Abstract

Herein we describe the development and application of a set of novel N, N-dimethyl leucine (DiLeu) 4-plex isobaric tandem mass (MS2) tagging reagents with high quantitation efficacy and greatly reduced cost for neuropeptide and protein analysis. DiLeu reagents serve as attractive alternatives for isobaric tag for relative and absolute quantitation (iTRAQ) and tandem mass tags (TMTs) due to their synthetic simplicity, labeling efficiency and improved fragmentation efficiency. DiLeu reagent resembles the general structure of a tandem mass tag in that it contains an amine reactive group (triazine ester) targeting the N-terminus and ε-amino group of the lysine side-chain of a peptide, a balance group, and a reporter group. A mass shift of m/z 145.1 is observed for each incorporated label. Intense a1 reporter ions at m/z 115.1, 116.1, 117.1, and 118.1 are observed for all pooled samples upon MS2. All labeling reagents are readily synthesized from commercially available chemicals with greatly reduced cost. Labels 117 and 118 can be synthesized in one step and labels 115 and 116 can be synthesized in two steps. Both DiLeu and iTRAQ reagents show comparable protein sequence coverage (~43%) and quantitation accuracy (<15%) for tryptically digested protein samples. Furthermore, enhanced fragmentation of DiLeu labeling reagents offers greater confidence in protein identification and neuropeptide sequencing from complex neuroendocrine tissue extracts from a marine model organism, Callinectes sapidus.

Keywords: tandem mass tag, quantitation, isobaric tagging reagents, stable isotope labeling, peptidomics

INTRODUCTION

It has become increasingly important to determine relative abundance of protein or endogenous peptide expression levels in different biological states using mass spectrometry (MS). Numerous MS-based chemical derivatization quantitation approaches such as mass-difference labeling and isobaric labeling methodologies have been developed and widely used for quantitative proteomics and peptidomics.1 Mass-difference labeling approaches introduce a mass difference for the same peptide by incorporating a light or heavy isotopic form of the labeling reagent. Light and heavy labeled peptides are combined prior to MS analysis and quantitation is accomplished by comparing the extracted ion chromatogram peak areas of light and heavy forms of the same peptide. Methods such as isotope-coded affinity tags (ICAT),2–4 stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture (SILAC),5 4-trimethylammoniumbutyryl (TMAB) labels,6 and reductive formaldehyde dimethylation7 have been widely used in mass-difference quantitation proteomics. Although being well-established methodologies for quantitative proteomics, these mass-difference labeling has two general limitations. First, only a binary set of samples can be compared due to the use of light and heavy labeling of a peptide. Second, mass-difference labeling increases mass spectral complexity by introducing extra pair of labeled peptides, thus decreasing the confidence and accuracy of quantitation. The first limitation has been addressed and overcome by several research groups by introducing multiple heavy labeled reagents, rather than just one.8–10 The second limitation is an inherent drawback of the mass-difference approach and the spectral complexity is increased with the use of multiple heavy isotope labeling reagents. This problem is solved by the isobaric labeling approach.

Tandem mass tags (TMTs) were the first isobaric labeling reagents used to improve the accuracy for peptide and protein quantitation by simultaneous identification and relative quantitation during MS2 experiments.11 Two generations of TMTs were reported (TMT1 and TMT2) and each generation had two isobaric labels. Amine groups (N-terminus and ε-amino group of the lysine side-chain) in peptides labeled with TMT1 produces fragments at m/z 287 and 290 at 70v collision energy, whereas TMT2 produces fragments at m/z 270 and 273 at 40v collision energy.9 Relative quantitation can be performed by comparing the intensities of these fragments to one another. A 6-plex version of TMTs was reported recently.12 iTRAQ follows the same principle as TMTs quantitation, but it improves the quantitation further by providing four isobaric labels with signature reporter ions that are one Da apart upon MS2 fragmentation.13 iTRAQ allows for the quantitation of proteins present in four different biological states simultaneously. These tags are structurally identical isobaric compounds with different isotopic combinations. Each sample is labeled individually, pooled together and introduced into the mass spectrometer for quantitative analysis. Since samples are isobarically labeled, the same peptide from four samples produces a single peak in MS mode, but upon MS2 fragmentation each labeled sample gives rise to a unique reporter ion (m/z =114.1, 115.1, 116.1, and 117.1) along with sequence-specific backbone cleavage for identification. Relative quantitation is achieved by correlating the relative abundance of each reporter ion with its originating sample.

Isobaric MS2 tagging approaches have been successfully used in MS-based quantitative proteomics. However, their application as a routine tool for quantitative MS studies is limited by high cost. The high cost of commercial TMTs and iTRAQ comes from the challenge of synthesizing these compounds; multiple steps involved in synthesis lead to moderate to low yield. A set of 6-plex deuterium-labeled DiART reagents was reported very recently with reduced cost of isobaric labeling. However, seven steps were still required to synthesize these compounds with 30%–40% overall yield.14 A new type of isobaric MS2 tags with fewer steps involved in synthesis is desirable to further reduce experimental cost while taking full technical advantages of isobaric MS2 tagging approach. Formaldehyde dimethylation represents one of the most affordable approaches among all isotopic chemical derivatization techniques used for MS-based peptide and protein quantitation.10, 15–29 However, isotopic formaldehyde labeling is a mass-difference labeling approach and thus lacks the advantages offered by isobaric labeling approach. We have used formaldehyde labeling technique for improved peptide fragmentation, enhanced neuropeptide de novo sequencing and quantitation.30–34 A notable feature of this labeling approach is the production of intense immonium a1 ions when dimethylated neuropeptides undergo MS2 dissociation.30, 35 The formation of the dimethylated a1 ion is shown in Scheme 1A.30, 35 The structural similarity of iTRAQ reporter ion and dimethylated amino acid a1 ion inspired the design of novel dimethyl leucine isobaric MS2 tags (DiLeu). This manuscript describes the development and evaluation of a set of 4-plex DiLeu reagents for protein quantitation and neuropeptide analysis.

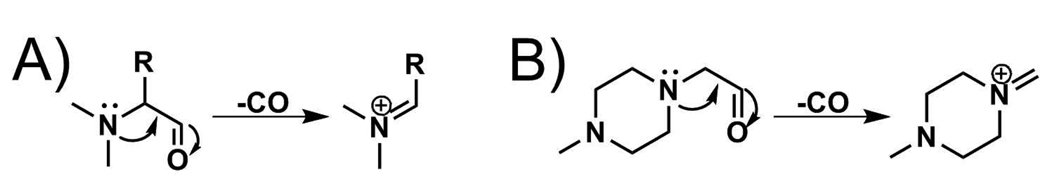

Scheme 1.

Formation of (A) dimethyl amino aicd a1 ion and (B) iTRAQ reporter ion.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials

All isotopic reagents for the synthesis of labels including: leucines (L-leucine and L-leucine-1-13C, 15N), heavy formaldehyde (CD2O), sodium cyanoborodeuteride (NaBD3CN), 18O water 97% (H218O) and deuterium water (D2O) were purchased from ISOTEC Inc (Miamisburg, OH). Sodium cyanoborohydride (NaBH3CN) was purchased from Sigma. N-Methylmorpholine (NMM) was purchased from TCI America (Tokyo, Japan). Chromasolv water, acetonitrile, and formic acid (FA) for UPLC were purchased from Fluka (Büchs, Switzerland). Neuropeptide standard allatostatin I (AST-I, GDGRLYAFGL-NH2) and calmodulin dependent protein kinase substrate analog (PLRRTLSVAAa) were purchased from American Peptide Company (Sunnyvale, CA). Sequencing grade trypsin was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). ACS grade methanol (MeOH), dichloromethane (CH2Cl2), acetonitrile (ACN), N, N-Dimethylformamide (DMF), and 4-(4, 6-Dimethoxy-1, 3, 5-triazin-2-yl)-4-methylmorpholinium chloride (DMTMM) were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). Ethanol was purchased from Pharmco-AAPER (Brookfield, CT). Ammonium formate, formaldehyde (CH2O), tris-(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) 1M pH = 8.5, iodoacetamide (IAA), triethylammonium bicarbonate (TEAB), sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS, ≥98%), α-cyano-4-hydroxy-cinnamic acid (CHCA) and bovine serum albumin (BSA) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). The 4-plex iTRAQ reagents were provided by Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). 2, 5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHB) was obtained from MP Biomedicals, Inc. (Solon, OH).

