Abstract

Epithelial ovarian cancer, which comprises several histologic types and grades, is the most lethal cancer among women in the United States. In this review, we summarize recent progress in understanding the pathology and biology of this disease and in development of models for preclinical research. Our new understanding of this disease suggests new targets for therapeutic intervention and novel markers for early detection of disease.

Keywords: Ovarian cancer, Pathology, Senescence, Disease Models, Review

2. INTRODUCTION

Epithelial ovarian cancer is the most lethal form of cancer among women in the United States. It accounts for about 3% of all cancers among women and is second in frequency to uterine cancer. An estimated 21,650 new cases and 15,520 deaths were expected in 2008 in the United States (1). Its early detection is hampered by the lack of appropriate tumor markers and of clinically significant symptoms until the disease reaches an advanced stage. For the same reasons, ovarian cancer has the highest fatality-to-case ratio of all gynecological malignancies (2). Among the major clinical problems associated with ovarian cancer, those that remain unresolved include malignant progression, rapid emergence of drug resistance, and associated cross-resistance. The introduction of paclitaxel in the 1990s improved the rates of initial complete response (51% vs. 31%), progression-free survival (18 months vs. 13 months), and overall survival (38 months vs. 24 months) (3). However, the clinical behavior of this malignancy varies widely, from an excellent prognosis and high likelihood of cure to rapid progression and poor prognosis, most probably reflecting variation in the tumors’ biological properties. The survival rate of patients with early stage disease approaches 90%, but most cases are diagnosed late, when the symptoms—such as abdominal distension caused by ascites or large tumor masses—become apparent. Even with extensive surgical debulking and chemotherapy, the prognosis of late-stage ovarian cancer is dismal (1).

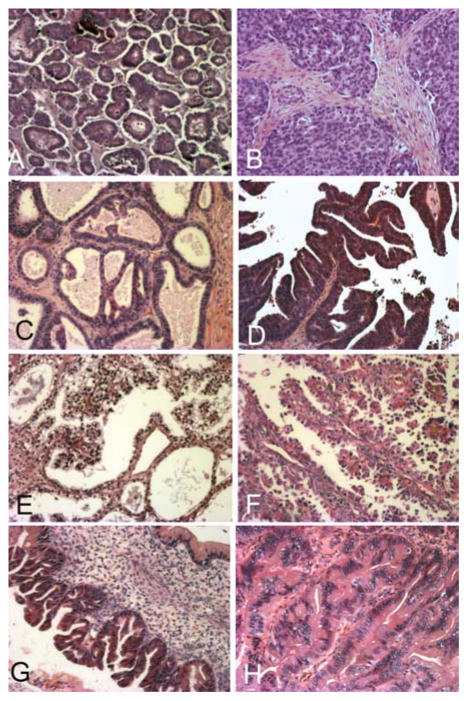

Over 90% of ovarian neoplasms arise from the epithelial surface of the ovary, the rest from germ cells or stromal cells. The epithelial neoplasms are classified as serous (30–70%), endometrioid (10–20%), mucinous (5–20%), clear cell (3–10%), and undifferentiated (1%), and the 5-year survival rates for these subtypes are 20–35%, 40–63%, 40–69%, 35–50%, and 11–29%, respectively (4–6). The histopathology of four most common types of epithelial ovarian cancer is shown in Figure 1. The subtypes differ with regard to risk factors, biological behavior, and treatment response. The following sections discuss these parameters according to each histologic subtype.

Figure 1.

Pictures of the four most common histologic types of ovarian cancer, stained with hematoxylin and eosin. A, Ovarian serous carcinoma showing papillae formation. B, Ovarian serous carcinoma with predominant solid growth pattern. C, Ovarian endometrioid tumor of low malignant potential showing glands similar to the complex hyperplasia of the uterine endometrium. D, High-power view of ovarian endometrioid carcinoma that is morphologically similar to endometrial carcinoma of the uterus. E, Ovarian clear carcinoma showing cellular clearing and cystic growth pattern. F, High-power view of ovarian clear cell carcinoma with hobnail growth pattern. G, Ovarian mucinous tumor of low malignant potential. H, Well-differentiated ovarian mucinous carcinoma.

3. OVARIAN SEROUS CARCINOMA

The serous histotype is the most common type of ovarian carcinoma. It is classified as low grade or high grade on the basis of the extent of nuclear atypia and mitosis (7). Morphologically, low-grade serous carcinoma has minimal nuclear atypia, and mitoses are rare (≤ 12 per 10 high-power fields); high-grade serous carcinoma, on the other hand, is characterized by marked nuclear atypia and more mitoses (> 12 per 10 high-power fields) (7). Low-grade and high-grade carcinomas are different at the genomic and molecular levels. For instance, low-grade serous carcinoma shows fewer molecular abnormalities by both cytogenetic analysis (8–9) and single nucleotide polymorphism analysis (9–10) than high-grade carcinoma. Comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) studies have demonstrated that high-grade serous carcinoma has a significantly higher frequency of copy number abnormalities than low-grade tumors (11–13). Furthermore, high-grade carcinoma showed underrepresentation of 11p and 13q and overrepresentation of 8q and 7p, while low-grade carcinomas showed 12p underrepresentation and 18p overrepresentation more frequently (14).

High-grade serous carcinoma commonly involves p53 mutations, but such mutations are rare in low-grade carcinoma (15). Accumulating data suggest that loss of BRCA1/2 function may predispose to the development of both sporadic and hereditary high-grade serous carcinomas (16). However, the exact mechanism by which BRCA1/2 deficiency triggers tumorigenesis is still not clear. It has been demonstrated that cells with defective BRCA1 are hypersensitive to DNA-damaging agents, are slower to repair double-stranded DNA breaks, and show impairment in transcription-coupled repair (17–18). BRCA1 has been shown to cooperatively bind to p53 and stimulate transcription of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21WAF/Cip1 (19). We recently demonstrated that BTAK, a mitotic phase regulatory protein, is overexpressed in ovaries of women with a BRCA mutation or history of ovarian or breast cancer (20). Furthermore, BTAK overexpression was strongly associated with p53 overexpression, suggesting that p53 may be a physiological substrate of BTAK (20), although the underlying mechanisms of how the interaction of BRCA, p53, and BTAK regulates the initiation of ovarian tumorigenesis are not clear. Other genetic alterations detected in high-grade ovarian cancer include epidermal growth factor receptor (12–82%), Her2/neu (5–66%) (21), AKT2 (36%) (22), phosphoinositide-3 kinase (PI-3K) (22), and c-myc (70%) (23).

Low-grade serous carcinoma is characterized by mutations in the KRAS or BRAF pathway, as mutations in KRAS or its downstream mediator BRAF have been detected in 68% of low-grade and 61% of low-malignant-potential (LMP) serous carcinomas (24–25). RAS encodes the highly homologous and evolutionarily conserved 21,000-kD GTP-binding protein that is often activated in low-grade ovarian serous carcinoma, mucinous ovarian cancer, and endometrioid ovarian cancer. Ras exerts its effects through three downstream effector pathways, namely PI-3K, RAF, and RAL-GEFs. Much of the existing knowledge of these pathways was based on studies of murine cells, which showed that Raf is an effector used by Ras to induce murine cell transformation (26). Recent studies suggest, however, that human cells require more genetic changes in neoplastic transformation than do their murine counterparts. Several types of human primary cells, fibroblasts, embryonic kidney cells, and breast epithelial cells have been successfully transformed by using a set of genetically defined elements (27–29), suggesting that different cell types may require the combination of distinct genetic elements to achieve full transformation.

The Ras pathway may also be activated by the elimination of regulatory proteins such as Dab2 (30). Dab2 could sequester Grb2 from binding to SOS, and the dissociation of the Grb2/SOS complex may reduce Ras activation, which is thought to be a feedback mechanism for Ras downregulation (31). Dab2 has been found to be widely expressed in normal human tissues, particularly in ovarian surface epithelial cells (31). In contrast, Dab2 mRNA and protein expression have been found to be absent or suppressed in most ovarian cancers. Hence, the loss of Dab2 expression may be one of the general changes associated with cell transformation (31). Alternatively, loss of Dab2 may contribute to tumor cell growth, as Dab2 transfection suppressed the expression in morphologically normal epithelium adjacent to ovarian cancer suggests that Dab2 functions as a tumor suppressor and that its expression is an early event in ovarian cancer progression (31).

