Abstract

Motivation: The ultimate goal of abbreviation management is to disambiguate every occurrence of an abbreviation into its expanded form (concept or sense). To collect expanded forms for abbreviations, previous studies have recognized abbreviations and their expanded forms in parenthetical expressions of bio-medical texts. However, expanded forms extracted by abbreviation recognition are mixtures of concepts/senses and their term variations. Consequently, a list of expanded forms should be structured into a sense inventory, which provides possible concepts or senses for abbreviation disambiguation.

Results: A sense inventory is a key to robust management of abbreviations. Therefore, we present a supervised approach for clustering expanded forms. The experimental result reports 0.915 F1 score in clustering expanded forms. We then investigate the possibility of conflicts of protein and gene names with abbreviations. Finally, an experiment of abbreviation disambiguation on the sense inventory yielded 0.984 accuracy and 0.986 F1 score using the dataset obtained from MEDLINE abstracts.

Availability: The sense inventory and disambiguator of abbreviations are accessible at http://www.nactem.ac.uk/software/acromine/ and http://www.nactem.ac.uk/software/acromine_disambiguation/

Contact: okazaki@chokkan.org

1 INTRODUCTION

Abbreviations substitute for fully expanded terms (e.g. computed tomography) through the use of shortened term-forms (e.g. CT). In the bio-medical literature, abbreviations are used for various important terms including: genes, proteins, diseases and chemical names (Federiuk, 1999). Results of our experiment (Section 3.2) show that 32.0% of UniProt entries include abbreviations in description and gene name fields. Wren et al. (2005) reported that abbreviations are used more frequently than expanded forms.

Abbreviations present two major challenges to bio-medical text mining: term variation and ambiguity. We consider an information retrieval system that collects documents referring to polymerase chain reaction. Because polymerase chain reaction might be abbreviated as PCR, the system is expected to retrieve documents in which PCR appears. At the same time, abbreviations are ambiguous: the same abbreviation might refer to different concepts (Ananiadou et al., 2006; Erhardt et al., 2006). Because PCR means other than polymerase chain reaction, the system should be able to perform abbreviation disambiguation—to judge whether an occurrence of PCR actually means polymerase chain reaction or not (McCray and Tse, 2003; Sehgal and Srinivasan, 2006). In general, abbreviations are much more ambiguous than ordinary terms. Liu et al. (2002b) report that 81.2% of abbreviations in Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) were ambiguous, with an average of 16.6 senses.

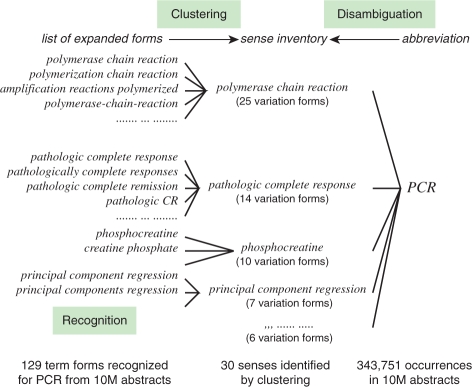

Figure 1 presents problems of term variation and ambiguity of abbreviations. In all, 129 distinct expanded forms were extracted for the abbreviation PCR from all MEDLINE abstracts, including polymerase chain reaction, polymerization chain reaction and amplification reactions polymerized. Abbreviation recognition is a task of collecting expanded forms for abbreviations. It has been explored extensively using various approaches: through the use of heuristics and/or scoring rules (Adar, 2004; Park and Byrd, 2001; Pustejovsky et al., 2001; Schwartz and Hearst, 2003), machine learning (Chang and Schütze, 2006; Nadeau and Turney, 2005; Okazaki et al., 2008) and co-occurrence statistics (Liu and Friedman, 2003; Okazaki and Ananiadou, 2006; Zhou et al., 2006). The 129 expanded forms in Figure 1 were obtained using the abbreviation recognition method (Okazaki and Ananiadou, 2006), which is based on co-occurrence statistics. As depicted in Figure 1, expanded forms extracted by abbreviation recognition are mixtures of concepts/senses and their term variations. The abbreviation PCR has 129 expanded forms that can be consolidated to 30 senses (e.g. polymerase chain reaction, pathologic complete response and phosphocreatine). In general, a single sense has more than one surface form (i.e. variant). The sense of pathologic complete response, for example, was actually described in MEDLINE abstracts by one of the 14 variation forms (e.g. pathologic complete response and pathologically complete responses). Clustering of expanded forms into a set of distinct senses, thereby creating a sense inventory for a given abbreviation, is a crucial step towards abbreviation disambiguation. Abbreviation disambiguation has been studied less intensively than abbreviation recognition, partly because clustering for creating sense inventories for numerous pairs of abbreviations and their surface expanded forms.

Fig. 1.

Term variation and ambiguity of the abbreviation PCR.

As described in this article, we first formalize the task of creating sense inventories as an independent task of clustering in which similar expanded forms for an abbreviation are gathered into a cluster (sense). Because the quality of sense inventories has a significant effect on the performance of abbreviation disambiguation, we developed a new supervised method for clustering expanded forms. We constructed a dataset for the method and measured its performance. The effect of clustering on abbreviation disambiguation was also evaluated quantitatively. The main contributions of this article are 3-fold.

