Abstract

VDAC1 is a key component of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. To initiate apoptosis and certain other forms of cell death, mitochondria become permeable such that cytochrome c and other pre-apoptotic molecules resident inside the mitochondria enter the cytosol and activate apoptotic cascades. We have shown recently that VDAC1 interacts directly with never-in-mitosis A related kinase 1 (Nek1), and that Nek1 phosphorylates VDAC1 on Ser193 to prevent excessive cell death after injury. How this phosphorylation regulates the activity of VDAC1, however, has not yet been reported. Here we use atomic force microscopy (AFM) and cytochrome c conductance studies to examine the configuration of VDAC1 before and after phosphorylation by Nek1. Wild type VDAC1 assumes an open configuration, but closes and prevents cytochrome c efflux when phosphorylated by Nek1. A VDAC1-Ser193Ala mutant, which cannot be phosphorylated by Nek1 under identical conditions, remains open and constitutively allows cytochrome c efflux. Conversely, a VDAC1-Ser193Glu mutant, which mimics constitutive phosphorylation by Nek1, remains closed by AFM and prevents cytochrome c leakage in the same liposome assays. Our data provide a mechanism to explain how Nek1 regulates cell death by affecting the opening and closing of VDAC1.

Keywords: Nek1, VDAC1, apoptosis, atomic force microscope

INTRODUCTION

Intrinsic apoptotic pathways that respond to cytotoxic stress, including DNA damage, activate a hierarchical series of caspases that disassemble cells without inciting inflammation in bystanding cells. Permeabilization of mitochondria is seminal to the regulation of cell death induced by cytotoxic or genotoxic stress [1]. Among the most important proteins released from mitochondria is cytochrome c. One established paradigm, supported by abundant evidence, holds that cytochrome c exits through a permeability transition pore composed of the outer mitochondrial membrane protein VDAC1 [2], the inner mitochondrial membrane protein ANT (adenine nucleotide translocator), and the inner membrane associated protein cyclophylin D [2–4]. A more recently proposed paradigm suggests that the primary function of VDAC in pro-apoptotic conditions is to regulate ATP flux by closure rather than by opening, such that cytochrome c release from the mitochondrial intermembrane space occurs as part of a general rupture of the outer membrane rather than passage specifically through open VDAC [5]. In either case, cytochrome c initiates the cascade of events that results in mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis. After its release into cytoplasm, cytochrome C complexes with Apaf-1 (apoptosis protease activating factor) and cleaves a series of caspases that ultimately dismantle the cell by breaking down cell-cell contacts, cytoskeletal elements, and nuclear structures [6]. The mitochondrial transition pore is affected by low intracellular pH, a relative deficiency of ATP, and Ca2+ overload [4], as well as by the balance between pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic members of the Bcl-2 family of proteins, which bind to VDAC1 [7, 8]. To date, however, relatively little is known about how individual components of the transition pore, including VDAC, change their conformation when post-translationally modified by specific cytoplasmic proteins, like kinases.

We have recently shown that the VDAC1 is regulated by specific phosphorylation, on serine residue 193, by never-in-mitosis A (NimA) related kinase 1 (Nek1). In the basal state and in response to injury that includes DNA damage, Nek1 phosphorylates VDAC1 to limit mitochondrial cell death [9]. Nek1 is a mammalian homologue of the NimA, a stress protein kinase in Aspergillus and in other fungi that responds to DNA damage, regulates the G2-M phase transition, and keeps chromosome transmission to daughter cells faithfully [10, 11]. We have also shown that Nek1 protein, like its fungal counterpart, but in unique ways, is likewise important in mammalian cells for efficient DNA damage responses and for proper check-point activation [12, 13].

In this report, we use atomic force imaging and cytochrome C efflux to demonstrate the consequences of Nek1’s phosphorylation of VDAC1: it regulates the channel’s opening and closing, and its conductance of cytochrome c. Our data support a direct role for VDAC1 in conducting cytochrome c to initiate the mitochondrial-mediated cell death cascade.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

Human HK2 human proximal renal tubular epithelial cells were obtained from American Type Tissue Collection (Rockville, MD) and cultured in recommended media containing 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics.

Antibody production and purification

Details of the production and determination of the specificity of the anti-Nek1 antibodies have already been reported [9, 12]. Normal rabbit IgG was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Site-directed Nekl mutagenesis

A Quick-Change kit (Stratagene, LaJolla, CA) was used to generate the VDAC1-S193A and VDAC1-S193E mutant cDNAs, as previously reported [9].

