Abstract

Background

We recently reported that immunoreactivity of intrarenal angiotensinogen (AGT) is significantly increased in IgA nephropathy patients. Meanwhile, we have developed direct enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays to measure plasma and urinary AGT (UAGT) in humans. This study was performed to test the hypothesis that UAGT levels are increased in chronic glomerulonephritis patients.

Methods

We analyzed 100 urine samples from 70 chronic glomerulonephritis patients (26 from IgA nephropathy, 24 from purpura nephritis, 8 from lupus nephritis, 7 from focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, and 5 from non-IgA mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis) and 30 normal control subjects.

Results

UAGT–creatinine ratio (UAGT/UCre) was correlated positively with diastolic blood pressure (p = 0.0326), urinary albumin–creatinine ratio (p < 0.0001), urinary protein–creatinine ratio (p < 0.0001) and urinary occult blood (p = 0.0094). UAGT/UCre was significantly increased in chronic glomerulonephritis patients not treated with renin-angiotensin system (RAS) blockers compared with control subjects (p < 0.0001). Importantly, glomerulonephritis patients treated with RAS blockers had a marked attenuation of this augmentation (p = 0.0021).

Conclusion

These data indicate that UAGT are increased in chronic glomerulonephritis patients and treatment with RAS blockers suppressed UAGT. The efficacy of RAS blockade to reduce the intrarenal RAS activity can be confirmed by measurement of UAGT in chronic glomerulonephritis patients.

Key Words: Renin-angiotensin system, Chronic glomerulonephritis, Angiotensinogen, Renin-angiotensin system blockade

Introduction

The renin-angiotensin system (RAS) plays an important role in blood pressure control, fluid and electrolyte homeostasis, and progression of renal disease [1,2]. Recently, the focus of interest on the RAS has shifted toward the role of the local/tissue RAS in specific tissues [3]. The local RAS in the kidney has several pathophysiologic functions for not only regulating blood pressure but also renal cell growth and production of glomerulosclerosis, which is included in the development of renal fibrosis [4,5]. Indeed, previous studies have shown that angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi) and/or angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker (ARB) have beneficial effects in rats and in humans with various renal diseases, and these effects are often considerably more significant than their suppressive effects on blood pressure [6,7].

Chronic glomerulonephritis that results in substantial renal damage is frequently characterized by relentless progression to end-stage renal disease. Renal angiotensin II, whose production is enhanced in chronic glomerulonephritis, can elevate the intraglomerular pressure, increase glomerular cell hypertrophy, and augment extracellular matrix accumulation [8,9]. Angiotensin II antagonists or synthesis inhibitors markedly decelerate, and can even prevent, renal deterioration in renal disease [1,8,10,11]. This may reflect the relatively short-term nature and small sample size of these studies, but may also be an indication that factors other than angiotensin II play an important role in progression of renal disease.

Angiotensinogen (AGT) is the only known substrate for renin that is a rate-limiting enzyme of the RAS. Recently, we reported that urinary excretion rates of AGT provide a specific index of intrarenal RAS status in angiotensin II-dependent hypertensive rats [12,13,14]. We also recently reported that intrarenal AGT immunoreactivity is enhanced in IgA nephropathy patients [15]. Moreover, it was reported that urinary AGT (UAGT) levels reflect intrarenal angiotensin II activity associated with increased risk for deterioration of renal function in chronic kidney disease patients [16]. Meanwhile, we recently developed direct quantitative method to measure UAGT using human AGT enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) [17]. These data prompted us to measure UAGT in chronic glomerulonephritis patients and investigative correlations with clinical parameters. Therefore, this study was performed to test a hypothesis that UAGT levels are enhanced in chronic glomerulonephritis patients and correlate with some clinical parameters.

