Abstract

Objective:

Brief interventions in the emergency department targeting risk-taking youth show promise to reduce alcohol-related injury. This study models the cost-effectiveness of a motivational interviewing—based intervention relative to brief advice to stop alcohol-related risk behaviors (standard care). Average cost-effectiveness ratios were compared between conditions. In addition, a cost-utility analysis examined the incremental cost of motivational interviewing per quality-adjusted life year gained.

Method:

Microcosting methods were used to estimate marginal costs of motivational interviewing and standard care as well as two methods of patient screening: standard emergency-department staff questioning and proactive outreach by counseling staff. Average cost-effectiveness ratios were computed for drinking and driving, injuries, vehicular citations, and negative social consequences. Using estimates of the marginal effect of motivational interviewing in reducing drinking and driving, estimates of traffic fatality risk from drinking-and-driving youth, and national life tables, the societal costs per quality-adjusted life year saved by motivational interviewing relative to standard care were also estimated. Alcohol-attributable traffic fatality risks were estimated using national databases.

Results:

Intervention costs per participant were $81 for standard care, $170 for motivational interviewing with standard screening, and $173 for motivational interviewing with proactive screening. The cost-effectiveness ratios for motivational interviewing were more favorable than standard care across all study outcomes and better for men than women. The societal cost per quality-adjusted life year of motivational interviewing was $8,795. Sensitivity analyses indicated that results were robust in terms of variability in parameter estimates.

Conclusions:

This brief intervention represents a good societal investment compared with other commonly adopted medical interventions.

Adolescent drinking is associated with substantial medical consequences and social harm (Bauman and Phongsavan, 1999; Institute of Medicine, 1990; Maio et al., 1994). Drinking and driving is a particular problem (Miller et al., 1998), with approximately 25% of 18-to 19-year-old drivers involved in fatal auto accidents having a positive blood alcohol concentration (Subramanian, 2003).

Reaching at-risk youth and designing effective interventions for alcohol-related problems is critical. One evidence-based approach is to intervene with youth receiving emergency medical treatment for an alcohol-related injury. Monti et al. (1999, 2007) and Spirito et al. (2004) have established that brief interventions conducted with adolescents in an emergency department (ED) reduce subsequent injuries and driving after drinking. Studies with older populations have also shown that ED interventions for problem alcohol use are efficacious in reducing alcohol-related consequences (Gentilello et al., 1999; Helmkamp et al., 2003; Longabaugh et al., 2001). In fact, the American College of Surgeons has mandated as a criterion for accreditation that trauma centers (i.e., EDs) have screening programs for problem drinkers, and that Level 1 centers (the highest level of ED accreditation) provide interventions for problem drinkers (American College of Surgeons, 2006).

Two issues remain regarding the dissemination of brief interventions in the ED. One is the need for evidence that such interventions represent a good public investment given the competing demands for limited medical budgets. The other regards what form of ED intervention to provide, ranging from brief advice from a nurse to more complex interventions provided by specially trained counseling staff. The form of ED intervention will be guided in part by cost-effectiveness considerations.

Various approaches to valuing costs and outcomes have been used in cost-effectiveness studies of substance-use-disorder treatment. Disparate methodologies have made it difficult to compare the relative efficiency of interventions for substance-use disorders, both within the category of substance-use-disorder treatment and with competing medical technologies. Because effective treatment of substance-use disorders can have a beneficial impact on multiple domains of an individual's life, it is difficult to determine an optimal outcome as a standard in cost-effectiveness analysis (Sindelar et al., 2004). Two ED intervention studies have conducted analyses of the economic efficiency of identifying and counseling adults with at-risk alcohol consumption. Kunz et al. (2004) presented incremental cost-effectiveness ratios for an ED-based brief intervention compared with a contact control. This study found it cost $260 to reduce Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (alcohol-problem) scores by 1 point, $220 to reduce weekly drinking by one beverage, and $61 to reduce the probability of heavy drinking by 1%. Gentilello et al. (2005) conducted a cost-benefit analysis based on a simulation of introducing alcohol screening and counseling into an ED and found that savings from reduced future ED use and hospitalizations offset the costs of the brief counseling session. Although these studies are seminal and informative, their results are difficult to benchmark against analyses of other medical technologies.

Cost-effectiveness analysts of medical treatments are increasingly adopting guidelines developed by the Public Health Service (Gold et al., 1996), which recommend a special form of cost-effectiveness analysis—cost-utility analysis. Cost-utility analysis incorporates costs from a societal perspective and uses a uniform outcome—quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) gained from the new intervention. However, it has been a challenge to adopt the QALY outcome within the field of substance-use disorders because there is no established framework for assigning quality-of-life scores to morbidity, mortality, or other deleterious effects of substance-use-disorders (Sindelar et al., 2004).

The aim of this article is to examine the cost-effectiveness of conducting brief alcohol interventions using strategies from motivational interviewing (MI; Miller and Rollnick, 2002) with at-risk teens in the ED. This counseling approach is contrasted with a briefer intervention consisting of advice from a health care professional to reduce harmful drinking and information on treatment options. The analysis adopts two approaches. First, the analysis computes and compares average cost-effectiveness ratios across several outcomes assessed in the original study. Second, we conducted a cost-utility analysis using a conservative estimate of QALYs saved as a result of reduced deaths associated with teen drinking and driving. For the cost-utility analysis, we compute incremental costs and lives saved by the motivational intervention compared with the advice condition, with the latter assumed to be the standard of care. Studies have shown that strategies for screening in the ED for problem drinking can have significantly different yields (Colby et al., 2002). Because two different screening methods for identifying alcohol-involved youth were used in the randomized clinical trial, costs of these two methods are also estimated separately and compared.

