Abstract

Background

The NH2-terminal sequence of the M protein from group A streptococci (GAS) defines the serotype of the organism and contains epitopes that evoke bactericidal antibodies.

Methods

To identify additional roles for this region of the M protein, we constructed a mutant of M5 GAS expressing an M protein with a deletion of amino acid residues 3–22 (ΔNH2).

Results

M5 and the ΔNH2 mutant were resistant to phagocytosis and were similarly virulent in mice. However, ΔNH2 was significantly less hydrophobic, contained less lipoteichoic acid (LTA) on its surface and demonstrated reduced adherence to epithelial cells. Theses differences were abolished when organisms were grown in the presence of protease inhibitors. Treatment with cysteine proteases or with human saliva resulted in the release of M protein from ΔNH2 at a significantly greater rate than that observed with M5. The ΔNH2 strain also showed a significant reduction in its ability to colonize the upper respiratory mucosa of mice compared to the parent strain.

Conclusion

The NH2-terminus of M5 has an important role in conferring protection of the surface protein from proteolytic cleavage, thus preserving its function as an anchor for LTA which is a primary mediator of adherence to epithelial cells and colonization.

Keywords: Streptococcus pyogenes, M protein, bacterial adherence, hydrophobicity, proteolysis

Introduction

M proteins are critical virulence factors of Streptococcus pyogenes (group A streptococci, GAS). They are arranged on the bacterial surface as coiled-coil dimers that share certain structural characteristics, including a hypervariable NH2-terminal sequence that defines the serotype, repeating sequences designated A, B, and C repeats, a secondary alpha-helical structure throughout most of the length of the protein, a cell wall spanning region that contains the LPXTG sortase recognition sequence and a hydrophilic tail [1]. The hypervariable epitopes within the first 20–30 amino acids of the protein serve as the basis for serologic typing and also elicit antibodies that promote phagocytic killing in the immune host [2, 3]. Resistance to phagocytosis in the non-immune host is mediated in large part by M protein binding of fibrinogen, factor H, C4BP and other host proteins, all of which have been shown to bind to specific regions of the M protein proximal to the NH2-terminal region [4–6]. Thus, the M protein serves a dual function as a major virulence factor of these organisms by mediating resistance to phagocytosis and also the major protective antigen by evoking opsonic antibodies.

In previous studies designed to determine the biological function of the type-specific region of M5 protein, mutants were created in which the NH2-terminal domain of the protein had been deleted. These studies showed that there was no influence of the type-specific region on resistance to phagocytosis [4]. Khandke, et al. [7] observed that the NH2-terminus of M proteins served to stabilize the dimeric structure of the coiled-coil, and M proteins without the type-specific region were mostly isolated as monomers. Previous studies have also shown that intact M protein is required for stabilizing lipoteichoic acid (LTA) on the bacteria and maintaining the hydrophobic characteristic of the cell surface [8, 9]. Therefore, the present study was undertaken to further examine the potential function of the NH2-terminus of type 5 M protein. Because of the role of hydrophobicity and LTA in bacterial adhesion, we hypothesized that the NH2-terminus of M protein may have a role in mucosal colonization. We show that surface-expressed type 5 M protein devoid of NH2-terminal 20 amino acids is more susceptible to proteolytic cleavage by streptococcal and salivary proteases. As a result, the type 5 streptococcus expressing the truncated M protein exhibited reduced hydrophobicity, reduced adhesion to epithelial cells and lower levels of colonization of the upper respiratory tract of mice.

Material and Methods

Bacterial strains and plasmids

S. pyogenes serotype 5, strain Manfredo [10], was grown in Todd-Hewitt broth supplemented with 0.5% yeast extract (THB). Mutagenic primers were used to generate internal deletions of the hypervariable and “A” repeat regions of the emm5 gene. The PCR primers for the unique and “A” repeats were 5' GAAGTTAGTGCAGCCGTGGAAAACCATGACTTAAAAAC 3' and 5' GAAAACCATGACTTAAAAACTGAAGCAGAAAACGATAAG 3' respectively and their compliments. The modified genes lacking codons 3–22 encoding the hypervariable region or codons 30–62 encoding the majority of the A repeat region of the mature sequence were ligated into pGHost+9 vector and electroporated into the streptococci. Procedures for selection of double-crossover events were performed as described by Maguin et al. [11]. Gene replacement was confirmed by PCR and by DNA sequencing across the mutation.

Opsonization and bactericidal assays

In vitro opsonization and bactericidal assays were performed as previously described [12].

Growth of bacteria and proteolytic enzyme inhibitors

Bacteria were grown overnight in THB which in some experiments was supplemented with E64 at a concentration of 1 µg/ml. Some experiments also included controls to which a cocktail of protease inhibitors was added, consisting of 1× Complete (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany).

Determination of hydrophobicity

Hydrophobicity was determined by the hexadecane method, as described [13].

Protein analysis

Proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions. Estimation of the amount of M protein that could be extracted from the bacterial surface was performed by immunoblot. Films from two separate experiments were scanned and analyses were performed using the NIH Image program (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image/).

Fibrinogen binding to M protein and to intact streptococci

The binding of human fibrinogen (Fgn, Kabi Vitrum Stockholm, Sweden) to M5 proteins extracted with hot acid, electrophoresed and then transferred to Protran membrane was detected using rabbit anti-human fibrinogen (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) for binding of biotinylated Fgn to whole streptococci were also performed. Microtiter wells were coated with a washed suspension of log-phase bacteria (0.3 OD in 0.05 M carbonate, pH 10). Wells reacted with biotinylated Fgn in Tris buffered saline (TBS) containing 50 µg/ml of albumin and 0.05% Tween 20. Binding of biotinylated Fgn was detected using Neutralite avidin-peroxidase (Molecular Probes Inc., Eugene, OR) diluted 1:2000 in TBS with albumin and 0.05% Tween 20. Turbo TMB (Pierce Chem Co., Rockford, IL) was used as the substrate.

