Abstract

Aims and objectives

This paper provides a context for this special edition. It highlights the scale of the challenge of nursing shortages, but also makes the point that there is a policy agenda that provides workable solutions.

Results

An overview of nurse:population ratios in different countries and regions of the world, highlighting considerable variations, with Africa and South East Asia having the lowest average ratios. The paper argues that the ‘shortage’ of nurses is not necessarily a shortage of individuals with nursing qualifications, it is a shortage of nurses willing to work in the present conditions. The causes of shortages are multi-faceted, and there is no single global measure of their extent and nature, there is growing evidence of the impact of relatively low staffing levels on health care delivery and outcomes. The main causes of nursing shortages are highlighted: inadequate workforce planning and allocation mechanisms, resource constrained undersupply of new staff, poor recruitment, retention and ‘return’ policies, and ineffective use of available nursing resources through inappropriate skill mix and utilisation, poor incentive structures and inadequate career support.

Conclusions

What now faces policy makers in Japan, Europe and other developed countries is a policy agenda with a core of common themes. First, themes related to addressing supply side issues: getting, keeping and keeping in touch with relatively scarce nurses. Second, themes related to dealing with demand side challenges. The paper concludes that the main challenge for policy makers is to develop a co-ordinated package of policies that provide a long term and sustainable solution.

Relevance to clinical practice

This paper highlights the impact that nursing shortages has on clinical practice and in health service delivery. It outlines scope for addressing shortage problems and therefore for providing a more positive staffing environment in which clinical practice can be delivered.

Keywords: nurses, nursing, workforce issues, workforce planning

Introduction

The world has entered a critical period for human resources for health. The scarcity of qualified health personnel, including nurses, is being highlighted as one of the biggest obstacles to achieving health system effectiveness. In January 2004, the High Level Forum on the Health Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) reported, ‘There is a human resources crisis in health, which must be urgently addressed’ (High Level Forum on the Health MDGs, 2004, p. 4). Later in the same year, the Joint Learning Initiative reported that ‘There is a massive global shortage of health workers’ (Joint Learning Initiative 2004; executive summary, p. 3). In 2006, the World Health Organisation devoted the whole of the World Health Report to the negative impact that human resources shortages was having on global health care (WHO 2006).

Against this backdrop of growing concern about shortages of health personnel, this paper focuses on one of the most critical components of the workforce: nurses. As such, it provides a context for the other papers in this special edition of the Journal of Clinical Nursing. These other papers focus in detail on specific nurse workforce issues and priorities facing policy makers and researchers in Australia, Canada, Japan, the USA and elsewhere. They emphasise the need to develop a better understanding of the specific dynamics in organisational and country level nursing labour markets if policy makers are to be well informed about the judgements they must make about what will be effective policy solutions for the nursing workforce. This paper provides a broader perspective, highlighting the scale of the challenge of nursing shortages, but also making the point that there are many common challenges and a policy agenda that points to workable solutions.

Nursing and the global health workforce challenge

WHO has estimated there to be a total of 59·2 million fulltime paid health workers worldwide in 2006, of which about two thirds were health service providers, with the remaining third being composed of health management and support workers (WHO 2006).

WHO also calculated a threshold in workforce density below which consistent coverage of essential interventions, including those necessary to meet the health-related Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), was very unlikely. Based on these estimates, it reported that there were 57 countries with critical shortages equivalent to a global deficit of 2·4 million doctors, nurses and midwives. The proportional shortfalls were greatest in sub-Saharan Africa, although numerical deficits were very large in South-East Asia because of its population size (WHO 2006, p. 12). WHO also highlighted that shortages often coexist in a country with large numbers of unemployed health professionals: ‘Poverty, imperfect private labour markets, lack of public funds, bureaucratic red tape and political interference produce this paradox of shortages in the midst of underutilized talent’ (WHO 2006, p. xviii).

WHO concluded that the shortage crisis has the potential to deepen in the coming years. It noted that demand for service providers will escalate markedly in all countries – rich and poor: ‘Richer countries face a future of low fertility and large populations of elderly people, which will cause a shift towards chronic and degenerative diseases with high care demands. Technological advances and income growth will require a more specialised workforce even as needs for basic care increase because of families’ declining capacity or willingness to care for their elderly members. Without massively increasing training of workers in this and other wealthy countries, these growing gaps will exert even greater pressure on the outflow of health workers from poorer regions’ (WHO 2006, p. xix).

