Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to examine whether integrating depression treatment into care for Type 2 diabetes mellitus among older African-Americans improved medication adherence, glycemic control, and depression outcomes.

Methods

Older African-Americans prescribed pharmacotherapy for Type 2 diabetes mellitus and depression from physicians at a large primary care practice in West Philadelphia were randomly assigned to an integrated care intervention or usual care. Adherence was assessed at baseline, 2, 4, and 6 weeks using the Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS) to assess adherence. Outcomes assessed at baseline and 12 weeks included standard laboratory tests to measure glycemic control and the Center Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) to assess depression.

Results

In all, 58 participants aged 50 to 80 years participated. The proportion of participants who had 80% or greater adherence to an oral hypoglycemic (intervention 62.1% vs. usual care 24.1%) and an antidepressant (intervention 62.1% vs. usual care 10.3%) was greater in the intervention group in comparison with the usual care group at 6 weeks. Participants in the integrated care intervention had lower levels of glycosylated hemoglobin (intervention 6.7% vs. usual care 7.9%) and fewer depressive symptoms (CES-D mean scores, intervention 9.6 vs. usual care 16.6) compared with participants in the usual care group at 12 weeks.

Conclusion

A pilot randomized controlled trial integrating Type 2 diabetes mellitus treatment and depression was successful in improving outcomes among older African-Americans. Integrated interventions may be more feasible and effective in real world practices with competing demands for limited resources.

Introduction

Older African-Americans are twice as likely as to be diagnosed with diabetes and are over two times as likely to die from diabetes in comparison with non-Hispanic whites.1 By 2050 it is estimated that the number of older adults in developed countries with diabetes will increase by 220%2 yet the proportion of adults whose diabetes is controlled is decreasing over time3 and is particularly low among older African-Americans.4 Depression is common among African-Americans with diabetes.5 Depression is a risk factor for diabetes6 and risk of depression is increased by a factor of two in older patients with diabetes.7 Depression has been specifically linked to prognostic variables in diabetes such as micro- and macrovascular complications8 and is associated with poor adherence to medications for diabetes.9

The 2002 Institute of Medicine (IOM) Report commissioned by the United States Congress, Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care reported significant health disparities in the treatment of illness and delivery of care across ethnic groups, with diabetes and mental health being no exception.10 African-American patients with diabetes have been found to receive lower quality care, have more visits to the emergency department and fewer physician visits per year.11, 12 With regard to depression, while the United States seen an overall increase in antidepressant use, the increase has occurred mostly among white patients.13 African-American patients have been found to be less adherent to diabetes and depression treatment regimens, even though no ethnicity-related treatment response difference has been identified.14, 15

The primary health care setting is pivotal for the identification and treatment of diabetes and co-morbid mental disorders for elderly minorities. Despite startling ethnic disparities in diabetes outcomes,16 African-Americans are just as likely as whites to be seen in primary care for the management of diabetes.17, 18 In addition, African-American patients are more likely to seek mental health care from a primary care physician rather than a mental health specialist.19, 20 However, behavioral interventions in primary care to improve compliance to Type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) treatment have been more effective for whites than African-Americans which may be due to a failure to incorporate factors that have been found to increase engagement and adherence among African-Americans, namely integrated designs21, 22 and cultural tailoring.22-27

