Abstract

The proinflammatory cytokine interferon-γ (IFNγ) alters neuronal connectivity via selective regressive effects on dendrites but the signaling pathways that mediate this effect are poorly understood. We recently demonstrated that signaling by Rit, a member of the Ras family of GTPases, modulates dendritic growth in primary cultures of sympathetic and hippocampal neurons. In this study we investigated a role for Rit signaling in IFNγ-induced dendritic retraction. Expression of a dominant negative Rit mutant inhibited IFNγ-induced dendritic retraction in cultured embryonic rat sympathetic and hippocampal neurons. In pheochromacytoma cells and hippocampal neurons, IFNγ caused rapid Rit activation as indicated by increased GTP binding to Rit. Silencing of Rit by RNA interference suppressed IFNγ-elicited activation of p38 MAP kinase in pheochromacytoma cells, and pharmacological inhibition of p38 MAP kinase significantly attenuated the dendrite-inhibiting effects of IFNγ in cultured sympathetic and hippocampal neurons without altering STAT1 activation. These observations identify Rit as a downstream target of IFNγ and suggest that a novel IFNγ-Rit-p38 signaling pathway contributes to dendritic retraction and may, therefore, represent a potential therapeutic target in diseases with a significant neuroinflammatory component.

Keywords: dendrite retraction, hippocampal neuron, interferon-γ, p38 MAP kinase, Rit, sympathetic neuron

Dendritic retraction is critical for synaptic refinement during neurodevelopment and experience-dependent synaptic remodeling (Purves et al. 1986; Lichtman and Colman 2000). However, excessive or inappropriate dendritic retraction is thought to contribute to the functional deficits associated with trauma (Yawo 1987; Brannstrom et al. 1992), neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease (Patt et al. 1991; Coleman and Yao 2003) and neurodevelopmental disorders including Down’s syndrome, schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorders (Takashima et al. 1989; McGlashan and Hoffman 2000; Zoghbi 2003). Despite its physiologic and pathologic importance, the molecular mechanisms that regulate dendritic retraction remain poorly characterized (Miller and Kaplan 2003; Goldberg 2004; Parrish et al. 2007). While growth factor deprivation (Yawo 1987; Purves et al. 1988; Gorski et al. 2003) and decreased neuronal activity (Miller and Kaplan 2003; Lohmann and Wong 2005) have been associated with dendritic retraction, the identification of specific ligands that inhibit dendritic growth and/or promote dendritic retraction suggests that dendritic pruning is not just a default process but may also be triggered by active signaling mechanisms. Ligands shown to cause regressive dendritic events include corticosteroids (McEwen 2001; Joels et al. 2007), excitatory amino acids such as glutamate (Mattson 1988; Monnerie and Le Roux 2007), the neuropeptides pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) and vasoactive intestinal peptide (Drahushuk et al. 2002) and proinflammatory cytokines (Guo et al. 1999; Morikawa et al. 2000; Kim et al. 2002; Gilmore et al. 2004). With respect to proinflammatory cytokines, we have shown that interferon-γ (IFNγ) inhibits dendritic growth and triggers dendritic retraction in cultured sympathetic and hippocampal neurons without compromising cell viability or altering axonal morphology (Kim et al. 2002), suggesting that IFNγ exerts direct regressive effects on a restricted subcellular compartment of neurons.

The key signaling events that regulate IFNγ effects on dendritic morphology are only partially understood. We previously demonstrated that IFNγ stimulates the phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) in cultured sympathetic neurons and that the inhibitory effects of IFNγ on BMP-induced dendritic growth are significantly attenuated but not completely blocked by expression of dominant negative (dn) STAT1 (Kim et al. 2002). These findings are consistent with recent studies indicating that while the canonical JAK-STAT signaling pathway is most closely associated with IFNγ signaling, the coordinated activation of multiple distinct signaling cascades is required to generate appropriate cellular responses to IFNγ and related cytokines (Platanias 2005). However, signaling cascades that function in addition to STAT1 activation to mediate the regressive effects IFNγ on dendritic morphology have yet to be identified.

Rit belongs to a subgroup of Ras-related GTPases (Reuther and Der 2000). Originally cloned from mouse (Lee et al. 1996) and human (Shao et al. 1999) retina, Rit has subsequently been detected in embryonic, postnatal and adult brain (Lee et al. 1996; Wes et al. 1996) and in primary cultures of rat sympathetic and hippocampal neurons (Spencer et al. 2002; Lein et al. 2007). Like other Ras GTPases, Rit interactions with downstream effector proteins require GTP binding, and Rit activity is modulated by external cues that influence the relative ratio of GTP- versus GDP-bound Rit (Reuther and Der 2000). Downstream targets of Rit identified thus far include Ras-responsive promoter elements (Shao et al. 1999), Ral GTPase (Shao and Andres 2000) and both ERK and p38 MAP kinase signaling pathways (Shi and Andres 2005). External cues that modulate GTP loading of Rit include nerve growth factor (NGF) (Shi and Andres 2005), PACAP38 (Shi et al. 2006), and bone morphogenetic protein 7 (BMP7) (Lein et al. 2007). Interestingly, NGF, PACAP38, and BMP7 (Higgins et al. 1997; McAllister 2000) as well as many of the known downstream targets of Rit (Huber et al. 2003; Miller and Kaplan 2003; Goldberg 2004; Lalli and Hall 2005) are implicated in controlling axonal and dendritic growth, suggesting that Rit signaling contributes to the regulation of neuronal cell shape. In support of this hypothesis, we recently demonstrated that expression of a constitutively active (ca) Rit mutant promoted axonal but inhibited dendritic growth whereas a dnRit mutant inhibited axonal but enhanced dendritic growth in cultured sympathetic and hippocampal neurons (Lein et al. 2007). While a role for Rit signaling in dendritic retraction was not investigated in this previous study, the observation that caRit phenocopied the inhibitory effects of IFNγ on BMP-induced dendritic growth suggested the possibility that Rit activation contributes to IFNγ-induced dendritic retraction. In this study, we tested this novel hypothesis by determining whether: 1) IFNγ increases Rit GTP loading in neural cells; 2) modulating Rit signaling interferes with IFNγ-induced dendritic retraction in cultured embryonic rat sympathetic and hippocampal neurons; and 3) Rit-dependent regulation of STAT1, ERK1/2 or p38 MAP kinase signaling cascades influence IFNγ-induced dendritic retraction. Our observations suggest that a novel Rit-p38 MAP kinase signaling cascade operates in parallel with STAT1 signaling to mediate IFNγ effects on neuronal connectivity.

Materials and Methods

Materials

The construction and characterization of recombinant adenovirus vectors that express either 3XFlag-wildtype (WT) or green fluorescent protein (Ad-GFP) or co-express GFP and either constitutively active RitQ79L (Ad-caRit) or dominant negative RitS35N (Ad-dnRit) have been previously described (Spencer et al. 2002; Shi and Andres 2005; Lein P et al. 2007). Recombinant rat IFNγ was obtained from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ) and recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-7 (BMP7) was generously provided by Curis (Cambridge, MA). The p38 MAP kinase inhibitor 4-(4-Fluorophenyl)-2-(4-methylsulfinyl phenyl)-5-(4-pyridyl) 1H-imidazole commonly known as SB203508 was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI) and prepared as a 1000× stock in DMSO before diluting directly into tissue culture medium to yield final concentrations of 10 µM. Previous studies have demonstrated that DMSO at 1:1000 does not alter hippocampal (Howard et al. 2003; Lein et al. 2007) or sympathetic (Howard et al. 2005; Lein et al. 2007) morphogenesis and does not inhibit caRit effects on neurite outgrowth of PC6 (Spencer et al. 2002) or SH-SY5Y (Hynds et al. 2003) cells.

Tissue culture, infection and transfection

Sympathetic neurons were dissociated from the superior cervical ganglia (SCG) of perinatal Holtzman rats (Harlan Sprague-Dawley, Rockford, IL) as previously described (Higgins et al. 1991). Cells were plated onto poly-D-lysine (100 µg/ml, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) coated glass coverslips and maintained in a serum-free medium containing β-NGF (100 ng/ml, Harlan Bioproducts, Indianapolis, IN). The antimitotic cytosine-β-D-arabinoside (1 µM, Sigma) was added to the medium of all cultures for 48 h beginning 24 h after plating to eliminate all non-neuronal cells. Dendritic growth was induced in sympathetic cultures by adding BMP7 (50 ng/ml) to the culture medium (Lein et al. 1995). Hippocampal neurons were dissociated from the hippocampi of embryonic (E18) Holtzman rats using previously described methods (Howard et al. 2003). Dissociated cells were plated onto glass coverslips precoated with poly-D-lysine (100 µg/ml; Sigma) and laminin (6 µg/ml; Invitrogen, San Diego, CA) and maintained in serum-free Neurobasal medium with B27 supplements (Invitrogen). To study the effects of Rit on dendritic growth and retraction, sympathetic or hippocampal neuronal cultures were infected with adenoviral vectors expressing GFP alone or co-expressing GFP and dnRit in the absence or presence of IFNγ. Sympathetic neurons were infected 5 days after initiating treatment with BMP7. Hippocampal neurons were infected with adenoviral vectors 4 days after plating. Infection efficiencies ranged from 20 to 30%.

The PC6 strain of the pheochromacytoma 12 (PC12) cell line was the generous gift of Dr. T. Vanaman (University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY). The cells were maintained in DMEM (Invitrogen) containing 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated FBS (HyClone, Salt Lake City, UT), 5% (v/v) heat-inactivated horse donor serum (Invitrogen), 100 µg/ml streptomycin, and 100 unit/ml penicillin at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. PC6 cells were transfected with Effectene (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) as previously described (Shi and Andres 2005).

