Abstract

Background

Excessive sway during quiet standing is a common sequela of chronic alcoholism even with prolonged sobriety. Whether alcoholic men and women who have remained abstinent from alcohol for weeks to months differ from each other in the degree of residual postural instability and biomechanical control mechanisms has not been directly tested.

Method

We used a force platform to characterize center-of-pressure biomechanical features of postural sway, with and without stabilizing conditions from touch, vision, and stance, in 34 alcoholic men, 15 alcoholic women, 22 control men, and 29 control women. Groups were matched in age (49.4 years), general intelligence, socioeconomic status, and handedness. Each alcoholic group was sober for an average of 75 days.

Results

Analysis of postural sway when using all 3 stabilizing conditions vs. none revealed diagnosis and sex differences in ability to balance. Alcoholics had significantly longer sway paths, especially in the anterior-posterior direction, than controls when maintaining erect posture without balance aids. With stabilizing conditions the sway paths of all groups shortened significantly, especially those of alcoholic men, who demonstrated a 3.1-fold improvement in sway path difference between the easiest and most challenging conditions; the remaining 3 groups, each showed a ~2.4-fold improvement. Application of a mechanical model to partition sway paths into open-loop and closed-loop postural control systems revealed that the sway paths of the alcoholic men but not alcoholic women were characterized by greater short-term (open-loop) diffusion coefficients without aids, often associated with muscle stiffening response. With stabilizing factors, all four groups showed similar long-term (closed loop) postural control. Correlations between cognitive abilities and closed-loop sway indices were more robust in alcoholic men than alcoholic women.

Conclusions

Reduction in sway and closed-loop activity during quiet standing with stabilizing factors shows some differential expression in men and women with histories of alcohol dependence. Nonetheless, enduring deficits in postural instability of both alcoholic men and alcoholic women suggest persisting liability for falling.

Keywords: balance, alcohol, alcoholism, gender, posturography, postural stability, musculoskeletal response mechanism

INTRODUCTION

Excessive sway during quiet standing is a common and significant sequela of chronic alcoholism even following prolonged sobriety and can lurk as a liability for morbidities associated with falls. Understanding the physiological and central nervous system mechanisms underlying alcoholism-related postural instability could provide insight into the scope and limits of functional recovery or remedies providing functional compensation. Further, recognizing that the patterns of functional sparing and impairment and recovery rates can differ in alcoholic men and women suggests the possibility that different physiological mechanisms could underlie alcoholism-related functional changes depending on sex.

Despite evidence for some recovery with abstinence from alcohol (Diener et al., 1984b; Fellgiebel et al., 2004; Victor et al., 1989), ataxia can persist in chronic alcoholics, even those without complications from Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome (Diener et al., 1984b; Ledin and Odkvist, 1991) or peripheral neuropathy (Scholz et al., 1986). Our previous studies indicated that, relative to control men, alcoholic men showed signs of imbalance while standing on one foot or heel-to-toe on two feet (Romberg stance) (Sullivan et al., 2000b) even in the absence of signs of ataxia measured with quantitative heel-to-shin tests of lower limb ataxia (Sullivan et al., 2002a). The balance impairment was substantial and disproportionately large, with the scores of the alcoholic men being approximately 1.2 SD lower than control men, and lower than their concurrent cognitive deficits, which were about .6 SD for executive functions and .7 SD for visuospatial functions (Sullivan et al., 2000b). Force platform measurement of sway during quiet standing is a sensitive measure of alcoholism-related postural imbalance (Wober et al., 1998). In another group of alcoholic men, sober for about 2 months, we described longer center-of-pressure sway paths than control men. The alcoholics also exhibited sway prominence in the form of physiological tremor (frequency of peak sway velocity), which was notable at two frequency bands, 2–5 Hz and 5–7 Hz (Sullivan et al., 2006). In both studies, measures of greater imbalance correlated selectively with smaller volumes of anterior superior vermis of the cerebellum and not with other measures of brain, including the cerebellar hemispheres (Sullivan et al., 2000a; Sullivan et al., 2006). Thus, instability in the stance of detoxified alcoholic men is replicable, prolonged, and significant. Further, these studies indicate selective physiological (tremor in specific frequency bands) and neural (cerebellar vermis) mechanisms underlying the observed residual postural instability (cf., Diener et al., 1984c; Gilman et al., 1990; Mauritz et al., 1979; Victor et al., 1989).

Like alcoholic men, alcoholic women exhibit signs of postural instability when balancing on one foot or standing heel-to-toe. These impairments were observed following an average of 3.6 months of sobriety (Sullivan et al., 2002b) and without concomitant signs of lower limb, heel-to-shin ataxia (Sullivan et al., 2002a). Unlike the salient balance impairment in the alcoholic men, however, the balance impairment of the alcoholic women was relatively mild (.5 SD) and less than their concurrent impairments in working memory (1 SD) and visuospatial ability (.76 SD) (Sullivan et al., 2002b). Longitudinal testing of a subset of those alcoholic women indicated some recovery of balance ability after 1 year of sobriety but with enduring instability (standing on one foot) even after 4 years of sobriety and despite concurrent recovery in working memory and psychomotor speed (Rosenbloom et al., 2004). The improvement in balance between 3.6 and 12 months of sobriety correlated modestly with shrinkage of the fourth ventricle, an indirect index of expansion of surrounding tissue, including the cerebellum, and suggestive of a neural substrate of the functional improvement (Rosenbloom et al., 2007).

