Abstract

Aims

The purpose of these analyses was to examine the persistence and predictors of elevated depressive symptoms in 884 women over their children's preschool years.

Results

Depressive symptoms in women with young children are surprisingly consistent throughout their children's preschool years. Of the 82.6% of women without elevated depressive symptoms at the initial assessment (study child was 11–42 months of age), 82.4% remained without symptoms over two follow-up assessments. Of 17.4% of women with elevated symptoms at baseline, 35.6% had elevated symptoms at one of the two follow-ups, and 27.4% had elevated symptoms at both follow-ups. Persistently elevated depressive symptoms were related to low education, high levels of anxiety, high parenting distress, and low levels of emotional support at baseline.

Conclusions

Women who report symptoms of depression when their children are young are highly likely to continue to report such symptoms. These results support the need to screen for elevated depressive symptoms at varying intervals depending on prior screening results and for screening in locations where women most at risk routinely visit, such as well-child clinics. Further, these results point to the need for a system to identify and manage this common treatable condition because these elevated symptoms continue throughout their children's preschool years for a substantial portion of women.

Introduction

Depression is a prevalent condition and one that is more common in young adults, females, those with less education, and those with more psychosocial stressors.1–8 The increased prevalence in young adult women is particularly troublesome because it has the potential to impact not only the young women but also their children.9–14 Although estimates of depression in women with children are high (10%–42%), data indicate that few of these women are identified or treated.15–17 This is troublesome both because depression is a debilitating condition and because we have effective psychosocial and pharmacological treatments.16

The majority of information on depression in women with young children (maternal depression) comes from postpartum studies,18 although there are data to suggest that mothers may develop depression or suffer from elevated depressive symptoms throughout the early years of childhood and that severity and chronicity of depressive symptoms are related to more severe problems in children.19–21 Thus, information on the timing, severity, and chronicity of depressive symptoms in women with young children is important if we are to understand through what mechanisms depression in mothers affects children.10 Examining these features requires longitudinal studies, and these are, as pointed out by Hammen and Brennan,22 not common. A study by McLennan et al.18 suggests that just over a third of women (35.7%) have persistently elevated symptoms over an 18-month period. Similarly, a study by Horwitz et al.23 documented that 46.3% of the 16.9% of women with elevated symptoms on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Inventory (CES-D) whose children were between 1 and 2 years of age still had elevated symptoms at a 12-month follow-up assessment. Further, 12.8% of mothers had newly developed elevated depressive symptoms at the time of follow-up.

Both of these studies identified a number of important predictors of persistent depressive symptoms, including poor self-rated health, low educational attainment, anxiety symptoms, and family conflict. Both studies, however, were limited by examination of two time points, and neither examined the patterns and persistence of depressive symptoms throughout the preschool years of childhood. Likewise, chronicity of maternal depressive symptoms over the first 36 months of a child's life was examined in the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Study of Early Childcare. If women were positive for depressed symptoms in four or five of the five interviews, they were classified as chronically depressed (7.6%). Chronically depressed women had less education and lower income/needs ratio, were less likely to have a partner in the household at the 1-month assessment, and reported low social support.24 A study by Pascoe et al.25 examined predictors of maternal depression over 5 years using data collected in 1987–1988 and then in 1992–1994. In this national probability sample that included 2235 women with children < age 19, they found that young maternal age, African American race, low education, being unmarried, and being indigent were related to persistence of depression. However, no psychosocial variables were evaluated.25 Twenty percent of the sample was positive at baseline and at the 5-year follow-up study. One set of studies did examine maternal depression over a 14-year period. The Mater-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy, a longitudinal study of 8556 women and their children born at one of two obstetric hospitals in Brisbane, Australia, from 1981 to 1984, evaluated women at five points over the 14-year period, including three times during the period between the child's birth and age 5. Women who were depressed at both the 6-month and 5-year assessments were more likely to have 14-year-olds reporting high levels of depression and anxiety. Predictors of persistently elevated symptoms within the women were not examined in a multivariate model.26

Information on the prevalence of depressive symptoms over the years prior to school enrollment or on the predictors, particularly psychosocial characteristics, of long-term elevated symptoms of depression is relatively scarce. Given that prior work has established that both severity and chronicity of maternal depressive symptoms are important predictors of poor child outcomes, examining the prevalence of elevated maternal depressive symptoms and the relationship of variables suggested by prior longitudinal studies to elevated symptoms throughout the child's preschool years is important. In this analysis, we extend the findings of Horwitz et al.,23 as data are now available on the mothers at a third time point, when the children were in kindergarten.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

An age stratified and sex-stratified random sample of children (n = 8404) who were born at Yale-New Haven Hospital between July 1995 and September 1997 and lived in the 15 towns/cities that composed the New Haven Meriden Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area from the 1990 Census was selected from birth records provided by the State of Connecticut Department of Public Health (for details about sampling, see reference 27). The sampling plan was designed to refine a new measure of social and emotional adjustment in a developmentally healthy sample of children.28 For this reason, children were excluded from the sample if they were born prematurely (<36 weeks), of low birth weight (<2200 g), likely to have developmental delays due to birth complications (e.g., severe anoxia, need for resuscitation, or 1 minute and 5-minute Apgar scores <5), or had chromosomal anomalies, such as Down syndrome. Children who were deceased before sampling (n = 14) or adopted (n = 4) were excluded. In addition, one child per mother was randomly selected.

