Abstract

Bacterial CopZ proteins deliver copper to P1B-type Cu+-ATPases that are homologous to the human Wilson and Menkes disease proteins. The genome of the hyperthermophile Archaeoglobus fulgidus encodes a putative CopZ copper chaperone that contains an unusual cysteine-rich N-terminal domain of 130 amino acids in addition to a C-terminal copper binding domain with a conserved CXXC motif. The N-terminal domain (CopZ-NT) is homologous to proteins found only in extremophiles and is the only such protein that is fused to a copper chaperone. Surprisingly, optical, electron paramagnetic resonance, and x-ray absorption spectroscopic data indicate the presence of a [2Fe-2S] cluster in CopZ-NT. The intact CopZ protein binds two copper ions, one in each domain. The 1.8 Å resolution crystal structure of CopZ-NT reveals that the [2Fe-2S] cluster is housed within a novel fold and that the protein also binds a zinc ion at a four-cysteine site. CopZ can deliver Cu+ to the A. fulgidus CopA N-terminal metal binding domain and is capable of reducing Cu2+ to Cu+. This unique fusion of a redox-active domain with a CXXC-containing copper chaperone domain is relevant to the evolution of copper homeostatic mechanisms and suggests new models for copper trafficking.

Copper is a meticulously regulated redox-active micronutrient found in a number of important enzymes, including cyto-chrome c oxidase and superoxide dismutase. Because free or excess intracellular copper can cause oxidative damage, both prokaryotes and eukaryotes have developed specific copper trafficking and transport pathways (1, 2). Deficiencies in these processes are linked to human diseases, including Wilson and Menkes disease. In Wilson disease, accumulation of copper in the liver and brain leads to cirrhosis and neurodegeneration, and in Menkes disease, copper transport across the small intestine is impaired, leading to copper deficiency in peripheral tissues (3, 4). Both disorders are caused by mutations in Cu+-transporting P1B-type ATPases (5–7), enzymes that are found in most organisms and function in the cellular localization and/or export of cytosolic copper (8, 9).

The Cu+-ATPases include eight transmembrane (TM)4 helices, of which three (TM6, TM7, and TM8) contribute invariant residues to form the transmembrane metal-binding site, a cytosolic ATP binding domain linking TM6 and TM7, an actuator domain between TM4 and TM5, and cytosolic metal binding domains (MBDs) of ~60–70 amino acids that bind Cu+ (8,10). Whereas prokaryotic Cu+-ATPases typically have one or two MBDs, eukaryotic homologs have up to six such domains. Each MBD contains a highly conserved CXXC consensus sequence for binding Cu+ and adopts a βαββαβ fold (11–14) nearly identical to that of the Atx1-like cytosolic copper chaperones, including yeast Atx1, human Atox1, and bacterial CopZ (15–19). These chaperones also contain a CXXC motif and deliver Cu + to one or all of the MBDs (20–26). It is not clear how Cu+ reaches the transmembrane metal-binding site and how the cytosolic chaperones participate in this process.

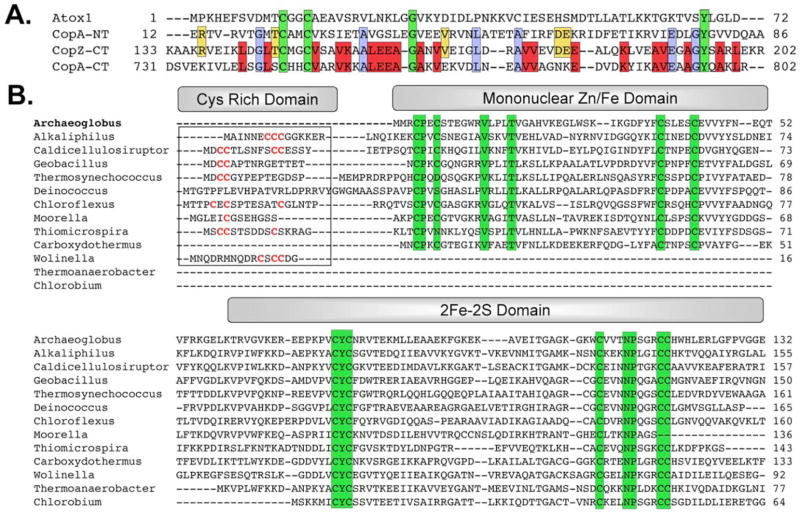

The hyperthermophilic Cu+-ATPase CopA from Archaeoglobus fulgidus is readily expressed in fully active recombinant form, is highly stable, and contains all of the essential structural elements for copper transfer, including one N-terminal and one C-terminal MBD (27–29). CopA is therefore an excellent model system both for investigating the mechanisms of P1B-type ATPases and for studying interactions between a cytosolic chaperone and its intact partner Cu+-ATPase. The only potential copper chaperone protein in the A. fulgidus genome, which we have designated A. fulgidus CopZ, differs from all other known copper chaperones in that it contains an additional 130 amino acids fused to the N terminus of a 60-residue CXXC-containing sequence that is homologous to Atx1-like chaperones and Cu+-ATPase MBDs (Fig. 1A). Notably, the A. fulgidus CopA C-terminal metal binding domain (CopA C-MBD) is the most similar to the CopZ C terminus, with 42% identity. The CopA N-terminal MBD (CopA N-MBD) is only 20% identical to CopZ. The novel N-terminal domain of CopZ (CopZ-NT) contains nine conserved cysteine residues and resembles uncharacterized 10–15-kDa proteins from other extremophilic Archaea (Fig. 1B). The A. fulgidus protein is the only one in which this domain is fused to a putative copper chaperone, however. In all the other extremophilic organisms that have a CopZ-NT homolog, the putative copper chaperone exists as a separate 70-amino acid protein, and its gene is not located in an operon with that encoding a CopZ-NT homolog, suggesting that their expression might not be linked.

FIGURE 1. Sequence alignment to the A. fulgidus CopZ domains.

A, CopZ C-terminal domain sequence alignment to the A. fulgidus CopA N- and C-terminal MBDs and to human Atox1. Completely conserved residues are highlighted green; residues conserved among the A. fulgidus proteins are highlighted blue; residues conserved between CopZ-CT and CopA-NT are highlighted yellow; and residues conserved between CopZ-CT and CopA-CT are highlighted red. B, N-terminal domain sequence alignment. Sequences of homologous proteins used for the alignments were from the following species: A. fulgidus DSM 4304 (NP_069182.1), Alkaliphilus metalliredigenes QYMF (EAO82573.1), Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus DSM 8903 (EAP42583.1), Carboxydothermus hydrogeno-formans Z-2901 (YP_359666.1), Moorella thermoacetica ATCC 39073 (YP_429978.1), Deinococcus geothermalis DSM 11300 (ZP_00398040.1), Geobacillus kaustophilus HTA426 (YP_146024.1), Chloroflexus aurantiacus J-10-fl (EAO58988.1), Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis MB4 (NP_623988.1), Thiomicrospira crunogena XCL-2(YP_392381.1), ThermosynechococcuselongatusBP-1 (NP_682675.1), ChlorobiumtepidumTLS (NP_662049.1), and Wolinella succinogenes DSM 1740 (NP_906973.1). The GenBank™ accession numbers are in parentheses.

