Abstract

To image synaptic activity within neural circuits, we have tethered the genetically-encoded calcium indicator (GECI) GCaMP2 to synaptic vesicles by fusion to synaptophysin. The resulting reporter, SyGCaMP2, detects the electrical activity of neurons with two advantages over existing cytoplasmic GECIs: the locations of synapses are identified and the reporter displays a linear response over a wider range of spike frequencies. Simulations and experimental measurements indicate that linearity arises because SyGCaMP2 samples the brief calcium transient passing through the presynaptic compartment close to voltage-sensitive calcium channels rather than changes in bulk calcium concentration. In vivo imaging in zebrafish demonstrates that SyGCaMP2 can assess electrical activity in conventional synapses of spiking neurons in the optic tectum as well as graded voltage signals transmitted by ribbon synapses of retinal bipolar cells. Localizing a GECI to synaptic terminals provides a strategy for monitoring activity across large groups of neurons at the level of individual synapses.

Keywords: synapse, calcium, action potential, fluorescent reporter, hippocampal neuron, GCaMP2, zebrafish, retina, tectum

Introduction

Understanding the function of neural circuits requires the monitoring of electrical signals generated by groups of neurons, as well as the transmission of signals at the synaptic junctions that connect them. Measuring where, when and how strongly synapses are active within a circuit is therefore an important technical challenge.

Electrophysiological methods record electrical activity with unparalleled resolution, but are difficult to apply in vivo or to more than one neuron at a time. Optical techniques show promise for monitoring electrical activity across many neurons, especially using fluorescent calcium indicators that report the opening of calcium channels when a neuron is excited1,2. Synthetic calcium dyes are available with a range of properties, but GECIs offer the important advantage of targeting to known classes of neuron3-5. Detecting the activation of synapses has proven more difficult. The best general approach to date has been the reporter protein synaptopHluorin, which signals the loss of protons from a synaptic vesicle on fusion6. But the sensitivity of synaptopHluorin is limited by background fluorescence generated by expression on the cell surface. In intact circuits, synaptopHluorin has only provided useful signals after prolonged stimulation and spatial averaging4,7,8. The analysis of circuit function would be aided greatly by a genetically-encoded reporter that detects the activation of individual synapses by single action potentials (APs).

Here we investigate a new approach for detecting synaptic activity optically: the localization of a GECI to the presynaptic terminal to sense calcium influx triggering neurotransmitter release9. The presynaptic terminal is a small compartment containing a high density of voltage-sensitive calcium channels, and usually experiences the largest calcium transient in response to a spike10. The reporter we designed, SyGCaMP2, is a fusion of GCaMP211 to the cytoplasmic side of synaptophysin, a transmembrane protein in synaptic vesicles. Using cultured hippocampal neurons and simulations, we demonstrate that SyGCaMP2 has the potential to detect single spikes at individual synapses, as well as activity occurring in short bursts. By imaging zebrafish in vivo, we demonstrate that SyGCaMP2 can be used to monitor visual activity in conventional synapses of spiking neurons in the optic tectum and ribbon synapses of graded neurons in the retina, sampling hundreds of terminals simultaneously.

Results

The rationale for localizing a calcium indicator to presynaptic compartments

To investigate how a GECI responds to synaptic calcium signals we began by constructing a Virtual Cell model of calcium dynamics in the synaptic bouton and neighbouring axon of a hippocampal neuron designed to reproduce optical measurements made using furaptra12 (Fig. 1a and b, Supplementary Figure 1 and Table 1 online and Supplementary Note online). We then incorporated a GECI into the model. GCaMP2 was chosen because it displays a large fluorescence increase on binding calcium (~6-fold) and appears promising for detecting electrical activity5. Using GCaMP2 free in the cytoplasm, the peak response to a single AP recorded within a bouton is expected to be ~8% (Fig.1c), which is within the limits of detectability in many imaging situations. The model also predicts that while the spatially averaged Ca2+ signal in the bouton recovers with t1/2 = 2 ms, the SyGCaMP2 signal recovers with t1/2 = 360 ms (Fig. 1c), which is similar to the rate at which the reporter relaxes back to a state of reduced fluorescence after Ca2+ ions dissociate11. These simulations underline a key property of the GECIs currently available: they are not in rapid equilibrium with brief Ca2+ transients generated close to voltage-sensitive calcium channels.

Figure 1. Modelling GCaMP2 responses in the synapse and axon.

(a) Geometry of the 2-D model implemented in Virtual Cell. (b) Calcium buffers, channels and pumps used in the model. Distribution of calcium channels at the active zone is shown in red while distribution of synaptic vesicles in cyan. (c) The modelled response of GCaMP2 (1 μM) to a single spike (green trace) calculated as the relative change in GCaMP2 fluorescence in an ROI over the bouton. The black trace is the spatially averaged Ca2+ concentration reported by cytoplasmatic furaptra, also averaged over the whole bouton. This signal was obtained by adjusting the parameters of the model to reproduce the response to a single spike reported by furaptra12. Note the slower GCaMP2 signal compared to the Ca2+ transient. (d) Simulations of GCaMP2 signals at different distances from calcium channels: within 50 nm of the active zone (red); averaged over the bouton (cyan); over a 2.25 μm length of axon close to the bouton (amber), and over the next 2.25 μm length of axon (blue). (e and f) Neuronal-glial cultures of rat hippocampi expressing cytoplasmic GCaMP2 (e) or synaptic SyGCaMP2 (f). Expression of the synaptic marker mRFP-VAMP is shown in the middle and merged images to the right. The rectangular field of view is expanded in the images below. Only SyGCaMP2 visualizes all synaptic boutons marked by mRFP-VAMP. For equipment and settings see Supplementary Methods online. Scale bars = 20 μm.

