Abstract

This study examined the effects of state self-focused attention on sexual arousal and trait self-consciousness on sexual arousal and function in sexually functional (n = 16) and dysfunctional (n = 16) women. Self-focused attention was induced using a 50% reflectant television screen in one of two counterbalanced sessions during which self-report and physiological sexual responses to erotic films were measured. Self-focused attention significantly decreased vaginal pulse amplitude (VPA) responses among sexually functional but not dysfunctional women, and substantially decreased correlations between self-report and VPA measures of sexual arousal. Self-focused attention did not significantly impact subjective sexual arousal in sexually functional or dysfunctional women. Trait private self-consciousness was positively related to sexual desire, orgasm, compatibility, contentment and sexual satisfaction. Public self-consciousness was correlated with sexual pain. The findings are discussed in terms of Masters and Johnson’s [Masters, W. H. & Johnson, V. E. (1970). Human sexual inadequacy. Boston: Little, Brown) concepts of “spectatoring” and “sensate focus.”

Keywords: Sexual arousal, Self-focus, Private self-consciousness, Public self-consciousness, Spectatoring

Introduction

Following the publication of Duval and Wicklund’s (1972) landmark book on self-awareness, research on the behavioral impact of directing one’s attention either inwardly toward the self (private self-focus) or outwardly toward the environment (public self-focus) increased dramatically. The behavioral consequences of self-focused attention have been studied from both a state (self-awareness) and dispositional trait (self-consciousness) perspective. The induction of private self-awareness tends to make people more aware of their own bodies and internal states, whereas the induction of public self-awareness makes people more aware of their appearance and behavior (Buss, 2001). Research suggests close parallels between trait and state measures of this construct. That is, whether measuring state self-awareness or trait self-consciousness, if attention is directed toward the private aspects of oneself, there is a better understanding of one’s emotions, motives, attitudes, and bodily sensations, and if attention is directed toward the public aspects of oneself, there is an increased awareness of how others view oneself (Buss, 2001).

The construct of self-focused attention has been applied to further the understanding of a variety of clinically relevant syndromes including alcoholism, anxiety, and depression (for review, see Ingram, 1990), and has been discussed as relating to sexual function since Masters & Johnson’s (1970) introduction of the constructs “spectatoring” and “sensate focus.” Spectatoring refers to focusing on and evaluating oneself from a third person perspective during sexual activity. This focus of attention outward on sexual performance rather than inward on the sensory aspects of a sexual experience (i.e., sensate focus) is believed to have deleterious effects on sexual performance. Barlow (1986) proposed that deficits in sexual functioning due to inhibited excitement are largely due to disruptions in the processing of erotic cues necessary for arousal. These disruptions occur when sexual performance cues (i.e., those which occur during spectatoring) activate performance anxiety. This, in turn, leads to a shift in attention from reward-motivated focus on arousal cues to threat-motivated focus on sexual failure. Negative affect may perpetuate this cycle of dysfunctional sexual responding by contributing to an avoidance of erotic cues and consequent focus on nonerotic cues (Barlow, 1986). Indeed, a number of laboratory studies have demonstrated that cognitive distraction can impair sexual arousal in women (Adams, Haynes, & Brayer, 1985; Dove & Wiederman, 2000; Elliott & O’Donohue, 1997; Koukounas & McCabe, 1997;Przybyla & Byrne, 1984), and numerous treatment outcome studies have noted the beneficial effects of sensate focus for treating sexual desire and orgasm difficulties in women (Heiman & Meston, 1998). To the extent that spectatoring involves focusing on one’s appearance and performance-related thoughts, and sensate focus involves directing one’s attention to the physical sensations that accompany sexual arousal, spectatoring and sensate focus might be viewed as behavioral manifestations of public and private self-awareness, respectively.

For over three decades, the theoretical construct of spectatoring has permeated the sexual dysfunction literature, and sensate focus has remained a widely used therapeutic technique for treating female sexual difficulties. Given that both these constructs pertain directly to mechanisms involving self-awareness, it is surprising that no research has directly examined the sexual consequences of either state or trait self-focused attention on sexual responding in women. Except in the very proximal sense of studies on cognitive distraction, only one study has even indirectly assessed whether experimentally induced self-focus impacts sexual responding in women. In this study (Korff & Geer, 1983), women were either instructed to attend to their genital sensations while viewing an erotic film or were given no instructions. The authors noted higher correlations between genital and self-reported sexual arousal in women who were instructed to focus on their genital activity. These findings lend support to the notion that inducing private self-awareness (i.e., focusing on internal cues) enhances concordance between subjective and physiological sexual responses in women.

Studies on the effects of self-focused attention on male sexual responding have shown somewhat inconsistent results. In the presence of a highly arousing sexual stimulus, self-focused attention did not impact physiological arousal in either sexually functional (Beck & Barlow, 1986; Beck, Barlow, & Sakheim, 1983; Lange, Wincze, Zwick, Feldman, & Hughes, 1981) or dysfunctional (Beck et al., 1983) men. In the presence of a low-intensity sexual stimulus, some studies showed self-focused attention decreased physiological sexual arousal in sexually functional men (Sakheim, Barlow, Beck, & Abrahamson, 1984; Wincze, Venditti, Barlow, & Mavissakalian, 1980), while other studies found it enhanced sexual arousal in both sexually functional and dysfunctional men (Beck et al., 1983). In a recent study, van Lankveld, van den Hout, and Schouten (2004) examined the interaction effects of self-focused attention (induced using a camera pointed at the participant), performance demand, and trait self-consciousness on sexual responding in sexually functional and dysfunctional men. While there was no main effect of self-focus on physiological sexual arousal, self-focused attention inhibited genital responding in men high on trait self-consciousness measures, and enhanced penile tumescence in men low on trait self-consciousness. In this same study, self-focused attention enhanced self-reported sexual arousal among sexual functional men, and decreased subjective sexual arousal among sexually dysfunctional men but only when the self-focus condition was presented first. Two earlier studies that also examined the interaction between self-focused attention (induced by having subjects use a subjective lever) and performance demand found no main effects or interaction effects in sexually functional males (Beck & Barlow, 1986; Lang et al., 1981). van Lankveld and associates hypothesized the null findings in these two earlier studies may be attributable to the within-subjects design used and the consequent potential for carry-over effects of performance demand instructions.

The present study represents the first empirical investigation of the effects of experimentally induced self-awareness on self-report and physiological sexual responses in women, and the first investigation of the relation between trait self-consciousness and sexual function in women. This study is also the first to examine the impact of either state or trait self-focused attention on sexual responding in a group of sexually dysfunctional women. The overall goal of this research is to help elucidate the cognitive factors involved in the etiology and maintenance of female sexual dysfunction.

