Abstract

In 2003, three groups around the world simultaneously discovered that KISS1R (GPR54) is a key gatekeeper of sexual maturation in both mice and men. Developmental changes in the expression of the ligand for KISS1R, kisspeptin, support its critical role in the pubertal transition. In addition, kisspeptin, a powerful stimulus of GNRH-induced gonadotropin secretion and may modulate both positive and negative sex steroid feedback effects at the hypothalamic level. Genetic studies in humans have revealed both loss-of-function and gain-of-function mutations in patients with idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and precocious puberty respectively. This review examines the kisspeptin/KISS1R pathway in the reproductive system.

Introduction

Human puberty is a mystifying process involving a complex series of hormonal events. The onset of puberty is marked by an increase in the secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GNRH) from the hypothalamus. Pulsatile secretion of GNRH triggers the release of the gonadotropins such as follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) from the pituitary gland that in turn stimulates the production of sex steroids by the gonads. Sex steroids exert negative feedback effects at both the hypothalamus and pituitary with the exception of estrogen that undergoes positive feedback at the time of the mid-cycle ovulatory surge.

Studies conducted in the 1980s and 1990s identified some of the central players in the inhibitory and stimulatory controls of the GNRH pulse generator (Kaufman et al. 1985, Terasawa & Fernandez 2001, Grumbach 2002, Ojeda et al. 2003, Plant & Barker-Gibb 2004). It seems likely that a large number of different neurotransmitters are involved in modulating the behavior of the GNRH neuron (Todman et al. 2005). The GABAergic neuronal system appears to be a substrate for ‘central inhibition’ in primates (Terasawa 2005). When GABA inhibition is removed or decreased, stimulatory input from glutamatergic neurons as well as norepinephrine and neuropeptide Y (NPY) neurons become active (Jarry et al. 1988, Terasawa & Fernandez 2001). In addition to neurotransmitters, more recently, glial cell regulation mechanisms have also been implicated in the activation of the GNRH neurons (Ojeda et al. 2003). The search for additional signals that herald the change in GNRH dynamics during puberty has continued in recent years with a genetic twist. These efforts, discussed in greater detail below, led to the discovery of the newest players in the regulation of GNRH secretion: kisspeptin and its receptor, KISS1R (previously known as GPR54).

KISS1R and its ligand kisspeptin

Although genetic studies ultimately placed KISS1R on the map as a key modulator of GNRH secretion, the biological life of KISS1R did not begin in reproduction. A member of the rhodopsin family of G-protein-coupled receptors, GPR54, was originally cloned in 1999 and was an orphan receptor until 2001 when its ligand was discovered to derive from kisspeptin (Kotani et al. 2001, Muir et al. 2001, Ohtaki et al. 2001). The longest peptide (kisspeptin 1 68–121) is known as ‘metastin’ but shorter C-terminal peptides share similar affinities and efficacies. The gene encoding kisspeptin, KISS1, has been localized to chromosome 1 and codes for a 145-amino acid protein that can be cleaved to form different length kisspeptins (West et al. 1998). C-terminal fragments have been shown to be potent KISS1R agonists (Kotani et al. 2001, Muir et al. 2001).

Interestingly, the original niche for kisspeptin was in cancer biology as it was isolated as a tumor metastasis suppressor gene in a human malignant melanoma cell line (Lee et al. 1996, Lee & Welch 1997a). Kisspeptin can suppress the metastatic potential of melanoma and breast cancer cell lines in vivo (Lee et al. 1996, Lee & Welch 1997b). More recently, the expression levels of KISS1 have been found to be reduced in several, but not all, metastatic cancer specimens (Lee & Welch 1997b, Shirasaki et al. 2001, Sanchez-Carbayo et al. 2003, Dhar et al. 2004, Ikeguchi et al. 2004, Masui et al. 2004, Jiang et al. 2005, Ohta et al. 2005, Zohrabian et al. 2007).

Kisspeptin and pregnancy

While a relationship between kisspeptin’s metastasis suppressor properties and the neuroendocrine role is not yet clear, high levels of kisspeptin have been discovered in the peripheral blood of pregnant women (Horikoshi et al. 2003). Moreover, prominent expression of KISS1R and kisspeptin has been demonstrated in human placenta at higher levels during the first trimester of pregnancy in comparison with the term placenta (Janneau et al. 2002). In fact, kisspeptin inhibits trophoblast invasion during placental formation (Bilban et al. 2004). Interestingly, decreased levels of both kisspeptin and KISS1R mRNA have been found in choriocarcinoma cells, thus suggesting an important link between kisspeptin action and trophoblast invasion during early pregnancy (Janneau et al. 2002).