Production and purification of VDAC1 fusion proteins

GST-VDAC1 proteins were expressed using a bacterial system. To obtain soluble fusion proteins, cells were incubated at 37C and then the protein was induced by IPTG at either 37°, 25° or 16°C. VDAC1 (wild type), VDAC1-S193A, and VDAC1-S193E cDNAs were individually fused in-frame to glutathione S-transferase (GST) or streptadivin binding protein (SBP) expression constructs. The fusion proteins were expressed in BL21 competent E. coli and purified using glutathione sepharose or strepadivin sepharose beads. After washing with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), the GST-VDAC1 proteins were eluted with glutathione and SBP-VDAC1 proteins were eluted with biotin. After removing the free glutathione or biotin, the purified proteins were then stored at 4°C.

Kinase assays

Immunopurified Nekl was used as kinase source as previously described [9]. Purified GST-VDAC1 proteins were incubated in separate reactions with immunopurified Nekl in a kinase buffer, or in a mock reaction containing pre-immune IgG immunoprecipitates instead of immunopurified Nekl. The kinase reactions were carried out in a total volume of 30 µl, with 20 µl of immune complexes and 3 µg of GSTVDAC1 (or mutants) in the presence of 3 µCi of γ-32P-ATP. After incubation for 30 minutes at 37°C, equal volumes of SDS sample buffer with EDTA were added to final concentration of 2 mM for the kinase reactions prior to the AFM and liposome transport studies.

Imaging with atomic force microscopy (AFM)

The GST-VDAC1 fractions after immune kinase reactions were kept on ice. Two microliters of purified GST-VDAC1, diluted in 20 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.5) to a final concentration of 0.1 mg/ml, were deposited on a freshly cut mica surface and mounted on a wet chamber of a Nanoscope IIIa atomic force microscope (Digital Imaging, Veeco Instruments, Inc., Woodbury, NY). Imaging was performed as previously described [14]. Standard plain fit and flattening options provided with the NanoScope IIIa software were applied in the height mode to obtain multiple views to show channel pores. All experiments were repeated at least twice. Two different observers assessed the open or closed state of >200 individual VDAC1 channels. Similar expression and purification strategies were used for the GSTVDAC1-S193A and S193E mutants, which were subjected to the same analysis. Detailed measurements of individual channels for base and outside pore sizes was accomplished with Digital Imaging software.

Liposome transport assays

Purified cytochrome c was purchased from Sigma. A very small (MW 509) Oregon Green®-488 fluorochrome label was conjugated to cytochrome c according to instructions described in the labeling kit (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). To make relatively large and uniform liposomes, a sonication-freeze-thaw method was used. 500 mg of phospholipid mixture (soybean Type II-S) was dispersed and sonicated in 10 ml of buffer containing 10 mM K3PO4, 50 mM KC1, 20 mM Hepes, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.5. Following sonication, 100 µl of lipid mixture was mixed with purified GST-VDAC1, GST-VDAC1-S193A, or GST-VDAC1-S193E fusion protein and Oregon Green® 488-conjugated cytochrome c, then subjected to three freeze-thaw cycles (2 minutes freeze in liquid N2 and 30 minutes thaw at room temperature). One hour after the freeze-thaw cycles, the export of cytochrome c from individual liposomes was observed and photographed using a fluorescence microscope. More than 400 individual liposomes were assessed in duplicate or triplicate experiments to determine whether labeled cytochrome c was inside or outside. Mouse erythrocyte membranes were prepared from 200 µl of blood [15] and used instead of liposomes for some of the transport assays.

