Abstract

Objectives

Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) is a product of cyclooxygenase (COX) and prostaglandin E synthase (PGES) and deactivated by 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase (PGDH). Down-regulation of PGDH contributes to PGE2 accumulation in lung and colon cancers but has not been identified in pancreatic cancer.

Methods

Human pancreatic normal and tumor matched tissues as well as MiaPaCa-2 and BxPC-3 cell lines were assessed for COX-2, mPGES-1, PGDH, SNAI1 and SNAI2 expression by RT-PCR and Western blotting and PGE2 by ELISA.

Results

Normal tissues exhibited low COX-2 mRNA and protein expression, high PGDH mRNA and protein expression and PGE2 levels at 13 pg/mg protein. In contrast, tumor tissues exhibited high COX-2 mRNA and protein expression, low PGDH mRNA and protein expression and PGE2 levels at 32 pg/mg protein. Tumor tissues exhibited significantly elevated expression of SNAI2 mRNA and protein but not SNAI1 as SNAI1 and SNAI2 reportedly down-regulate PGDH expression. COX-2-positive BxPC-3 but not COX-2-negative MiaPaCa-2 treated with 100 nM of PGE2 induced pERK that was blocked by MEK inhibitor U0126, demonstrating the ability of PGE2 to activate ERK.

Conclusions

These results suggest that enhanced PGE2 production proceeds through the expression of COX-2 and mPGES-1 and down-regulation of PGDH by SNAI2 in pancreatic tumors.

Keywords: prostaglandin E2, cyclooxygenase-2, 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase, microsomal prostaglandin E synthase, SNAI2

INTRODUCTION

Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) exerts pleiotropic biological effects on a variety of cells and tissue.1 Excess levels of PGE2 are implicated in mediating several types of human malignancies, including pancreatic cancer.2,3 PGE2 mediates angiogenesis in promoting endothelial cell migration, capillary morphogenesis and vascular endothelial growth factor expression in pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells as well as neovascularization in vivo.4,5 PGE2 biosynthesis is controlled at cyclooxygenase (COX) conversion of arachidonic acid to PGH2.6 COX encompasses a constitutive COX-1 and an inducible COX-2 isoform that are structurally similar but differ in their transcriptional regulation.7 COX-2 is an immediate-early response gene activated by growth factors, cytokines and other factors and is over-expressed in pancreatic cancers.8,9 Prostaglandin E synthase (PGES) converts PGH2 to PGE2 and consists of a constitutive cytosolic (cPGES) and an inducible membrane-associated (mPGES) isoforms.5 Interestingly, induction of COX-2 parallels the induction of mPGES-1, suggesting that COX-2 and mPGES-1 share similar regulatory mechanisms.1,10 Transcriptional regulation of COX-2 and mPGES-1 appear to involve mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling, resulting in COX-2 expression, mPGES-1 expression and elevated PGE2.11,12

Catabolism of PGE2 proceeds with the initial oxidation by 15(S)-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase (PGDH) to a biologically inactive 15-keto PGE2.13 Type I NAD+-dependent PGDH is considered the key enzyme for the inactivation of prostaglandins and its loss of expression has been identified in bladder, thyroid and colon cancer.14–16 PGDH is present in normal intestine and down-regulated in several carcinoma cell lines.17,18 Inhibition of MAPK signaling elevates PGDH expression that also parallels a decrease in transcriptional repressors ZEB1, SNAI1 and SNAI2.19–21 The regulation of PGDH in conjunction with COX-2/mPGES-1 production of PGE2 is unclear but appears to converge on MAPK signaling, suggesting elevated PGE2 may result from the coupled up-regulation of COX-2 and mPGES-1 with simultaneous or subsequent down-regulation of PGDH.

Thus, the aim of this report was to demonstrate that elevated PGE2 levels stem not only from the presence of COX-2 over-expression but also, at least in part, from the absence of PGDH expression in pancreatic cancer. Human pancreatic normal tissues exhibited decreased COX-2 expression with increased Type 1 PGDH expression that corresponded with low PGE2 levels. In contrast, pair-matched tumor tissues exhibited increased COX-2 expression with decreased PGDH expression that corresponded with elevated PGE2 levels. Similarly, human pancreatic cancer cells expressing COX-2 but not PGDH exhibited increased PGE2. The human pancreatic tumors expressed significantly elevated SNAI2 but not SNAI1, although both these transcriptional repressors reportedly down-regulate PGDH expression. These results suggest accumulated levels of PGE2 feed-forward inducing further COX-2-mediated PGE2 production and down-regulating PGDH expression that appear to proceed through ERK activation and SNAI2 expression in pancreatic cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

FBS, DMSO, chloroform and methanol were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). The selective COX-2 inhibitor N-[2-(cyclohexyloxy)-4-nitrophenyl]-methanesulfonamide (NS-398), non-selective COX inhibitor indomethacin, PGE2, COX-2 antibody and PGDH antibody were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). SNAI1 and SNAI2 antibodies were purchased from Abgent (San Diego, CA). Phosphorylated ERK (p-ERK) and β-actin antibodies were acquired from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG or anti- mouse IgG and ECL reagents were obtained from Amersham-Pharmacia (Piscataway, NJ). The MEK specific inhibitor U0126 was obtained from Calbiochem (EMD Biosciences, San Diego, CA).

Human Pancreatic Tissues

Human pancreatic tumor tissues from surgical resections were frozen and stored in liquid nitrogen. Each donor tumor sample was matched with adjacent normal tissue collected during the process. All tumors were ductal adenocarcinoma. No IPMN (intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm), cystic lesions or other. Pancreatic specimens were dissected macroscopically by trained pathologists. Tumor was sectioned as well as 'normal' pancreatic tissue from a region of pancreas included in the surgical specimen that was not grossly affected by tumor and was located as far away from the tumor mass as was feasible. Many slides of 'normal' pancreas included PanIN (pancreatic intraductal neoplasia) or chronic pancreatitis. These tissue samples were obtained from the UCLA Pancreas Tumor Bank supported by the Hirshberg Foundation for Pancreatic Cancer Research. These clinical specimens were reviewed and categorized by a pathologist before analyses. This human protocol was approved by the University of California at Los Angeles Internal Review Board.

