Abstract

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a major health problem for postmenopausal women. Adjuvant hormonal therapy with aromatase inhibitors (AIs) in postmenopausal breast cancer patients further worsens bone loss. Bisphosphonates are able to prevent AI-induced bone loss, but limited data exists on their effect on bone structure. Our objectives were to: 1) examine the impact of AIs and non-AIs on hip structural geometry (HSA) of chemotherapy-induced postmenopausal women, and 2) determine if oral bisphosphonates could affect these changes.

Methods

This is a sub-analysis of a two-year double-blind randomized trial of 67 women with nonmetastatic breast cancer, newly menopausal following chemotherapy (up to 8 years), who were randomized to risedronate, 35 mg once weekly (RIS) and placebo (PBO). Many women changed their cancer therapy from a non-AI to an AI during the trial. Outcomes were changes in Beck's HSA-derived BMD and structural parameters.

Results

18 women did not receive adjuvant hormone therapy, while 41 women received other therapy and 8 received AIs at baseline distributed similarly between RIS and PBO. Women on AIs and PBO were found to have the lowest BMD and indices. RIS improved BMD and several HSA indices at the intertrochanteric site in women regardless of their hormonal therapy, but most improvement was observed in women who were not on AIs (all p≤0.05 except buckling ratio). Changes at the narrow neck and femoral shaft were similar.

Conclusion

The use of AIs appears to lead to lower HSA-derived BMD and hip structural indices as compared to women on no or non-AI therapy in chemotherapy-induced postmenopausal breast cancer patients. Preventive therapy with once weekly oral risedronate maintains structural, skeletal integrity independently of the use of or type of adjuvant therapy.

Introduction

The negative impact on bone mass from adjuvant hormonal therapy with aromatase inhibitors (AIs) in postmenopausal women with breast cancer and the preventive role of bisphosphonates, have been well described [1–6]. Bone strength and facture risk, depend on both bone mass as well as bone structure [7]. However, the impact of AIs and the concurrent use of bisphosphonates on bone structure has not been previously investigated.

The risedronate's effect on bone in women with breast cancer Study (REBBeCA Study) found that administration of once weekly risedronate for two years in newly postmenopausal women with breast cancer, positively affected spine and hip BMD and bone turnover, independent of their concurrent use of an aromatase inhibitor (AI) [8]. The objectives of this secondary analysis were to 1) examine the impact of AIs on hip structural geometry, using the hip structural analysis (HSA) program of Beck [9–11], and to 2) determine if therapy with oral bisphosphonates could affect these changes.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This secondary analysis reports the hip structural geometry changes of 67 women, who had recently become postmenopausal (≤ 8 years) after having received polyadjuvant chemotherapy for nonmetastatic breast cancer and who had been randomized to active treatment with risedronate (35 mg po once weekly) or a matched placebo as part of a two year double-blinded trial (as previously described in detail elsewhere) [8]. Briefly, women were excluded if they suffered from a second primary cancer or from abnormal bone and mineral metabolism (due to medications or underlying disorders such as hyperthyroidism, malabsorption, renal failure, and hepatic failure). The study did not limit the concurrent use of hormonal therapy prescribed by their oncologist [allowing them to freely initiate or change a hormonal agent if medically necessary (e.g. aromatase inhibitor (AI) or estrogen receptor agonist antagonist)]. Women with a current fracture or osteoporosis by bone mineral density (initial BMD T-score of −2.5 or below at the hip or spine) were allowed to enter the study after extensive counseling.

If participants were found to have a daily calcium intake <1200 mg using a validated questionnaire [12], they received supplementary calcium with vitamin D (Oscal Plus D, calcium carbonate 500mg with 200 IU of vitamin D, supplied by Procter & Gamble). The University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board approved the protocol. Participants were advised of the nature of the study and they provided written informed consent prior to participation.

