Abstract

Host immune responses, including the characteristic influx of neutrophils, against Neisseria gonorrhoeae are poorly understood; adaptive immunity is minimal and nonprotective. We hypothesize that N. gonorrhoeae selectively elicits Th17-dependent responses which recruit innate defense mechanisms including neutrophils and antimicrobial proteins that it can resist. We found that N. gonorrhoeae induced production of IL-17 in mouse T cells and of Th17-inducing cytokines in mouse and human antigen-presenting cells in vitro. IL-17 was induced in the iliac lymph nodes in vivo in a female mouse model of genital tract gonococcal infection. Antibody blockade of IL-17 or deletion of the major IL-17 receptor in IL-17RA-knockoutmice led to prolonged infection and diminished neutrophil influx. Genital tract tissue from IL-17RA-knockout mice showed reduced production of neutrophil-attractant chemokines in response to culture with N. gonorrhoeae. These results imply a crucial role for IL-17 and Th17 cells in the immune response to N. gonorrhoeae.

INTRODUCTION

The discovery of Th17 cells as a distinct subset of CD4+ T cells has revolutionized our thinking about the relationship of innate and adaptive immunity. By producing IL-17 and other cytokines Th17 cells function as a bridge between these two arms of the immune system.1, 2 IL-17 can be either protective or pathogenic, as elevated IL-17 has been found in autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis,3, 4 whereas Th17 cells have been shown to exert protection against a variety of bacteria, including Klebsiella pneumoniae, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Escherichia coli, Bordetella pertussis, Staphylococcus aureus, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis, as well as fungi and even viruses.5–10 Development of Th17 cells and ensuing production of IL-17 occur earlier in infection than development of traditional Th1 and Th2 cells,1, 2 making them critical for bridging the innate and adaptive immune response.11

Differentiation and proliferation of Th17 cells is mediated by IL-6, TGF-β, IL-1β, and IL-23 (refs. 12, 13), which are produced by antigen-presenting cells in response to microbial infection, following recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns.14, 15 In addition to its role in the development and maintenance of Th17 cells, IL-23 plays an independent and essential role in defense against some pathogens by stimulating production of other factors such as IL-22 (ref. 16). The IL-17 receptor A (IL-17RA) is widely distributed on endothelial and epithelial cells, osteoblasts, and fibroblasts, and its ligation induces the expression of neutrophil-recruiting chemokines, such as KC (CXCL1), LIX (CXCL5), and MIP-2α (CXCL2) in mice or IL-8 in humans, as well as granulocyte-colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF).9, 17–20 In extracellular infections where neutrophils are important in host defense, including K. pneumoniae, P. gingivalis and Candida albicans, deficiency of IL-17RA leads to reduction of chemokine levels and neutrophil recruitment in infected tissues.9, 10, 21, 22 In addition to neutrophil recruitment, IL-17, along with IL-22, plays other roles in immune defense, including the production of soluble defense factors by epithelial cells, such as β-defensins, lipocalin 2, and S100 proteins.23

Gonorrhea is a sexually transmitted infection of widespread abundance throughout the world: the World Health Organization estimates that >60 million new infections occur annually.24 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report >300,000 cases annually in the USA,25 and it may be re-emerging in Europe. No vaccine is available to control the disease and the continuing development of resistance to antibiotics causes concern that treatment options could become limited. Gonorrhea typically presents as an acute purulent genital tract infection caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and is characterized by the presence of gram-negative diplococci associated with neutrophils in the exudate. Despite the evident inflammatory response, it is well known that gonorrhea does not induce a state of protective immunity against repeat infection.26–28 N. gonorrhoeae induces several proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, IL-1β, and TNFα, which have been implicated in Th17 responses, but not IL-12 or IFNγ.28–32 At present, the mechanisms that govern host responses to N. gonorrhoeae including the neutrophil influx are not well understood.

We propose that Th17 cells play a significant role in the immune response to N. gonorrhoeae through recruitment of neutrophils and other innate defense factors. We have tested this hypothesis in a mouse model of N. gonorrhoeae genital tract infection. Our results indicate that N. gonorrhoeae induces IL-17 production in vitro and in vivo, leading to IL-17-dependent secretion of IL-6, LIX, and MIP-2α from genital tract tissues. Furthermore, blocking of IL-17A with antibody, or deletion of IL-17RA in mice prolongs the course of infection with N. gonorrhoeae and delays the recruitment of neutrophils.

RESULTS

Production of cytokines in response to N. gonorrhoeae

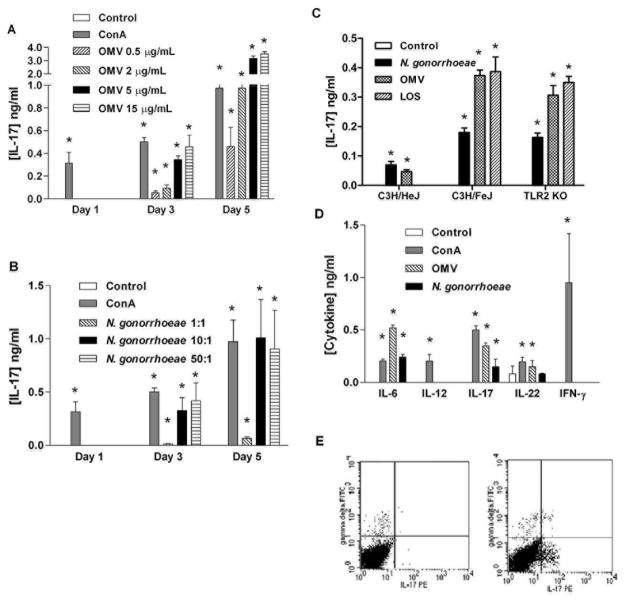

To determine whether N. gonorrhoeae is capable of inducing cytokines typical of a Th17 response, we incubated mouse splenic mononuclear cells with either N. gonorrhoeae or gonococcal OMV and teste d the supernatants for secreted cytokines. After three days, the cells produced IL-17, in response to either N. gonorrhoeae FA1090 or its outer membranes, as well as the mitogen ConA (Figure 1A, B). IL-17 production increased with time of incubation and dose of OMV, through 5 days with 5 μg/ml of OMV; no significant increase in IL-17 occurred at higher OMV concentrations. Similar results were seen with N. gonorrhoeae strain MS11, and with an Opa-protein deletion mutant of strain FA1090 (ref. 33; data not shown). Heat treatment of OMV preparations (100°C for 10 min) did not abrogate the induction of IL-17 (data not shown), suggesting that the stimulatory components were heat-stable. Therefore to determine whether lipo-oligosaccharide (LOS) was responsible for inducing IL-17, LOS from N. gonorrhoeae strain PID2 and corresponding gonococci were cultured with spleen cells from either C3H/HeJ (TLR4-deficient), C3H/FeJ (TLR4-normal), or TLR2-knockout mice. Gonococcal LOS induced IL-17 production in TLR4-normal (and TLR2-deficient) cells, but not in TLR4-deficient cells (Figure 1C). Furthermore the IL-17 response to gonococci or OMV was diminished (but not completely abrogated) in TLR4-deficient cells, whereas TLR2-knockout cells were responsive to gonococci or OMV (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

