Fertility levels in most developed countries are well below the replacement level and portend substantial population declines if sustained. While a tempo adjustment for postponed fertility raises these low rates and narrows differentials among developed countries, fertility levels for most countries remain substantially below replacement even when adjusted for postponement (Bongaarts 2002; Bongaarts and Feeney 1998; Goldstein, Sobotka, and Jasilioniene 2009). This remaining country-level variation in fertility cannot be explained by parallel variations in the number of children women intend to have, given that intended family size is generally close to two children in most developed countries (Bongaarts 2001, 2002; Hagewen and Morgan 2005). Thus, an apparent inability to reach fertility intentions plays a significant role in contemporary low fertility. What are the factors involved in the process, and what leads women to consistently underachieve their fertility intentions?

This article uses the most detailed data ever collected on fertility intentions and subsequent fertility behavior: a large nationally representative sample of US men and women born 1957–64 who were asked their fertility intentions 16 times between 1979 and 2006. Among low-fertility countries, the United States stands out in having relatively high fertility, approximating the level required for population replacement. (The United States had an un-adjusted TFR of 2.1 in 2007.) Further, in the aggregate, US fertility intentions closely approximate observed period fertility (Bongaarts 2002; Hagewen and Morgan 2005); and for the cohorts we examine here, intentions at age 24 only modestly overstate these women’s completed cohort fertility of 1.97. How are US women, in the aggregate, able to meet their intentions?

A first proposed explanation assumes a close congruence between individuals’ intentions and behavior; that is, it posits that women and men in the United States accurately anticipate how many children they will have. As a result of such hypothetically accurate estimates, we would expect to observe aggregate congruence as well. A second possibility is that many women misestimate their own fertility, but that these individual-level errors tend to be offsetting, thus still result in aggregate correspondence. Whatever the case may be, the US experience should provide insight into the circumstances that either allow persons to realize their intentions (more often than in other countries) or produce a “balance” in errors (errors that cumulate differently in other countries to produce much lower fertility).

Intentions, by definition, imply foresight and a weighing, perhaps implicitly, of alternative choices. However, we also view choice, in this case fertility intentions, as both highly contingent and highly constrained. Fertility intentions are highly contingent because they are imbedded within an unfolding life course that intersects with historical time (i.e., period factors). Intentions and attempts to realize them are also highly constrained because of subfecundity or infecundity, structural obstacles (e.g., difficulty finding a spouse or full employment), and social norms. Linking this framework to gender, we acknowledge that, at the biological level, women’s fecundity declines more rapidly with age than does men’s, and that, at the social level, the tension between childbearing/parenting and other activities is more intense for women than for men. Therefore, contrary to much of the existing literature on intentions, we focus on the congruence of men’s and women’s intentions with their behavior. The hypotheses we develop about women’s and men’s fertility intentions and subsequent behavior emerge from joint consideration of life-course contingencies and structural constraints.

Our article revisits some arguments offered by Quesnel-Vallée and Morgan (2003; hereafter QVM), and we assess them using additional data from the 1979 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY79). QVM used data only for the older half of the NLSY79 respondents, those who had reached the end of the childbearing years when they carried out their analyses (i.e., were over 40 years of age at the 2000 interview). Our article has several goals. Using the full NLSY79 sample, we 1) examine the patterns of disparity between intentions and behavior—for simplicity termed “errors”—by sex over nearly two decades and 2) assess, with bivariate and multivariate analyses, the effect of selected life-course contingencies and structural constraints on the level of individual mis-estimation.1 In addition, we 3) present analyses over longer and shorter portions of the life course and 4) introduce additional explanatory variables, namely unanticipated life-course events (marital instability and mistimed and unwanted births) that have powerful effects on the likelihood of missing the fertility target.

Missing the target?

The general consensus is that intentions do not provide reliable predictions of individual or aggregate fertility (Morgan 2001). Yet, such a fact does not make intentions irrelevant; instead, these discrepancies between intended numbers of children and observed fertility provide opportunities to study constraints on meeting intentions (e.g., Miller and Pasta 1995).

As in QVM, we build on Bongaarts’s (2001) conceptual model that focuses on the interaction between intentions and salient proximate variables:

The Bongaarts (2001) formalization is period based and thus includes a tempo component not needed in our focus on cohort fertility. Thus, we posit that final parity (FP) equals intended parity (IP) mitigated by a set of factors that reflect impediments to achieving intended parity. Of these factors, fecundity impairments (F) lower achieved fertility net of intentions; on the other hand, unwanted births (U) increase it. Subsequent factors represent intermediate goals, namely finding a marriage partner or otherwise establishing a long-term relationship (M). Finally, the last factor signals that fertility goals compete with other goals and aspirations (C), or that opportunity costs matter. At a young age (in the early 20s), not all of these mitigating factors can be accurately anticipated and are thus not factored into intended parity. For lack of data, we do not aim here for a full operationalization of this model; rather we explore a subset of hypotheses suggested by it.2

Intended family size

A sociological analysis of life-course trajectories focuses on macro-level factors that influence these trajectories and their stability. Very simply, some structures facilitate meeting intentions and expectations, while others impede their realization. A first constraint can be found in the concept of normative family size. NLSY79 data show that only about 5 percent of 20-year-olds intend childlessness and roughly the same percentage intend large families, that is, more than four children (see QVM). This nearly universal desire to be a parent reflects both the salience of parenthood in gender identities and the impact of strong norms against childlessness (see Blake 1979). Additional “upward” normative pressure is applied by concerns about the psychological consequences of raising a singleton (see Blake 1981). At the opposite extreme, viewing four children, and even three, as a “large family” provides “downward” normative pressure. These negative views and informal sanctions spring from the belief that large numbers of children dilute the resources necessary for maintaining an adequate standard of living for oneself and securing the full realization of each child’s potential, and possibly also from concerns that large families contribute to overpopulation, resource depletion, and environmental deterioration. Combined, these forces produce a strong normative ideal of the “two-child” family. Because these forces operate continually and powerfully (as the cohorts age), we expect that behavior will correspond to intentions most frequently when respondents state normative intentions.3

In short, we expect that respondents who express an intention for fewer than two children will tend to have more children than intended, while those who express an intention for more than two children will tend to have fewer than intended.

Having more children than intended: The effects of C and U

A number of factors can lead to having more births than intended. First, lessened competition (C) may produce a “veer toward domesticity” (Gerson 1985). We envision competition as a process that unfolds over the life course and sorts individuals into environments that either encourage or constrain childbearing (Johnson-Hanks et al. 2006). For example, a woman with less than a high school diploma may be more likely to be employed in a sex-segregated work-place, which may be more flexible regarding exit and re-entrance. Women in these workplaces are more likely to interact with other female coworkers with children. Also, less-educated women may interact more frequently with other women who are relatives. In short, these young women may be surrounded by other women who have found fulfillment in childbearing—fulfillment that their workplace did not offer. These pronatalist contexts lower the normative, emotional, and monetary costs to childbearing, and women may have more children than they intended (in their early 20s) or at least achieve their fertility aspirations.

In contrast, men with low education do not generally end up in female-dominated occupations surrounded by women with children. Additionally, because men do not shoulder the major share of childrearing responsibility, flexible work or even periods of unemployment would not increase the ease of childrearing. Therefore, men with low education would not be expected to overachieve their desired family size (as women with low education would). These men may actually be more likely to underachieve their intended fertility because they may experience difficulties in finding a partner with whom to raise children.

An additional factor that can lead to more births than expected is contraceptive failure and resulting unplanned pregnancies. Some of these pregnancies will produce what demographers define as unwanted births (U), that is, births to women who, prior to the pregnancy, wanted no additional births. Because at least 10 percent of US births in the early 1990s were reported by mothers as unwanted (Abma et al. 1997), this factor clearly increases fertility. The report of an unwanted birth would logically imply having more children than intended, if the number of intended births was fixed over time. Other unplanned births are wanted but are “timing failures” (or mistimed births)— persons had them sooner than intended. These mistimed births should also reduce the likelihood of having fewer children than intended. Mistimed births are not (by definition) postponed; as discussed below, postponement is a major cause of having fewer children than intended.

Having fewer children than intended: The effects of F,M, and C

Fecundity impairments (F) can cause persons to have fewer children than intended. A relatively small proportion of women are unable to have children at young ages, but this proportion is increased by disease processes that cumulate with age and by age-related declines in fecundity, especially after age 35. There is little reason to expect that individuals would account for this risk when forming their fertility intentions, and even if they tried to do so, their ability to anticipate their subfecundity would most likely be poor. As a telling example, Hewlett (2002) interviewed professional women who clearly wanted children and found that childbearing was difficult or impossible for them past the age of 40. While we have no direct measure of fecundity, one can think of continued postponement as the opposite of having births earlier than intended, and with the opposite effect—forgone fertility (i.e., under-achieving intentions). Postponement may be especially consequential to women, as it may cause them to underestimate age-related fecundity declines and normative and structural obstacles to childbearing at older ages, and thus to misjudge their own risk of achieving fertility lower than intended. It is not surprising, then, that some women eventually decide to have no children, or even find themselves “forced” into childlessness, as was the case for some of the women interviewed by Hewlett (2002). In addition, this description fits with the well-known finding that most childless women intended to have children at younger ages and with the empirical evidence that strongly suggests that childlessness most often results from a series of decisions to postpone childbearing (see Rindfuss et al. 1988).

