Abstract

Objective

Evaluate moderators and mediators of brief alcohol interventions conducted in the Emergency Department.

Methods

Patients (18–24 years; N = 172) in an Emergency Department received a motivational interview with personalized feedback (MI) or feedback only (FO), with 1- and 3-month booster sessions and 6- and 12-month follow ups. Gender, alcohol status/severity group (ALC+ Only, AUDIT+ Only, ALC+/AUDIT+), attribution of alcohol in the medical event, aversiveness of the event, perceived seriousness of the event, and baseline readiness to change alcohol use were evaluated as moderators of intervention efficacy. Readiness to change also was evaluated as a mediator of intervention efficacy, as were perceived risks/benefits of alcohol use, self-efficacy, and alcohol treatment seeking.

Results

Alcohol status, attribution, and readiness moderated intervention effects such that patients who had not been drinking prior to their medical event, those who had low or medium attribution for alcohol in the event, and those who had low or medium readiness to change showed lower alcohol use 12 months after receiving MI compared to FO. In the AUDIT+ Only group those who received MI showed lower rates of alcohol-related injury at follow up than those who received FO. Patients who had been drinking prior to their precipitating event did not show different outcomes in the two interventions, regardless of AUDIT status. Gender did not moderate intervention efficacy and no significant mediation was found.

Conclusions

Findings may help practitioners target patients for whom brief interventions will be most effective. More research is needed to understand how brief interventions transmit their effects.

Keywords: Alcohol, Brief Intervention, Emergency Room

Alcohol is one of the primary causes of injuries treated in trauma centers (1), and Emergency Department (ED) patients are up to three times more likely to report heavy drinking and negative consequences of drinking than patients in primary care settings (2). Males and younger patients are more likely to have been drinking prior to treatment in an ED (3), and patients who are admitted to a trauma center with positive toxicology findings have twice the subsequent injury mortality rates than other patients (4).

Use of early, brief interventions may prevent the development of more severe cases of alcohol problems (5), and may reduce the risk of future health problems or injury (6–8). The importance of treating alcohol problems among ED and trauma center patients is reflected in national recommendations (9), and a recent mandate that requires all trauma centers to provide screening and brief intervention services for alcohol problems (10). Motivational Interviewing (MI) (11) reduces drinking and/or associated problems with patients in EDs or trauma centers, with effects lasting up to 12 months (6, 12–14) but there remains a need to specify for whom MI is most effective, and to understand how MI transmits its effects (15, 16).

Moderators of Intervention Efficacy

Despite strong evidence of efficacy (7), some brief intervention trials with ED patients have found intervention effects on alcohol use but not alcohol-related consequences (14, 17), and others have found the opposite (12, 13). Identifying characteristics that are associated with better response to brief interventions could explain these inconsistencies, improve intervention efficiency, inform triaging, and enhance dissemination of brief intervention approaches.

Gender

There is a basis for investigating gender as a moderator of ED brief intervention efficacy. Alcohol abuse may be more stigmatized for women than for men, and women as a result are less likely than men to seek help from traditional treatment services (18–20). In addition, waiting for treatment in an ED can be stressful (21) and women are more likely to respond to stress by seeking support from others (22) so may be differentially responsive to provider-initiated interventions in medical settings. Some brief intervention studies have found that women are more responsive to intervention than men (or benefit from a less intensive intervention) (6, 23–26) whereas others report effects for men but not for women (27, 28). The inconsistent findings and the clinical implications of gender differences support further investigation of gender as a moderator of brief intervention efficacy.

Salience of the ED event

Salience, or the relevance of the event to the patient, may be an important predictor of change following such events, and may interact with intervention approaches. Salience can be conceptualized as a function of both the objective nature of the event (i.e., whether the patient had been drinking prior to the injury), and the patient’s beliefs about and affective reactions to the event. A patient treated for an injury following drinking may be more likely to benefit from intervention because it is perceived to be relevant. On the other hand, such patients may initiate change without the need for intervention, consistent with the Health Belief Model that posits that internal or external cues to action may stimulate the change process (29). Indeed, patients seen for alcohol-related events reduce their alcohol use without intervention for 3–4 months after their ED visit (30). Whether alcohol status in the event (as one putative element of salience) interacts with intervention has not been completely evaluated.

Patient beliefs about the role of alcohol in the event, the perceived seriousness of the event, and their emotional reaction to the event are other aspects of salience that may reflect a sense of vulnerability (31) and that subsequently may prompt change and/or interact with intervention. Half of ED patients who drank prior to their injury attribute a causal association between alcohol and their injury (32), and such causal attributions are associated with motivation to change alcohol use (33, 34). Walton et al. (35) evaluated alcohol attribution as a moderator of brief alcohol intervention and found that ED patients who attributed their injury to alcohol reduced their alcohol use to a greater degree when they received advice from a provider than when they were provided an informational booklet. Patients who did not attribute their injury to alcohol did not show this difference in intervention outcome, indicating that patients who attribute their injury to alcohol use may be best able to benefit from more intensive interventions. Perceived seriousness and aversiveness of the event also have been empirically associated with greater motivation to change alcohol use (34, 36), but have not been evaluated as moderators of intervention effects.

Alcohol use severity

Patients with different levels of alcohol severity may respond differently to intervention. Among adolescent ED patients being treated for an alcohol-related incident, Spirito et al. (17) found those with high alcohol use severity reduced drinking following brief MI whereas those with low severity showed little change. Dauer and colleagues (37), however, found severity did not moderate treatment efficacy among adult alcohol-positive motor vehicle crash patients. Finally, Gentilello et al. (6) reported that MI benefitted trauma patients with mild-to-moderate alcohol problems but not those with more or less severe problems, including a subgroup of alcohol-positive patients with low alcohol problem severity. This highlights the potentially unique information to be derived from examining alcohol status and alcohol severity as distinct but overlapping constructs.

Readiness to change

MI may be particularly suited for those low in motivation (38), and several studies have found MI to outperform other active interventions with low-readiness participants (39–41), although others have found no evidence of moderation (12, 42). Readiness is important to study as a moderator of intervention efficacy, given its theoretical importance and potential utility in identifying patients for whom intervention may be most effective.

Mediators of Behavior Change in Motivational Interviewing

A mediator is a variable temporally intervening between treatment and a measured outcome that fully or partially explains the relationship (43). Although a number of candidates have been proposed to account for how MI exerts its therapeutic effects on behavior change (11), there is a lack of consistent data to support their roles as mediators (15). Furthermore, a variety of methods exist to statistically test for mediation (i.e., testing of the paths from intervention to mediator and from mediator to outcome), but most studies have only examined individual paths. A recent review of MI mechanisms analyzed 19 studies; only two included full mediation analyses (44). The authors noted the paucity of mediation analyses in the MI literature, and recommended secondary analysis of existing data to evaluate possible mechanisms of change. Identifying how MI works could facilitate streamlining and could improve brief interventions in medical settings, where time is often very limited.

Readiness to change

A number of studies with substance abusers have examined whether MI increases readiness to change, with mixed results. Several suggest MI may increase readiness among substance abuse patients more than other approaches (45–47), but an equal number suggest that MI is no more effective at increasing readiness than other treatments (48–50). Importantly, none of the studies that found MI increased readiness formally tested for mediation, so to date the effectiveness of MI cannot be attributed to increased readiness (51).

