Abstract

Alkyltransferase-like proteins (ATLs) are a novel class of DNA repair proteins related to O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferases (AGTs) that tightly bind alkylated DNA and shunt the damaged DNA into the nucleotide excision repair pathway. Here, we present the first structure of a bacterial ATL, from Vibrio parahaemolyticus (vpAtl). We demonstrate that vpAtl adopts an AGT-like fold and that the protein is capable of tightly binding to O6-methylguanine-containing DNA and disrupting its repair by human AGT, a hallmark of ATLs. Mutation of highly conserved residues Tyr23 and Arg37 demonstrate their critical roles in a conserved mechanism of ATL binding to alkylated DNA. NMR relaxation data reveal a role for conformational plasticity in the guanine-lesion recognition cavity. Our results provide further evidence for the conserved role of ATLs in this primordial mechanism of DNA repair.

Keywords: DNA-binding Protein, DNA Repair, DNA Nucleotide Excision Repair, NMR, Protein Structure, Alkyltransferase-like Protein

Introduction

O6-Alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferases (AGTs)3 are a large family (Pfam, PF01035; EC 2.1.1.63) of alkyl damage-response proteins that reverse endogenous and exogenous alkylation at the O6 position of guanines, cytotoxic lesions that otherwise cause G:C to A:T mutations in DNA (1). Human AGT, also called MGMT, interferes with alkylating chemotherapies making it a target for anticancer drug design (1, 2). AGTs are ubiquitous suicide enzymes that mediate the irreversible transfer of the alkyl group to a reactive cysteine within a highly conserved PCHRV active site sequence motif by a direct reversal mechanism, featuring sequence-independent minor-groove binding to a helix-turn-helix motif and flipping of the damaged nucleotide (3, 4).

Alkyltransferase-like proteins (ATLs), thus far identified in prokaryotes and lower eukaryotes, constitute a new subclass with sequence similarity to AGTs but lacking the critical cysteine alkyl receptor, which is most often replaced by a tryptophan (5, 6). ATLs tightly bind a wide range of O6-alkylguanine adducts and block the repair of O6-mG by human AGT but exhibit no alkyltransferase, glycosylase, or endonuclease activities (7–9). The recent first structural study of an ATL (10), from the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe (spAtl1) which lacks an AGT, provides strong evidence for a novel mechanism of DNA repair in which an ATL binds alkylated DNA in a manner analogous to AGTs, and the resulting nonenzymatic ATL·DNA complex triggers the NER pathway (10, 11).

Here, we present the solution NMR structure of the 100-residue ATL from Vibrio parahaemolyticus AQ3810 (Swiss-Prot entry A6B4U8_VIBPA; Northeast Structural Genomics code, VpR247; hereafter referred to as vpAtl), whose structure was solved as part of the Northeast Structural Genomics consortium of the National Institutes of Health, NIGMS, Protein Structure Initiative. The vpAtl protein shares 47% sequence identity with spAtl1 and features a PWFRV active site sequence motif (Fig. 1A). We demonstrate that the structure of vpAtl is highly analogous to the AGT fold and that this bacterial protein is capable of tightly binding to O6-mG-containing DNA and disrupting its repair by human AGT. Site-directed mutagenesis experiments demonstrate the importance of highly conserved residues Tyr23 and Arg37 for binding to alkylated DNA. In addition, the NMR data further suggest that the O6-mG recognition cavity of bacterial ATLs exhibits some conformational flexibility, which may confer broader specificity for various alkyl guanine lesions. To our knowledge, this work represents the first structural characterization of a bacterial ATL.

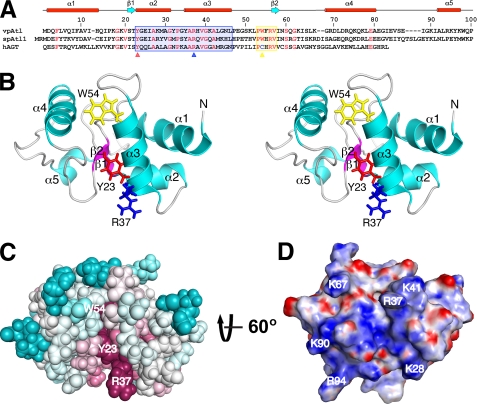

FIGURE 1.