RESULTS

Purification of recombinant VDAC1

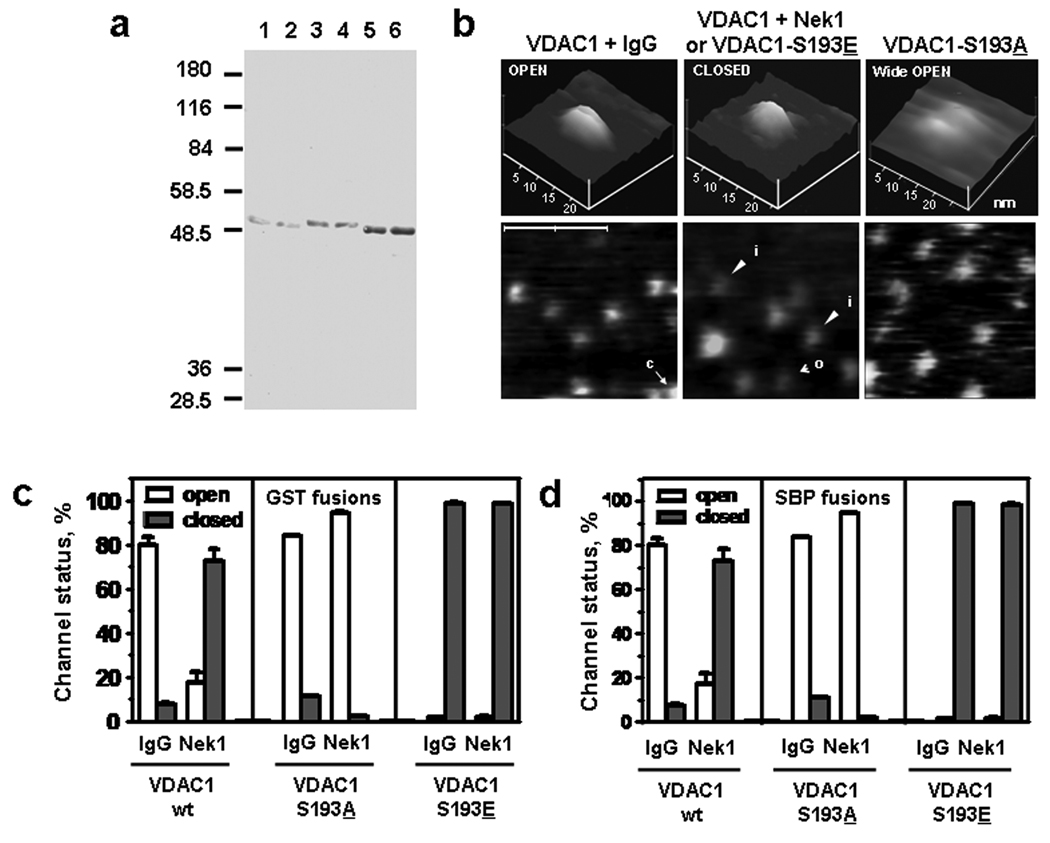

In order to characterize VDAC1’s biochemical activity, we first produced pure wild-type and key mutant forms of it. We cloned the human VDAC1 gene and fused it to a GST tag for purification [9]. In order to avoid any denature-renature processes [16–18] and to assure that the resultant tagged VDAC1 proteins retained their native configurations, we used low culture temperature to obtain soluble forms of VDAC1 directly. GST-VDAC1 was almost completely insoluble when induced and cultured at 25–37°C, but approximately 15–20% of the protein became soluble when the culture was induced and incubated at 16°C (Supplemental Figure S1a and b) [19, 20]. With this increased yield of soluble VDAC1, we were able to purify the soluble fractions in good amounts. Identical conditions were used to produce wild type GST-VDAC1 and with the key serine 193 residue mutated to a negatively charged amino acid (glutamic acid), to mimic constitutive phosphorylation (VDAC1-S193E), and with residue 193 changed to alanine and therefore unable to be phosphorylated by Nek1 (VDAC1-S193A) [9]. We then used the purified GST-VDAC1 proteins as substrates in immune kinase studies. After phosphorylation of complexes immunoprecipitated from HK2 cells with either anti-Nek1 antibody or normal rabbit (or mouse) IgG, the GST-VDAC1 proteins were subjected to additional purification to remove any contaminants. All three GST-VDAC1 proteins migrated as single, silver stained bands in SDS-PAGE (Figure 1a). They were therefore deemed pure.

Figure 1. Phosphorylation of VDAC1 on S193 by Nek1 keeps the channel closed.

(a) Pure GST-VDAC1 proteins. Each of the three proteins was phosphorylated by immune complexes from HK2 cell lysates. Specific and non-specific complexes were precipitated by pre-immune IgG (lanes 1, 3, 5) or by anti-Nek1 (lanes 2, 4, 6). Immune complexes were then used as the kinases for phosphorylating equivalent amounts of purified GST-VDAC1 (lanes 1, 2), GST-VDAC1-S193A (lanes 3, 4), and VDAC1-S193E (lanes 5, 6). After the kinase reactions, VDAC1 proteins were purified, separated by SDS-PAGE, and stained with silver. Note that the proteins migrated as single bands, and that the GST-VDAC1-S193A mutant migrated more slowly than the other two proteins. (b) Examples of purified GST-VDAC1 imaged by atomic force microscopy. Top view field fragments 200 × 200 nm are presented alongside enlarged side plots of single representative particles (panels 20 nm × 20 nm). The particles imaged in field fragments were identified as “open” (labeled “o”) or “closed” (labeled “c”) by the method presented in Figure 2. Note the open conformation without phosphorylation by Nek1 (the two leftmost panels), and closed conformation after phosphorylation by Nek1 (two middle panels). The GST-VDAC1-S193A mutant channels had larger openings than wild type GST-VDAC1 channels before phosphorylation by Nek1 immune complexes (see Figure 3), consistent with the slightly slower migration of the purified channels by SDS-PAGE in Figure 1c. (c, d) Quantification of the open or closed state of VDAC1, VDAC1-S193A, and VDAC1-S193E mutants by AFM. Different tags (GST in c, SBP in d) used in purification of the VDAC1 fusion proteins resulted in nearly identical data. Each histogram represents mean percentage ± standard errors from 2–3 separate experiments and >200 images of individual channel particles in each experiment.

