Abstract

Motivation: Subgraph extraction is a powerful technique to predict pathways from biological networks and a set of query items (e.g. genes, proteins, compounds, etc.). It can be applied to a variety of different data types, such as gene expression, protein levels, operons or phylogenetic profiles. In this article, we investigate different approaches to extract relevant pathways from metabolic networks. Although these approaches have been adapted to metabolic networks, they are generic enough to be adjusted to other biological networks as well.

Results: We comparatively evaluated seven sub-network extraction approaches on 71 known metabolic pathways from Saccharomyces cerevisiae and a metabolic network obtained from MetaCyc. The best performing approach is a novel hybrid strategy, which combines a random walk-based reduction of the graph with a shortest paths-based algorithm, and which recovers the reference pathways with an accuracy of ∼77%.

Availability: Most of the presented algorithms are available as part of the network analysis tool set (NeAT). The kWalks method is released under the GPL3 license.

Contact: kfaust@ulb.ac.be

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Subgraph extraction can be used to predict a meaningful pathway given a biological network (e.g. protein–protein interaction or metabolic network) and a set of query items (e.g. genes, proteins and compounds) defining seed nodes in the network (van Helden et al., 2000). This methodology may serve to predict pathways from a variety of data types, such as clusters of co-expressed genes, operons, phylogenetic profiles or protein levels.

Zien et al. (2000) inferred pathways from a biological network weighted according to gene expression levels as measured with microarrays. They construct a bipartite metabolic network consisting of compound and reaction nodes and subsequently enumerate all possible paths between a source (d-glucose) and a target compound (pyruvate) under certain constraints. The score of each path is computed on the basis of expression values of the genes catalyzing the enzymes involved in this path. This method ranks predicted paths according to their degree of up- or down-regulation.

Ideker et al. (2002) extended this idea to the extraction of more complex, non-linear sub-networks in protein–protein and protein–DNA networks given yeast gene expression data. Sub-networks are considered active whenever they involve highly expressed genes. Such sub-networks can be identified by sampling the space of possible sub-networks with simulated annealing.

Scott et al. (2005) also search for sub-networks in protein–protein and protein–DNA interaction networks given gene expression data. To our knowledge, they are the first to apply algorithms solving the Steiner tree problem (Hwang et al., 1992) on biological networks in order to connect nodes of interest (i.e. differentially expressed genes).

Rajagopalan and Agarwal (2005) integrate various data sources (TransFac, HumanCyc and Ingenuity Pathways Knowledge Base) into a network of gene–metabolite relationships. Query nodes in this network are connected by an algorithm based on breadth-first search. A key contribution of these authors is the systematic evaluation of their subgraph extraction approach on both simulated data and known pathways taken from BioCarta.

Noirel et al. (2008) apply sub-network extraction to proteomics data (i.e. enzyme level ratios, measured by mass spectrometry) from the cyanobacterium Nostoc. A sub-network is extracted from a weighted KEGG metabolic network by generating paths around each up-regulated enzyme node up to a given maximal weight and subsequently filtering these paths according to the number of up-regulated enzymes contained in them. The filtered paths are then merged to form a network whose connected components are considered as the extracted sub-networks.

Dittrich et al. (2008) identify high-scoring sub-networks in protein–protein interaction networks with a strategy similar to Scott et al. (2005), by applying an algorithm that solves the Steiner tree problem exactly. Interestingly, their method allows to report sub-optimal solutions with a user-specified distance to previously listed solutions. The pathway prediction approach is validated on simulated data.

Antonov and co-workers predict metabolic pathways from KEGG data and from input genes (Antonov et al., 2008) or input compounds (Antonov et al., 2009). Query nodes (genes or compounds) separated by one edge are added to a growing sub-network that may consist of several components. The component covering most query nodes is considered as the inferred pathway. The procedure is repeated for distances of 2, 3,… edges, resulting in a set of distance-specific predictions. This sub-network extraction procedure is available via two Web tools specific to metabolic data.

In previous publications (Croes et al., 2006; Faust et al., 2009; van Helden et al., 2002), we investigated different ways to apply two-ends path finding to predict metabolic pathways from a pair of query reactions or compounds. However, path finding requires to specify a single start and a single end node. It cannot deal with branched pathways or with sets of query reactions. A more challenging question is to predict pathways from multiple seed nodes (e.g. reactions catalyzed by a cluster of co-expressed genes), by extracting the sub-network that connects them at best.

In this article, we assess the capability of sub-network extraction algorithms to predict metabolic pathways given a metabolic network and a set of seed reactions. We evaluate the performance of four different algorithms (combined in seven approaches) on the basis of 71 pathways obtained from MetaCyc. One of these algorithms (pairwise K-shortest paths) has been developed for this study and two other algorithms (Takahashi–Matsuyama, kWalks) have apparently not yet been applied before to sub-network extraction in biological networks.

The extraction techniques considered here are not specific to metabolic networks or gene expression clusters. They can in principle be applied to any biological network (reactions, protein interactions and signal transduction) and to any dataset generating specific nodes of interest (e.g. functionally related groups of genes/enzymes as derived from phylogenetic co-occurrence, operons, gene fusion events, etc.).

