Epac2 is a cAMP-regulated guanine nucleotide exchange factor (cAMP-GEF) that is proposed to mediate stimulatory actions of the second messenger cAMP on mouse islet insulin secretion. Here we have used methods of islet perifusion to demonstrate that the acetoxymethyl ester (AM-ester) of an Epac-selective cAMP analog (ESCA) penetrates into mouse islets and is capable of potentiating both first and second phases of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS). When used at low concentrations (1–10 µM), 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP-AM activates Rap1 GTPase but exhibits little or no ability to activate protein kinase A (PKA), as validated in assays of in vitro PKA activity (phosphorylation of Kemptide), Ser133 CREB phosphorylation status, RIP1-CRE-Luc reporter gene activity, and PKA-dependent AKAR3 biosensor activation. Since quantitative PCR demonstrates Epac2 mRNA to be expressed at levels ca. 5.3-fold greater than that of Epac1, available evidence indicates that Epac2 does in fact mediate stimulatory actions of cAMP on mouse islet GSIS.

Glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) from the islets of Langerhans is potentiated by glucagon-like peptide-1-(7–36)-amide (GLP-1), an incretin hormone released from entero-endocrine L-cells of the distal intestine in response to the ingestion of a meal.1–4 GLP-1 binds to a Class II G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) expressed on pancreatic β-cells,5 and it stimulates cAMP production,6 thereby potentiating stimulatory effects of glucose metabolism on islet insulin secretion.7–9 In view of the fact that GLP-1 exerts a blood glucose-lowering effect in type 2 diabetic subjects,1–4 it is of interest to identify the cAMP-regulated signal transduction pathways that are activated as a consequence of the binding of GLP-1 to its GPCR.10–12 In a recently published paper we reported a new technical advance that may further this goal and which involves the use of an acetoxymethyl ester of an Epac-selective cAMP analog (ESCA) designated as 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP-AM.13

Since GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1-R) activation raises levels of cAMP in β-cells, it was originally assumed that the insulin secretagogue action of this hormone resulted from its ability to activate protein kinase A (PKA). Unexpectedly, it was reported that there exists in β-cells a novel cAMP signaling mechanism that does not involve PKA but which instead involves the cAMP-regulated guanine nucleotide exchange factor (cAMP-GEF) designated as Epac2.14–26 Through the use of a cAMP analog that is a selective activator of Epac,27 it was reported that Epac activation stimulates β-cell mitochondrial ATP production,28 inhibits ATP-sensitive K+ channel (K-ATP) activity,23,25 promotes Ca2+ influx and the mobilization of intracellular Ca2+,17,18,22,24 while also “priming” secretory granules, thereby rendering them competent to undergo exocytosis.29–31 Subsequently, Seino and co-workers reported that Epac2 couples β-cell cAMP production to the activation of Rap1, a GTPase Seino found to play an essential role in the cAMP-dependent stimulation of insulin secretion.26 How Rap1 might stimulate insulin secretion is not yet fully understood, but we have proposed that it is explained by the ability of Epac2 to act through Rap1 to stimulate the activity of a novel phospholipase C-epsilon that is expressed in β-cells (Kelley GG, unpublished observations) and that couples cAMP production to phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) hydrolysis, protein kinase C (PKC) activation, and the generation of IP3, a Ca2+-mobilizing second messenger.32–34 It is important to note, however, that it has yet to be firmly established that Epac2 is of major importance to GLP-1 receptor signal transduction and β-cell stimulus-secretion coupling. In particular, it remains to be determined what the relative contributions of Epac2 and PKA are to the cAMP-dependent potentiation of GSIS. It is also not clear whether Epac2 and PKA act synergistically to stimulate islet insulin secretion, nor is it established whether the prosecretagogue action of Epac2 is contingent on PKA activation, or vice versa.

To more fully understand what role Epac2 might play in β-cell stimulus-secretion coupling, our laboratory was one of the first to assess potential insulin secretagogue properties of 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP. Although this ESCA is not an acetoxymethyl ester, it is a selective activator of the two isoforms of Epac known to exist (Epac1, Epac2).27,35,36 The selectivity with which 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP activates Epac proteins is a consequence of the incorporation of a 2'-O-methyl moiety on the ribose ring of cAMP, a modification that drastically reduces the affinity of this compound for PKA relative to its affinity for Epac.27,37 In studies of human β-cells we demonstrated that extracellularly-applied 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP acted independently of PKA to mobilize an intracellular source of Ca2+, thereby raising levels of cytosolic free Ca2+ ([Ca2+]c).18 Using electrophysiological methods of carbon fiber amperometry, we also found that 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP stimulated a brief burst of exocytosis in human β-cells, an action coincident with a transient increase of [Ca2+]c.18 Such findings seemed to be in accord with the prior study of Renstrom and co-workers in which cAMP was demonstrated to act in both a PKA-dependent and PKA-independent manner to stimulate exocytosis, as measured by an increase of membrane capacitance in mouse β-cells.38 Indeed, we concluded that an Epac2-mediated action of cAMP to stimulate exocytosis could explain one previous report in which cAMP-elevating agents were found to act independently of PKA to exert a time-dependent potentiation of GSIS.39 Thus, we were surprised to find that 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP exhibited no detectable ability to potentiate GSIS in mouse islets, as measured through the use of an insulin-specific radioimmunoassay.13

