Abstract

The objective of this study was to examine the factor structure, internal consistency reliability, and responsiveness of the Self-Assessment of Nursing Informatics Competencies Scale (SANICS). Combined BS/MS nursing students (N=336) completed the 93-item scale, which was based upon published and locally-developed nursing informatics competency statements. Exploratory principal component analysis with oblique promax rotation extracted five factors comprising 30 items that explained 63.7% of the variance: clinical informatics role (α = .91), basic computer knowledge and skills (α =.94), applied computer skills: clinical informatics (α =.89), nursing informatics attitudes (α =.94), and wireless device skills (α =.90). Scale responsiveness was supported by significantly higher factor scores following an informatics course. This study provided preliminary evidence for the factor structure, internal consistency reliability and responsiveness of the 30-item SANICS. Further testing other samples is recommended.

Keywords: nursing informatics competency, nursing student, measurement scale, computer literacy

1. Introduction

The implementation of information technologies in care settings is on the rise. Consequently, the nursing workforce must be adequately prepared to use such technologies to support the delivery of patient-centered care [1, 2]. Informatics competencies are increasingly considered a basic skill for every nurse and have been delineated by several investigators and organizations [3, 4] Additionally, a number of instruments have been developed to measure some aspect of computer-related competencies in nursing [5].

Toward the goal of ensuring that graduates were prepared to use information technologies to promote safe and evidence-based nurse care, investigators at the Columbia University School of Nursing developed a 93-item self-assessment based upon published and locally-developed competency statements [4, 7]. The primary source of items for the Self-Assessment of Nursing Informatics Competencies Scale (SANICS) was Staggers et al.'s Delphi study of informatics competencies. Competencies for the beginning nurse and experience nurse were chosen for inclusion in SANICS. Additional items were developed related to standardized terminologies, evidence-based practice, and wireless communication because these were addressed in our nursing informatics curriculum. Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1= not competent to 5 = expert).

2. Objective

The objective of this study was to examine the factor structure, internal consistency reliability, and responsiveness of SANICS.

3. Methods

3.1.Sample/Setting

The sample included 337 nursing students who entered the baccalaureate portion of their combined BS/MS program in 2006 (N = 158) or 2007 (N = 178). All students were participating in a curriculum (Wireless Informatics for Safe and Evidence-based Advanced Practice Nurse Care [WISE-APN]) that emphasized the use of informatics tools to support patient safety mindfulness, modeling, and monitoring. This included didactic lectures on patient safety and informatics tools as well as Web-based reporting of hazards and near misses [6].

3.2.Steps in Psychometric Analysis

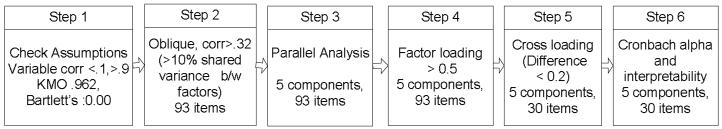

Data were analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 16.0 software (Chicago, IL, USA). Principal components analysis (Figure 1) was used to explore the factor structure of SANICS. Following examination of correlation matrix, communalities, and factor loadings, promax rotation (Step 2) with Kaiser normalization was selected because of correlations among factors [7]. To determine the number of factors (i.e., components) to be retained, parallel analysis (Step 3), which compares the unrotated (initial) eigenvalues to eigenvalues from a random sample with the same number of cases and variables and is considered more replicable than the Kaiser rule or Scree plot, was conducted [8]. A score of at least 0.50 on the primary loading of items after rotation was used as the cutoff for retention of items (Step 4). Item reduction was achieved through examination of the loading of items across factors (Step 5) and the impact of the item on internal consistency reliability (Cronbach's α) of the component (Step 6) [9]. Responsiveness of scale over time was assessed using independent sample t-tests.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the principal components analysis

