Abstract

To investigate whether vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) enhances cancer cell adhesion to normal microvessels, we used in vivo video microscopy to measure adhesion rates of MDA-MB-435s human breast cancer cells and ErbB2-transformed mouse mammary carcinomas in the post-capillary venules of rat mesentery. An individual post-capillary venule in the mesentery was injected via a glass micropipette with cancer cells either in a perfusate of 1% BSA mammalian Ringer for control, or 1nM VEGF for test measurements. Cell adhesion was measured as either the number of adherent cells or the fluorescence intensity of adherent cells in a vessel segment for ~60 min. Our results showed that during both control and VEGF treatments, the number of adherent cells increased almost linearly with time over 60 min. VEGF treatment increased the adhesion rates of human tumor cells and mouse carcinomas 1.9-fold and 1.8-fold over those of controls, respectively. We also measured cancer cell adhesion after pretreatment of cells with the antibody blocking VEGF or that blocking α6 integrin, and pretreatment of the microvessel with VEGF receptor (KDR/Flk-1) inhibitor, SU1498, or anti-integrin ECM ligand antibody, anti-laminin-5. All antibodies and inhibitor significantly reduced adhesion, with anti-VEGF and SU1498 reducing it the most. Our results indicate that VEGF enhances cancer cell adhesion to the normal microvessel wall, and further suggest that VEGF and its receptor KDR/Flk-1, as well as integrins of tumor cells and their ligands at the endothelium, contribute to mammary cancer cell adhesion to vascular endothelium in vivo.

Keywords: MDA-MB-435s, ErbB2-transformed mouse mammary carcinoma, rat mesenteric post-capillary venule, single microvessel perfusion

INTRODUCTION

The danger of cancer is organ failure caused by metastatic tumors that are derived from the primary tumor (Steeg and Theodorescu, 2008; Weiss et al., 1988). One critical step in tumor metastasis is adhesion of primary tumor cells to the endothelium forming the microvascular wall in distant organs (Steeg, 2006). Understanding this step may lead to new therapeutic concepts for tumor metastasis targeting tumor cell arrest and adhesion in the microcirculation. In vitro static adhesion assays have been utilized to investigate tumor cell adhesion to endothelial cells (Early and Plopper, 2006; Lee et al., 2003) and to extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins (Spinardi et al., 1995). Tumor cell adhesion has also been investigated using flow chambers (Chotard-Ghodsnia et al., 2007; Giavazzi et al., 1993; Slattery et al., 2005) or artificial blood vessels (Brenner et al., 1995) to address flow effects. Direct injection of tumor cells into the circulation has enabled the observation of tumor cell metastasis in target organs after sacrificing the animals (Schluter et al., 2006), while intravital microscopy has been used to observe the interactions between circulating tumor cells and the microvasculature both in vivo and ex vivo (Al-Mehdi et al., 2000; Haier et al., 2003; Glinskii et al., 2003; Koop et al., 1995; Mook et al., 2003; Steinbauer et al., 2003). Regardless of these attempts, however, to date very little has been learned about the mechanisms governing tumor cell adhesion without loss of their physiological and dynamic microenvironment. This is largely due to the absence of an accurate in vivo model system.

Previous studies have found that breast cancer cells express vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) to a high degree (Brown et al., 1995; Lee et al., 2003), while the microvascular endothelium has abundant VEGF receptors including VEGFR2 ( KDR/Flk-1) (Mukhopadhyay et al., 1998). VEGFR2 has been implicated in normal and pathological vascular endothelial cell biology (Olsson et al., 2006). However, its role in tumor cell adhesion in general and adhesion to normal microvessels in particular has not been examined in a well-control in vivo system. In addition, blood flow can enhance cell adhesion under certain conditions (Zhu et al., 2008). Microvasculature flow conditions, either in specific organs or under different physiological and pathological conditions, may alter tumor cell adhesion. Tzima et al. (2005) reported that the shear stress induced by the blood flow may activate VEGFR2 in a ligand-independent manner by promoting the activation of a mechanosensory complex, which functions upstream of integrin activation. Moreover, integrins, e.g., α6β4, α5β1, α6β1, and their ligands, e.g., laminin-5,-4, -2, -1 of ECM, have been suggested as key players for breast cancer cell adhesion (Spinardi et al., 1995; Giannelli et al., 2002; Guo and Giancotti, 2004; Guo et al., 2006).

Although VEGF has long been recognized as a vascular permeability-enhancing agent for normal endothelium both in vivo and in vitro (Bates, 1997; Bates and Curry 1996; Collins et al., 1993; Fu and Shen, 2004; Wang et al, 2001; Wu et al., 1996), at present, VEGF-induced microvessel hyperpermeability and its role in tumor metastasis remain poorly elucidated (Bates and Harper, 2003; Dvorak, 2002). Lee et al. (2003) used a transwell culture system with a human brain microvascular endothelial cell (HBMEC) monolayer as an in vitro model to investigate the effects of VEGF on adhesion and transendothelial migration of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. They found that VEGF increased MDA-MB-231 adhesion and transmigration through increasing HBMEC monolayer permeability to inulin. Unfortunately, no well-controlled in vivo study of VEGF-mediated effects on tumor adhesion has been reported to date.

Accordingly, the objective of this study is to investigate both in vivo breast cancer cell adhesion to normal microvascular endothelium and the effect of VEGF on adhesion in an individual microvessel under well-controlled permeability and flow conditions. Quantitative microscope photometry was used to quantify microvessel permeability to solutes of differing sizes. Adhesion rates of human malignant breast cancer cell MDA-MB-435s and ErbB2-transformed mouse mammary carcinoma in a single post-capillary venule of rat mesentery in vivo were measured by intravital video microscopy. Our method includes at least two advantages over previous studies in this area. First, we investigate breast tumor cell adhesion in intact microvessels, rather than in a traditional cultured cell monolayer model, which lacks a true physiological microenvironment. Second, our work is performed on an individually perfused microvessel, in which experimental conditions can be well defined. This approach overcomes the uncertainties associated with whole animal studies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal Preparation

All in vivo experiments reported in this paper were performed on female Sprague-Dawley rats (250-300g, age 3-4 months), supplied by Simonson Laboratory (Gilroy, CA) and Hilltop Laboratory Animals (Scottdale, PA). All procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committees at both the University of Nevada Las Vegas and at the City College of the City University of New York. The methods used to prepare rat mesenteries, perfusate solutions, and micropipettes for microperfusion experiments have been described in detail elsewhere (Fu and Shen, 2004). A brief outline of the methods is given below with emphasis on the special features of the current experiments. At the end of experiments the animals were euthanized with excess anesthetic. The thorax is opened to ensure death.