Outcome Variables

The hip structural analysis (HSA) program uses mineral mass and dimensional data from conventional DXA images of the hip to measure the structural dimensions of bone cross-sections corresponding to three thin regions traversing the proximal femur (see Fig. 1). These include the narrow neck (across the neck at its narrowest point), the intertrochanteric region (along the bisector of the angle between neck and shaft axes), and the femoral shaft (at a distance equal to 1.5 times minimum neck width, distal to the intersection of the neck and shaft axes). The HSA-parameters assessed at these three sites include BMD as well as five geometric parameters, i.e. cross sectional area (CSA; total surface area of bone material in a plane orthogonal to the long axis of bone), cross sectional moment of inertia (CSMI; reflects the ability of bone to resist bending forces at compressive surface), section modulus (SM: measure of bending strength), cortical thickness, and buckling ratio (BR: reflects the ability of bone to resist bending forces at tensile surface) as previously described [9–11, 13, 14]. The CV for the HSA-derived parameters at each site have been listed in Table 2 [15].

Figure 1.

DXA scan of the hip, showing the cross-sectional regions from which the geometry is derived (i.e. narrow neck, intertrochanter, and femoral shaft together with representative mass profiles) [11].

Table 2.

Precision error (CV%) for Hologic QDR4500 derived HSA variables at the Narrow Neck (NN), Intertrochanteric (IT), and Femoral Shaft (FS) regions using 129 scan pairs [15].

| IT | FS | NN | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bone Mineral Density | 2.6 | 2.2 | 3 |

| Cross-sectional area | 2.9 | 2.3 | 3 |

| Cross-sectional moment of inertia | 4.6 | 3.2 | 4.3 |

| Section modulus | 4 | 2.5 | 4 |

| Cortical thickness | 3.2 | 3.1 | 3.2 |

| Buckling ratio | 4.8 | 3.5 | 4.6 |

Adjuvant Hormonal Therapy

Subjects were operationally considered to have been on an AI if they had been on anastrazole (Arimidex®), exemestane (Aromasin®) or letrozole (Femara®) for at least three of the 12 months immediately preceding a follow-up HSA assessment. Those who were not on adjuvant therapy or were on other medication such as tamoxifen (Nolvadex®), toremifene (Fareston®) and fulvestrant (Faslodex®) were assigned to the no-AI group.

Statistical Analysis

All data analysis was performed using SAS® version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina). First, we compared the baseline characteristics of the two treatment arms (risedronate/placebo) using independent samples t- and Fisher's exact tests. Second, we examined within treatment arm change from baseline to 12 and 24 months using paired samples t-tests. Third, we examined the effect of risedronate on HSA outcomes by fitting a linear mixed model with change from baseline in each outcome as the dependent variable; treatment arm (risedronate/placebo), follow-up time (12/24 months) and their interaction as fixed effects of interest; and a subject random effect to account for multiple follow-up assessments from the same subjects. We used appropriately constructed contrasts to assess the treatment effect at 12 and at 24 months. Fourth, we examined the changes in HSA outcomes in the two treatment arms (risedronate/placebo) considering the increasing use of an AI as adjuvant cancer therapy during the course of the trial. We operationally defined a subject to have been an AI user at a given follow-up assessment if she had been on an AI for at least three of the 12 months immediately preceding the assessment. We excluded from analysis two subjects who switched from an AI to a non-AI during the course of the trial; and any assessments after a subject has switched cancer therapy to keep the cancer therapy classification of a subject as unambiguous as possible. Thus, this analysis used only data from subjects before changing their cancer therapy to an AI, thus avoiding the bias that would otherwise be created by possible detrimental effects of AIs on bone structural integrity. We fit a mixed linear model using only data from subjects before cancer therapy, with change from baseline in each outcome as the response variable; treatment group (risedronate/placebo), time (12/24 months), dominant cancer therapy since previous assessment (AI/no AI) and their interaction as fixed effects of interest; baseline measurement of the outcome as a covariate; and a subject random effect to account for multiple measurements from the same subjects over time. Both raw and percent changes were considered in all analyses to ensure robustness of results.

Results

Clinical characteristics at baseline

Information about screening, randomization and follow-up are published in detail elsewhere[8]. Briefly, of the 87 participants randomized (43 for risedronate; 44 for placebo), 72 remained in the study after two years (34 risedronate; 38 placebo) [8]. Five patients were lost to follow-up, while one developed metastatic progression of her disease, and nine participants did not sign a consent form for a second year extension. Of the remaining 72, only 67 subjects had HSA measures and were included in the current analysis. Subjects included in the analysis were older compared to those excluded (50.4 vs. 47.1 years; p=0.0174), but there were no significant differences in years post-menopausal (p=0.9837), L1-L4 spine BMD (p=0.6951) or total hip BMD (p=0.4829).