Synthesis of N, N-Dimethylated Leucine (DiLeu)

A 120 mg portion of sodium cyanoborohydride (NaBH3CN) was dissolved in 125 µL of H2O or D2O. A 100 mg portion of leucine or isotopic leucine was suspended in the mixture, the vial was sealed and mixture was kept in an ice-water bath for 30 min to cool down. 285 µL of light formaldehyde CH2O (37% w/w) or a 530 µL heavy formaldehyde CD2O (20% w/w) was then added to the mixture dropwise. The mixture was stirred in an ice-water bath for 30 min. The reaction was monitored by ninhydrin staining on a thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plate. The target molecule was purified by flash column chromatography (MeOH/CH2Cl2). Synthetic routes are shown in Scheme 2A. Both formaldehyde and sodium cyanoborohydride are very toxic by inhalation, in contact with skin, or if swallowed and may cause cancer and heritable genetic damage. These chemicals and reaction should be handled in a fume hood.

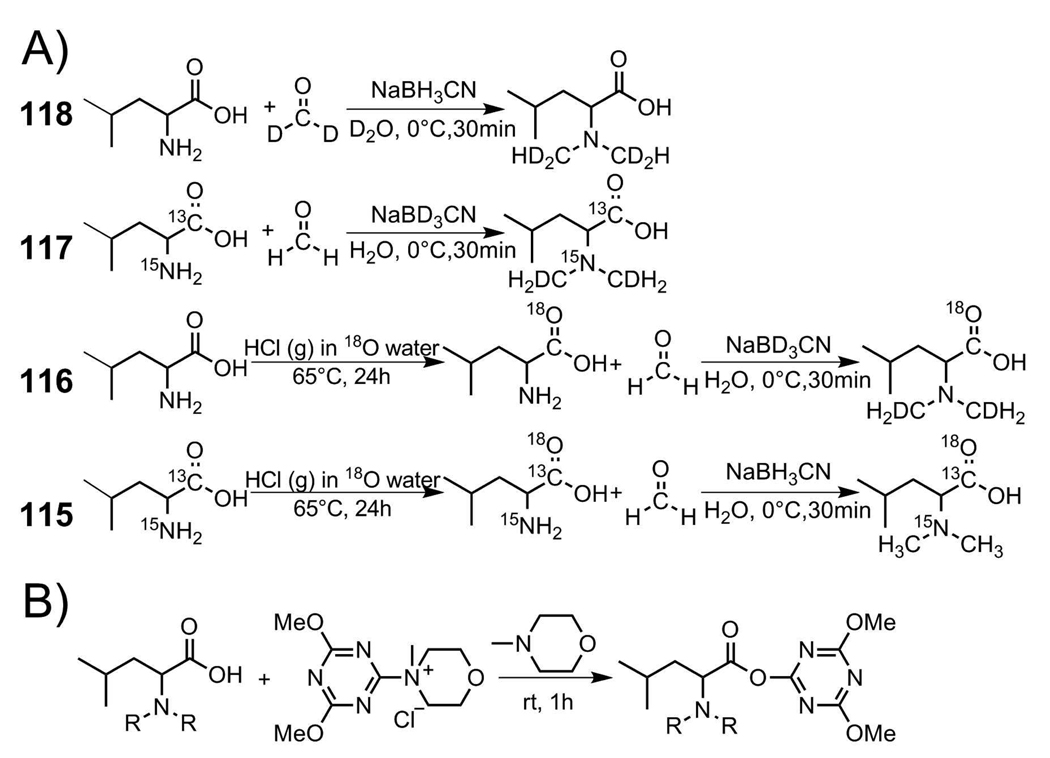

Scheme 2.

(A) Synthesis of isobaric labels and (B) activation using 4-(4, 6-Dimethoxy-1, 3, 5-triazin-2-yl)-4-methylmorpholinium chloride (DMTMM)/ N-Methylmorpholine (NMM)

18O Exchange

18O exchange is required for both the 115 and 116 labels to have the same masses as labels 117 and 118. 18O exchange was carried out according to a procedure previously reported.36 Briefly, 25 mg leucine or isotopic leucine was dissolved in 1N HCl H218O solution (pH 1) and stirred on a hot plate at 65°C for 24 h, followed by reductive N, N-dimethylation. Synthetic routes are shown in Scheme 2A.

Synthesis of DiLeu Triazine Ester

1 mg DiLeu in 50 µL DMF was combined with 1.86 mg DMTMM and 0.74 µL NMM in a 1.6 mL eppendorf vial. Mixing was performed at room temperature for 1h and stored at −20°C until needed for future labeling. The general synthetic route is shown in Scheme 2B.

Protein Reduction, Alkylation, and Digestion

BSA (100 µg) aliquots were resuspended in 0.5 M TEAB, pH 8.5 and 2% (w/v) SDS, reduced with 5 mM TECP for 1h at 60°C, and alkylated with 84 mM IAA for 10 min in darkness. After reduction and alkylation, the protein was digested overnight with trypsin at 37°C at a ratio of 1:10 trypsin to protein. After digestion, samples were pooled and divided into 50 µg aliquots. Aliquots were then dried using a Savant SC 110 SpeedVac concentrator (Thermo Electron Corporation, West Palm Beach, FL) and re-dissolved in 10 µL of TEAB before labeling.

Neuropeptide Extraction

Pericardial organs (POs) of blue crabs were dissected out in chilled physiological saline and then immediately transferred to 20 µL cold DMF. POs from twenty crabs were divided into four groups (five crabs per group). POs in each group were pooled after dissection and homogenized in a manual glass tissue homogenizer using 200 µL DMF as the extraction buffer. The homogenate was centrifuged at 13,200 rpm for 10 minutes at room temperature in an Eppendorf 5415 D microcentrifuge (Brinkmann Instruments Inc., Westbury, NY). The supernatant was transferred to a clean 0.6 mL eppendorf vial and placed on ice. The pellet was then extracted 3 more times with 100 µL aliquots of DMF and the supernatant from each extraction was combined. The resulting supernatant was concentrated to dryness using SpeedVac and re-suspended in 10 µL of TEAB before labeling.

Protein Digest Labeling

In order to compare 4-plex quantitation between DiLeu and iTRAQ, two 4-plex sets of digested protein BSA aliquots (50 µg) were labeled with DiLeu and iTRAQ reagents. DiLeu labeling was performed by transferring 25 µL of labeling solution into the sample vial. iTRAQ labeling was performed by placing 35 µL of ethanol solubilized reagent in the sample vial. Both sample sets were labeled at room temperature for 1h and quenched for 30 min by adding 100 µL of water. Labeled samples were combined at equal ratios (1:1:1:1) and dried under SpeedVac.

Neuropepide Extract Labeling

The same DiLeu labeling procedure outlined above for protein digest labeling was used to label neuropeptide extracts from blue crab POs.

Strong Cation Exchange Chromatography

Both iTRAQ and DiLeu labeled peptides were fractionated by strong cation exchange (SCX) liquid chromatography using PolySULFOETHYL A 200 mm × 2.1 mm, 5 µm, 300Å column (PolyLC, Columbia, MD). Buffer A was 25 mM ammonium formate, 10% (v/v) acetonitrile, pH 2.9, and buffer B was 25 mM ammonium formate, 500 mM ammonium formate, 10% (v/v) acetonitrile, pH 4.3. The dried labeled samples were re-suspended in buffer A and loaded onto the SCX column. After sample loading and washing with buffer A for 3 min, buffer B concentration was increased from 0% to 50% in 20 min and then increased to 100% at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min. Twelve fractions were collected based on SCX chromatogram and combined then followed by drying under SpeedVac.

Reversed Phase NanoLC ESI MS/MS

Tryptic peptide and neuropeptide labeled samples were analyzed using a Waters nanoAcquity UPLC system coupled online to a Waters Micromass QTOF mass spectrometer (Waters Corp., Milford, MA, USA). Tryptic peptide samples were dissolved in 0.1% formic acid(aq) (FA), injected and trapped onto a C18 trap column for 10 minutes (Zorbax 300SB-C18 Nano trapping column, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clare, CA, USA), and eluted onto a home-made C18 column (75 µm × 100 mm, 3µm, 100Å) using a linear gradient (300 nl/min) from 95% buffer A (0.1% FA in H2O) to 45% buffer B (0.1%FA in ACN) over 33 min. The linear gradient used for labeled neuropeptide extract solutions was from 95% buffer A (0.1% FA in H2O) to 45% buffer B (0.1% FA in ACN) over 60 min. Survey scans were acquired from m/z 400–1800 with up to two precursors selected for MS2 from m/z 50–1800 with 3 min dynamic exclusion. iTRAQ used a collision energy 20% greater than that used for DiLeu.