Solution NMR structure of vpAtl. A, structure-based sequence alignment of vpAtl, spAtl1, and hAGT (residues 91–176). The sequence numbering for vpAtl and the secondary structural elements found in its solution NMR structure are shown above the alignment. Identical residues are shown in red. Residues in the helix-turn-helix and active site sequence motifs are boxed in blue and yellow, respectively. Key highly conserved, functionally important residues (Tyr23, Arg37, and Trp54 in vpAtl) are denoted by triangles below the alignment. B, stereoview into the putative alkyl-binding site in the lowest energy (CNS) conformer from the final solution NMR structure ensemble of vpAtl. The α-helices and β-strands are shown in cyan and magenta, respectively. Side chains of Tyr23, Arg37, and Trp54 are shown in red, blue, and yellow, respectively. C, ConSurf (28) image showing the conserved residues in the alkyl-binding site of vpAtl (same view as in B). Residue coloring ranges from magenta (highly conserved) to cyan (variable) and reflects the degree of residue conservation across ATL sequences extracted from the entire O6-alkylguanine-DNA methyltransferase protein domain family (PF01035, Pfam 23.0). D, DelPhi (29) electrostatic surface potential of vpAtl showing negative (red), neutral (white), and positive (blue) charges.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Complete details of the methods used in this work are provided in the supplemental material.

Sample Preparation

The cloning, expression, and purification of isotopically enriched protein samples of a 100-residue construct from the A79_1377 gene of V. parahaemolyticus AQ3810 (Northeast Structural Genomics code, VpR247; vpAtl) plus C-terminal affinity tag (LEHHHHHH) was performed following standard protocols of the Northeast Structural Genomics consortium (12). Samples of [U-13C,15N]- and [U(5%)-13C, (100%)-15N]vpAtl for NMR spectroscopy were concentrated by ultracentrifugation to 0.90 to 0.94 mm in 95% H2O, 5% 2H2O solution containing 20 mm MES, 200 mm NaCl, 10 mm dithiothreitol, 5 mm CaCl2 (pH 6.5). Analytical gel filtration chromatography, static light scattering (supplemental Fig. S1), and one-dimensional 15N T1 and T2 relaxation data (supplemental Fig. S2) demonstrate that the protein is monomeric in solution under the conditions used in the NMR studies. Single residue mutations of vpAtl (Y23A, Y23F, R37A, and W54A) were cloned using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) and expressed and purified following the same protocols used for the wild type protein.

NMR Spectroscopy and Resonance Assignment

All NMR spectra were collected at 25 °C on Bruker AVANCE 600- and 800-MHz spectrometers equipped with 1.7-mm TCI and 5-mm TXI cryoprobes, respectively, and a Varian INOVA 600-MHz instrument with a 5-mm HCN cold probe, and referenced to internal 2,2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonic acid. Complete 1H, 13C, and 15N resonance assignments for vpAtl were determined using conventional triple resonance NMR methods. Backbone assignments were made by combined use of AutoAssign 2.4.0 (13) and the PINE 1.0 server (14), and side chain assignment was completed manually. Histidine tautomeric states were elucidated by two-dimensional 1H-15N heteronuclear multiple-quantum coherence spectroscopy (15). Resonance assignments were validated using the Assignment Validation Suite software package (16) and deposited in the BioMagResDB (accession number 16272).

Structure Determination and Validation

The solution NMR structure of vpAtl was calculated using CYANA 3.0 (17, 18), and the 20 structures with lowest target function out of 100 in the final cycle calculated were further refined by restrained molecular dynamics in explicit water with CNS 1.2 (19, 20). Structural statistics and global structure quality factors were computed using the PSVS 1.3 software package (21) and MolProbity 3.15 server (22). The global goodness-of-fit of the final structure ensembles with the nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy (NOESY) peak list data were determined using the RPF analysis program (23). The final refined ensemble of 20 structures (excluding the C-terminal His6) was deposited in the Protein Data Bank (code 2KIF). All structure figures were made using PyMOL.

15N Relaxation Measurements

Residue-specific longitudinal and transverse 15N relaxation rates (R1 and R2) as well as 1H-15N heteronuclear NOE values were obtained on [U(5%)-13C, (100%)-15N]vpAtl at a 15N Larmor frequency of 60.8 MHz using standard two-dimensional gradient experiments (24). Generalized order parameters, S2, were computed from the backbone 15N relaxation and 1H-15N heteronuclear NOE data using the Modelfree 4.20 program (25, 26) assuming an isotropic model for molecular motion.