With regard to state self-focused attention, it was predicted that inducing an experimental analogue of spectatoring would impair sexual responding in both sexually functional and sexually dysfunctional women. This hypothesis was based on findings from numerous studies that point to the deleterious effects of cognitive distraction on sexual arousal in women (e.g., Adams et al., 1985;Dove & Wiederman, 2000; Elliott & O’Donohue, 1997; Koukounas & McCabe, 1997; Przybyla & Byrne, 1984). The impairment was expected to be greater among sexually dysfunctional than functional women. Women with a history of sexual arousal difficulties are more likely to have negative performance related cognitions than do women with a history of positive sexual experiences. To the extent that focusing on oneself in a sexual situation would trigger these cognitions, Barlow’s (1986) model of sexual dysfunction would predict greater impairment among dysfunctional women because of the greater levels of negative affect that would result.

From a trait perspective, it was predicted that private self-consciousness would be positively related to sexual functioning. This hypothesis is based on research which indicates that individuals high in private self-consciousness show more intense responses to emotional manipulations, are more aware of their own bodies and internal states, and show a higher concordance between self-report and behavioral measures (Buss, 2001). Given that individuals high in private self-consciousness are focused on internal bodily sensations, and focusing on genital sensations (i.e., during sensate focus) is assumed to enhance sexual responding, it was predicted that dispositional private self-consciousness would be a beneficial trait in the arena of sexual function. The extent to which public self-consciousness impacts sexual responding likely has more to do with the evaluative appraisal of how others view them than the tendency to focus on how they are perceived per se. In other words, if a woman’s appraisal of how she is viewed by her sexual partner is high, public self-consciousness could positively impact her sexual experience; if her appraisal is negative, this trait could be detrimental to her sexual response. Based on this reasoning, it was predicted public self-consciousness would not be directly related to measures of sexual function.

Method

Participants

Women who responded to local radio and newspaper advertisements were interviewed by a trained clinical psychology student. They were first asked whether they were currently experiencing any sexual difficulties and, if so, to describe what they were and whether they were distressed by them. They were then interviewed to determine whether they met criteria for a DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) sexual dysfunction, including HSDD, FSAD, Female Orgasmic Disorder, Dyspareunia, and Vaginismus, and whether they met DSM-IV-TR for an Axis I disorder. The women were also asked their age, their sexual orientation, if they were pregnant, if they were currently taking any medications or herbal remedies, and whether they were currently sexually active. Participants were excluded from participation if they were under the age of 18 or over the age of 70, if they were not currently in a sexually active heterosexual relationship, and if they met criteria for a DSM-IV Axis I disorder including: organic mental syndromes and disorders, schizophrenia, delusional disorder or psychotic disorders not classified elsewhere, bipolar disorder, eating disorders, panic disorder, if they had a history of significant substance abuse disorder within a year before the start of the study, if they were pregnant, or if they were currently receiving any medications known to affect vascular or sexual functioning (including antidepressants, antihypertensives). The stringent psychological criteria were used to increase the homogeneity of the sample and because it is unclear to what degree the presence of disorders such as anorexia, where self-image concerns are clearly a factor, may influence a woman’s sexual response in this type of experimental setting. Potential volunteers were told the purpose of the study was to investigate the effects of erotic films and their content on women’s sexual arousal. Volunteers were paid $50.00 for their participation.

Further inclusion criteria for control women were: absence of DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) diagnosis of Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder, Female Sexual Arousal Disorder (FSAD), Female Orgasmic Disorder, dyspareunia, vaginismus, or sexual anxiety disorder. Further inclusion criteria for sexually dysfunctional women were: DSM-IV diagnosis of FSAD. Eighteen women met the criteria for the control group and 17 women met criteria for the sexually dysfunctional group. One sexually functional and another sexually dysfunctional woman did not return for the second session. Data from one control participant were eliminated from data analysis because of technical difficulties during psychophysiological testing that rendered the data unreliable. The final sample size was 16 control and 16 sexually functional women. All of the sexually dysfunctional women met DSM-IV criteria for FSAD. Of these, 6 (38%) also met criteria for Female Orgasmic Disorder, and 2 (13%) also met DSM-IV criteria for Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder. Two of the women with FSAD were diagnosed with both Female Orgasmic Disorder and Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder.

Procedures

Women who responded to the advertisements were interviewed via telephone to assess whether or not they met the study inclusion criteria and were informed of the experimental procedures. Those who met the criteria and chose to participate were scheduled for their first of two sessions at the Female Sexual Psychophysiology Laboratory at the University of Texas at Austin. This laboratory consists of a computer/psychophysiological equipment room in which the experimenter is located during assessment, and an adjoining, private, internally locked participant room. An intercom system between the participant and experimenter rooms allows for communication with participants at all times. A 27-in color television monitor is positioned in the participant room at a distance that allows the woman to sit comfortably in a recliner with a full view of the screen.

During the first session, the participant signed the informed consent document and was given a chance to ask any questions. They were then administered a battery of questionnaires including: the Self-Consciousness Questionnaire (Fenigstein, Scheier, & Buss, 1975), the Body Image Scale from the Derogatis Sexual Functioning Inventory (DSFI; Derogatis, 1978), the Female Sexual Function Index (Rosen et al., 2000), and the Sexual Satisfaction Scale (Meston & Trapnell, 2005). Following completion of the questionnaires, participants engaged in one of two experimental conditions: self-focus, no self-focus. During the no self-focus condition, participants were asked to sit in the recliner and insert the vaginal photoplethysmograph once the experimenter left the room. Depth and orientation of the probe insertion was standardized between women using a device developed by the Instrumentation Department of the Academic Medical Hospital in Amsterdam. This device is a 9- × 2-cm rubber plate with a hole in the center that allows for the photoplethysmograph to be pulled through and fixed to the cable at a distance 5 cm from the center of the probe. Participants were instructed to insert the photoplethysmograph such that the device would touch their labia. To minimize potential movement artifacts, participants were asked to remain as still as possible throughout the session. When participants notified the experimenter, via the intercom system, that they had finished inserting the plethysmograph, a 10-min adaptation recording was taken. After the adaptation period, participants viewed one of two 9 min videotaped sequences that consisted of the word “relax” (1 min), a nonsexual travel segment (3 min), and an erotic film segment (5 min). The erotic segments were taken from films produced specifically for female viewers, and depicted a hetereosexual couple engaging in foreplay and intercourse. The erotic segments used in the videotaped sequences were matched on the number and type of sexual activities and had been previously shown to be sexually arousing in women (Meston & McCall, in press). During the no self-focus condition, a piece of clear, non-reflective glass was positioned directly in front of the television screen in a manner which did not interfere with full viewing of the television screen. Immediately after the erotic film, participants filled out a subjective sexual arousal rating scale and the Self-Focus Sentence Completion questionnaire (Exner, 1973).