Method

Data for this study were derived from a randomized clinical trial described elsewhere but briefly summarized here (Monti et al., 1999). The trial compared one-session MI with standard care (SC) among youths ages 18–19 (N = 94) admitted to the ED of a Level 1 trauma center for drinking-related injuries. Eligible youth were recruited while awaiting evaluation or treatment in the ED, with 67% of eligible youth agreeing to participate. Participants provided informed consent, responded to the baseline assessment, and then were randomized to intervention condition. Follow-up interviews were conducted at 3 months (by phone) and 6 months (in person). Compensation for completing research interviews was $20 at baseline, $10 at 3 months, and $15 at 6 months. The majority of participants were male (64%).

A description of the intervention along with the estimated costs are presented in two separate components: (a) screening to identify alcohol-involved youth in the ED and (b) counseling of identified youth. Costs that are specific to the research protocol of the original clinical trial are excluded from presentation and analysis (Coyle and Lee, 1998).

Screening

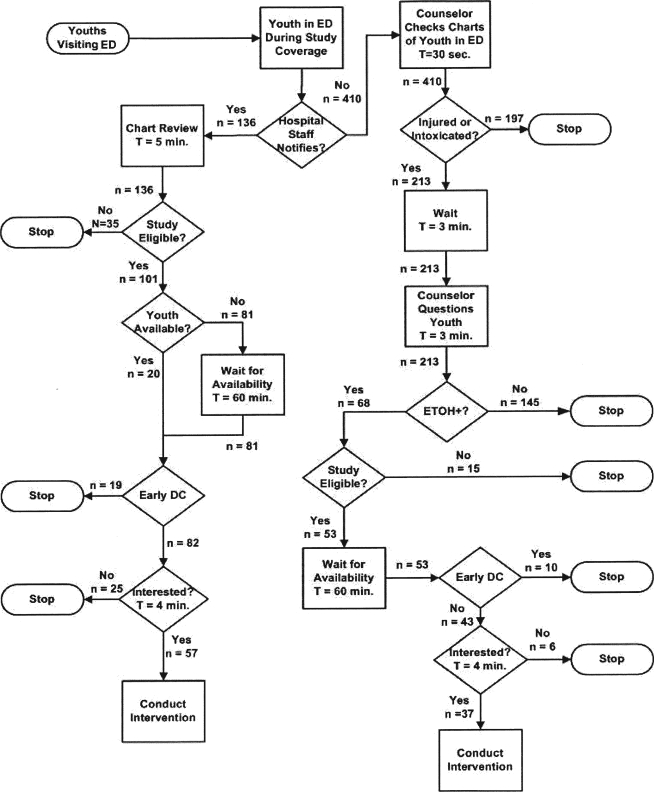

Two methods for patient screening were employed during the study; both approaches are depicted in a process flow chart (Figure 1) with the values indicating the numbers of patients screened and the counselor time each step took to complete. Standard screening involved identification of alcohol involvement by ED staff during the intake interview and/or biochemical test results (67% of patients). Enhanced screening included standard screening but augmented it with proactive screening by counselors who regularly scanned the ED for age-eligible patients and identified those with alcohol involvement by questioning patients directly (33% of patients).

Figure 1.

Process flow chart and time estimates for two screening strategies for alcohol-involved youth in the emergency department (ED). The left-hand side of the flow diagram depicts identification and assessment of alcohol status conducted by hospital staff during routine ED intake (standard screening). The right-hand side of the flow diagram depicts added procedures to proactively scan the ED for youth and solicit information about alcohol involvement (enhanced screening). T = time; sec. = seconds; min. = minute; ETOH+ = alcohol implicated in risk behaviors; DC = discharge.

Intervention conditions

Specially trained counseling staff provided the MI, including a brief assessment, in the ED while patients were waiting for medical evaluation or treatment. In addition to materials used in the MI, participants received handouts on the effects of alcohol and on local alcohol treatment facilities. SC was designed to replicate the best of current practice in EDs, which generally consists of provision of advice to reduce alcohol-related risk. This interaction typically lasted less than 5 minutes, and participants were provided with the same handouts as those in MI.

Measures

Cost-effectiveness.

Four outcomes from the original study were used to compute cost-effectiveness ratios: incidence of drinking and driving, alcohol-related injuries, vehicular citations, and alcohol problems. Each outcome has public health implications, is an indicator of continued problem drinking, or both. Responses for the two follow-up interviews were summed to cover the 6-month period following intervention. In addition, changes in drinking-and-driving rates were used to estimate reduced risk of vehicle crash fatalities.

Drinking and driving was measured by five items from the Young Adult Drinking and Driving Questionnaire (Donovan, 1993), asking the number of times respondents drove after various amounts of drinking. The measure is reliable and valid (Donovan, 1993); internal consistency in this sample was α = .89. Vehicular citations were obtained from Department of Motor Vehicle records. The Adolescent Injury Checklist is a 14-item true-false self-report measure of recent injuries, adapted to measure alcohol involvement, with good internal consistency (α = .68) and validity (Jelalian et al., 1997). Alcohol-related problems were assessed by five items from the Health Behavior Questionnaire (Jessor et al., 1989) that measured frequency of trouble with parents, school, friends, dates, or the police because of drinking on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (five or more times); internal consistency in our sample was α = .63.

Treatment effectiveness.

For the cost-utility analysis, we used the odds ratios (ORs) for improvement in not drinking and driving after the MI (Monti et al., 1999). We used the standard error of this estimate in our simulation modeling (described below) to account for uncertainty in the estimate of MI treatment effect.

Lives saved.