Human AGT Competition Assays

The inhibition of human AGT activity by spAtl1, vpAtl, and mutants of vpAtl was measured by adding purified hAGT to a preformed mixture of 3H-methylated DNA and ATL and then assaying the mixture for alkyltransferase activity by determining the transfer of [3H]methyl groups from O6-[3H]methylguanine in DNA to purified human AGT protein (27). The assay mixture (1.0 ml), incubated at 37 °C for 15 min, contained 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 5 mm dithiothreitol, 50 μg of hemocyanin, 0.1 mm EDTA, 15 μg of 3H-methylated calf thymus DNA, and different amounts of purified ATLs. Ten microliters of purified hAGT (0.5 pmol) were added to the above reaction mixture, and incubation was continued for 60 min at 37 °C and assayed for alkyltransferase activity.

RESULTS

Solution NMR Structure of vpAtl

The structure of vpAtl adopts an AGT-like fold composed of five α-helices (α1, Asp2–His13; α2, Tyr23–Gly31; α3, Tyr35–Leu46; α4, Gly68–Ala80; α5, Ala92–Lys97) and two short antiparallel β-strands (β1, Ser21–Thr22; β2, Val57–Ile58) in the core of the protein (Fig. 1B; supplemental Fig. S3). Structural statistics and a summary of the NMR data from this study are provided in Table 1 and supplemental Fig. S4, respectively. By analogy to homologs (see below), helices 2 and 3 include the helix-turn-helix DNA-binding motif. A ConSurf (28) analysis of all ATLs from the AGT protein domain family (PF01035) reveals that highly conserved residues, demonstrated in spAtl1 (10) to be involved in flipping of the damaged alkyl guanine (Tyr23 and Arg37), interacting with the orphaned cytosine (Arg37), and binding to the alkyl moiety (Tyr23 and Trp54), are clustered in a partially occluded binding pocket (Fig. 1C). This face of the protein also features a quite positive electrostatic surface potential (29) due to several basic residues, consistent with its role in DNA binding (Fig. 1D; supplemental Fig. S5). The binding pocket is flanked by the less conserved binding site loop (preceding helix 4) and C-terminal loop (between helices 4 and 5). In spAtl1 these loops are important for open-to-closed (free-to-bound) conformational changes and mediate interactions with proteins in the NER pathway, respectively (10). Two histidines (His13 in helix 1 and His38 flanking Arg37 in helix 3), largely unique to ATLs from Vibrio species, adopt neutral Nϵ2H tautomers under the conditions used in this study (supplemental Fig. S6).

TABLE 1.

Summary of NMR and structural statistics for vpAtl

Structural statistics were computed for the ensemble of 20 deposited structures (PDB entry, 2KIF). r.m.s., root mean square; r.m.s.d., r.m.s. deviation.

