Abstract

Motivation: Emergence of genetic data coupled to longitudinal electronic medical records (EMRs) offers the possibility of phenome-wide association scans (PheWAS) for disease–gene associations. We propose a novel method to scan phenomic data for genetic associations using International Classification of Disease (ICD9) billing codes, which are available in most EMR systems. We have developed a code translation table to automatically define 776 different disease populations and their controls using prevalent ICD9 codes derived from EMR data. As a proof of concept of this algorithm, we genotyped the first 6005 European–Americans accrued into BioVU, Vanderbilt's DNA biobank, at five single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with previously reported disease associations: atrial fibrillation, Crohn's disease, carotid artery stenosis, coronary artery disease, multiple sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. The PheWAS software generated cases and control populations across all ICD9 code groups for each of these five SNPs, and disease-SNP associations were analyzed. The primary outcome of this study was replication of seven previously known SNP–disease associations for these SNPs.

Results: Four of seven known SNP–disease associations using the PheWAS algorithm were replicated with P-values between 2.8 × 10−6 and 0.011. The PheWAS algorithm also identified 19 previously unknown statistical associations between these SNPs and diseases at P < 0.01. This study indicates that PheWAS analysis is a feasible method to investigate SNP–disease associations. Further evaluation is needed to determine the validity of these associations and the appropriate statistical thresholds for clinical significance.

Availability:The PheWAS software and code translation table are freely available at http://knowledgemap.mc.vanderbilt.edu/research.

Contact: josh.denny@vanderbilt.edu

1 INTRODUCTION

Numerous genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have been performed using disease-specific definitions to identify novel genetic associations for many diseases (Hindorff et al., 2009). These GWAS typically derive their cases and controls from clinical trials, observational cohorts and, more recently, electronic medical record (EMR) systems. Several GWASs have successfully investigated multiple phenotypes using a single cohort of genotyped samples (Benjamin et al., 2007; Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium, 2007). The growth of available genomic data, some of which is linked to rich phenotypic data such as that which is available in EMR systems, suggests it would be possible to perform a ‘reverse GWAS’—determining, for a given genotype, the range of associated clinical phenotypes. The ability to conduct a true phenome-wide scan in an unbiased way can ultimately become a path to discover new genetic associations, gain insights into disease mechanisms and determine whether polymorphisms or variants exist, which confer broad susceptibility to multiple diseases across the phenome. While the concept of a phenome-wide scan is not new (Ghebranious et al., 2007; Masys et al., 2009; Bilder et al., 2009; Jones et al., 2005), to our knowledge methodology to perform such a scan in a systematic, high-throughput and reproducible fashion has not been developed. In this article, we present an algorithm to perform an initial ‘phenome-wide association scans (PheWAS)’, or phenome-wide association study. This adaptation uses readily available billing codes to replicate several known genotype–phenotype associations and suggests novel possible associations.

Deployment of EMR systems for routine clinical practice has improved the quality of patient care, reduced cost and has provided a longitudinal record of care available for clinical and translational research. Typical EMR systems contain diverse data sources, including billing data, laboratory and imaging results, medication records and clinical documentation. These data have proven useful for applied clinical research studies (Benson et al., 2009; Denny et al., 2008; Hansen et al., 2007) and for phenotyping in focused genomic studies (Manolio, 2009). EMR data have also proven useful in research studies looking across many phenotypes, such as drug-adverse effect detection (Wang et al., 2009) and mining for genetic overlaps among diseases (Rzhetsky et al., 2007).

Research involving EMR systems often involves processing both structured (e.g. billing codes) and unstructured data (e.g. clinical documentation generated by physicians). In the USA, most clinical encounters generate International Classification of Disease (ICD), version 9-CM, codes as a mechanism for billing for a given procedure, test or clinical visit. The ICD9 coding system contains over 14 000 disease codes grouped into a multi-level hierarchy of codes. These codes are ubiquitously available in hospital systems and have been successfully used for many types of research (Herzig et al., 2009; Kiyota et al., 2004; Klompas et al., 2008). Billing codes and structured laboratory data can be combined with natural language processing algorithms to extract information from unstructured clinical documentation to gain greater understanding of an individual's phenotype.