Rats were first anaesthetized with pentobarbital sodium given subcutaneously. The initial dosage was 65mg/kg and additional 3mg/dose was given as needed. After a rat was anesthetized, a midline surgical incision (2-3 cm) was made in the abdominal wall. The rat was then transferred to a tray and kept warm on a heating pad. The mesentery was gently taken out from the abdominal cavity and spread on a glass coverslip, which formed the base of the observation platform as previously described (Fu et al., 2005). The gut was gently pinned out against a silicon elastomer barrier to maintain the spread of the mesentery. The upper surface of the mesentery was continuously superfused by a dripper with mammalian Ringer solution at 35-37°C, which was regulated by a controlled water bath and monitored regularly by a thermometer probe. The microvessels chosen for the study were straight non-branched postcapillary venules, with diameters of 40-50 μm. All vessels had brisk blood flow immediately before cannulation and had no marginating white cells.

Cell Culture

Human breast ductal carcinoma (MDA-MB-435s) cells were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and cultured in 75 cm2 plastic tissue culture flasks (Corning, NY) in Leibovitz's L-15 medium with 2 mM L-glutamine (ATCC), supplemented 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and 100 U/ml penicillin (Sigma). Cultures were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% carbon dioxide and subcultured every third day. Cells were cultured at 106 cells/ml and grown to confluence (90%), and routinely passaged using trypsin/EDTA (ATCC) at ratio 1:4 (Early and Plopper, 2006).

ErbB2-transformed mouse mammary carcinoma (WT) cells were cultured in Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (Guo et al, 2006). Briefly, WT cells were grown in 75 cm2 tissue culture flasks (Corning, NY) with DMEM containing F12, non essential amino acids, 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), hydrocortisone (1 μg/ml), choleratoxin (10-9 M), and insulin (10 μg/ml) in a humidified 95% air/5% CO2 environment at 37 °C. On the day of experiments, cells were collected by brief trypsinization, then counted and suspended in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, Sigma). To remove any remaining cell clumps, the cell suspension was filtered through a 70-μm and 40-μm nylon mesh, and adjusted to contain ~4 million cells/ml for the final perfusate.

The cell survival rate was >95% before perfusion, and >90% after ~1.5hr perfusion at driving pressures of 2-15 cmH2O in perfusing micropipettes.

Fluorescently Tagging of MDA-MB-435s Cells

When the cells reached confluence, media was removed. Cells were washed in PBS and incubated with CellTracker Green (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) at 0.5 μM for 40 min. After staining, the probe solution was replaced with fresh, pre-warmed medium. The cells were then incubated for another 30 min at 37°C and collected by brief trypsinization, blocked with medium, and washed extensively twice with PBS. The immediate toxicity of this procedure was minimal, leaving 95-100% of the cells alive as determined by trypan blue (Sigma) exclusion. Finally the cells were stored in 1% BSA (bovine serum albumin, Sigma) mammalian Ringer solution at 5-10 × 106 cells/ml, kept in darkness at room temperature, and were ready for immediate use.

Solutions and Reagents

Mammalian Ringer solution

Mammalian Ringer solution was used for all dissections, perfusates and superfusate (Fu and Shen, 2004). The solution composition was (in mM) 132 NaCl, 4.6 KCl, 1.2 MgSO4, 2.0 CaCl2, 5.0 NaHCO3, 5.5 glucose, and 20 HEPES. Its pH was balanced to 7.4 by adjusting the ratio of HEPES acid to base. In addition, the perfusate into the microvessel lumen contained BSA at 10 mg/ml (1% BSA-Ringer solution). VEGF (human recombinant VEGF165, Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ) of 1nM was made in mammalian Ringer solution containing 1% BSA. Anti-α6 and anti-laminin-5 antibodies and a control antibody W632 were obtained from Sanquin Reagents (Amsterdam, Netherlands), Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) and Sigma, respectively. Anti-Human VEGF monoclonal antibody was purchased from Leinco Technologies, Inc. (St. Luis, Missouri) and the inhibitor to VEGFR2 (KDR/Flk-1), SU-1498, from alomone labs, Ltd. (Jerusalem, Israel). The concentration of antibodies was 20μg/ml and SU-1498 concentration was 50 μM in 1% BSA-Ringer solution. All of the solutions described above were made at the time when experiment started and were discarded at the end of the day.

Sodium fluorescein

Sodium fluorescein (F6377, Sigma; mol. wt. 376) was dissolved at 0.1 mg/ml in the Ringer solution containing 10 mg/ml BSA.

FITC-labeled α-lactalbumin and BSA

α-lactalbumin (L6010, Sigma; mol wt 14,176) and BSA (A4378, Sigma; mol wt approx. 67,000) were labeled with FITC (F7250, Sigma, mol wt 389.4) as detailed in (Adamson et al., 1988). The FITC-labeled α-lactalbumin and BSA were stored frozen and used within 2 weeks of preparation. On the day of use, unlabeled BSA was added to aliquots of the labeled protein. The final FITC-α-lactalbumin and FITC-BSA concentrations used in the experiment were 1 mg/ml in the Ringer solution (Fu and Shen, 2004).

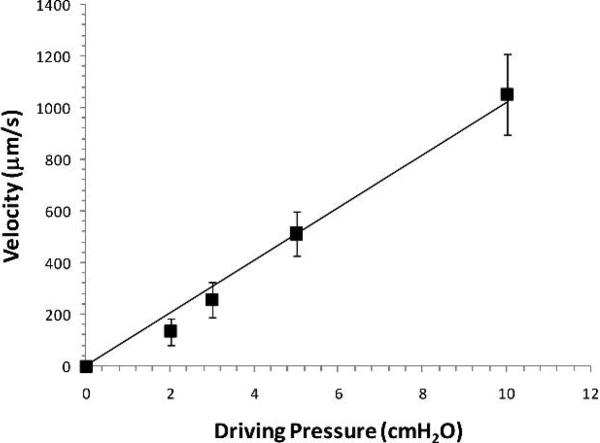

Perfusion of a Single Mesenteric Microvessel

A single venular microvessel (40-50 μm diameter) was cannulated with a glass micropipette (~30μm tip diameter, World Precision Instrument Inc., Florida) and perfused with the rat Ringer solution with either MDA-MB-435s or ErbB2-transformed mouse mammary carcinoma (WT) cells. An initial pressure of 10-20 cmH2O depending on the downstream resistance controlled by a water manometer was applied through the pipette to the microvessel lumen. The initial pressure was set to balance the downstream blood pressure. Then the pressure was increased to a perfusion pressure at 12-30 cmH2O. The difference between the initial pressure and the perfusion pressure was denoted as the driving pressure. The perfusion flow velocity was determined by the driving pressure and was calculated from the movement of a marker tumor cell. The relationship between driving pressure and perfusion velocity is demonstrated in Fig. 1 for 3 vessels. We tested two perfusion velocities in our study, a reduced velocity of ~150 μm/s when the driving pressure was controlled at ~2 cmH2O, and ~1000μm/s, a mean blood flow velocity in this type of microvessels when the driving pressure was ~10 cmH2O.

