Abstract

The study used person-oriented analyses to identify subgroups of individuals who exhibit different patterns of depressive and anxiety disorders over the course of adolescence and young adulthood. Using latent class growth analysis, six trajectory classes were identified. Two classes were mainly characterized by depressive disorders; one was mainly characterized by anxiety disorders; two were characterized by temporally different patterns of comorbidity; and one class was characterized by the absence of psychopathology. Classes characterized largely by depressive disorders differed in persistence and degree of comorbidity with anxiety disorders. Classes that were characterized by anxiety disorders differed in persistence, age of onset, and constellation of specific anxiety disorders. Female participants were more likely to belong to classes characterized by fluctuations in the course of depressive and anxiety disorders; sex differences were not observed in classes characterized by persistent depressive and anxiety disorders. Offspring of depressed parents were more likely to have a depressive course, whereas offspring of parents with anxiety disorders tended to have a course characterized by anxiety disorder. The findings indicate that several subgroups of adolescents exist with distinct longitudinal trajectories of depressive and anxiety disorders, and these trajectory classes are associated with different risk factors.

Keywords: depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, comorbidity, transmission, longitudinal studies

Depressive and anxiety disorders frequently co-occur in both children and adults [1,2]. For example, in the National Comorbidity Study - Replication, of individuals with a depressive disorder, 59% had a lifetime diagnosis of an anxiety disorder [3]. In her review, Clark [4] found that 56% of individuals with a depressive disorder had a lifetime anxiety disorder; rates of depressive disorders in individuals with anxiety disorders varied from 20%–63%, depending on the type of anxiety disorder.

Many studies have examined the relationship between depressive and anxiety disorders over time. One methodology relied on cross-sectional and retrospective designs, and generally found that the onset of anxiety disorders typically occurs before the onset of depressive disorders in adults [3–7] and youth [8], although dysthymia was found to precede anxiety disorders in a few studies [7,9]. It is unclear how recall biases influence these results and these cross-sectional studies have not focused on bidirectional relationships between these disorders.

A second approach has involved examining temporal associations between depressive and anxiety disorders using prospective longitudinal designs with clinical, community, and high-risk samples of children, adolescents, and adults. These methods provide the opportunity to examine bidirectional associations between disorders and developmental effects that may partially account for comorbidity. Studies of high-risk samples, as indexed by a family history of depressive disorders [10–12], and community samples of youth who are assessed through childhood and/or adolescence [13–15] find that anxiety often precedes depressive disorders throughout childhood and adolescence. Studies of clinical populations with longitudinal assessments of psychopathology find bidirectional relationships between depressive and anxiety disorders [16,17] in samples of youth. Existing longitudinal research, however, has largely relied on follow-up periods within the same broad developmental period (i.e., childhood; adolescence) or between adjacent developmental periods (e.g., childhood and early adolescence).

A third approach has been to examine the structure of internalizing psychopathology over time [18–20]. These methods conceptualize depressive and anxiety disorders as resulting from shared underlying vulnerability factors. For example, two recent longitudinal epidemiological studies examined the relation between depressive and anxiety disorders over multiple developmental periods and found that both shared and unique factors influence depression and anxiety [18,20].

Another potential approach to studying the longitudinal relation between depressive and anxiety disorders involves examining within-person trajectories of depressive and anxiety disorders over time using latent growth curve modeling or hierarchical linear modeling procedures. A number of studies have used these techniques to examine changes in depressive symptoms across adolescence [21] and from adolescence through early young adulthood [22–24]. Others have examined the course of depressive disorders in conjunction with the development of other disorders during adolescents [25–27]; however, we are not aware of any study examining the simultaneous trajectory of depressive and anxiety disorders across multiple developmental periods.

Studies examining the relation between depressive and anxiety disorder using variable-centered data analytic approaches assume that associations between variables are largely the same across all individuals in a population. However, it is possible that distinct subtypes of individuals demonstrate different relations between depressive and anxiety disorders over time. Person-centered approaches, like growth curve analysis, allow for heterogeneity of developmental trajectories but do not identify subgroups of individuals who exhibit similar trajectories. In order to detect such unobserved subgroups, it is necessary to utilize newer person-centered data analytic approaches designed to identify distinct trajectory classes [28], such as latent class growth analysis (LCGA) [29]. LCGA is a longitudinal extension of latent class analysis that examines the possibility that relatively homogenous subgroups of individuals can be extracted from longitudinal data based on the growth trajectory of individuals. Additionally, in this analytic approach, the trajectories of depressive and anxiety disorders can be estimated simultaneously. No studies, to our knowledge, have examined the conjoint trajectories of depressive and anxiety disorders simultaneously using this approach.

The present study examines the conjoint trajectories of depressive and anxiety disorders from adolescence through late young adulthood in the Oregon Adolescent Depression Project (OADP) [30] using LCGA [29]. Based on findings that anxiety disorders typically precede depressive disorders, we expected to identify a class of individuals who have an initially high probability of anxiety disorder that precedes an increasing probability of depressive disorder. Additionally, based on theory and empirical evidence that depressive and anxiety disorders have both overlapping and distinct vulnerabilities [31,32], we expected to find a class of individuals with high probabilities of having both depressive and anxiety disorders; depressive disorders only; anxiety disorders only; and neither depressive nor anxiety disorders. As anxiety disorders tend to be relatively persistent, we anticipated finding a class of individuals with a consistently high probability of anxiety disorder over time. Finally, as depressive disorders can be chronic or episodic, we anticipated that several trajectory classes of depressive disorders would be identified that differ with respect to persistence over time.

To assess the meaning and validity of the trajectory classes, we explored whether the identified classes were associated with different patterns of internal and external correlates. These patterns might allow for the identification of common and specific risk factors for various forms of internalizing psychopathology. For example, shared risk factors associated with both trajectories of depressive and anxiety disorders could form the basis for general preventative efforts. Conversely, unique risk factors might highlight a group with specific temporal patterns of risk, which would suggest timing for prevention strategies. We examined four sets of factors that may be associated with depressive and anxiety disorders. First, we tested whether trajectories differed as a function of the specific depressive and anxiety disorder(s) present. Additionally, as both depressive and anxiety disorders frequently co-occur with substance use disorders (SUD; 33), we examined the associations between trajectory classes and lifetime SUD. Some suggest that comorbidity between SUD and depressive disorders represents a distinct subtype of disorder, which may partially explain observed heterogeneity of the course of disorder (34,35).

Second, we examined associations between family history of psychopathology and class membership. Parental depression is one of the best established risk factors for developing a depressive disorder [36]. Similarly, parental anxiety disorders are associated with elevated rates of anxiety disorders [37,38]. We expected that trajectory classes characterized by a preponderance of depression would be associated with parental history of depressive disorders, and trajectory classes that were characterized by anxiety would be associated with parental history of anxiety disorders. Additionally, there is conflicting evidence concerning the independent or co-transmission of internalizing disorders and SUD. Some work finds that offspring of parents with SUD develop later depressive and anxiety disorders [39,40]; while others (41) do not. Thus, we examine the associations between class membership and parental SUD.

Female gender is a robust correlate of both depressive and anxiety disorders [42]. Hence, we also examined the association between gender and class membership.

