Abstract

Background

Every 5 years for the past several decades, the USDHHS and the U.S. Department of Agriculture have issued and updated the Dietary Guidelines for Americans which form the basis of Federal nutrition policy and have shown remarkable consistency across various editions among the major themes.

Purpose

This paper examines whether the U.S. food supply is sufficiently balanced to provide the recommended proportions of various foods and nutrients per the amount of energy, whether this balance has shifted over time, and which areas of the food supply may have changed more than others.

Methods

The Healthy Eating Index-2005 (HEI-2005) was used to measure the dietary quality of the U.S. food supply, from 1970 to 2007. Sources of data were the USDA's Food Availability Data, Loss-Adjusted Food Availability Data, and Nutrient Availability Data, and the U.S. Salt Institute's data on salt sold for human consumption.

Results

Total HEI-2005 scores improved by about 10 points between 1970 and 2007, but they never achieved even 60 points on a scale from 0 to 100. Although meats and total grains were supplied generally in recommended proportions, total vegetables, total fruit, whole fruit, and milk were supplied in sub-optimal proportions that changed very little over time. Saturated fat, sodium, and calories from solid fat, alcoholic beverages and added sugars were supplied in varying degrees of unhealthy abundance over the years. Supplies of dark-green/orange vegetables and legumes and whole grains were entirely insufficient relative to recommendations, with virtually no change over time.

Conclusions

Deliberate efforts on the part of policymakers, agriculture and the food industry are necessary to provide a supply of foods consistent with nutrition recommendations and make healthy choices available to all.

Introduction

The decade of the 1970s might be considered the advent of the modern era of dietary guidance. Following the landmark 1969 White House Conference on Food, Nutrition and Health that addressed the problems of hunger and malnutrition, the 1970s ushered in a period of concern for balance and moderation, in addition to nutritional adequacy.1

Since 1980, the USDHHS and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) have issued and updated the Dietary Guidelines for Americans every 5 years.2–7 The Guidelines are the cornerstone of Federal nutrition policy and form the basis of Federal nutrition education and information programs.8 Since their inception, the Guidelines have shown remarkable consistency across the various editions in their major themes: increase fruits, vegetables, and whole grains; restrict energy, sodium, solid fats, and added sugars; and moderate intake of alcohol.7,9

Throughout this period, the focus of Federal nutrition policy has been to assist consumers in making informed, healthy choices through education campaigns focused on the individual. However, substantial behavioral research data are accumulating that suggest beneficial changes are not achieved and maintained without concomitant changes in policies and environments to support them.10 Although individuals must ultimately choose whether or not to consume a healthy diet, it is increasingly clear that in many instances, individuals have little control over their food choices.10 For example, local environments in which people live and work may not provide healthy food options. At a macro level, the country's aggregate food supply may not deliver the requisite mix of foods to afford all Americans a balanced and healthy diet.

The purpose of this paper is to examine the extent to which the U.S. food supply conforms to Federal dietary guidance. Specifically, it examines whether the food supply is sufficiently balanced to provide the recommended amounts of various foods and nutrients per amount of energy—that is, the recommended proportions—and whether this balance has shifted over time. It focuses on the distribution of major categories within the food supply, rather than the overall amount of food produced—a construct here termed “dietary quality.” Further, it provides special attention to the recurring themes in dietary guidance since the 1970s. Finally, the paper assesses whether some areas of the food supply have changed more than others.

Methods

We used the Healthy Eating Index-2005 (HEI-2005) to measure the dietary quality of the U.S. food supply, from 1970 to 2007.11–13 The HEI-2005 was developed to monitor American diets and evaluate their concordance with the 2005 Guidelines. This measure is particularly suited to this paper's purpose for several reasons. First, it is density-based, meaning it evaluates the degree to which the food supply provides the recommended amount of foods and nutrients per 1000 calories. As a result, it ascertains quality irrespective of the varying energy needs in the population. Second, each component of the HEI-2005 captures a distinct aspect of diet quality, corresponding to the various themes in dietary guidance. Therefore, the HEI-2005 component scores can indicate whether some sector of the food supply is responding positively to recommendations while another is not.

