Abstract

OBJECTIVE

It is generally admitted that the endocrine cell organization in human islets is different from that of rodent islets. However, a clear description of human islet architecture has not yet been reported. The aim of this work was to describe our observations on the arrangement of human islet cells.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Human pancreas specimens and isolated islets were processed for histology. Sections were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy after immunostaining for islet hormones and endothelial cells.

RESULTS

In small human islets (40–60 μm in diameter), β-cells had a core position, α-cells had a mantle position, and vessels laid at their periphery. In bigger islets, α-cells had a similar mantle position but were found also along vessels that penetrate and branch inside the islets. As a consequence of this organization, the ratio of β-cells to α-cells was constantly higher in the core than in the mantle part of the islets, and decreased with increasing islet diameter. This core-mantle segregation of islet cells was also observed in type 2 diabetic donors but not in cultured isolated islets. Three-dimensional analysis revealed that islet cells were in fact organized into trilaminar epithelial plates, folded with different degrees of complexity and bordered by vessels on both sides. In epithelial plates, most β-cells were located in a central position but frequently showed cytoplasmic extensions between outlying non–β-cells.

CONCLUSIONS

Human islets have a unique architecture allowing all endocrine cells to be adjacent to blood vessels and favoring heterologous contacts between β- and α-cells, while permitting homologous contacts between β-cells.

Islets of Langerhans are micro-organs located in the pancreas and composed of at least four types of endocrine cells. The α- and β-cells are the most abundant and also the most important in that they secrete hormones (glucagon and insulin, respectively) crucial for glucose homeostasis. The prevailing description of islet cell composition and structure comes from studies performed in rats and mice. It is generally accepted that endocrine cells are not randomly distributed into islets. In most rodents, β-cells compose the core of the islets and the non–β-cells, including α-, δ-, and pancreatic polypeptide (PP)-cells, form the mantle region. This unique architecture appears to have some functional implications (1). For instance, in several murine models in which insulin secretion is decreased, normal organization of islet cells was found to be perturbed (2) so that β-cells were intermingled with non–β-cells. In addition, in vitro experiments showed that homologous contacts between rat β-cells improved their function, as heterologous contacts between β- and non–β-cells had no effect (3). This observation suggests that a core-mantle segregation of islet cells is useful in favoring homologous contacts between β-cells, which in turn improves insulin secretion. The characteristic islet architecture may also serve to facilitate interactions among the different islet hormones via interstitial or vascular routes (4,5).

The sparse works on the structure of human islets do not provide a clear description of their cellular organization. There is a consensus on the different endocrine cell types, which do not differ significantly between rodent and human islets, and on the proportion of islet β-cells that is lower in humans compared with rodents (6–8). Controversies persist about the topographic arrangement of endocrine cells within human islets. Although human islets are sometimes still presented with a simple core-mantle architecture similar to that of rodent islets, decades ago many reports described human islets with a different cell organization (1,9–11). Pioneer work from Orci and Unger (1) depicted human islets with α- and δ-cells located in the mantle and grouped against capillary walls within the core of β-cells. It has been also proposed that human islets were subdivided into lobules or subunits comprising clusters of β-cells surrounded by α-cells (9,11) and that these lobules or subunits were separated by vascularized connective tissue and non–β-cells (9). Grube et al. (10) proposed a different organization in which endocrine cells were organized in a ribbon-like manner rather than in separated subunits. In their model, β-cells are located in the islet core and α-cells are arranged at the periphery and along intraislet capillaries. These views were challenged by more recent publications claiming that endocrine cell types were dispersed throughout the human islets (8,12). A summary of this controversy has been skillfully reviewed by Bonner-Weir and O'Brien, who furthermore described human islets as complex cell arrangements with different profiles including cloverleaf pattern (6).

The purpose of this work was to bring some clarification to this controversy by describing our observations on the distribution of α- and β-cells in human islets.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Pancreas procurement.

Human pancreata were harvested from adult heart-beating, brain-dead donors and designed to be processed for islet isolation and transplantation. For different reasons (prolonged ischemia time, suspicion of tumors, etc), some pancreata were not processed for islet isolation and small specimens were taken for histology. Specimens from 21 donors were used for these analyses. Sixteen specimens were from nondiabetic donors with a mean age of 40.1 ± 16.2 years (range: 15–69) and a mean BMI of 25.2 ± 2.9 kg/m2 (range: 20–29). Five specimens were from five type 2 diabetic donors with a mean age of 57.8 ± 9.1 years (range: 42–65) and a BMI of 32.3 ± 10.0 kg/m2 (range: 26–50). Glycemia at the time of hospital admission was 8.9 ± 3.8 mmol/l (mean ± SD, n = 12) for nondiabetic donors and 13.9 ± 5.3 (mean ± SD, n = 5) for type 2 diabetic donors. Specimens from nondiabetic donors were obtained from head (n = 4), body (n = 2), tail (n = 5) and unspecified regions (n = 9) of the pancreas (for four pancreata, specimens from both the head and the tail were available). Specimens from type 2 diabetic donors were obtained from head (n = 1), body (n = 2), and tail (n = 2) of the pancreas. Histopathologic analysis of the diabetic specimens revealed no apparent alteration of the islets. However, by double immunofluorescence for insulin and amylin (using a rabbit anti-amylin antibody purchased from Progen Biotechnik, Heidelberg, Germany), several β-cells were found to be positive for amylin, in all five specimens. In one specimen, extracellular staining for amylin was also observed. Mouse pancreata were harvested from C57/BL6 mice (Janvier Laboratories, Le Genest-Saint-Isle, France). To this end, mice were first anesthetized and then exsanguinated by aortic sectioning. Pancreata were rinsed in PBS before processing for histology.