Enzymatic treatment and phenol extraction of the bacteria

Forty µl of trypsin (1 mg/ml PBS, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was added to 0.4 ml bacterial suspension (OD530 =1.0) in PBS. After 30 minutes at 37°C, the bacteria were centrifuged and the supernatant was removed, heated to 95°C for 5 min to inactivate enzymes, and saved for determining LTA content. The bacteria were washed twice with distilled water and then assayed for hydrophobicity. Partially purified streptopain (SpeB) from Streptococcus pyogenes and gingipain from Porphyromonas gingivalis were also used to enzymatically treat the streptococci prior to M protein analysis, assays for buccal cell adhesion, and assays of hydrophobicity. SpeB partial purification followed the method of Raeder et al. [14]. Gingipain was obtained from culture supernatant by the method of Potempa et al. [15]. Bacteria were exposed to human saliva that was filter-sterilized and diluted 1:2 with PBS containing 2× concentrated protease inhibitor cocktail or DTT and cysteine at a final concentration of 2mM each. After incubating for 15 min with inhibitor or activator, the saliva was added to the washed bacterial cell pellets for the times specified.

Phenol extraction of membrane LTA was performed as previously described [16]. The amount of LTA released into the growth medium was measured in culture supernatants that were first sterilized by filtration through a 0.2 micron filter. LTA concentrations were determined using competitive ELISA [17].

Intranasal and intraperitoneal mouse challenge models

For intranasal challenge, female ICR mice, aged 5 to 6 weeks (Harlan Sprague Dawley, Inc., Indianapolis, IN) were anesthetized with isoflurane and inoculated intranasally with 2×107 CFU of M5 (N=21) or ΔNH2 (N=20) in 20 µl of PBS. After 6 h, mice were anesthetized and a throat swab was taken. Each swab was immersed in 0.2 ml PBS in a microfuge tube and vortexed. Residual bacteria were recovered by centrifugation and added to the original tube. The entire sample was spread on blood agar plates (BBL TSA II 5%SB) and beta hemolytic colonies were counted after overnight incubation. The results were recorded as total CFU recovered per swab per mouse.

For intraperitoneal challenge infections, 5 groups of 5 female ICR mice each, aged 5 to 6 weeks were challenged by intraperitoneal injection of 104–108 CFU of the indicated bacteria. The number of surviving mice was recorded daily for 7 days. Moribund mice were sacrificed and recorded as dead. LD50 values were calculated using the method of Reed and Muench [18, 19].

Epithelial cell adhesion assay

The adhesion assay to human buccal epithelial cells was performed as described previously [20].

Statistical analyses

The Wilcoxon (Krushal-Wallis) test was used to evaluate differences in colonization of mice after challenge with mutant and parent streptococcal strains. Student's t-test was used to analyze differences between controls and test samples in all other assays.

Results

Two mutant strains of type 5 GAS were constructed for these studies. The ΔNH2 strain expressed an M protein with a deletion of amino acids 3–22 and the ΔA strain expressed an M protein with a deletion of five of the seven-residue A repeats that are located just proximal to the hypervariable NH2-terminal domain. The parent M5 strain and ΔA mutant reacted with rabbit antisera against a recombinant version of the M5 protein (pepM5) and against a synthetic peptide copying amino acids 1–15 of the mature protein (SM5(1–15)) (Table 1). In contrast, the ΔNH2 strain reacted with anti-pepM5 but not with antibodies against the amino-terminal synthetic peptide, confirming that the M5 protein was expressed on the surface of the ΔNH2 mutant and that the NH2-terminal region of the M protein was absent. The total amount of immunoreactive M5 protein on the bacterial surface (Table 1) and the amount of labeled fibrinogen binding (data not shown) were not affected by either of the deletions, which was consistent with previous studies [4, 5].

Table 1.

Characteristics of M5 mutant strains

| Property | wt M5 | ΔNH2 M5 | ΔA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Slide agglutination with: | |||

| Anti PepM5 | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Anti SM5(1–15) | +++ | − | ++ |

| ELISA titer against streptococci: | |||

| Anti-pepM5 | 1:3200 | 1:6400 | 1:3200 |

| Anti-SM5(1–15) | 1:80000 | 1:400 | 1:40000 |

The deletion of the NH2 terminal region of M5 protein did not affect either resistance to phagocytosis as measured by percent PMNs with associated bacteria (Fig. 1A) or by growth of the organisms in whole human blood (Fig. 1B). Anti-pepM5 effectively opsonized the parent and both the ΔNH2 and ΔA mutants and it reduced the ability of each bacterial strain to grow in whole human blood (Fig. 1A and 1B, respectively). In contrast, antiserum against SM5(1–15) opsonized the parent and the ΔA mutant, but not the ΔNH2 mutant, which is consistent with a deletion of the NH2-terminal region in the ΔNH2 mutant (Fig. 1A and 1B). Additionally, the virulence of the ΔNH2 strain was similar to that of the parent strain, as determined after intraperitoneal challenge infections of mice. The LD50 of the wild-type strain was 2.4×107 CFU and for the ΔNH2 mutant was 7.8 ×107. The effect of the ΔA mutant on virulence in mice was not determined in these experiments.

