Abstract

Objectives

Direct and mediated associations between subjective social status (SSS), a subjective measure of socioeconomic status, and smoking abstinence were examined during the period of acute withdrawal among a diverse sample of 421 smokers (33% Caucasian, 34% African-American, 33% Latino) undergoing a quit attempt.

Methods

Logistic regressions examined relations between SSS and abstinence, controlling for sociodemographic variables. Depression, stress, positive affect, and negative affect on the quit day were examined as potential affective mediators of the SSS-abstinence association, with and without adjusting for pre-quit mediator scores.

Results

SSS predicted abstinence through 2 weeks post-quit. Abstinence rates were approximately 2.5 times higher in the highest versus the lowest SSS quartile. Depression and positive affect mediated the SSS-abstinence relationships, but only depression maintained significance when adjusting for the baseline mediator score.

Conclusions

Among a diverse sample of quitting smokers, low SSS predicted relapse during acute withdrawal after controlling for numerous covariates, an effect partially accounted for by quit day affective symptomatology. Smokers endorsing lower SSS face significant hurdles in achieving cessation, highlighting the need for targeted interventions encompassing attention to quit day mood reactivity.

Tobacco use is the leading cause of preventable death and disability among adults in the United States (1), and although smoking prevalence has decreased in recent decades, it is becoming increasingly concentrated among individuals with the lowest levels of income, education, and occupational status (2–5). In fact, smoking plays a critical role in health disparities, accounting for a large proportion of the differences in disease incidence and mortality attributable to socioeconomic status (SES; 6–8). Similar to smoking prevalence, there is also a SES gradient in smoking cessation whereby persons with low SES are less successful at quitting (9–11). Although previous research has linked traditional indicators of SES (i.e., income, education, and occupation) with smoking cessation, no studies have examined the association between subjective perceptions of SES (i.e., subjective social status) and cessation, or the mechanisms that might account for a relationship.

Subjective social status (SSS) reflects an individual’s perception of her/his relative position in the social hierarchy (12), with known determinants including a myriad of SES indicators, as well as estimations of financial satisfaction, perceived future security (13), social trust, and perceived opportunities (14). Although SSS is highly correlated with traditional indicators of SES, low SSS predicts poor mental and physical health [e.g., (13, 15–20)] and undesirable health behaviors [e.g., lower physical activity (21)] over and above traditional SES indicators (14, 21–23). Thus, SSS may offer enhanced prediction of health outcomes and health behaviors over SES because it captures the components of social standing in a more comprehensive and meaningful way (24).

Various factors accounting for the association of low SSS and poor health have been examined, including depression (24), stress (21, 25), anxiety, pessimism (21), and negative affect (19). Although little is known about how SSS affects smoking cessation, previous research suggests that similar mechanisms may be involved. For example, among young pregnant women who quit smoking during pregnancy, low SSS was uniquely associated with a constellation of characteristics indicative of increased vulnerability to postpartum smoking, including less positive affect and more negative affect (23). Moreover, numerous studies have linked negative affect or affective changes, especially during the initial withdrawal period, to relapse during a quit attempt (26–30). As withdrawal effects emerge very soon after quitting (27, 28, 31) and generally peak during the initial two weeks following the quit attempt (32), affective mediators of an SSS-abstinence relationship might be ideally examined during the period of acute withdrawal from smoking.

To our knowledge, no previous research has examined the association between SSS and smoking abstinence during the period of acute withdrawal, or the mechanisms that might account for an association. The purpose of this study was to redress this gap by examining these relationships among racially/ethnically diverse adult smokers undergoing a smoking quit attempt. Potential mediators of interest were depression, stress, and positive and negative affect. Increasing understanding about these associations can inform treatment interventions designed to address tobacco use among low SSS smokers and potentially reduce tobacco-related health disparities.

Methods

Participants

Data for the current study were collected as part of a longitudinal cohort study designed to examine pathways linking social determinants (e.g., race/ethnicity) to smoking cessation (33). The enrollment period for this study was from April 2005 – April 2007. Participants were recruited from within the Houston metropolitan area via print and radio advertisements soliciting adult volunteers for a smoking cessation study. Interested smokers called the study recruitment line for more information. Participants (N = 424) were 21 years of age, daily smokers (≥5 cigarettes per day for the last year), motivated to quit in ≤30 days, and had ≥ 6th grade proficiency in English. Three participants did not provide SSS ratings and were excluded from this study.

Procedures

Participants were initially screened via telephone and later in person to determine eligibility. Written informed consent was obtained at the completion of the in-person screening/orientation and prior to substantive data collection. Participant recruitment and flow through the study are detailed elsewhere (33, 34).