The baseline clinical and skeletal-related characteristics of two treatment groups are published in detail elsewhere [8]. The HSA-derived markers of bone health were not significantly different between the treatment arms as displayed in Table 1. The mean age was 50 years. According the WHO criteria [16], the mean bone density measurements were in the normal range. Two percent (2.3%) had osteoporosis while the remainder had normal (49.4%) or low (48.3%) bone mass.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical characteristics, bone mineral density and hip structural parameters (none of the between-group differences was statistically significant at p < 0.05) [8].

| Parameters | Placebo Mean±SE [Median] (n= 35) | Risedronate Mean±SE [Median] (n=32) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 50.4±0.8 | 50.4±0.9 |

| Years Postmenopausal | 3.0±0.3 | 3.3±0.4 |

| Aromatase Inhibitor Use [N (%)] | 4 (11.4) | 4 (12.5) |

| HSA-lntertrochanter BMD | 0.805±0.020 [0.794] | 0.801±0.019 [0.791] |

| HSA-Femoral shaft BMD | 1.262±0.025 [1.255] | 1.244±0.030 [1.246] |

| HSA-Narrow Neck BMD | 0.801±0.019 [0.811] | 0.826±0.019 [0.827] |

| Posteroanterior Lumbar Spine BMD | 1.001±0.022 [0.998] | 0.984±0.021 [0.985] |

| Total hip BMD | 0.906±0.018 [0.888] | 0.913±0.016 [0.909] |

| Intertrochanter | ||

| Bone cross-sectional area (cm2) | 3.766±0.092 | 3.812±0.103 |

| Cross Sectional Moment of Inertia (cm4) | 8.507±0.272 | 8.949±0.374 |

| Section modulus (cm3) | 3.047±0.083 | 3.155±0.105 |

| Cortical thickness (cm) | 0.327±0.009 | 0.317±0.008 |

| Buckling ratio | 8.734±0.268 | 9.040±0.251 |

| Femoral shaft | ||

| Bone cross-sectional area (cm2) | 3.315±0.071 | 3.390±0.099 |

| Cross Sectional Moment of Inertia (cm4) | 2.338±0.077 | 2.575±0.117 |

| Section modulus (cm3) | 1.654±0.042 | 1.756±0.060 |

| Cortical thickness (cm) | 0.462±0.012 | 0.450±0.013 |

| Buckling ratio | 3.113±0.088 | 3.314±0.113 |

| Narrow Neck | ||

| Bone cross-sectional area (cm2) | 2.243±0.061 | 2.327±0.054 |

| Cross Sectional Moment of Inertia (cm4) | 1.559±0.070 | 1.647±0.064 |

| Section modulus (cm3) | 0.980±0.034 | 1.025±0.031 |

| Cortical thickness (cm) | 0.154±0.004 | 0.159±0.004 |

| Buckling ratio | 10.475±0.312 | 10.248±0.305 |

Abbreviations: SE - Standard error.

Changes from baseline over 24 months in HSA obtained BMD and structural parameters

Risedronate vs. placebo (not stratified for the concurrent use of AIs, figure 2)

Figure 2.

Absolute changes (mean ± SE) over 24 months of HSA-derived BMD (g/cm2) and structural parameters [cross-sectional area (CSA, unit = cm2), cross sectional moment of inertia (CSMI, unit = cm4), section modulus (SM, unit = cm3), cortical thickness (CT, unit = cm), buckling ratio (BR)] of women randomized to risedronate versus placebo at the intertrochanteric site (figure 2A) and femoral shaft (figure 2B).

* Difference from baseline p-value ≤ 0.05, † Between group difference p-value ≤ 0.05.

At the intertrochanteric site, treatment with risedronate for two years resulted in a significant improvement from baseline of BMD (mean ± SE), CSA, CSMI, SM, and cortical thickness (p ≤ 0.05). The BMD, CSA, CT, and BR were significantly improved compared to placebo as well (p ≤ 0.05). The changes at the femoral shaft revealed similar trends, but were not found at the narrow neck.