To conduct a cost-utility analysis, an estimate of changes in life expectancy and impact on quality of life associated with high-risk drinking was needed. No published estimates exist on the likelihood of mortality or morbidity associated with the outcomes studied that also control for putative confounds (e.g., individual risk-taking proclivity) and can serve as an estimate of probability of death (or decrements in quality of life) in cost-effectiveness modeling. Therefore, using methods for combining estimates of model parameters from different data sources that are well established in decision analysis (Gold et al., 1996; Muenning, 2002; Petitti, 2000), we sought to apply absolute-risk estimates of mortality to one of the above outcomes. Among these outcomes, the risk of death was most easily estimated from available datasets for drinking and driving. We estimated this absolute risk among 18- to 19-year-olds by modeling incidence and exposure using national data on traffic fatalities and survey data on youth drinking and driving. Because traffic deaths are a relatively rare event in the population, we combined 4 years of national data (2000–2003) to increase the stability of our estimates. Absolute risk is estimated separately by gender to account for differences in alcohol-related relative risk, driving practices, and alcohol-consumption patterns (Williams, 2003; Zador et al., 2000). Within gender, the analysis is stratified by seatbelt use, which is used as a proxy measure of individual risk-taking proclivity.

For the absolute risk, counts of deaths from drinking and driving were derived from the Fatality Analysis and Reporting System, a census of all auto fatalities within the United States (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2001). Although the Fatality Analysis and Reporting System is not a survey with sampling error, estimation procedures based on multiple imputation methods are used to provide data on driver blood alcohol concentration (Rubin et al., 1998; Subramanian, 2002). For this analysis, only deaths from single-vehicle accidents were included to preclude confounding associated with other-vehicle driver error/factors (Zador et al., 2000). By omitting deaths from multiple-vehicle accidents, this study's estimates of alcohol-attributable risk are conservative and, consequently, underestimate the total absolute risk. Analyses examined separately driver deaths and deaths of others involved in an accident with a driver in this age category.

We estimated the total proportion of U.S. drivers ages 18–19 that drink and drive, stratified by gender and seatbelt use, using the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse (which became the National Survey on Drug Use and Health in 2002), a nationally representative survey that examines national trends in alcohol and drug use as well as other associated measures (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2001). The proportions derived from the survey were multiplied by the total number of 18- to 19-year-old licensed drivers (Federal Highway Administration, 2003) to determine the national prevalence of drinking and driving by gender and seatbelt use.

Quality-adjusted life years.

The number of years of life saved was estimated using age-specific mortality rates from National Center for Health Statistics mortality tables (Arias, 2002). Life years saved were weighted (i.e., adjusted for quality of life) by using an estimate of U.S. population-level utilities based on the Health and Activity Limitation Index (Erickson, 1998; Erickson et al., 1995), assuming that population average utilities were the best available estimate for quality of life for individuals in our sample. Each year of added life was weighted by age- and gender-specific utilities and then discounted to the present using a 3% rate (Gold et al., 1996).

Cost of intervention

Perspective.

We adopted two approaches to conducting the cost analysis. First, we assumed the perspective of a provider contemplating adoption of MI. Second, we use a societal perspective to conduct the cost-utility analysis (Gold et al., 1996).

Intervention costs.

We used microcosting techniques to compute the incremental costs associated with delivery of the intervention (Drummond et al., 1997; Horngren et al., 2000; Kaplan and Atkinson, 1998). Staff time estimates for intervention delivery in our study were based on expert estimates made by study staff that managed and/or delivered the intervention. Costs were indexed to 2008 and based on national wage and fringe rates (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2009a, 2009b, 2009c, 2009d, 2009e). For this cost study, the cost of MI assumes that members of the hospital's consultation and liaison team who were specially trained master's-level social workers would conduct the intervention, with time estimates including allotments for transitions between intervening in the ED and other tasks. The costs of SC are assigned assuming a registered nurse provides the intervention and conducts it during an intake interview or debriefing before discharge as part of standard hospital procedures.

For calculating the costs of MI, the estimate of total counseling staff time includes administrative paperwork, preparatory procedures, and waiting for client availability, in addition to 30 minutes of direct client contact time. A conservative estimate of 15 minutes of supervisory time per client provided by a doctoral-level clinician was added. The total counseling staff time devoted to each client in MI comes to about 1 hour 22 minutes, representing $54.80 in direct personnel costs. With the addition of the supervisor's time, the total personnel cost per client for MI is estimated at $67.88. The SC was conservatively estimated to take only 5 minutes of a nurse's time, representing personnel costs of $3.81. This low cost estimate for SC provides a more difficult hurdle for MI to show a more favorable cost-effectiveness ratio. For the societal perspective, opportunity costs for the adolescent participants' time while participating in either intervention were estimated using the minimum wage rate for 2008 (U.S. Department of Labor, 2009).

Other marginal costs of MI were intervention handouts (market value $0.40), a computer program designed for preparing MI feedback used in the intervention (market value $500), and staff training. The computer program and training costs were amortized across patients assuming a useful life of 3 years and intervening with 100 patients per year. Overheads were computed at 25% of intervention costs (Fleming et al., 2000). There were no statistical differences between conditions in the proportion who sought additional treatment for their alcohol misuse, MI = 23%; SC = 18%; χ2(1, n = 83) = 0.29. Consequently, post-ED counseling costs are not included in the analysis, In the sensitivity analysis we address the impact of variations in this assumption.

Accident fatality costs.

For the cost-utility analysis, societal costs saved as a result of averted vehicle crash fatalities are also included. We used estimates produced by Blincoe et al. (2002) for external costs associated with traffic fatalities indexed to 2000. We included medical, legal, administrative, and property damage costs associated with the traffic accident fatality. We excluded estimates of lost productivity because this is implicit in the QALY estimate (Gold et al., 1996). These costs were adjusted to 2008 by using Bureau of Labor Statistics published inflators to a value of $245,642 per fatality.