Cell Culture

Human pancreatic cell lines MiaPaCa-2 (CRL 1420) and BxPC-3 (CRL 1687) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). Stock cultures of MiaPaCa-2 were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 4 mM L-glutamine, 1.5 g/L sodium bicarbonate, and 4.5 g/L glucose, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and PSG antibiotic mix (100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine; Invitrogen). Stock cultures of BxPC-3 were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium containing 2 mM L-glutamine, 2.0 g/L sodium bicarbonate, and 2.0 g/L glucose, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and PSG antibiotic mix (100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine; Invitrogen). MiaPaCa-2 cells, maintained in a humidified atmosphere with 10 % CO2 at 37 °C, and BxPC-3 cells, maintained in a humidified atmosphere with 5 % CO2 at 37 °C, were passaged weekly. For experiments, these cells were plated in 100-mm tissue culture dishes and allowed to achieve confluence (5–7 days) before use. Media of confluent MiaPaCa-2 or BxPC-3 cells were then exchanged for serum-free DMEM medium or serum-free RPMI medium, respectively, overnight.

RNA Extraction

For tissue RNA extraction, human pancreatic tissues were frozen in liquid nitrogen, grounded to powder using a mortal and pestle and harvested with 1 ml of Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in 1.5 mL eppendorf tubes. For cell culture, cells were washed with 4 ml of Versene containing 0.48 mM EDTA in phosphate-buffered saline (Invitrogen) and harvested with 1 ml of Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). Total RNA was extracted with 0.2 ml of chloroform at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C and precipitated with 0.5 ml of 2-propanol at 12,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4 °C. The RNA pellet was washed with 75% ethanol at 7,500 × g for 5 minutes at 4 °C, dissolved in 30 µL of RNA Storage Solution with 1 mM sodium citrate, pH 6.4 (Ambion, Austin, TX) and stored at −20 °C for subsequent analysis. RNA concentration was quantified on a spectrophotometer (GeneQuant Pro, Amersham Biotechnology, Piscataway, NJ) reading dual wavelengths of 260 and 280 nm.

Tissue Protein Extraction

Human pancreatic tissue samples (0.1 g) were homogenized in 1 mL of PBS containing protease inhibitor cocktail (cat 11 697 498 001, Roche, Indianapolis, IN) carried out on ice. Tissue homogenates were sonicated for 20 seconds at 60 hz before centrifuging at 800 × g for 10 minutes at 4 °C. The supernatants were filtered through 0.8 µm filter and protein concentration was determined by absorbance at 595 nm using the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Real Time PCR (RT-PCR)

Total RNA samples (25 ng) are reverse transcribed and cDNAs amplified using TaqMan Gold RT-PCR kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Transcripts encoding human COX-2, mPGES-1, PGDH, SNAI1, SNAI2 and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as an internal control were quantified by real-time PCR analysis using an ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detection System (PE Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The human primers used are as follows: COX-2 sense 5’-GGC TCA AAC ATG ATG TTT GCA-3’, antisense 5’-CCT CGC TTA TGA TCT GTC TTG A-3’ with corresponding probe 5’-TCT TTG CCC AGC ACT TCA CGC ATC AGT TT-3’; mPGES-1 sense 5’-AGA GAT GCC TGC CCA CAG-3’, antisense 5’-CCA CGT ACA TCT TGA TGA CCA -3’ with Universal Probe 9: 5’-TTG TGA TG-3’ (Roche); SNAI1 sense 5’-GCT GCA GGA CTC TAA TCC AGA-3’, antisense 5’-ATC TCC GGA GGT GGG ATG-3’with corresponding Universal Probe 66: 5’-CAG CAG CC-3’ (Roche); SNAI2 sense 5’-TGG TTG CTT CAA GGA CAC AT-3’, antisense 5’-GTT GCA GTG AGG GCA AGA A-3’ with corresponding universal probe 7: 5’-GGG AGA G-3’ and PGDH sense 5’-GAA GGC GGC ATC ATT ATC AA-3’, antisense 5’-GCC ATG CTT TGA AGC ACA A-3’ with corresponding Universal Probe 66: 5’-CAG CAG CC-3’. The human GAPDH primer and probe set was acquired from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). Thermal cycling conditions for reverse transcription and amplification activation were set at 50 °C for 30 minutes and 95 °C for 10 minutes, respectively. PCR denaturing was set at 95 °C at 15 seconds and annealing/extending at 60 °C at 60 seconds for 40 cycles, according manufacturer’s protocol (Brilliant II, Stratagene, La Jolla, CA).

Protein Expression

For tissue samples, protein extracts from tissue samples were with diluted 1:1 (vol/vol) with 2× LDS buffer containing SDS (Invitrogen) and denatured at 95 °C for 10 minutes in a water bath. For cell culture, confluent, serum-starved cells were washed with 1 ml of ice-cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS, Sigma), harvested in LDS loading buffer and denatured at 95 °C for 10 minutes in a water bath. These protein extracts were subjected to a variable 4–12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (NuPAGE Novex Bis-Tris Gels, Invitrogen) for 45 minutes at 200 V, and transferred to a PVDF membrane (90 min at 30 V). The membrane was washed with Tris buffered saline (TBS, Sigma), blocked with 5% dried nonfat milk and 5% BSA in 1% tween-TBS and probed with antibody raised against either COX-2, PGDH, SNAI1, SNAI2 or p-ERK (1:1000) followed by antibody IgG linked to horseradish peroxidase conjugate (1:2500) according to the manufacturer's protocol (Cayman Chemicals). The blot was visualized by enhanced chemoluminescence (Amersham Biosciences). For internal standards, the blot was stripped with Restore Western Blot stripping buffer (Pierce, Rockford, IL), probed for β-actin (1:2500) as the internal standard and visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence.

Prostaglandin E2 Levels

PGE2 was quantified from serum-starved, confluent cells cultured in 24-well plates or from human tissue protein extracts according to EIA kit instructions (STAT-Prostaglandin E2 EIA kit and STAT-Prostaglandin F1α EIA kit, Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI). PGE2 determination was enhanced using total lipid extraction with chloroform/methanol (2:1, vol/vol).22 Absorbance readings were set between 405–420 nm on a spectrophotometer. PGE2 levels were normalized to protein concentration measured by absorbance at 595 nm using the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad).