Here we describe the characterization and 1.8 Å resolution crystal structure of the A. fulgidus CopZ N terminus (CopZ-NT). Surprisingly, CopZ-NT contains a [2Fe-2S] cluster and a mononuclear zinc site. The fusion of a redox-active domain with a CXXC-containing copper chaperone is unprecedented and suggests previously unrecognized paradigms for copper trafficking and regulation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning and Purification of CopZ and the CopA N-terminal MBD

The gene encoding CopZ (AF03456, GenBank™ accession number NP_069182) was cloned from A. fulgidus genomic DNA by PCR using the primers 5′-ATGATGCGAT-GCCCAGAATG-3′ and 5′-TCTCTTTCAAGCCGTGCAGA-3′. The purified gene and the plasmid pPRIBA1 (IBA, Germany) were digested with the restriction enzyme BsaI, purified, and ligated to create the plasmid pCOPZ, which fuses a 10-amino acid (SAWSHPQFEK) Strep-Tactin tag to the C terminus of the expressed gene product. The gene encoding CopZ was also cloned into pBAD/TOPO vector (Invitrogen) using the primers 5′-ATGATGCGATGCCCAGAATG-3′ and 5′-TCTCTTT-TCAAGCCGTGCAGA-3′ to attach a His6 tag to the CopZ N terminus. The N-terminal domain of CopZ (residues 1–131, CopZ-NT) was PCR-amplified from the pCOPZ plasmid by using the primers 5′-CGGGAAGGTCTCTGCGCTTC-CAACGGG-AAATCC-3′ and 5′-GCCCTTGGTCTCTAAT-GATCGATGCCCAGAAT-3′, which encode for a BsaI restriction site. As described above, the gene was inserted into the pPRIBA1 plasmid to create pCOPZNT. The C-terminal CXXC-containing copper chaperone domain (residues 132–204, CopZ-CT) was PCR-amplified from the pCOPZ plasmid to include the Strep-Tactin tag by using the primers 5′-GGAAT-TCCATATGGGTGAGAAGAAAGCGGCTAAAAG-3′ and 5′-CCGCTCGAGTTATTTTTCGAACTGCGGGTGGCTC-CAAGC-3′, which incorporate 5′ NdeI and 3′ XhoI restriction sites. The purified gene product and a pET21b plasmid (Novagen) were digested, purified, and combined to create the pCOPZCT vector. The CopA N-MBD (residues 16–87) was cloned into a pASK-IBA3 vector after PCR amplification with the primers 5′-GCCCTTGGTCTCTAATGGAAAGAACCG-TCAGAGTTAC-3′ and 5′-CGGGAAGGTCTCTGCGCTAG-CAGCTTGCTCATCCACCACAC-3′ as described above to create the construct pCOPANT.

BL21Star(DE3)pLysS Escherichia coli cells carrying the plasmid pSJS1240 encoding for rare tRNAs (tRNAArgAG(A/A)GG and tRNAIleAUA) were transformed with the pCOPZ and pCOPZNT and pCOPANT constructs. BL21(DE3)pLysS E. coli cells (Stratagene) were transformed with the pCOPZCT plasmid, and the His6-tagged CopZ construct was inserted into E. coli TOP10CP cells. All cell types were grown in Luria-Bertani media at 37 °C in the presence of 100 mg/liter carbenicillin and 20 mg/liter chloramphenicol. Media for cells harboring the pSJS1240 plasmid were supplemented with 70 mg/liter spectinomycin. At an A600 of ~0.6–0.7, protein expression was induced by adding either 100–500 μM isopropyl β-D-thiogalac-topyranoside to cells containing the pPRIBA1 and pET21 vectors, 200 μg/liter tetracycline to cells containing the pASK-IBA3 vector, or 0.02% arabinose to cells expressing His6-tagged CopZ from the pBAD/TOPO vector. For cells expressing CopZ or CopZNT, 100 μM ferrous ammonium sulfate was added to the media at induction and every hour thereafter. This addition helped to produce higher quantities of fully metal-loaded protein. The addition of 100 μM CuSO4 to the media yielded protein containing < 0.1 equivalent of copper and did not appear to toxic to the cells as judged by the growth rate and quantity of cell paste. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 6000 × g for 5 min 3–4 h after induction. The pellet was washed with 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, 100 mM KCl, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until further use. Full-length CopZ was also expressed as described above in cells grown in minimal media supplemented with 100 μM iron ammonium sulfate that contained less than 10 μM zinc.

Streptactin-tagged CopZ, CopZ-NT, CopZ-CT, and the CopA N-MBD were purified by using a procedure identical to the one described for the A. fulgidus CopA ATP binding domain (29) except that 1 mM DTT was added to all of the buffers. The His6-tagged CopZ was purified on a nickel-nitrilo-triacetic acid column (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The purified protein was either exchanged into 20 mM MOPS, pH 7.0, 20 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 5% glycerol by several concentration and dilution steps using an Amicon Ultra YM-10 or YM-5 concentrator or into 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT by using a Sephadex G-25 column. The proteins were frozen at 30 mg/ml in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until further use. Protein concentrations were estimated by using the Bradford assay (Sigma).

Site-directed Mutagenesis

Site-directed mutagenesis was performed by using the QuikChange method (Stratagene) and the pCOPZ vector. The DNA primers for 9 single Cys to Ser mutations in the N terminus are listed in Table 1. Mutations were verified by DNA sequencing. All CopZ mutants were expressed and purified from BL21Star(DE3)pLysS E. coli cells containing the pSJS1240 plasmid using the procedures described above.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide primers for site-directed mutagenesis of CopZ

| C4S | 5′-ATGATGCGAAGCCCAGAATGCAGCACGGAAG |

| C7S | 5′-GATGCCCAGAAAGCAGCACGGAAGGATGGAG |

| C38S | 5′-GGATTTTTACTTCAGCTCTTTGGAGAGCTGCGAGG |

| C43S | 5′-CTGCTCTTTGGAGAGCAGCGAGGTTGTTTACTTC |

| C75S | 5′-CAAAGCCGGTTAGCTACTGCAACAGGGTTACAGAG |

| C77S | 5′-CAAAGCCGGTTTGCTACAGCAACAGGGTTACAGAG |

| C109S | 5′-CAGGAAAAGGAAAATGGAGCGTCGTTACCAACCCATC |

| C118S | 5′-CATCCGGGAGAAGCTGCCACTGGCATCTGG |

| C119S | 5′-CATCCGGGAGATGCAGCCACTGGCATCTGG |

Metal Binding Analysis

Apo-forms of the proteins were loaded with Cu+ by incubation with a 10 molar excess of CuCl2 or CuSO4 in 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, or 25 mM MOPS, pH 7.0, 25 mM NaCl, 5 mM DTT for 10–60 min at room temperature with gentle agitation. The unbound copper was removed by centrifuging in a 10-kDa cutoff Centricon Amicon-15 (Millipore, MA) after diluting the sample with 15–20 volumes of buffer without DTT or desalting over a PD-10 column (Bio-Rad).

