Abstract

Upon activation, cytotoxic CD8+ T lymphocytes are desialylated exposing β-galactose residues in a physiological change that enhances their effector activity and that can be monitored on the basis of increased binding of the lectin peanut agglutinin. Herein, we investigated the impact of sialylation mediated by trans-sialidase, a specific and unique Trypanosoma transglycosylase for sialic acid, on CD8+ T cell response of mice infected with T. cruzi. Our data demonstrate that T. cruzi uses its trans-sialidase enzyme to resialylate the CD8+ T cell surface, thereby dampening antigen-specific CD8+ T cell response that might favor its own persistence in the mammalian host. Binding of the monoclonal antibody S7, which recognizes sialic acid-containing epitopes on the 115-kDa isoform of CD43, was augmented on CD8+ T cells from ST3Gal-I-deficient infected mice, indicating that CD43 is one sialic acid acceptor for trans-sialidase activity on the CD8+ T cell surface. The cytotoxic activity of antigen-experienced CD8+ T cells against the immunodominant trans-sialidase synthetic peptide IYNVGQVSI was decreased following active trans-sialidase- mediated resialylation in vitro and in vivo. Inhibition of the parasite's native trans-sialidase activity during infection strongly decreased CD8+ T cell sialylation, reverting it to the glycosylation status expected in the absence of parasite manipulation increasing mouse survival. Taken together, these results demonstrate, for the first time, that T. cruzi subverts sialylation to attenuate CD8+ T cell interactions with peptide-major histocompatibility complex class I complexes. CD8+ T cell resialylation may represent a sophisticated strategy to ensure lifetime host parasitism.

Keywords: Carbohydrate Function, Cellular Immune Response, Enzyme Catalysis, Glycoprotein, Glycosylation, Protozoan, CD43, CD8+ T Cells, Trypanosoma cruzi, Sialic Acid

Introduction

Glycosylation plays important roles in the immune system through modification of cell surface proteins and lipids involved in immune recognition and cell interactions (1). One striking example is the importance of sialylation for T cell homeostasis and differentiation (2, 3). Differential sialylation of CD8αβ co-receptor modulates its affinity for major histocompatibility complex (MHC)3 class I molecules during thymocyte selection (2–4). Mature thymocytes bind peptide-MHC class I complexes less avidly than immature thymocytes as a result of developmentally regulated sialylation, whereas removal of sialic acid residues from the cell surface increases the avidity of CD8αβ-MHC class I interactions in mature thymocytes (2). In addition, differential sialylation plays a regulatory role in antigen (Ag)-dependent CD8+ T cell responses. Upon activation, sialic acid expression is down-regulated at the T cell surface (5, 6). Decreased sialylation enhances reactivity and sensitivity of T lymphocytes for their cognate peptide-MHC class I ligands. Due to decreased cell surface sialylation, Ag-experienced effector and memory T cells require lower doses of peptide-MHC class I ligands for activation, respond more quickly to these stimuli, and detect lower affinity variants of the antigenic ligands compared with naive T cells (7, 8). Indeed, T cell cytolytic activity can be enhanced by sialidase treatment, with a concurrent decrease in cell surface negative charge (9). In addition, desialylated CD8+ T cells undergo more rounds of cell division following contact with Ag (7).

CD8+ T cells are important mediators of the adaptive immune response against infections caused by protozoan parasites, such as Trypanosoma cruzi, Leshmania major, and Plasmodium sp. (10–12). T. cruzi, the agent of American trypanosomiasis, shows remarkable competence to invade and replicate within the cytoplasm of essentially all of the cell types of its mammalian hosts. Although CD8+ T cell-mediated immunity is critical for protection against T. cruzi infection (13), the parasite manages to survive and establish a chronic infection, which results in myocardiopathy (14). During the acute phase of infection, T. cruzi sheds into the serum large amounts of enzymatically active and inactive proteins belonging to the trans-sialidase (TS) family (15). TS is a glycoside hydrolase glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored to the cell surface, which catalyzes the transfer of a sialic acid unit to molecules containing a terminal β-Galp, giving rise to α2,3-linkages, exclusively (16). The TS activity is capable of extensively remodeling the T. cruzi cell surface by using host glycoconjugates as sialyl donors (17, 18). Alternatively, the enzyme may sialylate host cell glycomolecules involved in host immune responses (19) and cell invasion (20).

Here we sought to determine the impact of surface sialylation on CD8+ T cell responses against T. cruzi infection. Our data demonstrate that T. cruzi uses its TS enzyme to resialylate the CD8+ T cell surface, thereby dampening Ag-specific CD8+ T cell responses, thus favoring its own persistence in the mammalian host.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mice

Male BALB/c and C57BL/6 wild-type mice and male ST3Gal-I-deficient mice, generated as previously described (21), all aged 6–8 weeks, were housed at the Laboratório de Animais Transgênicos from Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (Rio de Janeiro, Brasil). All experiments were conducted according to approved institutional guidelines.

Parasites

Bloodstream trypomastigotes of the Y strain were obtained from T. cruzi-infected mice 8 days postinfection (dpi). After adjustment of the parasite concentration, each mouse was inoculated intraperitoneally with 0.1 ml of medium containing 104 trypomastigotes. T. cruzi (Y strain) epimastigotes were cultured in brain-heart infusion medium (Difco) supplemented with 2.5% agar plus 2% rabbit blood, added after autoclaving, once the medium temperature had reached around 50 °C. After solidification, 100 ml of liquid brain-heart infusion medium were added, and the parasites were inoculated into this phase. Cultures were kept for 48 h at 28 °C with shaking (80 rpm). Plasmodium berghei ANKA was used after one in vivo passage in mice. C57BL/6 mice were infected by injecting 106 parasitized red blood cells intravenously. Parasitemia was monitored by examination of Panotico (Laborclin, Pinhais, Brasil)-stained thin blood smears obtained from tail bleed.

Parasitemia was quantified from day 6 to 10 postinfection by microscopic examination of blood collected from the tail vein. The survival index of T. cruzi-infected mice was calculated from a pull of two experiments.