Fourth, we explored associations between retrospective measures of childhood physical and sexual abuse and trajectory class membership, as early adversity has been found to be associated with onset of both mood and anxiety disorders [43], as well as with persistence of mood disorders [44].

Method

Participants

The OADP [30] is a longitudinal study of a large cohort of high school students who were assessed twice during adolescence, a third time at an average age of 24, and a fourth time at an average age of 30. Participants were randomly selected from nine high schools in western Oregon. A total of 1,709 adolescents (ages 14–18; mean age 16.6, SD = 1.2) completed the initial (T1) assessments between 1987 and 1989, with a 61% participation rate. Approximately one year later, 1,507 of the adolescents (88%) returned for a second evaluation (T2). Written informed consent was obtained from each participant (and guardian when participant was under 18). Differences between the sample and the larger population from which it was selected, and between participants and those who declined to participate or dropped out of the study before T2, were small [30].

All adolescents with a history of major depressive disorder (MDD) (n = 360) or a history of non-mood disorders (n = 284), and a random sample of adolescents with no history of psychopathology by T2 (n = 457) were invited to participate in a third (T3) evaluation. All non-white T2 participants were retained in the T3 sample to maximize ethnic diversity. Of the 1,101 T2 participants selected for a T3 interview, 941 (85%) completed the evaluation. T2 diagnostic groups did not differ on participation rates at T3. At age 30, all T3 participants were asked to complete another interview assessment. Of the 941 who participated in the T3 assessment, 816 (87%) completed the T4 assessment.

We assessed lifetime psychopathology in the biological parents of the OADP participants near the time of the T3 evaluation. Family history data were also obtained from the OADP participants, and when a parent could not be directly interviewed, informant data were obtained from a second informant (generally the co-parent or a sibling). Of the 1,101 offspring selected for a T3 interview, diagnostic information on at least one parent was available for 801 (72.7%).

All participants who completed the T1 assessment were eligible for inclusion in the present study. The 56 participants with a lifetime diagnosis of a bipolar spectrum disorder and/or a psychotic disorder were excluded, yielding a final N of 1653. A total of 768 participants were assessed at all four time points; 121 at three time points; 570 at two time points; and 194 at one time point. All participants had lifetime diagnostic information through at least age 14. Differences between those who participated in T3, but not T4, and those who participated in T3 and T4 were small [20].

Measures

Diagnostic Measures

At T1 and T2, participants were interviewed with a version of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (K-SADS) [45], which combined features of the Epidemiologic and Present Episode versions, and included additional items to derive Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd edition revised (DSM-III-R) [46] diagnoses. At T3 and T4 participants were interviewed using the Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation (LIFE) [47], which elicited detailed information about the onset and course of psychiatric disorders since the previous evaluation. Episodes may have occurred at any point during the follow-up interval. Diagnoses were based on DSM-III-R criteria for T3 and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) [48] criteria for T4. Based on audiotaped interviews (ns ranged from 124–233), the interrater reliability for depressive disorders (MDD or dysthymia) was .82 at T1; 1.00 at T2; .86 at T3; and .81 at T4 . The interrater reliability for anxiety disorders was .76 at T1; .80 at T2; .87 at T3; and .76 at T4. In the present study we include generalized anxiety disorder (GAD); overanxious disorder; post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD); panic disorder; agoraphobia; social phobia; simple phobia; obsessive-compulsive disorder; and separation anxiety disorder as specific anxiety disorder diagnoses.

The interrater reliability for SUD was .89 at T1; .84 at T2 ; .81 at T3 ; and .79 at T4 for alcohol abuse/dependence; .90 for cannabis abuse/dependence; and .73 for hard drug abuse/dependence. Recent work finds evidence that these disorders are best represented by a single liability dimension (49) and a large percentage of substance-users engage in polysubstance use (50,51). Thus, we propose to include AUD and DUD as a single SUD outcome.

Biological parents of OADP participants were interviewed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, non-patient version (SCID-NP) [52]. Interviews were conducted without knowledge of the offspring's diagnoses. The interrater reliability of lifetime diagnoses (based on 184 randomly selected interviews) were excellent for MDD (K = .94), any anxiety disorder (κ = .90), alcohol abuse/dependence (κ = .86), and drug abuse/dependence (κ = .89).

Family history data were collected from the original OADP participants and at least one other family member using a modified version of the Family Informant Schedule and Criteria (FISC) [53], supplemented with items necessary to derive DSM-IV diagnoses. The interrater reliability of lifetime diagnoses (based on 242 randomly selected interviews) were good-excellent for MDD (K = .90), any anxiety disorder (κ = .77), alcohol abuse/dependence (κ = .90), and drug abuse/dependence (κ = .82).

As multiple data sources were available for most parents, we derived lifetime best-estimate DSM-IV diagnoses from all available information [54]. Two diagnosticians, from a team of four senior clinicians, independently derived best-estimate diagnoses without knowledge of offspring diagnoses. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. Interrater reliability of the independently derived best-estimate diagnoses prior to the resolution of discrepancies was excellent for MDD (κ = .91), any anxiety disorder (κ = .94), alcohol abuse/dependence (κ = .97), and drug abuse/dependence (κ = .96).

Parental psychopathology was scored as the proportion of parents with each class of disorder. For example, a proband with one of two parents with a depressive disorder would have a score of .5, whereas a proband with two of two parents with a depressive disorder would have a score of 1.0. This decision was informed by a recent study that compared associations between different metrics of family history scores and offspring disorder (55), which found proportional scores demonstrating slightly stronger associations than dichotomous scores. Importantly, these differences in strength of associations did not increase Type I error rates as the 95% confidence intervals were largely unaltered. We employed a similar approach in examining the influence of parental interview status, which was indexed by the proportion of parents who completed a direct interview For example, a proband with one parent who completed a diagnostic interview would have a score of .5, whereas a proband with two parents who completed a diagnostic interview would have a score of 1.0.

Participant interviews at T3 and T4 and interviews with their parents were conducted by telephone, which generally yields comparable results to face-to-face interviews [56,57]. Most interviewers had advanced degrees in a mental health field and several years of clinical experience.

Childhood Adversity and Abuse

As part of the T3 assessment, participants were assessed for physical and sexual abuse through age 18 or when the participant left their parent's home using items from the Assessing Environment-III (AE-III) [58] and the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) [59]. We selected 38 items that varied in the intensity and type of abuse. This report uses a single aggregate scale (α = .78).

Data analysis

A record was created for each participant indicating whether a depressive or anxiety disorder occurred, either as a new onset or as a continuation of a previous episode or disorder, during the following time intervals: lifetime through age 14; ages 15–16; ages 17–18; ages 19–20; ages 21–22; ages 23–24; ages 25–26; ages 27–28; and ages 29–30. Thus, these reflect period prevalence rates and were not directly tied to the four assessment points. Although some individuals were assessed at only one time point, they could contribute data on more than one age interval. We aggregated lifetime diagnoses through age 14 as one data point because the incidence of depressive disorders increases after age 14. Caucasian OADP participants with no history of psychopathology through T2 were undersampled in the T3 follow-up; hence in all statistical analyses offspring were weighted as a function of their probability of being selected at T3. However, the numbers and proportions of participants, presented for descriptive purposes, are unweighted.

