Abstract

Objective:

Understanding developmental differences in reasons for quitting substance use may assist clinicians in tailoring treatments to different clinical populations. This study investigates whether alcohol-disordered and problem-drinking emerging adults (i.e., ages 18–25 years) have different reasons for quitting than younger adolescents (i.e., ages 13–17 years)

Method:

Using a large clinical sample of emerging adults and adolescents, we compared endorsement rates for 26 separate reasons for quitting between emerging adults and adolescents who were matched on clinical severity. Then age group was regressed on total, interpersonal, and personal reasons for quitting, and mediation tests were conducted with variables proposed to be developmentally salient to emerging adults.

Results:

Among both age groups, self-control reasons were the most highly endorsed. Emerging adults had significantly fewer interpersonal reasons for quitting (Cohen's d = 0.20), and this association was partially mediated by days of being in trouble with one's family. There were no differences in personal reasons or total number of reasons for quitting.

Conclusions:

Our findings are consistent with developmental theory suggesting that emerging adults experience less social control, which here leads to less interpersonal motivation to refrain from alcohol and drug use. As emerging adults in clinical samples may indicate few interpersonal reasons for quitting, one challenge to tailoring treatments for them will be identifying innovative ways of leveraging social supports and altering existing social networks.

Alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders are common during adolescence (i.e., ages 13–17) and emerging adulthood (i.e., ages 18–25; Arnett, 2000; Blanco et al., 2008; Rueter et al., 2007). However, the prevalence of alcohol-use disorders and heavy episodic drinking is higher among emerging adults when compared with any other age group. For example, in the 2007 National Survey of Drug Use and Health, approximately 46% of emerging adults ages 21–25 reported such heavy intake of alcohol during the past month, and nearly 15% of those ages 18–25 reported heavy drinking on 5 or more days out of the past 30 days (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2008). In addition, approximately 70% of adolescents have consumed alcohol by their senior year in high school (Johnston et al., 2007), and such widespread underage drinking is estimated to incur social costs of more than $60 billion per year (Miller et al., 2006).

Finding methods to increase treatment utilization and retention among emerging adults and adolescents is a research priority. Specialty sector-provided treatments are grossly underutilized, and a major reason for this is the perception by those with alcohol- and drug-use problems that treatment is unnecessary (Grant, 1997). Studies have shown that both motivation for treatment and readiness for change wane with increasing age (DiClemente et al., 2009; Handelsman et al., 2005; Melnick et al., 1997), but no study has had a large enough sample of adolescents and young adults to examine age differences in specific reasons for quitting. Such knowledge could assist practitioners in refining clinical engagement strategies, because treatment entry remains low even among youth presenting for assessment (Smith et al., 2009). Therefore, the aims of this article are to investigate differences in reasons for quitting between emerging adults and adolescents and to test whether any age differences in reasons for quitting are the result of developmental differences.

Readiness for change and reasons for quitting

Below we provide a brief review of the readiness and reasons for quitting literatures, highlighting findings pertinent to emerging adults and adolescents. Here readiness to change refers to a global and multifaceted construct of why people decide to initiate and maintain behavior changes either with or without professional treatment. A comprehensive overview of the multiple constructs used to measure readiness to change is available (Carey et al., 1999). Readiness to change is not to be confused with specific reasons for quitting, which here will refer to individuals' reasons for wanting to quit, regardless of whether they have started taking steps toward quitting. Comparatively, fewer studies exist on specific reasons for quitting, and no study has compared differences in reasons for quitting between emerging adults and adolescents.

Readiness to change.

The Transtheoretical Model, commonly referred to as the Stages of Change model, is the most well-known theoretical model of why people make behavior changes (Prochaska et al., 1992). The Transtheoretical Model specifies several stages in which individuals can be classified depending on whether they have no desire or perceived need to change (precontemplation), are considering making changes (contemplation), are preparing to change (preparation), are actively making behavior changes (action), or are maintaining changes they have already made (maintenance). In studies using adult samples, findings have been mixed on whether stage-of-change classifications predicted post-treatment substance-use outcomes. Two studies supported such predictive validity (Carbonari and DiClemente, 2000; Henderson et al., 2004), and two failed to find that stage of change was a significant predictor of treatment outcomes (Blanchard et al., 2003; Callaghan et al., 2008).

A very limited number of studies, however, have used the categorical stages of change approach with adolescents, and adult studies have not reported findings for emerging adults separately. Adolescents in precontemplation have been shown to have lower reductions in substance use and drop out of treatment more than adolescents classified in other stages of change (Cady et al., 1996; Callaghan et al., 2005).

Other readiness for change studies.

Rather than using stage-based categorizations, large adolescent and emerging adult studies have also measured readiness for change by focusing on external pressure to make changes, the attractiveness of the intervention(s) being offered, and outside obligations and influences that may prevent an individual from entering treatment (De Leon et al., 1994; Melnick et al., 1997). Melnick et al. (1997) reported an inverse relationship between age and readiness for change among those in therapeutic communities. Broome et al. (2001) modified De Leon's Circumstances, Motivation, Readiness and Suitability (or CMRS) scale for adolescents in the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study-A (or DATOS-A) research and showed that readiness predicts treatment engagement. This is an important finding because stronger working alliances predict treatment outcomes among both adults and adolescents (Hiller et al., 2002; Tetzlaff et al., 2005) and moderate the relationship between baseline motivation and posttreatment alcohol-use outcomes for adults (Ilgen et al., 2006). Finally, Handlesman et al. (2005) used separate structural equation models for adolescents and adults to examine predictors of readiness to change. Substance-related consequences were the strongest predictors of readiness to change, with predictors similar across age groups.

Reasons for quitting.

