Abstract

Objective:

This study examined initiation of alcohol use among adolescents, in relation to their earlier traumatic experiences and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Method:

Data were from a longitudinal study of children of Puerto Rican background living in New York City's South Bronx and in San Juan, Puerto Rico. The subsample (n = 1,119; 51.7% male) of those who were 10–13 years old and alcohol naive at baseline was used in the analyses.

Results:

Alcohol-use initiation within 2 years after baseline was significantly more common among children reporting both trauma exposure and 5 or more of a maximum of 17 PTSD symptoms at baseline (adjusted odds ratio = 1.84, p 7 < .05) than among those without trauma exposure, even when potentially shared correlates were controlled for. Children with trauma exposure but with fewer than five PTSD symptoms, however, did not differ significantly from those without trauma exposure, with regard to later alcohol use.

Conclusions:

PTSD symptoms in children 10–13 years old may be associated with early onset of alcohol use. It is important to identify and treat PTSD-related symptoms in pre-adolescent children.

Severe childhood trauma is often reported by those presenting with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) comorbid with a substance-use disorder (Epstein et al., 1998; Jelley, 2003; Schumacher et al., 2006; Waldrop et al., 2007; Weinstein, 1998). There is evidence that PTSD, or PTSD symptoms, following childhood traumatic experiences may be related to later substance-use disorders, especially among girls and women (Duncan et al., 1996; Epstein et al., 1998; Jelley, 2003; Lipschitz et al., 2003; Ullman et al., 2005) but also among men (Deykin and Buka, 1997; Grice et al., 1995; Jelley, 2003; Weinstein, 1998). Only retrospective information on childhood experiences and on PTSD symptoms preceding the onset of substance-use disorders was available to these researchers, however. Such information is vulnerable to the effects of recall bias (Schroeder and Costa, 1984).

The relationships among childhood trauma, PTSD, and substance-use disorder can be better understood if examined prospectively. In addition, research focusing on a very early stage of the process, such as the onset of alcohol use, has the potential to be especially informative. Studies have shown that initiation of alcohol use during the pre-adolescent and early adolescent years is associated with traumatic experiences of earlier childhood (Bensley et al., 1999; Hamburger et al., 2008; Sartor et al., 2007). Such early alcohol-use initiation is, in turn, predictive of the development of alcohol and other substance-use-related problems in adolescence (Bensley et al., 1999; Kandel, 2002; Sartor et al., 2007) and of alcohol and drug dependence in adulthood (Bensley et al., 1999; DeWit et al., 2000; Ellickson et al., 2003; Hingson et al., 2006; Hingson and Zha, 2009; McGue et al., 2001; Sartor et al., 2007; Warner and White, 2003).

It has been suggested that early alcohol-use initiation results partly from a sense of dissatisfaction, on the part of the child, with the world as he or she has known it (Zucker et al., 2008). The painful affect and disturbing memories associated with symptoms of PTSD would help to create such a sense of dissatisfaction in a child (Flood et al., 2009). Previous studies examining the relationship between childhood trauma and early initiation of alcohol use have not, however, taken PTSD symptomatology into account. The current longitudinal study examines both childhood traumatic experiences and PTSD symptoms, in relation to subsequent alcohol-use initiation.

PTSD and early onset of alcohol use share other common antecedents in addition to childhood traumatization, a fact that can complicate efforts to understand their relationship. For example, factors related to alcohol-use initiation in pre-adolescence and early adolescence include frequent parental alcohol use (Casswell et al., 1991), parental emotional disorders (Cortes et al., 2009; Mowbray and Oyserman, 2003), low levels of parental monitoring (Gilbreth, 2001; O'Donnell et al., 2008), and a poor parent-child relationship (Cohen et al., 1994; DeWit et al., 1999), as well as child sensation-seeking tendencies (Martin et al., 2004), and conduct problems and antisocial behaviors (Kuperman et al., 2005; McGue et al., 2001). Many of these factors have also been found to be associated with exposure to trauma (Breslau et al., 1991), and with PTSD symptoms (Saigh et al., 1999). Thus, when exploring the relationship of trauma and PTSD symptoms with alcohol-use initiation, it is important to take these factors into account, as they could potentially confound or mediate the relationship of interest.

A developmental perspective on the interrelationships among exposure to trauma, PTSD, and alcohol use is essential to the effectiveness of efforts to improve early detection of trauma-related psychiatric symptoms and prevent early onset of alcohol use and the subsequent development of alcohol-use disorders. The current study (a) examines the relationship between childhood traumatic experiences and PTSD symptoms, and subsequent initiation of alcohol use; and (b) investigates whether the observed relationship of trauma and PTSD symptoms with alcohol-use initiation can be explained by shared risk factors.