Kisspeptin/KISS1R critical for puberty

The reproductive dimension of the kisspeptin/KISS1R system was revealed in late 2003, when two groups independently reported the presence of deletions and inactivating mutations of KISS1R in patients with idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (IHH), a condition characterized by low sex steroids and gonadotropin levels (de Roux et al. 2003, Seminara et al. 2003). Along with the reporting of the loss-of-function mutations in humans, phenotypic characterization of mice with targeted deletion of Kiss1r was also described (Funes et al. 2003, Seminara et al. 2003). The Kiss1r knockout mice also displayed hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, demonstrating parallelism to the human disease model. In total, the linkage studies, in vitro assays, and mouse characterization established that KISS1R and its ligand play a fundamental role in the control of reproductive function in mammals.

Following these genetic discoveries, the pathway encompassed by kisspeptin and its receptor, KISS1R, has been the focus of intense study by investigators across several disciplines. The remainder of this review will explore the various models, particularly in vivo, that have led to the remarkable exposition of the reproductive roles of kisspeptin and KISS1R.

Differential hypothalamic expression

Several studies have explored the distribution and temporal patterns of kisspeptin expression. Kisspeptin-expressing neurons are present in the arcuate nucleus (Arc), the periventricular nucleus (PeN), and the anteroventral periventricular nucleus (AVPV) in mice (Gottsch et al. 2004, Smith et al. 2005a, 2005b). Additional, but more subtle, expression is seen in the anterodorsal preoptic area and the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis.

Kisspeptin appears to undergo differential expression in distinct hypothalamic nuclei. Kisspeptin expression in the AVPV is sexually dimorphic, with much greater expression in females (Smith et al. 2005b). Gonadectomy increases the number of detectable Kiss1 mRNA-expressing neurons as well as the content of Kiss1 mRNA per cell in the Arc. Sex steroid replacement reduces Kiss1 expression back to that of intact animals (Smith et al. 2005a, 2005b). These observations suggest that kisspeptin may modulate the negative feedback on GNRH secretion exerted by sex steroids. By contrast, gonadectomy decreases Kiss1 expression in the AVPV and sex steroid replacement restores it. This suggests that kisspeptin participates in the positive feedback loop is seen in the female estrous cycle (Smith et al. 2005a, 2005b). Indeed, administration of kisspeptin-blocking antibodies to the brains of female rats blocks the mid-cycle LH surge (Adachi et al. 2007). Therefore, sex steroids appear to play a major role in kisspeptin expression, though many questions remain about how kisspeptin can stimulate transcription in one nucleus and repress it in another.

In contrast to the rodent, information on KISS1 expression in the human is still quite limited. In the infundibular nucleus (corresponding to the Arc), post-menopausal woman have a higher number of kisspeptin-expressing neurons, an increased size of the neurons, and an increased quantity of kisspeptin mRNA per cell when compared with premenopausal woman (Rometo et al. 2007), confirming also in humans a possible role of this nucleus in the negative feedback on GNRH exerted by estrogens. These results are consistent with data from ovariectomized cynomolgus monkeys (Rometo et al. 2007). Comprehensive studies on the expression of kisspeptin across the human reproductive development have yet to be performed.

In mice and monkeys, Kiss1 mRNA levels in the hypothalamus are low prior to sexual maturation but increase dramatically at the time of sexual development (Han et al. 2005, Shahab et al. 2005). Both male and female rats undergo considerable augmentation of hypothalamic Kiss1 mRNA expression during the transition from juvenile to adult life (Navarro et al. 2004a). More specifically, Kiss1 expression in the mouse AVPV (both number of neurons and kisspeptin content per cell) is greater in adult than in prepubertal animals (Han et al. 2005). In monkeys, KISS1 mRNA increases in the hypothalamus across sexual maturation in both agonalad males and intact females. KISS1R mRNA increases in intact females as well, suggesting that increased expression of this pathway is the key to the timing of sexual development (Shahab et al. 2005).

In addition to increase in kisspeptin expression, kisspeptin tone appears to play a pivotal role in the onset and pacing of reproductive development. In sexually immature female rats, chronic administration of kisspeptin (6 days) advances the timing of sexual maturation as evidenced by precocious vaginal opening (Navarro et al. 2004b). In the human, mutations within the kisspeptin/KISS1R pathway establish varying degrees of kisspeptin ‘tone’ with clear effects on the timing and pace of pubertal development. As mentioned earlier, loss-of-function mutations in the gene encoding kisspeptin’s receptor, KISS1R, cause hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Recently, a gain-of-function mutation in KISS1R has been identified in a patient with central precocious puberty (Teles et al. 2008). Therefore, kisspeptin is an indisputable gatekeeper of pubertal function.