A few research studies have investigated specific reasons why persons with substance-use disorders want to quit using substances. To date, however, results for emerging adults have not been reported separately in adult studies.

Among marijuana- and cocaine-using adults, McBride et al. (1994) examined the factor structure of a scale containing reasons for quitting. They identified four factors, which were labeled health concerns (i.e., because I have noticed physical symptoms), self-control (i.e., to show that I can quit if I really want to), social influence (i.e., because people close to me will be upset if I don't quit), and legal (i.e., because of legal problems). In their study, intrinsic motivation (health minus social-influence scores) did not predict 3-month abstinence. Downey et al. (2001) had similar results but found cross-loading among legal and social-influence items. They also found that both intrinsic motivation and total intrinsic motivation (i.e., intrinsic minus extrinsic motivation) were positively associated with abstinence at follow-up. Extrinsic motivation, however, was negatively associated with abstinence. They hypothesized that once substance users reach a threshold where they have accrued numerous severe consequences (i.e., loss of job or freedom), extrinsic pressure to quit becomes less important. It is unclear if this principle holds true for adolescents and emerging adults who may not have experienced harsh substance-related consequences.

Godley et al. (2001) adapted these items for adolescents (n = 584) and reported a factor solution with notable differences from the adult analyses above. Specifically, their personal motivation dimension included a combination of health, self-control, and social items (i.e., because won't have to leave social functions). Further, there was less cross-loading between social-influence and legal items, and weak correlations between interpersonal and legal motivation composite scale scores (r = .04). Thus, for adolescents, social influence from family and friends, or interpersonal motivation, was distinct from legal pressure. Similar to the adult studies reported above, they found that higher personal motivation (i.e., intrinsic) scores predicted reduced substance use at 3 months, but legal and interpersonal motivation did not significantly predict posttreatment substance use. Interpersonal motivation, however, did predict treatment completion.

What is emerging adulthood?

Emerging adulthood is a proposed developmental stage occurring between the ages of 18 and 25, which is said to be marked by an intense exploration of values and beliefs, feeling as if one is not quite an adolescent nor an adult (i.e., feeling in-between), and greater autonomy than is experienced during adolescence. In adolescence, more structured social controls (i.e., parents and guardians) and stronger connections to institutions (i.e., schools) are in place (Arnett, 2000, 2005; Park et al., 2006). Arnett (2000) conceptualized emerging adulthood as a unique stage of development, highlighting broad demographic trends (i.e., delayed marriage age, starting a career-track job) indicative of delays in the onset of adult roles. Although adolescence has been thought of as the developmental period crucial to identity development (Erikson, 1959), these demographic changes are hypothesized to render emerging adulthood as an important period for resolving identity issues. Thus, substance misuse interventions may be especially crucial during this time in efforts to interrupt substance-use patterns and facilitate transitions to prosocial adult identities. Recent research shows that individuals ages 18–25 who have resolved identity issues, and consider themselves to be adults, engage in fewer higher risk behaviors (Nelson and Barry, 2005).

Emerging adults' treatment readiness and reasons for quitting.

National estimates indicate that only a small fraction of those with substance-use disorders ever receive substance-use-disorder treatment (Park et al., 2006; SAMHSA, 2003). Epidemiological research also underscores young adults' ambivalence about entering treatment. For example, among a nationally representative sample of young adults with alcohol-use disorders perceiving a need for alcoholism treatment but not receiving it, 24.9% said they did not feel their problem was serious enough to warrant professional treatment (Grant, 1997). Furthermore, special efforts are likely needed for engaging and retaining young adults in treatment, because those ages 18–25 appear less motivated for and more difficult to retain in treatment when compared with older adults (Satre et al., 2003; Sinha et al., 2003). Although prior work has shown that accumulating more reasons for quitting (McBride et al., 1994) predicts treatment outcomes for both adolescents and adults (Downey et al., 2001; Godley et al., 2001), and qualitative work has explored trends in adolescents' reasons for quitting (Titus et al., 2007), no empirical study to date has focused on the self-endorsed reasons for quitting among emerging adults.

Why emerging adults' reasons for quitting may differ from adolescents'.

Studies have consistently shown an association between age and readiness for change, which is hypothesized to be the result of a longer substance-use history that results in increasingly more consequences (DiClemente et al., 2009; Handelsman et al., 2005; Melnick et al., 1997). Thus, although it has never been examined, it seems logical that emerging adults should, on average, endorse more overall reasons for quitting compared with younger adolescents.

Emerging adults often have greater network support (Andrews et al., 2002; Delucchi et al., 2008) for drinking and experience multiple transitions in housing, relationships, and employment. These transitions are hypothesized to reduce social control, which could deter problematic drinking and drug use (Arnett, 2005; Brown et al., 2008). Conversely, minimizing transitions, such as continuing to live at home, could be protective against alcohol use. For example, White et al. (2008) found that emerging adults living at home while attending college were lower on all alcohol-use indices in the spring following their senior year when compared with non-college students away from home, non-college students at home, and college students living away from home. Furthermore, this study also found that non-college-attending emerging adults living away from their parents had higher alcohol use than most other college/residential status groups. Substance-misusing emerging adults may not feel social pressure to reduce substance use if they are not living at home, and even less if they self-select into peer groups where such pressure is absent. As more emerging adults are expected to be in independent living situations when compared with adolescents, it is possible that the presence of parents in one's home residence may mediate an association between age and interpersonal reasons for quitting.