For many individuals, finding a suitable parenthood partner (M) is a precondition for childbearing. Yet, such preconditions are not acknowledged in the simple questions that are typically used to measure fertility intentions, such as: “How many children do you intend to have?” An answer of “two,” for instance, may assume that the respondent will marry or remain married. Consequently, one explanation for an aggregate underachievement of fertility relative to intentions can be found in a decline in marriage rates and/or an increase in marital disruption. In support of this explanation, O’Connell and Rogers (1983) showed that women who married—and remained married—achieved their fertility intentions even during the baby bust of the 1970s. Thus during this period an aggregate underachievement of fertility (based on intentions data) might be attributable to the substantial under-achievement among the late married, unmarried, or divorced, compounded by the increasing proportion of individuals in these categories.

Finally, and importantly, competition (C) can powerfully influence whether individuals have fewer children than initially intended. Again, certain environments can constrain childbearing. For example, a highly educated woman may be likely to work in a traditionally male career that has long hours and demanding requirements but provides income, status, prestige, self-fulfillment, and other benefits. These types of environments discourage childbearing and encourage postponement of family-related activities. Many women involved in these careers may use postponement as a strategy to deal with a demanding but emotionally and financially rewarding career. This strategy then creates a template for other young, highly educated women entering similar careers. Continued postponement can lead to further workplace demands and to increases in the costs of childbearing, prompting women to have fewer children than they desire.

Highly educated men do not face the same magnitude of challenges when trying to deal with a demanding career and children because they traditionally have fewer childrearing responsibilities than women. The structural barriers and normative environment do not discourage childbearing for highly educated men as much as for highly educated women, if at all. Additionally, even if postponement were a factor for highly educated men, it would not be as consequential to their fertility goals because men’s fertility is less age-constrained than women’s.

An example of how normative environments can constrain childbearing is found in the context of post-secondary education. Even though women enrolled in higher education may be of childbearing age, many wait to have children. We believe that what accounts for this are the demands of higher education, the normative environment, and the goals of having a stable career and providing for the children they eventually have. The normative environment of schooling may be of particular importance; for example, mothers enrolled in college or graduate school are seen as oddities or as potentially unsuccessful students. Therefore, women will be hesitant to have children or have additional children. For these reasons, women enrolled at age 24 will be more likely to underachieve their fertility intentions declared at that age. On the other hand, this process will be weaker for men for the aforementioned reasons.

Data

We use data from the 1979 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth to assess the predictive validity of fertility intentions and its variation. The NLSY79 is an ongoing longitudinal panel survey of a national probability sample of American youth, whether civilian or military, aged 14 to 21 years old in 1978 (Zagorsky and White 1999). The NLSY79 began with a sample of 12,686, but several subsamples were dropped in 1990 or before. Therefore in 2006, 9,964 respondents were available for re-interview. The total sample size for our research is 7,367, or 74 percent of the possible respondents.4

Respondents were surveyed annually until 1994, after which the survey was carried out biennially. This survey, sponsored by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, was designed principally to gather longitudinal information on the labor force experiences of young American men and women. In addition, beginning in 1982, supplementary funding from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) allowed for the collection of expanded fertility information, including questions about fertility intentions. Respondents were asked about their fertility intentions in 1979, 1982–86, and biennially until the latest wave in 2006. Thus, NLSY respondents were asked their fertility intentions a total of 16 times over a 27-year period until respondents were aged 41–50.

This survey presents a remarkable opportunity to study the life-course and fertility history of a representative sample of Americans born in the late 1950s and early 1960s and residing in the United States when the survey began. To our knowledge, no other survey provides such rich data on the parallel evolution of fertility intentions and reproductive histories from the beginning until the end of the respondents’ reproductive years (by 2006, the youngest respondents were 41 years of age).

Descriptive results

We sought to study young adults who were old enough at baseline for their fertility intentions to be relatively realistic (see Walker 2001). Yet, we also wanted to include them early enough to observe the reactions to competing opportunities in young adulthood. Finally, we wanted to follow these individuals until the end of their reproductive period to determine whether they realized their intentions. These goals require us to define and measure two core concepts: intended parity and achieved parity.

Intended parity

The NLSY asked respondents about their fertility intentions 16 times with the following question: “How many (more) children do you expect to have?” This questions was asked regardless of current parity (i.e., the number of children previously born). These data allow for measurement of intended parity, that is, fertility intentions at a range of ages: intended parity equals achieved parity at age x plus additional children intended at age x.

Achieved parity

Achieved parity is simply the number of children ever born at a given age or by a particular date. Achieved parity in 2006, when the youngest respondents were age 41, is taken as a measure of completed or achieved parity.

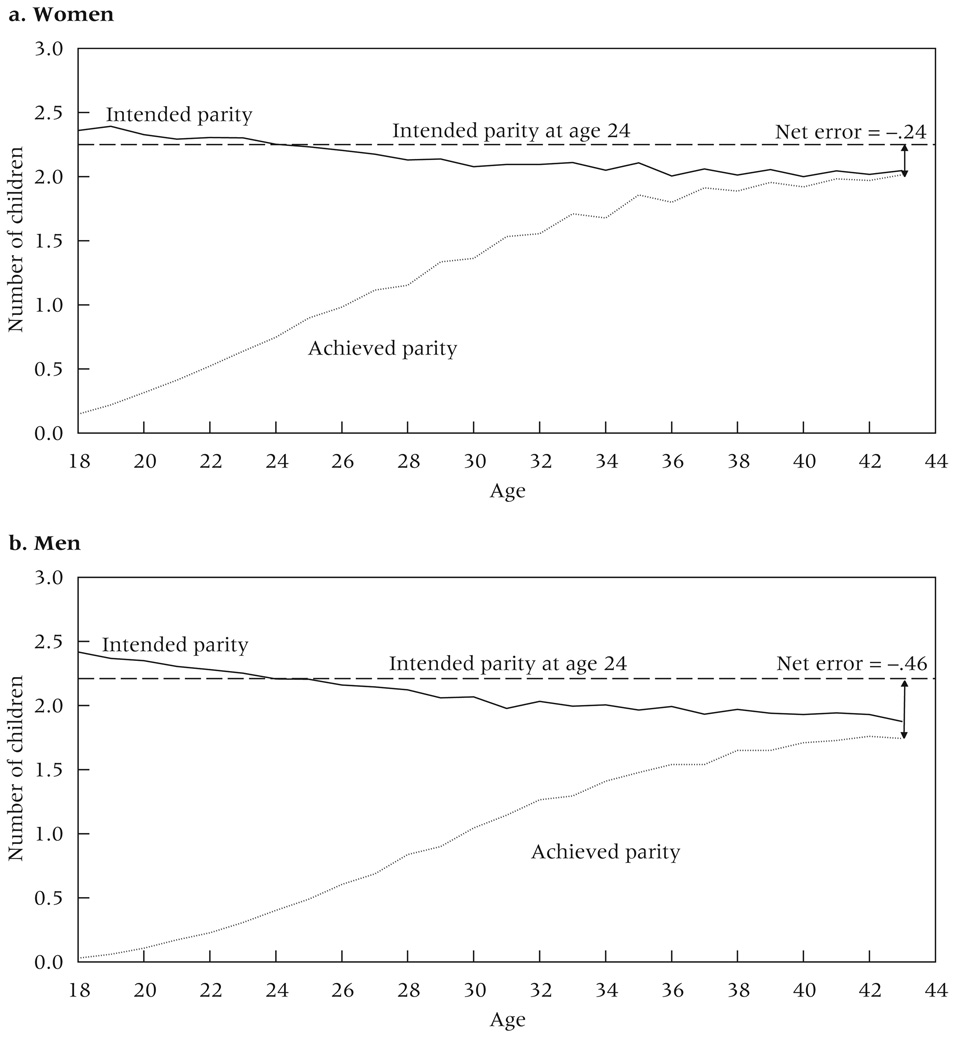

Using respondents who provided reports at exact ages 18–43, Figure 1 shows estimates of intended and achieved parity. Mean achieved parity increases across age for both women (1a) and men (1b) as the number of their children increases. In contrast, intended parity is relatively stable across age but shows a downward drift. Interestingly, the greatest decline is at younger ages (before age 30); one could have expected that declines would dominate at older ages when the biological and social constraints to reaching fertility goals become more obvious.

FIGURE 1. Mean intended parity and mean achieved parity by age, birth cohorts 1957–1964.

NOTE: All analyses weighted with 2006 sampling weights.

At the end of the reproductive years (not yet achieved by men), intended parity and completed parity must converge. The level at which they converge can vary and is one of our primary variables of interest. Figure 1 shows the predictive validity of intended parity over the age range 24–43. The horizontal dashed line indicates intended parity at age 24 (as explained below); the vertical difference between this line and completed fertility at a given age provides the aggregate estimate of predictive validity. The mean or net error for these cohorts at age 43 is –.24 and –.46 births for women and men respectively). Clearly, the younger the age of respondents, the greater the mean (or net) error.

This way of representing the data does not allow one to observe the full extent to which individuals miss their target number—the gross error. Because not all respondents were interviewed at exactly age 24, we created a new variable, intended parity at approximately age 24. Specifically, intentions data for age 24 were created by reviewing all possible waves of the NLSY in which individuals could have been near age 24. If respondents were 24 years old in a certain wave, then their intentions data (along with other important explanatory variables) were extracted. However, if an individual was not interviewed at exactly age 24, then we looked to age 25 for the same data. If age 25 was not available, age 23 was used to create the intentions variable. We continued this process until we searched at seven different ages. This procedure allows us to include all respondents (even if intentions data are missing in one wave) but centers the intentions data on age 24. Our data are thus centered on age 24, with the vast majority of individuals responding at ages 23 to 25 (nearly 99 percent of the sample—see Table 1 for a distribution of ages used to create this variable).5 We also created parallel variables centered on ages 19, 30, and 35.