Impact of metabolic and environmental factors on kisspeptin expression

Fasting has a well-known inhibitory effect on gonadotropin secretion and ovulation. Paradoxically, GNRH gene expression at the hypothalamus is not reduced in the fasted state (Bergendahl et al. 1992). This suggests that modifications of the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis in fasting occur upstream from the GNRH synthesis pathways. Because of the considerable data pointing to kisspeptin as a critical gatekeeper for GNRH neuronal function, the interplay between energy stores, kisspeptin expression, and activation of the reproductive cascade has been explored by some investigators. Short-term fasting in male and female prepubertal rats simultaneously reduces Kiss1 mRNA and increases Kiss1r mRNA levels compared with rats fed ad libitum (Castellano et al. 2005). Treatment with kisspeptin can restore indices of pubertal maturation in the majority of animals as well as reverse the suppressed gonadotropin and sex steroid levels. Leptin may be a link between the kisspeptin pathway and metabolism. The content of Kiss1 mRNA in the Arc is significantly reduced in ob/ob compared with WT mice, and partially restored by leptin administration (Smith et al. 2006). Moreover, almost a half of Kiss1 mRNA-expressing cells in the Arc express also leptin receptor mRNA, suggesting that kisspeptin is a key to the metabolic regulation of reproductive function (Smith et al. 2006).

Similar to undernutrition, uncontrolled diabetes in rodents is also characterized by decreased LH secretion (Jackson & Hutson 1984, Steger et al. 1989, Dong et al. 1991, Sexton & Jarow 1997). GNRH release is maintained in streptozotocin (STZ)-treated rats (Spindler-Vomachka & Johnson 1985, Clough et al. 1998), suggesting that the defect underlying the hypogonadotropism in these animals lies upstream from the GNRH neurons. Moreover, kisspeptin administration stimulates LH release in STZ-treated rats (Castellano et al. 2006). In turn, it has recently been shown that kisspeptin is able to reduce glucose-induced insulin secretion (but not basal insulin levels) in a dose-dependent manner, probably through a direct effect on pancreatic B cells, profiling a diabetogenic role of kisspeptin (Silvestre et al. 2008). In animals that breed seasonally, the length of the light–darkness cycle has a potent effect on reproductive function. In sheep, changes in the light–darkness cycle have been shown to modulate KISS1 expression in the Arc. Specifically, the number of KISS1 mRNA-expressing cells is reduced during seasonal anestrus and augmented at the onset of the breeding season (Smith et al. 2007). Administration of kisspeptin to seasonally acyclic ewes can induce ovulation (Caraty et al. 2007). Kisspeptin, therefore, appears to mediate the effects of multiple modulators of the reproductive endocrine axis including metabolism, energy stores, and light–darkness cycles.

Kisspeptin administration to intact animals: powerful stimulus to gonadotropin release

Kisspeptin peptides are powerful stimulators of gonadotropin secretion in several mammalian species, including rodents (Gottsch et al. 2004, Matsui et al. 2004, Navarro et al. 2004a, 2004b, 2005a, 2005b, Thompson et al. 2004, Messager et al. 2005), sheep (Smith et al. 2007), monkeys (Shahab et al. 2005, Plant et al. 2006), and even humans (Dhillo et al. 2005). The stimulatory effect of kisspeptin is extraordinary high, as intracerebral doses as low as 100/fmol evoke nearly maximal LH responses (Gottsch et al. 2004). The effects of kisspeptin on LH can be completely abrogated by a GNRH antagonist, demonstrating that it is acting through the GNRH receptor to stimulate LH release (i.e., hypothalamic effect; Gottsch et al. 2004, Shahab et al. 2005). Kisspeptin is unable to stimulate LH release when given to Kiss1r knockout mice, suggesting that the stimulatory effects of this peptide are mediated only through this receptor (Messager et al. 2005).

Method of administration

In addition to timing and dose, the method of administration of kisspeptin may be equally critical in eliciting the gonadotropin response. Parallel to the classic experiments of Belchetz and Knobil with GNRH administration three decades ago (Belchetz et al. 1978), the mode of administration of kisspeptin (continuous versus intermittent) has profound effects on its ability to elicit gonadotropin secretion (Seminara et al. 2006). Continuous infusion of high-dose kisspeptin 112–121 (metastin 45–54) to juvenile, agonadal male rhesus monkeys initially stimulates LH release, but then abolishes the LH response (Seminara et al. 2006). The sustained suppression of LH levels during continuous exposure to kisspeptin is secondary to desensitization or down-regulation of KISS1R.

The finding has not only physiological but also therapeutic implications. In clinical practice, reversible suppression of the pituitary–gonadal axis is often a desired endpoint in the treatment of certain reproductive cancers, endometriosis, and infertility. The fact that continuous kisspeptin administration can also bring about the suppression of LH levels, suggests that it (or its analogues) might be novel therapeutic possibilities for the treatment of reproductive disorders in the future.