N. gonorrhoeae induces Th17-associated cytokines, but not Th1-associated cytokines. (A) Production of IL-17 from mouse splenic mononuclear cells, incubated in medium only (control) or with 2 μg/ml ConA or N. gonorrhoeae outer membrane vesicles (OMV) at various concentrations for either 1, 3, or 5 days. Supernatants were assayed for IL-17 by ELISA. (B) Production of IL-17 from mouse splenic mononuclear cells, incubated in medium only (control) or with 2 μg/ml ConA or N. gonorrhoeae at various multiplicities of infection (MOI) for either 1, 3, or 5 days. Supernatants were assayed for IL-17 by ELISA. (C) Production of IL-17 from C3H/HeJ (TLR4-deficient), C3H/FeJ (TLR4-normal), or TLR2-knockout mouse splenic mononuclear cells incubated for 3 days in medium only (control), or with N. gonorrhoeae PID2 at MOI 10:1, or with OMV (5μg/ml), or LOS (5μg/ml). Supernatants were assayed for IL-17 by ELISA. (D) Production of IL-6, IL-12, IL-17, IL-22, and IFN-γ from mouse splenic mononuclear cells incubated for 3 days in medium only (control) or with 2 μg/ml or 5 μg/ml of OMV, or N. gonorrhoeae at an MOI of 10:1. Supernatants were assayed for cytokines by ELISA. All experiments (A-D) were conducted in triplicate, and results are shown as mean ±SD; * indicates cytokine secretion significantly above control levels (P<0.01; Student’s t). (E) Flow cytometry profiles of murine spleen cells cultured for 3 days with gonococcal OMV (right panel), compared to control unstimulated cells (left panel). Cells were stained for intracellular IL-17 (PE) and surface γδ-T cell receptor (FITC).

In addition, supernatants from spleen cells cultured with gonococci or OMV showed production of IL-22 and IL-6, but a lack of IFN-γ (Figure 1D), consistent with the development of a Th17 response. Production of IL-12, a hallmark of a Th1 response, was not observed at any time point in response to gonococcal stimulation. The ability of N. gonorrhoeae to induce secretion of IL-17, IL-22, and IL-6, but not IFN-γ in mouse spleen cell cultures, suggests that it is capable of eliciting Th17 responses. As determined by flow cytometry, some of the cells that produced IL-17 were γδ rather than αβ T cells (Figure 1E).

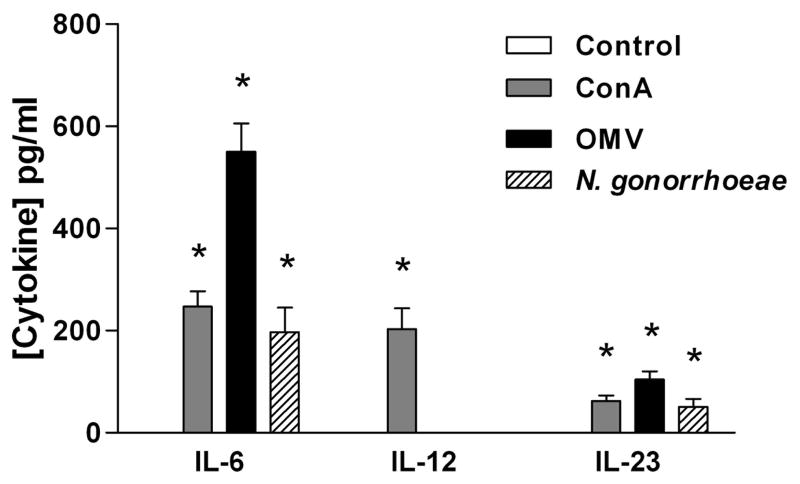

However, IL-23, was not detected in cultures of spleen mononuclear cells stimulated with gonococci or ConA. It is possible that IL-23 was produced but not detected because of rapid uptake by T cells. Therefore, we determined whether gonococci could selectively induce IL-23 production by APC alone. When mouse BMDC were incubated with N. gonorrhoeae or its OMV for 24 hours, IL-6 and IL-23 were detected in the supernatants, whereas IL-12 production was produced only in control cultures stimulated with ConA (Figure 2). Therefore, we conclude that N. gonorrhoeae preferentially stimulates dendritic cells to secrete IL-23 which in turn promotes differentiation of Th17 cells, but not IL-12 which promotes Th1.

Figure 2.

BMDC produce IL-6 and IL-23 but not IL-12 in response to N. gonorrhoeae or its OMV. BMDCs were incubated for 24 hours in medium only (control) or with 2 μg/ml of ConA, N. gonorrhoeae at 25:1 MOI, or 5 μg/ml of gonococcal OMV. Supernatants were collected and assayed for cytokines by ELISA. All experiments were conducted in triplicate, and results are shown as mean ±SD; * indicates cytokine secretion significantly above control levels (P<0.05; Student’s t).

Production of Th17-associated cytokines by human THP-1 cells

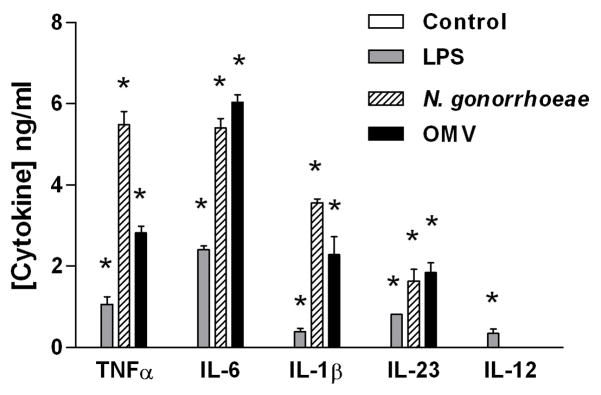

In order to determine whether N. gonorrhoeae is capable of inducing cytokines that lead to a Th17 response in human cells, we incubated human THP-1 macrophage-like cells with either N. gonorrhoeae cells, gonococcal OMV, or E. coli LPS. Within one day, differentiated THP-1 cells produced the proinflammatory cytokines IL-6, TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-23 (Figure 3), similar to the results obtained with mouse splenocytes or BMDC. Likewise, production of IL-12 was not observed in response to N. gonorrhoeae, although it was detected in response to E. coli LPS. Accordingly, human APC produce Th17- rather than Th1-biasing cytokines in a similar fashion to mouse cells.

Figure 3.