Method

Sample

The Boricua Youth Study is a three-wave longitudinal study of psychopathology and substance use among Puerto Rican children in two contexts with high concentrations of Puerto Ricans: the South Bronx in New York City and the San Juan Standard Metropolitan Area in Puerto Rico. Probability samples of boys and girls ages 5–13 years (N = 2,491) were obtained from both sites and assessed between 2000 and 2004. The completion rates for Waves 2 and 3 were 92% and 88% of the baseline sample, respectively. A subsample, consisting of children who at baseline were ages 10–13 years and reported never having used alcohol, and who completed interviews both at baseline and at either of the two follow-ups (n = 1,119; 51.7% male), was used for these analyses. The Wave 2 and Wave 3 follow-up interviews were conducted 1 and 2 years after baseline, respectively. Analyses comparing those who dropped out of the study after the baseline interview with those who remained in the study showed that those lost to attrition were more likely to come from families with more highly educated parents and were also more likely to belong to the South Bronx sample.

Procedures

Structured in-person interviews were conducted by trained lay interviewers separately with parents and children in the families' homes, in English or in Spanish. For children 10 or older at baseline, information on child psychiatric disorders, family sociodemographic factors, and a wide array of risk factors was obtained from both the parent and the child (Bird et al., 2006a, 2006b).

Children who, at baseline, were 10 years old or older and had never used alcohol, were selected to be included in our analyses (n = 1,119; 51.7% boys). The mean age at baseline was 11.5 years. About 20.8% of the children were from families in which neither parent had finished high school; 33.3% were from families in which at least one parent had finished college. Data on 503 child subjects from the Bronx site, and 616 children from the Puerto Rico site, were used in this study. The two groups were not found to differ from each other with regard to the outcome variable of alcohol-use initiation. They did, however, differ on some of the independent variables. Compared with children from the Puerto Rico site, for example, those from the South Bronx site were more likely to report trauma exposure; their parents tended to have a lower level of education; and they were more likely to come from single-parent families. Because of these observed site differences, study site was controlled for in all of the regression analyses.

Written informed consent was obtained from the adult informants, and the youth informants signed assent forms. Consent forms and procedures were approved by the institutional review boards of the New York State Psychiatric Institute and the University of Puerto Rico Medical School. The interviews were conducted using laptop computers. Sample maintenance procedures followed guidelines provided by Stouthamer-Loeber and Van Kammen (1995). More detailed information about the survey procedures can be obtained elsewhere (Bird et al., 2006a; Bird et al., 2007).

The institutional review board of the New York State Psychiatric Institute reviewed and approved the analyses used in the current study.

Measures

Measures of alcohol use.

Child alcohol use was assessed using questions regarding lifetime and past-year alcohol use as well as questions from the alcohol-abuse section of the National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, DSM-IV version (DISC-IV; Shaffer et al., 2000). Alcohol use was defined as drinking a full can or bottle of beer, a glass of wine or wine cooler, a shot of distilled spirits, or a mixed drink with distilled spirits in it (not just sips from another person's drink). A child was considered an alcohol user if either the child or the parent reported such use. Only children who had not used alcohol at baseline were included in the study sample. Self-reported use of alcohol at either follow-up interview was therefore considered to represent alcohol-use initiation. For the survival analyses, the time (in years) from baseline to a child's initiation of alcohol use was used as the outcome variable.

Measures of trauma and PTSD symptoms.

At baseline, child traumatic event exposure and PTSD symptoms were assessed by the DISC-IV (Shaffer et al., 2000), based on DSM-IV PTSD criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). The DISC-IV first identifies children meeting criteria for trauma exposure (i.e., those who have experienced, witnessed, or been confronted with any of the eight types of life-threatening events listed and who experienced intense sensations of fear, helplessness, and/or horror at the time). For those meeting these criteria, a series of 17 PTSD symptom questions were then asked. For our analyses, a symptom is considered to be positive if the corresponding question item received a positive response from either the parent or the child (Shaffer et al., 2000). Trauma exposures and PTSD symptom counts, as reported at baseline, were used as predictors. The children were divided into three groups for the purposes of the analyses: (a) those not reporting, at baseline, any trauma exposure; (b) those with reported trauma exposure but falling below the 50th percentile, with regard to number of PTSD symptoms, of those with exposure (i.e., those having fewer than five PTSD symptoms); and (c) those at or above the 50th percentile with regard to PTSD symptoms (i.e., having five or more PTSD symptoms).

Parental factors.