Methods

Patients and Urine Samples

The experimental protocol of this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Tulane University and Tokushima University. Participants in this study were recruited in Tokushima University from April 1, 2007, to September 30, 2008. Patients were considered to have chronic glomerulonephritis if they had a documented glomerulonephritis which was diagnosed by renal biopsy and/or on clinical grounds and showed urinary protein and/or occult blood for at least 12 months. Patients with diabetes mellitus, those with malignancies, and those with urinary tract infection were excluded from this study. Among the patients with chronic glomerulonephritis, those undergoing dialysis or with a history of renal transplantation were also excluded. Consequently, 100 urine samples from 70 patients with chronic glomerulonephritis and 30 normal control subjects were included in this study. Upon referral to the study, all subjects received and signed a consent form. When the subject was not capable of providing assent based on age, simple oral explanation of the study was offered and a signed parental permission form was obtained before the entry into the study. The patients were 49 females and 21 males (5–35 years), and the control subjects included 9 females and 21 males (5–34 years). All patients had normal kidney function, as estimated by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease study equation (for those with age ≥21 years) [18] or Schwarts formula (for those with age <21 years) [19,20]. The background renal diseases were IgA nephropathy (n = 26), purpura nephritis (n = 24), lupus nephritis (n = 8), focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (n = 7), and non-IgA mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis (n = 5).

Measurements

Serum concentration of sodium, potassium, and creatinine, and urinary concentrations of sodium and protein were measured in the clinical laboratory in the Hospital of Tokushima University School of Medicine. Urinary concentrations of albumin and creatinine were measured by an automated machine (DCA 2000+, Bayer) with reagent kits (Bayer). Based on examination of urine samples, urinary occult blood index was classified as follows: 0, 0–5 erythrocytes/high-power field (HPF); 1+, 5–30 erythrocytes/HPF; 2+, >30 erythrocytes/HPF: 3+, macroscopic hematuria, as previously described [15,21]. Plasma and urinary concentrations of AGT were measured with ELISA kits as previously described [17]. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Formula [eGFR = 175 × standardized serum creatinine–1.154 × age–0.203 × 0.741 (if Asian) × 0.742 (if female)] [18], which was found to correlate well with GFR corrected for body surface area in adults [22]. We used the formula developed by Schwartz et al. [19,20] to calculate eGFR (K × height/serum creatinine) for children. The K factor was 0.55 for children aged from 2 to 12 years, 0.55 for females aged from 13 to 21 years, and 0.70 for males aged from 13 to 21 years.

Statistical Analysis

Pearson correlation coefficients and Spearman correlation coefficients were used for parametric data and nonparametric data, respectively. Standard least squares method was used for multiple regression analysis. Comparisons of continuous variables between groups were performed using one-way analysis of variance and Dunnett's test. All data are presented as means ± SE. p < 0.05 was considered significant. All computations including data management and statistical analyses were performed with JMP software (SAS Institute).

Results

Subject Profiles and Laboratory Data

The profiles of the included subjects are summarized in table 1. The laboratory data of the involved subjects are summarized in table 2.

Table 1.

Subject profiles

| Parameter | Control subjects (n = 30) | CGN − RASB (n = 24) | CGN + RASB (n = 46) | p value | χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F/M | 9/21 | 16/8 | 33/13 | 0.0007 | 14.40 |

| Age, years | 13.23 ± 1.22 | 14.46 ± 1.37 | 16.19 ± 0.98 | 0.1634 | |

| Height, cm | 133.37 ± 4.28 | 146.06 ± 4.54 | 147.92 ± 3.44∗ | 0.0267 | |

| BW, kg | 34.68 ± 3.49 | 40.26 ± 3.70 | 47.93 ± 2.80∗ | 0.0130 | |

| BMI | 18.08 ± 0.82 | 18.02 ± 0.87 | 21.02 ± 0.66∗,# | 0.0051 | |

| SBP, mm Hg | 109.00 ± 1.75 | 109.00 ± 1.94 | 109.11 ± 1.36 | 0.9983 | |

| DBP, mm Hg | 58.22 ± 1.79 | 61.05 ± 1.98 | 59.60 ± 1.38 | 0.5715 |

F = Females; M = males; BW = body weight; BMI = body mass index; SBP = systolic blood pressure; DBP = diastolic blood pressure; CGN = chronic glomerulonephritis patients; RASB = renin-angiotensin system blockade.

p < 0.05 vs. control subjects

p < 0.05 vs. CGN − RASB.

Table 2.