Analysis

Decision analytical models were created to generate estimates of cost-effectiveness ratios for the interventions based on best estimates (e.g., mean values) of input parameters. To examine stability of the results that are attributable to variability in the key parameter estimates, we conducted a series of one-way and probabilistic sensitivity analyses. In the one-way sensitivity analyses, estimates of each parameter input were individually set at their lower (worst case) and upper (best case) values to examine effects on cost-effectiveness ratios of uncertainty in estimates of single parameters. To simultaneously account for uncertainty across all parameter inputs, we conducted probabilistic sensitivity analysis using Monte Carlo simulation (Doubilet et al., 1985). In each of the 10,000 simulations computed, model inputs were drawn from the data distribution of each parameter (beta for ratios, log-normal for ORs, and triangular for cost data). A cost-effectiveness acceptability curve was generated by computing the proportion of times the estimated incremental cost: QALY ratio for MI fell below willingness-to-pay thresholds ranging from $0 to $120,000 (Fenwick et al., 2001). Cost-effectiveness calculations and sensitivity analyses were conducted with TreeAge Pro (TreeAge Software, Inc., 2009).

Results

Costs

Screening.

The costs of standard screening were estimated to be $75.78. The proactive screening procedures by counselors to scan the ED for eligible adolescents who were not captured through standard screening were estimated at $87.76 per person. The combined costs for enhanced screening included the weighted average estimates for standard screening (61% of participants) and enhanced procedures (39% of participants), resulting in an estimate of $79.19 per youth who participates in the intervention. Consequently, augmenting standard screening with proactive screening (i.e., implementing enhanced screening) has an average cost difference of $3.41 per person enrolled.

Intervention.

Table 1 presents the total costs of MI and SC as well as the incremental costs of MI over SC. For MI, total costs including screening are shown for two scenarios because there would be a managerial choice of which type of screening procedure to use. Using standard screening, the cost of MI totals $169.74 per client. With enhanced screening (i.e., the more intensive screening procedure) the total estimated cost of MI is $173.15. These cost estimates for MI lie between those of two previous studies, with the estimate being closer to that of a study using a marginal costing strategy (Gentilello et al., 2005) than to a study that used an average costing method (Kunz et al., 2004). This relative difference between marginal and average costing methods is consistent with other studies on costs within the ED (Williams, 1996). For perspective, these cost estimates are well above the 2008 reimbursement rates from commercial insurance ($65.51), Medicare ($57.69), and Medicaid ($48.00) (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2008). The SC condition's total cost ($81.04) includes only standard screening, consistent with current practice.

Table 1.

Intervention average costs, clinical outcomes (i.e., effects), and incremental cost-effectiveness (C/E) ratios of motivational interviewing compared with standard care

| C/E ratios |

|||||||||

| Base line |

6-mo. F/U |

||||||||

| Variable | n | % | n | % | Change | Intervention costs | C/E ratio | ||

| Standard care | |||||||||

| Drinking and driving | 39 | 61.5% | 34 | 55.9% | 5.6% | $81.04 | $1,447.14 | ||

| Alcohol-related injuries | 42 | 35.7% | 38 | 50.0% | −14.3% | $81.04 | −$566.71 | ||

| Traffic tickets | 39 | 35.9% | 34 | 29.4% | 6.5% | $81.04 | $1,246.77 | ||

| Alcohol problems |

38 |

60.5% |

|||||||

| Base line |

6-mo. F/U |

Intervention costs Scr. intensity |

C/E ratio Scr. intensity |

||||||

|

n |

% |

n |

% |

Change |

Low |

High |

Low |

High |

|

| Motivational interviewing | |||||||||

| Drinking and driving | 47 | 66.0% | 39 | 35.9% | 30.1% | $169.74 | $173.15 | $563.92 | $575.25 |

| Alcohol-related injuries | 52 | 21.2% | 44 | 20.5% | 0.7% | $169.74 | $173.15 | $24,248.57 | $24,735.71 |

| Traffic tickets | 47 | 42.6% | 38 | 13.2% | 29.4% | $169.74 | $173.15 | $577.35 | $588.95 |

| Alcohol problems |

43 |

51.2% |

|||||||

| Incremental costs |

Incremental C/E ratio |

||||||||

| Incremental change |

Low Scr. |

High Scr. |

Low |

High |

|||||

| Incremental C/E | |||||||||

| Drinking and driving | 24.5% | $88.70 | $92.11 | $362.04 | $375.96 | ||||

| Alcohol-related injuries | 15.0% | $88.70 | $92.11 | $591.33 | $614.07 | ||||

| Traffic tickets | 22.9% | $88.70 | $92.11 | $387.34 | $402.23 | ||||

| Alcohol problems | 9.3% | $88.70 | $92.11 | $953.76 | $990.43 | ||||

Notes: The table presents sample size (n) and prevalence for each measure at baseline and follow-up as well as average cost per person receiving the intervention and C/E ratios (cost divided by change in prevalence). Interpret the C/E ratio as the cost of one person improving from baseline. F/U = follow-up; scr. = screening.

Intervention outcomes

Intervention outcomes are described in greater detail elsewhere (Monti et al., 1999) but are briefly presented here (Table 1). At baseline, groups were not statistically different on scores for drinking and driving, alcohol-related injuries, and vehicular citations. Alcohol problems were not assessed at baseline. The follow-up rate for both 3 and 6 months was 89% (n = 84), with no significant differences between groups. At follow-up, SC participants were significantly more likely than MI participants to drink and drive (OR = 3.92, 95% CI [1.21, 12.72]); suffer alcohol-related injuries (OR = 3.94, 95% CI [1.45, 10.74]); have a vehicular citation, χ2(1, n = 62) = 5.17, p < .05; and experience alcohol-related problems, F(1, 78) = 4.10, p < .05.

Provider cost-effectiveness.