Parental psychopathology was measured by the Family History Screen for Epidemiological Studies (FHS; Lish et al., 1995) and questions developed for the Boricua study measuring DSM-IV criteria for antisocial behavior disorder, which were included in the parent interview. Three dichotomous variables were created: (a) parental emotional problems was coded as 1 if one or more of six items in the FHS, covering depressive symptoms, suicide attempts, nervous attacks, and other emotional problems, received a positive response; (b) the parental substance-use problems variable was created based on parent informants' responses to two items in the FHS, one on drinking problems and the other on drug problems, in the parent informant and/or his or her co-parent; and (c) the probable parental antisocial personality disorder variable was created using responses to a set of questions based on DSM-IV criteria for antisocial behavior and one additional question taken from the FHS regarding the parent's being arrested or convicted of a crime.

Parental monitoring was assessed using a Likert-type scale based on nine questions from the parent interview about parents' monitoring of the child's daily after-school activities and general awareness of the child's whereabouts. A high score represents a high level of parental monitoring. The scale has fair reliability (Cronbach's α = .55; Patterson and Stouthamer-Loeber, 1984).

Parental discipline was measured using six items from the parent interview covering various forms of physical punishment, as well as verbal abuse and withholding of affection. The scale's reliability is fair (Cronbach's α = .54; Goodman et al., 1998). Maternal Warmth and Supportiveness is a Likert-type scale using 13 parent interview questions about the mother-child relationship. A high score indicates a close relationship. The scale's reliability is satisfactory (Cronbach's α = .72; Bird et al., 2006a; Hudson, 1982).

Individual-level factors.

Sensation seeking was measured by an abbreviated version of Russo et al.'s (1991, 1993) sensation-seeking scale (Bird et al., 2006a), included in the child interview. The Cronbach's α for this scale is .72 (Bird et al., 2006a).

Antisocial behavior is a five-category classification of antisocial behaviors based on severity ratings assigned by nine mental health clinicians to items from the conduct disorder and oppositional defiant disorder sections of the DISC-IV and from the Elliot Delinquency Scales; it ranks children along a hierarchy of seriousness or severity of antisocial behaviors (Bird et al., 2005).

Church attendance information was obtained in the child interview and children were divided into three groups: never attend, attend irregularly, and attend regularly.

Sociodemographic factors.

Sociodemographic variables include child age, gender, and parents' highest number of years of education completed. Family structure variables include family composition (i.e., single vs. two parental figures).

Statistical analysis

The children in the study sample were divided into three groups, as described above, according to their baseline reports of traumatic experiences and PTSD symptoms. For each of the three groups, rates of alcohol-use initiation since the baseline interview, reported at either follow-up, were calculated. In the bivariate analyses, t test or analysis of variance was used to test for group differences in continuous variables, and chi-square test was used to detect bivariate associations between categorical variables, particularly the associations of baseline trauma exposure and levels of PTSD symptoms, and of subsequent alcohol-use initiation reported at follow-up, with site (South Bronx, Puerto Rico) and other factors at the family, parental, and individual levels as measured at baseline. Last, site-stratified Cox proportional hazards models for time from baseline to onset of alcohol use were used to examine the relationship of trauma exposure and PTSD symptoms at baseline with time to alcohol initiation, adjusting for sets of other baseline variables hierarchically. Model 1 included main predictors of exposure to trauma and PTSD symptoms at baseline. Model 2 included additional family-level sociodemographic variables (age, gender, single-parent family, and parental education level). Model 3 further included the parental factors that were associated with the alcohol initiation outcomes and the main predictors in bivariate analysis. Model 4 was an extension of Model 3 with child antisocial behavior as an additional covariate, to test whether the observed relationship of trauma and PTSD with alcohol initiation was mediated by antisocial behaviors. Relative risks, along with 95% confidence intervals, were derived from the models to aid interpretation.

SUDAAN software (Research Triangle Institute, 2001) was used to obtain corrected estimates of the variances of the parameters, by taking the complex features of the sampling design into account.

Results

Bivariate analyses

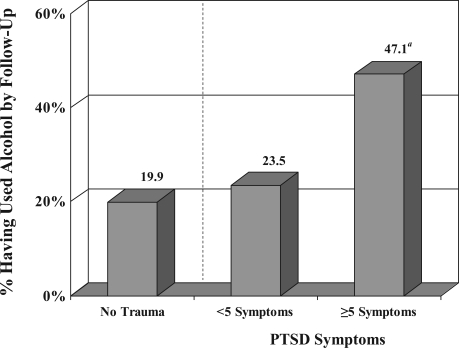

The majority of these children (unweighted n = 960) did not report any exposure to traumatic events; 82 children reported exposure to traumatic events but had fewer than five PTSD symptoms; and 77 children reported both trauma exposure and five or more PTSD symptoms. By Wave 3 of the study, 265 of the children reported that they had consumed at least one drink. Figure 1 shows that the rate of alcohol-use initiation of the group with five or more PTSD symptoms was more than double that of the group with no trauma experience (47.1% vs. 19.9%). The rate of alcohol initiation for those with trauma experience but with few PTSD symptoms (23.5%) was not significantly different from that of the no-exposure group, however.

