Abstract

We present a simplified method for the collection of mosquito saliva to determine Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus transmission of West Nile virus that can be used for experiments requiring large sample sizes.

Keywords: Vector competence, transmission rate, arbovirus

Virus transmission is a critical component of laboratory studies of vector competence and is essential to understanding the epidemiology of arboviruses. Mosquito transmission can be determined directly by allowing infected mosquitoes to feed on naïve susceptible vertebrate hosts and periodically assessing the host for the presence of the pathogen or clinical signs and symptoms of disease. The use of laboratory animals for transmission studies has several disadvantages, including expense, animal-welfare regulations, and the need for special facilities to maintain infected animals. Furthermore, laboratory animal models may not be useful or available for every vector–virus system (Smith et al. 2005).

The likelihood of transmission of an arbovirus by a mosquito can be determined by analyzing mosquito saliva for the pathogen; however, these studies are typically time consuming and inefficient. A common alternative is to measure midgut infection (i.e., body infection) and/or dissemination out of the midgut (i.e., leg infection), with the latter used as an indication of transmission capability. However, these indicators may not reflect transmission accurately. Often, relationships between infection, dissemination (Richards et al. 2007, 2009), and transmission rates are also dependent on biological and environmental conditions (Kilpatrick et al. 2008).

Collecting saliva to determine the presence of virus has been performed since 1966 (Hurlbut 1966). Several methods have been developed to collect saliva from mosquitoes. Methods include using capillary tubes filled with different types of media such as defibrinated blood (Aitken 1977), immersion oil (Colton et al. 2005, Smith et al. 2005), mineral oil (Hurlbut 1966) or fetal bovine serum (Mores et al. 2007). Due to the hydrophobic nature of the proboscis of Culex spp., immersion oil is the preferred media to collect saliva from this genus of mosquitoes (Colton et al. 2005). Another method of saliva collection is suspension feeding using a droplet of blood suspended on the top of the cage housing the test mosquito, allowing the mosquito to feed from the suspended droplet and then testing the droplet for the presence of virus (Gubler and Rosen 1976). However, this method may be difficult to implement with species that feed inefficiently on the suspended droplet and for experiments involving large sample sizes. It is difficult to determine the most efficient saliva collection technique to use because of the diversity of techniques presented in the literature. Here, we provide a simple device and procedure that allows an efficient and cost-effective method to collect saliva from a large number of mosquitoes to determine arbovirus transmission with Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus Say and West Nile virus (WNV).

The methods used to infect Cx. p. quinquefasciatus and sample processing to detect WNV are described elsewhere (Richards et al. 2007, 2009). Briefly, Cx. p. quinquefasciatus mosquitoes from a laboratory colony (F > 45) were offered pledgets soaked with warmed (35°C) virus-soaked blood containing 6.9–7.0 logs plaque-forming units WNV/ml and held with 20% sugar ad libitum at 28°C for a 13–14-day incubation period (IP) prior to saliva collection. The mosquitoes were then dissected by sterile techniques; the wings and legs of each mosquito were transferred to a tube containing 1 ml BA-1 diluent, and stored at −80°C until processing (Richards et al. 2009). The remaining portion of the live mosquito was used to collect saliva, then collected in a tube for total body titer determination.

Infection rate was calculated as the number of virus-positive bodies divided by the total number of mosquitoes tested. Dissemination rate was calculated as the number of mosquitoes with virus-positive bodies that also had infected legs. Transmission rate was calculated as the number of mosquitoes with virus-positive bodies that also had infected saliva.