Recently, we used the same force platform paradigm used with sober alcoholic men to examine a new cohort of alcoholic women, abstinent from alcohol for an average of about 2 months (Sullivan et al., 2009b). The alcoholic men and women showed a number of fundamental similarities in their pattern and source of impairments. Specifically, both alcoholic men and alcoholic women demonstrated significantly longer sway paths than their age- and sex-matched controls; sway was more pronounced in the anterior-posterior than medial-lateral direction; truncal tremor was greatest in the 5–7 Hz band that is indicative of damage to cerebellar-thalamic relays (Deuschl et al., 1998); and longer sway paths correlated selectively with smaller volumes of the anterior superior vermis of the cerebellum. A fundamental difference, however, was notable between the sexes in their ability to use tactile, vision, and stance information to reduce sway: although alcoholic men and women both showed significant sway reduction with stabilizing conditions, the improvement was disproportionately great in the alcoholic men, whose balance fully normalized (Sullivan et al., 2006). By contrast, despite significant improvement, the sway of the alcoholic women never reduced to normal levels (Sullivan et al., 2009b).

The current analysis was aimed at parsing the sway path data, used in our previous reports, into open-loop and closed-loop components of postural control through application of a statistical biomechanical model (Collins and De Luca, 1993; Collins and De Luca, 1995; Collins et al., 1995). The objective was to gain insight into musculoskeletal coordination mechanisms used to maintain stability during quiet standing that would potentially distinguish alcoholics from controls and identify disease- and sex-specific liabilities for falling. As previously summarized (Sullivan et al., 2009c), the model treats the sway path like a system of coupled, correlated random walks that can be characterized by a diffusion coefficient. As applied to the maintenance of erect static posture, the diffusion coefficient plot of successive temporal interval displacements reveals two distinct components: a short-term (i.e., short time interval, usually less than two seconds) and a long-term (i.e., greater than two second) component. The short-term component behaves like an open-loop control system that is mostly devoid of feedback, whereas the long-term component behaves like a closed-loop system with feedback based on afferent input. The open-loop component of postural control is little affected by attentional or other cognitive processes and is characterized by a steep-sloped activity gradient (Collins and De Luca, 1995; Diener et al., 1989; Jeka et al., 1997). The steeper the slope of the diffusion plot components, the less tightly regulated and more random the control mechanisms. While brief, the open-loop component is prolonged in healthy aging and can be a source of instability, possibly related to muscle stiffening. Although a useful mechanism for correction of small perturbations to balance, when excessive such stiffening produces inflexibility and becomes difficult to control and may itself induce instability. The closed-loop component can be affected by internal and external perceptual information and cognitive demands (Raymakers et al., 2005), and poor closed-loop control has been associated with age-related declines in cognitive status (Sullivan et al., 2009c).

We have used this biomechanical model to characterize components of static postural control in larger groups of healthy men and women, from whom the controls in the current study were drawn. The average time that women switched from open to closed loop control was shorter in the difficult than easy condition, whereas the opposite pattern described the switch by the men (Sullivan et al., 2009c). Here, we used this diffusion model to determine the extent to which alcoholism-related prolongation of the open-loop component could be shortened with sensory input, whether alcoholic men and women differed in their diffusion components, and whether evidence for improvement with stabilizing forces could be related to measures of attentional and visuospatial abilities, which are commonly compromised in recovering alcoholics (e.g., Beatty et al., 1996; Fama et al., 2004; Fein et al., 2009; Müller-Oehring et al., 2009; Sullivan et al., 2000b; for review Oscar-Berman and Marinkovic, 2007).

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Subjects

The subject groups comprised 34 alcoholic men, 15 alcoholic women, 22 control men, and 29 control women. All subjects underwent structured interview to identify the following exclusionary criteria: presence of DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) Axis I diagnoses of Bipolar Disorder or Schizophrenia, history of nonalcohol substance dependence, alcohol-related amnestic disorder, CNS trauma, loss of consciousness for greater than 30 minutes, seizures not related to alcohol withdrawal, neurodegenerative disease, or serious medical condition (such as type 2 diabetes, epilepsy, cancer treated with radiation or chemotherapy, HIV infection). All subjects were volunteers, gave written informed consent, obtained according to the Declaration of Helsinki and the Ethical Committee of Stanford University School of Medicine and SRI International, to participate in this study and were paid a modest stipend for participation. Before testing, all participants had breath alcohol determination and were not tested if the level exceeded 0.

The groups did not differ significantly in age, estimated premorbid IQ (National Adult Reading Test (Nelson, 1982)), socioeconomic status, or handedness (Crovitz and Zener, 1962) (Table 1). More alcoholics were current smokers than controls (χ2=25.76, p=.0001), but the number of smoking men vs. women did not differ within a diagnosis. The alcoholic men and women had similar levels of education but less than the control men and women. Although the alcoholic men scored the lowest of all groups on the Dementia Rating Scale (Mattis, 1988), all participants scored well within the normal range.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics of the four study groups: Mean(±SD) or frequency count

| Control Men | Control Women | Alcoholic Men | Alcoholic Women | ANOVA p-value Follow-up t-tests |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 22 | 29 | 34 | 15 | |

| Age | 48.7 (10.30) | 49.4 (8.98) | 50.3 (8.24) | 49.4 (8.76) | n.s. |

| Education (years) | 16.5 (1.87) | 16.0 (2.10) | 14.9 (2.60) | 14.7 (2.34) | .0286 CM>AM=AW |