The amount of bound copper was determined by the BCA method (30). Briefly, the proteins were precipitated by mixing up to 55 μl of sample with 18.3 μl of 30% trichloroacetic acid. The pellet was separated by centrifugation for 5 min at 9,000 × g. The supernatant (66 μl) was mixed with 5 μl of 0.07% freshly prepared ascorbic acid and 29 μl of 2 × BCA solution (0.012% BCA, 7.2% NaOH, 31.2% HEPES). After a 5-min incubation at room temperature, the absorbance at 359 and 562 nm was measured. CuCl2 solutions were used as standards. Concentrations of 2–10 μM Cu+ were within the linear range.

The iron content was determined by using a ferrozine assay (31), and acid-labile sulfide was quantified by using the method of Beinert (32). Zinc content was determined by flame atomic absorption spectrometry and by ICP atomic emission spectrometry. The results of three measurements were averaged, and the concentration was determined from a standard curve.

The presence of various metal ions was also investigated by using x-ray fluorescence spectroscopy at the sector 5 beamline at the Advanced Photon Source. A small sample of 2 mM CopZ in 25 mM Tris, pH 7.5,100 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol was frozen at 100 K on a standard protein crystal mounting loop and exposed to x-rays tuned to the absorption edges of iron, cobalt, nickel, copper, zinc, and tungsten.

Cu+ Transfer between CopZ and the CopA N-MBD

Apo-CopA N-MBD was incubated with Strep-Tactin resin in a column for 20 min at room temperature with gentle agitation. To separate unbound protein, the column was washed with 10 volumes of buffer W (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM ascorbic acid). His6-tagged CopZ loaded with 1.8 ± 0.1 Cu+ was added in 6.6-fold excess to the column containing bound CopA N-MBD and incubated for 10 min at room temperature to initiate copper exchange. The proteins were then separated by washing the column with 10 volumes of buffer W followed by elution of the CopA N-MBD with buffer W containing 2.5 mM 2-(4-hydroxyphenylazo)benzoic acid. Both the wash and elution fractions were collected and analyzed for copper and protein content. To confirm that only the CopA N-MBD was present in the elution fractions, each fraction was analyzed by SDS-PAGE. As a control, copper-loaded CopZ incubated with Strep-Tactin beads without bound CopA N-MBD was subjected to the procedure described above and demonstrated no copper loss. Strep-Tactin-bound apo-CopA N-MBD incubated with just buffer W did not acquire copper either.

Reduction of Cu2+ by CopZ

Under anaerobic conditions, 1 mM CopZ and CopZ-NT in 25 mM MOPS, pH 7.0, 25 mM NaCl were reduced with 4-fold excess dithionite and desalted on a PD-10 column (Bio-Rad) equilibrated with 50 mM Tris, pH 7.0, 50 mM NaCl. A 10-fold excess of BCA and a 3-fold excess of CuSO4 were then added to the eluted protein and allowed to incubate for 4 h at 25 °C to detect the reduction of Cu2+ to Cu+ colorimetrically. As a control, 1 mM CopZ and CopZ-NT in 25 mM MOPS, pH 7.0, 25 mM NaCl were oxidized with 10 mM K3Fe(CN)6 under aerobic conditions, desalted, moved into the anaerobic chamber, and incubated with BCA and CuSO4 as described above. No color change was observed.

X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy

XAS samples were prepared anaerobically and aerobically for as purified (oxidized) and dithionite-reduced CopZ and CopZ-NT. Multiple independent but reproducible samples that did not contain copper were prepared at 2.0–5.0 mM iron concentrations in 100 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 30% glycerol and transferred into Lucite sample cells wrapped with Kapton tape. Samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Iron XAS data for full-length CopZ were collected at Brookhaven National Laboratory (NSLS) beamline X-9B using a Si(111) crystal monochromator equipped with a harmonic rejection mirror. Samples were kept at 24 K using a helium Displex cryostat, and protein fluorescence excitation spectra were collected using a 13-element germanium solid-state detector. Spectra were collected with a iron foil control in a manner described previously (33). During data collection, each spectrum was closely monitored for photoreduction. The data represent the average of 7–10 scans.

XAS data were analyzed using the Macintosh OS X version of the EXAFSPAK program suite (available on line) integrated with the Feff version 7.2 software (35) for theoretical model generation. Processing methods and fitting parameters used during data analysis are described in detail elsewhere (33, 36). Single scattering theoretical models were used during data simulation. Data were simulated over the spectral k range of 1 to 12.85 Å−1, corresponding to a spectral resolution of 0.13 Å (37). When simulating empirical data, only the absorber-scatterer bond length (R) and Debye-Waller factor (σ2) were allowed to freely vary, whereas metal-ligand coordination numbers were fixed at quarter-integer values. The criteria for judging the best fit simulation and for adding ligand environments included a reduction in the mean square deviation between data and fit (F′) (38), a value corrected for number of degrees of freedom in the fit, bond lengths outside the data resolution, and all Debye-Waller factors having values less than 0.006 Å2.

EPR Spectroscopy

Dithionite-reduced and as-isolated 2 mM CopZ and CopZ-NT samples in 100 mM Tris, pH 7.0–10.0,150 mM NaCl, 20–30% glycerol were frozen in liquid nitrogen in 3-mm inner diameter quartz EPR tubes. Cryoreduction was achieved by γ-irradiation of the samples by exposure to a 60Co source at a dose rate of 0.46 megarad h−1 for 5–10 min. Cryo-genically reduced samples were annealed in cooled isopentane at various times and temperatures before being rapidly cooled to 77 K. X-band EPR spectra were recorded between 2 and 20 K on Bruker ESP300 or EMX spectrometers equipped with an Oxford Instrument ESR900 liquid helium cryostat.

Structure Determination of the CopZ N Terminus

CopZ-NT was crystallized in a Coy anaerobic chamber at room temperature by using the sitting drop vapor diffusion method. Equal volumes of protein at ~ 15 mg/ml in 20 mM MOPS, pH 7.0, 20 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 1 mM DTT were combined with a crystallization buffer comprising 100 mM sodium acetate, pH 4.6,200 mM ammonium sulfate, 15–20% PEG 2000 MME. Dark red crystals grew within 2 days. The crystals were flash-frozen aerobically in a cryosolution consisting of 75 mM sodium acetate, pH 4.6,100 mM ammonium sulfate, 20% PEG 2000 MME, 20% glycerol. Native and iron anomalous data were collected at 100 K to 2.3–1.8 Å resolution at the Advanced Photon Source on the sector 19 and 23 beamlines (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Data collection, phasing, and refinement statistics

| Data collection | Iron peak | Native |

|---|---|---|

| APS beamline | GM/CA-CAT (sector 23) | SBC-CAT (sector 19) |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.74 | 0.979 |

| Resolution (Å)a | 40.0-2.3 | 50.0-1.78 |

| Unique observations | 13,948 | 29,750 |

| Total observations | 195,626 | 194,503 |

| Completeness (%) | 100 (100) | 98.9 (93.3) |

| Redundancy | 14.0 (14.0) | 6.5 (4.6) |

| I/σ | 19.4 (19.3) | 13.0 (3.2) |

| Rsymb(%) | 6.8 (16.8) | 6.3 (45.1) |

| Iron sites used for phasing | 4 | |

| Figure of merit (after density modification) | 0.374 (0.897) | |

| Refinement | ||

| Rwork (%)c | 20.9 | |

| Rfree (%)d | 23.5 | |

| Molecules per asymmetric units | 2 | |

| No. of protein non-hydrogen atoms | 2066 | |

| No. of protein non-hydrogen atoms | 157 | |

| r.m.s.d. bond length (Å) | 0.0048 | |

| r.m.s.d. bond angle (°) | 1.14 | |

| Average B-value (Å2) | 37.7 | |

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell (1.84 to 1.78 Å).