Recombinant TS

Recombinant enzymatically active TS (aTS) and inactive TS (TSY342H), containing the C-terminal repeats, were produced in Escherichia coli MC1061. For this purpose, bacteria were transformed by electroporation with plasmids containing either the wild-type TS insert (TSREP.C) or the inactive mutant TS insert bearing a Tyr342 → His342 substitution (pTrcHisA). The recombinant proteins were purified as described previously (22), and their homogeneity was evaluated by 10% SDS-PAGE. Prior to all experiments, aTS and TSY342H were passed through an agarose-polymyxin B column (Sigma) in order to obtain lipopolysaccharide-free preparations. The lipopolysaccharide content of TS preparations was below detection by the Limulus amebocyte lysate assay (Charles River Endosafe, Charleston, SC).

trans-Sialidase Treatment

BALB/c mice were either untreated or injected intravenously with of 30 μg of aTS or TSY342H 1 h before the T. cruzi infection, as well as on dpi 2 and 3. Untreated controls received only PBS.

trans-Sialidase Activity

trans-Sialidase activity in the plasma of mice was determined incubating 10 μl of plasma in the presence of 0.25 μmol of α2,3-sialyllactose, 0.2 nmol of d-[glucose-1-14C]lactose (PerkinElmer Life Sciences), diluted in 40 μl of Tris/HCl 50 mm, pH 7.2. After incubation at 37 °C for 2 h, the reaction mixture was diluted with 1 ml of water and applied to a column containing 1 ml of Dowex 2X8 (acetate form) equilibrated with water. The d-[glucose-1-14C]lactose was eluted by washing the column with 9 ml of distilled water. The sialylated d-[glucose-1-14C]lactose was eluted with 3 ml of 0.8 m ammonium acetate, and the radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation counting on a Beckman LS 6500 instrument (1 microunit of TS in the plasma was defined as the amount of enzyme required to catalyze the transfer of sialic acid to 1 μmol of radiolabeled lactose/min).

Inhibition of trans-Sialidase Activity by TSY342H

2 × 107 epimastigotes were washed three times and suspended in 1 ml of PBS (10 mm) with 5.5% glucose. Parasites were incubated for 2 h in the presence of different concentrations of TSY342H (0, 10, 50, 100, and 200 μg/ml) and 2 mg/ml fetuin containing a tritiated 7-carbon sialic acid derivative ([Neu7(3H)Ac]fetuin). [Neu7(3H)Ac]fetuin was prepared as by Previato et al. (17) and had a specific activity of 3.26 × 106 cpm/ml. Parasites were harvested on fiberglass filters, and cell-incorporated radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation spectrometry.

For flow cytometry (FCM), parasites (106) were washed and labeled with biotin-conjugated peanut agglutinin (PNA) (Vector Laboratories, Peterborough, UK) for 30 min, followed by incubation with FITC-conjugated streptavidin (Caltag-Medsystems Ltd., Buckingham, UK) for 30 min and analyzed using a BD Biosciences FACSCalibur cytometer.

In Vivo Cytotoxicity Assays

These assays were performed as described (23). Briefly, splenocytes of male BALB/c mice were divided into two populations and labeled with the fluorogenic dye carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) (Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, OR) at final concentrations of 10 μm (CFSEhigh) or 1.0 μm (CFSElow). CFSEhigh cells were pulsed for 40 min at 37 °C with 2.0 μm H-2Kd TS peptide (IYNVGQVSI), whereas CFSElow cells remained unpulsed. Subsequently, CFSEhigh cells were washed and mixed with equal numbers of CFSElow cells, and 20 × 106 total cells were injected intravenously per mouse. Recipient animals were mice that had either been infected or not with T. cruzi. Spleen cells from recipient mice were collected 20 h after transfer, fixed with 1.0% paraformaldehyde, and analyzed by FCM. Percentages of specific lyses were determined using the following formula.

|

In Vitro Cytotoxicity Assays

The induction and measurement of specific cytotoxic activity by CD8+ T cells in vitro were carried out using splenic CD8+ T cells from either non-infected or T. cruzi-infected (15 dpi) BALB/c mice. Splenocytes were depleted of red blood cells by treatment with Tris-buffered ammonium chloride, and T cell-enriched suspensions were obtained by nylon wool filtration (24). CD8+ T cells were further purified through T cell enrichment columns (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) by negative selection, using FITC-labeled anti-CD4 and anti-B220 antibodies (BD PharMingen) plus anti-fluorescein-conjugated magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec). This protocol yielded at least 98% pure CD8+ T cells.

To obtain sialylated cells, CD8+ T cells from infected mice (PNAhigh cells) were treated in vitro with 0.1 mg/ml fetuin as sialic acid donor in the presence of 0.05 units of aTS for 60 min at 37 °C; after washing, their glycophenotype (PNAlow) was confirmed by staining with FITC-conjugated PNA and FCM, as described below.

The A2OJ cell line H-2d was used as the source of stimulator cells in this experiment. These cells were divided into two populations and labeled with the fluorogenic dye CFSE (CFSEhigh and CFSElow) as above. CFSEhigh cells were pulsed for 40 min at 37 °C with 2.0 μm H-2Kd TS peptide (IYNVGQVSI), whereas CFSElow cells remained unpulsed. 2 × 105 cells (1 × 105 CFSElow/1 × 105 CFSEhigh) were cultivated in the presence of CD8+ T cells from naive mice (PNAlow), from infected mice (PNAhigh), or from infected mice and sialylated (PNAlow), using four different ratios of target to responder cells (1:1, 1:10, 1:20, and 1:30). After 24 h, cells were harvested, fixed with 1.0% paraformaldehyde, and analyzed by FCM for CFSE. Percentages of specific lyses were determined using the formula described above.

FCM

Fresh spleen cells were harvested from non-infected or from infected mice on dpi 8 or 15. Cells were washed in PBS (containing 2% fetal bovine serum) and incubated for 30 min at 4 °C with anti-CD16/CD32 for Fc blocking. For phenotypic analysis of T cells by FCM, we performed three-color labeling for 30 min at 4 °C, using allophycocyanin-labeled anti-CD8 and phycoerythrin-labeled anti-CD4 monoclonal antibodies, followed by FITC-labeled antibody anti-CD44 or anti-CD43 (S7). For glycophenotypic analysis of T cells, we used FITC-labeled PNA and TRITC-labeled MAA, in association with the monoclonal antibodies against the two T cells subsets described above. All monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) used in FCM were from BD PharMingen. Cells were washed and resuspended in fluorescence-activated cell sorting buffer (PBS supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum), and data were acquired on a FACSCalibur system using CellQuest software (BD Biosciences). The analyses were carried out with the program WinMDi version 2.8.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as the means ± S.E. of the mean of the number of experiments indicated. Values were compared by Student's t test, and differences were represented as p value.