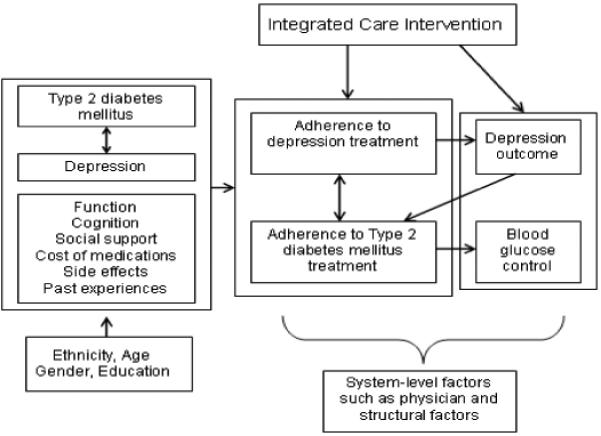

No known trials in primary care have integrated management of Type 2 DM and depression among older African-Americans. Improving the ability of primary care settings to integrate the management of Type 2 DM and depression among older African-Americans will have an important public health impact. There is an urgent need for research that can bring potentially life-extending strategies28 to the management of both diabetes and depression. The aim of this intervention was to focus on improving medication adherence to both Type 2 DM and depression treatment among older African-Americans. Adherence remains a significant impediment to improving care29, 30 and is an important predictor of glycemic control.31, 32 The conceptual framework, adapted from Cooper and colleagues,33 is practical in its approach and provides a framework that allows for flexible, tailored interventions (Figure 1). The intervention addresses each factor resulting in nonadherence in the conceptual model through a multifaceted, culturally tailored individualized approach in which participants work with the integrated care manager to develop strategies to overcome barriers to medication adherence. The purpose of the study was to examine whether integrating depression treatment into care for Type 2 diabetes mellitus among older African-Americans improved medication adherence, glycemic control, and depression outcomes.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework adapted from Cooper et al.33

Hypothesis

The hypothesis was that in a sample of older African-American primary care patients with Type 2 DM and depression, patients who were randomized to receive the intervention compared with usual care would demonstrate the following adherence outcomes at 6 weeks: (1) a greater proportion of participants who had 80% or greater adherence to an oral hypoglycemic agent and (2) a greater proportion of participants who had 80% or greater adherence to an antidepressant medication, and the following clinical outcomes at 12 weeks: (1) lower amounts of glycosylated hemoglobin in their blood and (2) fewer depressive symptoms.

Methods

Recruitment Procedures

Patients were recruited from a community-based primary care practice in West Philadelphia with 12 family physicians. Over 30,000 patient visits occur per year at the practice. The research protocols were approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board and all participants gave written informed consent. From April 2007 to June 2008, depressed older adults with Type 2 diabetes mellitus with upcoming appointments were recruited. Patients were initially identified through an electronic medical record with the following inclusion criteria: (1) aged 50 and older; (2) a Hba1c ≥ 7 at their last primary care office visit or a prescription for an oral hypoglycemic agent within the past year; and (3) a diagnosis of depression or a prescription for an antidepressant within the past year.

In all, 90 patients were identified by electronic medical records as potentially eligible and were approached for further screening. Of those approached, 63 (70.0%) provided oral consent for screening. Fifty-eight (92.1%) of the 63 who consented for screening were deemed eligible for participation. In order to include as many older persons who were willing and able to participate as possible participants with a range of depressive symptoms were included in this study, reflecting the concept of the relapsing, remitting nature of depression in primary care.34 In all, 58 eligible African-American patients completed enrollment procedures and were randomly assigned to an integrated care intervention (n=29) or to usual care (n=29).

Intervention

Integrated care can be defined as a set of techniques and organizational models to create connectivity, alignment, and collaboration within and between the cure and care sectors at the funding, administrative, and/or provider levels.35 The goals of integrated care generally are to enhance quality of care and quality of life, consumer satisfaction, system efficiency for patients with complex problems cutting across multiple sectors and providers.36, 37 Relying on this framework, an integrated care intervention was carried out in which an integrated care manager collaborated with physicians to help participants recognize depression in the context of Type 2 DM, offered guideline-based treatment recommendations, monitored adherence and clinical status, and provided appropriate follow-up. This study differed from other studies by focusing on the integrated care manager’s unique role as an intermediary or liaison between the elderly depressed patient with Type 2 DM and the physician in promoting adherence to an oral hypoglycemic agent and antidepressant. The key components of the Integrated Care Intervention were: (1) provision of an individualized program to improve adherence to oral hypoglycemic agents and antidepressants that recognizes patients’ social and cultural context; and (2) integration of Type 2 DM treatment with depression management.