Another variable that may potentially mediate an association between age and interpersonal reasons for quitting is level of family conflict. Relationship dynamics change between parents and children during their transition out of adolescence, with parent-child relationships becoming more egalitarian and less conflicted (De Goede et al., 2009; Furman and Buhrmester, 1992). It is unclear whether this general trend toward a more hands-off parenting approach will translate into less family conflict among families with emerging adults who are using substances and present for treatment. Nevertheless, based on findings from these longitudinal studies of parent-child relationships from adolescence through emerging adulthood, we may expect that family conflict will be lower for emerging adults than for adolescents, and that this may mediate associations between age and interpersonal reasons for quitting.

Summary and hypotheses.

In summary, we hypothesize that emerging adults will have more overall reasons for quitting and fewer interpersonal reasons for quitting. Furthermore, we hypothesize that two variables, living with one's parents and family conflict, will mediate associations between age and interpersonal motivation.

Method

Participants and setting

Data were obtained from the GAIN Coordinating Center, a division of Chestnut Health Systems in Bloomington, Illinois. The GAIN Coordinating Center developed the Global Appraisal of Individual Needs (GAIN; Dennis et al., 2002), a reliable and valid family of instruments used in multiple adolescent and adult substance-use-disorder treatment studies. Furthermore, in addition to its use in controlled studies, the GAIN has been used by hundreds of treatment agencies and national demonstration projects funded by SAMHSA over the past 10 years. Because it is a standardized instrument in widespread use, data from both these controlled studies and SAMHSA-funded demonstration projects are pooled and made available to researchers under Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act-compliant data-sharing agreements. Such data pooling enables investigations of research questions (e.g., age differences in reasons for quitting) that would be left unanswered by individual studies, which may lack adequate subgroup samples and statistical power (Miller et al., 2007). Data from these studies and SAMHSA-funded treatment agency evaluations were collected with approval from each organization's institutional review board. A detailed description of this data source and overview of the full sample characteristics is available (Dennis et al., 2009).

Study inclusion criteria.

Participants in this study are a subset of the adolescents (n = 9,450) and young adults (n = 946) who received treatment from 116 substance-use-disorder treatment agencies between 1998 and 2007 and completed the reasons for quitting questions. Among these participants, emerging adults (n = 642) and adolescents (n = 5,155) who (a) met the lifetime criteria for alcohol-use disorders, (b) were considered diagnostic orphans (with less than three but greater than one dependence symptom; Pollock and Martin, 1999), or (c) used alcohol on a weekly basis in the 90 days before their intake interview were selected. Participants in the weighted analysis sample (see below) were mostly individuals meeting the criteria for alcohol abuse (54.2%), with the remainder of the sample comprised of weekly alcohol users (26.1%), those dependent on alcohol (17.4%), and diagnostic orphans (7.8%). The majority (57%) of weekly users that did not meet full or subthreshold alcohol-use-disorder criteria were weekly heavy episodic drinkers.

Measures

All scales and items used to match emerging adults and adolescents on clinical severity are part of the larger Global Appraisal of Individual Needs-Intake Version (GAIN I) instrument, a reliable and valid comprehensive biopsychosocial measure for which the core scales have excellent internal consistency, good agreement with blind psychiatric diagnoses (Jasiukaitis and Shane, 2001) and Timeline Followback (Dennis et al., 2004), good concordance with urine tests (Buchan et al., 2002), and the ability to differentiate among adolescents treated in various levels of care (Dennis et al., 1999). The GAIN contains items consistent with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), criteria for all substance-use disorders and many common Axis I mental health diagnoses (i.e., attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, major depression, generalized anxiety), as well as more than 100 scales and indices for informing complex level-of-care placements when used in concert with commonly used patient-placement schemes (Mee-Lee et al., 2001). GAIN interviewers achieved certification, and monthly data editing was performed by the GAIN Coordinating Center to help sites resolve logical inconsistencies in the data.

Age cohort.

Adolescents younger than age 18 were coded 0 and emerging adults ages 18–25 were coded 1.

Reasons for quitting.

The Reasons for Quitting scale contains 26 yes/no items reflecting potential reasons why a participant wants to quit using drugs or alcohol at intake. It was originally developed for adults (McBride et al., 1994) and was adapted by Godley et al. (2001) for use with adolescents. In addition to the total Reasons for Quitting scale, two subscales measure pressure from family and friends (the Interpersonal Motivation Scale) and varied reasons pertaining to personal health and other consequences (the Personal Motivation Scale). Godley et al. (2001) found that the Interpersonal Motivation Scale (5 items; α = .74) and Personal Motivation Scale (18 items; α = .93) were internally consistent, exhibited moderately positive correlations with other motivation scales, and predicted 3-month drug-use outcomes (Personal Motivation Scale) and treatment completion (Interpersonal Motivation Scale). We replicated the Godley et al. (2001) factor solution (not presented but available on request from the first author) and also found evidence for high reliability for the personal motivation (Personal Motivation Scale, α = .93) and interpersonal motivation (Interpersonal Motivation Scale, α = .75) scales.

Mediators.

Participants were asked who they lived with during the past 12 months, and responses were coded (0 = no, 1 = yes) if they mentioned living with their parents. Participants were asked the number of days (range: 0-90) they had gotten in trouble with their family in the past 90 days.

Data analysis.

Few data were missing for the Reasons for Quitting items (mean percentage missing = 1.48) and scales (mean percentage missing = 5.9; range: 4.4–7.0).