4. Results

4.1.Sample

The sample was predominantly female (76.8%) aged from 20-30 (55.4%) (Table 1). Most of respondents in class of 2007 were white and non-Hispanic (61.8%) followed by 13.5% Asian and non-Hispanic. The majority of the sample uses the computer several times a day (87.1). Most (98.7%) respondents had used computers >2 years.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Sample

| 2006 - 2007 | 2007 - 2008 | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 158 | N = 178 | N = 336 | ||||

| Variable | N | % | N | % | N | % |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 102 | 64.6 | 156 | 87.6 | 258 | 76.8 |

| Male | 14 | 8.9 | 15 | 8.4 | 29 | 8.6 |

| Missing Data | 42 | 26.6 | 7 | 3.9 | 49 | 14.6 |

| Frequency of Computer Use | ||||||

| Several times /day | 98 | 62.0 | 98 | 55.1 | 196 | 58.3 |

| Once / day | 16 | 10.1 | 9 | 5.1 | 25 | 7.4 |

| Several times / week | 1 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.6 | 2 | 0.6 |

| Several times /months or never | 1 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.6 | 2 | 0.6 |

| Missing Data | 42 | 26.6 | 69 | 38.8 | 111 | 33.0 |

| Length of Computer Use | ||||||

| In the past six months | 2 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.6 |

| In the past two years | 1 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.3 |

| More than 2 years | 113 | 71.5 | 109 | 61.2 | 222 | 66.1 |

| Missing Data | 42 | 26.6 | 69 | 38.8 | 111 | 33.0 |

| Age | ||||||

| 20-29 | 90 | 57.0 | 96 | 53.9 | 186 | 55.4 |

| 30-39 | 20 | 12.7 | 11 | 6.2 | 31 | 9.2 |

| 40-49 | 4 | 2.5 | 2 | 1.1 | 6 | 1.8 |

| 50-64 | 1 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.3 |

| Missing Data | 43 | 27.2 | 69 | 38.8 | 112 | 33.3 |

4.2.Psychometric Analyses

No inter-item correlations were >.9 or <.1). The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure for sampling adequacy was high (0.96), and Bartlett's test of sphericity was significant (p <.0001). All but one item had communalities above 0.5. The principal component analysis followed by parallel analysis and item reduction techniques, resulting in a five-factor, 30-item solution (α =.95) that explained 63.7% of the variance (Table 2). Four factor scales relate to clinical informatics competencies: Clinical informatics role, Applied computer skills: Clinical informatics, Clinical informatics attitudes, and Wireless device skills. Factor 2, Basic computer knowledge and skills, comprised 15 generic items related to computer knowledge and skills that had the highest mean pre-test score (M=3.86) among the factors.

Table 2.

Results of Principal Component Analysis: Five-Factor solution

| Items | Factors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 1. Clinical informatics role (5 items, α = .91, N = 328, M (SD) = 2.62 (.91)) | |||||

| As a clinician (nurse), participate in the selection process, design, implementation and evaluation of systems. | .83 | ||||

| Market self, system, or application to others | .82 | ||||

| Promote the integrity of and access to information to include but not limited to confidentiality, legal, ethical, and security issues | .82 | ||||

| Seek resources to help formulate ethical decisions in computing | .83 | ||||

| Act as advocate of leaders for incorporating innovations and informatics concepts into their area of specialty | .83 | ||||

|

2. Basic computer knowledge and skills (15 items, α = .94, N = 321, M (SD) = 3.86 (.71)) | |||||

| Use telecommunication devices | .73 | ||||

| Use the Internet to locate, download items of interest | .70 | ||||

| Use database management program to develop a simple database | .68 | ||||

| Use database applications to enter and retrieve information | .81 | ||||

| Conduct on-line literature searches | .74 | ||||

| Use presentation graphics to create slides, displays | .74 | ||||

| Use multimedia presentations | .74 | ||||

| Use word processing | .72 | ||||

| Use networks to navigate systems | .75 | ||||

| Use operating systems | .74 | ||||

| Use existing external peripheral devices | .79 | ||||

| Use computer technology safely | .8 | ||||

| Navigate Windows | .77 | ||||

| Identify the basic components of the computer system | .77 | ||||

| Perform basic trouble-shooting in applications | .81 | ||||

|

3. Applied computer skills: Clinical informatics (4 items, α = .89, N = 330, M (SD) = 2.45 (1.03)) | |||||

| Use applications for diagnostic coding | .71 | ||||

| Use applications to develop testing materials | .69 | ||||

| Access shared data sets | .75 | ||||

| Extract data from clinical data sets | .77 | ||||

|

4. Clinical informatics attitudes (4 items, α = .94, N = 332, M(SD) = 3.74 (.97)) | |||||

| Recognize that health computing will become more common | .82 | ||||

| Recognize human functions that can not be performed by computer | .83 | ||||

| Recognize that one does not have to be a computer programmer to make effective use of the computer in nursing | .83 | ||||