Perceived risks and benefits

One of the MI principles is to develop discrepancy, which involves heightening awareness of the incompatibility of alcohol use with broader life goals and values. In practice this involves encouraging a client to examine his or her beliefs about the positive and negative consequences of drinking in order to shift client perception toward a decision to change (52). Two studies have found that MI leads to greater changes in client perception of the risks and benefits of substance use than comparison conditions (41, 45), suggesting that a shift in perceived risks/benefits may be an important mediator of MI effectiveness. A recent review of mechanisms of change found that among therapeutic techniques used in MI, a decisional balance exercise (examining risks/benefits) showed the strongest association to better outcomes (44). However, formal mediation analysis of this construct has not been conducted.

Self-efficacy

Enhancing client self-efficacy is a central component of MI (11). Although one study found that MI led to higher levels of self-efficacy than a comparison condition (53), others have found no differences between MI and other conditions (41, 54), and another found less of an increase in self-efficacy following MI in contrast to a comparison condition (45). This pattern of findings suggests that increased self-efficacy as a proximal outcome may not be unique to MI (55), but self-efficacy has not been well evaluated in studies of MI for alcohol use.

Treatment seeking

MI is designed to promote engagement in further treatment, but while some studies show MI results in greater treatment seeking (56–59), others show no effect (12, 60). In the only study to examine treatment seeking as a mediator of MI efficacy, Connors and colleagues (61) found that MI led to participation in more treatment than a control condition, and greater participation partially mediated the effect of MI on heavy drinking outcomes.

The first goal of the current study was to evaluate possible moderators of intervention efficacy including gender, ED event salience, alcohol use severity, and pretreatment readiness to change. We expected that men, participants low in salience, and low in readiness to change alcohol use would show greater differences between the intervention conditions than respective comparison groups. Rather than evaluating alcohol (ALC) status and severity separately, we initially categorized patients into three nonoverlapping groups of severity and alcohol status (i.e., ALC+ Only, AUDIT+ Only, ALC+/AUDIT+). This allowed us to evaluate the distinct response to intervention approaches of patients with different profiles. To date, evaluations of moderators in ED interventions have not explicitly analyzed these alcohol status and severity profiles (6, 13, 17, 35, 37). Such information may guide clinical decisions about the allocation of intervention resources for individuals who are identified in the ED as being at risk.

Our second goal was to explore putative mediators of MI’s effect on alcohol consumption. We expected that readiness to change, perceived risks/benefits of alcohol use, self-efficacy, and treatment seeking would mediate effects of MI. Data were from a randomized controlled trial of MI vs. personalized feedback only (FO) in the ED (14). The MI group reduced alcohol use significantly more than the FO group 6 and 12 months after the intervention, but did not show significant changes in alcohol problems or alcohol-related injury.

Method

Participants

Patients ages 18–24 treated in the ED of a Level 1 trauma center in Rhode Island were invited to participate in the study between 2000 and 2003 if they: (a) had a blood alcohol concentration (BAC) greater than .010% according to a biochemical test or reported drinking alcohol in the 6 hours prior to the event that caused their visit (n = 156) or (b) scored 8 or higher on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (62) (n = 59). Patients who did not speak English, had a self-inflicted injury, or were in police custody were excluded.

Procedures

All procedures were approved by the university and hospital Institutional Review Boards and all participants gave written informed consent. Initial BAC tests were administered to all participants and an alcohol breath test was administered prior to conducting the baseline assessment. Counselors administered baseline assessments using a laptop computer, after which patients were randomly assigned to receive either one session of MI with personalized feedback (30–45 minutes) or a personalized feedback written report only with minimal counselor contact. Participants received telephone booster sessions at 1 and 3 months and completed follow-up assessments 6 and 12 months after intervention. See Monti et al. (14) for additional details.1

Measures

Dependent measures

The Timeline Followback (TLFB) (63) was used to measure alcohol use in the 30 days prior to the ED visit and the 12-month follow up. Number of days drinking, number of heavy drinking days (≥5 drinks for men, ≥4 for women), and average number of drinks per week were calculated. These three variables showed similar results in the original study so were standardized and averaged to create a composite variable of alcohol use at baseline and follow up. Alcohol-related consequences were measured with the Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI; α = .91) (64), using a 6-month window at each follow up, combined to reflect the past year. A count of past-year alcohol-related injuries (65) was collected at baseline and follow up.

Moderators

The alcohol status/severity categories were derived by combining the patient’s alcohol status upon entry to the ED (i.e., alcohol-positive or alcohol-negative) with whether the patient scored 8 or higher on the AUDIT (i.e., low or high severity). Three groups resulted: 1) an alcohol-positive/low-severity group (ALC+ Only, n = 57); 2) an alcohol-negative/high-severity group (AUDIT+ Only, n = 59); and 3) an alcohol-positive/high-severity group (ALC+/AUDIT+, n = 99).

Event attribution, aversiveness, and perceived seriousness were measured using the Injury/Event Experience scale (34). The attribution item was “To what extent do you believe your alcohol consumption was responsible for this injury or event?” Aversiveness was measured with a mean of three items (α= .64) querying how upsetting and how frightening the event was and how much pain/harm it had caused. Perceived seriousness was measured using the item “How serious do you think your medical condition is?” Items were scored on a 7-point scale from 1 (not at all) to 7 (totally or extremely). Readiness to change was measured using a Readiness Ruler (11) that asks, “How ready are you to make a change in your drinking?” Response options range from 1 (not ready) to 10 (trying).

Mediators

The Readiness Ruler was readministered post-intervention. Perceived risks and benefits of drinking were measured with eight items from the Heavy Drinking and Illicit Drug Use subscales of the Cognitive Appraisal of Risky Events (66) at baseline and 6 months. Participants were asked, “How likely is it that you would experience some negative/positive consequence if you engaged in these activities?” Items were scored on a scale of 1 (not at all likely) to 7 (extremely likely) and summed, and a risk-benefit difference score was calculated at baseline and follow up. Self-efficacy for alcohol-related situations was measured with the Brief Situational Confidence Questionnaire (67) administered at baseline and 6 months. Participants indicated on a scale from 0–100% how confident they were that they would be able to resist drinking heavily across seven2 high-risk situations. Alcohol-related treatment seeking (five items measuring counseling, treatment and self-help) was measured at 6 months and dichotomized (treatment seeking vs. none).

Data Analyses

Moderation

For categorical moderators (gender and alcohol status/severity groups) and continuous dependent variables (alcohol use z-score composite and RAPI score), analyses of variance were conducted with the moderator and intervention condition as factors and baseline level of the dependent variable as a covariate. To evaluate differences within each alcohol status/severity group, planned comparisons were conducted between intervention conditions. For effects of the categorical moderators on the dichotomously coded alcohol-related injury, separate chi-square analyses were conducted for men and women and for each alcohol status/severity group, with intervention condition and alcohol-related injury as the factors.

For continuous moderators (attribution, aversiveness, perceived seriousness, and baseline readiness) and continuous dependent variables (alcohol use, RAPI score), regression analysis was used. Moderators were centered at the mean, and a multivariate regression tested the main effects of intervention (MI vs. FO), moderator, and the interaction of intervention and moderator for each outcome (68). Significant interactions were followed by the derivation of high and low moderator groups (±1 SD from the baseline mean) for tests of simple slopes within (high, medium, low) moderator group (69–71). Analyses of the moderation effect of continuous moderators on the dichotomized injury outcome variable used the same approach within a logistic regression framework. For regression analyses, we had 80% power to detect an R2 of .07 for the total regression, and to detect an sr2 of .045 for the moderation term, so we had sufficient power to detect small effects.