Table 1 presents cost-effectiveness ratios and the comparative analysis between MI and SC. Per-person costs and condition outcomes are shown in the top two sections of the table. The final two columns in this top section show the average cost-effectiveness ratios, indicating the cost for each individual who improved from baseline. For example, the cost of each individual in the SC condition who no longer drank and drove at follow-up was $1,447, compared with $575 in the MI with enhanced screening condition. Interestingly, SC has a negative cost-effectiveness ratio for alcohol-related injuries, which reflects the cost of the group getting worse at follow-up relative to baseline. Across the different outcomes, the MI condition has more favorable cost-effectiveness ratios than SC, irrespective of the method of screening.

Incremental cost-effectiveness analysis.

Another approach to examining relative economic efficiency is to compare incremental change from SC with a new intervention. The bottom part of Table 1 depicts this incremental cost-effectiveness analysis, which presents differences between the two interventions' outcomes and costs. Differences in outcomes all favor MI and are depicted as positive proportions in the table. Differences in costs are also depicted and indicate that MI is more costly per person enrolled than SC, irrespective of the form of screening. The last two columns indicate the costs associated with each individual with a successful outcome if a provider were to switch from SC to MI. Depending on the outcome and type of screening approach, the incremental costs associated with each outcome range from $362 to $990. These estimates for incremental costs of improved outcomes compare favorably with the SC cost-effectiveness ratio and are another indication of the relative efficiency of MI.

Cost-utility analysis

Attributable rates.

The absolute risk of an intoxicated, high-risk male driver dying in a single-vehicle accident was estimated at 65.40 (95% CI [54.23, 76.57]) per 100,000, whereas the absolute risk to a nondriver (i.e., passengers or pedestrians) perishing was 35.02 (95% CI [27.30, 42.75]) per 100,000 drinking-and-driving men. The absolute risk of a drinking-and-driving woman dying was 9.84 (95% CI [−4.23, 23.92]) per 100,000, whereas the absolute risk of a nondriver dying was 0.74 (95% CI [−7.73, 9.22]) per 100,000. Although the confidence intervals for both female drivers' absolute risk encompass the null, we follow guidance of Rothman and Greenland (1998) and Cohen (1994) in determining whether the means we estimated are representative of population effects. In the case of female drivers' risk of mortality, the distribution of the confidence interval is positively skewed with a parameter estimate that is meaningfully above the null. On the other hand, the estimate of absolute risk to a passenger of a female driver is near zero, and the confidence interval is evenly distributed around the null. Consequently, for the cost-utility analysis, we used the absolute-risk estimate for female drivers but not their passengers, In sensitivity analyses, we examined the effect of setting the absolute risk of a female driver death to 0. The average age of a nondriver fatality was 26.4 (SE = 17.3).

Cost per quality-adjusted life year.

Because of differences in absolute risks, estimates of the incremental cost per QALY for individuals counseled with MI are presented separately by gender. For men, an estimated 0.0071 QALYs were saved for each individual in MI, with a cost-effectiveness ratio of $2,414 per QALY. For women, an estimated 0.0007 QALYs were saved for each individual in the intervention, with a cost-effectiveness ratio of $121,469 per QALY. The cost-effectiveness ratio for both genders combined was estimated at $8,795 per QALY.

Sensitivity analyses

For clarity of exposition, we focused sensitivity analyses on the cost-utility parameters because results would also be relevant to the other outcomes. Table 2 presents the main modeling assumptions, worst- and best-case estimates of these assumptions, and the impact of changes in these assumptions on the cost-utility of MI. For sensitivity analyses, costs of interventions and traffic fatality costs averted were varied by 20%. Types and frequency of treatment varied widely among the 21% of participants who sought further counseling (e.g., one session of alcohol education, self-help meetings, psychotherapy), with a wide range in costs. For the sensitivity analysis, we used a conservative value of $810 (i.e., 10 sessions at a rate of $81 each) for a course of treatment and up to 5% incremental extra-treatment participation rate for MI. For other estimated parameters, we used 95% confidence intervals as the plausible range of values.

Table 2.

Sensitivity analyses for cost-utility analysis of cost per quality-adjusted life year ($/QALY) of motivational interviewing (MI) under varying assumptions

| Parameter assumption |

MI $/QALY |

||||

| One way-sensitivity analyses | Base case | Worse case | Best case | Worse case | Best case |

| Motivational interviewing costs | |||||

| Counseling | $173 | $220 | $145 | $18,500 | $2,960 |

| Patient time | $3.28 | $6.00 | $0.00 | $9,360 | $8,116 |

| Follow-on counselinga | 0% | 5% | 0% | $15,350 | $8,795 |

| Standard care costs | |||||

| Counseling | $81 | $65 | $100 | $12,120 | $4,865 |

| Patient time | $0.55 | $0.00 | $1.10 | $8,908 | $8,680 |

| Traffic fatality cost | $245,642 | $200,000 | $300,000 | $10,814 | $6,391 |

| Odds ratio MI treatment | 3.92 | 1.21 | 12.72 | $119,692 | $2,342 |

| AR male driver death | 65.40 | 54.23 | 76.57 | $11,146 | $6,903 |

| AR other death, male driver | 35.02 | 27.30 | 42.75 | $10,297 | $7,485 |

| AR female driver death | 9.84 | 0.00 | 23.92 | $9,893 | $7,414 |

Notes: Follow-on counseling is the incremental proportion of clients seeking additional treatment relative to standard care times an estimated cost of $810. AR = absolute risk of mortality per 100,000.