Figure 1.

Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms at baseline and alcohol-use initiation by follow-up, among adolescents who were not alcohol users at baseline (n = 1,119). aSignificantly different from the “no-trauma” group, p = .001.

Bivariate analyses were also conducted to identify, from among a set of baseline sociodemographic, parental, and individual-level factors, variables associated both with alcohol initiation and with the PTSD measures (trauma exposure and PTSD symptoms; Table 1).

Table 1.

Factors associated with alcohol use initiation, exposure to traumatic events, and PTSD (n = 1,119)

| Alcohol use by follow-up |

Exposure to trauma and PTSD Symptoms at baseline Exposed to traumatic event(s) |

||||

| Independent variables (baseline) | No use (n = 854) | Use (n = 265) | No traumatic event (n = 960) | <5 PTSD symptoms (n = 82) | ≥5 PTSD symptoms (n = 77) |

| Age, in years, M (SE) | 11.3(0.05)** | 12.2 (0.08)*** | 11.5 (0.05) | 11.6 (0.16) | 11.9 (0.15)* |

| Female, % | 49.9 | 49.4 | 49.3 | 51.2 | 52.9 |

| Parental education, % | |||||

| <High school | 29.7 | 23.3 | 28.2 | 36.1 | 22.2 |

| High school | 49.7 | 49.7 | 49.3 | 46.5 | 58.6 |

| ≥College | 20.6 | 27.0 | 22.5 | 17.4 | 21.2 |

| Single-parent family, % | 45.2 | 46.2 | 43.1 | 54.1 | 59.6* |

| Parental emotional problems, % | 35.0 | 42.6§ | 36.2 | 32.3 | 57.0* |

| Parental substance-use problems, % | 12.8 | 19.7§ | 13.9 | 13.4 | 19.9 |

| Probable parental ASPD, % | 13.0 | 23.4* | 14.7 | 13.6 | 23.5 |

| Parental monitoring, M (SE) | 13.6(0.12) | 12.5 (0.26)*** | 13.5 (0.14) | 12.9 (0.36) | 12.4 (0.43)§ |

| Maternal warmth and supportiveness, M(SE) | 2.4 (0.02) | 2.3 (0.04)* | 2.4 (0.02) | 2.3 (0.06) | 2.2 (0.04) |

| Parental discipline, M (SE) | 0.4 (0.03) | 0.6 (0.05)** | 0.5 (0.03) | 0.5 (0.06) | 0.5 (0.07) |

| Child sensation seeking, M (SE) | 3.5(0.11) | 4.9 (0.20)*** | 3.8 (0.11) | 3.6 (0.30) | 4.3 (0.31) |

| Child antisocial behavior, M (SE) | 1.2(0.06) | 2.1 (0.13)*** | 1.4 (0.06) | 1.6 (0.19) | 2.1 (0.21)** |

| Child church attendance, % | |||||

| Never | 13.4 | 14.3 | 14.7 | 9.1 | 7.1 |

| Irregular | 37.7 | 38.1 | 37.6 | 42.1 | 35.5 |

| Regular | 48.8 | 47.6 | 47.7 | 48.8 | 57.4 |

Notes: PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; ASPD = antisocial personality disorder.

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Table 1 shows that a number of baseline sociodemographic, parental, and individual-level factors—specifically, child age, probable parental antisocial personality disorder, parental discipline, child sensation seeking, and child antisocial behavior—were found to be significantly and positively associated with initiation of alcohol use, whereas parental monitoring and maternal warmth and supportiveness were negatively associated with alcohol initiation. Rates of parental emotional problems and substance-use problems were also higher among the parents of adolescent alcohol-use initiators than among those of the nonusers. These differences were only marginally significant, however.

The pattern of associations found with trauma exposure and PTSD symptom levels is in some ways similar to that found for alcohol-use initiation, with significant differences found for child age, parental emotional problems, and child antisocial behavior. Parental monitoring appeared to be negatively related to the measure of trauma and PTSD, but the difference was only marginally significant. Unlike alcohol-use initiation, the trauma exposure and PTSD symptoms measure was significantly positively associated with belonging to a single-parent family.

