Abstract

Expression of the T-cell receptor (TCR):CD3 complex is tightly regulated during T-cell development. The mechanism and physiological role of this regulation are unclear. Here, we show that the TCR:CD3 complex is constitutively ubiquitylated in immature double positive (DP) thymocytes, but not mature single positive (SP) thymocytes or splenic T cells. This steady state, tonic CD3 monoubiquitylation is mediated by the CD3ɛ proline-rich sequence, Lck, c-Cbl, and SLAP, which collectively trigger the dynamin-dependent downmodulation, lysosomal sequestration and degradation of surface TCR:CD3 complexes. Blocking this tonic ubiquitylation by mutating all the lysines in the CD3 cytoplasmic tails significantly upregulates TCR levels on DP thymocytes. Mimicking monoubiquitylation by expression of a CD3ζ-monoubiquitin (monoUb) fusion molecule significantly reduces TCR levels on immature thymocytes. Moreover, modulating CD3 ubiquitylation alters immunological synapse (IS) formation and Erk phosphorylation, thereby shifting the signalling threshold for positive and negative selection, and regulatory T-cell development. Thus, tonic TCR:CD3 ubiquitylation results in precise regulation of TCR expression on immature T cells, which is required to maintain the fidelity of T-cell development.

Keywords: c-Cbl; signalling, T-cell development, T-cell receptor:CD3, ubiquitylation

Introduction

The T-cell receptor (TCR):CD3 complex, one of the most complicated receptor complexes on the cell membrane, is composed of a TCRαβ heterodimer, which recognizes cognate antigen, and the associated CD3 molecules (CD3δ, γ, ɛ, and ζ), which are required for TCR expression, signal transduction, and receptor transport (Clevers et al, 1988; Klausner et al, 1990). A hallmark of T-cell development in the thymus is the tightly controlled cell surface expression of the TCR:CD3 complex, which is low on double positive (DP; CD4+CD8+) thymocytes and high on single positive (SP; CD4+ or CD8+) thymocytes and peripheral T cells (Bluestone et al, 1987). Subtle changes in TCR signal strength determine the fate of immature thymocytes and therefore the fine control of TCR:CD3 expression level on immature thymocytes is likely to be essential in controlling T-cell selection (Daniels et al, 2006). However, the precise mechanism that controls TCR expression in the thymus is unclear. Initially, a posttranscriptional mechanism or instability of the nascent TCRα protein was proposed to regulate TCR:CD3 expression during T-cell development (Bluestone et al, 1987; Klausner et al, 1990; Kearse et al, 1994, 1995). However, recent studies have suggested that ubiquitylation may contribute to this process. Ubiquitin (Ub) can be attached to proteins via free lysine (K) residues by specific E3 Ub ligases (Glickman and Ciechanover, 2002). Monoubiquitylation (the addition of a single Ub residue) has been shown to modulate protein endocytosis and intracellular transport (Haglund et al, 2003a; Marmor and Yarden, 2004). MonoUb can be further modified to generate polyUb chains via an isopeptide linkage between the C-terminal glycine carboxyl group of the Ub being added and the ɛ-amino group of a lysine on the protein-attached Ub (Hochstrasser, 2006), which predominantly occurs at K48 and K63 (Peng et al, 2003; Xu and Peng, 2008). Whereas K48-linked polyubiquitylation typically leads to protein degradation by 26S proteasomes (Glickman and Ciechanover, 2002; Goldberg, 2003), K63-linked polyubiquitylation is thought to modulate a variety of events including signal transduction and receptor endocytosis (Wang et al, 2001). Two molecules that are highly expressed in the thymus, c-Cbl (Cbl; Casitas B-lineage lymphoma), a RING-type E3 Ub ligase, and SLAP (Sla; Src-like adaptor protein), a c-Cbl adaptor protein, are thought to modulate TCR expression on DP thymocytes (Sosinowski et al, 2001; Molero et al, 2004; Myers et al, 2006). However, c-Cbl and SLAP interact with and/or ubiquitylate multiple T-cell signalling molecules, such as Lck and Zap70 (Tang et al, 1999; Thien and Langdon, 2001; Rao et al, 2002), and thus it is unclear which interaction is responsible for the regulation of TCR expression on immature T cells. Recently, it was suggested that LAPTM5, a lysosomal protein, negatively regulates surface TCR expression by degrading CD3ζ via its Ub-interacting motif, suggesting a possible role for ubiquitylation in modulating TCR:CD3 complex expression (Ouchida et al, 2008). However, TCR expression on DP thymocytes was only slightly increased in Laptm5−/− mice.

In this study, we addressed the following questions using biochemical analysis, confocal microscopy, and in vivo genetic approaches: (1) Is the TCR:CD3 complex differentially ubiquitylated in thymic and splenic T cells, and if so what type of ubiquitylation occurs (e.g. monoUb, polyUb)? (2) What is the mechanism by which TCR:CD3 surface expression is regulated and what molecules participate in CD3 ubiquitylation? (3) What is the physiological role of TCR:CD3 ubiquitylation?

Results

Tonic ubiquitylation of CD3 in DP thymocytes

To investigate the mechanism that regulates TCR surface expression on immature T cells (Supplementary Figure S1A), we first confirmed that CD3 protein expression in DP thymocytes is much lower than SP thymocytes (Supplementary Figure S1B), which is clearly due to a posttranscriptional degradative event, as mRNA levels of all four CD3 molecules were similar between DP and SP thymocytes (Supplementary Figure S1C) (Maguire et al, 1990).

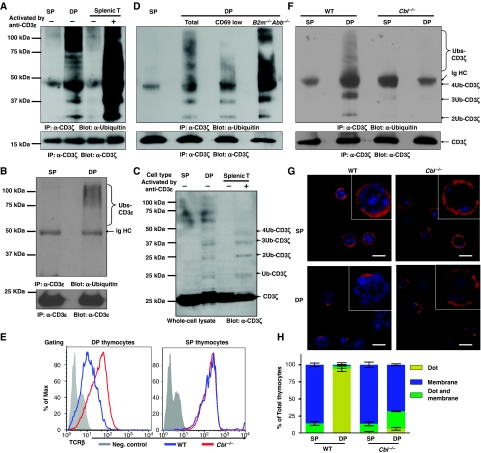

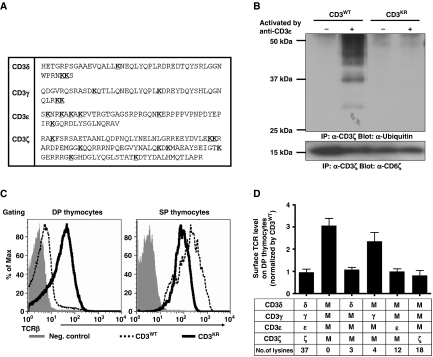

As some receptors have been shown to be regulated by a Ub-dependent endocytosis mechanism (Shih et al, 2000), and CD3ζ and δ are ubiquitylated after T-cell activation (Cenciarelli et al, 1992), we speculated that increased ubiquitylation of CD3 may occur in immature thymic T cells. To test this possibility, we assessed whether CD3ζ was ubiquitylated in DP thymocytes. CD3ζ from resting SP thymocytes, DP thymocytes, and splenic T cells was immunoprecipitated, separated on an SDS–PAGE gel and western blots probed with a Ub monoclonal antibody (mAb). Lysate from crosslinked anti-CD3ɛ-activated splenic T cells was included as a positive control. As expected, we observed a ladder of ubiquitylated CD3ζ in activated, but not resting, splenic T cells. The size of these bands (24, 32, 40 kD, etc.) was consistent with CD3ζ modification by progressive addition of the 8-kD Ub protein (Cenciarelli et al, 1992). Remarkably, constitutively ubiquitylated CD3ζ was observed in DP, but not SP thymocytes in the absence of TCR:CD3 crosslinking (Figure 1A). Similarly, we detected ubiquitylation of CD3ɛ in DP, but not SP thymocytes following immunoprecipitation with CD3ɛ mAbs and western blot analysis with a Ub mAb (Figure 1B). A comparable polyUb ladder was also seen by direct western blot analysis of DP thymocyte lysates with a CD3ζ mAb (Figure 1C). These data show that at any one time only a small proportion of CD3ζ is ubiquitylated suggesting a dynamic process.