To enhance the power of EMR systems for genetic research, some institutions are linking EMR records to DNA biorepositories. EMR-linked biorepositories, such as BioVU, the Vanderbilt DNA databank (Roden et al., 2008), offer the advantages of scale, cost efficiency and detailed, longitudinal information produced as a byproduct of healthcare. Many of these biobanks, including Vanderbilt's, accrue patients in a disease-neutral fashion, a prerequisite for ultimately conducting an unbiased, comprehensive phenome-wide scan. While the relevance of these resources for genetic research is currently being explored, the potential of EMR use to explore the range of human disease for genetic research has been largely untapped.

In this article, we used custom groupings of ICD9 billing codes to approximate the clinical disease phenome. As a proof of concept and test of the algorithm, we present results on five initial single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) studied in an EMR population. Our method is implemented in a freely downloadable software program.

2 METHODS

2.1 Population and genotyping

BioVU accrues DNA samples extracted from blood remaining from routine clinical testing after they have been retained for 3 days and are scheduled to be discarded. A full description of this resource and its associated ethical, privacy and other protections has been published elsewhere (Roden et al., 2008). All patients age ≥18 years with an outpatient laboratory draw, who have a signed consent to treatment form, and that have not made a formal indication to opt-out are potential inclusions in BioVU. The resource is linked to a de-identified version of the EMR called the synthetic derivative (Roden et al., 2008). As of January 18, 2010, the resource included 75 769 DNA samples.

The study population consisted of the first ∼6000 European–Americans accrued into BioVU. The only selection criteria were that they met the general conditions for eligibility for BioVU; no clinical inclusion or exclusion criteria were applied. In the current analysis, we selected five SNPs with previously known disease associations: rs1333049 [coronary artery disease (CAD) and carotid artery stenosis (CAS)], rs2200733 [atrial fibrillation (AF)], rs3135388 [multiple sclerosis (MS) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)], rs6457620 [rheumatoid arthritis (RA)], and rs17234657 [Crohn's disease (CD)]. (Some other potential associations exist for some SNPs, such as progression of carotid atherosclerosis and rs1333049, but are not represented well through ICD9 codes.) The primary outcome of this study was identification of the prior statistical associations with MS, CD, AF, CAD, SLE, CAS and RA.

Genotyping was conducted by the Vanderbilt DNA Resources Core using the mid-throughput Sequenom® genotyping platform (rs1333049, rs3135388 and rs17234657; genotyping efficiency 98.4–100%), which is based on a single base primer extension reaction coupled with mass spectrometry, or using a TaqMan assay (rs6457620 and rs2200733; genotyping efficiency 99.4% and 99.0%, respectively). Quality control procedures included examination of marker and sample genotyping efficiency, allele frequency calculations and tests of Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium.

2.2 Development of ICD9 translation file

The ICD9 coding system describes diseases, signs and symptoms, injuries, poisonings, procedures and screening codes. Disease or symptom codes consist of a three-digit number (termed a ‘category’) followed, in most cases, by one or two additional specifying digits. For example, the three-digit code ‘427’ specifies cardiac arrhythmias and further digits are added to specify the type of arrhythmias, such as ‘AF’ (427.31). In most cases, physicians are required to specify codes to the fourth or fifth digit to bill the patient's insurance, although some diseases lack further specification (e.g. 042, human immunodeficiency virus). Some diseases of common etiologies cover multiple ICD9 categories based on acute and chronic effects, the anatomical areas affected or the disease severity and associated other events. ICD9 categories are further grouped hierarchically into sections and chapters.

Since the ICD9 terminology was designed primarily for billing and administrative functions, we developed custom ‘case groups’ of ICD9 codes to better allow for large-scale genomic research involving ICD9 codes. In general, we used the existing three-digit categories as a guide in designing our case groups. We performed one of several functions on the original ICD9 terminology: (i) we combined three-digit codes that represented common etiologies [e.g. creating a single ‘tuberculosis’ code group from 010 to 018 (primary tuberculosis), 137 (late effects of tuberculosis) and 647.3 (tuberculosis complicating the peripartum period)]; (ii) for clinically distinct phenotypes that are combined in a single three-digit code, we divided the existing ICD9 classification (by adding a fourth digit), such as Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes (both part of code ICD9 category 250); and (iii) we marked as ‘ignorable’ other ICD9 codes that were unlikely to be useful in a genetic context, such as contamination with foreign objects, non-specific signs and symptoms [e.g. 790.6 (other abnormal blood chemistry)], non-specific laboratory results, elective abortions and iatrogenic complications of medical care. There were 395 fully specified diagnosis-related ICD9 codes ignored from the analysis. When combining ICD9 codes from disparate parts of the code groupings (e.g. tuberculosis above contains codes in the ICD9 chapters ‘infectious and parasitic diseases’ and ‘complications of pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium’), we chose the case group number most closely related to the etiology of the disease (e.g. we grouped all tuberculosis ICD9 codes under ‘010’ in the ‘infectious and parasitic diseases’ chapter of ICD9 codes).