Figure 1.

Opsonization expressed as percent PMNs with associated bacteria (A) and growth in whole human blood (B) of M5 streptococci and its ΔNH2 and ΔA mutants. For opsonization experiments (A), bacteria were pre-incubated with normal rabbit serum (NRS, striped bars), anti-pepM5 (open bars) or anti-SM5(1–15) (solid bars) for 30 min at 37°C before adding the mixture to whole blood followed by end-over-end rotation for 45 min at 37°C at which time smears were prepared and the percent PMN with associated bacteria was recorded. Results are expressed as the mean values +/−S.D. from three separate experiments. Opsonization of the ΔNH2 strain in the presence of anti-SM5(1–15) was equivalent to that observed with NRS and significantly lower than that achieved with the parent strain in the presence of anti-SM5(1–15) (p=0.005). Although the percent of PMNs with associated ΔNH2 and ΔA mutants in the presence of NRS was slightly higher than that observed with the parent strain with NRS, only the value observed for the ΔA mutant was significantly different when compared to the parent strain (p=0.02). (B) Growth in whole blood in the presence of NRS (striped bars), anti-pepM5 (open bars) or anti-SM5(1–15) (solid bars) was determined by adding the parent M5 (N=9), ΔNH2 (N=9) and ΔA (N=3) to whole blood followed by end-over-end rotation for 3 hrs at 37°C at which time samples were taken and pour plates were made in sheep's blood agar to determine the number of surviving colonies. Growth index was calculated by dividing the number of CFU surviving after the 3 hr rotation by the number of CFU in the initial inoculum. The growth of the ΔNH2 and ΔA mutants was equivalent to the parent strain except that the ΔNH2 mutant grew in the presence of anti-SM5(1–15) (solid bar) while the parent was killed (p=0.0002). The asterisks indicate significant differences when compared to the parent strain.

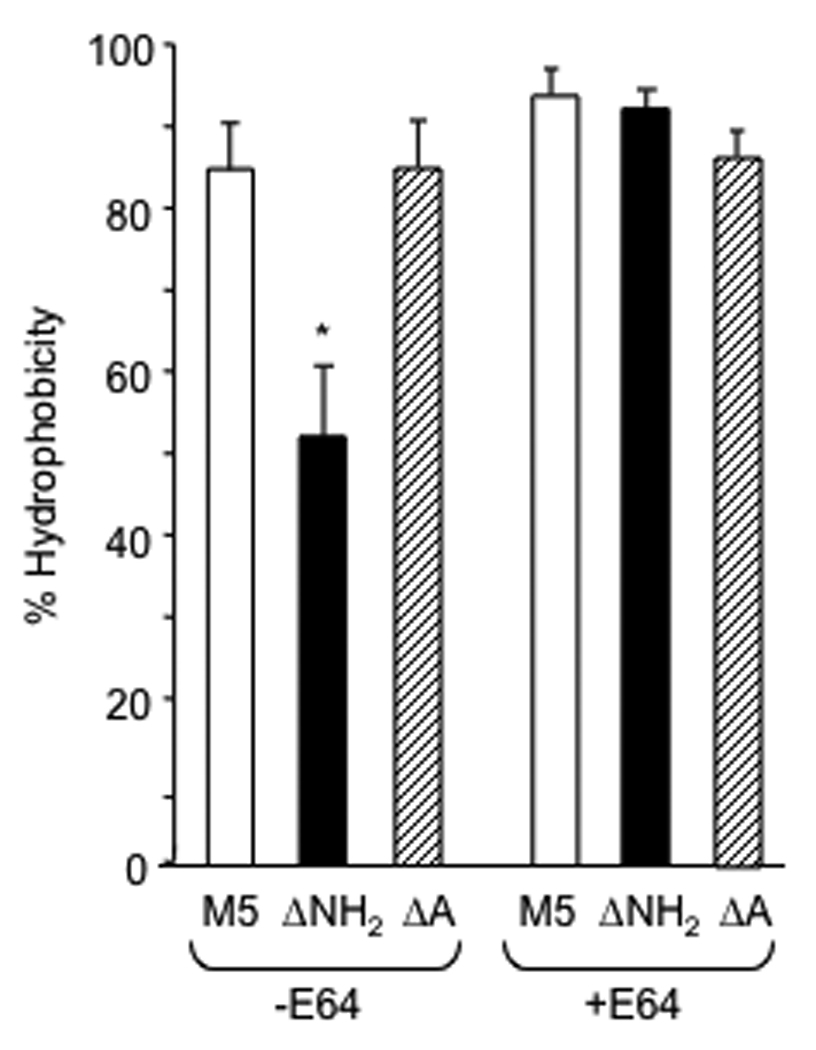

Taken together, the data indicate that the ΔNH2 deletion strain exhibited phenotypic characteristics very similar to those of the parent M5 strain, except for the binding of antibody specific for the NH2-terminus. Therefore, we turned our attention to assays of bacterial surface hydrophobicity, a phenotypic characteristic that could potentially affect pathogenesis of infection. Interestingly, the ΔNH2 mutant exhibited significantly reduced hydrophobicity compared to the parent strain when grown overnight in the absence of protease inhibitors (Fig. 2A). In contrast, the hydrophobicity of the ΔA mutant was not significantly different from that of the parent M5 strain. Because our recent studies demonstrated that hydrophobicity was associated with the expression of M and M-like proteins on the surface of the organisms and their ability to present LTA on the bacterial surface [9], we also tested the hydrophobicity of the parent and ΔNH2 mutant grown overnight in the presence of E64, an inhibitor of SpeB, which has previously been shown to degrade M protein. Growth of the ΔNH2 mutant in E64 resulted in hydrophobicity measurements that were comparable to the parent strain (Fig. 2). The NH2-terminal deletion did not significantly affect the hydrophobicity of bacteria harvested at or before the late logarithmic phase (83.3±4.7% for the M5 parent and 76.4%±4.7% for the ΔNH2 mutant, p>0.1), at which time SpeB expression is minimal [21, 22].

