Abstract

The α6β4 integrin is a laminin 332 (LN332) receptor central to the formation of hemidesmosomes in epithelial layers. However, the integrin becomes phosphorylated by keratinocytes responding to epidermal growth factor in skin wounds or by squamous cell carcinomas that overexpress/hyperactivate the tyrosine kinase ErbB2, epidermal growth factor receptor, or c-Met. We show here that the β4-dependent signaling in A431 human squamous carcinoma cells is dependent on the syndecan family of matrix receptors. Yeast two-hybrid analysis identifies an interaction within the distal third (amino acids 1473–1752) of the β4 cytoplasmic domain and the conserved C2 region of the syndecan cytoplasmic domain. Via its C2 region, Sdc1 forms a complex with the α6β4 integrin along with the receptor tyrosine kinase ErbB2 and the cytoplasmic kinase Fyn in A431 cells. Engagement of LN332 or clustering of the α6β4 integrin with integrin-specific antibodies causes phosphorylation of ErbB2, Fyn, and the β4 subunit as well as activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and Akt and their assimilation into this complex. This leads to phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent cell spreading and Akt-dependent protection from apoptosis. This is disrupted by RNA interference silencing of Sdc1 but can be rescued by mouse Sdc1 or Sdc4 but not by syndecan mutants lacking their C-terminal C2 region. This disruption does not prevent the phosphorylation of ErbB2 or Fyn but blocks the Fyn-mediated phosphorylation of the β4 tail. We propose that syndecans engage the distal region of the β4 cytoplasmic domain and bring it to the plasma membrane, where it can be acted upon by Src family kinases.

Keywords: Cell Adhesion, Cell Surface Receptor, Extracellular Matrix, Integrin, Laminin, Cancer, Receptor Signaling, Syndecan

Introduction

The α6β4 integrin is a laminin 332 (LN332,2 also known as LN5 or kalinin) receptor that forms hemidesmosomes in epithelial cells (reviewed in Refs. 1–4). It engages LN332 linked to collagen VII anchoring fibrils in the extracellular matrix (5) and simultaneously engages cytoplasmic proteins (e.g. plectin and BP230) and the transmembrane protein BP180 via the long (∼1,000-amino acid) cytoplasmic domain of the β4 integrin subunit. These cytoplasmic interactions involve two pairs of fibronectin type III (FNIII) repeats in the β4 tail and the connecting segment joining these pairs. This couples the integrin to the intermediate filament cytoskeleton and provides a stable anchorage that resists frictional forces on the epithelium.

In contrast to this stabilizing role of the α6β4 integrin, phosphorylation of the β4 cytoplasmic domain causes hemidesmosome disassembly and activation of α6β4 signaling. Skin wounding causes relocalization of the integrin to lamellipodia of invading keratinocytes in response to EGF or macrophage-stimulating factor (6). In tumor cells, overexpression of the integrin or overexpression and/or hyperactivation of the receptor tyrosine kinase c-Met (hepatocyte growth factor receptor), ErbB1 (EGFR), or ErbB2 causes phosphorylation of the integrin and promotes the proliferation, survival, and invasion of the tumor cells (7–9). The sites targeted by these kinases appear to lie in the distal third of the β4 cytoplasmic domain. Mice expressing β41355T in which this distal signaling domain has been truncated show impaired wound healing and angiogenesis, but normal hemidesmosomes; additionally, overexpression of β4 subunit in mice overexpressing ErbB2 enhances tumor formation, whereas β41355T does not (10).

Activation of the integrin includes its phosphorylation on both serine and tyrosine. Of critical importance is protein kinase C-mediated phosphorylation of Ser-1356, Ser-1360, and Ser-1364 in the connecting segment between the two pairs of FNIII repeats (11, 12); phosphorylation of these sites causes disruption of hemidesmosomes, ostensibly via disrupting conformation of the β4 cytoplasmic domain necessary for plectin binding (13). Tyrosine phosphorylation on one or more tyrosines may also disrupt the binding of plectin and/or BP230 or BP180 (14, 15) as well as provide docking sites for the scaffolding protein Shc and/or IRS1/2 and their subsequent recruitment of PI3K and other signaling effectors, including c-Jun and STAT3 (10, 16, 17). Phosphorylated Shc binds tyrosine 1440 via its Src homology 2 domain and tyrosine 1526 via its phosphotyrosine binding domain, with the latter interaction being critical for recruitment of Grb2 and activation of Ras and Erk (14). IRS docked to tyrosine 1494 in the third FNIII repeat recruits the p85 regulatory subunit of PI3K, and the subsequent activation of PI3K and its downstream target Akt, which leads to anchorage-independent growth, increased cell invasion and Akt-mediated protection against apoptosis in carcinoma cells bearing defective p53 (18–24). Tyrosines 1257, 1440, and 1494 also bind the Src homology 2 domain of the tyrosine phosphatase SHP2, which serves to activate Src signaling downstream of the integrin (18, 19, 21). Interestingly, recent work suggests that increased expression of β4 can also have a growth-suppressive effect in those cases where it retains plectin binding capability (25). The α6β4 integrin can also be stimulated by ErbB2 in human keratinocytes to block haptotaxis on LN332 mediated by the α3β1 integrin and to up-regulate E-cadherin expression (26). Thus, the outcome of α6β4 phosphorylation appears complex and may depend on multiple factors and cellular contexts.

Although ErbB2, EGFR, and c-Met can associate directly with the α6β4 integrin, it is not clear that they directly phosphorylate the integrin. ErbB2 and EGFR activate the Src family kinase (SFK) Fyn, which is associated with the membrane-proximal domain of the β4 tail and appears to carry out integrin phosphorylation (8, 10). The activated integrin then feeds back via enhanced SFK activity to hyperactivate ErbB2 (8, 10). It is not immediately clear how this is accomplished because the distal portion of the α6β4 cytoplasmic domain must be brought into close proximity to the membrane-associated SFKs and Ras GTPase in order to activate this signaling.

A second class of receptor that binds LN332 is the syndecan family of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans. This family of receptors is composed of syndecans 1–4, of which syndecan 1 (Sdc1) is abundantly expressed on epithelial cells (27, 28). Emerging work suggests that the syndecans act as co-receptors to regulate the signaling of integrins and growth factor receptors at the cell surface (29). For example, Sdc1 associates directly with the αvβ3 and αvβ5 integrins present on carcinoma and vascular endothelial cells and controls the activation of these integrins during carcinoma cell invasion and during angiogenesis (30–32). Sdc4 is known to localize to fibronectin-rich focal adhesions with the α5β1 integrin and to work in concert with the integrin to generate matrix-dependent signals (33–35). Thus, the syndecans, by virtue of their heparan sulfate chains binding most or all matrix components, may serve as organizers of matrix adhesion and signaling by recruiting integrins and growth factor receptors and activating them at matrix adhesion sites.

Syndecans 1, 2, and 4 have been shown to engage the heparin binding domain present in the LG4,5 module of the LN332 α3 chain. Engagement of LG4,5 enhances keratinocyte cell spreading and migration (36–38), which probably traces to Sdc1 because of its high expression on keratinocytes. Interestingly, it is proposed that this is regulated by phosphorylation of the C2 region of the syndecan cytoplasmic domain and its interaction with the PDZ domain of syntenin (39). In addition, Sdc1 has been shown to interact with the γ2 chain of LN332 (40). However, this interaction is suggested to promote cell adhesion but to disrupt cell migration (40). Thus, the response of cells to syndecan engagement with LN332 is complex.