MALDI FT-ICR MS

The analysis of DiLeu labeled peptide standard was performed using a Varian/IonSpec Fourier transform mass spectrometer (Lake Forest, CA) equipped with a 7.0 T actively shielded superconducting magnet. A 355 nm Nd:YAG laser was used for ionization/desorption. A saturated solution of 2, 5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHB, 150 mg/mL of 50: 50 H2O/MeOH, v/v) was used as the matrix for sample spotting. Spectra were collected in positive ion mode.

MALDI TOF/TOF MS

A model 4800 MALDI TOF/TOF analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Framingham, MA) equipped with a 200 Hz, 355 nm Nd: YAG laser was used. Acquisitions were performed in positive ion reflectron mode. Instrument parameters were set using the 4000 Series Explorer software (Applied Biosystems). Mass spectra were obtained by averaging 900 laser shots covering mass range m/z 500–4000. MS2 was achieved by 1 kV collision induced activation (CID) using air as collision gas. For sample spotting, equal volumes of 0.4 µL sample solution and α-cyano-4-hydroxy-cinnamic acid (CHCA) matrix solution in 60% ACN were mixed and allowed to dry prior to analysis.

Data Analysis and Quantitation

DiLeu reagent labeled neuropeptide standards were identified and sequenced using Waters Masslynx peptide sequencing software (PepSeq). BSA tryptic peptide identifications were performed using the X! Tandem search engine (The Global Proteome Machine Organization). Database search of labeled BSA was restricted to tryptic peptides of BSA sequence FASTA file. Carbamidomethyl on cysteine was selected as fixed modification; N-terminal, lysine, tyrosine DiLeu modifications and methionine oxidation were selected as variable, one missed cleavage was allowed, and the precursor error tolerance was set to <100 ppm. Identified labeled peptide spectra were converted to dta files using PLGS 2.1 software (Waters) and quantified by comparing the intensities of the reporter ions using Quant MATLAB® scripts.37 Reporter ions were changed to 115.1, 116.1, 117.1 and 118.1 with peak detection window of 0.1 Da. Isotope correction factors were applied to correct the peak intensities calculated for each reporter ion to account for the losses to, and gains from, other reporter ions.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Rationale for the Development of DiLeu Reagents

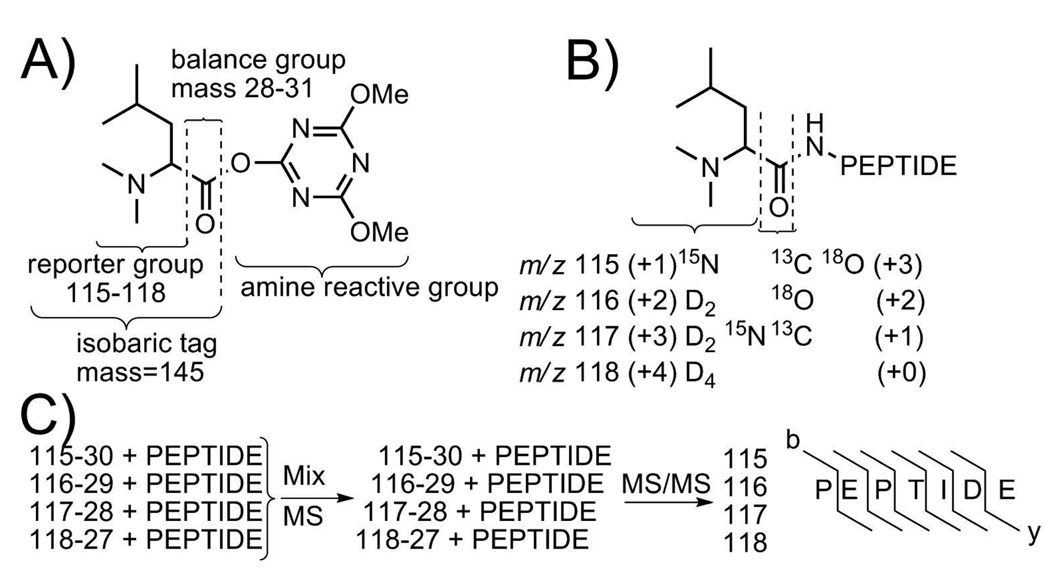

It was previously shown that the dimethylated a1 ion can be used as a peptide quantitiation tool due to its high intensity.7 We also observed that MS2 of dimethylated neuropeptides with leucine at the N-termini yielded the most intense dimethylated a1 ions as compared to other N-terminal amino acids. The formation of the iTRAQ reporter ions (as shown in Scheme 1B) shares the same mechanism as the dimethylated amino acid a1 ion. The difference between these two ions is that the iTRAQ reporter ion is a cyclic immonium ion and dimethylated a1 ion is an amino immonium ion. Given that a dimethylated leucine provides an intense a1 ion which shares the same formation mechanism as an iTRAQ reporter ion and most importantly isotopic leucines with different isotope combinations are commercially available, we propose the design and development of a set of novel DiLeu 4-plex isobaric MS2 tags. These new tags resemble the structure of the original iTRAQ reagent (reporter group, balance group, amine reactive group) but differ in the use of isotopically dimethylated leucine a1 ions as signature reporter ions.34 The structure of our novel isobaric tag, labeling mechanism, and 4-plex quantitation is shown in Scheme 3. The proposed design of the first set of isotopic dimethylated amino acid reagents for isobaric tagging are based on the following considerations: (1) Methods of coupling amino acid to peptides are well established; (2) Intensive reporter ion (dimethylated leucine a1 ion) is generated upon tandem MS fragmentation;5, 28 (3) Isotopic leucines are commercially available which will simplify the preparation of isotopic reporter ions.

Scheme 3.

General structure of dimethyl leucine isobaric tags is shown in (A). Formation of new peptide bond at N-terminus or ε-amino group of the lysine side-chain and isotope combination of isobaric tags are illustrated in (B). Quantitation of 4-plex isobarically labeled peptide is illustrated in (C).

Isobaric DiLeu Reagent Synthesis

Labels 117 and 118 (molecular weight=163) are isobaric after one step synthesis. Labels 115 and 116 (molecular weight=161) need 18O exchange to incorporate an 18O atom to carbonyl group to make all four labels isobaric. The dimethylation of leucines gave yields from 85–90% after purification by column chromatography. Yield of 18O exchange experiment was monitored by direct infusion of the labels on Waters Micromass QTOF mass spectrometer. Since after 24h no unexchanged DiLeu was detected in direct infusion experiment, we concluded that the 18O exchange rate was quantitative. Because the molar ratio between H218O to DiLeu is 224:1 (i.e., large excess of H218O was used), the exchange was pushed to completion despite that the purity of H218O is 96%. In general, the yield limiting step was the column purification. Because dimethylated leucine was retained strongly on the normal phase flash column, though a large amount of solvent (MeOH/CH2Cl2) was used to elute the compound off the column, the recovery of DiLeu was not quantitative. Our tags are very stable until activation for labeling. The very first compound we synthesized was two and a half years old and still works great.

Synthesis of DiLeu Amine Reactive Triazine Ester

Due to the high polarity of dimethylated leucine, reaction conditions worked for tert-Butyloxycarbonyl (Boc) protected leucine N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) ester activation, but did not work on DiLeu NHS ester activation. DMTMM was reported as an in situ condensation reagent for polar substrates with good yield.38–41 Our experiment showed that DiLeu can be activated by DMTMM/NMM in DMF and time course study indicated this reaction reached equilibrium in an hour. Several reactions suggesting a two-step condensation by DMTMM were reported previously.42–44 Briefly, the acid moiety was first activated with DMTMM/NMM and followed by addition of amines to the reaction mixture. Purification of activated ester was not necessary according to these publications. The activated ester was not purified in our experiments presented here. The quick activation time and absence of purification step in ester preparation provide the advantage of easy access of our labeling reagents. Each label can be freshly activated before use. Preliminary stability test of the activated ester was carried out as following: The same stock solution was used to label neural tissue extract aliquot a week apart. The freshly made ester showed effective labeling of our sample, a week later double the amount was needed to achieve decent labeling. We suspected that the formed active ester was hydrolyzed over time due to the trace amount of water produced in DiLeu activation process. After adding MgSO4 to the freshly made labeling solution to dry the labeling solution, the stock labeling solution showed the same labeling efficiency after a week. In general, the activated ester was suitable for labeling for approximately a week when stored in −20°C refrigerator with MgSO4.