| Completeness of resonance assignmentsa | |

| Backbone | 97.6% |

| Side chain | 98.3% |

| Aromatic | 100% |

| Stereospecific methyl | 100% |

| Conformationally restricting constraintsb | |

| Distance constraints | |

| Total | 2448 |

| Intra-residue (i = j) | 621 |

| Sequential (|i − j| = 1) | 547 |

| Medium range (1 < |i − j| < 5) | 493 |

| Long range (|i − j| ≥ 5) | 787 |

| Distance constraints/residue | 24.2 |

| Dihedral angle constraints | 125 |

| Hydrogen bond constraints | |

| Total | 62 |

| Long range (|i − j| ≥5) | 8 |

| No. of constraints/residue | 26.1 |

| No. of long range constraints/residue | 7.9 |

| Residual constraint violationsb | |

| Average no. of distance violations/structure | |

| 0.1–0.2 Å | 1.55 |

| 0.2–0.5 Å | 0.1 |

| >0.5 Å | 0 |

| Average r.m.s. distance violation/constraint | 0.01 Å |

| Maximum distance violation | 0.31 Å |

| Average no. of dihedral angle violations/structure | |

| 1–10° | 1.7 |

| >10° | 0 |

| Average r.m.s. dihedral angle violation/constraint | 0.37° |

| Maximum dihedral angle violation | 4.60° |

| r.m.s.d. from average coordinatesb,c | |

| Backbone atoms | 0.5 Å |

| Heavy atoms | 0.8 Å |

| Procheck Ramachandran statisticsb,c | |

| Most favored regions | 91.5% |

| Additional allowed regions | 8.5% |

| Generously allowed | 0.0% |

| Disallowed regions | 0.0% |

| MolProbity Ramachandran statisticsd | |

| Favored regions | 95.4% |

| Allowed | 100.0% |

| Global quality scoresb | Raw | Z-score |

|---|---|---|

| Verify3D | 0.48 | 0.32 |

| ProsaII | 0.91 | 1.08 |

| Procheck(φ-ψ)c | −0.13 | −0.20 |

| Procheck(all)c | −0.02 | −0.12 |

| Molprobity clash | 18.92 | −1.72 |

| RPF scorese | ||

| Recall | 0.974 | |

| Precision | 0.937 | |

| F measure | 0.955 | |

| DP score | 0.835 | |

a Computed using AVS software (16) from the expected number of peaks, excluding the following: highly exchangeable protons (N-terminal, Lys, and Arg amino groups, hydroxyls of Ser, Thr, and Tyr), carboxyls of Asp and Glu, nonprotonated aromatic carbons, and the C-terminal His6 tag.

b Calculated using PSVS 1.3 program (21). Average distance violations were calculated using the sum over r−6.

c Ordered residue ranges (S(φ ) + S(ψ ) > 1.8): 2–32, 35–47, 50–100.

d Calculated for all residues in the ensemble using the MolProbity 3.15 server (22).

e RPF scores (23) reflecting the goodness-of-fit of the final ensemble of structures (including disordered residues) to the NMR data.

Backbone Dynamics of vpAtl

The internal dynamic properties of vpAtl were further investigated using backbone 15N relaxation and heteronuclear NOE experiments (24). Reduced 15N R2 relaxation rates and 1H-15N heteronuclear NOE values are observed for residues Leu46 to Leu52, which span the C-terminal end of helix 3 and the loop preceding the heart of the substrate-binding site (Fig. 2A). These data result in reduced order parameters, S2, indicative of enhanced backbone motions within this binding pocket cap. Moreover, there are a handful of weak/missing backbone amide NMR resonances in the protein, consistent with conformational exchange broadening. Mapping these effects onto the structure of vpAtl clearly reveals that several conformationally dynamic residues cluster around the substrate binding pocket (Fig. 2B). This plasticity provides a structural basis for the broad range of guanine lesions that can be recognized by ATLs (8, 11); flexibility in the recognition cavity provides a capacity for molding the binding site around various alkyl guanine lesions besides O6-mG.

FIGURE 2.

Backbone dynamics of vpAtl. A, plots of backbone amide 15N R1 and R2 relaxation rates, 1H-15N heteronuclear NOEs, and generalized order parameters, S2, versus residue number obtained on [U(5%)-13C, (100%)-15N]-vpAtl at a 15N Larmor frequency of 60.8 MHz. Order parameters were computed using the Modelfree 4.20 program (25, 26) assuming an isotropic model, yielding an overall rotational correlation time, τc, of 7.9 ns. B, backbone dynamics of vpAtl mapped onto its structure. Residues with S2 ≤0.7, indicative of enhanced backbone flexibility, are in red, and residues with weak or missing 1H-15N heteronuclear single quantum coherence resonances are colored yellow. Prolines are shown in gray, and the substrate binding pocket and binding pocket cap are indicated.

