Abstract

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) play a pivotal role in tissue remodeling and destruction in inflammation-associated diseases such as cardiovascular disease and periodontal disease. Although it is known that interleukin (IL)-6 is a key proinflamatory cytokine, it remains unclear how IL-6 regulates MMP expression by mononuclear phagocytes. Furthermore, it remains undetermined how IL-6 in combination with hyperglycemia affects MMP expression. In the present study, we investigated the regulatory effect of IL-6 alone or in combination with high glucose on MMP-1 expression by U937 mononuclear phagocytes. We found that IL-6 is a powerful stimulator for MMP-1 expression and high glucose further augmented IL-6-stimulated MMP-1 expression. We also found that high glucose, IL-6, and lipopolysaccharide act in concert to stimulate MMP-1 expression. In the studies to elucidate underlying mechanisms, the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathways were found to be required for stimulation of MMP-1 by IL-6 and high glucose. We also observed that IL-6 and high glucose stimulated the expression of c-Jun, a key subunit of AP-1 known to be essential for MMP-1 transcription. The role of c-Jun in MMP-1 expression was confirmed by the finding that suppression of c-Jun expression by RNA interference significantly inhibited MMP-1 expression. Finally, we demonstrated that similarly to U937 mononuclear phagocytes, IL-6 and high glucose also stimulated MMP-1 secretion from human primary monocytes. In conclusion, this study demonstrated that IL-6 and high glucose synergistically stimulated MMP-1 expression in mononuclear phagocytes via ERK and JNK cascades and c-Jun upregulation.

Keywords: Matrix metalloproteinases, Interleukin 6, Diabetes, Mitogen-activated protein kinases

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is a multifunctional cytokine involved in the acute phase response, immunity, hematopoiesis, and inflammation [Ishihara and Hirano, 2002; Kishimoto, 2006]. IL-6 plays an essential role in many chronic inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic-onset juvenile chronic arthritis, osteoporosis, psoriasis, and autoimmune diseases such as antigen-induced arthritis and experimental allergic encephalomyelitis [Ishihara and Hirano, 2002]. IL-6 is also important in the pathogenesis of infectious diseases such as periodontal disease [Geivelis et al., 1993; Rusconi et al., 1991]. Furthermore, IL-6 is a marker for cardiovascular disease [Kristiansen and Mandrup-Poulsen, 2005; Rattazzi et al., 2003], which is considered as an inflammatory disease. Studies have well documented that the plasma levels of IL-6 and C-reactive protein are strong independent predictors of risk of future cardiovascular events, both in patients with a history of coronary heart disease and in apparently healthy subjects [Rattazzi et al., 2003]. Numerous studies have further demonstrated that IL-6 is not just a marker for inflammation-associated diseases; it is a major player involved in the initiation and progression of the diseases [Lowe, 2001; Moutsopoulos and Madianos, 2006; Rattazzi et al., 2003].

IL-6 expression is upregulated in a variety of cells including monocytes, macrophages, lymphocytes, keratinocytes, endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and adipocytes by bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and TNFα [Kishimoto, 2006]. IL-6 exerts its effects on gene expression via IL-6 receptor (IL-6R) complex consisting of the ligand-binding IL-6R α chain (IL-6Rα) that is also known as CD126 and the signal-transducing component glycoprotein 130 (gp130) [Yawata et al., 1993]. The complex brings together the intracellular regions of gp130 to trigger a signal transduction cascade through Janus kinases/signal transducers and activators of transcription (JAKs/STATs) and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), leading to the transcriptional activation of gene expression.

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) belong to a family of zinc- and calcium-dependent proteinases that degrade various constituents of the extracellular matrix [Yan and Boyd, 2007]. In the chronic inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, periodontal disease and atherosclerosis, MMPs play an important role in the disease progression by increasing matrix protein degradation [Hu et al., 2007; Manicone and McGuire, 2008]. MMPs are expressed by a variety of cell types including inflammatory cells such as mononuclear phagocytes and neutrophils, and resident cells such as fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells and endothelial cells [Yan and Boyd, 2007]. In inflamed tissues, infiltrated mononuclear cells not only release inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-1β and TNFα, but also secrete MMPs [Leppert et al., 2001; Sorsa et al., 2006]. Although it is known that both IL-6 and MMP levels are elevated in inflamed tissues, it remains unclear if and how IL-6 regulates MMP expression by mononuclear phagocytes.

Diabetes mellitus is a chronic and systemic disease that causes several complications including cardiovascular disease, peripheral vascular diseases and periodontal disease [Rogus et al., 2002]. In these complications, both IL-6 and MMP expressions are upregulated and involved in tissue inflammation and destruction [Dogan et al., 2008]. However, it is not clear how diabetes-associated factors such as hyperglycemia affect the MMP expression. In the present study, we examined the effects of IL-6 and high glucose on MMP-1 expression by U937 mononuclear phagocytes. We showed that IL-6 was more potent than LPS in the stimulation of MMP-1 expression by mononuclear cells. More importantly, we demonstrated that the stimulatory effect of IL-6 and high glucose on MMP-1 expression was mediated by the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathways and c-Jun upregulation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture

U937 mononuclear phagocytes [Sundstrom and Nilsson, 1976] were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). The cells were cultured in a 5% CO2 atmosphere in RPMI 1640 medium (GIBCO, Invitrogen Cop. Carlsbad, CA) containing normal glucose (5 mM) or high glucose (25 mM), 10% fetal calf serum, 1% MEM non-essential amino acid solution, and 0.6 g/100 ml of HEPES. Five and 25 mM of glucose have been used commonly as the concentrations of normal and high glucose, respectively, in the published studies [Nareika et al., 2008; Nareika et al., 2007; Sundararaj et al., 2009]. Human monocytes were isolated as described previously [Seager Danciger et al., 2004] from blood obtained from healthy donors and treated in the medium that was same as that used for U937 cells. The blood donation for monocyte isolation was approved by university Institution Review Board (IRB).

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

MMP-1 and TIMP-1 in conditioned medium was quantified using sandwich ELISA kits according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer (R&D System, Minneapolis, MN).

Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from cells using the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen, Santa Clarita, CA). First-strand complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized with the iScript™ cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) using 20 μl of reaction mixture containing 0.25 μg of total RNA, 4 μl of 5x iScript reaction mixture, and 1 μl of iScript reverse transcriptase. The complete reaction was cycled for 5 minutes at 25°C, 30 minutes at 42°C and 5 minutes at 85°C using a PTC-200 DNA Engine (MJ Research, Waltham, MA). The reverse transcription (RT) reaction mixture was then diluted 1:10 with nuclease-free water and used for PCR amplification of cDNA in the presence of the primers. The Beacon designer software (PREMIER Biosoft International, Palo Alto, CA) was used for primer designing (MMP-1: 5′ primer sequence, CTGGGAAGCCATCACTTACCTTGC; 35′ primer sequence, GTTTCTAGAGTCGCTGGGAAGCTG). Primers were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (Coralville, IA) and real-time PCR was performed in duplicate using 25 μl of reaction mixture containing 1.0 μl of RT mixture, 0.2 μM of both primers, and 12.5 μl of iQ™ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Real-time PCR was run in the iCycler™ real-time detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories) with a two-step method. The hot-start enzyme was activated (95°C for 3 min) and cDNA was then amplified for 40 cycles consisting of denaturation at 95°C for 10 sec and annealing/extension at 53°C for 45 sec. A melt-curve assay was then performed (55°C for 1 min and then temperature was increased by 0.5°C every 10 sec) to detect the formation of primer-derived trimers and dimmers. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a control (5′ primer sequence, GAATTTGGCTACAGCAACAGGGTG; ′ primer sequence, TCTCTTCCTCTTGTGCTCTTGCTG). Data were analyzed with the iCycler iQ™ software. The average starting quantity (SQ) of fluorescence units was used for analysis. Quantification was calculated using the SQ of targeted cDNA relative to that of GAPDH cDNA in the same sample.