The human monocyte-like cell line THP-1 produces Th17-associated cytokines in response to N. gonorrhoeae or its OMV. Differentiated THP-1 cells were incubated for 24 hours in medium only (control) or with 5 μg/ml−1 of LPS, 5 μg/ml of gonococcal OMV, or N. gonorrhoeae at an MOI of 25:1. Supernatants were assayed for cytokines by ELISA. All experiments were conducted in triplicate, and results are shown as mean ±SD; * indicates cytokine secretion significantly above control levels (P<0.01; Student’s t). LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MOI, multiplicity of infection; OMV, outer membrane vesicle.

Role of IL-17 in murine vaginal gonococcal infection

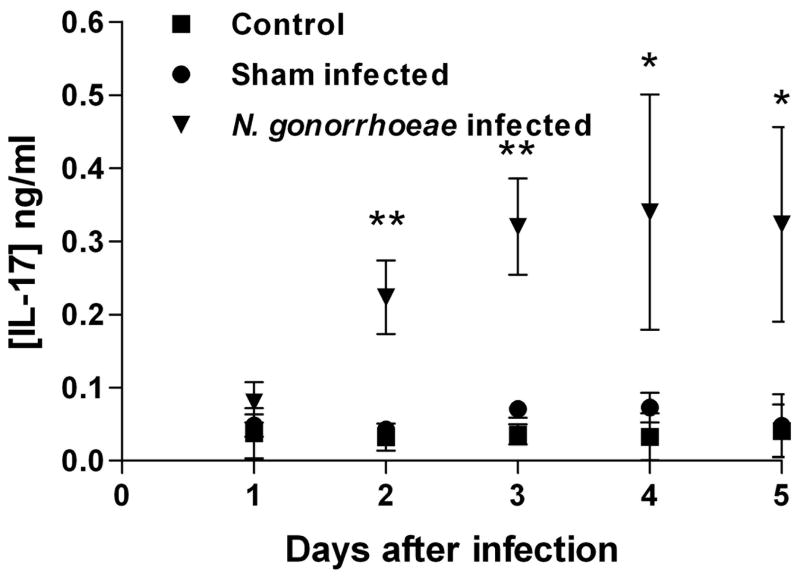

To determine whether IL-17 is generated in vivo in response to N. gonorrhoeae, we employed a previously described mouse genital tract gonococcal infection model.34 Mice were treated with estradiol and antibiotics, challenged with live gonococci, and the course of infection was monitored by vaginal culture. Two groups of control mice were included: estradiol- and antibiotic-treated mice which were sham-infected with vehicle only, and unmanipulated control mice. Draining iliac lymph nodes were removed (from separate groups of mice) starting one day after infection and continuing for five days; the cells were cultured overnight, and IL-17 was measured in supernatants. Starting two days after infection, IL-17 production was observed, with production peaking after 3 days and continuing for the duration of infection (Figure 4). Thus mice produce IL-17 in vivo when infected with N. gonorrhoeae.

Figure 4.

Production of IL-17 from draining iliac lymph node cells from mice infected with N. gonorrhoeae, or sham infected, or unmanipulated controls. Lymph nodes were collected on days 1–5 after infection and supernatants were assayed for IL-17 by ELISA after culture for 24 hours. Results are shown as mean ±SD of triplicate cultures of lymph nodes pooled from 3 mice per time point. For days 2–5, the difference between infected and sham infected mice was statistically significant, ** P<0.005, * P<0.05 (Student’s t).

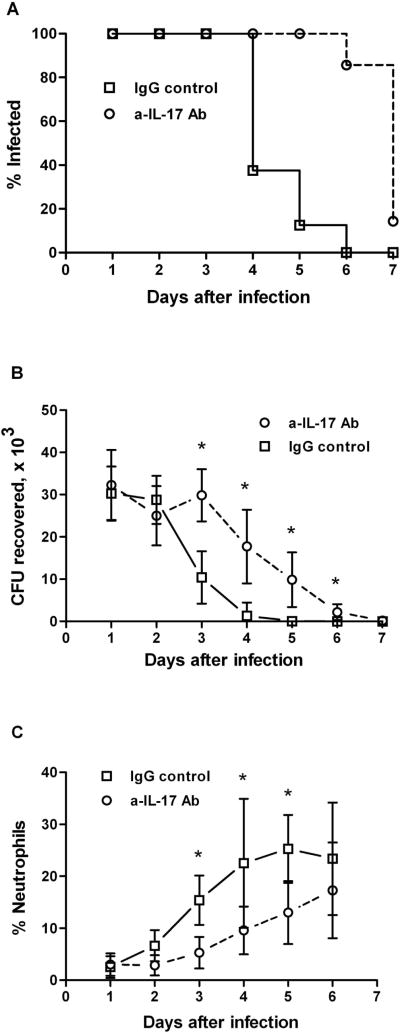

To determine whether IL-17 plays a significant role in this infection model, BALB/c mice were treated with anti-IL-17 blocking antibody before and during the infection, while control mice were similarly treated with rat IgG. All mice were treated with estradiol and antibiotics, and challenged with live gonococci as described in Methods. The course of infection was monitored by vaginal culture, and the neutrophil influx was determined by microscopic examination of vaginal swabs. Three days after infection, mice that were treated with the isotype control Ig showed diminished numbers of recoverable N. gonorrhoeae. In contrast, mice treated with the anti-IL-17 antibody exhibited significantly prolonged infection (P<0.001) and higher recoverable bacterial loads after day 3 (P<0.05; Figure 5A, B). Neutrophil influx into the genital tracts, determined relative to the epithelial cells in vaginal smears, began on day 3 in control mice, but was delayed until day 4–5 in IL-17 antibody-treated mice and remained at a lower level throughout the duration of the experiment (Figure 5C). These results show that blockade of IL-17 during N. gonorrhoeae infection inhibits neutrophil recruitment and enhances the course of infection in this mouse model.

Figure 5.

Blocking of IL-17A prolongs gonococcal genital tract infection and delays the recruitment of neutrophils in mice. BALB/c mice were treated with anti-IL-17 antibody (n=7) or rat IgG (n=8) and infected vaginally with N. gonorrhoeae. The course of infection was monitored by culture of vaginal mucus, and the neutrophil influx was determined by microscopic examination of vaginal smears. (A) Percentage of mice infected with N. gonorrhoeae; survival curves are significantly different (P<0.001; Kaplan-Meier). (B) Number of recoverable N. gonorrhoeae (CFU), mean ±SD; * indicates significant difference between treated and control groups (P<0.05; Student’s t). (C) Neutrophil influx, measured as the percentage of neutrophils relative to other cells, mean ±SD; * indicates significant difference between treated and control groups (P<0.05; 2-way ANOVA).