| Socioeconomic status (SES)a | 19.5 (8.41) | 23.1 (8.52) | 26.4 (14.10) | 25.2 (8.22) | n.s. |

| Handednessb | 19.2 (5.28) | 24.8 (18.41) | 23.6 (13.62) | 22.1 (13.35) | n.s. |

| Body Mass Index | 27.5 (4.79) | 25.1 (4.51) | 27.4 (4.35) | 22.1 (3.24) | .0006 CM=AM; CF>AF |

| Current smokers | 13.6% | 24.1% | 70.6% | 66.7% | .0001 CM=CF<AM=AF |

| Lifetime alcohol consumption (kg) | 67.7 (77.68) | 35.3 (34.74) | 1068.8 (913.91) | 432.6 (313.20) | .0001 AM>CM; AM>AW; AW>CW |

| Days soberc | — | — | 93.6 (122.5) | 90.7 (117.6) | n.s. |

| NART IQ | 112.3 (5.92) | 114.4 (5.70) | 110.4 (8.24) | 114.1 (5.30) | n.s. |

| Dementia Rating Scaled | 139.9 (3.41) | 141.0 (2.49) | 138.4 (4.21) | 139.5 (2.42) | .0349 CW>AM |

| WASI | |||||

| VIQ | 112.1 (14.30) | 113.9 (11.69) | 108.8 (12.83) | 109.7 (10.70) | n.s. |

| PIQ | 114.3 (13.46) | 116.8 (10.29) | 107.9 (14.06) | 103.8 (11.24) | 0.0043 CF>AM=AF; CM>AF |

| FSIQ | 115.0 (14.51) | 117.4 (10.97) | 109.6 (13.5) | 107.9 (10.3) | .0382 CF>AM=AF |

| WMS-R | |||||

| General Memory Index | 111.7 (17.44) | 119.1 (13.45) | 100.1 (18.03) | 107.6 (16.89) | .0003 CM>AM; CF>AF |

| Attention Index | 108.7 (18.74) | 109.3 (13.35) | 103.2 (17.27) | 102.3 (10.05) | n.s. |

Lower scores indicate higher SES

Right handedness = 14–32; left handedness = 50–70 (Crovitz and Zener, 1962)

Including 3 men and 2 women with outlying values; see text for full description

Dementia cut-off<124; no one scored at or below this cut-off

On average, the alcoholics consumed about 12 times more alcohol over their lifetime (t(41)=6.47, p=.0001) and had a lower body mass index (t(42)=2.25, p=.0298) than the controls. Years of alcoholic drinking ranged from 5 to 37 years (15±9.2 years). Each alcoholic group was sober for about 3 months, which included outliers: 2 alcoholic women whose lengths of sobriety were 365 and 393 days, and 3 alcoholic men were sober for 220, 240, and 732 days. Exclusion of these outliers resulted in average lengths of sobriety to be 64 days for the men and 47 days for the women (t(42)=1.94, p=.0611).

A falls questionnaire (Tinetti et al., 1995a; Tinetti et al., 1995b) provided an estimate of falls experienced and remembered over the past year, regardless of drinking status in 85 of the 100 subjects. As a group, alcoholics reported falling on more occasions than non-alcoholics (χ2=8.65, p=.0132). This difference was significant between alcoholic and control men (p=.0263) but not between alcoholic and control women (p=.44).

Posturography

Data Acquisition and Sway Path Analysis

A force platform was used to characterize physiological features of postural sway and tremor, with and without stabilizing factors from touch, vision, and stance. As previously described (Sullivan et al., 2006), balance was assessed with a microcomputer-controlled force plate measurement device (model 9284; Kistler, Amherst, NY, U.S.A) with multiple transducers and analog-digital converters. Data were sampled at 50 Hz; the resultant native data were 30-sec trials of 1500 center of pressure displacements (x–y pairs). The sway path length was expressed as the line integral following 10 Hz non-recursive lowpass filtering (7 terms, −50 db Gibbs). See Figure 1a and b for examples of sway paths.

Figure 1.

Figure 1a. Examples of sway paths for one trial performed by a 49 year-old control man (top) and a 52 year-old alcoholic man (bottom). Figure 1b. Examples of sway paths for one trial performed by a 49 year-old control woman (top) and a 49 year-old alcoholic woman (bottom). In both pairs of sway paths, the left panel displays performance without any stabilizing aid, and the right panel shows performance when provided all three stabilizing aids. Note the exaggerated sway path in the no-aid condition of the alcoholic man and alcoholic woman.

Test Conditions

The experimental conditions of stabilizing factors undergone during quiet standing on the force platform were visual (eyes open or closed), stance (feet apart or feet together), and touch (touch or no touch). In the touch conditions, subjects placed their right-hand index finger on a device made of a break-away piece of plastic tubing, incapable of bearing body weight and affixed to a vertical pole, also made of plastic tubing and adjustable to the height of a subject. In all non-touch conditions, subjects relaxed their arms and hands at their sides. Subjects stood barefoot in the center of the platform for three, 30-sec trials for each of the eight combinations of conditions, which were presented in balanced order across subjects. For the purpose of data reduction and in light of our previous findings (Sullivan et al., 2006; Sullivan et al., 2009c), the analyses in the current study were restricted to comparisons of the two extreme conditions: balancing without any stabilizing factors vs. balancing with all three stabilizing factors (touch, vision, and stance). We chose to collapse the conditions for several reasons. Firstly, the primary sway path data, on which the current biomechanical analysis is based, have already been parsed and published; thus we sought to present the new analyses as efficiently as possible. Providing analyses based on the conditions known to produce the largest differences seemed the most conservative approach to take. Secondly, the most dramatic stabilizing factor in any analysis was the change from a narrow stance to a broad-based stance. This type of physical change in stability would, in turn, exert a substantial influence on the biomechanical analysis used because it is especially sensitive to variation in sway and anti-sway (sway correction).