RESULTS

Active TS Resialylates CD8+ T Cells from T. cruzi-infected Mice

T cell activation is associated with changes in sialylation of surface molecules caused by down-regulation of α2,3-sialyltransferase and α2,6-sialyltransferase activities (25–27). Altered sialylation is revealed by increased binding of plant lectin PNA, which binds to the exposed disaccharide Galβ1–3-GalNAc (28), concurrent with decreased binding of Maackia amurensis lectin (MAA), a lectin specific for α2,3-sialic acid (29).

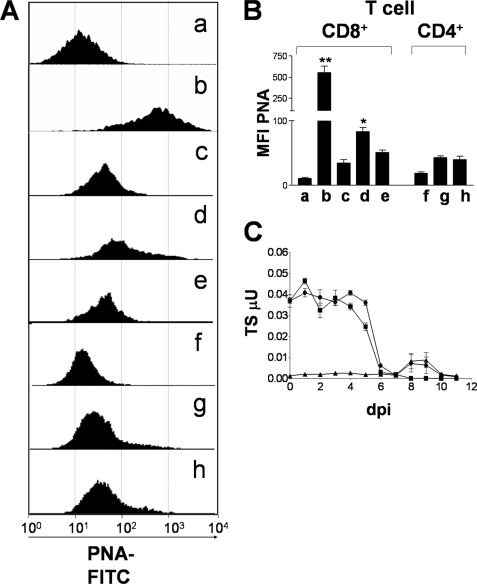

CD8+ T cells activated in vivo by the lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus present increased binding to PNA (5). A similar phenomenon was observed during the protozoan P. berghei infection (Fig. 1, A and B). Accordingly, we found that PNA binding to CD8+ T cells was low for uninfected mice (PNAlow) (Fig. 1A, a and c) but increased markedly (PNAhigh) by day 8 after P. berghei infection (Fig. 1B), suggesting that down-regulation of surface sialic acid expression in CD8+ T cells is ubiquitous during parasitic infections.

FIGURE 1.

aTS resialylates CD8+ T cells from T. cruzi-infected mice. A, PNA binding profile of splenic CD8+ T cells isolated from C57BL/6 uninfected mice (a), P. berghei-infected C57BL/6 mice (b), uninfected BALB/c mice (c), T. cruzi-infected BALB/c mice treated with PBS (d), or T. cruzi-infected BALB/c mice treated with aTS (e) and PNA binding profile of splenic CD4+ T cells isolated from uninfected BALB/c mice (f), T. cruzi-infected BALB/c mice treated with PBS (g), or T. cruzi-infected BALB/c mice treated with aTS (h). Spleen cells were isolated on dpi 8, stained for flow cytometry, gated for CD8+ (a–e) or CD4+ (f–h) cells, and analyzed for PNA binding. B, mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of PNA binding to CD8+ T and CD4+ T cells isolated from mice treated as in A. Bars, the average of three mice. Results are shown as mean of each group of mice ± S.D. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.001 compared with other groups. Note the decrease in PNA binding to CD8+ T cells retrieved from infected mice treated with aTS. C, TS activity was detected in the sera of uninfected BALB/c mice treated with aTS (■), T. cruzi-infected BALB/c mice (▴), and T. cruzi-infected BALB/c mice treated with aTS (●). Each symbol represents data obtained from three mice. Mice were inoculated intraperitoneally on day 0 with 1 × 104 trypomastigotes from T. cruzi Y-strain and/or injected intravenously with 30 μg of aTS 1 h before the infection, as well as on dpi 2 and 3. Untreated controls received only PBS. Blood was collected from the tail vein on the days indicated. TS activity was determined as described under “Experimental Procedures.”

Nevertheless, CD8+ T cells from T. cruzi-infected mice present an intermediary binding to PNA (PNAinterm) (Fig. 1A, d) at 8 dpi, a time at which CD8+ T cells have already been activated and are beginning to expand. Even by 15 dpi, when activation is known to reach its peak, the number of PNA-binding CD8+ T cells had not increased further (result not shown). This shift in glycosylation of CD8+ T cells may be expected due to an increase in the abundance of potential sialic acid acceptors accessible to sialylation through TS activity from T. cruzi during cell activation, rendering resialylated glycoproteins and consequently a decrease in PNA binding. To test this hypothesis, mice were infected and treated with aTS in order to keep high levels of aTS activity throughout the first 8 dpi, a point at which CD8+ T cells have been activated and are expanding (Fig. 1C). A large proportion of CD8+ T cells presented a shift from PNAinterm to PNAlow by 8 dpi (Fig. 1A, e), reaching levels of PNA binding comparable with those of the control group (Fig. 1A, c). This phenomenon was restricted to CD8+ T cells because CD4+ T cells from mice treated with aTS presented only minor changes in PNA binding (Fig. 1A, h) when compared with uninfected (Fig. 1A, f) and control infected groups (Fig. 1A, g).

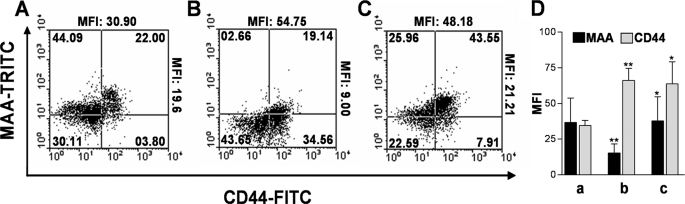

To establish whether aTS transfers sialic acid to activated CD8+ T cells, we stained CD8+ T cells with MAA and CD44 (an activation marker for T cells) (Fig. 2). As shown in Fig. 2, B and D, there was an inverse correlation with activation and MAA binding (Fig 2D, b). We observed that CD8+ T cells from mice infected with T. cruzi and treated with aTS were CD44highMAAhigh (Fig. 2C), suggesting that aTS resialylated only the cell surface of activated CD8+ T cells (CD44+) (Fig. 2C).