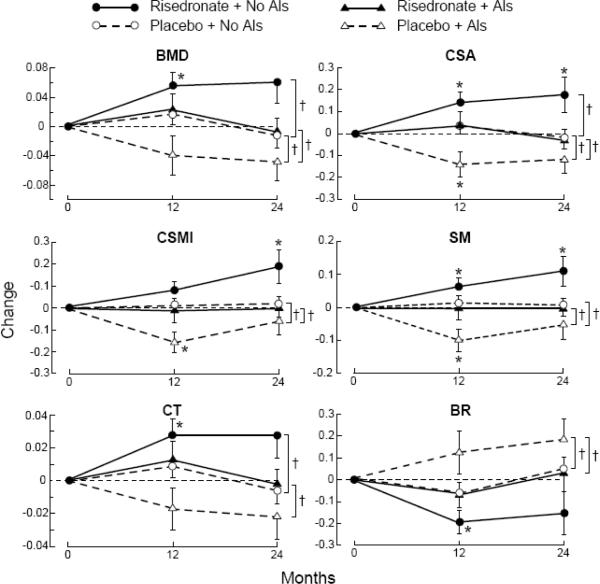

Risedronate vs. placebo (stratified for concurrent use of AIs; figure 3)

Figure 3.

Absolute changes (mean ± SE) over 24 months of HSA derived BMD (g/cm2) and structural parameters [cross-sectional area (CSA, unit = cm2), cross sectional moment of inertia (CSMI, unit = cm4), section modulus (SM, unit = cm3), cortical thickness (CT, unit = cm), buckling ratio (BR)] of women randomized to risedronate versus placebo, stratified for their concurrent use of AIs at the intertrochanteric site (figure 3A) and femoral shaft (figure 3B).

Difference from baseline - * p-value ≤ 0.05.

Between group difference - † p-value ≤ 0.05.

The greatest absolute improvement of the BMD and HSA parameters was observed in the risedronate/no-AI group at intertrochanteric site (BMD, CSA, CSMI, SM, and CT; p ≤ 0.05 compared to baseline) and femoral shaft (CSA, CSMI, SM; p ≤ 0.05 compared to baseline). In contrast, the BMD and HSA parameters at the intertrochanteric and femoral shaft sites remained stable with trends for decreases or deterioration in women randomized to placebo (with or without concurrent use of AIs) as well as in women randomized to risedronate concurrently using AIs.

Women who were randomized to risedronate and using an AI experienced significantly less improvements in BMD, CSA, CT, and buckling ratio at the intertrochanteric site over 2 years compared to women who were not taking an AI (p ≤ 0.05). Finally, women who were randomized to placebo demonstrated a larger loss if taking an AI versus no-AI at the intertrochanteric site for BMD, CSA, SM, CT, and BR (p ≤ 0.05). These trends were observed at the femoral shaft (figure 3B) and narrow neck as well, but statistical significance was not achieved.

Discussion

This secondary analysis of the REBBeCA Study demonstrated that chemotherapy-induced, newly postmenopausal women with breast cancer who received risedronate versus placebo had an improvement in the structural integrity independent of concurrent use of aromatase inhibitors. However, the improvement was greater in women who were not on concurrent AIs (e.g. women not receiving hormonal therapy or receiving therapy with agents other than AIs such as Estrogen Receptor Agonists Antagonists).

Although the impact of AIs on BMD has been studied extensively [1–6], few data are available on the effect of AIs on bone structure. However, the effect of estrogen receptor agonist antagonists on bone structure has been examined in postmenopausal women [17]. Women who received 3 years of raloxifene had improvements in CSA, section modulus, and buckling ratio. In contrast, women in our study in the no-AI group, and randomized to placebo, were not found to have a positive change of structural parameters This may be explained by the fact that only a subset of women in the no-AI group were using an estrogen receptor agonist-antagonist, tamoxifen. The level of evidence for the protective effect of bisphosphonates on AI induced loss of BMD is greater for intravenous bisphosphonates than for oral bisphosphonates [4], while their protective effect on AI-induced loss of bone structure has been underexplored.

We found that the changes at the intertrochanteric site were significantly greater than at the femoral shaft and narrow neck. Other investigators have also reported differences in impact of treatment on different regions. For example, Petit et al. found site-differential effects of estrogens versus testosterone [18]. Uusi-Rasi et al. reported the greatest improvement at the narrow neck with teriparatide treatment [19]. We previously reported the greatest impact of risedronate at the intertrochanteric site, which is composed of more trabecular than cortical bone [20]. The impact of treatment on the ratio of trabecular versus cortical bone may be responsible for some of these differences in site-specific findings. In clinical trials risedronate and other bisphosphonates often have a greater impact on sites rich in trabecular bone like the spine [21].