2 METHODS

2.1 Weight policies

Metabolic networks contain hub compounds such as H2O, NADP and ATP, which are involved in a large number of reactions. A naive graph traversal algorithm would preferentially cross these compounds, resulting in biochemically invalid paths that connect for instance d-glucose with pyruvate in one reaction step via ADP. Various solutions to this problem have been proposed, among others to filter out pool metabolites (van Helden et al., 2002), to consider compound structures (Arita, 2000; Blum and Kohlbacher, 2008; Rahman et al., 2004) or to weight compounds according to their degree (Croes et al., 2005, 2006). We adopted the weighting approach and tested three different weight policies. The simplest one (‘unit weight’) sets all node weights to one. The second policy (‘compound degree weight’) penalizes highly connected compounds by assigning to each compound a weight equal to its degree, whilst setting to each reaction a weight of one. The third weight policy (‘inflated compound degree weight’) takes the square of the node weights defined by the second weight policy. The purpose is to enlarge weight differences between highly and weakly connected compound nodes. For most algorithms, the node-weighted network had to be converted to an edge/arc-weighted network, by taking for each edge/arc the mean of weights of its two adjacent nodes.

2.2 Metabolic network construction

To predict metabolic pathways, we need to represent metabolic data as a network (or a graph, to use the mathematical term).

BioCyc (Caspi et al., 2008) is a metabolic database storing both predicted and experimentally elucidated metabolic information. MetaCyc (Krieger et al., 2004) belongs to the well-curated tier (Tier 1) of BioCyc and contains only experimentally validated pathways.

We constructed a bipartite, directed graph from all small molecule entries and their associated reactions contained in the OWL file of MetaCyc (Release 11.0). The resulting graph consists of 4 891 compound nodes and 5 358 reaction nodes. As discussed in Croes et al. (2005), reactions that are annotated as irreversible can be reversed depending on physiological conditions (substrate and product concentrations, and temperature). Consequently, we represent each reaction as a pair of nodes, for the forward and the reverse directions, respectively. To prevent the paths-based algorithms from crossing the same reaction twice, forward and reverse direction are mutually exclusive. After this duplication of reaction nodes, we obtain a directed network with 15 607 nodes and 43 938 edges, referred hereafter as the MetaCyc network.

We constructed two variants of the MetaCyc network: the directed one described above and an undirected network, in which reaction nodes are not duplicated. However, in both cases the weight matrix is designed to be symmetric.

2.3 Reference pathways

We obtained a selected set of 71 known Saccharomyces cerevisiae pathways from MetaCyc (Release 11.0). All pathways in this reference set consist of at least five nodes and are included in the largest connected component of the MetaCyc network. On average, the pathways are composed of 13 nodes and in addition, more than half of them are branched and/or cyclic.

In our previous work on two-end path finding (Croes et al., 2006; Faust et al., 2009) we had to linearize the reference pathways in order to evaluate path finding. Since multiple-end pathway prediction is designed to handle branched pathways, this processing step is no longer necessary.

2.4 Algorithms

2.4.1 Common features of the extraction algorithms

All algorithms extract sub-networks by connecting a set of selected nodes (the seed nodes) in the input network. The problem of connecting seed nodes in a weighted network such that the weight of the resulting sub-network is minimized is an instance of the Steiner tree problem, which is known to be NP-complete (Karp, 1972). The Takahashi–Matsuyama, the Klein–Ravi and pairwise K-shortest paths algorithms all call a (K-) shortest paths algorithm to tackle the Steiner tree problem approximately with different heuristics.

The kWalks approach takes a qualitatively different approach to subgraph extraction by efficiently computing the set of edges most likely to be used while randomly walking from a seed node to any other one. The weights in the network obviously influence the random walks together with the network topology.

2.4.2 Challenges faced by metabolic pathway inference algorithms

The metabolic pathway inference algorithms face the following challenges:

Be able to cope with weighted networks.

Allow the input graph to be directed. In undirected graphs the paths-based approaches would not differentiate between reaction products and substrates, and would thus establish artefactual links from substrate to substrate, or from product to product. This requirement is not met by the implementation of Klein–Ravi used for evaluation.

Treat forward and reverse direction of reactions as mutually exclusive. Without mutual exclusion of forward and reverse reaction direction nodes, the same reaction may appear twice in a shortest path. The kWalks method does not distinguish between forward and reverse reactions because it is not based on the explicit computation of paths.

Be able to process seed node groups instead of seed nodes. The reaction mechanism(s) of an enzyme is (are) usually described by its EC number(s). But this annotation is ambiguous, because reactions with the same EC number may differ by their co-factor or by their substrate. For instance, homoserine dehydrogenase with EC number 1.1.1.3 converts l-homoserine into l-aspartate 4-semialdehyde. There are two reactions associated to this EC number (having either NAD+ or NADP+ as a co-factor), but only one of these may actually occur in the pathway to be inferred. An algorithm handling seed node groups can treat all reactions of EC number 1.1.1.3 as belonging to the same group. As soon as one of the group members is connected to the sub-network, the seed node group is considered to be connected as well. To address this last requirement, we applied the graph transformation suggested by Duin et al. (2004). The idea is to introduce pseudo nodes, which connect all members of a seed node group in the input graph. Thus, when we mention seed nodes, these nodes may be artificial nodes that represent a group of seeds considered as equivalent, and from which only one has to be included in the result.