Fig. 1.

Perfusion flow velocity as a function of the driving pressure. The perfusion flow velocity was determined by tracking the movement of a fluorescently-labeled tumor cell when the vessel was cannulated and perfused at a known driving pressure measured from a water manometer. The tumor cell movement was recorded using our imaging system at pressures 2, 3, 5 and 10 cmH2O for each vessel. Three vessels were tested and values shown are mean ± SD.

Cell Adhesion and Solute Permeability Measurement

Tumor cell adhesion to microvessel wall

A Nikon Eclipse TE-300 inverted fluorescence microscope with 20× lens (NA=0.75) was used to observe the mesentery. A filter set from Omega Optical (Brattleboro, VT), consisting of an excitation filter (510DF23), a dichroic mirror (525DRLP), and an emission filter (535DF35) was used to observe CellTracker Green fluorescence. To minimize tissue damage and quench, the intensity of the microscope Xenon light source was kept as low as possible. Further protection was provided by using an experimental protocol in which the time of tissue exposure to the excitation light was kept as short as possible for the intensity measurement. Generally, the exposure time for an individual image recording was 0.2-1.0s. Cell adhesion to the microvessel wall was observed at every minute by a low light level CCD Camera (COHU) and the images were recorded into a computer through an A/D board by an InCyt Im1™ imaging system (Intracellular Imaging Inc.). Our imaging and recording setting induced negligible image quench in ~1.5 hr (less than 1%). Cell adhesion was represented by the total cells (the fluorescence intensity of total cells) in a vessel segment (60-80 μm wide × 300-400 μm long).

For WT cells not labeled with fluorescence, the mesentery tissue was observed by a 20X objective lens (NA 0.75, super, Nikon) under a bright field. The adhesion process was imaged by a high performance digital 12 bit CCD camera (SensiCam QE, Cooke Corp., Romulus, MI) using InCyt Im 1 software. Adherent cells were counted offline in a vessel segment of 300-400 μm length and expressed as the number of adherent cells per 5000 μm2 plane area (length × diameter) of the vessel segment. The measuring area was set at least 150μm downstream from the cannulation site of the vessel to avoid entrance flow effects.

Apparent solute permeability (P) of a microvessel

A detailed method used to measure P of fluorescently labeled solutes is described in (Fu and Shen, 2004). The same microscope described above with 10× lens (NA 0.3, Nikon) was used to measure P. The filter set from Omega optical, which was used for sodium fluorescein, FITC-BSA and FITC-α-lactalbumin, consisted of an excitation filter (485DF22), a dichroic mirror (505DRLP), and an emission filter (535DF35). Fluorescence intensity (If) in the capillary lumen and surrounding tissue was measured by aligning the vessel segment within an adjustable measuring window consisting of a rectangular diaphragm in the light path. The dimensions of this measurement window were generally ~200 μm width (roughly 5 times the microvessel diameter) and 300-400 μm length. The window was set at least 100 μm from the cannulation site of the vessel to avoid solute contamination from that site. If measured by a photometer (HC135-11, Hamamatsu), was recorded into a computer using InCyt Pm1™ Photometry software (Intracellular Imaging Inc.). Compared to the previous strip chart recorder, this type of recording greatly improved the spatial and temporal resolution of the intensity vs. time curve, which was used to calculate solute permeability P. , where ΔIf0 is the step increase in fluorescent light intensity as the test solute fills the microvessel lumen, is the initial rate of increase in fluorescence intensity after solute fills the lumen and begins to accumulate in the tissue, and r is the microvessel radius (Adamson et al., 1988).

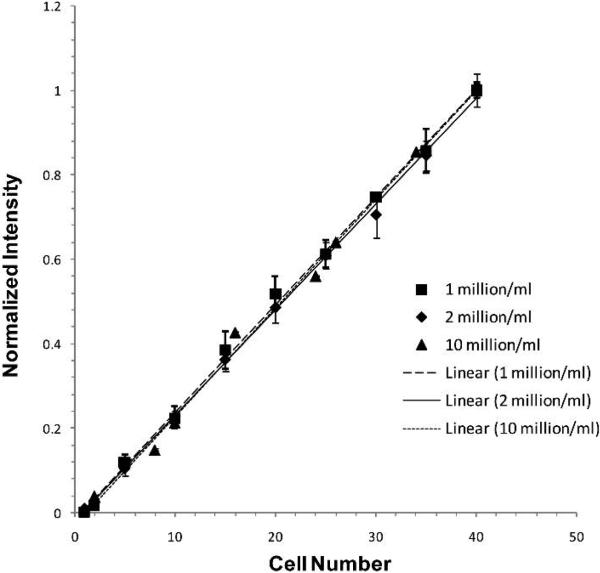

Calibration Experiments

In determining adhesion, in vitro calibration experiments were used to test the assumption that the fluorescence intensity of the fluorescently-labeled cells is a linear function of the number of cells. Figure 2 shows our results for 3 concentrations, 1, 2, and 10 million cells/ml. These intensity vs. cell number curves are linear for all the tested concentrations, although they have different slopes because the optimized settings for imaging were different for different concentrations. However, when normalized by the intensity for a group of cells with the highest cell number (40 cells in our test) at each concentration, the curves of the intensity vs. cell number for different concentrations almost overlap with each other (Fig.2).

Fig. 2.

In vitro calibration for the fluorescence intensity as a function of the number of tumor cells. Each symbol represents one concentration of fluorescently-labeled tumor cells. Three concentrations prepared at different days were examined. Three regions with the same number of cells were chosen for each concentration. Values shown are mean ± SD.