In addition, we used the ICD9 coding system to generate comparison groups (‘controls’) for all case groups, which included all patients that did not have a prevalent ICD9 code belonging to a specified list of disease exclusions defined for each case group. The exclusions for most diseases closely followed the existing section groupings in the ICD9 hierarchy, which groups related conditions. Control groups for CD, for instance, excluded CD, ulcerative colitis and several other related gastrointestinal complaints. Similarly, control groups for myocardial infarction excluded patients with myocardial infarctions, as well as angina and other evidence of ischemic heart disease. There are 105 unique control exclusions groups. The custom ICD9 case and exclusion groupings are available from http://knowledgemap.mc.vanderbilt.edu/research.

2.3 PheWAS analysis

All distinct ICD9 billing codes from each of the individuals' records were captured and translated into corresponding case groupings. For our purposes, a ‘case’ is a record that has a single, valid ICD9 code that maps to PheWAS case group. Other individuals were marked as ‘controls’ for a given case if they did not have any ICD9 codes belonging to the exclusion code grouping corresponding for that case. The PheWAS algorithm, then calculates case and control genotype distributions and calculates the χ2 distribution, associated allelic P-value and allelic odds ratio (OR). For those χ2 distributions in which observed cell counts fell below five, Fisher's exact test was used to calculate the P-value using the R statistical package (http://www.r-project.org/). Since many phenotypes, even after ICD9 code groupings, occur rarely, we selected only those that occurred in a minimum of 25 cases (0.42% of genotyped patients) as a threshold of clinical interest.

After the initial study, we conducted a failure analysis on the previously associated phenotypes that did not replicate using the PheWAS method. To investigate these further, we performed a physician chart review on all individuals with SLE and CAS by PheWAS code groups and analyzed the electrocardiograms of all patients with ICD9 codes indicative of AF. Our gold-standard definition of SLE required that a treating physician document an SLE diagnosis and immunosuppressive treatment via a clinical note or problem list. True positive cases of CAS required presence of carotid duplex sonography, traditional angiography, computed tomography angiography or magnetic resonance angiography demonstrating hemodynamically significant stenosis of the common or internal carotid artery. We assessed AF cases by processing all electrocardiograms using a previously validated natural language processing algorithm (Denny et al., 2005).

2.4 Implementation

The algorithm is implemented as a PERL program. This program takes as its inputs a list of ICD9 codes for each individual, the race/ethnicity of the individual and the genotypes for the given SNPs. Each input file is expected as an entity-attribute-value tab-delimited file. The ICD9 code translation file is another input into the program. It is a tab-delimited text document and can be customized to meet an individual project's needs.

The program converts fully specified ICD9 codes into diagnostic code groups and finds associated controls for each. Invalid ICD9 codes are ignored during the process, as are any codes marked as ignorable in the code translation file. The output includes both Microsoft® Excel spreadsheets and tab-delimited text files summarizing the number of cases and controls for each diagnostic group, χ2 test statistic, P-value, allelic OR and Bonferroni level of significance. Another output file lists all SNP–disease associations achieving significance above a user-set threshold. The program is available free of charge from http://knowledgemap.mc.vanderbilt.edu/research.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Demographics

Table 1 presents the demographic data of our cohort of 6005 European–American individuals. These individuals had 220 527 fully specified ICD9 diagnostic codes, representing 900 unique three-digit ICD9 code categories. These codes translated into 137 517 PheWAS code groups representing 733 distinct code groups. The most common specific diagnostic codes were hypertension (2877 patients), disorders of lipid metabolism (1989 patients) and unspecified anemias (1776 patients).

Table 1.