The one-way sensitivity analyses for each of the worst-case assumptions shown in Table 2 indicate relatively low costs per QALY except for the OR for the MI treatment effect. Because of the relatively large confidence interval of the OR for the MI treatment effect, the model suggests that the economic case for MI is notably weakened at the low end of estimated treatment effects. Other notable worst-case results were the cost of MI and participation rate in follow-on counseling; albeit, these still indicate relatively favorable cost-utility ratios. A separate analysis examined the threshold at which the cost of MI and participation rate in follow-on treatment would lead to a result that exceeded $50,000, a common, albeit controversial benchmark for cost-effectiveness (Ubel et al., 2003). To cross this benchmark, the incremental cost of MI would have to exceed $370 (214% of our estimate) and the incremental follow-on treatment participation rate for MI would have to exceed 28%.

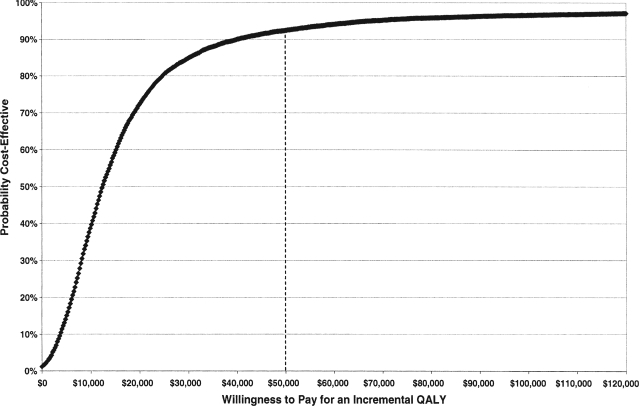

Finally, the results of the probabilistic sensitivity analysis are depicted in the cost-effectiveness acceptability curve shown in Figure 2. Fifty percent of the simulations had a cost per QALY that fell below a willingness to pay of $12,240. At the highest end of the curve, 92% of the simulations fell below a willingness-to-pay threshold of $50,000, and 97% fell below a willingness-to-pay threshold of $100,000.

Figure 2.

Motivational interviewing (MI) cost-effectiveness acceptability curve: Probabilistic sensitivity analysis results demonstrating proportion of times the cost per quality-adjusted life year ($/QALY) for MI fell below different thresholds of willingness to pay in a 10,000-simulation Monte Carlo analysis.

Discussion

This study found that an MI intervention that targets youth in the ED with alcohol-related injuries is cost efficient in comparison with brief advice from a nurse. Although providing brief advice about alcohol-related problems from a nurse or other ED staff member may be a low-cost approach to meeting certification criteria for a trauma center, this level of care has costs associated with the use of staff time. Our analyses indicate that an intervention provided by trained individuals from the psychiatric consultation and liaison team or social work staff can provide more effective results at relatively small incremental costs. From the societal perspective, the cost per QALY gained is low and compares very favorably with other medical interventions that have been widely adopted (Tengs et al., 1995). Notably, the cost per QALY is more favorable than that of government-mandated seatbelt use (Graham et al., 1997).

This cost-utility analysis based on drinking-and-driving deaths provides a conservative estimate of costs and QALYs saved because we do not include savings or QALYs gained from avoiding other types of injury or property damage associated with drinking and driving (i.e., multiple-vehicle traffic fatalities and nonfatal accident injuries) or with other behavior while intoxicated. A premise of this study is that it is sufficient for informing policy to demonstrate that MI is cost-efficient compared with other medical intervention even though we have focused on just one outcome of the intervention rather than attempting to cost out savings from all the changes in behavior associated with MI. Other alcohol-related behaviors that were not included in the analysis are also associated with great costs to society in terms of health care, property damage, and increased morbidity and mortality (Hingson et al., 2002; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2000; Rockett et al., 2005). Consequently, the cost per QALY computed here represents an upper-bound estimate of the cost-effectiveness of this intervention. In addition, we consider traffic fatalities averted only in the year after the intervention rather than assume an enduring effect of the intervention on future drinking and driving. Although the intervention compares favorably with other medical interventions at this level, the “true” value of the cost-effectiveness ratio is presumed to be even more favorable.

In addition to reduced drinking and driving, the marginal costs per outcome favored MI across the diverse outcomes examined in the original clinical trial: alcohol-related injuries, traffic citations, and alcohol-related social and intra-personal consequences. MI was more economically efficient in producing favorable outcomes than SC even though the former is more costly per patient enrolled. Another approach to evaluating cost-effectiveness ratios is to compare these with a benchmark rate that policymakers have indicated is an acceptable investment in a particular outcome. This approach compares the cost of an intervention with an estimate of a society's willingness to pay for a particular type of public health outcome (Sindelar et al., 2004). If SC is representative of what can be considered a revealed (i.e., an implied) willingness to pay by administrators for reducing alcohol-related consequences, then MI represents a much better public health value.

Because young men have a higher risk profile than women (Danseco et al., 2000; Williams, 2003; Zador et al., 2000), the results demonstrate a stronger economic case in favor of providing brief interventions for men rather than women. One implication of this is that policymakers may consider specifically targeting alcohol-involved men in the ED.

Some caveats regarding the study must be considered. First, the analysis is based on one clinical trial with a relatively small sample and a 6-month follow-up window. However, the trial demonstrated robust results across multiple dimensions of alcohol-involved behavior and included objective data from a Department of Motor Vehicles database of vehicular citations. Other studies of interventions in the ED have found similar outcomes with younger and older samples (Gentilello et al., 1999; Helmkamp et al., 2003; Longabaugh et al., 2001; Monti et al., in press; Spirito et al., 2004). To address the question of uncertainty in our estimate of treatment effect, we conducted both one-way and probabilistic sensitivity analyses that incorporated the 95% confidence interval of the impact on drinking and driving. At the lowest end of the interval, the economic rationale for MI weakens but still remains favorable relative to other widely accepted medical technologies (Tengs et al., 1995). In the probabilistic sensitivity analysis, even with a wide distribution for the treatment effect, MI had a relatively low cost per QALY in the vast majority of the simulated replications.

