Abstract

Perception of one's body is related not only to the physical appearance of the body, but also to the neural representation of the body. The brain contains many body maps that systematically differ between right- and left-handed people. In general, the cortical representations of the right arm and right hand tend to be of greater area in the left hemisphere than in the right hemisphere for right-handed people, whereas these cortical representations tend to be symmetrical across hemispheres for left-handers. We took advantage of these naturally occurring differences, and examined perceived arm length in right- and left-handed people. When looking at each arm and hand individually, right-handed participants perceived their right arms and right hands to be longer than their left arms and left hands, whereas left-handed participants perceived both arms accurately. These experiments reveal a possible relationship between implicit body maps in the brain and conscious perception of the body.

When people look at their bodies, what they see is likely influenced by the neural representation of the body in the cortex, and is not solely due to the way the body appears physically. Right-handed individuals have asymmetric neural representations of the body—there is typically more cortical area and higher neural activation associated with the right arm and hand than with the left arm and hand—whereas left-handed individuals usually have near-symmetrical cortical body representations (Kim et al., 1993; Sörös et al., 1999; Zilles et al., 1997). Extending this finding, the current studies assessed whether asymmetries in cortical representation would be related to the perceived size of the associated body part. To obtain disparities in the sizes of cortical areas, we took advantage of naturally occurring individual differences associated with handedness. If the extent of neural body representation is predictive of the perceived size of the body, then right-handed people should perceive their right arm to be longer than their left arm, and left-handed people should perceive the right and left arms as being the same length. Among right-handed participants, we found these anticipated asymmetries in perceived arm length and hand size, as well as in perceived reaching ability and grasping ability. In contrast, perceived arm length and anticipated reach were symmetrical for left-handed participants, paralleling the symmetries in their cortical representations. These findings provide compelling evidence for the hypothesis that neural body representations are reflected in how people visually perceive their bodies.

Neuroimaging studies have uncovered hemispheric asymmetries in cortical areas associated with body representation in right-handed people, but not in left-handed people. Right-handed individuals have a greater cortical surface area in their left sensory cortex and more activation in their left primary motor and sensory cortices for contralateral movements than they have in the corresponding areas of their right hemisphere. In contrast, left-handed individuals appear to have near-symmetrical surface areas and activation (Amunts et al., 1996; Kawashima, Kentaro, Kazunori, & Hiroshi, 1997; Kim et al., 1993; Zilles et al., 1997).

Electroencephalography (EEG) studies have reported that right-handers show greater neural activation and a larger area representing the hand in the left somatosensory cortex than in the right somatosensory cortex when engaging in a motor task (Buchner, Ludwig, Waberski, Wilmes, & Ferbert, 1995; Jung et al., 2003). Hemispheric asymmetries have also been revealed in areas of the parietal lobe associated with visuomotor processing. The left (but not the right) inferior parietal lobule has been implicated in updating body representation in right-handed individuals (Devlin et al., 2002). Right-handed patients with optic ataxia due to damage to the left parietal lobe show deficits in reaching to stimuli in the right visual field and deficits in reaching with the right hand, whereas similar damage to the right parietal lobe results in a deficit only in reaching to the left visual field, suggesting an asymmetry in the body representation between the two hemispheres (Perenin & Vighetto, 1988).

The results of behavioral experiments parallel the neuroimaging data. Right-handed people tend to rely on their dominant hand more than left-handed people do. For example, when performing a natural grasping task, right-handed people use their right hand for 90% of the grasps, whereas left-handed people used the right and left hands equally often (Gonzalez, Whitwell, Morrissey, Ganel, & Goodale, 2007). Similarly, right-handed individuals perceive the distance to a tool as being further away if a tool's handle is oriented towards the nondominant hand than if the handle is oriented toward the dominant hand (Linkenauger, Witt, Stefanucci, Bakdash, & Proffitt, in press). This may be the result of the dominant hand being the default for actions in right-handed people. Left-handed people demonstrate symmetry in perceived distance regardless of grasp type, presumably because they frequently use both hands. There is compelling evidence for structural and functional asymmetries in right-handed people, whereas left-handers are more symmetrical in both regards. In the current experiments, we assessed whether these symmetry differences would be reflected in the visually perceived size of arms and hands.

Experiment 1: Handedness and Perception of Arm Length

/text/If the cortical representations of the arm affect perceived arm length, then right-handed people should perceive their left and right arms to be different lengths, because right-handed people have a larger representation of their right arm than of their left arm. In contrast, because left-handed people have nearly equal-sized cortical representations for their left and right arms, they should perceive the lengths of their right and left arms as similar. To test this notion, we asked right- and left-handed participants to indicate the perceived lengths of both their left arm and right arm.

