Abstract

Molecular epidemiologic studies of vitamin D and risk of cancer and other health outcomes usually involve a single measurement of the biomarker 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] in serum or plasma. However, the extent to which 25(OH)D concentration at a single time point is representative of an individual's long-term vitamin D status is unclear. To address this question, we evaluated within-person variability in 25(OH)D concentration across serum samples collected at three time points over a five year period among 29 participants in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial. Blood collection took place year-round, though samples for a given participant were collected in the same month each year. The within-person coefficient of variation (CV) and intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) were calculated using variance components estimated from random effects models. Spearman rank correlation coefficients were calculated to evaluate agreement between measurements at different collection times (baseline, +1 year, +5 years). The within-subject CV was 14.9% [95% confidence interval (CI) 12.4%-18.1%] and the ICC was 0.71 (95% CI 0.63-0.88). Spearman rank correlation coefficients comparing baseline to +1 year, +1 year to +5 years, and baseline to +5 years were 0.65 (95% CI 0.37-0.82), 0.61 (0.29-0.81) and 0.53 (0.17-0.77) respectively. Slightly stronger correlations were observed after restricting to non-Hispanic Caucasian subjects. These findings suggest that serum 25(OH)D concentration at a single time point may be a useful biomarker of long-term vitamin D status in population-based studies of various diseases.

Keywords: Vitamin D, biomarkers, variability, serum, Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial

Introduction

Evidence from in vitro and animal studies suggests that the steroid prohormone vitamin D may play an important protective role against cancer development and metastasis (1). These experimental findings have led to several epidemiologic studies investigating associations with cancer risk for prediagnostic blood levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D], the primary circulating form of vitamin D and a clinical biomarker for vitamin D status. Some prospective studies have reported associations between low circulating 25(OH)D and increased risk of various cancers (2-4). Most, but not all, studies investigating pre-diagnostic serum or plasma 25(OH)D concentration and colorectal cancer risk are suggestive of a protective effect (5-10); however, the totality of the evidence for other malignancies is inconclusive (8-12). A potential limitation of these studies is their reliance upon 25(OH)D measurements in a single sample of serum or plasma from each individual. While levels of 25(OH)D are known to vary seasonally (highest in summer and fall, lowest in winter and spring) in accordance with dermal vitamin D production following sun exposure, relatively little is known about the degree to which an individual's season-specific level of 25(OH)D varies over time, and whether vitamin D concentration at a given time point is representative of an individual's long-term vitamin D status (13).

To better understand the within-person variability of 25(OH)D over time, we compared 25(OH)D measurements from serum samples collected at study baseline, one year and five years later among 29 participants in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial (PLCO). Blood samples within PLCO were collected year-round, though serial samples from each participant were collected in the same month each year during the five-year follow-up period. Because of this collection protocol, this study provides a unique opportunity to assess the variability over time of 25(OH)D measurements within the same season.

Materials and Methods

The design, methods, and goals of PLCO have been described previously (14). This study used stored serum from a sample of 29 cancer-free subjects previously selected to support evaluations of long-term stability for various analytes. Subjects provided nonfasting baseline blood samples that were processed and frozen within two hours of collection and stored at −70°C. Measurements of 25(OH)D were performed on 100-μL aliquots of serum collected from these subjects at study baseline, the first annual follow-up health examination (+1yr), and the fifth annual follow-up examination (+5yr). Of the 29 subjects, 28 had serum from baseline, 29 had serum from +1yr, and 26 had serum from +5yr. All subjects had serum from at least two time points, and 25 subjects had serum from all three time points. Measurements of 25(OH)D in nmol/L were performed at Heartland Assays, Inc. (Ames, IA) by competitive chemiluminescence immunoassay (CLIA) using the DiaSorin LIAISON® 25-OH Vitamin D TOTAL Assay (DiaSorin S.p.A., Saluggia, Italy). All 83 samples were measured in a single batch.