Propensity score weighting was used to create comparison groups of equal size while controlling for differences between age cohorts on select variables (Rosenbaum and Rubin, 1983). The propensity score was calculated using a combination of logistic regression and discriminant function analysis to predict age group membership as a function of gender (FEM; male = 0, female = 1), minority status (White = 0, racial minority = 1); the Substance Problem Scale (past-month consequences [five items] plus substance abuse[four items] and dependence symptoms [seven items]); the Global Individual Severity Scale (range: 0–123; sum of all substance-use-disorder and mental health symptoms [depression, anxiety, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and conduct disorder criteria plus criminal behavior items]); years of substance use (current age minus first age of substance use or drunkenness); level of care (outpatient = 1 vs. residential = 0); the controlled environment index (proportion of days [of past 90 days] spent living in controlled environments, range: 0–1); the environmental risk index (peer, family, and coworker drug use and antisocial behavior, range: 0–84); the number of distinct substance-use-disorder diagnoses; the number of days of substance misuse treatment received in the 90 days before baseline assessment (range: 0–90); and whether the participant reports that they have quit using at treatment intake (0 = no, 1 = yes). We selected these scales and variables on the basis of previous findings in the literature, significant differences between age groups, and their significant associations with the Reasons for Quitting scales. Table 1 shows correlations between independent, dependent, and propensity score weighting variables before weighting (n = 5,797).

Table 1.

Correlations between independent, dependent, and matching variables in unweighted sample (n = 5,797)

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. | 14. | 15. | 16. | 17. | |

| 1. Age cohort | — | ||||||||||||||||

| 2. Gender | −.06 | — | |||||||||||||||

| 3. Minority status | .00 | −.06 | — | ||||||||||||||

| 4. Lives with parents | −.16 | .00 | −.15 | — | |||||||||||||

| 5. Trouble with family | −.12 | .13 | −.03 | .06 | — | ||||||||||||

| 6. Years of use | .28 | −.11 | .12 | −.15 | −.02 | — | |||||||||||

| 7. In outpatient treatment | −.08 | .04 | −.23 | .16 | .01 | −.19 | — | ||||||||||

| 8. Days in treatment | .04 | .01 | .06 | −.05 | −.05 | .15 | −.19 | — | |||||||||

| 9. Has quit using | −.03 | −.04 | .00 | −.12 | −.12 | −.09 | −.08 | .08 | — | ||||||||

| 10.Substance Problem Scale | −.03 | .05 | .01 | .04 | .26 | .10 | −.04 | −.07 | −.35 | — | |||||||

| 11 .Environmental Risk Scale | −.04 | .03 | .07 | −.01 | .23 | .18 | −.14 | .01 | −.23 | .30 | — | ||||||

| 12.Controlled Environment Index | .14 | −.03 | .21 | −.22 | −.14 | .22 | −.40 | .39 | .17 | −.20 | .01 | — | |||||

| 13.Number of SUD diagnoses | .09 | .07 | .02 | −.10 | .04 | .27 | −.28 | .20 | .06 | .13 | .13 | .31 | — | ||||

| 14.Global Individual Severity Score | −.06 | .19 | .07 | .02 | .36 | .23 | −.13 | .14 | −.18 | .42 | .43 | .09 | .35 | — | |||

| 15.Interpersonal Motivation Scale | −.04 | −.04 | .08 | −.02 | .03 | −.03 | −.09 | .02 | .12 | .11 | −.02 | .03 | .11 | .13 | — | ||

| 16.Personal Motivation Scale | .04 | .02 | .17 | −.08 | −.05 | .07 | −.21 | .09 | .15 | .07 | −.02 | .18 | .21 | .17 | .60 | — | |

| 17.Reasons for Quitting Scale | .02 | −.00 | .17 | −.07 | −.04 | .06 | −.20 | .09 | .16 | .08 | −.02 | .17 | .20 | .17 | .75 | .97 | — |

Notes: SUD = substance-use disorder. Correlations in bold are significant at p < .01, and italicized correlations significant at p < .05.

The weight was then calculated as the propensity score times the sample size of the emerging adult group divided by the sum of the adolescent weights. Adding the latter (a constant) does not affect the match but creates equal sample sizes per group and creates a slightly more conservative test. The final weighted groups were approximately the same size (627 adolescents, 642 emerging adults). After weighting there were no longer differences between age groups on the majority of matching variables, and effect sizes for remaining differences were small. Table 2 summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics of the weighted analysis sample.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of weighted analysis sample

| Variable | Adolescents (n = 627) % or M (SD) | EAs (n = 642) % or M (SD) | Total (n = 1,269) % or M (SD) |

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 72.9% | 77.3% | 75.1% |

| Female | 27.1% | 22.7% | 24.9% |

| Age*** | 16.3 (0.82) | 18.7 (1.3) | 17.5 (1.1) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 52.4% | 54.5% | 53.5% |

| African American | 10.9% | 12.8% | 11.8% |

| Hispanic | 16.8% | 17.8% | 17.1% |

| Native American | 2.9% | 0.6% | 1.7% |

| Asian | 0.8% | 1.4% | 1.1% |

| Biracial | 14.7% | 11.8% | 13.2% |

| Highest school grade completed*** | 9.6 (1.2) | 11.1 (1.3) | 10.4 (1.2) |

| Living with parents*** | 85.0% | 69.2% | 77.0% |

| Alcohol, drug use, and mental health | |||

| Alcohol dependence | 15.4% | 19.3% | 17.4% |

| Alcohol abuse*** | 50.4% | 57.8% | 54.2% |

| Diagnostic orphans | 8.3% | 7.3% | 7.8% |

| Weekly alcohol use | 23.9% | 28.3% | 26.1% |

| Weekly heavy episodic drinking | 14.2% | 17.9% | 16.0% |

| No. SUD diagnoses | 1.4 (1.14) | 1.7 (1.32) | 1.4 (1.2) |

| Substance Problem Scale | 3.2 (3.7) | 2.95 (3.9) | 3.08 (3.8) |

| Years of substance use*** | 3.18 (2.04) | 4.91 (2.81) | 4.05 (2.6) |

| Has quit using | 67.4% | 62.0% | 64.6% |

| Global Individual Severity Score*** | 35.2 (21.7) | 30.1 (22.1) | 32.6 (22.1) |