Healthy Eating Index-2005

The HEI-2005 has 12 components, each with its own standards for scoring.13 To derive the scores, data were first obtained on the amounts of total fruits; whole fruits (fruit other than juice); total vegetables; dark-green vegetables, orange vegetables and legumes; total grains; whole grains; milk, yogurt, cheese, and soy beverages; meat, poultry, fish, eggs, beans and nuts; oils; saturated fat; sodium; total energy; and calories from solid fats, alcoholic beverages, and added sugars in the U.S. food supply. Pertinent ratios were then derived of the various foods and nutrients to energy, and each component was scored using the relevant standard.

For all HEI-2005 components, higher scores reflect higher quality, and for most components, higher relative amounts in the food supply result in higher scores. However, for three components—Saturated Fat; Sodium; and Calories from Solid Fats, Alcoholic beverages, and Added Sugars (SoFAAS)—lower amounts result in higher scores because lower intakes are more desirable. Further information regarding the development of the HEI-2005 and how to derive scores can be obtained from previous publications.11,13

The minimum score for each component is 0, and the maximum score varies somewhat in order to weight the components when deriving the total score. Milk, meat and beans, oils, saturated fat, and sodium each have a maximum value of 10 points. Fruit, vegetables, and grains each have two components (total and a subgroup) that get 5 points apiece, so each of these three food groups is allotted a total of 10 points. The Calories from SoFAAS component is weighted twice as heavily as any other (20 points) because the effect of solid fats, alcoholic beverages, and added sugars in the diet is twofold: they add energy without adding much in the way of nutrients and they displace nutrient-dense foods in the diet.

Food Supply Data

Data on the U.S. food supply signify the amount of food and nutrients available for human consumption in the country. The data are obtained by tracking flows of individual agricultural commodities through domestic marketing channels and are available from several sources. Food Availability Data are the original source, reported in terms of amounts per person per year. They overstate the availability of most foods because they capture substantial quantities lost to waste and spoilage.14 Loss-adjusted Food Availability Data account for such losses and are reported in terms of daily per capita amounts consistent with current guidance (for example, cups/person/day).15 Nutrient Availability Data provide the estimated nutrient content of the unadjusted Food Availability Data.16 Notably, they do not include the sodium from salt added to foods, except canned vegetables and cheese.17 However, data on salt sold for human nutrition (including that used in processing, cooking and at the table) are available through the U.S. Salt Institute.18

Using the above-mentioned sources of data (primarily the Loss-adjusted Food Availability Data, the U.S. Salt Institute data, and adjustments to data from the other sources as appropriate), procedures were followed for deriving HEI-2005 scores for the U.S. food supply that are outlined in a companion publication,13 for all years between 1970 and 2007. Saturated fat and sodium values were not available in the Nutrient Availability Data for 2007, so the 2006 values for each nutrient were used as a proxy, as recommended (H Hiza, USDA, personal communication, July 23 2009).

Results

Figures 1–3 show trends in the various HEI-2005 component scores, with the Y-axis on each scaled according to the optimal score for the relevant component(s). Total HEI-2005 scores improved by about 10 points between 1970 and 2007, but remained below 60 points on a scale from 0 to 100.

Figure 1. Quality of the US food supply with regard to fruits, vegetables, and grains, 1970-2007.

Figure 3. Quality of the US food supply with regard to calories from solid fats, alcoholic beverages, and added sugars (SoFAAS) and actual calories from each, 1970-2007.

Figure 1 displays the quality of the U.S. food supply with regard to fruits, vegetables and grains, from 1970–2007, in terms of HEI-2005 component scores. These components are all measured on a scale from 0 (which indicates total absence in the food supply) to 5 (which indicates presence in at least recommended amounts). The score for Total Grains was relatively high (4 or greater) across the time period, and increased during the 1980s and 1990s. The score for Whole Grains, on the other hand, was consistently less than 1.5 and even declined over the years.

The Dark-Green Vegetables, Orange Vegetables and Legumes component also scored consistently low (from 0.9 to 1.6), although it improved over time. Total Vegetables, Whole Fruit, and Total Fruit each received scores of around 2 to 3—suggesting the food supply contained only about half the recommended amount—for all years and changed little from 1970 to 2007.