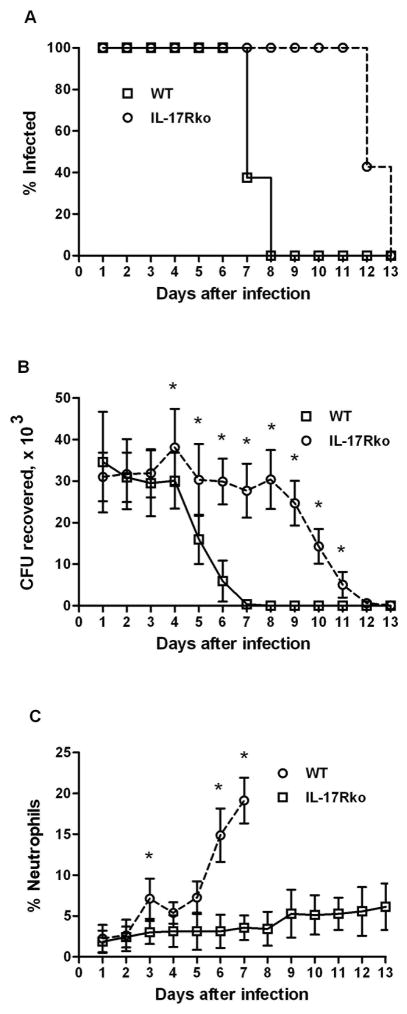

To confirm the importance of signaling through the IL-17 receptor in the response to vaginal infection with N. gonorrhoeae, we repeated the experiment using IL-17RAKO mice,9 which lack the principal receptor for IL-17A. In this experiment, C57BL/6 WT or IL-17RAKO mice were treated with estradiol and antibiotics, then challenged with 5 × 106 CFU and sampled for recoverable gonococci and neutrophil influx for the ensuing 7–10 days. Wild type control mice started to reduce the recoverable gonococcal load from day 4 and had cleared the infection by day 7 (Figure 6A, B). In contrast, IL-17RAKO mice began to reduce the gonococcal load on day 9 and took 12 days to clear the infection; the difference in persistence of infection was significant (P<0.001). The neutrophil influx, which began on day 3 in control mice was almost completely abrogated in IL-17RAKO mice (Figure 6C). These results indicate that IL-17RA is important in neutrophil recruitment and clearance of N. gonorrhoeae in this mouse model.

Figure 6.

Prolongation of infection and suppression of neutrophil recruitment in IL-17RAKO mice. IL-17RAKO (n=7) or wild-type (n=8) C57BL/6 mice were infected vaginally with N. gonorrhoeae. The course of infection was monitored by culture of vaginal mucus, and the neutrophil influx was determined by microscopic examination of vaginal smears. (A) Percentage of mice infected with N. gonorrhoea e; survival curves are significantly different (P<0.001; Kaplan-Meier). (B) Number of recoverable N. gonorrhoeae (CFU), mean ±SD; * indicates significant difference between IL-17RAKO and WT groups (P<0.05; Student’s t). (C) Neutrophil influx, measured as the percentage of neutrophils relative to other cells, mean ±SD; * indicates significant difference between IL-17RAKO and WT groups (P<0.05; 2-way ANOVA).

IL-17-mediated induction of cytokines and chemokines in the genital tract

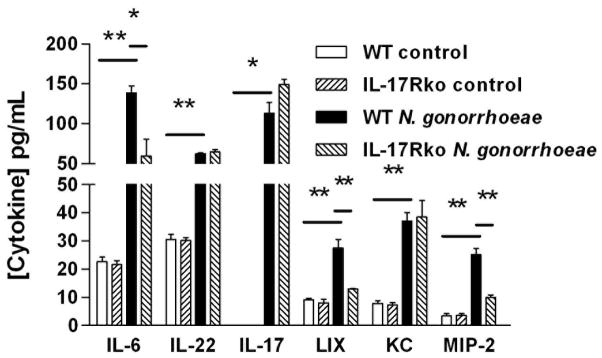

To examine the production of cytokines and chemokines by the mouse genital tract, vaginal explants were cultured in vitro with or without live N. gonorrhoeae. Supernatants were recovered after 3 days and assayed by ELISA. Consistent with the observed production of cytokines in draining lymph nodes after in vivo infection, IL-6, IL-22, and IL-17A were detected in supernatants of wild-type vaginal tissue cultured with N. gonorrhoeae, but not in control (unstimulated) cultures (Figure 7). These supernatants also contained CXC chemokines KC, LIX and MIP-2α (Figure 7). Supernatants of vaginal explants from IL-17RAKO mice contained IL-17, IL-22, and KC at the same levels as wild-type tissue, but showed diminished levels of IL-6, LIX, and MIP-2α (Figure 7). Such diminished chemokine production was consistent with defective neutrophil recruitment in vivo seen in IL-17RAKO mice, or in those injected with IL-17A-blocking antibodies. Collectively, these experiments show that production of neutrophil-attractant chemokines in response N. gonorrhoeae is at least partially IL-17 dependent.

Figure 7.

Production of cytokines and chemokines from mouse vaginal explants cultured with N. gonorrhoeae. Genital tract tissue segments from wild type or IL-17RAKO mice were incubated in vitro in medium only (control) or with N. gonorrhoeae at a concentration of 1 × 107 CFU/ml. Supernatants were removed after 3 days and assayed for cytokines and chemokines by ELISA. Results are shown as mean ±SD of triplicate cultures. Cytokine or chemokine production in the presence of N. gonorrhoeae was significantly higher than in corresponding controls or in IL-17RAKO cultures, ** P<0.01, * P<0.05 (Student’s t).

DISCUSSION

Using a female mouse model of genital tract infection we have demonstrated a significant role for the newly described “Th17 axis of immunity” in response to N. gonorrhoeae. The evidence for this consists of the following. N. gonorrhoeae induces the production in vitro of the signature Th17 cytokine, IL-17A, as well as several other key cytokines of the Th17 pathway in murine mononuclear cell cultures. These cytokines include IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α, which are known to be important for inducing the development of the Th17 lineage from naive CD4+ T cell precursors.12, 13 The majority of IL-17-secreting cells were CD4+ αβ T cells, but some γδ T cells also secreted IL-17A in response to N. gonorrhoeae. Notably we did not detect IL-12 production, either in spleen cell cultures, dendritic cell cultures, or genital tract explants. Previous reports of cytokine induction by N. gonorrhoeae failed to detect IL-12 (p70),30–32 which is well known to direct the development of Th1 cells. The related cytokine, IL-23, which shares the common p40 chain with IL-12, and is a key cytokine for the maintenance and functional differentiation of Th17 cells,12 was also not detected in supernatants of spleen cells cultured with N. gonorrhoeae or in genital tract explants. However, when murine BMDC were cultured with N. gonorrhoeae, production of IL-23 was observed, along with IL-6, but not IL-12. Importantly also, human THP-1-derived macrophages also produced IL-23 as well as IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α, but not IL-12, when stimulated with N. gonorrhoeae, implying that in this respect human and mouse APC behave similarly in response to N. gonorrhoeae.