Latent class growth analyses were performed using Mplus, version 4.1 [60]. Model solutions were evaluated on the basis of the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) and entropy [28]. The BIC has been shown to be a robust indicator of the preferred k class solution [61]. Lower BIC values indicate better model fit. We also present the Akaike Information Criteria (AIC), which is an additional criteria for model selection. However, recent simulation work [62] suggests that the AIC over-extracts classes. We also present entropy, which is an index for assessing the precision of assigning latent class membership. Higher entropy values indicate greater precision of classification. Lastly, we provide the average posterior probability for the preferred class solution. Average posterior probability values > .80 indicate good statistical basis for assigning classes to their most-likely class when examining relationships between latent class membership and variables not in the latent class model [63]. Analyses utilize all available data (i.e., missing data were estimated utilizing maximum likelihood estimation procedures). However, all analyses were repeated utilizing casewise deletion and results were the same.

Results

Period prevalence rates of depressive and anxiety disorders at each of the time intervals are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Prevalence Rates of Depressive and Anxiety Disorders at Each Age Interval

| Depressive Disorders | Anxiety Disorders | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Interval | N | Unweighted % | Weighted % | n | Unweighted % | Weighted % |

| ≤ 14 | 164 | 9.9 | 6.6 | 134 | 8.1 | 5.5 |

| 15–16 | 227 | 13.9 | 9.2 | 81 | 4.9 | 3.5 |

| 17–18 | 160 | 11.9 | 8.3 | 77 | 5.7 | 4.4 |

| 19–20 | 125 | 13.0 | 10.8 | 56 | 5.8 | 4.9 |

| 21–22 | 173 | 19.4 | 17.2 | 58 | 6.5 | 5.5 |

| 23–24 | 160 | 18.0 | 15.2 | 70 | 7.9 | 6.9 |

| 25–26 | 108 | 12.9 | 11.4 | 65 | 7.8 | 7.2 |

| 27–28 | 136 | 17.5 | 15.0 | 66 | 8.5 | 7.9 |

| 29–30 | 123 | 16.1 | 13.5 | 60 | 7.9 | 6.9 |

Latent Class Growth Modeling of the Dual Trajectory Model

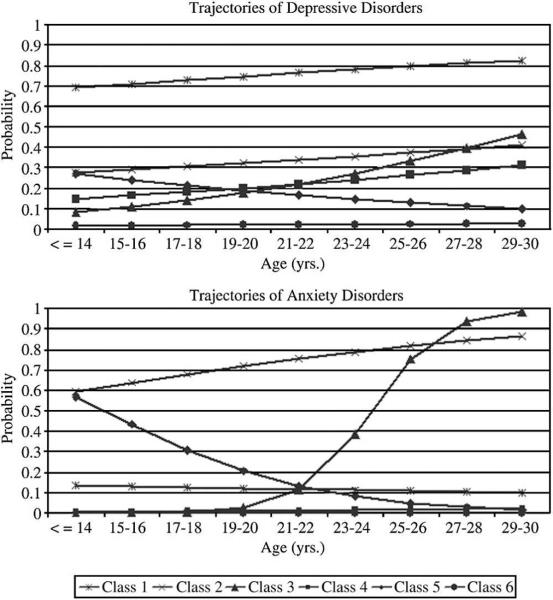

LCGA was performed estimating model fit for 2 through 10 classes that estimated the trajectory of both depressive and anxiety disorders. The best fitting model, as indicated by the BIC, was the 6-class model (Table 2).† The top panel of Figure 1 displays the trajectories of depressive disorders and the bottom panel of Figure 1 displays the trajectories of anxiety disorders according to class membership. The first class included individuals with persistent depression (Class 1; 1.3%). Individuals in this class had consistently high probabilities (i.e., all probabilities > .70) of having a depressive disorder at each time interval, while having consistently low probabilities (i.e., all probabilities approximately .15) of having an anxiety disorder. In this class, 100% of members had a lifetime depressive disorder diagnosis and 40% of members had a lifetime anxiety disorder diagnosis.

Table 2.

Fit Indices for Dual Trajectory Model Solutions

| Classes | AIC | BIC | Entropy |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 9012.098 | 9060.791 | .828 |

| 3 | 8708.124 | 8783.869 | .768 |

| 4 | 8559.691 | 8662.488 | .733 |

| 5a | 8443.005 | 8572.853 | .753 |

| 6a | 8381.070 | 8537.970 | .728 |

| 7a | 8364.654 | 8548.606 | .742 |

| 8a | 8344.484 | 8555.487 | .730 |

| 9a | 8327.887 | 8565.942 | .738 |

| 10a | 8317.993 | 8583.100 | .760 |

Note: AIC = Akaike Information Criteria; BIC = Bayesian Information Criteria.

Beginning with the 5 class solution, constraints on the threshold and slope parameters anxiety disorders in the class reflecting a consistently very low probability of having an anxiety disorder were necessary for appropriate model estimation. Lower BIC values indicate better fit. Higher entropy values indicate greater precision of class membership assignment.

Figure 1.

The top panel displays estimated probabilities of depressive disorder as a function of class membership. The bottom panel displays estimated probabilities of anxiety disorder as a function of class membership. Class 1 includes individuals with persistent depression (1.3%); Class 2 includes individuals with persistent anxiety (2.1%); Class 3 includes individuals with later onset of anxiety with increasing depression (3.7%); Class 4 includes individuals with increasing depression (22.8%); Class 5 includes individuals with anxiety with early recovery (5.0%); and Class 6 includes individuals without anxiety/depression (65.1%).

The second class included individuals with persistent anxiety (Class 2; 2.1%). Individuals in this class had consistently high probabilities (i.e., all probabilities > .55) of having an anxiety disorder at each time interval, while having modest probabilities (i.e., ranging from approximately .25 to .40) of having a depressive disorder. In this class, 100% of members had a lifetime anxiety disorder diagnosis, and 87.8% of members had a lifetime depressive disorder diagnosis.

The third class included individuals with a later onset of anxiety with increasing depression (Class 3; 3.7%). Individuals in this class had initially very low probabilities of anxiety disorder, however, between ages 21 and 26, the probability increased rapidly (i.e., from approximately .10 to .70), while the probability of a depressive disorder increased more gradually over each interval (i.e., from approximately .10 to .45). In this class, 100% of members had a lifetime anxiety disorder diagnosis, and 91.7% of members had a lifetime depressive disorder diagnosis.

The fourth class included individuals with increasing depression (Class 4; 22.8%). Individuals in this class had an initially low probability of a depressive disorder that increased modestly over time (i.e., from approximately .15 to .30). However, the probability of anxiety disorder was consistently very low (i.e., approximately .02). In this class, 98.6% of members had a lifetime depressive disorder diagnosis and 9.6% of members had a lifetime anxiety disorder diagnosis.

The fifth class included individuals with initially high, but decreasing anxiety (Class 5; 5.0%). Individuals in this class had an initially high probability of anxiety disorder (i.e., approximately .60) that decreased over time through adulthood (i.e., to approximately .05). The initial modest probability of depressive disorder (i.e., approximately .30) also decreased over time through adulthood (i.e., to approximately .10). In this class, 100% of members had a lifetime anxiety disorder diagnosis, and 67.9% of members had a lifetime depressive disorder diagnosis.