A sense inventory is key to robust management of abbreviations because it provides target senses for disambiguation that correspond to biomedical entities and concepts. Therefore, we present a supervised approach for clustering expanded forms, and evaluate the quality of the sense inventory. The experimental result reports a 0.915 F1 score in clustering expanded forms.

We investigate the possibility of conflict of protein and gene names with abbreviations to estimate the importance of abbreviation disambiguation. Results showed that 32.0% of UniProt records include abbreviation terms and that 16.7% of records have ambiguous abbreviations with multiple definitions.

We conduct an experiment of abbreviation disambiguation on the sense inventory whose quality was demonstrated by the Contribution (i). The proposed system achieves 0.984 accuracy on a dataset obtained from all of MEDLINE.

2 METHODS

In terms of abbreviation disambiguation, it is important to draw a clear distinction between local and global abbreviations (Gaudan et al., 2005). By convention, a local abbreviation accompanies its expanded form at its first appearance in the document. Because abbreviation definitions are mostly consistent within a document, i.e. one-sense-per-discourse assumption (Yarowsky, 1995), we can identify the definitions of local abbreviation by reusing methods for abbreviation recognition (Yu et al., 2006). In contrast, global abbreviations appear in documents without the expanded form explicitly stated. It is necessary to estimate the definitions of undefined global abbreviations based on their contexts in documents. This task is similar to word sense disambiguation (WSD) in natural language processing, where a sense of an ambiguous term is chosen from several predefined senses. The remainder of this article will specifically describe disambiguation of global abbreviations in the MEDLINE database.

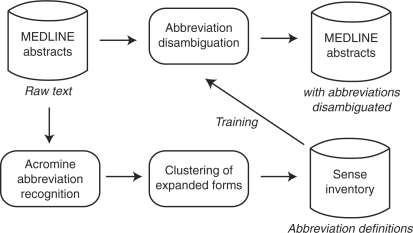

Figure 2 shows the work flow of abbreviation management. The system first extracts abbreviation definitions from MEDLINE abstracts. Because expanded forms include variations (e.g. polymerase chain reaction and polymerization chain reaction for PCR), we apply a clustering method to compile a sense inventory. Using a collection of sentences including abbreviation definitions, we train a classifier for each abbreviation that predicts the sense for an occurrence of the abbreviation. Finally, the system predicts senses of global abbreviations in MEDLINE abstracts.

Fig. 2.

Work flow of the proposed system.

2.1 Collecting abbreviation definitions from MEDLINE

The first step for abbreviation disambiguation is to collect possible expanded forms for abbreviations. We used a state-of-the-art method for recognizing abbreviation definitions in MEDLINE abstracts (Okazaki and Ananiadou, 2006). The algorithm assumes parenthetical expressions to introduce abbreviation definitions in the following format:

| (1) |

For each inner expression of a parenthetical expression, the algorithm enumerates candidates of expanded forms that begin with any non-function word (e.g., a, and, of) and end with any word immediately before the parenthetical expression.

To choose correct expanded forms for each abbreviation a, the algorithm computes a score LHa(c) for a candidate of expanded form c,

| (2) |

In Equation (2), the following variables are used: a is an abbreviation; c is a candidate of expanded form for the abbreviation a; freq(a, c) denotes the co-occurrence frequency of the candidate c with the abbreviation a; and Tc is a set of nested candidates, each of which consists of a preceding word followed by the candidate c. We compile a list of candidates of expanded forms sorted in the descending order of their scores for each abbreviation. The algorithm extracts candidates out of the sorted list one by one. An expanded form is considered valid if all of the following are true: it has a score >2.0; the words in the expanded form can be rearranged so that all alphanumeric letters in the abbreviation appear in the same order; and it is not nested or an expansion of the previously chosen expanded forms.

2.2 Merging term variations in abbreviation definitions

The list of abbreviation definitions elucidates the phenomena of term variation and ambiguity. For instance, the abbreviation CT stands for various concepts and entities such as computed tomography, calcitonin and cholera toxin, but it also has various forms including: computed tomography, computed tomographic, computerized tomography and computerised tomography. To compile a sense inventory of abbreviations from a list of expanded forms, we must merge term variations referring to the same concept into a single representative form. We formalize this task as a clustering problem in which similar expanded forms constitute a cluster.

The key to success in clustering lies in the accuracy of the distance (similarity) measure between expanded forms. Various similarity measures including cosine similarity, Levenshtein distance (Levenshtein, 1966), Jaro–Winkler similarity (Winkler, 1999) and SoftTFIDF (Cohen et al., 2003) have been applied to the term clustering. Nevertheless, we are unsure of the best choice, combination and threshold of these measures for use in recognizing term variations. Therefore, we use a machine learning technique to acquire a similarity metric by combining various features. More specifically, we build a binary classifier that, when given two terms s and t, decides whether the terms s and t present a term variation (r = +1) or not (r = −1).