Laboratory data

| Parameter | Control subjects (n = 30) | CGN − RASB (n = 24) | CGN + RASB (n = 46) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum Na, mEq/l | 140.27 ± 0.36 | 140.38 ± 0.41 | 140.06 ± 0.29 | 0.8024 |

| Serum K, mEq/l | 4.12 ± 0.06 | 4.10 ± 0.07 | 4.04 ± 0.05 | 0.5888 |

| Serum Cre, mg/dl | 0.46 ± 0.03 | 0.51 ± 0.03 | 0.54 ± 0.02∗ | 0.0492 |

| Plasma AGT, μg/ml | 28.15 ± 4.87 | 29.52 ± 6.44 | 22.51 ± 9.10 | 0.8165 |

| UNa/UCre, mEq/g | 134.34 ± 16.03 | 132.45 ± 17.92 | 114.30 ± 12.80 | 0.5485 |

| UPro/UCre, g/g | 0.08 ± 0.05 | 0.33 ± 0.05∗ | 0.14 ± 0.04# | 0.0016 |

| UAlb/UCre, mg/g | 10.44 ± 12.97 | 93.03 ± 14.50∗ | 63.69 ± 10.36∗ | 0.0001 |

| Urinary occult blood, index | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 1.52 ± 0.21∗ | 1.22 ± 0.15∗ | <0.0001 |

| FENa, % | 0.42 ± 0.06 | 0.44 ± 0.07 | 0.46 ± 0.05 | 0.8511 |

| eGFR, ml/min/1.73 m2 | 114.48 ± 3.69 | 119.85 ± 3.22 | 111.6682.52 | 0.0986 |

Cre = Creatinine; UNa/UCre = urinary sodium–creatinine; UK/UCre = urinary potassium–creatinine ratio; UPro/UCre = urinary protein–creatinine ratio; UAlb/UCre = urinary albumin–creatinine ratio; FENa = fractional excretion of sodium; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate.

p < 0.05 vs. control subjects

p < 0.05 vs. CGN – RASB.

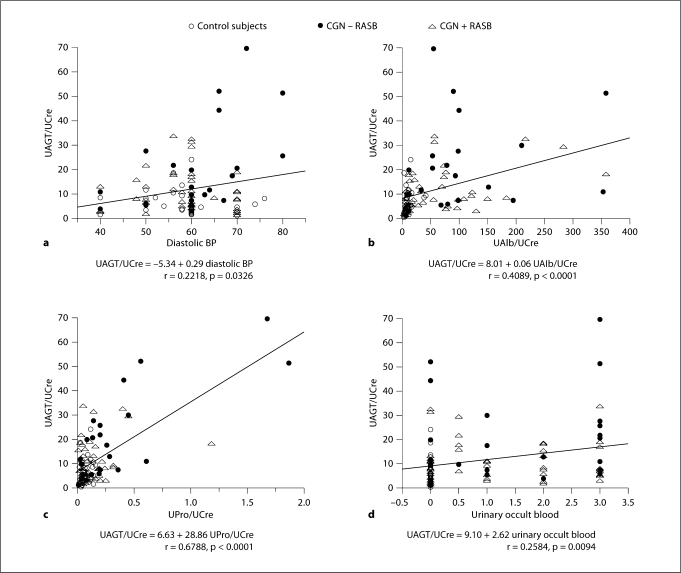

Single-Regression Analyses

Figure 1 demonstrates single-regression analyses for UAGT–creatinine ratio (UAGT/UCre) with clinical parameters. UAGT/UCre levels did not correlate with gender, age, height, body weight, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, serum sodium levels, serum potassium levels, serum creatinine levels, eGFR, urinary fractional excretion of sodium, or plasma AGT levels. However, UAGT/UCre levels significantly positively correlated with diastolic blood pressure (fig. 1a; r = 0.2218, p = 0.0326), urinary albumin–creatinine ratio (fig. 1b; r = 0.4089, p < 0.0001), urinary protein–creatinine ratio (fig. 1c; r = 0.6788, p < 0.0001), and urinary occult blood (fig. 1; r = 0.2584, p = 0.0094).

Fig. 1.

Single regression analyses for UAGT/UCre levels with diastolic blood pressure (a), urinary albumin–creatinine ratio (b), urinary protein–creatinine ratio (c), and with urinary occult blood, index (d), respectively. CGN = Chronic glomerulonephritis; RASB = RAS blockade.