Each algorithm takes as input the graph, the seed nodes and a weight policy. kWalks requires additional parameters discussed in Section 2.4.6.

We will first discuss the shortest paths-based approaches. Except for Klein–Ravi, they rely on the Recursive Enumeration Algorithm (REA) (Jimenez and Marzal, 1999) to compute K-shortest paths. REA enumerates all paths between a start and an end node in the order of their length. In a weighted graph, paths are listed in the order of their weight. Note that according to the definition of a path, a node can occur only once in the path. The value of K is dynamically set such that all paths of minimal weight are collected. The paths returned by REA are filtered to avoid paths containing mutually exclusive nodes.

The computational complexities of all algorithms described below are expressed in terms of n and m, the number of nodes and edges, respectively, in the input graph, as well as s, the number of seed nodes.

2.4.3 Klein–Ravi

The algorithm by Klein and Ravi (1995) is a heuristic to solve the node-weighted variant of the Steiner tree problem. First, the distance between any node pair in the graph is obtained with an all-to-all shortest paths algorithm such as Dijkstra (1959). A set of trees is considered where each tree initially consists of a single seed node. At each step of the algorithm, a node and a subset of the remaining trees are selected such that the cost of tree merging is minimized. At least two trees have to be merged in each step. The cost of tree merging is computed as the sum of the weight of the selected node and the weights of the shortest paths between the selected node and the selected tree subset. This sum is divided by the number of trees in the selected subset. The algorithm terminates when all trees are merged. The same implementation as in Scott et al. (2005) has been used to evaluate this algorithm. The implementation was kindly provided by Betzler (2005). The computational complexity of this approach is O(n2 log n + nm + ns3 log s).

2.4.4 Takahashi–Matsuyama

The algorithm by Takahashi and Matsuyama (1980) initializes the sub-network with a node chosen at random among the s seeds. It then proceeds by identifying in each step the lightest path(s) between any of the remaining seed nodes and any node in the sub-network (note that pseudo nodes can be introduced to treat all nodes in the sub-network as equivalent start nodes and all remaining seed nodes as equivalent end nodes). The lightest path(s) is merged with the sub-network. The computational complexity of this approach is O(s(m + Kn log(m/n))).

2.4.5 Pairwise K-shortest paths

In the first step, REA is called successively on each pair of seed nodes. The resulting path sets are stored in a path matrix, and the minimal weight between each node pair is stored in a distance matrix. In the second step, the sub-network is constructed from the path sets, starting with the lightest path set. Step-wise, path sets are merged with the subgraph by increasing order of their weight. The process stops if either all seeds belong to one connected component of the sub-network or all path sets have been merged with the sub-network.

The computational complexity of this approach is O(s2 (m + Kn log(m/n))), because the REA algorithm is called O(s2) times.

2.4.6 kWalks

The kWalks method is a generic algorithm (Dupont et al., 2006) to build a most relevant subgraph connecting seed nodes in a large graph, in the present case a metabolic network. The subgraph contains the most relevant edges and the nodes induced by those edges. The relevance of an edge is measured as the expected number of times it is visited along random walks connecting seed nodes. These expected passage times reflect both the topology of the network and the edge weights. They follow from an interpretation of the graph as a Markov chain (Kemeny and Snell, 1983) characterized by a transition probability matrix P.

The probability of transition from node i to node j is given by  where wij denotes the weight assigned to the edge i → j. For each seed node x, the sub-matrix xP denotes the transition probability matrix restricted to the lines and columns associated to x and all non-seed nodes. Expected passage times can be computed from the fundamental matrix xN = (I −x P)−1. The entry xNxi gives the expected number of times node i is visited during walks starting in x and ending in any other seed node. The expected passage time xE(i, j) along an edge i → j is obtained by multiplying xNxi with the transition probability Pij. Finally, the relevance of an edge i → j is obtained by averaging xE(i, j) over the s seed nodes.

where wij denotes the weight assigned to the edge i → j. For each seed node x, the sub-matrix xP denotes the transition probability matrix restricted to the lines and columns associated to x and all non-seed nodes. Expected passage times can be computed from the fundamental matrix xN = (I −x P)−1. The entry xNxi gives the expected number of times node i is visited during walks starting in x and ending in any other seed node. The expected passage time xE(i, j) along an edge i → j is obtained by multiplying xNxi with the transition probability Pij. Finally, the relevance of an edge i → j is obtained by averaging xE(i, j) over the s seed nodes.