Method

Participants

Fifteen right-handed (7 female and 8 male) and 15 left-handed (7 female and 8 male) University of Virginia students participated in Experiment 1. Handedness was assessed through self-report, which was consistent with the hand participants used to sign the consent form. Preferred writing hand is the best, single-item self-report measure of handedness (Rigal, 1992).1 All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision.

Design and Procedure

Participants were instructed to stand and extend their right or left arm to be perpendicular to their body and to place the fingers of their nonextended hand on the protrusion of their opposite shoulder, defined by the intersection of the clavicle and the humerus. Then, they estimated the length of the extended arm from this point on their shoulder to the end of their fingertips on their extended hand. Participants estimated arm length by instructing a researcher standing perpendicular to the extended arm to adjust a retractable tape measure horizontally so that the length of the tape matched the perceived length of the participant's arm. Participants could view the length of their arms while making the estimate (see Fig. 1). The tape measure was held so that the numbers faced the experimenter, so participants could not see or use the numbers to adjust their response. Next, participants' grip strength was assessed for each hand using a dynamometer. Then, participants estimated the length of their other arm. Arm order was counterbalanced across participants. Last, the actual lengths of the participants' arms were measured.

Fig. 1.

Photograph of a participant estimating the length of her left arm. The participant instructed the experimenter to increase or decrease the length of the visible portion of the back of a tape measure until she perceived this length to be the same length as her arm.

Results and Discussion

Arm-length estimates were assessed by calculating the ratio of perceived arm length to actual arm length. A repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with arm specified as a within-participants factor was used to compare the arm-length ratios between right- and left-handed participants. No main effect of arm was found, F(1, 28) = 1.37, prep = .67; however, as predicted, a significant interaction was found between arm and handedness, F(1, 28) = 4.74, prep = .90, ηp2 = .15. Separate one-tailed, paired-samples t tests for right- and left-handed participants revealed that right-handed participants underestimated the length of their left arm more than the length of their right arm, t(14) = 2.12, prep = .91. However, we did not find this difference for left-handed individuals, t(14) = 0.82, prep = .70 (see Fig. 2a). One-sample t tests were used to compare the ratios to a value of 1 (perfect accuracy) and revealed that right-handed participants were accurate in their perception of their right arm, t(14) = 0.85, prep = .50, but underestimated the length of their left arm, t(14) = 2.38, prep = .94, ηp2 = .29. Left-handed participants were accurate in estimating the lengths of both their right arms, prep = .75, and their left arms, prep = .50. Variability in the difference between the left-arm and right-arm estimates did not differ by handedness, prep = .52, which suggests that these differences were not due to increases in variability of the spectrum of left-handedness.