The integrated care manager worked individually with patients to address the factors involved in adherence presented in the conceptual model (Figure 1). Through in-person sessions and telephone conversations the integrated care manager provided education about depression and Type 2 DM emphasizing the importance of controlling depression in order to manage Type 2 DM; encouragement and relief from stigma; help to identify target symptoms for both conditions; explanations for the rationale for oral hypoglycemic agent and antidepressant usage; assessment for the presence of side-effects and assistance in their management; assessment for progress (e.g. improvement in finger-stick glucose measurements and reduction in depressive symptoms); assistance with referrals and; monitoring and response to life-threatening symptoms (e.g. chest pain, suicidality). The Integrated Care Manager conducted cultural interviewing to assist participants in devising culturally acceptable solutions to nonadherence. Diabetes information for participants was tailored to the cultural context of participants.38 The intervention was presented to patients as a supplement to, rather than a replacement for, existing primary care treatment. A multi-faceted approach was employed because education alone has not been found to be effective for improving adherence.39

The intervention consisted of three 30 minute in-person sessions and two 15-minute telephone monitoring contacts over a four-week period. A Master’s level research coordinator was trained as an integrated care manager and administered all study activities. Prior to trial initiation, the integrated care manager received training on pharmacotherapy for Type 2 diabetes mellitus and depression management, cultural interviewing and sensitivity, and culturally competent evidence-based practices for quickly building rapport in the primary care settings40-45 during weekly clinical sessions with the principal investigator (PI). Under the supervision of the PI the integrated care manager conducted mock study activities with two participants and thereafter received ongoing weekly supervision for all study activities monitoring 25% of weekly sessions to ensure that the integrated care manager was adherent to study protocols.

Usual Care

At baseline, 2, 4, 6, and 12 weeks participants underwent the same assessments as participants in the integrated care intervention. Assessments were conducted in-person (as were assessments in the integrated care intervention). The PI randomly monitored 25% of sessions conducted weekly to ensure that there was no carry-over of the intervention into the usual care group.

Measurement Strategy

To screen potential participants the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) assessed for the presence of mania or hypomania, psychotic syndrome, alcohol abuse or dependence, acutely suicidal or psychotic thoughts.46 The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), a short standardized mental status examination widely employed for clinical and research purposes,47 was used to evaluate cognitive impairment (defined as MMSE < 21).48 Patients were asked whether patients resided in a care facility that provided their medications on schedule and whether they were unwilling or unable to use Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS).

At baseline sociodemographic characteristics were assessed using standard questions. Functional status was measured using the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form (SF-36).49, 50 Adherence to an oral hypoglycemic agent and an antidepressant medication was measured at baseline, 2, 4, and 6 weeks. Adherence to oral hypoglycemic agents and antidepressants was measured using electronic monitoring data obtained from MEMS Caps. MEMS Caps are medication bottle caps containing microelectronics that record the date and time the bottle is opened. MEMS caps are an informative technique allowing identification of the precise time of container opening when medications are taken. At baseline and 12 weeks blood glycemic control was assessed in accordance with American Diabetes Association Guidelines.51 Hba1c assays were performed at a single, accredited laboratory using a standard liquid chromatographic method to measure Hbalc.52 The assay methodology did not change during the study period. At baseline and 12 weeks the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) was employed to measure depression. The Centers for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) scale was developed by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies at the National Institute of Mental Health for use in studies of depression in community samples.53-55 The CES-D contains 20 items. The CES-D has been employed in studies of older adults.56, 57

Analytic strategy

Characteristics of participants at baseline in the integrated care intervention or usual care were compared using the Mann-Whitney U and Fisher’s exact test (for continuous or categorical variables as appropriate). In addition, characteristics of participants who refused and did not refuse participation in the study were compared using the Mann-Whitney U and Fisher’s exact tests. Blood glycemic control and depressive symptoms were compared in the intervention group and usual care groups using the Mann-Whitney U test at 12 weeks. Adherence was defined as the percent of prescribed doses taken and was calculated as the number of doses taken divided by the number of doses prescribed over the observation period *100%. Adherence was dichotomized at a threshold of 80% because the proportion of pills taken was highly skewed and failed normality assumptions. The 80% cut-point has been used as a threshold to assess adherence to medication regimens.58 Fisher’s exact test was employed to compare the proportion of participants who were adherent to oral hypoglycemic agents and antidepressants in the intervention group with the usual care group at 6 weeks. Analysis was conducted using SPSS version 12.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). A level of statistical significance set at α = 0.05 was employed, recognizing that tests of statistical significance are approximations that serve as aids to interpretation and inference.