Demographics of those studied

| Attribute | Value, median (interquartile range) |

|---|---|

| Age | 57 (44–68) |

| Female (%) | 55.9 |

| Total fully specified ICD9 codes | 56 (23–134) |

| Distinct fully specified ICD9 codes | 23 (11–48) |

| Distinct ICD9 three-digit codes | 17 (9–32) |

| Distinct PheWAS code groups | 17 (8–32) |

| Years of follow-up (IQR) | 4 (2–9) |

3.2 Previously known SNP–disease associations

Table 2 presents the previously known SNP–disease associations and their ORs and significance in this analysis. Of seven previously reported SNP–disease associations investigated in this study, four (MS, CD, CAD and RA) replicated in this study at P < 0.02. Three previously reported SNP–disease associations (CAS, AF and SLE) did not replicate in this study. Given our case and control counts based on ICD9 codes, each was adequately powered (>90%) to detect a difference at P < 0.05. To achieve 80% power, we needed 90 cases of SLE, 387 cases of AF and 223 cases of CAS.

Table 2.

Diseases previously associated with the five SNP studied and current PheWAS ORs

| SNP | Gene/region | Disease | Cases | Previous OR | PheWAS P-value | PheWAS OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs3135388 | DRB1*1501 | MS | 89 | 1.99a | 2.77 × 10−6 | 2.24 (1.56–3.16) |

| SLE | 141 | 2.06b | 0.51 | 1.13 (0.79–1.58) | ||

| rs17234657 | Chr. 5 | CD | 200 | 1.54c | 0.00080 | 1.57 (1.19–2.04) |

| rs2200733 | Chr. 4q25 | AF and flutter | 606 | 1.75d | 0.14 | 1.15 (0.95–1.39) |

| rs1333049 | Chr. 9p21 | CAD | 1181 | 1.20–1.47e | 0.011 | 1.13 (1.03–1.23) |

| Carotid atherosclerosis | 333 | 1.46f | 0.82 | 0.98 (0.84–1.15) | ||

| rs6457620 | Chr. 6 | RAg | 392 | 2.36c | 0.0002 | 1.35 (1.15–1.58) |

3.3 PheWAS results for five SNPs

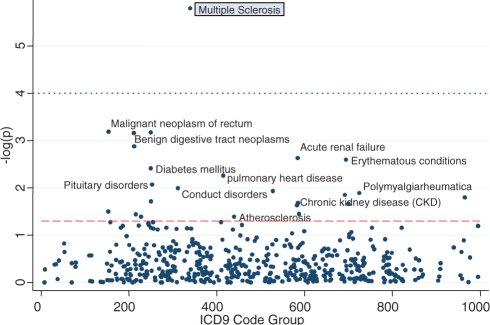

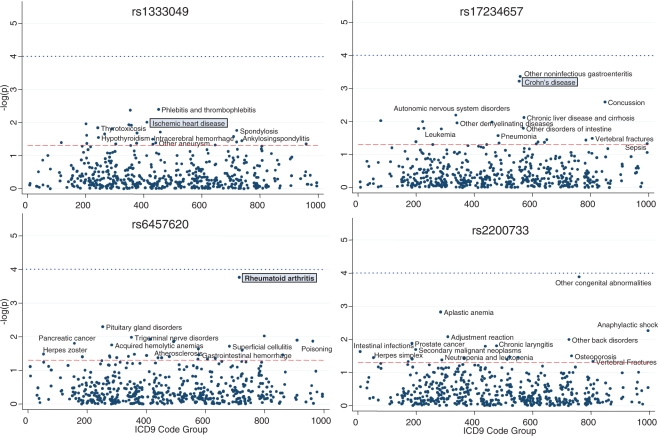

Figure 1 presents the PheWAS results for the rs3135388, which has been reported to be associated with MS and SLE. In the PheWAS analysis, it was strongly associated with MS, surviving Bonferroni correction (P = 1.0 × 10−4), but not with SLE (P = 0.51). Twenty-two other diseases were also associated at P < 0.05, as labeled in the figure. Figure 2 presents the PheWAS results for the other four SNPs. In three of the four SNPs (rs6457620, rs17234657 and rs1333049), the PheWAS replicated a known prior disease association, as indicated by the diseases highlighted by gray boxes. As with rs3135388, each of these SNPs contains a number of other possible disease associations with P < 0.05, as shown in Figure 2.

Fig. 1.

Phenome-wide scan for association with rs3135388. MS is replicated from prior analyses. The dashed line represents the P = 0.05; the dotted line represents the Bonferroni correction.

Fig. 2.

Phenome-wide scan for association for four additional SNPs with known disease-SNP associations. The boxed diseases represent associations replicated from prior GWAS analyses. The dashed line represents the P = 0.05; the dotted line represents the Bonferroni correction.