Finally, the sixth class included individuals with consistently very low probabilities of anxiety and depressive disorders (i.e., approximately .01) (Class 6; 65.1%). In this class, 11.8% of members had a lifetime depressive disorder diagnosis and no members had a lifetime anxiety disorder diagnosis.

Class Membership as a Function of Specific Diagnoses

Next, we assigned individuals to classes based on their most likely class membership. Posterior probability of class membership was high (.822), suggesting that assigning individuals to their respective classes was done with good precision [63]. We examined the percentage of individuals with a specific depressive or anxiety disorder in each class (i.e., percentages are across the rows). As few individuals met criteria for a number of specific disorders, no formal statistical testing was performed. The results of these exploratory analyses are displayed in Table 3. Numbers within the parenthesis are the percentage of individuals within a specific class who had a specific lifetime diagnosis. For example, of the 30 individuals with persistent depression (i.e., Class 1), 15 (50%) had a lifetime diagnosis of dysthymia. We (arbitrarily) focus on instances where the prevalence of specific disorders was at least 35%.

Table 3.

Frequencies and Percentages of Anxiety and Depressive Disorders Within Classes

| Overall Sample | Class 1 | Class 2 | Class 3 | Class 4 | Class 5 | Class 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%)a | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Any Depressive Disorder | 603 (36.5) | 30 (100) | 36 (87.8) | 33 (91.7) | 278 (98.6) | 93 (67.9) | 133 (11.8) |

| MDD | 591 (35.8) | 30 (100) | 35 (85.4) | 33 (91.7) | 267 (94.7) | 93 (67.9) | 133 (11.8) |

| Dysthymia | 64 (3.9) | 15 (50.0) | 7 (17.1) | 3 (8.3) | 28 (9.9) | 11 (8.0) | 0 (0.0) |

|

| |||||||

| Any Anxiety Disorder | 253 (15.3) | 12 (40.0) | 41 (100) | 36 (100) | 27 (9.6) | 137 (100) | 0 (0.0) |

| GAD | 16 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (5.6) | 13 (36.1) | 1 (.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Overanxious Disorder | 22 (1.3) | 2 (6.7) | 3 (7.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 17 (12.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| PTSD | 69 (4.2) | 3 (12.5) | 14 (38.9) | 9 (25.0) | 7 (3.2) | 36 (33.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Panic w/o Agor. | 40 (2.4) | 5 (16.7) | 8 (19.5) | 6 (16.7) | 10 (3.5) | 11 (8.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Panic w/ Agor. | 17 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (17.1) | 4 (11.1) | 4 (1.4) | 2 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Agoraphobia w/o Panic | 5 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.9) | 1 (2.8) | 1 (.4) | 1 (.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Social Phobia | 42 (2.5) | 1 (3.3) | 13 (31.7) | 7 (19.4) | 2 (.7) | 19 (13.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Simple Phobia | 57 (3.4) | 2 (6.7) | 19 (46.3) | 6 (16.7) | 1 (.4) | 29 (21.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| OCD | 15 (0.9) | 1 (3.3) | 4 (9.8) | 4 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Separation Anxiety | 65 (3.9) | 2 (6.7) | 11 (26.8) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (.7) | 50 (36.5) | 0 (0.0) |

|

| |||||||

| SUD | 453 (27.4) | 17 (56.7) | 20 (48.8) | 22 (61.1) | 138 (48.9) | 54 (39.4) | 202 (17.9) |

Note:

Unweighted sample prevalence.

Class sizes based on most likely class membership: Class 1: n = 30; Class 2: n = 41; Class 3: n = 36; Class 4: n = 282; Class 5: n = 137; Class 6: n = 1127. Class 1 is the persistent depression class; Class 2 is the persistent anxiety class; Class 3 is the later onset, with increasing depression class; Class 4 is the increasing depression class; Class 5 is the initially high, but decreasing anxiety class; and Class 6 is the consistently low depression and anxiety class. MDD = Major Depressive Disorder; GAD = Generalized Anxiety Disorder; PTSD = Post-traumatic Stress Disorder; Agor. = Agoraphobia; OCD = Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder; SUD = Substance Use Disorder.

All individuals within the persistent depression class had a lifetime diagnosis of MDD, half had lifetime diagnoses of dysthymic disorder, slightly more than half (56.7%) had a lifetime diagnosis of SUD, and less than half (40%) had any anxiety disorder. No specific form of anxiety disorder demonstrated appreciable aggregation within this class. All individuals in the persistent anxiety class had a lifetime anxiety disorder diagnosis, with particularly high rates of PTSD and simple phobia; most participants also had a lifetime depressive disorder, particularly MDD; and almost half had lifetime SUD. All individuals in the late onset anxiety disorder class had an anxiety disorder, particularly GAD; almost all (91.7%) had a lifetime depressive disorder, particularly MDD; and over half (61.1%) had lifetime SUD. Almost all (98.6%) of the individuals in the increasing depression class had a lifetime depressive disorder, particularly MDD; and almost half (48.9%) had lifetime SUD. All of the individuals in the initially high, but decreasing anxiety class had a lifetime anxiety disorder, particularly separation anxiety disorder; approximately two-thirds (67.9%) had a lifetime depressive disorder, particularly MDD; and a large minority (39.4%) had lifetime SUD. No appreciable rates of psychopathology were found within the class characterized by consistently low probabilities of depressive and anxiety disorders.

Prediction of Class Membership in the Dual Trajectory Model

The next set of analyses examined predictors of latent class membership within a LCGA framework. The model included gender; parental depressive, anxiety, and SUD; and history of childhood abuse, and adjusted for the proportion of parents who received a direct interview. All comparisons presented here are with respect to membership in Class 6, which had very low probabilities of depressive or anxiety disorders. Thus, the latent classes served as the dependent variable in a multinomial logistic regression model.

Membership in Class 1 (persistent depressive disorder) was predicted by parental depressive disorder and childhood abuse. Membership in Class 2 (persistent anxiety disorder) was predicted by parental anxiety disorder and childhood abuse. Membership in Class 3 (later onset of anxiety/increasing depression) was predicted by female sex and parental anxiety disorder. Membership in Class 4 (increasing depressive disorder) was predicted by female sex, parental depressive disorder, and childhood abuse. Membership in Class 5 (initially high, but decreasing anxiety disorder) was predicted by female sex, parental SUD, and childhood abuse.

Pairwise Contrasts

In addition to the multinomial logistic regression models presented, we also examined the multiple pairwise contrasts by altering the reference class. Of note, the OR between parental history of depressive disorder and membership in Class 1 (persistent depression) was greater than the association in all other classes. Additionally, the OR between parental history of depression and membership in Class 4 (increasing depression) was greater than that for parental history of depressive disorder and membership in Class 5 (initially high, but decreasing anxiety). Conversely, the OR between parental history of SUD and membership in Class 5 was higher than the association in Class 4. Lastly, the OR between history of abuse and membership in Class 2 (persistent anxiety) was greater than the association of abuse with all other classes except Class 1 (persistent depression). Contrasts that were not described did not significantly differ. Supplemental data are available from the corresponding author.