Collagenase Activity Assay

The culture medium was collected after treatment of U937 cells with IL-6 and subjected to collagenase activity assay using a collagenase activity assay kit (Millipore Corp., Billerica, MA), in which fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled type I collagen was used as substrate. The experiment was performed by following the instruction provided by the manufacturer.

PCR Array

The first-strand cDNA was synthesized from RNA using RT2 First Strand Kit (SABiosciences Corporation, Frederick, MD). Human Extracellular Matrix PCR Array (Cat. No. PAHS-013, SABiosciences Corporation) was used to detect MMP and TIMP expression by following the instruction from the manufacturer.

RNA Interference

U937 cells pre-exposed to high glucose were transientlytransfected with 200 nM of SMART pool c-JUN siRNA (Dharmacon, Inc., Chicago, IL ) (GenBank accession number NM_002228) or scrambled siRNA control using Lipofectamine RNAi MAX reagent (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA) by following the manufacturer’s instructions. Forty-eight hours later, transfected cells were treated with or without 10ng/ml of IL-6 for 24 h.

Immunoblotting

After treatment, cells were lysed with lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mMEDTA, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate,1 mM Na3VO4, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM PMSF, and 10 μg/ml leupeptin. The cell lysates were cleared by centrifugation. Each sample with 50 μg protein was electrophoresed in a 10% polyacrylamidegel. After transfer of proteins to a PVDF membrane, immunoblotting was performed using anti-c-Jun or β-actin antibody(New England BioLabs, Inc., Ipswich, MA).

Treatment of U937 Cells with Curcumin and Simvastatin

U937 cells pre-exposed to normal or high glucose were treated with 5 or 10 μM of curcumin or simvastatin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 24 h and MMP-1 released by cells into culture medium was determined using ELISA. Previous studies have shown that the concentrations of 10–30 μM of curcumin and simvastatin are effective in the inhibition of gene expression [Aggarwal et al., 2005; Dickinson et al., 2003; Nareika et al., 2005; Nareika et al., 2007; Sundararaj et al., 2008].

Statistic Analysis

Data were presented as mean ± SD. Student t tests were performed to determine the statistical significance of cytokine expression among different experimental groups. A value of P< 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

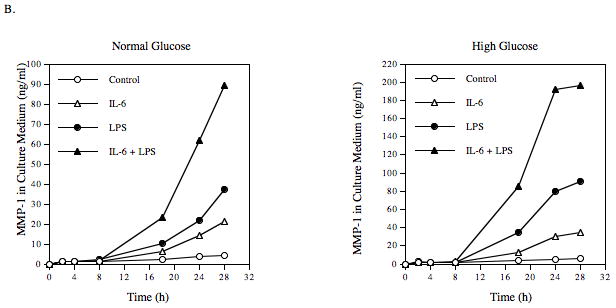

The Effect of IL-6 and High Glucose on MMP-1 Secretion by U937 cells

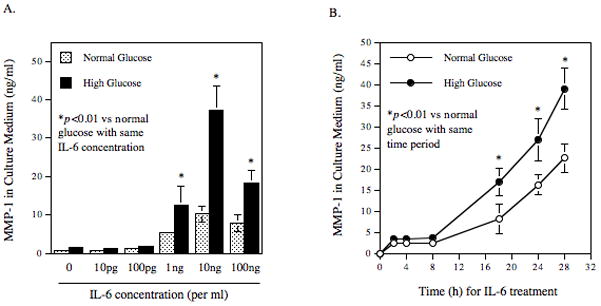

The effect of IL-6 and high glucose (25 mM) on MMP-1 secretion by U937 cells was first examined. Results showed that IL-6 stimulated MMP-1 secretion in a concentration-dependent manner with maximal stimulation at 10 ng/ml (Fig. 1A). The stimulatory effect was reduced when the concentration was increased to 100 ng/ml. Furthermore, pre-exposure of U937 cells to high glucose increased IL-6-stimulated MMP-1 secretion by 2–3-fold as compared to pre-exposure to normal glucose (Fig. 1A). Time course study showed a time-dependent secretion of MMP-1 in response to IL-6, and increased secretion was observed after stimulation for 8 h (Fig. 1B). High glucose significantly increased IL-6-stimulated MMP-1 secretion at 18, 24 and 36 h (Fig. 1B). To further study the synergistic effect of elevated glucose level and IL-6 on MMP-1 secretion, we pre-treated U937 cells with different concentrations of glucose (5, 10, 15, 20, or 25 mM) for 2 days, treated with IL-6 (1 ng/ml or 10 ng/ml) for 24 h, and then quantified MMP-1 secretion. Results showed a glucose-dependent increase in MMP-1 secretion by U937 cells treated with 1 or 10 ng/ml of IL-6 (Fig. 1C). Table 1 shows the data presented in Fig. 1C. Table 2 shows the glucose-dependent synergism of high glucose and IL-6 on MMP-1 secretion. By comparing to the total of MMP-1 secretion in response to 15 mM of glucose alone and that in response to 10 ng/ml of IL-6 alone, MMP-1 secretion in response to 15 mM of glucose plus 10 ng/ml of IL-6 was increased by 54%. Further, by comparing to the total of MMP-1 secretion in response to 25 mM of glucose alone and that in response to 10 ng/ml of IL-6 alone, MMP-1 secretion in response to 25 mM of glucose plus 10 ng/ml of IL-6 was increased by 98%. These data clearly showed a glucose-dependent synergism of high glucose and IL-6 on MMP-1 secretion.

Figure 1.

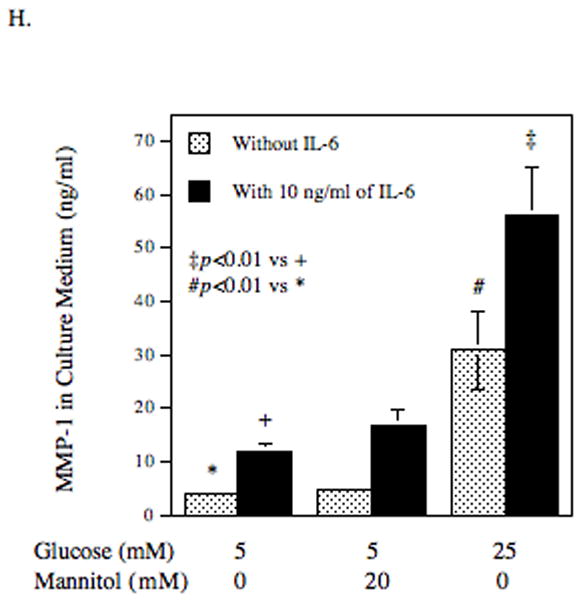

The effect of high glucose, IL-6 or both on MMP-1 and TIMP-1 secretion by U937 cells and on collagenase activity in culture medium. A and B: U937 cells cultured with normal or high glucose-containing medium were challenged with different concentrations (0–100 ng/ml) of IL-6 for 24 h (A) or with 10 ng/ml of IL-6 for different time periods (0–28 h) (B). After the treatment, the MMP-1 in culture medium was quantified using ELISA. C: U937 cells were pre-treated with glucose at different concentrations (5, 10, 15, 20, or 25 mM) for 24 h and then treated with IL-6 at 1 or 10 ng/ml for 24 h. After treatment, MMP-1 in culture medium was quantified using ELISA. D and E: U937 cells cultured in normal glucose (NG) or high glucose (HG)-containing medium were challenged with 10 ng/ml of IL-6 for 24 h. After treatment, RNA was isolated and subjected to reverse transcription and real-time PCR to quantify MMP-1 mRNA level. MMP-1 mRNA level was normalized to GAPDH mRNA level (D). The real-time PCR raw data showing the amplification curves of MMP-1 cDNA (E). F: The TIMP-1 levels in the culture medium of the above experiment was quantified using ELISA. G: The collagenase activity in the culture medium of the above experiment was determined. The data presented as % of collagenase activity in cells exposed to NG without IL-6. HG, high glucose; NG, normal glucose. H: The effect of mannitol on MMP-1 expression by U937 cells. U937 cells were pre-exposed to 5 mM of glucose, 5 mM of glucose plus 20 mM of mannitol or 25 mM of glucose for 2 days and then treated with our without 10 ng/ml of IL-6 for 24 h. After the treatment, MMP-1 in culture medium was quantified using ELISA. The data presented are mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

Table 1.