Nurses are the main professional component of the ‘front line’ staff in most health systems, and their contribution is recognised as essential to meeting development goals and delivering safe and effective care. One difficulty in making an accurate global estimate of numbers of nurses is the definition of ‘nurse’. Different international agencies, at different times, have developed different definitions, some related to educational level, some to years of training. The primary focus of this paper is on registered nurses, but this focus is hampered by the absence of a clear definition for some data sources, and the overall lack of a single universal definition of ‘nurse’. To give one indication of the size of the nursing workforce world wide, the International Council of Nurses reports 129 national nurses’ associations representing 13 million nurses worldwide (ICN 2007).

This section of the paper provides an overview of nurse:population ratios in different countries and regions of the world. The data must be used with caution. The country level data collated by WHO which is reported in this paper may in some countries include midwives under the broad category of nurses; for some, it is also likely that the data may include auxiliary and unlicensed personnel. There can also be varying interpretations relating to the calculation of the number of nurses – some countries may report working nurses, others may report all nurses that are eligible to practice; some may report ‘headcount’, others may report full time equivalents. The analysis presented below should therefore be taken as illustrative of a broad pattern of regional variations, rather than an accurate representation of each country. Current initiatives by international organisations such as WHO, ILO and OECD to agree to standard definitions and improve the collection of country level HRH data should improve the current unsatisfactory situation.

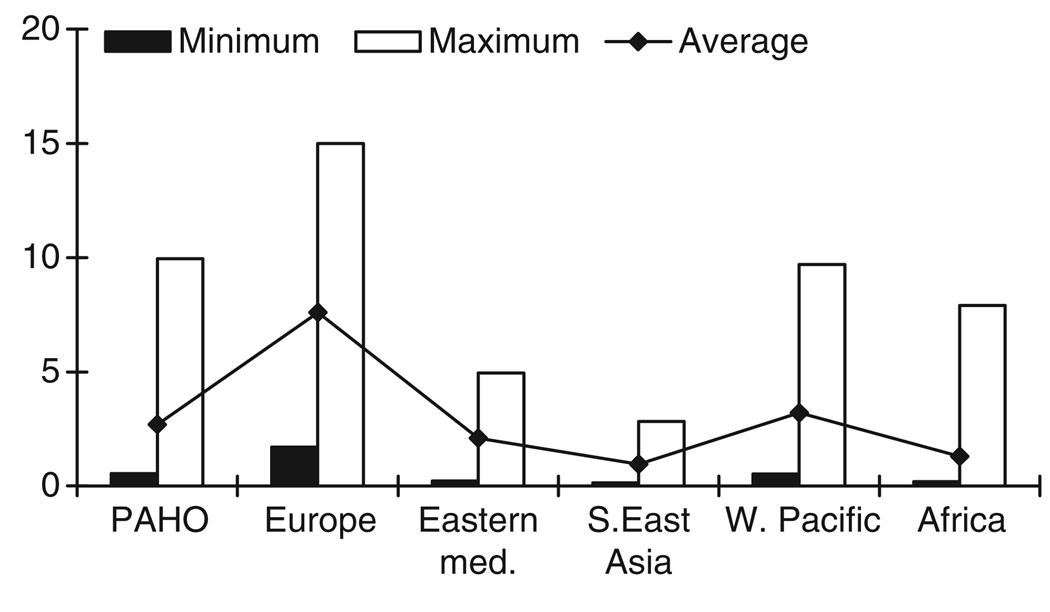

The nurse:population ratio gives a very broad indication of the level of availability of professional nursing skills in each country. In this paper, data are analysed at the level of main WHO Regions: The Americas (Pan American Health Organisation- PAHO), Europe (EURO), Eastern Mediterranean (EMRO), Africa (AFRO), South East Asia (SEARO) and Western Pacific (WPRO). Full details of the country allocation can be found on the WHO website: http://www.who.int. Figure 1 illustrates the minimum, maximum and average nurse:population ratios for each of the WHO regions. Given the limitations noted above, these data have to be used with caution, and average is a more useful indicator, as the minimum or maximum may reflect the distorting effect of one or two ‘outlier’ countries which skews the overall picture. For example, in the African region, Seychelles and South Africa report much higher ratios of nurse to population than do other countries in the region.