In retrospect it is notable that earlier published reports hinted at a potential complication associated with the use of 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP. It was reported that this ESCA failed to potentiate GSIS from mouse islets, even when tested at a concentration of 250 µM.40 However, a stimulation of insulin secretion was observed in response to 50 µM 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP when rat islets were permeabilized with alpha-toxin,41 a procedure that allows access of 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP to the intracellular compartment of β-cells. Furthermore, direct application of 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP to the cytosol of β-cells by use of the patch clamp technique resulted in a potentiation of depolarization-induced exocytosis, as determined by the measurement of membrane capacitance. 29 Thus, it may be concluded that there exists a permeability barrier, one that limits access of 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP to the cytosol of β-cells, but that is not present in cell types in which extracellularly-applied 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP exerts its effects.34,37,42,43 Evidently, this permeability barrier allows small amounts of extracellularly-applied 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP to enter β-cells, thereby explaining why a brief burst of exocytosis can be measured when using electrophysiological techniques that afford high temporal resolution.18

It should be noted that there exists an alternative explanation concerning why 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP has little or no efficacy in conventional radioimmunoassays of islet insulin secretion. Using two-photon extracellular polar-tracer (TEP) imaging techniques, Kasai and co-workers reported that 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP stimulated the exocytosis of small diameter secretory vesicles from mouse β-cells, whereas it failed to stimulate exocytosis of large diameter dense core vesicles.44 In contrast, the naturally occurring second messenger cAMP stimulated the exocytosis of large diameter dense core vesicles, and this effect was blocked by Rp-cAMPS, an inhibitor of PKA activation. Since large dense core vesicles, not small vesicles, are the source of secreted insulin, it was concluded that it is PKA that is the principal signal transducer supporting stimulatory effects of cAMP on insulin secretion.44 This conclusion is supported by additional published findings.45–50

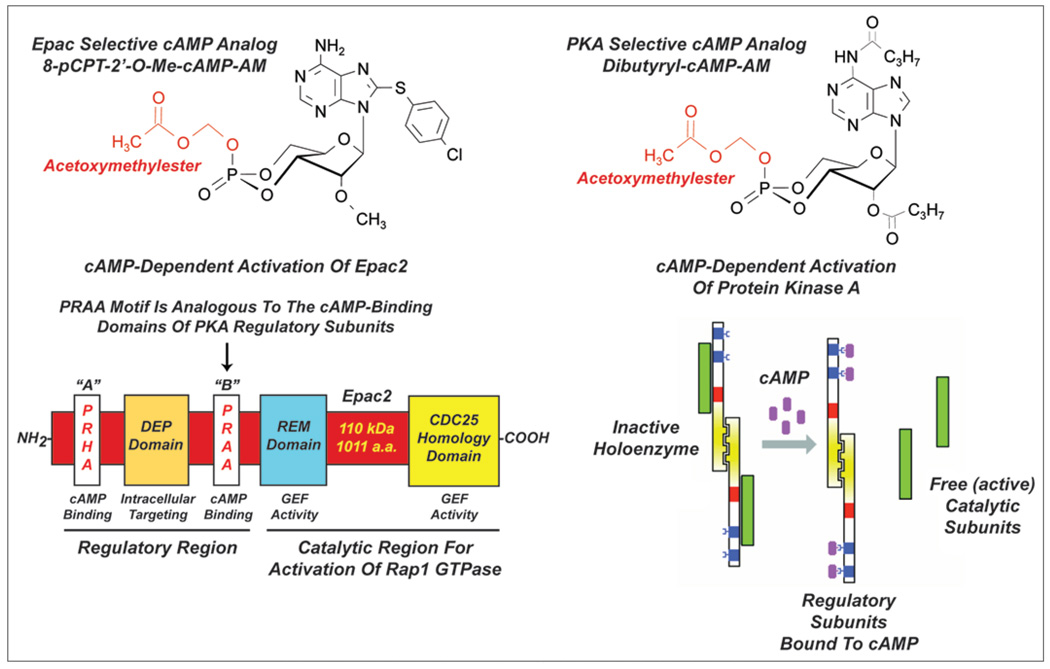

With this summarized information in mind we decided to evaluate potential insulin secretagogue properties of a newly developed cAMP analog that gains access to the cytosol of β-cells in an unimpeded manner. This cAMP analog is 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP-AM (Fig. 1). It is an acetoxymethyl ester (AM-ester) of 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP and it is highly lipophilic, gaining access to the cytosol in an inactive “pro-drug” form where it is activated by cytosolic esterases that hydrolytically remove the AM-ester moiety.51 In side-by-side comparisons with 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP, we demonstrated that 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP-AM was ca. 500-fold more potent as an activator of the cAMP biosensor Epac1-camps expressed in rat INS-1 cells, as expected if this ESCA gains ready access to the cytosol.13 Furthermore, as expected for a selective Epac activator, 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP-AM stimulated insulin secretion from INS-1 cells, an effect still measurable after treatment of these cells with 3 µM of the PKA inhibitor H-89.13 This secretagogue action of 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP-AM was not reproduced by the non-AM ester of 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP, thereby demonstrating that a permeability barrier preventing entry of the ESCA most likely exists in this cell type. Similarly, we found that 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP failed to stimulate insulin secretion from mouse islets, whereas 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP-AM was effective.13

Figure 1.