TABLE 1.

Distribution of age of respondents in 1982–90 in our measurement of fertility intentions at age 24 (percent)

| Age | Women | Men |

|---|---|---|

| 21 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| 22 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| 23 | 6.5 | 6.5 |

| 24 | 71.9 | 71.0 |

| 25 | 20.4 | 21.1 |

| 26 | 0.6 | 0.7 |

| 27 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Total | 100 | 100 |

| Number | 3,783 | 3,584 |

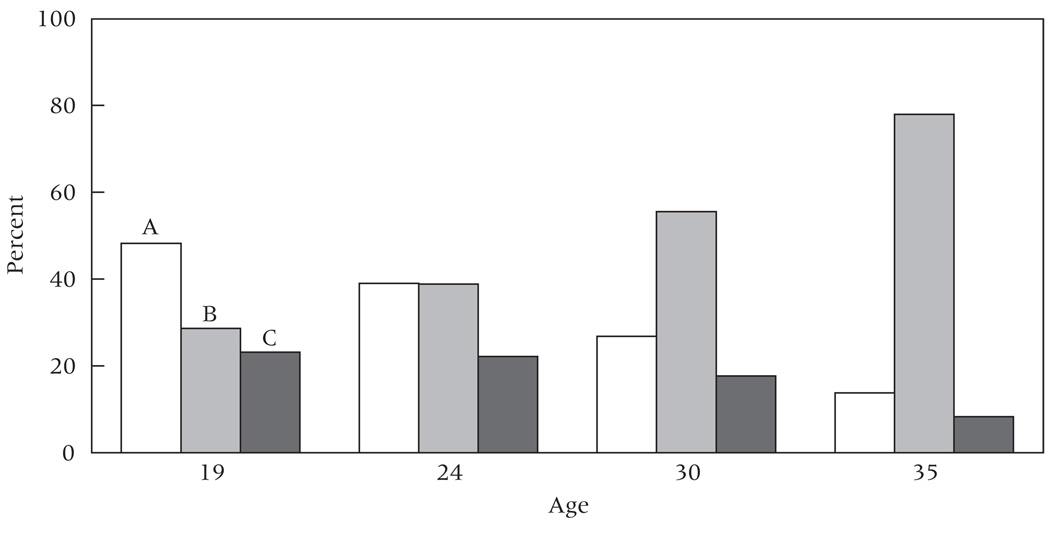

We use these four variables in Figure 2 to show the proportion of respondents who have underachieved, achieved, or overachieved their intended fertility at age 41–50—hereafter age 45. At age 19 the modal category is the underachieved (48.2 percent of respondents), that is, most respondents end up with fewer children than they intended at age 19. About half of respondents either achieved or overachieved their intentions at age 19, with 28.5 percent achieving these intentions and 23.3 percent overachieving them. Thus at age 19, missing the target is far more likely (48.2%+23.3%= 71.5%) than achieving it (28.5 percent). At older ages respondents have more life-course experience (including with childbearing), and they are projecting behavior over a shorter time period. Over the 24–45 period, roughly equal proportions (approximately 39 percent) have achieved or underachieved their intentions at age 24, but still the sum of those missing the target (with completed fertility either too low or too high amounting to 61.3 percent) substantially exceeds the number achieving their intentions (38.7 percent). As one moves to older ages (30 and 35 years, and shorter periods of prediction), the proportion achieving their intentions increases sharply. Finally, at each age shown in Figure 2, respondents are more likely to underachieve than to overachieve their fertility intentions. Our subsequent analyses focus on the predictive validity at age 24.6

FIGURE 2. Percent of respondents who have underachieved (A), achieved (B), and overachieved (C) fertility intentions at different ages.

NOTE: All analyses weighted with 2006 sampling weights.

Table 2 provides additional detail about the NLSY79 respondents at age 24. The full sample is 7,367 (3,783 women and 3,584 and men). The total number of births to these women and men is also shown. Panel A shows the percentage of women who have underachieved, achieved, or overachieved intentions (percentages that correspond to the bars in Figure 2 for this age, as well as the number of respondents on which they are based). Because of the relationship between family size of mothers and family size of children (see Preston 1976), there are more women who achieved their fertility intentions (1,642) and underachieved those intentions (1,320), but more births are produced by overachievers (821 women, 21.7 percent of all women, had 1,873 births or 40.8 percent of all births occurring after age 24).

TABLE 2.

Inconsistency between achieved parity in 2006 by birth cohorts 1957–1964 and intended parity by these cohorts at age 24, NLSY79 data

| Women |

Men |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Percent | N | Percent | |

| Panel A: Number and percent who underachieved, achieved, and overachieved and intended parity | ||||

| Underachieved | 1,320 | 34.9 | 1,534 | 42.8 |

| Achieved intentions | 1,642 | 43.4 | 1,226 | 34.2 |

| Overachieved | 821 | 21.7 | 824 | 23.0 |

| Total achieved | 3,783 | 100.0 | 3,584 | 100.0 |

| Births before age 24 | 2,875 | 38.5 | 1,460 | 23.0 |

| Births after age 24 | 4,585 | 61.5 | 4,891 | 77.0 |

| Total | 7,459 | 100.0 | 6,351 | 100.0 |

| Panel B: Gross and net errors | ||||

| Total births after age 24a | 4,585 | 100.0 | 4,891 | 100.0 |

| To underachievers | 957 | 20.9 | 1,128 | 23.1 |

| To achievers | 1,755 | 38.3 | 1,657 | 33.9 |

| To overachievers | 1,873 | 40.8 | 2,106 | 43.1 |

| Gross errorb | 3,297 | 100.0 | 3,960 | 100.0 |

| Due to underachievers | 2,129 | 64.6 | 2,701 | 68.2 |

| Due to overachievers | 1,168 | 35.4 | 1,259 | 31.8 |

| Net errorc | −960 | −1,442 | ||

| Women | Men | |||

| Panel C: Individual leveld | ||||

| Average intended parity | 2.22 | 2.17 | ||

| Average achieved parity | 1.97* | 1.77* | ||

| Gross error | 0.87* | 1.10* | ||

| Net error | −0.25* | −0.40* | ||

| Mean error for underachievers | −1.61* | −1.76* | ||

| Mean error for overachievers | 1.42* | 1.53* | ||

Births between age 24 and 2006 interview.

Sum of the absolute value of the difference between achieved parity in 2006 and intended parity at age 24.

Sum of the signed value of the difference between achieved parity in 2006 and intended parity at age 24.

Asterisk indicates significant differences by sex, as measured by two-tailed t-tests (p ≤ 0.05 level).

NOTE: All analyses weighted with 2006 sampling weights.

Table 2 introduces a second way to assess the gross error, by summing the absolute value of the difference between completed parity in 2006 and intended parity at age 24. Gross errors show how large is the summed error (across all persons) between fertility intentions and completed fertility and how far individuals on average have departed from their intended fertility in absolute terms. A gross error of one indicates that a respondent has had either one more or one less birth than intended at age 24. NLSY79 women accumulated 3,297 gross errors, most of them (64.6 percent) due to under-achievers. The imbalance in underachievers and overachievers is the net error (−960 births).

Panel C in Table 2 shows the mean errors per individual: at age 24 women and men intended 2.22 and 2.17 births, and the net error of this expectation at age 45 was −.25 and −.40 births for women and men, respectively. The average gross error per women (3,297/3,783) is close to one birth per woman (.87). For men the corresponding error (3,960/3,584) is over one birth (1.10), significantly greater than for women.

Individual-level errors by socio-demographic characteristics

We now examine whether respondents’ completed fertility differed from their age 24 intentions. Table 3 shows, for women and men separately, the cross-classification of 2006 achieved parity by age 24 intentions.7 A strong association is apparent between intent and outcome: for women, at every intended parity (0 to 5+) the modal outcome equals the intended parity. For men, parity two is the modal outcome if the respondent intends two or more children. Rather than examine this level of detail in subsequent analyses, we have used these data to identify a three-category dependent variable: completed fertility underachieved, achieved, or overachieved age 24 intentions.

TABLE 3.

Achieved parity in 2006 by intended parity at age 24, by sex

| Women |

Men |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Achieved parity 2006 |

Intended parity at age 24 |

Achieved parity 2006 |

Intended parity at age 24 |

||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5+ | Total | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5+ | Total | ||

| Panel 1: Weighted counts | |||||||||||||||

| 0 | 138 | 82 | 290 | 87 | 32 | 0 | 629 | 0 | 162 | 64 | 422 | 143 | 56 | 0 | 847 |

| 1 | 41 | 165 | 306 | 75 | 30 | 1 | 618 | 1 | 62 | 111 | 303 | 102 | 30 | 4 | 611 |

| 2 | 27 | 122 | 904 | 242 | 70 | 9 | 1,374 | 2 | 48 | 82 | 723 | 232 | 91 | 2 | 1,178 |

| 3 | 14 | 41 | 277 | 340 | 61 | 15 | 748 | 3 | 13 | 27 | 301 | 169 | 57 | 15 | 582 |

| 4 | 0 | 13 | 77 | 100 | 84 | 18 | 292 | 4 | 10 | 17 | 93 | 64 | 57 | 13 | 254 |

| 5+ | 0 | 2 | 24 | 37 | 40 | 19 | 122 | 5+ | 1 | 5 | 28 | 42 | 31 | 5 | 111 |

| Total | 220 | 425 | 1,878 | 881 | 317 | 62 | 3,783 | Total | 296 | 305 | 1,870 | 752 | 322 | 40 | 3,584 |

| Panel 2: Percentage distribution | |||||||||||||||

| 0 | 62.7 | 19.3 | 15.4 | 9.9 | 10.1 | 0.0 | 16.6 | 0 | 54.7 | 21.0 | 22.6 | 19.0 | 17.4 | 0.0 | 23.6 |

| 1 | 18.7 | 38.8 | 16.3 | 8.5 | 9.5 | 1.6 | 16.3 | 1 | 20.9 | 36.2 | 16.2 | 13.6 | 9.3 | 10.0 | 17.1 |

| 2 | 12.3 | 28.7 | 48.1 | 27.5 | 22.1 | 14.5 | 36.3 | 2 | 16.2 | 26.9 | 38.7 | 30.9 | 28.3 | 5.5 | 32.9 |

| 3 | 6.4 | 9.7 | 14.7 | 38.6 | 19.2 | 24.1 | 19.8 | 3 | 4.4 | 8.8 | 16.1 | 22.5 | 17.7 | 37.5 | 16.2 |

| 4 | 0.0 | 3.1 | 4.1 | 11.3 | 26.6 | 28.9 | 7.7 | 4 | 3.4 | 5.6 | 5.0 | 8.5 | 17.7 | 34.1 | 7.1 |

| 5+ | 0.0 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 4.2 | 12.6 | 30.8 | 3.2 | 5+ | 0.4 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 5.6 | 9.5 | 12.9 | 3.1 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

