Abstract

Sequential actions of 17β-estradiol (E2) and progesterone (P4) in the hypothalamus and the P4 metabolite, 5α-pregnan-3α-ol-20-one (3α,5α-THP), in the midbrain ventral tegmental area (VTA) respectively mediate the initiation and intensity of lordosis of female rats and mayalso modulate anxiety and social behaviors, through actions in these, and/or other brain regions. Biosynthesis of E2, P4, and 3α,5α-THP can also occur in brain, independent of peripheral gland secretion, in response to environmental/behavioral stimuli. The extent to which engaging in tasks related to reproductive behaviors and/or mating increased E2 or progestin concentrations in brain was investigated. In Experiment 1, proestrous rats were randomly assigned to be tested in individual tasks, including the open field, elevated plus maze, partner preference, social interaction, or no test control, in conjunction with paced mating or no mating. Engaging in paced mating, but not other behaviors, significantly increased dihydroprogesterone (DHP) and 3α,5α-THP levels in midbrain, hippocampus, striatum, and cortex. In Experiment 2, proestrous rats were tested in the combinations of the above tasks (open field and elevated plus maze, partner preference, and social interaction) with or without paced mating. As in Experiment 1, only engaging in paced mating increased DHP and 3α,5α-THP concentrations in midbrain, hippocampus, striatum, and cortex. Thus, paced mating enhances concentrations of 5α-reduced progestins in brain areas associated with reproduction (midbrain), as well as exploration/anxiety (hippocampus and striatum) and social behavior (cortex).

Introduction

Increased production of the ovarian hormones, 17β-estradiol (E2) and progesterone (P4), which occurs during proestrus of rodents, modulate lordosis (the stereotypical posture that female rodents exhibit in response to male-typical stimuli in order for successful mating to occur). Systemic or intra-brain administration of E2 and/or P4 to the ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH) of ovari-ectomized rats reveals that the actions of these hormones are sufficient to initiate lordosis (Rubin & Barfield 1984, Pleim et al. 1993). However, P4 also has effects in other brain regions, such as the ventral tegmental area (VTA) to influence the duration and intensity of lordosis (Frye 2001). In addition to divergent effects of P4 in the VMH and VTA to alter sex behavior, there are also differences in P4’s mechanisms of action in these regions. In the VMH, E2 and P4 initiate lordosis through classical actions at intracellular progestin receptors (PRs). However, in the VTA, P4 modulates the duration and intensity of lordosis responses following metabolism to, and/or de novo synthesis of, 5α-pregnan-3α-ol-20-one (3α,5α-THP) and its subsequent actions at GABAA, dopamine-like type 1, and/or NMDA receptors and downstream signal transduction processes (Frye & Vongher 1999, Farye & Petralia 2003, Petralia & Frye 2003, Frye et al. 2004, Sumida et al. 2005). Using lordosis as a bioassay has revealed some of the mechanisms by which 3α,5α-THP in the VTA facilitates mating; however, 3α,5α-THP also has other important functional effects.

3α,5α-THP can influence exploratory, anti-anxiety, approach, social, and aggressive behaviors. Administration of P4 or 3α,5α-THP to ovariectomized and/or adrenalectomized rats increases exploration, anxiolysis, approach, and social behavior to levels which are commensurate with that of proestrous rats, which have naturally elevated progestin levels (Bitran et al. 1999, Frye & Walf 2004, Jain et al. 2005, Shen et al. 2005) and blocking P4’s metabolism to 3α,5α-THP attenuates these effects (Rhodes & Frye 2001, Frye & Walf 2002, Reddy et al. 2005, Walf et al. 2005). Among male rodents, 3α,5α-THP administration typically increases aggressive behavior, whereas in females 3α,5α-THP generally has a suppressive effect on agonistic behavior (DeBold & Miczek 1981, Fish et al. 2001, Pinna et al. 2005). These data suggest that 3α,5α-THP manipulations can enhance exploration, anti-anxiety, pro-social, and anti-aggressive behaviors, which may engender facilitation of reproduction.

In addition to manipulations of 3α,5α-THP having effects on mating and related behaviors, experiential factors can also influence production of 3α,5α-THP in the brain. Rodents exposed to cold water-swim, foot shock, or ether have rapid and robust increases in biosynthesis of neurosteroids, such as 3α,5α-THP, in the brain, which occur in the absence of peripheral sources of steroid hormones (Purdy et al. 1991, Erskine & Kornberg 1992, Drugan et al. 1993, Barbaccia et al. 1996). Mating can also increase 3α,5α-THP biosynthesis. Mating of naturally receptive or hormone-primed, ovariectomized and/or adrenalectomized rodents increases 3α,5α-THP concentrations in midbrain over that of non-mated rats (Frye & Bayon 1999, Frye & Vongher 1999, Frye 2001). As well, rats that can ‘pace’, or control their sexual contacts with a male, have enhanced luteal function, fertility, fecundity, serum P4, and whole brain 3α,5α-THP levels when compared with rats mated in a standard paradigm, which cannot control receipt and/or timing of their sexual contacts (Erskine et al. 1989, Frye & Erskine 1990, Coopersmith & Erskine 1994, Frye et al. 1996, 1998). However, the extent to which engaging in reproductive and related behaviors may alter progestin biosynthesis has not been well characterized.

Paced mating, when compared with standard mating, in a laboratory setting is more similar to naturalistic and semi-natural mating insofar as female rodents exert much more control over the mating process by leaving the male after a contact and remaining apart for several minutes (McClintock & Adler 1978, Erskine 1985, Frye & Erskine 1990, Xiao & Becker 1997, Frye et al. 1998, Zipse et al. 2000, Gardener & Clark 2001, Jenkins & Becker 2001, Gonzalez-Flores et al. 2004, Coria-Avila et al. 2005). Paced mating is characterized by greater expression of exploratory, approach, anti-anxiety, reproductive, and aggressive behaviors when compared with standard mating and altering 3α,5α-THP levels can influence expression of these behaviors. Although there is some evidence that paced mating can increase 3α,5α-THP production, where this occurs in the brain, and whether engaging in exploratory, approach, anti-anxiety, and/or social behavior alone can elicit these increases, is of interest. To investigate this, in Experiment 1, proestrous rats engaged in individual tasks used as indices of exploration (open field), anxiety (elevated plus maze), and pro-social (partner preference and social interaction) behaviors either alone, or in conjunction with, paced mating and effects on progestin concentrations in areas involved in mediating these behaviors (midbrain, hippocampus, striatum, and cortex) were examined. In Experiment 2, proestrous rats engaged in exploratory/anxiety (open field and elevated plus maze) or social (partner preference and social interaction) behaviors with or without engaging in paced mating. If exploratory, anxiety, or social behaviors are sufficient to influence progestin production, then engaging in exploratory, anxiety, or social behaviors should increase progestin concentrations in brain areas involved in these processes (hippocampus, striatum, and cortex). Alternatively, if mating is necessary to increase progestin concentrations, then only rats that engage in paced mating would be expected to have increased progestin concentrations in the midbrain, an important brain region for reproductive behavior.

Materials and Methods

These methods were pre-approved by the Institutional Care and Use Committee at The University at Albany-SUNY.