Rsym = Σi Σhkl|Ii(hkl) − 〈I(hkl)〉|/Σhkl〈I(hkl)〉 where Ii(hkl) is the ith measured diffraction intensity, and 〈I(hkl)〉 is the mean of the intensity for the Miller index (hkl).

Rwork = Σhkl|Fo(hkl)| − |Fc(hkl)||/Σhkl|Fo(hkl)|.

Rfree = Rwork for a test set of reflections (5%).

After data collection, sections of the crystal exposed to the x-ray beam turned yellow, suggestive of photoreduction. The crystals belonged to the space group P212121 and had unit cell dimensions of a = 56.25, b = 64.50, c = 84.15. Data sets were indexed and scaled with HKL2000 (39), and SOLVE (40) and CNS (41) were used to locate 4 iron atoms and calculate and refine phases to 2.3 Å resolution by the SAD method. After density modification, ARP/wARP was used for automatic model building (42). The remainder of the model was built with XtalView (43) and refined with CNS. Residues 1–130 were observed in one molecule in the asymmetric unit, and residues 2–130 were observed in the second molecule. A Ramachandran plot calculation with PROCHECK (44) indicated that 90% of the residues have the most favored geometry, and the rest occupy additionally allowed regions. The root mean square difference (r.m.s.d.) for backbone atoms between the two molecules in the asymmetric unit is 0.3 Å, and no significant structural differences were observed.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Metal Content of CopZ

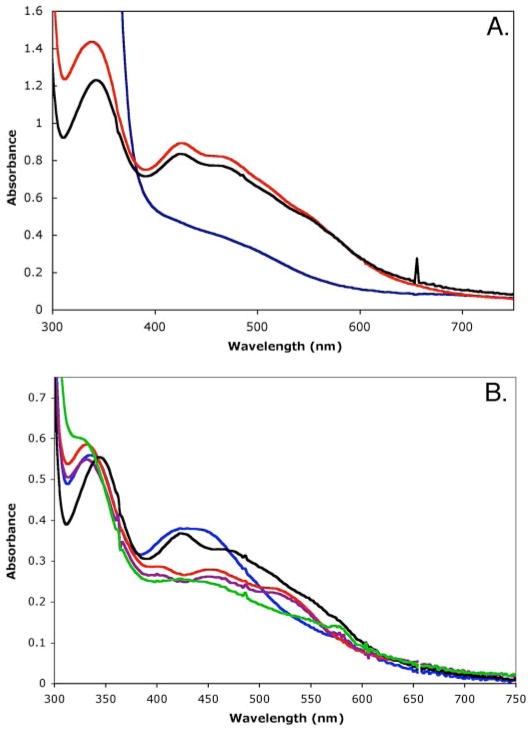

Purified CopZ and CopZ-NT are 23- and 14-kDa monomers, respectively, that have a distinct red color, whereas the 9-kDa CopZ-CT is colorless. The optical spectra of the full-length protein and CopZ-NT are identical with three absorption peaks at 340,430,480 nm and a shoulder at 550 nm (Fig. 2A). The spectra are most similar to those observed for [2Fe-2S]-containing proteins (45). Features attributable to either a mononuclear iron center or a [4Fe-4S] cluster are not present. Upon reduction with dithionite, these spectral features disappear. Because the spectra of CopZ and CopZ-NT are identical, it is likely that the C terminus is not involved in assembly of the CopZ-NT metal centers. Consistent with a [2Fe-2S] cluster, both CopZ and CopZ-NT bound 1.7 ± 0.3 iron ions per protein molecule. Full-length CopZ contained ~ 0.6 eq of zinc, and the isolated CopZ, CopZ-NT, and CopZ-CT did not contain copper. Only zinc and iron were detected by x-ray fluorescence spectroscopy.

FIGURE 2. UV-visible absorption spectra of CopZ, CopZ-NT, and Cys-to-Ser mutants.

A, spectra of wild type (black), dithionite-reduced wild type (blue), and CopZ-NT (red). B, spectra of C75S (red), C77S (blue), C109S (purple), C118S (black), and C119S (green) variants. All spectra were recorded on 60–80/LIM protein in 25 mM MOPS, pH 7.0, 25 mM NaCl at room temperature on a Hewlett Packard 8452A diode array spectrophotometer. Anaerobic measurements were obtained by using a custom designed Thunberg cuvette.

Copper Binding, Transfer, and Reduction

After incubation with excess CuSO4 and DTT and buffer exchange, CopZ, CopZ-NT, and CopZ-CT were determined to bind 2.1 ± 0.3, 1.4 ± 0.3, and 1.0 ± 0.4 Cu+ ions/protein, respectively. Thus, each domain binds a single Cu+ ion. Like all of the other Atx1-like proteins, CopZ-CT likely binds Cu+ via the conserved cys teines in the CXXC motif (see below). The presence of a Cu+ ion bound to CopZ-NT is unexpected.