Figure 1.

Nurse:population ratio (nurse per 1000 population) – min, max and average by WHO region. Source: Buchan and Aiken, based on analysis of data in WHO 2006. Note: See text for discussion of limitations in data.

The figure highlights that there is considerable variation between regions with Africa and South East Asia having the lowest average ratios. The average ratio in Europe, the region with the highest ratios, is almost ten times the average ratio in the lowest region. At country level, there is a hundred-fold difference in the ratio across the world, between the countries with the lowest reported ratio, in Africa and South East Asia, and the countries with the highest reported ratio, in Europe. At country level, the reported ratio varies from less than 0·2 nurses per 1000 population in countries such as Bangladesh, and Liberia to more than 10 nurses per 1000, in countries such as Finland, Norway and Ireland.

Looking in isolation at only one type of staff:population ratio may be misleading. WHO has also estimated the population ratios for other staff groups, including physicians and midwives. At regional level, there are significant variations in the mix between different staff groups (e.g. Latin American countries tend to have two or three times as many physicians as nurses, whilst countries on other regions tend to have more nurses than physicians), but there tends to be a pattern that countries with higher numbers of nurses per 1000 population also have higher ratios of doctors and other staff. The 2006 World Health report highlights the extent to which staffing levels are a funding related feature. Health care is labour intensive; countries that invest more in health care expenditure tend to have higher staffing levels (see also Wharrad & Robinson 1999).

Skill mix and staff mix vary between organisations, systems and countries, but overall it is clear from the data that many countries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, Central/South America and South East Asia, report very low ratios of nurses to population. They are struggling even to provide a minimum level of nurse staffing. Some, most notably in Central/South America, also report employing many more physicians than nurses. The significant variations in current mix of staff have to be considered, as well as the overall availability of any one occupation, when examining how best to improve effectiveness and deal with shortages.

Low absolute numbers of available nurses in many countries is compounded by difficulties with their geographic distribution. Many countries report difficulties in recruiting and retaining nurses and other health care professionals in rural and remote areas. This is a feature of both developed and developing countries (see e.g. Hossain & Begum 1998, Hegney et al. 2002). This problem is often exacerbated by the tendency of health professionals to prefer to work in a large urban area, where job prospects and career opportunities are greater. The geographical ‘misdistribution’ creates difficulties for planners. Rural areas in developing countries tend to be the most underserved areas, in terms of availability of nurses.

Nursing shortages and their impact

A nursing shortage is not just an organisational challenge or a topic for economic analysis; it has a major negative impact on health care (Buchan 2006). Failure to deal with a nursing shortage – be it local, regional, national or global – will lead to failure to maintain or improve health care.

From a country-level policy perspective, a nurse staffing shortage is usually defined and measured in relation to that country’s own historical staffing levels, resources and estimates of demand for health services. It is the gap between the reality of current availability of nurses and the aspiration for some higher level of provision, however defined, that is the ‘shortage’ (Buchan 2006). As such, it is not easily quantifiable and is a label that is applied to different definitions or used differently by different stakeholders even in the same county context.

A WHO source has noted that ‘There is no absolute norm regarding the ‘right’ ratio of physicians or nurses to population. This depends on (1) demand factors, e.g. demographic and epidemiological trends, service use patterns and macro-economic conditions; (2) supply factors, such as labour market trends, funds to pay salaries, health professions education capacity, licensing and other entry barriers; (3) factors affecting productivity, e.g. technology, financial incentives, staff mix, and management flexibility in resource deployment, and (4) priority allocated to prevention, treatment and rehabilitation in national health policies. Generally, shortages or oversupply are assessed based on comparisons with countries in the same region or at the same level of development’ (WHO 2001).