Participants received standard smoking cessation treatment including six weeks of nicotine patch therapy, six brief cessation counseling sessions based on the Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence Clinical Practice Guideline (35), and self-help materials. Data for the current study were collected at week -1 (baseline), week 0 (quit day), and weeks 1 and 2 post-quit. Participants received $30 gift cards for their time and effort at each data collection visit.

Measures

All measures in this study were administered and completed via computer.

Demographics, Tobacco-Related Variables, and Subjective Social Status

Demographic variables (age, gender, race/ethnicity, and partner status), SES indicators (income, education, and employment status), and SSS were collected at baseline. Race/ethnicity was Caucasian, African-American, or Latino. Partner status was “current spouse or partner” or “no current spouse or partner.” Annual household income was <$10,000/year, $10,000 – $29,999/year, $30,000 – $49,999/year, or ≥$50,000/year. Educational levels were <high school/GED, completed high school/GED, some post-high school education, or college degree/s. Employment status was employed (full- or part-time) or not employed.

Tobacco-related variables included self-reported average number of daily cigarettes smoked pre-quit, years smoked, and time after awakening until the first cigarette of the day.

SSS was measured with the MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status, developed by and available from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Research Network on Socioeconomic Status and Health (12). The SES ladder version of the scale was used, which asks participants to select a rung on a 10-rung ladder that represents where they believe they stand in society relative to others, with higher rungs representing higher social status (i.e., more money, more education, and better jobs).

Potential Affective Mediators

Data for the potential affective mediators were collected on each participant’s quit day (week 0). Baseline measurements (week-1) were also included as covariates in some mediator analyses (see Data Analysis). The focus on quit day measurements was based on associations between quit day affective symptoms and relapse in prior research (28, 36, 37).

Depressive symptoms

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale [CES-D (38)] was developed to assess depressive symptoms in community, non-clinical populations. The CES-D has adequate reliability in racially/ethnically diverse populations [Cronbach’s coefficient of .87 (39)] and the CES-D has been found to predict smoking relapse (40). Higher scores are associated with greater depressive symptoms.

Stress

The short form of the Perceived Stress Scale [PSS-4 (41)] is a 4-item measure designed to assess the degree to which respondents have experienced stress in the last week. The PSS-4 has adequate reliability [Cronbach’s coefficient of .72 (42)] and higher PSS-4 scores are predictive of relapse (43, 44).

Positive and Negative Affect

The Positive and Negative Affect Scale [PANAS (45)] is designed to measure affect over the previous week and is comprised of two mood scales: Positive Affect (PA) and Negative Affect (NA). The PANAS has adequate reliability [Cronbach’s coefficient of .88 for PA and .85 for NA (45)], and NA has been among the best predictors of relapse in previous studies (44). Higher scores on the mood scales are indicative of greater positive or negative affect, respectively.

Smoking Abstinence

Continuous abstinence from smoking was defined as a self-report of no cigarettes smoked since the quit date (not even a puff), expired carbon monoxide levels of ≤10 ppm, and salivary cotinine levels of <20ng/ml. Smoking status was assessed at weeks 1 and 2 post-quit.

Data Analysis

As no show rates were relatively low for the post-quit week 1 and 2 assessments (16–19%), we used a completers-only approach to analysis. Differences between attendees and no shows on demographics and tobacco-related variables were assessed using t-tests for analyses involving continuous variables and chi-square tests for analyses involving categorical variables. Associations of demographics, SES indicators, and tobacco-related variables with SSS were explored using Pearson correlation coefficients for continuous variables and analyses of variance or t-tests for binary or categorical variables.