Experimental Protocol

Cell adhesion

To measure the cell adhesion rate under normal permeability conditions, a single straight post-capillary venule was cannulated with a micropipette filled with 1% BSA Ringer solution containing ~5 million cells/ml. The venule was perfused with a driving pressure of 10 cmH2O to maintain a normal flow velocity of ~1000 μm/s, or by a driving pressure of 2 cmH2O to maintain a reduced flow velocity of ~150 μm/s. The adhesion process was recorded at ~ 2 frames/s in a ~1 min interval for ~60 min in each experiment. A single experiment was carried out in one microvessel per animal.

To test the effect of VEGF on cell adhesion to the microvessel wall, the perfusate also contained 1nM VEGF, which has been shown to significantly increase microvessel permeability to both water and solutes (Bates and Curry, 1996, Fu and Shen, 2004, also current study). Cells were injected simultaneously with 1 nM VEGF in 1% BSA Ringer into a single vessel in the same way as in the control and at the same perfusion velocity.

P measurement

To test the effect of 1 nM VEGF on permeability of solutes of different sizes, for each test solute, after making several control measurements with a θ pipette when the washout lumen was filled with Ringer perfusate containing BSA (10 mg/ml) and the dye lumen was filled with the same perfusate, to which the test solute was added, we replaced the pipette with a new θ pipette of both washout and dye solutions also containing VEGF (1 nM). After 10-15 sec perfusion with washout containing VEGF, pressure at the dye side was increased to a higher value while pressure at the washout side was decreased to a lower value for dye perfusion. The perfusion of dye solution containing 1 nM VEGF lasted 5-15 sec, depending on solute size. From the initial step increase in fluorescence intensity of the test dye solution and its accumulation in the measurement window, we can calculate the solute permeability. P was measured every 15-30 sec including both dye (5-15 sec) and washout perfusion (10-15 sec). The alternating perfusion of dye and washout solutions lasted ~ 5 min.

Analysis and Statistics

P measurements during the control period in a vessel were averaged to establish a single value for the control P. This value was then used as a reference for all subsequent measurements on that vessel. Because of the difference in the cell concentration, fluorescence labeling and vessel size for different experiments, in the cell adhesion measurement we defined a base intensity I0 for each vessel, which was an averaged value of 3 measurements in the first 5 min of cell perfusion. The time course of cell adhesion I(t) was normalized as . To present adhesion data at a specific time after 5 min, individual measurements were grouped with 5 min intervals at 10 min (6-10 min), 15 min (11-15 min), etc. Both results for permeability and cell adhesion are presented in mean ± SE unless specified otherwise.

Statistical significance of the treatment over time was tested with a nonparametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test applied to the averaged adhesion data. Mann-Whitney's U test was applied to between-group data to test for adhesion differences at specific times. Significance was assumed for probability levels p < 5%.

RESULTS

Effect of VEGF on MDA-MB-435s Cell Adhesion to the Microvessel Wall

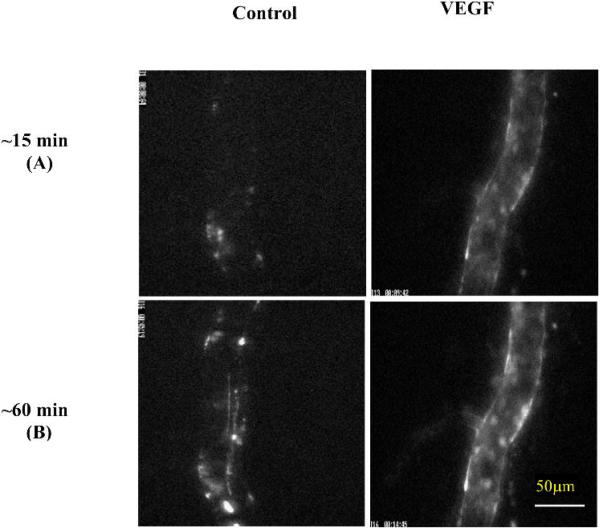

Adhesions of MDA-MB-435s cells in representative microvessels are shown in Figure 3, at ~15 min (Fig. 3A) and ~60 min (Fig. 3B) at a reduced perfusion velocity of ~150 μm/s under either control conditions (1% BSA Ringer) or treatment with 1 nM VEGF. Bright spots in these images represent adherent fluorescently-labeled tumor cells.

Fig.3.

Photomicrographs showing in vivo MDA-MB-435s tumor cell adhesion to a single perfused microvessel under control with 1%BSA Ringer perfusate and under treatment with 1 nM VEGF perfusate after (A) ~15 min and (B) ~60 min perfusion at a driving pressure ~2 cm H2O. Bright spots indicate adherent tumor cells labeled with fluorescence.

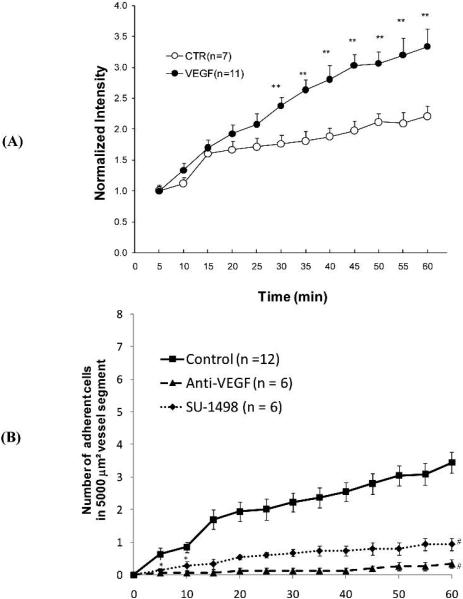

Figure 4A presents the time course of the number of adherent cells as indicated by fluorescence intensity in a vessel segment, under control (1%BSA) and 1 nM VEGF treatment, with normal perfusion velocity (1000 μm/s). Under normal flow and vessel permeability conditions, there was a montonic, statistically significant increase of cell adhesion from its base value starting at 15 min (p < 0.003 after 20 min perfusion). In contrast, VEGF treatment produced a rise in cell adhesion starting earlier, at 10 min (p < 0.001 after only 15 min perfusion). Linear regression of data for intensity (cell adhesion amount) vs. time revealed that cell adhesion increased almost linearly with time, with R2 = 0.97 and 0.88 for control and VEGF treatment, respectively. The cell adhesion rate (the slope of the intensity vs. time curve) under VEGF treatment was 1.9-fold that of control.

Fig. 4.