Although the support vector machine (SVM) is a popular method for binary classification, we model the conditional probability P(r|s, t) with the logistic regression, hoping that the probability P(r|s, t) reflects the distance between s and t. The probability distribution P(r|s, t) is given as

| (3) |

In Equation (3), F = {f1,…, fK} denotes a vector of feature functions: K is the number of feature functions; and w = {w1,…, wK} presents a weight vector of the feature functions. We use the maximum a posteriori estimation to fit the feature weights w to the training set consisting of N instances, 𝒟 = ((s(1), t(1), r(1)),…, (s(N), t(N), r(N))). We minimize the objective function with the L2 norm of the weight vector w,

| (4) |

Here, the first term presents the negative of the log-likelihood of the model for the training set, ‖w‖2 denotes the L2 norm of the weight vector w and σ is a parameter to control the effect of L2 regularization. Equation (4) is minimized using the Limited-memory Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno method (Nocedal, 1980).

Table 1 presents a summary of the list of feature functions designed for the vector F(s, t) and the actual feature values computed for the string pair X-ray photoelectron spectroscopic and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Feature functions #1–#5 compute nine kinds1 of orthographic similarities of the two expanded forms x and y. Features #1–#3 measure the similarity of constituent letters in s and t with n-gram cosine similarity, normalized Levenshtein distance and Jaro–Winkler similarity. Features #4–#5 compute the similarity of constituent words2 in s and t with n-gram cosine similarity and SoftTFIDF. Feature #6 corresponds to the bias term, which adjusts the decision boundary of classification. The column ‘Weight’ in Table 1 presents the optimal feature weights tuned for the training data (Section 3.1).

Table 1.

Features for the string similarity measure

| # | Feature | Type | Description | Example | Weight (w) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Character n-gram similarity | Real | Cosine similarity of letter n-grams of terms s and t (n=1, 2, 3). | (0.954, 0.953, 0.951) | (1.037, 3.838, 9.043) |

| 2 | Normalized Levenshtein distance | Real | The minimum number of insertions, deletions and substitution operations necessary to transform one term into the other (Levenshtein, 1966), divided by the number of characters in the longer term. | 0.061 | 2.742 |

| 3 | Jaro–Winkler similarity (Winkler, 1999) | Real | This metric considers the number of shared letters and transpositions between two terms; the metric also incorporates a formula to favor two terms that match from the beginning. | 0.979 | −0.536 |

| 4 | Word n-gram similarity | Real | Cosine similarity of word n-grams of terms s and t (n=1, 2, 3). | (0.750, 0.667, 0.500) | (0.457, −2.439, 0.523) |

| 5 | SoftTFIDF (Cohen et al., 2003) | Real | This metric aligns tokens between two strings using the Jaro–Winkler similarity with threshold 0.9, and computes the sum of the similarity scores of aligned pairs; the similarity score is based on TFIDF scores. | 1.883 | 0.946 |

| 6 | Bias | Real | This feature always yields 1. | 1 | −9.340 |

Finally, we apply a hierarchical clustering algorithm (Lance and Williams, 1967) to the similarity metric. We define the distance measure d(s, t)=1 − P(+1|s, t) even though the conditional probability P(+1|s, t) does not hold the properties of distance measures. In Section 3.1, we compare single-link, complete-link, centroid and group-average clustering algorithms.

2.3 Abbreviation disambiguation as a problem of WSD

We formalize abbreviation disambiguation as the following: given an occurrence of an abbreviation x and a set of possible senses Yx = {y1, y2,…, yn} corresponding to x, choose the most suitable sense y* ∈ Yx for the abbreviation occurrence. This is a classification problem which assigns a label y* ∈ Yx that is suitable for input x. Among various supervised machine learning techniques such as naïve Bayes and SVM, this study employs maximum entropy modeling (Berger et al., 1996) for its efficiency in multi-class classification.

Table 2 presents a summary of the feature template (rules) to generate features. A rule in the table generates Boolean features that associate the sense y with observation events (uni- or bi-gram) occurring in a region (window). For example, given the sentence,

Periplakin, a member of the plakin family of proteins, has been recently characterized by complementary deoxyribonucleic acid (cDNA) cloning, and the corresponding gene,…

and the training instance of the abbreviation x in the sentence,

then the region for local features is

Six uni-gram and five bi-gram features are extracted from the region. Features for local and sentence contexts estimate an expanded form based on word occurrences around the target abbreviation, and on features for the abstract context considering the global topics in the abstract3.

Table 2.

Rules to generate features for classifiers

| Feature type | Unit | Effective region (window) |

|---|---|---|

| Neighbor context | uni | Previous and next words to the abbreviation x |

| Local context | uni, bi | Three words previous and next to the abbreviation x |

| Sentence context | uni, bi | Words in the same sentence for x |

| Abstract context | uni, bi | Words in the same abstract for x |

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

We applied the proposed methods to MEDLINE abstracts (9 635 599 abstracts as of March 2009). Abbreviation recognition (Section 2.1) recognized 467 402 distinct definitions for 68 007 abbreviations. We applied single-link clustering to the 467 402 expanded forms with the distance threshold 0.2, and obtained a sense inventory with 146 651 senses for 68 007 abbreviations4. In other words, the clustering method identified 3.19 term variations per sense. An abbreviation has 2.16 senses on average.