Statistical Analyses

Data are expressed as means ± SEM. Two-way ANOVA was performed using Sigma Plot (SPSS, Chicago, IL) and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Increased COX-2 and mPGES-1 mRNA Coupled with Decreased PGDH mRNA Expression in Pancreatic Tumors

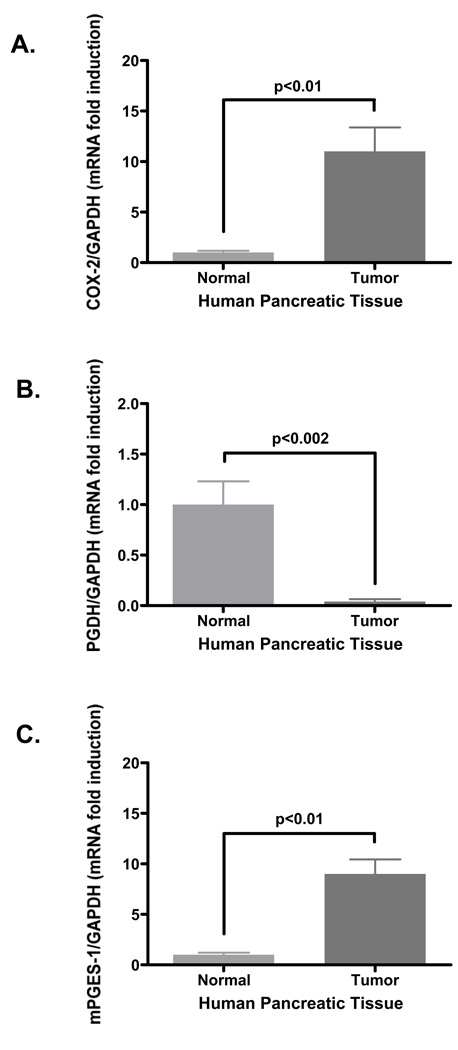

Human pair-matched pancreatic normal and tumor samples were extracted for total RNA. These RNA extracts were reverse-transcribed for human COX-2, PGDH and GAPDH expression. Pooled Ct values of COX-2 expression from normal and tumor samples were normalized to the housekeeping gene GAPDH as shown in Fig. 1A. The pancreatic tumor samples expressed 11.0 ± 2.4 fold-increase in COX-2 mRNA expression compared to normal pancreatic tissue at 1.0 ± 0.2 fold COX-2 expression. In contrast, tumor tissue expressed only 0.04 ± 0.002 fold PGDH mRNA compared to normal pancreatic tissue at 1.0 ± 0.1 fold PGDH mRNA shown in Fig. 1B. Additionally, since COX-2 and mPGES-1 seemingly co-express to generate PGE2, mPGES-1 mRNA expression was assessed by RT-PCR using the same RNA samples. Pooled pancreatic tumor samples expressed 9.0 ± 1.4 fold-increase in mPGES-1 mRNA expression compared to normal pancreatic tissue at 1.0 ± 0.1 fold mPGES-1 expression (Fig. 1C). These findings show an inverse relationship between the COX-2 and the degradative PGDH enzyme as well as an inverse relationship between mPGES-1 and PGDH at the mRNA expression level in pancreatic tissue. The marked fold difference in PGDH mRNA expression of tumor tissue compared to normal tissue suggests a more pronounced role for PGDH in maintaining PGE2 levels.

Figure 1. COX-2 and mPGES-1 mRNA expression is increased in human pancreatic tumors.

Human pair-matched normal and tumor samples were extracted for total RNA using Trizol reagent as detailed in the Methods section. RNA samples (25 ng per sample) were reverse-transcribed and probed for human (A) COX-2, (B) PGDH, (C) mPGES-1 and GAPDH as an internal standard. Raw Ct values were normalized to GAPDH and data represented as mean fold induction ± SEM.