Figure 2.

Hydrophobicity of wt M5 and its ΔNH2 and ΔA mutants. Bacteria were grown overnight in THB in the absence or presence of SpeB inhibitor (E64), harvested and washed in distilled water to determine percent hydrophobicity (+/−S.D), as described in Materials and Methods. The asterisk denotes a significant difference between wt and the ΔNH2 mutant (p<0.01).

These results suggested that endogenous cysteine protease activity (SpeB) may be involved in the observed differences in hydrophobicity between the parent M5 strain and the ΔNH2 mutant. Previous studies have shown that the surface hydrophobicity of type 5 streptococci is dependent on the formation of complexes between LTA and M5 protein on the bacterial surface [9, 13]. Therefore, we performed experiments to compare the amounts of LTA associated with three different streptococcal compartments: the bacterial surface proteins (trypsin-releasable LTA), membrane-associated (i.e. phenol-extractable LTA) after surface LTA had been removed by trypsin, and LTA naturally released into the medium (Fig. 3, A–C). The amount of trypsin-released, surface LTA (Fig. 3A) was significantly reduced in the ΔNH2 mutant compared to the parent strain, while both the membrane-associated (Fig. 3B) and naturally released (Fig. 3C) LTA were comparable in both strains. Growth of the organisms in the presence of E64 (Fig. 3A) restored the amount of surface LTA on the ΔNH2 mutant to levels comparable to the parent M5 strain. Because surface LTA facilitates adhesion of streptococci to epithelial cells [23, 24], we also assayed the parent and ΔNH2 mutant GAS for their ability to adhere to human buccal epithelial cells. The adhesion of the ΔNH2 mutant was significantly reduced compared to the parent strain (Fig. 3D). The effect of the ΔNH2 domain deletion on epithelial adhesion and surface LTA was abolished when the ΔNH2 mutant was grown in media containing E64 (Fig. 3, A–D).

Figure 3.

LTA associated with the surface (A), cell membrane (B) and culture supernatant (C) and adhesion to buccal cells (D) of wt M5 and its ΔNH2 mutant. Bacteria were grown overnight in THB in the absence and presence of SpeB inhibitor (E64), harvested and washed in distilled water to determine LTA content in the culture supernatant (naturally released LTA), trypsin extract (surface LTA) followed by phenol extract (membrane LTA) and adhesion to immobilized buccal cells by ELISA. Data are presented as the mean +/−S.D. from three experiments. The asterisks denote significant differences between wt and the ΔNH2 mutant values (p<0.01).

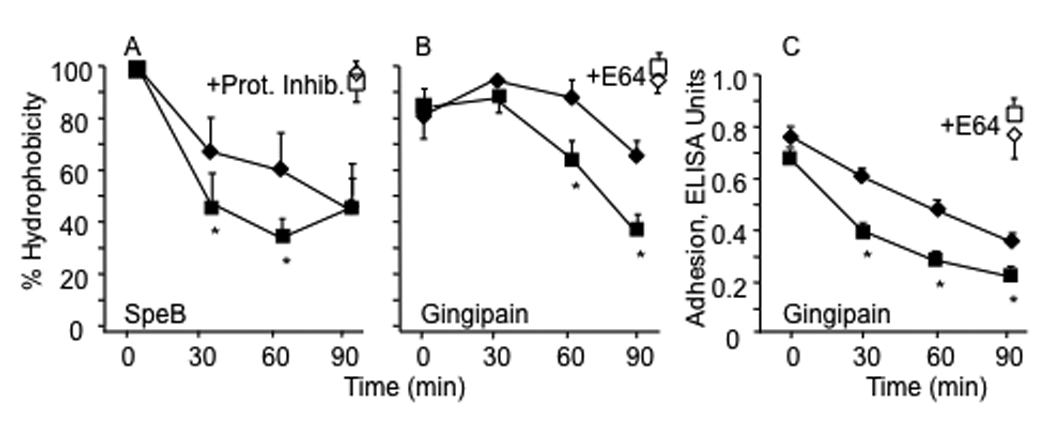

Because surface bound LTA and the resultant hydrophobicity depend on the presence of M protein, hydrophobicity and adhesion could be affected by the apparent sensitivity of M5 protein devoid of its NH2-terminal region to digestion by the streptococcal cysteine protease, SpeB, as noted above. Thus, further experiments were performed to assess this possibility. The rate at which the ΔNH2 mutant exhibited reduced hydrophobicity upon short-term exposure to partially purified exogenous SpeB was significantly greater when compared to the parent strain and this difference was abolished if the organisms were first washed and suspended in buffer containing a cocktail of protease inhibitors (Fig. 4A). Another cysteine protease that may be present in the upper respiratory tract is gingipain secreted by P. gingivalis [25], a common inhabitant of the oral cavity. Therefore, we tested the effects of gingipain on the hydrophobicity and the results were similar to those obtained with SpeB. Exposure to gingipain resulted in a reduction in hydrophobicity at a significantly higher rate in the ΔNH2 mutant compared to the parent strain and in this case the difference was abolished when the organisms were suspended in buffer that contained protease inhibitors but was devoid of cysteine (Fig. 4B). Gingipain also caused a reduction in the ability of the ΔNH2 mutant streptococci to adhere to buccal epithelial cells at a rate significantly higher than that of the parent strain (Fig. 4C). The rapid effect of gingipain on epithelial adhesion was abolished by adding a cocktail of protease inhibitors.