Peptide Labeling Efficacy

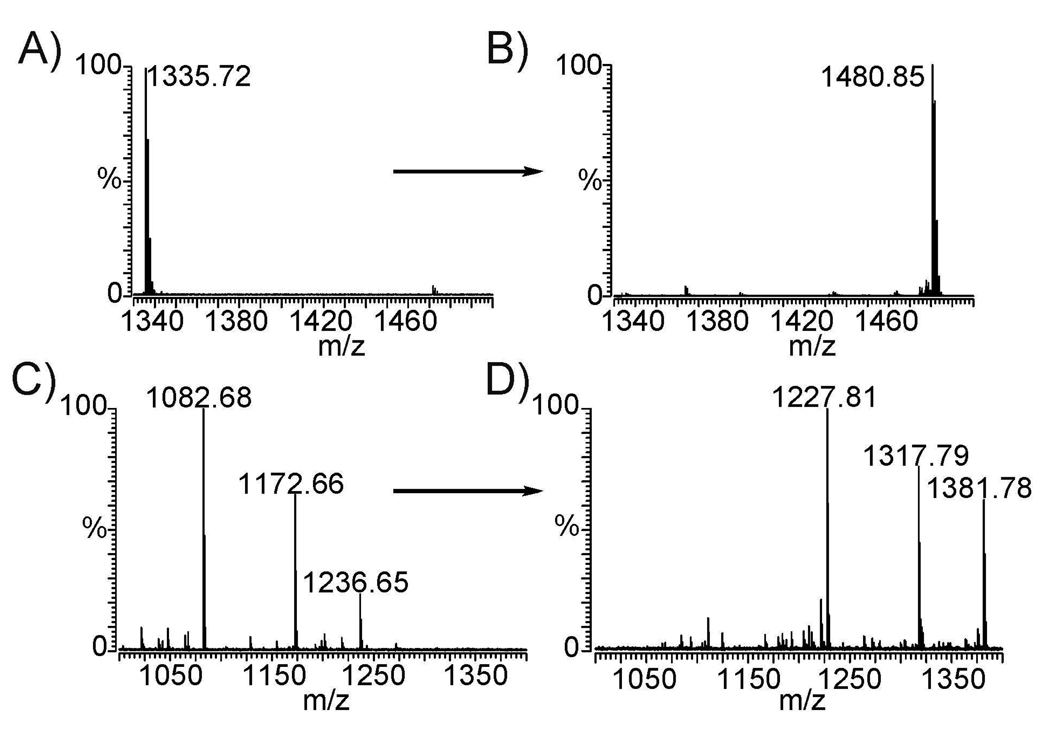

MALDI-FTICR MS detection of labeled neuropeptide allatostatin I (AST-I) showed quantitative labeling within 1 hour (Fig. 1A, B). Calmodulin dependent protein kinase substrate analog (CaM, m/z 1082.68) was used to test the labeling efficiency of secondary amine. Quantitative conversions of CaM and other two unknown impurities (m/z 1172.66, 1236.65) were detected by MALDI-FTICR MS (Fig. 1C, D). Complete labeling of proline residue at the N-terminus of CaM peptide demonstrates high reactivity of triazine ester to amine groups. LC-MS/MS analysis of iTRAQ and DiLeu labeled BSA tryptic peptides indicated complete labeling within the same amount of time. LC-MS/MS data was analyzed by X! Tandem database search using searching parameters described in the Experimental Section. Twenty-three peptides were identified as unique BSA tryptic peptides with log(e)<-2 cutoff for both iTRAQ and DiLeu labeled samples. Fourteen of these peptides (~61%) were found overlapping (Table 1). Both iTRAQ and DiLeu showed the same sequence coverage at ~43%. The tyrosine side reaction and unlabeled N-termini or lysine side chain were explored. A minimal degree (<3%) of tyrosine derivatization and unlabeled N-termini were found in DiLeu labeled peptides and reaction with serine or threonine was not observed. In Table 1, the database search results showed that among the labeled tryptic peptides only LCVLHEK was not completely labeled at its N-terminus and the remaining peptides were completely labeled. Equivalent protein sequence coverage and minimal side reactions demonstrate that DiLeu reagents have comparable performance and labeling efficiency to iTRAQ reagents.

Figure 1.

MALDI-FTICR mass spectrum of neuropeptide allatostatin (AST)-I (APSGAQRLYGFGL-NH2) (A) before and (B) after DiLeu labeling, and CaM (PLRRTLSVAA-NH2) (C) before and (B) after DiLeu labeling, 145.1 Da mass shift is produced for each incorporated label.

Table 1.

Identified iTRAQ and DiLeu Labeled BSA Tryptic Peptides by X! Tandem

| Sequence | iTRAQa | DiLeub | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | HLVDEPQNLIK | −4.4 | −5.1 |

| 2 | YICDNQDTISSK* | −3.7 | −6.3 |

| 3 | LKPDPNTLCDEFKADEK* | −5.2 | −6.2 |

| 4 | LKPDPNTLCDEFK* | −4.4 | −5.1 |

| 5 | LVNELTEFAK* | −7.0 | −6.0 |

| 6 | MPCTEDYLSLILNR* | −6.4 | −6.3 |

| 7 | LVTDLTK* | −2.3 | −2.3 |

| 8 | AEFVEVTK | −2.3 | −2.1 |

| 9 | ECCHGDLLECADDR | −4.8 | −6.9 |

| 10 | RPCFSALTPDETYVPK* | −3.0 | −4.8 |

| 11 | LGEYGFQNALIVR* | −7.5 | −5.7 |

| 12 | QTALVELLK* | −4.1 | −3.8 |

| 13 | FYAPELLYYANK* | −2.5 | −5.6 |

| 14 | KVPQVSTPTLVEVSR | −4.9 | −5.0 |

| 15 | ECCDKPLLEK | −6.5 | n/a |

| 16 | KQTALVELLK | −5.3 | n/a |

| 17 | DDPHACYSTVFDK | −4.7 | n/a |

| 18 | VHKECCHGDLLECADDR | −4.1 | n/a |

| 19 | EACFAVEGPK | −4.1 | n/a |

| 20 | TVMENFVAFVDK | −3.5 | n/a |

| 21 | EYEATLEECCAK | −3.3 | n/a |

| 22 | VPQVSTPTLVEVSR | −3 | n/a |

| 23 | SLHTLFGDELCK | −2.7 | n/a |

| 24 | CCAADDKEACFAVEGPK | n/a | −10.4 |

| 25 | TCVADESHAGCEK | n/a | −9.6 |

| 26 | DAIPENLPPLTADFAEDKDVCK | n/a | −5.6 |

| 27 | DAFLGSFLYEYSR | n/a | −4.7 |

| 28 | LCVLHEK | n/a | −2.9 |

| 29 | GACLLPK | n/a | −2.5 |

| 30 | QNCDQFEK | n/a | −2.5 |

| 31 | ATEEQLK | n/a | −2.4 |

| 32 | NECFLSHK | n/a | −2.1 |

Note: a and b: Log(e) value indicates the confidence of identified peptide, the lower the value the higher confidence for peptide identification.

Un-fragmented reporter group intensity higher than the reporter ions labeled by iTRAQ.

In our experiment, the molar ratio of DMTMM to DiLeu is 1.1:1. The remaining DMTMM is very likely to react with other carboxylates of peptides to form the peptide triazine ester in subsequent tagging reactions. However, since the activated DiLeu trizazine ester is very reactive to amine group, when activated DiLeu is mixed with peptides, coupling reaction takes place immediately. Most peptides can be completely labeled by DiLeu within an hour. The side reaction of DMTMM to the carboxylates of labeled peptides can be hydrolyzed by adding 0.1%FA solution. The trace amount of unlabeled peptides can also be activated by remaining DMTMM and undergo a peptide cyclization reaction. The cyclization reaction was investigated using high concentration peptide standards (10−4M). However, no cyclized peptide was detected in our quantitative experiment.