Comparison to Related Structures

The solution structure of vpAtl is structurally very similar to the recent crystal structures of bound and free spAtl1 (Dali (30) Z-scores: 3GYH, 16.1; 3GX4, 15.7; 3GVA, 15.0; Cα r.m.s.d. values: 3GYH, 1.7 Å; 3GX4, 1.8 Å; 3GVA, 1.9 Å) (10) as well as to structures of the C-terminal domains of human AGT (3, 4, 31, 32), Escherichia coli Ada-C (33), and archaeal (34, 35) AGTs (Dali Z-scores ranging from 5.4 to 11.1), which share < 30% sequence identity with vpAtl. Considering the metric of modeling leverage (36), an important measure of the new structural information provided by a protein structure, the vpAtl structure has a novel leverage value of 26 models and total modeling leverage value of 1,493 structural models (UniProt release 12.8; PSI Blast E < 10−10). Of these, 17 sequences are putative ATLs from eukaryotes, including the recently identified ATL from sea anenome (10). The vpAtl structure most closely resembles the closed (DNA-bound) form of spAtl1, and conserved residues important for damage recognition and binding superimpose well in the structures (Fig. 3A). There are, however, subtle differences between the structures. Both the binding site and C-terminal loops are shorter in vpAtl, and the binding pocket in vpAtl is partially buried by residues from the binding site loop (Ser65 and Leu66) and the binding pocket cap (Leu46–Pro53), resulting in a much smaller binding pocket (< Area > (Å2) = 185 ± 61) than that observed for spAtl1 (10). However, as discussed above, the 15N relaxation and 1H-15N heteronuclear NOE data along with weak/missing backbone amide resonances indicate that there are backbone conformational dynamics within the binding pocket cap (Fig. 2), suggesting that vpAtl may adopt conformations in which the substrate binding pocket is more exposed.

FIGURE 3.

Conserved structure and DNA binding properties of vpAtl. A, overlay of the vpAtl structure (cyan) and the crystal structure of spAtl1 bound to O6-mG-DNA (Protein Data Bank code 3GX4; magenta) (10). The side chains of Tyr23, Arg37, and Trp54 are shown in red, blue, and yellow, respectively, and the O6-mG in the bound spAtl1 structure is shown in gray. B, percent activity of hAGT as a function of ATL concentration for vpAtl (triangles) and spAtl1 (circles). C, effect of mutating Tyr23 in vpAtl on hAGT activity; wild type vpAtl (black), [Y23A]-vpAtl (red triangles), and [Y23F]-vpAtl (red circles). D, effect of mutating Arg37 and Trp54 in vpAtl on hAGT activity; wild type vpAtl (black), [R37A]-vpAtl (blue), and [W54A]-vpAtl (gold).

Inhibition of hAGT-mediated DNA Repair by vpAtl

Like the ATL proteins from E. coli, S. pombe, and Thermus thermophilus (7–9), vpAtl does not exhibit alkyltransferase activity (data not shown). However, a common trait of ATLs is their ability to tightly bind O6-alkylguanine DNA, with up to subnanomolar affinity (10), and prevent its repair by AGTs. The inhibition of human AGT O6-mG repair by vpAtl and spAtl1 is shown in Fig. 3B. In this assay, varying amounts of ATL are preincubated with 3H-methylated DNA, followed by incubation with human AGT and measurement of the amount of radiolabel transferred to the AGT (27). As expected for an ATL, vpAtl strongly inhibits O6-mG repair by hAGT when present in molar excess and exhibits a similar affinity for alkylated DNA compared with spAtl1.

The DNA binding roles of selected conserved residues in vpAtl, namely Tyr23, Arg37, and Trp54, were further examined using this competition assay (Fig. 3, C and D). Replacing either Tyr23 or Arg37 with alanine yields mutants that have no effect on hAGT activity, meaning that their ability to bind alkylated DNA is severely impaired. On the other hand, the Y23F mutant is still capable of blocking repair of methylated DNA by hAGT, albeit not as effectively as wild type vpAtl (Fig. 3C). These data are consistent with the requirement of a bulky aromatic residue at the position of Tyr23 to flip the damaged guanine base into the binding pocket and the function of Arg37 to intercalate the DNA and hydrogen bond to the orphaned cytosine (10). Similar effects were observed in analogous mutagenesis experiments on hAGT (37, 38). Finally, swapping Trp54 for an alanine (Trp and Ala are present in ≈89 and ≈9%, respectively, of ATLs; Pfam 23.0) results in an ATL that also exhibits some affinity for methylated DNA, although less than that for wild type vpAtl (Fig. 3D); a similar effect was observed for the ATL from E. coli (7). Overall, the relative affinities of the ATLs and mutants studied here for O6-mG DNA follow the trend: spAtl1 ≥ vpAtl > [Y23F]-vpAtl > [W54A]-vpAtl ≫ [Y23A]-vpAtl ≈ [R37A]-vpAtl.