| Environmental/process variables | |||

| Controlled Environment Index | 0.15 (0.29) | 0.22 (0.38) | 0.19 (0.35) |

| In outpatient treatment* | 86% | 80% | 83.5% |

| Days of SUD treatment | 3.0 (12.8) | 4.7 (17.6) | 4.3 (16.1) |

| Environmental Risk Scale*** | 38.6 (9.3) | 36.4 (9.9) | 37.5 (9.7) |

| Days in trouble with family*** | 13.9 (23.3) | 6.9 (17.3) | 10.4 (20.8) |

| Reasons for quitting | |||

| Total scale | 12.5 (7.3) | 13.0 (7.5) | 13.0 (7.4) |

| Personal motivation | 8.9 (5.8) | 9.5 (5.9) | 9.5 (5.8) |

| Interpersonal motivation* | 2.46 (1.75) | 2.21 (1.81) | 2.37 (1.78) |

Notes: EAs = emerging adults; SUD = substance-use disorder.

p <.05;

p < .001.

Weighted chi-square tests were used to determine associations between age cohort and each separate reason for quitting. Similarly, weighted linear regressions were used to predict the Reasons for Quitting and subscale scores, with mediators added in the second block.

Results

Individual reasons for quitting

The most highly endorsed items (see Table 3) by both age groups were “to show yourself you can quit if you really want to” (74.1% of emerging adults and 79.0% of adolescents) and “to save the money you spend on alcohol and drugs” (70.4% of emerging adults and 65.3% of adolescents). It is also notable that about one half of adolescents and emerging adults endorsed having current substance-related health consequences (49.7% of emerging adults and 51.5% of adolescents) and are also worried about future health consequences, which runs contrary to conventional wisdom that these populations have not used substances long enough to experience such effects. Significant differences existed between age cohorts on most Interpersonal Motivation Scale items, as well as for one legal item (drug-testing policy) and one self-control item (show yourself you can quit).

Table 3.

Item endorsement among emerging adults (n = 642) and adolescents (n = 5,155)

| You want to quit using at this time because/so that you(r)/to… | EAs | Adolescents |

| Will be able to think more clearly (PMS) | 66.1% | 64.2% |

| Will like yourself better if you quit (PMS) | 54.6% | 53.2% |

| Memory will improve (PMS) | 60.2% | 62.3% |

| Can get more things done during the day (PMS) | 58.6% | 57.9% |

| Want to have more energy (PMS) | 58.5% | 56.2% |

| Are concerned that using alcohol or drugs will shorten your life (PMS) | 53.9% | 54.1% |

| Hair and clothes won't smell (PMS) | 36.8% | 38.5% |

| Can feel in control of your life (PMS) | 62.1% | 61.6% |

| Have noticed that alcohol or drug use is hurting your health (PMS) | 49.7% | 51.5% |

| Won't burn holes in clothes or furniture (PMS) | 29.9% | 29.8% |

| Are concerned that you will have health problems if you don't quit (PMS) | 58.3% | 58.0% |

| Alcohol or drug use does not fit in with your image (PMS) | 42.9% | 39.0% |

| Prove yourself that you are not addicted (PMS) | 61.8% | 66.1% |

| Alcohol or drug use is becoming less “cool” or socially acceptable (PMS) | 22.0% | 21.1% |

| Won't have to leave social functions or other people's houses to drink or use (PMS) | 31.9% | 32.7% |

| Have known people with health problems caused by alcohol or drug use (PMS) | 57.0% | 56.1% |

| Show yourself you can quit if you really want to (PMS) | 74.1% | 79.0%* |

| Want to save the money that you spend on alcohol or drug use (PMS) | 70.4% | 65.3% |

| Will get a lot of praise from people you are close to (IMS) | 45.8% | 51.5%* |

| People you are close to will be upset if you don't quit (IMS) | 51.3% | 60.8%*** |

| Don't want to embarrass your family (IMS) | 50.1% | 53.9% |

| Close ones will stop nagging you if you quit (IMS) | 45.3% | 53.9%** |

| Someone close to you told you to quit or else (IMS) | 29.2% | 35.1%* |

| Will receive a special gift if you quit (RFQ) | 11.2% | 12.7% |

| There is a drug-testing policy in detention, probation, parole, or school (RFQ) | 42.4% | 52.2%*** |

| Legal problems related to your alcohol or drug use (RFQ) | 53.0% | 53.5% |

Notes: EAs = emerging adults; PMS = Personal Motivation Scale; IMS = Interpersonal Motivation Scale; RFQ = Reasons for Quitting, only in Total RFQ scale.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Predicting Reasons for Quitting scale scores

Age cohort was not a significant predictor of total reasons for quitting, β = −.369, ΔF(1, 1268) = 0.787, p = .375, R2 = .16, or personal motivation, β = .075, ΔF(1, 1267) = 0.052, p = .819, R2 = .006. Age cohort did, however, significantly predict interpersonal motivation scores, that is, Interpersonal Motivation Scale: β = −.345, 95% CI [−.543, −.148], R2 = .01, ΔF(1, 1246) = 11.8, p < .001, after controlling for baseline differences via propensity weighting. Further, the effect size for observed mean differences between adolescents and emerging adults (Cohen's d = 0.20) represented a small effect, which is important given that large sample sizes can detect statistically significant but meaningless effects.