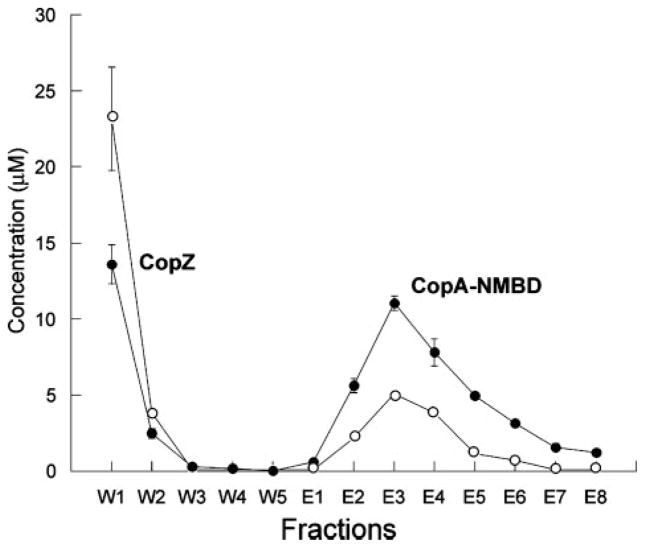

Copper transfer from His6-tagged CopZ to the CopA N-MBD was demonstrated by incubating Cu+-loaded chaper-one with Strep-Tactin resin containing bound apo-CopA N-MBD, separating the individual proteins, and analyzing the copper content (Fig. 3). The CopA N-MBD was selected for these experiments because mutagenesis data indicate that the N-MBD, but not the C-MBD, is important for CopA activity (46). His6-tagged CopZ bound 2.0 ±0.1 copper ions per protein, similar to the value obtained for Strep-Tactin-tagged CopZ. Thus, the His6 tag likely does not interfere with Cu+ binding. When eluted from the column, 34.5% of the CopA N-MBD was loaded with copper. In control experiments, copper-loaded CopZ incubated with Strep-Tactin beads and treated as above did not release copper and retained its full complement. Likewise, Strep-Tactin-bound apo-CopA N-MBD did not acquire copper after washing and elution steps in the absence of CopZ. Because there is no apparent copper loss or gain in the control experiments, CopZ is therefore capable of delivering Cu+ to the CopA N-MBD, similar to what has been reported for yeast and human Atx1-like chaperones and their cognate Cu+-ATPases (24, 25, 47). However, when comparing Cu+ transfer in these various systems, the 80–100 °C optimal growth conditions of A. fulgidus should be considered. Thus, a temperature dependence of Kex might explain the reduced Cu+ transfer (34.5%) observed in A. fulgidus compared with eukaryotic systems (60–90%) (24, 25, 47).5

FIGURE 3. Copper transfer from CopZ to the CopA N-MBD.

The copper (○) and protein (●) content of the wash (W) and elution (E) fractions are shown. Peaks corresponding to specific proteins eluted from the Strep-Tactin column are identified on the figure. At the end of the experiment, 34.5% of the CopA N-MBD was loaded with copper.

To test whether CopZ and CopZ-NT can reduce Cu2+ to Cu+, chemically oxidized and reduced protein were incubated with CuSO4 and bicinchoninic acid (BCA), a Cu+ specific che-lator. A magenta Cu+-BCA complex was only observed when reduced CopZ and CopZ-NT were added to the CuSO4/BCA solution (data not shown). Thus, the in vitro reduction of Cu2+ by the CopZ [2Fe-2S] cluster is favorable and consistent with known redox potentials for Cu2+/Cu+ (154 mV) and [2Fe-2S]2+/[2Fe-2S]+ (200–500 mV) (48). A protein environment, however, can significantly affect the potential of bound copper ions (49), so whether CopZ reduces Cu2+ in vivo would depend on the source of Cu2+.

X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy

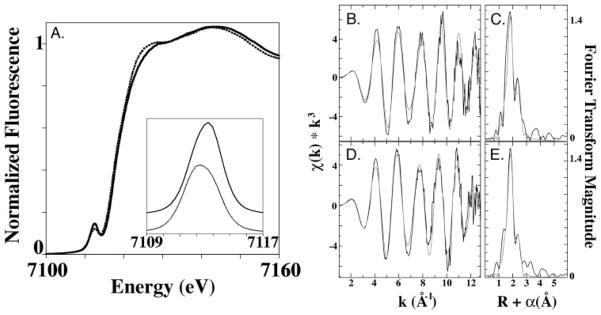

A comparison of the Fe XANES spectra of CopZ in the presence and absence of dithionite is consistent with partial reduction of the [2Fe-2S] cluster. General edge features for the two protein samples differ in their edge first inflection energies (7117.0 eV for reduced and 7117.5 eV for oxidized, see supplemental Fig. S1) as well as a diminished shoulder feature for the oxidized sample at ~ 7125 eV (Fig. 4A). Features for the 1s→3d pre-edge signal occur at maximal values of 7112.2 eV for the reduced sample and 7112.6 eV for the oxidized sample. Concurrent with a subtle shift in the 1s→3d pre-edge maximal signal energy is an increase in area for this signal from 22.1 to 27.3 (unitless values), consistent with four-coordinate ferrous and ferric iron values obtained from model compounds (50).

FIGURE 4. Iron XAS spectra of CopZ.

Normalized XANES spectra for the as purified, oxidized (solid line), and dithionite-reduced(dotted line) CopZ samples (A). The inset shows the expansion of the background subtracted pre-edge feature for the two samples. The extended x-ray absorption fine structure and Fourier transforms (FT) of the CopZ iron-sulfur cluster with best fits superimposed in gray for oxidized (B and C) and reduced (D and E) CopZ samples are shown.

Analysis of the EXAFS data for reduced and oxidized CopZ indicates a unique metal-ligand coordination geometry for both samples with trends matching those expected for Fe-S cluster centers in slightly different redox states. The EXAFS of both samples show a node in the scattering oscillations at a k value of 7.5 Å−1, consistent with destructively interacting distinct ligand environments (Fig. 4, B and D). Fourier transforms of the EXAFS data for both samples show two ligand scattering environments at phase-shifted bond lengths of ~ 1.8 and 2.4 Å, as well as minimal long range (>3.0 Å) scattering (Fig. 4, C and E). Simulations of the iron EXAFS indicate two distinct ligand scattering interactions are present in both samples (Table 3). For the oxidized sample, the data are best fit with approximately four Fe-S interactions at 2.26 Å and a single Fe-Fe interaction at 2.73 Å. For the reduced sample, the data are best fit with approximately four Fe-S interactions at an extended distance of 2.29 Å and a single Fe-Fe interaction at an extended distance of 2.77 Å. There was no justification for fitting the long range (>3.0 Å) scattering in either data set.

TABLE 3.

Summary of iron-extended x-ray absorption fine structure fitting results for CopZ (data fit over k range of 1–12.85 Å−1)

| Sample | Fit no. | Ligand environmenta |

Ligand environmenta |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atomb | R (Å)c | Coord. no.d | σ2e | Atomb | R (Å)c | Coord. no.d | σ2e | F′f | ||

| CopZ-ox | 1.1g | S | 2.26 | 3.5 | 5.85 | 2.20 | ||||

| 1.2g | S | 2.26 | 3.25 | 5.59 | Iron | 2.73 | 1.0 | 3.68 | 1.20 | |

| CopZ-red | 2.1g | S | 2.29 | 3.5 | 5.58 | 1.39 | ||||

| 2.2g | S | 2.29 | 3.5 | 5.66 | Iron | 2.77 | 0.8 | 4.80 | 0.89 | |

Independent metal-ligand scattering environment is shown.

For scattering atoms, S is sulfur.

Metal-ligand bond length is given.

Metal-ligand coordination number is given.

Values are the Debye-Waller factor in Å2 × 103.

The number of degrees of freedom weighted mean square deviation between data and fit is shown.

Fit is by using only single scattering Feff 7 theoretical models.