Examination of VDAC1 by AFM

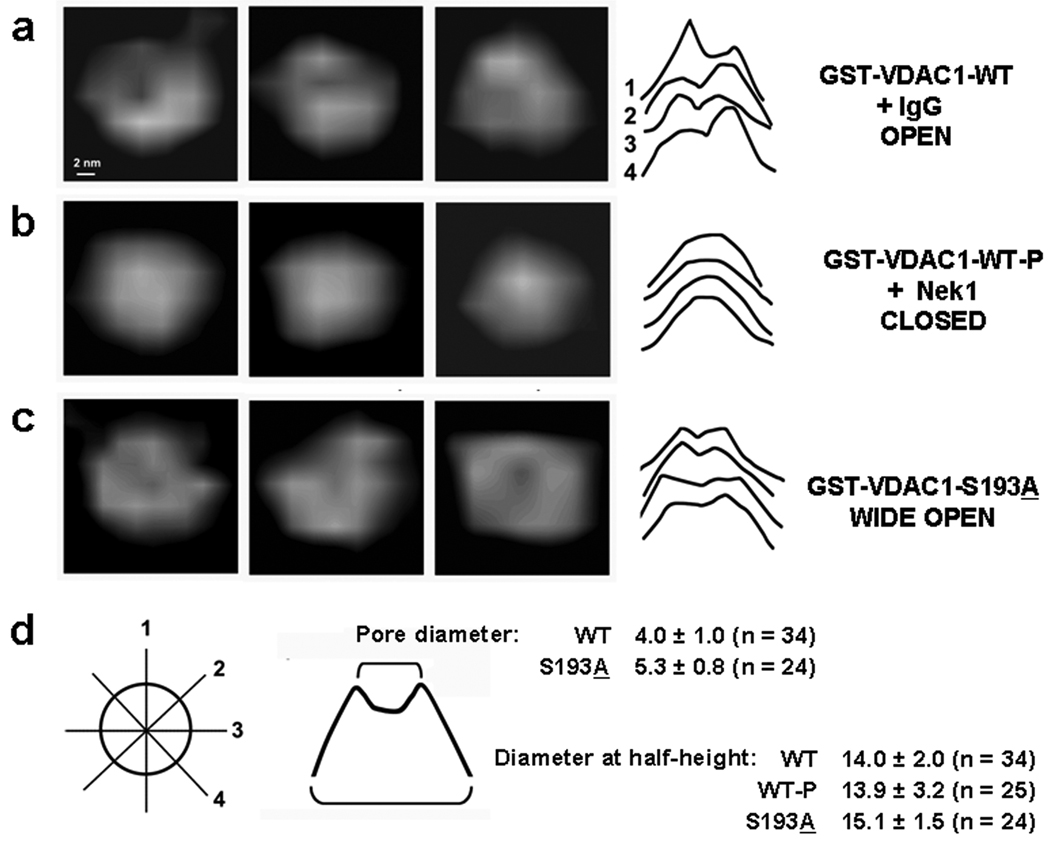

To explore in more detail the molecular consequences of the Nek1-VDAC1 kinase-substrate interaction, we used atomic force microscopy to examine GST-VDAC1, GST-VDAC1-S193A, and GST-VDAC1-S193E, with or without phosphorylation by Nek1 immune complexes. Individual channels could be assessed by AFM for their open or closed status (Figure 1). When only nonspecific immune complexes were included in the kinase reaction, most of the wild type GST-VDAC1 channels were open; but when Nek1 immune complexes were used, most of these channels were closed. In contrast, almost all of the GST-VDAC1-S193A mutant channels were open (more wide open even than wild type GST-VDAC1 unphosphorylated by Nek1), and all of the GST-VDAC1-S193E channels were tightly closed, whether Nek1 was included in the kinase reaction or not. Detailed analysis of many individual channels by AFM (Figure 2) showed outside dimensions of the pores in wild type, unphosphorylated VDAC1 to be slightly larger than dimensions reported recently using NMR and x-ray crystallographic data [17, 18], but not much different than previous reports based on electron microscopic and AFM measurements [21–23]. The pore dimension of the VDAC1-S193A mutant, which cannot be phosphorylated by Nek1 and which is always open, was even larger and is migrated slower than wild-type and S193E mutant channels on SDS-PAGE (Figure 1c). The open channels should be large enough to conduct cytochrome c, the largest dimension of which is approximately 3.5 nm, in either oxidized or reduced state and with its associated water molecules [24–26].

Figure 2. GST-VDAC1 channels can assume open, closed, or wide open configurations.