The self-focus condition was identical to the no self-focus condition with the following exception: a piece of 50% reflection glass was positioned directly in front of the television screen in a manner that did not interfere with clear viewing of the videotaped sequence, but allowed participants to see a reflected image of their face and shoulders while viewing the films. The effectiveness of using this technique to induce self-awareness has been discussed at length in Carver and Scheier (1978).

If, during either session, participants asked the experimenter why there was a piece of glass in front of the television screen, they were told the following “We find our television gives off a certain amount of glare in this room and the glass helps to minimize this.” The experimental conditions, self-focus and no self-focus, were counterbalanced across sessions; the two videotaped sequences were counterbalanced across conditions. After completing both sessions, participants were thoroughly debriefed, informed about the additional purposes and goals of the study, and paid for their participation. The study was approved by the ethics review committee at the University of Texas.

Measures and data reduction

Assessment of sexual function

Female sexual function index (FSFI)

The FSFI is a brief, 19-item self-report measure of female sexual function that provides scores on six domains of sexual function as well as a total score (Rosen et al., 2000). The domains assessed have been confirmed using factor analyses and include: desire (2 items), arousal (4 items), lubrication (4 times), orgasm (3 items), satisfaction (3 items), and pain (3 items). The FSFI was developed on a female sample of 131 controls (age range, 21–68) and 128 age-matched subjects (age range, 21–69) who met DSM-IV criteria for FSAD. The FSFI has been shown to reliably discriminate FSAD and control patients on each of the six domains of sexual function as well as the Full Scale score (Rosen et al., 2000), and to reliably discriminate between women with Female Orgasmic Disorder and/or Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder and sexually functional women (Meston, 2003). Wiegel, Meston and Rosen (2005) reported acceptable levels of internal consistency within each subscale (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.82–0.98). Rosen et al. (2000) reported inter-item reliability values within the acceptable range for sexually healthy women (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.82–0.92), as well as for women with diagnosed FSAD (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.89–0.95). Test–retest reliabilities assessed using a four week interval ranged between Pearson’s r = 0.79–0.86 (Rosen et al., 2000).

Sexual satisfaction scale (SSS)

The SSS is a 30-item, five factor, self-report measure of sexual satisfaction. Factors consist of 6 items each and include: Contentment (e.g., “I often feel something is missing from my present sex life”), Communication (e.g., “I have no difficulty talking about my deepest feelings and emotions when my partner wants me to”), Compatibility (e.g., “I sometimes think my partner and I are mismatched in needs and desires concerning sexual intimacy”), Interpersonal Concern/Distress (e.g., “I’m worried that my partner views me as less of a woman because of my sexual difficulties”), and Personal Concern/Distress (e.g., “I’m so distressed about my sexual difficulties that it affects my own well-being”). Internal consistency coefficients for the SSS range from 0.65 to 0.91, test retest reliability ranges from 0.62 to 0.79. The SSS has been shown to reliably discriminate between sexually functional women and women with FSAD and/or Female Orgasmic Disorder (Meston & Trapnell, 2005).

Assessment of trait characteristics

Self-consciousness questionnaire

The Self-Consciousness Questionnaire was used to measure Private self-consciousness (10 items) and Public self-consciousness (7 items). The Private self-consciousness scale assesses introspective or self-reflective tendencies (e.g., “I’m always trying to figure myself out,” “I’m generally attentive to my inner feelings”) and has no conceptual link to either shyness or self-esteem (Buss, 2001). Items on the Public self-consciousness scale deal with attending to one’s appearance and outwardly observable behavior (e.g., “I usually worry about making a good impression,” “I’m concerned about the way I present myself”). Scores on the Public self-consciousness scale are correlated with shyness and self-esteem. Correlations between Public and Private Self-consciousness range from the 0.20 s to the 0.40 s (Buss, 2001).

Body image scale

Body image was measured using the DSFI Body Image subscale. This scale consists of self-ratings on five gender-specific physical attributes (e.g., “Men would find my body attractive”) and 10 general body attributes (e.g., “My face is attractive”). The 15 ratings are summed to provide a single numerical index of level of dissatisfaction with one’s physical appearance or body image.

Assessment of sexual responding

Self-report sexual responses to the erotic film

A self-report rating scale, adapted from Heiman and Rowland (1983), was used to assess subjective measures of sexual arousal. Participants rated each of these items, depending on the degree to which they experience the sensations, on a 7-point Likert scale, from “Not at all” to “Intensely.” The following six items defined subjective sexual arousal: warmth in genitals, genital wetness or lubrication, genital pulsing or throbbing, genital tenseness or tightness, any genital feeling, sexually aroused.

Physiological sexual responses to the erotic film

A vaginal photoplethysmograph (Sintchak & Geer, 1975) was used to measure vaginal pulse amplitude (VPA) responses. VPA was sampled at a rate of 60 samples/s throughout the entire 180 s of neutral film and 300 s of erotic film, band-pass filtered (0.5–30 Hz), and recorded on a Dell Pentium computer using the software program AcqKnowledge III, Version 3.2 (BIOPAC Systems, Inc., Santa Barbara, CA) and a Model MP100WS data acquisition unit (BIOPAC Systems, Inc.) for analog/digital conversion. In accordance with previous studies of this nature (Meston & Gorzalka, 1996; Meston & Heiman, 1998), artifacts caused by movement or contractions of the pelvic muscles were deleted using the computer software program following visual inspection of the data. VPA scores were computed for both the nonsexual and erotic films by averaging across the entire 3 min of the neutral and 5 min of the erotic film stimuli. In order to control for potential variations in baseline levels of VPA to the neutral films between sessions, difference scores were calculated by subtracting the mean of the nonsexual film from the mean of the sexual film within each experimental condition.

Affective responses to the erotic films

The self-focus sentence completion task is a validated measure of egocentrism (Exner, 1973). The questionnaire consists of 30 sentences, which begin with phrases such as “I am…,” and “If only I would …” Participants are asked to complete all of the sentences in the blank spaces provided. Participant responses were analyzed for usage of affective and first person words using a computerized text analysis program called Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC; Pennebaker, Francis, & Booth, 2001). LIWC uses a word count strategy that searches for over 2000 words or word stems within any given text file. The search words have been categorized by independent judges into over 70 linguistic dimensions, including standard language categories (e.g., articles, prepositions, pronouns), psychological processes (e.g., positive and negative emotion categories), relativity-related words (e.g., time, verb tense, motion, space), and traditional content dimensions (e.g., sex, death, occupation).