Glucose-dependent MMP-1 Secretion from Cells in Response to IL-6

| 5 mM | 10 mM | 15 mM | 20 mM | 25 mM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No IL-6 | 4.67 | 4.67 (0) | 8.00 (3.33) | 10.10 (5.43) | 13.63 (8.96) |

| 1 ng/ml of IL-6 | 9.91 (5.24) | 10.04 (5.37) | 14.62 (9.95) | 20.57 (15.90) | 26.12 (21.45) |

| 10 ng/ml of IL-6 | 16.80 (12.13) | 19.91 (15.24) | 28.49 (23.82) | 38.28 (33.61) | 46.43 (41.76) |

U937 cells were exposed to increasing glucose concentrations for 2 days and then treated without or with IL-6 (1 ng/ml or 10 ng/ml) for 24 h. After treatment, MMP-1 in medium was quantified using ELISA. The numbers outside the parentheses are the amounts of MMP-1 (ng/ml) detected by ELISA. The numbers in the parentheses are increased amounts of MMP-1 after subtracting 4.67 (ng/ml), the basal level of secreted MMP-1.

Table 2.

Glucose-dependent Synergism on IL-6-stimulated MMP-1 Secretion

| IL-6 | Glucose Concentrations | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 mM | 20 mM | 25 mM | |||||||

| Observed increase | Expected additive increase | % of increase | Observed increase | Expected additive increase | % of increase | Observed increase | Expected additive increase | % of increase | |

| 1 ng/ml | 9.95 | 8.57 (3.33+5.24) | 16% | 15.9 | 10.67 (5.43+5.24) | 49% | 21.45 | 14.2 (8.96+5.24) | 51% |

| 10 ng/ml | 23.82 | 15.46 (3.33+12.13) | 54% | 33.61 | 17.56 (5.43+12.13) | 91% | 41.76 | 21.09 (8.96+12.13) | 98% |

The data were calculated from those in Table 1. The “observed increase” in MMP-1 secretion was calculated by subtracting the basal level of MMP-1 secretion (in the presence of 5 mM glucose and absence of IL-6), which is 4.67 ng/ml, from the observed amount of MMP-1 secretion. The “expected additive increase” in MMP-1 secretion was calculated by adding the increased amount of MMP-1 secretion in response to a particular concentration of glucose alone with that in response to a particular concentration of IL-6 alone. The “% of increase” was calculated by the following formula: [(observed increase − expected additive increase)/expected additive increase]*100.

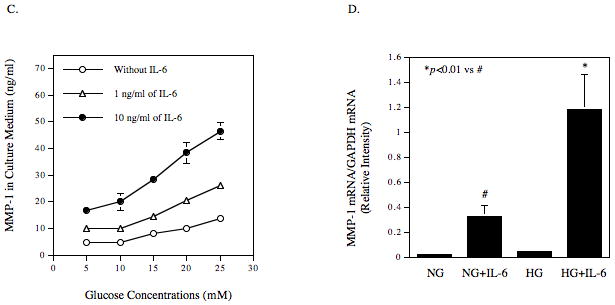

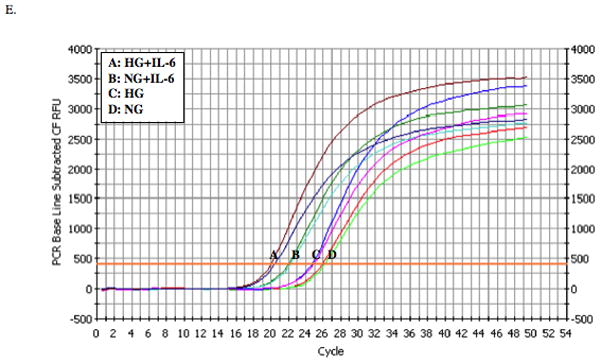

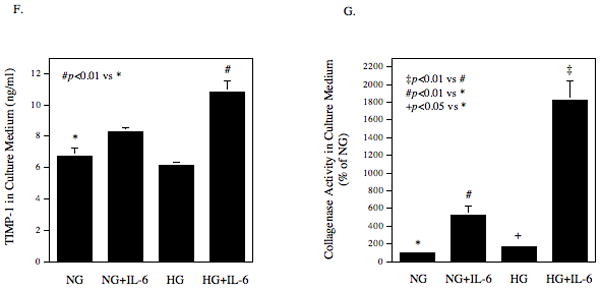

Data from quantitative real-time PCR showed that IL-6 stimulated MMP-1 mRNA expression, and high glucose further amplified the stimulatory effect of IL-6 (Figs. 1D and 1E), suggesting that the stimulation of MMP-1 secretion by IL-6 and high glucose is due to increased MMP-1 mRNA expression.

The tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase (TIMP)-1 level in culture medium was also determined. Results showed that while high glucose and IL-6 had insignificant effect on TIMP-1 secretion, high glucose plus IL-6 significantly increased TIMP-1 secretion by 60% (p<0.01) (Fig. 1F). Since high glucose and IL-6 increased both MMP-1 and TIMP-1, the collagenase activity in culture medium was determined. Results showed that either high glucose or IL-6 significantly increased collagenase activity and high glucose plus IL-6 further increased collagenase activity (Fig. 1G).

To exclude the possibility that the augmentation of IL-6-stimulated MMP-1 secretion by high glucose is due to increase in osmolarity, we pre-treated U937 cells with 5 mM of glucose plus 20 mM of mannitol and then treated with or without IL-6. Results showed that the addition of 5 mM of glucose plus 20 mM of mannitol had no effect on MMP-1 secretion in control cells and only slightly increased MMP-1 secretion in IL-6-treated cells by 45% as compared to the cells exposed to 5 mM of glucose and IL-6 (Fig. 1H). In contrast, 25 mM of glucose augmented IL-6-stimulated MMP-1 secretion by 480%. Furthermore, the pH changes in culture medium containing normal and high glucose after 24 h incubation were determined and pH was 7.2 in normal glucose-containing medium and 7.0 in high glucose-containing medium. We have reported previously that the pH change from 7.4 to 7.0 did not increase MMP-1 secretion by U937 cells [Nareika et al., 2005].

The Stimulatory Effect of IL-6 on the Expression of Other MMPs and TIMPs

The effect of IL-6 and high glucose on the secretion of other MMPs and TIMPs by U937 cells was investigated using PCR array technique. Results showed that although IL-6 or high glucose by itself had no effect on MMP-8 and MMP-9 expression, the combination of IL-6 and high glucose increased MMP-8 and MMP-9 expression by about 2-fold as compared to the combination of IL-6 and normal glucose (Table 3). In contrast, IL-6 and high glucose had no effect on MMP-2, -3 and -7 expression (data not shown), suggesting a specific stimulation by IL-6 and high glucose on MMP-1, -8 and -9. Results also showed that the combination of IL-6 and high glucose increased TIMP-1 by 2-fold, which is similar to the results shown in Fig. 1F, and had no effect on TIMP-2 and TIMP-3 (Table 3). It is noteworthy that the fold-increase of TIMP-1 expression was much less than that of MMP-1 expression (2-fold vs 20-fold) by high glucose and IL-6, which is consistent with the finding that high glucose and IL-6 increased collagenase activity in culture medium (Fig. 1G).