Factorial Analyses

Factors with significant single correlation with UAGT/UCre levels were adopted as explanatory variables in factorial analysis. As a result, urinary albumin–creatinine ratio, urinary occult blood and diastolic blood pressure were excluded as described in table 3. Only urinary protein–creatinine can account for 47% of variation in UAGT/UCre levels (r = 0.6856, R2 = 0.47, p < 0.0001).

Table 3.

Multiple regression analysis by stepwise method for UAGT/UCre

| Parameter | Estimate | SE | T ratio | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 3.89 | 6.30 | 0.62 | 0.5391 |

| UPro/UCre, g/g | 32.13 | 4.69 | 6.84 | <0.0001∗ |

| UAlb/UCre, mg/g | −0.03 | 0.02 | −1.74 | 0.0853 |

| Urinary occult blood, index | 0.77 | 0.86 | 0.89 | 0.3768 |

| DBP, mm Hg | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.54 | 0.5884 |

p < 0.05.

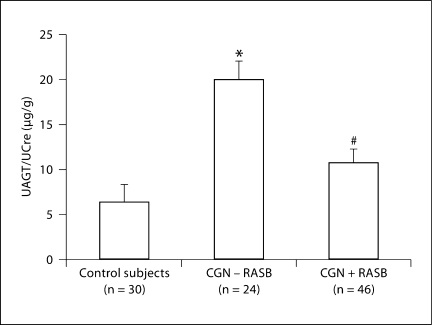

UAGT Levels in Chronic Glomerulonephritis Patients

Figure 2 shows UAGT/UCre levels in chronic glomerulonephritis patients with/without RAS blockade and in control subjects. UAGT/UCre levels were significantly increased in chronic glomerulonephritis patients without RAS blockade (19.79 ± 3.70 μg/g) compared with control subjects (6.22 ± 0.98, p < 0.0001). Importantly, the usage of RAS blockade attenuated this augmentation (10.58 ± 1.23, p = 0.0021).

Fig. 2.

UAGT/UCre levels in CGN patients with/without RASB and in control subjects. ∗ p < 0.05 vs. control subjects; # p < 0.05 vs. CGN – RASB.

Discussion

Recent studies on experimental animal models and transgenic mice have documented the involvement of AGT in the activation of the RAS and development of hypertension [23,24]. In human genetic studies, a linkage has been established between the AGT gene and hypertension [25,26,27]. Enhanced intrarenal AGT mRNA and/or protein levels have also been observed in multiple experimental models of hypertension including angiotensin II-dependent hypertensive rats [12,13,14] as well as in kidney diseases including diabetic nephropathy [28,29,30], IgA nephropathy [15,31], and radiation nephropathy [32]. Thus, AGT plays an important role in the development and progression of hypertension and kidney disease [33,34].

Recently, we developed an ELISA specific for evaluating human AGT levels [17] and found that UAGT/UCre levels were significantly increased in hypertensive patients not treated with RAS blockers compared with normotensive subjects. Importantly, patients treated with RAS blockers exhibited a marked attenuation of this augmentation. These data suggest that the efficacy of RAS blockade to reduce the intrarenal RAS activity can be assessed by measuring UAGT levels [35]. Our study therefore provides additional evidence to support the hypothesis that UAGT reflects intrarenal RAS status in chronic glomerulonephritis patients.

In this study, we randomly recruited female and male subjects aged between 5 and 35 years without any bias in the selection process. Accordingly, there were some deviations in the grouping of gender, height, body weight, and body mass index (table 1). However, it is very important to emphasize here that all of these parameters (gender, height, body weight, and body mass index) were not correlated with UAGT/UCre levels, as described above. Therefore, it would be unlikely that these deviations may affect the final results reported herein.

Correlation analysis in the present study may provide an interesting perspective. UAGT/UCre was significantly correlated positively with diastolic blood pressure, urinary albumin–creatinine ratio, protein–creatinine ratio and occult blood. We previously reported that immunoreactivity of intrarenal AGT is increased in IgA nephropathy patients and significantly correlated positively with urinary albumin–creatinine ratio, protein–creatinine ratio and occult blood [15]. These data together with our present study may suggest that intrarenal AGT level and UAGT levels can be markers of chronic glomerulonephritis.