DISCUSSION

The results on vpAtl presented here demonstrate a high degree of structural conservation between bacterial and yeast ATLs and demonstrate that vpAtl exhibits the hallmark biochemical behavior of ATLs. Furthermore, mutation of highly conserved residues Tyr23 or Arg37 to alanine abolishes the ability of vpAtl to block methylated DNA repair by human AGT, and the affinity of the Y23F mutant for methylated DNA demonstrates the necessity of a bulky aromatic residue in this position. To our knowledge, this is the first mutagenesis study examining these critical residues in ATLs and their roles in binding to O6-mG DNA and blocking human AGT activity. Taken together, our structural and mutagenesis results provide strong evidence for a conserved mechanism of ATL binding to alkylated DNA mediated by critical tyrosine and arginine residues and involving the flipping out of the damaged base (10).

Like several other organisms, including E. coli, V. parahaemolyticus possesses genes for both ATL and AGT. It was recently shown that repair of O6-alkylguanine lesions in E. coli is segregated between the direct repair (AGT) and ATL-coupled NER pathways on the basis of the size of the alkyl group, with the latter repairing O6-alkylguanine adducts larger in size than a methyl group, which are poor substrates for bacterial AGTs (11). Moreover, the high structural similarity between free vpAtl and free and bound spAtl1 suggests that vpAtl also mediates O6-alkylguanine repair by recruitment of proteins involved in NER. Hence, we postulate that vpAtl is also capable of interacting with a broad range of O6-alkylguanine substrates and likely mediates an analogous cross-talk between alkyltransferase and NER repair pathways. In this scenario, vpAtl would function to channel bulkier O6-alkylguanine lesions into the NER pathway. Conformational dynamics within the recognition cavity of apo-ATL, revealed for the first time by this structural NMR study, confer functional plasticity that may be essential for providing its wider range of guanine lesion specificity.

In light of the recent structural and biochemical characterization of S. pombe Atl1 and the predicted occurrence of ATLs in archaea (10), our results for vpAtl also provide further support for the hypothesis that ATLs are an ancient class of nonenzymatic proteins at the interface of the base and nucleotide excision repair pathways for DNA repair. These results thus help provide a unified understanding of DNA damage responses, which has been a major goal for the structural biology of DNA repair since the discovery of base and nucleotide excision repair pathways (39).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank R. L. Belote, G. V. T. Swapna, and M. Fischer for valuable scientific discussions.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant U54-GM074958 (to G. T. M.) from NIGMS (Protein Structure Initiative) and Grants CA097209 (to J. A. T. and A. E. P.) and CA018137 (to S. K.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental “Materials and Methods,” Figs. S1–S6, and additional references.

- AGT

- O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase

- ATL

- alkyltransferase-like protein

- MES

- 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid

- NER

- nucleotide excision repair

- NOE

- nuclear Overhauser effect

- r.m.s.d.