As the age at assessment could influence the nature of retrospective recall of psychopathology, we examined whether class membership was influenced by age at each assessment. No significant associations with age were observed (all ps > .10). ‡

Discussion

The goal of this study was to use a person-centered data analytic approach to examine the joint course of depressive and anxiety disorders. The first aim was to examine the conjoint trajectory of depressive and anxiety disorders and explore class membership as a function of specific diagnoses. The second aim was to explore the meaning and validity of the trajectory classes by examining their associations with selected internal and external correlates.

Conjoint Trajectory Classes

No previous study has examined the conjoint trajectory of depressive and anxiety disorders. Based on previous related literature [3,6,11,64], we expected to identify a class of individuals who had an initially high probability of anxiety disorder preceding an increasing probability of depressive disorder. We also expected to find a class of individuals with high probabilities of having depressive and anxiety disorders; depressive disorders, only, anxiety disorders, only; and neither depressive nor anxiety disorders [32]. The best fitting conjoint model identified six trajectory classes, which included a number of the hypothesized classes. Two classes primarily reflected different course variants of depressive disorders, one reflected anxiety disorders, two reflected different patterns of comorbidity, and one reflected no internalizing psychopathology.

Both depressive disorder classes reflected a relatively consistent probability of being depressed, however, the magnitude of the probability differed between classes. The first class had a high, persistent probability of depressive disorder and the second had a slowly increasing probability of depressive disorder. The first class may reflect an early-onset chronic form of depression (i.e., > 70% chance of being depressed at each time interval), whereas the second depression class may reflect an adult-onset, episodic form of depression (i.e., < 25% chance of being depressed at each time interval). The persistent depression class had a prevalence rate of 1.3% (n = 30), whereas the increasing depression class had a prevalence rate of 22.8% (n = 282). These prevalence rates roughly reflect the lifetime prevalence of chronic and non-chronic depression in the community [3]. Interestingly, early-onset chronic and adult-onset episodic forms of depression may be associated with important etiological and treatment differences [65]. Alternatively, these classes may reflect severity levels of depression.

Both of these classes had relatively low probabilities of anxiety disorders. Previous data suggests that the prevalence of depression without anxiety is greater than the prevalence of anxiety without depression [66,67]. The present data are consistent with this observation. The two classes with a relatively “pure” course of depressive disorders, persistent depression and increasing depression, included a much larger proportion of the sample (24.1%) than the one class with a relatively “pure” course of anxiety disorders, persistent anxiety (2.1%). Classes characterized by anxiety disorders tended to have a high degree of comorbid depressive symptomatology. Thus, “pure” depression trajectories appear to be more common than “pure” anxiety trajectories.

Only one previous study has attempted to identify distinct classes of developmental trajectories of depression. Stoolmiller, Kim, and Capaldi [68] identified four trajectory classes of men which differed mostly with respect to the initial severity of depressive symptoms. These classes were described as demonstrating chronically high; initially high, but decreasing; initially moderate, but decreasing; and stable low levels of depressive symptoms. We also found persistently high (Class 1) and slightly decreasing depressive disorder (Class 5) classes. However, we also identified two trajectory classes (Classes 3 and 4) that had modest increases in the probability of depressive disorder from adolescence through adulthood. These classes may have been obscured in Stoolmiller et al. since they followed subjects only through age 24 and focused exclusively on males. In our study, the classes with increasing probabilities of depressive disorder had higher proportions of females than males.

The data also suggested the presence of a persistent anxiety class. This class demonstrated the greatest and most consistent probability (> 55% chance of anxiety disorders at each time interval) of having an anxiety disorder. In addition to anxiety disorders, individuals in this class had a modestly elevated, relatively consistent (approximately 30%) chance of being depressed at each time interval.

Two additional anxiety disorder classes were identified, which appeared to differ in the age at which anxiety disorders were manifested. One class had an initially low probability of anxiety disorder, which remained stable until the ages of 22–24 when the probability of anxiety disorders increased sharply. The rate of depression also increased for individuals in this class, however, this rise was much more gradual. The last anxiety disorder class had a relatively high initial probability of anxiety disorder before adolescence, with a diminishing probability from adolescence through young adulthood. The early probability of depressive disorder in this class was moderate and also declined, although at a slower rate. These differential rates of decline may partially account for the observation that early anxiety disorders are associated with later depression [6,11,64]. However, it also suggests that the types of depressive disorders that follow early anxiety disorders may be less persistent than other forms of depression. Some investigators [69] have proposed that early treatment of anxiety disorders may be a method of preventing later depressive disorders. However, our data suggest that these resources may be better invested in prevention and early intervention efforts targeted at other, more persistent, forms of depression.

These patterns of classes provide grounds for speculating about the role of shared and unique factors that influence depression and anxiety. If only shared factors influenced trajectories of depressive and anxiety disorders, the probabilities of depressive and anxiety disorder should be similar and wax and wane together over time. However, we did not observe this. Rather, the probability of disorders and changes in probabilities over time were largely disparate. This suggests that unique influences play a significant role in the course of internalizing disorders. These unique influences might be reflected by the patterns of specific disorders and the risk factors for class membership.

Class Membership as a Function of Specific Diagnoses

In an attempt to better understand how these classes differ, we examined the prevalence rates of specific forms of psychopathology within each trajectory class. Within the persistently depressed class, half of the individuals had lifetime dysthymic disorder. Combined with the consistently high probability of major depression, individuals in this class appear to represent chronic or double depression (70).

Within the class characterized by an increasing probability of depressive disorders, almost all individuals had a lifetime diagnosis of MDD, while only a small minority had dysthymia. This pattern suggests that individuals in this class have brief, recurrent depressive episodes. Interestingly, comorbidity with anxiety disorders is infrequent in this group.

There was greater heterogeneity in the forms of psychopathology within the classes characterized by anxiety disorders. Within the class characterized by a persistent anxiety disorders, over one third of individuals had PTSD and simple phobia. These forms of anxiety disorder appear to have a more chronic course with lower probability of remission.

Within the class with an acute late onset of anxiety, GAD was most common. GAD typically has a later onset than other anxiety disorder diagnoses, which would be consistent with the trajectory observed of this class. Whether episodes of GAD persist into middle adulthood or remit cannot be determined from our data.

Individuals in the class characterized by an initial elevated, but decreasing probability of anxiety disorder had elevated rates of separation anxiety disorder. This is consistent with separation anxiety disorder being the only anxiety disorder classified by DSM as usually first occurring in childhood or adolescence. Although we note the forms of disorders that were most prevalent in the classes, there were also a number of other disorders present in each class. Future studies should examine the development and heterogeneity of psychopathology within the various classes.

In addition to examining specific mood and anxiety disorders, we also explored how SUDs were related to class membership. Of individuals with SUD, almost half were found in the class with a low probability of depressive and anxiety disorders. This suggests that the risk factors for a significant proportion of SUD cases are completely independent of those related to internalizing disorders. Almost one third of cases with SUD were found within the class of increasing depression. A sizeable minority of cases with SUD were found within the class with an initially high, but decreasing probability of anxiety disorder. This finding suggests that early anxiety may be an alternative developmental progression towards later externalizing problems [15,71]. Relatively few cases of SUD, however, were found within persistently depressed or anxious individuals. However, this conclusion needs to be interpreted with caution as the Classes 1 and 2 were the smallest classes identified.