3.1 Clustering of expanded forms

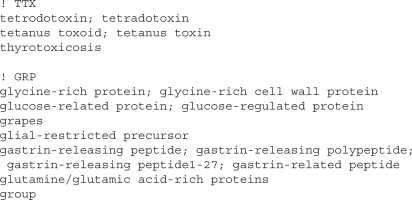

To train the similarity measure described in Section 2.2, we grouped 4158 expanded forms for 400 abbreviations that were sampled randomly from the abbreviation definitions. We asked a human expert to merge expanded forms if they refer to an almost identical concept. In this way, we obtained a dataset consisting of 2563 clusters (senses) of 4158 expanded forms for the 400 abbreviations. Figure 3 portrays an excerpt of the clusters for the abbreviation TTX and GRP: the abbreviation TTX has five expanded forms recognized; the expanded forms are grouped into three clusters.

Fig. 3.

Excerpt of the clusters of expanded forms.

Assuming inner cluster pairs of expanded forms for each abbreviation to be positive (r = +1) and assuming inter-cluster pairs to be negative (r = −1), we obtained 3678 positive and 19 296 negative instances of the training data for the similarity measure5. For example, two positive instances, 〈tetanus toxin, tetanus toxoid〉 and 〈tetradotoxin, tetrodotoxin〉, and eight negative instances (other pairs of expanded forms) are generated for TTX in Figure 3.

Table 3 reports the accuracy (A), precision (P), recall (R), and F1 (F1) scores of the similarity metric measured using the 10-fold cross validation on the training data. The row ‘Full’ shows the performance when all features described in Section 2.2 were used; the best performance (0.892 F1 score) was obtained with all features. The first half of feature sets use only the specific feature(s) for training the similarity metric. Some examples are that ‘Sim (ch)’ shows the performance when only the character n-gram similarity was used. The last half of feature sets (with prefixes ‘-’) remove the specific feature(s) from the full feature set, e.g. ‘- Sim (ch+wd)’ shows the performance when features for character and word n-gram similarity were removed. We can infer that the feature greatly contributes to the similarity metric if the performance decreases in the absence of a feature. Table 3 shows that character n-gram similarity was among the most effective features for predicting term variations. In addition, the performance reductions (ΔF1) in Table 3 suggest that other features such as the Levenshtein distance, Jaro–Winkler distance and SoftTFIDF did not contribute to the performance, subsumed by n-gram similarity features.

Table 3.

Feature contributions for the similarity metric

| Features | A | P | R | F1 | ΔF1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sim (ch) | 0.963 | 0.879 | 0.895 | 0.887 | |

| Sim (wd) | 0.937 | 0.844 | 0.747 | 0.793 | |

| Sim (ch + wd) | 0.962 | 0.877 | 0.890 | 0.884 | |

| Levenshtein | 0.939 | 0.849 | 0.754 | 0.799 | |

| Jaro–Winkler | 0.918 | 0.920 | 0.534 | 0.676 | |

| SoftTFIDF | 0.921 | 0.817 | 0.656 | 0.728 | |

| Full | 0.965 | 0.883 | 0.900 | 0.892 | |

| - Sim (ch) | 0.947 | 0.855 | 0.808 | 0.831 | −0.061 |

| - Sim (wd) | 0.965 | 0.885 | 0.898 | 0.891 | −0.001 |

| - Sim (ch+wd) | 0.950 | 0.868 | 0.810 | 0.838 | −0.054 |

| - Levenshtein | 0.965 | 0.882 | 0.898 | 0.890 | −0.002 |

| - Jaro–Winkler | 0.965 | 0.882 | 0.899 | 0.891 | −0.001 |

| - SoftTFIDF | 0.965 | 0.882 | 0.901 | 0.892 | −0.000 |

ΔF1, the difference of F1 score from the Full feature set; Sim (ch), character n-gram similarity; Sim (wd), word n-gram similarity

We examined 818 false instances of the trained similarity metric. The 442 false positives were mostly caused by accidental matches of letter/word n-grams in the expanded forms, e.g. Statement of Position and state of polarization for the abbreviation SOP. Some false positives included subtle differences of letters, e.g. adenine diphosphate and adenosine diphosphate for the abbreviation ADP. It might be difficult for the current model to handle these false positives because the model must make determinations based on similarity values (features) of several kinds. We should add more features that can explicitly capture semantic difference of words (e.g. adenine and adenosine) and morphemes (e.g. di and tri).

Out of 376 false negatives, 167 instances involved nested abbreviations. For example, EGF receptor and epithelial growth factor receptor are expanded forms of the abbreviation EGF-R, but the former expanded form includes the abbreviation EGF, which should be expanded to epithelial growth factor. We were able to remedy these false instances by substituting abbreviations recursively into expanded forms. Still, we found some tricky instances, e.g. 1-deamino-8-D-AVP and 1-deamino-[D-Arg8]-vasopressin as expanded forms of the abbreviation DDAVP; it is not straightforward to expand the substring 8-D-AVP into [D-Arg8]-vasopressin. The similarity metric could not recognize 29 instances of synonymous expanded forms, e.g. baccalaureate nursing and bachelor's degree in nursing for the abbreviation BSN. It might also be effective to incorporate a feature of a synonym dictionary.