- root mean square deviation

- O6-mG

- O6-methylguanine

- hAGT

- human AGT.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tubbs J. L., Pegg A. E., Tainer J. A. (2007) DNA Repair 6, 1100–1115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verbeek B., Southgate T. D., Gilham D. E., Margison G. P. (2008) Br. Med. Bull. 85, 17–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daniels D. S., Woo T. T., Luu K. X., Noll D. M., Clarke N. D., Pegg A. E., Tainer J. A. (2004) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11, 714–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duguid E. M., Rice P. A., He C. (2005) J. Mol. Biol. 350, 657–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Margison G. P., Butt A., Pearson S. J., Wharton S., Watson A. J., Marriott A., Caetano C. M., Hollins J. J., Rukazenkova N., Begum G., Santibáñez-Koref M. F. (2007) DNA Repair 6, 1222–1228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reissner T., Schorr S., Carell T. (2009) Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 48, 7293–7295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pearson S. J., Ferguson J., Santibanez-Koref M., Margison G. P. (2005) Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 3837–3844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pearson S. J., Wharton S., Watson A. J., Begum G., Butt A., Glynn N., Williams D. M., Shibata T., Santibáñez-Koref M. F., Margison G. P. (2006) Nucleic Acids Res. 34, 2347–2354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morita R., Nakagawa N., Kuramitsu S., Masui R. (2008) J. Biochem. 144, 267–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tubbs J. L., Latypov V., Kanugula S., Butt A., Melikishvili M., Kraehenbuehl R., Fleck O., Marriott A., Watson A. J., Verbeek B., McGown G., Thorncroft M., Santibanez-Koref M. F., Millington C., Arvai A. S., Kroeger M. D., Peterson L. A., Williams D. M., Fried M. G., Margison G. P., Pegg A. E., Tainer J. A. (2009) Nature 459, 808–813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mazon G., Philippin G., Cadet J., Gasparutto D., Fuchs R. P. (2009) DNA Repair 8, 697–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Acton T. B., Gunsalus K. C., Xiao R., Ma L. C., Aramini J., Baran M. C., Chiang Y. W., Climent T., Cooper B., Denissova N. G., Douglas S. M., Everett J. K., Ho C. K., Macapagal D., Rajan P. K., Shastry R., Shih L. Y., Swapna G. V., Wilson M., Wu M., Gerstein M., Inouye M., Hunt J. F., Montelione G. T. (2005) Methods Enzymol. 394, 210–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moseley H. N., Monleon D., Montelione G. T. (2001) Methods Enzymol. 339, 91–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bahrami A., Assadi A. H., Markley J. L., Eghbalnia H. R. (2009) PLoS Comput. Biol. 5, e1000307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pelton J. G., Torchia D. A., Meadow N. D., Roseman S. (1993) Protein Sci. 2, 543–558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moseley H. N., Sahota G., Montelione G. T. (2004) J. Biomol. NMR 28, 341–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Güntert P., Mumenthaler C., Wüthrich K. (1997) J. Mol. Biol. 273, 283–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herrmann T., Güntert P., Wüthrich K. (2002) J. Mol. Biol. 319, 209–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brünger A. T., Adams P. D., Clore G. M., DeLano W. L., Gros P., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Jiang J. S., Kuszewski J., Nilges M., Pannu N. S., Read R. J., Rice L. M., Simonson T., Warren G. L. (1998) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 54, 905–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Linge J. P., Williams M. A., Spronk C. A., Bonvin A. M., Nilges M. (2003) Proteins 50, 496–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhattacharya A., Tejero R., Montelione G. T. (2007) Proteins 66, 778–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davis I. W., Leaver-Fay A., Chen V. B., Block J. N., Kapral G. J., Wang X., Murray L. W., Arendall W. B., 3rd, Snoeyink J., Richardson J. S., Richardson D. C. (2007) Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W375–W383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang Y. J., Powers R., Montelione G. T. (2005) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 1665–1674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farrow N. A., Muhandiram R., Singer A. U., Pascal S. M., Kay C. M., Gish G., Shoelson S. E., Pawson T., Forman-Kay J. D., Kay L. E. (1994) Biochemistry 33, 5984–6003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mandel A. M., Akke M., Palmer A. G., 3rd (1995) J. Mol. Biol. 246, 144–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palmer A. G., 3rd, Rance M., Wright P. E. (1991) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 113, 4371–4380 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanugula S., Pegg A. E. (2001) Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 38, 235–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glaser F., Pupko T., Paz I., Bell R. E., Bechor-Shental D., Martz E., Ben-Tal N. (2003) Bioinformatics 19, 163–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rocchia W., Alexov E., Honig B. (2001) J. Phys. Chem. B 105, 6507–6514 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holm L., Kääriäinen S., Rosenström P., Schenkel A. (2008) Bioinformatics 24, 2780–2781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Daniels D. S., Mol C. D., Arvai A. S., Kanugula S., Pegg A. E., Tainer J. A. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 1719–1730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wibley J. E., Pegg A. E., Moody P. C. (2000) Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 393–401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moore M. H., Gulbis J. M., Dodson E. J., Demple B., Moody P. C. (1994) EMBO J. 13, 1495–1501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hashimoto H., Inoue T., Nishioka M., Fujiwara S., Takagi M., Imanaka T., Kai Y. (1999) J. Mol. Biol. 292, 707–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roberts A., Pelton J. G., Wemmer D. E. (2006) Magn. Reson. Chem. 44, S71–S82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu J., Montelione G. T., Rost B. (2007) Nat. Biotechnol. 25, 849–851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kanugula S., Goodtzova K., Edara S., Pegg A. E. (1995) Biochemistry 34, 7113–7119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goodtzova K., Kanugula S., Edara S., Pegg A. E. (1998) Biochemistry 37, 12489–12495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huffman J. L., Sundheim O., Tainer J. A. (2005) Mutat. Res. 577, 55–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.