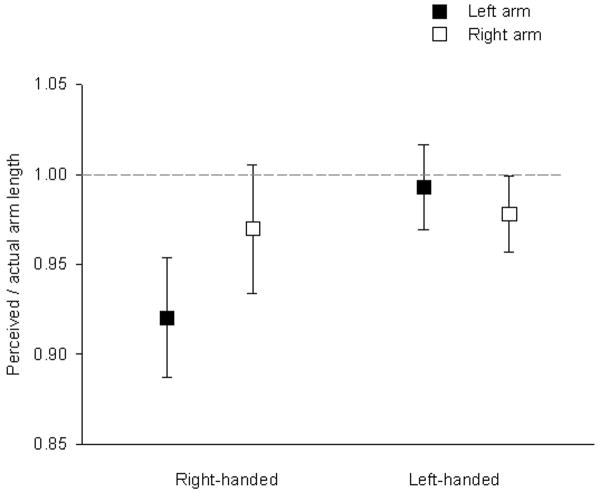

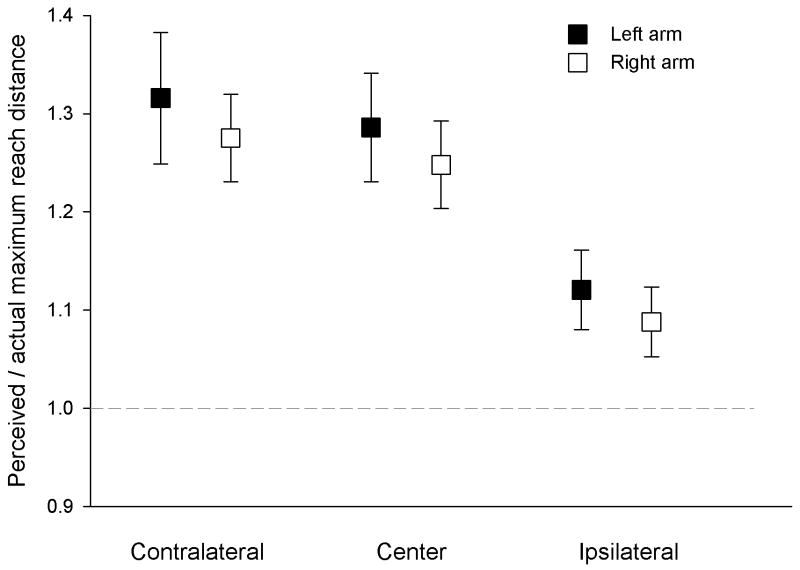

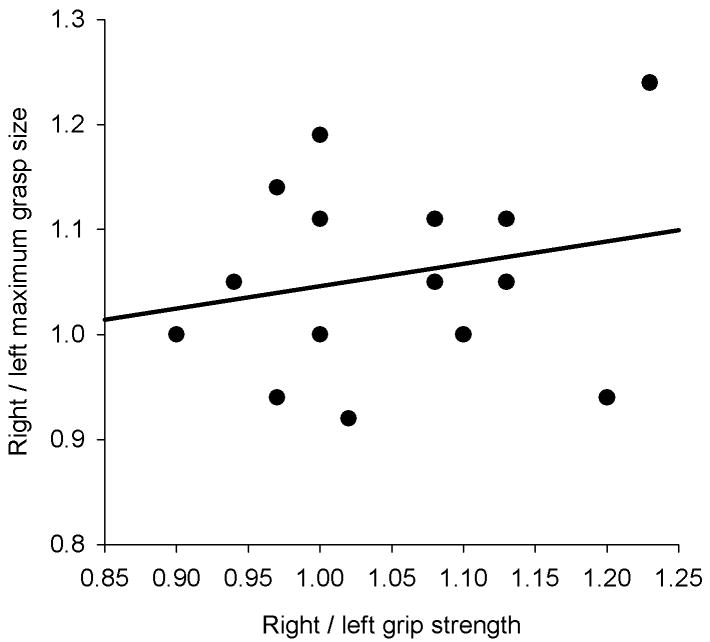

Fig. 2.

Results from Experiment 1: (a) ratio of perceived arm length to actual arm length as a function of handedness and (b) correlation between relative-strength ratio and symmetry in perceived arm length. In (a), data are plotted separately for the left and right arm. Error bars represent 1 SEM. The horizontal dashed line represents accurate perception. In (b), relative-strength ratios were computed as grip strength in the right hand divided by grip strength in the left hand, and symmetry in arm length was computed as perceived length of the right arm divided by perceived length of the left arm. The solid line represents linear regression of the data.

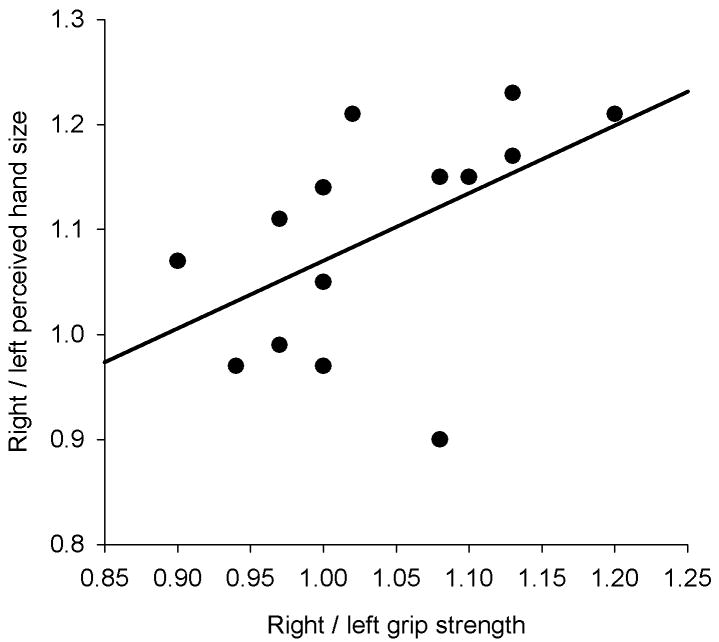

Given that sensory feedback is generally greater for body parts that engage in more activity (Hamilton & Pascual-Leone, 1998; Pantev, Engelien, Candia, & Elbert, 2001), and therefore these body parts require a larger somatosensory area, we hypothesized that perceived arm length would be related to the arm's strength. Relative-strength ratios were created by dividing participants' right-hand grip strength by their left-hand grip strength.2 Ratio scores greater than 1 indicated greater right-hand than left-hand strength, and ratio scores less than 1 indicated greater left-hand than right-hand strength. Relative hand strength significantly correlated with relative arm length (perceived length of right arm divided by perceived length of left arm), r = .44, prep = .91 (see Fig. 2b). Asymmetries in hand strength were positively related to asymmetries in perceived arm length.