Mediation analyses

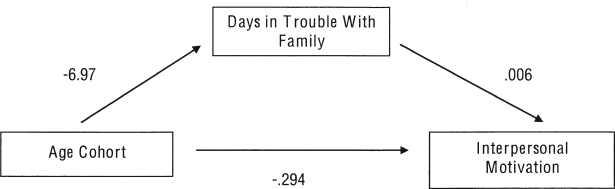

We found that when potential mediators were entered in the second block, ΔF(1, 1229) = 3.076, p < .05, R2 = .014, age cohort remained significant, but the magnitude of its association with the Interpersonal Motivation Scale decreased (β = −.294). Furthermore, days of being in trouble with one's family was a significant, albeit weak predictor of Interpersonal Motivation Scale scores (β = .006, 95% CI [.001, .011], p < .05). Figure 1 depicts how days of being in trouble with one's family partially mediates the association between age and interpersonal motivation. Living at home in the past year (β = −.07, 95% CI [−.312, .172], N.S.) was not a significant predictor of interpersonal motivation. The total percentage of variance explained by this model was low (R2 = .014), resonating with recent findings on predicting treatment readiness (DiClemente et al., 2009).

Figure 1.

Days in trouble with family partially mediates association between age and interpersonal motivation. All unstandardized beta coefficients are significant at p < .05.

Discussion

This study's two main findings have implications for practice and future research. First, we found no significant differences on overall reasons for quitting between emerging adults and adolescents, and with the exception of the interpersonal motivation items, few differences existed at the item level when controlling for baseline differences between age cohorts. This runs counterintuitive to previous findings from other studies showing associations between age and treatment readiness, and we think this is likely because of the far greater variation in age in those studies (Melnick et al., 1997; Satre et al., 2003). However, adolescents and emerging adults endorsed, on average, nearly half of all forced-choice reasons for quitting that were presented to them. This finding challenges the common assumption that young people are more difficult to work with simply because of their lack of negative consequences and relative inexperience with substances. Simply put, these two age cohorts do not appear to arrive at treatment devoid of reasons for quitting. It may be highly beneficial for substance misuse counselors who treat young people to develop skills in eliciting and exploring reasons for quitting, which can help them resolve ambivalence about behavior change (Miller and Rollnick, 2002).

The second main finding of this study was that emerging adults had less interpersonal motivation to quit using substances than adolescents, and this was partially explained by the extent to which they were getting into trouble with their family. Although causal attributions cannot be made here, this is consistent with developmental theory about how the greater independence of emerging adults may contribute to increasing substance use. It may also be that this variable is a marker of permissive parental attitudes toward use, which have been shown to predict risky drinking among college students (Abar et al., 2009; Wood et al., 2004).

It is hard to say what other influences in these emerging adults' and adolescents' social networks may have accounted for interpersonal motivation to quit, because both adolescents (60.7%) and emerging adults (59.3%) reported that at least a few of their peers were weekly drinkers and detailed social-network instruments were not used. It may also be, however, that nonusing social-network members may not place pressure on these emerging adults, because alcohol and drug use is so common during emerging adulthood. Finally, emerging adults, who are arguably more independent and mobile than adolescents, may be more likely to disregard concerns presented by friends and family about their use. Thus, emerging adults simply may not perceive such pressure as sufficient grounds for quitting or may select different living arrangements or social networks whose members have substance-use patterns similar to theirs.

Regardless of the precise explanation, these findings imply that particular attention should be paid to the social networks of emerging adults presenting for publicly funded treatments. Additional research should clarify with greater precision how these networks are constructed, and what indigenous supports (e.g., nondrinking peers, supportive family members, or concerned others) may be leveraged as part of the treatment process. Such efforts may shed light on adapting existing treatments that use family members or concerned significant others that are effective in encouraging treatment engagement and compliance for older adults (Fernandez et al., 2006; McCrady, 2004). Family-based treatments for emerging adults that include parents have only begun to be studied, and findings are encouraging (Turrisi et al., 2001, 2009). However, these studies have been conducted with alcohol-using college students and may not be generalizable to public-sector alcohol-treatment settings where poly drug use is common (see Table 2). In addition, a high percentage of parents randomized to two family-based conditions (i.e., 37% and 40%) in Turrissi et al.'s (2009) study never participated in treatment. Thus, adaptations of family-based treatments that leverage other social supports may also be worth investigating. In fact, some researchers have made specific mention of the need for studies on whether peers and other non-family members can be integrated into treatment processes (Andrews et al., 2002; Longabaugh, 2003; McCrady, 2004). To our knowledge, only one efficacy study has used a treatment where peers attend as collaterals, finding that both identified clients and heavy drinking peers reduced their drinking at follow-up (O'Leary-Tevyaw et al., 2007). In short, additional research is needed on how to leverage social supports for emerging adults, especially for those who are not in 4-year college settings.

These findings should be interpreted in light of the study's limitations. First, we did not ask participants about how social-network members view their substance use (Zywiak et al., 2002), nor did we gather in-depth information on the quality of their social relationships (Borsari and Carey, 2006). Such information would permit testing on how social-network composition may affect interpersonal motivations for quitting. Second, we note that these findings are from a clinical sample and may not generalize to non-treatment-seeking populations. Third, the age distribution (i.e., nage 18 = 436, nage 19 = 96, nage 20–25 = 110) in our emerging adult subgroup was skewed toward younger emerging adults, which somewhat limits generalizability to older emerging adults. Finally, although the total Reasons for Quitting scale has good predictive validity for both adolescents and adults in other studies, we did not investigate whether the Interpersonal Motivation scale subscale predicts clinical outcomes. Thus, we cannot estimate whether interpersonal motivation or the potential interactions between interpersonal motivation and types of treatments provided (i.e., social support intensive vs. individual only) predict outcomes for young adults.