Results

Sample characteristics

Participants ranged from 50 to 80 years old, with an average age of 60.2 years (SD=7.4 years). Forty-nine (84.5%) of the 58 participants were women. Characteristics of participants in the integrated care intervention did not differ significantly from participants in the usual care group (Table 1). There were no statistically significant differences in characteristics of patients who provided oral consent for screening and those who did not. All participants attended the required sessions at baseline, 2, 4 and 6 weeks as well as the final follow-up at 12 weeks and continued to receive regular care from their primary care physician and other medical specialists.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics at baseline (n=58). P-values represent comparisons according to Fisher’s exact and Mann Whitney U tests for categorical or continuous data, respectively

| Intervention (n=29) |

Usual Care (n=29) |

P value |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||

| Age, years (s.d.) | 61.6 (8.3) | 58.3 (6.3) | .26 |

| Gender, women n (%) | 24 (82.8%) | 25 (86.2%) | .50 |

| Less than HS education, n (%) | 8 (27.6%) | 5 (17.2%) | .27 |

| Lives alone, n (%) | 16 (55.2%) | 11 (37.9%) | .15 |

| SF-36 scores | |||

| Physical function score, mean (s.d.) | 43.8 (30.3) | 55.3 (38.2) | .33 |

| Social function score, mean (s.d.) | 80.0 (29.8) | 77.9 (39.8) | .46 |

| Role physical score, mean (s.d.) | 44.0 (39.9) | 65.5 (42.5) | .05 |

| Role emotional score, mean (s.d.) | 66.7 (43.6) | 79.3 (39.3) | .21 |

| Bodily pain score, mean (s.d.) | 46.2 (32.6) | 55.2 (36.5) | .29 |

| Other covariates | |||

| MMSE, mean (s.d.) | 27.2 (2.8) | 28.3 (1.9) | .10 |

| Number of medications, n (s.d.) | 10.2 (3.3) | 7.7 (3.2) | .03 |

| Outcome measures | |||

| Hba1c, mean (s.d.) | 7.3 (2.3) | 7.3 (2.0) | .70 |

| CES-D, mean (s.d.) | 15.6 (11.7) | 19.7 (16.7) | .47 |

| ≥ 80% adherent to oral hypoglycemic, n (%) | 10 (34.5%) | 6 (20.7%) | .19 |

| ≥ 80% adherent to antidepressant, n (%) | 8 (27.6%) | 4 (13.8%) | .17 |

Abbreviations: HS, high school; s.d., standard deviation; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; Hb, Hemoglobin; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale.

Outcomes

The proportion of participants who had 80% or greater adherence to an oral hypoglycemic agent was greater in the intervention group in comparison with the usual care group at 6 weeks (intervention 62.1% vs. usual care 24.1%; p<.01). The proportion of participants who had 80% or greater adherence to an antidepressant was greater in the intervention group in comparison with the usual care group at 6 weeks (intervention 62.1% vs. usual care 10.3%; p<.001). Participants who received the intervention had lower amounts of glycosylated hemoglobin in their blood (intervention 6.7% vs. usual care 7.9%; p<.05) in comparison with participants in the usual care group at 12 weeks. Participants randomized to the intervention group had fewer depressive symptoms in comparison with participants in the usual care group at 12 weeks (CES-D mean scores, intervention 6.9 vs. usual care 16.6; p=.04) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Adherence to oral hypoglycemic agents and antidepressants of older African-American participants in usual care and in the integrated intervention at 6 weeks. Glycemic control and depression symptoms of older African-American participants in usual care and in the integrated intervention at 12 weeks (n=58). P-values represent statistical tests employing Mann Whitney U tests for continuous measures and the Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables

| Intervention (n=29) |

Usual Care (n=29) |

P value |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Hba1c, mean (s.d.) | 6.7 (2.3) | 7.9 (2.6) | .019 |

| CES-D, mean (s.d.) | 9.6 (9.4) | 16.6 (14.5) | .035 |

|

≥ 80% adherent to oral hypoglycemic, n (%) |

18 (62.1%) | 7 (24.1%) | .004 |

|

≥ 80% adherent to antidepressant, n (%) |

18 (62.1%) | 3 (10.3%) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: Hb, hemoglobin; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; s.d., standard deviation.

Conclusion

This preliminary pilot study supports the usefulness of a brief primary care based integrated care intervention to improve adherence to oral hypoglycemic agents and antidepressants, blood glycemic control, and depression symptoms among older African-Americans. Primary care older African-American patients randomized to an integrated care intervention in comparison with older African-American patients randomized to usual care showed higher rates of adherence to oral hypoglycemic agents and antidepressants at 6 weeks and lower amounts of glycosylated hemoglobin in their blood and fewer depressive symptoms at 12 weeks.