Experiment 2: Handedness and Perceived Reach

With perceptual differences often come behavioral consequences. Given that right-handed people perceive their right arm as longer than their left arm, they should also anticipate that they can reach farther with their right arm than with their left arm. In this experiment, right- and left-handed participants estimated how far they could reach with their left and right arms.

Method

Participants

Fifteen right-handed (11 female and 4 male) and 15 left-handed (8 female and 7 male) University of Virginia students participated in Experiment 2. Handedness was assessed through self-report and by the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory (Oldfield, 1971; right-handed participants: M = 91.30, SD = 12.11; left-handed participants: M = −70.70, SD = 28.22). All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision.

Stimuli and Apparatus

Participants were seated on a chair at a uniformly colored table that measured 91.5 cm by 91.5 cm and was 74.5 cm tall. Participants' shirt backs were clamped to the back of the chair using binder clips to prevent forward lean. Participants sat at a close but comfortable distance to the table.

Design and Procedure

Participants estimated their reach with their right and left arms. The experimenter moved a white plastic chip from the opposite side of the table toward the participants. The participants informed the experimenter when they thought the chip was close enough that they could just grasp it with a specific arm without moving their shoulders from the back of the chair. The binder clips served as a constant reminder of this constraint. Participants were encouraged to instruct the experimenter to make adjustments to the position of the chip. Participants made three reachability estimates—one to a location that was contralateral (starting 30° from center moving toward center, away from the reaching arm), one that was ipsilateral (starting 30° from center moving toward the reaching arm), and one that was central. The three estimates were done first with one arm and then the other arm. The order of the three estimates was randomized, and arm order was counterbalanced. Between making right- and left-arm reaching-ability estimates, participants performed the grip-strength task as described in Experiment 1. At no time during the reaching-ability estimates were participants allowed to reach over the table. After participants estimated their reaching abilities, we assessed participants' actual reaching abilities for each arm in each direction.

Results and Discussion

Accuracy of reachability estimates was determined by dividing perceived reachability estimates by actual reachability estimates. As in other reaching studies (Rochat & Wraga, 1996), participants overestimated their reaching ability. To compare reaching ability for right- and left-handed participants, we performed a 2 (hand: left vs. right) × 3 (reaching direction: contralateral vs. ipsilateral vs. central) × 2 (handedness: right vs. left) repeated measures ANOVA. Hand and direction were both specified as within-participants factors, whereas handedness was a between-participants factor. The most interesting finding was a hand-by-handedness interaction, F(1, 28) = 14.14, prep > .99, ηp2 = .34 (see Fig. 3). The only factor with a significant main effect was direction, F(2, 27) = 27.72, prep = .99; participants overestimated their contralateral (M = 1.22, SD = 0.19) and center (M = 1.19, SD = 0.16) reaches more than their ipsilateral reaches (M = 1.09, SD = 0.13).

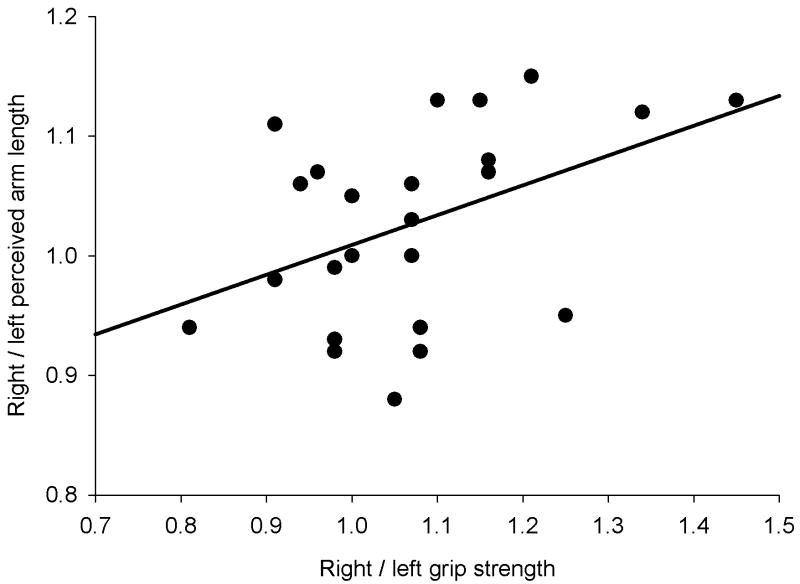

Fig. 3.

Results from Experiment 2: perceived maximum reach distance divided by actual maximum reach distance as a function of arm and reaching direction for (a) right-handed participants and (b) left-handed participants. Error bars represent 95% within-participants confidence intervals, calculated using the method in Loftus and Masson (1994).