In a more recent WHO led paper examining the issue of imbalances in the health workforce (Zurn et al. 2002) the authors noted that there are both ‘economic’ and ‘non-economic’ definitions of skill imbalance, and that these imbalances may be ‘static’ or ‘dynamic’. If static, they are likely to respond only slowly, if at all, to market forces due to regulatory mechanisms, monopoly situations or wage controls, which can exist in health care labour markets.

At its most basic level, a shortage would be identified where an imbalance exists between the requirements for nursing skills (usually defined as a number of nurses) and the actual availability of nurses. ‘Availability’ has to be qualified by noting that not all ‘available’ nurses will actually be willing to work at a specific wage or package of work related benefits (Buchan 1994, 2006). Some nurses may choose alternative non-nursing employment or no employment.

A ‘shortage’ is therefore not merely about a numbers game or an economic model, it is about individual and collective decision-making and choice (Buchan 2000, 2006). The ‘shortage’ is not necessarily a shortage of individuals with nursing qualifications, it is a shortage of nurses willing to work as nurses in the present conditions. As such, the search for solutions to shortages has to focus on the motivation of nurses, and incentives to recruit and retain them, and encourage them back into nursing, as well as on the broader supply/demand planning framework.

It must also be noted that in previous decades, nursing shortages in many developed countries have been a cyclical phenomenon, usually as a result of increasing demand outstripping static or more slowly growing supply of nurses (see e.g. Friss 1994, Buchan 2002, Goodin 2003). However, the current situation may be more serious. Driven by growing and ageing populations, demand for health care and for nurses continues to grow, whilst the supply of available nurses has actually fallen or flat-lined in some developed and developing countries.

Whilst the causes of shortages are multi-faceted, and there is no single global measure of their extent and nature, there is growing evidence of the impact of relatively low staffing levels on health care delivery and outcomes, despite the difficulties of relating different data sets (see e.g. Wharrad & Robinson 1999, Anand & Barnighausen 2004, Speybroeck et al. 2006).

In some developed countries, there is a broader and more complete range of data sets available, which supports more informed analysis of the relationship between nurse staffing levels and measures of care outcome. A range of studies have demonstrated links between nurse staffing levels and a range of negative health outcomes (Kane et al. 2007). These include increased mortality rates (Aiken et al. 2002a; Rafferty et al. 2007); adverse events after surgery (Kovner & Gergen 1998); increased incidence of violence against staff (James et al. 1990); increased accident rates and patient injuries (ARCHI 2003); and increased cross infection rates (Stanton 2004). The majority of nurses in a wide range of countries say there are too few nurses in hospitals to provide care of reasonable quality, and in a multinational survey, a third to almost half of bedside care nurses scored in the high range on standardised measures of job burnout (Aiken et al. 2001, 2002b). The OECD has noted, ‘Nursing shortages are an important policy concern in part because numerous studies have found an association between higher nurse staffing ratios and reduced patient mortality, lower rates of medical complications and other desired outcomes.’ (OECD 2004).

Nursing shortages: the policy agenda

The USA, with a reported nurse:population ratio of almost 10 nurses to 1000 population, is reporting nursing shortages. So too are countries in Africa and Asia with a reported nurse:population ratio of less than 0·5 nurses per 1000 population. Clearly, the issue of defining, measuring and addressing nursing shortages has to take account of the huge disparity in the current availability of nursing skills in different countries, sectors and regions. However, whatever the resources available, the evidence highlights that there are a core common set of issues and methods that policy makers should focus on in order to maximise the impact of interventions intended to deal with shortages.

One important issue to note is that there is no single ‘magic bullet’ policy that will solve nursing shortages. The evidence base on the effectiveness of human resource policy interventions highlights two key factors (see e.g. Richardson & Thompson 1999, Buchan 2004). First that there is a need to consider what has been termed ‘contingency’ – that the HR policies being implemented must ‘fit’ (be contingent with) the characteristics, context and priorities of the organisation or system in which they are being applied. Second, that so-called ‘bundles’ of linked and coordinated HR policy interventions will be more likely to achieve sustained improvements in organisational performance than single or uncoordinated interventions. In the often ‘politicised’ health sector, where short term focus is often paramount in policy determination, and where cycles of shortages may challenge system stability, this is an important message.