Results

Participant characteristics

There were no significant age differences between sexually functional and dysfunctional women. Results from a 2 (Group: Functional vs. Dysfunctional) × 6 (FSFI Domain) repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect for Group, F(1, 28) = 25.67, p<0.001, and a significant interaction between Group and FSFI Domain, F(5, 24) = 4.11, p<0.01. Follow-up analyses indicated significantly lower levels of Desire, t(29) = 2.83, p<0.01, Arousal, t(28) = 3.81, p<0.001, Lubrication, t(29) = 5.00, p<0.001, Orgasm, t(29) = 4.06, p<0.001, and Satisfaction, t(29) = 2.26, p<.05, and significantly higher levels of Pain, t(29) = 2.31, p<0.05, among sexually dysfunctional versus functional women. These results serve as a validity check on the classification of women as sexually functional and dysfunctional. Results from a 2 (Group) × 5 (SSS Domain) repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect for Group, F(1, 28) = 11.79, p<0.001. Sexually dysfunctional women reported significantly lower levels of Contentment, t(27) = 3.18, p<0.01, significantly higher levels of interpersonal concern/distress, t(29) = 4.21, p<0.001, and personal concern/distress, t(29) = 3.99, p<0.001, and showed a trend towards lower levels of sexual compatibility, t(29) = 1.87, p = 0.07, than did sexually functional women. Sexually functional and dysfunctional women did not differ significantly on measures of sexual communication.

There were no significant group differences on measures of Public or Private Self-Consciousness. The correlation between measures of Public and Private Self-Consciousness in this sample (r(33) = 0.23, p = 0.20) was consistent with that noted in past research (Buss, 2001). Sexually dysfunctional women showed a trend towards lower body image than did sexually functional women, t(28) = 1.86, p = 0.07. Mean (± SDs) for age, FSFI and SSS Domain scores and trait characteristics are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Sexually functional N = 16 |

Sexually dysfunctional N = 16 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) | 28.9 (8.4) | 32.3 (10.2) |

| Age range | 18–47 | 21–53 |

| Female sexual function index | Mean (SD) | |

| Desire | 7.8 (1.3) | 5.9 (2.2)a |

| Arousal | 17.9 (2.2) | 13.3 (4.1)b |

| Lubrication | 19.1 (1.2) | 12.5 (5.0)b |

| Orgasm | 12.8 (2.7) | 7.9 (3.8)b |

| Satisfaction | 12.5 (2.9) | 9.8 (3.7)a |

| Pain (lack of) | 14.3 (1.7) | 11.7 (4.0)a |

| Sexual satisfaction scale | Mean (SD) | |

| Contentment | 21.2 (4.7) | 15.1 (5.4)a |

| Communication | 24.4 (4.6) | 21.3 (5.7) |

| Compatibility | 25.5 (5.3) | 21.6 (6.4) |

| Concern interpersonal (lack of) | 25.8 (4.0) | 18.1 (5.9)b |

| Concern personal (lack of) | 23.9 (5.6) | 15.9 (5.4)b |

| Body image scale | 56.0 (10.0) | 50.2 (6.4) |

| Public self-consciousness | 16.6 (5.5) | 17.3 (6.8) |

| Private self-consciousness | 27.93 (4.8) | 27.3 (5.1) |

Significant difference between sexually functional and dysfunctional women (p<0.05).

Significant difference between sexually functional and dysfunctional women (p<0.001).

The effects of state self-focused attention on affective measures

Separate 2 (Group) × 2 (Condition: self-focus versus no self-focus) repeated-measures MANOVAs were conducted on the total number of affect words (e.g., happy, ugly, bitter) and total first person words (e.g., I, we, me) used in the self-focus sentence completion task. With respect to affect words, results indicated a significant main effect for Group, F(1, 30) = 7.21, p<0.01, and a significant interaction between Group and Condition, F(1, 30) = 15.88, z. Follow-up analyses revealed significantly more affect words among sexually dysfunctional than functional women in the self-focus condition, t(30) = −5.38, p<0.001. Sexually dysfunctional women used significantly more affect words in the self-focus versus no self-focus condition, t(15) = 3.12, p<0.01, while sexually functional women used more affect words in the no self-focus condition, t(15) = −2.69, p<0.05.

Words in the affect category may be subdivided into the following domains: positive feeling words (e.g., happy, joy, love), sadness- or depression-related words (e.g., grief, cry, sad), negative emotion words (e.g., hate, worthless, enemy), and anxiety-related words (e.g., nervous, afraid, tense). Exploratory analyses were conducted on these sub categories of affect words to examine whether the usage of specific types of affect words differed between conditions and/or groups. Sexually dysfunctional women used more positive feeling words, t(15) = 2.37, p<0.05, more sad words, t(15) = 2.12, p<0.05, and showed a trend towards more negative emotion words, t(15) = 2.0, p = 0.07, in the self-focus versus no self-focus condition. There were no significant condition differences in number of positive feeling words or anxiety words among sexually dysfunctional women. Sexually functional women showed a trend toward using more positive emotion words, t(15) = −2.04, p = 0.06, and more negative emotion words, t(15) = −1.90, p = 0.08, in the no self-focus versus self-focus condition. There were no significant differences between conditions in the usage of positive feeling words, anxiety words, or sad words among sexually functional women.

There was a significant interaction between Group and Condition for total first person words, F(1, 30) = 4.27, p<0.05. Follow-up analyses revealed sexually functional women used significantly more first person words in the no self-focus condition than did sexually dysfunctional women, t(30) = 2.13, p<0.05. See Table 2 for means and standard deviations of overall affect and first person words by Group and Condition.

Table 2.

Mean (±SD) affective and first person words used following the erotic films by group and condition

| Sexually functional | Sexually dysfunctional | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No self-focus | Self-focus | No self-focus | Self-focus | |

| First person words | 11.99 (1.7)a | 11.13 (3.0) | 10.49 (2.2)a | 11.31 (3.2) |

| Total affect words | 8.93 (3.2)b | 6.74 (2.1)a,b | 8.83 (2.2)b | 10.59 (2.0)a,b |

| Positive emotions | 6.60 (2.61) | 5.12 (2.0) | 6.11 (1.8) | 7.06 (2.5) |

| Positive feelings | 1.24 (1.11) | 1.47 (1.28) | 1.31 (0.9)b | 1.92 (1.4)b |

| Optimism | 1.49 (1.4) | 0.59 (0.58) | 1.22 (0.8) | 1.17 (1.1) |

| Negative emotions | 2.26 (1.3) | 1.63 (0.9) | 2.63 (1.3) | 3.47 (1.4) |

| Anxiety | 0.38 (0.6) | 0.25 (0.4) | 0.64 (0.7) | 0.60 (0.7) |

| Anger | 0.81 (1.0) | 0.39 (0.4) | 0.47 (0.6) | 0.61 (0.5) |

| Sad | 0.35 (0.5) | 0.51 (0.6) | 0.70 (0.8)b | 1.31 (1.0)b |

Significant difference between groups within condition (p<0.05).

Significant difference between conditions within group (p<0.05).