NOTE: All analyses weighted with 2006 sampling weights.

Specifically, we look at the association between intentions at age 24 and a number of socio-demographic characteristics that reflect aspects of the life course or structural constraints, namely race, sex, age, enrollment in school and education near age 24, age at first birth, and marital status. We also include two measures of events occurring between ages 24 and 2006 (i.e., age 45): marital disruption and mistimed and unwanted births.

Tables 4 and 5 show variables used in the multivariate analysis. The columns show key statistics on net and gross errors (from Table 2) for each specific subgroup along with the sample distribution on this variable. These statistics indicate that these errors are associated with all of these variables. To avoid redundancy in the exposition of results, we discuss bivariate analyses in parallel with the multivariate results below.

TABLE 4.

Gross and net errors between age 24 and 2006 interview by selected characteristics, birth cohorts 1957–1964, NLSY79 data

| Women |

Men |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Achieved paritya |

Gross errorb |

Net errorc |

Fertility in 2006 |

N | Achieved paritya |

Gross errorb |

Net errorc |

Fertility in 2006 |

N | |

| Panel A: Race | ||||||||||

| White | 0.68 | 0.85 | −0.28 | 1.93 | 2,390 | 0.36 | 1.07 | −0.42 | 1.72 | 2,294 |

| Black | 1.17 | 0.97 | −0.10 | 2.18 | 1,173 | 0.69 | 1.29 | −0.30 | 2.04 | 1,110 |

| Other | 0.91 | 0.95 | −0.26 | 2.10 | 220 | 0.54 | 1.32 | −0.39 | 2.05 | 180 |

| Panel B: Education | ||||||||||

| Education at 24 | ||||||||||

| Less than high school | 1.70 | 0.74 | 0.09 | 2.55 | 591 | 0.79 | 1.14 | −0.07 | 1.98 | 664 |

| High school graduate | 0.95 | 0.81 | −0.15 | 2.05 | 1,688 | 0.51 | 1.09 | −0.33 | 1.80 | 1,664 |

| Some college | 0.46 | 0.97 | −0.40 | 1.76 | 909 | 0.26 | 1.15 | −0.66 | 1.58 | 731 |

| College and above | 0.09 | 0.98 | −0.54 | 1.67 | 595 | 0.06 | 1.07 | −0.54 | 1.76 | 525 |

| Enrolled at 24 | ||||||||||

| Not enrolled | 0.82 | 0.84 | −0.21 | 2.02 | 3,400 | 0.45 | 1.10 | −0.39 | 1.78 | 3,189 |

| Enrolled | 0.30 | 1.16 | −0.62 | 1.59 | 383 | 0.14 | 1.12 | −0.49 | 1.69 | 395 |

| Panel C: Children intended | ||||||||||

| Less than 2 | 0.34 | 0.73 | 0.48 | 1.14 | 661 | 0.26 | 0.86 | 0.64 | 1.15 | 595 |

| 2 | 0.62 | 0.74 | −0.20 | 1.80 | 1,828 | 0.35 | 0.92 | −0.30 | 1.70 | 1,748 |

| More than 2 | 1.18 | 1.13 | −0.71 | 2.65 | 1,294 | 0.59 | 1.54 | −1.14 | 2.23 | 1,241 |

| Panel D: Age at first birth | ||||||||||

| <20 | 2.03 | 0.62 | 0.24 | 2.83 | 1,037 | 1.80 | 1.05 | 0.57 | 3.12 | 394 |

| 20–24 | 1.23 | 0.69 | 0.13 | 2.47 | 983 | 1.14 | 0.86 | 0.23 | 2.55 | 947 |

| 25–29 | 0.03 | 0.76 | −0.07 | 2.19 | 658 | 0.03 | 0.85 | 0.06 | 2.27 | 792 |

| 30–34 | 0 | 0.79 | −0.25 | 1.91 | 370 | 0 | 0.86 | −0.29 | 1.94 | 448 |

| 35–39 | 0 | 0.85 | −0.34 | 1.51 | 121 | 0 | 0.86 | −0.45 | 1.76 | 163 |

| 40+ | 0 | 1.06 | −0.90 | 1.07 | 25 | 0 | 0.83 | −0.72 | 1.45 | 51 |

| Childless | 0 | 1.67 | −1.67 | 0 | 589 | 0 | 1.84 | −1.84 | 0 | 789 |

| Panel E: Married at 24 | ||||||||||

| No | 0.53 | 1.04 | −0.41 | 1.69 | 2,155 | 0.19 | 1.28 | −0.67 | 1.48 | 2,405 |

| Yes | 1.01 | 0.69 | −0.08 | 2.29 | 1,628 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.07 | 2.29 | 1,179 |

Achieved parity at age 24.

Sum of the absolute value of the difference between achieved parity in 2006 and intended parity at age 24

Sum of the signed value of the difference between achieved parity in 2006 and intended parity at age 24

NOTE: All analyses weighted with 2006 sampling weights.

TABLE 5.

Gross and net errors between age 24 and the 2006 interview by events occurring after age 24, birth cohorts 1957–1964, NLSY79 data

| Women |

Men |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Achieved paritya |

Gross errorb |

Net errorc |

Fertility in 2006 |

N | Achieved paritya |

Gross errorb |

Net errorc |

Fertility in 2006 |

N | |

| Marital transitions | ||||||||||

| Never married | 0.55 | 1.40 | −0.88 | 1.10 | 555 | 0.20 | 1.61 | −1.28 | 0.63 | 694 |

| Married | 0.59 | 0.79 | −0.19 | 2.11 | 1,621 | 0.35 | 0.93 | −0.29 | 2.00 | 1,574 |

| Divorced | 0.90 | 0.92 | −0.34 | 1.82 | 630 | 0.41 | 1.29 | −0.68 | 1.57 | 477 |

| Remarried | 0.97 | 0.81 | −0.14 | 2.08 | 614 | 0.56 | 1.06 | 0.02 | 2.08 | 547 |

| More than 3 transitions | 1.15 | 0.77 | −0.03 | 2.22 | 363 | 0.82 | 1.01 | 0.13 | 2.19 | 292 |

| Unplanned births | ||||||||||

| Unwanted births | ||||||||||

| No unwanted birth after 24 | 0.72 | 0.84 | −0.35 | 1.87 | 3,439 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Unwanted birth after 24 | 1.22 | 1.24 | 0.96 | 3.24 | 344 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Mistimed births | ||||||||||

| No mistimed birth after 24 | 0.75 | 0.85 | −0.42 | 1.76 | 3,049 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Mistimed birth after 24 | 0.80 | 0.97 | 0.52 | 2.95 | 734 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Unplanned births | ||||||||||

| No unplanned birth after 24 | — | — | — | — | — | 0.36 | 1.11 | −0.66 | 1.47 | 2,659 |

| Unplanned birth after 24 | — | — | — | — | — | 0.57 | 1.10 | 0.50 | 2.82 | 925 |

Achieved parity at age 24.

Sum of the absolute value of the difference between achieved parity in 2006 and intended parity at age 24.

Sum of the signed value of the difference between achieved parity in 2006 and intended parity at age 24

NOTE: Analyses weighted with 2006 sampling weights.

Tables 6 and 7 present multinomial logistic analyses of the three-category dependent variable (completed fertility underachieved, achieved, or overachieved intentions at age 24). Table 6 shows the effects of the variables previously mentioned for women, and Table 7 shows corresponding results for men. Separate analyses for men and women allow us to vary all effects by sex (and thus allow for a fully interactive model). To test specific interactions with sex, we ran pooled models (shown in the Appendix). We set the achieved intentions category as the reference; odds ratios presented show the odds of having either underachieved or overachieved one’s intended fertility relative to having achieved one’s intentions.

TABLE 6.