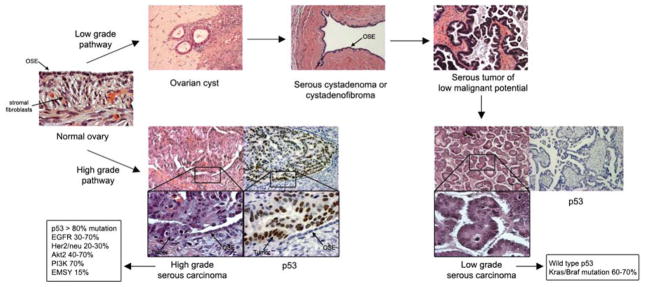

The clinical presentation, morphological features, and molecular data indicate that low-grade and high-grade serous carcinomas arise via different genetic pathways (10,32–36). Singer et al. designated them as type I tumors and type II tumors (37). Type I tumors are low-grade neoplasms that develop in a stepwise fashion from “adenoma–borderline tumor–carcinoma” progression. Type II tumors, however, develop de novo from the surface epithelium and grow rapidly without morphologically recognizable precursor lesions. Mutational analysis of low-grade serous carcinoma showed high frequency of KRAS and BRAF mutations, suggesting that this group of tumors develops through a dysregulated RAS–RAF signaling pathway. High-grade serous carcinoma has a high frequency of mutations in the p53 and BRCA1/2 genes, and thus these tumors most probably arise via TP53 mutations and BRCA1 or BRCA2 dysfunction (36–38). Schematic models for the development of low- and high-grade serous carcinomas are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Dualistic models of serous ovarian cancer development. Development of low-grade serous carcinoma proceeds through morphologically recognizable intermediates, from inclusion cystadenoma or cystadenofibroma to serous tumor of low malignant potential and low-grade serous carcinoma, which is characterized by a high frequency of KRAS/BRAF mutations; the high-grade serous tumor develops de novo, with no recognizable intermediates, and is characterized by a high frequency of p53 mutations and an absence of KRAS/BRAF mutations. OSE: ovarian surface epithelial cells.

4. OVARIAN ENDOMETRIOID CARCINOMA

Ovarian endometrioid carcinoma comprises 10–20% of all epithelial ovarian cancer cases. These tumors are most common in women aged 50–59 years (mean, 56 years). Approximately 15–20% of these women also have endometriosis, which may be outside of the ovary, in the ipsilateral or contralateral ovary, or within the tumor itself. Approximately 14% of women with this cancer have synchronic endometrial carcinoma of the uterus.

Endometrioid tumors have a smooth outer surface. An examination of the cut section usually reveals solid and cystic areas; the cysts contain friable soft masses and bloody fluid. Less commonly, the tumor is solid, with extensive hemorrhage and necrosis. Endometrioid carcinoma has a 5-year survival rate of 40–63%, and the relatively good prognosis is due mostly to the high percentage of patients presenting with early stage disease. However, when patients with endometrioid tumor of the ovary are matched with those with a serous tumor by age and tumor grade, stage, and level of cytoreduction, no significant difference is found in the 5-year survival rate or survival duration (39).

Relatively little is known about the molecular events that lead to development of ovarian endometrioid carcinoma, and no molecular markers have been identified as prognostic indicators. Mutation of the β-catenin gene is one of the most common molecular alterations in endometrioid carcinoma (40) and thus may be a useful molecular marker. β-catenin has been implicated in two important biologic processes: cell-cell adhesion and signal transduction (41–42). At the junctions of epithelial cells, association of β-catenin with the cytoplasmic domain of cadherins plays an important role in Ca2+-dependent cell adhesion. In the nucleus, β-catenin participates in signal transduction, binding to the DNA to activate transcription. Deregulation of the cadherin/catenin complex has been implicated in the development, progression, differentiation, invasion, and metastasis of several malignancies (41–42). Deregulation of β-catenin may be caused by an oncogenic mutation in the β-catenin gene (CTNNB1), mutations in the APC gene, or alterations of the Wnt signal transduction pathway.

Endometrioid carcinoma arising in the uterine cavity and that arising in the ovaries are morphologically similar but differ at the molecular level. For instance, frequency of β-catenin mutation is higher in synchronous tumors than in single ovarian carcinomas (40). Moreover, ovarian endometrioid cancers exhibit microsatellite instability and PTEN alterations less frequently than their uterine counterparts (43). PTEN mutations are found more frequently in endometrioid carcinomas (approximately 43%) than other histologic types, indicating that they may play a role in the development of this subtype (44).

5. OVARIAN MUCINOUS CARCINOMA

Primary mucinous tumors are classified as benign, borderline, or malignant, depending on their histopathologic features. Mucinous tumors may be endocervical-like or intestinal-like, and mixtures of both cell types do occur. Intestinal-like epithelium is most easily recognized when it contains goblet cells; these may be seen in benign tumors but are more prominent in borderline and malignant tumors. Other types of intestinal cell differentiation may be found in ovarian mucinous tumors, however, including features typical of gastric superficial/foveolar and pyloric cells, enterochromaffin cells, argyrophil cells, and Paneth cells (45–46).

Unlike serous tumors, which are generally homogeneous in their cellular composition and degree of differentiation, mucinous tumors are often heterogeneous, particularly the intestinal type. Mixtures of benign, borderline, and malignant elements (including noninvasive and invasive carcinomas) are often found within a single neoplasm. Tumor heterogeneity in these intestinal-type mucinous tumors suggests that malignant transformation is sequential, progressing from a cystadenoma or borderline tumor to noninvasive, microinvasive, and invasive carcinoma. Analyses of KRAS mutations lend molecular genetic support to this theory (47–48). KRAS mutations are common in mucinous ovarian tumors. Interestingly, some microdissected mucinous tumors were found to have the same KRAS mutation in histologically benign, borderline, and malignant areas of the same tumor (47–48). Thus, KRAS mutation may be an early event in ovarian mucinous carcinogenesis.

Mucinous carcinomas are classified according their extent of invasion (49). Mucinous tumors of intestinal type that contain glands with the architectural and cytologic features of adenocarcinoma but lack obvious stromal invasion are classified as noninvasive carcinomas. Microinvasion has been found in approximately 9% of intestinal-type borderline tumors (50–51). In general, individual infiltrative foci with a maximum dimension of < 3.0 mm or a maximum area of < 10 mm2 (provided neither of two linear dimensions exceeds 3.0 mm) are considered microinvasive (50,52–53). Other investigators have used a cutoff of 2.0 mm (30) or 5.0 mm (21). Individual microinvasive foci commonly are < 1.0 or 2.0 mm (51,53). The number of invasive foci in a tumor is variable. More than half of these tumors may have more than five foci (53). The histologic criteria for microinvasion include the presence of irregular jagged glands and small strips or nests of tumor cells accompanied by reactive fibroblastic stroma. Chronic inflammatory infiltrate may be also present. Recently, an expansile type of invasion was defined (50). This is characterized by an architecturally complex, arrangement of glands, cysts, or papillae lined by malignant epithelium with minimal or no intervening normal ovarian stroma. However, the extent, depth, and number of microinvasive foci, and their clinical significance, still need to be scientifically validated.

Fully invasive mucinous carcinoma is uncommon, accounting for fewer than 10% of all primary ovarian carcinomas (50,54). The prognosis of invasive mucinous carcinomas of intestinal type depends on the FIGO stage and the histologic pattern of stromal invasion (50,52–53,55) but is favorable compared with that of serous carcinomas; this is because 80% of invasive mucinous carcinomas are stage I at diagnosis. Carcinomas with an infiltrative pattern of invasion are more aggressive than those with an expansile pattern. In two recent series, all 27 cases with expansile invasion were stage I, and none of the 21 for which follow-up data were available had metastasized (50,52,55).

The molecular mechanisms that lead to the progression of benign mucinous tumors are still largely unknown. In a recent study, Wamunyokoli et al. profiled gene expression in 25 microdissected mucinous tumors (6 cystadenomas, 10 LMP tumors, and 9 adenocarcinomas) and described the pathway analysis used to identify gene interactions that may influence ovarian mucinous tumorigenesis and genes that may mediate the phenotypes typically associated with these tumors (56). These latter include genes that regulate multidrug resistance (ABCC3 and ABCC6), signal transduction (SPRY1 and CAV-1), cytoskeleton rearrangement/signal transduction (RAC1, CDC42, RALA, IQGAP2, cortactin), cell cycle regulation and proliferation (CCND1, ERBB3, transforming growth factor (TGF)-alpha, and transformation (c-JUN, K-ras2, ECT2, YES1).

6. OVARIAN CLEAR CELL CARCINOMA

Ovarian clear cell carcinoma (OCCA) accounts for fewer than 5% of all ovarian malignancies and 3.0–12.1% of all ovarian epithelial neoplasms (57). Unlike serous carcinoma, OCCA often presents as a large pelvic mass in early stages and thus is diagnosed early. Advanced-stage disease has a poor prognosis and is resistant to cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Little is known about the development and progression of OCCA. Studies have shown that 5–10% of cases are associated with endometriotic lesions; however, little molecular evidence exists to support an ectopic origin. While p53 mutations are common in tumorigenesis and have been found in various epithelial subtypes, particularly serous ovarian carcinoma, they are conspicuously absent in OCCA (58–59), implying that other anti-apoptotic mechanisms are involved.