The components of N. gonorrhoeae that induce IL-17 appear to be predominantly heat-stable materials including LOS, rather than proteins, and particularly not Opa proteins. Moreover, the in vitro response to gonococci was diminished in the absence of TLR4, but not in the absence of TLR2. However, the residual response of TLR4-deficient spleen cells to gonococcal cells or OMV suggests that other components could be involved as well. Our ongoing analysis of the host response to N. gonorrhoeae during experimental infection of TLR4-deficient mice further supports a link between TLR4 signaling and IL-17 expression (M. Packiam, S.J. Veit, N. Mavrogiorgos, R.R. Ingalls, and A.E. Jerse, unpublished data). Although different strains of mice vary in susceptibility to vaginal gonococcal infection,35 we observed no great differences between production of IL-17A by spleen cells from BALB/c, C57BL/6, or C3H wild-type mice upon culture with N. gonorrhoeae.

To investigate the production and role of IL-17A in response to N. gonorrhoeae infection in vivo, we used the mouse model of lower genital tract infection.34 IL-17A was released into culture supernatants of mononuclear cells from iliac lymph nodes, which drain the genital tract, collected from mice challenged with N. gonorrhoeae, but not sham-challenged mice. Production of IL-17A was observed in cells obtained from mice that been infected at least two days and continued for the duration of the infection. This finding suggests that Th17 cells constitute a component of the response to N. gonorrhoeae in vivo.

To examine further the significance of IL-17A production and its role in eliciting innate immune defenses including the characteristic influx of neutrophils into the genital tract in response to gonococcal infection, we used two approaches. First we used antibody-mediated blockade to inhibit the interaction of IL-17A with its main receptor, IL-17RA. Treatment of mice with monoclonal antibody to murine IL-17RA was only partially effective in inhibiting the neutrophil influx or altering the course of infection with N. gonorrhoeae (data not shown). However, treatment of mice with monoclonal antibody to murine IL-17A prolonged infection with N. gonorrhoeae by 2–3 days concomitant with diminished influx of neutrophils, strongly suggesting that IL-17A-mediated responses are important for these outcomes. This conclusion was strengthened by experiments using IL-17RAKO mice which lack the main receptor for IL-17A (ref. 9). These mice failed to show a measurable neutrophil influx in response to gonococcal challenge, and they took 4–5 days longer to clear the infection than their wild-type counterparts. Despite the apparent lack of neutrophil influx, however, the IL-17RAKO mice eventually cleared the infection, suggesting that although phagocytosis of N. gonorrhoeae by neutrophils might contribute to their elimination, clearance was not absolutely dependent on neutrophils. It is likely that many factors are involved in the clearance of infection, or failure to sustain colonization, especially as the mouse is not a natural host for N. gonorrhoeae.

Some insight into the mechanisms involved in IL-17A-dependent responses against N. gonorrhoeae was obtained from experiments with explants of murine genital tract cultured in vitro with N. gonorrhoeae. Assay of the supernatants from these cultures revealed the release of IL-6, IL-17A and IL-22, but also the release of CXC chemokines KC, LIX, and MIP-2, which are chemotactic for neutrophils.36 Notably, while the production of IL-17A and IL-22 was unimpaired in cultures of explants derived from IL-17RAKO mice, production of two of the chemokines, LIX and MIP-2, was diminished, suggesting their dependence on signaling through IL-17RA. Upregulation of CXC chemokines is a well-known effect of IL-17A on target IL-17RA-bearing cells; thus this finding is consistent with a key role for IL-17A.19

One of the acknowledged difficulties in investigating the pathogenesis of and immunity to N. gonorrhoeae is the lack of accessible animal models that reflect the human disease. Despite numerous efforts over several decades to devise alternatives to non-human primates,37 the only currently available model is the female mouse lower genital tract infection model.34 The infections persist for 5–12 days (or even longer in some cases38) depending on the strain of mouse and other factors. Bacterial replication and antigenic variation of Opa proteins occur during infection, and there is a host response,34, 39 indicating that this is an infection model. Moreover, the mice usually show a local neutrophil influx, as occurs in symptomatic human infection, thereby indicating an inflammatory response by the mice. Whether or not neutrophils are responsible for phagocytic clearance of the infection is debatable since it is known that N. gonorrhoeae can survive intracellular killing mechanisms within neutrophils.40–43 Although clearance appears to follow the neutrophil influx, other mucosal defense mechanisms might contribute importantly to this. However, the nature of these defenses and the mechanisms involved in their recruitment have not been understood, and numerous other factors undoubtedly limit the ability of N. gonorrhoeae to infect mice persistently. Furthermore, similar to humans, mice do not develop detectable antibody responses to vaginal gonococcal infection after either primary or secondary infection, and secondary infection is no more effectively resisted than primary infection.39 Thus mice afford an opportunity to study early in vivo responses of the immune system to gonococcal exposure.

Studies of immunity to gonorrhea have been fraught with difficulty over many decades. In large part this is due to the extraordinary antigenic variability of N. gonorrhoeae in which all the major surface components are subject to phase-variable on-off switching, genetic polymorphism, and recombinatorial expression.27, 37 This variability has greatly complicated the evaluation of antibody responses in serum and secretions of infected subjects. While some studies have revealed modest increases of serum antibodies to porin, the major OMP, and some evidence has been obtained for partial serovar-specific immunity in very highly exposed persons,44 the overall consensus from multiple studies, including sequential studies, is that specific adaptive immune responses to gonorrhea are minimal.28, 45, 46 Studies on cell-mediated immunity are few, although T cell proliferation and cytokine secretion have been reported.28, 47 However, it is well known that gonorrhea does not induce a state of protective immunity against future infection.26 Repeat infections are common, and they occur with no apparent diminution in severity, duration, or probability of acquisition from exposure. The conventional view is that N. gonorrhoeae can resist host responses by a combination of strategies including antigenic variation which enables it to evade destruction by specific immune defenses, as well as several mechanisms for resisting complement activation and lysis.48–50 An alternative view now emerging is that N. gonorrhoeae avoids inducing adaptive immune responses in the first place, and elicits instead innate immune responses that it is capable of resisting. In other words, like many pathogens that have become evolutionarily well-adapted to their hosts, N. gonorrhoeae induces host responses that are favorable to its survival. We propose that the elicitation of IL-17 and other Th17-driven responses by N. gonorrhoeae is an example of this strategy. Th17 cells function as a bridge between adaptive and innate immunity, through the production of the cytokines IL-17, IL-22, and others.13 Receptors for IL-17 are widely distributed on epithelial, endothelial, and stromal cells, and ligation by IL-17A and/or IL-17F leads to signaling pathways that can result in secretion of factors involved in innate defense mechanisms. 13 These include GCSF which mobilizes neutrophils from the bone marrow reserves, and CXC chemokines KC, LIX, and MIP-2 in mice, or IL-8 in humans, which direct neutrophils to the site of microbial invasion and to some extent activate them.36 IL-17A and IL-22 act on mucosal epithelial cells to induce the secretion of several potent anti-microbial proteins including β-defensins, S-100 proteins, RegIIIγ, and lipocalin-2 (ref. 13). The effects of all these on N. gonorrhoeae are not yet known, but it can resist destruction by defensins in part through a multiple drug exporter mechanism.51 In addition, intracellular residence within neutrophils,43 where it can resist intracellular killing mechanisms, or within epithelial cells,52 may enable it to escape from soluble anti-microbial factors.