Although these data are taken from prior studies (Sullivan et al., 2006; Sullivan et al., 2009a; Sullivan et al., 2009c), the comparisons between alcoholic men and women has not been previously made, and the balance platform data of the alcoholic groups have not been subjected to the biomechanical analysis described herein.

Biomechanical Analysis of Sway Path Components

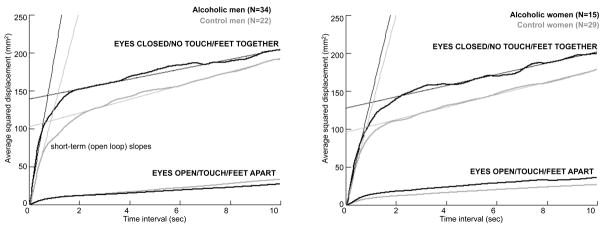

We applied the stabilogram-diffusion analysis of Collins and colleagues (Collins and De Luca, 1993; Collins et al., 1995) to compute the characteristics of open-loop (short-term) and closed-loop (long-term) control mechanisms. The first step was the computation of the average square planar displacement (pd2) across the entire data set computed for 499 time intervals (m) from .02 to 10 sec in .02 sec increments. Thus, the average squared displacement (pd2) was computed for all pairs of points separated sequentially by .02 sec for the first interval, .04 sec for the second, .06 sec for the third…10 sec for the 499th. Figure 2 provides visual examples of the slopes of the open-loop and closed-loop components of the diffusion model and the critical point, displayed the averages for the two conditions for each subject group.

Figure 2.

Group averages of the average squared displacement of pairs of points over time for the alcoholic and control men (left panel) and alcoholic and control women (right panel). The top pair of curves in each panel displays the group averages of the alcoholics (black lines) and controls (gray lines) in the no stabilizing aid condition; the bottom pairs display the group averages of each group with all three stabilizing aids. The fast rising arm of the curves reflects the short-term, open-loop component of the sway diffusion, and the flatter sloped curve reflects the long-term, closed-loop component. Also noted are the critical points, which mark the change over from the open to closed loop components.

Three diffusion plots were created (x-axis = medial-lateral displacement, y-axis = anterior-posterior displacement, and xy = average squared radial displacement) with the 499 displacements plotted against the 499 time intervals. The plots were then fit with two separate linear components, the short-term diffusion coefficient (DS) reflecting the open-loop characteristics and the long-term diffusion coefficient (DL) reflecting the closed-loop characteristics. The critical point (CP) was the time interval at which the two linear components intersected such that a longer CP time interval indicates more time spent in the short-term relative to the long-term component. The dependent variables from these analyses were DS=one half the slope of the linear fit of the open-loop component, DL=one half the slope of the linear fit of the closed-loop component, and the CP (Figure 2).

Neuropsychological Tests

The participants were given the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised (WMS-R) (Wechsler, 1981) and Wechsler Adult Scale of Intelligence (WASI) (Wechsler, 1999); subtest mean±SD scores and group differences are presented in Table 1. Focusing on the alcoholic groups, we tested the hypothesis that poorer performance on measures of attention (WMS-R Attention Index) and visuospatial abilities (WASI Performance IQ) would be correlated with the long-term sway path component, which theoretically can be influenced by cognitive control, but not the short-term sway path component, which is relatively free of cognitive control.

Statistical Analysis

Balance platform data were subjected to a series of repeated measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs; 4 groups by 2 extreme balance conditions) conducted on summary scores, which served as a means of data reduction, thereby minimizing the number of comparisons made. Secondary ANOVAs included only the alcoholic groups and tested sex by balance conditions. The summary scores were the mean measure (sway path length, peak frequency of sway velocity, or short-term/long-term slopes) of 3 trials of each of the two extreme conditions of difficulty, with the easiest condition being eyes open/feet apart/touch and the most difficult condition being eyes closed/feet together/no touch. Correlations between cognitive test performance and components of the sway path were conducted separately for alcoholic men and alcoholic women with Pearson directional correlations, with the prediction that diffusion coefficients in the abnormal direction (steeper lopes in the long-term, closed loop component) would be correlated with lower cognitive performance scores.

RESULTS

As a context for the biomechanical analysis, we first compare differences among the four groups (control and alcoholic men and women) and then focus on differences between alcoholic men and women in sway path traversed under the two extreme experimental conditions: without any stabilizing factors vs. with all three visual, tactual, and stance stabilizing factors.