A straightforward implementation of the kWalks algorithm is computationally demanding for a large graph: its complexity is O(sn3), since it would rely on s matrix inversions for a graph with n nodes. In practice, the fundamental matrix can, however, be approximated by limiting the walks to a maximal number of L steps and using forward–backward recurrences (Callut, 2007). The computational complexity of the bounded kWalks is O(sLm). Since s, the number of seed nodes, as well as L are typically fixed and have values orders of magnitude lower than m, this approach essentially offers a linear time complexity with respect to the number of graph edges. Bounding the walk length is not only convenient from a computational viewpoint, it also allows to control the level of locality (or, conversely, the level of diffusion through the network) while connecting seed nodes. In all the reported experiments, L was fixed to 50 based on preliminary evaluations (Dupont et al., 2006).

As such the kWalks algorithm computes edge and node relevance from random walks connecting the seed nodes. A subgraph is obtained by keeping only those edges above a minimal relevance threshold. In our experiments, the relevance threshold is automatically fixed such that the subgraph induced by the selected edges is weakly connected. The sub-networks extracted by kWalks may contain branches ending in non-seed nodes. We remove these branches in a final pruning step.

The edge relevances computed by kWalks can serve as new edge weights. kWalks can then be run on the input graph with updated weights. This iterative process may be repeated a number of times to increase the discrimination between more and less relevant edges. The parameter that determines how often kWalks is iterated is named kWalks iteration number.

2.4.7 Hybrid approaches

On one hand, the kWalks approach is designed to be more sensitive than specific by returning a sub-network whose edges are more likely to be used along walks connecting the seed nodes. Such a sub-network may be significantly smaller than the initial network yet not highly specific to form relevant pathways. On the other hand, the computational complexity of paths-based approaches may prevent them from being effective when applied to a large network. Those observations motivate the use of an hybrid strategy where the kWalks method is combined with paths-based algorithms. Such a hybrid approach runs in two steps: kWalks extracts a sub-network representing a fixed proportion of the input network and the shortest paths-based algorithm is launched on this intermediate sub-network to obtain the final pathway. In the first step of the hybrid algorithm, kWalks may be iterated.

Combining kWalks with paths-based approaches requires two new parameters: (i) Size of the sub-network. kWalks extracts a sub-network whose size is fixed to a given percentage of the number of nodes in the input network. In our experiments, this parameter is usually fixed between 0.5% and 5%. The extracted sub-networks tend to be larger than with the weak connectivity constraint but are subsequently filtered with a paths-based approach. (ii) Input or computed weights. The paths-based algorithms may either use the input weights or the edge/node relevances computed by kWalks in the first step. These relevances can be obtained from a single kWalks run or from the last iteration of repeated kWalks.

2.5 Evaluation procedure

2.5.1 Accuracy of sub-network extraction

We define as true positive (TP) a non-seed node that is present in the reference as well as the inferred pathway. A false negative (FN) is a non-seed node present in the reference but missing in the inferred pathway and a false positive (FP) is a non-seed node found in the inferred pathway but absent from the reference. The sensitivity (Sn) is defined as the ratio of correctly inferred nodes versus all reference nodes:

, whereas the positive predictive value (PPV) gives the ratio of correctly inferred nodes versus all inferred nodes:

, whereas the positive predictive value (PPV) gives the ratio of correctly inferred nodes versus all inferred nodes:  . We calculate the accuracy as the geometric mean between sensitivity and PPV

. We calculate the accuracy as the geometric mean between sensitivity and PPV  .

.

2.5.2 Experiments

For each of the 71 reference pathways, we first select the terminal reactions as seeds, we infer a pathway that interconnects them, and we compare the nodes of the inferred pathways with those of the annotated pathway. Then, we progressively increase the number of seeds by adding reactions randomly selected from the reference pathway, and re-do the inference and evaluation, until all reactions of the pathway are selected as seeds. We define as one experiment the set of all the pathway inferences performed for a given parameter value combination (e.g. pairwise K-shortest paths on directed MetaCyc network with compound degree weight). In total, we carried out 110 such experiments.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Global performance of pathway inference algorithms

3.1.1 Comparison of algorithms

The average geometric accuracy of a selected number of experiments is listed in Table 1. The full experiment table is available as Supplementary Table ST1. The strategy resulting in the highest accuracy combines the Takahashi–Matsuyama algorithm with kWalks. All the top experiments involve a compound-weighted, directed MetaCyc network and, in case of the kWalks algorithm, an iteration number larger than one.

Table 1.

Selected set of experiments, their conditions and results

| Algorithm | Directed | Input | kWalks | Size of | kWalks | Mean Sn | Mean PPV | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| graph | weighting | iteration | sub-network | weights | accg | |||

| scheme | number | extracted by | re-used | |||||

| kWalks (%) | in hybrid | |||||||

| Takahashi–Matusyama/kWalks | TRUE | Compound degree | 1 | 5 | FALSE | 77.13 | 77.97 | 76.81 |

| Takahashi–Matsuyama | TRUE | Compound degree | 0 | – | – | 75.90 | 77.25 | 75.83 |

| pairwise K-shortest paths/kWalks | TRUE | Compound degree | 1 | 0.5 | FALSE | 68.89 | 78.90 | 71.79 |

| pairwise K-shortest paths/kWalks | TRUE | Compound degree | 6 | 5 | FALSE | 70.20 | 69.10 | 68.22 |

| pairwise K-shortest paths | TRUE | Compound degree | 0 | – | – | 69.95 | 68.73 | 68.03 |