The target of methylation-induced silencing 1/apoptosis-associated speck-like protein (TMS-1/ASC) is a member of the caspase recruitment domain family of proapoptotic mediators. A high frequency of aberrant methylation that results in transcriptional silencing of TMS-1/ASC has been observed in OCCA tumors, indicating a mechanism for apoptotic escape in tumor development; this may have implications for drug resistance in OCCA as well (60). Mutations in the PTEN gene are common in endometrioid and clear cell ovarian cancers but not in serous or mucinous ovarian cancers. Loss of CD44 splice control has also been observed in OCCA (61–62). CD44 is a membrane glycoprotein and is the major cell-surface receptor of hyaluronate, a glycosaminoglycan that is present on the surface of human peritoneal cells. The presence of the CD44 isoform CD44-10v was associated with recurrence or death in 71% of women with OCCA, whereas only 18% of women without the isoform experienced recurrence or died of disease (63). The CD44-10v isoform was also absent in the contralateral, unaffected ovaries, suggesting that aberrant alternative mRNA splicing of CD44 is involved in the development and progression of OCCA.

Several investigators have studied OCCA to determine whether it has a distinct genetic fingerprint. Using conventional CGH, Suehiro et al. found increased copy numbers of 8q11–q13, 8q21–q22, 8q23, 8q24–qter, 17q25–qter, 20q13–qter, and 21q22-qter, and reduced copy numbers of 19p. A molecular signature that distinguishes OCCA from other histologic types was reported by Schwartz et al., who identified 73 genes that were expressed at 2–29 times higher levels in OCCA than in other histologic types (64). However, this study included only eight OCCA specimens and revealed that OCCA had a two times higher level of Her-2 expression than other types. More recently, a comparison of the gene expression profiles of serous, endometrioid, and clear cell types of ovarian cancer with that of normal ovarian surface epithelium revealed 43 genes that were common to all types (62), suggesting that the process of malignant transformation in serous, endometrioid, and clear cell types of ovarian cancer involves a common pathway. Furthermore, the profiles of OCCA were similar to those of renal and endometrial clear cell carcinomas, implying that certain molecular events are common to clear cell tumors, regardless of the organ of origin (62), and that crossover molecular target exist with which to treat these tumors.

Microsatellite instability is caused by defects in DNA mismatch–repair genes. In experimental systems, mismatch repair–deficient cells are highly tolerant to the methylating chemotherapeutic drugs streptozocin and temozolomide, and, to a lesser extent, cisplatin and doxorubicin (65). Thus, these drugs are expected to be less effective against mismatch repair–deficient tumors in humans. We observed high-level microsatellite instability involvement in the development of a subset of OCCAs and a strong association between alterations in hMLH1 and hMSH2 expression and microsatellite instability in these tumors (66). Significantly elevated mRNA levels of ERCC1 (excision-repair, complementing defective, in Chinese hamster-1) and XPB, two key genes involved in the nucleotide excision repair pathway and in in vitro resistance to platinum-based chemotherapy (67), have also been observed in OCCA but not in other epithelial ovarian carcinoma subtypes (68). Therefore, altering the expression of DNA-repair genes may provide a possible mechanism of drug resistance against DNA-damaging agents in OCCA. A unique 93-gene expression profile, the chemotherapy response profile, was recently described; this profile was predictive of pathologic complete response to first-line platinum- or taxane-based chemotherapy in 60 patients with epithelial ovarian carcinoma, 92% of whom had the serous histologic type (69). The apoptotic activator BAX was associated with chemoresistance: its expression was reduced in patients with chemoresistant tumors. High levels of BAX protein have previously been associated with paclitaxel sensitivity and improved survival in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer (70). As described earlier, among the immunohistochemical characteristics of OCCA is the notable overexpression of BAX in stage I and II OCCA tumors (58). Furthermore, the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2, which inhibits BAX-mediated apoptosis, is expressed at higher levels in metastatic OCCA lesions than in primary OCCA lesions (71). A p53-mediated pathway has been implicated in the induction of cell death after DNA damage by platinum-based chemotherapeutic agents, which results in a decrease in the relative ratio of Bcl-2/Bax, thus favoring apoptosis (72). Hence, the presence of a lower relative ratio of Bcl-2/BAX in early stage OCCA tumors and a higher relative ratio of Bcl-2/BAX in metastatic OCCA lesions may account for the dichotomy in outcome observed between patients with early stage OCCA, who have a good prognosis, and those with late-stage, platinum-resistant OCCA, who have a poorer prognosis than their counterparts with serous carcinomas.

7. HOX GENES IN OVARIAN CANCER HISTOGENESIS

Ovarian carcinoma comprises at least four distinct histotypes as already described, each with its own clinical behavior and characteristic molecular fingerprint. The type and degree of differentiation are key determinants of clinical behavior and prognosis. Recent studies have demonstrated that the inappropriate inactivation of a molecular program that controls patterning of the reproductive tract could explain the morphologic heterogeneity of epithelial ovarian cancers and their assumption of müllerian features (73). This program is regulated by a family of homeobox genes (HOX). Originally described in Drosophila, these genes regulate normal axial and spatial development. In mammals, HOX genes, tandemly arranged, control lower abdominal development—Hoxa9, Hoxa10, and Hoxa11, which are related to Abdominal-B (Abd-B), control differentiation of the müllerian ducts into the fallopian tubes, uterus, and cervix (73). Dysregulation of different HOX genes leads to development of serous, endometrioid, and mucinous carcinomas (73).

8. EPITHELIAL-STROMAL INTERACTIONS IN CANCER

Most studies on oncogene activation and loss of tumor suppression have focused on their role in epithelial cells; few have focused on how transformed epithelial cells interact with a major component of the tumor microenvironment—stromal fibroblasts. Several studies have revealed that the stromal microenvironment can prompt transformation of initiated (immortalized) epithelial cells but not normal fibroblasts. Cuhna and colleagues found that an initiated but nontumorigenic prostate epithelial cell line was transformed to a tumorigenic state after being exposed to fibroblasts derived from cancer but not to normal fibroblasts (74). Campisi and colleagues demonstrated that senescent fibroblasts, which behave like cancer-derived fibroblasts, can induce transformation of initiated epithelial cells but not normal epithelial cells (75–76). These cancer-derived fibroblasts are presumably in an active state and could constitute a step in the stepwise oncogenesis model (i.e., progression from benign epithelial cells to full malignancy). In support of this view are findings from a cDNA expression profile analysis of 16,500 genes in which peritoneal samples from patients with ovarian cancer had higher levels of several inflammatory cytokines than samples from healthy women and women with benign ovarian disease. Natural ovarian cancer is characterized by an abundant cytokine network that includes proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors (77–80). None of these studies, however, have explained how these fibroblasts or peritoneal cells become activated and stimulate transformation, partly because of the lack of a model system with which to address these questions.

9. SENESCENT FIBROBLASTS IN OVARIAN CANCER PROMOTION

Cellular senescence is thought to contribute to both aging and cancer development, probably through secreted growth factors, cytokines, extracellular matrix, and degradative enzymes, although the specific mechanisms are poorly understood (81–83). Because cellular senescence accumulates with age, it may contribute to age-related declines in tissue function. Cellular senescence may act to suppress tumor formation at a young age but promote it at an older age, perhaps because abrogation of the senescence program by genetic mutations in epithelial cells provides a favorable tumor microenvironment. In addition to natural aging, environmental carcinogens such as radiation can induce a senescence-like phenotype and promote epithelial tumor growth (84). Thus, senescence is a double-edged sword that can both suppress tumors (in the development of cancer cells) and promote them (if senescence occurs in cell types near cancer cells); this is the “good citizen/bad neighbor” concept proposed by Judith Campisi (83,85). In 2001, Campisi and colleagues found that senescent fibroblasts promoted the transformation of epithelial cells in which the senescence program was disrupted (75,76). Other investigators have shown that senescent fibroblasts can increase invasion by upregulating growth factors and changes in survival pathways (84,86).