Since nearly all (>95%) the imaged particles were rounded, cylinder-shaped, and of uniform height, we assumed that they attached to the mica substrate “standing” (top-view). The representative images of single particles are presented for (a) GST-VDAC1 without phosphorylation (WT + non-specific IgG); (b) GST-VDAC1 phosphorylated by Nek1 immune complexes (WT-P); (c) GST-VDAC1-S193A (mutant). Individual channels were sorted into closed or open conformations according to the qualitative feature of the shape of their median sections, as demonstrated in (d). All four sections for the first particle from the left in each group are presented in (a–c). The vast majority of the sections represented either “cone” or “crater” shapes regardless the direction of the section, direction of the scan, apparent resolution, density of the sample, or ionic strength of the buffer (all within the conditions used). The “cones” were classified as closed, the “craters” as open. Among thousands of particles more than 90% were classified according to the criteria, with the remaining 10% being deformed by scanning artifacts or in presumed “lying/side view” orientation. The average diameters of all channels, measured in their half-height, were comparable (d). The average diameter of openings of mutant particles (d) was significantly larger than WT (2-tailed t-test, p <0.0001). Mean diameters in nm and standard deviations are shown.

Conductance of cytochrome c through VDAC1 in liposomes and erythrocyte membranes

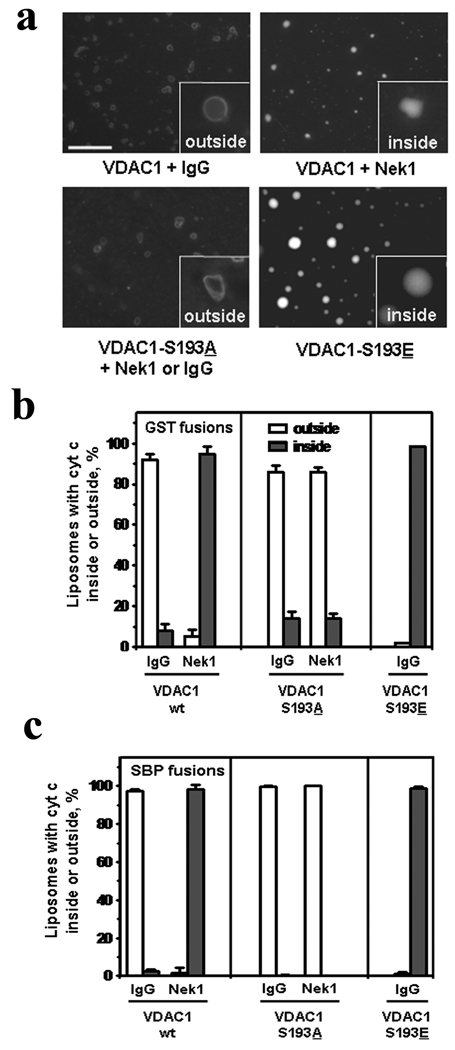

To confirm that open GST-VDAC1 and GST-VDAC1-S193A channels can allow cytochrome c to pass through, we performed transport assays for efflux of labeled cytochrome c through VDAC1 channels inserted into liposome membranes [8]. Results were entirely consistent with those observed for individual channels examined by AFM: phosphorylation of wild type VDAC1 by Nek1 kept the channels closed and cytochrome c inside the liposomes, but had no effect on the VDAC1-S193A channels, which remained open and allowed cytochrome c efflux with or without phosphorylation by Nek1. VDAC1-S193E channels, which mimic constitutive phosphorylation on serine residue 193, always kept cytochrome c inside, with or without phosphorylation by Nek1 (Figure 3a and b).

Figure 3. Cytochrome c transport assays in liposomes.

The same purified GST-VDAC1 and GST-VDAC1 mutant proteins used for AFM analyses were incorporated into liposomes containing fluorescence-tagged cytochrome c. (a) Liposomes were then analyzed by microscopy to determine whether the labeled cytochrome c remained inside or leaked outside. Bar = 50 µm for low power photomicrographs, 5 µm for insets. (b) Quantification of cytochrome c efflux from individual liposomes. Each histogram represents mean percentage ± s.e.m. from 3 separate experiments and >1000 individual liposomes in each experiment. (c) Identical liposome transport assays using recombinant VDAC1 proteins tagged with a different purification tag, streptavidin (SBP). Histograms here represent means ± s.e.m. from 2 separate experiments and >400 individual liposomes in each experiment.