Morphological analyses

Cultures were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and dual labeled using polyclonal antibodies that react with GFP (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and monoclonal antibodies (mAb) that react with the dendrite-selective cytoskeletal protein microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2, SMI-52; Sternberger Immunocytochemicals, Baltimore, MD). Neuronal morphology was digitized in neurons immunopositive for both GFP and MAP-2 using SPOT imaging software (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI) as previously described (Lein et al. 2007).

Western blot analyses

Cultured hippocampal neurons (4 days in vitro) were either infected with Ad-GFP or Ad-caRit for 16 h or treated with IFNγ (30 ng/ml) in the absence or presence of SB203580 (10 µM) for 30 min, then lysed in buffer A (20 mM Tris, pH 7.6, 250 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM EDTA, 3 mM EGTA, 20 mM, β-glycerol phosphate, 1 mM vanadate, 50 mM KF and 1× protease inhibitor mixture from Calbiochem, San Diego, CA). Lysates were centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 10 min and the protein concentration of the supernatant determined using the Bradford assay (BioRad, Hercules, CA). Equal amounts of protein from each lysate were separated by SDS-PAGE (7%), transferred to PVDF membranes and reacted with antibodies that recognize both phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated STAT1 (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) or with mAb that specifically recognizes STAT1 phosphorylated at Ser 727 (pSTAT1, Cell Signaling Technology). Blots were also probed using antibodies specific for α–tubulin (Sigma). To visualize antigen-antibody complexes, blots were reacted with Infrared Dye-conjugated secondary antibodies (Rockland Immunochemicals, Gilbertsville, PA), and bands quantified using the Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE). To determine the requirement of Rit in IFNγ-mediated signaling, PC6 cells were transfected with either a rat Rit specific small hairpin RNA interference construct pSuper-Neo/GFP-shRit208 (shRit208) or a scrambled siRNA construct (shCTR) lacking a specific target in the rat genome as control (1.5 µg) (Shi and Andres, 2005), and the transfected cells enriched by G418 (400 µg/ml) selection for 48 h before being subjected to starvation with serum-free DMEM medium for 5 h. The cells were subsequently stimulated with IFNγ (50 ng/ml) and lysed with kinase lysis buffer [Hepes (pH 7.4), 20 mM; NaCl, 150 mM; KF, 50 mM; β-glycerol phosphate, 50 mM; EGTA (pH 8.0), 2 mM; Na3VO4, 2 mM; Triton X-100, 1%; glycerol, 10% and 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (Calbiochem)]. The detergent-soluble fraction was then resolved by SDS-PAGE. The phosphorylation levels of ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK were analyzed by immunoblotting with phospho-specific ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK antibodies (Cell Signaling), while cellular actin levels served as a loading control.

Rit-GTP precipitation assays

GST fusion proteins containing the Rit binding domain of RGL3 (residues 610–709) were expressed and purified, and Rit activation was assessed as previously described (Shi and Andres 2005). Briefly, PC6 cells seeded in 6-well plates were transfected with 1 µg of 3xFlag-Rit-WT and incubated for an additional 36 h to allow maximal gene expression. Cells were then grown in serum-free DMEM for an additional 5 h. Hippocampal neurons were transfected with 3xFlag-Rit-WT at the time of plating using the Amaxa nucleofection system as instructed by the manufacturer (Amaxa Biosystems, Gaithersburg, MD) as previously described (Lein et al. 2007). Cultures were maintained in Neurobasal medium supplemented with B27 for 72 h prior to treatment. Cell monolayers were washed once in ice-cold PBS and lysed in GST-pull down assay buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 250 mM NaCl, 50 mM KF, 50 mM β-glycerolphosphate, 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, and 1x protease cocktail) with sonication on ice. GST resin (10 µg of the appropriate fusion protein/20 µl glutathione beads) was added to Rit expressing cell lysates (200 µg total protein) in a total volume of 1 ml, incubated with rotation for 1 h at 4°C, and the resin recovered by centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C. The GST-RGL3-RBD pellets were washed once with GST-pull down buffer, twice with GST-pull down buffer supplemented to 500 mM NaCl, and twice again with GST-pull down buffer. Bound GTP-Rit was detected by immunoblot analysis using anti-Flag monoclonal antibody. To determine the effect of IFNγ on Rit activation, PC6 cells and hippocampal neurons expressing 3xFlag-Rit-WT were stimulated with recombinant human IFNγ at the times and concentrations indicated in the figure legend.

Statistical analyses

Within each experiment, 30–50 neurons from 2–3 coverslips were analyzed per experimental condition. Experiments were repeated in cultures from at least three separate dissections. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was assessed by Student’s t test or one-way ANOVA. If ANOVA indicated significant effects at p < 0.05, differences between groups were determined by Tukey’s post hoc test.

Results

Rit signaling contributes to the regressive dendritic effects of IFNγ in sympathetic neurons

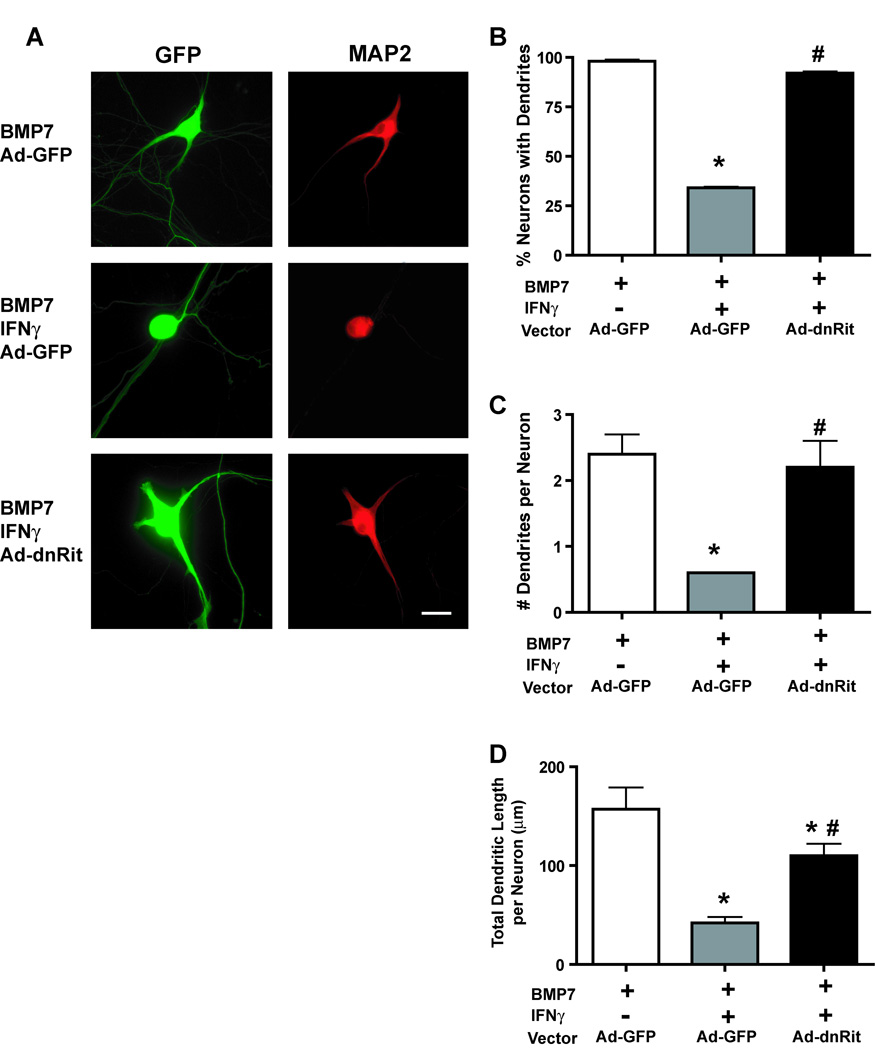

Sympathetic neurons extend only axons when cultured in the absence of non-neuronal cells in serum-free medium containing optimal NGF, but the addition of BMP7 causes them to also form dendrites (Lein et al. 1995). In earlier studies we demonstrated that when added simultaneously with BMP7, IFNγ inhibits BMP-induced dendritic growth, and when added to cultures previously exposed to BMP7, IFNγ induces dendritic retraction in sympathetic neurons (Kim et al. 2002). We employed the latter exposure paradigm to test the hypothesis that Rit activation contributes to IFNγ-induced dendritic retraction. Sympathetic neurons were initially treated with BMP7 (50 ng/ml) for 5 days to induce dendritic growth and then infected with adenovirus expressing GFP alone (Ad-GFP) or co-expressing GFP and dominant negative RitS35N (Ad-dnRit). Infection with these recombinant viruses does not adversely influence cell viability in cultured sympathetic neurons and that expression of Ad-dnRit does not potentiate BMP-induced dendritic growth at the maximally effective BMP concentration of 50 ng/ml (Lein et al. 2007). IFNγ (30 ng/ml) was added to a subset of cultures immediately following infection, and dendritic growth was analyzed 3 days post-infection. IFNγ caused dendritic retraction in neurons infected with the control vector Ad-GFP (Fig 1A), which was evident as a significant decrease in the percentage of neurons with dendrites (Fig 1B), the number of dendrites per neuron (Fig 1C) and the total dendritic length per neuron (Fig 1D) in the IFNγ-treated Ad-GFP neurons relative to Ad-GFP neurons not exposed to IFNγ. The expression of dnRit significantly inhibited IFNγ-induced dendritic retraction (Fig 1) as evidenced by an almost complete blockade of the regressive effects of IFNγ on the percentage of dendrite bearing neurons (Fig 1B) and dendrite number per neuron (Fig 1C) and a significant attenuation of IFNγ-induced decreases in total dendritic length per neuron (Fig 1D).