We report here for the first time that the syndecans interact directly with the α6β4 integrin and regulate its activation by ErbB2 (also known as Neu or Her2) in A431 squamous carcinoma cells. The interaction requires the C2 region of the syndecan cytoplasmic domain, which engages the distal signaling region of the β4 integrin cytoplasmic domain. Although this requires Sdc1 in the A431 cells, presumably due to its predominant cell surface expression, the signal can be rescued by expression of Sdc4; indeed, yeast two-hybrid analysis indicates that each of the four syndecans can carry out this binding interaction. Silencing of Sdc1 expression blocks phosphorylation of the β4 subunit but does not affect the activation of ErbB2 or Fyn upstream of the integrin. Thus, we conclude that the β4-syndecan interaction is critical for targeting of the β4 tail by the SFK. Blockade of this interaction also prevents the α6β4-mediated protection of the cells from apoptosis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Antibodies and Reagents

Antibodies used were mouse mAb 3E1 (Chemicon, Temecula, CA) and rat mAb 439-9B (BD Biosciences) to the β4 ectodomain; mouse β4 mAb (BD Biosciences) to the β4 cytoplasmic domain; rat mAb GoH3 (BD Biosciences) to the α6 integrin subunit; mouse mAbs B-A38 (Accurate Chemical and Scientific, Westbury, NY) and 150.9 (University of Alabama Hybridoma Facility) to human Sdc1 and human Sdc4, respectively; anti-AKT from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA) and GD11 (UBI Life Sciences, Saskatoon, Canada) against Src; FYN15 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) against Fyn; AB6 to PI3K p85α (Abcam, Cambridge, MA); and anti-c-ErbB-2 Ab-15 (clone 3B5) (Fisher) specific for ErbB2. We used rat mAb 281.2 (65) or KY 8.2 (66) that recognize mouse Sdc1 or mouse Sdc4, respectively, and rat mAb (mAb13) to human integrin β1 (kindly provided by Dr. Steven Akiyama (NIEHS, National Institutes of Health)). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies were used to the anti-phospho-Src family (Tyr-416) and anti-phospho-AKT (Ser-473) from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.

ErbB2 inhibitor AG825 and Src family kinase inhibitor PP2 were from Calbiochem, PI3K inhibitor wortmannin was from Sigma, and LY294002 was from Fisher. Human laminin 5 (LN332) and laminin 1 (LN111) were from Biodesign (Saco, ME) or R & D Systems (Minneapolis, MN); DME medium was from Invitrogen; GammaBind G-Sepharose beads were from Amersham Biosciences; and heparinase II and chondroitin ABC lyase were from IBEX Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Montréal, Canada) and Sigma, respectively. Annexin V conjugated with Alexa Fluor® 488 and rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin was obtained from Invitrogen.

Yeast Two-hybrid Screen and Syndecan Mutants

A yeast two-hybrid screen was conducted using the Matchmaker3 yeast two-hybrid system (Clontech) and a human keratinocyte library (Clontech catalog no. HL4030AH) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The library consisted of oligo(dT)-primed cDNA fragments representing 2 × 106 independent clones (average size of 1.2 kb) unidirectionally cloned into a pACT2 vector. cDNA encoding the cytoplasmic domains of human Sdc1, Sdc2, Sdc3, or Sdc4 was cloned into the GAL4 BD bait vector provided by the manufacturer and screened in the yeast strain AH109 with three reporter gene constructs, ADE2, HIS3, and MEL1, under the control of distinct GAL4 upstream activating sequences and TATA boxes. Yeasts were simultaneously transformed with the bait and prey constructs and plated on SD-leu-trp-his-ade/x-α-gal agar plates. Colonies growing on the selective media and capable of producing α-galactosidase (as evidenced by the blue color) were restreaked onto SD-leu-trp/x-α-gal plates to obtain single colonies. cDNA was retrieved from positive colonies, amplified by transformation of JM109 bacteria, and retransformed into yeast along with the GAL4BD/Sdc constructs. Plasmids resulting in positive yeast colonies on the SD-leu-trp-his-ade/x-α-gal agar plates were then sequenced. The isolated cDNA encoding the C-terminal fragment of the β4 integrin cytoplasmic domain was reinserted into yeast and tested for its interaction with all four syndecan cytoplasmic domains or Sdc1 truncation/deletion mutants.

All syndecan cytoplasmic domain constructs were inserted into the GAL4BD vector using restriction sites engineered into the 5′ ends of the primers used to amplify the syndecan fragments. Deletion mutants were generated by PCR. Deletion of the C2 region of mouse Sdc1 and Sdc4 for expression in pcDNA3 was done by introducing a stop codon before the EFYA sequence using the Quikchange Site Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA).

Cell Culture and Transfection

Human epidermoid carcinoma A431 and normal epidermal HaCat cells were grown in DME medium, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, UT), 4 mm l-glutamine (Sigma), and 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen) at 37 °C and 92.5% air, 7.5% CO2.

Cells were transfected with syndecan constructs in pcDNA3 using Lipofectamine PLUS (Invitrogen) and 10 μg of plasmid in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Stable populations expressing high but equal levels of ectopic syndecan were selected in 1.5 mg/ml G418 (Invitrogen) and sorted by fluorescence-activated cell sorting.

siRNA Treatment and Flow Cytometry

Three siRNAs specific for human Sdc1 were used as described previously (30). To measure cell surface syndecan expression, suspended cells were incubated for 1 h on ice with 1 μg of primary antibody per 3 × 105 cells and then washed and counterstained with Alexa-488-conjugated secondary antibodies and scanned on a FACSCalibur bench top cytometer. Cell scatter and propidium iodide staining profiles were used to gate live, single-cell events for data analysis (30, 31).

Cell Spreading Assays

Nitrocellulose-coated 10-well glass slides (Erie Scientific, Portsmouth, NH) were prepared as described previously (41). Wells were coated at 37 °C for 2 h with mAb 3E1 (3 μg/ml) or LN332 (10 μg/ml), diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (CMF-PBS: 135 mm NaCl, 2.7 mm KCl, 10.2 mm Na2HPO4·7H2O, and 1.75 mm KH2PO4, pH 7.4), and then blocked with serum-free Hepes-buffered DME medium (pH 7.4) containing 1.0% heat-denatured bovine serum albumin (plating medium). Cells were lifted in trypsin (0.25% w/v), washed with DME medium, and regenerated in suspension for 1 h at 37 °C in DME medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum. Cells were then plated in wells (50 μl/well) in the plating medium at a cell density of 105 cells/ml. In some experiments, blocking antibody to β1 integrin (mAb13, 30 μg/ml), β4 integrin (3E1, 30 μg/ml), or heparinase II (0.4 conventional unit/ml) or inhibitors to PI3K (5 μm wortmannin or 60 μm LY294002), Src family kinase (1 μm PP2), or ErbB2 (5 μm AG825) were added to the plating medium and incubated at 37 °C for 40 min before plating cells. Cells were allowed to adhere and spread for 1 h at 37 °C, followed by washing in CMF-PBS and fixation for 12 h in 2% paraformaldehyde at 4 °C. For staining, fixed cells were stained with rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin as described previously (42). Slides were mounted in Immumount (Thermo Shandon), and immunofluorescent images were acquired using a PlanApo ×20 (0.75 numerical aperture) objective and a Photometrics CoolSnap ES camera on a Nikon Eclipse TE2000U microscopy system.