Figure 4.

Kinetics of loss of hydrophobicity (A, B) and epithelial adhesion (C) of wt and ΔNH2 mutant streptococci exposed to cysteine proteases. Both bacterial strains were grown overnight phase in THB containing E64, washed in appropriate buffers and exposed to SpeB (A) or gingipain (B) for the indicated periods of time. Hydrophobicity was determined after washing the bacteria three times with distilled water by the hexadecane method. Values for hydrophobicity of bacteria washed and suspended in buffer containing SpeB plus a cocktail of protease inhibitors (A) and in buffer devoid of cysteine containing gingipain and a cocktail of protease inhibitors (B) are shown in open symbols for the 90 minute time point for each strain. Adhesion to immobilized human buccal cells was estimated using bacteria exposed to gingipain for the times indicated using ELISA to detect adhering streptococci. Values are expressed as the mean +/−S.D. from three experiments of wt (close diamond symbols) and of ΔNH2 mutant (closed square symbols). Asterisks denote significant differences between wt strain and its ΔNH2 mutant. These values obtained after 90 minutes in the presence of protease inhibitors (open symbols) were not significantly different from those obtained at time 0 in the absence of protease inhibitors (closed symbols).

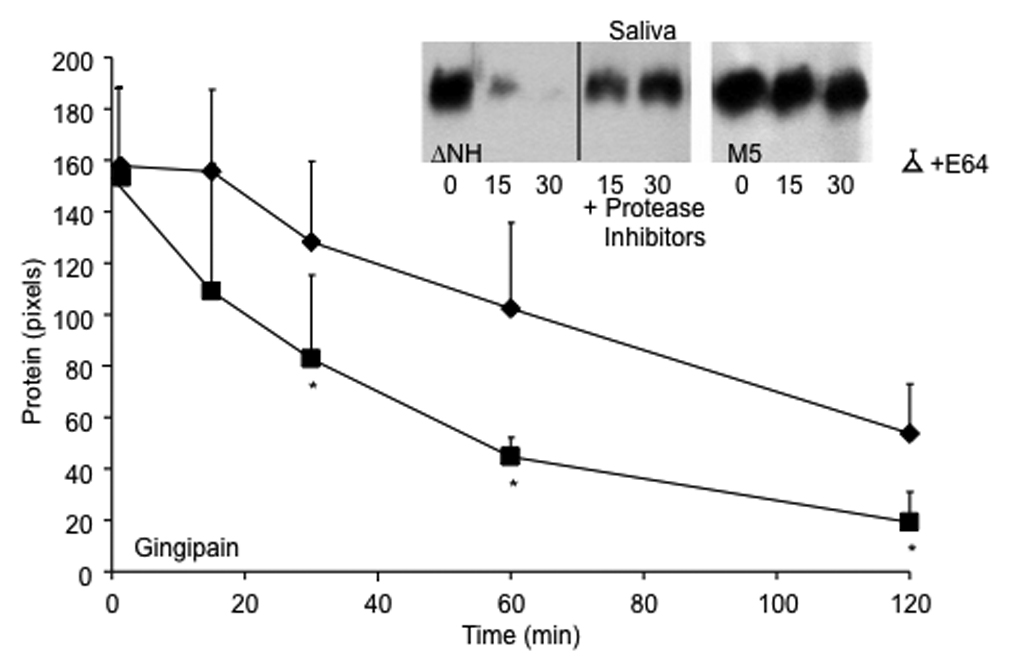

The relatively high rate of loss of hydrophobicity by the ΔNH2 mutant exposed to gingipain was associated with a significantly higher rate of reduction of M protein extractable from the surface of the streptococci (Figure 5). Hot acid extracts of the parent strain exposed to gingipain for short periods of time contained immunoreactive M5 protein. In contrast, the ΔNH2 mutant rapidly lost M5 protein detectable in hot acid extracts, suggesting that much of the M5 protein was degraded. In contrast, immunoreactive M5 protein was retained on the bacterial surface of the ΔNH2 mutant treated with gingipain in the presence of protease inhibitors, suggesting that the degradation of the surface protein was mediated by protease activity.

Figure 5.

Degradation of M protein on the streptococcal surface by gingipain (line graph) and saliva (inset). M5 strain (diamonds) and its ΔNH2 mutant (squares) were grown overnight in THB containing E64, washed in appropriate buffers and exposed to gingipain or saliva for the indicated time periods at 37°C in the absence and presence of a cocktail of protease inhibitors. To estimate the amount of M5 protein remaining on the streptococcal surface, the hot acid extract of the treated bacteria was spotted onto Protan membrane with a BioRad Bio-Dot manifold, blocked and overlaid with anti-PepM5 antiserum. Bound antibodies were detected by Pico-west and densitometry was performed using NIH Image as described in Materials and Methods. The amount of M protein was expressed as mean pixels of three experiments +/−S.D. The mean value for extracts from bacteria treated for 120 minutes with gingipain in buffer devoid of cysteine and supplemented with protease inhibitors (open triangle) were not significantly different from those shown for untreated bacteria determined at time zero. Asterisks denote significant differences between M5 strain and its ΔNH2 mutant. Similar results were obtained by treating the M5 wt (right gel, inset) and ΔNH2 mutant (left gel, inset) with human saliva. Supernatants were electrophoresed under reducing conditions and blotted to detect M5 protein as described in material and methods.