The effects of state self-focused attention on sexual arousal

Physiological sexual arousal

First, a 2 (Condition) × 2 (Order) repeated-measures MANOVA was conducted on log transformed VPA difference scores. There was no significant main effect for condition order and no significant interaction between Condition and Order (F’s<1). Consequently, order was not controlled for in subsequent analyses. Next, to ensure the erotic films increased sexual responses among participants, preplanned comparisons of log transformed vaginal responses (VPA scores) were conducted among sexually functional and dysfunctional women by condition. Compared with VPA responses averaged across the nonsexual film presentations, the erotic films significantly increased VPA scores among sexually functional and dysfunctional women in the no self-focus, t(15) = −2.30, p<0.01, t(15) = 3.03, p<0.01, and self-focus, t(15) = −2.30, p<0.05, t(15) = −2.79, p<0.01, conditions, respectively. These findings indicate the erotic films were effective in enhancing sexual arousal in both groups of women during both experimental sessions. VPA difference scores were used in subsequent analyses.

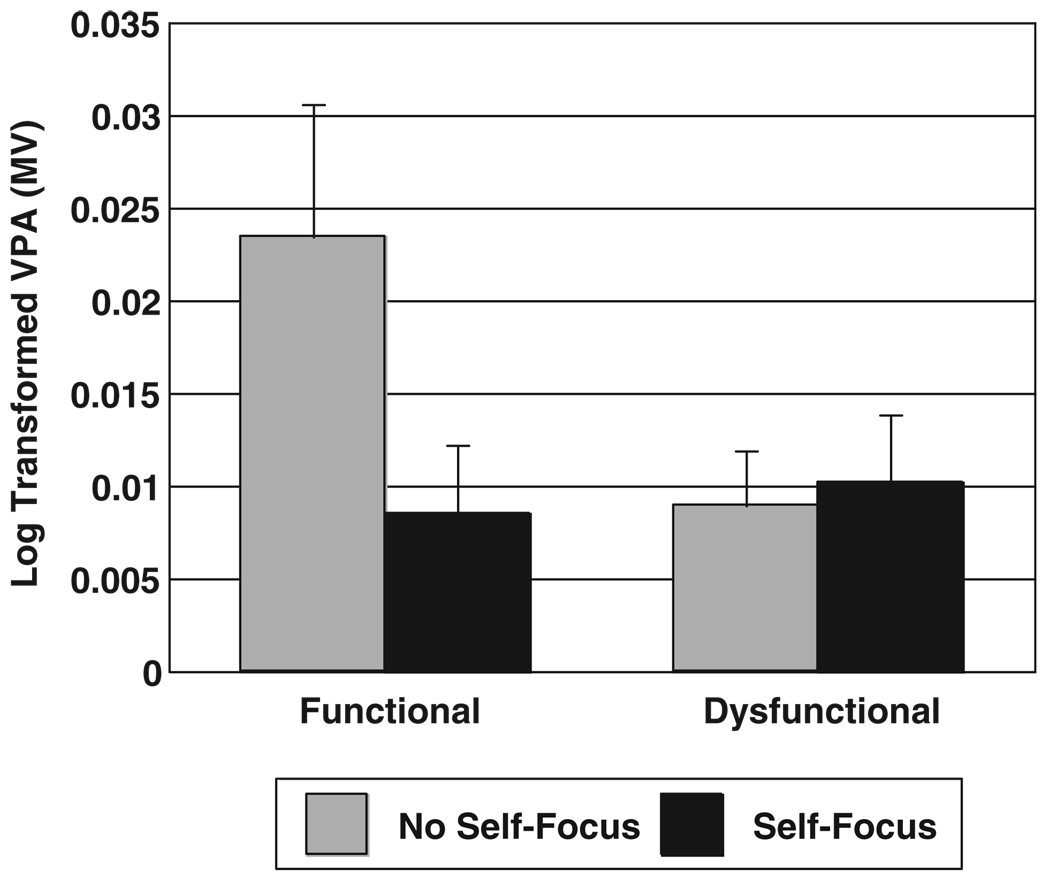

A 2 (Group) × 2 (Condition) repeated-measures MANOVA was conducted on log transformed VPA difference scores. Results yielded a marginally significant interaction between Condition and Group, F(1, 30) = 3.85, p = 0.06. Effect sizes for the differences between conditions, groups, and the interaction between conditions and groups were, η2 = 0.084, 0.049, and 0.114, respectively. Follow-up analyses indicated sexually functional women were significantly more physiologically sexually aroused during the no self-focus than self-focus condition, t(15) = −2.37, p<0.05, and showed marginally higher levels of physiological arousal than did sexually dysfunctional women in the no self-focus condition, t(30) = 1.88, p = 0.07.

There were no significant differences between sexually functional and dysfunctional women in their physiological sexual responses during the self-focus condition, and no significant difference in responses between the self-focus and no self-focus condition among sexually dysfunctional women. See Fig. 1 for VPA means and standard deviations by Group and Condition.

Fig. 1.

Group differences in vaginal pulse amplitude responses during the self-focus and no self-focus conditions.

Self-reported sexual arousal

To examine potential order effects, a 2 (Condition) × 2 (Order) repeated-measures MANOVA was conducted on self-reported sexual arousal. There was a significant interaction between Condition and Order, F(1, 29) = 6.40, p<0.05, such that when the no self-focus condition was presented first, participants reported higher sexual arousal in the no self-focus condition, t(15) = −2.28, p<0.05. Consequently, order was used as a covariate in subsequent analyses.