Immunostaining

Cells were plated onto an 8-chamber slide (NUNC, Rochester, NY) in DME medium with 10% serum at the time of passage. After 24 h, cells were rinsed twice in calcium- and magnesium-free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed for 12 h in 2% paraformaldehyde at 4 °C, followed by a PBS rinse and blocked with blocking buffer (PBS containing 10% goat serum) for 2 h at room temperature. For permeabilization, the cells were treated with PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100 for 5 min at room temperature or with cold acetone for 5 min. Cells were incubated with primary antibody (5 μg/ml) diluted in blocking buffer for 1–2 h at room temperature, rinsed four times in PBS, and incubated for 1 h with secondary antibody (2 μg/ml) in blocking buffer, followed by 5-fold rinses in PBS before mounting in Immumount. Cell surface α6β4 integrin in A431 and HaCat cells was stained with mAb 439.9B, and intracellular integrin in A431 cells was stained with GoH3 directed against the α6 subunit; this is specific for α6β4 because these cells do not express α6β1 integrin (43).

Co-immunoprecipitation Assays

Immunoprecipitations were carried in a manner similar to that of Beauvais et al. (30, 31). Cells (8 × 106) were washed once with washing buffer (50 mm Hepes, 50 mm NaCl and 10 mm EDTA, pH 7.4) and then lysed for 20 min on ice in 1% Triton X-100 containing a 1:1000 dilution of protease inhibitor mixture set III (Calbiochem) in washing buffer. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. Cell lysates (1 mg of protein/reaction determined by a BCA assay (Pierce)) were precleared using 50 μg/ml isotype-matched nonspecific IgG and 100 μl of GammaBind-Sepharose. Precleared lysates were then incubated at 4 °C overnight with either 10 μg/ml anti-hSdc1, mSdc1, mSdc4, β4 integrin, or ErbB2 antibodies or mouse IgG or rat IgG as negative control. In experiments where phosphorylated receptors were immunoprecipitated with PY20, anti-β4 integrin, anti-ErbB2, or anti-Fyn antibodies, the cell lysis buffer was supplemented with 2 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 μg/ml pepstatin, 1 mm NaF, and 1 mm Na3VO4, and lysates containing 1 mg of protein were incubated with 10 μg/ml antibody. Immune complexes were precipitated with 50 μl of GammaBind-Sepharose and washed with washing buffer. To help visualize the syndecan core protein(s), soluble material was resuspended in 50 μl of heparinase buffer (50 mm Hepes, 50 mm NaOAc, 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm CaCl2, pH 6.5) with 2.4 × 10−3 IU/ml heparinase II and 0.1 conventional unit/ml chondroitin ABC lyase for 4 h at 37 °C (with fresh enzymes added after 2 h) to remove glycosaminoglycan chains. Samples were resolved by electrophoresis under reduced conditions on a 7.5% Laemmli gel (44), transferred to Immobilon P, and probed with primary antibody followed by an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibody. Visualization of immunoreactive bands was performed using ECF reagent (GE Healthcare) and scanned on a Storm PhosphorImager (GE Healthcare).

Apoptosis Assay

Cells (0.5 × 106/well in a 24-well plate) were induced to undergo apoptosis by incubation with anti-integrin β4 antibody (3E1, 20 μg/ml) for 24 h at 37 °C or by silencing human Sdc1 using siRNA. Treated cells were suspended with trypsin and regenerated for 1 h as described above and then washed with Annexin V binding buffer (10 mm Hepes, 140 mm NaCl, 2.5 mm CaCl2, pH 7.4). 1.0 × 105 cells were suspended in 50 μl of Annexin V binding buffer with 1 μl of Annexin V, Alexa Fluor® 488 conjugate (1 μg/ml), and incubated for 15 min at room temperature and then washed and plated in 10-well glass slides for observation.

Statistics

Student's t test was used to determine the confidence level of the findings.

RESULTS

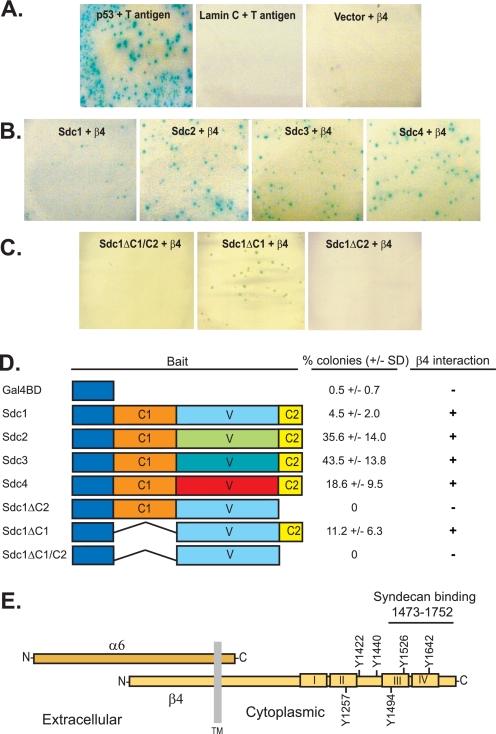

A yeast two-hybrid screen of a human keratinocyte cDNA library was conducted to identify binding partners of the Sdc1 cytoplasmic domain. Yeast AH109 containing three reporter gene constructs, ADE2, HIS3, and MEL1, under the control of distinct GAL4 upstream activating sequences, were used to aid in the elimination of false positives. Conducting the screen using the cytoplasmic domain of Sdc1 in the bait vector isolated a keratinocyte-derived cDNA clone encoding a partial fragment of the β4 integrin cytoplasmic domain, identifying the α6β4 integrin as a potential syndecan binding partner. The isolated integrin cDNA encodes amino acids 1473–1752, which includes nearly all of the third FNIII repeat, all of the fourth repeat, and the C terminus (Fig. 1E).

FIGURE 1.

Interaction of syndecan cytoplasmic C2 region with β4 integrin cytoplasmic domain in a yeast two-hybrid assay. A, yeast strain AH109 was transformed with p53 (Gal4-binding domain bait vector) and T-antigen (Gal4 activation domain prey vector as a positive control) or with Lamin C (bait) and T antigen (prey) or empty vector (bait) and β4 integrin sequence encoding amino acids 1473–1752 (prey) as negative controls. The yeast were spread on SD-leu-trp-his-ade plates containing x-α-gal to visualize positive (blue) colonies. B and C, the β4 fragment (prey) was transformed into yeast with bait vector containing the cytoplasmic domains of either Sdc1, Sdc2, Sdc3, or Sdc4 (B) or Sdc1 lacking its C1 and C2 regions (Sdc1ΔC1/C2), its C1 region (Sdc1ΔC1), or its C2 region (Sdc1ΔC2) (C). D, quantification of data shown in A–C. After 9 days, the number of blue transformants growing on the SD-leu-trp-his-ade plates was counted and divided by the total number of transformants grown on SD-leu-trp plates to calculate the percentage of colonies with positive interactions. All percentages represent the average percentage of three independent transformations. Any strain with a percentage greater than 2% is shown by a plus sign in the β4 interaction column. No positive colonies were obtained for syndecan fragments co-transformed with a plasmid bearing empty prey vector. The syndecan cytoplasmic domains are depicted containing the conserved region 1 (C1), variable region (V), and conserved region 2 (C2) and expressed as a fusion with the Gal-4-binding domain. E, schematic diagram showing the α6β4 integrin and its transmembrane (TM) region, FNIII repeats I–IV, and cytoplasmic tyrosines. The region containing the syndecan binding site (amino acids 1473–1752) identified by yeast two-hybrid analysis is shown.