Figure 1. Inhibiting Rit activation blocks IFNγ-induced dendrite retraction in cultured sympathetic neurons.

(A) Fluorescence micrographs of sympathetic neurons immunostained for GFP and MAP2. Sympathetic neurons were initially treated with BMP7 (50 ng/ml) for 5 days to induce dendritic growth, and then infected with adenovirus expressing GFP alone (Ad-GFP) or co-expressing GFP and dominant-negative RitS35N (Ad-dnRit). IFNγ (30 ng/ml) was added to a subset of cultures immediately following infection. Cultures were fixed 3 days after infection and immunostained for GFP and MAP2, a cytoskeletal protein localized to the somatodendritic compartment. Sympathetic neurons infected with Ad-GFP and exposed to BMP7 alone extended several MAP2 immunopositive processes. Addition of IFNγ caused dendritic retraction in neurons expressing Ad-GFP. Expression of dnRit significantly attenuated dendrite retraction in cultures exposed to IFNγ. Dendritic growth was quantified in neuronal cells dual labeled for GFP and MAP2 with respect to the percentage of neurons with dendrites (B), the number of dendrites per neuron (C) and the total length of the dendritic arbor per neuron (D). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n > 80 neurons per experimental group). * Significantly different from Ad-GFP neurons exposed to BMP7 at p < 0.05; # significantly different from Ad-GFP neurons treated with BMP7 and IFNγ at p < 0.05.

Rit signaling inhibits IFNγ-induced dendritic retraction in hippocampal neurons

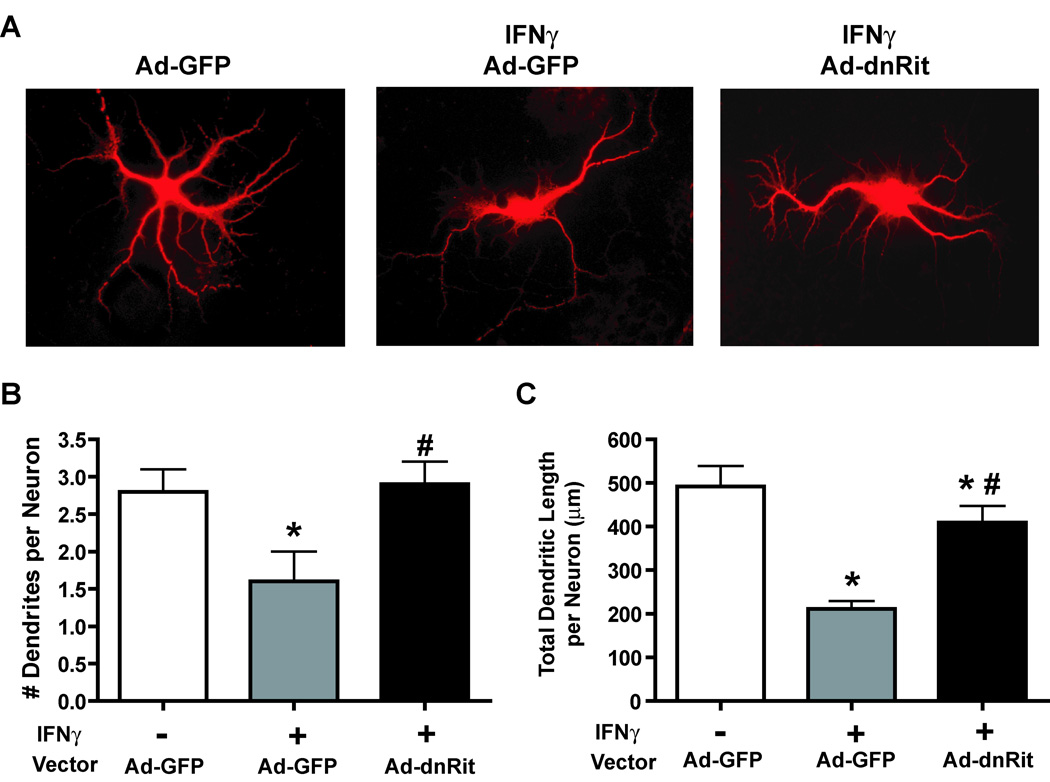

To determine whether Rit signaling also contributes to the regressive effects of IFNγ on dendritic growth in CNS neurons, we examined the effects of expressing dnRit on IFNγ-induced dendritic retraction in cultured hippocampal neurons. These neurons differ from sympathetic neurons in that they form dendrites in culture in the absence of exogenous BMPs (Higgins et al. 1997). Hippocampal neurons were infected 4 days after plating with Ad-GFP or Ad-dnRit. IFNγ (30 ng/ml) added to a subset of cultures immediately following infection and dendritic morphology analyzed 3 days post-infection. These experimental manipulations do not adversely impact cell viability in cultured hippocampal neurons (Lein et al. 2007). Exposure to IFNγ reduced hippocampal dendritic growth in Ad-GFP cultures (Fig 2) causing an approximate 50% reduction in the number of dendrites (Fig 2B) and a greater than 60% decrease in total dendritic length (Fig 2C). Expression of dnRit, however, blocked the inhibitory effect of IFNγ on dendritic outgrowth (Fig 2A), as evidenced by a significant attenuation of IFNγ-mediated decreases in the number (Fig 2B) and total length (Fig 2C) of dendrites.

Figure 2. Inhibiting Rit activation blocks IFNγ-induced dendrite retraction in cultured hippocampal neurons.

(A) Fluorescence micrographs of GFP-positive hippocampal neurons immunostained for MAP2 (MAP2 immunoreactivity is shown). Hippocampal neurons were infected with adenovirus expressing GFP alone (Ad-GFP) or co-expressing GFP and dominant-negative RitS35N (Ad-dnRit) 4 days after plating. IFNγ (30 ng/ml) was added to a subset of cultures immediately following infection. Cultures were fixed 3 days after infection and immunostained for both GFP (green) and MAP2 (red). IFNγ caused dendritic retraction in hippocampal neurons infected with Ad-GFP. Expression of dnRit significantly inhibited the dendrite retracting activity of IFNγ. Dendritic growth was quantified in neuronal cells immunopositive for both GFP and MAP2 with respect to the number of dendrites per neuron (B) and the total length of the dendritic arbor per neuron (C). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n > 80 neurons per experimental group). *Significantly different from Ad-GFP neurons maintained in the absence of IFNγ at p < 0.05; # significantly different from Ad-GFP neurons treated with IFNγ at p < 0.05.

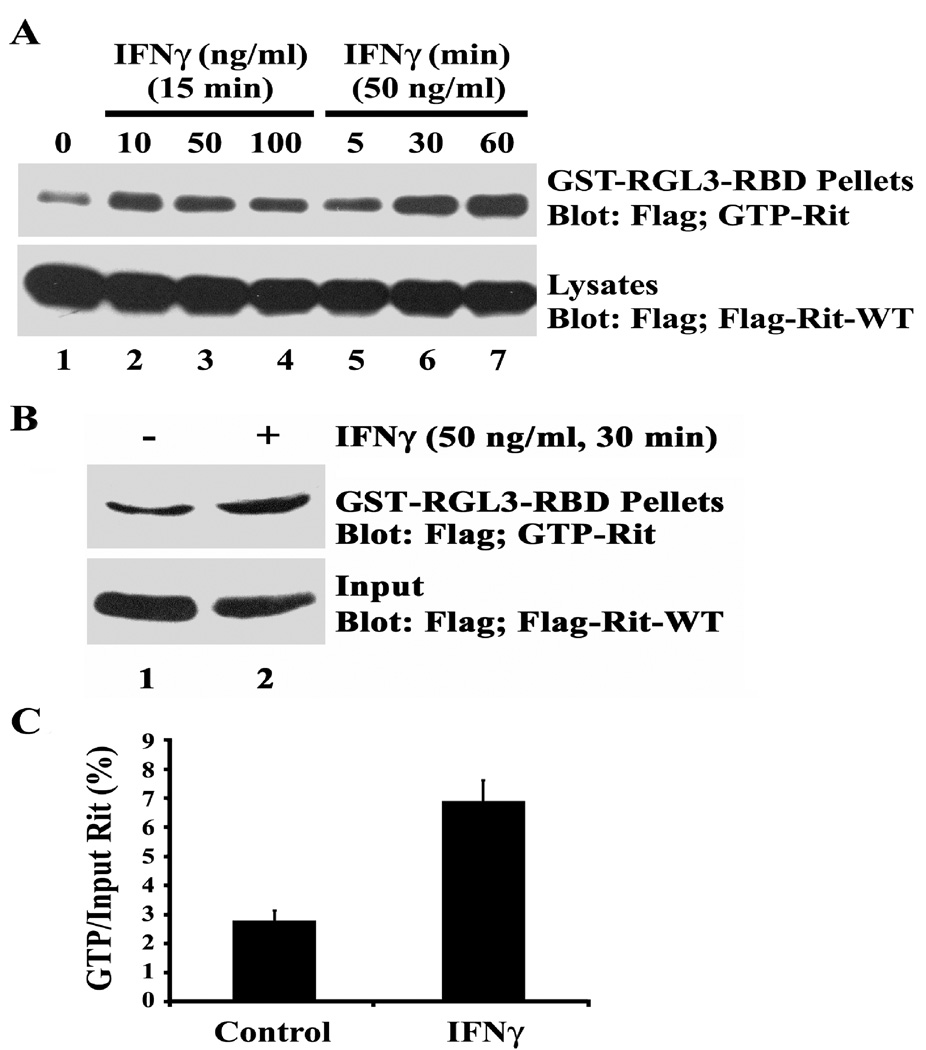

IFNγ activates Rit in PC6 cells and in hippocampal neurons

To further support the hypothesis that IFNγ signaling triggers dendritic retraction in part by activating Rit, we next determined whether IFNγ increases the levels of GTP-bound Rit. Rit-GTP loading assays are technically difficult in primary cultures of sympathetic neurons because of low levels of endogenous Rit protein and low infection/transfection efficiencies. Pheochromacytoma cells are often used as models of sympathetic neurons for biochemical studies, thus, we performed Rit-GTP pull-down assays using PC6 cells expressing 3xFlag-Rit-WT as described previously (Shi and Andres 2005; Lein et al. 2007). Serum-starved PC6 cells contained barely detectable levels of GTP-bound Rit but stimulation with IFNγ resulted in a time- and concentration-dependent increase in the level of GTP-Rit while Rit protein levels remained constant (Fig 3A). Activation of Rit was rapid, with GTP-Rit detected within 5 min following stimulation, and remained elevated for more than 60 min. Rit-GTP pull-down assays were repeated using hippocampal neurons transfected with the 3xFlag-Rit-WT construct using nucleofection at plating which resulted in 60–80% transfection efficiency. These analyses revealed that treatment with IFNγ (50 ng/ml for 60 min) also significantly increased cellular levels of GTP-Rit in cultured hippocampal neurons (Fig 3B, C).