Figure 1.

c-Cbl-mediated tonic ubiquitylation of CD3 on immature T cells. (A–D, F) DP and SP thymocytes were purified by FACS, and splenic T cells purified by MACS. Splenic T cells were either resting or activated by crosslinking CD3ɛ for 2 min. (A) SP thymocytes (3 × 107), DP thymocytes (24 × 107), and resting or activated splenic T cells (3 × 107) were lysed in 1 ml lysis buffer. The lysates were immunoprecipitated with CD3ɛ antisera (551ζ), separated by SDS–PAGE and western blots was probed with Ub mAb (P4D1). Blots were stripped and reprobed with CD3ζ mAb (H146) to show that an equal amount of CD3ζ was analysed in each sample. (B) After immunoprecipitation with CD3ζ mAb as described in (A), the lysates were further immunoprecipitated with CD3ɛ mAb (2C11), separated by SDS–PAGE and western blots was probed with Ub mAb. Blots were stripped and reprobed with CD3ɛ mAb (HTM3.1). (C) Lysates (20 μl) were separated by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotted with CD3ζ mAb. (D, F) Analysis was performed as in (A), except that wild-type CD69low and B2m−/−Abb−/− [MHC class I and class II deficient] DP thymocytes (D), or c-Cbl−/− SP and DP thymocytes (F) were purified by FACS and included in the analysis. (E) DP and SP thymocytes were purified from either C57BL/6J mice or c-Cbl−/− mice, and TCRβ surface expression was measured by flow cytometry. (G, H) Thymocytes were stained with mAbs against CD4 and CD8, and DP and SP thymocytes purified by FACS. Sorted thymocytes were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with Alexa-647-conjugated CD3ζ mAb. The localization of CD3ζ (red) and DAPI-stained nucleus (blue) are shown in representative confocal images (G). The distribution of CD3ζ in thymocyte populations is indicated (n>50) (H).

Given that CD3ζ in splenic T cells is ubiquitylated following TCR ligation, it is possible that the observed ubiquitylation in DP thymocytes is derived from the fraction of thymocytes that are undergoing positive selection. Interestingly, a similar level of CD3ζ ubiquitylation was observed in CD69lo prepositive selection DP thymocytes and DP thymocytes from mice lacking MHC class I and class II [B2m−/−Abb−/−] (Figure 1D). These data suggest that CD3ζ ubiquitylation in DP thymocytes is constitutive and MHC-ligation independent, showing that this is not restricted to cells undergoing positive selection. Hereafter, we refer to this process as ‘tonic' ubiquitylation as it appears analogous to the low level, constitutive tyrosine phosphorylation of the TCR:CD3 observed in DP thymocytes (Nakayama et al, 1989). Cbl−/− DP thymocytes express high levels of TCR (Figure 1E) (Murphy et al, 1998; Naramura et al, 1998), suggesting c-Cbl is involved in TCR downregulation. Indeed, the Cbl−/− thymocytes exhibit little CD3ζ ubiquitylation showing that c-Cbl expression is required for ubiquitylation of CD3ζ (Figure 1F).

Given that ubiquitylation has been shown to alter protein trafficking and intracellular location (Haglund et al, 2003a; Marmor and Yarden, 2004; Mukhopadhyay and Riezman, 2007), we questioned whether the TCR:CD3 complex was differentially distributed in SP versus DP thymocytes. In wild-type mice, CD3ζ was uniformly distributed on the cell surface of SP thymocytes (Figure 1G and H). Surprisingly, although some CD3ζ in DP thymocytes was expressed on the cell surface, most appeared to be confined to a single, defined intracellular compartment. A similar differential staining pattern was observed when thymocytes were stained with antibodies to either TCRβ or CD3ɛ (data not shown). Interestingly, this TCR:CD3 sequestration was not observed in Cbl−/− DP thymocytes, which instead looked essentially identical to the even surface staining pattern observed in wild-type SP thymocytes and their Cbl−/− SP counterparts (Figure 1G and H). These data show that CD3 ubiquitylation leads to the redistribution and intracellular sequestration of the TCR:CD3 complex in DP thymocytes. We also observed a similar phenotype in Sla−/− thymocytes (Supplementary Figure S2). Taken together, these data suggest that c-Cbl/SLAP-dependent, MHC-independent tonic ubiquitylation of the TCR:CD3 complex occurs on DP thymocytes, but not SP thymocytes or peripheral T cells and that this modulates TCR surface expression by orchestrating its cellular sequestration.

Lck and the CD3ɛ proline-rich sequence are required for CD3 tonic ubiquitylation

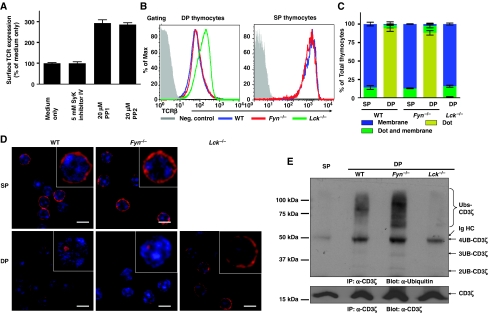

To determine whether Src kinases are involved in the regulation of TCR expression in DP thymocytes, we treated neonatal thymi with Src kinase inhibitors (PP1 and PP2). Inhibition of Src kinase activity upregulated surface TCR expression on DP thymocytes, suggesting that either Lck or Fyn might be involved in the CD3 tonic ubiquitylation pathway (Figure 2A). We next analysed TCR expression on DP thymocytes from WT, Fyn−/−, and Lck−/− mice by flow cytometry. Although Fyn deficiency had no effect on TCR expression on DP thymocytes, there was a substantial increase in TCR expression on Lck−/− DP thymocytes (Figure 2B). Likewise the absence of Lck, but not Fyn altered the distribution pattern of CD3ζ in DP thymocytes, which was indistinguishable to that observed in wild-type SP thymocytes (Figure 2C and D). To test whether Lck or Fyn mediates tonic ubiquitylation of CD3, we assessed the ubiquitylation status of CD3ζ in DP thymocytes of WT, Fyn−/−, and Lck−/− mice. Although tonic ubiquitylation of CD3ζ was observed in WT and Fyn−/− DP thymocytes, it was absent in Lck−/− DP thymocytes (Figure 2E). These data show that Lck, rather than Fyn, is required for CD3 tonic ubiquitylation and thus regulation of TCR surface expression on immature T cells.

Figure 2.

Lck is required for tonic ubiquitylation of CD3 in DP thymocytes. (A) Thymic lobes from newborn mice (P1) were treated with the inhibitors indicated for 20 h, and surface TCRβ expression determined by flow cytometry. Data represent the mean±s.e.m. of 5–10 mice from 2–3 experiments per group. (B) Thymi were isolated from WT, Fyn−/−, or Lck−/− mice. Surface expression of the TCR:CD3 complex was measured by flow cytometry on thymocytes co-stained with mAbs against CD4, CD8, and TCRβ. (C, D) Thymocytes were stained with mAbs against CD4 and CD8, and DP and SP thymocytes purified by FACS. Sorted thymocytes were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with Alexa-647-conjugated CD3ζ mAb. The distribution of CD3ζ in thymocyte populations is indicated (n>50) (C). The localization of CD3ζ (red) and DAPI stained nucleus (blue) are shown in representative confocal images (D). (E) Tonic ubiquitylation of CD3 was performed with WT, Fyn−/−, or Lck−/− mice as described in Figure 1A.

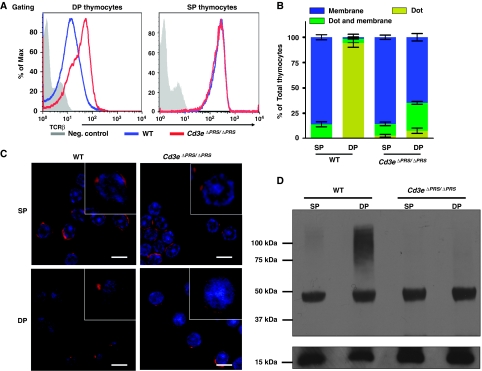

Earlier studies have shown that the proline-rich sequence (PRS) in CD3ɛ modulates TCR expression and signal transduction, suggesting that the CD3ɛ-PRS may be involved in tonic ubiquitylation of CD3 in DP thymocytes (Szymczak et al, 2005; Mingueneau et al, 2008; Tailor et al, 2008). To assess this possibility, we examined CD3 expression, distribution, and ubiquitylation in DP thymocytes from mice possessing a knock-in mutation of the CD3ɛ PRS (Cd3eΔPRS/ΔPRS) (Mingueneau et al, 2008). As described earlier (Mingueneau et al, 2008), TCR expression was increased on Cd3eΔPRS/ΔPRS DP thymocytes compared with their wild-type controls (Figure 3A). As seen in DP thymocytes lacking c-Cbl, Slap, and Lck, DP thymocytes from Cd3eΔPRS/ΔPRS mice exhibited an even TCR:CD3 surface distribution, as seen in wild-type SP thymocytes (Figure 3B and C). Furthermore, there was a complete loss of CD3ζ tonic ubiquitylation in Cd3eΔPRS/ΔPRS DP thymocytes (Figure 3D). Taken together, these data show that the CD3ɛ-PRS is required for CD3 tonic ubiquitylation and suggests that CD3ɛ-PRS association with Nck may mediate TCR:CD3 complex translocation to intracellular compartments.

Figure 3.

CD3ɛ-PRS mediates CD3 tonic ubiquitylation in DP thymocytes. (A) Thymi were isolated from WT or CD3eΔPRS/ΔPRS mice. Surface expression of the TCR:CD3 complex was measured by flow cytometry on thymocytes co-stained with mAbs against CD4, CD8, and TCRβ. (B, C) Thymocytes were stained with anti-CD4 and anti-CD8, and DP and SP thymocytes were purified by FACS. Sorted thymocytes were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with Alexa-647-conjugated CD3ζ mAb. The distribution of CD3ζ in thymocyte populations is indicated (n>50) (B). The localization of CD3ζ (red) and DAPI-stained nucleus (blue) are shown in representative confocal images (C). (D) Tonic ubiquitylation of CD3 was performed as described in Figure 1A.