Might the GCaMP2 signal generated by a spike be improved if it were sampled closer to calcium channels by, for instance, fusion of GCaMP2 to the channels themselves? An immediate disadvantage of this strategy will be the small number of GCaMP2 molecules that might sense the calcium transient, which will limit the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). Simulations also predicted that placing GCaMP2 within 50 nm of the active zone will generate signals that differ little from averages obtained over the whole bouton, even in the absence of noise (red and green traces in Fig. 1d). In contrast, GCaMP2 signals in the axon will be slow and small, and so should not be allowed to contaminate fluorescence collected from the synaptic bouton. These simulations therefore suggest that the best combination of SNR and temporal resolution will be obtained by distributing GCaMP2 molecules throughout the presynaptic compartment, so this was the strategy that we investigated experimentally.

To localize GCaMP2 to synaptic terminals we fused it to the cytoplasmic side of the vesicular protein synaptophysin to make SyGCaMP2. We chose synaptophysin because it is localized to synaptic vesicles with relatively little expression on the surface membrane13. SyGCaMP2 marked synaptic boutons in cultured hippocampal neurons as clearly as mRFP-VAMP (Fig. 1e and f), and also responded to calcium influx. A region of synapses containing SyGCaMP2 is shown in Figure 2a (left), together with images showing the relative change in fluorescence during a train of 10 APs delivered at 20 Hz (Supplementary Video 1 online). In this example, 10 APs caused a relative fluorescence increase of ~75% (Fig. 2b). Importantly, tethering GCaMP2 to synaptophysin did not hinder vesicle fusion measured using FM4-64 (Supplementary Figure 2 online). SyGCaMP2 therefore provides two important advantages over GECI mobile in the cytoplasm: the immediate identification of synaptic boutons at rest, and the detection of calcium influx at sites close to voltage-sensitive calcium channels.

Figure 2. Presynaptic calcium signals visualized with SyGCaMP2.

(a) Cultured neurons expressing SyGCaMP2 (grey-scale image, left) and pseudocoloured images showing the relative change in fluorescence at rest, then 0.2 s and 1 s after the beginning of a train of 10 APs delivered at 20 Hz. Note the variability in the amplitude of the presynaptic calcium signal between different boutons. For equipment and settings see Supplementary Methods. Scale bar = 20 μm. (b) SyGCaMP2 responses from 20 individual boutons shown in a (red traces) and their average (black). (c) Graph showing fluorescence responses to 1 AP from 100 synapses in the field in a. (d) SyGCaMP2 responses to a single AP from 20 individual boutons (red traces) and the average (black). (e) Histogram showing the distribution of SyGCaMP2 responses to 1 AP measured at their peak. The mean amplitude was 11.5 %. (f) The distribution of SNRs measured at different boutons in response to 1 AP, again from the field shown in a. SNR was measured as the peak amplitude of the response divided by the standard deviation in the signal at rest, as shown in g. (g) Response to a single AP averaged from three neighbouring boutons shown in the red box in a. Note this was a single trial. The peak amplitude of the signal was 22% and the noise in the baseline had a standard deviation of 3%, yielding a SNR of 7.3 for the average.

Sensitivity and dynamic range of SyGCaMP2

A number of GECIs have been tested as detectors of spike activity3-5. Among the most sensitive is D3cpv, which generates a signal of ~8% in response to a single AP when the signal is collected from the soma. A limitation of D3cpv, as well as synthetic calcium indicators of high affinity, is saturation of the response after just 2-3 APs. This limitation reflects the high affinity of the reporter and the slow decay of the calcium transient in a volume as large as the soma (~4 s)14. GCaMP2 also has a high affinity for calcium (Kd ~150 nM), but we found that its localization to the synaptic bouton, where the calcium transient is very brief, extended the range of firing rates that could be reported.

Responses of SyGCaMP2 to single APs are shown in Figure 2c and d, where each red trace is a single trial at a single synaptic bouton from the field shown in Figure 2a. The response (ΔF/F) averaged 11.50 ± 0.01%, and decayed with the off-rate of the reporter (t1/2 = 210 ms; Fig. 2d). Strikingly, the amplitude of signals varied widely between different boutons, from about 4% to about 90% (Fig. 2e). Such variations in the amplitude of the presynaptic calcium transient are likely to contribute to the heterogenous release probability of synapses in these cultures15,16. As a consequence, the SNR for detection of a spike depended on the bouton at which it was measured. The distribution of SNRs from the field shown in Figure 2a is plotted in Figure 2f. About 20% of boutons exhibited a SNR greater than two for a single spike, which is similar to the performance achieved with the synthetic indicator Fluo-4F in dendrites17. A simple way to improve the SNR was to average the response over several boutons on a short stretch of axon. For instance, Figure 2g shows the signal from the three boutons boxed in red in Figure 2a, when the SNR was 7.3 for a single AP. SyGCaMP2 therefore allowed the detection of individual spikes with a good degree of reliability while also revealing heterogeneity in the calcium signal triggering vesicle release at different terminals.