Figure 3. IFNγ activates Rit in PC6 cells and in cultured hippocampal neurons.

GST pull-down assays using GST-RGL3-RBD agarose were performed with lysates obtained from PC6 cells (A) or hippocampal neurons (B) expressing 3xFlag-Rit-WT. The levels of GTP-bound Rit were determined by immunoblot analysis using anti-Flag monoclonal antibody. (A) PC6 cells were serum starved for 5 h to reduce basal Rit-GTP levels prior to stimulation with increasing concentrations of IFNγ for 15 min or with IFNγ at 50 ng/ml for 0, 5, 30 or 60 min. Note that Rit-GTP levels increase following exposure to IFNγ in a time- and concentration-dependent manner. (B) Hippocampal neurons were transfected with 3xFlag-Rit-WT at the time of plating, maintained in serum-free Neurobasal medium supplemented with B27 for 72 h then either left untreated or exposed to IFNγ at 50 ng/ml for 30 min. Rit is activated in hippocampal neurons treated with IFNγ as illustrated in a representative blot (B) and confirmed by densitometry (C) in which values obtained for Rit-GTP are normalized to total Flag-Rit-WT values (data presented as the mean ± SEM, n = 2 per experimental condition). In experiments using either PC6 cells or hippocampal neurons, similar results were obtained in two separate experiments performed using two different sets of cultures.

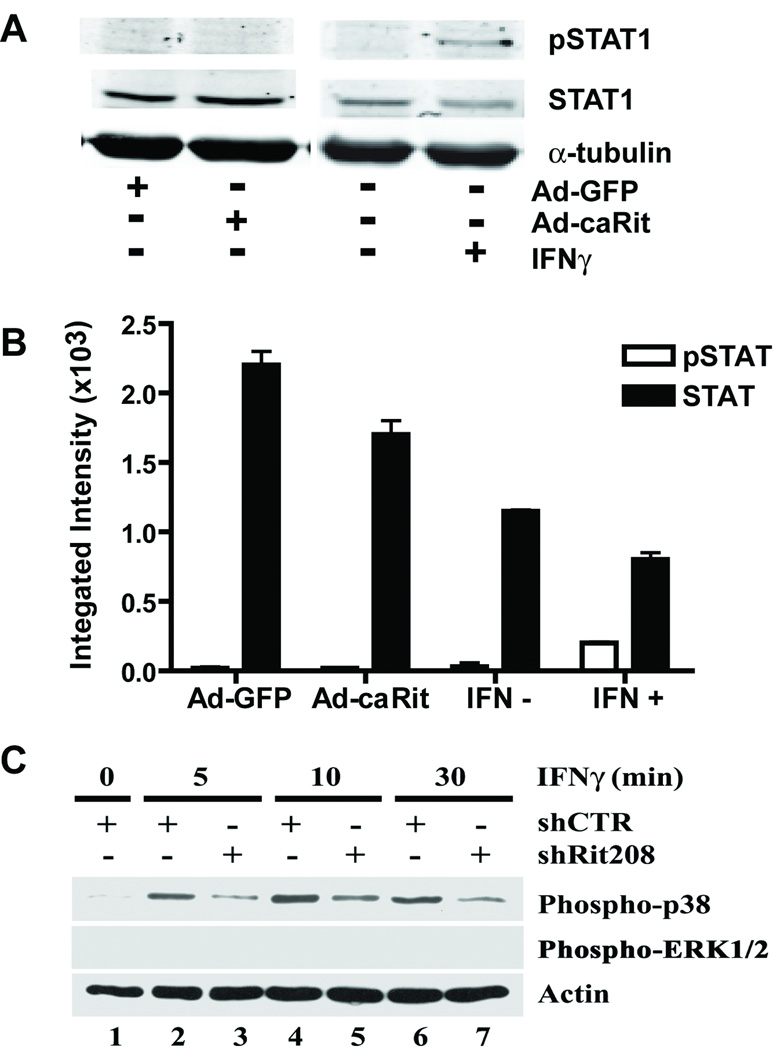

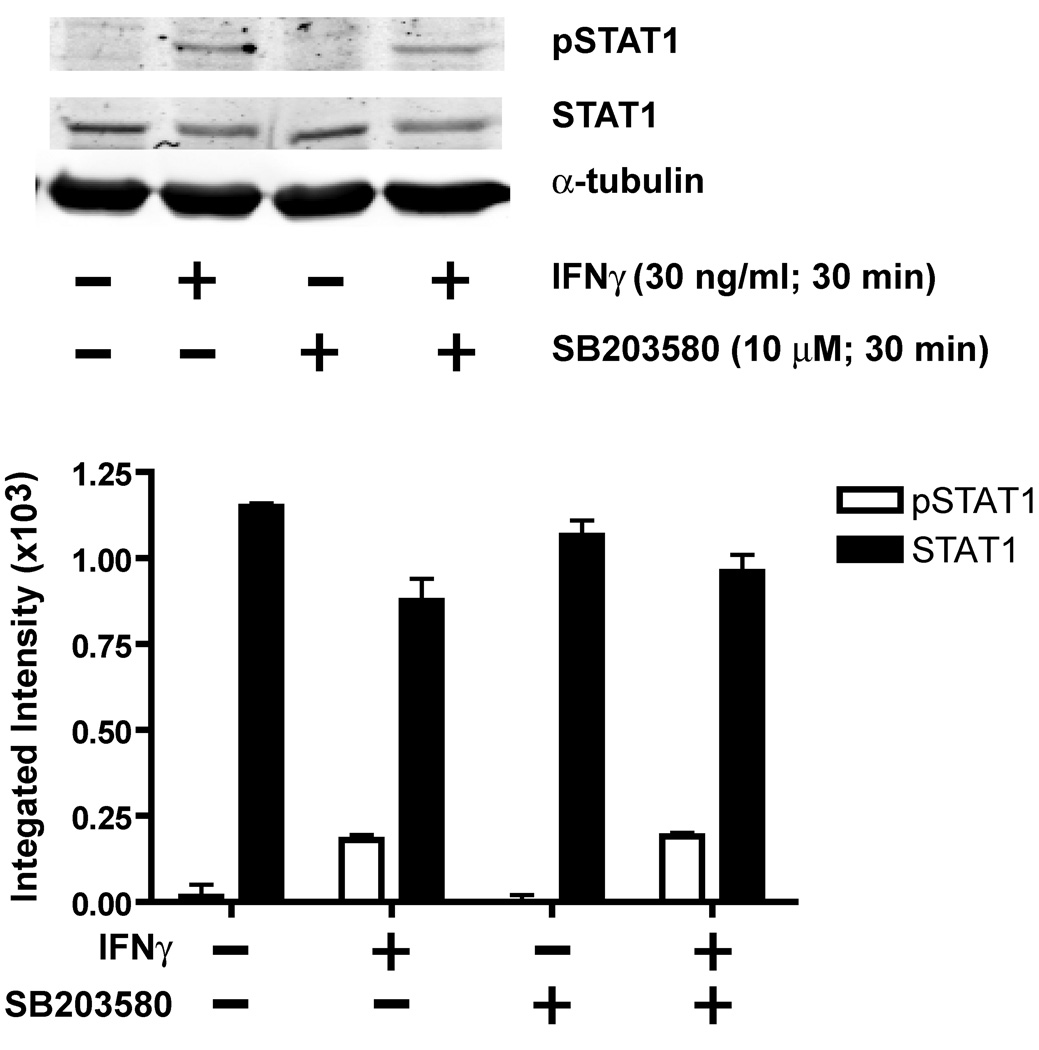

Rit does not stimulate STAT1 but is required for IFNγ-mediated p38 activation

Many cellular responses to IFNγ are mediated by activation of the Janus kinase (JAK) pathway resulting in activation of STAT1, a central transcription regulator of cytokine signaling (Farrar and Schreiber 1993; Bach et al. 1997; Schindler et al. 2007), and we previously demonstrated that IFNγ-induced dendrite retraction is partially mediated by STAT1 activation (Kim et al. 2002). Of the various covalent modifications proposed to modulate STAT1 activity, phosphorylation of STAT1 on Ser727 is particularly important in regulating transcriptional activity (Schindler et al. 2007); therefore, to determine whether Rit signaling is involved in STAT1 activation, we examined whether expression of a constitutively active RitQ79L mutant (Ad-caRit) (Spencer et al. 2002; Shi and Andres 2005; Lein et al. 2007) increased Ser727 phosphorylation of STAT1 in hippocampal neurons. Although IFNγ stimulation increased Ser727 phosphorylation, expression of Ad-caRit failed to stimulate STAT1 Ser727 phosphorylation in primary cultures of hippocampal neurons (Fig 4A and 4B).