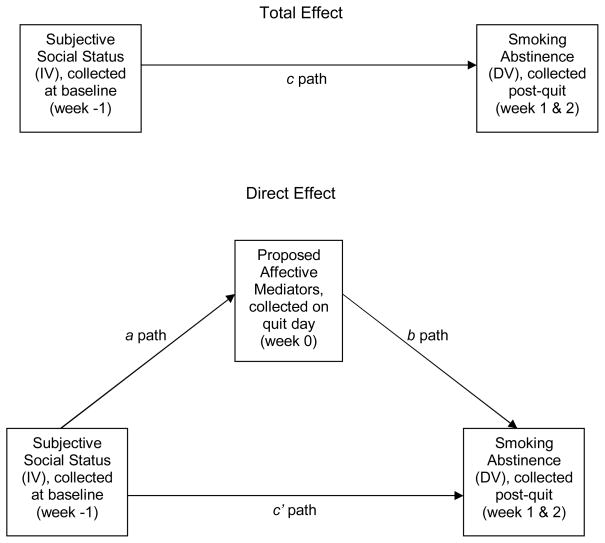

The primary aim of this study was to examine the associations between SSS and abstinence, and potential affective mediators (depression, stress, and positive and negative affect) of those associations, during the period of acute withdrawal (post-quit weeks 1 and 2) (see Figure 1 for the conceptual model). Mediation approaches to data analysis are ideal for evaluating the mechanisms through which an independent variable affects a dependent variable, thereby contributing to the explanation of why such an association exists. Because of the assumption of causality in a mediation model, variables of interest are commonly measured at different points in time (46). There are a number of methods available to evaluate mediation models in behavioral research (47). In the current study, we used the conventional causal-step approach followed by formal tests of the mediation effect using a bootstrapping procedure.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized conceptual model of the direct effect of SSS on abstinence and the indirect effect of SSS on abstinence through proposed mediators.

In line with the causal-step approach to mediation (46, 48), the associations between SSS and the mediators (a paths, assessed with linear regressions in the current study), the mediators and smoking abstinence adjusted for SSS (b paths, assessed with logistic regressions), and SSS and smoking abstinence (c path, assessed with logistic regression) should be statistically significant (Figure 1). Although the causal-step approach advocates that mediation is evinced by the elimination or reduction of the association of SSS with smoking abstinence (c′ path) when mediators are added to the model (i.e., c − c′), this approach is not applicable to analyses involving binary outcomes (49, 50). Instead, the proportion of the mediated effect can be estimated with methods advanced by MacKinnon and colleagues, such as [ab/(c′+ab)] (50).

Emerging research indicates that the mediation effect should be formally tested (47). In accordance with these recommendations, simple mediation models were formed and tested for each potential mediator variable, using a nonparametric, bias-corrected bootstrapping procedure to test the indirect effect, which is defined as the product of the coefficients of SSS in path a and the mediator in path b. The bootstrapping procedure generates an empirical approximation of the sampling distribution of the product of the estimated coefficients in the indirect paths with the use of thousands of, and in our analyses specifically, 5,000 resamples from the dataset. This approach makes no assumptions about the shape of the distributions or the product. This is important because distribution assumptions of normality for the products are commonly violated, and small samples present further threats to the normality assumption for any path in mediation models (47). Thus, bootstrapping is a preferred approach due to increased power over other methods (e.g., causal-step, plain product-of-coefficients) and better control over the Type I error rates (47).

Analyses were conducted in SPSS using an INDIRECT macro for binary outcomes (49). Mediators were first assessed in models controlling for demographics and SES indicators, and then in models that also controlled for the baseline score on each respective affective measure (e.g., examining the role of quit day depression after controlling for baseline depression). Finally, significant mediators from the simple models were tested simultaneously in multiple mediator models using the same SPSS INDIRECT macro (49).

Results

The sample was 33% Caucasian (n = 137), 34% African-American (n = 144), and 33% Latino (n = 140). Participants (N = 421, 46% male) were 41.2 years of age on average (SD = 11.2), and 34% reported having a partner. It was a relatively low SES sample, with 47% of respondents reporting less than $30,000 in annual household income, 14% lacking a high school diploma or equivalency, and 42% reporting current unemployment. At baseline, participants smoked an average of 21.1 (SD = 10.3) cigarettes per day for an average of 21.6 years (SD = 11.1), with 50% smoking their first cigarette within 5 minutes of waking.

Of the total sample, 341 (81%) attended the post-quit week 1 assessment. Attendees were older than no shows (p = .01). Of the total sample, 352 (84%) attended the post-quit week 2 assessment. Attendees were older (p < .001), smoked more pre-quit cigarettes per day (p < .02), were more likely to have a partner (p < .04), and less likely to be Latino (p < .02) than no shows.

Relationships between SSS, covariates, and tobacco-related variables were explored. Higher SSS was associated with being male (p < .02), employed (p < .001), and having higher income and educational achievement (ps < .001).

Each path of the mediation model (Figure 1) was assessed, beginning with linear regressions, adjusted for demographics and SES indicators, testing the association of SSS with proposed mediators (a paths). Higher SSS at baseline was associated with less depression, less stress, more positive affect, and less negative affect on the quit day (ps < .05; Table 1). However, after controlling for the baseline score of each respective mediator, SSS was only associated with depression (p < .02; Table 1).

Table 1.