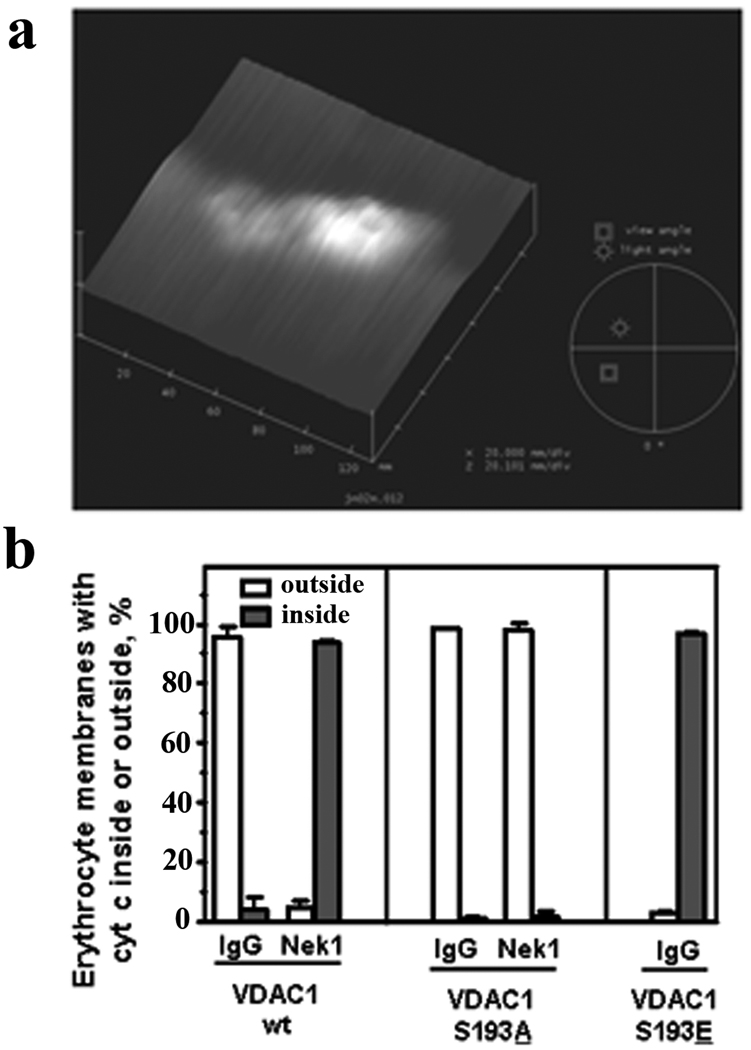

The N-terminal GST tags on the recombinant VDAC1 proteins did not create any significant artifacts with regard to VDAC1 channel structure or function, since nearly identical results were obtained in AFM images and liposome transport assays when VDAC1 proteins were purified with a different and even smaller streptavidin binding protein (SBP) tag (Figure 3c). The VDAC1 fusion proteins, even with different tags and when examined by AFM after insertion into liposomes (Figure 4a), assumed their native barrel-type channel structures [17, 18], and were able to conduct cytochrome c when open.

Figure 4. Further analysis of wild type VDAC1 and VDAC1-S193 mutants by AFM and cytochrome c transport assays.

(a) Example of SBP-VDAC1-S193A mutant channels inserted into liposomes and examined by AFM in the dry “height” mode. The liposome surface contained many plateaus and valleys, but the open, barrel structured GST-VDAC1-S193A channels inserted like buoys in water, perpendicular to the surface of the lipid membrane. Several open channels can be identified, with the highest one most clearly visible. (b) SBP-VDAC1 constructs were also incorporated into mouse erythrocyte membranes (lipid bilayers) [15] for similar assays. Histograms represent means ± s.e.m. from 2 separate experiments and >400 individual channels assessed for each condition.

We also confirmed that the cytochrome c transport assays in artificial liposomes were not specious. Similar assays with GST- or SBP-VDAC1 constructs inserted into freshly isolated mammalian red blood cell membranes, which have intact, biological, lipid bilayers containing cholesterol, were nearly identical to those in the liposomes (Figure 4b). Taken together, the AFM and liposome/erythrocyte transport data show that phosphorylation of VDAC1 on serine 193 keeps VDAC1 closed to prevent efflux of cytochrome c, and reinforce with channel imaging and functional assays the concept that we reported previously, that regulation of VDAC1’s open-closed status by Nek1 may be crucial for prevention of aberrant, mitochondria-mediated cell death after injury [9].

DISCUSSION

We have already determined that the biochemical and mechanistic observations reported here are relevant biologically to the phenotypes that result from a naturally occurring Nek1 mutation, by examining mitochondria and apoptosis in cells from Nek1-deficient mice [9]. The so-called kat2J (kidneys-anemia-testis) spontaneous mutant mice develop pleiotropic defects, most notably growth retardation and polycystic kidney disease (PKD), and they die prematurely [27]. The kat2J mutation results in early truncation of Nek1, eliminating all of the coiled-coil domains as well as part of the N-terminal kinase domain [28]. Cells from Nek1kat2J −/− mice express no detectable Nek1 protein and are hypersensitive to the lethal effects of DNA-damaging radiation [13]. We have also shown that the Nek1-dependent phosphorylation of VDAC1 on serine 193 is biologically important, since ectopic overexpression of the constitutively closed VDAC1-S193E mutant transiently protects Nek1 −/− cells from aberrant apoptosis after DNA damage [9].

Nek1 is involved early in the DNA damage response. Its kinase activity is increased and a portion of cellular Nek1 relocalizes from cytoplasm and mitochondria to nuclear sites of DNA damage, within minutes after gamma irradiation. Nek1-deficient cells are markedly more sensitive to the lethal effects of DNA damage compared to cells expressing functional Nek1 [13]. Nek1 expression is also upregulated in renal tubular epithelial cells after ischemic injury, before the cells either undergo frank apoptosis or necrosis, or before they repair the injury ([29] and manuscript in preparation).