A second limitation is that the approach to estimating QALYs gained relies on parameter estimates derived from population-based studies rather than directly from study data. This was necessary because the original study was not designed to assess impacts on youth mortality. Although this approach is well established in decision analysis, it is predicated on the assumption that the population that was studied in the intervention trial is representative of the population in the larger survey studies (Gold et al., 1996; Muenning, 2002; Petitti, 2000). We tested whether our conclusions would be affected by imprecision from these population-based estimates and found that the model results remain consistent across large variations in these key parameter estimates.

In conclusion, the MI intervention in the ED represents a good public health value. As with other interventions, there may be concerns about the effectiveness of MI in real-world settings, given lower experimental control. However, there have been consistent calls for greater implementation of brief interventions in emergency settings (Hungerford and Pollock, 2003; McDonald et al., 2004). The MI we studied was designed to integrate with ED operations and consequently is readily deployable to other settings. One advantage of an ED-based intervention is that it targets patients involved in risky alcohol consumption, leading to efficient investment in interventions that address a costly public health problem. Within this study, we also present two alternative screening procedures. Although the more intensive screening procedure is not much more costly than the lower intensity one (e.g., 4.5% greater costs), decision makers can determine for themselves which approach best suits their system. The MI intervention efficiently targets high-risk youth engaged in behaviors that have significant societal impact. In comparison with other medical interventions commonly adopted, this intervention represents a good investment.

Acknowledgment

We thank Jane Wheeler for her assistance in preparing this manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) training grant T32 AA07459, NIAAA research grant R01-AA09892, National Cancer Institute grant K07 CA909961 to Charles J. Neighbors, and a Department of Veterans Affairs Research Career Scientist Award to Damaris J. Rohsenow and Senior Research Career Award to Peter M.Monti.

References

- American College of Surgeons. Resources for the optimal care of injured patient. Chicago, IL: Author; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Arias E. United States life tables, 2000. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2002;51:1–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman A, Phongsavan P. Epidemiology of substance use in adolescence: Prevalence, trends and policy implications. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1999;55:187–207. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blincoe L, Seay A, Zaloshnja E, Miller T, Romano E, Luchter S, Spicer R. The economic impact of motor vehicle crashes, 2000. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2008 National occupational employment and wage estimates: Clinical, Counseling, and School Psychologists. 2009a. Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/oes/2008/may/oesl93031.htm.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2008 National occupational employment and wage estimates: Family and General Practitioners. 2009b. Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/oes/2008/may/oes291062.htm.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2008 National occupational employment and wage estimates: Mental Health and Substance Abuse Social Workers. 2009c. Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/oes/2008/may/oes211023.htm.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2008 National occupational employment and wage estimates: Substance Abuse and Behavioral Disorder Counselors. 2009d. Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/oes/2008/may/oes211011.htm.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2009 National occupational employment and wage estimates: Registered Nurses. 2009e. Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/oes/2008/may/oes291111.htm.

- Cohen J. The earth is round (p < .05) AmericanPsychologist. 1994;49:997–1003. [Google Scholar]

- Colby SM, Barnett NP, Eaton CA, Spirito A, Woolard R, Lewander W, Monti PM. Potential biases in case detection of alcohol involvement among adolescents in an emergency department. Pediatric Emergency Care. 2002;18:350–354. doi: 10.1097/00006565-200210000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle D, Lee KM. The problem of protocol driven costs in pharmacoeconomic analysis. Pharmacoeconomics. 1998;14:357–363. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199814040-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danseco ER, Miller TR, Spicer RS. Incidence and costs of 1987-1994 childhood injuries: demographic breakdowns. Pediatrics. 2000;105:E27. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.2.e27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan JE. Young adult drinking-driving: Behavioral and psy-chosocial correlates. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1993;54:600–613. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1993.54.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doubilet P, Begg CB, Weinstein MC, Braun P, McNeil BJ. Probabilistic sensitivity analysis using Monte Carlo simulation: A practical approach. Medical Decision Making. 1985;5:157–177. doi: 10.1177/0272989X8500500205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond MF, O'Brien B, Stoddart GL, Torrance GW. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. New York: Oxford University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson P. Evaluation of a population-based measure of quality of life: The Health and Activity Limitation Index (HALex) Quality of Life Research. 1998;7:101–114. doi: 10.1023/a:1008897107977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson P, Wilson R, Shannon I. Years of healthy life. Healthy People 2000 (Statistical Notes, No. 7) Washington, DC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Center for Health Statistics; 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Highway Administration. Highway Statistics 2001. 2003. Retrieved from www.fhwa.dot.gov/ohim/hs01/dlinfo.htm.