Relationships between Subjective Social Status and Proposed Quit Day Mediators.

| Independent Variable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective Social Status | ||||

| B | SE | t | p | |

| Proposed Mediator Variables (a paths with demographic and socioeconomic status covariates) | ||||

| Depression | −0.97 | 0.36 | −2.71 | .007* |

| Stress | −0.07 | 0.03 | −2.41 | .017* |

| Positive Affect | 1.32 | 0.30 | 4.39 | <.001** |

| Negative Affect | −1.80 | 0.25 | −0.71 | ns |

| Proposed Mediator Variables (a paths with all covariates, including baseline affective score) | ||||

| Depression | −0.62 | 0.26 | −2.35 | .019* |

| Stress | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.43 | ns |

| Positive Affect | 0.18 | 0.24 | 0.73 | ns |

| Negative Affect | −0.11 | 0.20 | −0.58 | ns |

Note: p-values were based on linear regressions. Unstandardized coefficients are for the independent variable of Subjective Social Status. Depression = Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; Stress = Perceived Stress Scale; Positive Affect = Positive and Negative Affect Scale, Positive Affect subscale; and Negative Affect = Positive and Negative Affect Scale, Negative Affect subscale. Covariates include: age, gender, race/ethnicity, partner status, income, education, employment status and baseline scores for depression, stress, positive affect, or negative affect, respectively. “a path” refers to the path between the independent variable and mediators in mediation models.

Denotes significance at the p ≤ 0.001 level.

Denotes significance at the p ≤ 0.05 level.

Next, logistic regression analyses, adjusted for SSS, demographics, and SES indicators, were used to evaluate the association between proposed mediators and smoking abstinence at post-quit weeks 1 and 2 (b paths). Depression, stress, and positive affect on the quit day were associated with smoking status at post-quit week 1 (ps < .03; Table 2), and depression and positive affect on the quit day were associated with smoking status at post-quit week 2 (ps < .02; Table 2). Participants with less stress were more likely to be abstinent at post-quit week 1, and participants with less depression and more positive affect were more likely to be abstinent at both post-quit time points. The same pattern of associations remained present even after accounting for baseline scores on mediator variables (ps ≤ .02; Table 2).

Table 2.

Relationships between Proposed Quit Day Mediators, Subjective Social Status, and Abstinence at Post-Quit Weeks 1 and 2.

| Dependent Variables | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-Quit Week 1 Abstinence | Post-Quit Week 2 Abstinence | |||||||

| B | SE | Wald | p | B | SE | Wald | p | |

| Proposed Mediator Variables (b paths with demographic and socioeconomic status covariates) | ||||||||

| Depression | −0.05 | 0.01 | 9.67 | .002* | −0.04 | 0.02 | 6.51 | .011* |

| Stress | −0.40 | 0.17 | 5.16 | .023* | −0.36 | 0.19 | 3.69 | ns |

| Positive Affect | 0.05 | 0.02 | 8.64 | .003* | 0.05 | 0.02 | 7.24 | .007* |

| Negative Affect | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.98 | ns | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.42 | ns |

| Proposed Mediator Variables (b paths with all covariates, including baseline affective score) | ||||||||

| Depression | −0.09 | 0.02 | 16.74 | <.0001** | −0.07 | 0.02 | 9.47 | .002* |

| Stress | −0.57 | 0.24 | 5.91 | .015* | −0.46 | 0.24 | 3.61 | ns |

| Positive Affect | 0.11 | 0.03 | 17.73 | <.0001** | 0.09 | 0.03 | 11.58 | .001** |

| Negative Affect | −0.04 | 0.03 | 3.04 | ns | −0.03 | 0.03 | 1.29 | ns |

| Independent Variable (c path with demographic and socioeconomic status covariates) | ||||||||

| Subjective Social Status | 0.21 | 0.09 | 5.92 | .015* | 0.19 | 0.09 | 4.42 | .036* |

| Independent Variable (c path with all covariates, including baseline affective score) | ||||||||

| Subjective Social Status (+ depression) | 0.22 | 0.09 | 6.55 | .010* | 0.21 | 0.09 | 5.04 | .025* |

| Subjective Social Status (+ stress) | 0.22 | 0.09 | 6.15 | .013* | 0.21 | 0.09 | 4.84 | .028* |

| Subjective Social Status (+ pos. affect) | 0.24 | 0.09 | 7.12 | .008* | 0.22 | 0.10 | 5.46 | .019* |

| Subjective Social Status (+ neg. affect) | 0.22 | 0.09 | 6.52 | .011* | 0.21 | 0.09 | 5.08 | .024* |

Note: p-values are based on logistic regressions. Depression = Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; Stress = Perceived Stress Scale; Positive Affect = Positive and Negative Affect Scale, Positive Affect subscale; and Negative Affect = Positive and Negative Affect Scale, Negative Affect subscale. Covariates for paths include: age, gender, race/ethnicity, partner status, income, education, employment status, and baseline scores for depression, stress, positive affect, or negative affect, respectively. “b path” refers to the widely recognized path between the mediator and the dependent variable in mediation models. “c path” refers to the path between the independent and the dependent variable (i.e., the “total effect”).

Denotes significance at the p ≤ 0.001 level.