Figure 4. Rit activates p38, but neither ERK1/2 nor STAT signaling.

(A and B) Hippocampal neurons were infected with adenovirus expressing GFP alone (Ad-GFP) or co-expressing GFP and constitutively active RitQ79L (Ad-caRit) 4 days after plating. Cell lysates were collected 16 h post-infection and analyzed by immunoblotting using mAb that specifically recognize phosphorylated Ser727 on STAT1 (pSTAT1) or polyclonal antibodies that react with both phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated STAT1 (STAT1). A representative Western blot (A) and corresponding densitometric analysis (B) of pSTAT1 and total STAT1 indicate that treatment with IFNγ but not expression of caRit activates STAT1 as indicated by increased levels of pSTAT1. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n=3 blots obtained in 3 separate experiments performed using cultures from 3 separate dissections). (C) IFNγ activates p38 but not ERK1/2 in PC6 cells. PC6 cells were transfected with either shCTR or shRit208 RNAi vectors and subjected to G418 selection for 48 h. Cells were then serum starved (serum-free DMEM, 5 h) prior to stimulation with IFNγ (50 ng/ml). Whole cell lysates were prepared and levels of activated p38 and ERK1/2 determined by phosphospecific immunoblotting. A representative Western blot for activated p38 and ERK1/2 MAP kinase levels is shown. Anti-actin immunoblotting was used to confirm equivalent protein loading. Note that IFNγ fails to stimulate ERK MAP kinase signaling in PC6 cells and that Rit silencing inhibits IFNγ-mediated p38 activation.

Since our previous studies demonstrated a role for ERK MAP kinase signaling in Rit-mediated control of dendritic morphology (Lein et al. 2007), we next asked whether ERK signaling was involved in IFNγ-mediated dendritic retraction. Surprisingly, IFNγ failed to stimulate ERK activation in either PC6 cells (Fig 4C) or in cultured sympathetic neurons (see supplemental data, Fig S1), as monitored by immunoblotting with phosphospecific ERK1/2 antibody. These data indicate that ERK1/2 signaling is not involved in this IFNγ-dependent signaling pathway.

The p38 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase cascade plays particularly important roles in IFNγ signaling (Platanias 2005), and in PC6 cells, Rit is involved in p38 activation by either NGF or PACAP38 (Shi and Andres 2005; Shi et al. 2006). Therefore, we asked whether IFNγ activated p38 and if so, whether Rit signaling was involved. For these studies we used a Rit-targeted short hairpin interfering RNA vector (shRit208). We have previously shown that in PC6 cells, shRit208 potently and selectively reduces Rit protein levels by >80%, whereas a control short hairpin RNA with no predicted target in the rat genome (shCTR) has no effect on Rit expression (Shi et al. 2006). Activation of p38 MAP kinase following IFNγ stimulation was monitored in shRit208 and shCTR transfected PC6 cells by immunoblotting with phosphospecific antibodies for p38. In cells expressing shCTR, IFNγ-induced p38 activation was detected within 5 min and remained elevated for 30 min (Fig 4C, lanes 2, 4, and 6). Rit silencing by expression of shRit208 potently inhibited p38 activation (Fig. (4C, lanes 3, 5, and 7). Quantification of these data by densitometry confirmed that Rit knockdown inhibited IFNγ-induced p38 activation by >70% (data not shown).

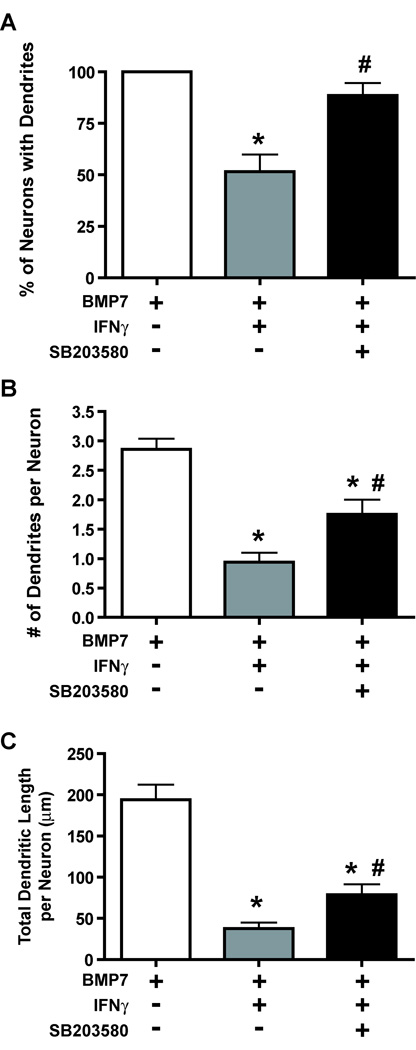

IFNγ-induced dendritic retraction is partially blocked by inhibition of p38 MAP kinase signaling

The observation that Rit silencing disrupted IFNγ-mediated p38 activation in PC6 cells raised the question of whether p38 MAP kinase signaling was necessary for IFNγ-induced dendritic retraction. In previous studies, we have shown that exposure of sympathetic neurons to SB203580 (10 µM), a p38 MAP kinase inhibitor, had no effect on BMP7-induced dendritic growth (Kim et al. 2004). However, when sympathetic neurons pretreated with BMP7 for 5 days to induce dendritic growth were exposed to IFNγ (30 ng/ml) in the presence of SB203580 (10 µM), inhibition of p38 MAP kinase signaling significantly attenuated IFNγ-induced dendritic retraction (Fig 5). SB203580 treatment almost completely blocked IFNγ effects on the percentage of neurons with dendrites (Fig 5A) and significantly increased both the number of dendrites (Fig 5B) and total dendritic length (Fig 5C) per neuron in cultures exposed to IFNγ.

Figure 5. Pharmacological inhibition of p38 kinase attenuates IFNγ-induced dendrite retraction in cultured sympathetic neurons.

Sympathetic neurons were pretreated with BMP7 (50 ng/ml) for 5 days to induce dendritic growth. Subsequently, they were divided into 3 groups that were treated for an additional 3 days with: 1) BMP7 alone; 2) BMP7 and IFNγ (30 ng/ml) or 3) BMP7 and IFNγ in the presence of the p38 kinase inhibitor SB203580 (10 µM). Dendritic growth was quantified in neuronal cells immunopositive for MAP2 with respect to the percentage of neurons with dendrites (A), the number of dendrites per neuron (B), and the total dendritic length per neuron (C). Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n ≥ 80 neurons per experimental group). *Significantly different from BMP7 alone at p < 0.05; # significantly different from BMP7 and IFNγ at p < 0.05.

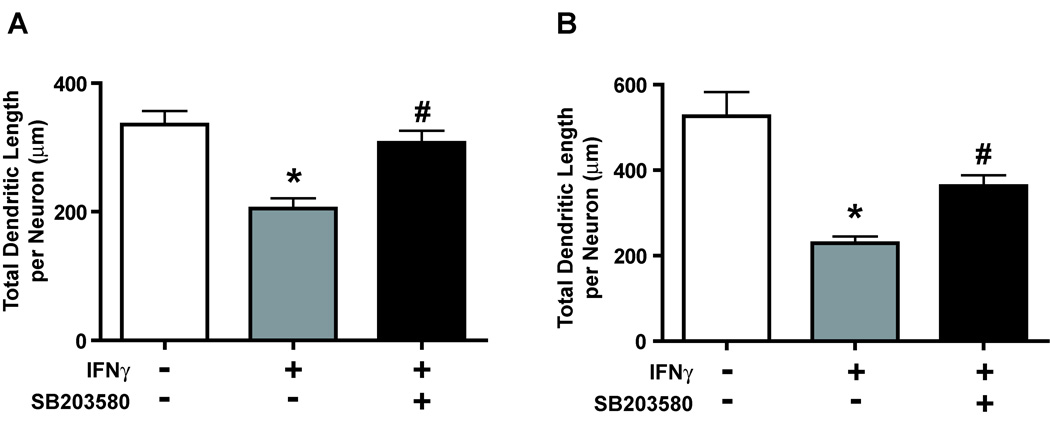

Pharmacological inhibition of p38 MAP kinase signaling also significantly attenuated the dendrite-retracting activity of IFNγ in hippocampal neurons (Fig 6). Total dendritic length per neuron was increased in cultures exposed simultaneously to IFNγ and SB203580 (10 µM) relative to cultures exposed to IFNγ alone regardless of whether IFNγ was added to neurons with relatively immature dendritic arbors (Fig 6A) or neurons with more established dendritic arbors (Fig 6B). However, pharmacological inhibition of p38 MAP kinase cascade signaling did not alter either STAT1 expression or IFNγ-mediated STAT1 phosphorylation in hippocampal neurons (Fig 7), supporting a STAT1-independent role for p38 MAP kinase signaling in IFNγ signaling.

Figure 6. IFNγ-induced dendrite retraction in cultured hippocampal neurons is significantly attenuated by a p38 kinase inhibitor.

Hippocampal neurons were treated for 3 days with IFNγ (30 ng/ml) in the absence or presence of the p38 kinase inhibitor SB203580 (10 µM). Treatments were initiated on either day 4 in vitro to block initial stages of dendritic growth (A) or on day 7 in vitro to cause retraction of existing dendrites (B). Cultures were fixed and immunostained for the dendritic marker MAP2 and dendritic growth quantified with respect to the total dendritic length per neuron. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n ≥ 80 neurons per experimental group). * Significantly different from BMP7 alone at p < 0.05; # significantly different from BMP7 and IFNγ at p < 0.05.