Islet and islet cell isolations.

Human islet isolations were performed as previously described according to the Ricordi method with local adaptations (13,14). The use of human islets for research was approved by our local institutional ethics committee. After purification, islets were cultured overnight at 37°C, and at 25°C thereafter, in CMRL medium containing 5.6 mmol/l glucose and supplemented with penicillin, streptomycin, glutamine, HEPES, and 10% FCS (hereafter referred to as complete CMRL). Islets used for morphologic analysis were cultured for a total of 36–48 h. For islet cell dispersion, cultured islets were rinsed in PBS and incubated in Accutase (Sigma, St Louis, MO) for ∼9 min with occasional pipetting. Single-cell suspensions (∼90% single cells) were rinsed with complete CMRL, and aliquots of 105 cells were incubated for 24 h at 37°C in nonadherent 60-mm–diameter Petri dishes containing 6 ml complete CMRL. Cells were harvested and attached within Cunningham chambers (15) for immunofluorescence assessment.

Histologic sections of pancreata and isolated islets.

Pancreas samples were incubated for 24 h in (methanol-free) 10% formalin, dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin. Isolated islets were incubated for 24 h in methanol-free 10% formalin, then deposited at the bottom of flat-bottomed tubes, embedded in agar to immobilize them, dehydrated, and finally embedded in paraffin. All pancreata and islet samples were sectioned at 5 μm. For one pancreas sample, 80 consecutive sections were performed.

Attachment of islet cells within Cunningham chambers.

Islet cells cultured 24 h in complete CMRL were harvested and injected into poly-l-lysine–coated Cunningham chambers (15). After 1 h at 37°C, chambers were rinsed to remove unattached cells and filled with methanol-free 10% formalin. After 20-min incubation at room temperature, they were rinsed with PBS and stored at 4°C before being used for immunofluorescence.

Immunofluorescence.

Before immunofluorescence, sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated with a series of alcohol solutions of decreasing concentration. Sections and cells attached to Cunningham chambers were then washed with PBS. Antibody dilutions and rinsing steps were performed in PBS. Incubations were done at room temperature, except as indicated below.

For double staining (insulin + glucagon, insulin + somatostatin, or insulin + PP), slides were treated 20 min with 0.5% Triton X-100 and 20 min with 0.1% BSA, at room temperature. Slides were then incubated for 1 h with a mouse anti-glucagon antibody (1:3,000; Sigma), a rabbit anti-somatostatin antibody (1:300; Dako, Carpinteria, CA), or a rabbit anti-PP antibody (1:300; Dako). After rinsing, slides were incubated for 1 h with either an Alexa 488–conjugated anti-mouse antibody (1:500; Invitrogen, Basel, Switzerland) or a fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated anti-rabbit antibody (1:400; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). Then, slides were rinsed and incubated for 1 h with a guinea pig anti-insulin antibody (1:1,000; Dako) and successively for 1 h with a Rhodamine-conjugated anti–guinea pig antibody (1:100; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). For triple staining (insulin, glucagon, and CD34), deparaffinized sections were treated for 10 min at 37°C with a 0.1% trypsin solution, for 20 min with 0.5% Triton X-100, and for 20 min with 0.1% BSA, at room temperature, and incubated successively for 1 h with a mouse anti-CD34 antibody (1:50; Serotec, Oxford, U.K.), for 1 h with a Alexa 488–conjugated anti-mouse antibody (1:500; Invitrogen), for 1 h with rabbit anti-glucagon (1:50; Dako) and guinea pig anti-insulin (1:1,000; Dako) antibodies, and for 1 h with a Rhodamine-conjugated (1:750) anti-rabbit and AMCA conjugated anti–guinea pig antibodies (1:150; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories).

Morphologic analysis and quantifications.