Mediation

For readiness, perceived risk/benefit, and self-efficacy, change scores were calculated by subtracting the baseline from the post-intervention or 6-month score. Use of a multiple mediation model allowed us to determine whether the set of four theory-driven variables mediated the effect of MI on outcomes and the extent to which individual variables mediated the effect conditional on the presence of other mediators in the model. This approach reduces decision errors, enhances power, and reduces the probability of Type 1 errors (72). We first calculated the direct effect of intervention (MI vs. FO) on the 12-month composite alcohol use outcome. The indirect effect of intervention on outcome via each individual mediator is represented as the product of the intervention→mediator path (a) and the mediator→outcome path (b). The impact of all mediators included in the model is expressed as the total indirect effect of intervention on outcome. Because it is possible to find significant indirect effects in the presence of a nonsignificant total indirect effect (72) we also tested hypotheses regarding individual mediators in the context of the multiple mediator model. An SPSS macro (73) with 1,000 bootstrap resamples was used to obtain lower and upper limits of a 95% confidence interval (CI) for each indirect effect.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Of the 215 patients enrolled, 172 (80%) completed 12-month follow ups. Attrition was not related to intervention group or to any of the outcome, moderator or mediator variables. Results are presented for participants who completed follow up.3 The sample was 64.5% male (n = 111), with an average age of 20.5 years (SD = 1.8). Self-reported race/ethnicity was 69.2% White, 11.0% Hispanic, 5.2% Black, 1.7% Asian, 1.2% Native American, and 11.6% Other. Average years of education was 12.4 (SD = 1.8). Average BAC in the ED (ALC+ participants only) was .104% (SD = .081) and average breath level at baseline assessment was .037% (SD = .054). Baseline and follow-up values for the moderator, mediator and outcome variables are in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic, moderator, mediator, and outcome variables in the two intervention groups at baseline and 12 month follow up

| MI (N = 82) | FO (N = 90) | |

|---|---|---|

| M(SD) or n(%) | M(SD) or n(%) | |

| Male | 54 (65.9%) | 57 (63.3%) |

| Age | 20.6 (1.8) | 20.4 (1.9) |

| BAC in ED | .084 (.082) | .088 (.085) |

| Moderator Variables | ||

| Alcohol-Positive | 57 (69.5%) | 71 (78.9%) |

| AUDIT-Positive | 68 (82.9%) | 60 (66.7%) |

| Attribution about alcohol in the medical event | 2.8 (2.4) | 2.8 (2.3) |

| Aversiveness of the medical event | 4.4 (1.7) | 4.5 (1.7) |

| Perceived seriousness of the medical event | 2.9 (1.6) | 3.2 (1.7) |

| Readiness to change alcohol use | ||

| Baseline | 5.4 (2.8) | 5.6 (2.5) |

| Post-intervention | 6.3 (2.8) | 5.7 (2.5) |

| Mediator Variables | ||

| Perceived risk of drinking | ||

| Baseline | 40.3 (11.7) | 39.2 (11.7) |

| 6 months | 38.2 (13.0) | 36.9 (12.4) |

| Perceived benefit of drinking | ||

| Baseline | 15.2 (7.5) | 17.4 (9.3) |

| 6 months | 16.1 (8.4) | 17.0 (7.6) |

| Self-efficacy to resist drinking | ||

| Baseline | 71.1 (23.4) | 66.5 (21.0) |

| 6 months | 75.8 (22.4) | 73.7 (20.9) |

| Outcome Variables | ||

| Number of drinking days, past month | ||

| Baseline | 8.3 (6.5) | 7.7 (6.5) |

| 12 months | 4.4 (5.6) | 6.4 (6.4) |

| Number of heavy drinking days, past month | ||

| Baseline | 5.5 (6.0) | 4.3 (4.7) |

| 12 months | 2.6 (4.6) | 3.5 (4.3) |

| Ave. number of drinks per week, past month | ||

| Baseline | 13.2 (12.2) | 11.3 (11.6) |

| 12 months | 5.9 (8.4) | 8.9 (10.3) |

| RAPI Total | ||

| 12 monthsa | 29.3 (25.3) | 25.4 (20.3) |

| Alcohol-related injury | ||

| Baseline | 53 (76.8%) | 62 (78.5%) |

| 12-monthsa | 31 (44.9%) | 35 (44.3%) |

Note. AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. BAC = Blood Alcohol Concentration. ED = Emergency Department. FO = Feedback Only intervention group. MI = Motivational Interview intervention group. RAPI = Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index.

Follow-up values are combined from multiple follow-up assessments to reflect past year, so sample sizes vary due to missing data.

Moderation Findings

Some of the moderators were significantly correlated; sex (male = 0) was correlated with AUDIT status, r = −.15, p < .05, and aversiveness, r = .24, p < .01. ALC status was correlated with attribution, r = .46, p < .001, and aversiveness, r = .16, p < .05. Aversiveness also was correlated with perceived seriousness, r = .56, p < .001, and readiness, r = .35, p < .001.

Gender

Main effects for gender were found on 12-month alcohol consumption, F(1,167) = 4.58, p < .05, and alcohol problems, F(1,145) = 4.14, p < .05 (with men showing higher scores for both), but not for alcohol-related injury. No interactions were found between intervention condition and gender for any outcome. The effect sizes for these analyses were (Cohen’s f) < .10, and (Cramér’s ϕ) < .10, reflecting very small effect sizes, and indicating the interventions were not differentially effective for men and women.

Alcohol-positive/Alcohol-severity combination

Baseline data for the three groups are presented in Table 2, and moderation analyses are in Table 3. There was a significant interaction between group and intervention condition on 12-month alcohol consumption, F(2,165) = 3.88, p < .05; contrasts indicated that among patients in the AUDIT+ Only group, those who received MI had significantly lower alcohol use than those who received FO. AUDIT+ Only patients who received MI reported an average of 5.1 drinks per week at 12-month follow up (adjusted for baseline values) compared to 16.7 drinks per week for the FO group (a decrease of 10.4 vs. 3.7 drinks weekly for MI and FO, respectively). Alcohol use in the two other groups was not significantly different between intervention groups, although the between-groups effect size for the ALC+ Only group was in the medium range (Cohen’s d = −0.52).

Table 2.