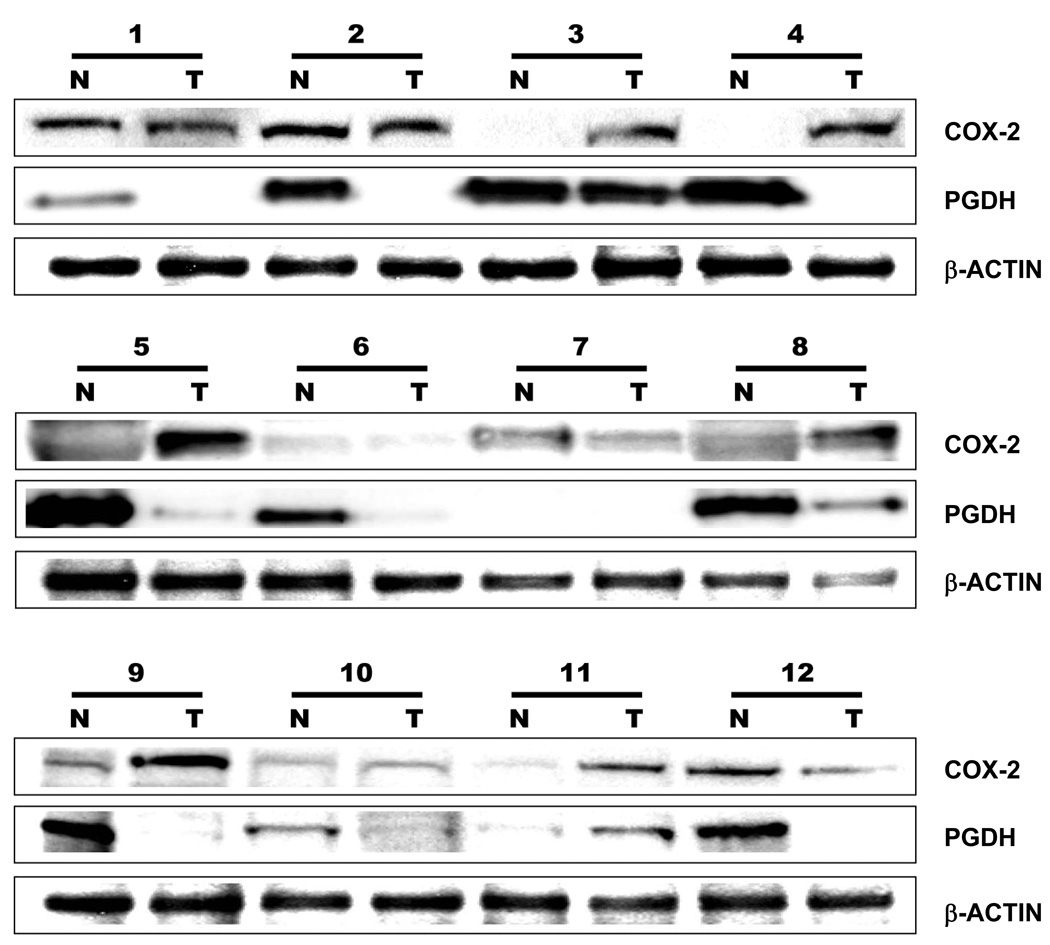

Increased COX-2 Protein Expression Coupled with Decreased PGDH Protein Expression in Human Pancreatic Tumors

To confirm whether the COX-2 and PGDH mRNA expression also correlates with the COX-2 and PGDH protein expression, the human pair-matched normal and tumor tissues were homogenized and filtered for protein analysis as described in detail under the Methods section. The pair-matched samples were resolved by gel electrophoresis loaded at 45 µg per lane and transferred onto a PDVF membrane. The membranes were probed for COX-2 and PGDH with β-actin for visual loading control as shown in Fig. 2. Densometric assessment (data not shown) of the blots showed that ten (83 %) of the twelve pancreatic tumor samples exhibited COX-2 expression (case 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 11 and 12) whereas six of the twelve (50 %) normal samples exhibited COX-2 expression (case 1, 2, 7, 9, 10 and 12). In contrast to the increased COX-2 expression exhibited by the tumor samples, PGDH expression was lost in most of the tumor samples. Of the twelve pancreatic tumor samples, only three tumor samples (25 %) exhibited PGDH expression (case 3, 8 and 11). The normal pancreatic tissue samples, however, expressed PDGH in ten (83 %) of the twelve samples (case 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10 and 12).

Figure 2. Increased COX-2 is coupled with decreased PGDH expression in human pancreatic tumors.

Pair-matched human pancreatic normal (N) and tumor (T) samples were processed for protein expression as detailed under Methods section. Protein samples loaded at 45 µg of sample/lane were resolved by PAGE, Western blotted for COX-2 (1:1000) and PGDH (1:1000) with β-actin (1:2500) as visual loading control, visualized by chemiluminescence (ECL) and recorded using a luminescent image analyzer.

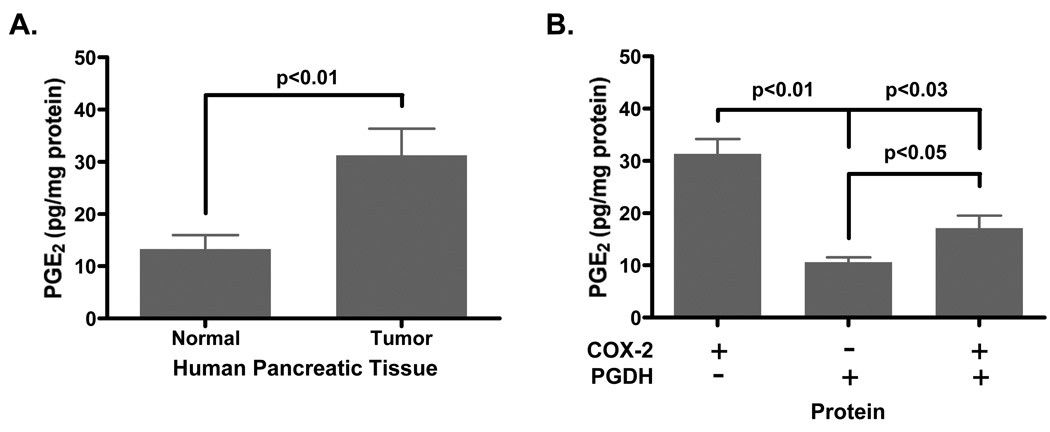

Human Pancreatic Tumors Express Increased PGE2

Based on the COX-2 and PGDH expression results, lysates from the human pair-matched pancreatic normal and tumorigenic tissues were lipid extracted to assay for PGE2 levels. Fig. 3A shows elevated PGE2 levels in the tumorigenic tissues at 31.3 ± 5.1 pg/mg in comparison to normal tissues at 13.3 ± 2.7 pg/mg protein. In the presence or absence of COX-2 and PGDH protein expression (Fig. 3B), samples that expressed only PGDH but not COX-2 protein exhibited the lowest PGE2 level at 10.6 ± 0.9 pg/mg protein. Samples that expressed only COX-2 but not PGDH protein exhibited the highest PGE2 level at 31.36 ± 2.9 pg/mg protein. Samples expressing both COX-2 and PGDH protein exhibited moderate PGE2 levels at 17.1 ± 2.4 pg/mg protein that was significantly lower than COX-2 expressing samples alone and significantly higher than PGDH expressing samples alone. This finding demonstrates control of PGE2 levels could be achieved through PGDH expression and activity and suggests that a combination of both COX-2 inhibition and PGDH induction could abolish PGE2 production in carcinogenesis.

Figure 3. Prostaglandin E2 levels are elevated in human pancreatic tumors.

Human pair-matched normal and tumor samples were homogenized, sonicated, centrifuged and filtered yielding protein lysates as detailed in the Methods section. These lysates were lipid extracted and assayed for PGE2 by EIA as outlined in the manufacturer’s protocol. (A) Comparison of mean PGE2 levels from normal and tumor tissues are standardized to protein concentration as determined by the Bradford assay. (B) Mean PGE2 levels from only COX-2-expressing, only PGDH-expressing or both COX-2/PGDH-expressing human samples are standardized to protein concentration.