| kWalks | TRUE | Compound degree | 3 | – | – | 71.49 | 68.54 | 67.96 |

| kWalks | TRUE | Inflated compound | 6 | – | – | 71.06 | 68.62 | 67.90 |

| degree | ||||||||

| pairwise K-shortest paths/kWalks | TRUE | Compound degree | 3 | 5 | FALSE | 69.19 | 69.37 | 67.86 |

| Klein–Ravi/kWalks | FALSE | Compound degree | 1 | 5 | FALSE | 63.21 | 68.03 | 64.10 |

| kWalks | TRUE | Unit | 3 | – | – | 61.40 | 71.33 | 64.30 |

| kWalks | TRUE | Unit | 6 | – | – | 60.00 | 71.75 | 63.53 |

| Klein–Ravi | FALSE | Compound degree | 0 | – | – | 62.55 | 66.27 | 63.05 |

| kWalks | TRUE | Unit | 1 | – | – | 62.13 | 65.93 | 61.83 |

| pairwise K-shortest paths/kWalks | TRUE | Unit | 1 | 5 | TRUE | 46.91 | 69.38 | 55.32 |

| Takahashi–Matsuyama | TRUE | Unit | 0 | – | – | 60.02 | 53.83 | 52.74 |

| pairwise K-shortest paths | TRUE | Unit | 0 | – | – | 71.37 | 35.87 | 42.86 |

Each table row represents one experiment. Each experiment was performed on 71 reference pathways with varying seed reaction number, comprising 406 launches of the tested pathway inference algorithm for the indicated conditions; accg, geometric accuracy.

The performance of paths-based algorithms in the unweighted (unit weight), directed MetaCyc network is at most 53% whereas kWalks (without iteration) reaches an average accuracy of 62% in the same conditions. Hence kWalks is able to assign edge relevances even without a dedicated weight policy for the problem at hand, such as the compound degree weighting scheme for metabolic networks. All approaches however benefit from such a dedicated weight policy.

In the pairwise K-shortest paths/kWalks hybrid approach, kWalks is configured to extract 5% of the input network. If this percentage is reduced to 0.5% (the optimum among 22 different sub-network sizes tested), the average accuracy increases by 3%. Obviously, the size of the intermediate sub-network should not go below a certain limit as it should be large enough to contain a metabolic pathway.

Combining a paths-based algorithm with kWalks tends to reduce its runtime. Supplementary Figure SF1 compares run-times for all seven pathway inference algorithms.

3.1.2 Influence of parameter setting

We measured the impact of alternative parameter values over a subset of the experiments as measured by a paired signed Wilcoxon rank test (Supplementary Table ST2). The parameter values having highest impact on the pathway inference accuracy are in this order: compound degree weight and inflated compound degree weight outperform unit weight, directed network outperforms undirected network, kWalks supersedes hybrid approaches and three kWalk iterations are better than a single run.

The superiority of the two degree-based weighting schemes over unit weights is in agreement with previous results (Croes et al., 2005, 2006), which show that weighting the metabolic network avoids irrelevant hub compounds. It is also no surprise that the directed MetaCyc network yields higher accuracies than the undirected one, because the directed network prevents the traversal from substrate to substrate or from product to product.

It might seem surprizing that when all experiments are taken together, kWalks alone outperforms the pairwise K-shortest paths hybrid, whereas the five top-raking approaches rely either on hybrid approach or path finding alone. The reason is that kWalks, as explained above, deals well with the unit weight policy, whereas the hybrid only performs well if it can either use weights generated by kWalks or by a weight policy that penalizes hub compounds. However, if run with optimal parameter values, both algorithms are among the top experiments (Table 1). Iterating kWalks improves the accuracy, as it increases the difference between relevant and irrelevant edges.

3.2 Study cases

All study cases were analyzed with the hybrid algorithm combining Takahashi–Matsuyama and kWalks in the directed, compound-weighted MetaCyc network.

The kWalks was not iterated and the original compound degree weights (instead of the relevances computed by kWalks) were given as input weights to Takahashi–Matsuyama's algorithm. The size of the subgraph extracted by kWalks in the first step of the hybrid was set to 5%.

Since we cannot infer reaction directions due to the way we constructed the MetaCyc network, inferred pathways are displayed as undirected graphs. The annotated pathways have been obtained from EcoCyc version 13.1 (Keseler et al., 2009).