Microscopic sections and islet cells were analyzed with an Axioskop microscope (Zeiss, Feldbach, Germany) equipped with ultraviolet illumination and filters for blue, red, and green fluorescence. Images were captured with an Axiocam color CCD camera (Zeiss) and recorded on computer through the AxioVision software (Zeiss). Isolated cells were also analyzed by confocal microscopy (Zeiss LSM510 Meta) configured for simultaneous analysis of red and green fluorescence. Quantifications on isolated cells were performed by microscope observation. Quantifications on islet and pancreas sections were performed on digital images. Analysis of red and green fluorescence on digital images was performed using the offline MetaMorph imaging software for microscopy (Universal Imaging, West Chester, PA). This software was programmed to automatically quantify red- and green-stained areas within defined regions of interest. Data were expressed as means ± SEM of n different experiments or islets. Differences between means were assessed either by the Student t test and when required by one-way ANOVA. When ANOVA was applied, Scheffé least-significant difference post hoc analysis was used to identify significant differences.

RESULTS

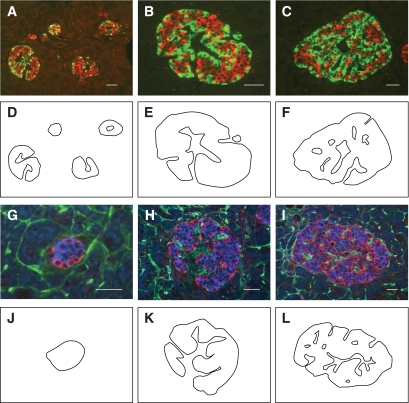

When pancreas sections were double stained for insulin and glucagon, apparently small islets (40–60 μm in diameter) showed a segregated cell type distribution with α-cells localized in the mantle and β-cells in the core of the islets (Fig. 1A and G). In apparently bigger islets (Fig. 1A–C), α-cells were found in the mantle as in 40- to 60-μm–diameter islets, and also along simple or ramified “empty” areas (Fig. 1A–C) present inside these islets. Islets with apparent diameters of 50–100 μm generally displayed one simple empty area (Fig. 1A), whereas islets with apparent diameters larger than 100 μm displayed multiple and/or ramified empty areas (Fig. 1A–C). Labeling for CD34 revealed that vessels surrounded the periphery of islets and localized inside these empty areas, hereafter referred to vascular channels (Fig. 1H and I). Careful examination showed that α-cells were always lining the vascular channels and the mantle region of the islets, and juxtaposed to endothelial cells (Fig. 1G–I). Interestingly, no CD34 staining was observed inside the β-cell bulk, suggesting that vessels did not penetrate the β-cell bulk. Similar observation was made for 40- to 60-μm–diameter islets. Because in this analysis apparently small islets could be tangential sections of bigger islets, we also examined serial sections, which permitted us to explore the thickness of several islets (n = 8) in their entirety. Thus, after a triple immunofluorescence for insulin, glucagon, and CD34, we confirmed that no vascular channel penetrated the core of 40- to 60-μm–diameter islets or the clusters of β-cells in bigger islets.

FIG. 1.

Organization of α- and β-cells in human pancreatic islets. Sections of human pancreata with islets of different sizes were either double-labeled for insulin (red) and glucagon (green) (A–C) or triple-labeled for insulin (blue), glucagon (red), and CD34 (green) (G–I). D–F and J–L: Outlines of endocrine tissue labeled for insulin and glucagon were drawn. Except for the 40- to 60-μm–diameter islets, all islets displayed one or several unstained empty areas (vascular channels) at their core. Most glucagon-expressing cells were located around vascular channels and at the mantle of islets, independent of their size. Insulin-expressing cells seemed clustered into discrete ovoid areas surrounded by α-cells. In triple-labeled sections (G–I), vascular channels displayed staining for CD34, indicating that they contained vessels. Islets shown are representative of at least 200 islets observed on sections from 16 different pancreata. Scale bars, 50 μm. (A high-quality digital representation of this figure is available in the online issue.)

When double staining was performed for insulin and somatostatin or insulin and PP, we observed that δ- and PP-cells had roughly the same topographic position as α-cells (not shown).

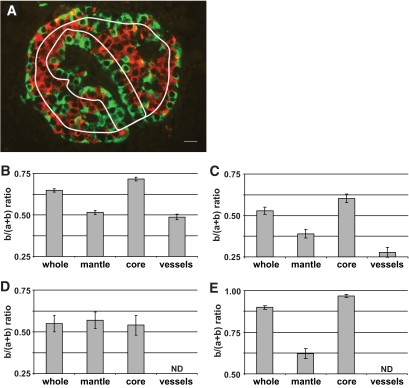

To confirm segregation of α- and β-cells, areas labeled for glucagon (green = a) and insulin (red = b) were quantified in three different subregions of each islet profile. These subregions were 1) the mantle, defined as a region of 20-μm deep that follows the external perimeter of islets, 2) the core, defined as the total islet area minus the 20-μm mantle area, and 3) the vessel area, defined as a region of 20-μm deep that follows the contour of vessels (Fig. 2A). The results expressed as b/(a+b) ratios were 0.71 for the core and 0.50 for the mantle and the vessel area of islets (Fig. 2B), showing that β-cells preferentially localized at the core compared with mantle and vessel area. Considering that single-cell section areas are roughly similar between α- and β-cells, one can extrapolate that the core contains three times more β-cells than α-cells, whereas the mantle and the region around vascular channels contain roughly the same number of α- and β-cells. When subregions were selected with a 10-μm instead of a 20-μm rim, the differences in ratios among subregions were amplified (not shown), correlating with the observation that the α-cells were lining the islet mantle and vessels, as a single layer (∼10 μm). The mean apparent diameter of all islets analyzed here was 154 ± 4 μm (means ± SEM of 255 islets from 21 different pancreata).