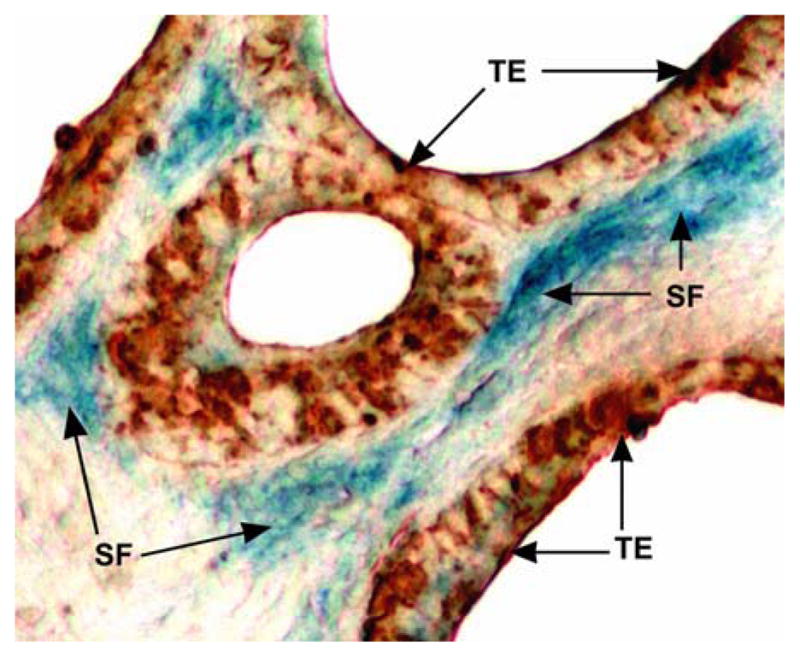

Senescent fibroblasts were shown to promote transformation and tumor growth in a xenograft mouse model (75); however, whether these fibroblasts exist in vivo remains uncertain. Another unsettled issue in the field is the nature of the molecular signals that trigger senescence and their source (presumably tumor cells). In a previous study, we used three senescence markers (SA-β-gal, p16, and H1B-β and found that fibroblasts near epithelial ovarian cancer cells are senescent (87). We also found that Ras sends a signal, Gro-1, to neighboring cells to induce fibroblast senescence, which creates a “tumor-prone” microenvironment that promotes tumorigenesis. These findings bridge the “missing link” in the field of senescence: they show that the “bad neighbor” exists in vivo and that Gro-1, a downstream target gene of Ras, can reprogram normal fibroblasts to become senescent, thereby promoting cancer cell growth. Thus, senescent fibroblasts may be a key component of cancer stroma and work with other components, including endothelial cells and macrophages, to synergistically promote tumorigenesis in vivo. A representative picture of senescent stromal fibroblasts in ovarian cancer is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The fibroblasts near ovarian cancer are senescent. The epithelial cells are highlighted by positive staining for cytokeratin, while senescent fibroblasts are stained positively by acidic β-galactosidase.

10. INFLAMMATION AND OVARIAN CARCINOGENESIS

Ovarian cancer develops in a unique microenvironment, the peritoneum. For many years, two hypotheses on the etiology of ovarian cancer were dominant—the ovulation hypothesis, which linked ovarian cancer with the number of ovulation events (88), and the pituitary gonadotropin hypothesis, which suggested that postmenopausal elevations in gonadotropin acted in concert with estrogen to stimulate the transformation of human ovarian surface epithelial cells (89). Systematic evaluations of epidemiologic data, however, implicate chronic inflammation (caused by repeated ovulation, endometriosis, or pelvic inflammation) in the development of most forms of ovarian cancer (90–92). As described in our recent review, the peritoneum comprises the basis of the microenvironment in which the initiation, progression, and differentiation of ovarian cancer take place (93). The peritoneum is organized, both structurally and functionally, to protect the integrity of the abdominal organs. The surface epithelium of the peritoneal and serosal membrane is attached to a base membrane that lies atop a stromal layer of variable thickness composed of a collagen-based matrix, blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and nerve fibers. Because the peritoneum is open to the environment through the fallopian tubes, it is constantly susceptible to environmental proinflammatory stimuli such as viral or bacterial infection. Thus, peritoneal inflammation could represent a “tumor-prone” microenvironment that facilitates ovarian cancer initiation and progression.

For decades, researchers have known that strong associations exist between inflammation and cancer development—for example, Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer, hepatitis C and hepatocellular carcinoma, ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease and colon cancer, and chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer (94–95). High circulating levels of inflammatory cytokines have been found in several tumor types (96–98). Biochemical evidence indicates that cytokines with roles in tumor growth and metastasis are abundant in natural ovarian cancer (77–80). Recently, Karin and Ben-Neriah linked activated NF-κB, chronic inflammation, and tumor initiation and progression in mouse models of ulcerative colitis and hepatitis, thus providing the first evidence that NF-κB is the long-sought missing link between inflammation and cancer (99–101). The activation of NF-κB in response to chronic inflammation may be critical for ovarian cancer initiation and progression. Proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α may have a key role in the ovarian cancer microenvironment (102). The role of proinflammatory cytokines in promoting the development of tumor stroma and controlling host and preneoplastic interactions could be mimicked by RAS/NF-κB signaling; in the genetically defined model we developed (see below), Ras activated several cytokines involved in proinflammatory pathways, such as TNF-α, interleukin (IL)-1, IL-8, IL-6, cyclooxygenase 2, Gro-1, and Gro-2. These results strongly suggest that Ras alters the tissue microenvironment by means of cytokines that activate both epithelial and stromal cells in autoparacrine and paracrine manners, as described in models of ulcerative colitis and hepatitis. Cancer-associated fibroblasts could replace Ras in our transformation model (see below), suggesting that they have functions similar to those of Ras. Because NF-κB is central to the activation of proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and tissue modeling factors, our genetically defined model of Ras-mediated transformation in ovarian cancer may allow us to answer questions regarding the role of Ras signaling in ovarian tumorigenesis, the dominant pathway in mucinous and low-grade serous carcinomas of the ovary.

11. MODELS OF OVARIAN CANCER

Despite our knowledge of genetic alternations in ovarian cancer, we do not understand how these genetic changes work together to transform normal ovarian surface epithelial cells into cancerous cells. This is partly because we lack an experimental model system for studying human ovarian cancer. Since 1980, several researchers have used ovarian surface epithelial cells isolated from rats, mice, and rabbits as models for ovarian carcinogenesis (103–105). Rat ovarian surface epithelial lines can be transformed into tumorigenic lines after multiple passages (104,106). The genetic events required for malignant transformation in these spontaneous transformation systems are poorly defined, however, and the specific genetic events required for ovarian cancer to develop remain unknown. To overcome the limitations associated with spontaneously transformed rodent cells, Orsulic et al. developed a mouse model system in which an avian retroviral gene delivery technique is used to introduce several genes into mouse ovarian surface epithelial cells (107). The introduction of any two of the oncogenes—c-myc, K-ras, or Akt—onto a mutated p53 background led to formation of ovarian tumors that were similar to human ovarian cancer. The results of a more recent study showed that approximately half of female transgenic mice expressing the transforming region of SV40 under the control of the müllerian inhibitory substance type II receptor gene promoter developed bilateral ovarian tumors (108). Mutation activation in K-ras and inactivation in PTEN or double mutational inactivation in APC and PTEN leads to development of ovarian endometrioid carcinoma (109–110), whereas concurrent inactivation of p53 and Rb leads to development of serous carcinoma from mouse ovarian surface epithelial cells (111). Ovarian surface epithelial cells from humans are more difficult to transform than cells from rodents. Several researchers have used cultured human ovarian surface epithelial cells to study human ovarian carcinogenesis (112–115). Transfection of such cells with the SV40 early genomic region that expresses T and t antigens or the human papillomavirus-16 E6/E7 region extended the life span of these cells, but the transfected cells eventually entered crisis and died (113,116). After several months, immortal cells occasionally emerged, but they did not form colonies in soft agar or tumors in nude mice (113,116). Rarely, cells transfected with T/t or E6/E7, after many passages in culture, produced colonies in soft agar or formed tumors in nude mice (113,114), presumably as a result of spontaneous mutation.

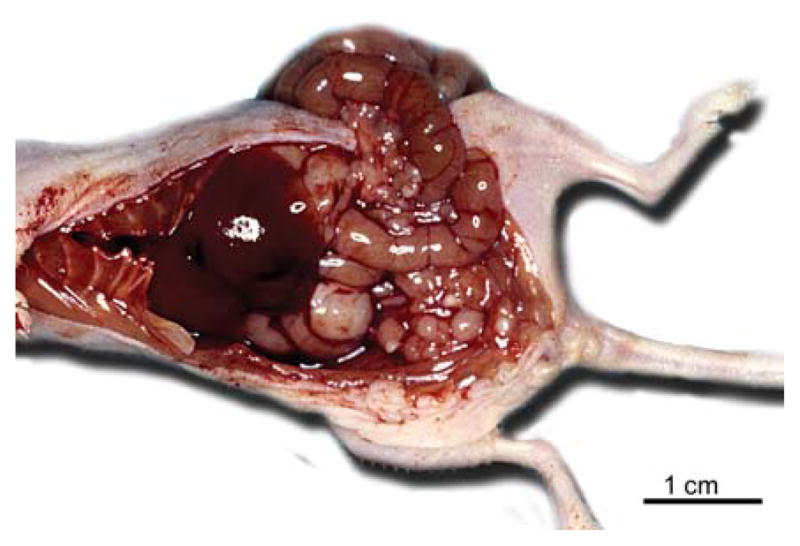

We have established models based on human ovarian surface epithelial cells to understand human ovarian cancer development. We recently created a genetically defined model of human ovarian cancer in which the SV40 early genomic region was used to disrupt the p53 and Rb pathways. The catalytic subunit of telomerase (hTERT) and HRAS or KRAS were introduced into human ovarian surface epithelial cells using the transformation protocol developed by Hahn and Weinberg (117). The successful transformation of these cells was confirmed by their ability to form subcutaneous tumors in nude mice. Moreover, mice given intraperitoneal injections of these transformed cells developed ascites and undifferentiated or malignant mixed müllerian tumors with focal staining for CA125 and mesothelin (markers of human ovarian cancer). These cells provide a novel model system for studying RAS signaling in human ovarian cancer transformation (118). A representative picture of ovarian cancer generated from transformed ovarian surface epithelial cells is shown in Figure 4. Transformation of ovarian epithelial cells by HRAS or KRAS activation also leads to expression of cytokines involved in chronic inflammation and wound healing. Increased concentrations of IL-1β and IL-8 have been detected in human ovarian cancer cell lines and in ascites and serum samples from ovarian cancer patients (119–123), demonstrating that the pathways used in our genetically transformed cell lines are similar to those in naturally derived ovarian cancer. Thus, our cellular model constitutes a valuable model for studying the initiation of ovarian cancer on a well-defined genetic background. Because many of the cytokines activated by RAS in our model are similar to these involved in ovulation, this model provides a valuable experimental tool for studying ovulation’s contribution to ovarian oncogenesis.