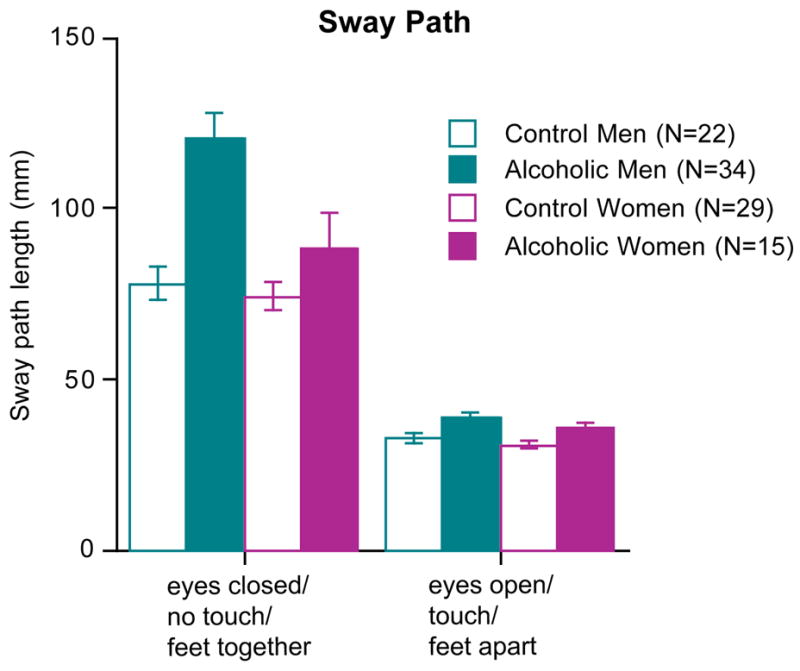

Sway Path Length

Analysis of the two extreme balance conditions revealed diagnosis and sex differences in sway path traversed. In particular, alcoholics had significantly longer sway paths than controls when maintaining erect posture without stabilizing conditions (F(3,96)=12.67, p=.0001). With stabilizing conditions the sway paths of all groups shortened significantly, especially those of alcoholic men (group-by-condition interaction F(F3,96)=9.71, p=.0001), whose sway path difference between the easiest and most challenging conditions showed a 3.1-fold improvement compared with the remaining 3 groups, each showing a ~2.4-fold improvement (Figures 1 and 2). This sex-by-condition interaction endured when only the two alcoholic groups were compared (F(1,47)=5.35, p=.0251).

Sway Path Components Derived from a Biomechanical Model

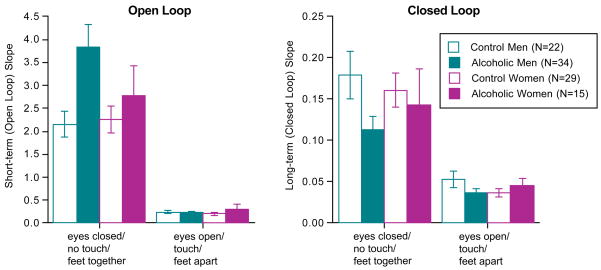

Application of a biomechanical model served to partition sway paths into short-term (theoretically, open-loop) and long-term (theoretically, closed-loop) components of postural control (Figure 3). Compared with the control groups, the sway paths of the alcoholic groups were characterized by greater short-term diffusion coefficients without than with stabilizing conditions (interaction F(3,96)=3.83, p=.0123). For the long-term component, the difference across the four groups was not itself significant (F(3,96)=1.86, p=.1411). Potential diagnostic differences, however, appeared to be attenuated by the performance of the alcoholic women, whose short-term vs. long-term diffusion coefficients were similar in pattern to those of the alcoholic men but were insignificantly different from either the alcoholic men or the control women (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Mean±SEM sway paths of the alcoholic and control men and women.

Consistent with our previous analysis of these men (Sullivan et al., 2006), the stabilogram of alcoholic men was characterized by a larger short-term coefficient (F(1,54)=6.74, p=.0121) and smaller long-term coefficient (F(1,54)=6.26, p=.0154) than the control men (Figure 4). The diffusion differences were disproportionately great in the alcoholic men when balancing without stabilizing conditions (group-by-condition interactions: short-term F(1,54)=7.08, p=.0102; long-term F(1,54)=2.35, p=.1311).

Figure 4.

Mean±SEM of the average squared displacement of pairs of points over time of the short-term (open loop) component (left panel) and the long-term (closed loop) component (right panel).

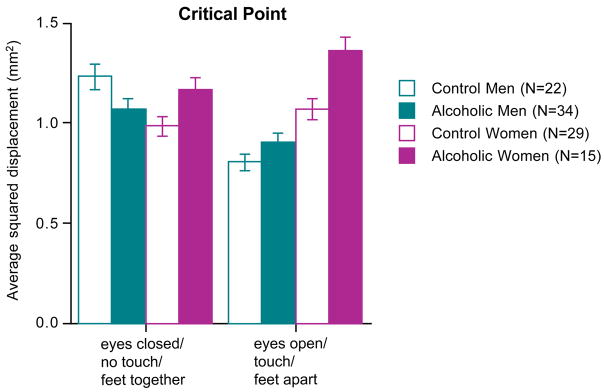

Group scores of the critical point, that is, the time interval at which the two linear components intersected, were subjected to a four group by two condition ANOVA. A trend in the group-by-condition interaction (F(3,96)=2.47, p=.0662) was followed up with separate one-way ANOVAs for each condition across the four groups. The group effect was not significant for the condition without stabilizing factors (F(3,96)=0.79, p=.5006) but was for the condition with stabilizing factors (F(3,96)=2.92, p=.0382) and was attributable to the high mean critical point of the alcoholic women (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Mean±SEM of the critical point between the short-term (open loop) component (left panel) and the long-term (closed loop) components of the sway path analysis.