Acetoxymethyl esters of Epac and PKA selective cAMP analogs. 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP-AM (top left) is hydrolyzed to 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP and binds primarily to the high-affinity cAMP binding domain of Epac2 (bottom left). This binding activates the CDC25 homology domain that is responsible for the catalysis of guanyl nucleotide exchange on Rap1. Dibutyryl cAMP-AM (top right; also known as N6-2'-DB-cAMP) is hydrolyzed to dibutyryl-cAMP and then to monobutyryl-cAMP which binds to the regulatory subunits of the PKA holoenzyme (bottom right). This binding induces dissociation of the holoenzyme, thereby releasing catalytic subunits with serine/threonine protein kinase activity.

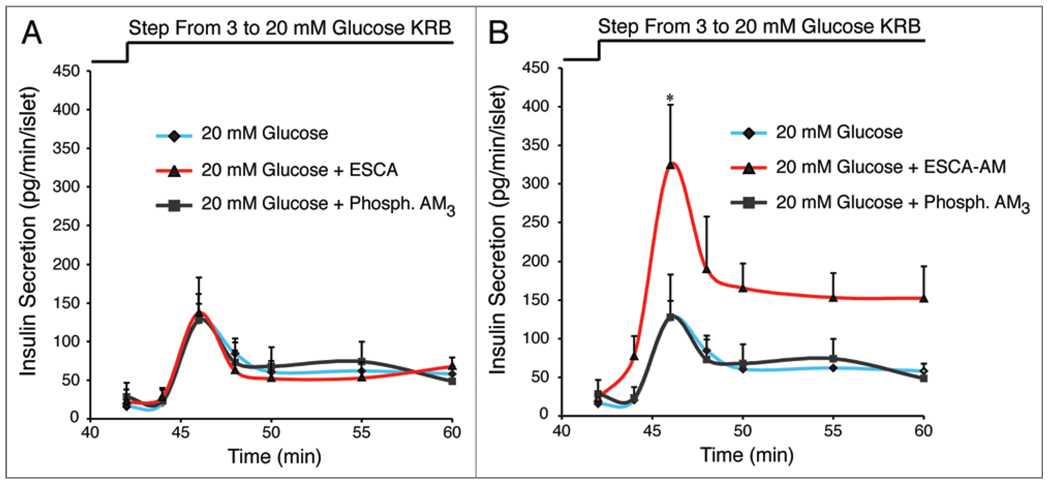

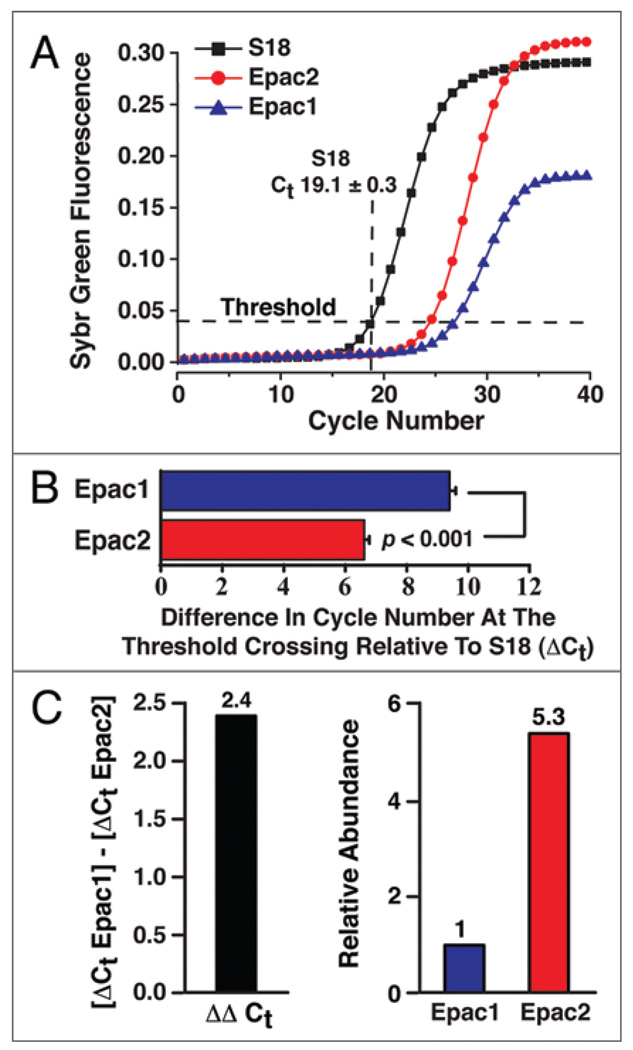

We have now expanded on these prior studies to demonstrate that 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP-AM (10 µM) potentiates the stimulatory action of 20 mM glucose on mouse islet insulin secretion (Fig. 2). This action of 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP-AM is not reproduced by 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP nor is it mimicked by phosphate-AM3 serving as a negative control (hydrolysis of the AM-ester liberates intracellular formaldehyde and acetic acid). Of primary significance is our finding that 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP-AM potentiates both the first and second phases of GSIS, whereas it has no secretagogue action in the presence of a non-stimulatory concentration of glucose (Fig. 2). Thus, 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP-AM recapitulates the glucose-dependent action of GLP-1 to stimulate islet insulin secretion.7–9 Such effects of 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP-AM might be Epac2 mediated since this isoform of Epac is the predominant isoform expressed in mouse islets, as evaluated by quantitative PCR (QPCR) (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Differential insulin secretagogue properties of Epac-selective cAMP analogs in adult male C57BL/6J mouse islets. (A) The non-AM-ester of 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP (ESCA ; 10 µM) failed to potentiate GSIS induced by a step-wise increase of glucose concentration from 3 to 20 mM. (B) GSIS induced by 20 mM glucose was potentiated by the AM-ester of 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP (ESCA-AM; 10 µM) whereas phosphate-AM3 (3.3 µM) was without effect (phosphate-AM3 liberates 3 mole equivalents of acetic acid and formaldehyde per mole of phosphate when it is hydrolyzed by intracellular esterases). Note that 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP-AM was included for 10 min in the KRB perifusate containing 3 mM glucose prior to switching to a perifusate containing 20 mM glucose. Since the initial rate of insulin secretion measured in the presence of 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP-AM did not differ from that measured in its absence, it is concluded that 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP-AM potentiated GSIS at a high but not a low concentration of glucose. For the methods of analyses, see the Supplementary Data of Chepurny et al. 2009.13