EPR Spectroscopy

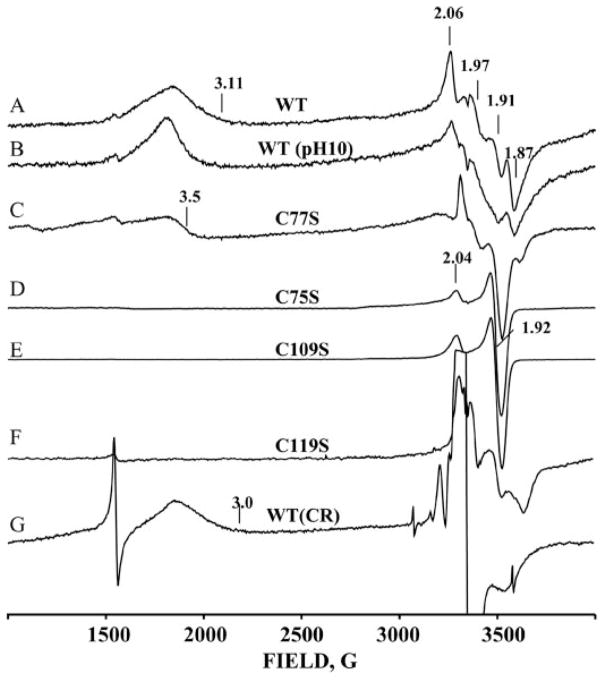

As purified, CopZ is EPR silent. The dithionite-reduced protein exhibits a 10 K EPR spectrum with two different types of signal (Fig. 5), indicating the presence of two major conformational substrates. The first is the signal in the vicinity of g = 2 (~ 3500 G), which corresponds to an S = ½ ground state of the reduced cluster. Spectra collected over a range of temperature, ~ 7–40 K, show that this includes the signals from two “second tier” substrates with ferredoxin-type, rhombic spectra g1 = (2.06, 1.91, 1.86) (gav = 1.94) and g2 = (2.04, 1.97, 1.90) (gav = 1.97). The second type of signal (the “g = 3” signal) is associated with S >½; it is axial with g⊥ = 3.11 and g|| = 1.85 (not resolved). These values are uncommon for [2Fe-2S]+ clusters, and the spin state of the cluster is by no means clear. The high spin signal accounts for ~60% of the reduced [2Fe-2S]+ centers, as estimated by double integration of the EPR spectrum using Labcalc software. Varying the pH between 6 and 10 slightly alters both types of spectrum (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5. EPR spectra of CopZ.

A chemically reduced CopZ, pH 7.0; B, chemically reduced CopZ, pH 10; C, C77S variant; D, C75S variant; E, C109S variant; F, C119S variant; G, after 77 K cryoreduction (CR) of diferric CopZ. Sharp feature at ~ 1500 G in some spectra is non-heme Fe(III). The sharp feature at ~ 1500 G in some spectra is non-heme Fe(III). Conditions are as follows: T=10 K; frequency, 9.372 GHz; power, 1 milliwatt; modulation amplitude, 5 G. WT, wild type.

To investigate the [2Fe-2S] cluster further and to identify the coordinating residues, nine Cys-to-Ser mutants were generated. All of the purified mutants are red in color, indicating that the [2Fe-2S]-containing domain is assembled and folded. The UV-visible spectra for four Cys mutants, C75S, C77S, C109S, and C119S, are different from the wild type spectra, whereas Cys to Ser mutations at positions 4, 7, 38,43, and 118 exhibited UV-visible spectra identical to the native protein (Fig. 2B). The C75S, C109S, and C119S mutations lead to the complete disappearance of the “g = 3” signal (Fig. 5, D–F). The C75S and C109S mutants also collapse the overlapping S = ½ signals into a single axial ferredoxin-like signal with gav < 2, whereas the C119S mutation leaves the S = ½ region of the spectrum as an overlap of two signals (Fig. 5, D–F). The C77S mutant exhibits both types of the signal, but both types are slightly altered (Fig. 5C). Although additional experiments are required to understand why the mutations alter the EPR spectrum, it is possible that a deprotonated serine coordinates to an iron atom or that Cys-118 now participates in cluster formation.

It was demonstrated previously that γ-irradiation at 77 K of diamagnetic diiron(III) centers of frozen protein solutions generates a one-electron reduced product trapped in the conformation of the oxidized precursor (51). The species trapped at 77 K relaxes to an equilibrium state during annealing at elevated temperatures (T> 160 K). Such cryoreduced proteins provide a sensitive EPR probe of the EPR-silent diferric precursors. The EPR spectrum of cryoreduced CopZ (Fig. 5G) shows well resolved features from the high spin conformer, at g = 3.0 and 1.9, which differ from those of the equilibrium conformation. The strong g = 2 signal from radiolytically generated radicals partially obscures the region of the signals of the S = ½ conformers. However, comparison with the spectrum of the chemically reduced protein shows that there are features in the cryo reduction spectrum that would be observable if the S = ½ signals were present, and they are not. Thus, the g = 3 species is the major product of cryoreduction, suggesting that the diferric cluster exists as only one major substrate. The EPR spectrum of the cryoreduced sample annealed at 240 K (not shown) becomes identical to that of the chemically reduced protein (Fig. 5A), showing that the g = 3 conformational substrate can convert to the S = ½ substrate.

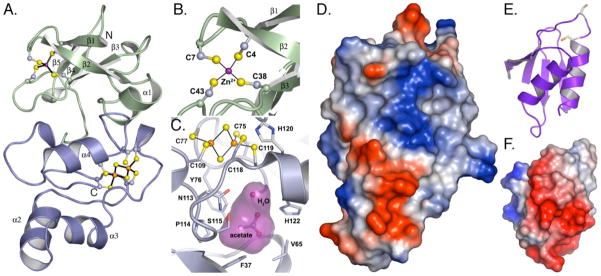

Structure of CopZ-NT

CopZ-NT is composed of two sub-domains, an N-terminal domain containing a mononuclear metal center and a C-terminal domain containing the [2Fe-2S] cluster (Fig. 6A). This distinct domain arrangement is consistent with the observation that the Wolinella, Thermoanaer-obacter, and Chlorobium CopZ-NT sequences lack an N-terminal domain (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, other homologs have an additional N-terminal cysteine-rich region that is not present in A. fulgidus CopZ (Fig. 1B). The folds of the two CopZ-NT sub-domains are unique with no similarity to previously determined structures in the Protein Data Bank according to DALI searches (52).

FIGURE 6. Crystal structure of CopZ-NT.

A, N-terminal domain of CopZ-NT is shown in green, and the C-terminal domain is shown in blue. The zinc ion is shown as a purple sphere, and the [2Fe-2S] cluster is shown as yellow and orange spheres. B, [2Fe2S] cluster. Atoms are represented as ball and sticks with carbon in gray, sulfur in yellow, and iron in orange. Acetate and water are bound in a small cavity (magenta) directly below the [2Fe-2S] cluster. Residues contributing to the surface of the cavity are shown as ball-and-stick representations. C, mononuclear metal center. The zinc ion is shown as a purple sphere. D, electrostatic surface maps of the CopZ-NT and (E and F) a homology model of CopZ-CT. The homology model was generated from the Protein Data Bank file 1OSD by using the CPH models server (34). Red surfaces represent regions of negative charge and blue surfaces are positively charged.