The diversion of host responses towards Th17 and away from Th1- or Th2-driven adaptive immunity may be one mechanism of evading the generation of specific immune responses, including antibodies that might, if directed to appropriate antigenic epitopes, be effective in destroying N. gonorrhoeae. Recent studies have implicated IL-17A in the suppression of Th1 cells.53 In this context it is noteworthy that, both in our experiments and in several other reports,30–32 IL-12, a key cytokine in the induction of Th1 responses, was not observed. In addition, it is possible that inducible T regulatory (iTreg) cells could form part of the host response pattern elicited by N. gonorrhoeae, as already suggested in the mouse model.54 It is noteworthy that iTreg and Th17 lineages appear to be closely related in that both are driven by the key cytokine, TGF-β. Whereas TGF-β acting alone programs CD4+ precursor T cells to develop as iTreg cells, TGF-β in the presence of IL-6 or IL-1 drives the development of Th17 cells.12 Conceivably therefore, a crucial factor in the nature of the host response to N. gonorrhoeae may be whether IL-6 or IL-1 is also generated by the responding APC. In an earlier study of the cytokine responses of humans infected with gonorrhea we observed the presence of IL-6 and IL-1 in the serum and secretions of some, but not all, infected patients.28 The significance of those findings for Th17 responses, which had not been described at that time, was not understood, and therefore cytokine responses in human subjects presenting with different clinical manifestations of gonococcal infection deserve re-evaluation, especially by exploiting newer and more sensitive technologies.

Overall the evidence from thes e studies in a murine model of gonococcal genital tract infection reveals that IL-17 and Th17 cells represent an entirely novel aspect of the host immune-inflammatory response to N. gonorrhoeae. If this applies also to the human infection, then it may represent a new paradigm in our understanding of this underappreciated, yet all too frequent human disease. Studies are in progress to address that important question.

METHODS

Mice

IL-17RAKO miceon a C57BL/6 background were kindly provided by Amgen (Seattle, WA). Wild type mice (C57BL/6 and BALB/c) mice were obtained from Harlan Sprague Dawley (Indianapolis, IN). C3H/HeJ and C3H/FeJ mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). TLR2-knockout mice (C57BL/6 background) were kindly provided by Dr. Terry Connell (University at Buffalo). Mice were kept in HEPA-filtered cages with autoclaved food, water, and bedding. For each experiment, the animals used were age- and strain-matched females between 8–10 weeks of age. All procedures wereperformed in accordance with protocols approved by the Universityat Buffalo Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and in accordance with Federal and State regulations governing animal welfare.

Bacteria

N. gonorrhoeae FA1090 (streptomycin-resistant, serum-resistant),55 kindly provided by Dr. Janne Cannon (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill), was used in most experiments. N. gonorrhoeae strain PID2 and its purified LOS were obtained from Dr. Gary Jarvis (University of California San Francisco). Bacteria were cultured on GC agar supplemented with hemoglobin and Isovitalex (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) in an atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37°C and the resultant growth was checked for colony morphology consistent with Opa protein and pilus expression. Bacteria were harvested from plates with a sterile inoculating loop after 18–24 hours of growth and suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Bacterial cell density was determined by measuring the optical density at 600 nm and reference to a previously determined calibration curve.

Gonococcal outer membrane vesicles (OMV)

N. gonorrhoeae was grown on chocolate agar plates in an atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37°C overnight. Colony morphology was examined to confirm Opa protein and pilus expression. Bacteria were harvested from plates into ice-cold lithium acetate buffer (pH 5.8) and passed through a 25-gauge needle 10–12 times to sheer the outer membranes from the bacteria. The suspensions were spun in microfuge tubes at 13,000 RPM for one minute. The supernatants were collected and ultracentrifuged at 107,000×g for 2 hours. The pellet was collected and resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8.0.

Splenic cells

Mouse mononuclear cells were isolated from aseptically harvested spleens using Histopaque 1083 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) density gradient centrifugation. The number of viable cells obtained was generally over 90% as determined by trypan blue (InVitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) dye exclusion cell counts. Cells were cultured in 6 or 24 well culture plates at a cell density of 2 × 106 cells/ml with either no stimulus, 2 μg/ml of the mitogen Concanavalin A (ConA), 5 μg/ml of N. gonorrhoeae OMV, or live N. gonorrhoeae cells at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10:1. Supernatants were collected from the cell cultures after 1–5 days and assayed for IL-1β, TNFα, IL-12, IL-17, IL-6, IFN-γ, and IL-22 by ELISA using kits from eBioscience and BD Biosciences.

Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDC)

Mouse femurs and tibias were removed and muscle was removed from the bones. The bones were immersed in 70% ethanol for two minutes and washed with cold RPMI-1640. Both epiphyses of each bone were cut off and the marrow was flushed out of the shafts with RPMI. Red blood cells were removed by lysing with ammonium chloride. Viable cells were suspended at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/ml and cultured in the presence of 1 ng/ml of murine GM-CSF. The cells were washed and fed every two days and microscopically monitored for the formation of dendrites and adherence to the culture wells, which is consistent with the development of dendritic cells. After 1 week of culture, either E. coli LPS as a positive control or N. gonorrhoeae OMV was added to the cultures; control cultures were continued in medium only. The cells were then incubated for 24 hours and supernatants were harvested and assayed for the production of IL-12, IL-23, and IL-6.

THP-1 cells

Human monocyte-like THP-1 cells (ATCC TIB-202) were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM L-glutamine, 10 mM HEPES, 100 U/ml penicillin G, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 0.05 mM 2-mercapthoethanol. THP-1 cells (1.5 × 105 cells per well) were differentiated for 3 days in the presence of 10 ng/ml phorbol myristate acetate. The cells were then incubated with either no additional stimulus, 5 μg/ml Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide (LPS; Sigma), 5 μg/ml gonococcal OMV, or N. gonorrhoeae at an MOI of 25:1. Supernatants were removed after 24 hours and assayed for of IL-6, TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-23 by ELISA (eBioscience).