FIGURE 2.

aTS resialylates activated CD8+ T cells. Splenic CD8+ T cells were isolated from uninfected BALB/c mice (A), T. cruzi-infected BALB/c mice treated with PBS (B), or T. cruzi-infected BALB/c mice treated with aTS (C), as described in the legend to Fig. 1C. CD8+ T cells were isolated on dpi 15 and stained with MAA (which recognizes α2,3-bound sialic acid) and with anti-CD44 (an activation marker). The numbers indicate the percentage of cells in each quadrant. Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of MAA and anti-CD44 are shown at the right and top of each panel, respectively. D, the bar graph shows the mean of mean fluorescence intensities from each group of three mice treated as in A ± S.D. a, CD8+ T cells from uninfected BALB/c mice; b, CD8+ T cells from T. cruzi-infected BALB/c mice treated with PBS; c, CD8+ T cells from T. cruzi-infected BALB/c mice treated with aTS. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.001 compared with other groups. Observe the increase in the MAA binding to CD8+ T cells from infected mice treated with aTS, indicating that aTS resialylates activated CD8+ T cells.

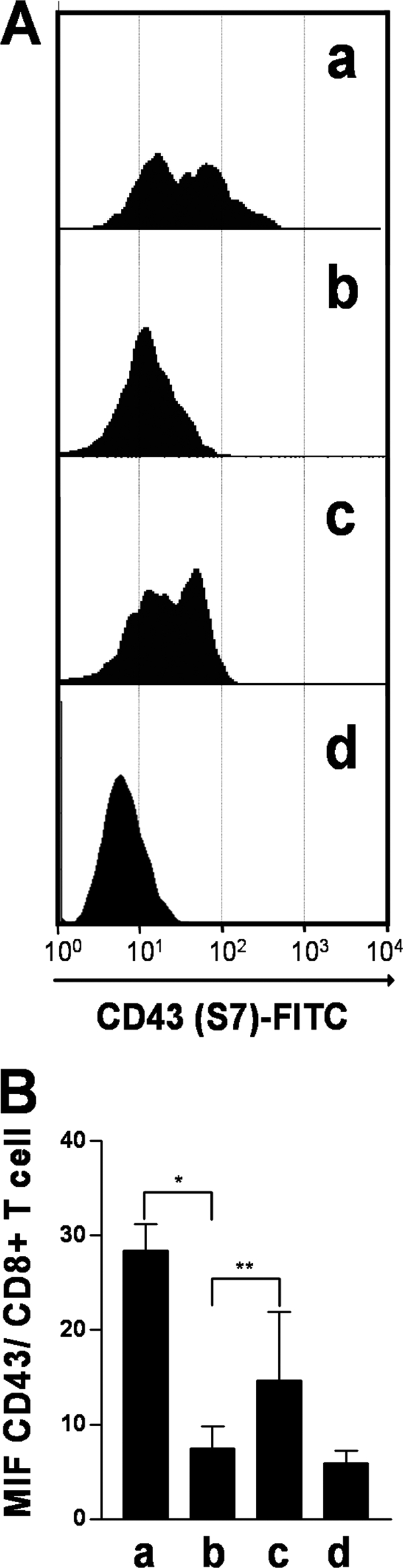

Preferential resialylation of activated CD8+ T cells may be explained by a higher level expression of glycoproteins carrying O- and N-linked oligosaccharides, such as CD43 and CD45 (30), on the CD8+ T cell surface; CD43 is involved in the binding of TS to CD4+ T cells (24, 31). In an attempt to establish the nature of the sialic acid acceptor for aTS on the CD8+ T cell surface, we stained the CD8+ T cell subset with the anti-CD43 mAb S7, which binds to sialic acid-containing epitopes on core 1 O-glycans from the 115-kDa isoform of CD43 (32). CD8+ T cells from mice lacking the ST3Gal-I sialyltransferase (21), an enzyme required for sialylation of core 1 O-glycans, showed a decreased reactivity against anti-CD43 S7 mAb (Fig. 3A, b) when compared with wild type mice (Fig 3A, a). Infection of ST3Gal-I-deficient mice with T. cruzi partially restores binding of anti-CD43 S7 mAb to T CD8+ T cells (Fig. 3A, c), suggesting that CD43 on the CD8+ T cell surface is the sialic acid acceptor for native TS during T. cruzi infection. This result was observed in all ST3Gal-I-deficient mice infected with T. cruzi (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 3.

CD43 is a sialic acid acceptor on CD8+ T cell surface. A, purified CD8+ T cells from uninfected C57BL/6 wild type mice (a), uninfected ST3Gal-I sialyltransferase-deficient C57BL/6 mice (b), and T. cruzi-infected ST3Gal-I sialyltransferase deficient C57BL/6 mice (c) were stained with the mAb S7, which recognizes sialylated forms of CD43. d, isotype control. B, results are shown as the mean of each group of mice ± S.D. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.06. Note that infection of ST3Gal-I sialyltransferase-deficient mice with T. cruzi partially restores the anti-CD43 S7 mAb epitope.

Resialylated CD8+ T Cells Show Decreased Ag Sensitivity in Vitro and in Vivo

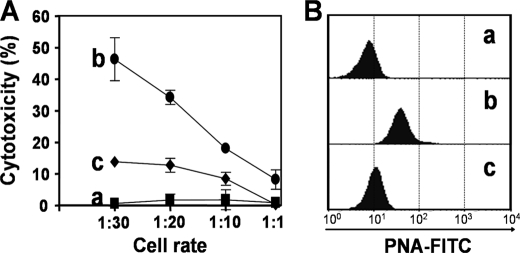

Sialic acid residues contain a negative charge, and therefore their presence on cell surfaces is thought to reduce cell-cell interactions as a result of charge repulsion (1). Our data raised the possibility that resialylation of CD8+ T cells, as a result of TS activity, could compromise CD8+ T cell responses in hosts infected with T. cruzi. To confirm this hypothesis, we purified CD8+ T cells from T. cruzi-infected mice. Cells were resialylated or not (control) in vitro, using fetuin as a sialic acid donor and aTS. Cytotoxicity was evaluated with A20J target cells (H-2d) coated with an immunodominant synthetic peptide (IYNVGQVSI) expressed by members of the TS family (23, 33). After incubation for 20 h over a range of effector/target ratios, the cytolysis of target cells was measured by FCM. CD8+ T cells from uninfected mice (PNAlow) were used as controls. Untreated cells from infected mice displayed the strongest cytotoxic activity at all effector/target ratios tested (Fig. 4A). Resialylation of CD8+ T cells from T. cruzi-infected mice decreased cytotoxicity by 72% (Fig. 4A); statistical analysis showed that resialylated CD8+ T cells were less effective at all target/effector cell ratios tested. Analysis of PNA binding by FCM confirmed that CD8+ T cells from infected mice were PNAinterm (Fig. 4B, histogram b) and that treatment with aTS and fetuin resialylated the CD8+ T cells, generating PNAlow cells (Fig. 4B, histogram c). These observations demonstrated that resialylation of Ag-experienced CD8+ T cells renders them unresponsive to antigenic restimulation.