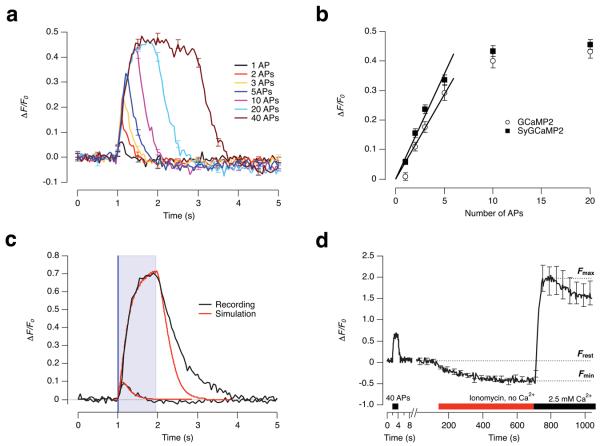

To investigate the range of activities that SyGCaMP2 might report, we delivered trains of APs of various durations at a fixed frequency of 20 Hz, as shown in Figure 3a. The peak amplitude of the response was linear up to about 5-8 APs, depending on the culture in which it was measured, and a plateau was not reached until 10-20 APs (Fig. 3b). The response of SyGCaMP2 in hippocampal boutons was therefore linear over a range sufficient to detect short bursts of APs. This property originates from its localization to the presynaptic bouton rather than its attachment to synaptophysin because GCaMP2 signals at the synapse were similar (Fig. 3b). When two trains of 10 AP were delivered 6 s apart the responses were almost identical, indicating that these stimuli did not generate significant spatial rearrangements of the reporter (Supplementary Figure 2).

Figure 3. The dynamic range of SyGCaMP2 responses.

(a) Average SyGCaMP2 responses to trains of 1, 2, 3, 5, 10, 20 and 40 APs at 20 Hz. Each trace represents 500 synapses from 6 different cover slips. Error bars show s.e.m. (b) Peak amplitude of the SyGCaMP2 response (squares) taken from a as a function of the number of APs delivered. GCaMP2 responses (circles) are also plotted (Error bars, s.e.m.; n=450 synapses from 5 different cover slips). When using GCaMP2, boutons were identified by co-expressing mRFP-VAMP2. The response of SyGCaMP2 was linear up to ~8 APs, with a proportionality constant of 7 ± 0.3 % per AP for SyGCaMP2 and 5 ± 0.4 % for GCaMP2. (c) Comparison of experimental SyGCaMP2 measurements (black traces) and their simulations (red). The model accurately predicts the response to 1 AP as well as the saturating response to 20 APs at 20 Hz. The model does not account for the slower recovery of the SyGCaMP2 signal after the introduction of larger calcium loads. (d) SyGCaMP2 response to 40 APs delivered at 20 Hz (70% increase). Neurons were then perfused with ionomycin (5 μM), 0 Ca2+, and 10 mM EGTA. The minimum fluorescence (ΔF/F0min) was −0.55 relative to rest. The external [Ca2+] was then increased to 2.5 mM to saturate SyGCaMP2. The peak signal (ΔF/F0max) was 2.1. Assuming a Hill coefficient of 4 for the binding of Ca2+ to GCaMP2 and a Kd of 150 nM, the resting free [Ca2+] is estimated to be ~2 nM.

SyGCaMP2 generated a maximum response of ~70% at a frequency of 20 Hz, in agreement with the model (Fig. 3c). To determine if the plateau is caused by saturation of the reporter we imposed changes in internal calcium concentration by permeabilizing the surface membrane using ionomycin (Fig. 3d). In the presence of 0 Ca2+ and 10 mM EGTA the fluorescence reached a minimum, and then increased 5.2-fold on addition of 2.5 mM Ca2+, 0 EGTA. The relative increase in fluorescence of SyGCaMP2 going from the calcium-free to fully calcium-bound state was therefore very close to the value of 4 to 5 measured for GCaMP2 in vitro11. In contrast, the steady response of SyGCaMP2 to a train at 20 Hz was only 30% of this maximum (Fig. 3d), and the model accounted for this by the balance between the average rate of Ca2+ influx and diffusion of Ca2+ out of the bouton into the axon (Fig. 3c). The avoidance of saturation at 20 Hz allowed the maximum response of SyGCaMP2 to increase at higher spike frequencies: the initial rate of rise of the SyGCaMP2 signal was proportional to frequencies up to ~80 Hz (Supplementary Figure 1).

Using SyGCaMP2 to reconstruct electrical activity by deconvolution

One approach by which the activity of neurons can be assessed from calcium signals is deconvolution using a kernel derived from the response to a single spike18,19. Deconvolution is only useful while the response of the reporter is linear, and has therefore been difficult to use with cytoplasmic GECIs. The wider linear range of SyGCaMP2 prompted us to investigate whether deconvolution might be a useful approach with this reporter, and an example from a single neuron in culture is shown in Figure 4a-c. Intrinsic network activity was blocked and a “physiological” spiking pattern applied (Fig. 4a), mimicking hippocampal activity in a sleeping rat. SyGCaMP2 signals were averaged over ten synapses along one process (Fig. 4b) and deconvolved using an impulse response measured in response to single APs (see inset) to yield a spike frequency trace. Imaging was carried out at 20 Hz, so the ideal reconstruction (Fig. 4c) counts spikes in 50 ms time bins. There were several points of agreement between the experimental and idealized reconstructions: single APs were detected and variations in the number of APs per burst were observed. A comparison of the reconstruction from four different cultures is shown in Figure 4d, and the quality is summarized by plotting the reconstructed against the ideal spike rate in Figure 4e. These results indicate that localizing a GECI to the synaptic bouton extends the utility of deconvolution to bursts of spikes lasting seconds at frequencies up to ~10 Hz.

Figure 4. Deconvolution of SyGCaMP2 signals to monitor spike activity.