MDA-MB-435s cell adhesion as a function of time: (A) under control with 1%BSA Ringer perfusate (empty circles) and under treatment with 1 nM VEGF perfusate (filled circles); (B) under control with 1%BSA Ringer perfusate (squares), pretreatment of the cells with anti-VEGF antibody (triangles) and pretreatment of the vessel with VEGF receptor (KDR/Flk-1) inhibitor, SU-1498 (diamonds). For both (A) and (B), the perfusion velocity is ~1000μm/s, which is the normal flow velocity in post-capillary venules. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01, # p < 0.001, compared to the controls.

Breast cancer cells express VEGF strongly (Brown et al., 1995; Lee et al., 2003), while mesentery microvascular endothelium expresses abundant VEGF receptor Flk-1 (Mukhopadhyay et al., 1998). To test if the interaction between VEGF and its receptor Flk-1 plays a role in breast cancer cell adhesion, we pretreated the cells with anti-VEGF for 60 min at 4°C before perfusing the microvessel, or pretreated the microvessel with a VEGF receptor (Flk-1) inhibitor, SU-1498, for 45 min before perfusing the cells. Figure 4B shows our results. Anti-VEGF (triangles) and SU-1498 (diamonds) almost completely abolished cancer cell adhesion to the vessel wall under normal permeability conditions starting from 5 min (adhesion during 0-5 min) (p <0.05).

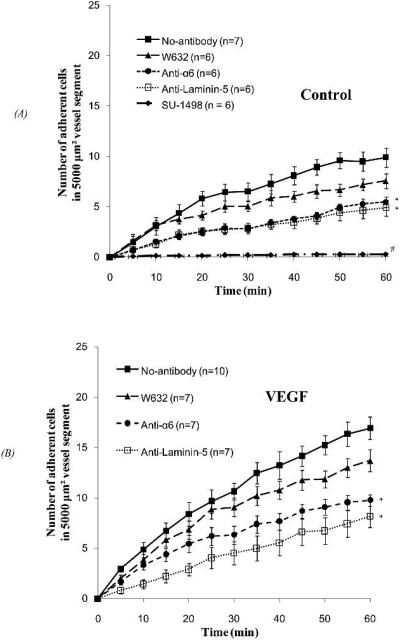

Effect of VEGF on WT Cell Adhesion to the Microvessel Wall

Figure 5 shows the adhesion of ErbB2-transformed mouse mammary carcinoma cells. Figure 5A shows cell adhesion under normal permeability, while Fig. 5B shows adhesion under VEGF treatment. Compared to control conditions, 1 nM VEGF significantly increased WT cell adhesion starting from 5 min (adhesion during 0-5 min, p < 0.05). As with MDA-MB-435s adhesion, WT cell adhesion increased almost linearly with time, with R2 = 0.94 and 0.97 for control and VEGF treatment, respectively. The cell adhesion rate (the slope of the number of adherent cells vs. time curve) under VEGF treatment was 1.8-fold that of control.

Fig.5.

ErbB2-transformed mouse mammary carcinoma cell adhesion as a function of time: (A) under control with 1%BSA Ringer perfusate and (B) under 1 nM VEGF treatment, after pretreating cells with no antibody (filled squares), an irrelevant control antibody W632 (triangles), anti-α6 (circles), or pretreating the vessels with anti-laminin 5 (empty squares) and an VEGF receptor inhibitor, SU-1498 (diamonds). For both (A) and (B), the perfusion velocity is ~1000μm/s, which is the normal flow velocity in post-capillary venules. * p < 0.05, # p < 0.001, compared to no-antibody.

As was also the case for MDA-MB-435s, pretreatment of the microvessel with SU-1489 completely abolished WT cell adhesion under normal permeability (diamonds in Fig. 5A, p < 0.001 starting in 5 min).

Integrins such as α6β4 and α6β1, and their ligands in the ECM, laminin-5, -4, -2 and -1, have been suggested as key players for breast cancer cell adhesion (Spinardi et al., 1995; Giannelli et al., 2002; Guo and Giancotti, 2004; Guo et al., 2006). We therefore examined the integrin effect on cell adhesion in our in vivo single vessel perfusion model. Under normal permeability and VEGF treatment, a control antibody, W632 (triangles in Figs. 5A, B), insignificantly decreased the WT cell adhesion (p > 0.05). However, anti-α6 (circles in Figs. 5A,B) and anti-laminin-5 (empty squares in Figs. 5A, B) significantly decreased the WT cell adhesion by 40-50% under both conditions (p < 0.05).

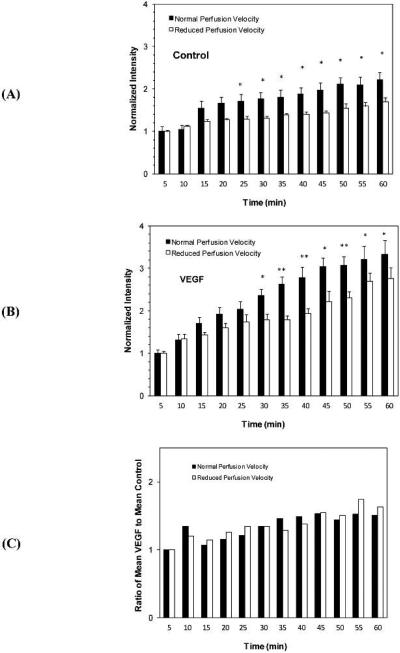

Effect of Flow on MDA-MB-435s Cell Adhesion to the Microvessel Wall

The effect of flow on tumor cell adhesion in a single microvessel is shown in Figure 6. Under control conditions, Fig. 6A demonstrates that after 25 min, normal perfusion induced a 30-37% higher adhesion than that induced by a reduced perfusion (p < 0.05). Similarly, Fig. 6B shows that under VEGF treatment, perfusion at a velocity of ~1000 μm/s induced a 20-47% higher adhesion than that induced by a perfusion velocity of ~150 μm/s after 30 min (p < 0.05). Figure 6C shows the ratio of mean adhesion amount under VEGF to that under control. Treatment with VEGF increased adhesion beyond that observed under control conditions (ratio > 1), but that increase was independent of flow rate. There was no significant difference between the normal and reduced flows at any time (p > 0.75).

Fig.6.