Another way to eliminate this problem is to purify the activated ester before labeling by adding 1 mL of CH2Cl2 followed by 100uL of H2O to the ester activation mixture, after vortex, the mixture is then separated into two phases, the upper phase is water and DMF, the lower phase is CH2Cl2. Since DMTMM and NMM are water soluble, removing water and DMF phase can completely remove the excessive amount of DMTMM and NMM and leave only activated ester in CH2Cl2 phase. CH2Cl2 can be easily blow dried under nitrogen.

Fragmentation of Labeled Peptides

Besides equivalent labeling efficiency as iTRAQ reagents, DiLeu reagents produced better fragmentation and higher reporter ion intensities than iTRAQ reagents for labeled tryptic peptides, thereby offering improved confidence for peptide identification and reliable quantitation. There were 14 overlapping labeled peptides between iTRAQ and DiLeu labeling (first 14 peptides in Table 1), 9 out of 14 individual peptides labeled by DiLeu had higher scores than iTRAQ labeled ones. Also the sum of scores of those 14 peptides were −63 (iTRAQ) and −71.2 (DiLeu), respectively. DiLeu labeling showed ~13% increase of confidence for peptide identification than iTRAQ labeling.

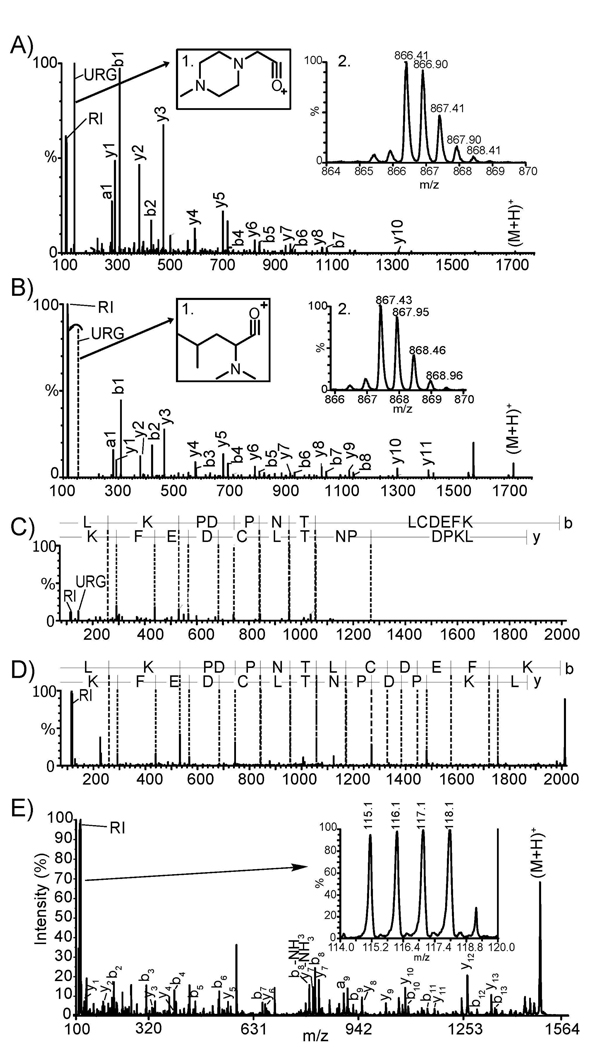

To directly compare the labeled peptide fragmentation and reporter ion intensities by these DiLeu and iTRAQ labeling, de novo sequencing of all those 14 common peptides using PepSeq software was performed. The de novo sequencing results indicated that DiLeu 4-plex labeled peptides showed more intense reporter ions than iTRAQ 4-plex labeled tryptic peptides (Figs. 2A and B), resulting from a complete fragmentation and production of DiLeu reporter ions. It is worth noting that even after 20% increase of collision energy the peptides labeled by iTRAQ still had unfragmented reporter group (m/z 145.1, general structure shown in Fig. 2A inset 1) whereas none unfragmented DiLeu reporter group (m/z 146.1, general structure shown in Fig. 2B inset 1) was found in DiLeu labeled peptide spectra at normal collision energy. Ten out of those fourteen iTRAQ labeled peptides marked with asterisks had un-fragmented reporter groups with intensities higher than the reporter ions indicating less efficient fragmentation of iTRAQ reporter group (Table 1). In contrast, the DiLeu reporter ions have significantly higher S/N ratios than iTRAQ reporter ions due to complete fragmentation of DiLeu reporter groups. Production of abundant reporter ions is likely to contribute to more robust and reliable quantitation. Improved fragmentation of DiLeu labeled peptide is shown in Figure 2. A complete set of y ions and more balanced fragmentation ions were observed in a DiLeu labeled peptide (Figs. 2B and 2D), whereas fewer y ions were seen for iTRAQ labeled peptides (Fig. 2A and 2C). The fragmentation efficiency of DiLeu labeled neuropeptide allatostatin I (AST-I) was also tested on a MALDI-TOF/TOF MS instrument. The tandem MS spectrum exhibited abundant reporter ions and complete y ion series with typical collisional induced dissociation parameter setting (Fig. 2E). Here, abundant reporter ion counts induced by normal collisional energy on the MALDI TOF/TOF platform offer an advantage of reliable quantitation while maintaining sequence-specific fragmentation information using DiLeu labeling reagents, indicating applicability to a wide range of MS platforms.

Figure 2.

ESI QTOF de novo sequenced MS2 spectrum BSA tryptic peptide (YICDNQDTISSK) labeled by (A) iTRAQ 4-plex, (B) DiLeu 4-plex. General structures of un-fragmented reporter group (URG) of iTRAQ (inset 1 in A) and DiLeu (inset 1 in B) are shown. Peptides were isobarically labeled by iTRAQ (inset 2 in A) and DiLeu (inset 2 in B). (C) Low reporter ion (RI) intensities, presence of URG and incomplete fragments of b and y ions are shown for iTRAQ 4-plex labeled BSA tryptic peptide (LKPDPNTLCDEFK). (D) Intense RI, absence of URG and complete set of b and y ions are shown for the same peptide labeled by 4-plex DiLeu labeling. (E) MALDI TOF/TOF MS2 spectrum of AST-I labeled by DiLeu 4-plex showing quantitation capability in inset.