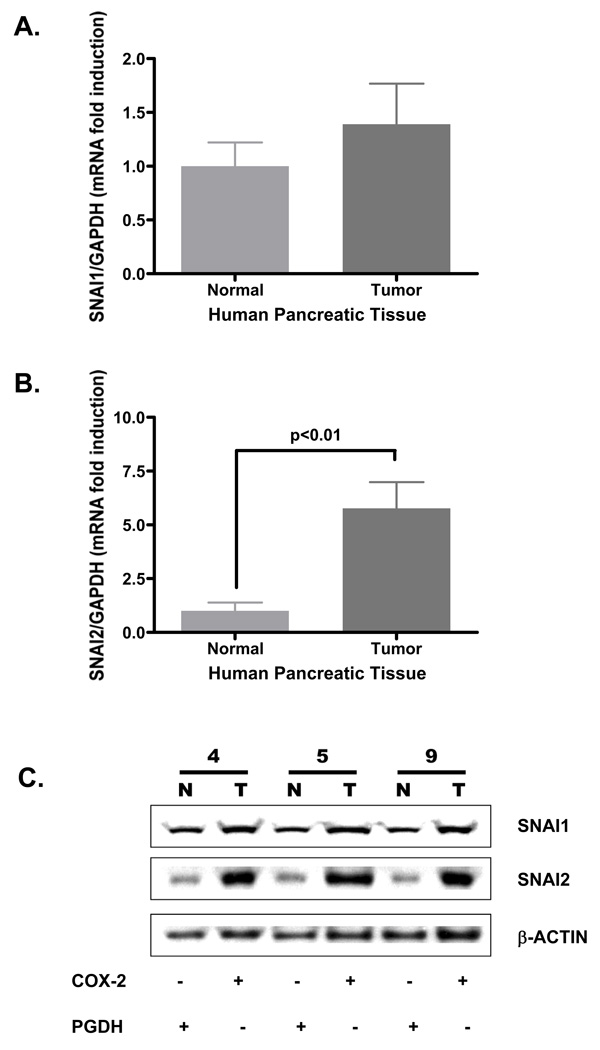

Slug Expression Is Increased in Human Pancreatic Tumors

To develop a possible explanation for the down-regulation of PGDH in the pancreatic tumors, the human pair-matched pancreatic normal and tumor samples were processed for mRNA and protein expression of SNAI1 (Snail) and SNAI2 (Slug) as these nuclear transcription factors, particularly Slug, have been identified as a repressor of PGDH expression.21,23,24 Expression of SNAI1 mRNA in normal tissue at 1.0 ± 0.2 fold induction was not significantly different from that of tumor tissue at 1.4 ± 0.3 fold induction, shown in Fig. 4A. However, SNAI2 (Slug) mRNA expression in tumor tissue at 5.8 ± 0.9 fold induction was significantly higher than normal tissue at 1.0 ± 0.3 (Fig. 4B). To determine if the mRNA expression profile paralleled with the protein profile, pair-matched human pancreatic normal and tumor tissue protein extracts were probed for SNAI1, SNAI2 and β-actin protein expression shown in Fig. 4C. The pair-matched sample 4N with 4T, 5N with 5T and 9N with 9T were used as 4N, 5N and 9N exhibited robust PGDH expression with minimal COX-2 expression (Fig. 2). Similarly, 4T, 5T and 9T tumor samples exhibited marked COX-2 expression with minimal PDGH expression (Fig. 2). Both the normal and tumor tissue samples (pair-matched samples 4, 5 and 9) expressed SNAI1 (Fig. 4C). SNAI2, however, was markedly expressed in the tumor samples (4T, 5T and 9T) whereas SNAI2 was minimally expressed in the normal tissue samples (4N, 5N and 9N). Both SNAI1 and SNAI2 mRNA expression profile paralleled the SNAI1 and SNAI2 protein expression profiles. Interestingly, however, the increased SNAI2 expression in the tumor sample paralleled increased COX-2 expression but correlated with low PGDH expression. The correlation of the increased Slug expression with decreased PGDH expression in the tumor samples suggests the possibility of Slug-induced down-regulation of PGDH expression as have been reported in other epithelial systems.24,25

Figure 4. SNAI2 (Slug) mRNA and protein expression is increased in human pancreatic tumors.

Human pair-matched normal and tumor samples were extracted for total RNA using Trizol reagent detailed in the Methods section. RNA samples were reverse-transcribed and probed for human (A) SNAI1 (Snail), (B) SNAI2 (Slug) and GAPDH as an internal standard. Raw Ct values were standardized to GAPDH and data represented as mean fold induction ± SEM. Pair-matched human pancreatic normal (N) and tumor (T) samples were processed for protein expression as detailed under Methods section. (C) Protein from samples 4N, 4T, 5N, 5T, 9N and 9T were loaded at 45 µg/lane per sample, resolved by PAGE, Western blotted for SNAI1 (1:1000) and SNAI2 (Slug) (1:1000) with β-actin (1:2500) as visual loading control, visualized by chemiluminescence (ECL) and recorded using a luminescent image analyzer.