Denotes significance at the p ≤ 0.05 level.

Logistic regressions, controlling for demographics and SES indicators, were used to examine the total effect of SSS on abstinence (c path). SSS assessed at baseline predicted smoking status at post-quit week 1 [p < .02; OR = 1.23 (1.04–1.45)] and week 2 [p < .04; OR = 1.21 (1.01 – 1.45); Table 2]. Higher SSS was associated with greater abstinence at both time points. Adjusting further for tobacco-related variables (pre-quit cigarettes per day, years smoked, and time to first cigarette; results not shown) or baseline affective scores (Table 2) did not alter the pattern of results. When SSS scores were grouped into quartiles, abstinence rates were 2.6-fold higher at Week 1 and 2.4-fold higher at Week 2 when comparing the highest to lowest SSS quartiles.

Following the establishment of significant total effects of SSS on abstinence, indirect effects for potential affective mediators were assessed with a bootstrapping approach in simple mediation models. In analyses adjusted for demographics and SES variables, positive affect and depression mediated the effect of SSS on smoking cessation at post-quit weeks 1 and 2 (ps ≤ .05; Table 3). Results were consistent with the interpretation that higher SSS led to greater positive affect and less depression, which led to higher abstinence rates. In analyses that further adjusted for baseline scores on the respective affective variables, depression remained a significant mediator of the effect of SSS on smoking cessation (Table 3). The proportion of the total effect that was mediated by depression in this analysis was estimated at 22.4% using the formula: ab/(c′+ab) (50). However, because of stability concerns in studies with samples sizes < 500 (50), this estimate should be interpreted with caution.

Table 3.

Significance Testing of the Mediated Effect of Subjective Social Status on Abstinence During Acute Withdrawal.

| Analyses controlling for demographics and socioeconomic status indicators | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | Week 2 | |||||||||||

| Estimate of indirect effect | BCa 95% CI | Estimate of indirect effect | BCa 95% CI | |||||||||

| Proposed Mediator | 1 | 2 | SE | Lower | Upper | p | 1 | 2 | SE | Lower | Upper | p |

| Depression | 0.046 | 0.049 | 0.029 | .002 | .118 | ≤ .05 | 0.042 | 0.045 | 0.029 | .003 | .117 | ≤ .05 |

| Stress | 0.022 | 0.024 | 0.019 | −0.002 | 0.074 | ns | 0.021 | 0.023 | 0.019 | −0.002 | 0.075 | ns |

| Positive Affect | 0.068 | 0.072 | 0.032 | .019 | .143 | ≤ .05 | 0.061 | 0.067 | 0.031 | .011 | .127 | ≤ .05 |

| Negative Affect | −0.001 | −0.002 | 0.009 | −0.028 | 0.012 | ns | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.008 | −0.009 | 0.028 | ns |

| Analyses controlling for demographics, socioeconomic status indicators, and baseline affective scores | ||||||||||||

| Week 1 | Week 2 | |||||||||||

| Estimate of indirect effect | BCa 95% CI | Estimate of indirect effect | BCa 95% CI | |||||||||

| Proposed Mediator | 1 | 2 | SE | Lower | Upper | p | 1 | 2 | SE | Lower | Upper | p |

| Depression | 0.059 | 0.064 | 0.036 | .002 | .142 | ≤ .05 | 0.048 | 0.053 | 0.032 | .004 | .127 | ≤ .05 |

| Stress | −0.002 | −0.002 | 0.016 | −0.036 | 0.031 | ns | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.014 | −0.02 | 0.04 | ns |

| Positive Affect | 0.033 | 0.034 | 0.035 | −0.023 | 0.118 | ns | 0.023 | 0.024 | 0.029 | −0.027 | 0.095 | ns |

| Negative Affect | −0.004 | −0.005 | 0.013 | −0.041 | 0.017 | ns | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.011 | −0.013 | 0.037 | ns |

Note: Results were calculated using the SPSS INDIRECT macro syntax for estimating models with continuous or binary outcomes and continuous mediators. (49) Binary outcomes are detected automatically and estimated with logistic regression, ordinary least squares regression is used for continuous outcomes. 1 = The indirect effect calculated in the original sample. 2 = The mean of the indirect effect estimates calculated across 5000 bootstrap samples. SE = The standard deviation of the 5000 bootstrap estimates of the indirect effect. BCa 95% CI= Bias corrected and accelerated 95% confidence interval. Depression = Center of Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; Stress = Perceived Stress Scale; Positive Affect = Positive and Negative Affect Scale, Positive Affect subscale; and Negative Affect = Positive and Negative Affect Scale, Negative Affect subscale.