Alcohol-positive/Alcohol-severity groups characteristics at baseline

| ALC+ Only (n = 44) | AUDIT+ Only (n = 44) | ALC+/AUDIT+ (n = 84) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M(SD) or n(%) | M(SD) or n(%) | M(SD) or n(%) | Statistic | |

| Male | 23 (52.3%) | 27 (61.4%) | 67 (72.6%) | χ2(2) = 5.48 |

| Age | 20.5 (2.0) | 20.6 (1.7) | 20.4 (1.8) | F(2,169) = 0.39 |

| BAC in ED | .086 (.077)a | .000b | .124 (.077)c | F(2,151) = 39.14*** |

| AUDIT Total | 4.4 (1.6)a | 12.1 (3.9)b | 14.0 (6.1)c | F(2,169) = 60.23*** |

| Attribution about alcohol in the medical event | 3.1 (2.5)a | 1.1 (0.6)b | 4.0 (2.4)c | F(2,169) = 26.12*** |

| Aversiveness of the medical event | 4.8 (1.7) | 4.0 (1.5) | 4.5 (1.7) | F(2,169) = 2.65 |

| Perceived seriousness of the medical event | 3.2 (1.7) | 3.0 (1.6) | 3.0 (1.8) | F(2,115) = 0.20 |

| Readiness to change alcohol use | 5.5 (2.3) | 4.9 (2.6) | 5.9 (2.8) | F(2,115) = 1.39 |

| No. drinking days, past month | 4.1 (2.6)a | 9.4 (6.7)b | 9.3 (7.1)b | F(2,169) = 11.76*** |

| RAPI Total | 8.4 (6.3)a | 21.9 (15.4)b | 19.3 (15.8)b | F(2,169) = 12.39*** |

| Alcohol-related injury | 34 (77.3%)a,b | 28 (63.6%)a | 74 (88.1%)b | χ2(2) = 10.55** |

Note. ALC = Alcohol; reflects participants who were alcohol-positive by self-report or biochemical test. AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; reflects participants who scored 8 or higher on the AUDIT. BAC = Blood Alcohol Concentration. ED = Emergency Department. RAPI = Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index. Frequency of drinking is presented for descriptive purposes; significance values of other alcohol consumption variables and the standardized composite were identical. Different superscripts indicate groups differ significantly.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Table 3.

Intervention group 12-month outcomes for the alcohol status/severity groups

| ALC+ Only (n = 44) | AUDIT+ Only (n = 44) | ALC+/AUDIT+ (n = 84) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| M(SD) or n(%) | M(SD) or n(%) | M(SD) or n(%) | |

| Alcohol use | |||

| MI | −0.63 (1.0) | −0.97 (1.6) | −0.16 (2.4) |

| FO | −0.20 (0.7) | 1.37 (2.9) | 0.35 (2.3) |

| Contrasts between treatment groups | F(1,41) = 3.19 | F(1,41) = 14.71*** | F(1,81) = 1.66 |

| Between treatment groups effect size | 0.52 | 1.05 | 0.21 |

| RAPI Total | |||

| MI | 24.39 (16.5) | 27.61 (21.5) | 26.84 (28.9) |

| FO | 23.10 (13.6) | 37.71 (20.7) | 25.50 (19.6) |

| Contrasts between treatment groups | F(1,36) = 0.03 | F(1,34) = 3.18 | F(1,71) = 0.08 |

| Between treatment groups effect size | −0.09 | 0.47 | −0.05 |

| Alcohol-related injury | |||

| MI | 3 (30.0%) | 10 (45.5%) | 18 (48.6%) |

| FO | 9 (31.0%) | 11 (78.6%) | 15 (41.7%) |

| Contrasts between treatment groups | χ2(1) = 0.00 | χ2(1) = 3.86* | χ2(1) = 0.36 |

| Between treatment groups effect size | 0.02 | 0.69 | −0.14 |

Note. ALC = Alcohol; reflects participants who were alcohol-positive by self-report or biochemical test. AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; reflects participants who scored 8 or higher on the AUDIT. BAC = Blood Alcohol Concentration. FO = Feedback Only intervention group. MI = Motivational Interview intervention group. RAPI = Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index. Alcohol use is the standardized composite of number of days drinking, number of heavy drinking days, and average number of drinks per week (all past month). Means are adjusted for baseline values. Effect sizes are Cohen’s d and use the pooled standard deviation. A positive effect size indicates MI had a better outcome than FO.

p < .05.

p < .001.

The group by intervention effect for the RAPI was not significant, F(2,143) = 1.46, nor were planned comparisons, but the effect size in the AUDIT+ Only group was in the medium range (Cohen’s d = −0.47). For the alcohol-related injury outcome, the only group to show differential outcome was the AUDIT+ Only group, with patients who received MI showing lower rates of injury at follow up than those who received FO (see Table 3).

Supplementary analyses of ALC+ vs. ALC−

Given the significant intervention group differences found in the AUDIT+ Only group, and the lack of intervention group differences in the two ALC+ groups, we conducted another set of analyses to evaluate the independent importance of ALC status by comparing ALC+ participants to ALC− participants. This combination collapsed the ALC+ Only and the ALC+/AUDIT+ groups into one group (ALC+) and renamed the AUDIT+ Only group as ALC−. An ANCOVA with ALC status and intervention group as factors and 12-month alcohol use as the dependent variable (and baseline use as a covariate) found an intervention by group interaction, F(1,167) = 7.91, p < .01. Simple effects tests indicated that ALC− patients who received MI showed lower alcohol use at 12 months than ALC− patients who received FO, t(42) = 4.03, p < .001. In the ALC+ group, there were no differences between MI and FO in alcohol use outcomes. The intervention by group interaction on the RAPI measure was not significant, F(1,145) = 3.21, ns. For alcohol-related injuries, the analysis for the ALC− group is identical to the AUDIT+ Only column in Table 3 and reflects significant differences favoring MI in this group. The ALC+ group did not show differences between intervention conditions on alcohol-related injury at 12 months (MI: 44.7%; FO: 36.9%; χ2[1, N = 112] = .68, ns).4

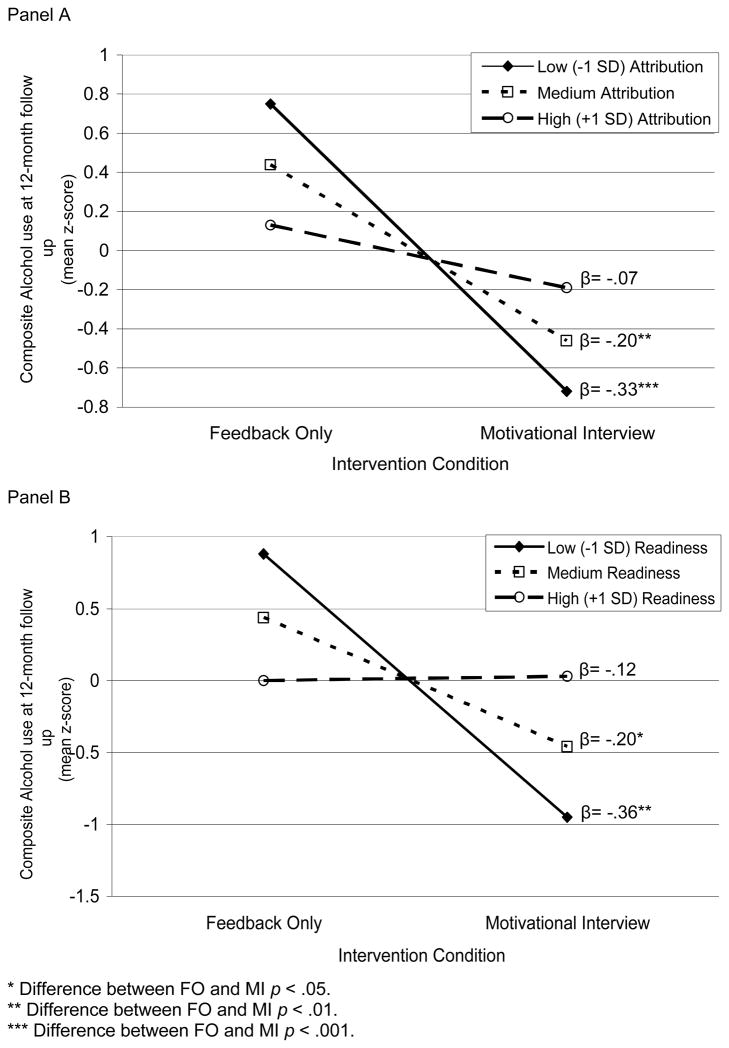

Attribution of alcohol

When the 12-month alcohol use composite was regressed on baseline alcohol use, intervention group, attribution of alcohol in the injury, and the product of intervention group and attribution, the total model accounted for 32.1% of the variance in alcohol use at follow up, F(4,167) = 19.70, p < .001. The attribution by intervention group interaction was significant (β = .18, p < .05, sr2 = .02). When the attribution groups were compared between intervention groups, significant simple slopes were found for low and medium attribution (see Figure 1), but not for high attribution.