TCR:CD3 monoubiquitylation mediates its dynamin-dependent internalization and targeting to lysosomes for degradation

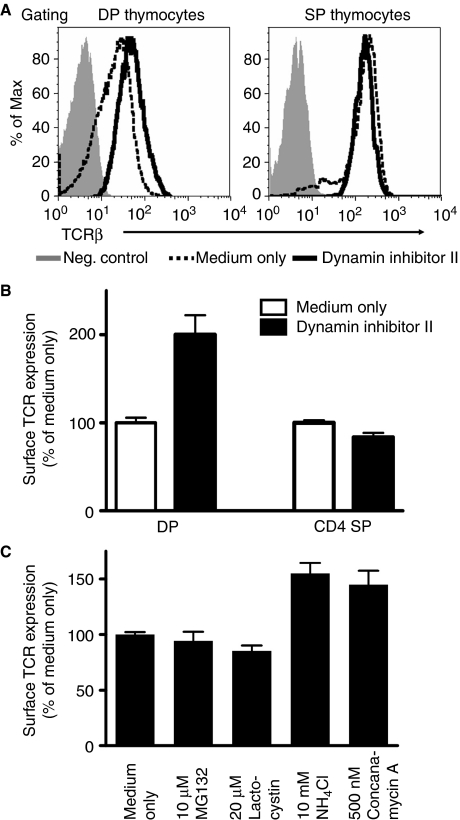

The intracellular TCR:CD3 sequestration observed in DP thymocytes suggested that there might be an active downregulation process mediated by tonic CD3 ubiquitylation. Dynamin is a guanosine triphosphatase that is required for the fission of membrane and endocytic vesicles (Praefcke and McMahon, 2004). To determine whether dynamin contributes to TCR internalization in DP thymocytes, we treated neonatal thymi with a dynamin inhibitor (MiTMAB) (Figure 4A and B). There was a substantial increase of surface TCR on DP, but not SP thymocytes, suggesting that ubiquitylation may mediate enhanced, dynamin-dependent TCR:CD3 internalization and downregulation in immature DP but not mature SP thymocytes. However, additional studies will be required to fully elucidate the contribution of dynamin in these events.

Figure 4.

Monoubiquitylation induces dynamin-mediated internalization of the TCR:CD3 complex followed by lysosomal degradation. Thymic lobes from neonatal mice (P1) were treated with the inhibitors indicated for 20 h, and surface TCRβ expression determined by flow cytometry. Data represent the mean±s.e.m. of 5–8 mice from 2 to 3 experiments per group (A, B) or 5–10 mice from 2 to 3 experiments per group (C). A full-colour version of this figure is available at The EMBO Journal Online.

The reduced CD3 protein levels in DP versus SP thymocytes, despite comparable mRNA levels (Supplementary Figure S1), suggested that the TCR:CD3 complex was being degraded in DP thymocytes. We reasoned that this Ub modification might mediate the internalization and trafficking of the TCR complex in DP thymocytes to sites of degradation; lysosomes or proteasomes. Thus, we next determined the fate of tonic ubiquitylated TCR:CD3 complexes on DP thymocytes in neonatal thymic organ culture experiments using inhibitors of lysosomal (NH4Cl and Concanamycin A) and proteasomal degradation (MG132 and lactacystin). Consistent with earlier studies (Kosugi et al, 1992; Lacorazza and Nikolich-Zugich, 2004), our data suggest that the TCR:CD3 complexes in DP thymocytes are degraded in lysosomes, and not by proteasomes (Figure 4C). A recent study reported that a lysosomal protein, LAPTM5, controls the degradation of CD3ζ in DP thymocytes and activated T cells, a process that requires the LAPTM5 Ub-interacting motif (Ouchida et al, 2008). Consistent with these data, we observed that CD3ζ colocalized with LAPTM5 in DP but not SP thymocytes (Supplementary Figure S3). Taken together, these data suggest that ubiquitylated TCR:CD3 complexes are degraded in lysosomes. However, additional analysis will be required to fully define the intracellular trafficking and degradation pathway of TCR:CD3 complexes in DP thymocytes.

Two types of Ub modification have been linked with protein internalization and trafficking to lysosomes; monoubiquitylation (Haglund et al, 2003a; Marmor and Yarden, 2004) and K63-linked polyubiquitylation (Mukhopadhyay and Riezman, 2007). To distinguish between these two forms of Ub modification, we used a mAb specific for all forms of poly-, but not mono-, ubiquitylated proteins (polyUb, clone FK1) (Haglund et al, 2003b; Fujimuro and Yokosawa, 2005) and a highly specific and sensitive K63-linked polyUb-specific mAb (K63Ub, clone HWA4C4) that we recently developed (Wang et al, 2008). Western blot analysis of CD3ζ in DP thymocytes clearly indicated that tonic Ub modification was detected with an mAb specific for Ub but not polyUb mAb or K63Ub mAb (Supplementary Figure S4). Taken together, these data are consistent with a model in which tonic monoubiquitylated TCR:CD3 complexes are internalized in a dynamin-dependent manner and transported to lysosomes for degradation, thus maintaining the characteristic low surface TCR expression seen on DP thymocytes. However, we cannot completely rule out the possibility that CD3 polyubiquitylation occurs, albeit to an extent that could not be detected with the approaches used here.

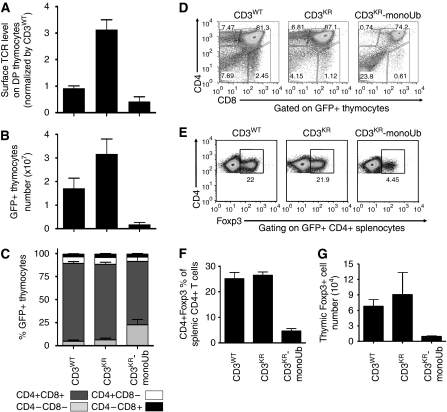

Tonic ubiquitylation regulates TCR surface expression on immature T cells

We next directly assessed whether this tonic ubiquitylation was required and sufficient for the regulation of TCR surface expression on DP thymocytes by generating mutant mice in which CD3 ubiquitylation was blocked. Of the known target residues for ubiquitylation (Cadwell and Coscoy, 2005), there are 37 lysines and no cysteines in the CD3 cytoplasmic domains (Figure 5A). Furthermore, it has been shown previously that the intracellular lysines of CD3ζ are required for CD3ζ ubiquitylation (Hou et al, 1994). To block CD3 tonic ubiquitylation, we generated mice expressing CD3 mutant molecules (CD3KR), in which all cytoplasmic lysines were mutated to arginines, using retroviral-mediated stem cell gene transfer and multicistronic 2A peptide-linked retroviral vectors (Supplementary Figure S5) (Holst et al, 2006a, 2006b) [referred to as retrogenic mice]. CD3-deficient bone marrow donors (referred to herein as CD3ɛζ−/− mice) were generated by crossing Cd247−/− (CD3ζ) and Cd3eΔp/Δp (CD3ɛ) mice. The latter possess a PGK-neo cassette inserted into Cd3e gene that results in the complete silencing of the adjacent Cd3g (CD3γ) and Cd3d (CD3δ) genes (Wang et al, 1999; Holst et al, 2008). Rag1−/− mice, which lack T and B cells, were used as recipients. Western blot analysis confirmed that CD3ζ was no longer ubiquitylated following activation of T cells from CD3KR retrogenic mice (Figure 5B). Interestingly, TCR expression on CD3KR DP thymocytes was upregulated more than three-fold compared with wild-type (CD3WT) mice (Figure 5C). The upregulation of TCR on DP thymocytes from CD3KR mice was not due to CD3 overexpression as the level of the green florescent protein (GFP) reporter contained within these retroviral vectors (an internal ribosome entry site-GFP) was comparable between the CD3WT and CD3KR retrogenic mice (Supplementary Figure S5C). In contrast to DP thymocytes, a 40% reduction in TCR expression was observed on SP thymocytes from CD3KR mice compared with the CD3WT mice, which is also observed in Cbl−/− and Cbl loss-of-function mutant mice (Thien et al, 2003). These data suggest that tonic CD3 ubiquitylation is required to control TCR expression on immature DP thymocytes.

Figure 5.

Regulation of TCR surface expression by CD3 tonic ubiquitylation. (A) The amino-acid sequence of the CD3 cytoplasmic domains highlighting the 37 lysine residues (bold and underlined). (B) Retrogenic mice were generated by transducing CD3ɛζ−/− bone marrow with CD3WT or CD3KR constructs as indicated, transplanting into sublethally irradiated Rag1−/− recipients and analysing 5–8 weeks after transfer. Splenic T cells were purified by MACS from either CD3WT or CD3KR retrogenic mice and activated by CD3ɛ mAb. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with CD3ζ mAb, separated by SDS–PAGE, and western blots were probed with ubiquitin mAb as in Figure 1A. The membrane was stripped and re-probed with CD3ζ mAb to show comparable CD3ζ loading. (C) Representative flow cytometry histograms are presented showing surface TCRβ expression on DP and SP thymocytes from CD3WT and CD3KR retrogenic mice (representative of 10–20 mice from more than three experiments). (D) Surface TCRβ expression on DP thymocytes of CD3WT or various CD3KR retrogenic mice, determined by flow cytometry. The difference between CD3WT and CD3δɛζKRγWT is statistically significant (P=0.008). Data represent the mean±s.e.m. of 5–20 mice from more than two experiments. A full-colour version of this figure is available at The EMBO Journal Online.