FIG. 2.

Distribution of α- and β-cells according to different defined islet subregions. A: Pancreatic islet labeled by immunofluorescence for insulin (red) and glucagon (green); rims (white lines) delimiting mantle and core subregions and one vascular channel area are shown; scale bar, 10 μm. After immunofluorescence, areas labeled for insulin (b) and glucagon (a) were measured and results expressed as b/(a+b) ratio. This ratio was calculated for areas measured in the different subregions (mantle, core, and vessels) and in the whole islets (whole). Analyses were performed on histologic sections from nondiabetic human (B), type 2 diabetic human (C), and control mouse (E) pancreata and cultured isolated human islets (D). Columns are means ± SEM. B: n = 193 islets from 16 pancreata. C: n = 54 islets from five pancreata. D: n = 20 islets from two pancreata. E: n = 50 islets from one pancreas. ND, not determined. (A high-quality digital representation of this figure is available in the online issue.)

When pancreatic islets from type 2 diabetic donors were similarly analyzed, an equivalent pattern of islet cell distribution was observed (Fig. 2C). However, the range of values was lower in diabetic compared with control islets. This last observation is in agreement with published works showing a decrease of β-cell mass in type 2 diabetes (16–19).

We then studied the profile of b/(a+b) values in cultured isolated islets. After enzymatic digestion, the islet vasculature is damaged and cell arrangement is expected to be perturbed after culture. Section analysis of these islets revealed that few structures resembling vascular channels were remaining. Total profile area of these structures was eight times lower in isolated islets compared with profile area of vascular channels in islets in situ. Morphometric analysis indicated similar b/(a+b) ratios between the core and mantle of cultured isolated islets (Fig. 2D).

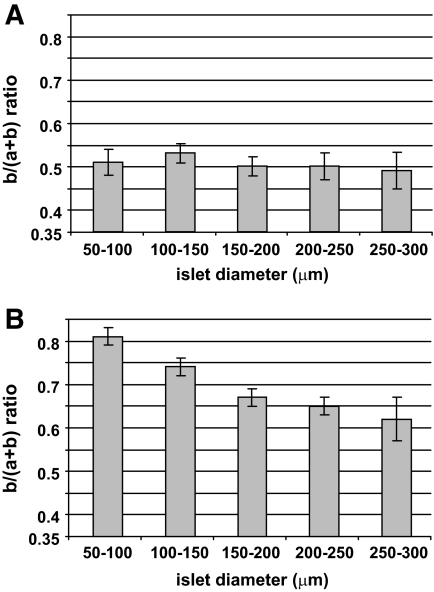

When analysis of control pancreatic islets was performed according to their apparent diameter, b/(a+b) ratios in the mantle remained constant (Fig. 3A), as ratios in the core gradually decreased with the increasing islet apparent diameter (Fig. 3B). This observation confirmed that apparently small islets (50–100 μm in diameter) had a core-mantle organization close to that of rodent islets (Fig. 2D), and that apparently bigger islets had elevated numbers of non–β-cells in their core.

FIG. 3.

Distribution of α- and β-cells according to islet apparent size. Islets from human pancreas sections analyzed in Fig. 2 are shown here according to their apparent diameter. After immunofluorescence, insulin- and glucagon-labeled areas were measured and results expressed as b/(a+b) ratio, where a and b were representing glucagon and insulin labeled areas, respectively. A: b/(a+b) ratio calculated for areas measured in the 20-μm mantle part of islets. B: b/(a+b) ratio calculated for areas measured in the core of the islets. Columns are means ± SEM. n = 39 for islets with 50- to 100-μm diameter, 60 for islets with 100- to 150-μm diameter, 58 for islets with 150- to 200-μm diameter, 24 for islets with 200- to 250-μm diameter, and 12 for islets with 250- to 300-μm diameter.