Animals and housing

Adult, intact female Long–Evans rats (N = 211) were obtained from the breeding colony of the Laboratory Animal Care Facility in the Life Sciences Research Building at The University at Albany-SUNY (original stock Taconic Farms, Germantown, NY, USA). Rats were group-housed in a temperature- and humidity-controlled room on a reverse light cycle (lights off at 0800 h) with water and rat chow in their cages and allowed to feed ad libitium. All testing occurred between 0800 and 1300 h.

Determination of estrous cycle phase

Estrous cycle phase was determined by daily examination of vaginal epithelium (between 0700 and 0800 h), per previous methods (Long & Evans 1922, Frye et al. 2000). Rats were cycled through two normal estrous cycles (4–5 day cycle) prior to testing. All rats were tested on the evening of proestrus, which is characterized by the presence of many nucleated epithelial cells, when E2 levels are declining, but progestin levels are high (Feder 1984, Frye & Bayon 1999).

Behavioral testing

Affective tasks utilized in the present studies are described below. Following testing in these tasks, some rats were allowed to engage in paced mating while others were not. Specific procedures for each experiment are detailed below.

Behavioral data were collected with the ANY-Maze data collection program (Stoelting Co., Wheat Dale, IL, USA) and by one of the two observers. There was a 97% concordance rate between data that was collected by ANY-Maze and that collected by the observer.

Open field

Behavior in the open field is an index of exploration, anxiety, and motor behavior (Blizard et al. 1975, Frye et al. 2000). The open field (76 × 57 × 35 cm) has a 48-square grid floor (6 × 8 squares, 9.5 cm/side): there is an overhead light illuminating the central squares (all but the 24 perimeter squares were considered central). Per previous methods, rats were placed in the open field and the path of their exploration was recorded for 5 min. The number of central, peripheral, and total entries was then calculated from these data as indices of anxiolysis, thigmotaxis, and motor behavior respectively.

Elevated plus maze

Behavior in the elevated plus-maze is also utilized to assess exploration, anxiety, and motor behavior (File 1993, Frye et al. 2000). The plus-maze was elevated 50 cm off the ground and consisted of four arms (49 cm in length and 10 cm in width). Two arms were enclosed by walls 30 cm in height and the other two arms were exposed. As per the previous methods, rats were placed at the juncture of the open and closed arms and the number of entries into, and the amount of time spent on, the open and closed arms were recorded during a 5-min test. Time spent on the open arms is an index of anxiety and the total number of arm entries is a measure of motor activity.

Partner preference

A modified version of the previously established partner preference task was utilized to assess preference for an intact male or a conspecific (Baum 1969, Frye et al. 2000). Experimental rats were placed in the center of an open field (76 × 57 × 35 cm) that contained an ovari-ectomized stimulus female and an intact stimulus male in opposite corners, each of which was enclosed in Plexiglass compartments with small holes (1 cm in diameter) drilled in the bottom portion of the enclosure exposed to the center of the open field, so that experimental rats could receive visual and olfactory stimulation from stimulus rats in the absence of physical contact. The amount of time that experimental rats spent within a body’s length of stimulus animals was recorded in a 5-min test. Increased time spent in close proximity to one stimulus rat versus another is an indication of a preference for that animal.

Social interaction

The social interaction task assessed exploratory and anxiety behavior associated with interacting with a novel conspecific (Frye et al. 2000, File & Seth 2003). Each member of a pair of rats (one experimental and one stimulus) was placed in opposite corners of an open field (76 × 57 × 35 cm). The total duration of time that experimental rats engaged an ovariectomized stimulus rat in crawling over and under partner, sniffing of partner, following with contact, genital investigation of partner, tumbling, boxing, and grooming was recorded during a 5-min test (Frye et al. 2000). An ovariectomized rat was utilized as the stimulus animal in order to avoid the possibility of vaginocervical stimulation of experimental rats, which might occur if a male rat had been used as the stimulus animal. Duration of time spent interacting with a conspecific is an index of anxiety behavior.

Paced mating

Paced mating was utilized over standard mating because of its greater ethological relevance and procedures were carried out as previously reported (McClintock & Adler 1978, Erskine 1985, Frye & Erskine 1990, Gans & Erskine 2003). Paced mating tests were conducted in a chamber (37.5 × 75 × 30 cm), which was equally divided by a partition that had a small (5 cm in diameter) hole in the bottom center, to allow a female free access to both sides of the chamber, but which prevented the larger stimulus male from moving between sides. Females were placed in the side of the chamber opposite to the stimulus male. Rats were behaviorally tested for an entire ejaculatory series. Behaviors recorded were the frequency of mounts and intromissions that preceded an ejaculation. As well, the frequency (lordosis quotient = incidence of lordosis/number of mounts) and intensity (lordosis rating) of lordosis, quantified by rating of dorsiflexion on a scale of 0–3 (Hardy & DeBold 1972) was recorded. The percentage of proceptive (i.e., hopping, darting, ear wiggling, proceptivity quotient) and aggressive (i.e., vocalizations, defensive postures, aggression quotient) behaviors prior to contacts was also recorded. Pacing measures included the percentage of times the female left the compartment containing the male after receiving a particular copulatory stimuli (percentage exits after mounts, intromissions, and ejaculations) and latencies in seconds to return to the male compartment after these stimuli. The normal pattern of pacing behaviors for percentage exits and return latencies to be longer after more intensive stimulation (ejaculations > intro-missions > mounts) was observed in the present study.

Tissue collection

Immediately following testing, whole brains and trunk blood were collected for later measurement of E2, P4, DHP, and 3α,5α-THP. Trunk blood was centrifuged at 3000 g for 10 min, serum was stored in eppendorfs at −80 °C. Brains were rapidly frozen on dry ice and stored at −80 °C for approximately 1 month prior to RIA.

Tissue preparation

Serum was thawed on ice and steroids extracted as described below. Immediately prior to measurement of steroids, brains were thawed and midbrain, hippocampus, striatum, and cortex were grossly dissected. The brain was initially positioned ventral side up for dissection. The anterior and posterior borders for gross dissection of midbrain were the optic chiasm and pontine regions respectively. The lateral borders were ~1.5 mm from midline and the dorsal aspect was just ventral to the cerebral aqueduct. For striatum, anterior/posterior boundaries for dissection were the accumbens and optic chiasm, the lateral aspects were ~1.5 mm from midline, and the dorsal/ventral aspects were between the hypothalamus and thalamus and core and shell of the accumbens. For the dissection of hippocampus and cortex, brains were turned over. Intact bilateral hippocampus, including amygdala, was separated out from cortex. Bilateral anterior cortical tissues (~2 mm dorsal to olfactory bulbs) were dissected and used for cortex measurements. Following dissection, steroids were extracted from midbrain, hippocampus, striatum, and cortex as described below.

RIA for steroid hormones

E2, P4, DHP, and 3α,5α-THP concentrations were measured as described below, using previously reported methods (Frye et al. 1996, Choi & Dallman 1999, Frye & Bayon 1999).