Table 3.

The effect of IL-6 and high glucose on the expression of MMPs and TIMPs

| Genes | NG | HG | NG + IL-6 | HG + IL-6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMP-1 | 1 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 2.8 ± 0.4 | 19.7 ± 1.4 * |

| MMP-8 | 1 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.3 * |

| MMP-9 | 1 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 2.3 ± 0.3 * |

| TIMP-1 | 1 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.2 * |

| TIMP-2 | 1 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.67 ± 0.1 |

| TIMP-3 | 1 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 |

| GAPDH | 1 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.2 |

U937 cells cultured with normal glucose (NG) or high glucose (HG) were treated with 10 ng/ml of IL-6 for 24 h. After the treatment, RNA was isolated and subjected to PCR array to determine the expression of MMPs and TIMPs as described in METHODS. The numbers are fold of the gene expression in cells pre-exposed to NG without IL-6 treatment, which was designated as 1. The data presented are the averages of two independent experiments.

p<0.01 vs NG+IL-6.

IL-6 Is A Potent Stimulator for MMP-1 Expression by U937 cells

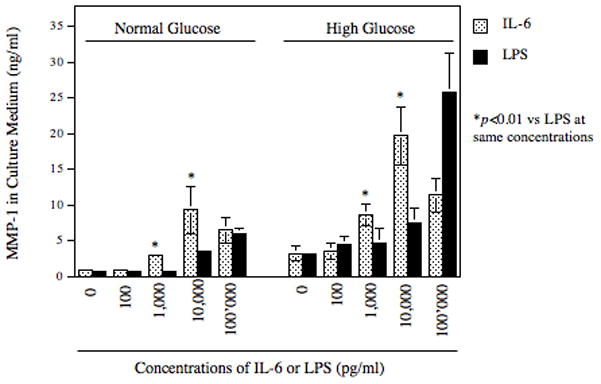

To determine the potency of IL-6 on MMP-1 expression, we compared IL-6 with LPS, a strong stimulator for MMP-1 expression [Nareika et al., 2008]. Results showed that at the concentrations of 1 ng/ml and 10 ng/ml, IL-6 was 2–3-fold more potent than LPS in the stimulation of MMP-1 secretion from either normal or high glucose-pre-exposed U937 mononuclear cells (Fig. 2). At 100 ng/ml, the stimulatory effect of IL-6 decreased while that of LPS increased. These results demonstrated that IL-6 was a potent stimulator for MMP-1 expression at the relatively low concentrations. Results also showed that high glucose amplified both LPS- and IL-6-stimulated MMP-1 secretion (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

The effects of IL-6 and LPS on MMP-1 secretion by U937 cells. U937 cells cultured with normal glucose or high glucose were challenged with different concentrations (0–100,000 pg/ml) of IL-6 or LPS for 24 h. After the treatment, MMP-1 in culture medium was quantified using ELISA. The data presented are mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

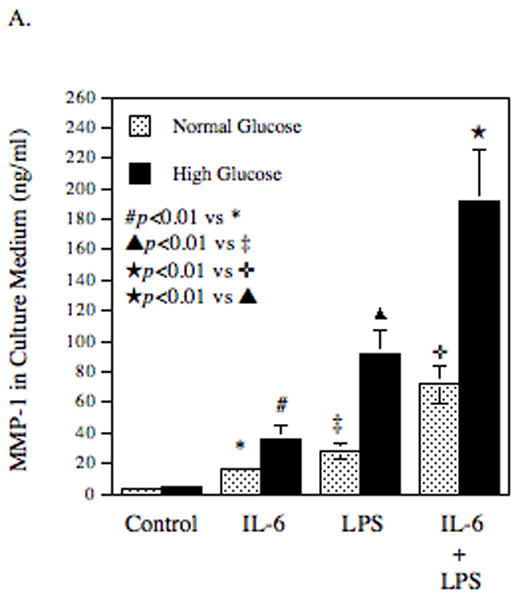

High Glucose, IL-6, and LPS have Synergism on MMP-1 Secretion

In patients with both diabetes and infectious diseases with Gram negative bacteria, high glucose, LPS and IL-6 are all present in the inflamed tissue [Nishimura et al., 1998]. Therefore, we determined the effect of the combination of high glucose, IL-6 and LPS on MMP-1 secretion. Results showed that MMP-1 secretion was markedly increased in response to the combination of IL-6 and LPS as compared with that in response to IL-6 or LPS alone (Table 4 and Fig. 3A), revealing a synergistic effect of IL-6 and LPS on MMP-1 secretion. Moreover, pre-exposure of cells with high glucose further enhanced the synergism between IL-6 and LPS by 2.6-fold when compared to pre-exposure to normal glucose (Table 4 and Fig. 3A). Time course studies also demonstrated the synergistic effect of high glucose, IL-6 and LPS at 18, 24, and 28 h (Fig. 3B). Taken together, these data indicate that high glucose, IL-6, and LPS act in concert to stimulate MMP-1 secretion.

Table 4.

The synergistic effect of high glucose, IL-6 and LPS on MMP-1 secretion

| Control | IL-6 | LPS | IL-6 + LPS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Glucose | 3.60 ± 0.11 (1.00) | 14.20 ± 0.425* (3.94) | 21.84 ± 0.69* (6.07) | 61.54 ± 0.99** (17.09) |

| High Glucose | 4.98 ± 0.41 (1.38) | 29.85 ± 4.26+ (8.29) | 80.15 ± 5.75+ (22.26) | 191.77 ± 5.35++ (53.27) |

U937 cells cultured with normal glucose or high glucose were treated with 10 ng/ml of IL-6, 100 ng/ml of LPS or both for 24 h. After the treatment, culture medium was subjected to MMP-1 ELISA. The numbers outside the parentheses are mean ± SD of MMP-1 (ng/ml). The numbers inside the parentheses are fold increases compared to the amount of MMP-1 in control cells, which was designated as 1.00.

p<0.01 vs Control with normal glucose;

p<0.01 vs *;

p<0.01 vs Control with high glucose;

p<0.01 vs +.

The data presented are from one of two independent experiments with similar results.

Figure 3.

The synergistic effect of IL-6, LPS and high glucose on MMP-1 secretion by U937 cells. U937 cells cultured with normal glucose- or high glucose-containing medium were challenged with 10 ng/ml of IL-6, 100 ng/ml of LPS or both for 24 h (A) or for different time periods (0–28 h) (B). After treatment, MMP-1 in culture medium was quantified using ELISA. The data presented are mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

IL-6 Stimulates MMP-1 Expression by U937 Mononuclear Phagocytes via ERK and JNK Pathways