PGE2 Stimulates ERK Phosphorylation in COX-2+ BxPC-3 Cells

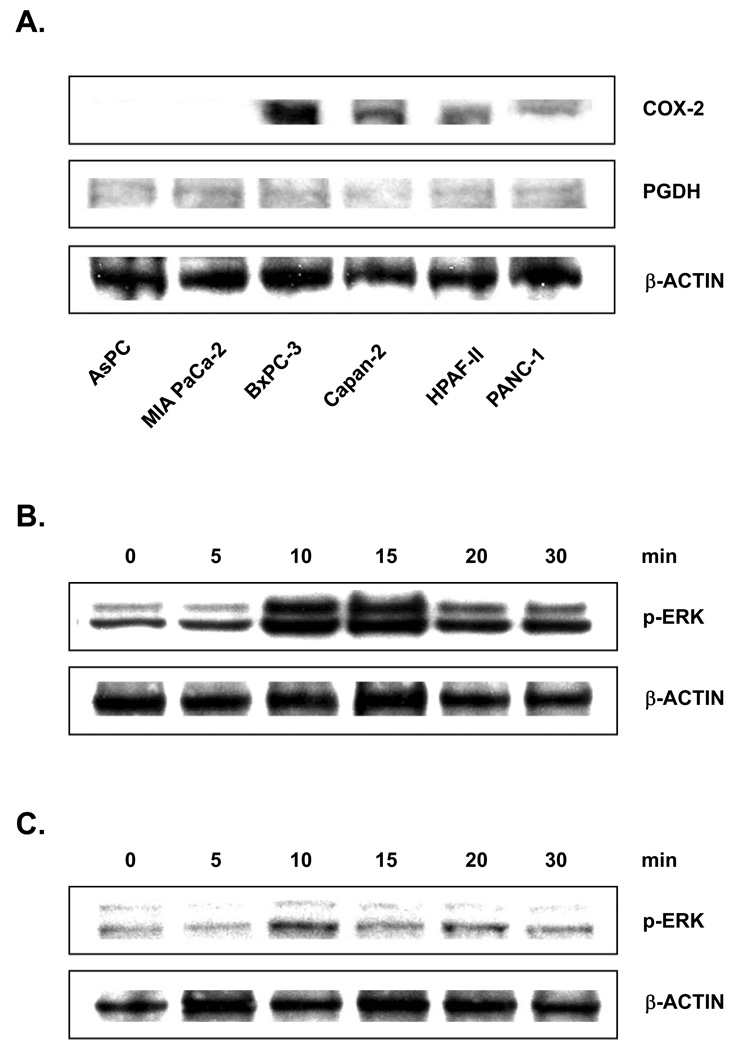

To further demonstrate the reciprocal expression of COX-2 and PGDH, six human pancreatic carcinoma cell lines were assessed for COX-2 and PGDH expression. Fig. 5A shows COX-2 expression for AsPC, MiaPaCa-2, BxPC-3, Capan-2, HPAF-II and Panc-1 with β-actin as a visual loading control. None of the cell lines expressed PGDH. Based on this COX-2 profile in this report and previous report, MiaPaCa-2 as a COX-2 negative (COX-2−) and BxPC-3 as a COX-2 positive (COX-2+) cell lines were used to test their response to PGE2.26 The COX-2- MiaPaCa-2 treated with PGE2 did not induce phosphorylated ERK expression, suggesting that this particularly cell line may not express PGE2 receptors or expresses limited PGE2 receptors to elicit detectable signaling differences. Only COX-2+ BxPC-3 responded to a physiological dosage of 100 nM of PGE2 as indicated in Fig. 5B. Induction of ERK phosphoryation peaked at 15 minutes and decreased at 20 and 30 minutes. Pre-treatment with 100 nM of MEK1/2 inhibitor U0126 for 1 hour followed subsequently with 100 nM of PGE2 challenge to COX-2+ BxPC-3 cells abolished the ERK phosphorylation (Fig. 5C) that was observed without U0126. These findings suggests a possible mechanism by which elevated PGE2 levels continue to accumulate by activating the MAPK cascade to down-regulate PGDH expression through the induction of SNAI2 expression.

Figure 5. Human pancreatic cell lines express COX-2 but not PGDH.

(A) Subconfluent human pancreatic cell lines AsPC, MiaPaCa-2, BxPC-3, Capan-2, HPAF-II and Panc-1 were processed for protein expression as detailed under Methods section. Protein samples from cell extracts loaded at 45 µg of sample/lane were resolved by PAGE, Western blotted for COX-2 (1:1000) and PGDH (1:1000) with β-actin (1:2500) as visual loading control, visualized by chemiluminescence (ECL) and recorded using a luminescent image analyzer. (B) COX-2 positive BxPC-3 cells treated with 100 nM of PGE2 for 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, or 30 min were harvested for protein expression. Protein extracts loaded at 45 µg of sample/lane resolved by PAGE, Western blotted for phosphorylated ERK (p-ERK) (1:1000) with β-actin (1:2500) as visual loading control, visualized by ECL and recorded using a luminescent image analyzer. (C) COX-2 positive BxPC-3 cells were incubated with MEK inhibitor U0126 (100 nM) for 1 hr. BxPC-3 cells were then treated with 100 nM of PGE2 for 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, or 30 minutes and harvested for protein expression. Protein extracts loaded at 45 µg of sample/lane were resolved by PAGE, Western blotted for phosphorylated ERK (p-ERK) (1:1000) with β-actin (1:2500) as visual loading control, visualized by ECL and recorded using a luminescent image analyzer.

DISCUSSION

Overall, this study shows that elevated PGE2 levels in human pancreatic cancer tissue result from a seemingly coupled increase in COX-2 and mPGES-1 expression that is further maximized by a decrease in PGDH expression. Elevated PGE2 levels correlated with increased COX-2 mRNA and protein expression in cancer tissue, consistent with prior reports of increased PGE2 in pancreatic cancers.4,26 Over-expression of COX-2 has been documented in human pancreatic carcinomas and adenocarcinomas.9,28,29 COX-2 over-expression appears to extend to human pancreatic cancer cell lines as well.9,26,30 Indeed, the identification of COX-2 over-expression in pancreatic cancers has prompted several studies inhibiting COX-2 and production of PGE2 as a therapeutic adjuvant in combination with gemcitabine standard for pancreatic cancer treatment.31–33 Additionally, the increased PGE2 levels have been linked directly to COX-2 expression that paralleled similar increased mPGES-1 and -2 expression in pancreatic cancer tissue and cells.26,27 Maximal PGE2 levels were observed in pancreatic tissue expressing only COX-2 and not PGDH as shown in Fig. 3, suggesting the importance of down-regulating PGDH in pancreatic tumors resulting in the accumulated PGE2 levels.

In the context of enhanced PGE2 production in pancreatic tumorigenesis, the contribution and regulation of PGDH has not been fully investigated. Studies on the regulation of PGDH have been limited to lung and colon cancer, but have contributed in understanding the mechanism.16,24 These reports on the regulation of PGDH have identified several transcriptional repressors, including SNAI1 (Snail) and SNAI2 (Slug), that interact with the E-box element of the PGDH promoter.17 This study also confirms the presence of Snail and Slug repressors in pancreatic tissue. Moreover, the findings showed that Snail mRNA expression was not significantly different in pancreatic normal and matched tumor samples but that pancreatic tumor samples exhibited significantly robust expression of Slug mRNA (Fig. 4A and 4B). Determination of Snail and Slug protein expression in three human pair-matched normal and tumor samples revealed similar pattern observed with the mRNA expression. Snail expression was not significantly different between normal and tumor but Slug expression was significantly augmented in the tumor samples that also exhibited pronounced COX-2 expression (Fig. 4C). This finding was consistent with a report demonstrating Slug expression and binding to the PGDH promoter in lung carcinoma cells19 but contrasted the report of enhanced expression of Snail exhibited by human colon cancer cell,25 suggesting that PGDH regulation could be mediated by cell or tissue-specific mechanism utilizing specific transcriptional repressors.