Despite these limitations, our study contributes by providing data on common reasons for quitting among these populations and finding support for one of the theoretical tenets of emerging adulthood: that lower interpersonal motivation to quit using substances is partially accounted for by less familial social control. We advocate for future research on the social networks of non-college clinical samples of emerging adults as part of broader efforts to improve substance misuse treatments for this understudied population.

Footnotes

The development of this article was supported by a National Institutes of Health loan repayment contract awarded to Douglas C. Smith. An earlier version of this analysis was presented at a poster session on June 20, 2009, at the annual conference of the Research Society on Alcoholism, San Diego, CA, June 20–24,2009.

References

- Abar C, Abar B, Turrisi R. The impact of parental modeling and permissibility on alcohol use and experienced negative drinking consequences in college. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:542–547. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed., text rev. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JA, Tildesley E, Hops H, Li F. The influence of peers on young adult substance use. Health Psychology. 2002;21:349–357. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.4.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55:469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. The developmental context of substance use in emerging adulthood. Journal of Drug Issues. 2005;35:235–254. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard KA, Morgenstern J, Morgan TJ, Labouvie E, Bux DA. Motivational subtypes and continuous measures of readiness for change: Concurrent and predictive validity. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17:56–65. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.17.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Okuda M, Wright C, Hasin DS, Grant BF, Liu S, Olfson M. Mental health of college students and their non-college-attending peers: Results from the national epidemiologic study on alcohol and related conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2008;65:1429–1437. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.12.1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey K. How the quality of peer relationships influences college alcohol use. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2006;25:361–370. doi: 10.1080/09595230600741339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broome KM, Joe GW, Simpson D. Engagement models for adolescents in DATOS-A. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2001;16:608–623. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, McGue M, Maggs J, Schulenberg J, Hingson R, Swartzwelder S, Martin C, Chung T, Tapert SF, Sher K, Winters KC, Lowman C, Murphy S. A developmental perspectiveon alcohol and youths 16 to 20 years of age. Pediatrics. 2008;121(Suppl.4):S290–S310. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2243D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchan BJ, Dennis ML, Tims FM, Diamond GS. Can-nabis use: Consistency and validity of self-report, on-site urine testing and laboratory testing. Addiction. 2002;97:98–108. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.97.s01.1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cady ME, Winters KC, Jordan DA, Solberg KB, Stinchfield RD. Motivation to change as a predictor of treatment outcome for adolescent substance abusers. Journal of Child & AdoIescent Substance Abuse. 1996;5:73–91. [Google Scholar]

- Callaghan RC, Hathaway A, Cunningham JA, Vettese LC, Wyatt S, Taylor L. Does stage-of-change predict dropout in a culturally diverse sample of adolescents admitted to inpatient substance-abuse treatment? A test of the transtheoretical model. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30:1834–1847. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaghan RC, Taylor L, Moore BA, Jungerman FS, De Biaze Vilela FA, Budney AJ. Recovery and URICA stage-of-change scores in three marijuana treatment studies. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;35:419–426. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbonari JP, DiClemente CC. Using transtheoretical model profiles to differentiate levels of alcohol abstinence success. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:810–817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Purnine DM, Maisto SA, Carey MP. Assessing readiness to change substance abuse: A critical review of instruments. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1999;6:245–266. [Google Scholar]

- De Goede IHA, Branje SJT, Meeus WHJ. Developmental changes in adolescents' perceptions of relationships with their parents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:75–88. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9286-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLeon G, Melnick G, Kressel D, Jainchill N. Circumstances, motivation, readiness, and suitability (the CMRS scales): Predicting retention in therapeutic community treatment. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1994;29:495–515. doi: 10.3109/00952999409109186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delucchi KL, Matzger H, Weisner C. Alcohol in emerging adulthood: 7-year study of problem and dependent drinkers. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;3:134–142. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Funk R, Godley SH, Godley MD, Waldron H. Cross-validation of the alcohol and cannabis use measures in the global appraisal of individual needs (GAIN) and timeline followback (TLFB; form 90) among adolescents in substance abuse treatment. Addiction. 2004;99:120–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Scott CK, Godley MD, Funk R. Comparisons of adolescents and adults by ASAM profile using GAIN data from the drug outcome monitoring study (DOMS): Preliminary data tables. Bloomington, IL: Chestnut Health Systems; 1999. Retrieved from http://www.chestnut.org/LI/Posters/asamprof.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Titus JC, White MK, Unsicker JI, Hodgkins D. Global appraisal of individual needs (GAIN) Administration guide for the GAIN and related measures. Bloomington, IL: Chestnut Health Systems; 2002. Retrieved from http://www.chestnut.org/LI/gain/index.html#Administration%20Manual. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, White MK, Ives ML. Individual characteristics and needs associated with substance misuse of adolescents and young adults in addiction treatment. In: Leukefeld C, Gullotta T, Stanton Tindall M, editors. Handbook on adolescent substance abuse prevention and treatment: Evidence-based practice. New London, CT: Child and Family Agency Press; 2009. pp. 45–72. [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente CC, Doyle SR, Donovan D. Predicting treatment seekers' readiness to change their drinking behavior in the COMBINE study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2009;33:879–892. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00905.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey L, Rosengren DB, Donovan DM. Sources of motivation for abstinence: A replication analysis of the reasons for quitting questionnaire. Addictive Behaviors. 2001;26:79–89. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00090-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Identity and the life cycle. New York: W. W. Norton and Company; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez AC, Begley EA, Marlatt GA. Family and peer interventions for adults: Past approaches and future directions. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20:207–213. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. Age and sex differences in perceptions of networks of personal relationships. Child Development. 1992;63:103–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb03599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godley SH, Funk R, Dennis ML. There relationship of treatment motivation with treatment retention and outcomes among adolescents in treatment for marijuana abuse and dependence. 2001. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF. Barriers to alcoholism treatment: Reasons for not seeking treatment in a general population sample. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:365–371. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handelsman L, Stein JA, Grella CE. Contrasting predictors of readiness for substance abuse treatment in adults and adolescents: A latent variable analysis of DATOS and DATOS-A participants. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;80:63–81. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson MJ, Saules KK, Galen LW. The predictive validity of the University of Rhode Island change assessment questionnaire in a heroin-addicted polysubstance abuse sample. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:106–112. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.2.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiller ML, Knight K, Leukefeld C, Simpson DD. Motivation as a predictor of therapeutic engagement in mandated residential substance abuse treatment. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2002;29:56–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ilgen MA, McKellar J, Moos R, Finney JW. Therapeutic alliance and the relationship between motivation and treatment outcomes in patients with alcohol use disorder. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;31:157–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasiukaitis P, Shane P. Discriminant analysis with GAIN-I psychological indices reproduces staff psychiatric diagnoses in an adolescent substance abusing sample; Presented at the Persistent Effects of Treatment Study of Adolescents Analytic Cross-Site Meeting; Washington, D.C. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2006. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Drug Abuse; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Longabaugh R. Involvement of support networks in treatment. In: Galanter M, editor. Recent developments in alcoholism: Vol. 16. Research on alcoholism treatment. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum; 2003. pp. 133–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride CM, Curry SJ, Stephens RS, Wells EA, Roffman RA, Hawkins JD. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation for change in cigarette smokers, marijuana smokers, and cocaine users. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1994;8:243–250. [Google Scholar]