There are several general limitations to this study. The HSA methodology has several limitations [11, 20, 22]. Hip structural analysis is obtained indirectly by mathematical manipulation of two-dimensional data generated by DXA scanners. Another limitation is that menopausal status varied up to 8 years, with an average of 3.3 years postmenopausal prior to participation. The third potential limitation concerns the absence of restrictions for study participants on initiating, stopping, changing to or from any type of hormonal agent (AIs versus no-AIs). Since the FDA approved AIs for adjuvant use of breast cancer patients during the progress of our study, this could have decreased our ability to detect a prolonged treatment effect of AIs versus no-AIs throughout the 2 year duration of the study.

There are also several strengths to this study. This study is the first study to examine the effect of risedronate on geometric-, and strength-derived parameters in chemotherapy-induced postmenopausal women concurrently being treated with AIs versus no-AIs. Second, the control group did receive an active treatment, i.e. calcium and vitamin D (making it more challenging to detect a treatment effect). Finally, this was a single-center study, using a single bone densitometer and a small number of technologists, reducing equipment-related and between-site variability.

In conclusion, women with breast cancer and chemotherapy-induced menopause, the use of AIs leads to lower HSA-derived BMD and hip structural parameters as compared to women not on AIs. Preventive therapy with once weekly oral risedronate improves structural, skeletal integrity independent of their concurrent use of AIs. The greatest improvements were observed in women who were not taking AIs and were on risedronate. These findings may help target preventive treatment to maximize bone health in women on aromatase inhibitors.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This study was supported in part by NIH/NIDDKD grant K24 DK062895-03 (PI: Greenspan), a Non-Company Sponsored Trial (NCST) from Procter & Gamble and the Alliance for Better Bone Health and to the Translational Clinical Research Center of the University of Pittsburgh by the NIH/NCRR (M01-RR00056), and NIH/NIA grant T32 AG021885 (PI: Studenski). None of these funding agencies were involved in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript. Risedronate, matching placebo, calcium and vitamin D supplements were provided by Procter & Gamble, Inc. We are indebted to the nursing, professional, laboratory, dietary, administrative, and study staff of the Translational Clinical Research Center and Osteoporosis Prevention and Treatment Center at the University of Pittsburgh. Finally, we acknowledge the members of the Data and Safety Monitoring Board for their oversight of the study. We acknowledge Thomas J. Beck for his advice and Julia Khorana for creation of graphics.

All funding sources supporting publication of a work or study:

-

○

NIH/NIDDKD (K24: DK062895-05).

-

○

NCST from Alliance for Better Bone Health.

-

○

NIH/NCRR (M01: RR00056).

-

○

NIH/NIA (T32: AG021885, 5P30AG024827).

Conflict of Interest: Dr Bhattacharya serves on the Speaker's bureau for Novartis, is a co-principal investigator for AMGEN, and has received funding from Procter and Gamble Inc. as well as PRA International. SL Greenspan has received grant-support from Procter and Gamble, Inc., Merck Research Laboratories, Amgen, Lilly and Novartis. SL Greenspan also serves as a consultant for Merck Research Laboratories and Amgen. S Perera has received funding in the past from Eli Lilly & Co., Ortho Biotech, LLC, Teva Neuroscience for observational research. All other authors have no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