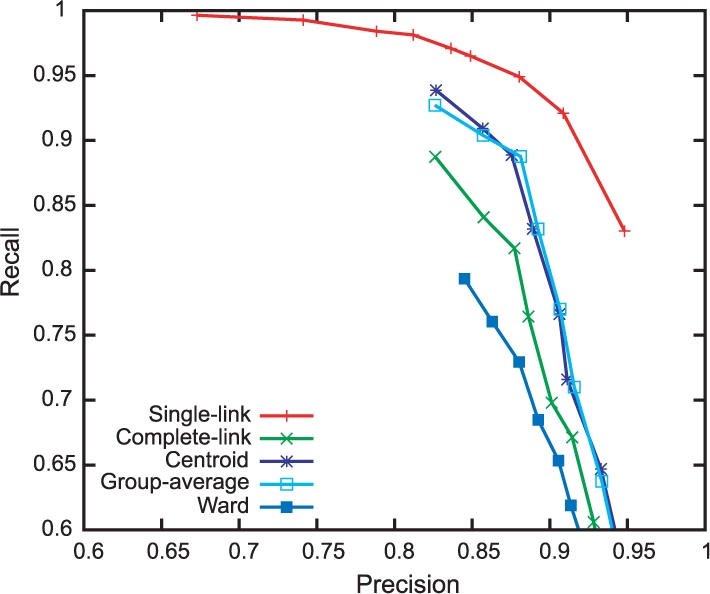

Figure 4 presents a performance comparison of clustering algorithms with different distance thresholds on the same dataset. In this evaluation, we measured pairwise precision and recall. For every pair of expanded forms, a true positive is defined as a pair of expanded forms that are correctly located in the same clusters. False positives, true negatives and false negatives are defined analogously. We drew a precision–recall curve by plotting the performance of each clustering algorithm when its distance threshold values range from 0.1 (high precision and low recall; bottom right) to 0.9 (low precision and high recall; top left).

Fig. 4.

Performance of clustering with different algorithms.

In Figure 4, the single-link algorithm obtained the peak F1 score (0.915) with distance threshold 0.2 (the second point from the right on the red locus). This parameter is equivalent of merging two expanded forms s and t only if the probability of term variation P(+1|s, t) is >0.8. We can interpret that the best parameter tightens the decision boundary from the neutral threshold of 0.5–0.2 for alleviating the chaining effect of the algorithm6. It is particularly interesting that other clustering algorithms were unable to outperform the single-link algorithm; in particular, these algorithms suffer from low recall. In these algorithms, two similar expanded forms cannot be merged solely according to their distance. For example, the complete-link algorithm refuses an expanded form that is similar to most of the expanded forms in a cluster but dissimilar to an expanded form in the cluster. Other clustering algorithms might be reluctant to form a cluster, but the single-link algorithm trusts the trained similarity measure and performs the best in this task.

3.2 Entity names conflicting with abbreviations

Some researchers have argued that gene symbols are often identical to ambiguous abbreviations (Gaudan et al., 2005; Yu et al., 2006). For example, SCT represents the official gene symbol for the human gene secretin, but it also stands for stem cell transplantation, salmon calcitonin, sacrococcygeal teratoma, etc. (Erhardt et al., 2006). How many protein and gene names actually conflict with abbreviations? To examine the importance of abbreviation disambiguation, we extracted entity names from databases and compared them with the sense inventory. We used entity names in the following resources: description (DE) and gene name (GE) fields in UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot database (as of July 7, 2009); concept names with ‘Gene or Genome’ type in UMLS (2009AA release as of April 20, 2009); and concept names with ‘Amino Acid, Peptide, or Protein’ type in UMLS. We assume a database record to have a possible conflict with an abbreviation if the record includes a name that also appears in the abbreviation list. A conflicting name is ambiguous when the sense inventory includes the name as an abbreviation with multiple senses.

Table 4 presents the number of database records including abbreviations with at least k senses in the sense inventory. The first row (k≥0) represents the total number of records in each database. Results showed that 149 537 (32.0%) out of 466 739 UniProt records include names that also appear in the abbreviation list (k≥1). Of UniProt records 77 833 (16.7%) have ambiguous abbreviations with multiple senses (k≥2); similarly, 13.2% gene names and 6.4% acid/peptide/protein names in UMLS have possible conflicts with ambiguous abbreviations (k≥2). Moreover, 4 841 (1.0%) of UniProt records are highly ambiguous with at least 30 senses in the abbreviation dictionary. These facts suggest that it is insufficient to identify gene or protein names simply by matching textual expressions with database records.

Table 4.

Number of database records including names conflicting with abbreviations with at least k senses.

| k | UniProt, n (%) | UMLS genes, n (%) | UMLS acids, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≥0 | 466 739 ( 100) | 29 194 ( 100) | 116 011 ( 100) |

| ≥1 | 149 537 (32.0) | 7525 (25.8) | 17 854 (15.4) |

| ≥2 | 77 833 (16.7) | 3852 (13.2) | 7424 ( 6.4) |

| ≥3 | 56 430 (12.1) | 2982 (10.2) | 5277 (4.5) |

| … | … | … | |

| ≥30 | 4841 (1.0) | 426 ( 1.5) | 507 ( 0.4) |

3.3 Abbreviation disambiguation

We implemented a system that resolves the definitions of abbreviations using the sense inventory. To process all MEDLINE abstracts efficiently, the WSD training and classification algorithms were implemented in C++. Furthermore, we used a grid computing environment, dividing the whole MEDLINE into sets of abstracts. A set of jobs was scattered on 21 cluster nodes, each of which runs on four Intel Xeon 5140 (2.33 GHz) processors with 8 GB main memory. It took about 6–16 h to finish 10-fold cross validation jobs on the cluster environment.