Radioactive probes

E2 (NET-317, 51.3 Ci/mmol), P4 (NET-208: specific activity = 47.5 Ci/mmol), and 3α,5α-THP (used for DHP and 3α,5α-THP; NET-1047: specific activity = 65.0 Ci/mmol), were purchased from Perkin–Elmer (Boston, MA, USA).

Extraction of steroids from serum

E2, P4, DHP, and 3α,5α-THP were extracted from serum with ether following incubation with water and 800 c.p.m. of 3H steroid (Frye & Bayon 1999). After snap-freezing twice, test tubes containing steroid and ether were evaporated to dryness in a Savant. Dried down tubes were reconstituted with phosphate assay buffer to the original serum volume.

Extraction of steroids from brain tissues

E2, P4, DHP, and 3α,5α-THP were extracted from brain tissues following homogenization with a glass/glass homogenizer in 50% MeOH and 1% acetic acid. Tissues were centrifuged at 3000 g and the supernatant was chromatographed on Sepak-cartridges equilibrated with 50% MeOH:1% acetic acid. Steroids were eluted with increasing concentrations of MeOH (50% MeOH followed by 100% MeOH). Solvents were removed using a speed drier. Samples were reconstituted in 300 μl assay buffer.

Set-up and incubation of RIAs

The range of the standard curves was 0–1000 pg for E2, and 0–8000 pg for P4, DHP, and 3α,5α-THP. Standards were added to assay buffer followed by addition of the appropriate antibody (described below) and 3H steroid. Total assay volumes were 800 μl for E2 and P4, 950 0μl for DHP, and 1250 μl for 3α,5α-THP. All assays were incubated overnight at 4 °C, except for E2, which incubated at room temperature for 50 min respectively.

Antibodies

The E2 antibody (E#244, Dr G D Niswender, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA), which generally binds between 40 and 60% of [3H]E2, was used in a ratio of 1:40 000 dilution and bound 54% in the present study. The P4 antibody (P#337 from Dr G D Niswender, Colorado State University) used in a ratio of 1:30 000 dilution typically binds between 30 and 50% of [3H]P4, and bound 48% in the present study. The DHP (X-947) and 3α,5α-THP antibodies (#921412-5, purchased from Dr Robert Purdy, Veterans Medical Affairs, La Jolla, CA, USA) used in a ratio of 1:5000 dilution bind between 40 and 60% of [3H]3α,5α-THP and bound 47% in the present study.

Termination of binding

Separation of bound and free steroid was accomplished by the rapid addition of dextran-coated charcoal. Following incubation with charcoal, samples were centrifuged at 3000 g and the supernatant was pipetted into a glass scintillation vial with 5 ml scintillation cocktail. Sample tube concentrations were calculated using the logit–log method of Rodbard & Hutt (1974), interpolation of the standards, and correction for recovery with Assay Zap. The inter- and intra-assay reliability coefficients were: E2 0.06 and 0.08, P4 0.10 and 0.11, DHP 0.10 and 0.09, and 3α,5α-THP 0.10 and 0.11.

Procedure

Experiment 1

In order to determine whether individual exploratory or social tasks, with or without engaging in paced mating, can alter progestin concentrations in brain, rats were exposed to an individual task. Some rats were tested in the open field (n = 20), elevated plus maze (n = 20), partner preference (n = 20), or social interaction tasks (21), or not tested (n = 20). Other rats were tested in the open field (n = 22), elevated plus maze (n = 20), partner preference (n = 20), or social interaction tasks (n = 22), or not tested (n = 22) in conjunction with paced mating. Immediately following testing, trunk blood and whole brains were collected for later steroid hormone measurement. Two-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were used to examine effects of individual affective tasks (open field, elevated plus maze, partner preference, and social interaction) and paced mating (paced mating and no paced mating) on endocrine outcomes.

Experiment 2

To ascertain whether engaging in multiple exploratory or social tasks described above would have additive effects sufficient to alter progestin concentrations, behavioral tasks were grouped according to their exploratory/anxiety versus social aspects. The open field and elevated plus maze constituted the exploratory/anxiety tasks (exploratory group) and partner preference and social interaction were considered social tasks (social group). Rats that engaged in paced mating alone or were not behaviorally tested in any tasks served as controls.

Proestrous rats were tested in the exploratory tasks (open field and elevated plus maze) with (n = 10) or without (n = 10) paced mating, social tasks (partner preference and social interaction) with (n = 10) or without (n = 10) paced mating, or served as paced mated (n = 10) or non-tested controls (n = 10). Rats were tested sequentially through assigned tasks, without rest periods between tests. Immediately following testing (or in an analogous time frame for non-tested controls), tissues were collected for later measurement of hormones. Two-way ANOVAs were utilized to examine the effects of grouped affective tasks (open field and elevated plus maze, partner preference, and social interaction) and paced mating (paced mating and no paced mating) on endocrine outcomes.

Statistical analyses

Two-way ANOVA were utilized to examine the effects of affective tasks (open field, elevated plus maze, partner preference, and social interaction) and paced mating on endocrine outcomes. Alpha level for statistical significance was P < 0.05. Where appropriate, ANOVAs were followed by Fisher’s PLSD post hoc tests to ascertain group differences. Power analyses were utilized to verify that all inferential statistics reported were valid with sufficient power. Six rats that were assigned to a pacing group in Experiment 1 did not exhibit normal pacing behavior and were excluded from further data analyses.

Results

Experiment 1: Effects of engaging in individual tasks

E2 and P4

There were no differences among groups in concentrations of E2 or P4 (Table 1) in any tissues examined. All levels were within the physiological range previously reported for proestrous rats (Frye & Bayon 1999).

Table 1.

E2 and P4 levels in serum, midbrain, hippocampus, striatum, and cortex of rats tested in the open field, elevated plus maze, partner preference, social interaction, or no task in conjunction with (yes) or without (no) paced mating.

| Open field |

Elevated plus maze |

Partner preference |

Social interaction |

None |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 20) | Yes (n = 22) | No (n = 20) | Yes (n = 20) | Yes (n = 20) | Yes (n = 20) | No (n = 21) | Yes (n = 22) | No (n = 20) | Yes (n = 20) | |

| E2 | ||||||||||

| Serum (pg/ml) | 36.0 ± 4.4 | 34.7 ± 1.0 | 32.0 ± 1.9 | 31.9 ± 1.3 | 32.1 ± 1.3 | 32.7 ± 1.0 | 30.9 ± 1.3 | 32.3 ± 1.4 | 30.7 ± 1.4 | 32.2 ± 1.8 |

| Midbrain (pg/mg) | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 3.0 ± 0.6 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 2.8 ± 0.4 | 2.9 ± 0.6 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 2.7 ± 0.4 | 2.6 ± 0.5 | 2.5 ± 0.4 | 2.2 ± 0.2 |

| Hippocampus (pg/mg) | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 2.5 ± 0.4 | 2.6 ± 0.5 | 2.3 ± 0.6 | 2.7 ± 0.4 | 2.0 ± 0.3 | 2.8 ± 0.6 | 2.1 ± 0.5 | 2.7 ± 0.7 | 2.8 ± 0.7 |

| Striatum (pg/mg) | 2.2 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 1.0 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 2.5 ± 0.5 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 2.5 ± 0.7 |

| Cortex (pg/mg) | 1.3 ± 0.5 | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 1.7 ± 0.6 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.4 |

| P4 | ||||||||||

| Plasma (ng/ml) | 17.5 ± 1.9 | 15.9 ± 0.7 | 16.4 ± 2.0 | 15.8 ± 0.6 | 16.3 ± 1.1 | 15.7 ± 0.5 | 15.4 ± 0.7 | 16.5 ± 0.5 | 16.4 ± 0.6 | 17.0 ± 0.6 |

| Midbrain (ng/mg) | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.3 | 2.2 ± 0.5 |

| Hippocampus (ng/mg) | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.5 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | 2.5 ± 0.5 | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 2.2 ± 0.4 |

| Striatum (ng/mg) | 2.1 ± 0.7 | 2.0 ± 0.5 | 2.0 ± 1.1 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 2.3 ± 0.5 |

| Cortex (ng/mg) | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 1.6 ± 0.3 |