Separate 2 (arm: left vs. right) × 3 (reaching direction) repeated measures ANOVAs for right- and left-handed participants showed that for right-handers, the main effect for arm was significant, F(1, 14) = 21.53, prep = .99, ηp2 = .59. Right-handed participants overestimated their right arm's reach (M = 1.17, SD = 0.15) more than their left arm's reach (M = 1.08, SD = 0.14). For left-handed participants, the main effect of arm was not significant, F(1, 14) = 1.86, prep = .72. For both groups, there was a main effect for direction, Fs (2, 28) > 10.71, preps = .99, ηp2s > .43, with patterns similar to what we found in the three-way ANOVA. These results show that in addition to perceiving their right arm as longer than their left arm, right-handers thought they could reach farther with their right arm than with their left arm. In contrast, left-handed people did not perceive any difference between their arms.3

Experiment 3: Perceived Hand Size and Grasping Ability in Right-Handed Participants

Because the area representing the hand in the somatosensory cortex is asymmetrical in right-handed individuals, we also hypothesized that right-handed individuals would perceive their right and left hands to be of different sizes. We had right-handed participants estimate the size of their right and left hands as well as indicate their maximum grasping abilities with their right and left hands. Because left-handed people did not display perceptual asymmetries in Experiments 1 and 2, we decided to focus only on right-handed individuals in Experiment 3.

Method

Participants

Fifteen right-handed (6 female and 9 male) University of Virginia students participated in Experiment 3 to fulfill a research requirement for course credit. Handedness was assessed through self-report using the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory (Oldfield, 1971; M = 87.35, SD = 22.87). All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision.

Stimuli and Apparatus

Participants were seated on a chair at the table described in Experiment 2. Sixteen square blocks of different sizes (side lengths ranging from 4 cm to 24 cm) were constructed from foam board that was 1.5 cm thick. Each block had two parallel black lines (3 cm in length) marked on two opposing edges of the block to indicate where the participants should anticipate placing their fingers when grasping. Participants made block-size estimates on a Dell laptop computer, which had a screen measuring 33.5 cm diagonally.

Design and Procedure

Participants sat at the table and were told that they were going to estimate whether they could grasp the block in front of them. Participants were told that the grasp that they had to anticipate entailed placing their thumb on the black line on one edge of the block and then extending their hand across the entire block to place any one of their other fingers on the black line on the other side of the block. A successful grasp was defined as being able to lift the block completely off the table. When participants indicated that they understood the instructions, they were asked to close their eyes as the experimenter placed 1 of the 16 blocks in the center of the table in front of the participants, with the black lines on the block perpendicular to the participant. The participants opened their eyes and indicated whether they thought they could successfully grasp the block with a specific hand. Then they estimated the width of the block by using the arrow keys on the laptop to move two circular white dots (0.30 cm in diameter) on a black background to be the same distance away from each other as the distance between the two black lines on the blocks (the width of the block). The laptop computer was placed on a stool beside the hand that was not being used for grasp estimates. Participants estimated their grasping ability with all 16 blocks for one hand and then all 16 blocks for the other hand, for a total of 32 trials. Blocks were presented in random order, and hand order was counterbalanced.

After making graspability judgments, participants were told to estimate the length and width of their hands. Hand length was defined as the extent between the crease at the bottom of the palm and the longest fingertip. Hand width was defined as the distance from the intersection of the pinky and palm to the intersection of the index finger and palm. The experimenter stood in front of participants while participants looked at the palm of one hand, and the experimenter adjusted a blank, retractable tape measure perpendicularly to the extent they were estimating—horizontally for length and vertically for width to prevent participants from using a landmark-matching heuristic. Participants indicated to the experimenter when they thought that the extent on the tape measure matched the length (or width) of their hand. Participants were encouraged to make fine adjustments. After participants estimated the length and width of one hand, their grip strength for both hands was assessed. Participants then estimated the length and width of their other hand. Hand order was counterbalanced across participants. After participants made their estimates, we measured the actual length and width of each hand, as well as the actual maximum grasping ability for each hand.