Before discussing the implications of the findings, the limitations of this study require discussion. First, the results were obtained from patients who received care at one primary care site that might not be representative of most primary care practices. However, this practice was probably similar to other primary care practices in the region. Second, this preliminary investigation was limited to 58 participants and the follow-up period was short, but the participants were randomized to the intervention or usual care. Third, the intervention would require additional resources in primary care settings. However, the intervention has a simple design and future implementation will explore whether ancillary health personnel could be trained to carry out the intervention. Fourth, MEMS Caps were used to measure adherence. All methods for assessing adherence have limitations. MEMS caps were used as the primary measure of adherence because MEMS caps have a low failure rate58 and may be more sensitive than other adherence measures.59 In addition, prior studies have shown that MEMS caps do not significantly influence adherence.58, 60 Also, any effect of MEMS caps on medication adherence would be experienced equally in both groups and therefore would not influence a comparative assessment by randomization assignment. The adherence threshold of was 80% in this analysis. While this threshold has been assessed in some clinical research,58 the clinical relevance of this threshold has not been tested for many medications. Lastly, psychological variables, such as depression, cannot be observed directly and the measures employed may not reflect the construct being measuring.

Despite the limitations of this study, findings from this study deserve attention because previous intervention trials to reduce the burden of Type 2 DM in primary care targeting older African-Americans have not addressed depression.61-66 Integrated interventions may be more feasible and effective in real world practices with competing demands for limited resources and have been found to be more engaging and acceptable to African-Americans.21, 22, 67 In this intervention, depression treatment was integrated into care for Type 2 DM so a single program could assist older African-Americans with Type 2 DM and depression. Consistent with the hypothesis patients randomized to the integrated intervention had a greater proportion of participants with 80% or greater adherence to an oral hypoglycemic agent and an antidepressant at 6 weeks as well as lower amounts of glycosylated hemoglobin and fewer depressive symptoms in their blood at 12 weeks.

A recent review of diabetes self-management interventions noted that an assessment of the feasibility of many interventions is limited by failure to report overall contact time with study participants.68 The total contact time for this study was 2 hours (three 30 minute in-person meetings and two 15 minute telephone contacts). The minimal time involved in the study implementation supports prior findings that integrated interventions may provide a feasible and effective solution in real world practices with competing demands for limited resources.69 Another distinguishing factor of this intervention was the high retention rate of study participants (100%). The high retention rate is aligned with findings indicating that older primary care patients are more likely to be engaged in integrated care than other forms of care provision70 and integrated care models are particularly effective in improving access to and participation in mental health services among African American primary care patients.21

Interventions to narrow ethnic disparities have addressed patient-level, health care system-level, and community-level factors. This study sought to modify the health behaviors of individual patients and evaluated the effectiveness of a relatively brief pilot randomized controlled trial with a focus on adherence for the management of Type 2 DM as well as depression in older African-American primary care patients. Further research is needed to evaluate this intervention in a larger, more representative sample, with longer periods of follow-up. Although statistically significant clinical outcomes were found at 12 weeks, the pilot results did not provide information on how long the improvement might continue or the maximal improvement. Finding similar results in a larger sample over a longer follow-up period would provide information for primary health care practices and providers on possible approaches to the care of depressed older African-Americans with Type 2 DM.

Implications for Practice

Depressed older African-Americans with Type 2 DM randomized to an integrated care intervention in comparison with depressed older African-Americans with Type 2 DM randomized to usual care demonstrated improved medication adherence and clinical outcomes. Because the sample was derived from primary health care, the public health significance is high. Further research supporting the extent of the clinical benefit of this intervention in primary care is the first step in implementing this type of program. Future investigations could explore enhancing and sustaining the effect of the intervention for example through the training of ancillary health personnel, such as Licensed Practical Nurses, who are already working in primary care practices to carry out the intervention. These findings should propel the development and dissemination of models of care that better integrate depression management for African-Americans with diabetes and other chronic conditions.