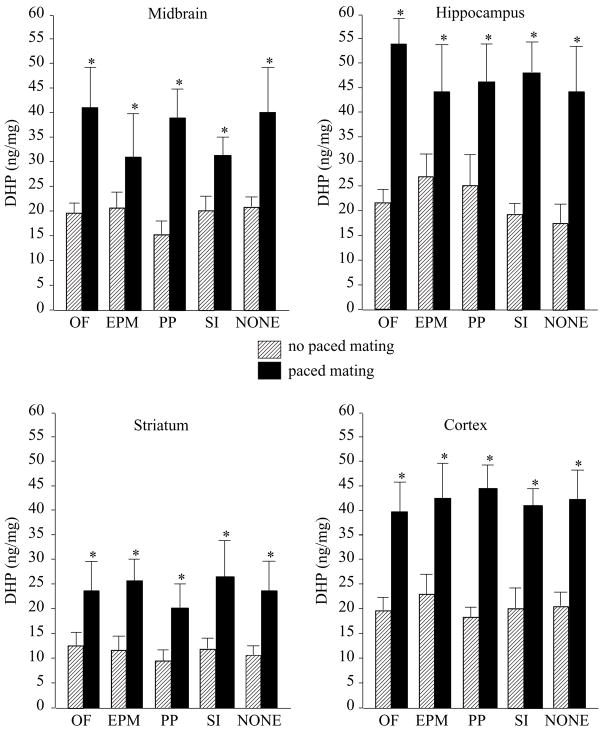

DHP

Mating, but not test condition, increased DHP in midbrain (F(1,195) = 12.61, P = 0.0005), hippocampus (F(1,195) = 9.08, P = 0.003), striatum (F(1,195) = 15.40, P = 0.0001), and cortex (F(1,195) = 30.49, P = 0.0001, Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

DHP concentrations (± S.E.M.) in midbrain (top left), hippocampus (top right), striatum (bottom left), and cortex (bottom right) of rats tested in the open field (OF, n = 20, n = 22), elevated plus maze (EPM, n = 20, n = 20), partner preference (SC, n = 20, n = 20), social interaction (SI, n = 21, n = 22), or no (NONE, n = 20, n = 20) affective task, alone (striped bars) or in conjunction with paced mating (closed bars). Asterisk indicates significantly different from respective no paced mating control group (P < 0.05).

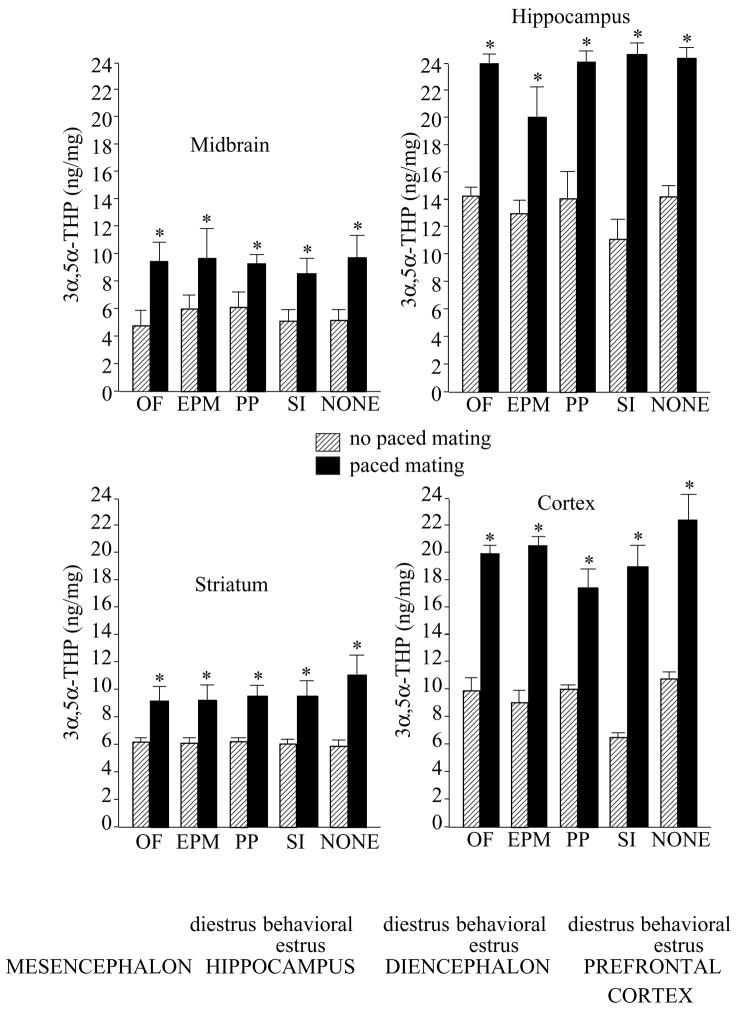

3α,5α-THP

Mating, but not test condition, also increased 3α,5α-THP concentrations in midbrain (F(1,195) = 11.49, P = 0.0008), hippocampus (F(1,195) = 16.32, P = 0.0001), striatum (F(1,195) = 29.76, P = 0.0001), and cortex (F(1,195) = 35.62, P = 0.0001, Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

α,5α-THP concentrations (± S.E.M.) in midbrain (top left), hippocampus (top right), striatum (bottom left), and cortex (bottom right) of rats tested in the open field (OF, n = 20, n = 22), elevated plus maze (EPM, n = 20, n = 20), partner preference (PP, n = 20, n = 20), social interaction (SI, n = 21, n = 22), or no (NONE, n = 20, n = 20) affective task, alone (striped bars) or in conjunction with paced mating (closed bars). Asterisk indicates significantly different from respective no paced mating control group (P < 0.05).

Failure to engage in paced mating

Rats that failed to engage in paced mating performed similarly to other rats in affective behaviors (Table 2). Further, consistent with results discussed earlier, there were no differences in E2 or P4 in any brain area examined among rats that were exposed to the paced mating task, but did not exhibit normative pacing behavior, when compared with rats that were not exposed to paced mating (Table 3). In contrast to rats that actively engaged in paced mating, rats that were exposed to paced mating, but did not engage in pacing, did not demonstrate increases in DHP or 3α,5α-THP concentrations in midbrain, hippocampus, striatum, or cortex, as was observed among rats that did engage in paced mating.