Return to genetics

In 2001, ~40% of probands with autosomal recessive normosmic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (IHH) and 10–17% of sporadic cases were found to harbor mutations in the GNRHR, the gene encoding the GNRH receptor (Beranova et al. 2001, Bo-Abbas et al. 2003). Clearly, additional genes were awaiting discovery.

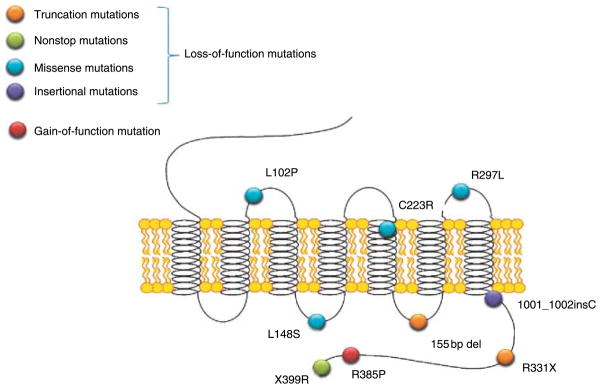

As briefly described earlier in 2003, groups independently identified KISS1R as a gatekeeper of puberty (de Roux et al. 2003, Seminara et al. 2003). de Roux et al. (2003) recruited a consanguineous family in which five out of eight children had IHH. Seminara et al. (2003) studied a large Saudi Arabian family in which three marriages between first cousins produced six affected and thirteen unaffected offspring. In both pedigrees, a genome-wide scan led to evidence for linkage on chromosome 19 and ultimately the discovery of mutations in KISS1R. Since 2003, other loss-of-function KISS1R mutations have been discovered and characterized (de Roux et al. 2003, Seminara et al. 2003, Lanfranco et al. 2005, Semple et al. 2005, Tenenbaum-Rakover et al. 2007). Mutations in KISS1R span the length of the receptor without a ‘hotspot’ (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

The currently known mutations in the human KISS1R gene.

Although the number of KISS1R mutations reported in the literature is small, there are some unifying characteristics in the patients who harbor them. Anosmia, midline facial defects, and skeletal anomalies do not figure prominently. All individuals with homozygous or compound heterozygote mutations fail to undergo pubertal development, while heterozygous family members are devoid of obvious reproductive phenotypes. Patients with KISS1R mutations retain responsiveness to both exogenous pulsatile GNRH and gonadotropins (Seminara et al. 2003, Pallais et al. 2006). During 10-min blood sampling, low-amplitude LH pulses can still be detected in patients with KISS1R mutations (Seminara et al. 2003, Pallais et al. 2006). Therefore, loss-of-function mutations seem to reduce GNRH without interfering with the intrinsic GNRH pulse generator (de Roux et al. 2003, Seminara et al. 2003).

As with GNRHR mutations, the prevalence of KISS1R mutations is higher among familial than non-familial probands. However, mutations are much more common in GNRHR than in KISS1R (Cerrato et al. 2006). Considering GNRH and KISS1R together, it is reasonable for patients with normosmic IHH undergo genetic screening.

If loss-of-function mutations in KISS1R cause IHH, could gain-of-function mutations cause central precocious puberty? Recently, a new KISS1R mutation (R385P) was identified in an 8-year-old adopted Brazilian female with precocious puberty (Teles et al. 2008). In in vitro studies, the mutated receptor was found to exhibit prolonged activation of second messenger signaling pathways compared with wild-type KISS1R.

Targeted deletion of Kiss1r and Kiss1

In general, both Kiss1r−/− and Kiss1−/− mice mirror their human counterparts with abnormal sexual development (Funes et al. 2003, Seminara et al. 2003, d’Anglemont de Tassigny et al. 2007, Lapatto et al. 2007). Female mutants have delayed vaginal opening, whereas mutant males have shorter anogenital distance. Mutant mice of both sexes exhibit small gonads, reduced levels of FSH and LH, and infertility. Despite these markers of hypogonadism, there are some interesting paradoxes in the mice. Both Kiss1r−/− and Kiss1−/− male knockouts demonstrate spermatogenesis although it is impaired (d’Anglemont de Tassigny et al. 2007, Lapatto et al. 2007). In addition, some female mutant mice exhibit partial sexual maturation, with about half of Kiss−/− females and a smaller proportion of Kiss1r−/− females demonstrating persistent vaginal cornification (Lapatto et al. 2007). Detailed studies of estrous cycling and sexual behavior will be required to fully understand the phenotypes of these animals.