- HSA

Hip structural analysis

- BMD

Bone mineral density

- AIs

Aromatase inhibitors

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Brufsky AM. Bone health issues in women with early-stage breast cancer receiving aromatase inhibitors. Curr Oncol Rep. 2008;10:18–26. doi: 10.1007/s11912-008-0005-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Reid DM, Doughty J, Eastell R, Heys SD, Howell A, McCloskey EV, Powles T, Selby P, Coleman RE. Guidance for the management of breast cancer treatment-induced bone loss: a consensus position statement from a UK Expert Group. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34(Suppl 1):S3–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Coleman RE, Body JJ, Gralow JR, Lipton A. Bone loss in patients with breast cancer receiving aromatase inhibitors and associated treatment strategies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34(Suppl 1):S31–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hadji P, Body JJ, Aapro MS, Brufsky A, Coleman RE, Guise T, Lipton A, Tubiana-Hulin M. Practical guidance for the management of aromatase inhibitor-associated bone loss. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1407–16. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Coleman RE, Body J-J, Gralow JR, Lipton A. Bone loss in patients with breast cancer receiving aromatase inhibitors and associated treatment strategies. Cancer Treatment Reviews. 2008;34:S31–S42. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Chien AJ, Goss PE. Aromatase Inhibitors and Bone Health in Women With Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5305–5312. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.5382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Seeman E, Delmas PD. Bone Quality -- The Material and Structural Basis of Bone Strength and Fragility. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2250–2261. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra053077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Greenspan SL, Brufsky A, Lembersky BC, Bhattacharya R, Vujevich KT, Perera S, Sereika SM, Vogel VG. Risedronate Prevents Bone Loss in Breast Cancer Survivors: A 2-Year, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2644–2652. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.2967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Beck TJ, Ruff CB, Scott WW, Jr., Plato CC, Tobin JD, Quan CA. Sex differences in geometry of the femoral neck with aging: a structural analysis of bone mineral data. Calcified Tissue International. 1992;50:24–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00297293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Beck TJ, Stone KL, Oreskovic TL, Hochberg MC, Nevitt MC, Genant HK, Cummings SR. Effects of current and discontinued estrogen replacement therapy on hip structural geometry: the study of osteoporotic fractures. Journal of Bone & Mineral Research. 2001;16:2103–10. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.11.2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Greenspan SL, Beck TJ, Resnick NM, Bhattacharya R, Parker RA. Effect of Hormone Replacement, Alendronate, or Combination Therapy on Hip Structural Geometry: A 3-Year, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2005;20:1525–1532. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Dawson-Hughes B, Jacques P, Shipp C. Dietary calcium intake and bone loss from the spine in healthy postmenopausal women. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1987;46:685–7. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/46.4.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Beck TJ. Extending DXA beyond bone mineral density: understanding hip structure analysis. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2007;5:49–55. doi: 10.1007/s11914-007-0002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bonnick SL. HSA: beyond BMD with DXA. Bone. 2007;41:S9–12. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Khoo BCC, Beck TJ, Qiao Q-H, Parakh P, Semanick L, Prince RL, Singer KP, Price RI. In vivo short-term precision of hip structure analysis variables in comparison with bone mineral density using paired dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scans from multi-center clinical trials. Bone. 2005;37:112–121. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kanis JA. Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis: synopsis of a WHO report. WHO Study Group. Osteoporos Int. 1994;4:368–81. doi: 10.1007/BF01622200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Uusi-Rasi K, Beck TJ, Semanick LM, Daphtary MM, Crans GG, Desaiah D, Harper KD. Structural effects of raloxifene on the proximal femur: results from the multiple outcomes of raloxifene evaluation trial. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17:575–86. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-0028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Petit MA, Beck TJ, Lin H-M, Bentley C, Legro RS, Lloyd T. Femoral bone structural geometry adapts to mechanical loading and is influenced by sex steroids: the Penn State Young Women's Health Study. Bone. 2004;35:750–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Uusi-Rasi K, Semanick LM, Zanchetta JR, Bogado CE, Eriksen EF, Sato M, Beck TJ. Effects of teriparatide [rhPTH (1–34)] treatment on structural geometry of the proximal femur in elderly osteoporotic women. Bone. 2005;36:948–58. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].van Londen GJ, Perera S, Vujevich KT, Sereika SM, Bhattacharya R, Greenspan SL. Effect of risedronate on hip structural geometry: a 1-year, double-blind trial in chemotherapy-induced postmenopausal women. Bone. 2008;43:274–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Harris ST, Watts NB, Genant HK, McKeever CD, Hangartner T, Keller M, Chesnut CH, III, Brown J, Eriksen EF, Hoseyni MS, Axelrod DW, Miller PD, the Vertebral Efficacy With Risedronate Therapy Study Group Effects of Risedronate Treatment on Vertebral and Nonvertebral Fractures in Women With Postmenopausal Osteoporosis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Jama. 1999;282:1344–1352. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.14.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Beck TJ, Looker AC, Ruff CB, Sievanen H, Wahner HW. Structural trends in the aging femoral neck and proximal shaft: analysis of the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry data. Journal of Bone & Mineral Research. 2000;15:2297–304. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.12.2297. see comment. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]