Site-stratified Cox proportional hazards models for time since baseline to the onset of alcohol use were applied and the results are reported in Table 2. The major demographic factors, as well as the other factors that had been found, in bivariate analyses, to be associated both with alcohol initiation and with trauma exposure and PTSD symptoms (including those that were marginally significant), were added into the model in a hierarchical sequence. Children who had experienced trauma but had few PTSD symptoms did not differ significantly from those without trauma experience, with regard to alcohol initiation. Children with both trauma experience and a higher level of PTSD symptoms were more likely to initiate alcohol use after baseline than those without trauma experience. It can be seen in Models 1-4 in Table 2 that other factors associated both with PTSD symptoms and with alcohol initiation do partially explain the association between PTSD and risk of alcohol initiation. For the comparison between (a) children with trauma experience and high PTSD symptoms and (b) those without trauma experience, the estimated relative risk after adjusting for other baseline factors for alcohol initiation did fall from 3.13 (p < .001) in Model 1 to 2.29 (p < .05) in Model 4 (in which all of the associated factors were controlled for); however, it remained significant. The Model 4 results also show that, in addition to high PTSD symptom level, child older age and child antisocial behavior were both independently predictive of alcohol initiation. Low parental monitoring also appeared to be associated with child initiation of alcohol use, but this relationship was only marginally significant. To test for a gender difference in the relationship of trauma and PTSD with subsequent initiation of alcohol use, we also examined the statistical interaction between our main predictor and gender; the interaction was not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Relative risk of initiation of alcohol use after baselinea

| Independent variables (at baseline) | Model 1 Relative riskb [95% CI] | Model 2 Relative risk [95% CI] | Model 3 Relative risk [95% CI] | Model 4 Relative risk [95% CI] |

| Main predictor | ||||

| Trauma exposure and level of PTSD symptoms (ref. = no traumatic events) | ||||

| Low PTSD symptoms (<5) | 1.16 | 1.08 | 1.02 | 1.06 |

| [0.56, 2.42] | [0.51, 2.31] | [0.48, 2.15] | [0.50, 2.25] | |

| High PTSD symptoms (≥5) | 3.13*** | 2.48** | 2.49** | 2.29* |

| [1.75,5.60] | [1.28, 4.77] | [1.31, 4.75] | [1.19, 4.41] | |

| Control variables | ||||

| Agec | 1 99*** | 1.96*** | 1.91*** | |

| [1.66,2.39] | [1.62, 2.36] | [1.57, 2.31] | ||

| Girl | 1.32 | 1.26 | 1.48 | |

| [0.84, 2.08] | [0.82, 1.95] | [0.92, 2.38] | ||

| Parental education (ref. = college) | ||||

| No high school | 0.82 | 0.83 | 1.04 | |

| [0.41, 1.65] | [0.42, 1.65] | [0.51, 2.12] | ||

| High school | 0.99 | 1.11 | 1.20 | |

| [0.57, 1.70] | [0.63, 1.95] | [0.67, 2.13] | ||

| Single parent | 0.93 | 0.90 | 0.82 | |

| [0.62, 1.41] | [0.60, 1.35] | [0.54, 1.23] | ||

| Parental emotional problems | 0.85 | 0.72 | ||

| [0.56, 1.30] | [0.46, 1.13] | |||

| Parental monitoringc | 0.89** | 0.92§ | ||

| [0.81, 0.97] | [0.84, 1.02)] | |||

| Child antisocial behaviorc | 1.39*** | |||

| [1.17, 1.65] | ||||

Notes: CI = confidence interval; ref. = reference; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

Derived from proportional hazards model

relative risk adjusting for site and other factors in the model

continuous variables.

p < .10;

p <.05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Discussion

Many previous studies of adults have retrospectively linked adult alcohol and other substance-use disorders with childhood traumatization (Brems et al., 2004; Epstein et al., 1998; Sartor et al., 2007; Weinstein, 1998), and others have provided evidence that such a link is at least partially explained by PTSD or PTSD symptoms (Duncan et al., 1996; Epstein et al., 1998; Weinstein, 1998; Zlotnick et al., 2006). Few, if any, studies have addressed the issue prospectively and focused on children and adolescents. To our knowledge, no previous study has prospectively examined both childhood trauma and related PTSD symptoms in relation to subsequent early onset of alcohol use.

Children with five or more PTSD symptoms were significantly more likely to become alcohol users than those without exposure to trauma, whereas those with trauma experience but with fewer than five PTSD symptoms did not have an elevated rate of alcohol-use initiation. These findings lend support to the idea that PTSD symptoms may lead traumatized youth to begin or increase their use of alcohol or other substances as a means of self-medication for their PTSD symptoms and that comorbidity between PTSD and alcohol and other substance-use-related problems may develop as a result of this process. Studies that attempt to examine the relationship of childhood trauma with later substance use or substance-use disorders may produce incomplete findings if PTSD symptoms are not taken into account.

Our findings are consistent with those of previous studies (Brown and Wolfe, 1994; Deykin and Buka, 1997) that have found that PTSD and problematic substance use share many risk factors. In our study, child age, child antisocial behavior, and parental monitoring were found to be associated with both PTSD symptoms and alcohol initiation. The observed association between PTSD symptoms and alcohol-use initiation was partially explained by those shared factors, but it did remain significant in multivariate analyses. This pattern highlights the importance of controlling for these crucial factors when examining the relationship between PTSD symptoms and alcohol use.