Although most of the circulating AGT is produced and secreted by the liver, the kidneys also produce AGT [33]. Intrarenal AGT mRNA and protein have been localized to proximal tubule cells indicating that the intratubular angiotensin II could be derived from locally formed and secreted AGT [36,37]. The AGT produced in proximal tubule cells appears to be secreted directly into the tubular lumen in addition to producing its metabolites intracellularly and secreting them into the tubular lumen [38]. Proximal tubular AGT concentrations in anesthetized rats have been reported in the range of 300–600 nM which greatly exceed the free angiotensin I and angiotensin II tubular fluid concentrations [34]. Because of its molecular size (50–60 kDa), it seems unlikely that much of the plasma AGT filters across the glomerular membrane, further supporting the concept that proximal tubular cells secrete AGT directly into the tubules [39]. To determine if circulating AGT is a source of UAGT, we infused human AGT into hypertensive and normotensive rats [13]. However, human AGT was detectable in plasma but not detectable in the urine of rats [13]. The failure to detect human AGT in the urine indicates limited glomerular permeability and/or tubular degradation. These findings support the hypothesis that UAGT comes from the AGT that is formed and secreted by the proximal tubules and not from plasma. In agreement with this concept, plasma AGT levels were not correlated with UAGT/UCre levels in this study. Moreover, plasma AGT levels were not changed among the three groups even though UAGT/UCre levels were significantly different among the three groups in this study. Therefore, it seems highly likely that AGT in urine originates from AGT in the kidney, not from AGT in plasma.

We have previously reported that UAGT/UCre levels in diabetic nephropathy and membranous nephropathy patients were much higher than the average in chronic kidney disease patients [40]. Importantly, the activated intrarenal RAS has been reported in the progression of renal injury in patients with diabetic nephropathy [41] as well as membranous nephropathy [42]. In contrast, UAGT/UCre levels in minimal change were similar to those in control subjects, even though patients with minimal change showed severe proteinuria [40]. These findings in chronic kidney disease patients support the hypothesis that the enhanced UAGT in chronic glomerulonephritis patients is not just a nonspecific consequence of proteinuria.

In this study, UAGT/UCre levels were significantly correlated positively with urinary albumin–creatinine ratio and urinary protein–creatinine ratio. Therefore, in many cases, those who showed high UAGT/UCre levels also showed high urinary albumin–creatinine ratio and/or high urinary protein–creatinine ratio. However, when individual values were examined, there were also some cases where UAGT/UCre levels did not parallel the urinary albumin–creatinine ratio (fig. 1b) and/or high urinary protein–creatinine ratio (fig. 1c). Also, we have reported that increased UAGT levels precede increased urinary albumin levels and urinary protein levels in type 1 diabetic juveniles [43]. Taken together, these data indicate that the enhanced UAGT in chronic glomerulonephritis patients in this study is not just a nonspecific consequence of proteinuria.

A glucocorticoid responsive element is located in the promoter region of the human AGT gene [44,45]. Therefore, the usage of glucocorticoid, such as steroid, may affect plasma and/or UAGT levels. We have also examined the influence of steroid therapy upon UAGT levels. As a result, UAGT/UCre levels were significantly increased in chronic glomerulonephritis patients not treated with steroid therapy (16.32 ± 2.34 μg/g) compared with normal control subjects (6.22 ± 0.98 μg/g, p = 0.0006). The usage of steroid therapy attenuated this augmentation (10.239 ± 1.80 μg/g, p = 0.0286). Interestingly, plasma AGT levels in chronic glomerulonephritis patients without steroid therapy were decreased (18.02 ± 3.36 μg/ml) compared with control subjects (28.15 ± 4.87 μg/ml, p = 0.0849). However, plasma AGT levels were elevated by the treatment of steroid therapy (45.52 ± 11.69 μg/ml, p = 0.0037). These results may suggest that steroid therapy affects plasma and UAGT levels in an opposite direction, also supporting that UAGT is not derived from AGT in plasma.