Murine vaginal infection model

Female mice between 8 and 10 weeks old were infected with live N. gonorrhoeae as previously described by Jerse,34 with the modification that water-soluble estradiol was used as described by Song et al.39 Briefly, groups of 10–12 mice in diestrus or anestrus were identified by examination of stained vaginal smears and injected subcutaneously with 500 μg of 17β-estradiol two days before infection (day -2); estradiol treatment was repeated on days 0 and 2. To reduce the overgrowth of flora that occurs under the influence of estradiol, mice were injected intraperitoneally with streptomycin (0.6mg) and vancomycin (3.6mg) twice daily for the duration of the experiment, and trimethoprim sulfate (0.4 mg/ml) was added to the drinking water. For IL-17 blockade experiments, mice were injected on days -1, 0, and every two days thereafter with 70 μg of either rat monoclonal IgG2a anti-IL-17 blocking antibody (M210) kindly provided by Amgen, or rat IgG control (Caltag, Burlingame, CA). On day 0 mice were infected with 2 × 106 colony-forming units (CFU) of N. gonorrhoeae freshly harvested after growth for 18 hours and suspended in 20 μl of PBS. Bacterial colonization loads were determined daily by collecting vaginal mucus with a sterile swab and suspending it in 100 μl of PBS, followed by serial dilution and culture on chocolate agar containing the selective antibiotics vancomycin, colistin, nystatin, trimethoprim sulfate, and streptomycin (VCNTS). Plates were incubated overnight in 5% CO2/air at 37°C and colonies counted. Commensal bacteria were monitored by culturing a portion of the swab contents on brain-heart infusion (BHI) agar. Vaginal mucus was also smeared onto glass slides, stained with Hema 3 staining solution (Fisher Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI), and the number of neutrophils relative to 100 vaginal epithelial cells was counted. Mice that developed an overgrowth of commensal flora were eliminated, leaving at least 7 animals per group to complete the experiment.

Generation of IL-17 in vivo

Mice were either left untreated, mock infected with vehicle only, or infected with N. gonorrhoeae. On days 1 through 5, mice were sacrificed, and draining iliac lymph nodes were excised and teased apart to release the cells, which were then passed through a cell strainer and washed. Approximately 2 × 106 cells/ml were cultured for 24 hours in 5% CO2/air at 37°C. Supernatants were removed and assayed for IL-17 and other cytokines using ELISA kits (eBioscience).

Vaginal explants

Mouse genital tracts were dissected out aseptically and washed with Hanks’ buffered salt solution. The tissue was manually separated into 1–2 mm pieces, washed again and weighed. Equal weights were added to each well of the cell culture plates. Tissue was grown in 5% CO2/air at 37°C in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 10 mM HEPES, 100 U/ml penicillin G, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 1 μg/ml fungizone. The explants were cultured for 3 days with 2 × 107 N. gonorrhoeae/ml or 2 μg/ml of ConA, or in medium only (controls). Supernatants were removed and assayed for IL-6, IL-17A, IL-22, LIX, KC, and MIP-2α by means of ELISA using reagents and kits obtained from eBioscience or R&D Systems.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was peformed using Prism 5 (GraphPad Software). Student’s t test or two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test was used to determine the significance of difference of means, and Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was used to evaluate the persistence of infection in mice, using the log-rank test. P<0.05 (two-tailed) was considered significant.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dawn Both-Kim for technical assistance, and Amgen for graciously providing IL-17RAKO mice and antibodies to IL-17 and IL-17R. Dr. Gary Jarvis (University of California San Francisco) kindly provided gonococcal LOS and the corresponding strain of N. gonorrhoeae, and Dr. Terry Connell (University at Buffalo) kindly provided TLR2-knockout mice. This study was supported by a grant from the John R. Oishei Foundation, Buffalo, NY (to MWR) and grants AI074791 (to MWR), U19 AI31496 (to AEJ), and AR054389 and DE018822 (to SLG), from the National Institutes of Health. BF was supported by the University at Buffalo School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