Acknowledgements

Our work was supported by an American Diabetes Association Clinical Research Award and an Institute on Aging, University of Pennsylvania, Pilot Research Grant.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.OMH [Accessed April 22];African-American profile: The Office of Minority Health. 2009 www.omhrc.gov.

- 2.Narayan KM, Boyle JP, Geiss LS, Saaddine JB, Thompson TJ. Impact of recent increase in incidence on future diabetes burden: U.S., 2005-2050. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(9):2114–2116. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koro CE, Bowlin SJ, Bourgeois N, Fedder DO. Glycemic control from 1988 to 2000 among U.S. adults diagnosed with type 2 diabetes: a preliminary report. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(1):17–20. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harris MI, Eastman RC, Cowie CC, Flegal KM, Eberhardt MS. Racial and ethnic differences in glycemic control of adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(3):403–408. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Egede LE, Bonadonna RJ. Diabetes self-management in African Americans: an exploration of the role of fatalism. Diabetes Educ. 2003 Jan-Feb;29(1):105–115. doi: 10.1177/014572170302900115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eaton WW, Armenian H, Gallo J, Pratt L, Ford DE. Depression and risk for onset of type II diabetes. A prospective population-based study. Diabetes Care. 1996 Oct;19(10):1097–1102. doi: 10.2337/diacare.19.10.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eaton WW. Epidemiologic evidence on the comorbidity of depression and diabetes. J Psychosom Res. 2002 Oct;53(4):903–906. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00302-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Groot M, Anderson R, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. Association of depression and diabetes complications: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2001 Jul-Aug;63(4):619–630. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200107000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lustman PJ, Clouse RE. Depression in diabetic patients: the relationship between mood and glycemic control. J Diabetes Complications. 2005 Mar-Apr;19(2):113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chin MH, Zhang JX, Merrell K. Diabetes in the African-American Medicare population. Morbidity, quality of care, and resource utilization. Diabetes Care. 1998 Jul;21(7):1090–1095. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.7.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ofili E. Ethnic disparities in cardiovascular health. Ethn Dis. 2001 Fall;11(4):838–840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blazer DG, Hybels CF, Simonsick CF, Hanlon JT. Marked differences in antidepressant use by race in an elderly community sample: 1986-1996. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:1089–1094. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.7.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown C, Schulberg HC, Sacco D, Perel JM, Houck PR. Effectiveness of treatments for major depression in primary medical care practice: A post hoc analysis of outcomes for African-American and white patients. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1999;53:185–192. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00120-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirk JK, Bell RA, Bertoni AG, et al. Ethnic disparities: control of glycemia, blood pressure, and LDL cholesterol among US adults with type 2 diabetes. Ann Pharmacother. 2005 Sep;39(9):1489–1501. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirk JK, D’Agostino RB, Jr., Bell RA, et al. Disparities in HbA1c levels between African-American and non-Hispanic white adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2006 Sep;29(9):2130–2136. doi: 10.2337/dc05-1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wisdom K, Fryzek JP, Havstad SL, Anderson RM, Dreiling MC, Tilley BC. Comparison of laboratory test frequency and test results between African-Americans and Caucasians with diabetes: opportunity for improvement. Findings from a large urban health maintenance organization. Diabetes Care. 1997 Jun;20(6):971–977. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.6.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris MI. Racial and ethnic differences in health care access and health outcomes for adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2001 Mar;24(3):454–459. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.3.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang P, Berglund P, Kessler R. Recent care of common mental disorders in the United States. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2000;15:284–292. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.9908044.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Snowden LR, Pingitore D. Frequency and scope of mental health service delivery to African Americans in primary care. Mental Health Service Research. 2002;4(3):123–130. doi: 10.1023/a:1019709728333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ayalon L, Arean PA, Linkins K, Lynch M, Estes CL. Integration of mental health services into primary care overcomes ethnic disparities in access to mental health services between black and white elderly. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2007;15(10):906–912. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318135113e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bogner HR, Dahlberg B, de Vries HF, Cahill EC, Barg FK. Older patients’ views on the relationship between depression and heart disease. Family Medicine. 2008;40(9):652–657. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gilliland SS, Carter JS, Perez GE, TwoFeathers J, Kenui CK, Mau MK. Recommendations for development and adaptation of culturally competent community health interventions in minority populations with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Spectrum. 1998;11:166–174. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murphy FG, Satterfield D, Anderson RM, Lyons AE. Diabetes educators as cultural translators. Diabetes Educ. 1993 Mar-Apr;19(2):113–116. 118. doi: 10.1177/014572179301900204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumanyika S. Diabetes, diet, and weight control among black Americans. Diabetes Care and Education. 1991;12:7–10. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fisher TL, Burnet DL, Huang ES, Chin MH, Cagney KA. Cultural leverage: interventions using culture to narrow racial disparities in health care. Med Care Res Rev. 2007 Oct;64(5 Suppl):243S–282S. doi: 10.1177/1077558707305414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steinhardt MA, Mamerow MM, Brown SA, Jolly CA. A resilience intervention in African American adults with type 2 diabetes: a pilot study of efficacy. Diabetes Educ. 2009 Mar-Apr;35(2):274–284. doi: 10.1177/0145721708329698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bogner HR, Morales KH, Post EP, Bruce ML. Depression, diabetes, and death: A randomized controlled trial of a depression treatment program for older adults based in primary care (PROSPECT) Diabetes Care. 2007;30(12):3005–3010. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cramer JA, Rosenheck R. Compliance with medication regimens for mental and physical disorders. Psychiatric Services. 1998;49:196–201. doi: 10.1176/ps.49.2.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bogner HR, Lin JY, Morales KH. Patterns of early adherence to the antidepressant citalopram among older primary care patients: the prospect study. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2006;36(1):103–119. doi: 10.2190/DJH3-Y4R0-R3KG-JYCC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization Report of a World Health Organization and International Diabetes Federation meeting: screening for type 2 diabetes; Geneva: World Health Organization. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Center for Disease Control and Prevention Prevalence of diabetes and impaired fasting glucose in adults- United States, 1999- 2000. MMWR. 2003;52:833–837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cooper LA, Gonzales JJ, Gallo JJ, et al. The acceptability of treatment for depression among African-American, Hispanic, and white primary care patients. Med Care. 2003 Apr;41(4):479–489. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000053228.58042.E4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Angst J. Clinical course of affective disorders. In: Helgason T, Daly R, editors. Depression Illness: Prediction of course and outcome. Springer-verlag; Berlin, Germany: 1988. pp. 1–47. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kodner D. American Society on Aging Summer Series on Aging. 1999. Integrated long term care systems in the new millenium- fact or fiction? [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davies B. The reform of community and long term care of eldelry persons: an international perspective. In: Scharf T, Wenger C, editors. International perspective on community care for older people. Ashgate; Brookfield, VT: 1995. pp. 21–38. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leutz W. Five laws for integrating medical and social services: lessons from the United States and the United Kingdom. The Millbank Quarterly. 1999;77(1):77–110. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davies K. Addressing the needs of an ethnic minority diabetic population. BJN. 2006;15(9):516–519. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2006.15.9.21093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mundt JC, Clarke GN, Burroughs D, Brenneman DO, Griest JH. Effectiveness of antidepressant pharmacotherapy: the impact of medication compliance and patient education. Depress Anxiety. 2001;13(1):1–10. doi: 10.1002/1520-6394(2001)13:1<1::aid-da1>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beck RS, Daughtridge R, Sloane PD. Physician-patient communication in the primary care office: a systematic review. Journal of the American Board of Family Practice. 2002;15(1):25–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ferguson WJ, Candib LM. Culture, language, and the doctor-patient relationship. Family Medicine. 2002;34(5):353–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schim SM, Doorenbos A, Benkert R, Miller J. Culturally congruent care: putting the puzzle together. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2007;18(2):103–110. doi: 10.1177/1043659606298613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kalb KB, Cherry NM, Kauzloric J, et al. A competency-based approach to public health nursing performance appraisal. Public Health Nursing. 2006;23(2):115–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2006.230204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rubin H, Rubin I. Qualitative interviewing: The art of hearing data. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lillie-Blanton M, Hoffman SC. Conducting an assessment of health needs and resources in a racial/ethnic minority community. Health Services Research. 1995;30(1 Pt 2):225–236. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;20:22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-Mental State”: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Crum RM, Anthony JC, Bassett SS, Folstein MF. Population-based norms for the Mini-Mental State Examination by age and educational level. JAMA. 1993;269:2386–2391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stewart AL, Hays RD, Ware JE. The MOS Short-form General Health Survey: Reliability and validity in a patient population. Medical Care. 1988;26:724–735. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198807000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stadnyk K, Calder J, Rockwood K. Testing the measurement properties of the Short Form-36 health survey in a frail elderly population. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1998;51:827–835. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00061-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.ADA American Diabetes Association: Clinical Practice Recommendations. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(S1):S1–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huisman TH, Henson JB, Wilson JB. A new high-performance liquid chromatographic procedure to quantitate hemoglobin A1c and other minor hemoglobins in blood of normal, diabetic, and alcoholic individuals. Journal of Laboratory & Clinical Medicine. 1983;102(2):163–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Comstock GW, Helsing KJ. Symptoms of depression in two communities. Psychological Medicine. 1976;6:551–563. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700018171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eaton WW, Kessler LG. Rates of symptoms of depression in a national sample. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1981;114:528–538. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gatz M, Johansson B, Pedersen N, Berg S, Reynolds C. A cross-national self-report measure of depressive symptomatology. International Psychogeriatrics. 1993;5:147–156. doi: 10.1017/s1041610293001486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Foley K, Reed P, Mutran E, DeVellis R. Measurement adequacy of the CES-D among a sample of older African-Americans. Psychiatry Research. 2002;109:61–69. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(01)00360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.George CF, Peveler RC, Heiliger S, Thompson C. Compliance with tricyclic antidepressants: the value of four different methods of assessment. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2000;50:166–171. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2000.00244.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Farmer KC. Methods for measuring and monitoring medication regimen adherence in clinical trials and clinical practice. Clinical Therapeutics. 1999;21(6):1074–1090. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2918(99)80026-5. discussion 1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Peveler R, George C, Kinmonth AL, Campbell M, Thompson C. Effect of antidepressant drug counselling and information leaflets on adherence to drug treatment in primary care: randomised controlled trial. Bmj. 1999 Sep 4;319(7210):612–615. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7210.612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Keyserling TC, Samuel-Hodge CD, Ammerman AS, et al. A randomized trial of an intervention to improve self-care behaviors of African-American women with type 2 diabetes: impact on physical activity. Diabetes Care. 2002 Sep;25(9):1576–1583. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.9.1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Utz SW, Williams IC, Jones R, et al. Culturally tailored intervention for rural African Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2008 Sep-Oct;34(5):854–865. doi: 10.1177/0145721708323642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hill-Briggs F, Renosky R, Lazo M, et al. Development and pilot evaluation of literacy-adapted diabetes and CVD education in urban, diabetic African Americans. J Gen Intern Med. 2008 Sep;23(9):1491–1494. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0679-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Auslander W, Haire-Joshu D, Houston C, Rhee CW, Williams JH. A controlled evaluation of staging dietary patterns to reduce the risk of diabetes in African-American women. Diabetes Care. 2002 May;25(5):809–814. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.5.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Agurs-Collins TD, Kumanyika SK, Ten Have TR, Adams-Campbell LL. A randomized controlled trial of weight reduction and exercise for diabetes management in older African-American subjects. Diabetes Care. 1997 Oct;20(10):1503–1511. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.10.1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Phillips LS, Ziemer DC, Doyle JP, et al. An endocrinologist-supported intervention aimed at providers improves diabetes management in a primary care site: improving primary care of African Americans with diabetes (IPCAAD) 7. Diabetes Care. 2005 Oct;28(10):2352–2360. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.10.2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2002 Dec 11;288(22):2836–2845. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Leeman J. Interventions to improve diabetes self-management: utility and relevance for practice. Diabetes Educ. 2006 Jul-Aug;32(4):571–583. doi: 10.1177/0145721706290833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gallo JJ, Zubritsky C, Maxwell J, et al. Primary care clinicians evaluate integrated and referral models of behavioral health care for older adults: results from a multisite effectiveness trial (PRISM-e) Ann Fam Med. 2004 Jul-Aug;2(4):305–309. doi: 10.1370/afm.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bartels SJ, Coakley EH, Zubritsky C, et al. Improving access to geriatric mental health services: a randomized trial comparing treatment engagement with integrated versus enhanced referral care for depression, anxiety, and at-risk alcohol use. Am J Psychiatry. 2004 Aug;161(8):1455–1462. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]