Demographic Correlates of Sway Path Components

Analyzing the alcoholic men and women separately, neither age nor alcohol history (lifetime alcohol consumption, days since last drink) variables correlated with either short-term or long-term sway path components in either the easy or difficult conditions. Similarly, smoking status did not differentiate balance performance on any metric in either alcoholic group. Although we found no relation between smoking and balance scores, Durazzo et al. (Durazzo et al., 2007) observed that recently abstinent alcoholics who were also smokers had lower scores on toe-to-heel standing than their nonsmoking counterparts.

Cognitive Correlates of Sway Path Components

Again focusing on the two alcoholic groups, we tested the hypothesis that poorer performance on measures of attention (Attention Index) and visuospatial abilities (Performance IQ) would be related to the long-term but not the short-term sway path component. Within the alcoholic men, larger values of the long-term sway slope (DL) component in the condition without stabilizing factors correlated with higher (better) scores on the Attention Index (r=.40, p=.0194) and Performance IQ (r=.38, p=.028) and but not with Verbal IQ (r=.04, p=.84) (Figure 6). No other short-term or long-term component measure correlated with these cognitive scores in the alcoholic men.

Figure 6.

Correlations between cognitive test scores and the closed-loop values without stabilizing factors in the alcoholic men (top) and alcoholic women (bottom).

In contrast to the men, the alcoholic women failed to show any robust relationships between balance components and cognitive performance but did show one trend, confirmed with a nonparametric rank test, given the sample size. Specifically, larger values of the long-term sway slope (DL) component in the condition without stabilizing factors correlated with higher scores on the Verbal IQ (r=.46, p=.084; Rho=.57, p=.032) but not with Performance IQ (r=.26, p=.35; Rho=.34, p=.21) or the Attention Index (r=.06, p=.83; Rho=.17, p=.52) (Figure 6).

DISCUSSION

This set of analyses confirmed decades of clinical and experimental findings (e.g., Diener et al., 1984b; Mauritz et al., 1979; Sullivan et al., 2000a; Wober et al., 1999; Wober et al., 1998) that recovering alcoholics suffer instability of quiet standing even weeks to months they cease drinking. Beyond confirmation, the results provide novel evidence for similarities and differences in the sources of instability exhibited by alcoholic men and women and in the potential for stabilizing factors, lower limb musculoskeletal response, and cognitive processes to influence success in maintaining stability.

Conventional measures of sway path length indicated that alcoholic men and women exhibited greater sway than their age- and sex-matched controls. Characteristic alcoholic sway was in the anterior-posterior plane (cf., Diener et al., 1984b; Mauritz et al., 1979) and was greater in men than women. Although both alcoholic groups and both control groups took advantage of stabilizing factors obtained from visual and tactual information and broad-based stance, the improvement in stability was greater in the alcoholic men than any of the other subject groups. Specifically, the alcoholic men showed a 3.1-fold reduction in sway compared with a 2.4 fold reduction shown by the remaining three groups. That the alcoholic and control women showed the same degree of improvement with stabilizing factors indicates that the degree of sway never normalized in alcoholic women with such sensory and stance aids.

In an attempt to localize musculoskeletal factors that contribute to instability in quiet standing, we applied the biomechanical analysis of Collins and colleagues (Collins and De Luca, 1993; Collins and De Luca, 1995; Collins et al., 1995) to parse sway paths into open-loop and close-loop components. This diffusion model provided evidence for steeper slopes of the short-term, open-loop component in alcoholics as a group than controls, and this difference was greater without than with stabilizing information. A mechanistic interpretation of these contrasts indicates that without stabilizing aids, alcoholic men exhibited more unregulated sway control than control men by the open-loop system but more normally regulated sway control by the closed-loop system. High open-loop activity can be caused by muscle stiffening and bracing, which is marked especially when stabilizing factors are not available. Although muscle stiffening may be a useful mechanism for correction of small perturbations to balance, when excessive, such stiffening can produce inflexibility, which itself becomes difficult to control and has the potential to induce instability (Collins et al., 1995; Lauk et al., 1999). To the extent that measures of static posture are predictive of falling ((Shubert et al., 2006); but see (Baloh et al., 2003)), dwelling in the early, open-loop control system may put individuals at risk for falling by reducing their ability to take advantage of environmental information to enhance stability. Like older control men (Sullivan et al., 2006), alcoholic men were able to take advantage of sensory and stance aids to control sway even with open-loop control; however, neither age nor history of alcoholism in men detectably affected posture regulation by closed-loop control. Whether greater attentional and visuospatial cognitive abilities, which were correlated with greater closed-loop control, had a positive and causative effect on postural control remains to be tested.

Whereas the alcoholic men were disproportionately aided by stabilizing factors relative to control men, alcoholic women improved with such factors to the same degree as did control women. The sex differences can be interpreted as physiologically-based differences in strategies to reduce imbalance. The disproportionately later mean critical point of the alcoholic women when balancing with stabilizing information was indicative of poorly regulated sway control even when aided. The potential influence of verbal intelligence on closed-loop control in alcoholic women requires further testing and may be a significant factor in rehabilitative efforts in balance control.

Relevant to understanding musculoskeletal mechanisms of postural instability in chronic alcoholism, Diener et al. (Diener et al., 1984a) speculated that the 3Hz postural tremor associated with lesions of the anterior superior vermis, common in chronic alcoholism (for review Fitzpatrick et al., 2008) could be explained by an increase in EMG-recorded duration and amplitude of the long latency (antagonist) response of the anterior tibial muscle, the antagonist of the stretched triceps surae muscle. They attributed this abnormal antagonist response to damage of the anterior superior cerebellum. Previous studies of alcoholic men (Sullivan et al., 2006) and women (Sullivan et al., 2009c) noted that smaller volumes of the anterior superior vermis were predictive of greater sway and postural tremor, suggesting a central mechanism of disrupted control over agonist/antagonist lower limb muscular control.