Figure 7. IFNγ-mediated STAT activation does not require p38 signaling.

On day 7 in vitro, hippocampal neurons were treated with IFNγ (30 ng/ml) for 30 min in the absence or presence of the p38 MAP kinase inhibitor, SB203580 (10 µM). Cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting using phosphospecific antibodies for STAT1. A representative Western blot (top panel) and corresponding densitometric analysis (bottom panel) of STAT1 phosphorylated on Ser727 (pSTAT) and total (phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated) STAT1 indicate that SB203580 does not block IFNγ activation of STAT1. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n=3 blots obtained in 3 separate experiments performed using cultures from 3 separate dissections).

Discussion

We recently identified Rit as a potential convergence point for BMP and NGF signaling pathways involved in controlling axonal and dendritic growth (Lein et al. 2007). Herein, we provide novel data identifying Rit as a signaling molecule involved in regulating IFNγ-induced dendritic retraction in primary cultures of sympathetic and hippocampal neurons. Specifically we demonstrate that: 1) IFNγ increases Rit GTP loading in PC6 cells and hippocampal neurons (Fig 3); 2) expression of dnRit significantly attenuates IFNγ-induced dendritic retraction in both sympathetic (Fig 1) and hippocampal neurons (Fig 2); and 3) a novel Rit-p38 signaling pathway contributes to IFNγ effects on dendritic dynamics (Fig 4, Fig 5 and Fig 6).

Numerous Ras GTPases have been identified in regulating neuronal cell shape (Arendt et al. 2004; Gartner et al. 2004; Schwamborn and Puschel 2004; Jaworski et al. 2005; Kumar et al. 2005; Yoshimura et al. 2006), raising the possibility of off-target effects associated with the use of dnRit (Feig 1999). However, only Rit and one other family member, Rap2, have been implicated in signaling pathways that contribute to dendritic retraction. Similar to our observations with caRit (Lein et al. 2007), expression of caRap2 was recently reported to decrease the length and complexity of dendritic branches in cultured hippocampal neurons (Fu et al. 2007); however, in contrast to caRit which significantly increased axonal length and branching (Lein et al. 2007), caRap2 was reported to also decrease the length and complexity of axonal branches (Fu et al. 2007). The different profile of morphogenic effects triggered by Rit and Rap2 suggests differential activation of downstream effector pathways and/or differences in subcellular distribution or duration of activation of the Ras GTPases (Reuther and Der 2000).

A critical question addressed in these studies was the identification of downstream effectors of Rit signaling in IFNγ-induced dendritic growth. Canonical IFNγ signaling involves activation of the JAK-STAT pathway, whose function is essential for transcriptional activation of IFNγ-sensitive genes (Platanias 2005). Our previous studies (Kim et al. 2002) demonstrated that IFNγ stimulates both phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of STAT1 and that expression of dnSTAT1 significantly attenuated IFNγ-induced dendritic retraction. Thus, a surprising finding of this study was that while Rit signaling contributed to IFNγ-induced dendritic retraction, Rit was not required for STAT1 phosphorylation (Fig 4). Instead, Rit signaling was necessary for regulating p38 MAP kinase activation downstream of IFNγ (Fig 4), similar to our previous studies demonstrating the importance of Rit in NGF- and PACAP38-mediated p38 activation (Shi and Andres 2005; Shi et al. 2006). The p38 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase cascade is particularly important in both transcription-dependent and transcription-independent IFNγ signaling (Platanias 2005). Interestingly, while inhibition of p38 MAP kinase signaling has been shown to suppress IFNγ activated sequence (GAS)-controlled gene transcription (Uddin et al. 2000), recent studies have established that p38 MAP kinases do not phosphorylate STAT1 in response to IFNγ (Kovarik et al. 1999). Similarly, we observed that pharmacological inhibition of p38 MAP kinase signaling did not block IFNγ-mediated phosphorylation of STAT1 in hippocampal neurons (Fig 7). When considered in light of the rapid kinetics of Rit activation by IFNγ (Fig 3), which are consistent with an IFNγ receptor-initiated signaling pathway directly modulating Rit activity as we previously reported for NGF activation of Rit via TrkA signaling (Shi and Andres 2005), these data suggest that a novel IFNγ-Rit-p38 MAP kinase signaling pathway functions in parallel with canonical IFNγ-JAK-STAT signaling in neuronal cells.

The functional relevance of Rit activation of p38 MAP kinase signaling in mediating IFNγ effects on dendritic morphology is suggested by our observation that pharmacological inhibition of p38 MAP kinase significantly attenuated IFNγ-induced dendritic retraction in both sympathetic (Fig 5) and hippocampal (Fig 6) neurons. Because IFNγ is not usually detected in the brain (Traugott and Lebon 1988; Fabry et al. 1994), the physiologic significance of Rit-p38 MAP kinase signaling is not clear. However, our previous report that Rit is involved in p38 activation by PACAP38 (Shi et al. 2006) coupled with evidence demonstrating that PACAP38 inhibits BMP-induced dendritic growth in cultured sympathetic neurons (Drahushuk et al. 2002) certainly suggests this possibility. Our data do, however, support a critical role for Rit-p38 MAP kinase signaling in mediating the regressive effects of IFNγ on neuronal connectivity and further suggest a molecular mechanism by which IFNγ inhibits the dendrite promoting activity of BMP7 (Kim et al. 2002).

The finding that IFNγ-dependent signaling did not result in ERK activation (Fig 4 and Fig S1) was unexpected since earlier studies had shown that Rit functions downstream of BMP and NGF to promote axonal growth but inhibit dendritic growth via activation of the ERK MAP kinase cascade (Lein et al. 2007). The organization of higher-order molecular complexes by scaffolding proteins is one mechanism known to confer specificity to MAP kinase signaling (Morrison and Davis 2003; Kolch 2005). The ability of Rit to promote distinct MAP kinase pathway activation, even within the same cell, reinforces the notion that unique signaling complexes may be involved in specifying Rit-mediated downstream signaling in response to unique external cues. The nature of the molecular machinery that couples Rit to p38 in IFNγ-stimulated neurons remains to be characterized.

Additional downstream signaling molecules likely to mediate the effects of Rit signaling on dendritic retraction include the Rho GTPases, which regulate actin and microtubule dynamics (Miller and Kaplan 2003; Van Aelst and Cline 2004). The effects of Rit signaling on dendritic retraction are most closely mimicked by RhoA (Govek et al. 2005), suggesting functional crosstalk between Rit and RhoA signaling pathways. While activated Rit has not been shown to stimulate Rho GTPase activity, there is evidence that the related Rin GTPase can modulate the activity of RhoA and other Rho family GTPases (Hoshino et al. 2005). In addition, the Par3/Par6 polarity complex is known to regulate dendritic spine morphogenesis through the spatially and temporally regulated activation of Rho family GTPases by recruitment of specific guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) or GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) (Zhang and Macara 2006, 2008). Rit is known to associate with the PAR-3/Par-6 polarity complex (Hoshino et al. 2005; Rudolph et al. 2007), and modulation of Par complex activity may provide a unique mechanism for controlling the spatiotemporal regulation of Rho family GTPases. Future studies are needed to determine whether Rit signaling regulates Rho GTPase function, and whether the Par3/Par6 complex or p38 MAP kinase signaling pathways are required.

IFNγ plays a critical role in viral clearance from the CNS (Binder and Griffin 2001) and chronic viral infections, such as those associated with HIV infection, lead to long-term IFNγ upregulation (Fuchs et al. 1991; Fan et al. 1993). Such chronic infections are also associated with dendritic atrophy (Masliah et al. 1997; Everall et al. 1999; Montgomery et al. 1999). It is, therefore, possible that IFNγ exerts dual effects in the response to viral infection: it promotes clearance of virions but also contributes to pathology, particularly dementia, by causing dendritic retraction. The potential dual nature of IFNγ effects is further illustrated by evidence suggesting that IFNγ can promote neuronal cell survival (Chang et al. 1990) but that elevated IFNγ expression (Kristensson et al. 1994; Silverstein et al. 1997; Lau and Yu 2001; Li et al. 2001; Shi et al. 2005; Brown 2006) occurs coincident with dendritic retraction (Sumner and Watson 1971; Purves 1975; Yawo 1987; Flood and Coleman 1990; Patt et al. 1991; Kudo et al. 1993; Park et al. 1996; Zoghbi 2003) in neurodegenerative diseases, neurodevelopmental disorders and acute inflammatory reactions triggered by trauma, stroke and axotomy. The identification of a novel Rit-p38 MAP kinase signaling pathway that functions in parallel with the canonical JAK-STAT signaling pathway to mediate IFNγ-induced dendritic retraction suggests the potential for developing therapeutic approaches that differentially influence these dual IFNγ signaling pathways to enhance the beneficial effects of IFNγ while attenuating its adverse effects.