Both transcriptional repressors Snail and Slug expression are regulated through the MEK/ERK pathway, prompting the question whether excess PGE2 might activate MEK/ERK in expressing Slug expression in the pancreatic cancer. Targeting of EGFR signaling through MAPK using the EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor erlotinib or the MEK-specific small molecule inhibitor U0126 elevates PGDH expression in human lung cancer cells.19 Inhibition of MAPK suppresses transcriptional repressors ZEB1, SNAI1 and SNAI2, with only SNAI2 (Slug) shown to bind to an E-box element upstream of the TATA box and start site of PGDH.19–21 In addressing a possible mechanism for the down-regulation of PGDH in the pancreatic cancer, two human pancreatic cell lines the COX-2− MiaPaCa-2 and the COX-2+ BxPC-3 were exposed to excess PGE2, mimicking the tumor environment observed with the poorly-differentiated exocrine and ductal pancreatic tumors.34–36 PGE2 serves as a ligand for four EP receptor subtypes EP1 to EP4 that are coupled to distinct G proteins.37–39 Activation of EP4 receptor correlates with an activation of MAPK signaling but has not been demonstrated directly.38 Our finding shows BxPC-3 treated with PGE2 increases phosphorylated ERK expression that was blocked when treated with U0126, indirectly demonstrating the involvement of MAPK signaling. Transcriptional regulation of COX-2 and mPGES-1 appear to involve mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling as MAPK has been reported to activate Egr-1 in the transcriptional activation of mPGES-1 as well as the induction of COX-2 expression, resulting in elevated PGE2.11,12 Additionally, MAPK signaling is capable of mediating COX-2 expression at the transcriptional level through ERK and CREB40–42 and post-transcriptional through mRNA message stability,43–45 as well as mediating mPGES-1 expression through Egr-1.10,11 The regulation of PGDH in conjunction with COX-2/mPGES-1 production of PGE2 is unclear but appears to converge on MAPK signaling, suggesting elevated PGE2 may result from the coupled up-regulation of COX-2 and mPGES-1 with simultaneous or subsequent down-regulation of PGDH. These results suggest that enhanced PGE2 production proceeds through the seemingly coupled expression of COX-2 and mPGES-1 and down-regulation of PGDH by SNAI2 in pancreatic tumors.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This work was supported in part by NIH grant T32 DK07180-34 (H.P.), R01CA122042 (G.E.), P01AT003960 (UCLA Center of Excellence in Pancreatic Diseases) and the Hirshberg Laboratories for Pancreatic Cancer Research.

Abbreviations

- COX-2

cyclooxygenase-2

- MEK

mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- ERK

extracellular signal-related kinase

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PG

prostaglandin

- PGDH

15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase

- mPGES

microsomal prostaglandin E synthase

Contributor Information

Hung Pham, Department of Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095.

Monica Chen, Hirshberg Laboratories for Pancreatic Cancer Research, Department of Surgery, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095.

Aihua Li, Hirshberg Laboratories for Pancreatic Cancer Research, Department of Surgery, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095.

Jonathan King, Hirshberg Laboratories for Pancreatic Cancer Research, Department of Surgery, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095.

Eliane Angst, Hirshberg Laboratories for Pancreatic Cancer Research, Department of Surgery, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095.

David W. Dawson, Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095.

Jenny Park, Hirshberg Laboratories for Pancreatic Cancer Research, Department of Surgery, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095.

Howard A. Reber, Hirshberg Laboratories for Pancreatic Cancer Research, Department of Surgery, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095.

Hines O. Joe, Hirshberg Laboratories for Pancreatic Cancer Research, Department of Surgery, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095.

Guido Eibl, Hirshberg Laboratories for Pancreatic Cancer Research, Department of Surgery, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095.