Because saliva contains proteases of bacterial origin [26], we tested the amount of degradation of the M proteins of both parent and ΔNH2 mutant GAS after exposure to saliva for various periods of time. The ΔNH2 mutant exposed to saliva lost its surface M5 protein at a faster rate than the parent M5 streptococci (Figure 5, inset). However, the ΔNH2 mutant retained its surface M protein following incubation in saliva supplemented with protease inhibitors, suggesting that the enhanced loss of M protein was the result of exposure to salivary proteases.

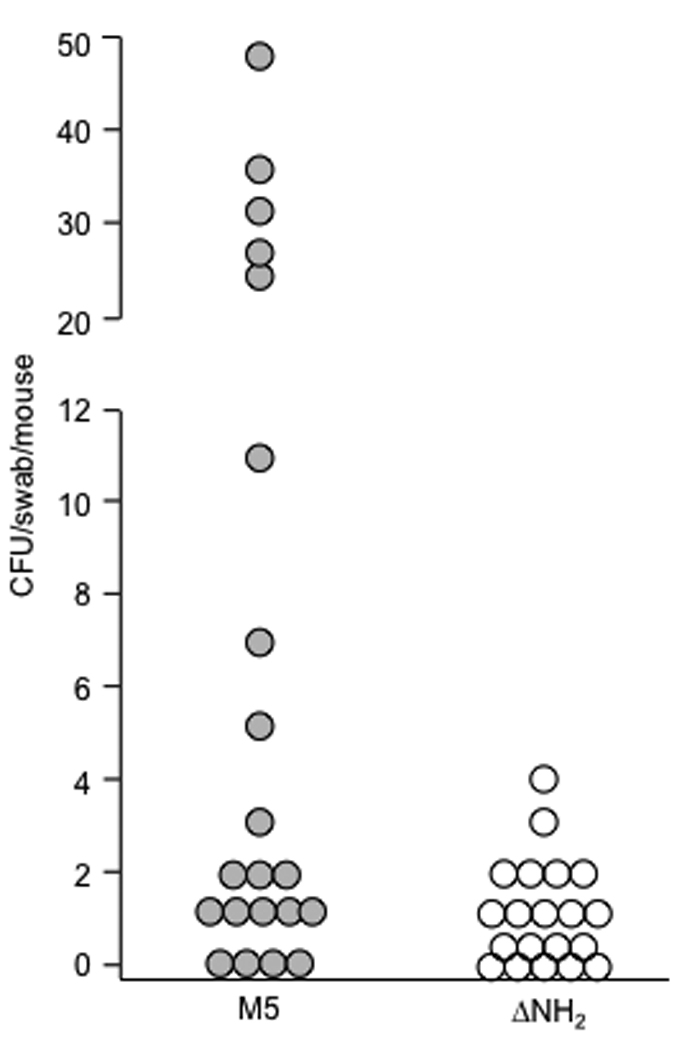

Taken together, the data indicate that the M protein expressed by the ΔNH2 mutant is more sensitive to proteases compared to the parent strain. The loss of M protein resulted in lower levels of LTA on the bacterial surface, a reduction in hydrophobicity and a reduction in adhesion to epithelial cells by the ΔNH2 mutant. These results suggested that the ΔNH2 mutant may also be impaired in its ability to adhere and to colonize mucosal surfaces of the host. To test this hypothesis, mice were infected with the parent and ΔNH2 strains of GAS via the intranasal route and were then assayed for colonizing bacteria. We were unable to detect streptococci in throat swabs obtained 24 hours following infection, consistent with previous studies showing relative low virulence of the M type 5 streptococci administered via the intranasal route (Dale, JB unpublished). However, the results at an earlier time point (6 h) showed a significant reduction in colonization by the ΔNH2 mutant compared to the parent strain (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Colonization of the upper respiratory tract of mice infected intranasally with M5 and its ΔNH2 mutant. Mice were infected intranasally with wt M5 (closed circles) and ΔNH2 mutant (open circles) grown in THB overnight, washed and resuspended to an O.D. of 1.00. Six hours after inoculation the oral cavity of each mouse was swabbed and the swabs were plated onto blood agar. The number of beta-hemolytic colonies was recorded after 24 hours incubation. There was a significant difference in colonization between wt M5 (mean 9.97+/− 3.1 CFU, median 1 CFU) and ΔNH2 mutant (mean 1.0+/−0.26 CFU, median 0 CFU) infected mice (p<0.05, Wilcoxon test).

Discussion

The results of the present study indicate that the structure of the NH2-terminal region of M5 may impart an important functional characteristic in addition to containing protective epitopes. The NH2-terminal region confers upon the M protein partial protection against proteolytic digestion by cysteine proteases or trypsin-like proteases. In the host, one likely source of proteases would be those secreted by the normal bacterial flora of the oral cavity and, hence, frequently found in saliva [25, 27, 28]. One such protease is gingipain, produced by P. gingivalis. As a result of the enhanced sensitivity of the ΔNH2 M5 protein to cysteine protease, the organism exhibited a more rapid loss of its M protein. As a consequence, the surface exposed LTA that is complexed with M protein was also lost and this was associated with a reduction in hydrophobicity and in the level of streptococcal adhesion to epithelial cells. These results are consistent with previous findings showing a major role for surface LTA in conferring hydrophobicity and in facilitating adhesion to epithelial cells [13, 23]. The increased sensitivity to proteases may be a result of the coiled-coil structure of M proteins becoming less stable and more prone to unwinding in the absence of the NH2-terminal region. This notion is supported by previous studies showing that limited pepsin digests of the M protein from type 57 GAS produced monomeric fragments that lacked the NH2-terminal region while fragments containing the NH2-terminus formed stable dimers [7]. Similar results were observed with M6 protein. These earlier studies suggested that the NH2-terminal region of M proteins may in some way stabilize the coiled-coil structure. It is tempting to speculate that the M5 protein devoid of its NH2-terminus may uncoil on the surface of the organisms and that this results in increased sensitivity to endogenous or environmental proteases. Alternatively, the reduction in protein-bound LTA and/or a concomitant reduction in hydrophobicity may somehow enhance access of proteases to M protein cleavage sites.