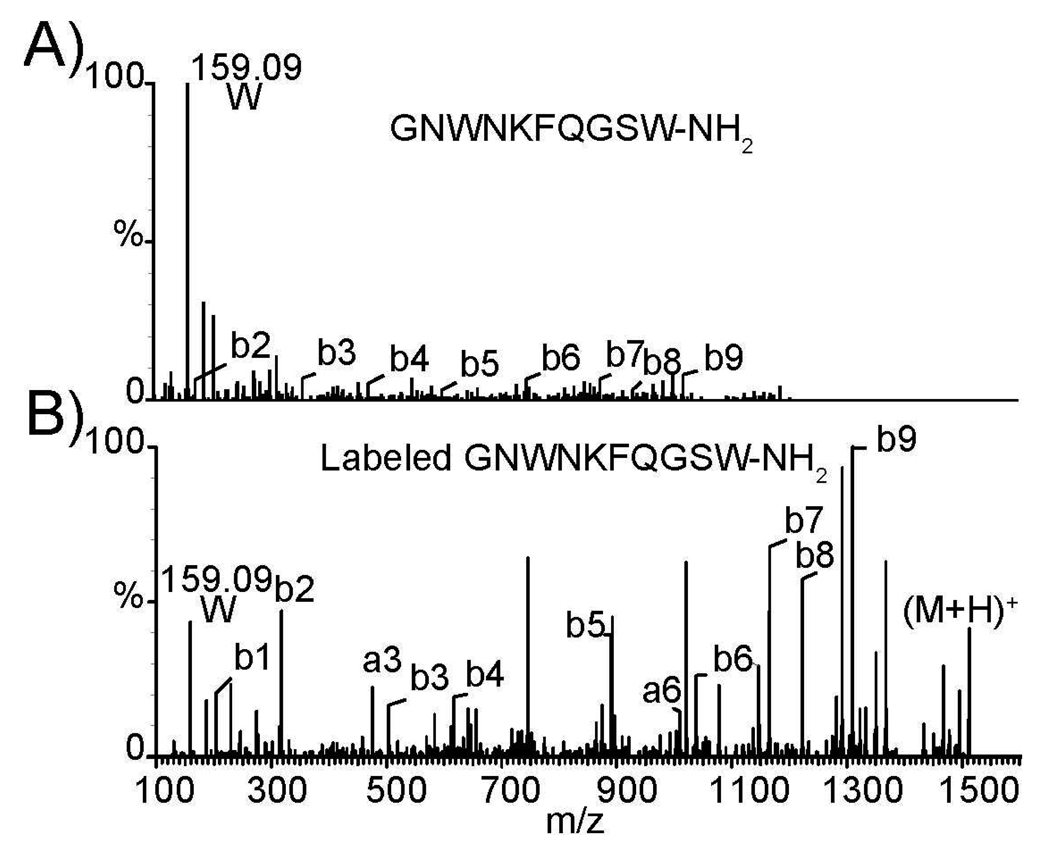

The enhanced fragmentation has proven to be very helpful in determining the crustacean neuropeptides sequence due to the current lack of database for crustacean model organisms. De novo sequencing is the main tool to interpret neuropeptide MS2 spectra. DiLeu labeling also improves neuropeptide MS2 fragmentation. Figure 3 compares the MS2 spectra of a B-type allatostatin (AST-B) neuropeptide (GNWNKFQGSW-NH2) before and after DiLeu labeling acquired on an ESI QTOF mass spectrometer. As shown, b ions are substantially enhanced after labeling, which facilitates improved de novo sequencing of neuropeptides. Greater confidence in peptide identification using DiLeu labeling reagents demonstrates that DiLeu provides an attractive alternative reagent for iTRAQ reagent by providing enhanced fragmentation.

Figure 3.

ESI QTOF tandem MS fragmentation (A) before and (B) after DiLeu labeling of B-type allatostatin neuropeptide (GNWNKFQGSW-NH2)

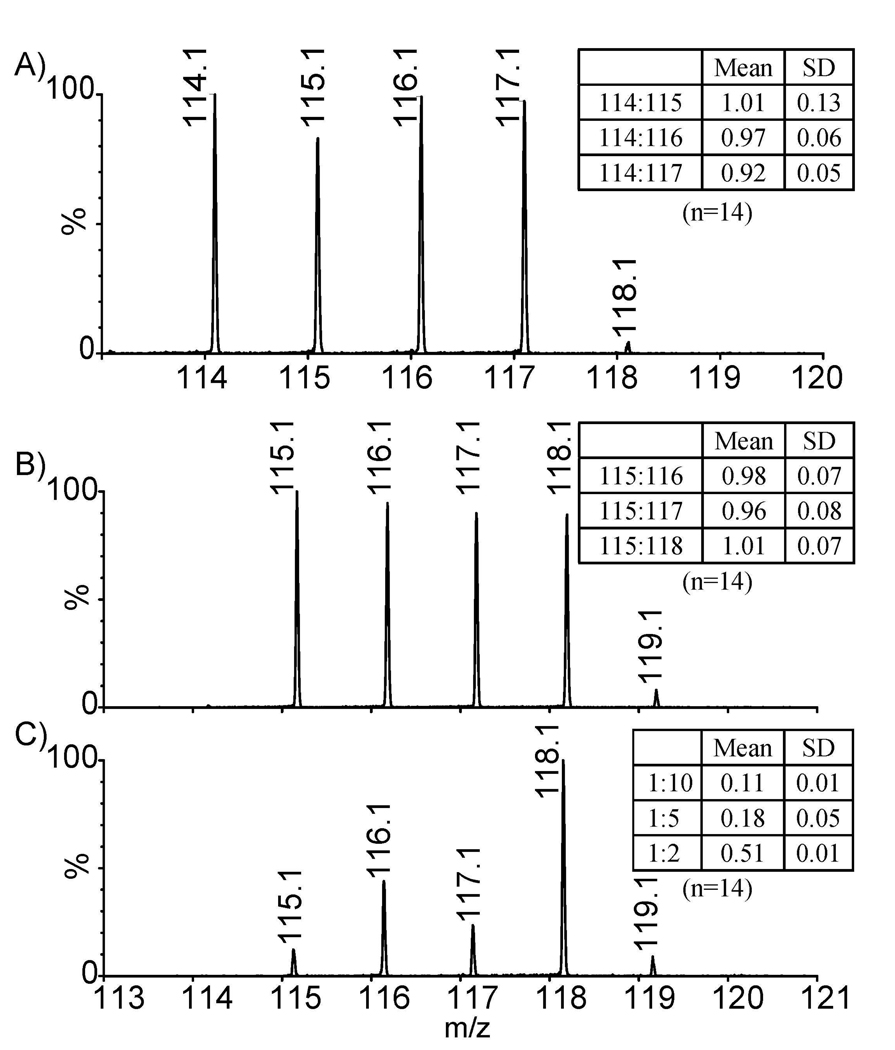

Peptide and Protein Quantitation and Reproducibility

Representative aliquots (1:1:1:1) enable a quantitative comparison of BSA tryptic peptides labeled by either iTRAQ or DiLeu reagents. The results are shown in Figure 4A and 4B with mean values and standard deviations shown in insets. Fourteen overlapping BSA tryptic peptides were selected to calculate peptide ratios. The means and standard deviations of peptide ratios were used to quantify BSA. Furthermore, relative quantitation of the same peptide labeled at ratio 1:5:2:10 by DiLeu was also investigated for linear dynamic range of quantitation (Figure 4C). Quantitation reproducibility was tested in triplicates. Ratios of each quantitation are listed in Table 2. DiLeu shows robust quantitation and excellent reproducibility and has comparable performance as that of commercial iTRAQ reagents (shown in Figure 4 and Table 2). It is worth noting, however, that the average cost of a set of 4-plex DiLeu labels for 100 µg of protein tryptically digested peptide is estimated to be about ten dollars, whereas the same amount of iTRAQ reagents costs more than two hundred dollars. The reduced cost for reagent production coupled with excellent accuracy and reproducibility for quantitation makes the new DiLeu reagents an attractive alternative for protein and peptide quantitation for biological samples.

Figure 4.

Quantitation of BSA tryptic peptide (YICDNQDTISSK) using A) iTRAQ, B) DiLeu. Quantitative dynamic range of the same peptide is illustrated in (C). Means and standard deviations of BSA are shown in insets.

Table 2.

Reproducibility of DiLeu Labeled BSA tryptic fragments (N=14)

| Mean | SD | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Replicate1 | 115:116 | 0.98 | 0.07 |