Results and Discussion

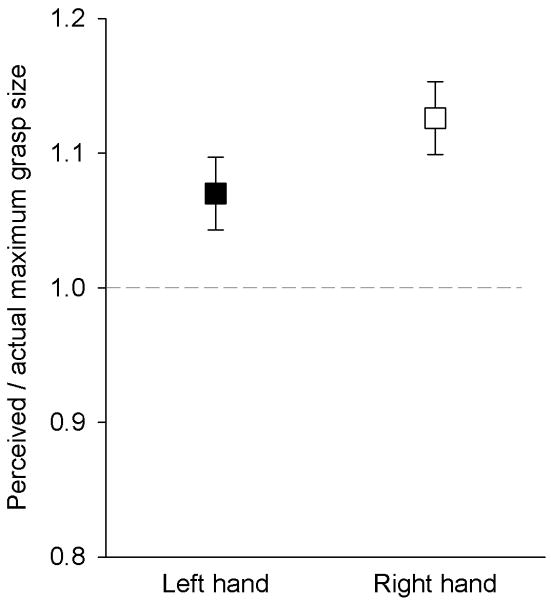

Accuracy of perceived grasping ability was determined for each participant's left and right hands by dividing perceived by actual grasping ability. Perceived grasping ability was defined as the estimated size of the largest block the participants thought they could grasp. Actual grasping ability was defined as the physical size of the largest block they were able to grasp. Right- and left-hand grasping-ability accuracies were compared using a paired-samples t test, which indicated that participants overestimated their grasping ability more with their right hand (M = 1.12, SD = 0.13) than with their left hand (M = 1.07, SD = 0.15), t(14) = 2.14, prep = .93, ηp2 = .25. As with their reachability estimates, participants overestimated their grasping ability with both their right hand, t(14) = 3.60, prep = .98, ηp2 = .48, and their left hand, t(14) = 1.85, prep = .89, ηp2 = .20 (see Fig. 4a).

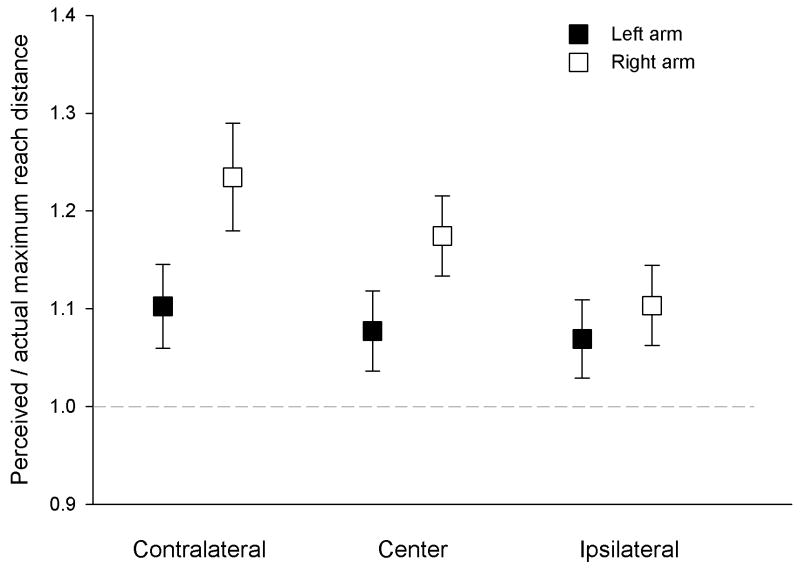

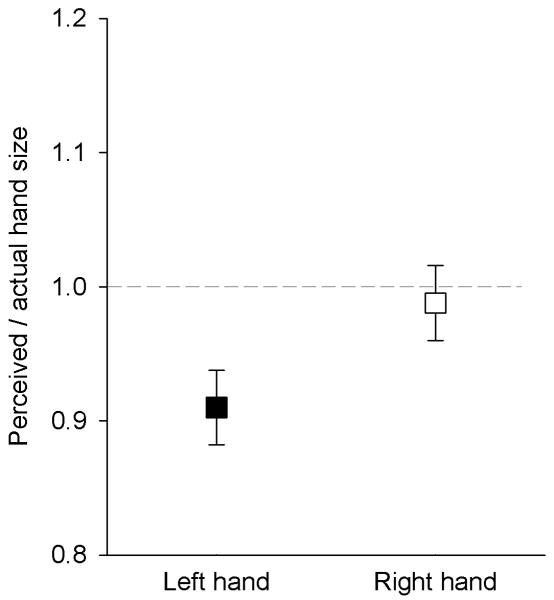

Fig. 4.

Results from Experiment 3: (a) the ratio of perceived grasping ability to actual grasping ability for each hand, (b) the ratio of perceived hand size to actual hand size for each hand, (c) the relationship between relative-strength ratio and left-right symmetry for perceived hand size, and (d) the relationship between relative-strength ratio and left-right symmetry for perceived maximum grasp size. All data are for right-handed individuals. Lines represent linear regressions of the data. Error bars represent 95% within-participants confidence intervals, calculated using the method in Loftus and Masson (1994).