Finally, indirect effects for depression and positive affect on the quit day were assessed in multiple mediator models adjusted for demographics and SES indicators. At both weeks 1 and 2 post-quit, total mediation effects were significant (a1b1+a2b2 = .07, ps ≤ .05). However, specific indirect effects for depression in the presence of positive affect (and vice versa) were not significant due to the high intercorrelation between these variables (r = −.61; p < .001). Thus, results supported the use of simple mediator models to describe the mediation effects for these data.

Discussion

SSS predicted smoking abstinence during the period of acute withdrawal among a diverse sample of adult smokers undergoing a smoking quit attempt. The magnitude of this relationship can be illustrated by comparing abstinence rates in the lowest and highest SSS quartiles. At one week post-quit, 20% of those in the lowest SSS quartile were abstinent versus 44% of those in the highest quartile. Results from two weeks post-quit were similar (16.4% versus 36.8%). Moreover, SSS remained a significant predictor of smoking abstinence in logistic regression analyses even after controlling for the effects of SES indicators. Thus, SSS yielded unique predictive information about the likelihood of successful smoking cessation over and above indicators of SES, which have been among the most robust predictors in the literature to date. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to demonstrate that SSS predicts smoking abstinence during a specific quit attempt. Results suggest that, even among a relatively low SES sample, quitting smokers who endorse low SSS may face significant hurdles in maintaining short-term abstinence.

Understanding more about the mechanisms underlying the association between SSS and smoking abstinence may help to improve cessation interventions for smokers endorsing low SSS. Given associations between SSS and affect [e.g., (23)], and affect and smoking relapse (26–30), the present study examined whether depression, stress, positive affect and/or negative affect on the quit day accounted for some proportion of the SSS-abstinence relationship. Results indicated that positive affect and depression mediated the relationship between SSS and abstinence in this diverse sample. Accordingly, smokers of low SSS might benefit from smoking cessation interventions that focus on increasing positive affect and decreasing depression. This might be accomplished by encouraging quitting smokers to increase their daily activity or by incorporating other aspects of Behavioral Activation into standard cessation counseling (51). This approach has shown promise for reducing depression among smokers in preliminary research (52), and may be particularly amenable to cultural tailoring for minority populations [cf. (53)]. Likewise, the incorporation of techniques designed to address cognitive biases such as overgeneralization and rumination may be appropriate as well [e.g., (54)]. Finally, individuals with enduring or clinical depression might benefit from the receipt of psychological or psychiatric services before and after quitting, including pharmacotherapy that addresses depression and nicotine dependence simultaneously. Comprehensive treatments for smoking cessation have been suggested for specialized populations such as low income pregnant women (55), and this study supports their potential utility among smokers with low SSS.

The extent to which affective reactivity on the quit day accounted for the SSS-abstinence association was also of interest. In this sample, quit day depression partially mediated the relationship between SSS and short-term abstinence even after adjusting for baseline depression. That is, unlike the other affective variables examined, reactivity to quitting as manifest in depressive symptoms on the quit day helped to explain why low SSS individuals had more difficulty maintaining abstinence than their high SSS counterparts. Previous research has also linked increases in affective symptoms on the quit date with relapse (28, 36, 37), but this study is the first to examine these associations in the context of SSS. Results suggest that smoking cessation interventions might focus on preparing low SSS smokers to expect and better cope with increases in depression on (or near) the quit day in order to avoid smoking relapse.

Another approach to reducing the SSS disparity in cessation could include interventions designed to increase the perceived social status of low SSS individuals. For example, social trust is linked to SSS (13, 14) and might be affected by increasing exposure to other community members through participation in volunteer (e.g., community clean-ups) or leadership (e.g., church or school Board of Directors) activities. Likewise, connecting participants with community-based job placement agencies, or other resources relevant to their needs, might increase their perception of future opportunities. Whether such interventions can affect increases SSS (and ultimately smoking cessation) is unknown, but could be examined in future research.

Strengths of this study include the diversity of the sample, which was comprised of approximately equal portions of Caucasian, African-American and Latino smokers, the use of biochemically-confirmed abstinence measures, and the longitudinal study design. Limitations include the use of questionnaire-based assessments during the acute withdrawal period, which are subject to recall biases and prohibit frequent administration. Future research might benefit from the use of ecological momentary assessment and longitudinal meditational analyses to examine how moment-to-moment assessments of relevant affective mediators influence the SSS-abstinence association. Importantly, our interpretation of these data assumes a causal and unidirectional relationship between SSS and mediators, and the absence of response bias. However, reciprocal relations could also be posited. Moreover, our interpretation assumes that the unique predictive ability of SSS over SES indicators is not based on measurement error. These assumptions have been supported in previous literature (e.g., 15, 56).