Functional redundancy in the usage of ubiquitylated CD3 cytoplasmic lysines

All four CD3 cytoplasmic domains possess lysine residues (four in CD3γ, three in CD3δ, six in CD3ɛ, and nine in CD3ζ; Figure 5A). To determine which CD3 subunits contain functional ubiquitylation sites that are sufficient to limit TCR:CD3 expression on DP thymocytes, we generated four additional groups of retrogenic mice expressing combinations of one CD3 wild-type subunit with the remainder CD3KR mutant (e.g. CD3ζWTδγɛKR encodes wild-type CD3ζ and lysine-mutated CD3δ, CD3γ, and CD3ɛ). TCR expression on DP thymocytes in the CD3δWTγɛζKR, CD3ɛWTδγζKR, and CD3ζWTδγɛKR mice was restored to wild-type levels (Figure 5D). However, the CD3γWTδɛζKR mice had higher TCR expression on DP thymocytes, indicating that the lysines in the CD3γ chain are insufficient for tonic ubiquitylation-meditated regulation of TCR expression on immature T cells. Therefore, there is functional redundancy in the usage of ubiquitylated CD3 cytoplasmic lysines and that very few lysines (3 lysines in CD3δ chain versus 37 in all the CD3 cytoplasmic domains) are sufficient to control TCR:CD3 expression.

CD3ζ monoubiquitylation is sufficient to mediate low TCR expression on DP thymocytes

Lysine residues can also be the target of other modifications, such as sumoylation, neddylation, and methylation, which may occur on CD3 molecules. None of these modifications were detectable on CD3ζ in either mature or immature T cells (Supplementary Figure S6), although we cannot exclude the possibility that increased TCR on DP thymocytes in CD3KR mice is mediated by subtle or alternate CD3ζ modifications. Furthermore, we cannot completely rule out the possibility that these mutations may affect the structure of the CD3 cytoplasmic tails, although they appear relatively unstructured except for the ITAMs (Aivazian and Stern, 2000; Sigalov et al, 2006; Xu et al, 2008). They do appear to associate with the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane via electrostatic interactions between basic CD3 residues and acidic phospholipids, which one might predict would be retained with conservative Lys:Arg substitutions.

To address these issues directly, we investigated whether attaching Ub to the carboxy-terminal end of CD3ζ was able to restore control of TCR expression. We attached a monoUb to the COOH-terminus of CD3KR (CD3KR-monoUb) to mimic the monoubiquitylated form of the TCR:CD3 complex. Two modifications were made to ensure that this Ub moiety was not further modified. First, all seven Ub lysines were mutated to arginine (K6/11/27/29/33/48/63R) to prevent polyubiquitylation (Shih et al, 2000). Second, the two C-terminal glycine residues (G75/76) were removed to prevent conjugation to endogenous Ub or another protein. We assessed TCR:CD3 complex expression on HEK-293T cells using CD3ζKR, CD3ζKR-monoUb, or an unmodified Ub attached to the CD3ζKR COOH-terminus as a control (CD3ζKR-Ub). Attaching either form of Ub to CD3ζ substantially reduced TCR expression (Supplementary Figure S7A).

As the internalization of ubiquitylated TCR:CD3 appeared to be dynamin-dependent (Figure 4A and B), and enzymatically inactive forms of dynamin act as dominant negatives and block endocytosis (Praefcke and McMahon, 2004), we reasoned that such mutants should block the internalization of an appropriately modified CD3-Ub chimera. Dominant negative dynamin had no effect on TCR expression on the CD3ζKR-Ub transfectants, suggesting that attachment of wild-type Ub to CD3ζKR led to intracellular TCR:CD3 complex retention and/or degradation (Supplementary Figure S7B). In contrast, normal expression of TCR complexes containing CD3ζKR-monoUb was completely restored by dominant negative dynamin, consistent with our observations using the dynamin inhibitor MiTMAB with DP thymocytes. Collectively, these data suggested that CD3 monoubiquitylation triggered rapid dynamin-dependent TCR internalization and lysosomal sequestration.

Retrogenic mice expressing CD3KR-monoUb showed a 50% reduction in TCR:CD3 complex expression on DP thymocytes compared with CD3WT levels, showing that ‘increased' ubiquitylation of CD3ζ on DP thymocytes leads to reduced surface TCR expression (Figure 7A). Collectively, these data are consistent with a model in which highly controlled, tonic ubiquitylation is required for fine tuning TCR:CD3 complex expression on immature DP thymocytes.

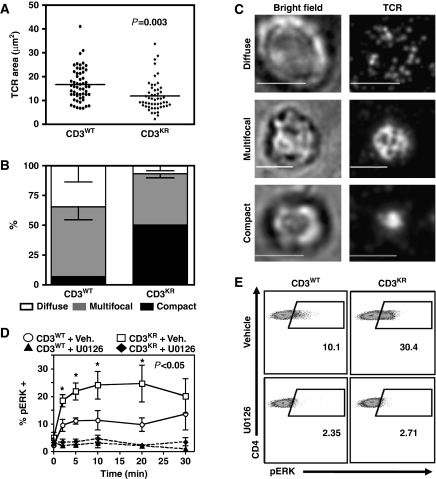

Tonic ubiquitylation controls TCR signalling in DP thymocytes and regulates T-cell development

To test whether altered tonic ubiquitylation of the TCR:CD3 complex affects TCR signalling in DP thymocytes, we measured immunological synapse (IS) formation and ERK phosphorylation status in activated CD3WT and CD3KR DP thymocytes. Earlier studies have suggested that DP thymocytes form multifocal synapses, whereas mature peripheral T cells form compact IS (Hailman et al, 2002). Thus, we used total internal reflection fluorescent microscopy with synthetic planar lipid bilayer containing unlabelled His-tagged ICAM-1 and fluorescently labelled streptavidin conjugated to biotinylated TCRβ mAbs to assess the effect of abrogated CD3 ubiquitylation on IS formation in DP thymocytes. Significant differences were observed between the pattern of IS formed by CD3WT versus CD3KR DP thymocytes 15 min poststimulation on lipid bilayers. First, the TCR contact area was significantly reduced with CD3KR DP thymocytes (Figure 6A). Second, the percentage of compact IS relative to multifocal and diffuse IS was significantly increased with CD3KR versus CD3WT DP thymocytes (Figure 6B and C). These data suggest that preventing CD3 ubiquitylation leads to IS formation that is more reminiscent of mature peripheral T cells.

Figure 6.

Impaired CD3 ubiquitylation enhances IS formation and increases ERK phosphorylation in DP thymocytes. (A–C) DP thymocytes from CD3WT or CD3KR Rg mice were purified by FACS and added to a synthetic planar lipid bilayer containing unlabelled His-tagged ICAM-1 and fluorescently labelled streptavidin conjugated to biotinylated anti-TCRβ antibodies. Interactions were fixed following 15 min stimulation, visualized using spinning disk confocal microscopy and analysed using Slidebook software. (A) The area of individual DP T-cell synapses obtained in two independent experiments. (B, C) The morphology of individual synapses were classified according to the representative images (B) and shown graphically (C—Scale bar=5 mm). (D, E) Thymocytes from CD3WT or CD3KR Rg mice were isolated, rested in 0.5% FCS RPMI for 1 h at 37°C, and then activated by crosslinking using a CD3ɛ mAb in the presence (+U0126) or absence (+Veh.) of the MEK inhibitor U0126. Thymocytes were then fixed at the indicated time, permeablized, and stained with CD4, CD8, and pERK Abs. (D) CD4+CD8+ DP thymocytes were gated and pERK expression measured. (E) Representative flow cytometry dot plots are shown 10 min after stimulation. Statistical significance was determined using an unpaired t test in Prism software.

We also assessed ERK phosphorylation following TCR stimulation of DP thymocytes by flow cytometry. A significantly increased percentage of CD3KR versus CD3WT DP thymocytes expressed pERK (Figure 6D and E). Similar observations were also made with Sla−/− DP thymocytes (Supplementary Figure S8). The specificity of these observations was confirmed by the use of the MEK inhibitor U0126. Interestingly, increased pERK was more prolonged in CD3KR DP thymocytes compared with Sla−/− thymocytes (Figure 6D; Supplementary Figure S8A). Taken together, these data suggest that blocking CD3 tonic ubiquitylation increases TCR signalling strength in immature T cells.