Multinomial logistic regression predicting achievement, underachievement, and overachievement of fertility intentions for women

| Model 1: Age 24 |

Model 2: Childless and married |

Model 3: Marital transitions |

Model 4: Unplanned pregnancy |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under | Over | Under | Over | Under | Over | Under | Over | |

| Race | ||||||||

| Black | 1.08 | 1.58*** | 1.43*** | 1.42** | 1.08 | 1.53*** | 1.13 | 1.14 |

| (0.10) | (0.15) | (0.15) | (0.15) | (0.13) | (0.17) | (0.13) | (0.14) | |

| Other | 1.08 | 1.21 | 1.09 | 1.16 | 1.01 | 1.20 | 0.97 | 1.29 |

| (0.25) | (0.27) | (0.26) | (0.26) | (0.25) | (0.27) | (0.23) | (0.31) | |

| Age | 0.85 | 0.91 | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.95 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.99 |

| (0.07) | (0.09) | (0.09) | (0.09) | (0.09) | (0.09) | (0.08) | (0.11) | |

| Education at 24 | ||||||||

| High school | 2.34*** | 1.10 | 1.69** | 1.16 | 1.85*** | 1.13 | 1.92*** | 1.07 |

| (0.38) | (0.15) | (0.28) | (0.16) | (0.32) | (0.16) | (0.34) | (0.16) | |

| Some college | 3.24*** | 0.99 | 1.47* | 1.11 | 1.63* | 1.09 | 1.65* | 1.02 |

| (0.58) | (0.16) | (0.28) | (0.19) | (0.32) | (0.19) | (0.34) | (0.19) | |

| College and above | 3.29*** | 0.86 | 0.92 | 1.06 | 1.07 | 1.01 | 1.05 | 1.08 |

| (0.60) | (0.16) | (0.19) | (0.22) | (0.23) | (0.21) | (0.23) | (0.24) | |

| Enrolled at 24 | 1.68*** | 1.25 | 1.38 | 1.24 | 1.39* | 1.23 | 1.40* | 1.23 |

| (0.25) | (0.24) | (0.23) | (0.24) | (0.23) | (0.24) | (0.23) | (0.25) | |

| Children intended | ||||||||

| Less than 2 | 0.41*** | 2.03*** | 0.28*** | 2.11*** | 0.22*** | 2.19*** | 0.20*** | 2.96*** |

| (0.06) | (0.25) | (0.05) | (0.27) | (0.04) | (0.28) | (0.04) | (0.40) | |

| More than 2 | 2.41*** | 0.99 | 4.15*** | 0.94 | 4.38*** | 0.92 | 4.66*** | 0.63** |

| (0.24) | (0.12) | (0.49) | (0.12) | (0.52) | (0.12) | (0.56) | (0.09) | |

| Childless at 24 | 7.49*** | 0.70** | 8.12*** | 0.68** | 8.40*** | 0.66** | ||

| (0.98) | (0.09) | (1.10) | (0.09) | (1.16) | (0.09) | |||

| Married at 24 | 0.64*** | 0.84 | 0.79* | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.84 | ||

| (0.07) | (0.10) | (0.09) | (0.09) | (0.09) | (0.11) | |||

| Marital transitions | ||||||||

| Never married | 3.90*** | 0.66* | 3.94*** | 0.47*** | ||||

| (0.63) | (0.12) | (0.63) | (0.09) | |||||

| Divorced | 2.09*** | 0.70* | 2.12*** | 0.63** | ||||

| (0.32) | (0.11) | (0.33) | (0.11) | |||||

| Remarried | 1.25 | 0.86 | 1.28 | 0.78 | ||||

| (0.19) | (0.12) | (0.19) | (0.12) | |||||

| 3 or more transitions | 1.19 | 0.94 | 1.28 | 0.78 | ||||

| (0.22) | (0.16) | (0.24) | (0.15) | |||||

| Unwanted birth | 0.63 | 10.19*** | ||||||

| (0.20) | (1.88) | |||||||

| Mistimed birth | 0.46*** | 5.45*** | ||||||

| (0.08) | (0.71) | |||||||

| Constant | 0.25*** | 0.38*** | 0.14*** | 0.45*** | 0.08*** | 0.53*** | 0.08*** | 0.31*** |

| (0.04) | (0.05) | (0.02) | (0.07) | (0.02) | (0.09) | (0.02) | (0.06) | |

| Adjusted Wald tests | F(18,7642)=18.21 | F(22,7642)=27.24 | F(30,7642)=22.93 | F(34,7642)=26.05 | ||||

| Childless and married at 24 |

F(4,7639)=83.44 | F(4,7639)=77.99 | F(4,7639)=72.40 | |||||

| Marital transitions | F(8,7635)=16.08 | F(8,7635)=17.10 | ||||||

| Unplanned pregnancy | F(4,7639)=91.00 | |||||||

| Observations | 3,783 | 3,783 | 3,783 | 3,783 | ||||

NOTE: All analyses weighted with 2006 sampling weights. Coefficients reported as odds ratios. “Achieving intentions” is the omitted outcome category; “white” is the omitted category for race; “want 2 children” is the omitted category for children wanted; “unmarried at age 24” is the omitted category for married at 24; “less than high school” is the omitted category for education at 24; “not enrolled” is the omitted category for enrolled at 24; “stably married” is the omitted category for marital transitions. Standard errors shown in parentheses.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001 (two-tailed tests).

TABLE 7.

Multinomial logistic regression predicting achievement, underachievement, and overachievement of fertility intentions for men

| Model 1: Age 24 |

Model 2: Childless and married |

Model 3: Marital transitions |

Model 4: Unplanned pregnancy |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under | Over | Under | Over | Under | Over | Under | Over | |

| Race | ||||||||

| Black | 1.16 | 1.39** | 1.26* | 1.28* | 0.99 | 1.42** | 1.08 | 1.31* |

| (0.12) | (0.15) | (0.15) | (0.15) | (0.12) | (0.17) | (0.14) | (0.16) | |

| Other | 1.60* | 1.63 | 1.55 | 1.60 | 1.47 | 1.64* | 1.53 | 1.60 |

| (0.37) | (0.41) | (0.36) | (0.41) | (0.34) | (0.41) | (0.36) | (0.46) | |

| Age | 0.94 | 0.87 | 1.05 | 0.85 | 1.05 | 0.86 | 1.05 | 0.85 |

| (0.08) | (0.08) | (0.09) | (0.08) | (0.10) | (0.08) | (0.10) | (0.08) | |

| Education at 24 | ||||||||

| High school | 1.09 | 0.72* | 0.87 | 0.76 | 1.03 | 0.74* | 1.03 | 0.70* |

| (0.17) | (0.11) | (0.14) | (0.11) | (0.18) | (0.11) | (0.19) | (0.11) | |

| Some college | 1.36 | 0.49*** | 0.87 | 0.55** | 1.07 | 0.55** | 1.01 | 0.55** |

| (0.24) | (0.09) | (0.17) | (0.10) | (0.21) | (0.11) | (0.21) | (0.11) | |

| College and above | 1.11 | 0.54** | 0.50*** | 0.66* | 0.65* | 0.68 | 0.58* | 0.73 |

| (0.20) | (0.11) | (0.10) | (0.14) | (0.14) | (0.14) | (0.13) | (0.16) | |

| Enrolled at 24 | 0.98 | 1.16 | 0.79 | 1.16 | 0.83 | 1.12 | 0.84 | 1.14 |

| (0.16) | (0.22) | (0.14) | (0.22) | (0.15) | (0.21) | (0.15) | (0.23) | |

| Children intended | ||||||||

| Less than 2 | 0.24*** | 1.56*** | 0.18*** | 1.64*** | 0.11*** | 1.79*** | 0.09*** | 2.25*** |

| (0.04) | (0.20) | (0.03) | (0.22) | (0.02) | (0.25) | (0.02) | (0.32) | |

| More than 2 | 3.19*** | 0.99 | 4.94*** | 0.88 | 5.18*** | 0.89 | 5.91*** | 0.70* |

| (0.35) | (0.14) | (0.62) | (0.13) | (0.67) | (0.13) | (0.77) | (0.11) | |

| Childless at 24 | 5.76*** | 0.62*** | 6.03*** | 0.65** | 6.16*** | 0.66** | ||

| (0.85) | (0.08) | (0.93) | (0.09) | (1.00) | (0.09) | |||

| Married at 24 | 0.40*** | 0.86 | 0.51*** | 0.73* | 0.50*** | 0.82 | ||

| (0.05) | (0.11) | (0.07) | (0.10) | (0.07) | (0.11) | |||

| Marital transitions | ||||||||

| Never married | 4.83*** | 0.45*** | 4.77*** | 0.44*** | ||||

| (0.75) | (0.09) | (0.76) | (0.09) | |||||

| Divorced | 2.22*** | 1.02 | 2.24*** | 1.00 | ||||

| (0.40) | (0.19) | (0.42) | (0.19) | |||||

| Remarried | 1.38* | 1.59** | 1.47* | 1.51** | ||||

| (0.22) | (0.24) | (0.24) | (0.24) | |||||

| 3 or more transitions | 1.43 | 1.51* | 1.35 | 1.58* | ||||

| (0.33) | (0.28) | (0.32) | (0.31) | |||||

| Unplanned birth | 0.28*** | 3.85*** | ||||||

| (0.04) | (0.48) | |||||||

| Constant | 0.87 | 0.84 | 0.40*** | 1.13 | 0.21*** | 1.06 | 0.25*** | 0.65* |

| (0.13) | (0.12) | (0.08) | (0.20) | (0.05) | (0.21) | (0.06) | (0.13) | |

| Adjusted Wald tests | F(18,7642)=21.61 | F(22,7642)=28.29 | F(30,7642)=21.47 | F(32,7642)=25.98 | ||||

| Childless and married at 24 |

F(4,7639)=85.46 | F(4,7639)=64.67 | F(4,7639)=61.58 | |||||

| Marital transitions | F(8,7635)=21.46 | F(8,7635)=19.56 | ||||||

| Unplanned pregnancy | F(2,7641)=138.00 | |||||||

| Observations | 3,584 | 3,584 | 3,584 | 3,584 | ||||

NOTE: All analyses weighted with 2006 sampling weights. Coefficients reported as odds ratios. “Achieving intentions” is the omitted outcome category; “white” is the omitted category for race; “want 2 children” is the omitted category for children wanted; “unmarried at age 24” is the omitted category for married at 24; ““less than high school” is the omitted category for education at 24; “not enrolled” is the omitted category for enrolled at 24; “stably married” is the omitted category for marital transitions. Standard errors shown in parentheses.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001 (two-tailed tests).