Predictors of Class Membership

After identifying distinct trajectories of depressive and anxiety disorders, we examined several correlates of internalizing psychopathology, including gender, familial loading of psychopathology, and childhood abuse. Multivariate analyses demonstrated relatively specific patterns of associations between predictors and class membership. Parental history of depressive disorder was associated with membership in the persistent and increasing depressive class. The association between parental depressive disorder and membership in the persistent depressive disorder was much stronger than the associations between parental depressive disorder and membership in the increasing depression class. This pattern suggests that persistent depression may represent a more familial form of the disorder [65].

Parental history of anxiety disorder was associated with both the persistent anxiety class, and the later onset of anxiety disorders with increasing depression class. However, there was no statistical difference in familial loading between these classes. Future studies should examine if specific parental anxiety disorders demonstrate differences in associations with trajectory class membership in their offspring.

Parental SUD was associated with membership in the class with early high, but decreasing probability of anxiety disorder. As approximately 40% of members of this class had a lifetime SUD, this may suggest that early onset anxiety may be a precursor, or a pathway to, SUD for some individuals. However, as we did not examine temporal precedence of SUD, this claim warrants caution and further attention.

A history of childhood abuse was associated with membership in all classes, except for the later onset anxiety disorder with increasing depression class. This suggests that early adversity may have a greater impact on early-onset disorders. However, abuse was fairly non-specific with respect to depression versus anxiety and a more, versus less, persistent course. Additionally, the measure of abuse was potentially conflated with onset as the measure focused on experiences before age 18 and while residing at home with the family of origin.

Interestingly, the associations with gender were limited to the classes with non-persistent courses of depressive and anxiety disorders. This suggests that being female may be more highly associated with transient and episodic forms of internalizing psychopathology. Indeed, there is evidence that women are more reactive to stress than men during adulthood [72,73] and adolescence [74], which may contribute to a more episodic-intermittent course of psychopathology. Alternatively, the lack of sex differences for the small classes of persistent depression and anxiety may be due to low power. Future research should examine the association of gender specifically with persistent forms of depression and anxiety.

The study had a number of strengths, including the use of a prospective longitudinal design that included data from multiple developmental periods, a large community sample, and semi-structured diagnostic interviews to assess depressive and anxiety disorders. In addition, we used a statistical approach that allowed for the examination of categorical diagnoses, as opposed to symptom counts or severity scores. Although dimensional measures have many strengths, diagnoses have the virtue of focusing on clinically significant levels of psychopathology and being more easily related to both the psychopathology literature and clinical practice [75]. Finally, we also examined etiologically relevant predictors of the trajectory classes.

However, our findings should be interpreted with some caution. First, we examined summary categories of depressive and anxiety disorders. The anxiety disorder category included a variety of specific anxiety disorders and the depressive disorder category included both MDD and dysthymic disorder. Unfortunately, examining specific diagnoses, especially within the anxiety disorders, was not feasible as only small numbers of participants met criteria for most anxiety disorders. Thus, the findings may not apply equally well to every anxiety and depressive disorder category.

Second, the rates of anxiety disorders in the OADP are lower than some other large community samples, consisting mainly of adults [76]. However, other community based studies of adolescents and young adults have reported markedly similar rates of anxiety disorders [15,66]. Nonetheless, it is possible that samples with a higher prevalence or different distribution of specific anxiety disorders could yield different findings.

Third, not all participants completed all assessments. However, the unit of analysis was not assessment, but age intervals, and 99.1% of the sample contributed data for at least two age intervals. In addition, the complex sampling design was incorporated in the data analytic strategy; participants in these analyses were generally similar to non-participants; and when we conducted the analyses with and without missing data, results were very similar.

Fourth, parental psychopathology data was not available for all participants and not all parental psychopathology data were obtained via a direct interview. However, associations for parental psychopathology were adjusted for whether the parent was directly interviewed.

Fifth, some confidence intervals for associations between class membership and risk factors were large. This is due, in part, to the small number of cases in some classes. Thus, these findings require replication.

Sixth, some post-hoc constraints needed to be imposed on the LCGA models for appropriate and complete estimation. These constraints may have distorted some associations. However, we conducted the analyses without these constraints and did not find any substantive differences.

Seventh, lifetime diagnoses through age fourteen were aggregated into a single outcome. This decision obscured developmental course before this age point.

Finally, although we utilized a prospective, longitudinal design, there may have been retrospective recall biases in reporting onset and offset of psychopathology. Fortunately, no significant associations were found between age at each assessment and class membership.

In summary, the present study examined depressive and anxiety disorders simultaneously to identify latent trajectory classes. We identified classes of stable depression; stable anxiety; gradual increase in depressive disorders from adolescence through adulthood; rapid increase in anxiety disorders during emerging adulthood; and high initial, but decreasing probability of anxiety disorders. The present study suggests that greater specificity of the relations between risk factors and class membership may be evident when course trajectories are examined, rather than using a cross-sectional time point to reflect psychopathology as an outcome. Overall rates of depressive and anxiety disorders that are aggregated across developmental periods may obfuscate more specific relationships that are limited to particular trajectory classes. Further, we found gender differences in classes characterized by intermittent courses of internalizing disorders but no gender differences in classes characterized by persistent courses. Thus, considering the patterns of depressive and anxiety disorders over time appears to have important implications for the understanding of etiological pathways of internalizing psychopathology.

Table 4.

Predictors of Class Membership in the Dual Trajectory Model: Odds-ratios (95% Confidence Intervals)

| Predictor | Class 1 v. Class 6 | Class 2 v. Class 6 | Class 3 v. Class 6 | Class 4 v. Class 6 | Class 5 v. Class 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female Sex | 2.97 (.76–11.52) | 2.72 (.73–10.11) | 4.05 (1.31–12.52)* | 4.15 (2.26–7.63)** | 5.36 (2.45–11.72)** |

| Parental Depression | 47.56 (9.40–240.55)** | 3.34 (.63–17.69) | 2.53 (.48–13.33) | 4.66 (1.89–11.49)** | 1.30 (.40–4.21) |

| Parental Anx. | 1.84 (.25–13.63) | 9.49 (1.64–55.04)* | 15.41 (2.17–109.41)** | 2.17 (.53–8.85) | 3.68 (.90–15.14) |

| Parental SUD | 1.59 (.27–9.42) | .68 (.10–4.50) | .99 (.21–4.75) | 1.20 (.38–3.75) | 3.34 (1.31–8.53)** |

| Abuse | 1.08 (1.01–1.16)* | 1.13 (1.07–1.19)** | 1.04 (.98–1.11) | 1.07 (1.03–1.11)** | 1.06 (1.02–1.10)** |

Note:

p < .05

p < .01.

Total n for these analyses = 791. Simultaneous Multiple Multinomial Associations are adjusted for the percentage of parents who were directly interviewed and all of the variables in the column. Values in the table are odds-ratios (95% confidence intervals). Parental history of disorder is computed as the percentage of parents with each disorder. Analyses including family history variables are adjusted for the percentage of parents who received diagnostic interviews. To increase the consistency between the unconditional and conditional solutions, constraints were placed on the threshold and slope parameters for anxiety disorders in the class reflecting a consistently very low probability of having an anxiety disorder. Class 1 is the persistent depression class; Class 2 is the persistent anxiety class; Class 3 is the later onset, with increasing depression class; Class 4 is the increasing depression class; Class 5 is the initially high, but decreasing anxiety class; and Class 6 is the consistently low depression and anxiety class.