The sentences with abbreviation definitions were used as training data for abbreviation disambiguation. For each definition of an abbreviation in a sentence, we assumed the expanded form to be the correct sense for the abbreviation, and removed the expanded form from the sentence: WSD classifiers were trained to predict the ‘masked’ expanded forms of the abbreviations. We applied 10-fold cross validation to assess the system performance. The system performance is measured by accuracy, macro-averaged precision, recall and F1 measures. We compute the accuracy, precision, recall and F1 scores for each abbreviation and sense, and take averages of these scores over every abbreviation and its sense.

Table 5 shows the system performance. In this evaluation, we did not include expanded forms that are defined <40 times throughout all of MEDLINE for hastening the cross validation7; the total number of instances, abbreviations and senses in the dataset were reduced to, respectively, 5 521 074, 11 262 and 17 613 by this cut-off operation. These instances amount to 84.3% of the total (6 547 124) training instances. The proposed method using all the features in Table 2 achieved 0.984 accuracy and a 0.986 F1 score. These scores were much better than those (0.789 accuracy and 0.636 F1 score) of the baseline system (‘Majority’), which chooses the expanded form defined most frequently with the abbreviation. We also measured the performance when omitting the step for merging similar expanded forms (‘w/o clustering’). Disambiguation without clustering is much worse (0.830 F1 score). In any case, senses without clustering are of little use.

Table 5.

Performance of abbreviation disambiguation

| Features | A | P | R | F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Majority | 0.789 | 0.621 | 0.663 | 0.636 |

| Majority (w/o clustering) | 0.760 | 0.571 | 0.619 | 0.588 |

| Proposed | 0.984 | 0.992 | 0.984 | 0.986 |

| Proposed (w/o clustering) | 0.801 | 0.854 | 0.831 | 0.830 |

| +Neighbor | 0.925 | 0.961 | 0.929 | 0.934 |

| +Local | 0.952 | 0.980 | 0.955 | 0.961 |

| +Sentence | 0.967 | 0.987 | 0.967 | 0.973 |

| +Abstract | 0.982 | 0.992 | 0.983 | 0.986 |

| - Abstract | 0.968 | 0.988 | 0.968 | 0.974 |

| - Abstract - Neighbor | 0.968 | 0.988 | 0.968 | 0.974 |

| - Abstract - Local | 0.968 | 0.987 | 0.968 | 0.973 |

| - Abstract - Sentence | 0.953 | 0.980 | 0.956 | 0.962 |

The rows starting with ‘+’ present the performances only when the corresponding feature(s) are employed in the classifier. Classifiers using the neighbor contexts (‘+Neighbor’) yielded 0.929 accuracy and 0.934 F1 score. The most effective features were obtained from abstract-level contexts, achieving 0.982 accuracy and 0.986 F1 score; this closely approximates the performance using all the features. The rows starting with ‘-’ report the performances when the corresponding feature(s) are removed from the full feature set. For example, classifiers trained without using the abstract and sentence contexts (‘- Abstract - Sentence’) achieved 0.953 accuracy and 0.962 F1 score. These results were interesting in that broader contexts (e.g. abstracts and sentences) are much more useful than local contexts (e.g. neighbor words) for disambiguating abbreviations. This is consistent with the one-sense-per-discourse assumption (Yarowsky, 1995) that is common for WSD.

In Table 5, we used the clustering method (Section 3.1) to obtain the sense inventory for abbreviation disambiguation. This experimental setting has been used by the previous work (Gaudan et al., 2005), but this evaluation might be lenient in that we did not consider the influence of errors in the sense inventory. That is, if a clustering method builds a sense inventory with a smaller number of senses, the disambiguation task may become less complicated. This might lead to the situation where a disambiguator seemingly yields a good performance value only because the sense inventory is coarse, i.e. expanded forms having distinct meanings are merged. Although we have demonstrated the quality of the sense inventory in Section 3.1, we analyze the influence of errors in the sense inventory.

Table 6 reports the performance of disambiguating the 400 abbreviations for which the sense inventory was built manually in Section 3.1. The first and second rows show the disambiguation performance when we trained and evaluated disambiguation systems with the sense inventory built manually (gold-standard) and by the clustering method (automatic). The third row presents the performance when we trained a disambiguation system with the sense inventory built by the clustering method (automatic) and measured the correctness of disambiguation results on the sense clusters built manually (gold-standard). We can infer that the evaluation result of Table 5 is reasonable because the sense inventories using manual and automatic clustering show comparable performance values in Table 6. The fourth row of Table 6 shows the performance when we trained a disambiguation system without a sense inventory, i.e. to predict the original expanded forms. We employ a lenient evaluation criterion: if the disambiguation system predicts an expanded form that is different from the original but in the same cluster of the manually built sense inventory, we regard this as a correct prediction. Although this experimental setting is unrealistic, the comparison between the fourth and other rows confirms that the sense inventory has a positive effect to refine training data of abbreviation disambiguation.