To determine whether tonic ubiquitylation of the TCR:CD3 complex regulates T-cell development, we analysed the distribution of DN, DP, and SP thymocytes and total thymocyte number in CD3WT, CD3KR, and CD3KR-monoUb retrogenic mice. CD3KR mice had twice as many thymocytes as CD3WT mice, whereas CD3KR-monoUb mice had substantially reduced thymic cellularity that was ∼1/10th of CD3WT mice (Figure 7B). The distribution of DN, DP, and SP thymocytes in CD3KR versus CD3WT mice was unchanged (Figure 7C and D; Supplementary Figure S9A). In contrast, CD3KR-monoUb mice had an increased percentage of DN thymocytes (Figure 7C and D). Furthermore, the number and percentage of natural regulatory T cells (Tregs) in the thymus and spleen was substantially reduced in CD3KR-monoUb mice (Figure 7E–G). Interestingly, the CD3KR-monoUb mice became sick and died 8–12 weeks post bone marrow transfer, with moderate inflammation, multifocal crypt necrosis, and enterocyte apoptosis in the small and large intestines, and vasculitis in the liver (Supplementary Figure S10 and Supplementary Table S1). Whether this disease is due to a breakdown of central tolerance as described in other mouse models with TCR hyporesponsiveness (Aguado et al, 2002; Sommers et al, 2002; Holst et al, 2008) and/or limited generation of natural Tregs in the periphery is unclear and would require further analysis. To rule out the possibility that hypo- or hyper-ubiquitylation promotes the generation of DP thymocytes in the absence of TCR, we generated retrogenic mice using CD3WT, CD3KR, and CD3KR-monoUb transduced CD3ɛζ−/− Rag1−/− bone marrow (Supplementary Figure S11). In the absence of TCR, we found little, if any, DP thymocytes in CD3WT, CD3KR, or CD3KR-monoUb retrogenic mice. Collectively, these results suggest that the altered TCR:CD3 ubiquitylation in thymocytes affects T-cell development.

Figure 7.

CD3 ubiquitylation alters TCR expression, thymic cellularity, and Treg development. Retrogenic mice were generated by reconstituting sublethally irradiated Rag1−/− recipients with transduced CD3ɛζ−/− bone marrow. Mice were analysed 5–8 weeks after transfer. Thymocytes were counted and stained with antibodies to CD4, CD8, and TCRβ, and analysed by flow cytometry. Surface TCR level on GFP+ DP thymocytes (A), GFP+ thymocyte number (B), and the percentage of GFP+ thymocytes (C) was determined. Data were gated on live, GFP+ cells, and represent the mean±s.e.m. of 10–20 mice from more than three experiments per group. (D) Representative dot plots of GFP+ thymocytes stained with antibodies to CD4 and CD8 are shown (representative of 10–20 mice from more than three experiments). (E–G) Splenocytes and thymocytes were surface stained with CD4 mAb and intracellularly stained with Foxp3 mAb. Representative dot plots of CD4+ splenic T cells from a retrogenic mouse experiment are shown (E). Bar charts show the percentage of splenic CD4+ T-cells expressing Foxp3 (F) and the number of Foxp3+ thymocytes (G). A full-colour version of this figure is available at The EMBO Journal Online.

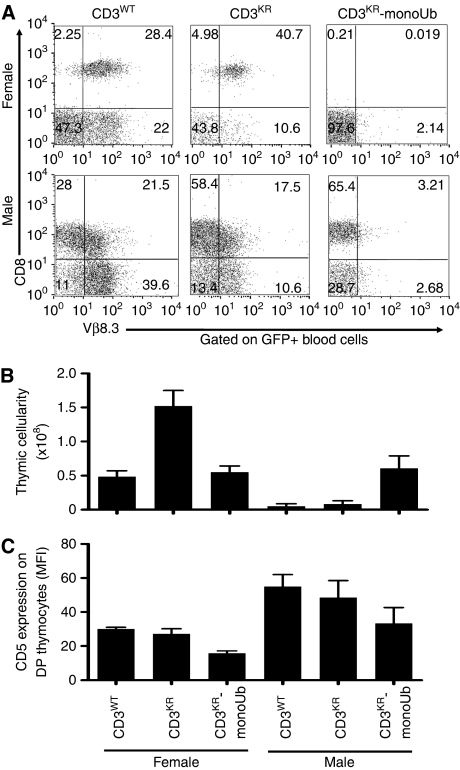

Finally, to assess whether positive and negative selection were altered by the extent of TCR:CD3 ubiquitylation, we generated retrogenic mice co-expressing either CD3WT, CD3KR, or CD3KR-monoUb with the MataHari TCR, a H-2Kb-restricted Vβ8.3+ TCR specific for the male antigen Uty (Valujskikh et al, 2002; Holst et al, 2006b). Bone marrow from male or female CD3ɛζ−/−Rag1−/− mice was transduced with retrovirus encoding the MataHari TCR and the different versions of CD3, and transplanted into irradiated Rag1−/− mice of the same sex. In female mice, where MataHari T cells are normally positive selected, we observed a uniform population of CD8+Vβ8.3+ T cells in the periphery in mice expressing CD3WT molecules (Figure 8A). However, CD3KR female mice have ∼3 times more thymocytes than CD3WT female mice, a higher CD8 SP to TCR+ DP thymocyte ratio, and a higher percentage of CD8+Vβ8.3+ T cells in the periphery (Figure 8A and B; Supplementary Figure S9B), suggesting that positive selection was enhanced when CD3 tonic ubiquitylation was blocked. Interestingly, T-cell development was blocked at the DP stage in MataHari CD3KR-monoUb female mice with very low CD5 expression on DP thymocytes, normally upregulated on positive selection (Jameson et al, 1995; Tarakhovsky et al, 1995), and no T cells found in the periphery, despite substantial thymocyte cellularity (Figure 8A–C; Supplementary Figure S12). These data suggest that the signal that normally mediates positive selection in MataHari mice may be converted into one that mediates neglect in CD3KR-monoUb MataHari female mice (Supplementary Figure S13).

Figure 8.

TCR:CD3 ubiquitylation modulates T-cell development. (A–C) Bone marrow from female or male CD3ζɛ−/−Rag1−/− mice was co-transduced with the MataHari TCRαβ and CD3WT, CD3KR, or CD3KR-monoUb. Transduced bone marrow was used to reconstitute irradiated, sex-matched Rag1−/− mice. Mice were bled and killed 6–8 weeks after transfer. Peripheral blood was stained with antibodies to CD8 and Vβ8.3 (A). Bar charts show the number of thymocytes (B) and CD5 expression on DP thymocytes (C) in each group. Data are gated on GFP+ cells and are represent the mean±s.e.m. of 5–10 mice from two experiments per group. A full-colour version of this figure is available at The EMBO Journal Online.

In male mice, CD3WT and CD3KR MataHari T cells were deleted normally, as expected, with thymic cellularity significantly reduced compared with MataHari female mice (Figure 8A–C; Supplementary Figure S12). As shown earlier, some T cells escaped negative selection in the thymus by downregulation of CD8 and/or TCR expression and appear in the periphery (Figure 8A) (Valujskikh et al, 2002). It is noteworthy that in both male and female CD3KR MataHari mice, there are significantly less CD8−Vβ8.3+ T cells in the periphery (Figure 8A), again suggesting that altered CD3 ubiquitylation can alter T-cell tolerance mechanisms. In contrast, there appeared to be no deletion in male CD3KR-monoUb MataHari mice as thymus size and cellularity, and CD5 expression on DP thymocytes were comparable to CD3WT female mice (Figure 8B and C; Supplementary Figure S12), and a uniform population of GFP+CD8+ T cells was found in the blood (Figure 8A) [note that consistent with CD3KR-monoUb mice, TCR surface expression is also low in the MataHari CD3KR-monoUb mice]. These data suggest that negative selection may be converted into positive selection in CD3KR-monoUb MataHari male mice (Supplementary Figure S13). Collectively, these findings suggest that the signalling threshold for positive and negative selection is directly regulated by tonic ubiquitylation of the TCR:CD3 complex.

Discussion

Our results show that c-Cbl-dependent, MHC-independent constitutive, tonic ubiquitylation of the TCR:CD3 complex occurs in, and is restricted to, DP thymocytes. Earlier studies had suggested that TCR:CD3 ubiquitylation was restricted to activated mature T cells (Cenciarelli et al, 1992). CD3 tonic ubiquitylation is mediated by Lck and the CD3ɛ-PRS, which may cooperatively recruit a c-Cbl:SLAP complex that subsequently mediates CD3 ubiquitylation. We further show that CD3 tonic ubiquitylation is required and sufficient for the downregulation of surface TCR expression, a hallmark of T-cell development. Our data are consistent with a model in which there is a moderate level of constitutive Lck activity, perhaps facilitated by the miR181a-mediated depletion of Src-inactivating phosphatases (Li et al, 2007b), which phosphorylates CD3 and the c-Cbl:SLAP complex that is subsequently recruited to the CD3ɛ-PRS, perhaps via Nck. Collectively, these molecular events mediate the tonic ubiquitylation of the TCR:CD3 complex in the absence of any TCR:MHC ligation. The ubiquitylated TCR:CD3 complex is internalized in a dynamin-dependent manner and transported to lysosomes for degradation mediated by LAPTM5. Clearly, there are steps in this model that require further examination. First, whether there is a direct connection between miR181a and tonic ubiquitylation remains to be determined. Second, whether Lck is directly or indirectly recruited to the CD3ɛ PRS by Nck remains to be determined. Indeed, the precise role of the CD3ɛ PRS in mediating tonic ubiquitylation remains obscure. Third, the precise fate and pathway followed by tonic ubiquitylated TCR:CD3 complexes remains to be more fully defined.