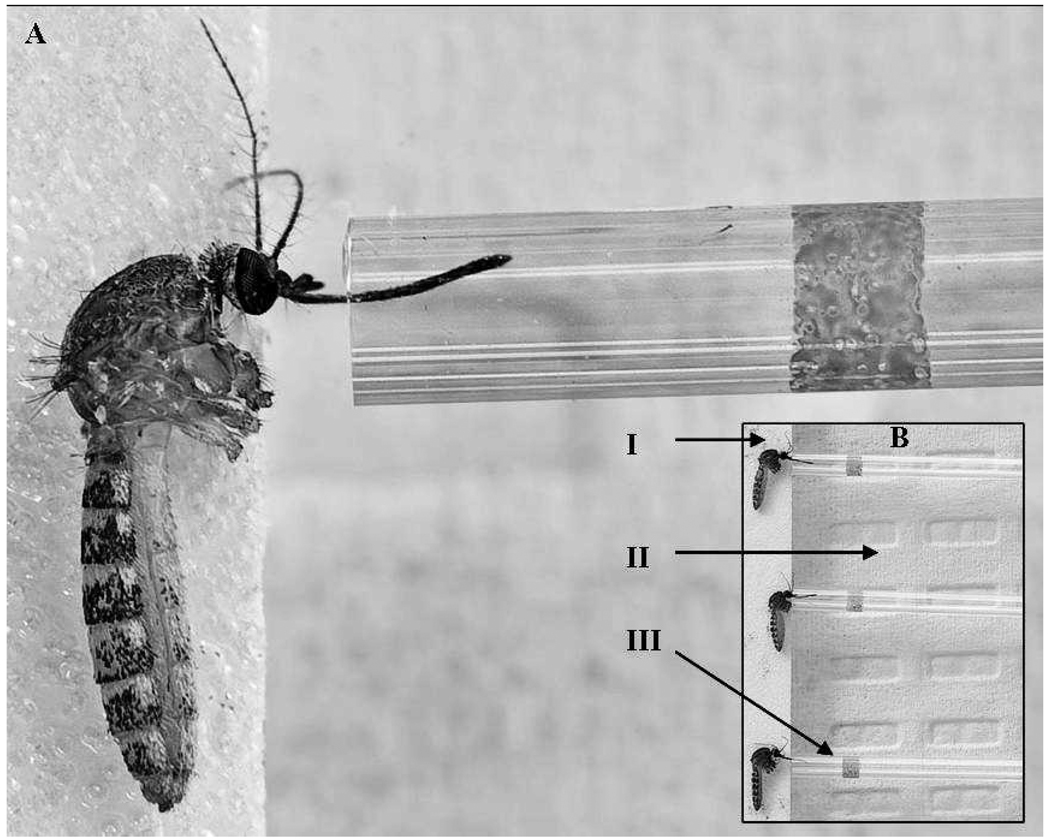

To collect saliva from mosquitoes, we adapted methods provided elsewhere (Hurlbut 1966, Aitken 1977, Cornel and Jupp 1989, Colton et al. 2005, Smith et al. 2005). A mosquito salivation device (Figs. 1A, 1B) was constructed with plexiglass (25.5 cm × 17.5 cm) as the surface on which to place mosquitoes. Laboratory bench paper was affixed under the plexiglass to create a white background for better visibility of mosquitoes. The plexiglass was secured to a plastic sample rack (24.5 cm × 12.5 cm × 7.0 cm) to provide the appropriate height for manipulation of mosquitoes (Nalgene, ThermoFisher Scientific, Rochester, NY) inside an enclosed glove box. Autoclave tape (Propper Manufacturing Co., Long Island City, NY) was placed sticky-side up along the top of the salivation device in order to secure the live mosquitoes. Immersion oil (0.01 ml) (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) was added to capillary tubes (75 mm, 70-µl capacity; Fisher Scientific, Pittsburg, PA) with the use of a sterile pipette tip (Rainin, Woburn, MA) inserted into the end opposite the oil.

Fig. 1.

Collection of saliva from a mosquito into a capillary tube. (A) Close-up of a single Culex p. quinquefasciatus salivating into a capillary tube containing immersion oil. (B) Saliva from multiple mosquitoes can be collected at one time. (I) Mosquito affixed to sticky tape. (II) Plexiglass surface on top of white laboratory bench paper. (III) Capillary tube into which the proboscis is inserted and saliva is collected.

At the conclusion of the 13–14-day IP, mosquitoes were immobilized with cold and wings and legs were removed as described previously (Richards et al. 2009). Live mosquito bodies were then placed onto the sticky side of the tape affixed to the salivation device so that the proboscis extended beyond the tape (Figs. 1A, 1B). Gentle pressure was applied to secure each live mosquito to the tape. Separate capillary tubes containing oil were laid flat on top of the salivation device and gently placed over each mosquito’s proboscis; this was repeated for 25 mosquitoes per salivation device. Mosquitoes were allowed to salivate for approximately 30–45 min, after which the capillary tubes were removed and the contents were expelled via pipettor into tubes containing 1 ml BA-1 diluent. Mosquitoes were visually verified to be alive at the conclusion of the 45-min salivation period by the occurrence of movement. If the mosquito did not exhibit movement upon completion of the saliva collection period, then the mosquito was removed from the study. Once saliva was collected, each mosquito body was placed in a separate tube containing 1 ml BA-1 diluent and stored at −80°C until processing for WNV.

To test for the presence of WNV in mosquito bodies, legs, and saliva, methods described elsewhere were used (Richards et al. 2007, 2009). Briefly, samples were homogenized at 25 Hz for 3 min (TissueLyser; Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA) and centrifuged at 3,148 × g for 4 min at 4°C. Viral RNA was extracted with the use of the MagNA Pure LC System and Total Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). The amount of viral RNA in each sample was quantified with the use of the Superscript III One-Step Quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for quantitative real-time TaqMan RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) (Lanciotti et al. 2000) by the LightCycler® 480 system (Roche).