Table 2.

Behavioral data of rats that were not exposed to paced mating (no paced mating) and rats that were exposed to paced mating that either engaged (paced mating) or did not engage in paced mating (did not pace, n = 6).

| Central square entries | Open arm time | Time in proximity to male | Social interaction | Lordosis quotient | Lordosis rating | Percent exits | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No paced mating | 70 ± 5 | 34 ± 16 | 83 ± 9 | 72 + 5 | NA | NA | NA |

| Paced mating | 60 ± 7 | 46 ± 15 | 96 ± 9 | 85 + 6 | 57 ± 4 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 26 ± 2a |

| Did not pace | 51 ± 10 | 36 ± 7 | NA | NA | 37 ± 8 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 8 ± 1 |

Significantly different from rats that engaged in paced mating.

Table 3.

DHP and 3α,5α-THP levels in midbrain, hippocampus, striatum, and cortex of rats that were not exposed to paced mating (non-paced controls) or were exposed to paced mating, but failed to exhibit normative pacing behaviors.

| OF |

EPM |

None |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-paced controls (n = 20) | Failed to pace (n = 3) | Non-paced controls (n = 20) | Failed to pace (n = 2) | Non-paced controls (n = 20) | Failed to pace (n = 1) | |

| Midbrain DHP (ng/mg) | 19.7 ± 3.6 | 15.2 ± 1.7 | 21.2 ± 3.5 | 17.9 ± 3.7 | 22.1 ± 4.2 | 19.5 ± 0 |

| Midbrain 3α,5α-THP (ng/mg) | 4.6 ± 1.3 | 3.3 ± 0.1 | 6.0 ± 1.4 | 4.9 ± 0.5 | 6.0 ± 2.1 | 5.9 ± 0 |

| Hippocampus DHP (ng/mg) | 21.9 ± 3.9 | 20.0 ± 2.5 | 27.3 ± 5.1 | 20.3 ± 2.7 | 17.7 ± 3.2 | 18.2 ± 0 |

| Hippocampus 3α,5α-THP (ng/mg) | 14.3 ± 1.9 | 12.4 ± 3.3 | 13.9 ± 1.8 | 15.0 ± 1.5 | 13.2 ± 1.8 | 11.5 ± 0 |

| Striatum DHP (ng/mg) | 11.9 ± 3.3 | 10.2 ± 0.3 | 11.6 ± 2.4 | 11.5 ± 1.5 | 10.7 ± 2.6 | 9.6 ± 0 |

| Striatum 3α,5α-THP (ng/mg) | 6.1 ± 0.9 | 4.8 ± 0.4 | 6.1 ± 0.8 | 5.8 ± 0.7 | 5.6 ± 0.9 | 4.5 ± 0 |

| Cortex DHP (ng/mg) | 19.7 ± 2.9 | 18.1 ± 11.5 | 23.1 ± 4.5 | 21.2 ± 1.8 | 20.0 ± 3.1 | 16.1 ± 0 |

| Cortex 3α,5α-THP (ng/mg) | 9.9 ± 1.5 | 8.8 ± 3.2 | 8.6 ± 1.7 | 6.3 ± 0.2 | 10.9 ± 1.1 | 9.5 ± 0 |

Experiment 2: Effects of engaging in multiple tasks

E2 and P4

Concentrations of E2 and P4 (Table 4) did not differ among groups in any tissues examined.

Table 4.

E2 and P4 concentrations in serum, midbrain, hippocampus, striatum, and cortex of proestrous rats exposed to the open field (OF) and elevated plus maze (EPM) or partner preference (PP) and social interaction (SI) tasks, with or without paced mating, or non-tested controls.

| OF + EPM | OF + EPM + paced mating | PP + SI | PP + SI + paced mating | Paced mating | Non-tested controls | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E2 | ||||||

| Serum (pg/ml) | 31.9 ± 2.8 | 29.8 ± 3.4 | 29.3 ± 3.7 | 34.1 ± 2.8 | 33.7 ± 2.3 | 25.5 ± 4.1 |

| Midbrain (pg/mg) | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.1 |

| Hippocampus (pg/mg) | 2.3 ± 0.5 | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 2.7 ± 0.6 | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.1 |

| Striatum (pg/mg) | 1.9 ± 0.7 | 2.0 ± 0.5 | 1.7 ± 0.6 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.7 | 1.5 ± 0.2 |

| Cortex (pg/mg) | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 2.5 ± 0.6 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 2.2 ± 0.7 | 1.8 ± 0.1 |

| P4 | ||||||

| Serum (ng/ml) | 16.2 ± 1.3 | 19.8 ± 1.8 | 19.7 ± 1.1 | 20.5 ± 1.6 | 20.1 ± 1.5 | 17.5 ± 1.1 |

| Midbrain (ng/mg) | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 1.9 ± 0.4 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 2.4 ± 0.3 |

| Hippocampus (ng/mg) | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 1.5 ± 0.1 |

| Striatum (ng/mg) | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.1 |

| Cortex (ng/mg) | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.1 |

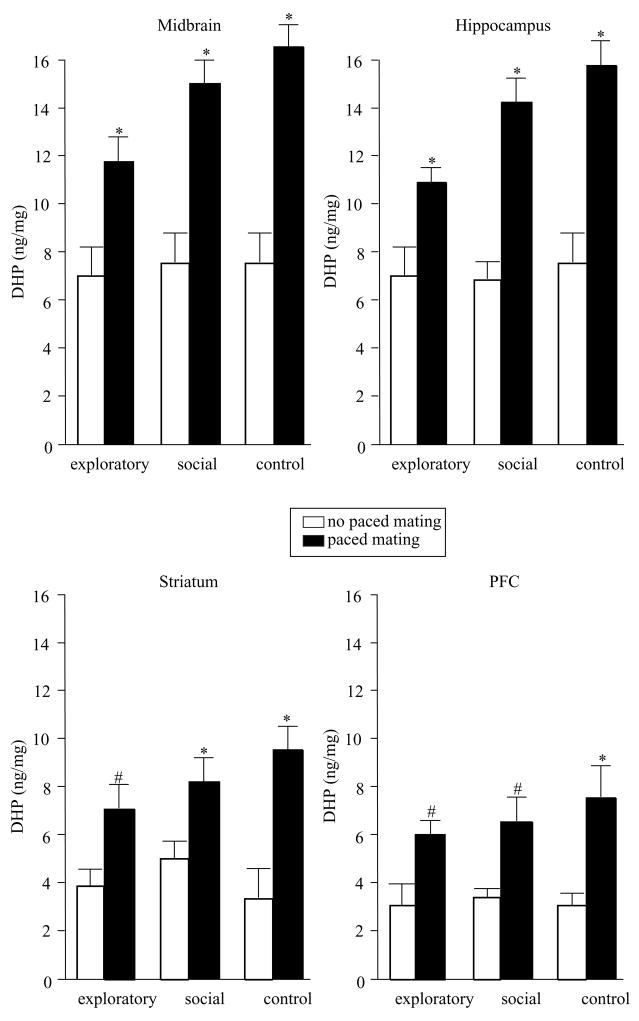

DHP

DHP levels were increased by mating, but not exploratory or social behaviors, in midbrain (F(2,54) = 34.84, P = 0.0001), hippocampus (F(2,54) = 46.59, P = 0.0001), striatum (F(2,54) = 17.21, P = 0.0001), and cortex (F(2,54) = 10.66, P = 0.001, Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Levels of DHP (± S.E.M.) in midbrain (top left), hippocampus (top right), striatum (bottom left), and cortex (bottom right) of rats tested in exploratory or social behaviors, or controls, alone (open bars) or in conjunction with paced mating (closed bars). Asterisk indicates significantly different from respective no paced mating control group (P < 0.05). # indicates (P≤0.10).