(a) A “physiological” stimulus pattern (1ms, 20mA) delivered to the hippocampal cultures simulating the spike activity recorded in the hippocampus of a sleeping rat in vivo (courtesy of Matt Jones, Bristol). (b) The upper graph shows the SyGCaMP2 signal averaged from 10 synaptic boutons of a single neuron responding to the stimulus in a. Images were acquired in 50 ms intervals. The lower graph shows the spike frequency reconstructed by deconvolution of the SyGCaMP2 signal with the impulse response shown in the inset (decaying with τ = 250 ms). (c) The ideal reconstruction of spike frequency obtained by counting spikes into 50 ms time bins (the frame duration when imaging SyGCaMP2). Note that the reconstruction agrees closely with the ideal for brief bursts of spikes measured physiologically. (d) Spike frequency reconstructed by deconvolution for four different SyGCaMP2 experiments (each from a different cover slip). SyGCaMP2 signals were averaged from 10 synaptic boutons each. The bottom graph shows the ideal reconstruction from c for comparison (e) The reconstructed spike rate against the ideal spike rate for experiments shown in d (error bars: s.e.m.)

Using SyGCaMP2 to monitor synaptic activity in vivo

To investigate the utility of SyGCaMP2 in vivo we transiently expressed the reporter in the optic tectum of zebrafish using the α–tubulin promoter20,21. The tectum receives visual information from retinal ganglion cells as well as integrating inputs from other sensory systems22. A single optical section through the tectum in a larval fish at 9 days post-fertilization (dpf) is shown in Figure 5a, and Figures 5b and c show a region in which 100 synaptic terminals labelled with SyGCaMP2 could be distinguished. Tectal neurons demonstrated very little spontaneous activity23, but a subset of 12 synaptic boutons could be activated by an electric field (Fig. 5d) or by light (Fig. 5e). These synapses are marked amber in Figure 5c, and appear to follow the trajectory of a single axonal process. The “minimal response” to a single 1 ms pulse of the electric field was easily detectable, with an average amplitude of ΔF/F = 100% and decaying with τ = 350 ms. In comparison, a train of 20 pulses at 20 Hz generated a response of ΔF/F = 400% (not shown). Thus, although we could not know how many spikes this “minimal response” reflected, it was far from saturation and provided a kernel by which we could use deconvolution to estimate relative spike rates.

Figure 5. Monitoring synaptic activity in the optic tectum of zebrafish.

(a) Optic tectum of a zebrafish (9 dpf) transiently expressing SyGCaMP2 under the α-tubulin promoter. The red box indicates the area imaged in the head and the white dashed line the midline. For equipment and settings see Supplementary Methods. Scale bar = 100 μm. The white dashed box shows the region zoomed into for recordings shown in (b). Scale bar = 20 μm. (c) ROIs corresponding to single synapses in b. Terminals responding to light are in amber. (d) Raster plot showing 100 SyGCaMP2 signals from terminals marked in c, elicited by an electric field or a light stimulation (e) shown in bottom panels of f or h, respectively. Imaging frequency 20 Hz; 256×50 pixels. (f) Top: SyGCaMP2 signals averaged from 12 terminals (from different area of the tectum, same fish). Middle: Relative Spike Frequency (R.S.F.) calculated by deconvolution using the minimum impulse response (rising and decay time-constants of 50 and 350 ms). Bottom: pattern of field stimulation. (g) R.S.F. plotted against the frequency of electrical stimulation (1 ms pulses) obtained from four different experiments in different areas of the tectum. Note linearity. Error bars: s.e.m. (h) Traces of two SyGCaMP2 signals from amber terminals in c, responding to two identical light stimuli (square wave, 100% modulation at 2 Hz, 50% duty cycle, 590 nm). The amplitude of the light responses do not exceed the average amplitude of the minimal field stimulus. (i) Estimate of the R.S.F calculated by deconvolution of the traces in h.

To allow comparison with results obtained in cultured neurons, the fish was stimulated with the same pulse pattern as in Figure 4a. Figure 5f shows the resulting SyGCaMP2 signal from one trial averaged over the 12 responding synapses, as well as the deconvolution of this trace using the “minimal response” as a kernel to provide the relative spike frequency (RSF). Imaging was carried out at 10 Hz (Supplementary Video 2 online), so the ideal reconstruction (Fig. 5f, bottom) counts spikes in 100 ms time bins. There were several points of agreement between the experimental and idealized reconstructions: single stimuli were detected and variations in the number of stimuli per burst were clearly observed. The accuracy of the reconstruction is summarized in Figure 5g, which plots the RSF against the frequency of the minimal field stimulus (collected results from four different regions of the tectum). SyGCaMP2 signals varied linearly with stimulus frequency, validating the use of deconvolution over this range of activities.

We did not use deconvolution to reconstruct the absolute spike rate from tectal neurons because this would require an electrophysiological calibration of the SyGCaMP2 signal to a single spike, which will vary from cell-to-cell, and even synapse-to-synapse24 (Figs. 2e and f). Further, electrophysiological calibrations of optical signals will not be practical when imaging large numbers of neurons in intact tissues. The more fundamental issue is whether the response of the reporter is linear over the range of activities of the neurons to be studied. Tectal neurons respond to light with sparse bursts of action potentials23, suggesting that deconvolution of SyGCaMP2 signals will be useful for assessing electrical activity driven by a visual stimulus. Figure 5h shows two examples of SyGCaMP2 responses to full-field light modulated at 2 Hz, averaged over the same population of synapses investigated by field stimulation. The peak response did not exceed 130%, falling within the linear range assessed by field stimulation (cf. Fig. 5f and g). Deconvolution using the kernel obtained by field stimulation yielded traces showing the relative spike frequency in Figure 5i. Different presentation of the stimulus generated variable responses, and modulation on a sub-second time-scale was often observed. These results demonstrate that SyGCaMP2 can clearly reveal synaptic activity in vivo, and has the potential to obtain quantitative estimates of the underlying electrical activity of neurons.