Table 6.

Performance of disambiguating the 400 abbreviations

| Clustering | Evaluation | A | P | R | F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gold-standard | Gold-standard | 0.992 | 0.989 | 0.979 | 0.982 |

| Automatic | Automatic | 0.993 | 0.991 | 0.980 | 0.983 |

| Automatic | Gold-standard | 0.993 | 0.991 | 0.978 | 0.982 |

| No | Gold-standard | 0.984 | 0.980 | 0.963 | 0.968 |

4 RELATED WORK

Liu et al. (2001, 2002a) used UMLS Metathesaurus as a sense inventory for abbreviation disambiguation. Pakhomov et al. (2005) prepared a sense inventory for abbreviation disambiguation by annotating senses of abbreviations of eight kinds in clinical notes at the Mayo Clinic. Involving human efforts to prepare a sense inventory and training data for disambiguation, the methods in these studies cannot keep pace with the increasing number of abbreviations and publications. Yu et al. (2006) applied their AbbRE algorithm (Yu et al., 2002) to obtain an abbreviation dictionary. Their performance was 95% precision and 82% coverage for disambiguating 60 kinds of abbreviations in MEDLINE. Stevenson et al. (2009) extracted training data from MEDLINE abstracts using a method for abbreviation recognition (Schwartz and Hearst, 2003). They reported 99.0% accuracy for abbreviation disambiguation, but the experiment was limited to 21 kinds of abbreviations.

The most similar work is Gaudan et al. (2005). Instead of implementing their own abbreviation recognition, they used the Simple and Robust Abbreviation Dictionary (Adar, 2004), which was built automatically from MEDLINE abstracts. They performed clustering of expanded forms using similarities of two different kinds. One is cosine similarity of letter tri-grams. The other is the Dice similarity of context words (surrounding words) of expanded forms. Although it is much simpler, the former was intended to capture the similarities of expanded forms in the same manner as our clustering method does. The latter is designed to capture similarities of context in which expanded forms appear. As we discuss later, this would engender a problem in performance evaluation of abbreviation disambiguation. The WSD classifiers for abbreviation disambiguation were modeled using SVMs with linear kernels. Features for the classifiers consist of multi-word expressions. They excluded abbreviation definitions occurring <40 times from their evaluation set. They reported 0.985 accuracy, 0.989 precision, 0.982 recall and 0.985 F1 score on 7806 polysemic abbreviations with an average of 1.57 senses. This performance is comparable to that of this study (Table 5).

Two issues are raised in their work, which should be examined carefully. One is that their work lacks independent evaluation of clustering. They might assume that the performance of clustering can be measured indirectly by the performance of abbreviation disambiguation. The problem of this indirect evaluation is closely linked with the other issue in their work. That is, their clustering of expanded forms uses the similarity of context in which expanded forms appear. They claimed the context similarity can detect synonym-like word substitution. However, because the context similarity is also used for abbreviation disambiguation, this might hide errors in clustering. In other words, their experimental setting might conceal difficult instances of abbreviation disambiguation because the clustering method might merge different senses of an abbreviation that share the similar context. In contrast, the clustering of expanded forms described in this article is based solely on the similarity among expanded forms with more refined similarity measure than letter tri-grams. This study evaluates the performance of the clustering method independently of abbreviation disambiguation.

For reference, we implemented their clustering method. Their similarity measure (with the threshold parameters described in their article) performed worse on the evaluation corpus in Section 3.1 (0.890 accuracy, 0.977 precision, 0.311 recall and 0.471 F1 score); the performance of the clustering method was 0.971 precision, 0.562 recall and 0.712 F1 score. After we tuned the threshold of the letter tri-gram similarity from 0.8 (the original parameter) to 0.45, their clustering method reached the peak performance of 0.881 F1 score, which is still lower than that of our clustering method (0.915 F1 score). Therefore, we argue that, although the performances of the two systems on abbreviation disambiguation are similar, their sense inventories include more errors than ours. We also argue that the errors of the sense inventory were hidden in their evaluation of abbreviation disambiguation.

5 CONCLUSION

In this article, we described an approach for building a sense inventory of abbreviations. Results showed that single-link clustering with the ML-based similarity measure contributed to abbreviation disambiguation. The proposed method obtained 0.984 accuracy and 0.986 F1 score on the training and test sets obtained from MEDLINE. Although the performance figure of abbreviation disambiguation is roughly comparable to the previous work, we specially demonstrated the quality of the sense inventory on which abbreviations are disambiguated into concepts or senses. Results also show that broader contexts (e.g. abstracts and sentences) were more useful than local contexts (e.g. neighbor words) for abbreviation disambiguation. A future direction of this study is to apply the methodology of abbreviation management for MEDLINE abstracts to full-paper articles. Because the proposed method can handle variation and ambiguity problems of abbreviations, we plan to explore the impact of abbreviation disambiguation to other text-mining tasks such as information retrieval, named entity recognition and co-reference resolution.