- Fenwick E, Claxton K, Sculpher M. Representing uncertainty: The role of cost-effectiveness acceptability curves. Health Economics. 2001;10:779–787. doi: 10.1002/hec.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming MF, Mundt MP, French MT, Manwell LB, Stauffacher EA, Barry KL. Benefit-cost analysis of brief physician advice with problem drinkers in primary care settings. Medical Care. 2000;38:7–18. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200001000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentilello LM, Ebel BE, Wickizer TM, Salkever DS, Rivara FP. Alcohol interventions for trauma patients treated in emergency departments and hospitals: A cost benefit analysis. Annals of Surgery. 2005;241:541–550. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000157133.80396.1c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentilello LM, Rivara FP, Donovan DM, Jurkovich GJ, Daranciang E, Dunn CW, Ries RR. Alcohol interventions in a trauma center as a means of reducing the risk of injury recurrence. Annals of Surgery. 1999;230:473–480. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199910000-00003. discussion 480–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold MR, Siegel J, Russell LB, Weinstein MC, editors. Cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Graham JD, Thompson KM, Goldie SJ, Segui-Gomez M, Weinstein MC. The cost-effectiveness of air bags by seating position. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;278:1418–1425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmkamp JC, Hungerford DW, Williams JM, Manley WG, Furbee PM, Horn KA, Pollock DA. Screening and brief intervention for alcohol problems among college students treated in a university hospital emergency department. Journal of American College Health. 2003;52:7–16. doi: 10.1080/07448480309595718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Heeren T, Zakocs RC, Kopstein A, Wechsler H. Magnitude of alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:136–144. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horngren CT, Foster G, Datar SM. Cost accounting: A managerial emphasis. 10th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hungerford DW, Pollock DA. Emergency department services for patients with alcohol problems: Research directions. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2003;10:79–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb01982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Broadening the base of treatment for alcohol problems. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelalian E, Spirito A, Rasile D, Vinnick L, Rohrbeck C, Arrigan M. Risk taking, reported injury, and perception of future injury among adolescents. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1997;22:513–531. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/22.4.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Donavan JE, Costa FM. Health Behavior Questionnaire. Boulder, CO: University of Colorado; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan RS, Atkinson AA. Advanced management accounting. 3rd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kunz FM, Jr, French MT, Bazargan-Hejazi S. Cost-effectiveness analysis of a brief intervention delivered to problem drinkers presenting at an inner-city hospital emergency department. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:363–370. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longabaugh R, Woolard RE, Nirenberg TD, Minugh AP, Becker B, Clifford PR, Gogineni A. Evaluating the effects of a brief motivational intervention for injured drinkers in the emergency department. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62:806–816. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald AJ, 3rd, Wang N, Camargo CA., Jr US emergency department visits for alcohol-related diseases and injuries between 1992 and 2000. Archives of lntern Medicine. 2004;164:531–537. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.5.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maio RF, Portnoy J, Blow FC, Hill EM. Injury type, injury severity, and repeat occurrence of alcohol-related trauma in adolescents. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1994;18:261–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TR, Lestina DC, Spicer RS. Highway crash costs in the United States by driver age, blood alcohol level, victim age, and restraint use. Accident Analysis and Prevention. 1998;30:137–150. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(97)00093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Monti PM, Barnett NP, Colby SM, Gwaltney CJ, Spirito A, Rohsenow DJ, Woolard R. Motivational interviewing versus feedback only in emergency care for young adult problem drinking. Addiction. 2007;102:1234–1243. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti PM, Barnett NP, Colby SM, Gwaltney CJ, Spirito A, Rohsenow DJ, Woolard R. Motivational interviewing vs. feedback only in emergency care for young adult problem drinking. Addiction. in press doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti PM, Colby SM, Barnett NP, Spirito A, Rohsenow DJ, Myers M, Lewander W. Brief intervention for harm reduction with alcohol-positive older adolescents in a hospital emergency department. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:989–994. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muenning P. Designing and conducting cost-effectiveness analyses in medicine and health care. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. 2001 Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS) 2001. Retrieved from ftp://ftp.nhtsa.dot.gov/FARS/2001.

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Tenth special report to the U.S. Congress on alcohol and health: Highlights from current research (NIH Publication No. 00–1583) Bethesda, MD: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Petitti DB. Meta-analysis, decision analysis, and cost-effectiveness analysis: Methods for quantitative synthesis in medicine. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rockett IR, Putnam SL, Jia H, Chang CF, Smith GS. Unmet substance abuse treatment need, health services utilization, and cost: A population-based emergency department study. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2005;45:118–127. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman KJ, Greenland S. Modern Epidemiology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB, Schafer JL, Subramanian R. Multiple imputation of missing blood alcohol concentration (BAC) values in FARS. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Sindelar JL, Jofre-Bonet M, French MT, McLellan AT. Cost-effectiveness analysis of addiction treatment: Paradoxes of multiple outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;73:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spirito A, Monti PM, Barnett NP, Colby SM, Sindelar H, Rohsenow DJ, Myers M. A randomized clinical trial of a brief motivational intervention for alcohol-positive adolescents treated in an emergency department. Journal of Pediatrics. 2004;145:3, 96–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian R. Transitioning to multiple imputation: A new method to estimate missing blood alcohol concentration (BAC) values in FARS. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian R. Alcohol involvement in fatal crashes 2001. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Household Survey on Drug Abuse, 2001. 2001. Retrieved 3/20/04, from http://webapp.icpsr.umich.edu/cocoon/SAMHDA-STUDY/03580.xml.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Coding for SBI Reimbursement. 2008. Retrieved from http://sbirt.samhsa.gov/coding.htm.

- Tengs TO, Adams ME, Pliskin JS, Safran DG, Siegel JE, Weinstein MC, Graham JD. Five-hundred life-saving interventions and their cost-effectiveness. Risk Analysis. 1995;15:369–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.1995.tb00330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TreeAge Software Inc. TreeAge Pro Healthcare Module (2009 Edition) Williamstown, MA: Author; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ubel PA, Hirth RA, Chernew ME, Fendrick AM. What is the price of life and why doesn't it increase at the rate of inflation? Archives of lnternal Medicine. 2003;163:1637–1641. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.14.1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Labor. Fair Labor Standards Act. 2009. Retrieved from http://www.dol.gov/whd/flsa/index.htm.

- Williams AF. Teenage drivers: Patterns of risk. Journal of Safety Research. 2003;34:5–15. doi: 10.1016/s0022-4375(02)00075-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams RM. The costs of visits to emergency departments. New England Journal of Medicine. 1996;334:642–646. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603073341007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zador PL, Krawchuk SA, Voas RB. Alcohol-related relative risk of driver fatalities and driver involvement in fatal crashes in relation to driver age and gender: An update using 1996 data. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61:387–395. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]