While synapses in the optic tectum are activated by fast action potentials and have a conventional structure, ribbon-type synapses in the retina are functionally distinct, transmitting graded voltage signals by continuously modulating the rate of vesicle release25 to provide a wider repertoire of signalling. For instance, bipolar cells use ribbon synapses to transmit signals of different polarities (ON, OFF) and kinetics (sustained, transient), establishing “parallel channels” of information flow26,27. To investigate SyGCaMP2 signals in ribbon synapses we stably expressed the reporter in zebrafish using the ribeye promoter (Fig. 6a).

Figure 6. Monitoring synaptic activity in the retina of zebrafish.

(a) The eye of a larval zebrafish (9 dpf) expressing SyGCaMP2 under control of the ribeye promoter. Photoreceptor terminals appear in the outer plexiform layer (OPL) and bipolar cell terminals in the inner plexiform layer (IPL). Scale bar = 50 μm. (b) The IPL in a different fish (9 dpf) expressing SyGCaMP2 (above) and the ROIs in which SyGCaMP2 signals were measured shown in different colours (below). Scale bar = 20 μm. (c) Graph showing fluorescence responses from 80 terminals shown in b. Two light stimuli (blue; 490nm) were applied: a steady uniform one followed by a flickering one (2 Hz square wave, 100% modulation, 50% duty cycle). Images were collected every 128 ms. (d) Some example traces of different types of SyGCaMP2 responses in terminals from c. The colours and numbers of the traces correspond to the ROIs in b.

An example experiment is shown in Figure 6b-d, in which 80 synaptic terminals in one optical plane were monitored at intervals of 128 ms (Supplementary Video 3 online). The live fish was stimulated with a steady and then flickering (2 Hz) blue light. The majority of terminals showed clear modulation of the presynaptic calcium signal in response to visual stimulation as shown in Figure 6c. A number of different types of responses could be identified (Fig. 6d), including sustained ON responses (a rise in calcium which is maintained in response to a steady light); sustained OFF (a fall in calcium which is maintained in response to a steady light); excitatory responses to contrast but not to the steady light; and transient OFF responses (a fast rise in calcium at offset of the light). Thus SyGCaMP2 allowed us to detect a fall in calcium in neurons that hyperpolarize in response to light as well as a rise in calcium when they depolarized. Such recordings could be made repeatedly over a period of hours in live fish.

Discussion

The targeting of a GECI to the presynaptic terminal provides a new strategy for monitoring the electrical activation of synapses in networks of connected neurons. The sensing of the presynaptic calcium transient controlling neurotransmitter release reports the activation of a synapse with improved sensitivity and temporal resolution compared to reporters such as synaptopHluorin6-8. The underlying electrical activity of a neuron can also be assessed with improved temporal resolution and dynamic range compared to GECIs in the soma. Detecting the time and place of signals transferred across tens to hundreds of synapses simultaneously will help us analyze the structure of neural circuits in relation to their function. GECIs localized to synaptic terminals will also help us understand how modulation of presynaptic calcium signals contribute to changes in circuit function by, for instance, activation of presynaptic receptors that regulate the activation of voltage-dependent calcium channels.

Using calcium reporters to monitor electrical activity is a trade-off between sensitivity and dynamic range: sensitivity requires efficient binding of calcium in response to a single spike, but this reduces the dynamic range of the reporter by saturation at higher levels of activity. For instance, GECIs that report changes in bulk calcium after a single spike saturate after as few as three14. In contrast, we found that the amplitude of SyGCaMP2 signals in small hippocampal synapses was linear with the number of APs up to about 8 at a frequency of 20 Hz, and the reporter remained far from saturation at frequencies of 20 Hz or more (Figs. 3, 4 and Supplementary Figure 1). This property of SyGCaMP2 may appear surprising at first, given that GCaMP2 binds Ca2+ ions with a cooperativity of 4 and a Kd of ~150 nM, but it is readily explained by the simulation in Figure 1c: the rise in presynaptic Ca2+ generated by an action potential is very brief compared to the speed with which Ca2+ binds to GCaMP2, such that each bolus of Ca2+ only occupies a small fraction (<2 %) of GCaMP2 molecules. This conclusion can also be appreciated by considering the mean capture time of a Ca2+ ion entering the presynaptic terminal (τc = Kon−1 × [SyGCaMP2]−1), which has a value of 37 ms assuming a Kon of 26.7 s−1 and a SyGCaMP2 concentration of 1 μM. In comparison, a Ca2+ ion will take just 0.5 ms to travel 0.5 μm and escape the synaptic bouton, assuming a diffusion coefficient of 220 μm2 s−1. Thus, the great majority of Ca2+ ions entering during a spike successfully run the gauntlet of SyGCaMP2 molecules immobilized in the synaptic terminal preventing saturation with Ca2+ ions, even when the neuron is firing at frequencies of tens of Hertz (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Figure 1). The dynamic range of synaptically-localized calcium reporters might be increased further by the generation of brighter proteins with reduced affinities reflecting reduced on-rates for calcium binding.

Neurons in different regions of the nervous system show large variations in electrical activity, so calcium reporters used to monitor this activity will need different sensitivities, dynamic ranges and kinetics, according to the situation. SyGCaMP2 will be suited to monitoring activity in neurons firing at rates below ~10 Hz (Figs. 2 and 3), as in the optic tectum of zebrafish23 (Fig. 5e and h). SyGCaMP2 also reports graded depolarizations and hyperpolarizations in ribbon synapses of the retina, and should be of general use in analyzing this circuit (Fig. 6c and d). Other factors that will determine the signals obtained using synaptically-localized calcium reporters include the geometry and size of the presynaptic compartment, the density of presynaptic calcium channels and the properties of internal calcium buffers, stores and pumps. These factors vary between neurons and within neurons24. Indeed, the ability of SyGCaMP2 to detect spike activity varied across different boutons of the same hippocampal neuron (Fig. 2f) due to variations in the presynaptic calcium signal (Fig. 2e). It is also notable that while the saturating response in cultured neurons was always <100% at 20 Hz (Fig. 3), in tectal neurons in vivo linearity was maintained with responses up to ~300% (Fig. 5e). This difference may reflect greater calcium influx per AP in tectal neurons compared to cultured neurons.