The authors disclose no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Harrington LE, et al. Interleukin 17-producing CD4+ effector T cells develop via a lineage distinct from the T helper type 1 and 2 lineages. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1123–1132. doi: 10.1038/ni1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park H, et al. A distinct lineage of CD4 T cells regulates tissue inflammation by producing interleukin 17. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1133–1141. doi: 10.1038/ni1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kotake S, et al. IL-17 in synovial fluids from patients with rheumatoid arthritis is a potent stimulator of osteoclastogenesis. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:1345–1352. doi: 10.1172/JCI5703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Langrish CL, et al. IL-23 drives a pathogenic T cell population that induces autoimmune inflammation. J Exp Med. 2005;201:233–240. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Happel KI, et al. Divergent roles of IL-23 and IL-12 in host defense against Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Exp Med. 2005;202:761–769. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higgins SC, Jarnicki AG, Lavelle EC, Mills KH. TLR4 mediates vaccine-induced protective cellular immunity to Bordetella pertussis: role of IL-17-producing T cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:7980–7989. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.7980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khader SA, et al. IL-23 and IL-17 in the establishment of protective pulmonary CD4+ T cell responses after vaccination and during Mycobacterium tuberculosis challenge. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:369–377. doi: 10.1038/ni1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shibata K, Yamada H, Hara H, Kishihara K, Yoshikai Y. Resident Vδ1+ γδ T cells control early infiltration of neutrophils after Escherichia coli infection via IL-17 production. J Immunol. 2007;178:4466–4472. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ye P, et al. Requirement of interleukin 17 receptor signaling for lung CXC chemokine and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor expression, neutrophil recruitment, and host defense. J Exp Med. 2001;194:519–527. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.4.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu JJ, et al. An essential role for IL-17 in preventing pathogen-initiated bone destruction: recruitment of neutrophils to inflamed bone requires IL-17 receptor-dependent signals. Blood. 2007;109:3794–3802. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-010116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weaver CT, Harrington LE, Mangan PR, Gavrieli M, Murphy KM. Th17: an effector CD4 T cell lineage with regulatory T cell ties. Immunity. 2006;24:677–688. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Korn T, Bettelli E, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. IL-17 and Th17 Cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:485–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ouyang W, Kolls JK, Zheng Y. The biological functions of T helper 17 cell effector cytokines in inflammation. Immunity. 2008;28:454–467. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.LeibundGut-Landmann S, et al. Syk- and CARD9-dependent coupling of innate immunity to the induction of T helper cells that produce interleukin 17. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:630–638. doi: 10.1038/ni1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verreck FA, et al. Human IL-23-producing type 1 macrophages promote but IL-10-producing type 2 macrophages subvert immunity to (myco)bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4560–4565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400983101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schulz SM, et al. Protective immunity to systemic infection with attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis in the absence of IL-12 is associated with IL-23-dependent IL-22, but not IL-17. J Immunol. 2008;181:7891–7901. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.11.7891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prause O, Laan M, Lotvall J, Linden A. Pharmacological modulation of interleukin-17-induced GCP-2-, GRO-alpha- and interleukin-8 release in human bronchial epithelial cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;462:193–198. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01341-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruddy MJ, Shen F, Smith JB, Sharma A, Gaffen SL. Interleukin-17 regulates expression of the CXC chemokine LIX/CXCL5 in osteoblasts: implications for inflammation and neutrophil recruitment. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;76:135–144. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0204065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shen F, Ruddy MJ, Plamondon P, Gaffen SL. Cytokines link osteoblasts and inflammation: microarray analysis of interleukin-17- and TNF-α-induced genes in bone cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;77:388–399. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0904490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Witowski J, et al. IL-17 stimulates intraperitoneal neutrophil infiltration through the release of GRO α chemokine from mesothelial cells. J Immunol. 2000;165:5814–5821. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang W, Na L, Fidel PL, Schwarzenberger P. Requirement of interleukin-17A for systemic anti-Candida albicans host defense in mice. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:624–631. doi: 10.1086/422329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Conti HR, et al. Th17 cells and IL-17 receptor signaling are essential for mucosal host defense against oral candidiasis. J Exp Med. 2009;206:299–311. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liang SC, et al. Interleukin (IL)-22 and IL-17 are coexpressed by Th17 cells and cooperatively enhance expression of antimicrobial peptides. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2271–2279. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Global prevalence and incidence of selected curable sexually transmitted infections: Overview and estimates. World Health Organization; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Notifiable Diseases/Deaths in Selected Cities Weekly Information. MMWR. 2009;55:1396–1407. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noble RC, Kirk NM, Slagel WA, Vance BJ, Somes GW. Recidivism among patients with gonococcal infection presenting to a venereal disease clinic. Sex Transm Dis. 1977;4:39–43. doi: 10.1097/00007435-197704000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Edwards JL, Apicella MA. The molecular mechanisms used by Neisseria gonorrhoeae to initiate infection differ between men and women. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:965–981. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.4.965-981.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hedges SR, Sibley DA, Mayo MS, Hook EW, 3rd, Russell MW. Cytokine and antibody responses in women infected with Neisseria gonorrhoeae: effects of concomitant infections. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:742–751. doi: 10.1086/515372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fichorova RN, Desai PJ, Gibson FC, 3rd, Genco CA. Distinct proinflammatory host responses to Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection in immortalized human cervical and vaginal epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 2001;69:5840–5848. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.9.5840-5848.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naumann M, Wessler S, Bartsch C, Wieland B, Meyer TF. Neisseria gonorrhoeae epithelial cell interaction leads to the activation of the transcription factors nuclear factor κB and activator protein 1 and the induction of inflammatory cytokines. J Exp Med. 1997;186:247–258. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.2.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramsey KH, et al. Inflammatory cytokines produced in response to experimental human gonorrhea. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:186–191. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.1.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simpson SD, Ho Y, Rice PA, Wetzler LM. T lymphocyte response to Neisseria gonorrhoeae porin in individuals with mucosal gonococcal infections. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:762–773. doi: 10.1086/314969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jerse AE, et al. Multiple gonococcal opacity proteins are expressed during experimental urethral infection in the male. J Exp Med. 1994;179:911–920. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.3.911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jerse AE. Experimental gonococcal genital tract infection and opacity protein expression in estradiol-treated mice. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5699–5708. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.5699-5708.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Packiam M, Veit SJ, Anderson DJ, Ingalls RR, Jerse AE. Mouse strain-dependent differences in susceptibility to Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection and induction of innate immune responses. Infect Immun. 2009 doi: 10.1128/iai.00711-09. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kobayashi Y. The role of chemokines in neutrophil biology. Front Biosci. 2008;13:2400–2407. doi: 10.2741/2853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Russell MW, Hook EW. Gonorrhea. In: Barrett ADT, Stanberry LR, editors. Vaccines for Biodefense and Emerging and Neglected Diseases. Academic Press; London: 2009. pp. 963–981. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jerse AE, et al. Growth of Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the female mouse genital tract does not require the gonococcal transferrin or hemoglobin receptors and may be enhanced by commensal lactobacilli. Infect Immun. 2002;70:2549–2558. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.5.2549-2558.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Song W, et al. Local and humoral immune responses against primary and repeat Neisseria gonorrhoeae genital tract infections of 17β-estradiol-treated mice. Vaccine. 2008;26:5741–5751. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Criss AK, Katz BZ, Seifert HS. Resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to non-oxidative killing by adherent human polymorphonuclear leucocytes. Cell Microbiol. 2009;11:1074–1087. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01308.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu H, Soler-Garcia AA, Jerse AE. A strain-specific catalase mutation and mutation of the metal-binding transporter gene mntC attenuate Neisseria gonorrhoeae in vivo but not by increasing susceptibility to oxidative killing by phagocytes. Infect Immun. 2009;77:1091–1102. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00825-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simons MP, Nauseef WM, Apicella MA. Interactions of Neisseria gonorrhoeae with adherent polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Infect Immun. 2005;73:1971–1977. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.4.1971-1977.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Casey SG, Veale DR, Smith H. Demonstration of intracellular growth of gonococci in human phagocytes using spectinomycin to kill extracellular organisms. J Gen Microbiol. 1979;113:395–398. doi: 10.1099/00221287-113-2-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Plummer FA, et al. Epidemiologic evidence for the development of serovar-specific immunity after gonococcal infection. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:1472–1476. doi: 10.1172/JCI114040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schmidt KA, et al. Experimental gonococcal urethritis and reinfection with homologous gonococci in male volunteers. Sex Transm Dis. 2001;28:555–564. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200110000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Price GA, Hobbs MM, Cornelissen CN. Immunogenicity of gonococcal transferrin binding proteins during natural infections. Infect Immun. 2004;72:277–283. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.1.277-283.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hedges SR, Mayo MS, Mestecky J, Hook EW, 3rd, Russell MW. Limited local and systemic antibody responses to Neisseria gonorrhoeae during uncomplicated genital infections. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3937–3946. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.8.3937-3946.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ram S, et al. Binding of C4b-binding protein to porin: a molecular mechanism of serum resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Exp Med. 2001;193:281–295. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.3.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith H, Parsons NJ, Cole JA. Sialylation of neisserial lipopolysaccharide: a major influence on pathogenicity. Microb Pathog. 1995;19:365–377. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1995.0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rice PA, Vayo HE, Tam MR, Blake MS. Immunoglobulin G antibodies directed against protein III block killing of serum-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae by immune serum. J Exp Med. 1986;164:1735–1748. doi: 10.1084/jem.164.5.1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Long F, Rouquette-Loughlin C, Shafer WM, Yu EW. Functional cloning and characterization of the multidrug efflux pumps NorM from Neisseria gonorrhoeae and YdhE from Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:3052–3060. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00475-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nassif X, So M. Interaction of pathogenic neisseriae with nonphagocytic cells. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:376–388. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.3.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Awasthi AKV. IL-17A directly inhibits TH1 cells and thereby suppresses development of intestinal inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:568–570. doi: 10.1038/ni0609-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Imarai M, et al. Regulatory T cells are locally induced during intravaginal infection of mice with Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infect Immun. 2008;76:5456–5465. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00552-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cohen MS, et al. Human experimentation with Neisseria gonorrhoeae: rationale, methods, and implications for the biology of infection and vaccine development. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:532–537. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.3.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]