Table 3 presents all SNP–disease associations with P < 0.01 (an arbitrary cutoff) that to our knowledge have not been previously reported. A number of other possible autoimmune conditions were associated with rs3135388 and rs2200733, including eczema, aplastic anemic and psoriasis.

Table 3.

Potential SNP–disease associations discovered through PheWAS algorithm

| SNP | Disease/syndrome | N | OR | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs17234657 | Non-infectious gastroenteritis and colitis | 389 | 1.42 (1.16–1.73) | 5.3 × 10−4 |

| rs3135388 | Cancer of rectum and anus | 107 | 1.76 (1.24–2.45) | 8.2 × 10−4 |

| rs2200733 | Unspecified congenital anomalies | 44 | 2.56 (1.48–4.29) | 2.6 × 10−4 |

| rs17234657 | Autonomic nervous system disorder | 100 | 0.46 (0.24–0.82) | 8.9 × 10−3 |

| rs3135388 | Diabetes mellitus | 1238 | 0.82 (0.71–0.94) | 4.3 × 10−3 |

| rs3135388 | Benign neoplasm of other parts of digestive system | 585 | 1.33 (1.12–1.57) | 9.4 × 10−4 |

| rs2200733 | Aplastic anemia | 194 | 0.49 (0.30–0.77) | 2.0 × 10−3 |

| rs6457620 | Disorders of the pituitary gland | 101 | 1.52 (1.12–2.06) | 6.3 × 10−3 |

| rs3135388 | Benign neoplasm of respiratory and intrathoracic organs | 62 | 1.96 (1.24–3.02) | 2.1 × 10−3 |

| rs3135388 | Conduct disorders | 32 | 2.08 (1.10–3.74) | 1.0 × 10−2 |

| rs3135388 | Acute renal failure | 580 | 0.74 (0.61–0.90) | 2.8 × 10−3 |

| rs17234657 | Concussion | 70 | 1.85 (1.19–2.81) | 3.9 × 10−3 |

| rs3135388 | Erythematous conditions | 206 | 1.47 (1.13–1.90) | 3.3 × 10−3 |

| rs1333049 | Phlebitis and thrombophlebitis | 188 | 1.35 (1.09–1.68) | 4.7 × 10−3 |

| rs17234657 | Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis | 421 | 0.73 (0.57–0.92) | 8.9 × 10−3 |

| RS2200733 | Anaphylactic shock and angioedema | 244 | 1.44 (1.10–1.87) | 7.0 × 10−3 |

| RS1333049 | Mononeuritis of upper limb and mononeuritis multiplex | 243 | 1.30 (1.08–1.57) | 4.9 × 10−3 |

| RS3135388 | Pulmonary heart disease | 350 | 0.71 (0.54–0.91) | 6.6 × 10−3 |

| RS2200733 | Adjustment reaction | 347 | 0.68 (0.50–0.91) | 1.0 × 10−3 |

The chart review of SLE PheWAS cases demonstrated that only 95 individuals (67% of the 141 cases by billing codes) had documented or probable SLE as indicated by their treating physicians; the other records contained SLE ICD9 codes as reasons for ordering tests or hypothetical diagnoses that were later dismissed. Similarly, only 280 individuals (84% of the 333 cases) with CAS billing codes had objective evidence of CAS. Of the 606 patients with an AF ICD9 code, only 148 had definite electrocardiographic evidence of AF.

4 DISCUSSION

We present an algorithm to facilitate the performance of phenome-wide associated studies to detect disease–gene associations using ICD9 billing codes. This proof of concept study applied this algorithm to five SNPs with seven known disease associations. This study found that four of these previously known SNP–disease associations from the literature were identified using our PheWAS algorithm, and also indicated other potential disease–gene associations not previously investigated. As the high-density genotype data becomes increasingly available, such phenome-wide scans may have great utility to both discover new genetic associations and provide greater insight to the biology underlying certain associations.

An exciting consequence of PheWAS analyses is that they, in combination with GWAS or candidate gene studies, may help elucidate new biology. For example, GWAS-identified associations with genetic variation in intergenic regions could be investigated with PheWAS to discover other potential associations. In this study, the 9p21 region identified by rs1333049 was also associated with portal thrombosis, intracranial hemorrhage and phlebitis and thrombophlebitis, possibly suggesting a common etiology related to coagulation that could be investigated with subsequent, adequately powered studies.