The N-terminal domain of CopZ-NT has a βααβββα fold. The metal ion is coordinated in a tetrahedral arrangement by Cys-4 and Cys-7 on the N-terminal loop before β1 and Cys-38 and Cys-43 on the loop connecting β2 and β3 (Fig. 6B). Of these cysteines, Cys-4, Cys-38, and Cys-43 are conserved among all of the known proteins that have homology to the N terminus. The Thiomicrospira, Deinococcus, and Thermosynechococcus proteins contain Asn, Ser, and Asp residues, respectively, at position 7 instead of a cysteine (Fig. 1B). The average metal-sulfur distance over both molecules in the asymmetric unit is 2.35 Å. Anomalous difference maps calculated using data collected at the iron absorption edge yield a small peak at the position of the metal ion (Table 4). This peak is 6-fold less intense than those used to identify the [2Fe-2S] cluster at this wavelength, suggesting that only a trace amount of iron occupies this position. For data collected at the selenium absorption edge, the metal ion at this position gives rise to a slightly stronger anomalous signal than the iron atoms in [2Fe-2S] cluster. Based on these anomalous differences, the coordination geometry, and the presence of zinc in the purified protein, it is likely that Zn2+ primarily occupies this site and that it assumes a structural role in the protein. It is possible that protein purified directly from A. fulgidus would contain iron at this position, however. If this were the case, the iron coordination environment would be most similar to that found in rubredoxins (48) and would be consistent with a redox function for this domain. Besides the cysteine ligands, Val-14 from β2 and Thr-18 from α2 are the only other conserved residues in this domain and may be important for mediating contacts with the [2Fe-2S] domain.

TABLE 4.

Anomalous peak heights at the iron and selenium absorption edges

| Atom | Iron edge (7177ev) | Selenium edge (13660 eV) |

|---|---|---|

| Molecule 1 | ||

| Fe1 | 26.5 | 10.4 |

| Fe2 | 25.3 | 9.3 |

| Zn/Fe | 3.9 | 13.8 |

| Molecule 2 | ||

| Fe1 | 26.5 | 11.4 |

| Fe2 | 24.1 | 8.7 |

| Zn/Fe | 3.9 | 14.5 |

The [2Fe-2S] domain is all α-helical and differs significantly from typical [2Fe-2S] ferredoxins, which usually have a βαββαβ fold (53). The [2Fe-2S] center is coordinated by Cys-75, Cys-77, Cys-109, and Cys-119, which are found on loops between the α-helices (Fig. 6C) and are highly conserved (Fig. 1B). The average Fe-Fe distance of 2.8 Å is nearly identical to the 2.77 Å Fe-Fe distance determined by XAS for reduced CopZ and is consistent with photoreduction of the metal cluster. The average Fe-S(Cys) and Fe-S2− distances are 2.35 and 2.30 Å, respectively, and the overall geometry of the iron-sulfur cluster is similar to that observed in high resolution crystal structures of [2Fe-2S]-containing proteins (54). The unusual EPR spectrum of CopZ is not readily explained by the structure. All the conserved residues in this domain that do not coordinate the [2Fe-2S] cluster are located nearby. These include Tyr-76, Asn-113, Pro-114, and Cys-118. The side chains of Tyr-76 and Asn-113 point away from the [2Fe-2S] cluster toward a polar 61-Å3 cavity that contains ordered solvent and an acetate molecule derived from the crystallization solution (Fig. 5C). The [2Fe-2S] cluster forms the roof of this cavity. Such cavities are also observed in other [2Fe-2S] proteins such as Trichomonas vaginalis ferredoxin (55). The remaining conserved residue, Cys-118, lies on the protein surface 4 Å from [2Fe-2S] center and hydrogen bonds to a nonconserved histidine, His-120. The C118S mutant, however, binds as much copper as native CopZ, suggesting Cys-118 and His-120 do not constitute the additional copper-binding site.

Functional Implications

CopZ from A. fulgidus is the first known fusion of a redox-active [2Fe-2S]-containing domain to an Atx1-like CXXC-containing domain that delivers Cu+ ions. The combination of these two modular units differentiates CopZ from all other members of the Atx1-like copper chaper-one family. CopZ binds Cu+ and can transfer it to the N-MBD of its putative partner Cu+-ATPase CopA, and likely has the same fold as and a similar function to other Atx1-like proteins. By contrast, CopZ-NT has a novel fold and represents a new class of [2Fe-2S] protein that appears to be found only in extremophilic organisms. This domain is further partitioned into smaller units, each housing a metallo-cofactor. The exact role of CopZ-NT is unknown, but the presence of a [2Fe-2S] center strongly suggests that a redox function is involved.

One possibility is that the [2Fe-2S] cluster reduces Cu2+ to Cu+. The Cu+ might then bind to the CopZ-CT CXXC sequence for subsequent shuttling to the CopA N-MBD or the CopA transmembrane copper-binding site for efflux. In support of this model, CopZ can reduce Cu2+ to Cu+, and CopZ-NT binds one copper ion. It is conceivable that Cu2+ binds transiently to a site near the [2Fe-2S] cluster (Fig. 6C), is reduced, and is then transferred to the CopZ-CT. At present we are trying to identify the location of the Cu+-binding site in the CopZ-NT and assess its possible role in metal transfer to the CopA MBDs.

Electrostatic surface calculations using PyMOL (56) reveal extended positively and negatively charged patches on the face of CopZ-NT containing [2Fe-2S] cluster (Fig. 6D). Homology modeling and electrostatic surface calculations for CopZ-CT (Fig. 6, E and F) suggest that this domain has a negatively charged surface. These complementary surfaces could allow docking with the metal-binding sites in close proximity and subsequent metal transfer between domains.

Several organisms, including A. fulgidus and Enterococcus hirae, express a Cu2+-ATPase, called CopB, that utilizes histidine-rich cytosolic metal binding domains to facilitate Cu2+ removal (8, 57, 58). In E. hirae, CopB is co-transcribed with CopA in response to copper stress (59). As an additional or alternative route for Cu2+ removal, A. fulgidus CopZ could reduce Cu2+ to Cu+, allowing CopB and CopA to function simultaneously. Given that A. fulgidus is an anaerobic, sulfur-metabolizing hyperthermophile (60, 61), it is reasonable that its copper trafficking system differs from those in other organisms. Prior to the advent of an oxidizing atmosphere, copper was not an essential element (62), and the earliest copper ATPases probably only functioned in detoxification. Further characterization of A. fulgidus CopZ and its interactions with CopA may provide new insight into the evolution of copper homeostatic pathways.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. González-Guerrero for the generous help with the Cu+ transfer experiments. Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the United States Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Footnotes

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code2HU9) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. S1.

The abbreviations used are: TM, transmembrane; BCA, bicinchoninic acid; C-MBD, C-terminal CopA metal binding domain; N-MBD, N-terminal CopA metal binding domain; CopZ-CT, CopZ C-terminus; CopZ-NT, CopZ N-terminus; N-MBD, N-terminal CopA metal binding domain; r.m.s.d., root mean square deviation; DTT, dithiothreitol; MOPS, 4-morpholinepropanesulfonicacid.

M. González-Guerrero and J. M. Argüello, unpublished results.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant GM58518 (to A. C. R.), National Science Foundation Grant MCM-0235165 (to J. M. A.), and National Institutes of Health Grants HL13531 (to B. M. H.) and DK068139 (to T. L. S.).