It should also be noted that identifying the ‘best practice’ evidence base on dealing with shortages is one thing, but translating this into widespread and sustained application of the appropriate bundle of HR policy interventions is another. There is evidence that there is a relative lack of ‘take up’ of HR good practice: even when it has been verified by research studies, it is not always evident in day-to-day practice in many organisations (Richardson & Thompson 1999, Buchan 2004). This highlights an important issue for any country or organisation wishing to improve its HR policy and practice in relation to nursing shortages: it must support sustained and co-ordinated implementation of these policies.

In a recent report, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) highlighted that ‘There are reports of current nurse shortages in all but a few OECD countries. With further increases in demand for nurses expected and nurse workforce ageing predicted to reduce the supply of nurses, shortages are likely to persist or even increase in the future, unless action is taken to increase flows into, and reduce flows out of the workforce or to raise the productivity of the workforce’ (Simoens et al. 2005, para 1).

Many high-income countries in Japan, Europe, North America and elsewhere are facing a demographic ‘double whammy’ – they have an ageing nursing workforce caring for increasing numbers of elderly (Buchan 2006, Buchan & Calman 2006). The OECD report and other studies focusing on nursing shortages in developed countries (e.g. CIHI 2003, National Center for Health Workforce Analysis 2007) have highlighted the main causes of these shortages as being: inadequate workforce planning and allocation mechanisms (creating a mismatch between education supply and service based funded demand), resource constrained undersupply of new staff, poor recruitment, retention and ‘return’ policies, and ineffective use of available nursing resources through inappropriate skill mix and utilisation, poor incentive structures and inadequate career support.

Other factors contributing to nursing shortages, which require policy attention, include: the continued existence of gender-based discrimination in many countries and cultures, with nursing being undervalued or downgraded as ‘women’s work’; the persistence of violence against health workers in many countries with nurses often taking the brunt because they are in the forefront of the direct delivery of care; and the legacy of demotivation that exists in some organisations or countries which have persevered with ill conceived or badly implemented health sector reforms or ‘re-engineering’ projects or adjustment programmes (see e.g. WHO/ILO/ICN/PSI 2000, Afford 2003, Buchan 2006).

What now faces policy makers in Japan, Europe and other developed countries is a policy agenda with a core of common themes.

First, addressing supply side issues: improving recruitment, retention and return- getting, keeping and keeping in touch with these relatively scarce nurses. Research indicates that nurses are attracted to work and remain in work because of the opportunities to develop professionally, to gain autonomy, and to participate in decision making, while being fairly rewarded (see e.g. Buchan & Calman 2006). Factors related to work environment can be crucial, and there is some evidence that a decentralised style of management, flexible employment opportunities, and access to continuing professional development can improve both the retention of nursing staff and patient care (see e.g. Aiken et al. 2008). Some countries also have scope to widen the recruitment base by opening out access routes into nursing for a broader range of recruits, including mature entrants, entrants from ethnic minorities, and entrants who have vocational qualifications or work-based experience to compensate for fewer conventional academic qualifications. ‘Returners’ can also be attracted back into the profession. Most countries have relatively large pools of former nurses with the necessary qualifications to re-enter nursing.

One aspect of recruitment that requires careful consideration because of its potential impact is active international recruitment – where an organisation or system in one country actively recruits nurses from another country. This has been growing feature of global nursing labour markets, as developed countries exploit ‘push’ factors, which make some nurses in developing countries willing to cross national boundaries (see WHO 2006). These factors include relatively low pay, poor career structures, lack of opportunities for further education, and in some countries, the threat of violence. The danger is that this action may just displace the shortage to another country, which may be less resourced to deal with it. There is growing debate about how countries can be more effective at addressing issues of ‘self-sufficiency’ in relation to producing sufficient nurses and other health professionals to meet their own needs (Aiken et al. 2007, Little & Buchan 2007).

Second, dealing with demand side challenges (Buchan 2006). The policy interventions highlighted above address supply side issues. For sustainable solutions, other interventions will also be needed which focus also on the demand side. These should be based on the recognition that health care is labour intensive and that available nursing resources must be used effectively. As noted earlier, shortage is not just about numbers, but about how the health system functions to enable nurses to use their skills effectively.