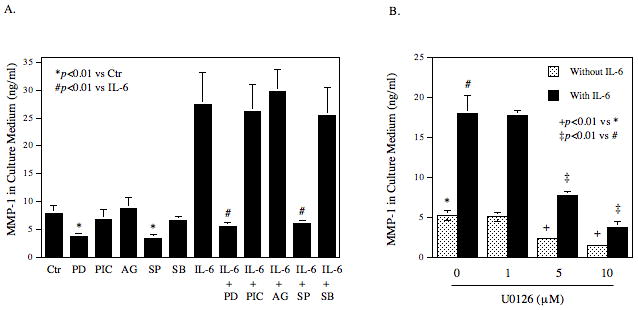

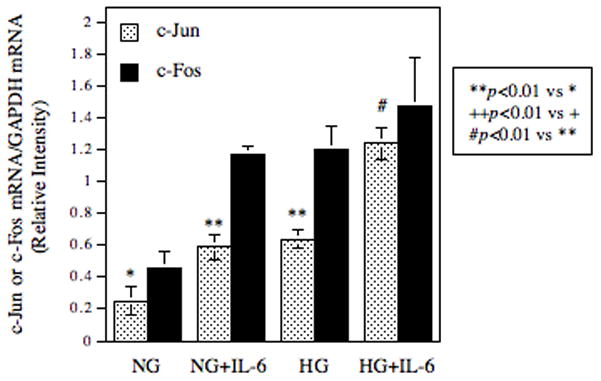

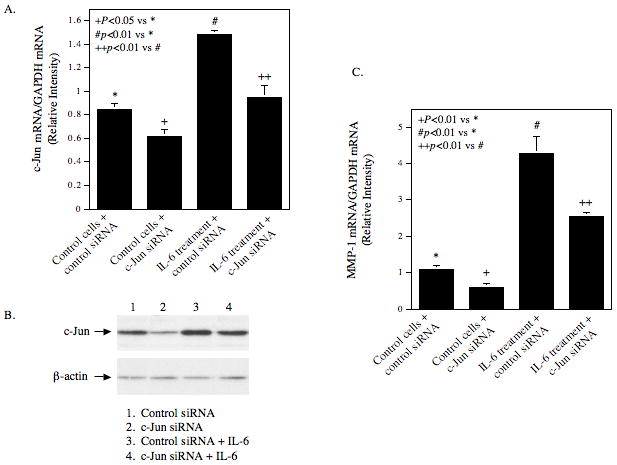

It is known that JAK/STAT pathway and MAPK pathways including the ERK and JNK pathways mediate IL-6-regulated gene expression [Kishimoto, 2006]. Thus, we determined which pathway is involved in IL-6-stimulated MMP-1 expression using specific inhibitors of these pathways. Results showed that PD98059 and SP600125, which inhibit the ERK and JNK pathway, respectively, not only completely abolished IL-6-stimulated MMP-1 secretion, but also inhibited the basal level of MMP-1 secretion (Fig. 4A). U0126, another specific ERK inhibitor, also inhibited the basal and IL-6-stimulated MMP-1 secretion effectively, further demonstrating the involvement of ERK in MMP-1 expression (Fig. 4B). In contrast, piceatannol, a specific JAK/STAT3 inhibitor [Kim et al., 2008], and AG490, an inhibitor for both JAK/STAT1 and JAK/STAT3 pathways [Caceres-Cortes, 2008], had no significant effect on the baseline level and IL-6-stimulated MMP-1 secretion. Furthermore, SB203580, a specific inhibitor for p38 MAPK pathway that is another cascade of MAPK pathways [Lee et al., 1994], failed to inhibit IL-6-stimulated MMP-1 secretion. Thus, these results suggest that ERK and JNK pathways, but not JAK/STAT3 and p38 MAPK cascades, mediate the stimulation of MMP-1 expression by IL-6. Since it is known that activator protein (AP)-1 is a key transcription factor for MMP-1 expression, and the activation of ERK and JNK pathways leads to increased AP-1 activity [Vincenti et al., 1996], the effect of IL-6 and high glucose on the expression of AP-1 subunits c-Jun and c-Fos was determined. Results showed that while either IL-6 or high glucose by itself increased c-Jun expression by 2–3-fold, the combination of IL-6 and high glucose further stimulated the c-Jun expression by 5-fold (Fig. 5). In contrast, although IL-6 or high glucose by itself also increased c-Fos expression, the combination of IL-6 and high glucose did not further increase c-Fos expression, suggesting that IL-6 and high glucose may synergistically stimulate MMP-1 expression by increasing c-Jun expression. To confirm the essential role of c-Jun in the upregulation of MMP-1 expression by IL-6 and high glucose, RNA interference technique was employed to inhibit c-Jun expression. Results from both real-time PCR and immunoblotting showed that the c-Jun expression by both control and IL-6/high glucose-stimulated cells was inhibited significantly by c-Jun siRNA transfection (Fig. 6A and B), which led to a 44% reduction of the basal MMP-1 expression by control cells and a 54% reduction of the increased MMP-1 expression by IL-6/high glucose-treated cells (Fig. 6C).

Figure 4.

The effect of specific signaling pathway inhibitors on IL-6-stimulated MMP-1 secretion. A. U937 cells cultured with high glucose were challenged with 10 ng/ml of IL-6 in the presence or absence of 10 μM of PD98059 (PD), piceatannol (PIC), AG490 (AG), SP600125 (SP), or SB203580 (SB) for 24 h. B. U937 cells cultured with high glucose were challenged with or without 10 ng/ml of IL-6 in the absence or presence of different concentrations of (0–10 μM) U0126 for 24 h. After the treatment, MMP-1 in culture medium was quantified using ELISA. The data presented are mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

Figure 5.

The effect of high glucose, IL-6 or both on c-Jun and c-Fos expression. U937 cells cultured with normal glucose (NG) or high glucose (HG)-containing medium were treated with 10 ng/ml of IL-6 for 24 h. After treatment, RNA were isolated from cells and subjected to real-time PCR analysis of c-Jun and c-Fos expression. The data presented are mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

Figure 6.

The effect of c-Jun on MMP-1 expression. U937 cells pre-exposed to high glucose were transfected with c-Jun siRNA or scamble siRNA (control siRNA) for 48 h. After the transfection, cells were treated with or without 10 ng/ml of IL-6 for 24 h. RNA was then isolated from part of the cells for real-time PCR to quantify both c-Jun (A) and MMP-1 mRNA expression (C), which were normalized to GAPDH mRNA. Proteins were extracted from part of the cells for immunoblotting of c-Jun and β-actin (control) (B). The data presented is from one of three independent experiments with similar results.

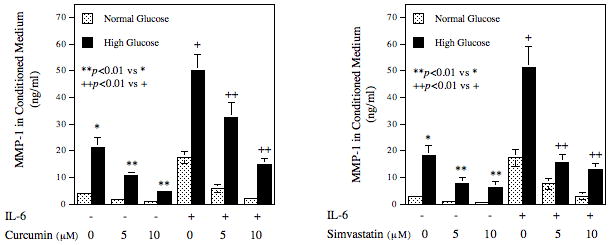

Curcumin and Simvastatin Block the Stimulatory Effect of High Glucose and IL-6 on MMP-1 Secretion

It is known that curcumin, a diet supplement, is a potent inhibitor for AP-1 [Aggarwal et al., 2005; Dickinson et al., 2003]. It is also known that statins, the 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG CoA) reductase inhibitors and cholesterol-lowering drugs, inhibit AP-1 activity by blocking ERK activation [Sundararaj et al., 2008]. Our previous study has shown that simvastatin inhibited MMP-1 secretion from U937 cells by suppressing AP-1 activity [Sundararaj et al., 2008]. To provide more evidence that IL-6 and high glucose stimulate MMP-1 expression through AP-1, we determine the effect of curcumin and simvastatin on MMP-1 expression upregulated by IL-6 and high glucose. Results showed that curcumin and simvastatin inhibited both basal and IL-6/high glucose-stimulated MMP-1 secretion in a concentration- dependent manner (Fig. 7). Curcumin at 10 μM inhibited IL-6-stimulated MMP-1 secretion from cells pre-exposed to normal and high glucose by 78% and 70%, respectively. Similarly, simvastatin at 10 μM inhibited IL-6-stimulated MMP-1 secretion from cells pre-exposed to normal and high glucose by 86% and 75%, respectively.

Figure 7.