Different antihypertensive regiments also have different effects on the circulating and tissue RAS and plasma and UAGT levels. In order to address this issue, we have subdivided the chronic glomerulonephritis patients with RAS blockade group into two subgroups according to the antihypertensive regimens: patients treated with ACEi and patients treated with ARB. In the results, statistically significant difference in UAGT levels was not observed between the ACEi (12.06 ± 1.58 μg/g) and ARB groups (9.46 ± 2.33 μg/g; p = 0.4527).

We believe that a larger multicenter randomized control study is required to extend these observations. A prospective study to determine the relationship between the effect of RAS blockade on UAGT and urinary albumin/protein would be helpful in assessing the clinical significance of the decrease in UAGT with RAS blockade. A randomized clinical trial has been projected to establish a novel diagnostic test to identify those glomerulonephritis patients most likely to respond to RAS blockade. This trial could provide useful information to allow a mechanistic rationale for a better selection of an optimal treatment of chronic glomerulonephritis.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge critical discussion and/or excellent technical assistance from L. Gabriel Navar, PhD; Toshie Saito, MD; Naro Ohashi, MD, PhD; Kayoko Miyata, PhD; Ryousuke Satou, PhD; Akemi Katsurada, MS; Omar W. Acres, BS; M. Patrick Sweeny, MS; G. Michael Upchurch, MS; Nina A. Perrault, BS; Jessica L. Mucci, MS (Tulane University), and clerkship support from Ms. Naomi Okamoto (Tokushima University). The authors also acknowledge Kenichi Suga, MD, and Sato Matsuura, MD (Tokushima University), for the recruitment of participants in this study. This study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease (R01DK072408) and the National Center for Research Resources (P20RR017659).