APPENDIX TABLE 1.

Odds ratios and confidence intervals for the multinomial regression models, shown for underachieving and overachieving fertility intentions indicated at age 24, NLSY79 data

| Model 1: Main effects |

Model 2: Education interactions |

Model 3: Childless and married |

Model 4: Full model |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under | Over | Under | Over | Under | Over | Under | Over | |

| Race | ||||||||

| Black | 1.15* | 1.50*** | 1.14 | 1.49*** | 1.35*** | 1.36*** | 1.35*** | 1.36*** |

| (0.08) | (0.11) | (0.08) | (0.11) | (0.11) | (0.11) | (0.11) | (0.11) | |

| Other | 1.25 | 1.33 | 1.27 | 1.34 | 1.25 | 1.31 | 1.25 | 1.3 |

| (0.20) | (0.22) | (0.21) | (0.23) | (0.21) | (0.22) | (0.21) | (0.22) | |

| Women | 0.60*** | 0.76*** | 0.25*** | 0.50*** | 0.43*** | 0.46*** | 0.32*** | 0.45*** |

| (0.04) | (0.06) | (0.05) | (0.09) | (0.09) | (0.08) | (0.07) | (0.09) | |

| Age | 0.9 | 0.88 | 0.9 | 0.88 | 1.01 | 0.87* | 1.01 | 0.87* |

| (0.05) | (0.06) | (0.05) | (0.06) | (0.06) | (0.06) | (0.06) | (0.06) | |

| Education at 24 | ||||||||

| High school | 1.57*** | 0.9 | 1.09 | 0.73* | 0.84 | 0.76 | 0.88 | 0.76 |

| (0.17) | (0.09) | (0.16) | (0.11) | (0.13) | (0.11) | (0.14) | (0.11) | |

| Some college | 2.09*** | 0.72** | 1.36 | 0.50*** | 0.83 | 0.54** | 0.89 | 0.55** |

| (0.25) | (0.09) | (0.23) | (0.10) | (0.15) | (0.10) | (0.17) | (0.11) | |

| College and above | 1.91*** | 0.70** | 1.13 | 0.55** | 0.49*** | 0.65* | 0.53** | 0.68 |

| (0.24) | (0.09) | (0.20) | (0.11) | (0.09) | (0.13) | (0.10) | (0.14) | |

| Enrolled at 24 | 1.23 | 1.19 | 0.97 | 1.16 | 0.8 | 1.16 | 0.79 | 1.17 |

| (0.14) | (0.16) | (0.15) | (0.22) | (0.14) | (0.22) | (0.14) | (0.22) | |

| Children intended | ||||||||

| Less than 2 | 0.31*** | 1.81*** | 0.31*** | 1.78*** | 0.22*** | 1.87*** | 0.22*** | 1.86*** |

| (0.04) | (0.16) | (0.04) | (0.16) | (0.03) | (0.17) | (0.03) | (0.17) | |

| More than 2 | 2.70*** | 0.96 | 2.76*** | 0.97 | 4.54*** | 0.9 | 4.53*** | 0.9 |

| (0.20) | (0.09) | (0.20) | (0.09) | (0.39) | (0.09) | (0.39) | (0.09) | |

| Education*Sex | ||||||||

| HS*Women | 2.24*** | 1.51* | 2.19*** | 1.55* | 1.94** | 1.53* | ||

| (0.50) | (0.31) | (0.50) | (0.32) | (0.45) | (0.31) | |||

| Some college*Women | 2.53*** | 2.00** | 1.95* | 2.10** | 1.67 | 2.01** | ||

| (0.63) | (0.51) | (0.51) | (0.53) | (0.45) | (0.51) | |||

| College*Women | 3.06*** | 1.55 | 2.08** | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.56 | ||

| (0.77) | (0.42) | (0.55) | (0.46) | (0.49) | (0.45) | |||

| Enrolled*Women | 1.75* | 1.08 | 1.68* | 1.08 | 1.75* | 1.06 | ||

| (0.38) | (0.29) | (0.40) | (0.29) | (0.42) | (0.29) | |||

| Childless at 24 | 6.82*** | 0.66*** | 5.45*** | 0.61*** | ||||

| (0.67) | (0.06) | (0.75) | (0.08) | |||||

| Married at 24 | 0.51*** | 0.86 | 0.41*** | 0.87 | ||||

| (0.04) | (0.07) | (0.05) | (0.11) | |||||

| Married*Women | 1.51** | 0.95 | ||||||

| (0.24) | (0.16) | |||||||

| Childless*Women | 1.47* | 1.15 | ||||||

| (0.26) | (0.20) | |||||||

| Constant | 0.60*** | 0.64*** | 0.89 | 0.8 | 0.34*** | 1.04 | 0.41*** | 1.06 |

| (0.07) | (0.07) | (0.12) | (0.11) | (0.05) | (0.16) | (0.07) | (0.18) | |

| Adjusted Wald tests | F(20,7642)=35.68 | F(28,7642)=26.56 | F(32,7642)=39.33 | F(36,7642)=35.24 | ||||

| Enrolled*Sex | F(2,7641)=3.67 | F(2,7641)=2.51 | F(2,7641)=2.95 | |||||

| Education*Sex | F(6,7637)=3.99 | F(6,7637)=2.91 | F(6,7637)=2.25 | |||||

| Married*Sex | F(2,7641)=4.00 | |||||||

| Childless*Sex | F(2,7641)=2.00 | |||||||

| Observations | 7,367 | 7,367 | 7,367 | 7,367 | ||||

NOTE: All analyses weighted with 2006 sampling weights. Coefficients reported as odds ratios. “Achieved intentions” is the omitted outcome category; “white” is the omitted category for race; “want 2 children” is the omitted category for children intended; “unmarried at age 24” is the omitted category for married at 24; ““less than high school” is the omitted category for education at 24; “not enrolled” is the omitted category for enrolled at 24; “stably married” is the omitted category for marital transitions. 95% confidence intervals are reported in parentheses.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001 (two-tailed tests).

Table 6 contains four models. The first includes effects of specific life-course and structural variables, namely educational attainment at age 24, enrollment status at age 24, and intended parity at age 24, while controlling for effects of race/ethnicity (white/black/other). The second model includes all variables of interest at age 24, adding whether the respondent was childless at age 24 and married at age 24. Models 3 and 4 introduce life-course events that are not anticipated at age 24. Model 3 incorporates one of these variables, marital transitions. Model 4 incorporates unwanted and mistimed childbearing for women and unplanned childbearing for men. Selected interaction effects (by sex) are discussed in the text, and significance tests are performed using pooled data.8

Race and age

Age (scored as age-24) is included as a control. Almost all respondents (99 percent) were aged 23–25 at this measurement (see Table 1); within this narrow age range, younger respondents were slightly (but not significantly) more likely to under and overachieve (relative to meeting their intentions). Figure 2 shows that over a broader range, the age at which intent is measured has powerful effects—again, earlier measurement is associated with more frequent and larger errors.

Significant differences by race are captured by the contrast of black versus white (the omitted category). In bivariate results (Panel A of Table 4) and in Model 1 (of Tables 6 and 7), blacks are modestly more likely to underachieve intentions and significantly more likely to overachieve intentions. As we note later, the effect of being a black woman on overachieving fertility intentions is sharply attenuated if we control on reports of an unwanted birth.

Education and enrollment at age 24

Educational attainment at age 24 has four categories: less than completed high school (the omitted category), high school diploma, some college, and college or more. Enrollment indicates whether an individual was enrolled in any education program at age 24 (yes=1; 0 otherwise). These dimensions of education are strongly associated (most of those enrolled at age 24 have at least some college education), but the majority of persons in each education category are not enrolled.

As noted earlier, educational attainment can be thought of as a proxy for the types of jobs available to young women and men and the corresponding workplace environments that they will occupy during their childbearing years. These workplace demands and norms shape both fertility intentions and fertility decisions over time and thus influence whether an individual will achieve her/his fertility intentions. As expected, Table 4, Panel B shows that less-educated women have more children than more-educated women (as indicated by completed parity measured in 2006). Note the clear gradient also in the net and gross error: the least-educated are close to achieving their fertility goals (they slightly overachieve it), while the most-educated have the greatest deficit of children relative to intentions (e.g., net error for college or more is –0.54 births per woman) and more errors overall (gross error for these women is .98 births per woman). The multivariate analysis presented in Model 1 of Table 6 shows that women with high school education are 2.34 times more likely to underachieve compared to women with less than a high school education. This effect increases to 3.24 for women with some college. The effect increases only slightly for women with a college or higher degree (to 3.29), but many women in this category are still enrolled at age 24 (a factor that further increases the likelihood that the most-educated underachieve fertility intentions). Postponement of fertility is the hypothesized way in which highly educated women deal with long and demanding work schedules and a normative environment less supportive of childbearing. Table 6, Model 2 indicates that, once we include variables that measure postponement— childlessness and marital status, both at age 24—the effects of education are sharply attenuated. Thus the education effects operate primarily through the postponement of childbearing. Model 2 shows that the effect of high school versus no high school (on underachieving versus achieving intentions) is attenuated by 28 percent from 2.34 to 1.69. The odds of underachieving among women with some college (compared to those with less than high school) are sharply lowered—from 3.24 to 1.47. And lastly, the effects of a college or higher degree are completely explained by postponement. Therefore, much of the educational effect on underachieving fertility intentions is explained by the continued postponement of births; apparently these postponed births tend to lead to fertility forgone.