Next, we examined the specificity of the interaction by expressing cDNAs encoding the cytoplasmic regions of all four syndecan family members in the bait vector together with the β4 fragment expressed as prey. The positive control (p53 and T-antigen) resulted in numerous α-gal-expressing colonies, whereas the negative control (lamin C and T-antigen) or empty bait vector resulted in no colonies (Fig. 1A). However, each of the syndecan cytoplasmic domains bound the prey, with the strongest interaction (based on colony number) observed for Sdc2 and Sdc3 and with weaker interactions for Sdc4 and Sdc1 (Fig. 1, B and D). The conservation of this interaction across the syndecan family suggests the involvement of one of the two conserved regions, C1 or C2, present in the syndecan cytoplasmic domains. To test this, we expressed Sdc1 cytoplasmic domain truncations in which the C2 region, C1 region, or both C1 and C2 regions were deleted. This showed that the interaction depends on the C2 region, which is conserved in the cytoplasmic domains of all four syndecans and has previously been described as a PDZ domain binding motif (45, 46). Although the β4 subunit does not contain a PDZ domain, the interaction between the syndecan and the β4 subunit is nonetheless likely to be direct rather than via an intermediate PDZ-containing protein because PDZ-containing proteins are rare in yeast and have only loose homology with their mammalian counterparts (47).

Based on this finding, we investigated the potential link between syndecans and the α6β4 integrin in mammalian cells using the human squamous carcinoma cell line A431. A431 cells engage LN332, a substrate for the α6β4 integrin, and spread during a 1-h adhesion assay (Fig. 2). Cell attachment is almost completely blocked by an antibody (3E1) that disrupts ligand binding to the α6β4 integrin (Fig. 2, B and E). A blocking antibody to β1 integrins, which would disrupt the activity of α3β1 integrin known to bind LN332, has no effect on either cell adhesion or spreading (Fig. 2E). The cell spreading is disrupted by treating the cells with heparinase (Fig. 2, C and E) or siRNA to Sdc1 (Fig. 2, D and E), treatments that block the ability of Sdc1 to bind LN332 either by disrupting the ability of its heparan sulfate chains to recognize the ligand or by blocking its expression by over 90% (Fig. 2F). Thus, although binding to LN332 by α6β4 integrin does not appear to require the syndecan, cell spreading signals arising from this binding are syndecan-dependent.

FIGURE 2.

Requirement of Sdc1 for A431 cell spreading on LN332. Shown are A431 cells plated on slides coated with 10 μg/ml LN332 without treatment (A), with blocking antibody 3E1 to α6β4 (B), with prior treatment with heparinase II. (C), or with prior treatment with siRNA-specific for human Sdc1 (D). E, quantification of spread cells plated on LN332 and treated with blocking antibody to β1 integrin (mAb13, 30 μg/ml) or control IgG (20 μg/ml), 3E1 blocking antibody (20 μg/ml) to β4 integrin, heparinase II (0.4 conventional unit/ml), or human Sdc1 siRNA (100 nm). Data represent triplicate experiments ± S.D. F, flow cytometry of mock-transfected A431 cells stained with hSdc1-specific antibody B-A38 or control IgG and hSdc1 siRNA-transfected cells stained for hSdc1. *, p < 0.05. Bar, 40 μm.

To focus solely on the α6β4 integrin signaling mechanism, the A431 cells were plated onto substrata coated with anti-β4 integrin antibody 3E1 to engage the integrin alone, which leads to robust cell spreading (Fig. 3A). Prior treatment of the cells with human-specific Sdc1 siRNA, however, blocked the α6β4-dependent spreading of the cells (Fig. 3, B and F). The spreading was rescued by expression of either wild type mouse Sdc1 (mSdc1) (Fig. 3, C and F) or mSdc4 (Fig. 3F) but not by either mSdc1ΔC2 (Fig. 3, D and F) or mSdc4ΔC2 (Fig. 3F), two mutants lacking the cytoplasmic C2 region shown by yeast two-hybrid analysis to be required for the syndecans to engage the β4 cytoplasmic domain. Each of these constructs was expressed at similar levels at the cell surface (Fig. 3E), suggesting that the C2 region of the syndecan cytoplasmic domain is required for the α6β4 activity.

FIGURE 3.

Syndecan-dependent spreading of A431 cells on β4 antibody 3E1. A431 cells were plated on 3 μg/ml 3E1 for 1 h at 37 °C and then stained with rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin to visualize the spread lamellipodia. Shown are parental cells (A), parental cells pretreated with hSdc1-specific siRNA (B), siRNA-treated cells expressing mSdc1 (C), and siRNA-treated cells expressing mSdc1ΔC2 mutant (D). E, the cell surface expression of mSdc1 or mSdc1ΔC2 (mAb 281.2) and mSdc4 or mSdc4ΔC2 (mAb KY 8.2) is compared with control rat IgG by flow cytometry. F, quantification of spread cells with or without pretreatment with hSdc1-specific siRNA and stable expression of mouse Sdc1 or Sdc4 constructs. Data represent triplicate experiments ± S.D. *, p < 0.05. Bar, 40 μm.

The complete dependence of this mechanism on Sdc1 is surprising because (i) epithelial cells typically express endogenous Sdc4 that is also capable of interacting with the integrin (cf. Fig. 1), and (ii) mSdc4 expressed in the cells can indeed rescue the mechanism when hSdc1 expression is silenced (cf. Fig. 3F). To test whether this mechanism is operative in other cells that express Sdc1 and Sdc4, we examined the spreading of HaCat human keratinocytes when the α6β4 integrin is engaged by 3E1. As seen with the A431 cells, the HaCat cells also spread, and this spreading was completely blocked by silencing of the expression of Sdc1 (Fig. 4A). However, we also found that both Sdc1 and Sdc4 co-immunoprecipitated with the β4 integrin from either A431 cells or from HaCat human keratinocytes (Fig. 4B). In fact, Sdc4 appeared to bind the integrin more quantitatively than Sdc1, especially in the A431 cells. But staining the cells to localize these receptors shows that Sdc4 is almost exclusively intracellular. Human Sdc1 was expressed on the cell surface of HaCat (Fig. 4C) and A431 cells (Fig. 4D), where it is localized with the α6β4 integrin (Fig. 4D). Sdc4 showed no cell surface staining (Fig. 4, C and D) for either cell type, whereas it could be observed if the cells were permeabilized before staining. As predicted by the co-immunoprecipitation of Sdc4 with the majority of the α6β4 integrin, staining for the integrin in permeablized A431 cells shows that it co-localizes with Sdc4 in vesicular structures in the perinuclear area. This internal localization is likely to be the reason that Sdc4 does not participate in α6β4-mediated adhesion, at least when these cells are grown in serum culture.

FIGURE 4.

Interaction of Sdc1 and Sdc4 with α6β4 integrin in HaCat and A431 cells. A, HaCat cells treated with or without hSdc1 siRNA are plated on 3 μg/ml 3E1 as described in the legend to Fig. 3. B, hSdc1, hSdc4, or β4 integrin subunit was immunoprecipitated from A431 or HaCat cells and probed for precipitation of either hSdc1 or hSdc4. C, staining of HaCat cells for expression of hSdc1 (mAb B-A38), hSdc4 (mAb 150.9), or hSdc4 after permeabilization (hSdc4 perm). D, staining of A431 cells for hSdc1, hSdc4 (with and without permeabilization), and α6β4 integrin (with (mAb GoH3) and without (mAb 439–9B) permeablization). Mouse IgG (mIgG) and rat IgG (rIgG) staining controls are shown. Bar, 20 μm. IP, immunoprecipitation; IB, immunoblot.