In conclusion, the kisspeptin/KISS1R system has been demonstrated to have a crucial role in the initiation of sexual maturation across mammalian species and maintenance of the normal reproductive function. Further studies will continue to elucidate the richness and complexity underlying the biology of the pathway. In addition, understanding kisspeptin and KISS1R physiology may aid the development of new reproductive therapies.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that would prejudice the impartiality of this scientific work.

References

- Adachi S, Yamada S, Takatsu Y, Matsui H, Kinoshita M, Takase K, Sugiura H, Ohtaki T, Matsumoto H, Uenoyama Y, et al. Involvement of anteroventral periventricular metastin/kisspeptin neurons in estrogen positive feedback action on luteinizing hormone release in female rats. Journal of Reproduction and Development. 2007;53:367–378. doi: 10.1262/jrd.18146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belchetz PE, Plant TM, Nakai Y, Keogh EJ, Knobil E. Hypophysial responses to continuous and intermittent delivery of hypopthalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone. Science. 1978;202:631–633. doi: 10.1126/science.100883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beranova M, Oliveira LM, Bédécarrats GY, Schipani E, Vallejo M, Ammini AC, Quintos JB, Hall JE, Martin KA, Hayes FJ, et al. Prevalence, phenotypic spectrum, and modes of inheritance of gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor mutations in idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2001;86:1580–1588. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.4.7395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergendahl M, Wiemann JN, Clifton DK, Huhtaniemi I, Steiner RA. Short-term starvation decreases POMC mRNA but does not alter GnRH mRNA in rat brain. Neuroendocrinology. 1992;56:913–920. doi: 10.1159/000126324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilban M, Ghaffari-Tabrizi N, Hintermann E, Bauer S, Molzer S, Zoratti C, Malli R, Sharabi A, Hiden U, Graier W, et al. Kisspeptin-10, a KiSS-1/metastin-derived decapeptide, is a physiological invasion inhibitor of primary human trophoblasts. Journal of Cell Science. 2004;117:1319–1328. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bo-Abbas Y, Acierno JS, Jr, Shagoury JK, Crowley WF, Jr, Seminara SB. Autosomal recessive idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism: genetic analysis excludes mutations in the gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) and GnRH receptor genes. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2003;88:2730–2737. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caraty A, Smith JT, Lomet D, Ben Saïd S, Morrissey A, Cognie J, Doughton B, Baril G, Briant C, Clarke IJ. Kisspeptin synchronizes preovulatory surges in cyclical ewes and causes ovulation in seasonally acyclic ewes. Endocrinology. 2007;148:5258–5267. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellano JM, Navarro VM, Fernández-Fernández R, Nogueiras R, Tovar S, Roa J, Vazquez MJ, Vigo E, Casanueva FF, Aguilar E, et al. Changes in hypothalamic KiSS-1 system and restoration of pubertal activation of the reproductive axis by kisspeptin in undernutrition. Endocrinology. 2005;146:3917–3925. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellano JM, Navarro VM, Fernández-Fernández R, Roa J, Vigo E, Pineda R, Dieguez C, Aguilar E, Pinilla L, Tena-Sempere M. Expression of hypothalamic KiSS-1 system and rescue of defective gonadotropic responses by kisspeptin in streptozotocin-induced diabetic male rats. Diabetes. 2006;55:2602–2610. doi: 10.2337/db05-1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerrato F, Shagoury J, Kralickova M, Dwyer A, Falardeau J, Ozata M, Van Vliet G, Bouloux P, Hall JE, Hayes FJ, et al. Coding sequence analysis of GNRHR and GPR54 in patients with congenital and adultonset forms of hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2006;155(Supplement 1):S3–S10. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough RW, Kienast SG, Steger RW. Reproductive endocrinopathy in acute streptozotocin-induced diabetic male rats. Studies on LHRH. Endocrine. 1998;8:37–43. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:8:1:37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d’Anglemont de Tassigny X, Fagg LA, Dixon JP, Day K, Leitch HG, Hendrick AG, Zahn D, Franceschini I, Caraty A, Carlton MB, et al. Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism in mice lacking a functional Kiss1 gene. PNAS. 2007;104:10714–10719. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704114104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar DK, Naora H, Kubota H, Maruyama R, Yoshimura H, Tonomoto Y, Tachibana M, Ono T, Otani H, Nagasue N. Downregulation of KiSS-1 expression is responsible for tumor invasion and worse prognosis in gastric carcinoma. International Journal of Cancer. 2004;111:868–872. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhillo WS, Chaudhri OB, Patterson M, Thompson EL, Murphy KG, Badman MK, McGowan BM, Amber V, Patel S, Ghatei MA, et al. Kisspeptin-54 stimulates the hypothalamic–pituitary gonadal axis in human males. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2005;90:6609–6615. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Q, Lazarus RM, Wong LS, Vellios M, Handelsman DJ. Pulsatile LH secretion in streptozotocin-induced diabetes in the rat. Journal of Endocrinology. 1991;131:49–55. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1310049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funes S, Hedrick JA, Vassileva G, Markowitz L, Abbondanzo S, Golovko A, Yang S, Monsma FJ, Gustafson EL. The KiSS-1 receptor GPR54 is essential for the development of the murine reproductive system. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2003;312:1357–1363. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.11.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottsch ML, Cunningham MJ, Smith JT, Popa SM, Acohido BV, Crowley WF, Seminara S, Clifton DK, Steiner RA. A role for kisspeptins in the regulation of gonadotropin secretion in the mouse. Endocrinology. 2004;145:4073–4077. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grumbach MM. The neuroendocrinology of human puberty revisited. Hormone Research. 2002;57:2–14. doi: 10.1159/000058094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han SK, Gottsch ML, Lee KJ, Popa SM, Smith JT, Jakawich SK, Clifton DK, Steiner RA, Herbison AE. Activation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons by kisspeptin as a neuroendocrine switch for the onset of puberty. Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25:11349–11356. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3328-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horikoshi Y, Matsumoto H, Takatsu Y, Ohtaki T, Kitada C, Usuki S, Fujino M. Dramatic elevation of plasma metastin concentrations in human pregnancy: metastin as a novel placenta-derived hormone in humans. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2003;88:914–919. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeguchi M, Yamaguchi K, Kaibara N. Clinical significance of the loss of KiSS-1 and orphan G-protein-coupled receptor (hOT7T175) gene expression in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Clinical Cancer Research. 2004;10:1379–1383. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-1519-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson FL, Hutson JC. Altered responses to androgen in diabetic male rats. Diabetes. 1984;33:819–824. doi: 10.2337/diab.33.9.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janneau JL, Maldonado-Estrada J, Tachdjian G, Miran I, Motté N, Saulnier P, Sabourin JC, Coté JF, Simon B, Frydman R, et al. Transcriptional expression of genes involved in cell invasion and migration by normal and tumoral trophoblast cells. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2002;87:5336–5339. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarry H, Perschl A, Wuttke W. Further evidence that preoptic anterior hypothalamic GABAergic neurons are part of the GnRH pulse and surge generator. Acta Endocrinologica. 1988;118:573–579. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.1180573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Berk M, Singh LS, Tan H, Yin L, Powell CT, Xu Y. KiSS1 suppresses metastasis in human ovarian cancer via inhibition of protein kinase C alpha. Clinical & Experimental Metastasis. 2005;22:369–376. doi: 10.1007/s10585-005-8186-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman JM, Kesner JS, Wilson RC, Knobil E. Electrophysiological manifestation of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone pulse generator activity in the rhesus monkey: influence of alpha-adrenergic and dopaminergic blocking agents. Endocrinology. 1985;116:1327–1333. doi: 10.1210/endo-116-4-1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotani M, Detheux M, Vandenbogaerde A, Communi D, Vanderwinden JM, Le Poul E, Brézillon S, Tyldesley R, Suarez-Huerta N, Vandeput F, et al. The metastasis suppressor gene KiSS-1 encodes kisspeptins, the natural ligands of the orphan G protein-coupled receptor GPR54. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:34631–34636. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104847200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanfranco F, Gromoll J, von Eckardstein S, Herding EM, Nieschlag E, Simoni M. Role of sequence variations of the GnRH receptor and G protein-coupled receptor 54 gene in male idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2005;153:845–852. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapatto R, Pallais JC, Zhang D, Chan YM, Mahan A, Cerrato F, Le WW, Hoffman GE, Seminara SB. Kiss1/mice exhibit more variable hypogonadism than gpr54/mice. Endocrinology. 2007;148:4927–4936. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Welch DR. Identification of highly expressed genes in metastasis-suppressed chromosome 6/human malignant melanoma hybrid cells using subtractive hybridization and differential display. International Journal of Cancer. 1997a;71:1035–1044. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970611)71:6<1035::aid-ijc20>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Welch DR. Suppression of metastasis in human breast carcinoma MDA-MB-435 cells after transfection with the metastasis suppressor gene, KiSS-1. Cancer Research. 1997b;57:2384–2387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Miele ME, Hicks DJ, Phillips KK, Trent JM, Weissman BE, Welch DR. KiSS-1, a novel human malignant melanoma metastasis-suppressor gene. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1996;88:1731–1737. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.23.1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masui T, Doi R, Mori T, Toyoda E, Koizumi M, Kami K, Ito D, Peiper SC, Broach JR, Oishi S, et al. Metastin and its variant forms suppress migration of pancreatic cancer cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2004;315:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui H, Takatsu Y, Kumano S, Matsumoto H, Ohtaki T. Peripheral administration of metastin induces marked gonadotropin release and ovulation in the rat. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2004;320:383–388. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.05.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messager S, Chatzidaki EE, Ma D, Hendrick AG, Zahn D, Dixon J, Thresher RR, Malinge I, Lomet D, Carlton MB, et al. Kisspeptin directly stimulates gonadotropin-releasing hormone release via G protein-coupled receptor 54. PNAS. 2005;102:1761–1766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409330102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir AI, Chamberlain L, Elshourbagy NA, Michalovich D, Moore DJ, Calamari A, Szekeres PG, Sarau HM, Chambers JK, Murdock P, et al. AXOR12, a novel human G protein-coupled receptor, activated by the peptide KiSS-1. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:28969–28975. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102743200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro VM, Castellano JM, Fernández-Fernández R, Barreiro ML, Roa J, Sanchez-Criado JE, Aguilar E, Dieguez C, Pinilla L, Tena-Sempere M. Developmental and hormonally regulated messenger ribonucleic acid expression of KiSS-1 and its putative receptor, GPR54, in rat hypothalamus and potent luteinizing hormone-releasing activity of KiSS-1 peptide. Endocrinology. 2004a;145:4565–4574. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro VM, Fernández-Fernández R, Castellano JM, Roa J, Mayen A, Barreiro ML, Gaytan F, Aguilar E, Pinilla L, Dieguez C, et al. Advanced vaginal opening and precocious activation of the reproductive axis by KiSS-1 peptide, the endogenous ligand of GPR54. Journal of Physiology. 2004b;561:379–386. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.072298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro VM, Castellano JM, Fernández-Fernández R, Tovar S, Roa J, Mayen A, Barreiro ML, Casanueva FF, Aguilar E, Dieguez C, et al. Effects of KiSS-1 peptide, the natural ligand of GPR54, on follicle-stimulating hormone secretion in the rat. Endocrinology. 2005a;146:1689–1697. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro VM, Castellano JM, Fernández-Fernández R, Tovar S, Roa J, Mayen A, Nogueiras R, Vazquez MJ, Barreiro ML, Magni P, et al. Characterization of the potent luteinizing hormone-releasing activity of KiSS-1 peptide, the natural ligand of GPR54. Endocrinology. 2005b;146:156–163. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta S, Lai EW, Pang AL, Brouwers FM, Chan WY, Eisenhofer G, de Krijger R, Ksinantova L, Breza J, Blazicek P, et al. Downregulation of metastasis suppressor genes in malignant pheochromocytoma. International Journal of Cancer. 2005;114:139–143. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtaki T, Shintani Y, Honda S, Matsumoto H, Hori A, Kanehashi K, Terao Y, Kumano S, Takatsu Y, Masuda Y, et al. Metastasis suppressor gene KiSS-1 encodes peptide ligand of a G-protein-coupled receptor. Nature. 2001;411:613–617. doi: 10.1038/35079135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda SR, Prevot V, Heger S, Lomniczi A, Dziedzic B, Mungenast A. Glia-to-neuron signaling and the neuroendocrine control of female puberty. Annals of Medicine. 2003;35:244–255. doi: 10.1080/07853890310005164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallais JC, Bo-Abbas Y, Pitteloud N, Crowley WF, Jr, Seminara SB. Neuroendocrine, gonadal, placental, and obstetric phenotypes in patients with IHH and mutations in the G-protein coupled receptor, GPR54. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2006;254–255:70–77. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plant TM, Barker-Gibb ML. Neurobiological mechanisms of puberty in higher primates. Human Reproduction Update. 2004;10:67–77. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmh001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plant TM, Ramaswamy S, Dipietro MJ. Repetitive activation of hypothalamic G protein-coupled receptor 54 with intravenous pulses of kisspeptin in the juvenile monkey (Macaca mulatta) elicits a sustained train of gonadotropin-releasing hormone discharges. Endocrinology. 2006;147:1007–1013. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rometo AM, Krajewski SJ, Voytko ML, Rance NE. Hypertrophy and increased kisspeptin gene expression in the hypothalamic infundibular nucleus of postmenopausal women and ovariectomized monkeys. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2007;92:2744–2750. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Roux N, Genin E, Carel JC, Matsuda F, Chaussain JL, Milgrom E. Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism due to loss of function of the KiSS1-derived peptide receptor GPR54. PNAS. 2003;100:10972–10976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834399100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Carbayo M, Capodieci P, Cordon-Cardo C. Tumor suppressor role of KiSS-1 in bladder cancer: loss of KiSS-1 expression is associated with bladder cancer progression and clinical outcome. American Journal of Pathology. 2003;162:609–617. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63854-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seminara SB, Messager S, Chatzidaki EE, Thresher RR, Acierno JS, Jr, Shagoury JK, Bo-Abbas Y, Kuohung W, Schwinof KM, Hendrick AG, et al. The GPR54 gene as a regulator of puberty. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;349:1614–1627. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seminara SB, Dipietro MJ, Ramaswamy S, Crowley WF, Jr, Plant TM. Continuous human metastin 45–54 infusion desensitizes G protein-coupled receptor 54-induced gonadotropin-releasing hormone release monitored indirectly in the juvenile male Rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta): a finding with therapeutic implications. Endocrinology. 2006;147:2122–2126. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semple RK, Achermann JC, Ellery J, Farooqi IS, Karet FE, Stanhope RG, O’rahilly S, Aparicio SA. Two novel missense mutations in g protein-coupled receptor 54 in a patient with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2005;90:1849–1855. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sexton WJ, Jarow JP. Effect of diabetes mellitus upon male reproductive function. Urology. 1997;49:508–513. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(96)00573-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahab M, Mastronardi C, Seminara SB, Crowley WF, Ojeda SR, Plant TM. Increased hypothalamic GPR54 signaling: a potential mechanism for initiation of puberty in primates. PNAS. 2005;102:2129–2134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409822102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirasaki F, Takata M, Hatta N, Takehara K. Loss of expression of the metastasis suppressor gene KiSS1 during melanoma progression and its association with LOH of chromosome 6q16.3-q23. Cancer Research. 2001;61:7422–7425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvestre RA, Egido EM, Hernández R, Marco J. Kisspeptin-13 inhibits insulin secretion without affecting glucagon or somatostatin release: study in the perfused rat pancreas. Journal of Endocrinology. 2008;196:283–290. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JT, Cunningham MJ, Rissman EF, Clifton DK, Steiner RA. Regulation of Kiss1 gene expression in the brain of the female mouse. Endocrinology. 2005a;146:3686–3692. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JT, Dungan HM, Stoll EA, Gottsch ML, Braun RE, Eacker SM, Clifton DK, Steiner RA. Differential regulation of KiSS-1 mRNA expression by sex steroids in the brain of the male mouse. Endocrinology. 2005b;146:2976–2984. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JT, Acohido BV, Clifton DK, Steiner RA. KiSS-1 neurones are direct targets for leptin in the ob/ob mouse. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 2006;18:298–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2006.01417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JT, Clay CM, Caraty A, Clarke IJ. KiSS-1 messenger ribonucleic acid expression in the hypothalamus of the ewe is regulated by sex steroids and season. Endocrinology. 2007;148:1150–1157. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spindler-Vomachka M, Johnson DC. Altered hypothalamic–pituitary function in the adult female rat with streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Diabetologia. 1985;28:38–44. doi: 10.1007/BF00276998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steger RW, Amador A, Lam E, Rathert J, Weis J, Smith MS. Streptozotocin-induced deficits in sex behavior and neuroendocrine function in male rats. Endocrinology. 1989;124:1737–1743. doi: 10.1210/endo-124-4-1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teles MG, Bianco SD, Brito VN, Trarbach EB, Kuohung W, Xu S, Seminara SB, Mendonca BB, Kaiser UB, Latronico AC. A GPR54-activating mutation in a patient with central precocious puberty. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;358:709–715. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenenbaum-Rakover Y, Commenges-Ducos M, Iovane A, Aumas C, Admoni O, de Roux N. Neuroendocrine phenotype analysis in five patients with isolated hypogonadotropic hypogonadism due to a L102P inactivating mutation of GPR54. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2007;92:1137–1144. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terasawa E. Role of GABA in the mechanism of the onset of puberty in non-human primates. International Review of Neurobiology. 2005;71:113–129. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(05)71005-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terasawa E, Fernandez DL. Neurobiological mechanisms of the onset of puberty in primates. Endocrine Reviews. 2001;22:111–151. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.1.0418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson EL, Patterson M, Murphy KG, Smith KL, Dhillo WS, Todd JF, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR. Central and peripheral administration of kisspeptin-10 stimulates the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 2004;16:850–858. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2004.01240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todman MG, Han SK, Herbison AE. Profiling neurotransmitter receptor expression in mouse gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons using green fluorescent protein-promoter transgenics and microarrays. Neuroscience. 2005;132:703–712. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West A, Vojta PJ, Welch DR, Weissman BE. Chromosome localization and genomic structure of the KiSS-1 metastasis suppressor gene (KISS1) Genomics. 1998;54:145–148. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zohrabian VM, Nandu H, Gulati N, Khitrov G, Zhao C, Mohan A, Demattia J, Braun A, Das K, Murali R, et al. Gene expression profiling of metastatic brain cancer. Oncology Reports. 2007;18:321–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]