Figure 1.

Attribution of alcohol in the ED event and readiness to change alcohol use as moderators of intervention effects on 12-month alcohol use

With the RAPI as the dependent variable, the total model accounted for 42.6% of the variance, and the overall model was significant, F(4,145) = 26.88, p < .001, but the interaction term was not significant (β = .00) so no further analyses were conducted. When 12-month alcohol-related injury was regressed on attribution, with baseline alcohol injury, intervention group, and the product of intervention group and attribution included, the model was not significant, χ2(3, N = 148) = 2.31, effect size (Cramér’s ϕ) = .13, indicating attribution of alcohol did not moderate intervention effects on subsequent alcohol injury.

Aversiveness of the medical event

For the 12-month alcohol use composite, the total model accounted for 30.8% of the variance in alcohol use at follow up, F(4,167) = 18.58, p < .001, but the interaction term was not significant (β = .06). With RAPI, the total model accounted for 43.0% of the variance, and the model was significant, F(4,145) = 27.35, p < .001, but the interaction term was not (β = .07). With 12-month alcohol injury as the dependent variable, the model was not significant, χ2(3, N = 148) = 1.71, effect size (Cramér’s ϕ) = .14, indicating aversiveness did not moderate intervention effects on any 12-month outcome.

Perceived seriousness of the medical event

For the 12-month alcohol use composite, the total model accounted for 31.4% of the variance in alcohol use at follow up, F(4,113) = 12.91, p < .001. The interaction term was not significant (β = −.06). With the RAPI, the total model accounted for 42.7% of the variance, and the model was significant, F(4,101) = 18.85, p < .001, but the interaction term was not (β = .07). With 12-month alcohol injury, the model was not significant, χ2(3, N = 104) = 5.04, effect size (Cramér’s ϕ) = .22, indicating perceived seriousness did not moderate intervention effects on any of the outcomes.

Baseline readiness to change

For the 12-month alcohol use composite, the total model accounted for 26.6% of the variance in alcohol use at 12 months, F(4,113) = 10.26, p < .001. The interaction term was significant (β = .32, p < .01), and accounted for 4.8% of variance, indicating that the effect of intervention on drinking varied by baseline readiness. Tests of significance of intervention coefficients showed that the impact of MI (over FO) on alcohol use was significant at medium and low levels of readiness but not at high readiness (see Figure 1). The linear and logit analyses on the RAPI and alcohol-related injury outcomes were not significant, F(4,114) = .41 andχ2(3, N = 116) = .96, respectively.

Multivariate analysis

To examine whether ALC status or alcohol attribution was a more meaningful moderator, we conducted a regression with baseline alcohol use, attribution, ALC group (+/−), and intervention condition entered on the first step, and the products of intervention condition with attribution, and intervention with ALC group entered on the second. The model accounted for 31.5% of the variance in alcohol outcome, F(6,171) = 14.09, p < .001, with acceptable collinearity (tolerance = .20 – .44; VIF = 2.3 – 5.0). The first step showed main effects for baseline alcohol use (β = .53, p < .001) and intervention condition (β = −.20, p < .01). At the second step, baseline alcohol use and intervention remained significant, and ALC group interacted with intervention condition (β = .33, p < .05, sr2= .03), but the interaction between attribution and intervention was not significant (β = .08), indicating that ALC group contributed independently to differential intervention efficacy.

Finally, to establish the independence among the three moderator effects, attribution, ALC group status, readiness, intervention and the moderator/intervention group interactions were included in a regression. The total model accounted for 37.3% of the variance, F(8,117) = 8.11, p < .001, with acceptable collinearity (tolerance = .20 – .45; VIF = 2.2 – 5.1). The first step showed an effect for intervention (β = − .20, p < .05). On the second step, intervention remained significant and the interaction term of readiness and intervention condition also was significant (β = .27, p < .05, sr2 = .05); the other interaction terms were not.

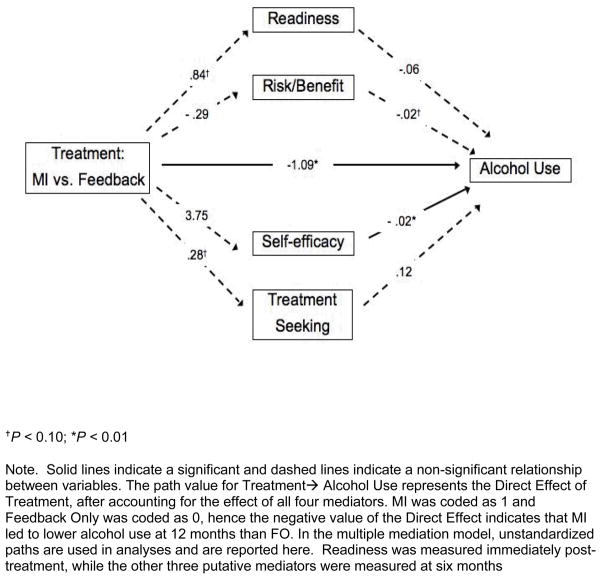

Mediation Findings

Descriptive statistics for the mediator measures are presented in Table 1. The total indirect effect of the set of four mediators yielded a bootstrapped point estimate of −.08. The 95% BCa bootstrap CI of −.48 to .28 indicates that the difference between the total and direct effect of intervention on outcome is not different from zero. Hence, taken as a set, readiness, risk/benefit, self-efficacy, and treatment seeking did not mediate the effect of MI on alcohol use. Next, indirect effects were calculated to determine the relative importance of individual mediators within the context of the multiple mediator model. Boostrapped point estimates for readiness were −.05 (95% BCa bootstrap CI of −.33 to .06), risk/benefit .01 (95% BCa bootstrap CI of −.14 to .19), self-efficacy −.07 (95% BCa bootstrap CI of −.45 to .09), and treatment seeking .03 (95% BCa bootstrap CI of −.14 to .30), indicating that none of the four variables significantly mediated the relationship between intervention and alcohol use.

Coefficient values for each mediator along each path of the multiple mediator model are shown in Figure 2.5 The results for the a and b paths suggest that as compared to FO, the MI group showed a trend toward higher readiness and greater treatment seeking, but did not show the expected shift in perceived risks/benefits of drinking or self-efficacy. Higher self-efficacy was significantly associated with lower levels of alcohol use, and a shift in perceived risks/benefits showed a trend toward lower alcohol use.

Figure 2.