FIGURE 4.

aTS-mediated resialylation decreases CD8+ T cell-mediated cytotoxicity in vitro. A, CD8+ T cells were isolated from uninfected mice (a, ■), or T. cruzi-infected mice and were either treated with PBS (b, ●), or with 50 milliunits of aTS plus 100 μg/ml of fetuin as sialic acid donor for 60 min at 37 °C (c, ♦). A2OJ cells (H-2d), used as targets, were previously treated with the fluorogenic dye CFSE (1 and 10 μm). The population treated with 10 μm was additionally incubated with the immunodominant H-2Kd-restricted synthetic peptide IYNVGQVSI. The population treated with 1 μm (control cells) remained untreated. After incubation for 20 h over a range of effector/target ratios, lysis of target cells was quantified by flow cytometry. B, cPNA binding profile of CD8+ T cells isolated from uninfected mice (a) or from T. cruzi-infected mice either treated with PBS (b) or with 0.05 units of aTS plus 100 μg/ml of fetuin as in A (c).

We also tested the effect of aTS-mediated resialylation on Ag-specific responses of CD8+ T cells in vivo. We used the protocol for in vivo cytotoxicity described by Tzelepis et al. (23, 33), which employs the same synthetic peptide as above and splenocytes labeled with CFSE as target cells. Uninfected recipients were used as controls. In agreement with the results of Tzelepis et al. (23, 33), more than 94% specific cytolysis was detected on dpi 15 in the infected mice treated with PBS (Fig. 5, A (b) and B (b)). In contrast, in infected mice treated with aTS, only 68% of the target cells coated with synthetic peptide were eliminated in vivo (Fig. 5, A (c) and B (c)). The specificity of lysis of target cells (CFSE (10 μm) plus coating with IYNVGQVSI) was illustrated by the disappearance of this population but not the control population (CFSE (1 μm), no peptide) in the dot plots presented (Fig. 5A). Analysis of PNA binding by FCM confirmed that CD8+ T cells from infected mice were PNAinterm and that treatment with aTS in vivo resialylated the CD8+ T cells, decreasing PNA binding (Fig. 5C). These results supported the notion that resialylation of CD8+ T cells by aTS compromises CD8+ T cell responses in vivo.

FIGURE 5.

aTS-mediated resialylation decreases Ag sensitivity in vivo. BALB/c mice were either uninfected (a) or infected with T. cruzi and treated with PBS (b) or aTS (c), as described under “Experimental Procedures.” A, three groups of mice were subjected to an in vivo Ag-specific CD8+ T cell cytotoxicity assay. For this purpose, target cells loaded with the synthetic peptide IYNVGQVSI were inoculated, and Ag-specific lysis was assessed on the basis of their disappearance (CFSE, 10 μm); a control population not loaded with peptide and inoculated in parallel was spared (CFSE, 1 μm), confirming Ag specificity. B, quantitation of the cytotoxic activity in A. Cytotoxicity of CD8+ T cells from infected mice treated with PBS (b) was significantly higher than that of cells from mice treated with aTS (c). *, p < 0.05. C, glycophenotypic analysis of CD8+ T cells from the three experimental groups, evaluated by FCM using the lectin PNA. Note that treatment with aTS decreases PNA binding to CD8+ T cells.

Enzymatically Inactive TS Antagonizes Resialylation of CD8+ T Cells Mediated by Native TS