Comparison of perfusion velocity effects on MDA-MB-435s cell adhesions at different times under (A) control with 1% BSA perfusate, and (B) treatment with 1 nM VEGF perfusate. (C) Comparison of VEGF effect on MDA-MB-435s cell adhesion at different times under normal and reduced perfusion velocities. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

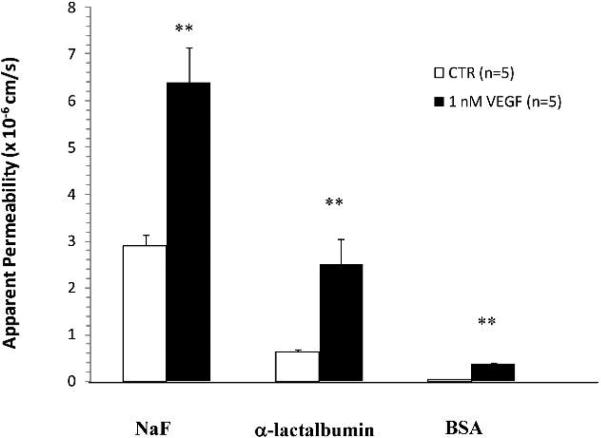

Effect of VEGF on Apparent Solute Permeability P of Rat Mesenteric Microvessels

As in our previous studies (Fu and Shen, 2004), paired measurements of P in individual rat mesenteric microvessels (Fig. 7) indicate that P for three solutes of different sizes had a transient increase under treatment with VEGF, peaked at ~30 sec and returned to baseline values in ~ 2 min. Psodium fluorescein (Mean ± SE) in 5 vessels, measured at the peak of the response to VEGF (25 ± 5 s), was 6.4 ± 0.74 × 10-5 cm/s, compared with a baseline P of 2.9 ± 0.24 × 10-5 cm/s. This represents a mean peak increase in Psodium fluorescein of 2.2 ± 0.13-fold compared with the baseline in the same vessel (p < 0.01). Pα-lactalbumin, again measured at the peak of the response to VEGF (26 ± 2 s), was 2.5 ± 0.54 × 10-5 cm/s, compared with a baseline P of 0.63 ± 0.051 × 10-5 cm/s. This represents a mean peak increase in Pα-lactalbumin of 3.9 ± 0.6-fold compared with the baseline in the same vessel (p < 0.01). PBSA measured at the peak of the response to VEGF (28 ± 4 s) was 0.37 ± 0.02 × 10-5 cm/s, compared with a baseline P of 0.052 ± 0.004 × 10-5 cm/s. This represents a mean peak increase in PBSA of 7.1 ± 0.8-fold compared with the baseline in the same vessel (p < 0.01).

Fig. 7.

Paired measurements of apparent solute permeability (P) in individual rat mesenteric microvessels under the control condition when P was first measured with Ringer perfusate containing 1% BSA, then P was measured in the same vessel when reperfusion with the same solution also containing 1 nM VEGF for ~5 min. The figure shows the comparison between the control (CTR) and peak values (VEGF) under the treatment of VEGF. The peak was at ~30 sec after VEGF reperfusion. Measurements are for three solutes, sodium fluorescein (NaF), α-lactalbumin and BSA. n = 5 for each solute. ** p < 0.01 compared with the control.

DISCUSSION

VEGF has been shown to produce a biphasic increase in the permeability of normal microvessel walls, with an initial transient increase lasting no more than a few minutes (Bates and Curry, 1996; Fu et al., 2003; Fu and Shen, 2004), followed by a chronic sustained increase 24 hours after stimulation (Bates, 1997). In the present experiment (Fig. 5), VEGF significantly increased the WT cell adhesion within 5 min of its onset, which is consistent with these findings. Only about 40% of WT cell adhesion (also MDA-MB-435s adhesion, Fig. 4B) occurred within 1 min under control conditions with normal permeability. In contrast, under VEGF treatment, more than 70% of WT cell adhesion occurred within 1 min. This acute VEGF-induced microvessel hyperpermeability is most likely in part due to an increase in the gap between endothelial cells forming the vessel wall (Michel and Neal, 1999; Fu et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2003; Seegar et., 1993), as well as because of partial degradation of endothelial surface glycocalyx (Fu et al., 2003). Vessel permeability to water has been reported to rise several-fold (Bates and Curry, 1996; Michel and Neal, 1999), which would be expected to bring circulating tumor cells into closer proximity to the vessel wall and therefore increase the opportunity for adhesion. In addition, increased gap space would allow more ECM proteins (e.g., laminin-5, -4, -2, -1) to bind to tumor cell integrins (e.g. α6β4, α6β1, α5β1, Guo and Giancotti, 2004). The combination of these effects might explain the observation of initial enhanced adhesion of tumor cells to the vessel wall in the presence of VEGF.

Since the initial VEGF-induced permeability increase lasts only a few minutes, later adhesion may be due to other factors acting at tumor cells and the endothelium. Because over-expressed VEGF resident on breast cancer cell surfaces would bind to its receptor, VEGFR2 (KDR/Flk-1) at the luminal surface of the microvessel wall, both MDA-MB-435s and WT cells would be expected to adhere to the microvessel wall even under control conditions with normal permeability. This adhesion can be abolished by pretreatment with anti-VEGF or with an antagonist of VEGFR2 (KDR/Flk-1), and can also be reduced by pretreatment with anti-α6 or anti-laminin-5 antibodies. Therefore, later adhesion might be due to VEGF-induced VEGF receptor signaling and activation of integrins (Tzima et al., 2005; Olsson et al., 2006; Weis and Cheresh, 2005), an effect that remains to be investigated. Alternatively, Bates and Curry (1997) found that VEGF increases microvessel permeability by increasing intracellular calcium concentration, which may activate endothelial CLCA2 (calcium activated chloride channel) proteins. The CLCA2 might bind to α6β4 of the breast cancer cells (Abdel-Ghany et al., 2003) and enhance cancer cell adhesion at longer time. However, these hypothetical processes need to be examined in the future study.