This study provides the first evidence that perceptions of social status are uniquely linked with smoking abstinence during the period of acute withdrawal following a quit attempt. Results suggest that smokers endorsing low SSS are likely to face significant obstacles in achieving abstinence due to the affective consequences of their relative social standing (i.e., depression and low positive affect). As smoking is becoming increasingly isolated among low SES groups (2–5), comprehensive interventions designed to aid these individuals in achieving and maintaining smoking abstinence are needed to affect tobacco-related health disparities. This study suggests that incorporating interventions designed to decrease depression and increase positive affect into smoking cessation treatment may be a promising approach.

Acknowledgments

The original clinical trial was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (R01DA014818) and this manuscript was supported by grants from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (K01DP001120) and the National Cancer Institute (R25T CA57730). This study was approved by the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Review Board.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: Authors have no conflicting interests that might be interpreted as influencing the research; however, we would like to report that P. M. Cinciripini has served as a Pfizer consultant within the last year.

References

- 1.Ries LG, Eisner MP, Kosary CL, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2001. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbeau EM, Krieger N, Soobader MJ. Working class matters: Socioeconomic disadvantage, race/ethnicity, gender, and smoking in NHIS 2000. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:269–78. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.2.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winkleby MA, Jatulis DE, Frank E, Fortmann SP. Socioeconomic status and health: How education, income, and occupation contribute to risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:816–20. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.6.816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Annual smoking-attributable mortality, years of life lost, and economic costs-United States 1995–1999. MMWR. 2002;51:300–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hughes J. The future of smoking cessation therapy in the United States. Addiction. 1996;91:1797–802. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1996.911217974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adler NE, Boyce T, Chesney MA, et al. Socioeconomic status and health. The challenge of the gradient. Am Psychol. 1994;49:15–24. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.49.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wardle J, Steptoe A. Socioeconomic differences in attitudes and beliefs about healthy lifestyles. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57:440–3. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.6.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jha P, Peto R, Zatonski W, et al. Social inequalities in male mortality, and in male mortality from smoking: Indirect estimation from national death rates in England and Wales, Poland, and North America. Lancet. 2006;368:367–70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68975-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fiore MC, Novotny TE, Pierce JP, et al. Trends in cigarette smoking in the United States. The changing influence of gender and race. JAMA. 1989;261:49–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pierce JP, Fiore MC, Novotny TE, Hatziandreu EJ, Davis RM. Trends in cigarette smoking in the United States. Educational differences are increasing. JAMA. 1989;261:56–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wetter DW, Cofta-Gunn L, Irvin JE, et al. What accounts for the association of education and smoking cessation? Prev Med. 2005;40:452–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adler N. Social Status Ladder. John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Research Network on Socioeconomic Status and Health. 2000 Available at http://www.macses.ucsf.edu/Research/Psychosocial/notebook/subjective.html.