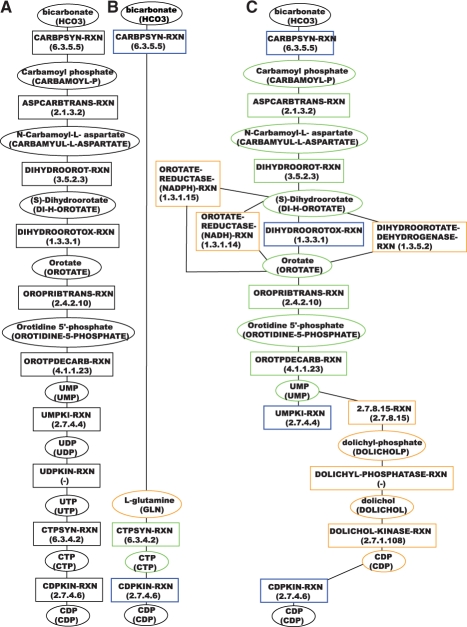

3.2.1 De novo synthesis of pyrimidine ribonucleotides in Escherichia coli

The de novo synthesis of pyrimidine ribonucleotides pathway in E.coli produces CDP from l-glutamine in a series of 10 subsequent reaction steps (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Pathway inference results for the pyrimidine ribonucleotides de novo biosynthesis pathway (MetaCyc identifier: PWY0-162) in E.coli. (A) Reference pathway. (B) Pathway inferred with two seeds in the compound-weighted, directed MetaCyc network. (C) Pathway inferred with four seeds in the same network. Ellipses represent compounds, rectangles reactions. Compounds and reactions are labeled with their MetaCyc identifiers in capital letters, compounds in addition with their name and reactions with their associated EC number. Seed nodes have a blue border, TP nodes a green and FPs an orange border.

Two-end path finding results in a metabolic pathway that bypasses a large segment of the annotated pathway by taking a shortcut via l-glutamine (Fig. 1B). Consequently, the geometric accuracy is low (28%). The pathway in Figure 1B is biochemically irrelevant, as it suggests that CTP can be synthesized from glutamine within one step.

With two additional seed nodes (Fig. 1C), a large part of the reference pathway is recovered (geometric accuracy reaches 59%).

Not surprizingly, the result is more accurate when more information can be provided in the form of additional seed nodes. Such additional information could, however, add spurious paths between seed nodes, hence decreasing PPV, but the overall effect is clearly positive in this case.

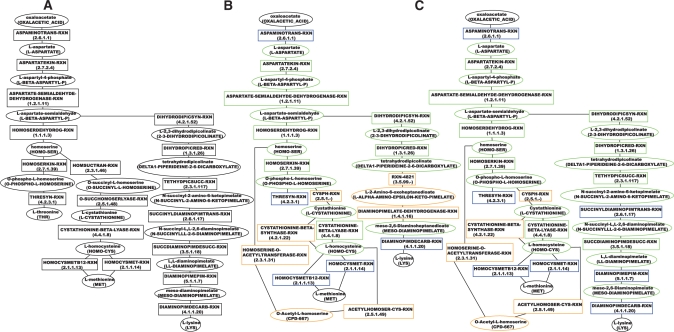

3.2.2 Lysine, threonine and methionine biosynthesis in E.coli

The previous example illustrates the benefit of multi-seed pathway inference in the case of linear pathways. Another interest of the approach is its capacity to deal with branched metabolic pathways or super-pathways.

The lysine, threonine and methionine biosynthesis super-pathway of E.coli is a good example of a branched pathway that cannot be treated with two-end path finding (Fig. 2A). This pathway starts from oxaloacetate, the common precursor of the three amino acids l-lysine, l-methionine and l-threonine. The pathway is linear up to l-aspartyl-semialdehyde, after which it branches towards the three different end products.

Fig. 2.

Pathway inference results for the superpathway of lysine, threonine and methionine biosynthesis I (MetaCyc identifier: P4-PWY) in E.coli. (A) Reference pathway. (B) Pathway inferred with the five terminal reactions as seeds in the compound-weighted, directed MetaCyc network. (C) Pathway inferred with the terminal and two additional intermediate reactions in the same network. Ellipses represent compounds, rectangles reactions. Compounds and reactions are labeled with their MetaCyc identifiers in capital letters, compounds in addition with their name and reactions with their associated EC number. Seed nodes have a blue border, TP nodes a green and FPs an orange border.

Given the terminal reactions with MetaCyc identifiers ASPAMINOTRANS-RXN, THRESYN-RXN, DIAMINOPIMDECARB-RXN, HOMOCYSMETB12-RXN and HOMOCYSMET-RXN, the pathway shown in Figure 2B is inferred from the MetaCyc network. It recovers large parts of the reference pathway, but misses parts of the annotated lysine and threonine branches, resulting in a geometric accuracy of 65%.

However, the inferred lysine branch is a biochemically valid metabolic pathway, which is known to be active, e.g. in Clostridium tetani (MetaCyc pathway identifier: PWY-2942).

Additional seed reactions are needed to distinguish the E.coli variant of lysine biosynthesis from this alternative. Such seeds may for instance be derived from expression microarray experiments, revealing a set of enzymes whose transcription is regulated in response to some substrate or culture condition. Such expression clusters are likely to include terminal as well as a few intermediate enzyme-coding genes, such as the argD, whose product catalyzes the intermediate seed reaction SUCCINYLDIAMINOPIMTRANS-RXN, and which is negatively regulated by the transcription factor ArgR.

When repeating pathway inference with two additional reactions from the lysine branch (DIAMINOPIMEPIM-RXN and SUCCINYLDIAMINOPIMTRANS-RXN), the E.coli lysine biosynthesis pathway is found (Fig. 2C) and the geometric accuracy reaches 85%.