Limitations

This study is limited by its focus on a particular ethnic group. Because the children in this study were all of Puerto Rican background, caution should be used when generalizing the findings to other ethnic groups. Another limitation pertains to the measurement of PTSD. Because of the low prevalence of PTSD in the community and the young age of this sample, only PTSD symptom counts, rather than definitive diagnoses, were used in our analyses. It should be noted, however, that even subthreshold PTSD has been shown to be associated with impairment and comorbid psychiatric problems in children (Copeland et al., 2007). Also, because of the limited information obtained in the study regarding the characteristics of each child's traumatic experience(s), it was not possible to examine the specific effects of particular types of traumas. It should also be noted that general issues that can interfere with the ability of survey studies to collect accurate information with regard to trauma exposure among children may also have affected our findings. Studies have indicated that a child who has experienced sexual abuse at the hands of a family member or family friend, for example, is unlikely, to disclose information about it to any adult outside of the family until many years after the abuse begins (Fontes, 1993; London et al., 2007; Priebe and Svedin, 2008). The mandated child abuse reporting requirements for survey research may also help to suppress reporting of such experiences by child survey participants (Copeland et al., 2007). Thus, some of the more severe childhood traumas, and those to which girls may be disproportionately subjected, are likely to have been underreported by our study sample. This underreporting may have affected our study's findings with regard to gender differences.

Implications

The findings from this longitudinal study, which examined a wide range of shared risk or protective factors in a large sample of children from a specific ethnic group, have important clinical and policy implications. PTSD tends to be a persistent disorder (Green et al., 1990; Kessler et al., 1995; Kulka et al., 1990; Perkonigg et al., 2005), and early onset of alcohol use increases the risk of later substance-use disorders. The age range covered by this study allowed us to focus on the transition period from childhood to adolescence, when the conditions of interest are beginning to develop; thus, it represents a unique contribution for prevention efforts.

Our finding that family-level risk and protective factors (e.g., parental emotional problems and parental monitoring) are predictive both of alcohol initiation and of PTSD symptoms points to the potential impact of interventions that help parents to improve their parenting skills. The finding that antisocial behaviors are associated with both alcohol initiation and PTSD symptoms also suggests the importance of early intervention for children with antisocial behaviors, given that conduct problems and oppositional behaviors in childhood can be prevented (Olds et al., 1998) and treated (Webster-Stratton et al., 2004), if addressed early in life.

The current study's main finding—that PTSD symptoms in children 10–13 years old may be associated with early onset of alcohol use, whereas exposure to traumatic events with low levels of PTSD symptoms may not—underscores the importance of identifying and treating PTSD-related symptoms in pre-adolescent children. Understanding PTSD symptoms in early adolescents and associated alcohol use, therefore, has direct clinical and policy relevance. Early detection and effective treatment of even subthreshold PTSD may help in delaying subsequent onset of alcohol use by children and adolescents and in reducing the negative impact of alcohol-use disorders over their life span.

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse grant R01 DA0136894 awarded to Ping Wu. The parent study was supported by National Institute of Mental Health grant RO1 MH56401 (Hector Bird, principal investigator) and National Center for Minority Health Disparities grant P20 MD000537-01 (Glorisa J. Canino, principal investigator). Ping Wu, the principal investigator of the current study, who is independent of any commercial funder, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bensley LS, Spieker SJ, Van Eenwyk J, Schoder J. Self-reported abuse history and adolescent problem behaviors: II. Alcohol and drug use. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1999;24:173–180. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00112-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird HR, Canino GJ, Davies M, Duarte CS, Febo V, Ramirez R, Loeber R. A study of disruptive behavior disorders in Puerto Rican youth: I. Background, design and survey methods. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006a;45:1032–1041. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000227878.58027.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird HR, Davies M, Canino G, Loeber R, Rubio-Stipec M, Shen S. Classification of antisocial behaviors along severity and frequency parameters. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2005;14:325–341. [Google Scholar]