Why might tonic ubiquitylation only occur in DP thymocytes? First, the E3 ligase machinery that drives tonic ubiquitylation (c-Cbl+Slap) is predominantly expressed in immature T cells (Sosinowski et al, 2001; Molero et al, 2004; Myers et al, 2006). Although c-Cbl is expressed at higher amounts in thymocytes, compared with splenic T cells, SLAP expression is essentially restricted to DP thymocytes, which may serve to mitigate c-Cbl activity. Second, a recent study has shown that high expression of miR181a in DP thymocytes represses multiple phosphatases, which leads to increased tyrosine kinase activity and target phosphorylation (Li et al, 2007b). This may in turn lead to enhanced activation of the c-Cbl:SLAP complex.

The requirement for a c-Cbl:SLAP complex as the primary, if not sole mediator of TCR:CD3 tonic ubiquitylation, is consistent with earlier studies showing that Cbl−/− and Sla−/− mice have upregulated TCR expression on DP thymocytes and increased positive selection in DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice (Naramura et al, 1998; Sosinowski et al, 2001; Myers et al, 2006). Importantly, we also show that the modulation of TCR:CD3 ubiquitylation has a substantial effect on thymocyte cellularity, positive and negative selection, and ultimately the establishment of a peripheral T-cell pool. We propose that tonic ubiquitylation of the TCR:CD3 complex on immature thymocytes tightly regulates surface TCR expression and may help to maintain the fidelity of T-cell development.

How might the CD3ɛ-PRS be involved in mediating CD3 tonic ubiquitylation in DP thymocytes? Our data have shown that Lck is required for tonic ubiquitylation of CD3 in immature T cells. A recent study proposed that recruitment of Lck in immature T cells is mediated by the CD3ɛ-PRS in DP thymocytes (Mingueneau et al, 2008). The CD3ɛ-PRS seems to be constitutively exposed and interacts with Nck (Gil et al, 2002; Mingueneau et al, 2008; Brodeur et al, 2009; Wang et al, 2009). As ∼50% of Lck in DP thymocytes is not associated with CD4 or CD8, this free Lck may be recruited to the TCR:CD3 complex by interacting with the Nck-SH3 domain, resulting in tonic phosphorylation of CD3 chains, c-Cbl and SLAP, which in turn triggers the tonic CD3 ubiquitylation pathway. Consistent with this model, our data showed that tonic CD3 ubiquitylation is blocked and the distribution of the TCR:CD3 is altered in DP thymocytes from mice lacking CD3ɛ-PRS, Lck, c-Cbl, or SLAP.

In addition to observing increased TCR on DP thymocytes in CD3KR mice, counterintuitively, we also saw a reduction in TCR expression on SP thymocytes and peripheral T cells (Figure 5C). Interestingly, similar observations were made with the Cbl−/− or Cbl loss-of-function mutant mice (Thien et al, 2003). This phenotype may be cell extrinsic and caused by increased TCR signalling strength due to higher TCR expression on DP thymocytes (Figure 6; Supplementary Figure S8), which may lead to increased negative selection. Thus, some thymocytes, which have lower TCR expression, may successfully escape negative selection. Alternatively, lowered TCR on SP and peripheral T cells, may be cell intrinsic with ubiquitylation performing a protective role in the regulation of TCR expression in mature T cells, perhaps by limiting AP1-mediated internalization (Liu et al, 2000; Szymczak and Vignali, 2005).

Several lines of evidence suggest that the primary role of CD3 ubiquitylation in DP thymocytes is to target the TCR:CD3 complex to lysosomes for degradation thereby reducing surface TCR expression. First, earlier studies have shown that receptor monoubiquitylation mediates their internalization and lysosomal degradation (Shih et al, 2000; Haglund et al, 2003b). Our data suggest that the TCR:CD3 complex in DP thymocytes is constitutively subjected to multiple monoUb additions to multiple lysine residues throughout the CD3 cytoplasmic domains. Second, we have also shown that mimicking monoubiquitylation by expression of a CD3ζ-monoUb chimeric molecule reduces surface TCR expression on thymocytes. Third, blocking internalization with dynamin inhibitors (MiTMAB) or blocking lysosomal degradation with acidification inhibitors (NH4Cl or Concanamycin A) resulted in increased surface TCR expression on DP thymocytes. Fourth, a recent study showed that LAPTM5 mediates CD3 degradation in both thymocytes and activated T cells (Ouchida et al, 2008). Interestingly, the Ub-interacting motif of LAPTM5 is required for CD3 degradation. Our data showed that LAPTM5 and CD3 colocalize in immature DP thymocytes, which is consistent with a model in which LAPTM5 may selectively interact with ubiquitylated CD3 via its Ub interacting motif to induce CD3 lysosomal degradation. At odds with this model is the observation that TCR expression on DP thymocytes was only slightly increased in Laptm5−/− mice, in contrast to the significant increases seen with Cbl−/−, Sla−/−, Lck−/−, and Cd3eΔPRS/ΔPRS mice (Figures 1G, 2C, and 3B; Supplementary Figure S2B) (Molina et al, 1992; Sosinowski et al, 2001; Molero et al, 2004; Mingueneau et al, 2008; Ouchida et al, 2008). However, it is possible that other Ub-binding, lysosomal resident proteins cooperate with LAPTM5 to mediate TCR:CD3 sequestration and degradation.

Why might tonic CD3 ubiquitylation in DP thymocytes be important? Clearly, a key consequence of abrogating tonic CD3 ubiquitylation is increased TCR. Our data suggest that this leads to altered IS formation and contraction, and increased Erk phosphorylation, thereby shifting the signalling threshold for positive and negative selection, and regulatory T-cell development. Earlier studies have suggested that the type of synapse that forms between DP thymocytes and thymic epithelial cells (TECs) alters their selection fate (Hailman et al, 2002; Richie et al, 2002; Ebert et al, 2008). Thus, tonic ubiquitylation may help to ensure that the appropriate DP:TEC interactions are maintained for optimal positive and negative selection. What remains unclear is whether modulated IS formation and signalling are a direct consequence of increased TCR or are independently regulated by tonic CD3 ubiquitylation.

Understanding the role of CD3 tonic ubiquitylation in immature T cells may also provide insight into the role/contribution of CD3 ubiquitylation in activated T cells, whether this is mediated by the same, related or distinct molecules, and if the fate of ubiquitylated CD3 following TCR ligation is the same or different. Our results suggest that disruption of TCR expression control in DP thymocytes can lead to increased TCR signalling, altered positive and negative selection, and reduced Treg development. Although profound autoimmunity was not observed in CD3KR mice, it is possible that more chronic conditions may develop with time as has been observed in mice possessing mutations that disrupt TCR expression (Naramura et al, 2002). Clearly, this is a topic that will require further study.

Materials and methods

Mice

Rag1−/− (recombination activating gene 1) and C57BL/6J mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories. B2m−/−Abb−/− mice (β-2 microglobulin and MHC class II H-2A β chain, respectively) were purchased from Taconic Farms. Thymi from Cbl−/− (c-Cbl—Casitas B-lineage lymphoma) mice were provided by M Naramura and H Band. Thymi from CD3eΔPRS/ΔPRS mice were provided by B Malissen. Thymi from Lck−/− and Fyn−/− mice were provided by S Hayes. Thymi from Slap−/− mice were provided by L Dragone. CD3ɛζ-KO mice lacking all four CD3 chains were generated by crossing CD3eΔP/ΔP mice with CD3ζ−/− mice as described earlier (Wang et al, 1999; Szymczak et al, 2004; Holst et al, 2008). All animal experiments were performed in an AAALAC-accredited, Helicobacter-free, specific pathogen-free facility following national, state, and institutional guidelines. Animal protocols were approved by St Jude Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Generation of CD3 multicistronic vectors

See Supplementary data.

Generation of retroviral producer cells

See Supplementary data.

Retroviral-mediated stem cell gene transfer

Retroviral transduction of murine bone marrow cells was performed as described earlier (Holst et al, 2006a, 2006b, 2008). Briefly, we harvested bone marrow from 8- to 10-week-old donor mice 48 h after treatment with 150 mg/kg 5-fluoruracil (Pharmacia & UpJohn). Bone marrow cells were single cell suspended and cultured in complete DMEM with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS), murine IL-3 (20 ng/ml), human IL-6 (50 ng/ml), and murine SCF (50 ng/ml) (Biosource-Invitrogen) for 48 h. Cells were subsequently co-cultured for a further 48 h with irradiated (1200 rads) retroviral producer cell lines plus polybrene (6 μg/ml) and cytokines as detailed above. Transduced bone marrow cells were collected, washed, and cells resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 2% FBS with heparin (20 U/ml). Bone marrow cells (4 × 106 per mouse) were injected via the tail vein into irradiated (450 rads) Rag1−/− recipient mice. Retrogenic mice were analysed 6–12 weeks after bone marrow transplant.

Flow cytometric analysis, intracellular staining, and cell sorting

See Supplementary data.