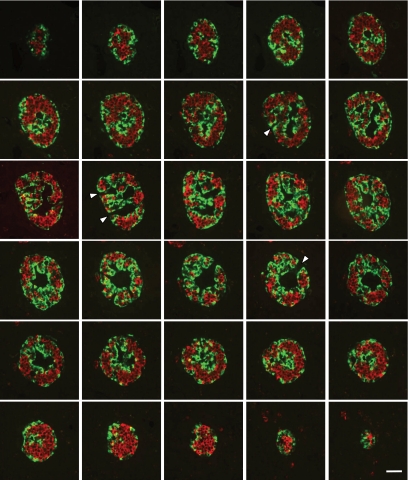

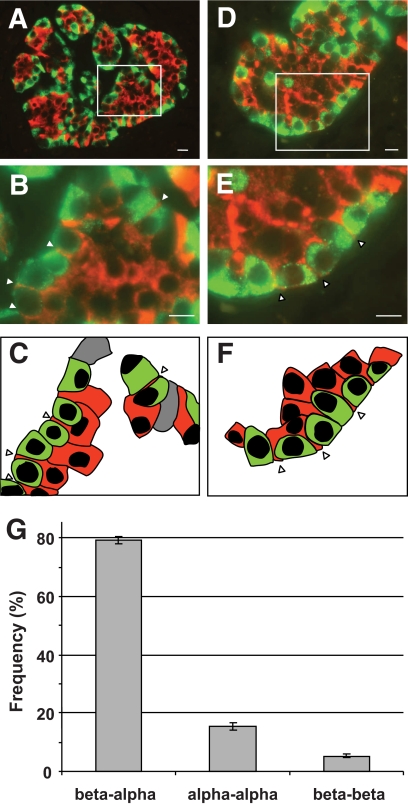

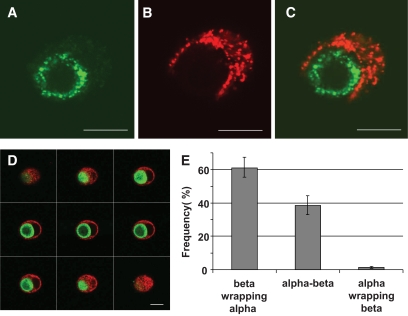

To gain an insight into the islet cell organization, we performed consecutive serial sections through pancreas specimens and a three-dimensional analysis of islets (Fig. 4). It appeared evident that islet cells were not organized into discrete core-mantle subunits as previously described (9,11). Rather, islet cells were organized into a continuous structure, like a folded epithelial plate (board), that spans the three-dimensional (3D) network of the whole islet. The epithelial plate, whose thickness did not vary much, had a triple-laminated section with a central part that contained β-cells and was lined at both sides with α- and other islet cells. Moreover, vessels were juxtaposed at both sides of the epithelial plate structure, invaginating in and following its folds. In 54 islets from five different pancreata, we measured the distance between vascular channels, equivalent to the thickness of the trilaminar plate. The value observed of 42 ± 13 μm (mean ± SD) roughly fits the diameter of the smallest islets. α-Cells, because of their position within the epithelial plate, are exclusively aligned along vessels. β-Cells were also found aligned directly along vessels in alternation with α-cells. Where α-cells were the most numerous, they formed a “fence” between endothelial cells and β-cells. In this case, β-cells appeared to form a second layer of cells over the first layer of α-cells. However a careful examination of these cells revealed that they develop extensions that infiltrated between α-cells and progressed until the surface of endothelial cells (Fig. 5A–F). Confocal microscopic analysis showed that narrow strips of insulin staining between α-cells corresponded to true cytoplasmic extensions and not to insulin released into extracellular compartment. Indeed, confocal analysis revealed that insulin staining between α-cells had a granular pattern similar to that observed elsewhere inside β-cells, and colocalized with actin staining (supplementary Fig. 1, available in an online appendix at http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/cgi/content/full/db09-1177/DC1). As a consequence of this cell organization, the heterologous contacts between α- and β-cells around vessels are most numerous than homologous contacts between β- and α-cells (Fig. 5G). When association between α- and β-cells was assessed in cultured isolated islet cells, we observed many α-cells wrapped by β-cells and rarely the contrary (Fig. 6). Of all α-cells contacting a β-cell, 38 ± 8% (means ± SEM of three experiments) were round and had a perimeter almost completely wrapped by a β-cell. This result revealed a unique plasticity of β-cells, which were able to spread around α-cells, suggesting that this characteristic was intrinsic to β-cells and not dictated by some islet coercions, such as extracellular matrix or islet vasculature.

FIG. 4.

Three-dimensional analysis of human pancreatic islets. Consecutive sections through an entire pancreatic islet labeled for insulin (red) and glucagon (green). Images show that insulin (red)– and glucagon (green)–stained cells are organized into continuous 3-D networks that span the entire islet. Sections at both ends show islet profiles with an apparent similar core-mantle structure to that of 40- to 60-μm–diameter islets. These consecutive images also reveal that vascular channels were in fact continuous ramified structures that were connected in places with the surrounding islet tissue (arrowheads). Image series is representative of 15 different pancreatic islets analyzed from one pancreas. Scale bar, 50 μm. (A high-quality digital representation of this figure is available in the online issue.)

FIG. 5.