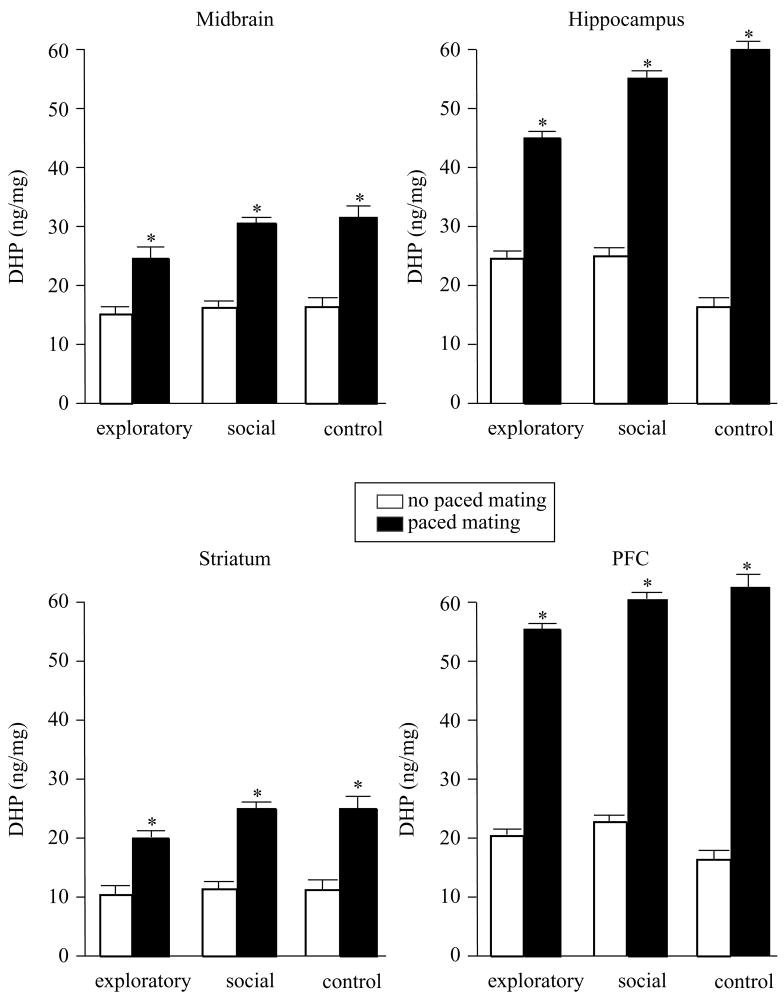

3α,5α-THP

Mating, but not exploratory or social behaviors, increased levels of 3α,5α-THP in midbrain (F(2,54) = 84.44, P = 0.0001), hippocampus (F(2,51) = 20.97, P = 0.0001), striatum (F(2,54) = 10.40, P = 0.002), and cortex (F(2,54) = 11.80, P = 0.001, Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Levels of 3α,5α-THP (± S.E.M.) in midbrain (top left), hippocampus (top right), striatum (bottom left), and cortex (bottom right) of rats tested in exploratory or social behaviors, or controls, alone (open bars) or in conjunction with paced mating (closed bars). Asterisk indicates significantly different from respective no paced mating control group (P < 0.05).

Discussion

Results of the present study supported our alternative hypothesis that engaging in mating is necessary to produce increases in progestin concentrations. Rats that engaged in paced mating, irrespective of prior exposure to other tasks, either individually or in combination, had increased DHP and 3α,5α-THP concentrations in midbrain, hippocampus, striatum, and cortex. There were no differences in E2 or P4 concentrations in any brain areas examined as a result of engaging in various exploratory (open field and elevated plus maze), social (partner preference and social interaction), or sexual behaviors. Together, these data suggest that engaging in paced mating behavior produces increases in DHP and 3α,5α-THP in areas traditionally (midbrain) and not typically (hippocampus, striatum, and cortex) associated with reproductive behavior.

The present results confirm and extend prior findings that mating can increase progestin levels. Prior investigations have demonstrated that mating increases levels of 3α,5α-THP in brain. Mating increases central levels of 3α,5α-THP of proestrous or ovariectomized and/or adrenalectomized, hormone-primed rats (Frye et al. 1996, Frye & Bayon 1999, Frye 2001). The results of the present study also demonstrate increased 3α,5α-THP concentrations in brain. Interestingly, we also saw increased levels of DHP among rats that were mated. Although our lab has focused primarily on effects of 3α,5α-THP to modulate lordosis and other reproductively relevant behaviors, these data suggest that DHP may also play an important role to influence such behaviors. Whether increases in DHP were due to increased production of DHP, back-conversion of 3α,5α-THP to DHP, or a combination of these effects was not elucidated. Notably, DHP and 3α,5α-THP have discrepant mechanisms of action. DHP has a very high affinity for intracellular PRs and is typically thought to act via more classical actions at PRs (Smith et al. 1974, Iswari et al. 1986). In contrast, 3α,5α-THP, in physiological concentrations, does not have great avidity for intracellular PRs, but is a highly effective modulator of GABAA and NMDA receptors (Gee 1988, Cyr et al. 2001, Frye 2001). Hence, both actions may be occurring in these different brain regions. Although few intracellular PRs have been identified in the midbrain, hippocampus, striatum, or cortex and those that are present are not E2-induced; it is possible that DHP has actions through these receptors to modulate exploratory, anxiety, and social behaviors. As well, GABAA receptors are present in each of the brain areas investigated (Hevers & Luddens 1998) and 3α,5α-THP can readily have actions through GABAA receptors (Gee 1988), which may underlie some of the effects observed in the present study. It is also possible that there is an integrated mechanism that involves actions at both intracellular PRs and GABAA receptors (Vasudevan et al. 2005, Frye et al. submitted). Therefore, the present data are important in that they may begin to elucidate the relative mechanisms by which progestins have their actions to modulate reproductively relevant behaviors beyond lordosis.