Many countries need to enhance and align their workforce planning capacity across occupations and disciplines to identify the skills and roles needed to meet identified service needs. This is partly about longer term alignment between education supply, and funded demand. It is also about improving day-to-day matching of nurse staffing with workload. Flexibility should be about using working patterns that are efficient, but which also support nurses in maintaining a balance between their work and personal life.

Another critical area for policy intervention is to achieve effective skill mix-through clarity of roles and a better balance of registered nurses, physicians, other health professionals, and support workers. The evidence base on skill mix is developing, and many studies highlight the scope for effective deployment of clinical nurse specialists and nurse practitioners in advanced roles.

As noted earlier, the main challenge for policy makers is not to identify isolated or ‘one-off’ interventions to deal with nursing shortages, it is to develop a co-ordinated package of policies that provide a long term and sustainable solution.

Conclusions

There is no single universal definition or measure of nursing shortages, but clear evidence of inadequate nursing resources in many countries, and evidence of inadequate use of available nursing resources in many more. The policies that can make a difference are well known, if inadequately tested in their implementation. In examining the context in which nursing shortages exist and persist, Buchan has noted: ‘Nursing shortages are a health system problem, which undermines health system effectiveness and requires health system solutions. Until this is understood, and we make better use of the available evidence, we are doomed to endlessly repeat a cycle of inadequate, uncoordinated, obsolete and often inappropriate policy responses’ (Buchan 2006, p. 458). The other papers in this issue of Journal of Clinical Nursing examine specific issues of nursing workforce employment and deployment. They are a contribution to an improved evidence base on this critical issue.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge financial support from Grant-in-aid for Scientific Research (B: principal investigator Yoshifumi Nakata) and from The Japan Society of Promotion of Science Grant for International Collaborative Research (principal investigator Yoshifumi Nakata).

Footnotes

Contributions

Study design, data collection and analysis and manuscript preparation: JB, LA.

Contributor Information

James Buchan, Queen Margaret University, Queen Margaret University Drive, Edinburgh, UK.

Linda Aiken, Center for Health Outcomes and Policy Research, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

References

- Afford CW. Geneva: International Labour Organsiations (ILO); Corrosive Reform: Failing Health Systems in Eastern Europe. 2003

- Aiken L, Clarke S, Sloane D, Sochalski J, Busse R. Nurses’ reports of hospital quality of care and working conditions in five countries. Health Affairs. 2001;20:43–53. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.3.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Lake ET, Silber JH, Sochalski J. Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. Journal of American Medical Association. 2002a;288:1987–1993. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.16.1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken L, Clarke S, Sloane D. Hospital staffing, organizational support, and quality of care: cross-national findings. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2002b;14:5–13. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/14.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken L, Pittman P, Buchan J. International nurse migration. Health Services Research. 2007;42(Part II) doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00713.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Lake ET, Cheney T. Effects of hospital care environment on patient mortality and nurse outcomes. Journal of Nursing Administration. 2008;38:223–229. doi: 10.1097/01.NNA.0000312773.42352.d7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand S, Barnighausen T. Human resources and health outcomes: cross country econometric study. Lancet. 2004;364:1603–1609. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17313-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Australian Resource Centre for Hospital Innovations (ARCHI) Safe Staffing and Patient Safety Literature Review. Waratah: ARCHI; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Buchan J. Nursing shortages and human resource planning. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 1994;31:143–154. doi: 10.1016/0020-7489(94)90016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchan J. Planning for change: developing a policy framework for nursing labour markets. International Nursing Review. 2000;47:199–207. doi: 10.1046/j.1466-7657.2000.00047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchan J. Global nursing shortages. British Medical Journal. 2002;324:751–752. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7340.751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchan J. What difference does (‘good’) HRM make? Human Resources for Health. 2004;2:6. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-2-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchan J. Evidence of nursing shortages or a shortage of evidence? Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2006;56:457–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04072_2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchan J, Calman L. [accessed 22 February 2008];Geneva: International Council of Nurses; The Global Shortage of Registered Nurses: An Overview of Issues and Actions. 2006 http://www.icn.ch/global/shortage.pdf.