Unique association between α- and β-cells in pancreatic islets. Pancreatic islets labeled for glucagon (green) and insulin (red) are shown at low magnification (A and D). Boxed areas are shown at higher magnification in B and E. α- and β-cells lining vascular channels in B are depicted in C. α- and β-cells lining the islet mantle in E are depicted in F. Arrowheads point to cytoplasmic extensions of β-cells that span α-cells. Scale bars, 10 μm in A and D, and 5 μm in B and E. Heterologous contacts between β- and α-cells (beta-alpha) and homologous contacts between α-cells (alpha-alpha) and β-cells (beta-beta) around empty areas were scored. Their relative frequencies are shown in G. Columns are means ± SEM; n = 52 islets from 10 pancreata. (A high-quality digital representation of this figure is available in the online issue.)

FIG. 6.

Unique association between α- and β-cells in cultured islet cells. Human islet cells were isolated and cultured for 24 h. After a double immunofluorescence for insulin (red) and glucagon (green), islet cells were analyzed by confocal microscopy. A–C: Images showing a cell pair composed of one α-cell (A) surrounded by one β-cell (B); the merged image is shown in C. The cell pair shown here is representative of cell pairs observed in different human cell preparations from at least 10 different pancreata. D: One series of consecutive merged images of a cell pair composed of one α-cell (green) surrounded by a β-cell (red). Scale bars, 10 μm. E: All heterologous contacts between α- and β-cells were scored according to their type of association: a β-cell wrapping an α-cell (beta wrapping alpha), neutral apposition between α- and β-cells (alpha-beta), and an α-cell wrapping a β-cell (alpha wrapping beta). Results are shown as relative frequencies and columns are means ± SEM of five islet cell preparations from five different pancreata. From all heterogeneous contacts between α- and β-cells, the percentage of α-cells whose profile was round and perimeter almost completely wrapped by a β-cell as in D was 38 ± 8 (means ± SEM of three experiments). (A high-quality digital representation of this figure is available in the online issue.)

The specimens used to analyze the pancreatic islet architecture were from different regions of the pancreas, including head, body, and tail. We did not observed obvious variations in islet structures according to the regional origin of the pancreas specimens. To further investigate this point, we compared head and tail specimens from the same pancreas (n = 4). Islets with the trilaminar plate structure were observed in both head and tail regions of all pancreata.

DISCUSSION

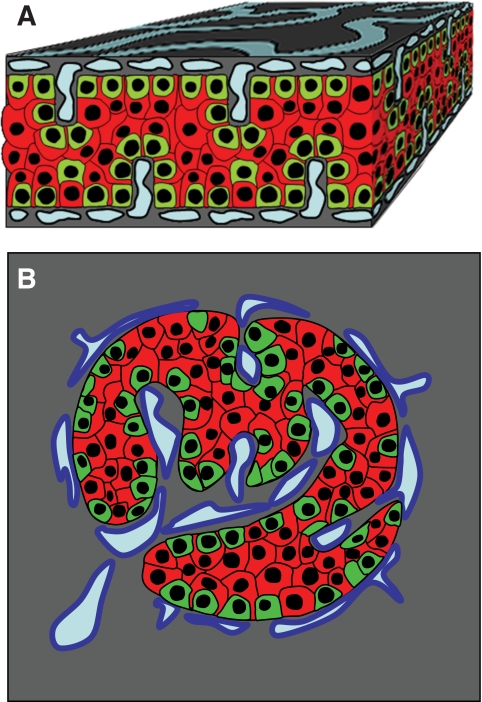

In this morphologic analysis, we show that islet cells are organized into a trilaminar plate comprising one layer of β-cells sandwiched between two α-cell–enriched layers. This structure has a folded pattern and vessels circulate along both of its sides. These observations are schematized in Fig. 7.

FIG. 7.

Model of endocrine cell and vessel organization in human islets. A: α-Cells (green) and β-cells (red) are organized into a thick folded plate lined at both sides with vessels (blue). α-Cells are mostly at the periphery of the plate and in close contact with vessels. β-Cells occupy a more central part of the plate and most of them develop cytoplasmic extension that runs between α-cells and reaches the surface of vessels. B: The plate with adjacent vessels is folded so that it forms an islet.

No evident vascular channel penetrates the central layer of β-cells inside the trilaminar plate, but many vascular channel profiles are found adjacent to the α-cell–enriched layers. Absence of CD34 staining within the β-cell layer strongly suggest absence of endothelial cells. If some endothelial cells unlabeled for CD34 were nevertheless present, they should form tiny and collapsed vessels because no structures resembling typical vessels were observed. There is no doubt that most, if not all, α-cells are in direct contact with vasculature. With regard to β-cells, many are intercalated between α-cells and clearly in contact with blood vessels. Other β-cells sit on a layer of α-cells and display cytoplasmic extensions that run between α-cells to reach the vessel surface as well. Other β-cells are more distant from vessels and doubts persist as to their ability to reach the vasculature. A more meticulous 3D analysis could answer this question. No endothelial cells were observed in the core of 40- to 60-μm–diameter islets presenting a core-mantle organization, suggesting that vessels do not penetrate these islets. But here again, β-cell extensions intercalated between peripheral α-cells were observed, and it is possible that most β-cells reach the surrounding vasculature in this way.