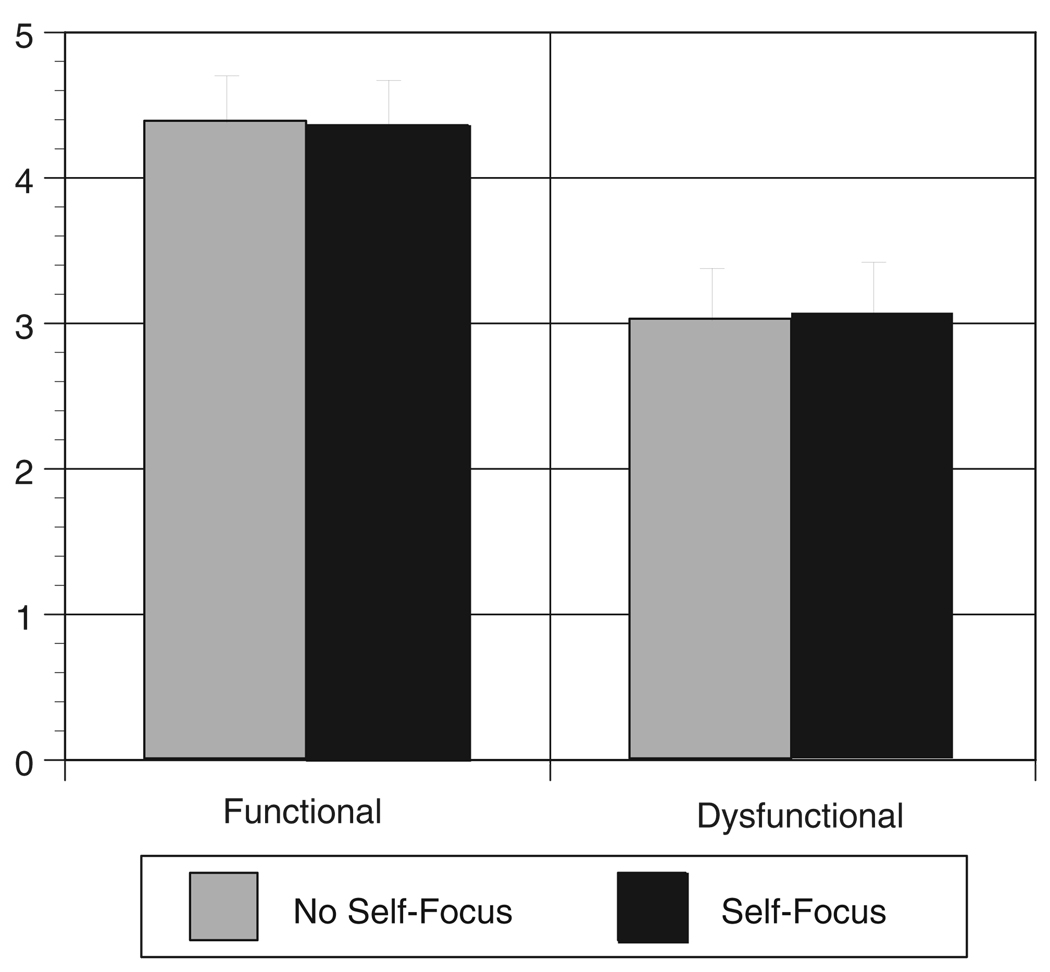

A 2 (Group) ×l 2 (Condition) × 2 (Order) repeated-measures MANOVA was conducted on self-report measures of sexual arousal to the erotic films. Results yielded a significant main effect for Group, F(1, 28) = 9.23, p<0.01. Effect sizes for the differences between conditions, groups, and order were, η2 = 0.00, 0.247, and 0.034, respectively. Effect sizes for the interactions between condition and group, and condition and order were, η2 = 0.003 and 0.177, respectively. See Fig. 2 for self-report sexual arousal means and standard deviations by Group and Condition.

Fig. 2.

Group differences in self-reported sexual arousal during the self-focus and no self-focus conditions.

Concordance between physiological and self-reported sexual arousal

Collapsed across groups, correlations between subjective and physiological sexual arousal were substantially higher in the no self-focus, r(32) = 0.35, p<0.05, than in the self-focus, r(32) = −.06, p = 0.75, condition.

The relation between trait self-consciousness and sexuality variables

First, to examine whether trait measures of self-consciousness were related to state levels of sexual arousal, separate correlations were conducted between measures of Public and Private Self-Consciousness and measures of self-reported and physiological sexual arousal to the erotic films during the self-focus and no self-focus condition. None of the correlations reached significance at p<0.05.

Next, to examine whether trait self-consciousness was related to validated self-report measures of sexual function, correlations were conducted between measures of Public and Private Self-Consciousness, FSFI Domain Scores, and SSS Domain Scores. Private Self-Consciousness was significantly positively related to sexual compatibility, r(32) = 0.38, p<0.05, and orgasm, r(32) = 0.37, p<0.05, and showed a trend towards a positive relation with sexual desire, r(32) = 0.30, p = 0.097, sexual satisfaction, r(32) = 0.31, p = 0.08, and sexual contentment, r(30) = 0.35, p = 0.059. Public Self-Consciousness was significantly negatively correlated with sexual pain, r(31) = −0.39, p<0.05.

The interaction of state self-focused attention and trait self-consciousness on sexual arousal

Exploratory analyses were conducted to examine whether Van Lankveld et al.’s (2004) finding of an interaction between self-focused attention and trait measures of self-consciousness on genital responding in men might be generalizable to women. Collapsed across sexual functioning status, women were divided into two groups of low (n = 14; mean </ = 16) and high (n = 10; mean >/ = 20) measures of public self-consciousness, and two groups of low (n = 11; mean </= 26.4) and high (n = 12; mean >/ = 30) measures of private self-consciousness. The means used to designate participants into these low and high groups represent the bottom 1/3 and top 1/3 of scores, respectively, on public and private self-consciousness measures.

There was a trend towards lower levels of physiological sexual arousal in the self-focus versus no self-focus condition among women high in public self-consciousness, t(10) = −1.90, p = 0.087, and a trend towards higher levels of physiological sexual arousal in the self-focus versus no self-focus condition among women low in public self-consciousness, t(12) = −2.08, p = 0.06. There were no significant differences in subjective ratings of sexual arousal between the self-focus and no self-focus conditions among women in either the low or high public self-consciousness groups (all p-values>0.6). There were no significant differences in physiological or subjective ratings of sexual arousal between the self-focus and no self-focus conditions among women in either the low or high private self-consciousness groups (all p-values>0.3).

Discussion

This study examined relations between state and trait self-focused attention and sexual function in women. It was predicted that making participants more self-aware in a sexual context would impair their sexual arousal responses. Inducing self-awareness was expected to have a greater impact on affective measures and a more detrimental influence on sexual arousal in sexually dysfunctional than functional women. Consistent with this hypothesis, sexually dysfunctional women used more affect words in the self-focus versus no self-focus condition, and used more affect words than functional women in the self-focus condition.

As expected, sexually dysfunctional women displayed overall lower levels of self-reported sexual arousal than did sexually functional women. Inconsistent with hypotheses, however, levels of self-reported sexual arousal were not significantly different between experimental and control conditions for either sexually functional or dysfunctional women. This finding contrasts findings in men that have shown self-focused attention increases subjective arousal in sexually functional men (Beck & Barlow, 1986; van Lankveld et al., 2004), and decreases subjective arousal in dysfunctional men when the self-focus (versus no self-focus) condition is presented first (van Lankveld et al., 2004).