In order to determine participants' accuracy in estimating their hand size, we calculated perceived hand area by multiplying the perceived width and length for each hand. The perceived area was then divided by the actual area to arrive at a measure of accuracy. One participant's data were removed from the analysis because he indicated that he misunderstood the instructions. Participants underestimated the size of their left hand (M = 0.91, SD = 0.19) more than the size of their right hand (M = 0.99, SD = 0.18), t(13) = 3.03, prep = .97, ηp2 = .41. As we found with perception of arm length, participants were accurate in perceiving the size of their right hand, prep = .50, but underestimated the size of their left hand, t(13) = 1.82, prep = .89, ηp2 = .20 (see Fig. 4b).

Strength ratios were constructed as in Experiment 1. Hand-size ratios were calculated by dividing the perceived right-hand area by the perceived left-hand area. Grasping-ability ratios were calculated by dividing perceived grasping ability with the right hand by perceived grasping ability with the left hand. Although grasping-ability ratios were not significantly related to the strength ratios, r = .22, prep = .71, hand-size ratios were positively related to strength ratios, r = .54, prep = .93 (see Figs. 4c and 4d). This finding suggests a positive association between relative hand strength and perceived right-hand size relative to left-hand size. That is, the stronger the right hand is in comparison with the left hand, the larger the right hand is perceived to be relative to the left hand. As found with perceived reach and arm length, right-handed individuals perceived their right hand to be larger and more capable of grasping larger blocks than their left hand.

General Discussion

Although functional and structural asymmetries for the body's representation in the cortical hemispheres have been documented for right-handers, this is the first set of studies to demonstrate that these differences predict perceptual consequences. Conscious perception of the dimension of arms and hands appears to be consistent with the relative size of their neural representations. Currently, we cannot determine whether these perceptual effects result in, cause, or just coincide with the different symmetries of neurological body maps that exist between right- and left-handers. Neuroimaging research has shown that training in complex actions with a specific body part can increase the size of the representation of that body part in the motor and somatosensory cortices (Elbert, Pantev, Wienbruch, Rockstroh, & Taub, 1995; Hamilton & Pascual-Leone, 1998; Nelles, Jentzen, Jueptner, Müller, & Diener, 2001). Similarly, increasing the use of a certain effector over an extended period may affect the perception of the effector in addition to the size of its area in the somatosensory cortex. However, because many neural and perceptual differences that accompany handedness cannot be attributed to experience (McManus, 2002), it is possible that these perceptual effects are the result of innate differences between right- and left-handed people, rather than a by-product of experience. In addition, these effects could arise from a reciprocal relationship between experience-driven and innate differences.

We believe that, just as handedness has an adaptive function (Wilson, 1998), these perceptual effects may be adaptive in that they promote the use of the right hand. Right-handers perceive their right, and more functional, arm as being longer than their left arm. An exaggerated perception of one arm, which coincides with the anticipation of greater reaching capabilities with that arm, may suggest why right-handers tend to use their right arm more often than their left, even when reaching awkwardly to the left side (Gonzalez et al., 2007). Handedness is adaptive in that it makes the actor become very specialized instead of distributing the amount of practice over two hands.

The current findings are nicely situated in the context of other research that demonstrates effects of functionality on perceived distance and size. For instance, targets just beyond arm's reach look closer when participants intend to reach to them with a tool than when participants intend to reach without the tool (Witt, Proffitt, & Epstein, 2005). Tools placed in an orientation that makes them easier to grasp appear closer than tools placed in an orientation that makes them more difficult to grasp (Linkenauger et al., in press). Golf holes and softballs look bigger to athletes who are playing better (Witt, Linkenauger, Bakdash, & Proffitt, 2008; Witt & Proffitt, 2005). Here, we demonstrated differences in the perceived length of the effector itself. Thus, the perceptual differences documented here could reflect the functionality of the arm as well as the neurological representation of the arm.

Future studies could look at whether neurological and functional asymmetries affect the perception of other body parts. For instance, perhaps soccer players who favor their right leg perceive it to be longer than their left. These results can also be explored within training and developmental paradigms. If perceptual differences have an experiential component, then perhaps promoting use of the nondominant hand would help individuals developing new skills to reduce their right-side biases, especially in situations in which ambidexterity is advantageous.

In summary, right-handed people perceived their right arm to be longer than their left and their right hand to be larger than their left. This perceptual bias extended into perceived action capabilities, such that right-handed people judged that they could reach farther with their right arm and grasp larger objects with their right hand than with their left arms and hands. In contrast, left-handed people exhibited none of these biases. These results suggest that the relative size of bodily representations in the cortex may influence not only tactile sensations and bodily awareness, but also people's visual perceptions of both their body and its action capabilities.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank William Epstein, Judy DeLoache, and Daniel Willingham for their comments and revisions on earlier versions of the manuscript. This research has been supported by National Institutes of Health Grant RO1MH075781 to the fourth and fifth authors.