Supplementary Material

Sympathetic neurons were initially treated with BMP7 (50 ng/ml) for 5 days to induce dendritic growth, and then treated with IFNγ (30 ng/ml) for 30 min. Whole cell lysates were prepared and levels of activated ERK1/2 determined by phosphospecific immunoblotting. A representative Western blot for activated ERK1/2 (phospho-ERK1/2) and total ERK1/2 is shown; anti-actin immunoblotting was used to confirm equivalent protein loading. Phosphorylated ERK1/2 are detected in control cultures treated with vehicle (PBS) as would be expected because sympathetic cultures are grown in the presence of NGF (Lein et al. 2007). Treatment with IFNγ fails to stimulate ERK1/2 above these control levels. Similar results were obtained using cell lysates prepared using cultures obtained from 3 independent dissections.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the NIH NINDS (grants NS045103 to D.A.A. and NS046649 to P.J.L) and by the COBRE program of the National Center for Research Resources (grant P20RR20171 to DAA). We thank Melissa Moholt-Siebert (Oregon Health & Science University) for technical assistance and Dr. Lauren Courter (Oregon Health & Science University) for comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Abbreviations used in text

- BMP

bone morphogenetic protein

- ca

constitutively active

- dn

dominant negative

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- IFNγ

interferon-γ

- JAK

Janus activated kinase

- MAP2

microtubule-associated protein 2

- MAP kinase

mitogen activated protein kinase

- NGF

nerve growth factor

- PACAP

pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide

- RNAi

RNA interference

- SCG

superior cervical ganglia

- STAT1

signal transducer and activator of transcription 1

- WT

wildtype

References

- Arendt T, Gartner U, Seeger G, Barmashenko G, Palm K, Mittmann T, Yan L, Hummeke M, Behrbohm J, Bruckner MK, Holzer M, Wahle P, Heumann R. Neuronal activation of Ras regulates synaptic connectivity. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:2953–2966. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816X.2004.03409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach EA, Aguet M, Schreiber RD. The IFN gamma receptor: a paradigm for cytokine receptor signaling. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:563–591. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder GK, Griffin DE. Interferon-gamma-mediated site-specific clearance of alphavirus from CNS neurons. Science. 2001;293:303–306. doi: 10.1126/science.1059742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brannstrom T, Havton L, Kellerth JO. Changes in size and dendritic arborization patterns of adult cat spinal alpha-motoneurons following permanent axotomy. J Comp Neurol. 1992;318:439–451. doi: 10.1002/cne.903180408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AS. Prenatal infection as a risk factor for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2006;32:200–202. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JY, Martin DP, Johnson EM., Jr Interferon suppresses sympathetic neuronal cell death caused by nerve growth factor deprivation. J Neurochem. 1990;55:436–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb04155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman PD, Yao PJ. Synaptic slaughter in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24:1023–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drahushuk K, Connell TD, Higgins D. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide and vasoactive intestinal peptide inhibit dendritic growth in cultured sympathetic neurons. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6560–6569. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06560.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everall IP, Heaton RK, Marcotte TD, Ellis RJ, McCutchan JA, Atkinson JH, Grant I, Mallory M, Masliah E. Cortical synaptic density is reduced in mild to moderate human immunodeficiency virus neurocognitive disorder. HNRC Group. HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center. Brain Pathol. 1999;9:209–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1999.tb00219.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabry Z, Raine CS, Hart MN. Nervous tissue as an immune compartment: the dialect of the immune response in the CNS. Immunol Today. 1994;15:218–224. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90247-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan J, Bass HZ, Fahey JL. Elevated IFN-gamma and decreased IL-2 gene expression are associated with HIV infection. J Immunol. 1993;151:5031–5040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrar MA, Schreiber RD. The molecular cell biology of interferon-gamma and its receptor. Annu Rev Immunol. 1993;11:571–611. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.003035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feig LA. Tools of the trade: use of dominant-inhibitory mutants of Ras-family GTPases. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:E25–E27. doi: 10.1038/10018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flood DG, Coleman PD. Hippocampal plasticity in normal aging and decreased plasticity in Alzheimer's disease. Prog Brain Res. 1990;83:435–443. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)61267-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Z, Lee SH, Simonetta A, Hansen J, Sheng M, Pak DT. Differential roles of Rap1 and Rap2 small GTPases in neurite retraction and synapse elimination in hippocampal spiny neurons. J Neurochem. 2007;100:118–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs D, Moller AA, Reibnegger G, Werner ER, Werner-Felmayer G, Dierich MP, Wachter H. Increased endogenous interferon-gamma and neopterin correlate with increased degradation of tryptophan in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Immunol Lett. 1991;28:207–211. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(91)90005-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartner U, Alpar A, Seeger G, Heumann R, Arendt T. Enhanced Ras activity in pyramidal neurons induces cellular hypertrophy and changes in afferent and intrinsic connectivity in synRas mice. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2004;22:165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore JH, Jarskog LF, Vadlamudi S, Lauder JM. Prenatal infection and risk for schizophrenia: IL-1beta, IL-6 and TNFalpha inhibit cortical neuron dendrite development. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2004;29:1221–1229. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg JL. Intrinsic neuronal regulation of axon and dendrite growth. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14:551–557. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorski JA, Zeiler SR, Tamowski S, Jones KR. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor is required for the maintenance of cortical dendrites. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6856–6865. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-17-06856.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goslin K, Asmussen H, Banker G. Culturing Nerve Cells. 2nd Edition. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1998. Rat hippocampal neurons in low-density culture; pp. 339–370. [Google Scholar]