Figure 4.

Genetically transformed human ovarian surface epithelial cells grew tumors similar to human ovarian cancer in the peritoneal cavities of nude mice. Arrow heads indicate the tumor nodules.

Despite the large amount of valuable information generated by this model, it is limited by its use of the SV40 T/t antigen, which has multiple downstream effects that may complicate interpretation of the mechanisms involved in RAS-mediated transformation. To overcome this limitation, we generated a second-generation model of immortalized, nontumorigenic cells by using retrovirus-mediated small-interfering RNA against p53 or Rb, in combination with the ectopic hTERT expression (124–125). This new model offers new opportunities to study the mechanisms underlying development of different types and grades of ovarian cancer and to define the number and combinations of genetic changes required for ovarian carcinogenesis.

In summary, significant progress has been made in understanding the pathology, biology, and etiology of ovarian cancer, particularly in last 5 years. Development of ovarian cancer involves not only alteration of genetic elements in the genome of epithelial cells but also reprogramming of the microenvironment such as stroma and inflammation. Understanding the genetics and pathways at the molecular levels in both epithelial cells and stromal fibroblasts allows us to model ovarian cancer using defined genetic elements. RAS-transformed human ovarian surface epithelial cells and mouse models represent invaluable tools in dissecting the mechanisms of initiation and progression of ovarian carcinoma, which will yield new drug targets for therapeutic intervention.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to apologize to the investigators whose outstanding work was not cited here because of space limitations. This work is supported by grants from the American Cancer Society (RSG-04-028-1-CCE) and from the National Cancer Institute (1R01CA131183-01A2) to JL.

Abbreviations

- CGH

comparative genome hybridization

- PI-3K

phosphoinositide-3 kinase

- LMP

low malignant potential

- TGF

transforming growth factor

- OCCA

ovarian clear cell carcinoma

- TMS-1/ASC

target of methylation-induced silencing 1/apoptosis-associated speck-like protein