Physical effects can also play a role in permeability and adhesion changes. Wall shear stress has been reported to increase microvessel permeability (Michel and Curry, 1999), as well as activating VEGFR2 in a ligand-independent manner (Tzima et al., 2005). Kajimura et al. (1998) used a microperfusion technique to vary the flow rate in frog mesenteric microvessels and demonstrated that permeability to potassium ions increased as velocity increased. In a very different preparation, Turner and Pallone (1997) reported that the permeability of isolated perfused descending vasa recta to small hydrophilic solutes increases with increasing perfusion rate. In addition to increasing microvessel permeability, flow-induced hydrodynamic factors can also enhance tumor cell adhesion. Basson et al. (2000) found in an in vitro system that increasing pressure stimulated malignant human colon cancer adhesion to matrix proteins by a cation-dependent, β1 integrin-mediated mechanism. Thamilselvan et al. (2004) demonstrated that non-laminar flow-induced shear stress increased colon cancer cell adhesion to extracellular proteins by a mechanism requiring both actin cytoskeletal reorganization and force-activation of Src kinase. Tzima et al. (2005) found that blood flow-induced shear stress can trigger a mechanosensory complex that involves VEGFR2, platelet-endothelial-cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1) and vascular endothelial (VE)-cadherins. This mechanism would be expected to induce integrin activation. Our results show that increasing perfusion velocity and perfusion pressure did increase tumor cell adhesion under both control and VEGF treatment. However, the increase due to hydrodynamic factors was only about 35% when the perfusion velocity increased by ~6.7-fold and the driving pressure by ~5-fold. We hypothesize that a greater rise in adhesion was not observed because of the inherently low magnitude of shear stress in our preparation. Shear stress in our perfused microvessel is only ~2.6 dyn/cm2 for a perfusion velocity of ~1000μm/s and ~0.39 dyn/cm2 for a lower velocity of ~150 μm/s. Cell adhesion under a perfusion velocity of ~1000μm/s was almost completely abolished by an inhibitor of VEGFR2 (Fig. 4B, 5A).

Leukocyte rolling at physiological flow rates has been demonstrated to be a prerequisite for stable adhesion to the endothelium (Dong and Lei, 2000; Butcher, 1991). A real-time ex vivo experiment in excised dura mater (Glinskii et al., 2003) showed that prostate carcinoma cells exhibited rolling-like movement prior to engaging into stable adhesive interaction, while other neoplastic cells became stably adhered without rolling. In a flow chamber set up, Giavazzi et al. (1993) observed that HT-29M colon carcinoma, the OVCAR-3 ovarian carcinoma, and the T-47D breast carcinoma cells rolled on IL-1-activated human umbilical vein endothelial cells, but no rolling was observed for the A375M and A2058 melanomas and the MG-63 osteosarcoma, even at a very high shear stress. In vivo observation of tumor cell adhesion in hepatic microcirculation showed that rolling of colon carcinoma cells was very rare. Cells almost adhered abruptly without reducing their velocity prior to adhesion (Haier et al., 2003). A similar effect was observed in the present single vessel perfusion experiment. We observed no rolling adhesion behavior for either MDA-MB-435s or WT cells. Unlike leukocyte extravasation after firm adhesion to the microvessel wall, in our 60 min in vivo single vessel experiments there was no tumor cell extravasation from the microvessel after adhesion.

In summary, our well-controlled, in vivo, single vessel perfusion study showed that VEGF increased microvessel permeability and enhanced both human and mouse breast cancer cell adhesion in the post-capillary venule of a rat mesentery. Anti-VEGF and an inhibitor of VEGFR2 almost completely abolished this adhesion. Anti-integrin α6 and anti-laminin-5 also reduced the WT cell adhesion under both normal and increased permeability conditions. Our findings implicate a new target in anti-metastatic therapy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Dr. George Plopper (was at UNLV, now at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute) and his lab members for teaching the cancer cell culture technique. This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (National Cancer Institute) R15CA86847, P20CA118861-0 and 011U54CA137788-01, the National Science Foundation CAREER Award CBET-0133775 and CBET-0754158.