References

- 1.Rosenzweig AC. Acc Chem Res. 2001;34:119–128. doi: 10.1021/ar000012p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huffman DL, O’Halloran TV. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:677–701. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Llanos RM, Mercer JFB. DNA Cell Biol. 2002;21:259–270. doi: 10.1089/104454902753759681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarkar B. Chem Rev. 1999;99:2535–2544. doi: 10.1021/cr980446m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bull PC, Cox DW. Trends Genet. 1994;10:246–252. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(94)90172-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cox DW, Moore SD. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2002;34:333–338. doi: 10.1023/a:1021293818125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsi G, Cox DW. Human Genet. 2004;114:165–172. doi: 10.1007/s00439-003-1045-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Argüello JM. J Membr Biochem. 2003;195:93–108. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Axelsen KB, Palmgren MG. J Mol Evol. 1998;46:84–101. doi: 10.1007/pl00006286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lutsenko S, Kaplan JH. Biochemistry. 1995;34:15607–15613. doi: 10.1021/bi00048a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Achila D, Banci L, Bertini I, Bunce J, Ciofi-Baffoni S, Huffman DL. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5729–5734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504472103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banci L, Bertini I, Ciofi-Baffoni S, Gonnelli L, Su XC. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:50506–50513. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307389200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Banci L, Bertini I, Ciofi-Baffoni S, Huffman DL, O’Halloran TV. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:8415–8426. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008389200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gitschier J, Moffat B, Reilly D, Wood WI, Fairbrother WJ. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:47–54. doi: 10.1038/nsb0198-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arnesano F, Banci L, Bertini I, Huffman DL, O’Halloran TV. Biochemistry. 2001;40:1528–1539. doi: 10.1021/bi0014711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banci L, Bertini I, Conte RD, Markey J, Ruiz-Dueñas FJ. Biochemistry. 2001;40:15660–15668. doi: 10.1021/bi0112715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenzweig AC, Huffman DL, Hou MY, Wernimont AK, Pufahl RA, O’Halloran TV. Structure (Lond) 1999;7:605–617. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(99)80082-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wernimont AK, Huffman DL, Lamb AL, O’Halloran TV, Rosenzweig AC. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:766–771. doi: 10.1038/78999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wimmer R, Herrmann T, Solioz M, Wüthrich K. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:22597–22603. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cobine PA, George GN, Winzor DJ, Harrison MD, Mogahaddas S, Dameron CT. Biochemistry. 2000;39:6857–6863. doi: 10.1021/bi000015+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DiDonato M, Hsu HF, Narindrasorasak S, Que L, Jr, Sarkar B. Biochemistry. 2000;39:1890–1896. doi: 10.1021/bi992222j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Forbes JR, Hsi G, Cox DW. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:12408–12413. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.18.12408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamza I, Schaefer M, Klomp LWJ, Gitlin JD. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:13363–13368. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huffman DL, O’Halloran TV. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:18611–18614. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000172200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walker JM, Tsivkovskii R, Lutsenko S. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:27953–27959. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203845200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wernimont AK, Yatsunyk LA, Rosenzweig AC. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:12269–12276. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311213200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mandal AK, Cheung WD, Argüello JM. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:7201–7208. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109964200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sazinsky MH, Agarwal S, Argüello JM, Rosenzweig AC. Biochemistry. 2006;45:9949–9955. doi: 10.1021/bi0610045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sazinsky MH, Mandal AK, Argüello JM, Rosenzweig AC. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:11161–11166. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510708200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brenner AJ, Harris ED. Anal Biochem. 1995;226:80–84. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stookey LL. Anal Chem. 1970;42:779–781. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beinert H. Anal Biochem. 1983;131:373–378. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90186-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cook JD, Bencze KZ, Jankovic AD, Crater AK, Busch CN, Bradley PB, Stemmler AJ, Spaller MR, Stemmler TL. Biochemistry. 2006;45:7767–7777. doi: 10.1021/bi060424r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lund O, Nielsen M, Lundegaard C, Worning P. CASP5 Conference. University of California; Santa Cruz: 2002. Abstr. 102. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ankudinov AL, Rehr JJ. Phys Rev Lett. 1997;56:R1712–R1715. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lieberman RL, Kondapalli KC, Shrestha DB, Hakemian AS, Smith SM, Telser J, Kuzelka J, Gupta R, Borovik AS, Lippard SJ, Hoffman BM, Rosenzweig AC, Stemmler TL. Inorg Chem. 2006;45:8372–8381. doi: 10.1021/ic060739v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee PA, Citrin PH, Eisenberger P, Kincaid BM. Rev Mod Phys. 1981;53:769–806. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riggs-Gelasco PJ, Stemmler TL, Penner-Hahn JE. Coord Chem Rev. 1995;144:245–286. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Terwilliger TC, Berendzen J. Acta Crystallogr Sect D Biol Crystallogr. 1999;55:849–861. doi: 10.1107/S0907444999000839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brünger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Rice LM, Simonson T, Warren GL. Acta Crystallogr Sect D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cohen SX, Morris RJ, Fernandez FJ, Ben Jelloul M, Kakaris M, Parthasarathy V, Lamzin VS, Kleywegt GJ, Perrakis A. Acta Crystallogr Sect D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2222–2229. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904027556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McRee DE. J Struct Biol. 1999;125:156–165. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1999.4094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laskowski RA. J Appl Crystallogr. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Messerschmidt A, Huber R, Wieghardt K, Poulos T, editors. Handbook of Metalloproteins. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mandal AK, Argüello JM. Biochemistry. 2003;42:11040–11047. doi: 10.1021/bi034806y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yatsunyk LA, Rosenzweig AC. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:8622–8631. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609533200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lippard SJ, Berg JM. Principles of Bioinorganic Chemistry. University Science Books; Mill Valley, CA: 1994. p. 7.p. 358. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Solomon EI, Szilagyi RK, George SD, Basumallick L. Chem Rev. 2004;104:419–458. doi: 10.1021/cr0206317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Westre TE, Kennepohl P, DeWitt JG, Hedman B, Hodgson KO, Solomon EI. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:6297–6314. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Davydov A, Davydov R, Gräslund A, Lipscomb JD, Andersson KK. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:7022–7026. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.11.7022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Holm L, Sander C. J Mol Biol. 1993;233:123–138. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hubbard TJP, Murzin AG, Brenner SE, Chothia C. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:236–239. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.1.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sticht H, Rösch P. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1998;70:95–136. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(98)00027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Crossnoe CR, Germanas JP, LeMagueres P, Mustata G, Krause KL. J Mol Biol. 2002;318:503–518. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Delano WL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 0.99. DeLano Scientific; San Carlos, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bissig KD, Wunderli-Ye H, Duda PW, Solioz M. Biochem J. 2001;357:217–223. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3570217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mana-Capelli S, Mandal AK, Argüello JM. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:40534–40541. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306907200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Solioz M, Stoyanov JV. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2003;27:183–195. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kletzin A, Urich T, Müller F, Bandeiras TM, Gomes CM. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2004;36:77–91. doi: 10.1023/b:jobb.0000019600.36757.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stetter KO. FEBS Lett. 1999;452:22–25. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00663-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kaim W, Rall J. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1996;35:43–60. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.