REFERENCES

- 1.Murakami M, Nakatani Y, Tanioka T, et al. Prostaglandin E synthase. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2002;(68–69):383–399. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(02)00043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang D, Dubois RN. Prostaglandin and cancer. Gut. 2006;55:115–122. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.047100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lev-Ari S, Lichtenberg D, Arber N. Compositions for treatment of cancer and inflammation. Recent Pat. Anticancer Drug Discov. 2008;3:55–62. doi: 10.2174/157489208783478720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chu J, Lloyd FL, Trifan OC, et al. Potential involvement of the cyclooxygenase-2 pathway in the regulation of tumor-associated angiogenesis and growth in pancreatic cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2003;2:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eibl G, Bruemmer D, Okada Y, et al. PGE2 is generated by specific COX-2 activity and increases VEGF production in COX-2-expressing human pancreatic cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;306(4):887–897. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark JD, Lin LL, Kriz RW, et al. A novel arachidonic acid-selective cytosolic PLA2 contains a Ca2+-dependent translocation domain with homology to PKC and GAP. Cell. 1991;65:1043–1051. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90556-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith WL, DeWitt DL, Garavito RM. Cyclooxygenases: structural, cellular, and molecular biology. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2000;69:145–182. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trifan OC, Hla T. Cyclooxygenase-2 modulates cellular growth and promotes tumorigenesis. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2003;7:207–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2003.tb00222.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yip-Schneider MT, Barnard DS, Billings SD, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression in human pancreatic adenocarcinomas. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:139–146. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murakami M, Naraba H, Tanioka T, et al. Regulation of prostaglandin E2 biosynthesis by inducible membrane-associated prostaglandin E2 synthase that acts in concert with cyclooxygenase-2. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:32783–32792. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003505200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jakobsson PJ, Thoren S, Morgenstern R, et al. Identification of human prostaglandin E synthase: a microsomal, glutathione-dependent, inducible enzyme, constituting a potential novel drug target. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:7220–7225. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mancini JA, Blood K, Guay J, et al. Cloning, expression, and up-regulation of inducible rat prostaglandin E synthase during lipopolysaccharide-induced pyresis and adjuvant-induced arthritis. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;267:4469–4475. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006865200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tai HH, Ensor CM, Tong M, et al. Prostaglandin catabolizing enzymes. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2002;(68–69):483–493. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(02)00050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gee JR, Montoya RG, Khaled HM, et al. Cytokeratin 20, AN43, PGDH, and COX-2 expression in transitional and squamous cell carcinoma of the bladder. Urol. Oncol. 2003;21:266–270. doi: 10.1016/s1078-1439(02)00271-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quidville V, Segond N, Pidoux E, et al. Tumor growth inhibition by indomethacin in a mouse model of human medullary thyroid cancer: implication of cyclooxygenases and 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase. Endocrin. 2004;145:2561–2571. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Backlund MG, Mann JR, Holla VR, et al. 15-Hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase is down-regulated in colorectal cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:3217–3223. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411221200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho H, Oliveira MA, Tai HH. Critical residues for the coenzyme specificity of NAD+-dependent 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2003;419:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2003.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tong M, Ding Y, Tai HH. Reciprocal regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 and 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase expression in A549 human lung adenocarcinoma cells. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:2170–2179. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang L, Amann JM, Kikuchi T, et al. Inhibition of epidermal growth factor receptor signaling elevates 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase in non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5587–5593. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsuo M, Ensor CM, Tai HH. Characterization of the genomic structure and promoter of the mouse NAD+-dependent 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase gene. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;235:582–586. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inukai T, Inoue A, Kurosawa H, et al. SLUG, a ces-1-related zinc finger transcription factor gene with antiapoptotic activity, is a downstream target of the E2A-HLF oncoprotein. Mol Cell. 1999;4:343–352. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80336-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Folch J, Lees M, Stanley GHS. A simple method for the isolation and purification of lipids from animal tissue. J. Biol. Chem. 1957;226:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Conacci-Sorrell M, Simcha I, Ben-Yedidia T, et al. Autoregulation of E-cadherin expression by cadherin-cadherin interactions: the roles of beta-catenin signaling, Slug and MAPK. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:847–857. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200308162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dohadwala M, Yang SC, Luo J, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2-dependent regulation of E-cadherin: prostaglandin E2 induces transcriptional repressors ZEB1 and Snail in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5338–5345. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mann JR, Backlund MG, Buchanan FG, et al. Repression of prostaglandin dehydrogenase by epidermal growth factor and Snail increases prostaglandin E2 and promotes cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6649–6656. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hasan S, Satake M, Dawson DW, et al. Expression analysis of the prostaglandin E2 production pathway in human pancreatic cancers. Pancreas. 2008;37:121–127. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31816618ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Appel MJ, van Garderen-Hoetmer A, Woutersen RA. Effects of dietary linoleic acid on pancreatic carcinogenesis in rats and hamsters. Cancer Res. 1994;54:2113–2120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tucker ON, Dannenberg AJ, Yang EK, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression is up-regulated in human pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 1999;59:987–990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okami J, Yamamoto H, Fujiwara Y, et al. Overexpression of cyclooxygenase-2 in carcinoma of the pancreas. Clin. Cancer Res. 1999;5:2018–2024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Molina MA, Sitja-Arnau M, Lemoine MG, et al. Increased cyclooxygenase-2 expression in human pancreatic carcinomas and cell lines: growth inhibition by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4356–4362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.El-Rayes BF, Zalupski MM, Shields AF, et al. A phase II study of celecoxib, gemcitabine, and cisplatin in advanced pancreatic cancer. Invest. New Drugs. 2005;23:583–590. doi: 10.1007/s10637-005-1028-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ferrari V, Valcamonico F, Amoroso V, et al. Gemcitabine plus celecoxib (GECO) in advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase II trial. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2006;57:185–190. doi: 10.1007/s00280-005-0028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dragovich T, Burris H, 3rd, Loehrer P, et al. Gemcitabine plus celecoxib in patients with advanced or metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma: results of a phase II trial. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;31:157–162. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e31815878c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsubayashi H, Infante JR, Winter J, et al. Tumor COX-2 expression and prognosis of patients with resectable pancreatic cancer. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2007;6:1569–1575. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.10.4711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hermanova M, Trna J, Nenutil R, et al. Expression of COX-2 is associated with accumulation of p53 in pancreatic cancer: analysis of COX-2 and p53 expression in premalignant and malignant ductal pancreatic lesions. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2008;20:732–739. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282f945fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bergmann F, Breinig M, Höpfner M, et al. Expression pattern and functional relevance of epidermal growth factor receptor and cyclooxygenase-2: novel chemotherapeutic targets in pancreatic endocrine tumors? Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2009;104:171–181. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hatae N, Sugimoto Y, Ichikawa A. Prostaglandin receptors: advances in the study of EP3 receptor signaling. J. Biochem. 2002;131:781–784. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a003165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Regan JW. EP2 and EP4 prostanoid receptor signaling. Life Sci. 2003;74:143–153. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sugimoto Y, Narumiya S. Prostaglandin E receptors. J. Biol Chem. 2007;282:11613–11617. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600038200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Slice LW, Chiu T, Rozengurt E. Angiotensin II and epidermal growth factor induce cyclooxygenase-2 expression in intestinal epithelial cells through small GTPases using distinct signaling pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:1582–1593. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408172200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pham H, Shafer LM, Slice LW. CREB-dependent cyclooxygenase-2 and microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 expression is mediated by protein kinase C and calcium. J. Cell Biochem. 2006;98:1653–1666. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pham H, Chong B, Vincenti R, et al. Ang II and EGF synergistically induce COX-2 expression via CREB in intestinal epithelial cells. J. Cell Physiol. 2008;214:96–109. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gou Q, Liu CH, Ben-Av P, et al. Dissociation of basal turnover and cytokine-induced transcript stabilization of the human cyclooxygenase-2 mRNA by mutagenesis of the 3'-untranslated region. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998;242:508–512. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dixon DA, Kaplan CD, McIntyre TM, Zimmerman GA, Prescott SM. Post-transcriptional control of cyclooxygenase-2 gene expression. The role of the 3'-untranslated region. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:11750–11757. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.16.11750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee HK, Jeong S. Beta-Catenin stabilizes cyclooxygenase-2 mRNA by interacting with AU-rich elements of 3'-UTR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:5705–5714. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]