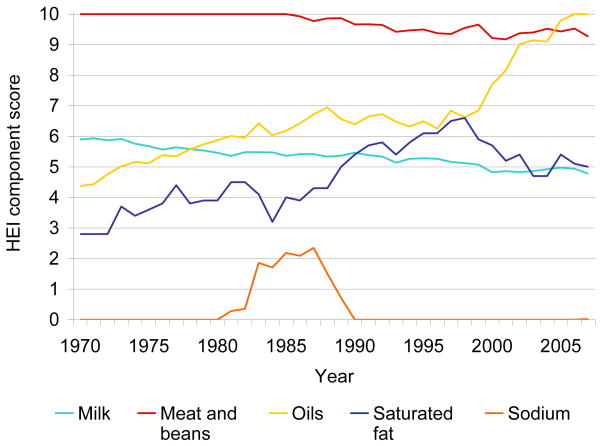

The trends in HEI component scores for milk, meat and beans, oils, saturated fat, and sodium are shown in Figure 2. These components are measured on a scale from 0 to 10. A score of 10. In the case of milk, and meat and bones, a score of 10 indicates the food supply contains at least the recommended amount, whereas a score of 5 indicates half the recommended amount. The score for the Meat and Beans component has been near optimal (between 9 and 10) consistently over time. The Milk component has fared less well, scoring around 5 to 6, and has been declining over time.

Figure 2. Quality of the US food supply with regard to meat & beans, milk, oils, saturated fat, and sodium 1970-2007.

In the case of both the oils and saturated fat components, higher scores indicate greater dietary quality. However, the Oils score rises with increasing amounts of oils in the food supply (up to a score of 10), because unsaturated fats are desirable (up to a point), whereas the Saturated Fat score rises with decreasing amounts in the food supply. The supply of oils, and consequently the Oils score, rose between 1970 and the mid-1980s then leveled off through the 1990s. Saturated Fat fluctuated between 1970 and 1985; then, from 1985 to the late 1990s, supply decreased and the score climbed from 4.0 to 6.6. Since the late 1990s, supplies of both oils and saturated fat have risen, causing a rise in the Oils component score (to 10.0 in 2007) and a fall in the Saturated Fat component score (to 5.0 in 2007). This indicates there have been more fats and oils in the food supply in the past decade (1990s) compared to the preceding one.

The Sodium component rises with decreasing amounts of sodium per 1000 calories in the food supply. A score of 10 indicates the sodium content of the food supply is .7 gm/1000 kcal, on par with the Food and Nutrition Board's Adequate Intake and the Guidelines' recommendation for sodium-sensitive groups.11,19 A score of 8 equates to 1.1 gm sodium/1000 kcal, commensurate with the Tolerable Upper Level (UL) of Intake and the Guidelines' recommendation for the general population. Any score below 8 indicates amounts above the UL. The score was at the lowest possible point for nearly all years, with only a minimal, transient rise in the mid- to late-1980s.

The Calories from Solid Fat, Alcoholic beverages, and Added Sugars (SoFAAS) is scaled from 0 to 20, and the score rises with decreasing percentages of energy from SoFAAS in the food supply (Figure 3). A score of 20 indicates that calories from SoFAAS are ≤20% of total calories—a level corresponding to discretionary calorie allowances exemplified in the Guidelines—and a score of 10 indicates that these “empty calories” represent 35% of total calories. The SoFAAS score fluctuated between 9 and 11, from 1970 to the early part of the 1990s, but ticked upward in the past few years. Overlaid on Figure 5 are the absolute levels of energy from solid fat, alcohol, and added sugars in the food supply over time, to see the relative contribution of each. Across all years, added sugars make up the greatest portion of SoFAAS calories, followed by solid fat and alcohol. Calories from added sugars rose steadily in the food supply from 1970 to about 2000, but have dipped somewhat since then. Calories from solid fat fluctuated moderately over the years, while calories from alcohol–the smallest contributor to SoFAAS—remained relatively flat.

Discussion

This analysis is the first to examine trends in the U.S. food supply using an index of dietary quality. Although the HEI-2005 was designed to measure adherence to the 2005 Guidelines, those Guidelines deviate only modestly in degree—and not in direction—from past editions. According to this analysis, the country's food supply has been failing to provide diets consistent with Federal recommendations on a number of key components for the past several decades. Specifically, while meats and total grains have been supplied generally in recommended proportions; total vegetables, total fruit, whole fruit, and milk/milk alternates each have been supplied at roughly half the recommended level, proportions that changed very little over time; and saturated fat, sodium and calories from SoFAAS have been supplied in varying degrees of unhealthy abundance over the years. Supplies of dark-green vegetables, orange vegetables, legumes and whole grains have been entirely insufficient relative to recommendations, with virtually no change over time.