Prior work has shown that the β4 integrin cytoplasmic domain is a target for tyrosine phosphorylation that leads to PI3K-dependent cell invasion and cell survival (16–20, 24, 48). The EGF receptor kinase family member ErbB2 is known to associate with the β4 subunit and, when activated by integrin clustering, causes β4 phosphorylation via activation of SFKs, most likely Fyn (10). We therefore used the A431 cells to question whether the integrin- and syndecan-dependent spreading that we observe depends on this pathway. Blockade of PI3K using either LY294002 or wortmannin blocked the spreading of the cells, as did blockade of SFKs with PP2 or inhibition of ErbB2 with the tyrphostin AG825 (Fig. 5). Note that the concentration of AG825 used was 5 μm, which was chosen to block ErbB2 (IC50 = 0.35 μm) rather than EGFR (IC50 = 19 μm) because EGFR is also known to associate with the α6β4 integrin.

FIGURE 5.

Inhibition of α6β4-mediated spreading by PI3K, SFK, and ErbB2 inhibitors. A431 cells were plated for 1 h on substrata coated with 3 μg/ml mAb 3E1 to engage the α6β4 integrin in the presence of PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (60 μm) or wortmannin (5 μm), SFK inhibitor PP2 (1 μm), or ErbB2 tyrphostin inhibitor AG825 (5 μm). Data are shown as percentage of spread cells compared with control in triplicate experiments ± S.D. *, p < 0.05.

ErbB2, Fyn, and α6β4 integrin are known to immunoprecipitate as a complex, and this complex includes PI3K when the integrin is phosphorylated on tyrosine (10). To test whether Sdc1 also immunoprecipitates as a member of this complex, either Sdc1, α6β4, ErbB2, Fyn, or PI3K was precipitated from A431 cells, and the immunoprecipitates were probed for the presence of other members of the complex. The integrin, ErbB2, Fyn, and PI3K were all found to immunoprecipitate with hSdc1 (Fig. 6A), and Sdc1 co-precipitated when each of these proteins was immunoprecipitated. In keeping with the finding that Sdc1 was bound only to a fraction of the integrin (cf. Fig. 4B), we see that it is just a fraction of these proteins (10–20%) in the cell that are assembled together into this signaling complex. To examine the specificity of this interaction, A431 cells overexpressing mSdc1 or mSdc4 or expressing the mSdc1ΔC2 mutant incapable of α6β4 binding were subjected to immunoprecipitation (Fig. 6B). Staining for mouse Sdc4 shows that its overexpression leads to its appearance on the cell surface (data not shown). In addition to the hSdc1 expressed by the cells, the wild-type mSdc1 and mSdc4 engaged the β4 integrin and ErbB2, confirming that they are both assimilated into this signaling complex. However, the mSdc1ΔC2 mutant failed to co-precipitate with the integrin or ErbB2.

FIGURE 6.

Sdc1 immunoprecipitates in a complex containing α6β4 integrin, ErbB2, Fyn, and PI3K. A, A431 cells cultured in serum were extracted and subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) using mAb B-A38 to hSdc1, 3E1 to β4 integrin subunit, Ab-15 to ErbB2, FYN15 to Fyn, or AB6 to the p85α subunit of PI3K. The immunoprecipitates were analyzed on Western blots by probing with these antibodies. *, note that 4-fold less of the Fyn immunoprecipitate was analyzed compared with the other samples. B, A431 cells transfected with mSdc1, mSdc1ΔC2, or mSdc4 were similarly analyzed by immunoprecipitation of hSdc1 with B-A38, mouse Sdc1, or Sdc1ΔC2 with mAb 281.2 or mSdc4 with mAb KY 8.2. The blots were then probed with the same antibodies to confirm syndecan precipitation and for co-precipitation of α6β4 using mAb 3E1 or ErbB2 using Ab-15.

The blockade of cell spreading when Sdc1 expression is silenced and the failure of the mSdc1ΔC2 mutant to rescue this activity suggest that syndecan interaction with the integrin is necessary to establish the signaling cascade that proceeds from ErbB2 to integrin phosphorylation and activation of the downstream targets PI3K and Akt. We initially confirmed that the β4 integrin becomes phosphorylated when engaged with ligand by incubating suspended A431 cells with soluble LN332; this caused integrin tyrosine phosphorylation, whereas no phosphorylation was observed with LN111 (Fig. 7A). This was also observed when the suspended cells are treated with the β4-specific antibody 3E1 together with a second clustering antibody, mimicking integrin clustering that occurs upon matrix engagement (Fig. 7B). Integrin phosphorylation was blocked by the addition of the ErbB2 inhibitor AG825, which also caused reduced phosphorylation of Fyn. Inhibition of Fyn, using the SFK inhibitor PP2, also blocked integrin phosphorylation but did not affect the activation of its upstream effector ErbB2. PP2 also blocked the phosphorylation of Akt, as did the PI3K inhibitors wortmannin and PY294002 (Fig. 7C), suggesting that ErbB2, which was activated when the integrin was clustered, activated Fyn to phosphorylate the β4 cytoplasmic domain and cause the recruitment and activation of PI3K and its downstream target Akt.

FIGURE 7.

Sdc1 is necessary for Fyn-mediated phosphorylation of α6β4 integrin. A, suspended A431 cells are treated with PBS alone or PBS containing 1 μg/ml LN111 or LN332. Cell lysates were split between two Western blots stained for β4 subunit with mAb 3E1 and phosphotyrosine with mAb PY20. B and C, suspended A431 cells are treated with or without mAb 3E1 and an anti-mouse IgG secondary (2°) antibody to induce clustering of α6β4 integrin in the presence of 5 μm AG825 to inhibit ErbB2 or 1 μm PP2 to inhibit SFK or 5 μm wortmannin or 40 μm LY294002 to inhibit PI3K. B, ErbB2 was precipitated with mAb Ab-15, Fyn with FYN15, and β4 with 3E1, and the immunoprecipitates were probed using these same antibodies, using PY20 to detect phosphotyrosine, and using anti-phospho-Src family (Tyr-416) mAb to detect pY416 specific for Fyn activation. C, lysates were probed on Western blots for Akt and for phosphorylation of the activation-specific Ser-473 in Akt using anti-phospho-AKT (Ser-473) mAb. D, A431 cells or A431 cells expressing mSdc1 were pretreated with Lipofectamine with or without hSdc1-specific siRNA and then suspended and treated with or without 3E1 plus anti-mouse IgG (10 min) to induce β4 clustering. ErbB2, Fyn, and β4 integrin subunit were immunoprecipitated, and phosphorylation of ErbB2 and β4 was determined by blotting with PY20, phosphorylation of Fyn by blotting with mAb anti-phospho-Src family (Tyr-416), and co-precipitation of PI3K with β4 by blotting with mAb AB6. Note that the Fyn blot was stripped and reprobed for the double staining. IP, immunoprecipitation.

To determine the point in the cascade where the syndecan receptor has a role, we tested the phosphorylation of each of the intermediates when Sdc1 expression was silenced. Phosphorylation of the integrin was blocked when hSdc1 expression was silenced (Fig. 7D) but was rescued by mSdc1 in the siRNA-treated cells. Thus, Sdc1 appears to exert its activity either at this step or upstream of this point. However, the phosphorylation of ErbB2 and Fyn, the upstream kinases in this signaling cascade, in response to α6β4 ligation was not disrupted by silencing Sdc1, whereas the recruitment of the p85 regulatory subunit of PI3K and its immunoprecipitation with the β4 subunit were blocked. Thus, Sdc1 appears to have a role in the Fyn-mediated phosphorylation of the α6β4 integrin.