The method reported here uses a larger volume of oil (0.01 ml) than most previous studies (0.003–0.01 ml of collection media) (Aitken 1977, Cornel and Jupp 1989, Colton et al. 2005, Mores et al. 2007), which makes it easier to expel the oil. By inserting a pipette tip into the end of the capillary tube opposite the oil, it is possible to push air through the tube and expel the oil into a sample tube containing diluent. The modified capillary tube method with immersion oil was used to assess WNV transmission in Cx. p. quinquefasciatus directly (Table 1). The results show that 27–33% of mosquitoes fed WNV-infected blood meals transmitted WNV in their saliva, even though 98–100% of infected females showed disseminated infection with virus in the legs. Our results support that measuring disseminated infection to the legs is not always a good indicator of transmission. These results were consistent with other studies that examined WNV saliva infection in Cx. p. quinquefasciatus (Vanlandingham et al. 2004, Colton et al. 2005).

Table 1.

The mean titers ± SE (logs plaque-forming units West Nile virus [WNV]/ml equivalents) and rates of infection, dissemination, and transmission for Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus infected with WNV and held for 13–14-day incubation periods at 28°C.

| Incubation period |

WNV dose |

No. tested |

No. body infection (%) |

No. leg infection (%) |

No. saliva infection (%) |

Body Titer |

Leg titer |

Saliva titer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13 | 7.1 ± 0.01 | 24 | 24 (100) | 19 (79) | 3 (13) | 6.6 ± 0.1 | 4.2 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.4 |

| 14 | 6.9 ± 0.1 | 100 | 100 (100) | 99 (99) | 29 (29) | 6.8 ± 0.1 | 4.8 ± 0.1 | 2.6 ± 0.2 |

Other methods of saliva collection, such as droplet feeding, show virus transmission rates consistent with the capillary tube method (Cornel and Jupp 1989). However, the droplet method is cumbersome, as it requires placing each mosquito singly into a cage and observing the duration of feeding. Conversely, the capillary tube method allows for a controlled period of forced salivation to ensure that variations in virus titers are not affected by different feeding durations. The length and diameter of the capillary tube are also important factors. The capillary tube dimensions specified here allow for easy placement over the mosquito proboscis and expulsion of the immersion oil upon completion of the salivation period. Even though variations on these methods have been reported previously, most reports are based on small sample sizes (n < 60) and have been done for a limited number of viruses and mosquito species. The methods used here allow for efficient manipulation of up to 25 mosquitoes at a time. Consequently, this device would be useful for large-scale experiments and allow a single researcher to assess transmission in 75–100 mosquitoes per day.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Walter J. Tabachnick, C. Roxanne Connelly, and 2 anonymous reviewers for critically reviewing earlier versions of the manuscript. We also thank James Newman and Gregg Ross for their photographic expertise. This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant AI-42164) to Cynthia L. Lord, Jonathan F. Day, and Walter J. Tabachnick. Sheri Anderson was supported by a University of Florida Graduate Alumni Award.

REFERENCES CITED

- Aitken THG. An in vitro feeding technique for artificially demonstrating virus transmission by mosquitoes. Mosq News. 1977;37:130–133. [Google Scholar]

- Colton L, Biggerstaff BJ, Johnson A, Nasci RS. Quantification of West Nile virus in vector mosquito saliva. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2005;21:49–53. doi: 10.2987/8756-971X(2005)21[49:QOWNVI]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornel AJ, Jupp PG. Comparison of three methods for determining transmission rates in vector competence studies with Culex univittatus and West Nile and Sindbis viruses. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 1989;5:70–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubler DJ, Rosen L. A simple technique for demonstrating transmission of dengue virus by mosquitoes without the use of vertebrate hosts. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1976;22:146–150. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1976.25.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurlbut HS. Mosquito salivation and virus transmission. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1966;15:989–993. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1966.15.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanciotti RS, Kerst AJ, Nasci RS, Godsey MS, Mitchell CJ, Savage HM, Komar N, Panella NA, Allen BC, Volpe KE, Davis BS, Roehrig JT. Rapid detection of West Nile virus from human clinical specimens, field collected mosquitoes, and avian samples by a TaqMan reverse transcriptase-PCR assay. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:4066–4071. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.11.4066-4071.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mores CN, Turell MJ, Dohm DJ, Blow JA, Carranza MT, Quintana M. Experimental transmission of West Nile virus by Culex nigripalpus from Honduras. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2007;7:279–284. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2006.0557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards SL, Lord CC, Pesko KA, Tabachnick WJ. Environmental and biological factors influence Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus Say (Diptera: Culicidae) vector competence for Saint Louis encephalitis virus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;81:264–272. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards SL, Mores CN, Lord CC, Tabachnick WJ. Impact of extrinsic incubation temperature and virus exposure in vector competence of Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus Say (Diptera: Culicidae) for West Nile virus. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2007;7:626–636. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2007.0101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DR, Carrara AS, Aguilar PV, Weaver SC. Evaluation of methods to assess transmission potential of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus by mosquitoes and estimation of saliva titers. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;73:33–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanlandingham DL, Schneider BS, Klinger K, Fair J, Beasley D, Huang J, Hamilton P, Higgs S. Real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction quantification of West Nile virus transmitted by Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71:120–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]