There are limitations to the food supply data in their ability to account precisely for certain of the HEI-2005 components.13 However, all of the issues are assumed to represent minor limitations which would affect scores only slightly one way or the other.

For the purposes of this study, the advantages of the data are several. First, the food supply data provide a valuable lens through which to examine how well the macro food environment in this country conforms to the recommendations embodied in the Guidelines. Second, the generally clean separation among commodities makes analysis relatively simple (compared to, say, reported individual-level intakes). And finally, because the methods used to derive the food supply data are employed consistently over time, they are ideal for assessing trends.

Previous analyses of food supply data in relation to dietary guidance, using absolute amounts rather than an index measure, derived similar conclusions.20–25 Comparing food supply data to USDA's Food Guide Pyramid recommendations up through the mid 1990s, Young and Kantor found particularly large discrepancies for added sugars, fats and oils, fruits, and certain vegetables—notably dark-green vegetables, orange vegetables and legumes.25 They also identified the agricultural implications of addressing these imbalances, which included extensive shifts in production, trade and prices. Other analyses also have projected dramatic agricultural adjustments to bring the food supply into conformance with Federal dietary guidance.21–24

Moreover, the results of the current analysis are consistent with recent assessments of individual diets in relation to the Guidelines.26–28 Guenther et al applied the HEI-2005 to data from the 2003–04 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.26 They found average diets to score 57.5 overall, similar to what was found in the current study for the food supply during the same period. Regarding the components, individual diets scored somewhat lower than the food supply on Oils and Calories from SoFAAS and higher on Milk, Saturated Fat, and Sodium (although salt added at the table was not ascertained in that analysis). Recent analyses of the distribution of usual intake of various foods in the U.S. population noted that, across nearly all age/gender groups, 95% of the population is not consuming enough dark-green vegetables, orange vegetables, legumes or whole grains, and 95% of adult women are not consuming the recommended amounts of milk.27 A quarter of the U.S. population consumes more than 1000 kcal per day from added sugars, solid fats, and alcoholic beverages.28

The HEI-2005 is a measure of diet quality, not quantity, which means it cannot ascertain whether the food supply provides the right amount of energy for the population. However, the rates of obesity and overweight in this country certainly indicate there is an overabundance of energy available for consumption relative to the amount the population expends. Sacks and Swinburn have estimated this to be 350 calories per day for children and 500 calories per day for adults.29 Although this estimate is the subject of some debate, 500 kcal/person/day is roughly the size of the increase in energy available in the loss-adjusted food supply between 1970 and 2007, a period in which obesity rates doubled for adults and tripled for children.30

Calories from SoFAAS are most dispensable, as SoFAAS provide very little else nutritionally. But simply removing SoFAAS is not sufficient to produce a food supply supportive of the dietary recommendations. In order for the loss-adjusted food supply to decrease by 500 kcal/person/day and achieve optimal HEI-2005 scores, the following changes would be necessary:

Calories from SoFAAS would need to decrease by 61%, including about 120 kcal of solid fat. This would reduce the overall energy available, make room for increased energy to be supplied by added fruits, vegetables, and milk, and reduce both saturated fat and calories from SoFAAS.

The supply of fruit would need to more than double, with most of that being whole fruit rather than juice.

The supply of vegetables would need to increase by 70%, with nearly all of the increase coming from dark-green vegetables, orange vegetables and legumes.

Total grain supply could remain about constant, but four times as much of the grain should remain as whole grain, not be refined.

Milk supply would need to increase about 70%, but virtually all of the increase would need to come from fat-reduced milk, milk products or fortified soy beverages

Salt added to foods (in processing, cooking and at the table) would need to decrease by over half.