A sample of 1788 families was selected randomly from the 7433 eligible subjects that remained after applying the exclusion criteria. These families did not differ significantly from original subjects (n = 8404) in terms of maternal education or child race. Not surprisingly, given the exclusion criteria, the samples differed slightly in terms of infant birth weight and gestational age (p < 0.01), as well as maternal age (mean ± SD: 29.6 ± 6.1 vs. 28.8 ± 6.2, t = 5.02, p < 0.01). Among those sampled, subjects were excluded when (1) neither parent spoke English well enough to participate in a self-report or interview format (n = 50), (2) parents had lost custody (n = 17), (3) families had moved out of state (n = 116), (4) the biological mother was too ill to participate (n = 2), or (5) the family could not be located to determine eligibility (n = 112). Compared with the ineligible sample (n = 297), the final eligible sample of 1491 was significantly higher in birthweight, paternal and maternal age, maternal education, and years at the birth address and was less likely to be of minority ethnicity (p < 0.01); however, these differences were all of small effect size (Cohen's D ranged from 0.18 to 0.41). There were no significant differences in gestational age, paternal education, or child sex.

Of the eligible subjects, 1278 (85.7%) participated in the initial data collection. Participants had slightly higher maternal education than eligible nonparticipants (14.1 ± 2.4 vs. 13.6 ± 2.4 years, Cohen's D 0.21) and were also more likely to be of Caucasian ethnicity (75.3% vs. 68.3%); there were no significant differences on any other sociodemographic or birth status variables. The sample was sociodemographically similar to families living in the area. Only biological mothers (n = 1208, 94.5%) are included in this report.

Longitudinal sample. Of the 1208 biological mothers who participated in the initial assessment, 1095 participated at the 1-year follow-up (90.6%) and 928 participated when their child was in kindergarten. Mothers who did not complete the CES-D at the initial assessment (n = 13), at the first follow-up (n = 14), at the kindergarten follow-up (n = 14), or at all three assessments (n = 2) were excluded, as was 1 mother with missing sample weight data. The 28 mothers who completed the CES-D at the initial assessment but had missing CES-D scores at one or both follow-up assessments tended to have higher CES-D scores at the initial assessment compared with mothers who completed the CES-D at all three assessments (11.4 ± 7.2 vs. 9.0 ± 7.8, p = 0.07). Thus, the analytical sample for these analyses includes the 884 biological mothers who participated in the initial assessment and the 1-year follow-up and kindergarten follow-up data collections with known CES-D scores and sample weight data. Comparisons of the biological mothers included (n = 884) and excluded (n = 324) from the analyses (due to nonparticipation or missing data) showed that the former were significantly older (32.7 ± 5.9 vs. 30.7 ± 6.3, p < 0.0001), less likely to be single (16.7% vs. 25.4%, p < 0.001), more likely to have one or more parent working (93.4% vs. 87.0%, p < 0.01), more likely to be educated beyond high school (78.4% vs. 60.5%, p < 0.0001) and report better physical health (p < 0.01, phi = −0.09), and less likely to report living in poverty (15.3% vs. 26.7%, p < 0.0001) and report having difficulty paying their bills (21.3% vs. 38.4%, p < 0.0001). The two groups did not differ significantly on child age, gender, or health status.

Procedures. From June to September 1998, approximately 1 year later, and then 2–4 years after the first follow-up, parents were invited to participate in the study through a mailing that included a questionnaire and children's book. Staff members subsequently telephoned parents to address questions and concerns and encourage participation. Parents who did not participate after 1 month received a second mailing followed by in-person contacts to offer assistance needed to facilitate participation (e.g., interviews, babysitting). The first follow up assessment occurred approximately 1 year after the initial visit (12.1 ± 1.7, interquartile range [IQR] 11.8–12.5 months), and the kindergarten follow-up assessment occurred approximately 3 years later (35.8 ± 7.9, IQR 30.9–42.3 months). Because children ranged in age from 12 months to 42 months in year 1 and because multiple attempts were necessary to insure an adequate response rate, time between the initial assessment and the kindergarten follow-up ranged from 28.7 to 72.8 months (47.9 ± 7.8, IQR 43.1–54.4). Time between the initial visit and the first follow up visit was weakly associated with CES-D score at the initial visit (r = 0.07, p = 0.03) as well as change in CES-D score from the initial visit to the first follow-up visit (r = −0.09, p = 0.006). All procedures and the informed consent process employed were approved by two university human subjects committees. Parents received $25 for participating at the first two time points and $30 for the kindergarten time point.

Measures

Birth record information

Birth status variables were obtained from birth records provided by the State of Connecticut Department of Public Health. Birth status variables included infant birth weight, gestational age, 1 minute and 5-minute Apgar scores, parental age, maternal education, maternal race, and years at the birth address. Additional variables reflecting birth status were used as exclusion criteria in sample selection.

Sociodemographic variables

Mothers answered several questions about their family sociodemographic status, including the target child's sex, age, ethnicity, and birth order; maternal age; parental education; marital status; and before-tax household income.