Methodological differences between studies could account for these gender differences. In both the Beck and Barlow (1986) and van Lankveld et al. (2004) studies, the self-focus manipulation was made explicit to participants. Beck and Barlow (1986) induced self-focus by instructing the men to monitor their penile tumescence, and van Lankveld et al. (2004) induced self-focus by telling their participants that the experimenter would be watching them via a TV camera in the adjacent room. In the present study, self-focused attention was induced implicitly using a reflective glass designed to draw the participant’s attention to her appearance; no explicit instructions or information regarding the self-focus manipulation was given. This methodological procedure was chosen in an effort to decrease potential expectancy effects, and because the author felt that giving women explicit instructions would create an external demand for performance, which was not the focus of this study. In other words, the explicit instructions given in the male studies may, in addition to increasing self-awareness, have created an external demand for performance. Had explicit instructions been given in the present study, the women may have responded differently. Indeed, similar to the findings noted in men, Laan and associates (Laan, Everaerd, van Aanhold, & Rebel, 1998) showed that explicit instructions to perform sexually enhanced subjective sexual arousal in sexually functional women.

Contrary to expectations, physiological sexual arousal was not substantially impacted by the induction of self-awareness. Although sexually functional women showed significantly lower levels of VPA to erotic films in the self-focus versus no self-focus condition, inducing self-awareness did not substantially impact VPA responses among sexually dysfunctional women as predicted. One explanation for this null finding is that the sexually dysfunctional women may have also been focused on performance related thoughts and distracted by them during the control condition. If so, experimentally induced sexual self-awareness may not have had a further detrimental impact on sexual responding. In other words, it may be the case that self-focused attention can only impair sexual responding to a certain degree, and the dysfunctional women may have already reached this level during the control condition. This explanation would be consistent with the finding that sexually dysfunctional women showed significantly lower levels of VPA responses during the no self-focus condition compared to functional women, and with the finding that when the functional women were exposed to self-focus, their levels of VPA responses were comparable to those of the dysfunctional women. The extent to which sexually dysfunctional women naturally engage in self-focused attention during laboratory investigations of sexual responding is a question worthy of investigation.

When examined across groups, the correlation between VPA and self-reported arousal was lower in the self-focus than no self-focus condition. This is consistent with recent findings in men (van Lankveld et al., 2004). Given that using a mirror to induce self-focused attention may elicit both public and private self-awareness, explanations for this finding are tentative. To the extent that public self-awareness was elicited in the self-focus condition, women may have been more focused outwardly on their physical attributes and/or how they might be perceived in a sexual context than inwardly on their genital sensations. If so, this could account for the lower correlations between self-report and genital arousal. However, to the extent that private self-awareness was elicited in the self-focus condition, one would expect this condition to have elicited a higher concordance between measures. Unfortunately, no manipulation check on independent levels of public and private self-awareness was administered.

An obvious limitation to interpreting the findings for state self-awareness, relates to the degree to which the experimental manipulation was effective in inducing self-focused attention and can be considered an analogue for “spectatoring.” Using a mirror or reflectant glass has been shown to effectively induce self-awareness in many studies (Carver & Scheier, 1978). The fact that measures of affect significantly differed between conditions, independent of any potential order effect, suggests that the reflective glass did indeed have an impact on the women’s experience in the present study. One cannot be certain, however, that this impact was necessarily sexual. The glass reflected the woman’s face and upper body and this may have triggered more concerns with body image than sexual performance per se. If so, the impact on sexual arousal would likely have had more to do with the woman’s existing body image than her past sexual experiences. That is, if a woman had high body esteem, focusing her attention towards her body would have likely increased her sexual arousal. If a woman had low body esteem, however, focusing her attention towards her body would have likely induced negative affect and impaired her sexual response by distracting her from processing erotic cues. Exploratory correlations between body image scores and sexual arousal scores were conducted to test this post hoc explanation. Findings did not support this hypothesis; correlations between body image and physiological or subjective sexual arousal were not significant during either the self-focus or no self-focus conditions (all p-values >0.27).

Studies examining the impact of self-focused attention on sexual arousal in men have operationalized “spectatoring” by having the man focus on his erectile response. It is unclear, however, whether focusing on one’s genitals would serve as an appropriate analogue of specatatoring for women. For men, sexual performance, and related “performance anxiety,” are closely associated with the ability to attain and maintain an adequate erection until completion of the sexual act. Thus, it makes sense that directing a man’s atttention towards his erectile response would trigger sexual performance thoughts and possibly create an atmosphere of viewing oneself from a third party perspective. In women, however, sexual performance anxiety may have little to do with a physiological (i.e., genital vasocongestive) sexual response. Not withstanding the fact that lack of genital lubrication may contribute to the etiology of sexual pain in women (e.g., van Lunsen & Laan, 2004), anatomically, women differ from men in that they do not need to produce a physiological response in order to engage in sexual intercourse. Research examining relations between self-reports of sexual arousal and genital engorgement in women indicate correlations much lower than correlations noted in men between self-reported arousal and erectile responses (for review, see Meston, 2000). This, coupled with the fact that women are generally poorer than men at estimating bodily changes (for review, see Pennebaker & Roberts, 1992) suggests genital responding may be less of a focus for women and play less of a role in what constitutes sexual performance than it does for men. If so, factors such as mood, relationship factors, body image, and self-esteem may be more relevant indicators of sexual confidence/performance in women. Qualitative research that focuses on asking women about their sexual fears and performance concerns may help to inform the field of how to effectively measure the construct of spectatoring in women.

With regard to trait measures of self-consciousness and sexual function, a number of interesting trends emerged. Private self-consciousness was positively related to measures of sexual desire, orgasm, satisfaction, contentment, and compatibility. Public self-consciousness was unrelated to any of these measures, but was associated with sexual pain such that individuals high in public self-consciousness also reported higher levels of sexual pain. The dichotomous findings for public and private self-consciousness traits is consistent with past research that indicates when one of these traits has a significant impact on behavior, the other does not (Buss, 2001). It was predicted that persons high in private self-consciousness by definition would be more focused inwardly on physical sensations, and that this would be a beneficial trait for sexual responding. The findings for sexual desire and orgasm noted above support this prediction. The finding that private, but not public, self-consciousness was related to measures of sexual satisfaction is consistent with findings from a study on dispositional self-consciousness and erectile function in males (Fichen, Libman, Takefman, & Brender, 1988). Fichen and associates noted a significant positive relation between private self-consciousness, measured using the same scale as that used in the present study, and relationship satisfaction. It is unclear why the tendency to be introspective is related to relationship and sexual satisfaction. The literature suggests that individuals with a tendency to focus inward tend towards an intensification of both positive and negative emotions (Buss, 2001). To the extent that such individuals are in a good relationship, this trait may be expected to enhance emotional bonding and sexual satisfaction. In problematic relationships, however, this trait might be expected to negatively impact such factors. Unfortunately marital adjustment was not assessed in this study and, therefore, this hypothesis could not be tested.