| 115:116 | 0.96 | 0.07 | |

| 115:116 | 0.93 | 0.05 | |

| Replicate2 | 115:117 | 0.96 | 0.08 |

| 115:117 | 0.96 | 0.08 | |

| 115:117 | 0.98 | 0.07 | |

| Replicate3 | 115:118 | 1.01 | 0.07 |

| 115:118 | 0.93 | 0.08 | |

| 115:118 | 0.97 | 0.06 | |

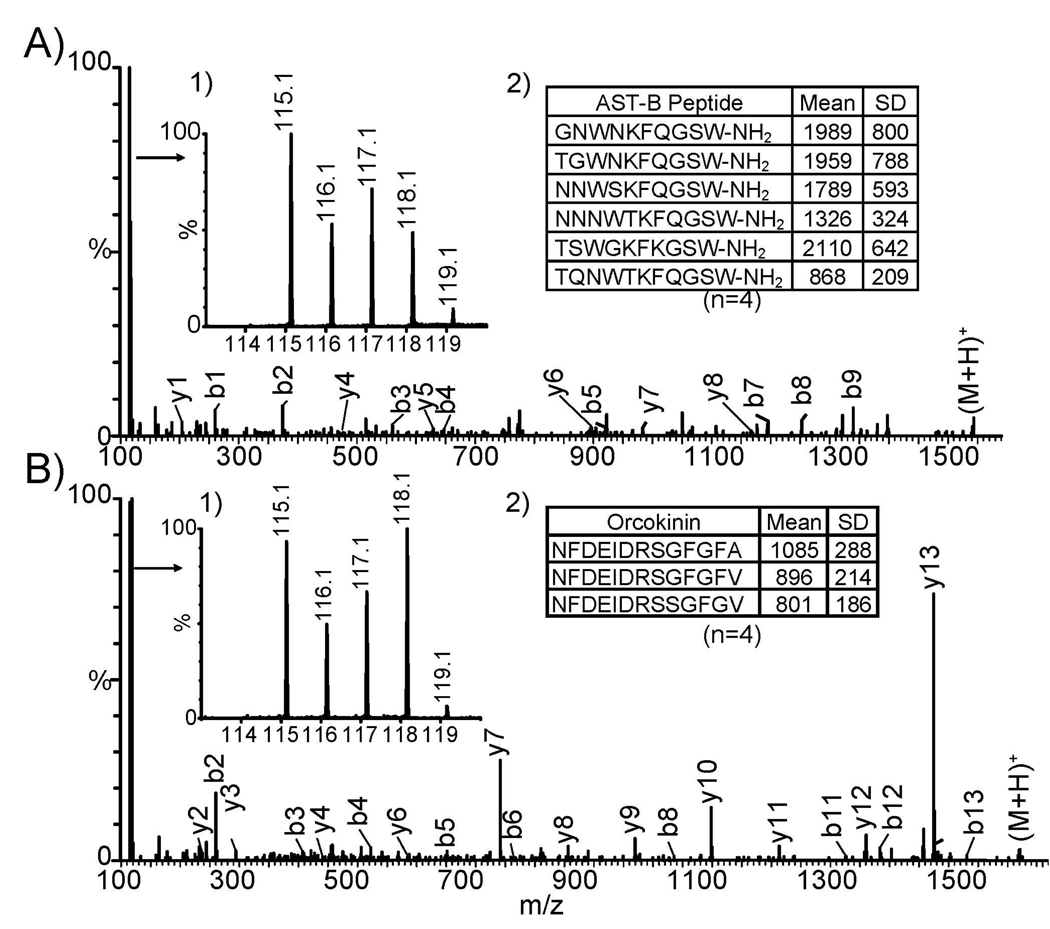

Crab Neuropeptide Identification and Quantitation

In order to evaluate individual variability in neuropeptide expression, we employed 4-plex DiLeu reagents to label the pericardial organ (PO) extracts from four blue crabs, Callinectus sapidus. A total of 131 MS2 spectra were acquired in a single LC/MS/MS run and about 95% of the spectra contained DiLeu 4-plex signature reporter ions, indicating that DiLeu reagents can efficiently label neuropeptides present in complex tissue extracts. Six B-type allatostatins (AST-B) and three orcokinins were de novo sequenced in their labeled forms. B-type AST peptides exhibit characteristic sequence motifs of W(X)6Wamide, where × represents variable amino acid residues. Since the first report of AST-B in crustacean,45 numerous studies have documented the wide-spread presence of this novel class of peptides in various decapod crustaceans and have shown the inhibitory effects that these peptides have on the crustacean pyloric neural circuits.46–49 Here, using the DiLeu labeling reagent reported for the first time, the identification of six AST-B peptides in a commercially important crustacean species, Callinectus sapidus, is demonstrated. Figure 5A shows a representative de novo sequencing spectrum from AST-B. Similarly, Figure 5B shows a representative tandem mass spectrum of an orcokinin peptide in C. sapidus, another highly conserved neuropeptide family found in numerous crustaceans with myotropic activities.50–53 Four biological replicates were performed and reporter ion counts were compared, showing a maximum of two-fold expression differences for several isoforms in both neuropeptide families (Fig. 5 insets 1 in A and B). Means and standard deviations (SD) of reporter ion counts were calculated across four samples (Fig. 5 insets 2 in A and B). These preliminary results suggest individual animal variability and their potential impact on neuropeptide quantitation at different physiological states.

Figure 5.

ESI QTOF MS2 spectra of neuropeptides from the pericardial organs tissue extract of blue crab C. sapidus. (A) DiLeu 4-plex labeled B-type allatostatin neuropeptide (GNWNKFQGSW-NH2), and (B) orcokinin neuropeptide (NFDEIDRSGFGFA). Relative abundance changes for neuropeptide expression levels among different animals are highlighted in inset tables.

Deuterium Atom Effect of Labeled Peptides

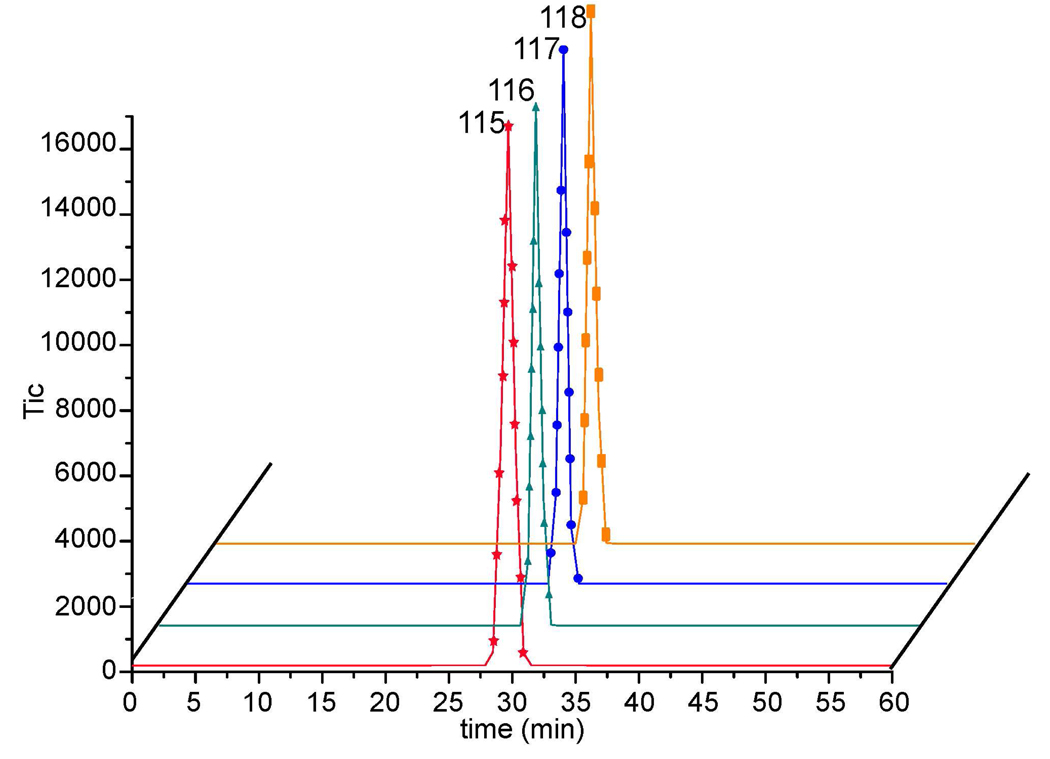

It is known that deuterium affects the retention time of small- to intermediate-sized peptides in reversed-phase chromatography.54 Obviously, different retention times of these isobarically labeled peptides will affect the accuracy of quantitation if not properly adjusted. However, it was reported that the deuterium effect can be minimized to acceptable values by grouping deuterium atoms around polar functional groups which both minimizes their interaction with the stationary phase and reduces the isotope effect.6 Using a relatively small number of deuterium atoms in labeling reagents should also help to minimize the isotope effect. In our 4-plex DiLeu tags, the greatest difference of deuterium atoms exists between tags 115 and 118 (4 deuterium atoms located around the more polar dimethylated amine group). The increased polarity of amine group offsets the small deuterium number difference in our tags. Therefore, peptides labeled with the four DiLeu tags showed negligible differences in retention time on RP chromatography as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

DiLeu 4-plex labeled AST-I peptides show negligible retention time difference (29.65 min) of extracted ion chromatograms.

CONCLUSIONS

We have successfully developed a novel class of isobaric tandem mass tagging reagents based on isotope-encoded dimethylated amino acid (Leucine), DiLeu. Several features of the four-plex DiLeu reagents are summarized below: First, our reagents maintain the isobaric quantitation features present in the iTRAQ reagents, with comparable performance and greatly reduced cost. This makes the DiLeu tandem MS tags a more affordable tool for routine quantitation and methodology development as compared to commercially available reagents. Second, all four reagents can be easily synthesized from commercially available isotope reagents in regular analytical lab settings. Labels 117 and 118 require only one step synthesis and labels 115 and 116 require two steps of synthesis. Third, our methodology offers new opportunities to develop an array of natural amino acid based tagging reagents including mass-difference and isobaric tags. Besides multiplex quantitation, these dimethylated amino acid tags also promote enhanced fragmentation, thereby allowing more confident protein identification from tryptic peptides and de novo sequencing of neuropeptides. Fourth, quantitation data processing can be easily adopted from freely available software. We have demonstrated the utility of these novel DiLeu labeling reagents for protein quantitation and neuropeptide sequencing from complex tissue extracts. Future work will be conducted to extend this methodology to large-scale quantitative proteomics and peptidomics as well as other amino acid-based isobaric tagging strategies for multiplexed quantitation and sequencing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors wish to thank Dr. Junhua Wang for helpful discussion and Robert Sturm in the Li Laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript. We are grateful to the UW School of Pharmacy Analytical Instrumentation Center for access to the MALDI FTMS instrument. The authors also thank Dr. Amy Harms and Dr. Mike Sussman at the University of Wisconsin-Biotechnology Center Mass Spectrometry Facility for access to the MALDI-TOF/TOF instrument. This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health through grant 1R01DK071801 and the National Science Foundation CAREER Award (CHE-0449991). L.L. acknowledges an Alfred P. Sloan Research Fellowship and a Vilas Associate Award.