4 DISCUSSION

In this article, we presented different sub-network extraction techniques that can be applied to predict metabolic pathways from metabolic networks, given a set of seed reactions.

From our evaluation, we can conclude that a combination of Takahashi–Matsuyama and kWalks is globally most suited. The evaluation also shows that a directed, weighted metabolic network performs better than an undirected, unweighted one. Consequently, if a good weight policy for the metabolic network under study is at hand, it should be given as input to both algorithms, else the paths-based algorithm can be launched on the weights computed by kWalks. The accuracy of pathway inference can be further increased by iterating kWalks and/or by reducing the size of the sub-network extracted by kWalks in the first step of the hybrid.

The hybrid approach combines the strengths of two different sub-network extraction strategies: kWalks is designed to capture the part of a network that is most relevant to connect the given seed nodes, resulting in a high sensitivity, but at the cost of a low PPV. FPs introduced by kWalks can be discarded by a more stringent shortest paths-based algorithm. In addition, combining shortest-paths-based algorithms with kWalks not only increases their accuracy but also their speed. KWalks, as the fastest of all tested algorithms, quickly reduces the input network size and thus the runtime of the subsequent shortest-paths-based algorithm.

Our pathway prediction approach is subjected to a number of limitations. Paths-based approaches only partly infer cyclic or spiral-shaped pathways (the same enzymes acting repeatedly on a growing chain, e.g. fatty acid biosynthesis). kWalks alone is able to return general subgraphs but possibly at the cost of decreasing specificity. For certain pathways situated in the densely interconnected region of the metabolic network (such as the TCA cycle and the glycolysis pathway), a large number of seed nodes is required in order to distinguish them from alternative pathways. In addition, prediction accuracy is of course dependent on data quality. To infer a metabolic pathway from a metabolic network, the network must contain all nodes and edges of the pathway.

A strength of sub-network extraction is its ability to handle large networks (several thousands of nodes) efficiently. The approach is sufficiently generic to be applied to any biological network. In addition, it has a capacity to integrate other data (e.g. scores from high-throughput experiments) by weighting the network. Another strength is its capability to handle seed node groups, which allows to cope with ambiguous gene-reaction mappings.

The sub-network extraction method proposed here is distinct from and complementary to other metabolic network analysis methods such as flux balance analysis (FBA; Edwards and Palsson, 2000; Lee et al., 2006) or elementary mode (EM) analysis (Schuster et al., 1999; Trinh et al., 2009). Those respective approaches differ by their input types, output types and by their potential applications, and can provide complementary insights into the metabolism of a given organism. FBA aims at predicting a set of feasible metabolic flux distributions optimizing a specific objective (such as biomass production) for a given organism in a specific environment. FBA requires as input a metabolic network including stoichiometric coefficients plus an objective function to constrain the number of solutions. EM analysis is similar to FBA, but does not require an objective function. Thus, it enumerates all allowable metabolic states satisfying an additional non-decomposability constraint (Schuster et al., 1999). These methods have important applications in bioengineering, especially for microbe-based production of organic molecules.

In contrast, the presented method aims to predict metabolic pathways given a metabolic network and a set of seed nodes, which can be compounds, reactions or enzyme-coding genes. Seed genes can be collected from a variety of data sources: co-expression clusters, operons, regulons, synteny groups, metabolomic profiles or any other criterion suggesting that a set of enzyme-coding genes is potentially involved in a common function.

An immediate application of sub-network extraction is to interpret expression profiles obtained from microarray data, in order to understand the specific metabolic processes that are up- or down-regulated in response to changed conditions.

Another application is the inference of bacterial metabolic pathways from genome organization (operons, regulons and synteny), and the analysis of cross-species pathway variants. Metabolic sub-network extraction can be applied to predict metabolic pathways for an organism whose genes are functionally annotated but whose metabolism is not yet known. In such a case, a network constructed from metabolic information taken from related organisms might be more appropriate than a complete metabolic network containing all known reactions and compounds in a given database as in this study.

There are various ways to build and weight an organism-specific metabolic network: the first is to simply build the network from reactions occurring in the selected set of organisms. In a less restrictive approach, the complete network could be weighted in such a way that reactions occurring in the given organisms are favored over other reactions. Similarly, gene expression and other high-throughput data could be taken into account during network construction by converting expression ratios (or other scores derived from the dataset) into node weights.

The pathway inference algorithms were added to NeAT (Brohée et al., 2008) at http://rsat.ulb.ac.be/neat/. A generic kWalks implementation is freely available at www.ucl.ac.be/mlg/index.php?page=Softwares.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the former aMAZE team for their graph library and Nadja Betzler for providing us with her implementation of the Klein–Ravi algorithm. We acknowledge Jean-Noël Monette and Pierre Schaus from the INGI team at UCL for making publicly available their improvement of the REA code.