In this study, we also showed that initial colonization of mice by the ΔNH2 mutant was markedly impaired as compared to the parent strain. This finding is consistent with the observations that the ΔNH2 M5 mutant was less hydrophobic, contained less protein bound LTA on its surface and showed lower levels of adhesion to epithelial cells in vitro than the parent strain. The oropharynx is the primary site of GAS entry into the human host. During symptomatic infection saliva contains high levels of GAS. Following infection, smaller numbers of organisms may persist in the throat for weeks. Both states of mucosal colonization are important reservoirs that permit the organisms to be maintained in the environment since they are human-specific pathogens. Initial colonization during infection and asymptomatic colonization of the mucosa require the organisms to exhibit a number of biological functions to escape the innate immune system of the oral cavity, including antimicrobial peptides, low levels of essential nutrients [29] and, as proposed in this study, relative resistance to proteolytic attack. In GAS that express only a single M protein, such as serotype 5, the resistance of M protein to proteolytic digestion may be critical to maintaining the biological functions of the bacterial surface that are important determinants in the pathogenesis of infection.

The NH2-terminal regions of M proteins have been the subject of numerous previous studies [reviewed in [30]]. Although a recent study showed that deletion of the N-terminal 59 amino acids of M5 resulted in attenuated virulence in mice [31], our results indicate that the extreme N-terminal peptide region is not required for virulence when the organisms are administered via the intraperitoneal route. Aside from eliciting bactericidal antibodies, no other specific virulence properties have previously been ascribed to the "tip" region of the M protein. However, a number of observations suggest that maintaining specific NH2-terminal structures within the species and within a serotype is of critical importance: 1) the majority of clinical isolates within the same serotype express M proteins with NH2-terminal sequences that are identical [32, 33], 2) when variant "subtypes" of M proteins are expressed, the NH2-terminal sequence usually varies from that of the predominant strain by only one or two amino acids, a structural difference which does not have a major effect on opsonic antibody binding [34], and 3) the type-specific sequences of M proteins have been remarkably conserved for decades, even under immense immunological pressure (http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/biotech/strep/strepblast.htm). These observations suggest that the NH2-terminal structures of M proteins may be constrained by a function that is independent of that required for eliciting opsonic antibodies. To our knowledge, this is the first study showing a potential role for this region of the M protein in the biological function of the bacterial surface. Constraints in the amino acid sequences that are able to confer relative resistance to proteases, independent of the precise mechanism, could explain the persistence of type-specific structures in the GAS population as opposed to a myriad of potential epitopes that could equally serve as binding sites for opsonic antibodies.

Acknowledgments

The expert technical assistance of Valerie Long is greatly appreciated. Dr. Ofek contributed to these studies during a sabbatical leave from Tel Aviv University as the Gene H. Stollerman, MD Distinguished Visiting Scientist at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center.

Supported by research funds from NIH/NIAID USPHS Grants AI10085 and AI60592 (J.B.D.) and research funds from the Department of Veterans Affairs (J.B.D., D.L.H. and H.S.C.).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Thomas A. Penfound – No conflict; Itzhak Ofek – No conflict; Harry S. Courtney – No conflict; David L. Hasty – No conflict; James B. Dale is the inventor of certain technologies related to the development of M protein-based group A streptococcal vaccines. The technology has been licensed from the University of Tennessee Research Foundation to Vaxent, LLC in which Dr. Dale has a financial interest and also serves as the Chief Scientific Officer

The data contained in this manuscript have not previously been reported in meetings or in abstract form.