Financial strain

Mothers reported difficulty paying bills on a 5-point scale ranging from “easy” to “difficult.” The data were recoded whereby the lowest three values were considered “not difficult,” whereas the top two values were classified as “difficult.”

Physical health

Mothers rated their child's current physical health on a 5-point scale from “poor” health to “excellent” health. Mothers also rated their own current physical health on a 5-point scale from “poor” health to “excellent” health. As there were only 2 mothers who reported poor health for themselves and no mothers who reported their child as having poor health at the initial assessment, the bottom two categories (poor and fair) were combined in all analyses.

Maternal anxiety symptoms

Mothers completed the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI),29 a self-report measure that consists of descriptive statements about common symptoms of anxiety. A mother indicates how much she has been bothered by each symptom on a 4-point scale from “not at all” to “severely bothered.” Women with scores of ≥ 16 were classified as having elevated anxiety symptoms. The BAI measure has adequate psychometric properties.

Family functioning

Mothers rated expressiveness and conflict in the family using the Expressiveness and Conflict scales from the Family Environment Scale (FES). These scales have demonstrated adequate reliability and validity and have been shown to discriminate between distressed and nondistressed families.30 Scores were dichotomized based on the worst quintile, with Conflict scores of ≥ 4 and Expressiveness scores of ≤ 4 categorized as lower family functioning.

Life events

Mothers completed an adaptation of the Life Events Inventory (LEI).31 For this study, 40 items with the highest severity weights and greatest applicability to parents of young children were selected from the 55-item LEI. The LEI measure was derived in part from the Schedule of Recent Life Experiences.32 Mothers who reported at least 7 life events were categorized as having a high number of life events (approximately 20% of the sample).

Mothers also reported life events for their children. Women rated 14 events likely to be upsetting for children, such as an automobile accident, a serious injury, birth of a sibling. Mothers who reported at least 3 child life events or at least 5 parent life events were categorized as high on the child or parent scales, respectively.

Social support

Social support was measured using the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) parent questionnaire concerning social support.33 More specifically, two scales of this self-report measure, Tangible Support and Emotional Support, were used. The scales are composed of 12 items and have demonstrated adequate psychometric properties, including modest 1-year stability. Women who scored in the lowest quintile were categorized as low support.

Parenting stress

Parenting stress was measured with the Parent Distress and Parent-Child Dysfunctional Interaction subscales of the Parenting Stress Index Short Form (PSI/SF).34 The Parent Distress subscale measures distress in the parenting role (e.g., I feel trapped by my responsibilities as a parent), whereas the Parent-Child Dysfunctional Interaction subscale measures the parent's perception of her relationship with her child as reinforcing (e.g., my child makes more demands on me than most children). The PSI/SF has shown high internal consistency and good test-retest reliability. Using established cutoff points, scores of at least 36 on the Parent Distress scale were considered to be high, as were scores of at least 27 on the Parent-Child Dysfunctional scale.

Outcome variable

Maternal depressive symptoms

Maternal depressive symptoms were measured using the CES-D, a 20-item self-report scale that assesses depressive symptoms in adults. The CES-D total score was calculated if at least 18 of the 20 items were completed. Person-mean substitution was used to replace missing values for respondents missing 1 or 2 items on the instrument (initial assessment: n = 77, 1-year follow-up: n = 69, kindergarten follow-up: n = 58). Participants with CES-D scores of ≥ 16 were classified as having elevated depressive symptoms, whereas mothers with scores <16 were classified as not having elevated depressive symptoms.35 The CES-D has high internal consistency (coefficient α: 0.84–0.90) and modest test-retest reliability for 2–4-week intervals (r =0.51–0.67).35 Based on the pattern of results across the three assessments, a three-level outcome variable was created: 1) women without elevated depressive symptoms at all three assessments (never), (2) women with elevated depressive symptoms at one or two assessments (intermittent), (3) women with elevated depressive symptoms at all three assessments (always).

Statistical analysis

To adjust for potential biases due to unequal probabilities of selection, differential nonresponse in the initial study, and differential attrition, all analyses were weighted. Univariate descriptive statistics, including weighted means and standard deviations (SDs) for continuous measures and unweighted counts and weighted percentages for categorical measures, were examined. Weighted bivariate analyses were used to assess differences in sociodemographic, maternal support and stress, and child characteristics from the initial assessment for mothers who always, intermittently, or never reported elevated depressive symptoms. Unadjusted between-group differences were assessed via the Rao-Scott chi-square test from weighted contingency table analyses, the Wald chi-square test from weighted logistic regression analyses, and the F-test from weighted linear regression analyses. If the overall p value was statistically significant (p < 0.05), post hoc pairwise comparisons were examined.

Univariate analyses showed that there were very few missing data for the 24 covariates from the initial assessment. Nine variables (37.5%) from the initial assessment had no missing data; the remaining variables had <2% missing data, with the exception of financial hardship, which had missing values for 6.9% of the sample. Whereas 11% of women who never reported elevated depressive symptoms had missing covariate data from the initial assessment, 34% of women who always reported elevated depressive symptoms had missing covariate data from the initial assessment, suggesting that the mechanism for missing covariate data was not random. In this situation, complete case analysis would likely result in invalid inferences.36 Consequently, weighted linear and logistic regression imputation was used to impute missing values for covariates from the initial assessment prior to fitting multivariable models.

Multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to further assess the association between maternal and child characteristics measured at the initial assessment and the three-level outcome: always, intermittent, or never elevated depressive symptoms. Variables were grouped into three conceptual domains: maternal sociodemographic characteristics, maternal support and stress measures, and child characteristics. To ensure that potentially relevant variables were examined in further analyses, variables with a bivariate association of p < 0.25 were assessed in multivariable regression models using the forward selection method. Preliminary weighted ordinal logistic regression models showed that the effect of each variable was not consistent across the response categories and that the proportional odds assumption was violated. Thus, weighted multinomial logistic regression was used in subsequent analyses. Given our interest in identifying risk factors associated with persistently elevated depressive symptoms, covariates significantly associated at p < 0.05 for the always vs. never and always vs. intermittent comparisons were retained, as were variables that appreciably confounded those associations. The results are summarized via adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI), and the overall p values for each covariate are provided. The data were analyzed using procedures appropriate for survey data in SAS version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

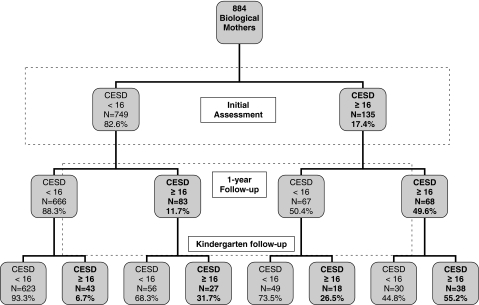

Figure 1 shows the distribution of elevated depressive symptoms on the CES-D over the three assessments: initial assessment, the 1-year follow-up, and the kindergarten follow-up. As previously reported,23 approximately 17% of these mothers reported elevated symptoms of depression at the initial assessment, and approximately 18% reported elevated symptoms at the first follow-up study. Among the 82.6% (n = 749) of women without elevated depressive symptoms at the initial visit, 82.4% (n = 623) remained without symptoms over both follow-ups, 13.9% (n = 99) reported elevated depressive symptoms at only one follow-up, and only 3.7% (n = 27) reported elevated symptoms of depression at both follow-up periods. Rates of subsequent elevated symptoms were quite different for those women who reported elevated symptoms at the initial visit. For the 17.4% (n = 135) of women with elevated CES-D scores at the initial assessment, 37.0% (n = 49) did not have elevated symptoms at either follow-up, 35.6% (n = 48) had elevated symptoms at one of the two follow-up assessments, and 27.4% (n = 38) had elevated symptoms at both follow-up assessments. Overall, 68.0% (n = 623) of mothers never reported elevated depressive symptoms, 27.2% (n = 223) of mothers had intermittent depressive symptoms (n = 148 at one assessment and n = 75 at two assessments), and 4.8% (n = 38) of mothers had elevated depressive symptoms at each of the three assessment points. Compared with women without elevated depressive symptoms at the initial survey, women with elevated depressive symptoms at the initial survey had 5.7-fold increased odds of elevated depressive symptoms at one of the follow-up assessments and 16.5-fold increased odds of elevated depressive symptoms at both follow-up assessments.

FIG. 1.

Elevated depressive symptoms on the CES-D over the three assessments.

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic and physical/mental health characteristics of women who always reported elevated symptoms, intermittently reported elevated symptoms, and never reported elevated symptoms. The first group significantly differed from the latter two groups on most of the sociodemographic and health characteristics at the initial assessment. Women who always reported elevated depressive symptoms had significantly lower educational attainment, were more likely to be living in poverty and have difficultly paying bills, rated their health lower, and had more anxiety symptoms compared with the other two groups. Additionally, compared with women who never reported elevated depressive symptoms, women who reported elevated depressive symptoms at all three assessments were significantly younger, more likely to be of minority ethnicity, and more likely to be unemployed.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Health Characteristics of Biological Mothers at Initial Assessment According to Never, Intermittent, and Always Elevated Depressive Symptomsa

| Maternal sociodemographic characteristics at initial assessment | Always elevated (n = 38) | Intermittent (n = 223) | Never elevated (n = 623) | Overall p value | Always vs. intermittent | Always vs. never | Intermittent vs. never |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age | 29.6 ± 7.9 | 30.8 ± 6.7 | 32.6 ± 5.8 | 0.0016 | 0.4313 | 0.0358 | 0.0019 |

| Age <18 when child was born | 2 (6.0%) | 9 (5.6%) | 21 (4.5%) | 0.8361 | – | – | – |

| Number of children in home | 2.14 ± 1.04 | 2.09 ± 1.08 | 2.07 ± 0.94 | 0.9184 | – | – | – |

| Education | |||||||

| < High school | 12 (36.6%) | 20 (13.1%) | 26 (6.6%) | <0.0001 | 0.0021 | <0.0001 | 0.0081 |