The effect of curcumin or simvastatin on IL-6-stimulated MMP-1 secretion by U937 cells. U937 cells cultured with normal glucose- or high glucose-containing medium were challenged with or without 10 ng/ml of IL-6 in the presence or absence of 5 or 10 μM of curcumin or simvastatin for 24 h. After the treatment, MMP-1 in culture medium was quantified using ELISA. The data presented are mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

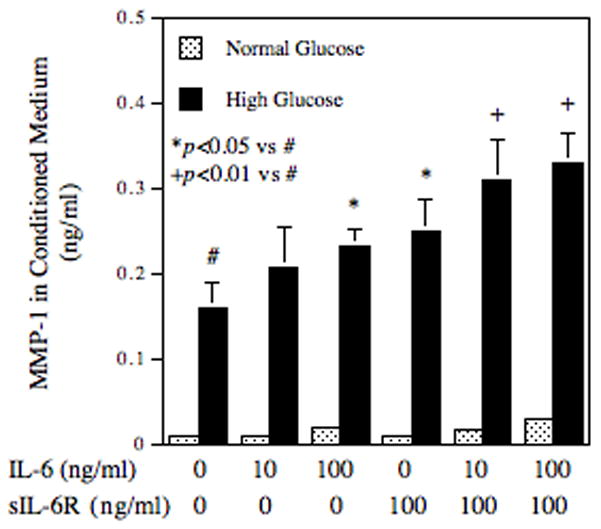

High Glucose augments IL-6-stimulated MMP-1 Secretion from Human Primary Monocytes

To determine if human monocytes respond to IL-6 and high glucose similarly as U937 mononuclear phagocytes, we challenged human primary monocytes pre-exposed to normal or high glucose with IL-6. Results showed that IL-6 at 100 ng/ml increased MMP-1 secretion significantly and high glucose markedly increased the stimulatory effect of IL-6 (Fig. 8). Since it has been reported that the addition of soluble IL-6 receptor (sIL-6R) is required to stimulate MMP-1 expression by IL-6 in gingival fibroblasts [Irwin et al., 2002], we further determined the effect of sIL-6R on IL-6-stimulated MMP-1 expression by human monocytes. Interestingly, sIL-6R by itself increased MMP-1 secretion and the combination of IL-6 and sIL-6R further increased MMP-1 secretion (Fig. 8). In contrast, addition of sIL-6R to U937 cells did not further increase IL-6-stimulated MMP-1 secretion (data not shown).

Figure 8.

Regulation of MMP-1 secretion from human primary monocytes by high glucose, IL-6 or both. Human monocytes pre-exposed to normal glucose (NG) or high glucose (HG) for 3 days were treated with different concentrations of IL-6, sIL-6R, or both for 24 h and the culture medium was collected after the treatment for quantification of MMP-1 using ELISA. The data (mean ± SD) presented are from one of two independent experiments with similar results.

DISCUSSION

The major finding from this study is that IL-6 and high glucose have synergistic effect on MMP expression by U937 mononuclear cells. The same observation was also made in human primary monocytes. Given the essential roles of IL-6 and MMP in tissue inflammation and destruction in inflammatory diseases such as cardiovascular disease and periodontal disease, this finding helps us understand why these diseases are more severe in diabetic patients who have poor glycemic control than nondiabetic patients.

The circulating levels of IL-6 are elevated years before onset of type 2 diabetes [Hu et al., 2004]. Therefore, elevated levels of IL-6 are considered as a predictor for type 2 diabetes in future [Hu et al., 2004]. Although the pathological role of IL-6 in type 2 diabetes has not been fully established, it is well documented that IL-6 is a major cytokine involved in the development and progression of diabetic complications including atherosclerosis [Dubinski and Zdrojewicz, 2007], retinopathy [Mysliwiec et al., 2008], nephropathy [Horii et al., 1993], and periodontal disease [Cole et al., 2008; Marcaccini et al., 2009]. For examples, a recent clinical study conducted in 306 patients with type 2 diabetes showed that plasma IL-6 level was significantly associated with coronary artery calcium score, which is associated with the risk of cardiovascular events, after adjustment for traditional cardiovascular risk factors [Saremi et al., 2009]. Our recent study showed that IL-6 expression in periodontal tissue was increased from control individuals who had neither periodontal disease nor diabetes to patients with periodontal disease alone and further increased in patients with both diabetes and periodontal disease [Cole et al., 2008], suggesting a role of IL-6 in the progression of periodontal disease in diabetic patients. Since it is known that MMPs play a crucial role in destabilization of atherosclerotic plaques [Libby, 2008] and advanced periodontal disease [Sorsa et al., 2006], the finding that high glucose enhances IL-6-stimulated MMP expression helps understand how hyperglycemia impacts the progression of atherosclerosis and periodontal disease in diabetic patients.

Another interesting observation from this study is that high glucose, IL-6 and LPS have synergistic effect on MMP-1 expression. It is known that LPS stimulates IL-6 expression by mononuclear cells. Thus, LPS and elevated level of IL-6 are likely to be present in the tissues infected by Gram-negative bacteria. For example, both LPS and IL-6 are present in diseased periodontal tissue of patients with periodontitis [Grossi and Genco, 1998]. Besides LPS and IL-6, elevated glucose levels are also present in diabetic patients with poor glycemic control. Although it is known that hyperglycemia, LPS and IL-6 all promote inflammation in atherosclerosis and periodontal disease, it remains undetermined whether they act independently or cooperatively. In the present study, we demonstrated that high glucose, IL-6 and LPS stimulated MMP-1 secretion by 1.4-, 3.9-, 6.1-fold, respectively, after 24 h treatment, but their combination led to a 53.3-fold increase. These results clearly show a remarkable synergism between high glucose, IL-6, and LPS on MMP-1 expression and may explain, at least partially, why inflammation-related diseases such as periodontal disease are more severe in diabetic patients.

By binding to IL-6 receptor complex, IL-6 triggers signal transduction cascades through JAK and STAT3, which in turn translocates to nucleus, binds to IL-6 response element (IRE), and activates gene expression [Schuringa et al., 2001]. In addition to the JAK/STAT3 pathway, IL-6 also activates MAPK pathways [Daeipour et al., 1993]. Studies have shown that the JAK/STAT3 and MAPK signaling pathways mediate different gene expression stimulated by IL-6. For example, it was reported that IL-6 stimulated fibrinogen expression via STAT3 that bound to the conserved IRE motif (CTGGGAA) in the promoter of fibrinogen gene [Fuller and Zhang, 2001]. Similarly, IL-6 upregulated myeloid cell leukemia-1 (Mcl-1) protein, an antiapoptotic member of the BCL-2 family [Kozopas et al., 1993], through the JAK/STAT3 pathway [Puthier et al., 1999]. On the other hand, IL-6 induced the expression of peripherin, a type of intermediate filament involved in neuronal differentiation, through MAPK pathway [Sterneck et al., 1996]. Similarly, our present study showed that IL-6 stimulated MMP-1 expression through the ERK and JNK pathways, but not JAK/STAT3. These findings suggest that upon activation by IL-6, JAK/STAT3 and MAPK pathways mediate expression of various genes involved in different cellular functions. Thus, by blocking one of these signaling pathways, we can target certain genes and control specific cell functions.

It is noteworthy that as shown in Fig. 4, the ERK and JNK pathways are not specifically involved in high glucose/IL-6-stimulated MMP-1 expression. They are also required for the basal MMP-1 expression. The basal MMP-1 expression by U937 cells is defined as the amount of MMP-1 released in the absence of high glucose and IL-6 and likely regulated by 5 mM of glucose and some unknown factors in the fetal bovine serum as well as some cytokines released by U937 cells during 24 h incubation. It is possible that these factors may also regulate MMP-1 secretion through ERK and JNK pathways. In our recent study on the coculture of U937 cells and fibroblasts, we observed that ERK and JNK pathways were involved in both basal and fibroblast-conditioned medium-stimulated MMP-1 expression by U937 cells [Sundararaj et al., 2009]. This study showed that IL-6 released by fibroblasts played an essential role in stimulation of MMP-1 expression by U937 cells. It seems that the findings about the role of ERK and JNK pathways in the basal and high glucose/IL-6-stimulated MMP-1 expression from the present study are consistent with those reported in this paper.