Figure 3.

QPCR for Epac1 and Epac2 mRNA expression in adult male C57BL/6J mouse islets. (A) QPCR fluorescence growth curves from 100 ng of mouse islet RNA using Quiagen QuantiTect Sybr Green RT-PCR. Ribosomal S18 mRNA was used as the reference target for quantification of Epac1 and Epac2 mRNA. The average threshold crossing value (Ct) for S18 mRNA (19.1 ± 0.3, n = 8; mean ± s.e.m.) is indicated. (B) Comparison of the delta-Ct values (ΔCt) for Epac1 and Epac2. The ΔCt value for each Epac isoform was calculated as the difference in threshold cycle number relative to S18. (C) The ΔΔCt value for Epac1 relative to Epac2 was computed by subtraction of the ΔCt values for each isoform (left) and the relative abundance of Epac1 and Epac2 mRNA was then calculated to be 1:5.3 (right).

One cautionary note for future users of 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP-AM is that under conditions of long-term treatment, this ESCA will accumulate in β-cells so that its concentration might rise to levels high enough to activate PKA.27 To address this issue, we sought to determine if 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP-AM activated PKA in various insulin-secreting cell lines or in human β-cells. Our strategy was to expose these cells to 10 µM 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP-AM for 30 min, an approach identical to that used in our assays of islet insulin secretion. Using a Kemptide PepTag assay (Promega) in which the activated form of PKA was detected in cellular lysates, we demonstrated that 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP-AM (10 µM) failed to activate PKA in rat INS-1 cells, mouse MIN6 cells, and human islets (Chepurny OG, unpublished observations). Furthermore, we found that 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP-AM failed to act in both INS-1 cells and MIN6 cells to promote Ser133 phosphorylation of transcription factor CREB, a PKA substrate (Chepurny OG, unpublished observations).13 Such findings concerning PKA and CREB are in accord with our prior report that 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP-AM failed to stimulate the expression of a PKA-regulated luciferase reporter (RIP1-CRE-Luc) that incorporates a multimerized cAMP response element (CRE) found within the rat insulin 1 gene promoter (RIP1) and which we expressed in INS-1 cells.13,52,53 Instead, we found that this reporter was stimulated by the selective PKA activator dibutyryl-cAMP-AM (Fig. 1).13