Using variance components computed from a random effects model of log-transformed 25(OH)D concentrations, we calculated the coefficient of variation (CV) on the original scale to assess the extent of within-person variability across the three time periods (15). The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for log-transformed 25(OH)D concentration was calculated to evaluate the degree of between-person variability relative to total variability, including within-person variability over time [i.e., σ2between / (σ2between + σ2within)]. Unadjusted Spearman rank correlation coefficients were calculated to perform pairwise evaluations of agreement between measurements at different time points (baseline vs. +1yr, +1yr vs. +5yr, baseline vs. +5yr, and average of baseline/+1yr vs. +5yr). The aforementioned analyses were also conducted including only non-Hispanic Caucasian subjects (N=23).

Results

The average age at baseline among subjects included in this analysis was 61 years (range 55-70 years), and over half of the participants were male (N=18). Most participants (N=23) were non-Hispanic Caucasian; the remaining six participants were Asian. Participants from each of the ten PLCO screening centers throughout the United States were represented in the study sample.

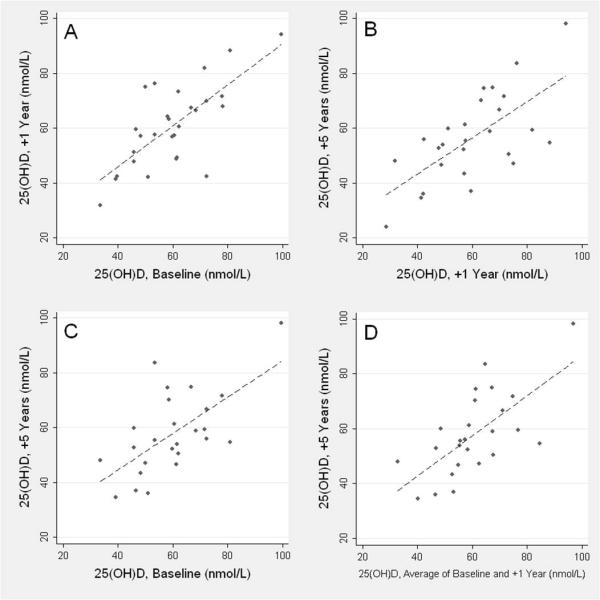

Statistics summarizing within-person variability and agreement of 25(OH)D are summarized in Table 1. The within-person CV across the three time points was 14.9% (95% CI 12.4%-18.1%) over the five-year period, and the ICC was 0.71 (95% CI 0.63-0.88). Spearman rank correlation coefficients comparing baseline to +1yr, +1yr to +5yr, and baseline to +5yr were 0.65 (95% CI 0.37-0.82), 0.61 (0.29-0.81), and 0.53 (0.17-0.77) respectively. We also calculated the Spearman rank correlation coefficient comparing the average of the baseline and +1yr measurements against +5yr measurements, and found that the correlation was slightly higher than when either baseline or +1yr was considered independently in relation to +5yr measurements (Spearman rank correlation coefficient = 0.65; 95% CI = 0.34-0.83). Plots of 25(OH)D measurements for each pairwise comparison are shown in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and estimates of within-subject variability and agreement between serum concentrations of 25(OH)D measured at three time points (Baseline, +1yr, and +5yr) over a five-year period

| Analysis | All Subjects | |

|---|---|---|

| N | Values | |

| Season of blood draw* | ||

| January-March | 7 | |

| April-June | 6 | |

| July-September | 11 | |

| October-December | 5 | |

| Summary of 25(OH)D measures at: | ||

| Baseline | ||

| Mean (SD) | 28 | 60.0 (14.6) nmol/L |

| Median | 28 | 60.2 nmol/L |

| Range | 28 | 33.7-99.6 nmol/L |

| +1 Year | ||

| Mean (SD) | 29 | 59.8 (15.9) nmol/L |

| Median | 29 | 59.5 nmol/L |

| Range | 29 | 28.6-94.2 nmol/L |

| +5 Years | ||

| Mean (SD) | 26 | 56.6 (16.2) nmol/L |

| Median | 26 | 55.1 nmol/L |

| Range | 26 | 24.1-98.2 nmol/L |

| Measures of agreement | ||

| CV (95% CI) | 29 | 14.9% (12.4%-18.1%) |

| ICC (95% CI) | 29 | 0.71 (0.63-0.88) |

| Spearman rank correlation coefficients (95% CI) | ||

| Baseline vs. +1yr | 28 | 0.65 (0.37-0.82) |

| +1yr vs. +5yr | 26 | 0.61 (0.29-0.81) |

| Baseline vs. +5yr | 25 | 0.53 (0.17-0.77) |

| Baseline/+1yr average vs. +5yr | 25 | 0.65 (0.34-0.83) |

All participants had the serial blood draws during the same calendar month in each year. On average, samples were collected within a 13-day window (range 2-26 days).