| High school /GED | 5 (13.7%) | 41 (20.2%) | 87 (15.5%) | ||||

| More than high school | 15 (38.0%) | 75 (33.4%) | 198 (32.0%) | ||||

| College degree | 6 (11.7%) | 87 (33.3%) | 312 (45.9%) | ||||

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| African American | 13 (44.2%) | 45 (31.3%) | 67 (15.0%) | <0.0001 | 0.1528 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Caucasian | 18 (37.1%) | 149 (55.5%) | 497 (74.4%) | ||||

| Other | 7 (18.7%) | 29 (13.2%) | 59 (10.7%) | ||||

| Employment status | |||||||

| Unemployed | 7 (22.7%) | 19 (12.8%) | 17 (3.6%) | <0.0001 | 0.3425 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Working/student (PT or FT) | 24 (60.6%) | 154 (67.0%) | 423 (67.3%) | ||||

| Homemaker | 7 (16.7%) | 50 (20.2%) | 182 (29.1%) | ||||

| Poverty status | |||||||

| Poverty | 20 (64.2%) | 45 (26.9%) | 68 (14.0%) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Borderline (100%–185%) | 6 (16.6%) | 36 (20.0%) | 72 (13.5%) | ||||

| Not in poverty | 10 (19.2%) | 140 (53.1%) | 478 (72.5%) | ||||

| Hard to pay bills | |||||||

| Hard | 18 (53.3%) | 61 (28.0%) | 97 (17.2%) | <0.0001 | 0.0018 | <0.0001 | 0.0049 |

| Not hard | 13 (29.5%) | 145 (62.7%) | 492 (76.5%) | ||||

| No answer | 7 (17.2%) | 17 (9.3%) | 34 (6.3%) | ||||

| Maternal mental physical health | |||||||

| Physical health | |||||||

| Poor or fair | 8 (19.2%) | 16 (8.2%) | 13 (2.1%) | <0.0001 | 0.0042 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Good | 19 (49.7%) | 56 (26.0%) | 90 (13.9%) | ||||

| Very good | 8 (22.1%) | 86 (38.7%) | 248 (41,1%) | ||||

| Excellent | 3 (9.0%) | 63 (27.1%) | 271 (42.9%) | ||||

| High anxiety: Beck | 11 (29.4%) | 13 (5.9%) | 11 (1.7%) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0016 |

| Anxiety Inventory ≥ 16 |

Unweighted counts and weighted column percentages shown.

A similar pattern of results was observed for psychosocial characteristics (Table 2), Women who always reported elevated depressive symptoms were significantly different from those who intermittently or never reported elevated symptoms on most of these characteristics. Specifically, a significantly higher proportion of women with elevated symptoms at all three assessments reported high family conflict, low emotional and tangible support, and high levels of parenting stress compared with the other two groups. Women who always reported elevated depressive symptoms had the highest prevalence of low family functioning, low social support, high parenting stress, and stressful life events, and women in the never elevated depressive symptoms group had the lowest prevalence of those characteristics.

Table 2.

Maternal Support and Stress Characteristics of Biological Mothers at Initial Assessment According to Never, Intermittent, and Always Elevated Depressive Symptomsa

| Maternal support and stress characteristics at initial assessment | Always elevated (n = 38) | Intermittent (n = 223) | Never elevated (n = 623) | Overall p value | Always vs. intermittent | Always vs. never | Intermittent vs. never |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family functioning | |||||||

| High conflict: Worst quintile (≥ 4) | 20 (58.2%) | 62 (28.7%) | 108 (16.5%) | <0.0001 | 0.0010 | <0.0001 | 0.0005 |

| Low expressiveness: Worst quintile (≤ 4) | 14 (38.8%) | 61 (30.9%) | 82 (14.4%) | <0.0001 | 0.3829 | 0.0003 | <0.0001 |

| Social support | |||||||

| No friends | 4 (14.6%) | 14 (9.2%) | 12 (2.2%) | 0.0004 | 0.4612 | 0.0008 | 0.0002 |

| Low emotional support: Worst quintile (≤ 3.86) | 22 (60.2%) | 69 (33.6%) | 73 (12.1%) | <0.0001 | 0.0043 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Low tangible support: Worst quintile (≤ 3.25) | 17 (50.5%) | 62 (28.5%) | 94 (15.2%) | <0.0001 | 0.0146 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Parenting stress | |||||||

| High parent-child dysfunction: PSI ≥ 27 | 10 (27.0%) | 11 (6.7%) | 14 (3.3%) | <0.0001 | 0.0012 | <0.0001 | 0.1210 |

| High parent distress: PSI (≥ 36) | 19 (51.3%) | 23 (11.3%) | 11 (2.6%) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0003 |

| Stressful life events | |||||||

| High parent life events: Worst quintile (≥ 5) | 14 (42.4%) | 60 (28.1%) | 95 (15.4%) | <0.0001 | 0.1111 | 0.0001 | 0.0003 |

Unweighted counts and weighted column percentages shown.

On the other hand, child characteristics, including age at the initial visit, gender, and birth order, did not significantly differ across the three groups (Table 3). All three groups, however, differed significantly with respect to their child's health and adverse child life events; women who always reported elevated depressive symptoms gave lower ratings of their child's health and more often reported high adverse child life events compared with the other two groups.

Table 3.