Activation of α6β4 integrin signaling in tumor cells deficient in p53, such as the A431 cells, provides protection from apoptosis by activating Akt (3, 22, 24). We found that silencing endogenous Sdc1 expression in the A431 cells caused an 8-fold increase in apoptosis (to nearly 50% of the cells) after 55 h, as assessed by fluorescent Annexin V staining (Fig. 8, A and B). Protection from apoptosis was rescued by expressing mSdc1 in the siRNA-treated cells but could not be rescued by expressing the mSdc1ΔC2 mutant (Fig. 8B). This effect is consistent with the role of syndecan in α6β4 integrin signaling and suggests that the cells cultured in serum are utilizing Sdc1 to activate signaling by the integrin.

FIGURE 8.

Sdc1-dependent signaling by α6β4 prevents apoptosis in A431 cells. A, A431 cells were grown in serum-containing medium for 5, 30, and 55 h following pretreatment with Lipofectamine with or without hSdc1-specific siRNA. The number of apoptotic cells was determined by staining with Alexa488-conjugated Annexin V and expressed as a percentage of the total cells. B, A431 cells expressing either empty vector or vector encoding mSdc1 or mSdc1ΔC2 mutant were treated with or without siRNA and then plated for 55 h in serum-containing medium followed by staining with Annexin V. C, A431 cells were pretreated with Lipofectamine alone or Lipofectamine with hSdc1-specific siRNA and then were plated in serum-containing medium for 24 h in 20 μg/ml mAb 3E1 to block ligand binding to the α6β4 integrin or treated with mAb 3E1 plus anti-mouse IgG to cluster the α6β4 integrin to rescue the block to integrin signaling. Cells were suspended and stained with Alexa488-conjugated Annexin V. D, quantification of apoptosis monitored by Annexin V staining under the conditions defined in C. Data are from triplicate experiments ± S.D. *, p < 0.05.

To confirm that the signal was indeed from the α6β4 integrin, A431 cells were cultured for 20 h in the presence of serum but also in the presence of the β4-specific antibody 3E1 to block ligand engagement by the integrin. This treatment blocked the anti-apoptotic signal, whereas a control IgG was without effect (Fig. 8, C and D). Second, combining the 3E1 treatment with a secondary antibody to cluster the 3E1-integrin complex and thus activate rather than inhibit the integrin reversed the effect of the antibody and provided protection against apoptosis. Last, silencing the expression of the endogenous Sdc1 blocked the protective signal provided by the combined 3E1 and clustering antibody treatment (Fig. 8D).

DISCUSSION

This work describes for the first time an essential role of syndecan family members in the activation of α6β4 integrin in epithelial cells. Unlike more traditional integrins that have short cytoplasmic domains and rely on inside-out signaling for activation (49–51), signaling by the α6β4 integrin in migrating keratinocytes and tumor cells is largely driven in response to phosphorylation of its cytoplasmic domain (reviewed in Refs. 1 and 3).

It is now well accepted that the transition of the α6β4 integrin from hemidesmosomes to the leading edge of carcinomas is caused by its tyrosine and serine phosphorylation in response to EGFR, ErbB2, and/or c-Met (7, 9, 14). The β4 tail becomes phosphorylated on several important tyrosines, especially Tyr-1257, Tyr-1440, Tyr-1494, and Tyr-1526 (cf. Fig. 1), that are docking sites for Shc and IRS1/2 (8, 10, 14, 16, 17, 20) and that recruit PI3K and other signaling effectors (10, 16, 17). These docking sites are present largely in the distal third of the β4 cytoplasmic domain, a region that has been termed the β4 “signaling domain” (10). It is important to note that this is also the region to which the syndecans bind (cf. Fig. 1). This region is not essential for hemidesmosome formation. Mice with a targeted replacement of the wild type β4 gene by a mutant construct lacking this signaling domain (β41355T) and therefore lacking the syndecan binding site show normal hemidesmosome formation. However, they display impaired wound healing (probably a failure of α6β4 to carry out its signaling role in response to EGF in keratinocytes) and fail to form invasive tumors when crossed with Neu/Neu mice overexpressing the oncogenic form of ErbB2 (10). Thus, the syndecans are implicated in this signaling role rather than in hemidesmosome formation.

In the A431 carcinoma cells used here, tyrosine phosphorylation of the β4 subunit occurs upon integrin clustering when LN332 or β4-specific antibody is engaged. This phosphorylation of the integrin also requires its direct association with Sdc1 because silencing of hSdc1 expression blocks the phosphorylation. The signal is rescued by mSdc1 or mSdc4 but not if they lack the C2 region shown by yeast two-hybrid analysis to mediate the binding. Surprisingly, Sdc1, which is the most abundant syndecan on epithelial cells that express the α6β4 integrin, showed the weakest interaction in the yeast two-hybrid assay. This was also observed to some extent in the co-immunoprecipitation assays from A431 and HaCat cells. However, this may also reflect the folding and accessibility of this short domain when expressed as a fusion protein with the Gal4-BD in yeast.

The specificity of the C2 region of the syndecan cytoplasmic domain defines a new role for this site. This region, composed of four amino acids, EFYA, has previously been shown to bind the PDZ domains of several scaffolding proteins, notably CASK (52, 53) and syntenin (45, 46). However, there is no recognizable PDZ domain within the β4 tail. Thus this is a novel, although probably analogous, interaction. An alternative possibility is that the interaction between the syndecan and the integrin is not direct but is mediated by a PDZ-domain protein, such as syntenin. This possibility would seemingly be supported by recent work showing that Sdc1 binding to syntenin is promoted upon epithelial cells binding to the LG4,5 domain of LN332 (39). However, silencing syntenin expression in the A431 cells with RNA interference has no effect on the integrin signaling mechanism.3 Second, and perhaps most importantly, the interaction was initially discovered using yeast two-hybrid analysis, and yeasts fail to express syntenin or other mammalian type PDZ proteins (47). Thus, it is likely that yeast would fail to reproduce this interaction unless it was direct.

Our immunoprecipitation studies show that only limited fractions of Sdc1, ErbB2, Fyn, and α6β4 integrin assemble into a complex with one another. These in turn recruit PI3K and Akt when the integrin is activated. This provides signals necessary for cell spreading on integrin ligands as well as an anti-apoptotic signal in response to serum. Our data suggest either that the syndecan has a role in activating the tyrosine kinase responsible for the phosphorylation or in positioning the β4 cytoplasmic domain such that it becomes a substrate for the kinase (see the speculative model in Fig. 9). Our inhibitor studies indicate that ErbB2 activation is upstream of Fyn, which is upstream of β4 phosphorylation. This confirms similar findings by others (10). Phosphorylation of ErbB2, Fyn, and β4 is blocked by the ErbB2-specific inhibitor AG825; at higher concentrations, this inhibitor can also inhibit the EGFR, which is highly expressed by the A431 cells and has also been shown to target the integrin. But the concentration of AG825 used here is ∼15-fold greater than the IC50 for ErbB2 and ∼4-fold lower than the IC50 for the EGFR; thus, it seems unlikely that EGFR has been blocked. The ErbB2 receptor tyrosine kinase is undoubtedly activated by undergoing trans- or autophosphorylation when the integrin-Sdc1-ErbB2 complex is clustered. Although ErbB2 is an orphan receptor that responds to EGF family growth factors only by forming a heterodimer with another EGFR family member (54), often EGFR itself, we envision that activation of ErbB2 in response to matrix engagement of α6β4 integrin or Sdc1 causes autophosphorylation of ErbB2 within the clustered complexes. However, EGFR could adopt a similar role or even function in a heterodimer with ErbB2.

FIGURE 9.