- Govek EE, Newey SE, Van Aelst L. The role of the Rho GTPases in neuronal development. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1–49. doi: 10.1101/gad.1256405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X, Chandrasekaran V, Lein P, Kaplan PL, Higgins D. Leukemia inhibitory factor and ciliary neurotrophic factor cause dendritic retraction in cultured rat sympathetic neurons. J Neurosci. 1999;19:2113–2121. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-06-02113.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins D, Lein PJ, Osterhout DJ, Johnson MI. Tissue culture of mammalian autonomic neurons. In: Banker G, Goslin K, editors. Culturing Nerve Cells. 1st Edition. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1991. pp. 177–206. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins D, Burack M, Lein P, Banker G. Mechanisms of neuronal polarity. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1997;7:599–604. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(97)80078-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshino M, Yoshimori T, Nakamura S. Small GTPase proteins Rin and Rit Bind to PAR6 GTP-dependently and regulate cell transformation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:22868–22874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411592200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard AS, Fitzpatrick R, Pessah I, Kostyniak P, Lein PJ. Polychlorinated biphenyls induce caspase-dependent cell death in cultured embryonic rat hippocampal but not cortical neurons via activation of the ryanodine receptor. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2003;190:72–86. doi: 10.1016/s0041-008x(03)00156-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard AS, Bucelli R, Jett DA, Bruun D, Yang D, Lein PJ. Chlorpyrifos exerts opposing effects on axonal and dendritic growth in primary neuronal cultures. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;207:112–124. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber AB, Kolodkin AL, Ginty DD, Cloutier JF. Signaling at the growth cone: ligand-receptor complexes and the control of axon growth and guidance. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2003;26:509–563. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.010302.081139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynds DL, Spencer ML, Andres DA, Snow DM. Rit promotes MEK-independent neurite branching in human neuroblastoma cells. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:1925–1935. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaworski J, Spangler S, Seeburg DP, Hoogenraad CC, Sheng M. Control of dendritic arborization by the phosphoinositide-3'-kinase-Akt-mammalian target of rapamycin pathway. J Neurosci. 2005;25:11300–11312. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2270-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joels M, Karst H, Krugers HJ, Lucassen PJ. Chronic stress: implications for neuronal morphology, function and neurogenesis. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2007;28:72–96. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim IJ, Beck HN, Lein PJ, Higgins D. Interferon gamma induces retrograde dendritic retraction and inhibits synapse formation. J Neurosci. 2002;22:4530–4539. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-11-04530.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim IJ, Drahushuk KM, Kim WY, Gonsiorek EA, Lein P, Andres DA, Higgins D. Extracellular signal-regulated kinases regulate dendritic growth in rat sympathetic neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3304–3312. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3286-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingham PJ, McLean WG, Walsh MT, Fryer AD, Gleich GJ, Costello RW. Effects of eosinophils on nerve cell morphology and development: the role of reactive oxygen species and p38 MAP kinase. Am J Physiol. 2003;285:L915–L924. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00094.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolch W. Coordinating ERK/MAPK signalling through scaffolds and inhibitors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:827–837. doi: 10.1038/nrm1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovarik P, Stoiber D, Eyers PA, Menghini R, Neininger A, Gaestel M, Cohen P, Decker T. Stress-induced phosphorylation of STAT1 at Ser727 requires p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase whereas IFN-gamma uses a different signaling pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:13956–13961. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristensson K, Aldskogius M, Peng ZC, Olsson T, Aldskogius H, Bentivoglio M. Co-induction of neuronal interferon-gamma and nitric oxide synthase in rat motor neurons after axotomy: a role in nerve repair or death? J Neurocytol. 1994;23:453–459. doi: 10.1007/BF01184069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo T, Takeda M, Tanimukai S, Nishimura T. Neuropathologic changes in the gerbil brain after chronic hypoperfusion. Stroke. 1993;24:259–264. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.2.259. discussion 265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V, Zhang MX, Swank MW, Kunz J, Wu GY. Regulation of dendritic morphogenesis by Ras-PI3K-Akt-mTOR and Ras-MAPK signaling pathways. J Neurosci. 2005;25:11288–11299. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2284-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalli G, Hall A. Ral GTPases regulate neurite branching through GAP-43 and the exocyst complex. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:857–869. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200507061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau LT, Yu AC. Astrocytes produce and release interleukin-1, interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor alpha and interferon-gamma following traumatic and metabolic injury. J Neurotrauma. 2001;18:351–359. doi: 10.1089/08977150151071035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebon P, Boutin B, Dulac O, Ponsot G, Arthuis M. Interferon gamma in acute and subacute encephalitis. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1988;296:9–11. doi: 10.1136/bmj.296.6614.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CH, Della NG, Chew CE, Zack DJ. Rin, a neuron-specific and calmodulin-binding small G-protein, and Rit define a novel subfamily of ras proteins. J Neurosci. 1996;16:6784–6794. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-21-06784.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lein P, Johnson M, Guo X, Rueger D, Higgins D. Osteogenic protein-1 induces dendritic growth in rat sympathetic neurons. Neuron. 1995;15:597–605. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90148-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lein PJ, Guo X, Shi GX, Moholt-Siebert M, Bruun D, Andres DA. The novel GTPase Rit differentially regulates axonal and dendritic growth. J Neurosci. 2007;27:4725–4736. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5633-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li HL, Kostulas N, Huang YM, Xiao BG, van der Meide P, Kostulas V, Giedraitas V, Link H. IL-17 and IFN-gamma mRNA expression is increased in the brain and systemically after permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat. J Neuroimmunol. 2001;116:5–14. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(01)00264-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtman JW, Colman H. Synapse elimination and indelible memory. Neuron. 2000;25:269–278. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80893-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohmann C, Wong RO. Regulation of dendritic growth and plasticity by local and global calcium dynamics. Cell Calc. 2005;37:403–409. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masliah E, Heaton RK, Marcotte TD, Ellis RJ, Wiley CA, Mallory M, Achim CL, McCutchan JA, Nelson JA, Atkinson JH, Grant I. Dendritic injury is a pathological substrate for human immunodeficiency virus-related cognitive disorders. HNRC Group. The HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center. Ann Neurol. 1997;42:963–972. doi: 10.1002/ana.410420618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson MP. Neurotransmitters in the regulation of neuronal cytoarchitecture. Brain Res. 1988;472:179–212. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(88)90020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister AK. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of dendrite growth. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10:963–973. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.10.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. Plasticity of the hippocampus: adaptation to chronic stress and allostatic load. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;933:265–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb05830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlashan TH, Hoffman RE. Schizophrenia as a disorder of developmentally reduced synaptic connectivity. Arch Gen Psych. 2000;57:637–648. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.7.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller FD, Kaplan DR. Signaling mechanisms underlying dendrite formation. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003;13:391–398. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(03)00072-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monnerie H, Le Roux PD. Reduced dendrite growth and altered glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) 65- and 67-kDa isoform protein expression from mouse cortical GABAergic neurons following excitotoxic injury in vitro. Exp Neurol. 2007;205:367–382. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery MM, Dean AF, Taffs F, Stott EJ, Lantos PL, Luthert PJ. Progressive dendritic pathology in cynomolgus macaques infected with simian immunodeficiency virus. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1999;25:11–19. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2990.1999.00163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morikawa Y, Tohya K, Tamura S, Ichihara M, Miyajima A, Senba E. Expression of interleukin-6 receptor, leukemia inhibitory factor receptor and glycoprotein 130 in the murine cerebellum and neuropathological effect of leukemia inhibitory factor on cerebellar Purkinje cells. Neurosci. 2000;100:841–848. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00302-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison DK, Davis RJ. Regulation of MAP kinase signaling modules by scaffold proteins in mammals. Annual review of cell and developmental biology. 2003;19:91–118. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.111401.091942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JS, Bateman MC, Goldberg MP. Rapid alterations in dendrite morphology during sublethal hypoxia or glutamate receptor activation. Neurobiol Dis. 1996;3:215–227. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1996.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrish JZ, Emoto K, Kim MD, Jan YN. Mechanisms that regulate establishment, maintenance, and remodeling of dendritic fields. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2007;30:399–423. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.112907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patt S, Gertz HJ, Gerhard L, Cervos-Navarro J. Pathological changes in dendrites of substantia nigra neurons in Parkinson's disease: a Golgi study. Histol Histopathol. 1991;6:373–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platanias LC. Mechanisms of type-I- and type-II-interferon-mediated signalling. Nature Rev. 2005;5:375–386. doi: 10.1038/nri1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purves D. Functional and structural changes in mammalian sympathetic neurones following interruption of their axons. J Physiol. 1975;252:429–463. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1975.sp011151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purves D, Hadley RD, Voyvodic JT. Dynamic changes in the dendritic geometry of individual neurons visualized over periods of up to three months in the superior cervical ganglion of living mice. J Neurosci. 1986;6:1051–1060. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-04-01051.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purves D, Snider WD, Voyvodic JT. Trophic regulation of nerve cell morphology and innervation in the autonomic nervous system. Nature. 1988;336:123–128. doi: 10.1038/336123a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuther GW, Der CJ. The Ras branch of small GTPases: Ras family members don't fall far from the tree. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2000;12:157–165. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)00071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockstroh JK, Kreuzer KA, Sauerbruch T, Spengler U. Protein levels of interleukin-12 p70 holomer, its p40 chain and interferon-gamma during advancing HIV infection. J Infect. 1998;37:282–286. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(98)92138-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph JL, Shi GX, Erdogan E, Fields AP, Andres DA. Rit mutants confirm role of MEK/ERK signaling in neuronal differentiation and reveal novel Par6 interaction. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773:1793–1800. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindler C, Levy DE, Decker T. JAK-STAT signaling: from interferons to cytokines. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:20059–20063. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700016200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwamborn JC, Puschel AW. The sequential activity of the GTPases Rap1B and Cdc42 determines neuronal polarity. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:923–929. doi: 10.1038/nn1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao H, Andres DA. A novel RalGEF-like protein, RGL3, as a candidate effector for rit and Ras. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:26914–26924. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002241200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao H, Kadono-Okuda K, Finlin BS, Andres DA. Biochemical characterization of the Ras-related GTPases Rit and Rin. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999;371:207–219. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi GX, Andres DA. Rit contributes to nerve growth factor-induced neuronal differentiation via activation of B-Raf-extracellular signal-regulated kinase and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:830–846. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.2.830-846.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi GX, Rehmann H, Andres DA. A novel cyclic AMP-dependent Epac-Rit signaling pathway contributes to PACAP38-mediated neuronal differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:9136–9147. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00332-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L, Tu N, Patterson PH. Maternal influenza infection is likely to alter fetal brain development indirectly: the virus is not detected in the fetus. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2005;23:299–305. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein FS, Barks JD, Hagan P, Liu XH, Ivacko J, Szaflarski J. Cytokines and perinatal brain injury. Neurochem Intl. 1997;30:375–383. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(96)00072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh IN, El-Hage N, Campbell ME, Lutz SE, Knapp PE, Nath A, Hauser KF. Differential involvement of p38 and JNK MAP kinases in HIV-1 Tat and gp120-induced apoptosis and neurite degeneration in striatal neurons. Neurosci. 2005;135:781–790. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer ML, Shao H, Andres DA. Induction of neurite extension and survival in pheochromocytoma cells by the Rit GTPase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:20160–20168. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201092200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumner BE, Watson WE. Retraction and expansion of the dendritic tree of motor neurones of adult rats induced in vivo. Nature. 1971;233:273–275. doi: 10.1038/233273a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takashima S, Ieshima A, Nakamura H, Becker LE. Dendrites, dementia and the Down syndrome. Brain Dev. 1989;11:131–133. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(89)80082-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traugott U, Lebon P. Interferon-gamma and Ia antigen are present on astrocytes in active chronic multiple sclerosis lesions. J Neurol Sci. 1988;84:257–264. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(88)90130-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uddin S, Majchrzak B, Wang PC, Modi S, Khan MK, Fish EN, Platanias LC. Interferon-dependent activation of the serine kinase PI 3'-kinase requires engagement of the IRS pathway but not the Stat pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 2000;270:158–162. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Aelst L, Cline HT. Rho GTPases and activity-dependent dendrite development. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14:297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller M, Stevens A, Sommer N, Melms A, Dichgans J, Wietholter H. Comparative analysis of cytokine patterns in immunological, infectious, and oncological neurological disorders. J Neurol Sci. 1991;104:215–221. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(91)90313-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wes PD, Yu M, Montell C. RIC, a calmodulin-binding Ras-like GTPase. Embo J. 1996;15:5839–5848. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yawo H. Changes in the dendritic geometry of mouse superior cervical ganglion cells following postganglionic axotomy. J Neurosci. 1987;7:3703–3711. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-11-03703.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura T, Arimura N, Kawano Y, Kawabata S, Wang S, Kaibuchi K. Ras regulates neuronal polarity via the PI3-kinase/Akt/GSK-3beta/CRMP-2 pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;340:62–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.11.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Macara IG. The polarity protein PAR-3 and TIAM1 cooperate in dendritic spine morphogenesis. Nature Cell Biol. 2006;8:227–237. doi: 10.1038/ncb1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Macara IG. The PAR-6 polarity protein regulates dendritic spine morphogenesis through p190 RhoGAP and the Rho GTPase. Dev Cell. 2008;14:216–226. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoghbi HY. Postnatal neurodevelopmental disorders: meeting at the synapse? Science. 2003;302:826–830. doi: 10.1126/science.1089071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Sympathetic neurons were initially treated with BMP7 (50 ng/ml) for 5 days to induce dendritic growth, and then treated with IFNγ (30 ng/ml) for 30 min. Whole cell lysates were prepared and levels of activated ERK1/2 determined by phosphospecific immunoblotting. A representative Western blot for activated ERK1/2 (phospho-ERK1/2) and total ERK1/2 is shown; anti-actin immunoblotting was used to confirm equivalent protein loading. Phosphorylated ERK1/2 are detected in control cultures treated with vehicle (PBS) as would be expected because sympathetic cultures are grown in the presence of NGF (Lein et al. 2007). Treatment with IFNγ fails to stimulate ERK1/2 above these control levels. Similar results were obtained using cell lysates prepared using cultures obtained from 3 independent dissections.