Sociodemographic and Health Characteristics of Study Children at Initial Assessment According to Never, Intermittent, and Always Elevated Depressive Symptomsa

| Child characteristics at initial assessment | Always elevated (n = 38) | Intermittent (n = 223) | Never elevated (n = 623) | Overall p value | Always vs. intermittent | Always vs. never | Intermittent vs. never | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (months) | 22.8 ± 7.5 | 23.6 ± 8.5 | 24.5 ± 7.5 | 0.3157 | – | – | – | |

| Age (categorical) | ||||||||

| <18 months | 9 (29.9%) | 68 (34.7%) | 142 (26.6%) | 0.1162 | ||||

| 18–24 months | 12 (31.5%) | 41 (17.0%) | 144 (20.4%) | – | – | – | ||

| >24 months | 17 (38.6%) | 114 (48.3%) | 337 (53.0%) | |||||

| Male sex | 19 (57.6%) | 112 (51.0%) | 293 (49.8%) | 0.6793 | – | – | – | |

| Birth Order | ||||||||

| Only child | 14 (33.9%) | 80 (33.3%) | 191 (32.0%) | 0.8959 | ||||

| Oldest child | 0 (0.0%) | 16 (7.2%) | 49 (8.0%) | |||||

| Middle child | 4 (10.1%) | 11 (6.5%) | 33 (5.4%) | – | – | – | ||

| Youngest child | 20 (56.0%) | 116 (53.0%) | 350 (54.6%) | |||||

| Health status | ||||||||

| Fair or poor | 1 (2.0%) | 3 (1.2%) | 2 (0.5%) | <0.0001 | 0.0018 | <0.0001 | 0.1003 | |

| Good | 9 (27.2%) | 13 (7.0%) | 25 (3.6%) | |||||

| Very good | 5 (10.0%) | 45 (19.2%) | 87 (15.5%) | |||||

| Excellent | 23 (60.8%) | 161 (72.6%) | 507 (80.4%) | |||||

| Stressful life events | ||||||||

| High child life events: Worst quintile (≥ 3) | 14 (36.4%) | 42 (17.7%) | 69 (10.9%) | <0.0001 | 0.0169 | <0.0001 | 0.0166 |

Unweighted counts and weighted column percentages shown.

Table 4 displays the results of the multinomial logistic regression analyses. Maternal education, anxiety, parent distress, and emotional support were significantly different for all three groups. Women who were poorly educated, reported high levels of anxiety, high parent distress and low levels of emotional social support and were at significantly increased odds of reporting elevated depressive symptoms at all three assessments compared with those who reported elevated depressive symptoms at one or two assessments or who never reported elevated symptoms. As expected, these effects were stronger for the always vs. never groups compared with the always vs. intermittently elevated depressive symptoms groups. For example, women who reported high levels of anxiety at the initial assessment had 18.42–fold (95% CI 5.39, 62.91) increased odds of always vs. never reporting elevated depressive symptoms, compared with 6.42-fold (95% CI 2.11, 19.49) increased odds of always vs. intermittently reporting elevated depressive symptoms. Similarly, women with lower levels of education and emotional support and high levels of anxiety and parenting stress were at significantly increased odds of reporting intermittent depressive symptoms compared with women who never reported elevated symptoms, with ORs ranging from 2.1 for maternal education to 3.1 for emotional social support. Maternal health, which was statistically significant for comparisons with the never elevated depressive group but not for the always vs. intermittently elevated depressive group, was included in the model because it confounded the associations between the other four covariates and the outcome. Variables measuring time between visits were not included in the final model, as they were not statistically significant nor did they confound the association between the psychosocial measures and the outcome.

Table 4.

Maternal Characteristics at Initial Assessment Associated with Increased Odds of Elevated Depressive Symptoms at All Three Assessments

| Correlates from initial assessment | Overall p value | Always vs. never OR (95% CI) | Always vs. intermittent OR (95% CI) | Intermittent vs. never OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal education | ||||

| < High school vs. ≥ high school | 0.0026 | 7.40 (2.35, 23.33) | 3.56 (1.24, 10.21) | 2.08 (1.00, 4.32) |

| Beck Anxiety Inventory | ||||

| ≥ 16 vs. <16 | <0.0001 | 18.42 (5.39, 62.91) | 6.42 (2.11, 19.49) | 2.87 (1.10, 7.52) |

| Parenting stress | ||||

| Parent distress ≥ 36 vs. <36 | 0.0003 | 12.79 (3.68, 44.41) | 4.37 (1.65, 11.60) | 2.93 (1.14, 7.53) |

| Emotional social support | ||||

| Worst quintile vs. other quintiles | <0.0001 | 8.97 (3.38, 23.80) | 2.89 (1.14, 7.31) | 3.11 (1.98, 4.87) |

| Maternal health (per 1-unit increase) | 0.0001 | 2.13 (1.31, 3.47) | 1.41 (0.87, 2.27) | 1.51 (1.21, 1.88) |