Schooling environments have strong norms against childbearing. As expected, Model 1 of Table 6 shows that being enrolled in school increases the odds of underachieving fertility intentions by a factor of 1.68. Again, enrollment in higher education is partially explained by postponement. In Model 2 of Table 6 the effect of enrollment on underachieving fertility intentions falls to 1.38 when postponement is included. Thus, fertility postponement is a strategy women use to reconcile multiple demanding roles. Postponed births may never be realized because the decision to further postpone may lead to a subsequent decision not to have children or because of the biological constraints of childbearing at older ages.

In sharp contrast, more-educated men and those currently enrolled at age 24 are not more likely to underachieve their fertility intentions compared to the less-educated. Once postponement is taken into account, highly educated men are actually less likely to underachieve their fertility intentions. For instance, Model 2 in Table 7 shows that college-educated men are only one-half (a factor of .50) as likely to underachieve intentions compared to men with the least education. We attribute these different effects in Tables 6 and 7 to the gender-based division of labor with respect to children whereby men can combine enrollment in higher education or demanding careers with having children because they bear less of the responsibilities and time demands of caring for them.

Number of children intended

Panel C of Table 4 shows that for both men and women, achieved fertility matches intentions most closely for those who intended exactly two children. In contrast, those who wanted fewer than two and those who wanted more than two overachieved and underachieved their fertility, which indicates that the range of achieved fertility is centered around two, and more narrowly so than intended fertility.

These bivariate findings are fully corroborated by the multivariate analyses in Tables 6 and 7, as intentions below two children are likely to be over-achieved and intentions for more than two are likely to be underachieved. Results for individuals intending fewer than two are constrained by the fact that having fewer children than intended is impossible if no children are intended and by the normative pressure for those intending one to revise intentions upward. Accordingly, Model 4 estimates show that (compared to those who intended two children) women and men who intend fewer than two children at age 24 are 0.2 and .09 times less likely to underachieve than to reach their target. However, this same group is also more than twice as likely (by a factor of 2.96 for women and 2.25 for men) to have more children than they intended, compared with those who intended two children. This is precisely the pattern one would expect if pronatalist pressures were continually prompting those who intended fewer than two children to reach a normative family size of two children.

Conversely, for those intending more than two children, we see evidence of opposite, antinatalist discouragement that limits the number of children to two. Women and men who want more than two children are 4.66 and 5.91 times more likely to underachieve compared to those intending two children. In sum, errors in non-normative intentions, either low or high, shift behavior toward the norm relative to intentions.

Age at first birth

As we noted above, fertility delay can lead to fertility forgone, and older ages at first birth should be associated with having fewer children than intended. The patterns observed in Panel D of Table 4 are consistent with this expectation for both men and women. Having children before age 24 for women and before age 29 for men predicts overachieving relative to intentions, while having them later is associated with underachieving. Estimates in Tables 6 and 7 show that these effects remain powerful in the face of controls, and they help account for the strong influence of education observed for women (discussed above).

In the second multivariate model, we include an indicator variable for childlessness at age 24 as a proxy for age at first birth. The estimates in Table 4 and Table in analyses not shown here indicate that having had a first birth prior to age 24 significantly differentiates between achieving, overachieving, and underachieving fertility intentions (see QVM). Thus in Tables 6 and 7 we include the dummy variable for “being childless at 24” for ease of interpretation. Compared with respondents who had children by age 24, both men and women who were childless were .66 times less likely to overachieve than to achieve fertility intentions. Likewise, women childless at 24 (compared to mothers) were 8.4 times more likely to have fewer children than intended; similarly this factor was 6.16 for childless men. Using pooled analysis (shown in the Appendix), we found that childless women at age 24 were significantly more likely than childless men to have fewer children than intended. Thus fertility is slightly more age constrained for women than for men; this may be due to a combination of biological and social factors, but the effect of child-lessness at a relatively late age is quite strong for both sexes. Consistent with these results, if intentions are achieved, childlessness in the early 20s reduces the chances of having more children than intended.

Married at age 24

This factor denotes a normative structural constraint, insofar as it is typically assumed in the United States that children should be born to married parents. In life-course terms, this means that marriage generally precedes, and can be seen as a precondition for, parenthood. In terms of net and gross errors, individuals who are not married at age 24 should have more difficulty achieving their fertility intentions than married individuals. But the association between marriage and fertility may also capture the effects of pregnancy/childbearing on marriage: marriage and fertility decisions might be joint ones, or pregnancy/childbearing might lead to marriage before age 24. Bivariate results (Table 4, Panel E) clearly support this hypothesis for both men and women. Indeed, while unmarried individuals have fewer children than intended, individuals who were married at age 24 appear to have achieved their fertility intentions, as their net error approaches zero. Accordingly, the results in Tables 6 and 7 for Model 2 show that being married at age 24 significantly reduces the likelihood of underachieving fertility—by a factor of .64 for women and .40 for men. Overall, being married at age 24 does not affect the likelihood of overachieving as opposed to achieving intentions.

Including proximate or intervening variables

As we noted earlier, the “errors” we document do not imply that fertility intentions are unreliable and invalid indicators of current intent. Rather, current intent cannot take account of future unanticipated factors that can influence fertility. Here we focus on two typical examples of unanticipated events that could occur between age 24 and 45 and affect the predictive validity of intentions. The first variable (set of contrasts) focuses on marriage: the omitted category is being stably married, with contrasts for being never married, divorced, divorced and remarried, and 3 or more marital transitions in this age range. As we noted above, marriage and fertility may be jointly determined. The second factor included is having an unwanted or mistimed birth. Another reason our analyses were run separately by sex is that the measurement of the fertility planning variables is different for men and women—specifically the unwanted versus mistimed distinction (among unplanned births) is not available in the male data.

Focusing on experience between the time members of the 1957–64 birth cohort were 24 years old and the 2006 interview, Table 5 shows achieved parity, gross and net error, and completed fertility for each marital transition category and for those reporting different fertility planning outcomes (un-wanted, mistimed, and unplanned births). Model 3 in Tables 6 and 7 includes the marital contrasts. Model 4 in Table 6 adds a contrast for women who had ever experienced an unwanted or mistimed birth at or after age 24. Model 4 in Table 7 adds a contrast for men who have ever experienced an unplanned birth at or after age 24.

Few individuals interviewed at age 24 planned not to marry, and few expected their marriages to end. Table 5 indicates that never marrying lowered eventual fertility by roughly a birth (women who never married had a net error of −.88, and men’s net error was −1.28). In Model 3 in Tables 6 and 7, multivariate regression shows that this strong effect remains in the face of other effects: for those who never married, the risk of underachieving fertility intentions increased by a factor of 3.90 for women and 4.83 for men, and the likelihood of overachieving decreased by a factor of .66 for women and .45 for men. Those who divorced (versus remaining married) at ages 24–45 are much more likely to have fewer children than intended: divorce increased the odds of underachieving by a factor of more than 2 for both women and men. Divorce reduced the likelihood of overachieving fertility (by a factor of .70) for women only. For women, the effects of divorcing and then remarrying (compared to remaining married) have weaker effects than divorcing alone—the effects on underachieving are more muted (1.25 instead of 2.09), as are the effects on overachieving (.86 instead of .70). Thus, women who remarried are more likely to achieve their intentions than those who divorced but did not remarry. However, women who remarried were still less likely to achieve their intentions than women who remained stably married. The effects of at least three marriage transitions (compared to remaining married) are similar to the effects just described for divorcing and remarrying for women. These effects show the powerful influence of marital status changes on the predictive validity of intentions at age 24.

Table 7 shows the same series of models for men. Results are strikingly similar. The most notable exception is the more pronatalist effect of remarriage for men. For women, getting divorced and remarried reduces the likelihood of overachieving by a factor of .78. The comparable estimate for men is 1.51. Multiple marriage transitions (3 or more) also increase the odds of overachieving (by a factor of 1.58) for men only. New marriages apparently offer men new opportunities for parenthood.

Unwanted and mistimed births have powerful effects on the likelihood of achieving fertility intentions. Focusing on women in the period after age 24, bivariate effects in Table 5 show that an unwanted birth produces a net error of .96 births and a mistimed birth a net error of .52 births; similarly for men, an unplanned birth after age 24 is associated with .50 more births than intended. In multivariate analysis these effects are shown while controlling for variables discussed above. Estimates from Model 4 of Table 6 show that an unwanted birth for women after age 24 increases the likelihood of over-achieving by a factor of 10.19 and reduces the likelihood of underachieving by a factor of .63. A mistimed birth decreases the odds of underachieving by a factor of .46 and increases the odds of overachieving by a factor of 5.45. For men, Model 4 of Table 7 shows that an unplanned birth increases the odds of overachieving by 3.85 and decreases the odds of underachieving by .28.