Although some aspects of the food supply—notably salt, fat, and added sugars—may have shifted in response to dietary recommendations, albeit temporarily, others have changed hardly at all. The supply of salt declined slightly for a few years, only to increase again. Saturated fat (and consequently, calories from solid fat) in the food supply fluctuated over the years, sometimes decreasing only when calories from added sugars were increasing. These trends may be the result of issues that receive more or less attention over time. Processed foods are major sources of salt, fat and sugars in the U.S. diet,33,34 because these ingredients contribute to the taste, mouth feel, and shelf life of foods. The food industry responds to food fads by altering the relative amounts of these ingredients in an effort to market the “healthfulness” of their products, but sometimes they simply replace one ingredient with another. For example, low-fat cookies and other sweets were popular in the 1990s, but these “guilt-free” alternatives were frequently no lower in calories than their full-fat counterparts, because the fat was replaced with added sugars.35

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans serve as a statement of Federal nutrition policy while focusing almost exclusively on educational activities to guide consumers to make healthy choices. Although the Guidelines have been available for several decades, there is no clear evidence they have improved the U.S. diet. A wealth of behavioral research suggests this may be because educating individuals is not sufficient to produce change. Rather, a comprehensive approach involving action at all levels of the socio-ecologic spectrum is needed,10 including structural changes in the food supply. Such an approach was recommended to address inactivity in the government's first-ever Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans released last year.37

The amounts and types of food available in the nation's food supply data reflect the economic balance among forces that both “push” and “pull” foods through distribution channels. Consumer demand exerts the “pull,” and agriculture and economic policies and industrial marketing efforts provide the “push.” Indeed, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the purposes of the Loss-Adjusted Food Supply Data are to monitor the potential of the food supply to meet the nutritional needs of the U.S. populations, translate nutrition goals for Americans into food production and supply goals, and evaluate the effects of marketing practices over time.15 When applied to those purposes, as in this analysis, the data suggest it may be unrealistic to expect a groundswell in consumer demand that would be sufficient to “pull” a healthy food supply through distribution channels. Rather, deliberate efforts on the part of policymakers and industry may be necessary to provide a supply of foods consistent with nutrition recommendations and make healthy choices available to all.10

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Lisa Kahle, Information Management Systems, for her outstanding programming support.

Footnotes

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.McGinnis JM, Nestle M. The Surgeon General's report on nutrition and health: policy implications and implementation strategies. Am J Clin Nutr. 1989;49:23–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/49.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.USDHHS and U.S. Department of Agriculture. Home and Garden Bulletin. No. 232. Washington DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; Feb, 1980. Nutrition and your health: Dietary guidelines for Americans. [Google Scholar]

- 3.USDHHS and U.S. Department of Agriculture. Home and Garden Bulletin. Second. No. 232. Washington DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; Aug, 1985. Nutrition and your health: Dietary guidelines for Americans. [Google Scholar]

- 4.USDHHS and U.S. Department of Agriculture. Home and Garden Bulletin. Third. No. 232. Washington DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; Nov, 1990. Nutrition and your health: Dietary guidelines for Americans. [Google Scholar]

- 5.USDHHS and U.S. Department of Agriculture. Home and Garden Bulletin. Fourth. No. 232. Washington DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; Dec, 1995. Nutrition and your health: Dietary guidelines for Americans. [Google Scholar]

- 6.USDHHS and U.S Department of Agriculture. Home and Garden Bulletin. Fifth. No. 232. Washington DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2000. Nutrition and your health: Dietary guidelines for Americans. [Google Scholar]

- 7.USDHHS and U.S. Department of Agriculture. Home and Garden Bulletin. Sixth. No. 232. Washington DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; Jan, 2005. Dietary Guidelines for Americans. [Google Scholar]

- 8.U.S. Department of Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans. http://www.cnpp.usda.gov/dietaryguidelines.htm.

- 9.Ballard-Barbash R. Designing surveillance systems to address emerging issues in diet and health. J Nutr. 2001;131:437S–439S. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.2.437S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lytle LA. Measuring the food environment: State of the science. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(4S):134–144. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guenther PM, Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM. Development of the Healthy Eating Index-2005. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108:1896–1901. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guenther PM, Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM, Reeve BB. Evaluation of the Healthy Eating Index-2005. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108:1854–1864. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reedy J, Bosire C, Krebs-Smith SM. Evaluating the food environment: Application of the Healthy Eating Index-2005 to food service establishments and the U.S. food supply. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.01.015. In preparation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Economic Research Service. U.S. Department of Agriculture Data: Food availability: Documentation. http://www.ers.usda.gov/Data/FoodConsumption/FoodAvailDoc.htm.