Discussion

This longitudinal follow-up of a birth cohort provides rarely available data on maternal depressive symptoms over a 4-year period during early childhood. These data show that most (82.4%) women who report no or low depressive symptoms when their children are young (11–42 months of age) remain without clinically significant depressive symptoms during their children's preschool years. For women who report clinically elevated depressive symptoms, however, most (63.0%) continued to report clinically significant depressive symptoms at subsequent assessments, and 27.4% consistently reported elevated depressive symptoms in all three assessments, suggesting the presence of chronically elevated depressive symptoms. This observation is consistent with earlier work18,23,37,38 and suggests that once a woman endorses clinically significant symptoms of depression, she is likely to continue experiencing those symptoms. Exposure to chronic maternal depressive symptoms in early childhood is of concern, given the potentially negative effects of depression on children.9–14,19,21 This finding argues for identification and treatment of depressive symptoms because these symptoms typically do not resolve without intervention and there are data to suggest that treating maternal depression has benefits for mothers and their children.39

Examining features related to persistent and intermittent depressive symptoms shows a consistent pattern of predictors. Women who are poorly educated, report elevated anxiety symptoms, have high levels of parent distress, have limited emotional support, and are in poorer health are likely to consistently or intermittently report depressive symptoms. These predictors have been reported previously and are well recognized1–8,23,39–42 and suggest that when they co-occur with elevated depressive symptoms, women should be targeted for screening and subsequent intervention, if appropriate. In particular, when there are elevations in both reported anxiety and depressive symptoms, women should be targeted for screening and treatment if necessary, as their symptoms are highly likely to persist over a considerable length of time. It is important to tailor depression interventions to address contextual factors, such as parental distress and absence of emotional support, as these correlates are likely to persist over time and increase the risk of persistence and recurrence of elevated depressive and anxious symptoms.

Limitations

These data, like all data, have limitations. They come from a healthy birth cohort, which excluded children who were identified as having risk factors for developmental delays at the time of their birth, including prematurity, low birthweight, genetic disorders, and serious birth complications, located in one Northeastern region comprising urban and suburban towns. Therefore, our estimates of depression are likely lower than those that would result from a nationally representative sample. The biological mothers reported all information, and objective measures from other sources were not obtained. Hence, we do not know if the elevated depressive symptoms influenced the reporting of the correlates. Symptoms of depression were gathered from women at three points in time. We have no way of knowing if women had elevated symptoms some or all of the time in the intervals between assessments. Although we know how many women had symptoms that remitted, we do not know the percentage of those whose symptoms remitted who received treatment. It is also unclear if women with incident depressive symptoms were suffering from postpartum depression from bearing additional children. Finally, we examined elevated symptoms of depression and did not establish clinical diagnoses of depression.

Conclusions

What is clear from these findings is the consistency in reports of depressive symptoms. Those women who did not initially report elevated symptoms when their children were 1–2 years of age were less likely to develop them throughout the early childhood years. Conversely, women who reported symptoms of depression were highly likely to continue to report such symptoms. These results raise a number of interesting questions about identification, treatment and the effectiveness of the treatment that is delivered in usual care settings. Given that there are known efficacious treatments for depression, we suspect that the continued reporting of elevated symptoms is likely due to lack of identification and subsequent use of efficacious treatments, although further research will be needed to fully understand what is driving these results. That the pattern of elevated symptoms varies based on prior symptom scores argues for smart screening; that is, screening for depression at varying intervals depending on prior screening results43 and for screening in locations where women who are most at risk based on these data are seen routinely, such as well-child clinics. The results also argue for a systematic approach to identifying and managing women with young children who experience symptoms of depression, as just over 27% of women who reported considerable symptoms of depression when their children were infants or toddlers still reported those symptoms when their children were in kindergarten. Given the sequelae of depression for both women and their children, strategies for early identification and treatment should be a priority of our medical care system.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIMH grant R01 MH055278.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Blazer DG. Kessler RC. McGonagle KA. Swartz MS. The prevalence and distribution of major depression in a national community sample: The National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:979–986. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.7.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC. McGonagle KA. Swartz M. Blazer DG. Nelson CB. Sex and depression in the National Comorbidity Survey. I: Lifetime prevalence, chronicity and recurrence. J Affect Disord. 1993;29:85–96. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(93)90026-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health. Depression: What every woman should know. www.nimh.nih.gov/publicat/depwomenknows.cfm. [Jun 15;2006 ]. www.nimh.nih.gov/publicat/depwomenknows.cfm