The powerful effect of unwanted births on overachieving is not surprising and could be viewed as a validity check. If one had stable intentions over the age range 24–45 and reported an unwanted birth at these ages, then logically speaking one would have to overachieve by one birth (as we define it). We see this effect in Table 5, where having an unwanted birth increases the net error by almost exactly one birth (.96). These relatively strong assumptions seem to be supported by this large effect. The strong effects of a mistimed pregnancy are more surprising. They suggest (as have other results we have discussed) that continued postponement of births is a major factor in missing a fertility target and that an “early” birth truncates this postponement. It is also possible that both of these variables—an unwanted birth or a mistimed pregnancy—signal an unwillingness to have an abortion—a fundamentally pronatalist stance transforming a mistimed or unwanted pregnancy into a birth. Also surprising is that the effects of most other variables discussed above are not attenuated by the inclusion of these powerful intervening variables (i.e., the effects estimated in Models 3 and 4 are very similar). The primary exception is race: the ten-dency for black women to overachieve fertility intentions is largely eliminated by the inclusion of these two fertility planning variables.

Discussion and conclusion

We have examined the predictive validity of reproductive intentions for the 1957–64 US birth cohorts. We find that the mean or net error—the mean difference between intended parity at age 24 and completed fertility in 2006—was relatively modest: −.25 and −.40 fewer children than intended, for women and men respectively. In the introduction, we noted that one logical possibility for the relatively high aggregate congruence between intentions and completed fertility observed in the United States was that American men and women may be particularly successful in achieving their intentions. Thus, we examined whether individual women and men were achieving their intended family size. We found that, for NLSY79 respondents, the answer is largely “no”—by 2006 (at age 45), only 43 percent of women had realized their intended parity at age 24. Instead, frequent errors in under- and overachieving fertility intentions are partly compensating to produce similar overall levels of intent and behavior. But, as indicated by the negative net error, underachieving is somewhat more common than overachieving.

Theoretical considerations stress the importance of structural constraints, and we sought to identify the processes that could produce the observed patterns of under/overachievement. The effects of life-course factors are clear— we found that both women and men who postponed childbearing or marriage were much more likely to have fewer births than they intended. The mechanisms discussed earlier that could account for this include: 1) declining fecundity with age, 2) repeated postponement of fertility because of competing, nonfamilial activities, and 3) the lack of a suitable marriage partner. In addition, we found smaller and fewer differences by sex than we had hypothesized. This suggests that social norms and other constraints affecting the timing of parenthood weigh heavily on men as well as on women, and thus may largely negate the fact that men are biologically capable of fathering children much later in life.

While we examined no international data, we can use this framework and these findings to speculate about very low fertility. For the NLSY79 cohorts, fertility delay was a widespread and normatively approved strategy for dealing with the competing demands of parenthood, human capital accumulation, and work (see Rindfuss et al. 1988). Data presented by Bongaarts (2001: Table 2) suggest that such forces may have been pervasive across developed countries. Beyond that, we saw that the relatively high congruence between intentions and achieved fertility in the United States was not the result of a great majority of individuals achieving their intentions exactly, but rather the result of compensating errors. In the cohorts we studied, a substantial proportion of individuals had more children than they had originally intended, and these individuals contributed over 40 percent of the births that occurred between age 24 and 2006, despite the fact that they constituted less than a fourth of the sample. It is possible that other countries do not experience this level of overachievement of fertility relative to individuals’ early intentions. If so, several factors may contribute to such differences. For instance, the higher congruence between completed fertility and early intentions in the United States could be the result of higher unwanted fertility or of less conflict or competition between childbearing and alternative opportunities. Finally, younger ages at first birth are another notable feature of US fertility that could play a role given the age-related likelihood of subfecundity and infecundity.

We conclude that the analysis presented in this article can explain variation across low-fertility populations. Frequently, a major part of the explanation is the disjunction between fertility intentions and behavior. In low-fertility countries women are having far fewer children than intended. The usefulness of our perspective in accounting for empirical observations in the NLSY79 data suggests that the framework may also be more broadly salient in accounting for fertility differences within and across societies.

Footnotes

An earlier version of this article (“Missing the target: More on the correspondence of fertility intentions and behavior in the U.S.”) was presented at the 2009 Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America, 30 April, Detroit Michigan. We thank Ronald Rindfuss for comments on earlier drafts.

To take advantage of the data from all available cohorts, we use multiple waves to define intended parity at age 24. QVM focused on age 22 and used only one-half of the NLSY79 sample. Thus, our results are not strictly comparable to those of QVM.

Our formalization ignores two other factors that Bongaarts (2001) discusses but that are of modest import for these US cohorts. The first is infant and child mortality. A child’s death is a rare event and one not likely to be factored into an intended number of children. But a child’s death could lead couples to have an additional child. Sex preferences might also play a role in revising intentions upward. Persons could reach their intention, of say two children, but not have realized their desired sex composition of children (e.g., for a child of each sex). The effect of these two factors would be modest for cohorts studied here and in most other contemporary developed countries (see Morgan 2003; Morgan and Hagewen 2005).

One likely path of influence is on a partner’s preferences. If there were no assortative mating by fertility intentions, then individuals with unusually high (or low) intentions would likely have a partner with lower (or higher) intentions. Substantial evidence indicates that partner’s intent influences couple intent and couple behavior (e.g., Morgan 1985; Thomson et al. 1990). Thus, strong family-size norms can operate through the influence of one’s partner and significant others (who, on average, would be less likely to hold high or low intentions).

Respondents who were not interviewed in 2006 (but were eligible for interview) intended slightly fewer children than those who were interviewed (2.14 and 2.25). Respondents lost to attrition were less likely to want more than two children at age 24 (30.7 percent of those lost versus 34.4 percent of those retained) and more likely to want fewer than two children (20.5 percent of those lost versus 17.2 percent of those retained). Also, respondents lost to attrition had fewer children at age 24 (.69) than those who were retained (.72).

Bongaarts (2001, 2002) chose intended parity at ages 30–34 for cross-national comparisons. We believe this misses a decade of experience key for understanding completed fertility, at least in the United States, which has a relatively young age at childbearing. See Figure 2 and accompanying discussion.

We have not yet examined the sensitivity of our results to choosing this particular age. As noted at the outset of this section, we chose this age because it balances our interest in a long time period over which to assess predictive validity with enough life-course experience to make these intentions realistic.

In this table we have combined 5 children and above into a 5+ category. In Table 2 calculations we retained greater detail available in the data, although a few persons intending more than 9 children were recoded to 9 intended children.

Because these analyses were weighted with 2006 sampling weights, the parameters were estimated with pseudo–maximum like-lihood methods (StataCorp 1999). While these methods yield the same point estimates as standard weighted maximum likelihood methods, they cannot be used for statistical inference (Skinner 1989). As a consequence, we did not rely on typical likelihood-based statistics, but instead estimated adjusted Wald tests where coefficients were jointly hypothesized to be zero. Finally, as a precaution, we also computed the more conservative Bonferroni-adjusted p-values (Korn and Graubard 1990), which fully confirmed existing results.

References

- Abma J, Chandra A, Mosher W, Peterson L, Piccinino LJ. Fertility, Family Planning and Women’s Health: New Data from the 1995 National Survey of Family Growth. 1997;23(19) National Center for Health Statistics, Vital Health Statistics Series. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake Judith. Is zero preferred? American attitudes toward childlessness in the 1970s. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1979;41:245–257. [Google Scholar]

- Blake Judith. The only child in America: Prejudice versus performance. Population and Development Review. 1981;7:43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Bongaarts John. Fertility and reproductive preferences in post-transitional societies. Population and Development Review. 2001;27 Supp.:260–281. [Google Scholar]

- Bongaarts John. The end of the fertility transition in the developed world. Population and Development Review. 2002;28:419–443. [Google Scholar]

- Bongaarts John, Feeney Griffith. On the quantum and tempo of fertility. Population and Development Review. 1998;24:271–291. [Google Scholar]

- Gerson Kathleen. Hard Choices: How Women Decide About Work, Career and Motherhood. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein Joshua R, Sobotka Tomáš, Jasilioniene Aiva. The end of ‘lowest-low’ fertility? Population and Development Review. 2009;35:663–699. [Google Scholar]

- Hagewen Kellie J, Morgan S Philip. Intended and ideal family size in the United States, 1970–2002. Population and Development Review. 2005;31:507–527. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2005.00081.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewlett Sylvia Ann. Creating a Life: Professional Women and the Quest for Children. New York: Talk Miramax Books; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Hanks Jennifer, Morgan S Philip, Bachrach Christine, Kohler Hans Peter. The American family in a theory of conjunctural action. Explaining Family Change Group Working Paper. 2006 « http://www.soc.duke.edu/~efc/publications.php».

- Korn Edward L, Graubard Barry I. Simultaneous testing of regression coefficients with complex survey data: Use of Bonferroni t statistics. The American Statistician. 1990;44:270–276. [Google Scholar]

- Miller Warren B, Pasta David J. Behavioral intentions: Which ones predict fertility behavior in married couples? Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1995;25:530–555. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan S Philip. Individual and couple intentions for more children. Demography. 1985;22:125–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan S Philip. Should Fertility Intentions Inform Fertility Forecasts?; Proceedings of US Census Bureau Conference: The Direction of Fertility in the United States; Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan S Philip. Is low fertility a twenty-first-century demographic crisis? Demography. 2003;40(4):589–603. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan S Philip, Hagewen Kellie. Is very low fertility inevitable in America? In-sights and forecasts from an integrative model of fertility. In: Booth A, Crouter AC, editors. The New Population Problem: Why Families in Developed Counties Are Shrinking and What It Means. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2005. pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell Martin, Rogers Carolyn C. Assessing cohort birth expectations data from the Current Population Survey, 1971–1981. Demography. 1983;20:369–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quesnel-Vallée Amélie, Morgan S Philip. Missing the target? Correspondence of fertility intentions and behavior in the U.S. Population Research and Policy Review. 2003;22:497–525. [Google Scholar]