In summary, alcoholic men and women demonstrated both similarities and differences in characteristic features of quiet standing. The similarities were in abnormally long sway paths, preferential sway directions in the anterior-posterior plane, and sway reduction in the presence of stabilizing factors. The diffusion model afforded a biomechanical interpretation of sway path data with respect to the continual interplay between sway from the center of balance and attempts at sway correction. In general, alcoholic men and women exhibited greater diffusion coefficients in the short-term (open loop) component of sway than their sex-match controls, albeit not statistically significant for the women. Specifically, the model suggested that a strategy characterizing alcoholic men was to stand rigidly, causing inflexibility and difficulty in counter-movement to correct the resulting sway, but that use of stabilizing factors mitigated this tendency toward inflexibility. The strategy identified in alcoholic women suggested that they exert poorly regulated sway control for an extended period in the closed-loop sway component regardless of presence of stabilizing factors. Reduction in sway and closed-loop activity with stabilizing factors showed some differential expression in men compared with women with histories of alcohol dependence, but enduring deficits in postural instability in both sexes are indicative of a persisting liability for falling.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Daniel J. Pfefferbaum, B.A. for his invaluable help in setting up the experimental devices, data collection, and oversight of data integrity; Stephanie Sassoon, Ph.D., Anne O’Reilly, Ph.D., Anjali Deshmukh, M.D., and Margaret J. Rosenbloom, M.A. for diagnostic and questionnaire quantification of all subjects; and Elfar Adalsteinsson, Ph.D. for advice on the frequency analyses. Support for this work was provided by the United States National Institutes of Health grants AA010723, AA017168, and AA005965.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder (DSM-IV) American Psychiatric Association; Washington: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Baloh RW, Ying SH, Jacobson KM. A longitudinal study of gait and balance dysfunction in normal older people. Arch Neurol. 2003;60(6):835–839. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.6.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beatty WW, Hames KA, Blanco CR, Nixon SJ, Tivis LJ. Visuospatial perception, construction and memory in alcoholism. J Stud Alcohol. 1996;57:136–143. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins JJ, De Luca CJ. Open-loop and closed-loop control of posture: A random-walk analysis of center-of-pressure trajectories. Exp Brain Res. 1993;95:308–318. doi: 10.1007/BF00229788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins JJ, De Luca CJ. Upright, correlated random walks: A statistical-biomechanics approach to the human postural control system. Chaos. 1995;5(1):57–63. doi: 10.1063/1.166086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins JJ, De Luca CJ, Burrows A, Lipsitz LA. Age-related changes in open-loop and closed-loop postural control mechanisms. Exp Brain Res. 1995;104:480–492. doi: 10.1007/BF00231982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crovitz HF, Zener KA. Group test for assessing hand and eye dominance. Am J Psychol. 1962;75:271–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deuschl G, Bain P, Brin M. Consensus statement of the Movement Disorder Society on Tremor. Ad Hoc Scientific Committee. Mov Disord. 1998;13(Suppl 3):2–23. doi: 10.1002/mds.870131303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener H-C, Dichgans J, Bacher M, Guschlbauer B. Characteristic alteration of long-loop “reflexes” in patients with Friedreich’s disease and late atrophy of the cerebellar anterior lobe. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 1984a;47:679–685. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.47.7.679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener H-C, Dichgans J, Bacher M, Guschlbauer B. Improvement in ataxia in alcoholic cerebellar atrophy through alcohol abstinence. J Neurol. 1984b;231:258–262. doi: 10.1007/BF00313662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener HC, Dichgans J, Bacher M, Gompf B. Quantification of postural sway in normals and patients with cerebellar diseases. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1984c;57(2):134–42. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(84)90172-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener HC, Dichgans J, Guschlbauer B, Bacher M, Langenbach P. Disturbances of motor preparation in basal ganglia and cerebellar disorders. In: Allun JHH, Hulliger M, editors. Progress in Brain Research, Vol 80, Afferent Control of Posture and Locomotion. Vol. 80. Elsevier Scientific Publishers B.V.; Amsterdam: 1989. pp. 481–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durazzo TC, Gazdzinski S, Meyerhoff DJ. The neurobiological and neurocognitive consequences of chronic cigarette smoking in alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Alcohol. 2007;42(3):174–185. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fama R, Pfefferbaum A, Sullivan EV. Perceptual learning in detoxified alcoholic men: Contributions from explicit memory, executive function, and age. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2004;28:1657–1665. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000145690.48510.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fein G, Shimotsu R, Chu R, Barakos J. Paarietal gray matter volume loss is related to spatial processing deficits in long-term abstinent alcoholic men. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01019.x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellgiebel A, Siessmeier T, Winterer G, Luddens H, Mann K, Schmidt LG, Bartenstein P. Increased cerebellar PET glucose metabolism corresponds to ataxia in Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome. Alcohol Alcohol. 2004;39(2):150–3. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick LE, Jackson M, Crowe SF. The relationship between alcoholic cerebellar degeneration and cognitive and emotional functioning. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2008;32(3):466–485. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman S, Adams K, Koeppe RA, Berent S, Kluin KJ, Modell JG, Kroll P, Brunberg JA. Cerebellar and frontal hypometabolism in alcoholic cerebellar degeneration studied with Positron Emission Tomography. Ann Neurol. 1990;28(6):775–785. doi: 10.1002/ana.410280608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeka JJ, Schoner G, Dikjstra T, Ribeiro P, Lackner JR. Coupling of fingertip somatosensory information to head and body sway. Exp Brain Res. 1997;113(3):475–483. doi: 10.1007/pl00005600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauk M, Chow CC, Lipsitz LA, Mitchell SL, Collins JJ. Assessing muscle stiffness from quiet stance in Parkinson’s disease. Muscle Nerve. 