- 13.Singh-Manoux A, Adler NE, Marmot MG. Subjective social status: Its determinants and its association with measures of ill-health in the Whitehall II study. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;56:1321–33. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00131-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franzini L, Fernandez-Esquer ME. The association of subjective social status and health in low-income Mexican-origin individuals in Texas. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:788–804. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adler NE, Epel ES, Castellazzo G, Ickovics JR. Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: Preliminary data in healthy white women. Health Psychol. 2000;19:586–92. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.6.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen S, Alper CM, Doyle WJ, et al. Objective and subjective socioeconomic status and susceptibility to the common cold. Health Psychol. 2008;27:268–74. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demakakos P, Nazroo J, Breeze E, Marmot M. Socioeconomic status and health: The role of subjective social status. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67:330–40. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu P, Adler NE, Goldman N, Weinstein M, Seeman TE. Relationship between subjective social status and measures of health in older Taiwanese persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:483–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mendelson T, Thurston RC, Kubzansky LD. Affective and cardiovascular effects of experimentally-induced social status. Health Psychol. 2008;27:482–9. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.4.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wright CE, Steptoe A. Subjective socioeconomic position, gender and cortisol responses to waking in an elderly population. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30:582–90. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghaed SG, Gallo LC. Subjective social status, objective socioeconomic status, and cardiovascular risk in women. Health Psychol. 2007;26:668–74. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.6.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh-Manoux A, Marmot MG, Adler NE. Does subjective social status predict health and change in health status better than objective status? Psychosom Med. 2005;67:855–61. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000188434.52941.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reitzel LR, Vidrine JI, Li Y, et al. The influence of subjective social status on vulnerability to postpartum smoking among young pregnant women. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:1476–82. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.101295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adler N, Singh-Manoux A, Schwartz J, et al. Social status and health: A comparison of British civil servants in Whitehall-II with European- and African-Americans in CARDIA. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:1034–45. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gianaros PJ, Horenstein JA, Cohen S, et al. Perigenual anterior cingulate morphology covaries with perceived social standing. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2007;2:161–173. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsm013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown RA, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Zvolensky MJ. Distress tolerance and early smoking lapse. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25:713–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kahler CW, Brown RA, Ramsey SE, et al. Negative mood, depressive symptoms, and major depression after smoking cessation treatment in smokers with a history of major depressive disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111:670–5. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.4.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCarthy DE, Piasecki TM, Fiore MC, Baker TB. Life before and after quitting smoking: An electronic diary study. J Abnorm Psychol. 2006;115:454–66. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.3.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cofta-Woerpel L, McClure JB, Li Y, et al. Early withdrawal among women attempting to quit smoking: Trajectories and volatility of urge and negative mood during the first post-cessation week. (nd). under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leventhal AM, Ramsey SE, Brown RA, LaChance HR, Kahler CW. Dimensions of depressive symptoms and smoking cessation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:507–17. doi: 10.1080/14622200801901971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hendricks PS, Ditre JW, Drobes DJ, Brandon TH. The early time course of smoking withdrawal effects. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;187:385–96. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0429-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hughes JR. Effects of abstinence from tobacco: Valid symptoms and time course. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9:315–27. doi: 10.1080/14622200701188919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Businelle MS, Kendzor DE, Reitzel LR, et al. Mechanisms linking socioeconomic status to smoking cessation: A structural equation modeling approach. (nd). under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kendzor DE, Costello TJ, Li Y, et al. Race/ethnicity and multiple cancer risk factors among individuals seeking smoking cessation treatment. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:2937–45. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fiore M, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence. Rockville, MD: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abrantes AM, Strong DR, Lejuez CW, et al. The role of negative affect in risk for early lapse among low distress tolerance smokers. Addict Behav. 2008;33:1394–401. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kenford SL, Smith SS, Wetter DW, et al. Predicting relapse back to smoking: Contrasting affective and physical models of dependence. J Consult Clin PSYCHOL. 2002;70:216–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Radloff L. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roberts RE. Reliability of the CES-D Scale in different ethnic contexts. Psychiatry Res. 1980;2:125–34. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(80)90069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kinnunen T, Doherty K, Militello FS, Garvey AJ. Depression and smoking cessation: Characteristics of depressed smokers and effects of nicotine replacement. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64:791–798. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.4.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nosek MA, Hughes RB, Wright G. Improving the health and wellness of women with disabilities: A symposium to establish a research agenda. [Accessed August 12, 2009];2003 http://www.crowdbcm.net/measures/Measures-I-Healthoutcomes.htm.

- 43.Wetter DW, Smith SS, Kenford SL, et al. Smoking outcome expectancies: factor structure, predictive validity, and discriminant validity. J Abnorm Psychol. 1994;103:801–811. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.4.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wetter DW, Fiore MC, Young TB, et al. Gender differences in response to nicotine replacement therapy: Objective and subjective indexes of tobacco withdrawal. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;7:135–44. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.7.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54:1063–70. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kenny DA. [Accessed April 01, 2009];Mediation. 2008 http://davidakenny.net/cm/mediate.htm#ST, last updated September 12, 2008.

- 47.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40:879–91. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–82. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hayes AF. SPSS INDIRECT macro for binary outcomes with a continuous mediator, personal communication with Y. Cao. Mar 16, 2009.

- 50.MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Brown CH, Wang W, Hoffman JM. The intermediate endpoint effect in logistic and probit regression. Clin Trials. 2007;4:499–513. doi: 10.1177/1740774507083434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jacobson NS, Martell CR, Dimidjian S. Behavioral Activation therapy for depression: Returning to contextual roots. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2001;8:255–270. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bercaw EL. A behavioral activation approach to smoking cessation for depressed smokers at veterans affairs medical centers. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering. 2008:5557. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Santiago-Rivera A, Kanter J, Benson G, et al. Behavioral Activation as an alternative treatment approach for Latinos with depression. Psychother Theory Res Pract Train. 2008;45:173–185. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.45.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Watkins ER, Baeyens CB, Read R. Concreteness training reduces dysphoria: Proof-of-principle for repeated cognitive bias modification in depression. J Abnorm Psychol. 2009;118:55–64. doi: 10.1037/a0013642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bullock L, Everett KD, Mullen PD, et al. Baby BEEP: A randomized controlled trial of nurses’ individualized social support for poor rural pregnant smokers. Matern Child Health J. 2009;13:395–406. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0363-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Operario D, Adler NE, Williams DR. Subjective social status: Reliability and predictive utility for global health. Psychology and Health. 2004;19:237–246. [Google Scholar]