Footnotes

Experiment 2 and Experiment 3 used the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory, instead of the dichotomous single item measure, in order to measure handedness with a continuous scale.

Because of a coding error, relative-strength ratios for 3 right-handers and 3 left-handers were unavailable, and were therefore not included in the correlation.

Because of a coding error, a substantial portion of the grip-strength data was not recorded, and as a result, we have not reported the results associated with grip strength.

References

- Amunts K, Schlaug G, Schleicher A, Steinmetz H, Dabringhaus A, Roland P, et al. Asymmetry in the human motor cortex and handedness. NeuroImage. 1996;4:216–222. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1996.0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchner H, Ludwig I, Waberski T, Wilmes K, Ferbert A. Hemispheric asymmetries of early cortical somatosensory evoked potentials revealed by topographic analysis. Electromyography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 1995;35:207–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin JT, Moore CJ, Mummery CJ, Gorno-Tempini ML, Phillips JA, Noppeney U, et al. Anatomic constraints on cognitive theories of category specificity. NeuroImage. 2002;15:675–685. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbert T, Pantev C, Wienbruch C, Rockstroh B, Taub E. Increased cortical representation of the fingers of the left hand in string players. Science. 1995;270:305–307. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5234.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez C, Whitwell R, Morrissey B, Ganel T, Goodale M. Left handedness does not extend to visually guided precision grasping. Experimental Brain Research. 2007;182:275–279. doi: 10.1007/s00221-007-1090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton R, Pascual-Leone A. Cortical plasticity associated with Braille learning. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 1998;2:168–174. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(98)01172-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung P, Baumgärtner U, Bauermann T, Magerl W, Gawehn J, Stoeter P, Treede R. Asymmetry in the human primary somatosensory cortex and handedness. NeuroImage. 2003;19:913–923. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00164-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima R, Kentaro I, Kazunori S, Hiroshi F. Functional asymmetry of the cortical motor control in left-handed subjects. NeuroReport. 1997;8:1729–1732. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199705060-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SG, Ashe J, Hendrich K, Ellerman JM, Merkle H, Ugurbil K, et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging of morot cortex: Hemispheric asymmetry and handedness. Science. 1993;261:615–617. doi: 10.1126/science.8342027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linkenauger SA, Witt JK, Stefanucci JK, Bakdash JZ, Proffitt DR. Effects of handedness and reachability on perceived distance. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. doi: 10.1037/a0016875. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loftus GR, Masson MEJ. Using confidence intervals in within-subject designs. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 1994;1:476–490. doi: 10.3758/BF03210951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus C. Right hand, left hand: The origins of asymmetry in brains, bodies, atoms, and cultures. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nelles G, Jentzen W, Jueptner M, Müller S, Diener H. Arm training induced brain plasticity in stroke studied with serial positron emission tomography. NeuroImage. 2001;13:1146–1154. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield RC. The assessment and analysis of handedness: The Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia. 1971;9:97–113. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantev C, Engelien A, Candia V, Elbert T. Representational cortex in musicians. Plastic alterations in response to musical practice. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2001;930:300–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perenin M, Vighetto A. Optic ataxia: Specific disruption in visuomotor mechanisms. Brain. 1988;111:643–674. doi: 10.1093/brain/111.3.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochat P, Wraga M. An account of the systematic error in judging what is reachable. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1997;23:199–212. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.23.1.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigal RA. Which handedness: Preference or performance? Perceptual and Motor Skills. 1992;75:852–866. doi: 10.2466/pms.1992.75.3.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sörös P, Knecht S, Imai T, Gürtler S, Lütkenhöner B, Ringelstein E, et al. Cortical asymmetries of the human somatosensory hand representation in right- and left-handers. Neuroscience Letters. 1999;271:89–92. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00528-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson FR. The hand: How its use shapes the brain, language, and human culture. New York: Random House; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Witt JK, Linkenauger SA, Bakdash JZ, Proffitt DR. Putting to a bigger hole: Golf performance relates to perceived size. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2008;15:581–585. doi: 10.3758/pbr.15.3.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt JK, Proffitt DR. See the ball, hit the ball: Apparent ball size is correlated with batting average. Psychological Science. 2005;16:937–938. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt JK, Proffitt DR, Epstein W. Tool use affects perceived distance but only when you intend to use it. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 2005;31:880–888. doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.31.5.880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilles K, Schleicher A, Langemann C, Amunts K, Morosan P, Palomero-Gallagher N, et al. Quantitative analysis of sulci in the human cerebral cortex: Development, regional heterogeneity, gender difference, asymmetry, intersubject variability and cortical architecture. Human Brain Mapping. 1997;5:218–221. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(1997)5:4<218::AID-HBM2>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]