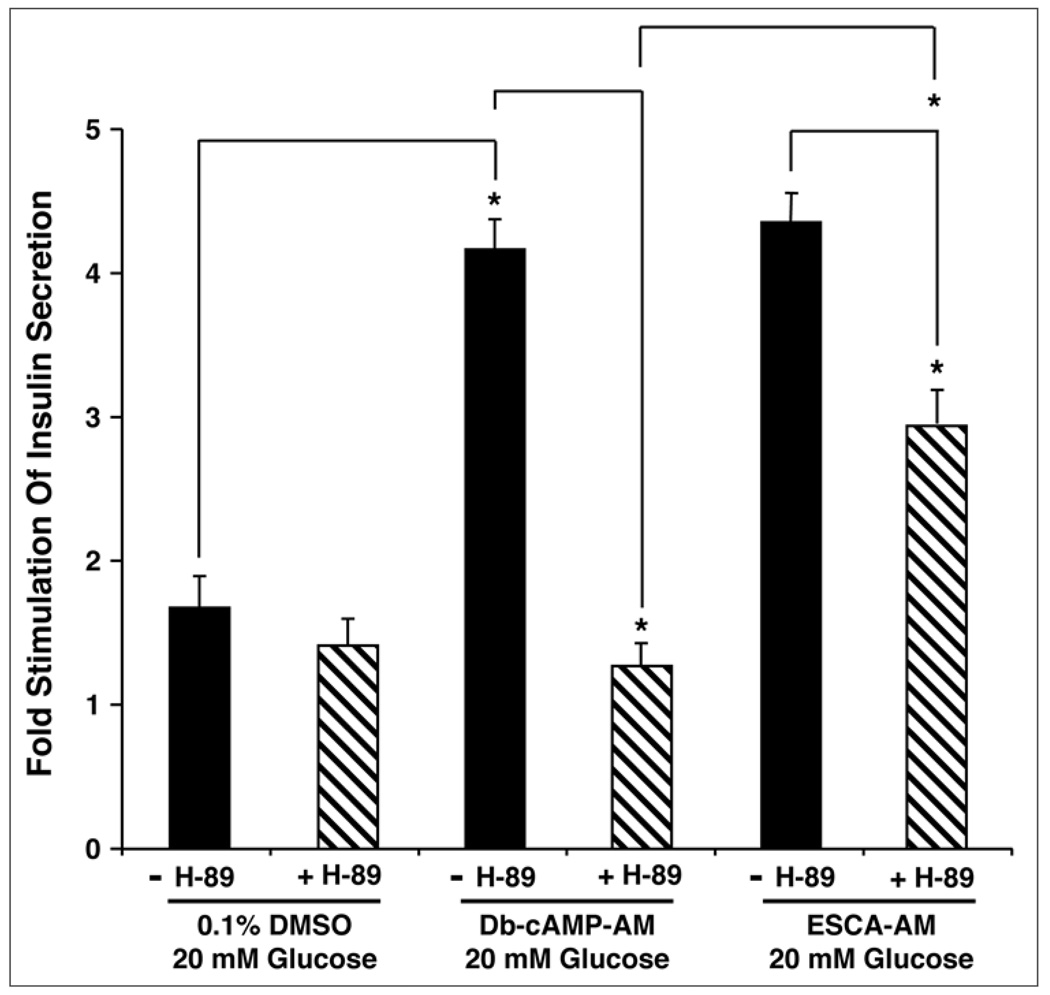

To expand on this analysis, we also performed FRET-based live-cell imaging assays to demonstrate that 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP-AM (10 µM) had only a marginal ability to activate a PKA biosensor (AKAR3) expressed by viral trasduction of human β-cells. In contrast, the PKA activator 6-Bnz-cAMP-AM (10 µM) produced an effect comparable to that of forskolin (Leech CA, Roe MW, unpublished observations). Furthermore, we recently succeeded in demonstrating that 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP-AM (10 µM) raised levels of cytosolic Ca2+ in mouse β-cells and potentiated GSIS under conditions in which mouse islets were treated with H-89 (10 µM) (Dzhura I, Dzhura E, unpublished observations). We found that treatment with H-89 reduced but did not block the action of 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP-AM to potentiate GSIS, whereas H-89 completely abrogated the action of dibutyryl-cAMP-AM to potentiate GSIS (Fig. 4). These data are understandable if the Epac-mediated action of 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP-AM to potentiate GSIS is contingent on some basal level of PKA activity that supports exocytosis. Alternatively, a 30 min exposure of mouse islets to a 10 µM concentration of 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP-AM might lead to full activation of Epac and partial activation of PKA. If so, this source of activated PKA must not be detectable in the in vitro assays of PKA activity described above. Given such uncertainties, and in view of the fact that no selective antagonist of Epac activation exists, it is likely that future studies using Epac2 knockout mice will provide a better understanding of exactly how 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP-AM interacts with β-cell glucose metabolism to stimulate islet insulin secretion.

Figure 4.

PKA inhibitor H-89 fails to abrogate the action of 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP-AM to potentiate GSIS in adult male C57BL/6J mouse islets. Illustrated are findings obtained in static incubation assays using methodologies of islet isolation and solution exposure described previously.13 Islets were exposed to KRB containing 2.8 mM glucose for 30 min and were then exposed to KRB containing 20 mM glucose with or without added test substances. These test substances included H-89 (10 µM), dibutyryl-cAMP-AM (Db-cAMP-AM; 10 µM), and 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP-AM (ESCA-AM; 10 µM). Each test substance was disolved in a vehicle solution comprised of KRB containing 0.1% DMSO and 0.1% BSA. The findings are representative of a single experiment repeated twice. Values of fold-stimulation were calculated by comparing insulin secretion measured in 20 mM glucose KRB relative to KRB containing 2.8 mM glucose. Values are mean ± s.e.m. for duplicate determinations. Statistical significance was evaluated by the t-test (*p < 0.05).