Our data showing that unphosphorylated, wild-type VDAC1 and the VDAC1-S193A mutant remain widely open to allow cytochrome c efflux, and that the phosphorylated, wild-type VDAC1 and the VDAC1-S193E mutant remain closed, strongly support a direct role for VDAC1 in conducting cytochrome c in initiating the mitochondrial-mediated cell death cascade. They demonstrate furthermore and for the first time how a specific kinase, Nek1, regulates VDAC1 channel activity. The serine 193 residue that Nek1 phosphorylates on VDAC1 is predicted to be at a crucial site at the junction between a C-terminal transmembrane domain and a putative cytoplasmic protein binding domain, such that its phosphorylation would have a significant impact on the configuration of the barrel-like channel formed by VDAC1 [30, 31]. Two recent reports that used NMR and x-ray crystallography to characterize recombinant human VDAC1 structure in detail have identified a helical protrusion within the VDAC1 pore [17, 18]. This protrusion is comprised by N-terminal amino acids and is thought to be less stable than other regions of the VDAC1 barrel structure, such that it may switch between different conformations to control voltage gating [17]. It is possible that the serine 193 phosphorylation of VDAC1 by Nek1 affects movement of the helical protrusion to control closing of the channel pore. It is also possible that Nek1 phosphorylation affects dimerization or oligomerization of VDAC1 [23]; such a property could also account for the large size of the pores we examined by AFM, which had characteristics of dimers or trimers. Finally, we were careful to use relatively physiologic conditions (pH 7.2 to 7.6) in our AFM and cytochrome c conductance assays. In preliminary studies, we found that changes in pH outside of the physiologic range influenced the open or closed conformation of GST-VDAC1 by AFM, irrespective of Nek1 phosphorylation (data not shown), and therefore we standardized conditions at pH 7.5. Many reported studies have used much more alkaline pH, which could influence or prevent the opening and closing of native VDAC1, as well as its oligomerization or association with other proteins.

CONCLUSION

We have shown previously that mitochondrial transition pores are easily opened in the absence of functional Nek1 [9, 13], which seems in the basal state to phosphorylate VDAC1 and keep it closed. AFM and cytochrome c transport assays showing here that the VDAC1-S193E mutant remains tightly closed, and thereby keeps cytochrome c from leaking out, add support to the notion that Nek1 regulates mitochondrial apoptosis through specific phosphorylation to affect the configuration of VDAC1. Our previous studies and the results presented here suggest that Nek1 may function in defense against oxidative cellular and/or DNA damage, and that relatively trivial environmental injury may lead to aberrant apoptosis in cells deficient in Nek1. Targeting Nek1 expression or the Nek1-VDAC1 interaction may be a novel way to prevent apoptosis after injury in normal cells or to enhance apoptosis in cells that overexpress Nek1.

Supplementary Material

Lowering culture temperature increases the fraction of soluble GST-VDAC1 fusion proteins. Coomassie blue-stained gel (a) and Western blot with anti-GST (b) from lysates separated by SDS-PAGE after at indicated temperature. Arrow marks GST-VDAC1, which migrates with an apparent molecular mass of approximately 50 kDa. For lane markers, T: total lysate, P: insoluble pellet, and S: soluble supernatant.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the PKD Foundation, the American Society of Nephrology, the National Kidney Foundation, and the NIH (RO1-DK067339) to Y.C.; a George M. O'Brien Kidney Research Center grant from the NIH to Y.C. (P50-DK061597, Hanna E. Abboud, Program Director); a postdoctoral fellowship from PKD Foundation to R.P; and a grant from the NIH to D.J.R. (RO1-DK61626).