CD3ɛ crosslinking and intracellular staining

See Supplementary data.

Confocal microscopy

Thymocytes purified by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) were fixed with 4% formaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100. These fixed cells were plated to the chamber of the glass slide (Nunc), which was pretreated with 0.1% Polyethyleneimine solution (Sigma). After 1 h incubation at room temperature, the chamber slide was washed twice with PBS and then treated with Image-iT FX signal enhancer (Invitrogen) for 30 min. Primary Abs in 2% milk solution were added into the chamber and the slide was kept at 4°C over night. The slide was washed extensively with PBS, and fluorchrome labelled secondary Abs diluted in 2% milk solution were added into the chamber and kept at room temperature for 1 h. After washing the chamber four times with PBS, the stained cells were mounted using Prolong Gold antifade reagent with DAPI (Invitrogen). All images were taken using a Zeiss LSM 510 NLO META confocal microscope. CD3ζ (H146) mAb was conjugated with Alexa-647 using an Alexa Fluor labelling kit (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's instructions. LAPTM5 mAb was provided from Ji-yang Wang, RIKEN, Yokohama, Japan. An Alexa-488-conjugated mAb against rabbit IgG was purchased from Invitrogen.

Lipid bilayers and microscopic analyses

See Supplementary data.

RNA, cDNA, and quantitative real-time PCR

See Supplementary data.

Immunoprecipitation and western blotting

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting were performed as described earlier (Li et al, 2007a). Briefly, cells were lysed with lysis buffer containing 1% Triton X-100, 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.6), 300 mM NaCl, 2 mM Pefabloc, 10 μg/ml Aprotinin, 10 μg/ml Leupeptin, 1 μg/ml Pepstatin (Roche), and 10 mM N-ethylmaleimide (Sigma) on ice for 30 min, followed by centrifugation at 15 000 g for 15 min. For protein analysis, 20 μl of lysate was collected, gel separated, and immunoblotted with indicated antibodies. Antibodies against the following proteins were used: CD3ɛ (HMT3.1 mAb) (Szymczak et al, 2004), CD3ζ (H146-968 mAb, gift from Ralph Kubo, Cytel Corp., San Diego, CA) (Liu et al, 2000), α-Tubulin (Sigma), CD3δ and CD3γ (two rabbit polyclonal antisera that were generated in our laboratory) (Holst et al, 2008). For immunoprecipitation, 1 ml lysate was precleared with protein G-sepharose beads and further immunoprecipitated with a polyclonal antisera against CD3ζ (551-ζ, gift from David Wiest, Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, PA) conjugated Protein G-sepharose beads. Immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS–PAGE (Invitrogen Life Technologies), and blots were probed with mAbs against Ub (P4D1; Santa Cruz), polyUb (FK1, Millipore), K63Ub (HWA4C4; Wang H, submitted for publication), Sumo-1 (ZYMED), Nedd8 (gift from Brenda Schulman, SJCRH, Memphis, TN), or pan methyl lysine (Abcam). Blots were developed using enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences) and autoradiography. Membranes were stripped and blots re-probed with CD3ζ mAb (H146-968).

Transient transfection of HEK-293T cells

See Supplementary data.

Thymic organ culture

See Supplementary data.

Histological examination

See Supplementary data.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Mark Davis and Johannes Huppa for assistance and advice with establishing the lipid bilayer/spinning disk confocal microscopy system; Doug Green for helpful comments on the manuscript; Dave Wiest, Brenda Schulman, and Ralph Kubo for reagents; Kelli Boyd (Animal Resource Center, St Jude Children's Research Hospital) for histological analysis; Karen Forbes for animal colony management; R Cross, G Lennon, S Morgan, J Rogers, and Y He for FACS; Z Liu for providing neonatal thymi; and the Vignali laboratory for assistance with bone marrow harvesting. This work was largely supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (AI52199), a Cancer Center Support CORE grant (CA21765) and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC) to DAAV. HB was supported by the NIH (CA087986, CA99163).