- Canadian Institute of Health Information (CIHI) Canada: Canadian Institute of Health Information; Bringing the Future in Focus: Projecting RN Retirement in Canada. 2003

- Friss L. Nursing studies laid end to end. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 1994;19:597–631. doi: 10.1215/03616878-19-3-597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodin H. The nursing shortage in the United Sates of America: an integrative review of the literature. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2003;43:335–350. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02722_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegney D, McCarthy A, Rogers-Clarke C, Gorman D. Why nurses are attracted to rural and remote practice. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2002;10:178–186. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1584.2002.00447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- High Level Forum on the Health MDGs. [accessed 22 February 2008];Geneva: High Level Forum; Summary of Discussions and Agreed Action Points. 2004 Available at: http://www.who.int/hdp/en/summary.pdf.

- Hossain B, Begum K. Survey of the existing health workforce of the Ministry of Health Bangladesh. Human Resources Development Journal (HRDJ) 1998;2:109–116. [Google Scholar]

- International Council of Nurses (ICN) Geneva: ICN; Press release: The Time for a UN Agency for Women is Now Says the International Council of Nurses. 2007 March 5;

- James D, Fineberg N, Shah A, Priest R. An increase in violence on an acute psychiatric ward: a study of associated factors. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1990;156:846–852. doi: 10.1192/bjp.156.6.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint Learning Initiative. [accessed 22 February 2008];JLI, Harvard University; Human Resources for Health: Overcoming the Crisis. 2004 Available at: http://www.healthgap.org/camp/hcw_docs/JLI_exec_summary.pdf.

- Kane RL, Shamliyan TA, Mueller C, Duval S, Wilt TJ. The association of registered nurse staffing levels and patient outcomes: systematic review and meta analysis. Medical Care. 2007;45:1195–1204. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181468ca3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovner C, Gergen J. Nurse staffing levels and adverse events following surgery in US hospitals. Image: Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1998;30:315–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little L, Buchan J. [accessed 22 February 2008];Geneva: International Centre on Nurse Migration and the International Centre for Human Resources in Nursing. International Council of Nurses; Nursing Self Sufficiency/Sustainability in the Global Context. 2007 Available at: http://www.intlnursemigration.org/download/SelfSufficiency_EURO.pdf.

- National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. Washington DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Health Professions; Toward a Method for Identifying Facilities and Communities with Shortages of Nurses, Summary Report. 2007

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Paris: OECD; Towards High Performing Health Systems. 2004:59.

- Rafferty A, Clarke S, Coles J, Ball J, James P, McKee M, Aiken L. Outcomes of variation in hospital nurse staffing in English hospitals: cross-sectional analysis of survey data and discharge records. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2007;44:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson R, Thompson M. London: Institute of Personnel and Development; The Impact of People Management Practices on Business Performance: A Literature Review. 1999

- Simoens S, Villeneuve M, Hurst J. Tackling Nurse Shortages in OECD countries. Paris: OECD; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Speybroeck N, Kinfu Y, DalPoz M, Evans D. Geneva: Background Paper prepared for the World Health Report 2006 WHO; Reassessing the Relationship between Human Resources for Health, Intervention Coverage and Health Outcomes. 2006

- Stanton M. AHRQ, MD, USA: Agency for Health Research and Quality. Research into Action, Issue 14; Hospital Nurse Staffing and Quality of Care. 2004

- Wharrad H, Robinson J. The global distribution of physicians and nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1999;30:109–121. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.01056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation (WHO) Geneva: WHO; A Toolkit for Planning Training and Management. 2001

- World Health Organisation (WHO) [accessed 22 February 2008];Geneva: WHO; The World Health Report 2006 – Working Together for Health. 2006 Available at: http://www.who.int/whr/2006/en/

- World Health Organisation (WHO), International Labour Office (ILO), International Council of Nurses (ICN), Public Services International (PSI) [accessed 22 February 2008];Public Service Reforms and Their Impact on Health Sector Personnel. 2000 Available at: http://www.icn.ch/en/who_eid_osd_01.2.en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Zurn P, Dalpoz M, Stilwell B, Adams O. Geneva: WHO; Imbalances in the Health Workforce. 2002