Acknowledgement

This work was partially supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grants RO1 MH66023 (Dr. Klein), RO1 MH40501, RO1 MH50522, and RO1 MH52858 (Dr. Lewinsohn). Portions of these data were presented at the Twentieth Annual Meeting of the Society for Research in Psychopathology, San Diego, CA, October, 2006.

Footnotes

Beginning with the 5 class solution, constraints were required for appropriate model estimation. In one class, threshold parameters for the anxiety disorder indicators were set at 15, which reflects an essentially 0 probability of anxiety disorder at each time, and the mean intercept and slope parameters for the growth of anxiety disorders were set at 0. This class reflected a consistently very low probability of having an anxiety disorder. No modifications were necessary for depressive disorder parameters. For the best-fitting six-class solution, an additional constraint was required for class 4. For this class, it was necessary to fix the anxiety disorder slope parameter at 0. Conclusions based on the models with and without the constraints are identical.

As there may be circuilarity and biases in examining the role of abuse in identifying class membership based on the presence of PTSD, we examined two additional analyses to probe this potential influence. First, we examined the associations between early childhood adversity and PTSD in the entire sample using in a naïve logistic regression model. This analysis found that the index of abuse that was used in the present study was associated with a lifetime diagnosis of PTSD (OR = 1.06, 95% CI = 1.04–1.09, p < .001). Thus, there is evidence that abuse and PTSD are associated; however, using this dimensional measure, this effect is quite modest. Second, we examined trajectory classes without including PTSD diagnoses as part of the broad anxiety disorder category. In those analyses, 39 (of 69) individuals with PTSD had additional anxiety disorder diagnoses, so only 30 subjects were coded as having no anxiety disorder. In the LCGA, we again found that the six-class solution best fit the data based on the BIC. Further, we found substantial convergence between the original analyses and the analyses conducted without PTSD with approximately 95% of cases being assigned to the comparable class. Results from the multinomial logistic regression analyses also corresponded closely to the results of the original analyses.

References

- 1.Brady EU, Kendall PC. Comorbidity of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;111:244–255. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.2.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mineka S, Watson D, Clark LA. Comorbidity of anxiety and unipolar mood disorders. Annual Review of Psychology. 1998;49:377–412. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, Rush AJ, Walters EE, Wang PS. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Study Replication (NCS-R) Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289:3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark LA. Depressive and anxiety disorders: Descriptive psychopathology and differential diagnosis. In: Kendall PC, Watson D, editors. Anxiety and depression: Distinctive and overlapping features. Academic Press; NY: 1989. pp. 83–129. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alloy LB, Kelly KA, Mineka S, Clements CM. Comorbidity of anxiety and depressive disorders: A helplessness-hopelessness perspective. In: Maser JD, Cloninger RC, editors. Comorbidity of Mood and Anxiety Disorders. American Psychological Association; Washington, D.C.: 1990. pp. 499–543. [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Graaf R, Bijl RV, Spijker J, Beekman ATF, Vollebergh WAM. Temporal sequencing of lifetime mood disorders in relation to comorbid anxiety and substance use disorders: Findings from the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study. Sociological Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2003;38:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00127-003-0597-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown TA, Campbell LA, Lehman CL, Grisham JR, Mancill RB. Current and lifetime comorbidity of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders in a large clinical sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:585–599. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.4.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kovacs M, Devlin B. Internalizing disorders in childhood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1998;39:47–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Markowitz JC, Moran ME, Kocsis JH, Frances AJ. Prevalence and comorbidity of dysthymic disorder among psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1992;24:63–71. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(92)90020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Avenevoli S, Stolar M, Li J, Dierker L, Merikangas KR. Comorbidity of depression in children and adolescents: Models and evidence from a prospective high-risk family study. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;49:1071–1081. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01142-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warner V, Weissman MM, Mufson L, Wickramaratne PJ. Grandparents, parents, and grandchildren at high risk for depression: A three-generation study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:289–296. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199903000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pine DS, Cohen P, Gurley D, Brook J, Ma Y. The risk for early-adulthood anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:56–64. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cole DA, Peeke LG, Martin JM, Truglio R, Seroczynski AD. A longitudinal look at the relation between depression and anxiety in children and adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:451–460. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.3.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wittchen HU, Beesdo K, Bittner A, Goodwin RD. Depressive episodes – evidence for a causal role of primary anxiety disorders? European Psychiatry. 2003;18:384–393. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A. Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burke JD, Loeber R, Lahey BB, Rathouz PJ. Developmental transitions among affective and behavioral disorders in adolescent boys. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46:1200–1210. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim-Cohen J, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Harrington H, Milne BJ, Poulton R. Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder: Developmental follow-back of a prospective-longitudinal cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:709–717. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Boden JM. Structure of internalising symptoms in early adulthood. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;189:540–546. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.022384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krueger RF, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Silva PA. The structure and stability of common mental disorders (DSM-III-R): A longitudinal-epidemiological study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:216–227. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olino TM, Klein DN, Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR. Longitudinal associations between depressive and anxiety disorders: A comparison of two trait models. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38:353–363. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garber J, Keiley MK, Martin NC. Developmental trajectories of adolescents' depressive symptoms: Predictors of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:79–95. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galambos NL, Leadbeater BJ, Barker ET. Gender differences and risk factors for depression in adolescence: A 4-year longitudinal study. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2004;28:16–25. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galambos NL, Barker ET, Krahn HJ. Depression, self-esteem, and anger in emerging adulthood: Seven-year trajectories. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:350–365. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim HK, Capaldi DM, Stoolmiller M. Depressive symptoms across adolescence and young adulthood in men: Predictions from parental and contextual risk factors. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15:469–495. doi: 10.1017/s0954579403000257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wiesner M. A Longitudinal latent variable analysis of reciprocal relations between depressive symptoms and delinquency during adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:633–645. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wiesner M, Kim HM. Co-occurring delinquency and depressive symptoms of adolescent boys and girls: A dual trajectory modeling approach. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:1220–1225. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.6.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Measelle JR, Stice E, Hogansen JM. Developmental trajectories of co-occurring depressive, eating, antisocial, and substance abuse problems in female adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:524–538. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.3.524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muthén B, Muthén LK. Integrating person-centered and variable centered analyses: Growth mixture modeling with latent trajectory classes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:882–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagin DS. Analyzing developmental trajectories: A semi-parametric, group-based approach. Psychological Methods. 1999;4:139–177. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.6.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewinsohn PM, Hops H, Roberts RE, Seeley JR, et al. Adolescent psychopathology: I3Prevalence and incidence of depression and other DSM-III--R disorders in high school students. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1993;102:133–144. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krueger RF, Finger MS. Using item response theory to understand comorbidity among anxiety and unipolar mood disorders. Psychological Assessment. 2001;13:140–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clark LA, Watson D. Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: Psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:316–336. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.3.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merikangas KR, Mehta RL, Molnar BE, Walters EE, Swendsen JD, Aguilar-Gaziola S, Bijl R, Caraveo-Anduaga JJ, Dewitt DJ, Kolody B, Vega WA, Wittchen HU, Kessler RC. Comorbidity of substance use disorders with mood and anxiety disorders: Results of the international consortium in psychiatric epidemiology. Addictive Behaviors. 1998;23:893–907. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leventhal AM, Witt CF, Zimmerman M. Associations between depression subtypes and substance use disorders. Psychiatry Research. 2008;161:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leventhal AM, Lewinsohn PM, Pettit JW. Prospective relations between melancholia and substance use disorders. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2008;34:259–267. doi: 10.1080/00952990802013367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goodman SH, Gotlib IH, editors. Children of depressed parents: Alternative pathways to risk for psychopathology. American Psychological Association Press; Washington, D.C.: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beidel DC, Turner SM. At risk for anxiety: I. Psychopathology in the offspring of anxious parents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:918–924. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Biederman J, Faraone SV, Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Friedman D, Robin JA, Rosenbaum JF. Patterns of psychopathology and dysfunction in high-risk children of parents with panic disorder and major depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:49–57. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson JG, Cohen P, Kasen S, Brook JS. A multiwave multi-informant study of the specificity of the association between parental and offspring psychiatric disorders. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2006;47:169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clark DB, Moss HB, Kirisci L, Mezzich AC, Miles R, Ott P. Psychopathology in preadolescent sons of fathers with substance use disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:495–502. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199704000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Klein DN, Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR, Olino TM. Psychopathology in the adolescent and young adult offspring of a community sample of mothers and fathers with major depression. Psychological Medicine. 2005;35:353–365. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704003587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kessler RC, Davis CG, Kendler KS. Childhood adversity and adult psychiatric disorder in the U.S. National Comorbidity Survey. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27:1101–1119. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hayden EP, Klein DN. Outcome of Dysthymic Disorder at 5-Year Follow-Up: The Effect of Familial Psychopathology, Early Adversity, Personality, Comorbidity, and Chronic Stress. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:1864–1870. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Orvaschel H, Puig-Antich J, Chambers WJ, Tabrizi MA, Johnson R. Retrospective assessment of prepubertal major depression with the Kiddie-SADS-E. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1982;21:392–397. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)60944-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3rd ed. Author; Washington, DC: 1987. rev. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Keller MB, Lavori PW, Friedman B, Nielsen E, Endicott J, McDonaldscott P, et al. The Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation - a Comprehensive Method for Assessing Outcome in Prospective Longitudinal-Studies. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1987;44:540–548. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800180050009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Author; Washington, DC: 1994. rev. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krueger RF, Markon KE, Patrick CJ, Iacono WG. Externalizing psychopathology in adulthood: A dimensional-spectrum conceptualization and its implications for DSM-V. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:537–550. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Collins RL, Ellickson PL, Bell RM. Simultaneous polydrug use among teens: Prevalence and predictors. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1998;10:233–253. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(99)00007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Midanik LT, Tam TW, Weisner C. Concurrent and simultaneous drug and alcohol use: Results of the 2000 National Alcohol Survey. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;90:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders, non-patient edition (SCID-NP, Version 2.0) Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mannuzza S, Fyer AJ. Family informant schedule and criteria (FISC), revision. Anxiety Disorders Clinic, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 1990. 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Leckman JF, Sholomskas D, Thompson D, Belanger A, Weissman MM. Best estimate of lifetime psychiatric diagnosis: A methodological study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1982;39:879–883. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290080001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Milne BJ, Moffitt TE, Crump R, Poulton R, Rutter M, Sears MR, et al. How should we construct psychiatric family history scores? A comparison of alternative approaches from the Dunedin Family Health History Study. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38:1793–1802. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rohde P, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR. Comparability of telephone and face-to-face interviews in assessing axis I and II disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154:1593–1598. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.11.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sobin C, Weissman MM, Goldstein RB, Adams P, Wickramaratne P, Warner V, et al. Diagnostic Interviewing for Family Studies - Comparing Telephone and Face-to-Face Methods for the Diagnosis of Lifetime Psychiatric-Disorders. Psychiatric Genetics. 1993;3:227–233. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Berger A, Knutson J, Mehn J, Perkins K. The self report of punitive childhood experiences of young adults and adolescents. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1988;12:251–262. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(88)90033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bernstein D, Fink L, Handelsman L, Foote J, Lovejoy M, Wenzel K, Sapareto E, Ruggiero J. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151:1132–1136. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.8.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide. Fourth Edition Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 1998–2007. [Google Scholar]