Abbreviations used

- AFM

atomic force microscopy

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- GST

gultathione S transferase

- Nek1

never-in-mitosis A related kinase 1

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- SBP

streptavidin binding protein

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- VDAC

voltage dependent anion channel

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wang X. The expanding role of mitochondria in apoptosis. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2922–2933. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colombini M. Voltage gating in the mitochondrial channel, VDAC. J Membr Biol. 1989;111:103–111. doi: 10.1007/BF01871775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zoratti M, Szabo I. The mitochondrial permeability transition. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1241:139–176. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(95)00003-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crompton M. The mitochondrial permeability transition pore and its role in cell death. Biochem J. 1999;341:233–249. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rostovtseva TK, Bezrukov SM. VDAC regulation: role of cytosolic proteins and mitochondrial lipids. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2008;40:163–170. doi: 10.1007/s10863-008-9145-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slee EA, Harte MT, Kluck RM, et al. Ordering the cytochrome c-initiated caspase cascade: hierarchical activation of caspases-2, -3, -6, -7, -8, and -10 in a caspase-9-dependent manner. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:281–292. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.2.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crompton M. Mitochondrial intermembrane junctional complexes and their role in cell death. J Physiol. 2000;529(Pt 1):11–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00011.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shimizu S, Narita M, Tsujimoto Y. Bcl-2 family proteins regulate the release of apoptogenic cytochrome c by the mitochondrial channel VDAC. Nature. 1999;399:483–487. doi: 10.1038/20959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Y, Craigen WJ, Riley DJ. Nek1 regulates cell death and mitochondrial membrane permeability through phosphorylation of VDAC1. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:257–267. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.2.7551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osmani SA, Pu RT, Morris NR. Mitotic induction and maintenance by overexpression of a G2-specific gene that encodes a potential protein kinase. Cell. 1988;53:237–244. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90385-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Osmani AH, McGuire SL, Osmani SA. Parallel activation of the NIMA and p34cdc2 cell cycle-regulated protein kinases is required to initiate mitosis in A. nidulans. Cell. 1991;67:283–291. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90180-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Y, Chen PL, Chen CF, et al. Never-in-mitosis related kinase 1 functions in DNA damage response and checkpoint control. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:3194–3201. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.20.6815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Polci R, Peng A, Chen PL, et al. NIMA-related protein kinase 1 is involved early in the ionizing radiation-induced DNA damage response. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8800–8803. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Osmulski PA, Gaczynska M. Atomic force microscopy reveals two conformations of the 20 S proteasome from fission yeast. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:13171–13174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.c901035199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bojesen IN, Bojesen E. Palmitate binding to and efflux kinetics from human erythrocyte ghost. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1064:297–307. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(91)90315-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Engelhardt H, Meins T, Poynor M, et al. High-level expression, refolding and probing the natural fold of the human voltage-dependent anion channel isoforms I and II. J Membr Biol. 2007;216:93–105. doi: 10.1007/s00232-007-9038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bayrhuber M, Meins T, Habeck M, et al. Structure of the human voltage-dependent anion channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:15370–15375. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808115105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hiller S, Garces RG, Malia TJ, et al. Solution structure of the integral human membrane protein VDAC-1 in detergent micelles. Science. 2008;321:1206–1210. doi: 10.1126/science.1161302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qing G, Ma LC, Khorchid A, et al. Cold-shock induced high-yield protein production in Escherichia coli. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:877–882. doi: 10.1038/nbt984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shirano Y, Shibata D. Low temperature cultivation of Escherichia coli carrying a rice lipoxygenase L-2 cDNA produces a soluble and active enzyme at a high level. FEBS Lett. 1990;271:128–130. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80388-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo XW, Smith PR, Cognon B, et al. Molecular design of the voltage-dependent, anion-selective channel in the mitochondrial outer membrane. J Struct Biol. 1995;114:41–59. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1995.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mannella CA, Forte M, Colombini M. Toward the molecular structure of the mitochondrial channel, VDAC. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1992;24:7–19. doi: 10.1007/BF00769525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goncalves RP, Buzhynskyy N, Prima V, et al. Supramolecular assembly of VDAC in native mitochondrial outer membranes. J Mol Biol. 2007;369:413–418. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.03.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berghuis AM, Brayer GD. Oxidation state-dependent conformational changes in cytochrome c. J Mol Biol. 1992;223:959–976. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90255-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dickerson RE, Kopka ML, Borders CL, et al. A centrosymmetric projection at 4A of horse heart oxidized cytochrome c. J Mol Biol. 1967;29:77–95. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(67)90182-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Louie GV, Brayer GD. High-resolution refinement of yeast iso-1-cytochrome c and comparisons with other eukaryotic cytochromes c. J Mol Biol. 1990;214:527–555. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90197-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vogler C, Homan S, Pung A, et al. Clinical and pathologic findings in two new allelic murine models of polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:2534–2539. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V10122534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Upadhya P, Birkenmeier EH, Birkenmeier CS, Barker JE. Mutations in a NIMA-related kinase gene, Nek1, cause pleiotropic effects including a progressive polycystic kidney disease in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:217–221. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Riley DJ, Achinger SG, Chen Y. Expression of Nek1 protein kinase during kidney development and after ischemic tubular injury (Abstract) J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:366A. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Casadio R, Jacoboni I, Messina A, et al. A 3D model of the voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) FEBS Lett. 2002;520:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02758-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Colombini M. VDAC: the channel at the interface between mitochondria and the cytosol. Mol Cell Biochem. 2004;256–257:107–115. doi: 10.1023/b:mcbi.0000009862.17396.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Lowering culture temperature increases the fraction of soluble GST-VDAC1 fusion proteins. Coomassie blue-stained gel (a) and Western blot with anti-GST (b) from lysates separated by SDS-PAGE after at indicated temperature. Arrow marks GST-VDAC1, which migrates with an apparent molecular mass of approximately 50 kDa. For lane markers, T: total lysate, P: insoluble pellet, and S: soluble supernatant.