In conclusion, the new information presented here demonstrate the remarkable efficacy of 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP-AM as a potentiator of mouse islet GSIS. The challenge now is to extend upon this analysis and to establish what role if any Epac proteins play in the GPCR-mediated stimulation of islet insulin secretion. GPCR agonists known to stimulate cAMP production and to potentiate GSIS include not only GLP-1 but also glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide (GIP), pituitary adenylyl cyclase-activating peptide (PACAP), and oleoylethanolamide (OEA, a GPR119 agonist).54 Thus, it seems reasonable to speculate that the differential abilities of these agents to lower levels of blood glucose in type 2 diabetic subjects might be related to each agonist’s propensity to signal predominantly through either Epac or PKA. In this vein, it is important to note that Epac1 is detectable in mouse islets and that the knockout of Epac1 was recently reported to interfere with glucose homeostasis in mice.55 Thus, one important issue that remains outstanding concerns the potential dual roles Epac1 and Epac2 in β-cell function.

Acknowledgements

Funding was provided by the NIH (DK045817, DK069575 to G.G.H.; DK074966 to M.W.R.) and the American Diabetes Association (Research Award to C.A.L.).

Abbreviations

- cAMP

adenosine-3',5'-cyclic monophosphate

- cAMP-GEF

cAMP-regulated guanine nucleotide exchange factor

- CRE

cAMP response element

- Epac

exchange protein directly activated by cAMP

- ESCA

Epac-selective cAMP analog

- GLP-1

glucagon-like peptide-1-(7–36)-amide

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- GSIS

glucose-stimulated insulin secretion

- K-ATP

ATP-sensitive K+ channel

- PKA

protein kinase A

- 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP-AM

8-(4-Chlorophenylthio)-2'-O-methyladenosine-3',5'-cyclic monophosphate acetoxymethyl ester