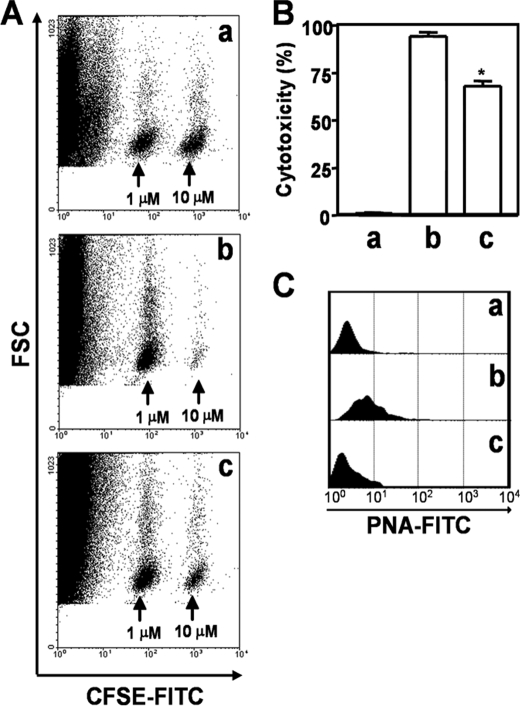

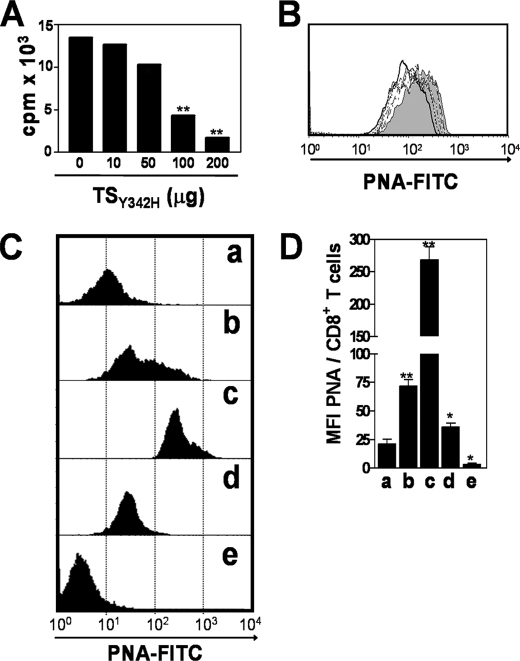

To assess changes in sialylation of T cells triggered by the native T. cruzi TS activity, we searched for an enzyme inhibitor or antagonist. Because there are no strong inhibitors of TS yet reported, we first established whether native TS from T. cruzi epimastigotes could be inhibited in vivo by an inactive analog presenting a Tyr342 → His mutation (TSY342H) and known to bind to α2,3-sialosides and terminal β-Galp-containing glycoconjugates with the same specificity as active TS (31, 34). Thus, epimastigotes, grown in BHI-hemin medium in the absence of fetal calf serum or any sialic acid source, were treated with [Neu7(3H)Ac]fetuin in the presence of increasing concentrations of TSY342H (0, 10, 50, 100, and 200 μg/ml). As shown in Fig. 6A, TSY342H inhibited the incorporation of Neu7(3H)Ac on epimastigote glycoproteins in a dose-dependent manner. Similar results were obtained when epimastigotes, treated with fetuin in the presence of increasing concentrations of TSY342H, were labeled with PNA (Fig. 6B). PNA binding to epimastigotes was maximal in the absence of TSY342H (gray histogram), decreased as TSY342H concentration was increased (dotted histograms), and was minimal at 200 μg/ml TSY342H (solid line). These results demonstrate that TSY342H impairs sialic acid transfer catalyzed by the active native TS enzyme. In agreement with these observations, CD8+ T cells from infected mice treated with 30 μg of TSY342H 1 h before and at 2 and 3 dpi with T. cruzi presented a larger increase in PNA binding (Fig. 6, C (c) and D (c)) than those from infected mice treated with PBS (Fig. 6, C (b) and D (b)) and those from uninfected mice treated with TSY342H (Fig. 6C, histogram e). These results suggest that TSY342H competes in vivo with the native T. cruzi TS for sialic acid and galactose binding sites, thus inhibiting a sialylation event that otherwise normally takes place during parasite infection. Thus, the sialylation level of CD8+ T cells from untreated infected mice can be viewed as “intermediate” (PNAinterm) (Fig. 6, C (b) and D (b)) and can be increased to levels close to those of naive cells by intervention with aTS (PNAlow) (Fig. 6, C (c) and D (c)) or, on the contrary, decreased to very low levels by inoculation of TSY342H (PNAhigh) (Fig. 6, C (b) and D (b)). This latter low sialic acid (very high PNA binding) phenotype is the one that should probably be expected to prevail in an acute infection in the absence of pathogen-derived TS. These PNAhigh CD8+ T cells would have its full effectors activity controlling more efficiently T. cruzi infection. This presumption implies that TSY342H might decrease T. cruzi virulence by increasing CD8+ T cell response directed against the parasite. To test this hypothesis, BALB/c mice received 30 μg of aTS or TSY342H 1 h before infection as well as at 2 and 3 dpi, and survival was compared with infected mice treated with PBS only. Infected mice treated with aTS displayed increased parasitemia (Fig. 7A) and susceptibility to infection, exhibiting 100% mortality at day 23, compared with control mice which exhibited 100% mortality at day 28 (Fig. 7B). Administration of TSY342H delayed the mortality of infected mice, and 30% of the mice survived for >30 days (Fig. 7B).

FIGURE 6.

An inactive TS inhibits resialylation mediated by endogenous aTS. A, incorporation of Neu7(3H)Ac by T. cruzi epimastigotes incubated with [Neu7(3H)Ac]fetuin (3.26 × 106 cpm/ml) in the presence of TSY342H (0, 10, 50, 100, and 200 μg/ml). B, PNA binding to T. cruzi epimastigotes incubated with fetuin (2 mg/ml) in the presence of 0 μg (gray histogram), 10 μg (long dashed line), 50 μg (dashed line), 100 μg (heavy dashed line), and 200 μg (solid line) of TSY342H. C, PNA binding to splenic CD8+ T cells isolated from uninfected mice (a), from T. cruzi-infected mice treated with PBS (b), from T. cruzi-infected mice treated with TSY342H (c), from T. cruzi-infected mice treated with aTS (d), and from uninfected mice treated with TSY342H (e). Mice were inoculated intraperitoneally on day 0 with 1 × 104 trypomastigotes from T. cruzi Y-strain. Treated mice were injected intravenously with 30 μg of aTS or 30 μg of TSY342H 1 h before the infection as well as on dpi 2 and 3. Untreated controls received only PBS. D, bar graph showing the mean of mean fluorescence intensities (MFI) from each group of three mice treated as in C ± S.D. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.001 compared with control group. Note the increase in PNA binding to CD8+ T cells from infected mice treated with TSY342H.

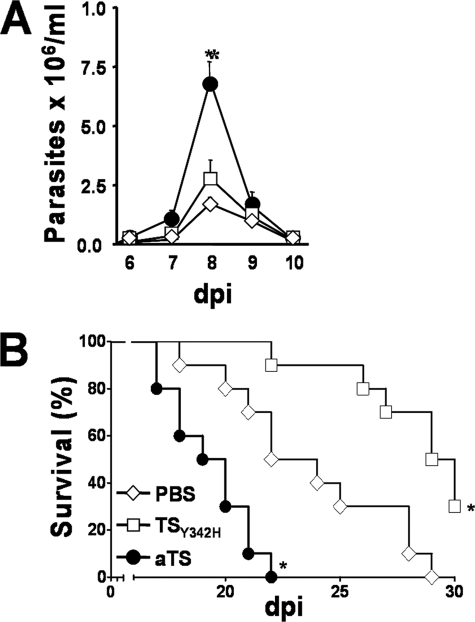

FIGURE 7.