| Recognize the value of clinician involvement in the design, selection, implementation, and evaluation of applications, systems in health care | .78 | ||||

|

5. Wireless device skills (2 items, α = .90, N = 328, M(SD) = 2.75 (1.16)) | |||||

| Use wireless device to download safety and quality care resources | .77 | ||||

| Use wireless device to enter data | .76 | ||||

|

| |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|

|

|||||

| Pre-post mean difference - independent t-test | .92 * | .11 | .71* | .36* | .67* |

|

| |||||

| Sums of square loading % Extraction (cumulative) | 47.3 | 54.0 | 58.8 | 61.5 | 63.7 |

| Sums of squared loading % Rotation | 36.8 | 28.5 | 36.6 | 23.7 | 9.4 |

Extraction method: Principal Components Analysis, Rotation method: Promax with Kaiser Normalization,

P < .01 (2-tailed)

5. Discussion

Exploratory principal components analysis with oblique promax rotation resulted in a five-factor, 30-item version of SANICS which explained 63.7% of the variance. The internal consistency reliabilities were excellent for all five factor scales. Scale responsiveness was supported by significantly higher mean score in the four clinical informatics-related factor scales on post-test as compared with pre-test administration. Given the age of the participants, it was not surprising that Basic computer knowledge and skills (Factor 2), had the highest mean score at pre-test and did not significantly increase over time.

The clustering of items into the Clinical informatics role factor through the use of the promax rotation is interesting in that it highlights the important role that a nurse who is not an informatics specialist can play by virtue of their nursing expertise and generalist informatics training. This was the factor that increased the most from pre- to post-test. The study used some methods not typically applied in psychometric evaluations of nursing instruments. Among these was the technique of parallel analysis which informed the decision regarding number of factors to retain. This method is considered more replicable than using eigenvalues or Scree plot to determine the cut-off for retention.

Evidence for the reliability of validity of a study instrument is sample dependent. The sample for this analysis was young with a high-level of basic computer knowledge and skills. Moreover, the sample size of 336 met the minimum, but not optimal subjects to item ratio [10]. This may limit the stability of the factor structure.

6. Conclusions

This study provided preliminary evidence for the factor structure, internal consistency reliability, and responsiveness of the 30-item SANICS. Further testing in other samples is recommended.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by D11 HP07346 and by T32NR007969.

References

- 1.Gustafson DH, Hawkins R, Boberg E, Pingree S, Serlin RE, Graziano F, et al. Impact of a patient-centered, computer-based health information/support system. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1999;16(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00108-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norton M, Skiba DJ, Bowman J. Teaching nurses to provide patient centered evidence-based care through the use of informatics tools that promote safety, quality and effective clinical decisions. Studies in Health Technology & Informatics. 2006;122:230–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Desjardins KS, Cook SS, Jenkins M, Bakken S. Effect of an informatics for evidence-based practice curriculum on nursing informatics competencies. International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2005;74(11-12):1012–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Nurses Association . Standards of practice for nursing informatics. Amedican Nurses Association; Washington, D. C.: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hobbs SD. Clinical Nurses' Perceptions of Nursing Informatics Competencies. University of Hawaii at Manoa; Hawaii: 2007. Ph.D. Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Currie LM, Desjardins KS, Stone PW, Lai TY, Schwartz E, Schnall R, et al. Near-miss and hazard reporting: promoting mindfulness in patient safety education. Studies in Health Technology & Informatics. 2007;129(Pt 1):285–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finch H. Comparison of the performance of varimax and promax rotations: Factor structure recovery for dichotomous items. Journal of Educational Measurement. 2006;43(1):39–52. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zwick WR, Velicer WF. Comparison of 5 Rules for Determining the Number of Components to Retain. Psychological Bulletin. 1986;99(3):432–442. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costello AB, Osborne JW. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment Reseach & Evaluation. 2005;10(7):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mundfrom DJ, Shaw DG, Ke TL. Minimum sample size recommendations for conducting factor analyses. International Journal of Testing. 2005;5(2):159–168. [Google Scholar]