- 15.Economic Research Service. U.S. Department of Agriculture Data: Loss-adjusted food availability: Documentation. http://www.ers.usda.gov/Data/FoodConsumption/FoodGuideDoc.htm.

- 16.Economic Research Service. U.S. Department of Agriculture Data: Nutrient availability: Documentation. http://www.ers.usda.gov/Data/FoodConsumption/NutrientAvailDoc.htm.

- 17.Hiza HAB, Bente L, Fungwe T. Home Economics Research Report. No. 58. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion; Mar, 2008. Nutrient content of the U.S. food supply, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salt Institute. U.S. salt production/sales. Facts and figures for human nutrition. http://www.saltinstitute.org.

- 19.IOM, Food and Nutrition Board. Dietary reference intakes for water, potassium, sodium, chloride, and sulfate. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wells HF, Buzby JC. Economic Information, Bulletin No. 33. Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture; Washington DC: Mar, 2008. Dietary assessment of major trends in U.S. food consumption, 1970–2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buzby JC, Wells HF, Vocke G. Economic Research Report. No. 31. Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture; Washington DC: Nov, 2006. Possible implications for U.S. agriculture from adoption of select dietary guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krebs-Smith SM, editor. J Nutr. 2SI. Vol. 131. 2001. The dietary guidelines: Surveillance issues and research needs; pp. 527S–535S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kantor LS. Agricultural Economic Report. No. 772. Food and Rural Economics Division, Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture; Washington DC: May, 1999. A dietary assessment of the U.S. food supply: Comparing per capita food consumption with Food Guide Pyramid serving recommendations. [Google Scholar]

- 24.McNamara PE, Ranney CK, Kantor LS, Krebs-Smith SM. The gap between food intakes and the Pyramid recommendations: Measurement and food system ramifications. Food Policy. 1999;24:117–133. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Young CE, Kantor LS. Agricultural Economic Report. No. 779. Market and Trade Economics Division and Food and Rural Economics Division, Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture; Washington DC: Dec, 1998. Moving toward the Food Guide Pyramid: Implications for U.S. agriculture. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guenther PM, Juan WY, Lino M, Hiza HA, Fungwe T, Lucas R. Nutrition Insight. Vol. 42. Alexandria VA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion; Dec, 2008. Diet quality of low-income and higher-income Americans in 2003–04 as measured by the Healthy Eating Index-2005. [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Cancer Institute. Usual dietary intakes: Food intakes, U.S. Population, 2001–04. http://riskfactor.cancer.gov/diet/usualintakes/pop/

- 28.National Cancer Institute. Usual energy intake from solid fats, alcoholic beverages and added sugars (SoFAAS) (kcal) http://riskfactor.cancer.gov/diet/usualintakes/sofaas.html.

- 29.Sacks G, Swinburn B, Ravussin E. Combining biological, epidemiological, and food supply data to demonstrate that increased energy intake alone virtually explains the obesity epidemic. U.S. International Conference on Diet and Activity Methods; June 2009; Washington DC. abstract. http://www.icdam.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 30.CDC, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Prevalence of Overweight Among Adults: U.S., 2003–2004. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/pubs/pubd/hestats/overweight/overwght_adult_03.htm.

- 31.CDC, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Prevalence of Overweight Among Children and Adolescents: U.S., 2003–2004. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/pubs/pubd/hestats/overweight/overwght_child_03.htm.

- 32.CL, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. High body mass index for age among U.S. children and adolescents, 2003–06. JAMA. 2008;299(20):2401–2405. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.20.2401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bachman JL, Reedy J, Subar AF, Krebs-Smith SM. Sources of food group intakes among the U.S. population, 2001–02. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108:804–814. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bosire C, Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM. Sources of energy and selected nutrient intakes among the U S population, 2005–06: A report prepared for the 2010 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. National Cancer Institute; Apr, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 35.The Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy. The new skinny on fats. Tufts University Health & Nutrition Letter. 2009 July;27(5):4–5. [Google Scholar]

- 36.USDHHS. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. ODPHP Publication No U0036. 2008 www.health.gov/paguidelines.