TSY342H decreases T. cruzi virulence. A, parasitemia of T. cruzi-infected mice treated with PBS (◊), TSY342H (□), or aTS (●), as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Data are the mean ± S.D. of the parasites counting on 10 mice/group. Shown is one of three experiments performed. B, survival index of T. cruzi-infected mice treated as above. Survival data are pooled from two different experiments with 10 mice each. BALB/c mice received 30 μg of aTS or TSY342H 1 h before and at 2 and 3 dpi with T. cruzi. Data were compared with a control-infected group treated with PBS. *, p < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

Several studies have demonstrated the importance of differential sialylation for CD8+ T cells with respect to their development (2), activation via the TCR (7), and cytotoxic responses (9). However, no study is available that provides insights into the impact of surface sialylation of CD8+ T cells on the responses to pathogenic microorganisms. Infection with T. cruzi is of particular interest in this context because the parasite releases into the host plasma large amounts of enzymatically active as well as inactive proteins belonging to the trans-sialidase family (15). Our results provide for the first time evidence that T. cruzi modifies CD8+ T cell sialylation, compromising Ag-specific CD8+ T cell responses during infection. Manipulation of sialic acid on CD8+ T cells seems to be a refined evasion mechanism employed by T. cruzi to guarantee its replication in the host.

T. cruzi infects a wide range of cells, escapes the endocytic vacuole, and replicates in the host cell cytoplasm (35). Within the cytoplasm, T. cruzi releases proteins that are the source of peptides presented by MHC class I for their recognition by CD8+ T cells (36). Despite robust and persistent CD8+ T cell responses both in mice and humans, the parasite survives, establishing chronic infections. Proteins from the TS family are the main targets of T. cruzi-specific CD8+ T cells (37, 38). However, there is a substantial delay in the appearance of the CD8+ T cell responses following infection (33, 37, 39). This delay contrasts with the rapid appearance of CD8+ T cell responses in other viral, bacterial, and even protozoal infections (40) and suggests that a mechanism of immune evasion is operative. Our present results indicate that increased sialylation of CD8+ T cells leads to a requirement for higher concentrations of Ag in order to express effector activity. Sialylation of CD8+ T cells by TS could be the mechanism that delays CD8+ T cell responses during T. cruzi infection.

Infection with T. cruzi leads to sustained and intense T cell activation. During T cell activation, down-regulation of sialyltransferases (25–27) renders potential sialic acid acceptors accessible to sialylation through TS activity. This sialylation may be advantageous to the parasite, because CD8+ T cells resialylated by aTS present compromised Ag-specific responses and aTS-treated mice present increased parasitemia. The regulatory mechanism by which cell surface sialic acid regulates CD8+ T cell activity is unknown. However, our results may be straightforwardly explained on the basis that sialic acid increases intercellular repulsion and therefore weakens TCR/MHC class I-mediated cell-cell interactions. This would be the opposite of the effect of neuraminidase treatment, which removes sialic acid residues from various membrane glycoproteins, including CD43 and CD45 (41), and concomitantly enhances lymphocyte proliferation (7, 9).

Our findings also indicated that CD43 is a target receptor for TS on the CD8+ T cell surface. However, resialylation by aTS was also observed on CD8+ T cells from CD43 KO mice, suggesting that in the absence of CD43, other molecules are substrates for aTS (results not shown). Despite this, its high surface density on CD8+, the pronounced length of its protruding molecules, and its abundance in O-linked oligosaccharides (42) all support CD43 as receptor for T. cruzi TS. Previous studies indicate that both active and inactive TS proteins initiate costimulatory responses that increase mitogenesis and cytokine secretion as well as promote the rescue from apoptosis (24), through binding to α2,3-linked sialic acid-containing epitopes, shared by the anti-CD43 S7 mAb, on CD43 from host CD4+ T cells (31). The anti-CD43 S7 mAb recognizes sialic acid-containing epitopes on the 115-kDa isoform of CD43, which bears core 1 O-glycans (32). Loss of ST3Gal-I sialyltransferase abrogates binding of anti-CD43 S7 mAb to CD8+ T cells, exposing the Galβ1–3GalNAc-Ser/Thr and creating an interesting model to establish CD43 as a natural receptor for native TS during T. cruzi infection. Indeed, infection of mice lacking ST3Gal-I sialyltransferase restores, at least in part, binding of anti-CD43 S7 mAb to CD8+ T cells.

The inactive analog of trans-sialidase TSY342H presents a single point mutation, Tyr342 → His. The Tyr342 residue is involved in the stabilization of the transition state sialyl carbocation formed during the hydrolysis reaction of the active TS, and the presence of His342 impairs enzymatic activity (43). Todeschini et al. (31, 34) demonstrated that the TSY342H mutant of trans-sialidase is a sialic acid-binding protein, displaying the same specificity required by active trans-sialidase. It was demonstrated that TSY342H physically interacts with the sialic acid from the sialomucin CD43 on CD4+ T cells (31). Data presented in Fig. 6, C and D, show that active and inactive TS have opposite effects.

We demonstrate that TSY342H competes in vivo with the native T. cruzi TS for sialic acid and galactose binding sites, thus inhibiting a sialylation event that takes place during parasite infection. In sum, our results suggest that physiological desialylation, associated with CD8+ T cell activation during infection, might be countered by TS as part of the parasite's manipulation of the host immune system. This resialylation by TS is, however, not complete, because splenic CD8+ cells from T. cruzi-infected mice do increase their expression of PNA sites by TSY342H treatment (Fig. 6). These PNAhigh CD8+ T cells control more efficiently T. cruzi infection, decreasing parasite virulence and increasing mouse survival. However, further studies are still needed to be certain about the significance of this mechanism in physiological conditions. Use of TS inhibitors may shed some light on the importance of the enzyme to CD8+ T cell function. Current work to prove our hypothesis is under way in our laboratories.

Together, these observations support the hypothesis that TS enhances T. cruzi virulence by altering host immune responses directed against the parasite (44). Collectively, our results identify TS as an important parasite molecule, which may be responsible for dampening host CD8+ T cell responses.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Fanny Tzelepis (Universidade Federal de São Paulo-Escola Paulista de Medicina) for helping with the cytotoxic assays.

This work was supported by grants from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Programa de Apoio ao Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (PADCT)/World Bank/CNPq, Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ/PRONEX), Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), CAPES/Cooperação Universitária e Científica com o Brasil (Cofecub), and the National Institute for Science and Technology in Vaccines.

- MHC

- major histocompatibility complex

- Ag

- antigen

- aTS

- recombinant active trans-sialidase

- CFSE

- carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester

- FCM

- flow cytometry

- FITC

- fluorescein isothiocyanate

- TSY342H

- recombinant inactive trans-sialidase

- MAA

- Maackia amurensis lectin

- mAb

- monoclonal antibody

- Neu7(3H)Ac

- tritiated 7-carbon sialic acid derivative

- dpi

- day(s) postinfection

- PNA

- peanut agglutinin

- TS

- trans-sialidase

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- TRITC

- tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate.