Previous studies from our and other groups have shown that high glucose increases AP-1 transcriptional activity [Kreisberg et al., 1994; Nareika et al., 2008]. In the present study, we further demonstrated that high gluocse increased both c-Jun and c-Fos expression by U937 mononuclear phagocytes (Fig. 5). Interestingly, the combination of high glucose and IL-6 only further increased c-Jun, but not c-Fos, expression, suggesting that c-Jun is involved in the augmentation of IL-6-stimulated MMP-1 expression by high glucose. Since it is known that AP-1 can be formed by not only heterodimers of c-Jun and c-Fos, but also monodimers of two c-Jun molecules, it is likely that increased c-Jun expression by high glucose and IL-6 may lead to an increased AP-1 level and subsequent AP-1-dependent transcription of MMP-1 expression. The role of c-Jun in MMP-1 expression in response to IL-6 and high glucose was confirmed by our studies showing that suppression of c-Jun expression by RNA interference resulted in a significant reduction of MMP-1 expression. Furthermore, our results showed that JNK pathway is involved in IL-6-stimulated MMP-1 expression (Fig. 4). Since it is known that JNK is required for c-Jun activation, it is likely that while the combination of IL-6 and high glucose increases c-Jun expression, IL-6 triggers JNK signaling activation that further phosphorylates c-Jun and thereby increases AP-1 activity.

Although Fig. 1 and Fig. 8 showed that high glucose augmented IL-6-stimulated MMP-1 secretion from both U937 cells and human monocytes, the cellular responses to high glucose and IL-6 are quite different between these two types of cells. The major differences are that high glucose increases more MMP-1 in human monocytes while IL-6 stimulates more MMP-1 in U937 cells. It is likely that human monocytes have less surface IL-6 receptor α chain expression than U937 cells and thus sIL-6R complexed with IL-6 are able to engage gp130 to trigger signaling activation in humam monocytes. In recent years, studies have documented a “trans-signaling” process in which IL-6 and sIL-6R form a complex that engages gp130, the signaling component of IL-6R, to elicit signaling for gene expression [Jones et al., 2005; Rabe et al., 2008]. Irwin and coworkers reported that sIL-6R was required for stimulation of MMP-1 expression by IL-6 in gingival fibroblasts [Irwin et al., 2002]. For human primary monocytes, our present study showed that IL-6 stimulated MMP-1 secretion and the addition of sIL-6R further increased MMP-1 secretion (Fig. 8), suggesting that the surface expression of IL-6Rα may not be sufficient for IL-6 binding. However, since it is known that high levels of sIL-6R up to 100 ng/ml are present in human serum [Honda et al., 1992], IL-6 and sIL-6R are likely to form complexes, which in turn trigger a trans-signaling through gp130, leading to MMP-1 expression. For U937 mononuclear phagocytes, it is possible that the surface expression of IL-6R is sufficient for IL-6 binding and therefore, the addition of sIL-6R does not further enhance IL-6-stimulated MMP-1 expression. Despite the difference in the cellular response to sIL-6R between U937 cells and primary monocytes, our present study showed that both cells responded to IL-6 and high glucose similarly in MMP-1 secretion.

In conclusion, the present study has shown that IL-6 is a potent stimulator for MMP expression by mononuclear phagocytes and high glucose further amplifies the stimulatory effect of IL-6. Thus, targeting IL-6 may be an effective strategy to control tissue destruction in inflammation-associated diseases such as cardiovascular disease and periodontal disease in diabetic patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Merit Review Grant from Department of Veterans Affairs and NIH grant DE16353 (to Y.H.).