References

- 1.Drucker DJ. Glucagon-like peptides. Diabetes. 1998;47:159–169. doi: 10.2337/diab.47.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kieffer TJ, Habener JF. Glucagon-like peptides. Endocrine Reviews. 1999;20:876–913. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.6.0385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holst JJ. Glucagon-like peptide-1: a gastrointestinal hormone with a pharmaceutical potential. Current Med Chem. 1999;6:1005–1017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nauck MA. Unraveling the science of incretin biology. Am J Med. 2009;122:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thorens B. Expression cloning of the pancreatic beta-cell receptor for the gluco-incretin hormone glucagon-like peptide-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:8641–8645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.18.8641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drucker DJ, Philippe J, Mojsov S, Chick WL, Habener JF. Glucagon-like peptide I stimulates insulin gene expression and increases cyclic AMP levels in a rat islet cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:3434–3438. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.10.3434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mojsov S, Weir GC, Habener JF. Insulinotropin: glucagon-like peptide I (7–37) co-encoded in the glucagon gene is a potent stimulator of insulin release in the perfused rat pancreas. J Clin Invest. 1987;79:616–619. doi: 10.1172/JCI112855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holst JJ, Orskov C, Nielsen OV, Schwartz TW. Truncated glucagon-like peptide I, an insulin-releasing hormone from the distal gut. FEBS Lett. 1987;211:169–174. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)81430-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weir GC, Mojsov S, Hendrick GK, Habener JF. Glucagon-like peptide I (7–37) actions on endocrine pancreas. Diabetes. 1989;38:338–342. doi: 10.2337/diab.38.3.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holz GG, Habener JF. Signal transduction crosstalk in the endocrine system: pancreatic beta-cells and the glucose competence concept. Trends Biochem Sci. 1992;17:388–393. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(92)90006-u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holz GG. New insights concerning the glucose-dependent insulin secretagogue action of glucagon-like peptide-1 in pancreatic beta-cells. Horm Metab Res. 2004;36:787–794. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-826165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holz GG, Heart E, Leech CA. Synchronizing Ca2+ and cAMP oscillations in pancreatic beta-cells: a role for glucose metabolism and GLP-1 receptors? Focus on “regulation of cAMP dynamics by Ca2+ and G protein-coupled receptors in the pancreatic beta-cell: a computational approach”. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;294:4–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00522.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chepurny OG, Leech CA, Kelley GG, Dzhura I, Dzhura E, Li X, et al. Enhanced Rap1 activation and insulin secretagogue properties of an acetoxymethyl ester of an Epac-selective cyclic AMP analog in rat INS-1 cells: studies with 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP-AM. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:10728–10736. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900166200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ozaki N, Shibasaki T, Kashima Y, Miki T, Takahashi K, Ueno H, et al. cAMP-GEFII is a direct target of cAMP in regulated exocytosis. Nature Cell Biol. 2000;2:805–811. doi: 10.1038/35041046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kashima Y, Miki T, Shibasaki T, Ozaki N, Miyazaki M, Yano H, Seino S. Critical role of cAMP-GEFII Rim2 complex in incretin-potentiated insulin secretion. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:46046–46053. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108378200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujimoto K, Shibasaki T, Yokoi N, Kashima Y, Matsumoto M, Sasaki T, et al. Piccolo, a Ca2+ sensor in pancreatic beta-cells. Involvement of cAMP-GEFII-Rim2-Piccolo complex in cAMP-dependent exocytosis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:50497–50502. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210146200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang G, Chepurny OG, Holz GG. cAMP-Regulated guanine nucleotide exchange factor-II (Epac2) mediates Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release in INS-1 pancreatic beta-cells. J Physiol (Lond) 2001;536:375–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0375c.xd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kang G, Joseph JW, Chepurny OG, Monaco M, Wheeler MB, Bos JL, et al. Epac-selective cAMP analog 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP as a stimulus for Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release and exocytosis in pancreatic beta cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8279–8285. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211682200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holz GG. Epac—A new cAMP-binding protein in support of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor-mediated signal transduction in the pancreatic beta-cell. Diabetes. 2004;53:5–13. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shibasaki T, Sunaga Y, Fugimoto K, Kahima Y, Seino S. Interaction of ATP sensor, cAMP sensor, Ca2+ sensor, and voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel in insulin granule exocytosis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:7956–7961. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309068200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seino S, Shibasaki T. PKA-dependent and PKA-independent pathways for cAMP-regulated exocytosis. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:1303–1342. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00001.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kang G, Chepurny OG, Rindler MJ, Collis L, Chepurny Z, Li WH, et al. A cAMP and Ca2+ coincidence detector in support of Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release in mouse pancreatic beta cells. J Physiol (Lond) 2005;566:173–188. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.087510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kang G, Chepurny OG, Malester B, Rindler MJ, Rehmann H, Bos JL, et al. cAMP sensor Epac as a determinant of ATP-sensitive potassium channel activity in human pancreatic beta cells and rat INS-1 cells. J Physiol. 2006;573:595–609. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.107391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu G, Jacobo SM, Hilliard N, Hockerman GH. Differential modulation of CaV1.2 and CaV1.3-mediated glucose-stimulated insulin secretion by cAMP in INS-1 cells: distinct roles for exchange protein directly activated by cAMP 2 (Epac2) and protein kinase A. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;318:152–160. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.097477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kang G, Leech CA, Chepurny OG, Coetzee WA, Holz GG. Role of the cAMP sensor Epac as a determinant of KATP channel ATP sensitivity in human pancreatic beta cells and rat INS-1 cells. J Physiol (Lond) 2008;586:1307–1319. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.143818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shibasaki T, Takahashi H, Miki T, Sunaga Y, Matsumura K, Yamanaka M, et al. Essential role of Epac2/Rap1 signaling in regulation of insulin granule dynamics by cAMP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;104:19333–19338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707054104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Enserink JM, Christensen AE, de Rooij J, van Triest M, Schwede F, Genieser HG, et al. A novel Epac-specific cAMP analogue demonstrates independent regulation of Rap1 and ERK. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:901–906. doi: 10.1038/ncb874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsuboi T, da Silva Xavier G, Holz GG, Jouaville LS, Thomas AP, Rutter GA. Glucagon-like peptide-1 mobilizes intracellular Ca2+ and stimulates mitochondrial ATP synthesis in pancreatic MIN6 beta-cells. Biochem J. 2003;369:287–299. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eliasson L, Ma X, Renstrom E, Barg S, Berggren PO, Galvanovskis J, et al. SUR1 regulates PKA-independent cAMP-induced granule priming in mouse pancreatic beta-cells. J Gen Physiol. 2003;121:181–197. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kwan EP, Xie L, Sheu L, Ohtsuka T, Gaisano HY. Interaction between Munc13-1 and RIM is critical for glucagon-like peptide-1 mediated rescue of exocytotic defects in Munc13-1 deficient pancreatic beta-cells. Diabetes. 2007;56:2579–2588. doi: 10.2337/db06-1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kwan EP, Gao X, Leung YM, Gaisano HY. Activation of exchange protein directly activated by cyclic adenosine monophosphate and protein kinase A regulate common and distinct steps in promoting plasma membrane exocytic and granule-to-granule fusions in rat islet beta cells. Pancreas. 2007;35:45–54. doi: 10.1097/mpa.0b013e318073d1c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kelley GG, Reks SE, Ondrako JM, Smrcka AV. Phospholipase C-epsilon: a novel Ras effector. EMBO J. 2001;20:743–754. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.4.743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmidt M, Evellin S, Weernink PA, von Dorp F, Rehmann H, Lomasney JW, Jakobs KH. A new phospholipase-C-calcium signalling pathway mediated by cyclic AMP and a Rap GTPase. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:1020–1024. doi: 10.1038/ncb1101-1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holz GG, Kang G, Harbeck M, Roe MW, Chepurny OG. Cell physiology of cAMP sensor Epac. J Physiol (Lond) 2006;577:5–15. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.119644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.deRooij J, Zwartkruis FJT, Verheijen MHG, Cool RH, Nijman SMB, Wittinghofers A, Bos JL. Epac is a Rap1 guanine nucleotide-exchange factor directly activated by cyclic AMP. Nature. 1998;396:474–477. doi: 10.1038/24884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawasaki H, Springett GM, Mochizuki N, Toki S, Nakaya M, Matsuda M, et al. A family of cAMP-binding proteins that directly activate Rap1. Science. 1998;282:2275–2279. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holz GG, Chepurny OG, Schwede F. Epac-selective cAMP analogs: new tools with which to evaluate the signal transduction properties of cAMP-regulated guanine nucleotide exchange factors. Cellular Signalling. 2008;20:10–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Renstrom E, Eliasson L, Rorsman P. Protein kinase A-dependent and -independent stimulation of exocytosis by cAMP in mouse pancreatic B-cells. J Physiol (Lond) 1997;502:105–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.105bl.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamada S, Komatsu M, Sato Y, Yamauchi K, Kojima I, Aizawa T, Hashizume K. Time-dependent stimulation of insulin exocytosis by 3',5'-cyclic adenosine monophosphate in the rat islet beta-cell. Endocrinology. 2002;143:4203–4209. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thams P, Anwar MR, Capito K. Glucose triggers protein kinase A-dependent insulin secretion in mouse pancreatic islets through activation of the K-ATP channel-dependent pathway. Eur J Endocrinol. 2005;152:671–677. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.01885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hashiguchi H, Nakazaki M, Koriyama N, Fukudome M, Aso K, Tei C. Cyclic AMP/cAMP-GEF pathway amplifies insulin exocytosis induced by Ca2+ and ATP in rat islet beta-cells. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2006;22:64–71. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bos JL. Epac: a new cAMP target and new avenues in cAMP research. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:733–738. doi: 10.1038/nrm1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bos JL. Epac proteins: multi-purpose cAMP targets. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:680–686. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hatakeyama H, Takahashi N, Kishimoto T, Nemoto T, Kasai H. Two cAMP-dependent pathways differentially regulate exocytosis of large dense-core and small vesicles in mouse beta-cells. J Physiol (Lond) 2007;582:1087–1098. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.135228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takahashi N, Kadowaki T, Yazaki Y, Ellis-Davies GCR, Miyashita Y, Kasai H. Post-priming actions of ATP on Ca2+-dependent exocytosis in pancreatic beta-cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:760–765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kasai H, Suzuki T, Liu TT, Kishimoto T, Takahashi N. Fast and cAMP-sensitive mode of Ca2+ dependent exocytosis in pancreatic beta-cells. Diabetes. 2002;51:19–24. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.2007.s19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hatakeyama H, Kishimoto T, Nemoto T, Kasai H, Takahashi N. Rapid glucose sensing by protein kinase A for insulin exocytosis in mouse pancreatic islets. J Physiol. 2006;570:271–282. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.096560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang Y, Gillis KD. A highly Ca2+-sensitive pool of granules is regulated by glucose and protein kinases in insulin-secreting INS-1 cells. J Gen Physiol. 2004;124:641–651. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200409081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wan QF, Dong Y, Yang H, Lou X, Ding J, Xu T. Protein kinase activation increases insulin secretion by sensitizing the secretory machinery to Ca2+ J Gen Physiol. 2004;124:653–662. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200409082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Merrins MJ, Stuenkel EL. Kinetics of Rab27a-dependent actions on vesicle docking and priming in pancreatic beta-cells. J Physiol (Lond) 2008;586:5367–5381. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.158477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vliem MJ, Ponsioen B, Schwede F, Pannekoek WJ, Riedl J, Kooistra MR, et al. 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP-AM: an improved Epac-selective cAMP analogue. Chembiochem. 2008;9:2052–2054. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chepurny OG, Hussain MA, Holz GG. Exendin-4 as a stimulator of rat insulin I gene promoter activity via bZIP/CRE interactions sensitive to serine/threonine protein kinase inhibitor Ro 31-8220. Endocrinology. 2002;143:2303–2313. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.6.8870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chepurny OG, Holz GG. A novel cyclic adenosine monophosphate responsive luciferase reporter incorporating a nonpalindromic cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element provides optimal performance for use in G protein coupled receptor drug discovery efforts. J Biomol Screen. 2007;12:740–746. doi: 10.1177/1087057107301856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ahrén B. Islet G protein-coupled receptors as potential targets for treatment of type 2 diabetes. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:369–385. doi: 10.1038/nrd2782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kai AKL, Lam AKM, Zhang X, Lai AKW, Xu Z, Vanhoutte PM, et al. Targeted disruption of exchange protein directly activated by cAMP-1 in mice leads to altered islet architecture and reduced beta-cell distribution of GLUT-2. New Orleans LA: 69TH Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association; 2009. Late-Breaking Abstract, 81-LB. [Google Scholar]