Figure 1.

Scatterplots and fitted lines for serum 25(OH)D concentration at: A) Baseline vs. +1yr; B) +1yr vs. +5yr; C) Baseline vs. +5yr; and D) Average of Baseline/+1yr vs. +5yr

After restricting to non-Hispanic Caucasian subjects, the within-person CV was 15.5% (95% CI 12.5%-19.2%) and the ICC was 0.75 (95% CI 0.64-0.90). We observed slightly stronger correlations when we restricted to non-Hispanic Caucasian subjects (Spearman rank correlation coefficients = 0.72, 0.69, 0.58, and 0.70 for baseline vs. +1yr, +1yr vs. +5yr, baseline vs. +5yr, and average of baseline/+1yr vs. +5yr, respectively). Correlations were generally consistent after stratification by sex (data not shown).

Discussion

Although serum 25(OH)D concentrations are often used to characterize vitamin D levels in population-based studies, the extent to which a single measurement is representative of long-term vitamin D status is unclear. The findings of this study suggest that measurements of 25(OH)D from serum collected at the same time of year are reasonably stable in healthy subjects over a five-year period. We observed relatively low within-subject variability and fairly high correlations in 25(OH)D measured from samples collected at study baseline, after 1 year, and after 5 years.

To evaluate the impact of within-person variability on relative risk estimates in studies of vitamin D status and cancer risk, we used the following formula derived from Rosner et al. (16) to estimate the degree of relative risk attenuation:

Given the ICC of 0.71 that was observed in this study, we estimated that for true relative risks of 1.5, 2.0, and 2.5, we would expect observed relative risks of 1.3, 1.6, and 1.9, respectively. Investigators should consider this attenuation when designing studies of various diseases in relation to long-term vitamin D status to ensure that they have adequate statistical power.

If possible, investigators might also consider taking multiple 25(OH)D measurements from each subject at different times to reduce misclassification of vitamin D status due to within-person variability over time (17), although this may not be feasible in many studies. In this study we observed a higher correlation when the average of baseline and +1yr measurements was compared to 25(OH)D concentration at +5yr. The average of two measurements taken one year apart may thus provide a better assessment of long-term vitamin D status than a single measurement, although the increase in agreement observed in this study was relatively small.

Seasonal variation in 25(OH)D concentration has been well-described (18, 19). However, to our knowledge, relatively few studies have evaluated temporal variability beyond seasonal effects. Platz et al. (11) measured 25(OH)D concentrations in two blood samples obtained an average of 3.0 years apart from 144 cancer-free men in the Health Professionals Follow-up Study. They reported a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.70, which is consistent with the level of agreement observed in this study. Rejnmark et al. (20) evaluated variability between serial measurements using the same assay at three time points over a four-year period among 187 postmenopausal women in the Danish Osteoporosis Prevention Study; median within-person CVs ranged from 13% to 19%.

An important strength of the present study is the use of serum from PLCO blood specimens collected up to five years apart, at the same time each year, which provided a unique opportunity to control for seasonal variation in 25(OH)D while assessing variability over a long period. However, the five-year range in serial specimens limits the generalizability of our findings, in that the level of agreement of a single measure with 25(OH)D levels over longer time periods remains unclear. It is worth noting that a five-year time window may be biologically relevant to the relationship between vitamin D and cancer, in that vitamin D has been postulated to exert effects which influence late-stage carcinogenesis, metastasis and survival for some cancers (1). This study is also limited by its small size, although the 95% confidence intervals surrounding the CV and ICC estimates still support the inference of low within-person variability and high agreement in 25(OH)D across the time points.

In conclusion, the findings from this study suggest that serum 25(OH)D concentration at a single point in time may be a useful biomarker of season-specific vitamin D status over a five-year period. Further studies are needed to evaluate the extent of within-person variability of 25(OH)D over a longer time.