References

- Aggarwal BB, Shishodia S, Takada Y, Banerjee S, Newman RA, Bueso-Ramos CE, Price JE. Curcumin suppresses the paclitaxel-induced nuclear factor-kappaB pathway in breast cancer cells and inhibits lung metastasis of human breast cancer in nude mice. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2005;11:7490–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caceres-Cortes JR. A potent anti-carcinoma and anti-acute myeloblastic leukemia agent, AG490. Anti-cancer agents in medicinal chemistry. 2008;8:717–22. doi: 10.2174/187152008785914752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole CM, Sundararaj KP, Leite RS, Nareika A, Slate EH, Sanders JJ, Lopes-Virella MF, Huang Y. A trend of increase in periodontal interleukin-6 expression across patients with neither diabetes nor periodontal disease, patients with periodontal disease alone, and patients with both diseases. Journal of periodontal research. 2008;43:717–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2008.01082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daeipour M, Kumar G, Amaral MC, Nel AE. Recombinant IL-6 activates p42 and p44 mitogen-activated protein kinases in the IL-6 responsive B cell line, AF-10. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 1993;150:4743–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson DA, Iles KE, Zhang H, Blank V, Forman HJ. Curcumin alters EpRE and AP-1 binding complexes and elevates glutamate-cysteine ligase gene expression. The FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2003;17:473–5. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0566fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogan A, Tuzun N, Turker Y, Akcay S, Kaya S, Ozaydin M. Matrix metalloproteinases and inflammatory markers in coronary artery ectasia: their relationship to severity of coronary artery ectasia. Coronary artery disease. 2008;19:559–63. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0b013e3283109079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubinski A, Zdrojewicz Z. The role of interleukin-6 in development and progression of atherosclerosis. Polski merkuriusz lekarski: organ Polskiego Towarzystwa Lekarskiego. 2007;22:291–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller GM, Zhang Z. Transcriptional control mechanism of fibrinogen gene expression. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2001;936:469–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geivelis M, Turner DW, Pederson ED, Lamberts BL. Measurements of interleukin-6 in gingival crevicular fluid from adults with destructive periodontal disease. Journal of periodontology. 1993;64:980–3. doi: 10.1902/jop.1993.64.10.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossi SG, Genco RJ. Periodontal disease and diabetes mellitus: a two-way relationship. Annals of periodontology/the American Academy of Periodontology. 1998;3:51–61. doi: 10.1902/annals.1998.3.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda M, Yamamoto S, Cheng M, Yasukawa K, Suzuki H, Saito T, Osugi Y, Tokunaga T, Kishimoto T. Human soluble IL-6 receptor: its detection and enhanced release by HIV infection. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 1992;148:2175–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horii Y, Iwano M, Hirata E, Shiiki M, Fujii Y, Dohi K, Ishikawa H. Role of interleukin-6 in the progression of mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis. Kidney international Supplement. 1993;39:S71–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu FB, Meigs JB, Li TY, Rifai N, Manson JE. Inflammatory markers and risk of developing type 2 diabetes in women. Diabetes. 2004;53:693–700. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.3.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Van den Steen PE, Sang QX, Opdenakker G. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors as therapy for inflammatory and vascular diseases. Nature reviews. Drug discovery. 2007;6:480–98. doi: 10.1038/nrd2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin CR, Myrillas TT, Traynor P, Leadbetter N, Cawston TE. The role of soluble interleukin (IL)-6 receptor in mediating the effects of IL-6 on matrix metalloproteinase-1 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 expression by gingival fibroblasts. Journal of periodontology. 2002;73:741–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.2002.73.7.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara K, Hirano T. IL-6 in autoimmune disease and chronic inflammatory proliferative disease. Cytokine & growth factor reviews. 2002;13:357–68. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(02)00027-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SA, Richards PJ, Scheller J, Rose-John S. IL-6 transsignaling: the in vivo consequences. Journal of interferon & cytokine research: the official journal of the International Society for Interferon and Cytokine Research. 2005;25:241–53. doi: 10.1089/jir.2005.25.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Kim Y, Lee Y, Chung JH. Ceramide accelerates ultraviolet-induced MMP-1 expression through JAK1/STAT-1 pathway in cultured human dermal fibroblasts. Journal of lipid research. 2008;49:2571–81. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800112-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishimoto T. Interleukin-6: discovery of a pleiotropic cytokine. Arthritis research & therapy. 2006;8(Suppl 2):S2. doi: 10.1186/ar1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozopas KM, Yang T, Buchan HL, Zhou P, Craig RW. MCL1, a gene expressed in programmed myeloid cell differentiation, has sequence similarity to BCL2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1993;90:3516–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreisberg JI, Radnik RA, Ayo SH, Garoni J, Saikumar P. High glucose elevates c-fos and c-jun transcripts and proteins in mesangial cell cultures. Kidney international. 1994;46:105–12. doi: 10.1038/ki.1994.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JC, Laydon JT, McDonnell PC, Gallagher TF, Kumar S, Green D, McNulty D, Blumenthal MJ, Heys JR, Landvatter SW, et al. A protein kinase involved in the regulation of inflammatory cytokine biosynthesis. Nature. 1994;372:739–46. doi: 10.1038/372739a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppert D, Lindberg RL, Kappos L, Leib SL. Matrix metalloproteinases: multifunctional effectors of inflammation in multiple sclerosis and bacterial meningitis. Brain research. Brain research reviews. 2001;36:249–57. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00101-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby P. The molecular mechanisms of the thrombotic complications of atherosclerosis. Journal of internal medicine. 2008;263:517–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.01965.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe GD. The relationship between infection, inflammation, and cardiovascular disease: an overview. Annals of periodontology/the American Academy of Periodontology. 2001;6:1–8. doi: 10.1902/annals.2001.6.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manicone AM, McGuire JK. Matrix metalloproteinases as modulators of inflammation. Seminars in cell & developmental biology. 2008;19:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcaccini AM, Meschiari CA, Sorgi CA, Saraiva MC, de Souza AM, Faccioli LH, Tanus-Santos JE, Novaes AB, Gerlach RF. Circulating interleukin-6 and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein decrease after periodontal therapy in otherwise healthy subjects. Journal of periodontology. 2009;80:594–602. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.080561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moutsopoulos NM, Madianos PN. Low-grade inflammation in chronic infectious diseases: paradigm of periodontal infections. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2006;1088:251–64. doi: 10.1196/annals.1366.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mysliwiec M, Balcerska A, Zorena K, Mysliwska J, Lipowski P, Raczynska K. The role of vascular endothelial growth factor, tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-6 in pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes research and clinical practice. 2008;79:141–6. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nareika A, He L, Game BA, Slate EH, Sanders JJ, London SD, Lopes-Virella MF, Huang Y. Sodium lactate increases LPS-stimulated MMP and cytokine expression in U937 histiocytes by enhancing AP-1 and NF-kappaB transcriptional activities. American journal of physiology. Endocrinology and metabolism. 2005;289:E534–42. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00462.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nareika A, Im YB, Game BA, Slate EH, Sanders JJ, London SD, Lopes-Virella MF, Huang Y. High glucose enhances lipopolysaccharide-stimulated CD14 expression in U937 mononuclear cells by increasing nuclear factor kappaB and AP-1 activities. The Journal of endocrinology. 2008;196:45–55. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nareika A, Maldonado A, He L, Game BA, Slate EH, Sanders JJ, London SD, Lopes-Virella MF, Huang Y. High glucose-boosted inflammatory responses to lipopolysaccharide are suppressed by statin. Journal of periodontal research. 2007;42:31–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2006.00911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura F, Takahashi K, Kurihara M, Takashiba S, Murayama Y. Periodontal disease as a complication of diabetes mellitus. Annals of periodontology/the American Academy of Periodontology. 1998;3:20–9. doi: 10.1902/annals.1998.3.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puthier D, Bataille R, Amiot M. IL-6 up-regulates mcl-1 in human myeloma cells through JAK/STAT rather than ras/MAP kinase pathway. European journal of immunology. 1999;29:3945–50. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199912)29:12<3945::AID-IMMU3945>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabe B, Chalaris A, May U, Waetzig GH, Seegert D, Williams AS, Jones SA, Rose-John S, Scheller J. Transgenic blockade of interleukin 6 transsignaling abrogates inflammation. Blood. 2008;111:1021–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-102137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattazzi M, Puato M, Faggin E, Bertipaglia B, Zambon A, Pauletto P. C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 in vascular disease: culprits or passive bystanders? Journal of hypertension. 2003;21:1787–803. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200310000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogus JJ, Warram JH, Krolewski AS. Genetic studies of late diabetic complications: the overlooked importance of diabetes duration before complication onset. Diabetes. 2002;51:1655–62. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.6.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusconi F, Parizzi F, Garlaschi L, Assael BM, Sironi M, Ghezzi P, Mantovani A. Interleukin 6 activity in infants and children with bacterial meningitis. The Collaborative Study on Meningitis. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 1991;10:117–21. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199102000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saremi A, Anderson RJ, Luo P, Moritz TE, Schwenke DC, Allison M, Reaven PD. Association between IL-6 and the extent of coronary atherosclerosis in the veterans affairs diabetes trial (VADT) Atherosclerosis. 2009;203:610–4. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuringa JJ, Timmer H, Luttickhuizen D, Vellenga E, Kruijer W. c-Jun and c-Fos cooperate with STAT3 in IL-6-induced transactivation of the IL-6 respone element (IRE) Cytokine. 2001;14:78–87. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2001.0856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seager Danciger J, Lutz M, Hama S, Cruz D, Castrillo A, Lazaro J, Phillips R, Premack B, Berliner J. Method for large scale isolation, culture and cryopreservation of human monocytes suitable for chemotaxis, cellular adhesion assays, macrophage and dendritic cell differentiation. Journal of immunological methods. 2004;288:123–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorsa T, Tjaderhane L, Konttinen YT, Lauhio A, Salo T, Lee HM, Golub LM, Brown DL, Mantyla P. Matrix metalloproteinases: contribution to pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment of periodontal inflammation. Annals of medicine. 2006;38:306–21. doi: 10.1080/07853890600800103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterneck E, Kaplan DR, Johnson PF. Interleukin-6 induces expression of peripherin and cooperates with Trk receptor signaling to promote neuronal differentiation in PC12 cells. Journal of neurochemistry. 1996;67:1365–74. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67041365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundararaj KP, Samuvel DJ, Li Y, Nareika A, Slate EH, Sanders JJ, Lopes-Virella MF, Huang Y. Simvastatin suppresses LPS-induced MMP-1 expression in U937 mononuclear cells by inhibiting protein isoprenylation-mediated ERK activation. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2008;84:1120–9. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0108064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundararaj KP, Samuvel DJ, Li Y, Sanders JJ, Lopes-Virella MF, Huang Y. Interleukin-6 released from fibroblasts is essential for up-regulation of matrix metalloproteinase-1 expression by U937 macrophages in coculture: cross-talking between fibroblasts and U937 macrophages exposed to high glucose. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2009;284:13714–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806573200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundstrom C, Nilsson K. Establishment and characterization of a human histiocytic lymphoma cell line (U-937) International journal of cancer. Journal international du cancer. 1976;17:565–77. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910170504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincenti MP, White LA, Schroen DJ, Benbow U, Brinckerhoff CE. Regulating expression of the gene for matrix metalloproteinase-1 (collagenase): mechanisms that control enzyme activity, transcription, and mRNA stability. Critical reviews in eukaryotic gene expression. 1996;6:391–411. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v6.i4.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan C, Boyd DD. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinase gene expression. Journal of cellular physiology. 2007;211:19–26. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yawata H, Yasukawa K, Natsuka S, Murakami M, Yamasaki K, Hibi M, Taga T, Kishimoto T. Structure-function analysis of human IL-6 receptor: dissociation of amino acid residues required for IL-6-binding and for IL-6 signal transduction through gp130. The EMBO journal. 1993;12:1705–12. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05815.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]