PheWAS analyses may also help identify potentially causative associations between disease and SNP associations discovered in disease-specific GWAS. When performing a GWAS in isolation, one may discover an association between an infection and a given SNP (such as pneumonia and rs17234657), and potentially conclude that the SNP confers susceptibility. The alternative explanation is that this SNP increases the likelihood of autoimmune diseases, and the treatment for the autoimmune disease (such as corticosteroids and other immunosuppressive agents) may be the causative agent.

Similar to GWAS, the current PheWAS study highlights the statistical challenges associated with analyzing high-dimensionality data. In this analysis, few disease–gene associations were significant when a Bonferroni correction was applied. However, there are several reasons to suggest that a Bonferroni correction is too conservative. Unlike GWAS, in which nearly every individual will have a genotype value for that SNP, and thus its statistical power is limited primarily by the minor allele frequency and genetic effect size (i.e. OR), PheWAS is limited by these factors and the prevalence of the disease in the population, which is often <5% of the population. Thus, for most diseases, it may be unreasonable to expect P-values as extreme as seen in GWAS with similar population sizes. Indeed, several prior known gene-disease associations in this study had P-values between 2.8 × 10−6 and 0.011. Furthermore, many diseases are associated with each other in much the same was as SNPs may be in linkage disequilibrium with each other. For example, CD and ‘non-infectious gastroenteritis’ (both associated with rs17234657) not only represent similar conditions but often referred to the same individuals (72% of those with ‘non-infectious gastroenteritis’ had both conditions). These collocations of disease reduce the hypothesis space and lend greater strength to the validity of discovered associations. Like GWAS, the true significance level of clinical and genetic interest will need to be experimentally determined with future study.

While the associations in this study were often weak due to the small sample sizes for individual disease codes, the power of these data will only increase. As more genetic data is deposited, as is policy, into the BioVU resource for reuse, the ability to detect true signals with sufficient statistical power even for rare diseases will be enhanced. Furthermore, the broad availability of ICD9 codes permits easy portability to other institutions and offers the potential of cross-institution application.

This PheWAS study did not replicate three of the seven previously known SNP–disease associations. Our review of these cases revealed that each of these three ICD9 code groups contained a number of false positives in which billing codes were recorded as a hypothetical reason for a test. Repeating the study using only true positive cases revealed that AF (OR 1.51; P = 0.015) and SLE (OR 1.42; P = 0.039) both replicated the previously reported associations, and CAS (OR 1.32, P = 0.12) trended in a similar direction as previously noted. Further work to refine the PheWAS case algorithms may improve performance beyond using prevalent ICD9 codes. Incorporation of laboratory data, natural language processing and machine learning algorithms may improve case accuracy.

Limitations caution interpretation of this initial feasibility study. This study was performed in a single institution with five SNPs. Other institutions may have different coding practices, which can affect the ability to replicate these results if the PheWAS is undertaken at another institution. To define phenotypes in a high-throughput fashion, we used groupings of ICD9 billing codes, which are known to have substantial limitations relative to both sensitivity and specificity of given disease. Certain ICD9 codes, such as MS, are likely very specific and sensitive, whereas more general codes such as ‘hypertension’ represent a very heterogeneous disease phenotype and may be billed by physicians with less sensitivity and specificity. Our experiences locally and as part of the eMERGE consortium (http://www.gwas.net) have demonstrated that combining billing codes, laboratory data, medication records and natural language processing of clinical documents provides a better approach to phenotype identification, often achieving positive predictive values ≥95%. The PheWAS code groupings were designed by a single clinician with limited external review, with a strong bias toward the existing ICD9 organization. Using the existing framework of the ICD9 coding schema allowed for rapid generation and quick interpretation from a known resource; however, it is likely suboptimal for some diseases and groupings. Furthermore, the coding schema can be easily revised for different analyses. By publishing this resource as open-source, we hope for community researchers to refine this schema into a more robust, etiologic lexicon of disease phenotypes. Both the current case and control groupings lack the specificity that come with carefully curated manual case definitions, and lack the ability to measure disease severity. Until larger genotyped sample sizes are obtained, rare diseases will likely contain insignificant numbers of cases, limiting the range of diseases that can be studied. The current algorithm also does not consider important risk factors such as age, gender or family history. These methods provide a mechanism that will serve to efficiently highlight avenues for further study; they are not intended to be conclusive in making associations by themselves. Finally, this PheWAS analysis requires linkage of genetic data with available EMR data. While many genotyped cohorts currently lack association with clinical data, we expect the growing use of EMR-linked biobanks will make such analyses increasingly possible.