1999;22(5):635–639. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(199905)22:5<635::aid-mus13>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledin T, Odkvist L. Abstinent chronic alcoholics investigated by dynamic posturography, ocular smooth pursuit and visual suppression. Acta Otolaryngology. 1991;111:646–655. doi: 10.3109/00016489109138395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattis S. Dementia Rating Scale (DRS) Professional Manual. Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.; Odessa, FL: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Mauritz KH, Dichgans J, Hufschmidt A. Quantitative analysis of stance in late cortical cerebellar atrophy of the anterior lobe and other forms of cerebellar ataxia. Brain. 1979;102(3):461–482. doi: 10.1093/brain/102.3.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller-Oehring EM, Schulte T, Fama R, Pfefferbaum A, Sullivan EV. Global-local interference is related to callosal compromise in alcoholism: A behavior-DTI association study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2009;33:477–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00858.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson HE. The National Adult Reading Test (NART) Nelson Publishing Company; Windsor, Canada: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Oscar-Berman M, Marinkovic K. Alcohol: effects on neurobehavioral functions and the brain. Neuropsychol Rev. 2007;17(3):239–57. doi: 10.1007/s11065-007-9038-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymakers JA, Samson MM, Verhaar HJ. The assessment of body sway and the choice of the stability parameter(s) Gait Posture. 2005;21(1):48–58. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbloom MJ, Pfefferbaum A, Sullivan EV. Recovery of short-term memory and psychomotor speed but not postural stability with long-term sobriety in alcoholic women. Neuropsychology. 2004;18(3):589–597. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.18.3.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbloom MJ, Rohlfing T, O’Reilly A, Sassoon SA, Pfefferbaum A, Sullivan EV. Improvement in memory and static balance with abstinence in alcoholic men and women: Selective relations with changes in regional ventricular volumes. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2007;155:91–102. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2006.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz E, Diener H, Dichgans J, Langohr H, Schied W, Schupmann A. Incidence of peripheral neuropathy and cerebellar ataxia in chronic alcoholics. J Neurol. 1986;233:212–217. doi: 10.1007/BF00314021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shubert TE, Schrodt LA, Mercer VS, Busby-Whitehead J, Giuliani CA. Are scores on balance screening tests associated with mobility in older adults? J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2006;29(1):35–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan EV, Deshmukh A, Desmond JE, Lim KO, Pfefferbaum A. Cerebellar volume decline in normal aging, alcoholism, and Korsakoff’s syndrome: Relation to ataxia. Neuropsychology. 2000a;14(3):341–352. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.14.3.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan EV, Desmond JE, Lim KO, Pfefferbaum A. Speed and efficiency but not accuracy or timing deficits of limb movements in alcoholic men and women. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2002a;26:705–713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan EV, Fama R, Rosenbloom MJ, Pfefferbaum A. A profile of neuropsychological deficits in alcoholic women. Neuropsychology. 2002b;16(1):74–83. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.16.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan EV, Rose J, Pfefferbaum A. Effect of vision, touch, and stance on cerebellar vermian-related sway and tremor: A quantitative MRI and physiological study. Cereb Cortex. 2006;16:1077–1086. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan EV, Rose J, Pfefferbaum A. Physiological and focal cerebellar substrates of abnormal postural sway and tremor in alcoholic women. Biological Psychiatry. 2009a doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.08.008. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan EV, Rose J, Pfefferbaum A. Postural sway and tremor reduction with stabilizing factors despite a cerebellar systems substrate (abs). Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society for Neuroscience; Chicago, IL. 2009b. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan EV, Rose J, Rohlfing T, Pfefferbaum A. Postural sway reduction in aging men and women: Relation to brain structure, cognitive status, and stabilizing factors. Neurobiol Aging. 2009c;30:793–807. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan EV, Rosenbloom MJ, Pfefferbaum A. Pattern of motor and cognitive deficits in detoxified alcoholic men. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000b;24(5):611–621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinetti M, Doucette J, Claus E. The contribution of predisposing and situational risk factors to serious fall injuries. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 1995a;43:1207–1213. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb07395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinetti M, Doucette J, Claus E, Marottoli R. Risk factors for serious injury during falls by older persons in the community. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 1995b;43:1214–1221. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb07396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victor M, Adams RD, Collins GH. The Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome and Related Neurologic Disorders Due to Alcoholism and Malnutrition. 2. F.A. Davis Co; Philadelphia: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale - Revised. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. The Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence. The Psychological Corporation; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wober C, Wober-Bingol C, Karwautz A, Nimmerrichte RA, Deecke L, Lesch OM. Postural control and lifetime alcohol consumption in alcohol-dependent patients. Acta Neurol Scand. 1999;99(1):48–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1999.tb00657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wober C, Wober-Bingol C, Karwautz A, Nimmerrichter A, Walter H, Deecke L. Ataxia of stance in different types of alcohol dependence--a posturographic study. Alcohol Alcohol. 1998;33(4):393–402. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.alcalc.a008409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]