References

- 1.Anderson S, Rennke HG, Brenner BM. Therapeutic advantage of converting enzyme inhibitors in arresting progressive renal disease associated with systemic hypertension in the rat. J Clin Invest. 1986;77:1993–2000. doi: 10.1172/JCI112528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Navar LG, Harrison-Bernard LM, Imig JD, Wang CT, Cervenka L, Mitchell KD. Intrarenal angiotensin II generation and renal effects of AT1 receptor blockade. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10(suppl 12):S266–S272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dzau VJ, Re R. Tissue angiotensin system in cardiovascular medicine. A paradigm shift? Circulation. 1994;89:493–498. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.1.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kagami S, Border WA, Miller DE, Noble NA. Angiotensin II stimulates extracellular matrix protein synthesis through induction of transforming growth factor-beta expression in rat glomerular mesangial cells. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:2431–2437. doi: 10.1172/JCI117251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruiz-Ortega M, Egido J. Angiotensin II modulates cell growth-related events and synthesis of matrix proteins in renal interstitial fibroblasts. Kidney Int. 1997;52:1497–1510. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horita Y, Tadokoro M, Taura K, Suyama N, Taguchi T, Miyazaki M, Kohno S. Low-dose combination therapy with temocapril and losartan reduces proteinuria in normotensive patients with immunoglobulin a nephropathy. Hypertens Res. 2004;27:963–970. doi: 10.1291/hypres.27.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ravid M, Brosh D, Levi Z, Bar-Dayan Y, Ravid D, Rachmani R. Use of enalapril to attenuate decline in renal function in normotensive, normoalbuminuric patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:982–988. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-12_part_1-199806150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brunner HR. ACE inhibitors in renal disease. Kidney Int. 1992;42:463–479. doi: 10.1038/ki.1992.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kohan DE. Angiotensin II and endothelin in chronic glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int. 1998;54:646–647. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lafayette RA, Mayer G, Park SK, Meyer TW. Angiotensin II receptor blockade limits glomerular injury in rats with reduced renal mass. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:766–771. doi: 10.1172/JCI115949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giatras I, Lau J, Levey AS. Effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors on the progression of nondiabetic renal disease: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Angiotensin-Converting-Enzyme Inhibition and Progressive Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:337–345. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-5-199709010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kobori H, Harrison-Bernard LM, Navar LG. Expression of angiotensinogen mRNA and protein in angiotensin II-dependent hypertension. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:431–439. doi: 10.1681/asn.v123431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kobori H, Nishiyama A, Harrison-Bernard LM, Navar LG. Urinary angiotensinogen as an indicator of intrarenal angiotensin status in hypertension. Hypertension. 2003;41:42–49. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000050102.90932.cf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kobori H, Prieto-Carrasquero MC, Ozawa Y, Navar LG. AT1 receptor mediated augmentation of intrarenal angiotensinogen in angiotensin II-dependent hypertension. Hypertension. 2004;43:1126–1132. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000122875.91100.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kobori H, Katsurada A, Ozawa Y, Satou R, Miyata K, Hase N, Suzaki Y, Shoji T. Enhanced intrarenal oxidative stress and angiotensinogen in IgA nephropathy patients. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;358:156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.04.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamamoto T, Nakagawa T, Suzuki H, Ohashi N, Fukasawa H, Fujigaki Y, Kato A, Nakamura Y, Suzuki F, Hishida A. Urinary angiotensinogen as a marker of intrarenal angiotensin II activity associated with deterioration of renal function in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:1558–1565. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006060554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katsurada A, Hagiwara Y, Miyashita K, Satou R, Miyata K, Ohashi N, Navar LG, Kobori H. Novel sandwich ELISA for human angiotensinogen. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;293:F956–F960. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00090.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, Stevens LA, Zhang YL, Hendriksen S, Kusek JW, Van Lente F. Using standardized serum creatinine values in the modification of diet in renal disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:247–254. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-4-200608150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwartz GJ, Haycock GB, Edelmann CM, Jr, Spitzer A. A simple estimate of glomerular filtration rate in children derived from body length and plasma creatinine. Pediatrics. 1976;58:259–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwartz GJ, Gauthier B. A simple estimate of glomerular filtration rate in adolescent boys. J Pediatr. 1985;106:522–526. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(85)80697-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miyake-Ogawa C, Miyazaki M, Abe K, Harada T, Ozono Y, Sakai H, Koji T, Kohno S. Tissue-specific expression of renin-angiotensin system components in IgA nephropathy. Am J Nephrol. 2005;25:1–12. doi: 10.1159/000083224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, Marsh J, Stevens LA, Kusek JW, Van Lente F. Expressing the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate with standardized serum creatinine values. Clin Chem. 2007;53:766–772. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.077180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kobori H, Ozawa Y, Satou R, Katsurada A, Miyata K, Ohashi N, Hase N, Suzaki Y, Sigmund CD, Navar LG. Kidney-specific enhancement of ANG II stimulates endogenous intrarenal angiotensinogen in gene-targeted mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;293:F938–F945. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00146.