The current PheWAS work demonstrates the possibility of a phenome-wide scan to discover genetic associations with a single locus at a time. Future research should investigate more accurate methods of automatic phenotypic determination and extensions to include other phenotypic traits, such as laboratory results and treatment efficacy. Another logical extension of this work is coupling of PheWAS analysis with GWAS analysis. Such an analysis leads to increasing statistical challenges beyond those already posed by existing GWAS and now PheWAS. However, growing extant genotyped records in EMR biobanks from case–control studies make such a genome–phenome wide analysis increasingly feasible.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Vanderbilt DNA Resources Core houses the DNA samples and also performed the genotyping for this work. The Vanderbilt University Center for Human Genetics Research, Computational Genomics Core provided computational and analytical support for this work. The authors would like to thank Veida Elliott and Raquel Maddox for their contributions to this effort.

Funding: Vanderbilt CTSA grant 1 UL1 RR024975 from National Center for Research Resources/National Institutes of Health and U01 HG004603 from National Human Genome Research Institute.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Benjamin EJ, et al. Genome-wide association with select biomarker traits in the Framingham Heart Study. BMC Med. Genet. 2007;8(Suppl. 1):S11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-8-S1-S11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson L, et al. Trends in the diagnosis of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents: 1999–2007. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e153–158. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilder RM, et al. Phenomics: the systematic study of phenotypes on a genome-wide scale. Neuroscience. 2009;164:30–42. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denny JC, et al. Increased hospital mortality in patients with bedside hippus. Am. J. Med. 2008;121:239–245. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denny JC, et al. Identifying UMLS concepts from ECG impressions using knowledgemap. AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc. 2005:196–200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghebranious N, et al. Clinical phenome scanning. Per. Med. 2007;4:175–182. doi: 10.2217/17410541.4.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudbjartsson DF, et al. Variants conferring risk of atrial fibrillation on chromosome 4q25. Nature. 2007;448:353–357. doi: 10.1038/nature06007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafler DA, et al. Risk alleles for multiple sclerosis identified by a genome-wide study. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:851–862. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen ML, et al. Underdiagnosis of hypertension in children and adoles-cents. JAMA. 2007;298:874–879. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.8.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzig SJ, et al. Acid-suppressive medication use and the risk for hospital-acquired pneumonia. JAMA. 2009;301:2120–2128. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindorff LA, et al. Potential etiologic and functional implications of genome-wide association loci for human diseases and traits. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:9362–9367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903103106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R, et al. The search for genenotype/phenotype associations and the phenome scan. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2005;19:264–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2005.00664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyota Y, et al. Accuracy of medicare claims-based diagnosis of acute myo-cardial infarction: estimating positive predictive value on the basis of review of hospital records. Am. Heart J. 2004;148:99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klompas M, et al. Automated identification of acute hepatitis B using electronic medical record data to facilitate public health surveillance. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2626. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manolio TA. Collaborative genome-wide association studies of diverse diseases: programs of the NHGRI's office of population genomics. Pharmacogenomics. 2009;10:235–241. doi: 10.2217/14622416.10.2.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masys DR, et al. AMIA Summit on Translational Bioinformatics, 16 March, 2009. San Francisco, CA: 2009. GWAS to PheWAS: using EMR-derived phenotypes for discovery of relationships between genotypes and clinical events. [Google Scholar]

- Pan C, et al. Molecular analysis of HLA-DRB1 allelic associations with systemic lupus erythematous and lupus nephritis in Taiwan. Lupus. 2009;18:698–704. doi: 10.1177/0961203308101955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roden DM, et al. Development of a large-scale de-identified DNA biobank to enable personalized medicine. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008;84:362–369. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rzhetsky A, et al. Probing genetic overlap among complex human phenotypes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:11694–11699. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704820104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samani NJ, et al. Large scale association analysis of novel genetic loci for coronary artery disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2009;29:774–780. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.181388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, et al. Active computerized pharmacovigilance using natural language processing, statistics, and electronic health records: a feasibility study. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2009;16:328–337. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M3028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium. Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature. 2007;447:661–678. doi: 10.1038/nature05911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye S, et al. Association of genetic variation on Chromosome 9p21 with susceptibility and progression of atherosclerosis: a population-based, prospective study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008;52:378–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.11.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]