REFERENCES

- 1.Varki N. M., Varki A. (2007) Lab. Invest. 87, 851–857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moody A. M., Chui D., Reche P. A., Priatel J. J., Marth J. D., Reinherz E. L. (2001) Cell 107, 501–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daniels M. A., Devine L., Miller J. D., Moser J. M., Lukacher A. E., Altman J. D., Kavathas P., Hogquist K. A., Jameson S. C. (2001) Immunity 15, 1051–1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moody A. M., North S. J., Reinhold B., Van Dyken S. J., Rogers M. E., Panico M., Dell A., Morris H. R., Marth J. D., Reinherz E. L. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 7240–7246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galvan M., Murali-Krishna K., Ming L. L., Baum L., Ahmed R. (1998) J. Immunol. 161, 641–648 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harrington L. E., Galvan M., Baum L. G., Altman J. D., Ahmed R. (2000) J. Exp. Med. 191, 1241–1246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pappu B. P., Shrikant P. A. (2004) J. Immunol. 173, 275–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kao C., Daniels M. A., Jameson S. C. (2005) Int. Immunol. 17, 1607–1617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sadighi Akha A. A., Berger S. B., Miller R. A. (2006) Immunology 119, 187–194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bustamante J. M., Bixby L. M., Tarleton R. L. (2008) Nat. Med. 14, 542–550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belkaid Y., Von Stebut E., Mendez S., Lira R., Caler E., Bertholet S., Udey M. C., Sacks D. (2002) J. Immunol. 168, 3992–4000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morrot A., Zavala F. (2004) Immunol. Rev. 201, 291–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tarleton R. L. (1990) J. Immunol. 144, 717–724 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rossi M. A. (1995) São Paulo Med. J. 113, 750–756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frasch A. C. (2000) Parasitol. Today 16, 282–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vandekerckhove F., Schenkman S., Pontes de Carvalho L., Tomlinson S., Kiso M., Yoshida M., Hasegawa A., Nussenzweig V. (1992) Glycobiology 2, 541–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Previato J. O., Andrade A. F., Pessolani M. C., Mendonça-Previato L. (1985) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 16, 85–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Previato J. O., Andrade A. F., Vermelho A., Firmino J. C., Mendonça-Previato L. (1990) Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 85, 38 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mucci J., Risso M. G., Leguizamón M. S., Frasch A. C., Campetella O. (2006) Cell Microbiol. 8, 1086–1095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dias W. B., Fajardo F. D., Graça-Souza A. V., Freire-de-Lima L., Vieira F., Girard M. F., Bouteille B., Previato J. O., Mendonça-Previato L., Todeschini A. R. (2008) Cell Microbiol. 10, 88–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Priatel J. J., Chui D., Hiraoka N., Simmons C. J., Richardson K. B., Page D. M., Fukuda M., Varki N. M., Marth J. D. (2000) Immunity 12, 273–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Todeschini A. R., Mendonça-Previato L., Previato J. O., Varki A., van Halbeek H. (2000) Glycobiology 10, 213–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tzelepis F., de Alencar B. C., Penido M. L., Claser C., Machado A. V., Bruna-Romero O., Gazzinelli R. T., Rodrigues M. M. (2008) J. Immunol. 180, 1737–1748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Todeschini A. R., Nunes M. P., Pires R. S., Lopes M. F., Previato J. O., Mendonça-Previato L., DosReis G. A. (2002) J. Immunol. 168, 5192–5198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Comelli E. M., Sutton-Smith M., Yan Q., Amado M., Panico M., Gilmartin T., Whisenant T., Lanigan C. M., Head S. R., Goldberg D., Morris H. R., Dell A., Paulson J. C. (2006) J. Immunol. 177, 2431–2440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amado M., Yan Q., Comelli E. M., Collins B. E., Paulson J. C. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 36689–36697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chervenak R., Cohen J. J. (1982) Thymus 4, 61–67 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pereira M. E., Kabat E. A., Lotan R., Sharon N. (1976) Carbohydr. Res. 51, 107–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang W. C., Cummings R. D. (1988) J. Biol. Chem. 263, 4576–4585 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pace K. E., Lee C., Stewart P. L., Baum L. G. (1999) J. Immunol. 163, 3801–3811 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Todeschini A. R., Girard M. F., Wieruszeski J. M., Nunes M. P., DosReis G. A., Mendonca-Previato L., Previato J. O. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 45962–45968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones A. T., Federsppiel B., Ellies L. G., Williams M. J., Burgener R., Duronio V., Smith C. A., Takei F., Ziltener H. J. (1994) J. Immunol. 153, 3426–3439 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tzelepis F., de Alencar B. C., Penido M. L., Gazzinelli R. T., Persechini P. M., Rodrigues M. M. (2006) Infect. Immun. 74, 2477–2481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Todeschini A. R., Dias W. B., Girard M. F., Wieruszeski J. M., Mendonça-Previato L., Previato J. O. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 5323–5328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tyler K. M., Engman D. M. (2001) Int. J. Parasitol. 31, 472–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garg N., Nunes M. P., Tarleton R. L. (1997) J. Immunol. 158, 3293–3302 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin D. L., Weatherly D. B., Laucella S. A., Cabinian M. A., Crim M. T., Sullivan S., Heiges M., Craven S. H., Rosenberg C. S., Collins M. H., Sette A., Postan M., Tarleton R. L. (2006) PLoS Pathog. 2, e77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tarleton R. L. (2007) Curr. Opin. Immunol. 19, 430–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tzelepis F., Persechini P. M., Rodrigues M. M. (2007) PLoS ONE 2, e393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaech S. M., Hemby S., Kersh E., Ahmed R. (2002) Cell 111, 837–851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garcia G. G., Berger S. B., Sadighi Akha A. A., Miller R. A. (2005) Eur. J. Immunol. 35, 622–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ostberg J. R., Barth R. K., Frelinger J. G. (1998) Immunol. Today 19, 546–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cremona M. L., Sánchez D. O., Frasch A. C., Campetella O. (1995) Gene 160, 123–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chuenkova M., Pereira M. E. (1995) J. Exp. Med. 181, 1693–1703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]