- Bird HR, Davies M, Duarte CS, Shen S, Loeber R, Canino G. A study of disruptive behavior disorders in Puerto Rican youth: II. Baseline prevalence, comorbidity and correlates in two sites. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006b;45:1042–1053. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000227879.65651.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird HR, Shrout PE, Davies M, Canino G, Duarte CS, Shen S, Loeber R. Longitudinal development of antisocial behaviors in young and early adolescent Puerto Rican children at two sites. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46:5–14. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000242243.23044.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brems C, Johnson ME, Neal D, Freemon M. Childhood abuse history and substance use among men and women receiving detoxification services. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2004;30:799–821. doi: 10.1081/ada-200037546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Davis GC, Andreski P, Peterson E. Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder in an urban population of young adults. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1991;48:216–222. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810270028003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown PJ, Wolfe J. Substance abuse and post-traumatic stress disorder comorbidity. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1994;35:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(94)90110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casswell S, Stewart J, Connolly G, Silva P. A longitudinal study of New Zealand children's experience with alcohol. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:277–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen DA, Richardson J, LaBree L. Parenting behaviors and the onset of smoking and alcohol use: A longitudinal study. Pediatrics. 1994;94:368–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland WE, Keeler G, Angold A, Costello J. Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress in childhood. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:577–584. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes RC, Fleming CB, Mason W, Catalano RF. Risk factors linking maternal depressed mood to growth in adolescent substance use. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2009;17:49–64. doi: 10.1177/1063426608321690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWit DJ, Adlaf EM, Offord DR, Ogborne AC. Age at first alcohol use: A risk factor for the development of alcohol disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:745–750. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWit ML, Embree BG, DeWit D. Determinants of the risk and timing of alcohol and illicit drug use onset among natives and non-natives: Similarities and differences in family attachment processes. Social Biology. 1999;46:100–121. doi: 10.1080/19485565.1999.9988990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deykin EY, Buka SL. Prevalence and risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder among chemically dependent adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154:752–757. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.6.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan RD, Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG, Hanson RF, Resnick HS. Childhood physical assault as a risk factor for PTSD, depression, and substance abuse: Findings from a national survey. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1996;66:437–448. doi: 10.1037/h0080194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson PL, Tucker JS, Klein DJ. Ten-year prospective study of public health problems associated with early drinking. Pediatrics. 2003;111:949–955. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.5.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JN, Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS. PTSD as a mediator between childhood rape and alcohol use in adult women. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1998;22:223–234. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00133-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flood AM, McDevitt-Murphy ME, Weathers FW, Eakin DE, Benson TA. Substance use behaviors as a mediator between posttraumatic stress disorder and physical health in trauma-exposed college students. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;32:234–243. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9195-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontes LA. Disclosures of sexual abuse by Puerto Rican children: Oppression and cultural barriers. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 1993;2:21–35. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbreth JG. Family structure and inter parental conflict: Effects on adolescent drinking. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska-Lincoln; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Hoven CW, Narrow WE, Cohen P, Fielding B, Alegria M, Dulcan MK. Measurement of risk for mental disorders and competence in a psychiatric epidemiologic community survey: The National Institute of Mental Health Methods for the Epidemiology of Child and Adolescent Mental Disorders (MECA) study. Social Psychiatry. 1998;33:162–173. doi: 10.1007/s001270050039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green BL, Lindy JD, Grace MC, Gleser GC, Leonard AC, Korol M, Winget C. Buffalo Creek survivors in the second decade: Stability of stress symptoms. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1990;60:43–54. doi: 10.1037/h0079168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grice DE, Brady KT, Dustan LR, Malcolm R, Kilpatrick DG. Sexual and physical assault history and posttraumatic stress disorder in substance-dependent individuals. American Journal on Addictions. 1995;4:297–305. [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger ME, Leeb RT, Swahn MH. Childhood maltreatment and early alcohol use among high-risk adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:291–295. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Heeren T, Winter MR. Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence: Age at onset, duration, and severity. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2006;160:739–746. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.7.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Zha W. Age of drinking onset, alcohol use disorders, frequent heavy drinking, and unintentionally injuring oneself and others after drinking. Pediatrics. 2009;123:1477–1484. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson WW. A measurement package for clinical workers. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science. 1982;18:229–238. doi: 10.1177/002188638201800210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelley HH. The effects of childhood trauma on drug and alcohol abuse in college students. Bronx, NY: Fordham University; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB. Stages and pathways of drug involvement: Examining the gateway hypothesis. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulka RA, Schlenger WE, Fairbank JA, Hough RL, Jordan BK, Marmar CR, Grady DA. Trauma and the Vietnam War generation. New York: Brunner/Mazel; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kuperman S, Chan G, Kramer JR, Bierut L, Bucholz KK, Fox L, Schuckit MA. Relationship of age of first drink to child behavioral problems and family psychopathology. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:1869–1876. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000183190.32692.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipschitz DS, Rasmusson AM, Anyan W, Gueorguieva R, Billingslea EM, Cromwell PF, Southwick SM. Posttraumatic stress disorder and substance use in inner-city adolescent girls. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2003;191:714–721. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000095123.68088.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lish JD, Weissman MM, Adams PB, Hoven CW, Bird HR. Family psychiatric screening instrument for epidemiologic studies: Pilot testing and validation. Psychiatry Research. 1995;57:169–180. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(95)02632-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London K, Bruck M, Ceci SJ, Shuman DW. Disclosure of child sexual abuse: A review of the contemporary empirical literature. In: Pipe M-E, Lamb ME, Orbach Y, Cederborg A-C, editors. Child sexual abuse: Disclosure, delay and denial. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2007. pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Iacono WG, Legrand LN, Malone S, Elkins I. Origins and consequences of age at first drink: I. Associations with substance-use disorders, disinhibitory behavior and psychopathology, and P3 amplitude. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2001;25:1156–1165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CA, Kelly TH, Rayens MK, Brogli B, Himelreich K, Brenzel A, Omar H. Sensation seeking and symptoms of disruptive disorder: association with nicotine, alcohol, and marijuana use in early and mid-adolescence. Psychological Reports. 2004;94(3 Pt 1):1075–1082. doi: 10.2466/pr0.94.3.1075-1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowbray CT, Oyserman D. Substance abuse in children of parents with mental illness: Risks, resiliency, and best prevention practices. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2003;23:451–482. [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell L, Stueve A, Duran R, Myint-U A, Agronick G, Doval AS, Wilson-Simmons R. Parenting practices, parents' underestimation of daughters' risks, and alcohol and sexual behaviors of urban girls. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;42:496–502. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds D, Henderson CR, Jr, Cole R, Eckenrode J, Kitzman H, Luckey D, Powers J. Long-term effects of nurse home visitation on children's criminal and antisocial behavior: 15-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;280:1238–1244. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.14.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Stouthamer-Loeber M. The correlation of family management practices and delinquency. Child Development. 1984;55:1299–1307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkonigg A, Pfister H, Stein MB, Hofler M, Lieb R, Maercker A, Wittchen H-U. Longitudinal course of posttraumatic stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in a community sample of adolescents and young adults. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:1320–1327. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priebe G, Svedin CG. Child sexual abuse is largely hidden from the adult society: An epidemiological study of adolescents' disclosures. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2008;32:1095–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN user's manual: Release8.0. Research Triangle Park, NC: Author; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Russo MF, Lahey BB, Christ MAG, Frick PJ, McBurnett K, Walker JL, Green S. Preliminary development of a sensation seeking scale for children. Personality and Individual Differences. 1991;12:399–405. [Google Scholar]