Funding: Actions de Recherches Concertées de la Communauté Françcaise de Belgique (ARC grant number 04/09-307 to K.F.); The BiGRe laboratory: member of the BioSapiens Network of Excellence funded under the sixth Framework program of the European Communities (LSHG-CT-2003-503265); Belgian Program on Interuniversity Attraction Poles, initiated by the Belgian Federal Science Policy Office, project P6/25 (BioMaGNet).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Antonov A, et al. KEGG spider: interpretation of genomics data in the context of the global gene metabolic network. Genome Biol. 2008;9 doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-12-r179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonov A, et al. TICL - a web tool for network-based interpretation of compound lists inferred by high-throughput metabolomics. FEBS J. 2009;276:2084–2094. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.06943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arita M. Metabolic reconstruction using shortest paths. Simul. Pract. Theory. 2000;8:109–125. [Google Scholar]

- Betzler N. Master's Thesis. Germany: Wilhelm-Schickard-Institut für Informatik, Universität Tübingen; 2005. Steiner tree problems in the analysis of biological networks. [Google Scholar]

- Blum T, Kohlbacher O. MetaRoute: fast search for relevant metabolic routes for interactive network navigation and visualization. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2108–2109. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brohée S, et al. NeAT: a toolbox for the analysis of biological networks, clusters, classes and pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:W444–W451. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callut J. PhD Thesis. Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium: Université catholique de Louvain; 2007. First passage times dynamics in Markov models with applications to HMM induction, sequence classification, and graph mining. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi R, et al. The MetaCyc database of metabolic pathways and enzymes and the BioCyc collection of Pathway/Genome databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D623–D631. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croes D, et al. Metabolic PathFinding: inferring relevant pathways in biochemical networks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W326–W330. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croes D, et al. Inferring meaningful pathways in weighted metabolic networks. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;356:222–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.09.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra EW. A note on two problems in connexion with graphs. Numerische Mathematik. 1959;1:269–271. [Google Scholar]

- Dittrich MT, et al. Identifying functional modules in protein-protein interaction networks: an integrated exact approach. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:i223–i231. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duin CW, et al. Solving group Steiner problems as Steiner problems. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2004;154:323–329. [Google Scholar]

- Dupont P, et al. Research Report UCL/FSA/INGI RR 2006-07. Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium: 2006. Relevant subgraph extraction from random walks in a graph. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J, Palsson B. Metabolic flux balance analysis and the in silico analysis of Escherichia coli k-12 gene deletions. BMC Bioinformatics. 2000;1:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-1-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faust K, et al. Metabolic path finding using RPAIR annotation. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;388:390–414. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang F, et al. Annals of Discrete Mathematics. Vol. 53. North-Holland, Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishers B.V.; 1992. The Steiner tree problem. [Google Scholar]

- Ideker T, et al. Discovering regulatory and signalling circuits in molecular interaction networks. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:S233–S240. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.suppl_1.s233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez V, Marzal A. Proceedings of the Third International Workshop on Algorithm Engineering (WAE 1999) Vol. 1668. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer; 1999. Computing the k shortest paths: a new algorithm and an experimental comparison; pp. 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Karp R. Reducibility among combinatorial problems. In: Miller RE, Thatcher JW, editors. Complexity of Computer Computations. New York: Plenum Press; 1972. pp. 85–103. [Google Scholar]

- Kemeny JG, Snell JL. Finite Markov Chains. New York, Berlin, Heidelberg, Tokyo: Springer; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Keseler IM, et al. EcoCyc: a comprehensive view of Escherichia coli biology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D464–D470. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein P, Ravi R. A nearly best-possible approximation algorithm for node-weighted Steiner trees. J. Algorithms. 1995;19:104–115. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger CJ, et al. MetaCyc: a multiorganism database of metabolic pathways and enzymes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D438–D442. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JM, et al. Flux balance analysis in the era of metabolomics. Brief. Bioinformatics. 2006;7:140–150. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbl007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noirel J, et al. Automated extraction of meaningful pathways from quantitative proteomics data. Brief. Funct. Genomic. Proteomic. 2008;7:136–146. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/eln011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman S, et al. Metabolic pathway analysis web service (Pathway Hunter Tool at CUBIC) Bioinformatics. 2004;21:1189–1193. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopalan D, Agarwal P. Inferring pathways from gene lists using a literature-derived network of biological relationships. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:788–793. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster S, et al. Detection of elementary flux modes in biochemical networks: a promising tool for pathway analysis and metabolic engineering. TIBTECH. 1999;17:53–60. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(98)01290-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott MS, et al. Identifying regulatory subnetworks for a set of genes. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:683–692. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400110-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Matsuyama A. An approximate solution for the Steiner problem in graphs. Math. Jpn. 1980;24:573–577. [Google Scholar]

- Trinh C, et al. Elementary mode analysis: a useful metabolic pathway analysis tool for characterizing cellular metabolism. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009;81:813–826. doi: 10.1007/s00253-008-1770-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Helden J, et al. Representing and analysing molecular and cellular function using the computer. Biol. Chem. 2000;381:921–935. doi: 10.1515/BC.2000.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Helden J, et al. Ernst Schering Res Found Workshop. Vol. 38. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2002. Graph-based analysis of metabolic networks; pp. 245–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zien A, et al. Proceedings of the International Conference of Intelligent Systems Molecular Biology. La Jolla, Menlo Park, CA: The AAAI Press; 2000. Analysis of gene expression data with pathway scores; pp. 407–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.