References

- 1.Navarre WW, Schneewind O. Surface proteins of gram-positive bacteria and mechanisms of their targeting to the cell wall envelope. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:174–229. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.1.174-229.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dale JB, Beachey EH. Localization of protective epitopes of the amino terminus of type 5 streptococcal M protein. J Exp Med. 1986;163:1191–1202. doi: 10.1084/jem.163.5.1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu M, Walls M, Stroop S, Reddish M, Beall B, Dale J. Immunogenicity of a 26-Valent Group A Streptococcal Vaccine. Infect Immun. 2002;70:2171–2177. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.4.2171-2177.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kotarsky H, Gustafsson M, Svensson HG, Zipfel PF, Truedsson L, Sjobring U. Group A streptococcal phagocytosis resistance is independent of complement factor H and factor H-like protein 1 binding. Mol Microbiol. 2001;41:817–826. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlsson F, Sandin C, Lindahl G. Human fibrinogen bound to Streptococcus pyogenes M protein inhibits complement deposition via the classical pathway. Mol Microbiol. 2005;56:28–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sandin C, Carlsson F, Lindahl G. Binding of human plasma proteins to Streptococcus pyogenes M protein determines the location of opsonic and non-opsonic epitopes. Mol Microbiol. 2006;59:20–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khandke KM, Fairwell T, Braswell EH, Manjula BN. The amino-terminal region of group A streptococcal M protein determines its molecular state of assembly and function. J Protein Chem. 1991;10:49–59. doi: 10.1007/BF01024655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ofek I, Simpson WA, Beachey EH. Formation of molecular complexes between a structurally defined M protein and acylated or deacylated lipoteichoic acid of Streptococcus pyogenes. J Bacteriol. 1982;149:426–433. doi: 10.1128/jb.149.2.426-433.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Courtney HS, Ofek I, Penfound T, et al. Relationship between expression of the family of M proteins and lipoteichoic acid to hydrophobicity and biofilm formation in Streptococcus pyogenes. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4166. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller L, Burdett V, Poirier TP, Gray LD, Beachey EH, Kehoe MA. Conservation of protective and nonprotective epitopes in M proteins of group A streptococci. Infect Immun. 1988;56:2198–2204. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.8.2198-2204.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maguin E, Prevost H, Ehrlich SD, Gruss A. Efficient insertional mutagenesis in lactococci and other gram-positive bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:931–935. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.3.931-935.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beachey EH, Stollerman GH, Chiang EY, Chiang TM, Seyer JM, Kang AH. Purification and properties of M protein extracted from group A streptococci with pepsin: Covalent structure of the amino terminal region of the type 24 M antigen. J Exp Med. 1977;145:1469–1483. doi: 10.1084/jem.145.6.1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ofek I, Whitnack E, Beachey EH. Hydrophobic interactions of group A streptococci with hexadecane droplets. J Bacteriol. 1983;154:139–145. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.1.139-145.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raeder R, Woischnik M, Podbielski A, Boyle MD. A secreted streptococcal cysteine protease can cleave a surface-expressed M1 protein and alter the immunoglobulin binding properties. Res Microbiol. 1998;149:539–548. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(99)80001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Potempa J, Mikolajczyk-Pawlinska J, Brassell D, et al. Comparative properties of two cysteine proteinases (Gingipains R), the products of two related but individual genes of porphyromonas gingivalis. JBC. 1998;273:21648–21657. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.34.21648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ofek I, Beachey EH, Jefferson W, Campbell GL. Cell membrane-binding properties of group A streptococcal lipoteichoic acid. J Exp Med. 1975;141:990–1003. doi: 10.1084/jem.141.5.990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hogg SD, Old LA. The wall associated lipoteichoic acid of Streptococcus sanguis. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 1993;63:29–34. doi: 10.1007/BF00871728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reed LJ, Muench H. A single method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am J Hyg. 1938;27:493. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim CC, Monack D, Falkow S. Modulation of virulence by two acidified nitriteresponsive loci of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Infect Immun. 2003;71:3196–3205. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3196-3205.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ofek I, Courtney HS, Schifferli DM, Beachey EH. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for adherence of bacteria to animal cells. J Clin Microbiol. 1986;24:512–516. doi: 10.1128/jcm.24.4.512-516.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lyon WR, Madden JC, Levin JC, Stein JL, Caparon MG. Mutation of luxS affects growth and virulence factor expression in Streptococcus pyogenes. Mol Microbiol. 2001;42:145–157. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loughman JA, Caparon M. Regulation of SpeB in Streptococcus pyogenes by pH and NaCl: a model for in vivo gene expression. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:399–408. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.2.399-408.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hasty DL, Ofek I, Courtney HS, Doyle RJ. Multiple adhesins of streptococci. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2147–2152. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.6.2147-2152.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beachey EH, Ofek I. Epithelial cell binding of group A streptococci by lipoteichoic acid on fimbriae denuded of M protein. J Exp Med. 1976;143:759–771. doi: 10.1084/jem.143.4.759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fingleton B, Menon R, Carter KJ, et al. Proteinase activity in human and murine saliva as a biomarker for proteinase inhibitor efficacy. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:7865–7874. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eley BM, Cox SW. Proteolytic and hydrolytic enzymes from putative periodontal pathogens: characterization, molecular genetics, effects on host defenses and tissues and detection in gingival crevice fluid. Periodontol 2000. 2003;31:105–124. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2003.03107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soder P, Modeer T. Characterization of trypsin-like enzymes from human saliva isolated by affinity chromatography. Acta Odont Scand. 1997;35:41–50. doi: 10.3109/00016357709055989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gazi MI, Cox SW, Clark DT, Eley BM. A comparison of cysteine and serine proteinases in human gingival crevicular fluid with tissue, saliva and bacterial enzymes by analytical isoelectric focusing. Arch Oral Biol. 1996;41:393–400. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(96)00007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tart AH, Walker MJ, Musser JM. New understanding of the group A Streptococcus pathogenesis cycle. Trends Microbiol. 2007;15:318–325. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dale JB. Group A streptococcal vaccines. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1999;13:227–243. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70052-0. viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Waldemarsson J, Stalhammar-Carlemalm M, Sandin C, Castellino FJ, Lindahl G. Functional dissection of Streptococcus pyogenes M5 protein: the hypervariable region is essential for virulence. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7279. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shulman ST, Tanz RR, Kabat W, et al. Group A streptococcal pharyngitis serotype surveillance in North America, 2000–2002. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:325–332. doi: 10.1086/421949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O'Loughlin RE, Roberson A, Cieslak PR, et al. The epidemiology of invasive group A streptococcal infection and potential vaccine implications: United States, 2000–2004. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:853–862. doi: 10.1086/521264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dale JB, Penfound T, Chiang EY, Long V, Shulman ST, Beall B. Multivalent group A streptococcal vaccine elicits bactericidal antibodies against variant M subtypes. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2005;12:833–836. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.7.833-836.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]