Although SyGCaMP2 allows the locations of active synapses to be identified, it does not immediately relate this information to the morphology of individual neurons. This should become possible by combining SyGCaMP2 with cytoplasmic or membrane-targeted proteins emitting towards the blue or red parts of the spectrum, or perhaps the “Brainbow” approach for defining the morphology of larger numbers of interconnected neurons28. We hope that the localization of a GECI to the presynaptic terminal will provide a general strategy for analysing the functional of connectivity of neural circuits by imaging.

Methods

Molecular Biology

Expression of DNA constructs in rat hippocampal neurons was obtained by transfection using Lipofectamine2000 (Invitrogen), as described previously29. To express GCaMP2 we used the vector pEGFP-N1 (Clonetech) after PCR replacement of EGFP by GCaMP2 from pN1-GCaMP2 (kind gift by Jun-Ichi Nakai, RIKEN) using primers GCaMP2_for and GCamP2_rev (Supplementary Table 2) and BamHI and NotI restriction enzymes. Then we cloned the CMV-SyGCaMP2 construct, for expression in hippocampal cells, in two steps. First, we amplified rat synaptophysin1 cDNA (NM_012664/gi:6981621) by PCR using ratSyp_for and ratSyp_rev primers (Supplementary Table 2) via XhoI and BamHI. Second, we fused GCaMP2 to the c-terminus of rat-synaptophysin1 in the resulting ratSyp-EGFP vector replacing EGFP by PCR amplification with SyG2_for and SyG2_rev primers (Supplementary Table 2) and digestion with BamHI and NotI.

To improve transgenesis of zebrafish by DNA microinjection, we designed plasmids exploiting the advantages of the I-SceI meganuclease co-injection protocol30. For this purpose we cloned at both edges of the multiple cloning site of the original pBluescript II KS+ (Stratagene) a I-SceI recognition site replacing the BssHII cutting sequence by PCR amplification using I-SceI_for and I-SceI_rev primers (Supplementary Table 2).

To obtain the expression of SyGCaMP2 in the zebrafish retina we used a new retinal promoter for the ribeye protein (Odermatt B., unpub. data), and we replaced the Rat synaptophysin with the Zebrafish synaptophysin. First we ligated the ribeye promoter into the AleI and XbaI sites of the I-SceI pBluescript plasmid. Second we amplified the Zebrafish synaptophysin b (NM_001030242/gi:221139917) by PCR amplification using ZfSyp_for and ZfSyp_rev primers (Supplementary Table 2) from the cDNA IMAGE clone 7287035 and cloned into pEGFP-N1 (Clonetech) digested with XhoI and BamHI. Third we digested the Zf synaptophysin-EGFP fragment with NheI and SspI, and we inserted into the I-SceI pBluescript vector behind the ribeye promoter using SpeI and EcoRV. Finally we replaced EGFP by GCaMP2 at the c-terminus of Zf synaptophysin, by digestion with NotI and BamHI as described above. Expression of SyGCaMP2 under the ribeye promoter was stable until fish reach adulthood (6 months).

To obtain expression of SyGCaMP2 in tectal neurons we used the pan-neuronal promoter for α-tubulin with the Gal4/UAS system21. We performed injections using the α-Tublin:Gal4/VP16 plasmid (provided by Martin Meyer as well as the 5UAS:EGFP-N1 vector) and a 5UAS:Zf-SyGCaMP2 plasmid. To obtain the 5UAS:Zf-SyGCaMP2 plasmid we started from the 5UAS:EGFP-N1 vector construct. We digested the 5UAS fragment with AseI and BglII and we inserted into the I-SceI pBluescript vector digested with SacI and BamHI. Then we cut the Zf-SyGCaMP2 fragment from the ribeye:Zf-SyGCaMP2 vector described above with AfeI, AflI, and we inserted behind the UAS fragment of the I-SceI pBluescript vector digested with EcoRV.

Imaging synaptic activity in cultured hippocampal neurons

Primary cultures of hippocampal neurons dissociated from E18 rat pups were prepared using methods approved by the Home Office of the United Kingdom, as previously described13. Cells were transfected after 7 days in vitro using Lipofectamine 2000 in MEM (Invitrogen). During experiments cells were perfused with a buffer (pH 7.4) containing (in mM): 136 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 10 HEPES, 1.3 MgCl2, 10 glucose, 2 CaCl2, 0.01 CNQX and 0.05 DL-APV. CNQX and APV were from Tocris Cookson (Bristol, UK) and other chemicals from Sigma Aldrich (St Louis, MO). When using ionomycin to permeabilize cells to calcium, we replaced NES buffer first with a calcium-free solution containing 10 mM EGTA and 5 μM ionomycin (Sigma), then with 2.5 mM calcium NES buffer with 5 μM ionomycin.