REFERENCES CITED

- 1.Ong S-E, Mann M. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:252–262. doi: 10.1038/nchembio736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gygi SP, Rist B, Gerber SA, Turecek F, Gelb MH, Aebersold R. Nature Biotechnology. 1999;17:994. doi: 10.1038/13690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li J, Steen H, Gygi SP. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2003;2:1198–1204. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M300070-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hansen KC, Schmitt-Ulms G, Chalkley RJ, Hirsch J, Baldwin MA, Burlingame AL. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2003;2:299–314. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M300021-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ong S-E, Blagoev B, Kratchmarova I, Kristensen DB, Steen H, Pandey A, Mann M. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2002;1:376–386. doi: 10.1074/mcp.m200025-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang R, Sioma CS, Thompson RA, Xiong L, Regnier FE. Anal Chem. 2002;74:3662–3669. doi: 10.1021/ac025614w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsu JL, Huang SY, Chow NH, Chen SH. Anal Chem. 2003;75:6843–6852. doi: 10.1021/ac0348625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsu JL, Huang SY, Chen SH. Electrophoresis. 2006;27:3652–3660. doi: 10.1002/elps.200600147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morano C, Zhang X, Fricker LD. Anal Chem. 2008;80:9298–9309. doi: 10.1021/ac801654h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boersema PJ, Aye TT, Van Veen TAB, Heck AJR, Mohammed S. Proteomics. 2008;8:4624–4632. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson A, Schafer J, Kuhn K, Kienle S, Schwarz J, Schmidt G, Neumann T, Hamon C. Anal Chem. 2003;75:1895–1904. doi: 10.1021/ac0262560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dayon L, Hainard A, Licker V, Turck N, Kuhn K, Hochstrasser DF, Burkhard PR, Sanchez J-C. Anal Chem. 2008;80:2921–2931. doi: 10.1021/ac702422x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ross PL, Huang YN, Marchese JN, Williamson B, Parker K, Hattan S, Khainovski N, Pillai S, Dey S, Daniels S, Purkayastha S, Juhasz P, Martin S, Bartlet-Jones M, He F, Jacobson A, Pappin DJ. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2004;3:1154–1169. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400129-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeng D, Li S. Chem. Commun. 2009:3369–3371. doi: 10.1039/b906335h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ji C, Guo N, Li L. J Proteome Res. 2005;4:2099–2108. doi: 10.1021/pr050215d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ji C, Li L, Gebre M, Pasdar M, Li L. J Proteome Res. 2005;4:1419–1426. doi: 10.1021/pr050094h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ji C, Li L. J Proteome Res. 2005;4:734–742. doi: 10.1021/pr049784w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang S-Y, Tsai M-L, Wu C-J, Hsu J-L, Ho S-H, Chen S-H. Proteomics. 2006;6:1722–1734. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ji C, Lo A, Marcus S, Li L. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:2567–2576. doi: 10.1021/pr060085o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ji C, Zhang N, Damaraju S, Damaraju VL, Carpenter P, Cass CE, Li L. Analytica Chimica Acta. 2007;585:219–226. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2006.12.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo K, Ji C, Li L. Anal Chem. 2007;79:8631–8638. doi: 10.1021/ac0704356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang P, Lo A, Young JB, Song JH, Lai R, Kneteman NM, Hao C, Li L. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:3403–3414. doi: 10.1021/pr9000477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raijmakers R, Berkers CR, de Jong A, Ovaa H, Heck AJR, Mohammed S. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:1755–1762. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800093-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Synowsky SA, van Wijk M, Raijmakers R, Heck AJR. J Mol Biol. 2009;385:1300–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lemeer S, Jopling C, Gouw J, Mohammed S, Heck AJR, Slijper M, den Hertog J. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:2176–2187. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800081-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khidekel N, Ficarro SB, Clark PM, Bryan MC, Swaney DL, Rexach JE, Sun YE, Coon JJ, Peters EC, Hsieh-Wilson LC. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:339–348. doi: 10.1038/nchembio881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rogers LD, Foster LJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:18520–18525. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705801104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aye TT, Mohammed S, van den Toorn HWP, van Veen TAB, van der Heyden MAG, Scholten A, Heck AJR. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:1016–1028. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800226-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boersema PJ, Raijmakers R, Lemeer S, Mohammed S, Heck AJR. Nat. Protocols. 2009;4:484–494. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fu Q, Li L. Anal Chem. 2005;77:7783–7795. doi: 10.1021/ac051324e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fu Q, Li L. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2006;17:859–866. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fu Q, Li L. Rapid Comm Mass Spectrom. 2006;20:553–562. doi: 10.1002/rcm.2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DeKeyser SS, Li L. Analyst. 2006:281–290. doi: 10.1039/b510831d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xiang F, Fu Q, Li L. 56th ASMS Conference Poster; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hsu JL, Huang SY, Shiea JT, Huang WY, Chen SH. J Proteome Res. 2005;4:101–108. doi: 10.1021/pr049837+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murphy RC, Clay KL. Methods in Enzymology. 1990;193:338–348. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)93425-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boehm A, Putz S, Altenhofer D, Sickmann A, Falk M. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:214. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kamiński ZJ. Synthesis. 1987:917–920. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaminski ZJ, Kolesinska B, Kolesinska J, Sabatino G, Chelli M, Rovero P, Blaszczyk M, Glowka ML, Papini AM. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:16912–16920. doi: 10.1021/ja054260y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kunishima M, Kawachi C, Iwasaki F, Terao K, Tani S. Tetrahedron Letters. 1999;40:5327–5330. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kunishima M, Kawachi C, Monta J, Terao K, Iwasaki F, Tani S. Tetrahedron. 1999;55:13159–13170. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garrett CE, Jiang X, Prasad K, Repicˇ O. Tetrahedron Letters. 2002:4161–4165. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bandgar BP, Pandit SS. Tetrahedron Letters. 2003;44:3855–3858. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kunishima M, Yoshimura K, Morigaki H, Kawamata R, Terao K, Tani S. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:10760–10761. doi: 10.1021/ja011660m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fu Q, Kutz KK, Schmidt JJ, Hsu YW, Messinger DI, Cain SD, de la Iglesia HO, Christie AE, Li L. J Comp Neurol. 2005;493:607–626. doi: 10.1002/cne.20773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ma M, Chen R, Sousa GL, Bors EK, Kwiatkowski MA, Goiney CC, Goy MF, Christie AE, Li L. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2008;156:395–409. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fu Q, Tang LS, Marder E, Li L. J Neurochem. 2007;101:1099–1107. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ma M, Bors EK, Dickinson ES, Kwiatkowski MA, Sousa GL, Henry RP, Smith CM, Towle DW, Christie AE, Li L. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2009;161:320–334. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ma M, Wang J, Chen R, Li L. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:2426–2437. doi: 10.1021/pr801047v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li L, Pulver SR, Kelley WP, Thirumalai V, Sweedler JV, Marder E. J Comp Neurol. 2002;444:227–244. doi: 10.1002/cne.10139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pascual N, Castresana J, Valero ML, Andreu D, Belles X. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;34:1141–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Skiebe P, Dreger M, Borner J, Meseke M, Weckwerth W. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 2003;49:851–871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stangier J, Hilbich C, Burdzik S, Keller R. Peptides. 1992;13:859–864. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(92)90041-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang R, Sioma CS, Wang S, Regnier FE. Anal Chem. 2001;73:5142–5149. doi: 10.1021/ac010583a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]