REFERENCES

- Adamson RH, Huxley VH, Curry FE. Single capillary permeability to proteins having similar size but different charge. Am. J. Physiol. 1988;254:H304–H312. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1988.254.2.H304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Ghany M, Cheng HC, Elble RC, Lin H, DiBiasio J, Pauli BU. The interacting binding domains of the beta(4) integrin and calcium-activated chloride channels (CLCAs) in metastasis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:49406–16. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309086200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mehdi AB, Tozawa K, Fisher AB, Shientag L, Lee A, Muschel RJ. Intravascular origin of metastasis from the proliferation of endothelium-attached tumor cells: a new model for metastasis. Nat Med. 2000;6:100–2. doi: 10.1038/71429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basson MD, Yu CF, Herden-Kirchoff O, Ellermeier M, Sanders MA, Merrell RC, Sumpio BE. Effects of increased ambient pressure on colon cancer cell adhesion. J Cell Biochem. 2000;78(1):47–61. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(20000701)78:1<47::aid-jcb5>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates DO. The chronic effect of vascular endothelial growth factor on individually perfused frog mesenteric microvessels. J. Physiol. 1997;513(Pt 1):225–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.225by.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates DO, Curry FE. Vascular endothelial growth factor increases hydraulic conductivity of isolated perfused microvessels. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;271(40):H2520–2528. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.6.H2520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates DO, Harper S. Regulation of Microvascular permeability by vascular endothelial growth factors. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2003;39:225–237. doi: 10.1016/s1537-1891(03)00011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner W, Langer P, Oesch F, Edgell CJ, Wieser RJ. Tumor cell--endothelium adhesion in an artificial venule. Anal Biochem. 1995;225:213–9. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LF, Berse B, Jackman RW, Tognazzi K, Guidi AJ, Dvorak HF, Senger DR, Connolly JL, Schnitt SJ. Expression of vascular permeability factor (vascular endothelial growth factor) and its receptors in breast cancer. Hum Pathol. 1995;26(1):86–91. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(95)90119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher EC. Leukocyte-endothelial cell recognition: three (or more) steps to specificity and diversity. Cell. 1991;67:1033–6. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90279-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chotard-Ghodsnia R, Haddad O, Leyrat A, Drochon A, Verdier C, Duperray A. Morphological analysis of tumor cell/endothelial cell interactions under shear flow. J Biomech. 2007;40:335–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins PD, Connolly DT, Williams TJ. Characterization of the increase in vascular permeability induced by vascular permeability factor in vivo. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993;109:195–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13553.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak HF. Vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor: a critical cytokine in tumor angiogenesis and a potential target for diagnosis and therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002;20:4368–4380. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.10.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong C, Lei XX. Biomechanics of cell rolling: Shear flow, cell-surface adhesion, and cell deformability. Journal of Biomechanics. 2000;33:35–43. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(99)00174-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earley S, Plopper GE. Disruption of focal adhesion kinase slows transendothelial migration of AU-565 breast cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;350:405–412. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu BM, Adamson RH, Curry FE. Determination of microvessel permeability and tissue diffusion coefficient by laser scanning confocal microscopy. ASME J. Biomech. Eng. 2005;27(2):270–278. doi: 10.1115/1.1865186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu BM, Shen S. Acute VEGF effect on solution permeability of mammalian microvessels in vivo. Microvascular Research. 2004;68:51–62. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu BM, Shen S. Structural mechanisms of acute VEGF effect on microvessel permeability. Am. J. Physiol. 2003;284:H2124–2135. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00894.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannelli G, Astigiano S, Antonaci S, Morini M, Barbieri O, Noonan DM, Albini A. Role of the alpha3beta1 and alpha6beta4 integrins in tumor invasion. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2002;19:217–23. doi: 10.1023/a:1015579204607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giavazzi R, Foppolo M, Dossi R, Remuzzi A. Rolling and adhesion of human tumor cells on vascular endothelium under physiological flow conditions. J. Clin. Invest. 1993;92:3038–44. doi: 10.1172/JCI116928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glinskii OV, Huxley VH, Turk JR, Deutscher SL, Quinn TP, Pienta KJ, Glinsky VV. Continuous real time ex vivo epifluorescent video microscopy for the study of metastatic cancer cell interactions with microvascular endothelium. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2003;20:451–8. doi: 10.1023/a:1025449031136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo WJ, Giancotti FG. Integrin signaling during tumor progression. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:816–26. doi: 10.1038/nrm1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Pylayeva Y, Pepe A, Yoshioka T, Muller WJ, Inghirami G, Giancotti FG. Beta 4 integrin amplifies ErbB2 signaling to promote mammary tumorigenesis. Cell. 2006;126:489–502. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haier J, Korb T, Hotz B, Spiegel HU, Senninger N. An intravital model to monitor steps of metastatic tumor cell adhesion within the hepatic microcirculation. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:507–14. doi: 10.1016/S1091-255X(03)00023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajimura M, Head SD, Michel CC. The effects of flow on the transport of potassium ions through the walls of single perfused frog mesenteric capillaries. J. Physiol. 1998;511:707–718. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.707bg.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koop S, MacDonald IC, Luzzi K, Schmidt EE, Morris VL, Grattan M, Khokha R, Chambers AF, Groom AC. Fate of melanoma cells entering the microcirculation: over 80% survive and extravasate. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2520–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TH, Avraham HK, Jiang S, Avraham S. Vascular endothelial growth factor modulates the transendothelial migration of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells through regulation of brain microvascular endothelial cell permeability. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(7):5277–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210063200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel CC, Curry FE. Microvascular permeability. Physiol. Reviews. 1999;79(3):703–761. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.3.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel CC, Neal CR. Openings through endothelial cells associated with increased microvascular permeability. Microcirculation. 1999;6(1):45–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay D, Nagy JA, Manseau EJ, Dvorak HF. Vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor-mediated signaling in mouse mesentery vascular endothelium. Cancer Res. 1998;58(6):1278–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mook ORF, Marle J, Vreeling-Sindelarova H, Jongens R, Frederiks WM, Noorden CJK. Visualisation of early events in tumor formation of eGFP-transfected rat colon cancer cells in liver. Hepatology. 2003;38:295–304. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson AK, Dimberg A, Kreuger J, Claesson-Welsh L. VEGF receptor signalling - in control of vascular function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7(5):359–71. doi: 10.1038/nrm1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schluter K, Gassmann P, Enns A, Korb T, Hemping-Bovenkerk A, Holzen J, Haier J. Organ-specific metastatic tumor cell adhesion and extravasation of colon carcinoma cells with different metastatic potential. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:1064–73. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeger W, Hansen T, Rossig R, Schmehl T, Schutte T, Kramer HJ, Walmrath D, Sheldon N, Moy RA, Lindsley K, Shasby S, Shasby DM. Role of myosin light-chain phosphorylation in endothelial cell retraction. Am. J. Physiol. 1993;265:L606–612. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1993.265.6.L606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slattery MJ, Liang S, Dong C. Distinct role of hydrodynamic shear in leukocyte-facilitated tumor cell extravasation. Am. J. Physiol. 2005;288:C831–839. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00439.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinardi L, Einheber S, Cullen T, Milner TA, Giancotti FG. A recombinant tail-less integrin β4 subunit disrupts hemidesmosomes, but does not suppress α6β4-mediated cell adhesion to laminins. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:473–87. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.2.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steeg PS, Theodorescu D. Metastasis: a therapeutic target for cancer. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2008;5(4):206–19. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steeg PS. Tumor metastasis: mechanistic insights and clinical challenges. Nature Rev. 2006;12(8):895–904. doi: 10.1038/nm1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbauer M, Guba M, Cernaianu G, Köhl G, Cetto M, Kunz-Schugart LA, Gcissler EK, Falk W, Jauch KW. GFP-transfected tumor cells are useful in examining early metastasis in vivo, but immune reaction precludes long-term development studies in immunocompetent mice. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2003;20:135–41. doi: 10.1023/a:1022618909921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thamilselvan V, Patel A, van der Voort van Zyp J, Basson MD. Colon cancer cell adhesion in response to Src kinase activation and actin-cytoskeleton by non-laminar shear stress. J Cell Biochem. 2004;92(2):361–71. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzima E, Irani-Tehrani M, Kiosses WB, Dejana E, Schultz DA, Engelhardt B, Cao G, DeLisser H, Schwartz MA. A mechanosensory complex that mediates the endothelial cell response to fluid shear stress. Nature. 2005;437(7057):426–31. doi: 10.1038/nature03952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner MR, Pallone TL. Hydraulic and diffusional pemeabilities of isolated outer medullary descending vasa recta from the rat. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;272(41):H392–H400. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.1.H392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Dentler WL, Borchardt RT. VEGF increases BMEC monolayer permeability by affecting occludin expression and tight junction assembly. Am J Physiol. 2001;280:H434–H440. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.1.H434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis SM, Cheresh DA. Pathophysiological consequences of VEGF-induced vascular permeability. Nature. 2005;437(7058):497–504. doi: 10.1038/nature03987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss L, Orr FW, Honn KV. Interactions of cancer cells with the microvasculature during metastasis. FASEB J. 1988;2:12–21. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.2.1.3275560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu HM, Huang Q, Yuan Y, Grange HJ. VEGF induces NO-dependent hyperpermeability in coronary venules. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;271:H2735–H2739. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.6.H2735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu C, Yago T, Lou J, Zarnitsyna VI, McEver RP. Mechanisms for flow-enhanced cell adhesion. Ann Biomed Eng. 2008;36(4):604–21. doi: 10.1007/s10439-008-9464-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]