Our description of human islet cell organization is innovative but does not contradict the different views reported so far about the human islet architecture (6,8,9,11,12), including the diametrically opposed opinions describing islets with either segregated or intermingled cell types. Indeed, a clear segregation between α- and β-cells was observed, and this was particularly true in small human islets where α-cells surrounded a core of β-cells. In larger human islets, a kind of cell segregation was also observed because α-cells were confined mostly at the periphery of the trilaminar plate. From another point of view, human islet cells can be considered intermingled, because we clearly showed that intercellular contacts between α- and β-cells predominate. This is certainly a consequence of the trilaminar organization and cytoplasmic extensions of β-cells that intercalate between α-cells. This is not the case in rodent islets where the higher degree of cell segregation clearly favors β- and α-cell homologous contacts.

The potential physiological significance of heterologous contacts between α- and β-cells is suggested by studies showing that glucagon positively affected insulin release (20,21). In this respect, we recently demonstrated that insulin secretion from individual β-cells was increased when they were in contact with α-cells (22). These results, combined with those showing that heterologous contacts predominate in human islets, suggest that glucagon is a more potent regulator of insulin secretion in human than in rodent islets.

Heterologous interactions between β- and α-cells in human islets are not only frequent but also unusual, because β-cells most often wrap the neighboring α-cells. This behavior of β-cells toward α-cells was also observed in vitro in cultured isolated islet cells, demonstrating that it is innate to cells and not commanded by some islet constraints. The molecular mechanisms that account for this phenomenon have not yet been studied. Most likely, cytoskeleton and adhesion molecules expressed by islet cells may play a role. A physiological relevance of this unique plasticity of β-cells is possible, especially considering that glucose-induced insulin secretion in vitro is improved in spreading β-cells compared with round-shaped β-cells (23) and that cytoskeleton plays a role in insulin secretion (24). Cytoskeleton organization could be modified in β-cells wrapping α-cells and spreading β-cells. It remains to be demonstrated whether this modification has a direct impact on insulin secretion.

Islets within pancreata of type 2 diabetic donors have roughly the same structure as islets from nondiabetic donors. Indeed, we have found that the associations between β- and α-cells were roughly similar in type 2 diabetic and nondiabetic islets, suggesting that the β-cell dysfunction observed in type 2 diabetes is not related to a clear abnormality of islet cell organization. Certainly, more studies are required to understand whether a more subtle defect in cell organization is involved. Our quantitative analysis demonstrated that β-cell mass relative to α-cell mass was substantially decreased in type 2 diabetic islets. These results are in agreement with some previous reports showing a decrease of the absolute β-cell mass or of the volume of islets relative to the volume of pancreas in type 2 diabetic subjects (16–19).

We have shown that the unique organization of islet cells observed within human pancreata is not maintained in cultured isolated islets. This is not surprising considering the insults sustained by islets during the isolation procedure, including disruption of vascularization, enzymatic digestion of extracellular matrix, and mechanical shaking of the tissues. Islet morphology could be also affected by culture. Indeed intercellular contacts are under the control of molecular events influenced by environmental factors. Finally, the handling, fixation, and paraffin embedding of islets may also affect the cellular structure of the islets. It would be interesting to investigate whether islet architecture is maintained in freshly isolated islets and the real effect is of the culture on islet morphology. Many components of the medium could affect islet morphology in vitro. Among these components, there are the insulin secretagogues, such as glucose, that have been shown to affect expression of adhesion molecules, including E-cadherin and integrins, in islet cells (23,25). In rodents, dissociated islet cells readily reaggregate in culture and after a few days are able to form pseudoislets with a core-mantle organization similar to that of native islets. This indicates that in rodents, information that decides the islet architecture is foremost provided by islet cells themselves (26,27). Our observations suggest that islet cells by themselves are not responsible for the unique cellular organization of human islets. In humans, the more complex organization of islets could involve more complex mechanisms. The role of vessels and extracellular matrix components in the maintenance of human islet architecture remains to be investigated. Furthermore, it will be particularly interesting to determine whether islet morphology is restored after transplantation and whether the unique arrangement between α- and β-cells is critical for the function of transplanted islets.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (3200BO-120376). Human islets were obtained using a grant from the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (31-2008-416).