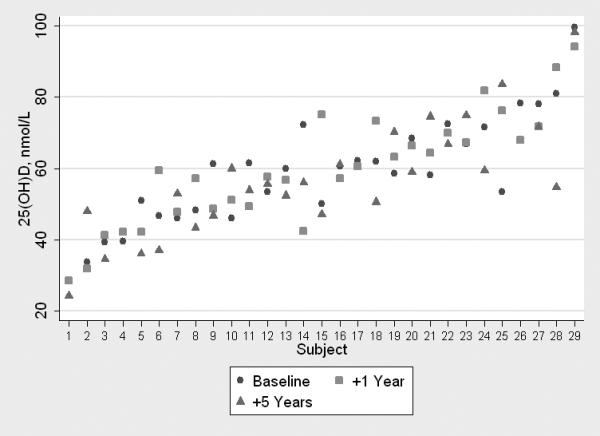

Figure 2.

Serial measurements of serum 25(OH)D concentration at baseline, +1yr, and +5yr for each subject

Acknowledgements and Funding

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics.

References

- 1.Giovannucci E. The epidemiology of vitamin D and cancer incidence and mortality: a review (United States). Cancer Causes Control. 2005;16:83–95. doi: 10.1007/s10552-004-1661-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li H, Stampfer MJ, Hollis JB, et al. A prospective study of plasma vitamin D metabolites, vitamin D receptor polymorphisms, and prostate cancer. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e103. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crew KD, Gammon MD, Steck SE, et al. Association between plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D and breast cancer risk. Cancer Prev Res (Phila Pa) 2009;2:598–604. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garland CF, Gorham ED, Mohr SB, Garland FC. Vitamin D for cancer prevention: global perspective. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19:468–83. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gorham ED, Garland CF, Garland FC, et al. Optimal vitamin D status for colorectal cancer prevention: a quantitative meta analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32:210–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woolcott CG, Wilkens LR, Nomura AM, et al. Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and the risk of colorectal cancer: the multiethnic cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:130–4. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jenab M, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Ferrari P, et al. Association between pre-diagnostic circulating vitamin D concentration and risk of colorectal cancer in European populations:a nested case-control study. BMJ. 2010;340:b5500. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b5500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freedman DM, Looker AC, Chang SC, Graubard BI. Prospective study of serum vitamin D and cancer mortality in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1594–602. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.IARC . IARC Working Group Reports. Vol. 5. International Agency for Research on Cancer; Lyon: Nov 25, 2008. Vitamin D and Cancer. [Google Scholar]

- 10.van der Rhee H, Coebergh JW, de Vries E. Sunlight, vitamin D and the prevention of cancer: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2009;18:458–75. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e32832f9bb1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Platz EA, Leitzmann MF, Hollis BW, Willett WC, Giovannucci E. Plasma 1,25-dihydroxy- and 25-hydroxyvitamin D and subsequent risk of prostate cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 2004;15:255–65. doi: 10.1023/B:CACO.0000024245.24880.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahn J, Peters U, Albanes D, et al. Serum vitamin D concentration and prostate cancer risk: a nested case-control study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:796–804. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Millen AE, Bodnar LM. Vitamin D assessment in population-based studies: a review of the issues. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:1102S–5S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.4.1102S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gohagan JK, Prorok PC, Levin DL, Sullivan D. The Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial. Control Clin Trials. 2000;21(Supplement 6) doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(00)00097-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosner B. Fundamentals of Biostatistics. 5th Edition Duxbury; Pacific Grove, CA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosner B, Spiegelman D, Willett WC. Correction of logistic regression relative risk estimates and confidence intervals for random within-person measurement error. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;136:1400–13. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Armstrong BK, White E, Saracci R. Principles of Exposure Measurement in Epidemiology. Oxford University Press; New York: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lagunova Z, Porojnicu AC, Lindberg F, Hexeberg S, Moan J. The dependency of vitamin D status on body mass index, gender, age and season. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:3713–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maxwell JD. Seasonal variation in vitamin D. Proc Nutr Soc. 1994;53:533–43. doi: 10.1079/pns19940063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rejnmark L, Lauridsen AL, Brot C, et al. Vitamin D and its binding protein Gc: long-term variability in peri- and postmenopausal women with and without hormone replacement therapy. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2006;66:227–38. doi: 10.1080/00365510600570623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]