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Aguado E, Richelme S, Nunez-Cruz S, Miazek A, Mura AM, Richelme M, Guo XJ, Sainty D, He HT, Malissen B, Malissen M (2002) Induction of T helper type 2 immunity by a point mutation in the LAT adaptor. Science 296: 2036–2040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aivazian D, Stern LJ (2000) Phosphorylation of T cell receptor zeta is regulated by a lipid dependent folding transition. Nat Struct Biol 7: 1023–1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluestone JA, Pardoll D, Sharrow SO, Fowlkes BJ (1987) Characterization of murine thymocytes with CD3-associated T-cell receptor structures. Nature 326: 82–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodeur JF, Li S, Martins MS, Larose L, Dave VP (2009) Critical and multiple roles for the CD3epsilon intracytoplasmic tail in double negative to double positive thymocyte differentiation. J Immunol 182: 4844–4853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadwell K, Coscoy L (2005) Ubiquitination on nonlysine residues by a viral E3 ubiquitin ligase. Science 309: 127–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenciarelli C, Hou D, Hsu KC, Rellahan BL, Wiest DL, Smith HT, Fried VA, Weissman AM (1992) Activation-induced ubiquitination of the T cell antigen receptor. Science 257: 795–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clevers H, Alarcon B, Wileman T, Terhorst C (1988) The T cell receptor/CD3 complex: a dynamic protein ensemble. Annu Rev Immunol 6: 629–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels MA, Teixeiro E, Gill J, Hausmann B, Roubaty D, Holmberg K, Werlen G, Hollander GA, Gascoigne NR, Palmer E (2006) Thymic selection threshold defined by compartmentalization of Ras/MAPK signalling. Nature 444: 724–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert PJ, Ehrlich LI, Davis MM (2008) Low ligand requirement for deletion and lack of synapses in positive selection enforce the gauntlet of thymic T cell maturation. Immunity 29: 734–745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimuro M, Yokosawa H (2005) Production of antipolyubiquitin monoclonal antibodies and their use for characterization and isolation of polyubiquitinated proteins. Methods Enzymol 399: 75–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil D, Schamel WW, Montoya M, Sanchez-Madrid F, Alarcon B (2002) Recruitment of Nck by CD3 epsilon reveals a ligand-induced conformational change essential for T cell receptor signaling and synapse formation. Cell 109: 901–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glickman MH, Ciechanover A (2002) The ubiquitin-proteasome proteolytic pathway: destruction for the sake of construction. Physiol Rev 82: 373–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg AL (2003) Protein degradation and protection against misfolded or damaged proteins. Nature 426: 895–899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haglund K, Di Fiore PP, Dikic I (2003a) Distinct monoubiquitin signals in receptor endocytosis. Trends Biochem Sci 28: 598–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haglund K, Sigismund S, Polo S, Szymkiewicz I, Di Fiore PP, Dikic I (2003b) Multiple monoubiquitination of RTKs is sufficient for their endocytosis and degradation. Nat Cell Biol 5: 461–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hailman E, Burack WR, Shaw AS, Dustin ML, Allen PM (2002) Immature CD4(+)CD8(+) thymocytes form a multifocal immunological synapse with sustained tyrosine phosphorylation. Immunity 16: 839–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochstrasser M (2006) Lingering mysteries of ubiquitin-chain assembly. Cell 124: 27–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holst J, Szymczak-Workman AL, Vignali KM, Burton AR, Workman CJ, Vignali DA (2006a) Generation of T-cell receptor retrogenic mice. Nat Protoc 1: 406–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holst J, Vignali KM, Burton AR, Vignali DA (2006b) Rapid analysis of T-cell selection in vivo using T cell-receptor retrogenic mice. Nat Methods 3: 191–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holst J, Wang H, Eder KD, Workman CJ, Boyd KL, Baquet Z, Singh H, Forbes K, Chruscinski A, Smeyne R, van Oers NS, Utz PJ, Vignali DA (2008) Scalable signaling mediated by T cell antigen receptor-CD3 ITAMs ensures effective negative selection and prevents autoimmunity. Nat Immunol 9: 658–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou D, Cenciarelli C, Jensen JP, Nguygen HB, Weissman AM (1994) Activation-dependent ubiquitination of a T cell antigen receptor subunit on multiple intracellular lysines. J Biol Chem 269: 14244–14247 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jameson SC, Hogquist KA, Bevan MJ (1995) Positive selection of thymocytes. Annu Rev Immunol 13: 93–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearse KP, Roberts JL, Munitz TI, Wiest DL, Nakayama T, Singer A (1994) Developmental regulation of alpha beta T cell antigen receptor expression results from differential stability of nascent TCR alpha proteins within the endoplasmic reticulum of immature and mature T cells. EMBO J 13: 4504–4514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearse KP, Takahama Y, Punt JA, Sharrow SO, Singer A (1995) Early molecular events induced by T cell receptor (TCR) signaling in immature CD4+ CD8+ thymocytes: increased synthesis of TCR-alpha protein is an early response to TCR signaling that compensates for TCR-alpha instability, improves TCR assembly, and parallels other indicators of positive selection. J Exp Med 181: 193–202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klausner RD, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Bonifacino JS (1990) The T cell antigen receptor: insights into organelle biology. Annu Rev Cell Biol 6: 403–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosugi A, Weissman AM, Ogata M, Hamaoka T, Fujiwara H (1992) Instability of assembled T-cell receptor complex that is associated with rapid degradation of zeta chains in immature CD4+CD8+ thymocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89: 9494–9498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacorazza HD, Nikolich-Zugich J (2004) Exclusion and inclusion of TCR alpha proteins during T cell development in TCR-transgenic and normal mice. J Immunol 173: 5591–5600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Wang Y, Forbes K, Vignali KM, Heale BS, Saftig P, Hartmann D, Black RA, Rossi JJ, Blobel CP, Dempsey PJ, Workman CJ, Vignali DA (2007a) Metalloproteases regulate T-cell proliferation and effector function via LAG-3. EMBO J 26: 494–504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li QJ, Chau J, Ebert PJ, Sylvester G, Min H, Liu G, Braich R, Manoharan M, Soutschek J, Skare P, Klein LO, Davis MM, Chen CZ (2007b) miR-181a is an intrinsic modulator of T cell sensitivity and selection. Cell 129: 147–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu HY, Rhodes M, Wiest DL, Vignali DAA (2000) On the dynamics of TCR:CD3 complex cell surface expression and downmodulation. Immunity 13: 665–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire JE, McCarthy SA, Singer A, Singer DS (1990) Inverse correlation between steady-state RNA and cell surface T cell receptor levels. FASEB J 4: 3131–3134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmor MD, Yarden Y (2004) Role of protein ubiquitylation in regulating endocytosis of receptor tyrosine kinases. Oncogene 23: 2057–2070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mingueneau M, Sansoni A, Gregoire C, Roncagalli R, Aguado E, Weiss A, Malissen M, Malissen B (2008) The proline-rich sequence of CD3epsilon controls T cell antigen receptor expression on and signaling potency in preselection CD4+CD8+ thymocytes. Nat Immunol 9: 522–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molero JC, Jensen TE, Withers PC, Couzens M, Herzog H, Thien CB, Langdon WY, Walder K, Murphy MA, Bowtell DD, James DE, Cooney GJ (2004) c-Cbl-deficient mice have reduced adiposity, higher energy expenditure, and improved peripheral insulin action. J Clin Invest 114: 1326–1333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina TJ, Kishihara K, Siderovski DP, van EW, Narendran A, Timms E, Wakeham A, Paige CJ, Hartmann KU, Veillette A (1992) Profound block in thymocyte development in mice lacking p56lck. Nature 357: 161–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay D, Riezman H (2007) Proteasome-independent functions of ubiquitin in endocytosis and signaling. Science 315: 201–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy MA, Schnall RG, Venter DJ, Barnett L, Bertoncello I, Thien CB, Langdon WY, Bowtell DD (1998) Tissue hyperplasia and enhanced T-cell signalling via ZAP-70 in c-Cbl-deficient mice. Mol Cell Biol 18: 4872–4882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers MD, Sosinowski T, Dragone LL, White C, Band H, Gu H, Weiss A (2006) Src-like adaptor protein regulates TCR expression on thymocytes by linking the ubiquitin ligase c-Cbl to the TCR complex. Nat Immunol 7: 57–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama T, Singer A, Hsi ED, Samelson LE (1989) Intrathymic signalling in immature CD4+CD8+ thymocytes results in tyrosine phosphorylation of the T-cell receptor zeta chain. Nature 341: 651–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naramura M, Jang IK, Kole H, Huang F, Haines D, Gu H (2002) c-Cbl and Cbl-b regulate T cell responsiveness by promoting ligand-induced TCR down-modulation. Nat Immunol 3: 1192–1199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naramura M, Kole HK, Hu RJ, Gu H (1998) Altered thymic positive selection and intracellular signals in Cbl-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 15547–15552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouchida R, Yamasaki S, Hikida M, Masuda K, Kawamura K, Wada A, Mochizuki S, Tagawa M, Sakamoto A, Hatano M, Tokuhisa T, Koseki H, Saito T, Kurosaki T, Wang JY (2008) A lysosomal protein negatively regulates surface T cell antigen receptor expression by promoting CD3zeta-chain degradation. Immunity 29: 33–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J, Schwartz D, Elias JE, Thoreen CC, Cheng D, Marsischky G, Roelofs J, Finley D, Gygi SP (2003) A proteomics approach to understanding protein ubiquitination. Nat Biotechnol 21: 921–926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Praefcke GJ, McMahon HT (2004) The dynamin superfamily: universal membrane tubulation and fission molecules? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5: 133–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao N, Miyake S, Reddi AL, Douillard P, Ghosh AK, Dodge IL, Zhou P, Fernandes ND, Band H (2002) Negative regulation of Lck by Cbl ubiquitin ligase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 3794–3799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richie LI, Ebert PJ, Wu LC, Krummel MF, Owen JJ, Davis MM (2002) Imaging synapse formation during thymocyte selection: inability of CD3zeta to form a stable central accumulation during negative selection. Immunity 16: 595–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih SC, Sloper-Mould KE, Hicke L (2000) Monoubiquitin carries a novel internalization signal that is appended to activated receptors. EMBO J 19: 187–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigalov AB, Aivazian DA, Uversky VN, Stern LJ (2006) Lipid-binding activity of intrinsically unstructured cytoplasmic domains of multichain immune recognition receptor signaling subunits. Biochem 45: 15731–15739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommers CL, Park CS, Lee J, Feng C, Fuller CL, Grinberg A, Hildebrand JA, Lacana E, Menon RK, Shores EW, Samelson LE, Love PE (2002) A LAT mutation that inhibits T cell development yet induces lymphoproliferation. Science 296: 2040–2043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosinowski T, Killeen N, Weiss A (2001) The Src-like adaptor protein downregulates the T cell receptor on CD4+CD8+ thymocytes and regulates positive selection. Immunity 15: 457–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymczak A, Vignali DAA (2005) Plasticity and rigidity in AP-2-mediated internalization of the T cell receptor:CD3 complex. J Immunol 174: 4153–4160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymczak AL, Workman CJ, Gil D, Dilioglou S, Vignali KM, Palmer E, Vignali DA (2005) The CD3epsilon proline-rich sequence, and its interaction with Nck, is not required for T cell development and function. J Immunol 175: 270–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymczak AL, Workman CJ, Wang Y, Vignali KM, Dilioglou S, Vanin EF, Vignali DA (2004) Correction of multi-gene deficiency in vivo using a single ‘self-cleaving' 2A peptide-based retroviral vector. Nat Biotechnol 22: 589–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tailor P, Tsai S, Shameli A, Serra P, Wang J, Robbins S, Nagata M, Szymczak-Workman AL, Vignali DA, Santamaria P (2008) The proline-rich sequence of CD3epsilon as an amplifier of low-avidity TCR signaling. J Immunol 181: 243–255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J, Sawasdikosol S, Chang JH, Burakoff SJ (1999) SLAP, a dimeric adapter protein, plays a functional role in T cell receptor signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 9775–9780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarakhovsky A, Kanner SB, Hombach J, Ledbetter JA, Muller W, Killeen N, Rajewsky K (1995) A role for CD5 in TCR-mediated signal transduction and thymocyte selection. Science 269: 535–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thien CB, Langdon WY (2001) Cbl: many adaptations to regulate protein tyrosine kinases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2: 294–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thien CB, Scaife RM, Papadimitriou JM, Murphy MA, Bowtell DD, Langdon WY (2003) A mouse with a loss-of-function mutation in the c-Cbl TKB domain shows perturbed thymocyte signaling without enhancing the activity of the ZAP-70 tyrosine kinase. J Exp Med 197: 503–513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valujskikh A, Lantz O, Celli S, Matzinger P, Heeger PS (2002) Cross-primed CD8(+) T cells mediate graft rejection via a distinct effector pathway. Nat Immunol 3: 844–851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Wang N, Whitehurst CE, She J, Chen J, Terhorst C (1999) T lymphocyte development in the absence of CD3 epsilon or CD3 gamma delta epsilon zeta. J Immunol 162: 88–94 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Deng L, Hong M, Akkaraju GR, Inoue J, Chen ZJ (2001) TAK1 is a ubiquitin-dependent kinase of MKK and IKK. Nature 412: 346–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Matsuzawa A, Brown SA, Zhou J, Guy CS, Tseng PH, Forbes K, Nicholson TP, Sheppard PW, Hacker H, Karin M, Vignali DA (2008) Analysis of nondegradative protein ubiquitylation with a monoclonal antibody specific for lysine-63-linked polyubiquitin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 20197–20202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Becker D, Vass T, White J, Marrack P, Kappler JW (2009) A conserved CXXC motif in CD3epsilon is critical for T cell development and TCR signaling. PLoS Biol 7: e1000253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C, Gagnon E, Call ME, Schnell JR, Schwieters CD, Carman CV, Chou JJ, Wucherpfennig KW (2008) Regulation of T cell receptor activation by dynamic membrane binding of the CD3epsilon cytoplasmic tyrosine-based motif. Cell 135: 702–713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P, Peng J (2008) Characterization of polyubiquitin chain structure by middle-down mass spectrometry. Anal Chem 80: 3438–3444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.