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

We thank Corinne Sinigaglia and David Matthey-Doret for their excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Orci L, Unger RH. Functional subdivision of islets of Langerhans and possible role of D cells. Lancet 1975;2:1243–1244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gannon M, Ray MK, Van Zee K, Rausa F, Costa RH, Wright CV. Persistent expression of HNF6 in islet endocrine cells causes disrupted islet architecture and loss of beta cell function. Development 2000;127:2883–2895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bosco D, Orci L, Meda P. Homologous but not heterologous contact increases the insulin secretion of individual pancreatic B-cells. Exp Cell Res 1989;184:72–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Samols E, Stagner JI. Intra-islet regulation. Am J Med 1988;85:31–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samols E, Stagner JI. Islet somatostatin: microvascular, paracrine, and pulsatile regulation. Metabolism 1990;39:55–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonner-Weir S, O'Brien TD. Islets in type 2 diabetes: in honor of Dr. Robert C. Turner. Diabetes 2008;57:2899–2904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bosco D, Meda P, Morel P, Matthey-Doret D, Caille D, Toso C, Bühler LH, Berney T. Expression and secretion of alpha1-proteinase inhibitor are regulated by proinflammatory cytokines in human pancreatic islet cells. Diabetologia 2005;48:1523–1533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cabrera O, Berman DM, Kenyon NS, Ricordi C, Berggren PO, Caicedo A. The unique cytoarchitecture of human pancreatic islets has implications for islet cell function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006;103:2334–2339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erlandsen SL, Hegre OD, Parsons JA, McEvoy RC, Elde RP. Pancreatic islet cell hormones distribution of cell types in the islet and evidence for the presence of somatostatin and gastrin within the D cell. J Histochem Cytochem 1976;24:883–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grube D, Deckert I, Speck PT, Wagner HJ. Immunohistochemistry and microanatomy of the islets of Langerhans. Biomed Res 1983;4(Suppl.):25–36 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orci L. The microanatomy of the islets of Langerhans. Metabolism 1976;25:1303–1313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brissova M, Fowler MJ, Nicholson WE, Chu A, Hirshberg B, Harlan DM, Powers AC. Assessment of human pancreatic islet architecture and composition by laser scanning confocal microscopy. J Histochem Cytochem 2005;53:1087–1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bucher P, Mathe Z, Morel P, Bosco D, Andres A, Kurfuest M, Friedrich O, Raemsch-Guenther N, Buhler LH, Berney T. Assessment of a novel two-component enzyme preparation for human islet isolation and transplantation. Transplantation 2005;79:91–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ricordi C, Lacy PE, Finke EH, Olack BJ, Scharp DW. Automated method for isolation of human pancreatic islets. Diabetes 1988;37:413–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cunningham AJ, Szenberg A. Further improvements in the plaque technique for detecting single antibody-forming cells. Immunology 1968;14:599–600 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Butler AE, Janson J, Bonner-Weir S, Ritzel R, Rizza RA, Butler PC. Beta-cell deficit and increased beta-cell apoptosis in humans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2003;52:102–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klöppel G, Löhr M, Habich K, Oberholzer M, Heitz PU. Islet pathology and the pathogenesis of type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus revisited. Surv Synth Pathol Res 1985;4:110–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saito K, Yaginuma N, Takahashi T. Differential volumetry of A, B and D cells in the pancreatic islets of diabetic and nondiabetic subjects. Tohoku J Exp Med 1979;129:273–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sakuraba H, Mizukami H, Yagihashi N, Wada R, Hanyu C, Yagihashi S. Reduced beta-cell mass and expression of oxidative stress-related DNA damage in the islet of Japanese type II diabetic patients. Diabetologia 2002;45:85–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crockford PM, Porte D, Jr, Wood FC, Jr, Williams RH. Effect of glucagon on serum insulin, plasma glucose and free fatty acids in man. Metabolism 1966;15:114–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huypens P, Ling Z, Pipeleers D, Schuit F. Glucagon receptors on human islet cells contribute to glucose competence of insulin release. Diabetologia 2000;43:1012–1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wojtusciszyn A, Armanet M, Morel P, Berney T, Bosco D. Insulin secretion from human beta cells is heterogeneous and dependent on cell-to-cell contacts. Diabetologia 2008;51:1843–1852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bosco D, Meda P, Halban PA, Rouiller DG. Importance of cell-matrix interactions in rat islet beta-cell secretion in vitro: role of α6β1 integrin. Diabetes 2000;49:233–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tomas A, Yermen B, Min L, Pessin JE, Halban PA. Regulation of pancreatic beta-cell insulin secretion by actin cytoskeleton remodelling: role of gelsolin and cooperation with the MAPK signalling pathway. J Cell Sci 2006;119:2156–2167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bosco D, Rouiller DG, Halban PA. Differential expression of E-cadherin at the surface of rat beta-cells as a marker of functional heterogeneity. J Endocrinol 2007;194:21–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cirulli V, Halban PA, Rouiller DG. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha modifies adhesion properties of rat islet B cells. J Clin Invest 1993;91:1868–1876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rouiller DG, Cirulli V, Halban PA. Uvomorulin mediates calcium-dependent aggregation of islet cells, whereas calcium-independent cell adhesion molecules distinguish between islet cell types. Dev Biol 1991;148:233–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]