Speculative model of syndecan and integrin interaction. The α6β4 integrin is shown assembled in a complex with ErbB2, Fyn, and Sdc1. Note that although Sdc1 predominates in this mechanism in the A431 cells, other syndecan family members may function in this role in other cells. Sdc1 binds the β4 subunit within the distal portion of its cytoplasmic domain containing the third and fourth FNIII domains and the C terminus. Clustering of these complexes (ErbB2 from a second complex is shown after clustering) causes transphosphorylation of ErbB2 (step 1), docking and autophosphorylation of Fyn (step 2), and Fyn-dependent phosphorylation of the β4 cytoplasmic domain (step 3). The phosphorylated β4 cytoplasmic domain recruits signaling proteins that lead to the activation of PI3K, cell adhesion and spreading, and resistance to apoptosis.

Because it has been shown that Fyn is activated downstream of ErbB2 (10), we chose to examine the role of this SFK in this activation mechanism. We confirm that clustering the integrin causes autophosphorylation of Fyn in its activation loop and that this is disrupted by inhibition of ErbB2. Furthermore, we confirm that inhibition of Fyn blocks β4 phosphorylation but has little or no effect on the upstream activation of ErbB2. An attractive but unlikely possibility for a role of Sdc1 in this activation is that it is responsible for the incorporation of ErbB2 and/or Fyn into the complex. Sdc1 has also been shown to reside in specialized lipid domains (55). However, silencing Sdc1 expression does not block activation of these kinases when the integrin is clustered, and immunoprecipitation of either ErbB2 or Fyn with the α6β4 integrin does not depend on the syndecan. The palmitoylation of α6β4 and its subsequent recruitment into lipid rafts is reported to be necessary for it to associate with and be activated by SFKs (56). Although it remains a possibility that this palmitoylation and raft localization also favor its association with the syndecan, our preliminary data show that Sdc1 associates with α6β4 integrin present in Triton-soluble buoyant fractions (rafts) on sucrose gradients but also with the sedimenting (non-raft) fraction of integrin.3 Thus, it seems likely that the cytoplasmic domain interaction that we describe, rather than co-localization into lipid rafts, is the primary means of association.

The small fraction of integrin that associates with Sdc1 seems due mostly to Sdc4 competing with Sdc1 for integrin binding and sequestering the integrin in intracellular vesicles. Although this intracellular localization has not been described previously for Sdc4, there are scattered reports that the α6β4 integrin is sequestered in recycling compartments in other cells (43, 57, 58). It will be of interest to see if this sorting reveals a behavior of the integrin that is dependent on which syndecan it binds.

An explanation that we favor for the role of cell surface syndecan in α6β4 integrin signaling arises from a consideration of the topology of these receptors. The syndecan cytoplasmic domain is very short (∼30 amino acids) but interacts with the distal third of the β4 cytoplasmic domain, a separation of at least 700 amino acids (over 20 times the length of the syndecan cytoplasmic domain if the domains are extended). Clearly, the β4 cytoplasmic domain must be folded back to the underside of the plasma membrane to engage with Sdc1. Modeling of the β4 cytoplasmic domain suggests that the distal region containing the third and fourth FNIII repeats is indeed folded back on itself (15). As speculated previously by others (14), this folding may bring the distal part of the domain closer to the membrane, where either it or effectors, such as Shc engaged to its phosphorylated tyrosines, can be phosphorylated by membrane-associated SFKs and where Grb2 bound to activated Shc can activate membrane-bound Ras. However, even this folding would appear to be insufficient to engage these membrane-anchored proteins. Thus, the primary role of the syndecan may be to bring the β4 cytoplasmic domain containing the distal pair of FNIII repeats directly to the underside of the plasma membrane, where it is easily targeted by SFKs and thus initiates this signaling cascade (Fig. 9). If such a model is correct, it will be interesting to test whether β4 phosphorylation downstream of EGFR or c-Met is also dependent on a syndecan interaction.

LN332 is composed of α3, β3, and γ2 chains (59) and has binding sites for multiple receptors. Its main receptors are the integrins α3β1, α6β1, and α6β4 and the syndecans (2, 60). However, blockade of the β1 integrins did not block the Sdc1-mediated signaling mechanism described here, indicating that at least on the A431 cells, the signal is syndecan- and α6β4 integrin-dependent. The literature describing the role of syndecan binding to LN332 is complex. This derives in part from the fact that there are at least two heparin-binding domains in LN332 (in the LG4,5 domain of the α3 chain and domain V in the short arm of the γ2 chain (γ2sa) and the fact that these domains are processed such that different LN332 isoforms have one, two, or none of these domains (60). This can potentially lead to differing effects of LN332 on cells, depending on the state of processing of the laminin in the matrix and the cell type. The LG4,5 domain is typically cleaved and degraded immediately after LN332 secretion. However, its expression persists in keratinocytes migrating at the edge of epidermal wounds (61) and in a high percentage of squamous cell carcinomas (62), suggesting a possible connection between its expression and cell invasion, potentially by the Sdc1-dependent activation of α6β4 integrin described here. Indeed, squamous carcinoma cells engineered to express the LG4,5 domain showed increased tumorigenesis in vivo (62).

Surprisingly, the heparin-binding site in the γ2sa chain of LN332 also binds Sdc1 but has an opposite biological effect (40, 63). This site is removed from some or all of the deposited LN332 in humans by mammalian Tolloid metalloproteinases (64). The processed chain causes increased cell motility in vitro, whereas the unprocessed chain that retains Sdc1 binding or processed chain together with the readdition of the cleaved fragment reduces motility and causes loss of α6β4 phosphorylation. This effect appears dependent on Sdc1 and would seemingly indicate that the γ2sa competitively blocks the Sdc1-dependent phosphorylation of α6β4 that we describe here. Our description of the Sdc1-α6β4 integrin interaction may help to unravel these complexities.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01-CA109010 (to A. C. R.).

