dependence and psychiatric comorbidity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:1224–1239. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.6.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashton CH. Pharmacology and effects of cannabis: a brief review. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;178:101–106. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.2.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardone AM, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Dickson N, Silva PA. Adult mental health and social outcomes of adolescent girls with depression and conduct disorder. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:811–829. [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Bonn-Miller MO, Zvolensky MJ, Schmidt NB. Marijuana use motives and social anxiety among marijuana-using young adults. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2238–2252. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrigan MH, Randall CL. Self-medication in social phobia a review of the alcohol literature. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28:269–284. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00235-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Erkanli A, Federman E, Angold A. Development of psychiatric comorbidity with substance abuse in adolescence: Effects of timing and sex. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1999;28:298–311. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp280302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ensminger ME, Brown CH, Kellam SG. Sex differences in antecedents of substance use among adolescents. Journal of Social Issues. 1982;38:25–42. [Google Scholar]

- Farrington DP, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M, van Kammen WB, Schmidt L. Self-reported delinquency and a combined delinquency seriousness scale based on boys, mothers, and teachers: concurrent and predictive validity for African-Americans and Caucasians. Criminology. 1996;34:493–518. [Google Scholar]

- Flory K, Lynam D, Milich R, Leukefeld C, Clayton R. Early adolescent through young adult alcohol and marijuana use trajectories: early predictors, young adult outcomes, and predictive utility. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:193–213. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404044475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age at onset of alcohol use and its association with DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1997;9:103–110. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Compton W, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:807–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill EM, Boyd CJ, Kortge JF. Variation in suicidality among substance-abusing women: the role of childhood adversity. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2000;19:339–345. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(00)00113-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Cohen P, Pine DS, Klein DF, Kasen S, Brook JS. Association between cigarette smoking and anxiety disorders during adolescence and early adulthood. JAMA. 2000;284:2348–2351. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.18.2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplow JB, Curran PJ, Angold A, Costello EJ. The prospective relation between dimensions of anxiety and the initiation of adolescent alcohol use. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001;30:316–326. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3003_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassel JD, Stroud LR, Pardonis CA. Smoking, stress, and negative affect: correlation, causation, and context across stages of smoking. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:270–304. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Piasecki TM. Toward a dimensional and psychometrically-informed approach to conceptualizing psychopathology behaviour research and therapy. Behavioral Research and Therapy. 2002;40:485–499. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(02)00016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner MG, Abrams K, Borchardt C. The relationship between anxiety disorders and alcohol use disorders: a review of major perspectives and findings. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20:149–171. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner MG, Sher KJ, Erikson DJ. Prospective analysis of the relation between DSM-III anxiety disorders and alcohol use disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:723–732. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.5.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Rathouz PJ, van Hulle C, Urbano RC, Krueger RF, Applegate B, et al. Testing structural models of DSM-IV symptoms of common forms of child and adolescent psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:187–206. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9169-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengua LJ, Sadowski CA. Assessing the child psychopathology beast: a reply to Achenbach and Dumenci's (2001) commentary. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:703–705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengua LJ, Sadowski CA, Friedrich WN, Fisher J. Rationally and empirically derived dimensions of children's symptomatology: expert ratings and confirmatory factor analyses of the CBCL. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:683–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MJ. Alcohol reinforcement and neuropharmacological therapeutics. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 1996;31(suppl. 1):17–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Farrington DP, Stouthamer-Loeber M, van Kammen WB. Antisocial behavior and mental health problems: Explanatory factors in childhood and adolescence. Erlbaum; Mawhaw: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Farrington D, Stouthamer-Loeber M, White HR. Violence and serious theft: Developmental course and origins from childhood to adulthood. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Maggs JL, Schulenberg JE. Initiation and course of alcohol consumption among adolescents and young adults. In: Galanter M, Lowman C, Boyd GM, Faden VB, Witt E, Lagressa D, editors. Recent developments in alcoholism: Alcohol problems in adolescents and young adults. vol. 17. 2005. pp. 29–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malgady RG, Rogler LH, Tyron WW. Issues of validity in the diagnostic interview. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1992;26:59–67. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(92)90016-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmorstein NR. Relationships between anxiety and externalizing disorders in youth: the influences of age and gender. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2007;21:420–432. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee R, William S, Stanton W. Is mental health in childhood a major predictor of smoking in adolescence? Addiction. 1998;93:1869–1874. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.9312186912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morissette SB, Tull MT, Gulliver SB, Kamholz BW, Zimering RT. Anxiety, anxiety disorders, tobacco use and nicotine; a critical review of interrelationships. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133:245–272. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardini D, White HR, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Early adolescent psychopathology as a predictor of alcohol use disorders by young adulthood. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;88S:S38–S49. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton GC, Carlin JB, Coffey C, Wolfe R, Hibbert M, Bowes G. Depression, anxiety and smoking initiation: a prospective study over 3 years. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88:1518–1522. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.10.1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao U, Daley SE, Hammen C. Relationship between depression and substance use disorders in adolescent women during the transition to adulthood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:215–222. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200002000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Helzer JE. The diagnostic interview schedule: its development, evaluation, and use. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 1988;23:6–16. doi: 10.1007/BF01788437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers B, Korten AE, Jorm AF, Jacomb PA, Christensen H, Henderson AS. Non-linear relationships in associations of depression and anxiety with alcohol use. Psychological Medicine. 2000;30:421–432. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799001865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartor CE, Lynskey MT, Heath AC, Jacob T, True W. The role of childhood risk factors in initiation of alcohol use and progression to alcohol dependence. Addiction. 2006;102:216–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer J, Brown SA. Marijuana and cocaine effect expectancies and drug use patterns. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:558–565. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher K. Children of alcoholics: A critical appraisal of theory and research. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. Oxford University Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sonntag H, Wittchen H-U, Hofler RC, Stein MB. Are social fears and DSM-IV social anxiety disorder associated with smoking and nicotine dependence in adolescents and young adults? European Psychiatry. 2000;15:67–74. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(00)00209-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swendsen JD, Merikangas KR, Canino GJ, Kessler RC, Rubio-Stipec M, Angst J. The comorbidity of alcoholism with anxiety and depressive disorders in four geographic communities. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1998;39:176–184. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(98)90058-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varlinskaya EI, Spear LP. Acute effects of ethanol on social behavior of adolescent and adult rats: role of familiarity of the test situation. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2002;26:1502–1511. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000034033.95701.E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner LA, White HR. Longitudinal effects of age at onset and first drinking situations on problem drinking. Substance Use and Misuse. 2003;38:1983–2016. doi: 10.1081/ja-120025123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kammen WB, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Substance use and its relationship to conduct problems and delinquency in young boys. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1991;20:399–413. doi: 10.1007/BF01537182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA. The four alcoholisms: A developmental account of the etiological process. In: Dienstbier RA, Rivers PC, editors. Nebraska symposium on motivation 1986: Alcohol and addictive behavior. 1987. pp. 27–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]