- 4.Kessler RC. McGonagle KA. Zhao S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kessler RC. McGonagle KA. Nelson CB. Hughes M. Swartz M. Blazer DG. Sex and depression in the National Comorbidity Survey. II: Cohort effects. J Affect Disord. 1994;30:15–26. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(94)90147-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bebbington P. Dunn G. Jenkins R, et al. The influence of age and sex on the prevalence of depressive conditions: Report from the National Survey of Psychiatric Morbidity. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2003;15:74–83. doi: 10.1080/0954026021000045976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldberg D. The aetiology of depression. Psychol Med. 2006;36:1341–1347. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blehar MC. Oren DA. Gender differences in depression. www.medscape.com/viewarticle/408844. Medscape General Medicine. 1999;1(2):1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lovejoy MC. Graczyk PA. O'Hare E. Neuman G. Maternal depression and parenting behavior: A meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2000;20:561–592. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodman SH. Gotlib IH. Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: A developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychol Rev. 1999;106:458–490. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.106.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guttmann A. Dick P. To T. Infant hospitalization and maternal depression, poverty and single parenthood—A population-based study. Child Care Health Dev. 2004;30:67–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2004.00390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carter AS. Garrity-Rokous FE. Chazan-Cohen R. Little C. Briggs-Gowan MJ. Maternal depression and comorbidity: Predicting early parenting, attachment security, and toddler social-emotional problems and competencies. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:18–26. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200101000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teti DM. Gelfand DM. Messinger DS. Isabella R. Maternal depression and the quality of early attachment: An examination of infants, preschoolers, and their mothers. Dev Psychol. 1995;31:364–376. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Downey G. Coyne JC. Children of depressed parents: An integrative review. Psychol Bull. 1990;108:50–76. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heneghan AM. Silver EJ. Bauman LJ. Westbrook LE. Stein RE. Depressive symptoms in inner-city mothers of young children: Who is at risk? Pediatrics. 1998;102:1394–1400. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.6.1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wells KB. Sturm R. Sherbourne CD. Meredith LS. Caring for depression. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaudron LH. Szilagyi PG. Kitzman HJ. Wadkins HI. Conwell Y. Detection of postpartum depressive symptoms by screening at well-child visits. Pediatrics. 2004;113:551–558. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.3.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McLennan JD. Kotelchuck M. Cho H. Prevalence, persistence, and correlates of depressive symptoms in a national sample of mothers of toddlers. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:1316–1323. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200111000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davies BR. Howells S. Jenkins M. Early detection and treatment of postnatal depression in primary care. J Adv Nurs. 2003;44:248–255. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brennan PA. Andersen MJ. Hammen C. Bor W. Najman JM. Williams GH. Chronicity, severity and timing of maternal depressive symptoms: Relationships with child outcomes at age 5. Dev Psychol. 2000;36:759–766. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.36.6.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ashman SB. Dawsong Panagiotides H. Trajectories of maternal depression over 7 years: Relations with child psychophysiology and behavior and role of contextual risks. Dev Psychopathol. 2008;20:55–77. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hammen C. Brennan PA. Severity, chronicity and timing of maternal depression and risk for adolescent offspring diagnoses in a community sample. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:253–258. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.3.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horwitz SM. Briggs-Gowan MJ. Storfer-Isser A. Carter AS. Prevalence, correlates and persistence of maternal depression. J Womens Health. 2007;16:678–691. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.NICHD Early Childcare Research Network. Chronicity of maternal depressive symptoms, maternal sensitivity and child functioning at 36 months. Dev Psychol. 1999;35:1297–1310. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.5.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pascoe JM. Stolfi A. Ormond MB. Correlates of mothers' persistent depressive symptoms. A national study. J Pediatr Health Care. 2006;20:261–269. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spence SH. Najman JM. Bor W. O'Callaghan MJ. Williams GM. Maternal anxiety and depression, poverty and marital relationship factors during early childhood as predictors of anxiety and depressive symptoms in adolescence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2002;43:457–469. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Briggs-Gowan MJ. Carter AS. Skuban EK. Horwitz SM. Prevalence of social-emotional and behavioral problems in a community sample of 1 and 2 year-old children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:811–819. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200107000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Briggs-Gowan MJ. Carter AS. Bosson-Heenan J. Guyer A. Horwitz SM. Are infant-toddler social-emotional and behavioral problems transient? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:849–858. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000220849.48650.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beck AT. Epstein N. Brown G. Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:893–897. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moos R. Moos B. Family Environment Scale manual. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cochrane R. Robertson A. The Life Events Inventory: A measure of the relative severity of psycho-social stressors. J Psychosom Res. 1973;17:135–140. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(73)90014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holmes TH. Rahe RH. The Social Readjustment Rating Scale. J Psychosom Res. 1967;11:213–218. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(67)90010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sherbourne CD. Stewart AL. The MOS Social Support Survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32:705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abidin RR. Parenting stress index short form—Test manual. Charlottesville, VA: Pediatric Psychology Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Little RJA. Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. 2nd. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dennis CL. Can we identify mothers at risk for postpartum depression in the immediate postpartum period using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale? J Affect Disord. 2004;78:163–169. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00299-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chaudron LH. Kitzman HJ. Szilagyi PG. Sidora-Arcoleo K. Anson E. Changes in maternal depressive symptoms across the postpartum year at well child care visits. Ambul Pediatr. 2006;6:221–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weissman MM. Pilowsky DJ. Wickramaratne PJ, et al. Remissions in maternal depression and child psychopathology. JAMA. 2006;295:1389–1398. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.12.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brown GW. Moran PM. Single mothers, poverty and depression. Psychol Med. 1997;27:21–33. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796004060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cairney J. Boyle M. Offord DR. Racine Y. Stress, social support and depression in single and married mothers. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2003;38:442–449. doi: 10.1007/s00127-003-0661-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Overbeek G. Vollebergh W. de Graaf R. Scholte R. de Kemp R. Engels R. Longitudinal associations of marital quality and marital dissolution with the incidence of DSM-III-R disorders. J Fam Psychol. 2006;20:284–291. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kemper KJ. Kelleher K. Olson AL. Letter to the editor. Pediatrics. 2007;120:448–449. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]