In the present study, the levels of DHP and 3α,5α-THP were increased not only in midbrain, as was expected, but also in hippocampus, striatum, and cortex. In a prior study, we examined the effects of non-paced mating on progestin concentrations and found mating-induced increases in 3α,5α-THP in midbrain, but not other areas (Frye & Bayon 1999). We also examined effects of specific stimuli associated with mating on 3α,5α-THP biosynthesis. Exposure to a mating arena, artificial vaginocervical stimulation (five–ten intromissions with glass eyedropper), or non-physical exposure to a male did not produce increases in 3α,5α-THP concentrations in midbrain (Frye & Bayon 1999). This is congruent with the present data in that rats that were assigned a priori to a paced mating condition but failed to pace their mating contacts did not exhibit increases in DHP or 3α,5α-THP in any brain area examined. Together, these data suggest that aspect(s) of paced mating is important for neurosteroidogenesis; however, there have been no systematic studies directly comparing effects of standard versus paced mating on progestin biosynthesis. Ongoing investigations in our lab are examining this question.

The increased biosynthesis of DHP and 3α,5α-THP in hippocampus, striatum, and cortex, areas not typically associated with mating, may reflect 3α,5α-THP’s neuromodulatory effects. 3α,5α-THP is produced de novo in brain in response to noxious stimuli to levels which can have agonist-like effects on GABAA receptors and can dampen hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal stress–responses (Purdy et al. 1991, Drugan et al. 1993, Barbaccia et al. 1996). As such, it has been proposed that 3α,5α-THP may increase parasympathetic activity and serve as an important mediator of homeostasis. The present data suggest that less extreme, more normative, experiences, such as mating, can result in similar increases in progestins. The possible implications for this may be twofold. First, information about reproductive response is readily consolidated and this is adaptive in that it increases reproductive success (Domjan et al. 2004). We have found that other types of learning are enhanced by 3α,5α-THP (Frye & Lacey 2000, Frye 2006a, Walf et al. 2006). Hence, 3α,5α-THP may act to enhance consolidation of information important for reproductive behaviors. Secondly, 3α,5α-THP’s agonist-like actions at GABAA receptors and anxiolytic effects may enable exploration, approach, and pro-social behaviors necessary for successful mating. However, the extent to which engaging in paced mating may have altered GABAA receptor function was not addressed in the present study. These are intriguing data that suggest a role for actions of progestins in the VTA, hippocampus, striatum, and cortex to mediate anxiety, exploratory, and social behaviors. However, to more directly elucidate the role of these brain areas for effects of 3α,5α-THP on the anxiety, exploratory, and social behaviors, it will be important to investigate the effects of manipulating 3α,5α-THP directly in these areas.

In summary, the present data are an intriguing extension of prior reports examining effects of mating and related stimuli on progestin biosynthesis. In addition to the expected mating-induced increases in 3α,5α-THP, we also saw increases in DHP. Further, rats that engaged in paced mating had increased levels of DHP and 3α,5α-THP in midbrain, hippocampus, striatum, and cortex. Together, these data suggest that DHP and 3α,5α-THP may be involved in reproductively relevant behaviors and that brain areas not traditionally associated with mating, the hippocampus, striatum, and cortex, may be important for these processes.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH06769801).

References

- Barbaccia ML, Roscetti G, Bolacchi F, Concas A, Mostallino MC, Purdy RH, Biggio G. Stress-induced increase in brain neuroactive steroids: antagonism by abecarnil. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1996;54:205–210. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(95)02133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum M. Paradoxical effect of alcohol on the resistance to extinction of an avoidance response in rats. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology. 1969;69:238–240. doi: 10.1037/h0028188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitran D, Dugan M, Renda P, Ellis R, Foley M. Anxiolytic effects of the neuroactive steroid pregnanolone (3α-OH-5β-pregnan-20-one) after microinjection in the dorsal hippocampus and lateral septum. Brain Research. 1999;850:217–224. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blizard DA, Lippman HR, Chen JJ. Sex differences in open-field behavior in the rat: the inductive and activational role of gonadal hormones. Physiology and Behavior. 1975;14:601–608. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(75)90188-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S, Dallman MF. Hypothalamic obesity: multiple routes mediated by loss of function in medial cell groups. Endocrinology. 1999;140:4081–4088. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.9.6964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coopersmith C, Erskine MS. Influence of paced mating and number of intromissions on fertility in the laboratory rat. Journal of Reproduction and Fertility. 1994;102:451–458. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.1020451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coria-Avila GA, Ouimet AJ, Pacheco P, Manzo J, Pfaus JG. Olfactory conditioned partner preference in the female rat. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2005;119:716–725. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.119.3.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyr M, Ghribi O, Thibault C, Morissette M, Landry M, Di Paolo T. Ovarian steroids and selective estrogen receptor modulators activity on rat brain NMDA and AMPA receptors. Brain Research. Brain Research Reviews. 2001;37:153–161. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBold JF, Miczek KA. Sexual dimorphism in the hormonal control of aggressive behavior of rats. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 1981;14:89–93. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(81)80015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domjan M, Cusato B, Krause M. Learning with arbitrary versus ecological conditioned stimuli: evidence from sexual conditioning. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review. 2004;11:232–246. doi: 10.3758/bf03196565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drugan RC, Paul SM, Crawley JN. Decreased forebrain [35S]TBPS binding and increased [3H]muscimol binding in rats that do not develop stress-induced behavioral depression. Brain Research. 1993;631:270–276. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91545-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erskine MS. Effects of paced coital stimulation on estrus duration in intact cycling rats and ovariectomized and ovariectomized–adrenalectomized hormone-primed rats. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1985;99:151–161. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.99.1.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erskine MS, Kornberg E. Stress and ACTH increase circulating concentrations of 3α-androstanediol in female rats. Life Sciences. 1992;51:2065–2071. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(92)90157-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erskine MS, Kornberg E, Cherry JA. Paced copulation in rats: effects of intromission frequency and duration on luteal activation and estrus length. Physiology and Behavior. 1989;45:33–39. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(89)90163-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feder HH. Hormones and sexual behavior. Annual Review of Psychology. 1984;35:165–200. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.35.020184.001121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- File SE. The interplay of learning and anxiety in the elevated plus-maze. Behavioural Brain Research. 1993;58:199–202. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(93)90103-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- File SE, Seth P. A review of 25 years of the social interaction test. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2003;463:35–53. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01273-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish EW, Faccidomo S, DeBold JF, Miczek KA. Alcohol, allopregnanolone and aggression in mice. Psychopharmacol. 2001;153:473–483. doi: 10.1007/s002130000587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye CA. The role of neurosteroids and non-genomic effects of progestins and androgens in mediating sexual receptivity of rodents. Brain Research Brain Research Reviews. 2001;37:201–222. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00119-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye CA. Progestins influence motivation, reward, conditioning, stress, and/or response to drugs of abuse. Pharmacology, biochemistry, and behavior. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.07.033. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye CA, Bayon LE. Mating stimuli influence endogenous variations in the neurosteroids 3α,5α-THP and 3α-Diol. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 1999;11:839–847. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1999.00379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye CA, Erskine MS. Influence of time of mating and paced copulation on induction of pseudopregnancy in cyclic female rats. Journal of Reproduction and Fertility. 1990;90:375–385. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0900375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye CA, Lacey EH. Progestins influence performance on cognitive tasks independent of changes in affective behavior. Psychobiology. 2000;28:550–563. [Google Scholar]