H. Wang and A. C. Rapraeger, unpublished data.

- LN332

- laminin 332

- LN111

- laminin 111

- EGF

- epidermal growth factor

- FNIII

- fibronectin type III

- hSdc and mSdc

- human and mouse syndecan, respectively

- PI3K

- phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- SFK

- Src family kinase

- EGFR

- epidermal growth factor receptor

- IRS

- insulin receptor substrate

- Ab

- antibody

- mAb

- monoclonal antibody

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wilhelmsen K., Litjens S. H., Sonnenberg A. (2006) Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 2877–2886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marinkovich M. P. (2007) Nat. Rev. Cancer 7, 370–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mercurio A. M., Rabinovitz I. (2001) Semin. Cancer Biol. 11, 129–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aumailley M., Rousselle P. (1999) Matrix Biol. 18, 19–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rousselle P., Keene D. R., Ruggiero F., Champliaud M. F., Rest M., Burgeson R. E. (1997) J. Cell Biol. 138, 719–728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santoro M. M., Gaudino G., Marchisio P. C. (2003) Dev. Cell 5, 257–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falcioni R., Antonini A., Nisticò P., Di Stefano S., Crescenzi M., Natali P. G., Sacchi A. (1997) Exp. Cell Res. 236, 76–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mariotti A., Kedeshian P. A., Dans M., Curatola A. M., Gagnoux-Palacios L., Giancotti F. G. (2001) J. Cell Biol. 155, 447–458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trusolino L., Bertotti A., Comoglio P. M. (2001) Cell 107, 643–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo W., Pylayeva Y., Pepe A., Yoshioka T., Muller W. J., Inghirami G., Giancotti F. G. (2006) Cell 126, 489–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rabinovitz I., Tsomo L., Mercurio A. M. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 4351–4360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilhelmsen K., Litjens S. H., Kuikman I., Margadant C., van Rheenen J., Sonnenberg A. (2007) Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 3512–3522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Margadant C., Frijns E., Wilhelmsen K., Sonnenberg A. (2008) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 20, 589–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dans M., Gagnoux-Palacios L., Blaikie P., Klein S., Mariotti A., Giancotti F. G. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 1494–1502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schaapveld R. Q., Borradori L., Geerts D., van Leusden M. R., Kuikman I., Nievers M. G., Niessen C. M., Steenbergen R. D., Snijders P. J., Sonnenberg A. (1998) J. Cell Biol. 142, 271–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mainiero F., Murgia C., Wary K. K., Curatola A. M., Pepe A., Blumemberg M., Westwick J. K., Der C. J., Giancotti F. G. (1997) EMBO J. 16, 2365–2375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shaw L. M., Rabinovitz I., Wang H. H., Toker A., Mercurio A. M. (1997) Cell 91, 949–960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bertotti A., Comoglio P. M., Trusolino L. (2006) J. Cell Biol. 175, 993–1003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Merdek K. D., Yang X., Taglienti C. A., Shaw L. M., Mercurio A. M. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 30322–30330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shaw L. M. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 5082–5093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dutta U., Shaw L. M. (2008) Cancer Res. 68, 8779–8787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bachelder R. E., Ribick M. J., Marchetti A., Falcioni R., Soddu S., Davis K. R., Mercurio A. M. (1999) J. Cell Biol. 147, 1063–1072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clarke A. S., Lotz M. M., Chao C., Mercurio A. M. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 22673–22676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lipscomb E. A., Simpson K. J., Lyle S. R., Ring J. E., Dugan A. S., Mercurio A. M. (2005) Cancer Res. 65, 10970–10976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raymond K., Kreft M., Song J. Y., Janssen H., Sonnenberg A. (2007) Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 4210–4221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hintermann E., Yang N., O'Sullivan D., Higgins J. M., Quaranta V. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 8004–8015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rapraeger A., Jalkanen M., Bernfield M. (1986) J. Cell Biol. 103, 2683–2696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bernfield M., Kokenyesi R., Kato M., Hinkes M. T., Spring J., Gallo R. L., Lose E. J. (1992) Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 8, 365–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beauvais D. M., Rapraeger A. C. (2004) Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beauvais D. M., Burbach B. J., Rapraeger A. C. (2004) J. Cell Biol. 167, 171–181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beauvais D. M., Ell B. J., McWhorter A. R., Rapraeger A. C. (2009) J. Exp. Med. 206, 691–705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McQuade K. J., Beauvais D. M., Burbach B. J., Rapraeger A. C. (2006) J. Cell Sci. 119, 2445–2456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whiteford J. R., Behrends V., Kirby H., Kusche-Gullberg M., Muramatsu T., Couchman J. R. (2007) Exp. Cell Res. 313, 3902–3913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woods A., Longley R. L., Tumova S., Couchman J. R. (2000) Arch. Biochem. Biophys 374, 66–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bass M. D., Morgan M. R., Humphries M. J. (2009) Sci. Signal 2, pe18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okamoto O., Bachy S., Odenthal U., Bernaud J., Rigal D., Lortat-Jacob H., Smyth N., Rousselle P. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 44168–44177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Utani A., Nomizu M., Matsuura H., Kato K., Kobayashi T., Takeda U., Aota S., Nielsen P. K., Shinkai H. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 28779–28788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bachy S., Letourneur F., Rousselle P. (2008) J. Cell. Physiol. 214, 238–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sulka B., Lortat-Jacob H., Terreux R., Letourneur F., Rousselle P. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 10659–10671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ogawa T., Tsubota Y., Hashimoto J., Kariya Y., Miyazaki K. (2007) Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 1621–1633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lebakken C. S., Rapraeger A. C. (1996) J. Cell Biol. 132, 1209–1221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lebakken C. S., McQuade K. J., Rapraeger A. C. (2000) Exp. Cell Res. 259, 315–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bretscher M. S. (1992) EMBO J. 11, 405–410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laemmli U. K. (1970) Nature 227, 680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zimmermann P., Tomatis D., Rosas M., Grootjans J., Leenaerts I., Degeest G., Reekmans G., Coomans C., David G. (2001) Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 339–350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grootjans J. J., Zimmermann P., Reekmans G., Smets A., Degeest G., Dürr J., David G. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 13683–13688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ponting C. P., Phillips C., Davies K. E., Blake D. J. (1997) BioEssays 19, 469–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gambaletta D., Marchetti A., Benedetti L., Mercurio A. M., Sacchi A., Falcioni R. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 10604–10610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Humphries M. J. (1996) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 8, 632–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tadokoro S., Shattil S. J., Eto K., Tai V., Liddington R. C., de Pereda J. M., Ginsberg M. H., Calderwood D. A. (2003) Science 302, 103–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takagi J., Petre B. M., Walz T., Springer T. A. (2002) Cell 110, 599–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cohen A. R., Woods D. F., Marfatia S. M., Walther Z., Chishti A. H., Anderson J. M., Wood D. F. (1998) J. Cell Biol. 142, 129–138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hsueh Y. P., Yang F. C., Kharazia V., Naisbitt S., Cohen A. R., Weinberg R. J., Sheng M. (1998) J. Cell Biol. 142, 139–151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Graus-Porta D., Beerli R. R., Daly J. M., Hynes N. E. (1997) EMBO J. 16, 1647–1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McQuade K. J., Rapraeger A. C. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 46607–46615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gagnoux-Palacios L., Dans M., van't Hof W., Mariotti A., Pepe A., Meneguzzi G., Resh M. D., Giancotti F. G. (2003) J. Cell Biol. 162, 1189–1196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gaietta G., Redelmeier T. E., Jackson M. R., Tamura R. N., Quaranta V. (1994) J. Cell Sci. 107, 3339–3349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yoon S. O., Shin S., Mercurio A. M. (2005) Cancer Res. 65, 2761–2769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aumailley M., Bruckner-Tuderman L., Carter W. G., Deutzmann R., Edgar D., Ekblom P., Engel J., Engvall E., Hohenester E., Jones J. C., Kleinman H. K., Marinkovich M. P., Martin G. R., Mayer U., Meneguzzi G., Miner J. H., Miyazaki K., Patarroyo M., Paulsson M., Quaranta V., Sanes J. R., Sasaki T., Sekiguchi K., Sorokin L. M., Talts J. F., Tryggvason K., Uitto J., Virtanen I., von der Mark K., Wewer U. M., Yamada Y., Yurchenco P. D. (2005) Matrix Biol. 24, 326–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Miyazaki K. (2006) Cancer Sci. 97, 91–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sigle R. O., Gil S. G., Bhattacharya M., Ryan M. C., Yang T. M., Brown T. A., Boutaud A., Miyashita Y., Olerud J., Carter W. G. (2004) J. Cell Sci. 117, 4481–4494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tran M., Rousselle P., Nokelainen P., Tallapragada S., Nguyen N. T., Fincher E. F., Marinkovich M. P. (2008) Cancer Res. 68, 2885–2894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ogawa T., Tsubota Y., Maeda M., Kariya Y., Miyazaki K. (2004) J. Cell. Biochem. 92, 701–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Veitch D. P., Nokelainen P., McGowan K. A., Nguyen T. T., Nguyen N. E., Stephenson R., Pappano W. N., Keene D. R., Spong S. M., Greenspan D. S., Findell P. R., Marinkovich M. P. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 15661–15668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jalkanen M., Nguyen H., Rapraeger A., Kurn N., Bernfield M. (1985) J. Cell Biol. 101, 976–984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yamashita Y., Oritani K., Miyoshi E. K., Wall R., Bernfield M., Kincade P. W. (1999) J. Immunol. 162, 5940–5948 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]