- IL

interleukin

- hTERT

catalytic subunit of telomerase

References

- 1.Jemal Ahmedin, Siegel Rebecca, Ward Elizabeth, Murray Taylor, Xu Jiaquan, Thun Michael J. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:471–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ozols Robert F. Chemotherapy for ovarian cancer. Semin Oncol. 1999;26:34–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGuire William P, Hoskins William J, Brady Mark F, Kucera Paul R, Partridge Edward E, Look Katherine Y, Clarke-Pearson Daniel L, Davidson Martin. Cyclophosphamide and cisplatin compared with paclitaxel and cisplatin in patients with stage III and stage IV ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199601043340101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Björkholm Elisabet, Pettersson Folke, Einhorn Nina, Krebs I, Nilsson Bjorn, Tjernberg B. Long-term follow-up and prognostic factors in ovarian carcinoma; the radiumhemmet series 1958 to 1973. Acta Radiol Oncol. 1982;21:413–9. doi: 10.3109/02841868209134321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Högberg Thomas, Carstensen John, Simonsen Ernst. Treatment results and prognostic factors in a population-based study of epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Onco. 1993;48:38–49. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1993.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sorbe Bengt, Frankendal Bo, Veress Bela. Importance of histologic grading in the prognosis of epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Obstet Gynecol. 1982;59:576–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malpica Anais, Deavers Micheal T, Lu Karen, Bodurka Diane C, Atkinson Edward N, Gershenson David M, Silva Elvio G. Grading ovarian serous carcinoma using a two-tier system. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:496–504. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200404000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pejovic Tanja. Genetic changes in ovarian cancer. Ann Med. 1995;27:73–8. doi: 10.3109/07853899509031940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilks Blake C. Subclassification of ovarian surface epithelial tumors based on correlation of histologic and molecular pathologic data. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2004;23:200–5. doi: 10.1097/01.pgp.0000130446.84670.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singer Gad, Kurman Robert J, Chang Hsueh-Wei, Sarah KR, Shih Cho’ Ie-Ming. Diverse tumorigenic pathways in ovarian serous carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:1223–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62549-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lwabuchi Hiroshi, Sakamoto Masaru, Sakunaga Hotaka, Ma Yen-Ying, Carangiu Maria L, Pinkel Daniel, Yang-Feng Teresa L, Gray Joe W. Genetic analysis of benign, low-grade, and high-grade ovarian tumors. Cancer Res. 1995;55:6172–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sonoda Gonosuke, Palazzo Juan, Manoir Stanislas du, Godwin Andrew K, Feder Madelyn, Yakushiji Michiaki, Testa Joseph R. Comparative genomic hybridization detects frequent overrepresentation of chromosomal material from 3q26, 8q24, 20q13 in human ovarian carcinomas. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1997;20:320–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arnold Norbert, Hagele L, Walz Lioba, Schepp Werner, Pfisterer Jacobus, Bauknecht Thomas, Kiechle M. Overrepresentation of 3q and 8q material and loss of 18q material are recurrent findings in advanced human ovarian cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1996;16:46–54. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2264(199605)16:1<46::AID-GCC7>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiechle Marion, Jacobsen Anja, Schwarz-Boeger Ulrike, Hedderich Jürgen, Pfisterer Jacobus, Arnold Norbert. Comparative genomic hybridization detects genetic imbalances in primary ovarian carcinomas as correlated with grade of differentiation. Cancer. 2001;91:534–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shih Ie-Ming, Torrance Christopher, Sokoll Lori J, Chan Daniel W, Kinzler Kenneth W, Vogelstein Bert. Assessing tumors in living animals through measurement of urinary beta-human chorionic gonadotropin. Nat Med. 2000;6:711–4. doi: 10.1038/76299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobs Ian, Lancaster Jody. The molecular genetics of sporadic and familial epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 1996;6:337–355. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gowen Lori C, Avrutskaya Anna V, Latour Anne M, Koller Beverly H, Leadon Steven A. BRCA1 required for transcription-coupled repair of oxidative DNA damage. Science. 1998;281:1009–12. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5379.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu Xiaoling, Weaver Zoë, Linke Steven P, Li Cuiling, Gotay Jessica, Wang Xin-Wei, Harris Curtis C, Ried Thomas, Deng Chu-Xia. Centrosome amplification and a defective G2-M cell cycle checkpoint induce genetic instability in BRCA1 exon 11 isoform-deficient cells. Mol Cell. 1999;3:389–95. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80466-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chai YuLi, Cui Jian-qi, Shao Ningsheng, Shyam E, Reddy P, Rao Veena N. The second BRCT domain of BRCA1 proteins interacts with p53 and stimulates transcription from the p21WAF1/CIP1 promoter. Oncogene. 1999;18:263–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Zhihong, Singh Meenakshi, Davidson Susan, Rosen Daniel G, Yang Gong, Liu Jinsong. Activation of BTAK expression in primary ovarian surface epithelial cells of prophylactic ovaries. Mod Pathol. 2007:1078–84. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crijns Anne PG, Duiker EW, De Jong Steven, Williams Peter H, Van Dee Zee Ate GJ, De Vries Elisabeth. Molecular prognostic markers in ovarian cancer: toward patient-tailored therapy. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16:152–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yuan Zeng Qiang, Sun Mei, Feldman Richard I, Wang Gen, Ma Xiao-ling, Jiang Chen, Coppola Domenico, Nicosia Santo V, Cheng Jin Q. Frequent activation of AKT2 and induction of apoptosis by inhibition of phosphoinositide-3-OH kinase/Akt pathway in human ovarian cancer. Oncogene. 2000;19:2324–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Plisiecka-Hatasa J, Karpinska Grazyna, Szymanska T, Ziotkowska Iwona, Madry Radoslaw, Timorek Agnieszka, Debniak Jaroslaw, Utanska M, Jedryka Marcin, Chudecka-Gtaz Anita, Klimez Malgorzata, Rembiszewska Alina, Kraszewska Ewa, Dybowski Bartosz, Markowska Janina, Emerich Janusz, Ptuzanska Anna, Goluda Marian, Rzepka-Gorska Izabella, Urbanski Krzysztof, Zielinski Jerzy, Stelmachow Jerzy, Chrabowska M, Kupryjanczyk Jolanta. P21WAF1, P27KIP1, TP53 and C-MYC analysis in 204 ovarian carcinomas treated with platinum-based regimens. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:1078–85. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singer Gad, Oldt Robert, III, Cohen Yoram, Wang Brant G, Sidransky David, Kurman Robert J, Shih Ie-Ming. Mutations in BRAF and KRAS characterize the development of low-grade ovarian serous carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:484–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.6.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sieben Nathalie LG, Macropoulos Patricia, Roemen Guido MJM, Kolkman-Uljee Sandra M, Fleuren Gert Jan, Houmadi Rifat, Diss Tim, Warren Bretta, Al Adnani Mudher, de Goeij Anton PM, Krausz Thomas. The Cancer Genome Project, Adrienne M Flanagan, FRCPath, In ovarian neoplasms, BRAF, but not KRAS, mutations are restricted to low-grade serous tumours. J Pathol. 2004;202:336–40. doi: 10.1002/path.1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shields Janiel M, Pruitt Kevin, McFall Aidan, Shaub Amy, Der Channing J. Understanding Ras; ‘it ain’t over ‘til it’s over’. Trends Cell Biol. 2000;10:147–54. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01740-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elenbaas Brian, Spirio Lisa, Koerner Frederick, Fleming Mark D, Zimonjic Drazen B, Donaher Joana Liu, Popescu Nicholas C, Hah William C, Weinberg Robert A. Human breast cancer cells generated by oncogenic transformation of primary mammary epithelial cells. Genes Dev. 2001;15:50–65. doi: 10.1101/gad.828901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hahn William C, Counter Christopher M, Lundberg Ante S, Beijersbergen Roderick L, Brooks Mary W, Weinberg Robert A. Creation of human tumors cells with defined genetic elements. Nature. 1999;400:464–8. doi: 10.1038/22780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rich Jeremy N, Guo Chuanhai, McLendon Roger E, Bigner Darell D, Wang Xiao-Fan, Counter Christopher M. A genetically tractable model of human glioma formation. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3556–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clark Georgina J, Der Channing J. Aberrant function of the Ras signal transduction pathway in human breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1995;35:133–44. doi: 10.1007/BF00694753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fazili Zia, Sun Wenping, Mittelstaedt Stephen, Cohen Cynthia, Xu Xiang-Xi. Disabled-2 inactivation is an early step in ovarian tumorigenicity. Oncogene. 1999;18:3104–13. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bell Debra A. Origins and molecular pathology of ovarian cancer. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:S19–32. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matias-Guiu Xavier, Prat Jamie. Molecular pathology of ovarian carcinomas. Virchows Arch. 1998;433:103–11. doi: 10.1007/s004280050224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCluskey Lisa L, Dubeau Louis. Biology of ovarian cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 1997;9:465–70. doi: 10.1097/00001622-199709050-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Auersperg Nelly, Edelson Mitchell I, Mok Samuel C, Johnson Steven W, Hamilton Thomas C. The biology of ovarian cancer. Semin Oncol. 1998;25:281–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shih Ie-Ming, Kurman Robert J. Ovarian tumorigenesis; a proposed model based on morphological and molecular genetic analysis. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:1511–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63708-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gad Singer, Robert Stohr, Leslie Cope, Reiko Dehari, Arndt Hartmann, Deng-Fan Cao, Tian-Li Wang, Kurman Robert J, Shih Ie-Ming. Patterns of p53 mutations separate ovarian serous borderline tumors and low- and high-grade carcinomas and provide support for a new model of ovarian carcinogenesis a mutational analysis with immunohistochemical correlation. Am J Surg Patho. 2005;29:218–24. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000146025.91953.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Russell Sarah E, McCluggage Glen W. A multistep model for ovarian tumorigenesis: the value of mutation analysis in the KRAS and BRAF genes. J Pathol. 2004;203:617–9. doi: 10.1002/path.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zwart De J, Geisler John P, Geisler Hans E. Five-year survival in patients with endometrioid carcinoma of the ovary versus those with serous carcinoma. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 1998;19:225–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moreno-Bueno, Gema, Gamallo, Carlos, Perez-Gallego, de Mora Lucia, Calvo Jorge, Asuncion Suarez, Jose Palacios. beta-Catenin expression pattern, beta-catenin gene mutations, and microsatellite instability in endometrioid ovarian carcinomas and synchronous endometrial carcinomas. Diagn Mol Pathol. 2001;10:116–22. doi: 10.1097/00019606-200106000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zheng Xinyu, Rao Xiao-Mei, Snodgrass Christina, Wang Min, Dong Yanbin, McMasters Kelly M, Sam Zhou H. Oncogenic beta-catenin signaling networks in colorectal cancer. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:1522–39. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.11.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harris Tony JC, Peifer Mark. Decisions, decisions: beta-catenin chooses between adhesion and transcription. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:234–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Catasus Lluis, Bussaqlia Elena, Rodriquez Ingrid, Gallardo Alberto, Opns Cristina, Prat Julie. Molecular genetic alterations in endometrioid carcinomas of the ovary; similar frequency of beta-catenin abnormalities but lower rate of microsatellite instability and PTEN alterations than in uterine endometrioid carcinomas. Hum Pathol. 2004;35:1360–8. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2004.