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sachetelli S, Liu Q, Zhang SL, Liu F, Hsieh TJ, Brezniceanu ML, Guo DF, Filep JG, Ingelfinger JR, Sigmund CD, Hamet P, Chan JS. RAS blockade decreases blood pressure and proteinuria in transgenic mice overexpressing rat angiotensinogen gene in the kidney. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1016–1023. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Inoue I, Nakajima T, Williams CS, Quackenbush J, Puryear R, Powers M, Cheng T, Ludwig EH, Sharma AM, Hata A, Jeunemaitre X, Lalouel JM. A nucleotide substitution in the promoter of human angiotensinogen is associated with essential hypertension and affects basal transcription in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:1786–1797. doi: 10.1172/JCI119343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jeunemaitre X, Soubrier F, Kotelevtsev YV, Lifton RP, Williams CS, Charru A, Hunt SC, Hopkins PN, Williams RR, Lalouel JM, et al. Molecular basis of human hypertension: role of angiotensinogen. Cell. 1992;71:169–180. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90275-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao YY, Zhou J, Narayanan CS, Cui Y, Kumar A. Role of C/A polymorphism at −20 on the expression of human angiotensinogen gene. Hypertension. 1999;33:108–115. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson S, Jung FF, Ingelfinger JR. Renal renin-angiotensin system in diabetes: functional, immunohistochemical, and molecular biological correlations. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:F477–F486. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1993.265.4.F477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh R, Singh AK, Leehey DJ. A novel mechanism for angiotensin II formation in streptozotocin-diabetic rat glomeruli. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;288:F1183–F1190. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00159.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leehey DJ, Singh AK, Bast JP, Sethupathi P, Singh R. Glomerular renin angiotensin system in streptozotocin diabetic and Zucker diabetic fatty rats. Transl Res. 2008;151:208–216. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takamatsu M, Urushihara M, Kondo S, Shimizu M, Morioka T, Oite T, Kobori H, Kagami S. Glomerular angiotensinogen protein is enhanced in pediatric IgA nephropathy. Pediatr Nephrol. 2008;23:1257–1267. doi: 10.1007/s00467-008-0801-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kobori H, Ozawa Y, Suzaki Y, Prieto-Carrasquero MC, Nishiyama A, Shoji T, Cohen EP, Navar LG. Young Scholars Award Lecture: intratubular angiotensinogen in hypertension and kidney diseases. Am J Hypertens. 2006;19:541–550. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kobori H, Nangaku M, Navar LG, Nishiyama A. The intrarenal renin-angiotensin system: from physiology to the pathobiology of hypertension and kidney disease. Pharmacol Rev. 2007;59:251–287. doi: 10.1124/pr.59.3.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Navar LG, Harrison-Bernard LM, Nishiyama A, Kobori H. Regulation of intrarenal angiotensin II in hypertension. Hypertension. 2002;39:316–322. doi: 10.1161/hy0202.103821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kobori H, Alper AB, Jr, Shenava R, Katsurada A, Saito T, Ohashi N, Urushihara M, Miyata K, Satou R, Hamm LL, Navar LG. Urinary angiotensinogen as a novel biomarker of the intrarenal renin-angiotensin system status in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 2009;53:344–350. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.123802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ingelfinger JR, Zuo WM, Fon EA, Ellison KE, Dzau VJ. In situ hybridization evidence for angiotensinogen messenger RNA in the rat proximal tubule. An hypothesis for the intrarenal renin angiotensin system. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:417–423. doi: 10.1172/JCI114454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Darby IA, Sernia C. In situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry of renal angiotensinogen in neonatal and adult rat kidneys. Cell Tissue Res. 1995;281:197–206. doi: 10.1007/BF00583388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lantelme P, Rohrwasser A, Gociman B, Hillas E, Cheng T, Petty G, Thomas J, Xiao S, Ishigami T, Herrmann T, Terreros DA, Ward K, Lalouel JM. Effects of dietary sodium and genetic background on angiotensinogen and renin in mouse. Hypertension. 2002;39:1007–1014. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000016177.20565.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rohrwasser A, Morgan T, Dillon HF, Zhao L, Callaway CW, Hillas E, Zhang S, Cheng T, Inagami T, Ward K, Terreros DA, Lalouel JM. Elements of a paracrine tubular renin-angiotensin system along the entire nephron. Hypertension. 1999;34:1265–1274. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.34.6.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kobori H, Ohashi N, Katsurada A, Miyata K, Satou R, Saito T, Yamamoto T. Urinary angiotensinogen as a potential biomarker of severity of chronic kidney diseases. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2008;2:349–354. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ogawa S, Mori T, Nako K, Kato T, Takeuchi K, Ito S. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers reduce urinary oxidative stress markers in hypertensive diabetic nephropathy. Hypertension. 2006;47:699–705. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000203826.15076.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mezzano SA, Aros CA, Droguett A, Burgos ME, Ardiles LG, Flores CA, Carpio D, Vio CP, Ruiz-Ortega M, Egido J. Renal angiotensin II up-regulation and myofibroblast activation in human membranous nephropathy. Kidney Int Suppl. 2003:S39–S45. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.64.s86.8.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saito T, Urushihara M, Kotani Y, Kagami S, Kobori H. Increased urinary angiotensinogen is precedent to increased urinary albumin in patients with type 1 diabetes. Am J Med Sci. 2009;338:478–480. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181b90c25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jain S, Li Y, Patil S, Kumar A. A single-nucleotide polymorphism in human angiotensinogen gene is associated with essential hypertension and affects glucocorticoid induced promoter activity. J Mol Med. 2005;83:121–131. doi: 10.1007/s00109-004-0621-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jain S, Li Y, Patil S, Kumar A. HNF-1alpha plays an important role in IL-6-induced expression of the human angiotensinogen gene. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C401–C410. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00433.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]