Direct effect of individual mediators and direct effect of treatment

Discussion

This study evaluated moderation and mediation hypotheses related to the effects of brief interventions on alcohol use and related consequences in a real-world setting. We found that having used alcohol prior to the medical event, attribution about the role of alcohol in the event, and readiness to change alcohol use at the time of ED treatment moderated the efficacy of brief interventions for alcohol with young adult patients. Specifically, patients who had not been drinking prior to coming to the ED but had high alcohol severity showed lower alcohol use and lower alcohol-related injury rates 12 months after receiving a counselor-administered brief motivational intervention compared to a personalized feedback report with minimal counselor contact. In contrast, patients who had an alcohol-related event did not show different responses to the more and less intensive interventions, regardless of their alcohol severity status. It appears that patients for whom alcohol was not involved in the event benefitted from counselor-guided consideration of the risks related to their alcohol use, whereas patients already experiencing a consequence of alcohol use did not show added benefit from the counselor intervention compared to only receiving the feedback report.

Our findings contribute to the limited research literature investigating the effects of alcohol status and alcohol severity on intervention response in ED patients. The present study indicates that counselor-based intervention confers additional benefit beyond the effect of personalized feedback for patients who meet a severity criterion but are not alcohol-positive. Consistent with Longabaugh et al. (13), we found no differences between alcohol-positive and alcohol-negative patients on subsequent alcohol problems; our group moderation findings were detected on alcohol consumption and alcohol injuries.

Patients with low and medium attribution about the role of alcohol in their event also showed intervention group differences favoring MI over FO, but those high in attribution did not show intervention group differences. Contrary to Walton et al. (35) we found alcohol use prior to the event was a significant moderator (i.e., intervention group findings differed for alcohol-positive and alcohol-negative patients), and was more important than patient attribution about alcohol in the event; our findings may differ due to different inclusion criteria, intervention conditions or ages of our samples.

Readiness to change alcohol use had a similar moderation result as attribution of alcohol in the event; patients who had low or moderate levels of readiness to change showed better alcohol use outcomes if they received MI rather than FO. MI may have differential utility for individuals who are less ready to change, consistent with other treatment study outcomes (39) and with MI’s theoretical foundation (11). Indeed, readiness to change was the strongest moderator of intervention outcome, in that it retained its significance in the analysis that included alcohol status and attribution about the importance of alcohol in the event. It is possible that shared variance between alcohol status and attribution (r = .46, p < .001) caused neither of these constructs to have unique variance. It is also likely that readiness to change is a more complex construct, in that it reflects one’s history of alcohol use and related problems, which is more relevant for personal behavior change than one critical event or attribution of that event. An advantage of readiness to change as a potential basis for intervention triage in medical settings is that it is relevant for all patients regardless of alcohol status.

The original trial found intervention group differences on alcohol consumption variables only (14), but in our moderation analyses we found that the subgroup of AUDIT+ Only patients also had lower rates of alcohol-related injuries when they received MI rather than FO. In addition, the effect size for MI in the AUDIT+ Only group was in the moderate range for the alcohol problems outcome measure (RAPI). These findings signify the importance of evaluating subgroup outcomes that may be obscured by overall group means, and reflect the value of using multiple indicators of intervention success.

Our analyses consistently showed that individuals who had not had an alcohol event, had low to medium attribution about the role of alcohol in the event, and low to medium readiness to change alcohol use benefitted more from MI than FO. In contrast, alcohol-involved patients benefitted equally from either intervention. For these patients, a “teachable moment” may have been facilitated by hospital treatment, attention paid to their alcohol use, and/or other effects such as the reaction of family and friends to the ED incident. These circumstances may have led to greater receptivity to intervention in any format, or may have produced change without intervention (although prior ED research found a benefit of MI over standard care (12) among alcohol-positive patients). In the current study, readiness to change was not correlated with alcohol status or attribution, so the processes prompted by these variables, although consistent, may be independent.

Gender differences in intervention efficacy were not found, consistent with conclusions drawn by Ballesteros et al. (74). Effect sizes were very small, indicating our relatively small subsample of women was not the reason for the nonsignificant effects. Aversiveness of the event and perceived seriousness of the event also did not moderate intervention effects; their intercorrelation and correlations with both readiness to change and attribution about alcohol in the event suggest these elements do not contribute independently to intervention outcomes.

In our mediation analyses one individual path from self-efficacy to outcome was statistically significant while several paths showed trends. The total indirect effect of the set of mediators in the current study was nonsignificant, as were each of the specific indirect effects. The absence of mediation was surprising given the theoretical relevance of chosen mediators and the conceptually and statistically optimal approach to data analysis. It is possible the elements we investigated are relevant but not treatment specific, or that their impact varies by other important conditions. Our results highlight the difficulty of illuminating mechanisms of treatment outcomes in psychosocial treatments for alcohol use disorders in general and for MI-based approaches in particular.

Limitations

Kazdin and Nock (75) have pointed out that a temporal relationship between change in the mediator and the outcome is required to establish mediation. Our assessments met this criterion by measuring readiness to change immediately post-treatment, and risks/benefits, self-efficacy, and treatment seeking 6 months post-treatment, but this timing was not ideal. Our inability to detect mediation may be due to the length of time and potential exposure to drinking during the six months following intervention. It is also possible that measuring mediators only once following intervention limited our ability to detect relationships. A single assessment may not be adequate to capture the processes through which individuals change, particularly as they become further removed from the intervention experience. However, full tests of mediation with multiple constructs of theoretical importance are very rare (44), so the current study advances the knowledge base on mechanisms of action for motivational interviewing.

Other limitations include the lack of a no-treatment control group, the possibility of assessment reactivity (although recent research indicates assessment conducted in the ED may not account for behavior changes (25)), and the limited age range of patients, which may restrict the generalizability of findings. Finally, some analyses were conducted with less than the entire sample due to missing data and/or the need to aggregate outcomes over time.

Conclusions and Future Directions

This study demonstrated that patient characteristics that can be measured easily in an ED are relevant for brief intervention efficacy and could provide an empirical basis for clinical practice guidelines. Brief interventions in medical settings typically are conducted opportunistically among patients identified via screening or reactively in response to an alcohol-related event. Our findings indicate that patients can be provided an intervention most appropriate to their alcohol status and to their readiness to change. For example, whether a person was drinking prior to their medical event, whether they score above the AUDIT score cutoff, and a single item readiness to change measure could be used to triage patients into the most cost-efficient efficacious intervention. Counselor contact appears warranted for young adult patients with risky alcohol use but low to moderate readiness to change. Less intensive intervention may be sufficient for patients being treated for an alcohol-related event. Our findings should be replicated, particularly in other age groups, before being translated into this clinical recommendation. In addition, cost effectiveness analyses have established the utility of single session brief interventions (76, 77), but not of briefer targeted interventions such as the personalized feedback report.

Future research should systematically study the salience of alcohol use in the ED, readiness to change, and associations with other event and patient characteristics to match patients optimally to specific intervention approaches. Research should also explore whether interventions following critical alcohol events modify the salience of the event and whether changes in patient reactions to such events mediate intervention outcomes. Studies of mediation might be enhanced by more frequent and sensitive measurement of putative mediators, as the process of change may be too dynamic and/or complex to capture using existing measures that are typically administered once yet used to reflect a long time frame. Finer-grained approaches hold promise for future investigations of mechanisms of change.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the counselors who conducted the interventions, the research assistants who conducted the follow up interviews, and our patient participants for their time and cooperation. We also wish to thank Suzanne Sales for data analytic assistance and the journal reviewers for their helpful feedback.