Funding: UK Joint Information Systems Committee (JISC) (to National Centre for Text Mining); Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (grant BB/E004431/1) and JISC, National Centre for Text Mining project.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

Footnotes

1Features #1 and #4 introduce a feature function for each n-gram, where n is 1, 2 or 3. Consequently, the number of orthographic features is nine.

2We tokenize expressions with non-alphanumeric letters.

3In general, features for broader (e.g. abstract) contexts include words in narrower (e.g. neighbor and local) contexts, but drop the information of occurrence positions as ‘bag of words.’

4Refer to Section 3.1 for the clustering algorithm and threshold.

5An expanded form s is required to be less than t in dictionary order.

6In the single-link algorithm, two distant expanded forms are merged only if another expanded form exists, which is closer to both expanded forms than it is to the threshold. This behavior is called a chaining effect and is regarded as a disadvantage of the single-link algorithm.

7This experimental setting is similar to that of Gaudan et al. (2005).

REFERENCES

- Adar E. SaRAD: A simple and robust abbreviation dictionary. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:527–533. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ananiadou S, et al. Text mining and its potential applications in systems biology. Trends Biotechnol. 2006;24:571–579. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger AL, et al. A maximum entropy approach to natural language processing. Comput. Linguist. 1996;22:39–71. [Google Scholar]

- Chang JT, Schütze H. Abbreviations in biomedical text. In: Ananiadou S, McNaught J, editors. Text Mining for Biology and Biomedicine. MA, USA: Artech House, Inc.; 2006. pp. 99–119. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen WW, et al. A comparison of string distance metrics for name-matching tasks. Proceedings of the IJCAI-2003 Workshop on Information Integration on the Web (IIWeb-03). 2003:73–78. [Google Scholar]

- Erhardt R.A.-A, et al. Status of text-mining techniques applied to biomedical text. Drug Discov. Today. 2006;11:315–325. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2006.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federiuk CS. The effect of abbreviations on MEDLINE searching. Acad. Emerg. Med. 1999;6:292–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1999.tb00392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudan S, et al. Resolving abbreviations to their senses in MEDLINE. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3658–3664. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lance GN, Williams WT. A general theory of classificatory sorting strategies. 1. Hierarchical systems. Comput. J. 1967;9:373–380. [Google Scholar]

- Levenshtein VI. Binary codes capable of correcting deletions, insertions, and reversals. Sov. Phys. Dokl. 1966;10:707–710. [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Friedman C. Mining terminological knowledge in large biomedical corpora. Eighth Pacific Symposium on Biocomputing (PSB 2003). 2003:415–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, et al. Disambiguating ambiguous biomedical terms in biomedical narrative text: an unsupervised method. Comput. Biomed. Res. 2001;34:249–261. doi: 10.1006/jbin.2001.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, et al. Automatic resolution of ambiguous terms based on machine learning and conceptual relations in the UMLS. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2002a;9:621–636. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, et al. A study of abbreviations in MEDLINE abstracts. Proceedings of AMIA Symposium. 2002b:464–468. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCray AT, Tse T. Understanding search failures in consumer health information systems. Proceedings of the AMIA Annual Symposium. 2003:430–434. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadeau D, Turney PD. Eighth Canadian Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AI'2005) (LNAI 3501) Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer; 2005. A supervised learning approach to acronym identification; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Nocedal J. Updating quasi-newton matrices with limited storage. Math. Comput. 1980;35:773–782. [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki N, Ananiadou S. Building an abbreviation dictionary using a term recognition approach. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:3089–3095. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki N, et al. A discriminative alignment model for abbreviation recognition. Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Computational Linguistics (Coling 2008). 2008:657–664. [Google Scholar]

- Pakhomov S, et al. Abbreviation and acronym disambiguation in clinical discourse. Proceedings of the Americal Medical Informatics Association (AMIA) Annual Symposium (AMIA-2005). 2005 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y, Byrd RJ. Hybrid text mining for finding abbreviations and their definitions. 2001 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP). 2001:126–133. [Google Scholar]

- Pustejovsky J, et al. Automatic extraction of acronym meaning pairs from MEDLINE databases. MEDINFO 2001. 2001:371–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz AS, Hearst MA. A simple algorithm for identifying abbreviation definitions in biomedical text. Pacific Symposium on Biocomputing (PSB 2003). 2003;(8):451–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehgal AK, Srinivasan P. Retrieval with gene queries. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:220. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson M, et al. Disambiguation of biomedical abbreviations. Proceedings of the BioNLP 2009 Workshop. 2009:71–79. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler WE. Technical Report R99/04, Statistics of Income Division. Washington, USA: Internal Revenue Service Publication; 1999. The state of record linkage and current research problems. [Google Scholar]

- Wren JD, et al. Biomedical term mapping databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D289–D293. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarowsky D. Unsupervised word sense disambiguation rivaling supervised methods. Proceedings of the 33rd Annual Meeting on Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL 1995). 1995:189–196. [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, et al. Mapping abbreviations to full forms in biomedical articles. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2002;9:262–272. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M0913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, et al. A large scale, corpus-based approach for automatically disambiguating biomedical abbreviations. ACM Trans. Inform. Syst. 2006;24:380–404. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou , et al. ADAM: another database of abbreviations in MEDLINE. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2813–2818. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]