- Russo MF, Stokes GS, Lahey BB, Christ MAG, McBurnett K, Loeber R, Green SM. A Sensation Seeking Scale for Children: Further refinement and psychometric development. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 1993;15:69–86. [Google Scholar]

- Saigh PA, Yasik AE, Sack WH, Koplewicz HS. Child-adolescent posttraumatic stress disorder: Prevalence, risk factors, and comorbidity. In: Saigh PA, Bremner JD, editors. Posttraumatic stress disorder: A comprehensive text. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 1999. pp. 18–43. [Google Scholar]

- Sartor CE, Lynskey MT, Bucholz KK, McCutcheon VV, Nelson EC, Waldron M, Heath AC. Childhood sexual abuse and the course of alcohol dependence development: Findings from a female twin sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;89:139–144. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder DH, Costa PT. Influence of life event stress on physical illness: Substantive effects or methodological flaws? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1984;46:853–863. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.46.4.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher JA, Coffey SF, Stasiewicz PR. Symptom severity, alcohol craving, and age of trauma onset in childhood and adolescent trauma survivors with comorbid alcohol dependence and posttraumatic stress disorder. The American Journal on Addictions. 2006;15:422–425. doi: 10.1080/10550490600996355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): Description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stouthamer-Loeber M, Van Kammen WB. Data Collection and Management: A Practical Guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Filipas HH, Townsend SM, Starzynski LL. Trauma exposure, posttraumatic stress disorder and problem drinking in sexual assault survivors. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:610–619. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldrop AE, Santa Ana EJ, Saladin ME, McRae AL, Brady KT. Differences in early onset alcohol use and heavy drinking among persons with childhood and adulthood trauma. The American Journal on Addictions. 2007;16:439–442. doi: 10.1080/10550490701643484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner LA, White HR. Longitudinal effects of age at onset and first drinking situations on problem drinking. Substance Use and Misuse. 2003;38:1983–2016. doi: 10.1081/ja-120025123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C, Reid M, Hammond M. Treating children with early-onset conduct problems: intervention outcomes for parent, child, and teacher training. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:105–124. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein DW. Posttraumatic stress disorder, dissociation and substance abuse as long-term sequelae in a population of adult children of substance abusers. New York: New York University; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Zlotnick C, Johnson DM, Stout RL, Zywiak WH, Johnson JE, Schneider RJ. Childhood abuse and intake severity in alcohol disorder patients. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2006;19:949–959. doi: 10.1002/jts.20177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA, Donovan JE, Masten AS, Mattson ME, Moss HB. Early developmental processes and the continuity of risk for underage drinking and problem drinking. Pediatrics. 2008;121(Suppl. No. 4):S252–S272. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2243B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]