Neurons were imaged after 14 days in vitro using a CCD camera (Cascade 512B; Photometrics) mounted on an inverted microscope (Nikon Diaphot 200; Kawasaki, Japan) with a 40X, 1.3 NA oil immersion objective. Images were captured in Frame Transfer mode at a depth of 16-bits to a Macintosh G4 computer using IPLab software (BD Biosciences). GCaMP2 was imaged with a filter set comprising 475AF40 excitation filter, 505DRLP dichroic mirror and a 535AF45 emission filter (Omega). mRFP-VAMP was imaged using a 560AF55 excitation filter, 595DRLP dichroic mirror and a 645AF75 emission filter. Illumination was controlled via a shutter (Uniblitz VMM-D3 Vincent Associates). In early experiments, a 100 W Xenon arc-lamp was used for illumination and attenuated 4 – 8 x using neutral density filters to minimize photobleaching. This lamp was found to be a high source of noise in measurements and replaced with an LED (Luxeon K2, blue) driven from a constant current source at 1500 mA.

Action potentials (APs) were evoked in a custom-built chamber by field stimulation (20 mA, 1 ms pulses) across two parallel platinum wires 3 mm apart29. Image sequences were obtained at 20 Hz using 45 ms integration times, then imported to Igor Pro (Wavemetrics) and analyzed using custom written macros13. To measure synaptic responses, square regions of interest (ROIs) measuring 2.3 × 2.3 μm were positioned on synapses identified by a SNR greater than 213. To subtract the local background signal, the intensity of an ROI displaced in the x- or y-direction by 2.3 μm was also measured. Signals were quantified as ΔF/Fo, where Fo was measured over the 1 s period before a stimulus was applied. In all graphs, error bars are ± SEM.

Generation of transgenic zebrafish

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) were maintained according to the national law (the Animal Act 1986), Home Office regulations and approved by the MRC-LMB Ethical Review Committee. We grew and kept larvae and embryos as well as adult fish as described previously31 at a 14:10 hour light dark cycle at 28°C and bred naturally. To generate a transgenic line tg(ribeye:Zf-SyGCaMP2) we followed Nusslein-Volhard and Dahm 200231 protocol using wild-type zebrafish with a mixed genetic background, originally purchased from a local pet shop, and fish homozygous for the roy orbison (roy) mutation32. The roy mutants are characterized by a reduced numbers of iridophores which allow high resolution imaging at later ages (up to 2 weeks post-fertilization). Studies on roy mutants do not report abnormalities of the IPL or impaired visual performance tasks.

For the transient expression of the SyGCaMP2 indicator in tectal neurons, we coinjected α-Tubulin:Gal4/VP16 plasmid and the UAS:Zf-SyGCaMP2 plasmid with I-SceI meganuclease (New England Biolabs) into one-cell stage fertilized following Thermes et al. 200230 guidelines. For fish expressing fluorescent proteins we always added PTU (1-phenyl-2-thiourea 200 μM final concentration, Sigma) to the E2 fish medium from 28 hpf on to inhibit melanin formation33. To assess fluorescence expression in the retina we screened embryos using an epifluorescent stereomicroscope (Olympus, X12) between 36 and 48 hpf. In this manner we obtained one transgenic zebrafish line expressing SyGCaMP2 tg(ribeye:Zf-SyGCaMP2).

Imaging synaptic activity in the retina of zebrafish

Larval zebrafish (9-10 dpf) were anesthetized by immersion in 0.016% MS222 (Sigma)and immobilized in 2.5% low melting agarose (Biogene) on a glass slide. For imaging the retina through the pupil, fish were mounted with one eye pointing towards the objective. For imaging the tectum through the skin, they were placed belly down facing forward. Ocular muscles were paralyzed by injection of α-Bungarotoxin (2 mg/ml) next to the eye. Imaging was carried out using a custom-built 2-photon microscope34 equipped with a mode-locked Chameleon titanium-sapphire laser tuned to 915 nm (Coherent). The objective was an Olympus LUMPlanFI 40x water immersion (NA 0.8). The intensities of exciting illumination bleached SyGCaMP2 at rates of ~9% per minute. Emitted fluorescence was captured by the objective and by a sub-stage condenser, and in both cases filtered by a HQ 535/50GFP emission filter (Chroma Technology) before detection by photomultiplier tubes (PMTs; Hamamatsu). Scanning and image acquisition were controlled using ScanImage v. 3.0 software3 running on a PC. Light stimuli were delivered by a blue or amber LED (Luxeon) projected through the objective onto the retina. Electric field stimulation was delivered mounting the fish in the same custom-built chamber used for the hippocampal cells. Timing of stimulation was controlled through Igor Pro v. 4.01 software (WaveMetrics) running on a Macintosh, which also triggerd image acquisition. Image sequences were acquired at 1ms per line using 256x50 or 128×128 pixels per frame and analyzed with custom written macros in Igor Pro (v6.10, WaveMetrics, Lake Oswego, OR, USA) or ImageJ v1.39 (NIH). Regions of interest (ROIs) corresponding to synaptic terminals were defined by transforming images using a Laplace operator followed by thresholding.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank all the members of the lab for discussions. The Virtual Cell is supported by NIH Grant Number P41RR013186 from the National Center For Research Resources. This work was supported by the MRC and the Wellcome Trust.