This investigation was supported in part by research grant AA09892 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, and by a Senior Research Career Scientist Award to Dr. Monti from the Medical Research Service Office of Research and Development, Department of Veterans Affairs. The authors have no connection with the tobacco, alcohol, pharmaceutical or gaming industries or any body substantially funded by one of these organizations.

Footnotes

Portions Of This Study Were Presented At The Meeting Of The Research Society On Alcoholism, In Santa Barbara, Ca In 2005.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00246428

The number of participants in the current study is slightly higher than in Monti et al. (14), but all outcomes in this larger sample are identical to those found in the published trial.

One item about testing control over alcohol was removed because it assumed the participant considered his/her alcohol use a problem, which was not a reasonable assumption for this sample.

Subject numbers vary across variables due to missing data on some measures.

One possibility we considered was whether a positive alcohol level at baseline may have made participants unable to benefit from the MI. To test this we evaluated whether: 1) baseline BAC was correlated with alcohol use outcomes; 2) BAC moderated intervention outcomes; and 3) including BAC as a covariate in moderator analyses changed findings. Mean BAC at baseline for ALC+ participants was .050% (SD =.057; range .000–.206). BAC was not correlated with change in alcohol use from baseline to follow up (r = .05, ns), nor did it interact with intervention condition on alcohol use outcomes (β = .08, ns). Finally, covarying baseline BAC in moderation analyses produced no differences in findings.

While the multiple mediator model approach (73) emphasizes the direction of individual paths over statistical significance, we have presented significance values to be consistent with common convention.