Persons high in public self-consciousness showed a trend towards lower levels of physiological sexual arousal in the self-focus versus no self-focus condition, and persons low in public self-consciousness showed a trend in the opposite direction. These preliminary findings are partially consistent with recent findings in men which noted a similar relationship between both public and private self-consciousness and erectile responding (van Lankveld et al., 2004). Van Lankveld et al. (2004) explained these findings in men in terms of an inverted curvilinear relationship between self-focused attention and genital arousal. The authors speculated that state self-focused attention and trait self-consciousness may act cumulatively to either enhance or impair genital responding depending on whether an optimal or suboptimal level of attentional focus is attained. While the findings in women represent an interesting trend worthy of further study, the small sample size and exploratory nature of these findings render any conclusions highly speculative.

In conclusion, the findings from this study, though limited by the relatively small sample size, provide preliminary evidence for a role of both state and trait self-consciousness in female sexual function. The degree to which factors such as body image, self-esteem, affect, and relationship satisfaction mediate these relationships warrants further investigation.

Acknowledgements

This publication was made possible by Grant Number 5 RO1 AT00224-02 from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the author and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. The author would like to thank Kendra Orjada for her assistance in data collection and Dr. Arnie Buss for his helpful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript.

References

- Adams AE, Haynes SN, Brayer MA. Cognitive distraction in female sexual arousal. Psychophysiology. 1985;22:689–696. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1985.tb01669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed., Text revision. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH. Causes of sexual dysfunction: The role of anxiety and cognitive interference. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1986;54:140–148. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.54.2.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck JG, Barlow DH. The effects of anxiety and attentional focus on sexual responding—I: Physiological patterns in erectile dysfunction. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1986;24:9–17. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(86)90144-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck JG, Barlow DH, Sakheim DK. The effects of attentional focus and partner arousal on sexual responding in functional and dysfunctional men. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1983;21:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(83)90120-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss A. Psychological dimensions of the self. California: Sage Publications; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF. Self-focusing effects of dispositional self-consciousness, mirror presence, and audience presence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1978;36:324–332. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR. Derogatis sexual functioning inventory. Revised ed. Baltimore, MD: Clinical Psychometrics Research; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Dove NL, Wiederman MW. Cognitive distraction and women’s sexual functioning. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 2000;26:67–78. doi: 10.1080/009262300278650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duval S, Wicklund RA. A theory of objective self-awareness. New York: Academic Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott AN, O’Donohue WT. The effects of anxiety and distraction on sexual arousal in a nonclinical sample of heterosexual women. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1997;26:607–624. doi: 10.1023/a:1024524326105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exner JE., Jr The self-focus sentence completion: A study of egocentricity. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1973;37:437–455. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1973.10119902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenigstein A, Scheier MF, Buss AH. Private and public self-consciousness: Assessment and theory. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1975;43:522–527. [Google Scholar]

- Fichen CS, Libman E, Takefman J, Brender W. Self-monitoring and sexual-focus in erectile dysfunction. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 1988;14:120–128. doi: 10.1080/00926238808403912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiman JR, Meston CM. Rosen RC, Davis CM, Ruppel HJ, editors. Empirically validated treatments for sexual dysfunction. Mason City, IA: The Society for the Scientific Study of Sexuality; Annual review of sex research: An integrative and interdisciplinary review 1997. 1998;Vol. 8:148–194. [PubMed]

- Heiman JR, Rowland DL. Affective and physiological sexual response patterns: The effects of instructions on sexually functional and dysfunctional men. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1983;27:105–116. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(83)90086-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram R. Self-focused attention in clinical disorders: Review and a conceptual model. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:156–176. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korff J, Geer JH. The relationship between sexual arousal experience and genital response. Psychophysiology. 1983;20:121–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1983.tb03276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koukounas E, McCabe M. Sexual and emotional variables influencing sexual response to erotica. Behavior Research and Therapy. 1997;35:221–230. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(96)00097-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laan E, Everaerd W, van Aanhold MT, Rebel M. Performance demand and sexual arousal in women. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1998;31:25–35. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(93)90039-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange JD, Wincze JP, Zwick W, Feldman S, Hughes K. Effects of demand for performance, self-monitoring of arousal, and increased sympathetic nervous system activity on male erectile response. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1981;10:443–464. doi: 10.1007/BF01541436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masters WH, Johnson VE. Human sexual inadequacy. Boston: Little, Brown; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Meston CM. The psychophysiological assessment of female sexual function. Journal of Sex Education and Therapy. 2000;25:6–16. [Google Scholar]

- Meston CM. Validation of the female sexual function index (FSFI) in women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder and in women with female orgasmic disorder. Journal of Sexual and Marital Therapy. 2003 doi: 10.1080/713847100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meston CM, Gorzalka BB. The effects of immediate, delayed, and residual sympathetic activation on physiological and subjective sexual arousal in women. Behavior Research and Therapy. 1996;34:143–148. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00050-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meston CM, Heiman JR. Ephedrine-activated sexual arousal in women. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:652–656. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.7.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meston CM, McCall K. Dopamine and norepinephrine response to sexual arousal in sexually functional and dysfunctional women. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 2005;31:1–15. doi: 10.1080/00926230590950217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meston CM, Trapnell PD. Development and validation of a five factor sexual satisfaction and distress scale: The Sexual Satisfaction Scale for Women (SSS-W) Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2005;2:66–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.20107.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW, Francis ME, Booth RJ. Linguistic inquiry in word count: LIWC 2001. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW, Roberts TA. Toward a his and hers theory of emotion: Gender differences in visceral perception. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1992;11:199–212. [Google Scholar]

- Przybyla DPJ, Byrne D. The mediating role of cognitive processes in self-reported sexual arousal. Journal of Research in Personality. 1984;18:43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, Leiblum S, Meston CM, Shabsigh R, Ferguson D, D’Agostino R., Jr The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 2000;26:191–208. doi: 10.1080/009262300278597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakheim DK, Barlow DH, Beck JG, Abrahamson DJ. The effect of an increased awareness of erectile cues on sexual arousal. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1984;22:151–158. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(84)90103-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sintchak G, Geer JH. A vaginal plethysmograph system. Psychophysiology. 1975;12:113–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1975.tb03074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Lankveld JJDM, van den Hout MA, Schouten EGW. The effects of self-focused attention, performance demand, and dispositional sexual self-consciousness on sexual arousal of sexually functional and dysfunctional men. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2004;42:915–935. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Lunsen RH, Laan E. Genital vascular responsiveness and sexual feelings in midlife women: Psychophysiologic, brain, and genital imaging studies. Menopause. 2004;11:741–748. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000143704.48324.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiegel M, Meston CM, Rosen R. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): Cross-Validation and Development of Clinical Cutoff Scores. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 2005;31:1–20. doi: 10.1080/00926230590475206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wincze JP, Venditti E, Barlow DH, Mavissakalian M. The effects of a subjective monitoring task in the physiological measure of genital response to erotic stimulation. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1980;9:533–545. doi: 10.1007/BF01542157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]