References

- 1.Garaschuk O, Milos RI, Grienberger C, et al. Optical monitoring of brain function in vivo: from neurons to networks. Pflügers Arch. 2006;453(3):385–396. doi: 10.1007/s00424-006-0150-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gobel W, Helmchen F. In vivo calcium imaging of neural network function. Physiology (Bethesda) 2007;22:358–365. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00032.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pologruto TA, Yasuda R, Svoboda K. Monitoring neural activity and [Ca2+] with genetically encoded Ca2+ indicators. J. Neurosci. 2004;24(43):9572–9579. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2854-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reiff DF, Ihring A, Guerrero G, et al. In vivo performance of genetically encoded indicators of neural activity in flies. J. Neurosci. 2005;25(19):4766–4778. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4900-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mao T, O'Connor DH, Scheuss V, Nakai J, Svoboda K. Characterization and subcellular targeting of GCaMP-type genetically-encoded calcium indicators. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(3):e1796. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miesenbock G, De Angelis DA, Rothman JE. Visualizing secretion and synaptic transmission with pH-sensitive green fluorescent proteins. Nature. 1998;394(6689):192–195. doi: 10.1038/28190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ng M, Roorda RD, Lima SQ, et al. Transmission of olfactory information between three populations of neurons in the antennal lobe of the fly. Neuron. 2002;36(3):463–474. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00975-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bozza T, McGann JP, Mombaerts P, Wachowiak M. In vivo imaging of neuronal activity by targeted expression of a genetically encoded probe in the mouse. Neuron. 2004;42(1):9–21. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00144-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katz B. The Release of Neural Transmitter Substances. Liverpool Univ. Press; Liverpool, England: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koester HJ, Sakmann B. Calcium dynamics associated with action potentials in single nerve terminals of pyramidal cells in layer 2/3 of the young rat neocortex. J. Physiol. 2000;529(Pt 3):625–646. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00625.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tallini YN, Ohkura M, Choi BR, et al. Imaging cellular signals in the heart in vivo: Cardiac expression of the high-signal Ca2+ indicator GCaMP2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103(12):4753–4758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509378103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sinha SR, Wu LG, Saggau P. Presynaptic calcium dynamics and transmitter release evoked by single action potentials at mammalian central synapses. Biophys. J. 1997;72(2 Pt 1):637–651. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(97)78702-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Granseth B, Odermatt B, Royle SJ, Lagnado L. Clathrin-mediated endocytosis is the dominant mechanism of vesicle retrieval at hippocampal synapses. Neuron. 2006;51(6):773–786. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wallace DJ, Borgloh SM, Astori S, et al. Single-spike detection in vitro and in vivo with a genetic Ca2+ sensor. Nat. Methods. 2008;5(9):797–804. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenmund C, Stevens CF. Definition of the readily releasable pool of vesicles at hippocampal synapses. Neuron. 1996;16(6):1197–1207. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80146-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanse E, Gustafsson B. Vesicle release probability and pre-primed pool at glutamatergic synapses in area CA1 of the rat neonatal hippocampus. J. Physiol. 2001;531(Pt 2):481–493. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0481i.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yasuda R, Nimchinsky EA, Scheuss V, et al. Imaging calcium concentration dynamics in small neuronal compartments. Sci. STKE. 2004;2004(219):pl5. doi: 10.1126/stke.2192004pl5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orger MB, Kampff AR, Severi KE, Bollmann JH, Engert F. Control of visually guided behavior by distinct populations of spinal projection neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 2008;11(3):327–333. doi: 10.1038/nn2048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yaksi E, Friedrich RW. Reconstruction of firing rate changes across neuronal populations by temporally deconvolved Ca2+ imaging. Nat. Methods. 2006;3(5):377–383. doi: 10.1038/nmeth874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hieber V, Dai X, Foreman M, Goldman D. Induction of alpha1-tubulin gene expression during development and regeneration of the fish central nervous system. J. Neurobiol. 1998;37(3):429–440. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(19981115)37:3<429::aid-neu8>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koster RW, Fraser SE. Tracing transgene expression in living zebrafish embryos. Dev. Biol. 2001;233(2):329–346. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gahtan E, Baier H. Of lasers, mutants, and see-through brains: functional neuroanatomy in zebrafish. J. Neurobiol. 2004;59(1):147–161. doi: 10.1002/neu.20000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bollmann JH, Engert F. Subcellular topography of visually driven dendritic activity in the vertebrate visual system. Neuron. 2009;61(6):895–905. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brenowitz SD, Regehr WG. Reliability and heterogeneity of calcium signaling at single presynaptic boutons of cerebellar granule cells. J. Neurosci. 2007;27(30):7888–7898. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1064-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Odermatt B, Lagnado L. In: Encyclopedia of Neuroscience. Squire LR, editor. Vol. 8. Elsevier; Oxford: 2009. pp. 373–381. Academic Press, Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baccus SA. Timing and computation in inner retinal circuitry. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2007;69:271–290. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.120205.124451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Masland RH. The fundamental plan of the retina. Nat. Neurosci. 2001;4(9):877–886. doi: 10.1038/nn0901-877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Livet J, Weissman TA, Kang H, et al. Transgenic strategies for combinatorial expression of fluorescent proteins in the nervous system. Nature. 2007;450(7166):56–62. doi: 10.1038/nature06293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Royle SJ, Granseth B, Odermatt B, Derevier A, Lagnado L. Imaging phluorin-based probes at hippocampal synapses. Methods Mol. Biol. 2008;457:293–303. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-261-8_22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thermes V, Grabher C, Ristoratore F, et al. I-SceI meganuclease mediates highly efficient transgenesis in fish. Mech. Dev. 2002;118(1-2):91–98. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00218-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nusslein-Volhard C, Dahm R. Zebrafish. 1st ed. Oxford University Press; Oxford, New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ren JQ, McCarthy WR, Zhang H, Adolph AR, Li L. Behavioral visual responses of wild-type and hypopigmented zebrafish. Vision. Res. 2002;42(3):293–299. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(01)00284-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karlsson J, von Hofsten J, Olsson PE. Generating transparent zebrafish: a refined method to improve detection of gene expression during embryonic development. Mar. Biotechnol. (NY) 2001;3(6):522–527. doi: 10.1007/s1012601-0053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsai PS, Nishimura N, Yoder EJ, et al. In: In Vivo Optical Imaging of Brain Function. Frostig RD, editor. CRC Press; Boca Raton, London, New York, Washington DC: 2002. pp. 113–171. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.