References

- 1.Gentilello LM, Donovan DM, Dunn CW, Rivara FP. Alcohol interventions in trauma centers: Current practice and future directions. JAMA. 1995;274(13):1043–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cherpitel CJ. Drinking patterns and problems: A comparison of primary care with the Emergency Room. Substance Abuse. 1999 Jun;20(2):85–95. doi: 10.1080/08897079909511397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cherpitel CJ. Alcohol and injuries: A review of international emergency room studies. Addiction. 1993;88:651–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dischinger PC, Mitchell KA, Kufera JA, Soderstrom CA, Lowenfels AB. A longitudinal study of former trauma center patients: The association between toxicology status and subsequent injury mortality. J Trauma. 2001;51(5):877–86. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200111000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bien TH, Miller WR, Tonigan JS. Brief interventions for alcohol problems: A review. Addiction. 1993;88:315–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gentilello LM, Rivara FP, Donovan DM, Jurkovich GJ, Daranciang E, Dunn CW, et al. Alcohol interventions in a trauma center as a means of reducing the risk of injury recurrence. Ann Surg. 1999;230(4):473–80. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199910000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Havard A, Shakeshaft A, Sanson-Fisher R. Systematic review and meta-analyses of strategies targeting alcohol problems in emergency departments: Interventions reduce alcohol-related injuries. Addiction. 2008 Mar;103(3):368–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02072.x. discussion 77–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crawford MJ, Patton R, Touquet R, Drummond C, Byford S, Barrett B, et al. Screening and referral for brief intervention of alcohol-misusing patients in an emergency department: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004 Oct 9–15;364(9442):1334–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17190-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hungerford DW, Pollock DA. Emergency Department services for patients with alcohol problems: Research directions. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:79–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb01982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American College of Surgeons. Resources for Optimal Care of the Injured Patient. Chicago: American College of Surgeons Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people to change addictive behavior. 2. New York: Guilford; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monti PM, Colby SM, Barnett NP, Spirito A, Rohsenow DJ, Myers M, et al. Brief intervention for harm reduction with alcohol-positive older adolescents in a hospital emergency department. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999 Dec;67(6):989–94. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Longabaugh R, Woolard RE, Nirenberg TD, Minugh AP, Becker B, Clifford PR, et al. Evaluating the effects of a brief motivational intervention for injured drinkers in the emergency department. J Stud Alcohol. 2001 Nov;62(6):806–16. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monti PM, Barnett NP, Colby SM, Gwaltney CJ, Spirito A, Rohsenow DJ, et al. Motivational interviewing versus feedback only in emergency care for young adult problem drinking. Addiction. 2007 Aug;102(8):1234–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burke BL, Arkowitz H, Menchola M. The efficacy of motivational interviewing: a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003 Oct;71(5):843–61. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nilsen P, Baird J, Mello MJ, Nirenberg T, Woolard R, Bendtsen P, et al. A systematic review of emergency care brief alcohol interventions for injury patients. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008 Sep;35(2):184–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spirito A, Monti PM, Barnett NP, Colby SM, Sindelar H, Rohsenow DJ, et al. A randomized clinical trial of a brief motivational intervention for alcohol-positive adolescents treated in an emergency department. J Pediatr. 2004 Sep;145(3):396–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beckman LJ. Barriers to alcoholism treatment for women. Alcohol Health Res World. 1994;18(3):208–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reed BG. Developing women-sensitive drug dependence treatment services: why so difficult? J Psychoactive Drugs. 1987 Apr–Jun;19(2):151–64. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1987.10472399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thom B. Sex differences in help-seeking for alcohol problems--1. The barriers to help-seeking. Br J Addict. 1986 Dec;81(6):777–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1986.tb00405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tijunelis MA, Fitzsullivan E, Henderson SO. Noise in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2005 May;23(3):332–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2005.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor SE, Klein LC, Lewis BP, Gruenewald TL, Gurung RA, Updegraff JA. Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight. Psychol Rev. 2000 Jul;107(3):411–29. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.107.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Babor TF, Grant M, Acuda W, Burns FH, Campillo C, Del Boca FK, et al. A randomized clinical trial of brief interventions in primary care: summary of a WHO project. Addiction. 1994 Jun;89(6):657–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb00944.x. discussion 60–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fromme K, Orrick D. The Lifestyle Management Class: A harm reduction approach to college drinking. Addiction Research & Theory. 2004 Aug;12(4):335–51. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daeppen JB, Gaume J, Bady P, Yersin B, Calmes JM, Givel JC, et al. Brief alcohol intervention and alcohol assessment do not influence alcohol use in injured patients treated in the emergency department: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Addiction. 2007 Aug;102(8):1224–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blow FC, Barry KL, Walton MA, Maio RF, Chermack ST, Bingham CR, et al. The efficacy of two brief intervention strategies among injured, at-risk drinkers in the emergency department: Impact of tailored messaging and brief advice. J Stud Alcohol. 2006;67(4):568–78. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson P, Scott E. The effect of general practitioners’ advice to heavy drinking men. Br J Addict. 1992;87:891–900. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1992.tb01984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scott E, Anderson P. Randomized controlled trial of general practitioner intervention in women with excessive alcohol consumption. Drug and Alcohol Review. 1990;10:313–21. doi: 10.1080/09595239100185371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Becker M. The health belief model and sick role behavior. Health Education Monograph. 1974;2:409–19. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dunn C, Zatzick D, Russo J, Rivara F, Roy-Byrne P, Ries R, et al. Hazardous drinking by trauma patients during the year after injury. The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Clinical Care. 2003 Apr;54(4):707–12. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000030625.63338.B2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosenstock IM. Historical origins of the health belief model. Health Education Monograph. 1974;2:328–35. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cherpitel CJ, Bond J, Ye Y, Borges G, Room R, Poznyak V, et al. Multi-level analysis of causal attribution of injury to alcohol and modifying effects: Data from two international emergency room projects. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;82:258–68. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nilsen P, Holmqvist M, Nordqvist C, Bendtsen P. Linking drinking to injury – causal attribution of injury to alcohol intake among patients in a Swedish emergency room. International Journal of Injury Control and Safety Promotion. 2007;14(2):93–102. doi: 10.1080/17457300701374759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Longabaugh R, Minugh PA, Nirenberg TD, Clifford PR, Becker B, Woolard R. Injury as a motivator to reduce drinking. Acad Emerg Med. 1995;2:817–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1995.tb03278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walton MA, Goldstein AL, Chermack ST, McCammon RJ, Cunningham RM, Barry KL, et al. Brief alcohol intervention in the emergency department: moderators of effectiveness. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2008 Jul;69(4):550–60. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barnett NP, Lebeau-Craven R, O’Leary TA, Colby SM, Rohsenow DJ, Monti PM, et al. Predictors of motivation to change after medical treatment for drinking-related events in adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2002 Jun;16(2):106–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dauer AR, Rubio ES, Coris ME, Valls JM. Brief intervention in alcohol-positive traffic casualties: Is it worth the effort? Alcohol Alcohol. 2006 Jan-Feb;41(1):76–83. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller WR. Motivational interviewing: III. On the ethics of motivational intervention. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 1994;22(2):111–23. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heather N, Rollnick S, Bell A, Richmond R. Effects of brief counseling among male heavy drinkers identified on general hospital wards. Drug and Alcohol Review. 1996;15(1):29–38. doi: 10.1080/09595239600185641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Project MATCH Research Group. Matching Alcoholism Treatments to Client Heterogeneity: Project MATCH posttreatment drinking outcomes. J Stud Alcohol. 1997;58(1):7–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rohsenow DJ, Monti PM, Martin RA, Colby SM, Myers M, Gulliver SB, et al. Motivational enhancement and coping skills training for cocaine abusers: Effects on substance use outcomes. Addiction. 2004;99:862–874. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maisto SA, Conigliaro J, McNeil M, Kraemer K, Conigliaro RL, Kelley ME. Effects of two types of brief intervention and readiness to change on alcohol use in hazardous drinkers. J Stud Alcohol. 2001 Sep;62(5):605–14. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Apodaca TR, Longabaugh R. Mechanisms of change in motivational interviewing: A review and preliminary evaluation of the evidence. Addiction. 2009;104:705–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02527.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saunders B, Wilkinson C, Phillips M. The impact of a brief motivational intervention with opiate users attending a methadone programme. Addiction. 1995 Mar;90(3):415–24. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.90341510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Handmaker NS, Miller WR, Manicke M. Findings of a pilot study of motivational interviewing with pregnant drinkers. J Stud Alcohol. 1999 Mar;60(2):285–7. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Longshore D, Grills C, Annon K. Effects of a culturally congruent intervention on cognitive factors related to drug-use recovery. Subst Use Misuse. 1999 Jul;34(9):1223–41. doi: 10.3109/10826089909039406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miller WR, Yahne CE, Tonigan JS. Motivational interviewing in drug abuse services: A randomized trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71(4):754–63. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schneider RJ, Casey J, Kohn R. Motivational versus confrontational interviewing: A comparison of substance abuse assessment practices at employee assistance programs. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2000 Feb;27(1):60–74. doi: 10.1007/BF02287804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stotts AL, Schmitz JM, Rhoades HM, Grabowski J. Motivational interviewing with cocaine-dependent patients: A pilot study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69(5):858–62. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.5.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Longabaugh R. Comments on Dunn et al.’s “The use of brief interventions adapted from motivational interviews across behavioral domains: a systematic review”. Why is motivational interviewing effective? Addiction. 2001 Dec;96(12):1773–4. discussion 4–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miller WR. Enhancing motivation for change in substance abuse treatment; Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series. 1999. DHHS Publication No. 99-3354. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Galbraith IG. Minimal interventions with problem drinkers--a pilot study of the effect of two interview styles on perceived self-efficacy. Health Bull (Edinb) 1989 Nov;47(6):311–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Project MATCH Research Group. Matching alcoholism treatments to client heterogeneity: Project MATCH three-year drinking outcomes. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:1300–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.DiClemente CC, Carbonari JP, Daniels JW, Donovan DM, Bellino LE, Neavins TM. Self-efficacy as a matching hypothesis: Causal chain analysis. Bethesda: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Project MATCH Hypotheses: Results and Causal Chain Analysis; 2001. NIH Publication No. 01-4238. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barnett NP, Murphy JG, Colby SM, Monti PM. Efficacy of counselor vs. computer-delivered intervention with mandated college students. Addict Behav. 2007 Nov;32(11):2529–48. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bernstein E, Bernstein J, Levenson S. Project ASSERT: An ED-based intervetnion to increase access to primary care, preventive services, and the substance abuse treatment system. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;30(2):181–9. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(97)70140-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schilling RF, El-Bassel N, Finch J, Roman RJ, Hanson M. Motivational interviewing to encourage self-help participation following alcohol detoxification. Research on Social Work Practice. 2002;12(6):711–30. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Swanson AJ, Pantalon MV, Cohen KR. Motivational interviewing and treatment adherence among psychiatric and dually diagnosed patients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1999;187:630–5. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199910000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bernstein J, Bernstein E, Tassiopoulos K, Heeren T, Levenson S, Hingson R. Brief motivational intervention at a clinic visit reduces cocaine and heroin use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;77:49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Connors GJ, Walitzer KS, Dermen KH. Preparing clients for alcoholism treatment: Effects on treatment participation and outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70(5):1161–9. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.5.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, De La Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption-II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Alcohol Timeline Followback users’ manual. Toronto, Canada: Addiction Research Foundation; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 64.White HR, Labouvie EW. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. J Stud Alcohol. 1989;50:30–7. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Spirito A, Rasile D, Vinnick C, Jelalian E, Arrigan ME. Relationship between substance abuse and self-reported injuries among adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 1997;21:221–4. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(97)00113-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fromme K, Katz EC, Rivet K. Outcome expectancies and risk-taking behavior. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1997;21(4):421–42. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Breslin FC, Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Agrawal S. A comparison of a brief and long version of the Situational Confidence Questionnaire. Behav Res Ther. 2000 Dec;38(12):1211–20. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00152-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Holmbeck GN. Post-hoc probing of significant moderational and mediational effects in studies of pediatric populations. J Pediatr Psychol. 2002 Jan;27(1):87–96. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bauer DJ, Curran PJ. Probing interactions in fixed and multilevel regression: Inferential and graphical techniques. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2005;40:373–400. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr4003_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interaction effects in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31:437–448. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–91. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 2004;36:717–31. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ballesteros J, Gonzalez-Pinto A, Querejeta I, Arino J. Brief interventions for hazardous drinkers delivered in primary care are equally effective in men and women. Addiction. 2004 Jan;99(1):103–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kazdin AE, Nock MK. Delineating mechanisms of change in child and adolescent therapy: methodological issues and research recommendations. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2003 Nov;44(8):1116–29. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gentilello LM, Ebel BE, Wickizer TM, Salkever DS, Rivara FP. Alcohol interventions for trauma patients treated in emergency departments and hospitals: a cost benefit analysis. Ann Surg. 2005 Apr;241(4):541–50. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000157133.80396.1c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Neighbors CJ, Barnett NP, Rohsenow DJ, Colby SM, Monti PM. Cost-effectiveness of a motivational intervention for alcohol-involved youth in a hospital Emergency Department. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.384. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]