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Obata Koshiro, Morland Sarah J, Watson Richard H, Hitchcock Andrew, Trench Georgia Chenevix, Thomas Eric J, Cambell Ian G. Frequent PTEN/MMAC mutations in endometrioid but not serous or mucinous epithelial ovarian tumors. Cancer Res. 1998;58:2095–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tenti Patrizia, Aquzzi Adriano, Riva Conseuelo, Usellini Luciana, Zappatore Rita, Bara Jacques, Micheal Samloff I, Solcia Enrico. Ovarian mucinous tumors frequently express markers of gastric, intestinal, and pancreatobiliary epithelial cells. Cancer. 1992;69:2131–42. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920415)69:8<2131::aid-cncr2820690820>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aguirre Pabla, Scully Rebecca E, Dayal Yogeshwar, DeLellis Ronald A. Mucinous tumors of the ovary with argyrophil cells. An immunohistochemical analysis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1984;8:345–56. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198405000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mandai Masaki, Konishi Ikuo, Kuroda Hideki, Komatsu Takayuki, Yamamoto Shinichi, Nanbu Kanako, Matsushita Katsuko, Fukumoto Manabu, Yamabe Hirohiko, Mori Takahide. Heterogeneous distribution of K-ras-mutated epithelia in mucinous ovarian tumors with special reference to histopathology. Hum Pathol. 1998;29:34–40. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(98)90387-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cuatrecasas Miriam, Villanueva Alberto, Matias-Guiu Xavier, Prat Jaime. K-ras mutations in mucinous ovarian tumors: a clinicopathologic and molecular study of 95 cases. Cancer. 1997;79:1581–6. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970415)79:8<1581::aid-cncr21>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tavassoli Fattaneh, Devilee Peter., editors. World Health Organization classification of tumours: pathology and genetics of tumours of the breast and female genital organs. IARC Press; Lyon, France: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ro Lee Kang, Kenneth R, Scully Robert E. Mucinous tumors of the ovary: a clinicopathologic study of 196 borderline tumors (of intestinal type) and carcinomas, including an evaluation of 11 cases with ‘pseudomyxoma peritonei’. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1447–64. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200011000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nayar Robert, Siriaunkgul S, Robbins KM, McGowan L, Ginzan S, Silverberg SG. Microinvasion in low malignant potential tumors of the ovary. Hum Pathol. 1996;27:521–7. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(96)90156-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rodriguez Ingrid, Prat Jamie. Mucinous tumors of the ovary: a clinicopathologic analysis of 75 borderline tumors (of intestinal type) and carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:139–52. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200202000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hoerl Daniel, Hart William R. Primary ovarian mucinous cystadenocarcinomas: a clinicopathologic study of 49 cases with long-term follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:1449–62. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199812000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seidman Jeffery, Kurman Robert J, Ronnett Brigitte M. Primary and metastatic mucinous adenocarcinomas in the ovaries: incidence in routine practice with a new approach to improve intraoperative diagnosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:985–93. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200307000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Riopel Maureen, Ronnett Brigitte M, Kurman Robert J. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria and behavior of ovarian intestinal-type mucinous tumors: atypical proliferative (borderline) tumors and intraepithelial, microinvasive, invasive, and metastatic carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:617–35. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199906000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wamunyokoli Fred W, Bonome Tomas, Lee Ji-Young, Feltmate Colleen M, Welch William R, Radonovich Mike, Pise-Masison Cindy, Brady John, Hao Ke, Berkowitz Ross S, Mok Samuel, Birrer Michael J. Expression profiling of mucinous tumors of the ovary identifies genes of clinicopathologic importance. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:690–700. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tan David SP, Kaye Stan. Ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma: a continuing enigma. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:355–60. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2006.040030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Skirnisdottir Ingiridur, Seidal Tomas, Karlsson Mikeal G, Sorbe Bengt. Clinical and biological characteristics of clear cell carcinomas of the ovary in FIGO stages I-II. Int J Oncol. 2005;26:177–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Okuda Tsuyoshi, Otsuka Junko, Sekizawa Akihiko, Saito Hiroshi, Makino Reiko, Kushima Miki, Farina Antonio, Kuwano Yuzuru, Okai Takashi. p53 mutations and overexpression affect prognosis of ovarian endometrioid cancer but not clear cell cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;88:318–25. doi: 10.1016/s0090-8258(02)00149-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Osterberg Lorisa, Leron Kristina, Partheen Karolina, Helou Khalil, Harvath Gyorgy. Cytogenetic analysis of carboplatin resistance in early-stage epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2005;163:144–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2005.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rodríguez-Rodríguez Lorna, Sancho-Torres Inés, Leakey Pauline, Gibbon Darlene G, Comerci John T, John W, Ludlow P, Mesoner Clara. CD44 splice variant expression in clear cell carcinoma of the ovary. Gynecol Oncol. 1998;71:223–9. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1998.5108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zorn Kristin K, Bonome Tomas, Gangi Lisa, Chandramouli Gadisetti VR, Awtrey Christopher S, Ginger J, Gardner J, Barrett Carl, Boyd Jeff, Birrer Michael J. Gene expression profiles of serous, endometrioid, and clear cell subtypes of ovarian and endometrial cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:6422–30. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sancho-Torres Inés, Mesonero Clara, Watelet Jean-Luc Miller, Gibbon Darlene, Rodríguez-Rodríguez Lorna. Clear cell carcinoma of the ovary: characterization of its CD44 isoform repertoire. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;79:187–95. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.5938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schwartz Donald R, Kardia Sharon LR, Shedden Kerby A, Kuick Rork, Michailidis George, Taylor Jeremy MG, Misek David E, Wu Rong, Zhai Yali, Darrah Danielle M, Reed Heather, Ellenson Lora H, Giordano Thomas J, Fearon Eric R, Hanash Samir M, Cho Kathleen R. Gene expression in ovarian cancer reflects both morphology and biological behavior, distinguishing clear cell from other poor-prognosis ovarian carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4722–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Claij Nanna, Te Riele Hein. Microsatellite instability in human cancer: a prognostic marker for chemotherapy? Exp Cell Res. 1999;246:1–10. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cai Kathy Qi, Albarracin Constance, Rosen Daniel, Zhong Rocksheng, Zheng Wenxin, Luthra Raiyalakshmi, Broaddus Russell, Liu Jinsong. Microsatellite instability and alteration of the expression of hMLH1 and hMSH2 in ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2004;35:552–9. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xu Zhiyuan, Chen Zhong-Ping, Malapetsa Areti, Alaoui-Jamali Moulay, Bergeron Josee, Monks Anne, Myers Timothy G, Mohr Gerard, Sausville Edward A, Dominic Scudier, Raquel Aloyz, Lawrence Panasci. DNA repair protein levels vis-a-vis anticancer drug resistance in the human tumor cell lines of the National Cancer Institute drug screening program. Anticancer Drugs. 2002;13:511–9. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200206000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reed Eddie, Yu Jing Jie, Davies Antony, Gannon James, Armentrout Steven L. Clear cell tumors have higher mRNA levels of ERCC1 and XPB than other histological types of epithelial ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:5299–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Spentzos Dimitrios, Levine Douglas A, Kolia Shakirahmed, Otu Hasan, Boyd Jeff, Libermann Towia A, Cannistra Stephen A. Unique gene expression profile based on pathologic response in epithelial ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7911–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.9363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Morice Philippe, Joulie Franklin, Rey Annie, Atallah David, Camatte Sophie, Pautier Patricia, Thoury Anne, Lhommé Catherine, Duvillard Pierre, Castaigne Damienne. Are nodal metastases in ovarian cancer chemo resistant lesions? Analysis of nodal involvement in 105 patients treated with preoperative chemotherapy. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2004;25:169–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Simon Richard, Radmacher Michael D, Dobbin Kevin, McShane Lisa M. Pitfalls in the use of DNA microarray data for diagnostic and prognostic classification. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:14–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sheikh-Hamad David, Cacini William, Buckley Arthur R, Isaac Jorge, Truong Luan D, Tsao Chun Chui, Kishore Bellamkonda K. Cellular and molecular studies on cisplatin-induced apoptotic cell death in rat kidney. Arch Toxicol. 2004;78:147–55. doi: 10.1007/s00204-003-0521-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cheng Wenjun, Liu Jinsong, Yoshida Hiroyuki, Rosen Daniel, Naora Honami. Lineage infidelity of epithelial ovarian cancers is controlled by HOX genes that specify regional identity in the reproductive tract. Nat Med. 2005;11:531–7. doi: 10.1038/nm1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Olumi Aria F, Grossfel Gary D, Hayward Simon W, Carroll Peter R, Tlsty Thea D, Cunha Gerald R. Carcinoma-associated fibroblasts direct tumor progression of initiated human prostatic epithelium. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5002–11. doi: 10.1186/bcr138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Krtolica Ana, Parrinello Simona, Lockett Stephen, Desprez Pierre-Yves, Campisi Judith. Senescent fibroblasts promote epithelial cell growth and tumorigenesis: a link between cancer and aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:12072–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211053698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Krtolica Ana, Campisi Judith. Integrating epithelial cancer, aging stroma and cellular senescence. Adv Gerontol. 2003;11:109–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Naylor Stuart M, Stamp Gordon W, Foulkes William D, Eccles Diana, Balkwill Frances R. Tumor necrosis factor and its receptors in human ovarian cancer. Potential role in disease progression. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:2194–206. doi: 10.1172/JCI116446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Burke Frances, Relf Michele, Negus Rupert, Balkwill Frances R. A cytokine profile of normal and malignant ovary. Cytokine. 1996;8:578–85. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1996.0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Scotton Chris J, Milliken David, Wilson John, Raju Shanti, Balkwill Fran. Analysis of CC chemokine and chemokine receptor expression in solid ovarian tumours. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:891–7. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Milliken David, Scotton Chris J, Raju Shanti, Balkwill Frances R, Wilson Julia. Analysis of chemokines and chemokine receptor expression in ovarian cancer ascites. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:1108–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Campisi Judith. Cancer; aging and cellular senescence. In vivo. 2000;14:183–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Campisi Judith. Cellular senescence and apoptosis: How cellular responses might influence aging phenotypes. Exp Gerontol. 2003;38:5–11. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(02)00152-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Campisi Judith, Kim Sahn-ho, Lim Chang-Su, Rubio Miguel. Cellular senescence; cancer and aging: the telomere connection. Exp Gerontol. 2001;36:1619–37. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(01)00160-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tsai Kelvin KC, Chuang Eric Yao-Yu, Little John B, Yuan Zhi-Min. Cellular mechanisms for low-dose ionizing radiation-induced perturbation of the breast tissue microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6734–44. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Campisi Judith. Senescent cells, tumor suppression, and organismal aging: good citizens, bad neighbors. Cell. 2005;120:513–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bavik Claes, Coleman Ilsa, Dean James P, Knudsen Beatrice, Plymate Steven, Nelson Peter S. The gene expression program of prostate fibroblast senescence modulates neoplastic epithelial cell proliferation through paracrine mechanisms. Cancer Re. 2006;66:794–802. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yang Gong, Rosen Daniel G, Zhang Zhihong, Bast Robert C, Jr, Mills Gordon B, Colacino Justin A, Mercado-Uribe Imelda, Liu Jinsong. The chemokine growth-regulated oncogene 1 (Gro-1) links RAS signaling to the senescence of stromal fibroblasts and ovarian tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:16472–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605752103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fathalla Mahmoud. Incessant ovulation--a factor in ovarian neoplasia? Lancet. 1971;2:163. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(71)92335-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cramer Daniel W, Welch William R. Determinants of ovarian cancer risk. II. Inferences regarding pathogenesis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1983;71:717–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ness Roberta B, Cottreau Carrie. Possible role of ovarian epithelial inflammation in ovarian cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1459–67. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.17.1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ness Roberta B, Cottreau Carrie. RESPONSE: re: possible role of ovarian epithelial inflammation in ovarian cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:163. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.17.1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Balkwill Frances R. Possible role of ovarian epithelial inflammation in ovarian cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:162–3. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.2.162a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Freedman Ralph S, Deavers Michael, Liu Jinsong, Wang Ena. Peritoneal inflammation - A Microenvironment for Epithelial Ovarian Cancer (EOC) J Transl Med. 2004;2:23. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-2-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Crissten S, Hagen Tory M, Shigenaga Mark K, Ames Bruce N. Chronic infection and inflammation lead to cancer. In: Parsonnet J, Horning S, editors. Microbes and malignancy: Infection as a Cause of Cancer. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gordon Louis I, Weitzman Sigmund A. Inflammation and cancer: role of phagocyte-generated oxidants in carcinogenesis. Blood. 1990;76:655–663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lane Brian R, Liu Jianguo, Bock Paul J, Schols Dominique, Coffey Michael J, Strieter Robert M, Polverini Peter J, Markovitz David M. Interleukin-8 and growth-regulated oncogene alpha mediate angiogenesis in Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Virol. 2002;76:11570–83. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.22.11570-11583.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Loukinova Elena, Chen Zhong, Van Waes Carter, Dong Gang. Expression of proangiogenic chemokine Gro 1 in low and high metastatic variants of Pam murine squamous cell carcinoma is differentially regulated by IL-1alpha, EGF and TGF-beta1 through NF-kappaB dependent and independent mechanisms. Int J Cance. 2001;94:637–44. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lazar-Molnar Eszter, Hegyesi Hargita, Tóth Sara, Falus Andras. Autocrine and paracrine regulation by cytokines and growth factors in melanoma. Cytokine. 2000;12:547–54. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1999.0614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Greten Florian R, Eckmann Lars, Greten Tim F, Park1 Jin Mo, Li1 Zhi-Wei, Egan Laurence J, Kagnoff Martin F, Karin Michael. IKKbeta links inflammation and tumorigenesis in a mouse model of colitis-associated cancer. Cell. 2004;118:285–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Luo Jun-Li, Maeda Shin, Hsu Li-Chung, Yagita Hideo, Karin Michael. Inhibition of NF-kappaB in cancer cells converts inflammation-induced tumor growth mediated by TNFalpha to TRAIL-mediated tumor regression. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pikarsky Eli, Pora Rinnat M, Stein Ilan, Abramovitch Rinat, Amit Sharon, Kasem Shafika, Gutkovich-Pyest Elena, Urieli-Shoval Simcha, Galun Eithan, Ben-Neriah Yinon. NF-kappaB functions as a tumour promoter in inflammation-associated cancer. Nature. 2004;431:461–6. doi: 10.1038/nature02924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Balkwill Frances R, Mantovani Alberto. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet. 2001;357:539–45. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Adams Anne T, Auersperg Nelly. Transformation of cultured rat ovarian surface epithelial cells by Kirsten murine sarcoma virus. Cancer Res. 1981;41:2063–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Godwin Andrew K, Testa Joseph R, Handel Laura M, Liu Zemin, Vanderveer Lisa A, Tracey Pamela A, Hamilton Thomas C. Spontaneous transformation of rat ovarian surface epithelial cells: association with cytogenetic changes and implications of repeated ovulation in the etiology of ovarian cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1992;84:592–601. doi: 10.1093/jnci/84.8.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nicosia Santo V, Johnson Jennifer H, Streibel Ellen J. Isolation and ultra structure of rabbit ovarian mesothelium (surface epithelium) Int J Gynecol Path. 1984;3:348–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Testa Joseph R, Getts Lori A, Salazar Hernando, Liu Zemin, Handel Laura M, Godwin Andrew K, Hamilton Thomas C. Spontaneous transformation of rat ovarian surface epithelial cells results in well to poorly differentiated tumors with a parallel range of cytogenetic complexity. Cancer Res. 1994;54:2778–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Orsulic Sandra, Li Yi, Soslow Robert A, Vitale-Cross Lynn A, Silvio Gutkind J, Varmus Harold E. Induction of ovarian cancer by defined multiple genetic change in a mouse model system. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:53–62. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(01)00002-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Connolly Denise C, Bao Rudi, Nikitin Alexander Yu, Stephens Kasie C, Poole Timothy W, Hua Xiang, Harris Skye S, Vanderhyden Barbara C, Hamilton Thomas C. Female mice chimeric for expression of the simian virus 40 TAg under control of the MISIIR promoter develop epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1389–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Dinulescu Daniela M, Ince Tan A, Quade Bradley J, Shafer Sarah A, Crowley Denise, Jacks Tyler. Role of K-ras and Pten in the development of mouse models of endometriosis and endometrioid ovarian cancer. Nat Med. 2005;11:63–70. doi: 10.1038/nm1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wu Rong, Hendrix-Lucas Eali, Kuick Rork, Zhai Yali, Schwartz Donald R, Akyol Aytekin, Hanash Samir, Misek David E, Katabuchi Hidetaka, Williams Bart O, Fearon Eric R, Cho Kathleen R. Mouse model of human ovarian endometrioid adenocarcinoma based on somatic defects in the Wnt/beta-catenin and PI3K/Pten signaling pathways. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:321–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Flesken-Nikitin Andrea, Choi Kyung-Chul, Eng Jessica P, Shmidt Elena N, Nikitin Alexander Yu. Induction of carcinogenesis by concurrent inactivation of p53 and Rb1 in the mouse ovarian surface epithelium. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3459–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Auersperg Nelly, Siemens Craig H, Myrdal Sigrid E. Human ovarian surface epithelium in primary culture. In vitro. 1984;20:743–55. doi: 10.1007/BF02618290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Gregoire Lucie, Rabah Raja, Schmelz Eva-Maria, Munkarah Adnan, Roberts Paul C, Lancaster Wayne D. Spontaneous malignant transformation of human ovarian surface epithelial cells in vitro. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:4280–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Nitta Makoto, Katabuchi Hidetaka, Ohtake Hideyuki, Tashiro Hironori, Yamaizumi Masaru, Okamura Hitoshi. Characterization and tumorigenicity of human ovarian surface epithelial cells immortalized by SV40 large T antigen. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;81:10–7. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.6084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Tsao Sai-Wah, Mok Samuel C, Fey Edward G, Fletcher Jonathan A, Wan Thomas SK, Chew Eng-Ching, Muto Michael G, Knapp Robert C, Berkowitz Ross S. Characterization of human ovarian surface epithelial cells immortalized by human papilloma viral oncogenes (HPV-E6E7 ORFs) Exp Cell Res. 1995;218:499–507. doi: 10.1006/excr.1995.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Maines-Bandiera Sara L, Kruk Patricia A, Auersperg Nelly. Simian virus 40-transformed human ovarian surface epithelial cells escape normal growth controls but retain morphogenetic responses to extra cellular matrix. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167:729–35. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(11)91579-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Hahn William C, Stewart Sheila A, Brooks Mary W, York Shoshana G, Eaton Elinor, Kurachi Akiko, Beijersbergen Roderick L, Knoll Joan HM, Meyerson Matthew, Weinberg Robert A. Inhibition of telomerase limits the growth of human cancer cells. Nat Med. 1999;5:1164–70. doi: 10.1038/13495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Liu Jinsong, Yang Gong, Thompson-Lanza Jennifer A, Glassman Armand, Hayes Kimberly, Patterson Andrea, Marquez Rebecca T, Auersperg Nelly, Yu Yinhua, Hahn William C, Mills Gordon B, Bast Robert C., Jr A genetically defined model for human ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1655–63. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Li Bai-Yan, Moharaj Dhanabal, Olson Mary C, Moradi Maziyar, Twiggs Leo, Carson Linda F, Ramakrishnan Sundaram. Human ovarian epithelial cancer cells cultures in vitro express both interleukin 1 alpha and beta genes. Cancer Re. 1992;52:2248–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Zeisler Harald, Tempfer Clemens, Joura Elmar A, Sliutz Gerhard, Koelbl Heinz, Wagner Oswald, Kainz Christian. Serum interleukin 1 in ovarian cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:931–3. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(97)10107-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ivarsson Karin, Ekerydh Anne, Fyhr Ing-marie, Janson Per Olof, Branstrom Mats. Upregulation of interleukin-8 and polarized epithelial expression of interleukin-8 receptor A in ovarian carcinomas. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79:777–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Penson Richard T, Kronish K, Duan Zhenteng, Feller Aynn J, Stark Paul, Cook Sarah E, Duska Linda R, Fuller Arlan F, Goodman AnneKathryn K, Nikrui Najmosama, MacNeill Kimberly M, Matulonis Urusula A, Preffer Fredric I, Seiden Micheal V. Cytokines IL-1beta, IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1, GM-CSF and TNFalpha in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer and their relationship to treatment with paclitaxel. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2000;10:33–41. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1438.2000.00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Mayerhofer Klaus, Bodner Klaus, Bodner-Adler Barbara, Schindl Monika, Kaider Alexandra, Hefler Lukas, Zeillinger Robert, Leodolter Sepp, ArminJoura Elmar, Kainz Christian. Interleukin-8 serum level shift in patients with ovarian carcinoma undergoing paclitaxel-containing chemotherapy. Cancer. 2001;91:388–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Yang Gong, Rosen Daniel G, Mercado-Uribe Imelda, Colacino Justin A, Mills Gordon B, Bast Robert C, Jr, Zhou Chenyi, Liu Jinsong. Knockdown of p53 combined with expression of the catalytic subunit of telomerase is sufficient to immortalize primary human ovarian surface epithelial cells. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:174–82. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Yang Gong, Rosen Daniel G, Colacino Justin A, Mercado-Uribe Imelda, Liu Jinsong. Disruption of the retinoblastoma pathway by small interfering RNA and ectopic expression of the catalytic subunit of telomerase lead to immortalization of human ovarian surface epithelial cells. Oncogene. 2007;26:1492–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]