- Frye CA, Petralia SM. Lordosis of rats is modified by neurosteroidogenic effects of membrane benzodiazepine receptors in the ventral tegmental area. Neuroendocrinology. 2003;77:71–82. doi: 10.1159/000068338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye CA, Vongher JM. 3α,5α-THP in the midbrain ventral tegmental area of rats and hamsters is increased in exogenous hormonal states associated with estrous cyclicity and sexual receptivity. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation. 1999;22:455–464. doi: 10.1007/BF03343590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye CA, Walf AA. Changes in progesterone metabolites in the hippocampus can modulate open field and forced swim test behavior of proestrous rats. Hormones and Behavior. 2002;41:306–315. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2002.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye CA, Walf AA. Estrogen and/or progesterone administered systemically or to the amygdala can have anxiety-, fear-, and pain-reducing effects in ovariectomized rats. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2004;118:306–313. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.118.2.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye CA, McCormick CM, Coopersmith C, Erskine MS. Effects of paced and non-paced mating stimulation on plasma progesterone, 3α-diol and corticosterone. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1996;21:431–439. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(95)00059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye CA, Bayon LE, Pursnani NK, Purdy RH. The neurosteroids, progesterone and 3α,5α-THP, enhance sexual motivation, receptivity, and proceptivity in female rats. Brain Research. 1998;808:72–83. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00764-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye CA, Petralia SM, Rhodes ME. Estrous cycle and sex differences in performance on anxiety tasks coincide with increases in hippocampal progesterone and 3α,5α-THP. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 2000;67:587–596. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00392-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye CA, Walf AA, Sumida K. Progestins’ actions in the VTA to facilitate lordosis involve dopamine-like type 1 and 2 receptors. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 2004;78:405–418. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gans S, Erskine MS. Effects of neonatal testosterone treatment on pacing behaviors and development of a conditioned place preference. Hormones and Behavior. 2003;44:354–364. doi: 10.1016/s0018-506x(03)00157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardener HE, Clark AS. Systemic ICI 182,780 alters the display of sexual behaviors in the female rat. Hormones and Behavior. 2001;39:121–130. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2000.1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee KW. Steroid modulation of the GABA/benzodiazepine receptor-linked chloride ionophore. Molecular Neurobiology. 1988;2:291–317. doi: 10.1007/BF02935636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Flores O, Camacho FJ, Dominguez-Salazar E, Ramirez-Orduna JM, Dominguez-Salazar E, Ramirez-Orduna JM, Beyer C, Paredes RG. Progestins and place preference conditioning after paced mating. Hormones and Behavior. 2004;46:151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy DF, DeBold JF. Effects of coital stimulation upon behavior of the female rat. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology. 1972;78:400–408. doi: 10.1037/h0032536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hevers W, Luddens H. The diversity of GABAA receptors. Pharmacological and electrophysiological properties of GABAA channel subtypes. Molecular Neurobiology. 1998;18:35–86. doi: 10.1007/BF02741459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iswari S, Colas AE, Karavolas HJ. Binding of 5αdihydroprogesterone and other progestins to female rat anterior pituitary nuclear extracts. Steroids. 1986;47:189–203. doi: 10.1016/0039-128x(86)90088-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain NS, Hiranik K, Chopde CT. Reversal of caffeine-induced anxiety by neurosteroid 3α-hydroxy-5-α-pregnane-20-one in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48:627–638. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins WJ, Becker JB. Role of the striatum and nucleus accumbens in paced copulatory behavior in the female rat. Behavioural Brain Research. 2001;121:119–128. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00394-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long JA, Evans HM. Oestrous cycle in the rat and its associated phenomena. Memoirs of The University of California. 1922;6:1–146. [Google Scholar]

- McClintock MK, Adler NT. The role of the female during copulation in wild and domestic Norway rats Rattus Norvegicus. Behaviour. 1978;67:68–96. [Google Scholar]

- Petralia SM, Frye CA. In the ventral tegmental area, G-proteins and cAMP mediate the neurosteroid 3α,5α-THP ’s actions at dopamine type 1 receptors for lordosis of rats. Neuroendocrinology. 2003;80:233–243. doi: 10.1159/000082752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinna G, Costa E, Guidotti A. Changes in brain testosterone and allopregnanolone biosynthesis elicit aggressive behavior. PNAS. 2005;102:2135–2140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409643102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleim ET, Lipetz J, Steele TL, Barfield RJ. Facilitation of sexual receptivity by ventromedial hypothalamic implants of the anti-progestin RU 486. Hormones and Behavior. 1993;27:488–498. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1993.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purdy RH, Morrow AL, Moore PH, Jr, Paul SM. Stress-induced elevations of gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor-active steroids in the rat brain. PNAS. 1991;88:4553–4557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.10.4553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy DS, O’Malley BW, Rogawski MA. Anxiolytic activity of progesterone in progesterone receptor knockout mice. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes ME, Frye CA. Inhibiting progesterone metabolism in the hippocampus of rats in behavioral estrus decreases anxiolytic behaviors and enhances exploratory and antinociceptive behaviors. Cognitive, Affective and Behavioral Neuroscience. 2001;1:287–296. doi: 10.3758/cabn.1.3.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodbard D, Hutt DM. Symposium on radioimmunoassay and related procedures in medicine. Internationa Atomic Energy Agency; New York: Uniput: 1974. Statistical analysis of radioimmunoassay and immunoradiometric assays: a generalized, weighted iterative, least squares method for logistic curve fitting; pp. 209–223. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin BS, Barfield RJ. Progesterone in the ventromedial hypothalamus of ovariectomized, estrogen-primed rats inhibits subsequent facilitation of estrous behavior by systemic progesterone. Brain Research. 1984;294:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)91303-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen H, Gong QH, Yuan M, Smith SS. Short-term steroid treatment increases delta GABAA receptor subunit expression in rat CA1 hippocampus: pharmacological and behavioral effects. Neuropharmacology. 2005;49:573–586. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith HE, Smith RG, Toft DO, Neergaard JR, Burrows EP, O’Malley BW. Binding of steroids to progesterone receptor proteins in chick oviduct and human uterus. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1974;249:5924–5932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumida K, Walf AA, Frye CA. Progestin-facilitated lordosis of hamsters may involve dopamine-like type 1 receptors in the ventral tegmental area. Behavioural Brain Research. 2005;161:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan N, Kow LM, Pfaff D. Integration of steroid hormone initiated membrane action to genomic function in the brain. Steroids. 2005;70:388–396. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walf AA, Rhodes ME, Frye CA. Ovarian steroids enhance object recognition in naturally cycling and ovariectomized, hormone-primed rats. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2006;86:35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walf AA, Sumida K, Frye CA. Inhibiting 5α-reductase in the amygdala attenuates antianxiety and antidepressive behavior of naturally receptive and hormone-primed ovariectomized rats. Psychopharmacol. 2005;12:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0100-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L, Becker JB. Hormonal activation of the striatum and the nucleus accumbens modulates paced mating behavior in the female rat. Hormones and Behavior. 1997;32:114–124. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1997.1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipse LR, Brandling-Bennett EM, Clark AS. Paced mating behavior in the naturally cycling and the hormone-treated female rat. Physiology and Behavior. 2000;70:205–209. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(00)00242-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]