- 61.D'Unger AV, Land KC, McCall PL, Nagin DS. How many latent classes of delinquent/criminal careers? Results from mixed poisson regression analyses. American Journal of Sociology. 1999;103:1593–1630. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthén BO. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2007;14:535–569. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Clark S, Muthén B. Relating latent class analysis results to variables not included in the analysis. Submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kovacs M, Gatsonis C, Paulauskas SL, Richards C. Depressive disorders in childhood. IV. A longitudinal study of comorbidity with and risk for anxiety disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1989;46:776–782. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810090018003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Klein DN. Dysthymia and chronic depression. In: Craighead WE, Miklowitz DJ, Craighead LW, editors. Psychopathology: History, theory, and diagnosis. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, N.J.: 2008. pp. 329–365. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Merikangas KR, Zhang HP, Avenevoli S, Acharyya S, Neuenschwander M, Angst J. Longitudinal trajectories of depression and anxiety in a prospective community study – The Zurich cohort study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:993–1000. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Preisig M, Merikangas KR, Angst J. Clinical significance and comorbidity of subthreshold depression and anxiety in the community. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2001;104:96–103. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stoolmiller M, Kim HK, Capaldi DM. The course of depressive symptoms in men from early adolescence to young adulthood: Identifying latent trajectories and early predictors. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:331–345. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.3.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kessler RC, Price RH. Primary prevention of secondary disorders: A proposal and agenda. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1993;21:607–633. doi: 10.1007/BF00942174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McCullough JP, Jr., Klein DN, Borian FE, Howland RH, Riso LP, Keller MB, et al. Group Comparisons of DSM-IV Subtypes of Chronic Depression: Validity of the Distinctions, Part 2. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:614–622. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hahesy AL, Wilens TE, Biederman J, van Patten SL, Spencer T. Temporal association between childhood psychopathology and substance use disorders: Findings from a sample of adults with opioid or alcohol dependency. Psychiatry Research. 2002;109:245–253. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(02)00015-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rudolph KD, Hammen C. Age and gender as determinants of stress exposure, generation, and reactions in youngsters: A transactional perspective. Child Development. 1999;70:660–677. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kendler KS, Kuhn J, Prescott CA. The relationship of neuroticism, sex, and stressful life events in the prediction of episodes of major depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:631–636. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hankin B, Mermelstein R, Roesch L. Sex differences in adolescent depression: Stress exposure and reactivity models. Child Development. 2007;78:279–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kessler RC. The categorical versus dimensional assessment controversy in the sociology of mental illness. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2002;43:171–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walter EE. Lifetime prevalence and age of onset distribution of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]