- McCrady BS. To have but one true friend: Implications for practice of research on alcohol use disorders and social networks. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:113–121. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.2.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mee-Lee D, Gartner L, Miller MM, Shulman G, Wilford B. Patient placement criteria, second edition-revised (ASAM PPC-2R) Annapolis Junction, MD: American Society of Addiction Medicine; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Melnick G, De Leon G, Hawke J, Jainchill N, Kressel D. Motivation and readiness for therapeutic community treatment among adolescents and adult substance abusers. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1997;23:485–506. doi: 10.3109/00952999709016891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TR, Levy DT, Spicer RS, Taylor DM. Societal costs of underage drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:519–528. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Villanueva M, Tonigan JS, Cuzmar I. Are special treatments needed for special populations? Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2007;25(4):63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson LJ, Barry CM. Distinguishing features of emerging adulthood: The role of self-classification as an adult. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2005;20:242–262. [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary-Tevyaw T, Borsari B, Colby SM, Monti PM. Peer enhancement of a brief motivational intervention with mandated college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21:114–119. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.1.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park MJ, Mulye TP, Adams SH, Brindis CD, Irwin CE., Jr The health status of young adults in the United States. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39:305–317. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock NK, Martin CS. Diagnostic orphans: Adolescents with alcohol symptoms who do not qualify for DSM-IV abuse or dependence diagnoses. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:897–901. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.6.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC. In search of how people change: Applications to addictive behaviors. American Psychologist. 1992;47:1102–1114. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.47.9.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70:41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Rueter MA, Holm KE, Burzette R, Kim KJ, Conger RD. Mental health of rural young adults: Prevalence of psychiatric disorders, comorbidity, and service utilization. Community Mental Health Journal. 2007;43:229–249. doi: 10.1007/s10597-007-9082-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satre DD, Mertens J, Arean PA, Weisner C. Contrasting outcomes of older versus middle-aged and younger adult chemical dependency patients in a managed care program. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:520–530. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R, Easton C, Kemp K. Substance abuse treatment characteristics of probation-referred young adults in a community-based outpatient program. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2003;29:585–597. doi: 10.1081/ada-120023460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DC, Hall JA, Arndt S, Jang M. Therapist adherence to a motivational interviewing intervention improves treatment entry for substance misusing adolescents with low problem perception. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70:101–105. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (Office of Applied Studies) The NSDUH Report: Reasons for not receiving substance abuse treatment. Rockville, MD: Author; 2003. Retrieved from http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/2k3/SAnoTX/SAnoTX.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (Office of Applied Studies) Results from the 2007 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National findings (NSDUH Series H-34, DHHS Publication No. SMA 08-4343) Rockville, MD: Author; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tetzlaff BT, Kahn JH, Godley SH, Godley MD, Diamond GS, Funk RR. Working alliance, treatment satisfaction, and patterns of post-treatment use among adolescent substance users. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:199–207. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titus JC, Godley SH, White MK. A post-treatment examination of adolescents' reasons for starting, quitting, and continuing the use of drugs and alcohol. Journal of Child and Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2007;16(2):31–49. [Google Scholar]

- Turrisi R, Jaccard J, Taki R, Dunnam H, Grimes J. Examination of the short-term efficacy of a parent intervention to reduce college student drinking tendencies. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15:366–372. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.15.4.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrisi R, Larimer ME, Mallett KA, Kilmer JR, Ray AE, Mastroleo NR, Montoya H. A randomized clinical trial evaluating a combined alcohol intervention for high-risk college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70:555–567. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Fleming CB, Kim MJ, Catalano RF, McMorris BJ. Identifying two potential mechanisms for changes in alcohol use among college-attending and non-college-attending emerging adults. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:1625–1639. doi: 10.1037/a0013855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood MD, Mitchell RE, Read JP, Brand NH. Do parents still matter? Parent and peer influences on alcohol involvement among recent high school graduates. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:19–30. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zywiak WH, Longabaugh R, Wirtz PW. Decomposing the relationships between pretreatment social network characteristics and alcohol treatment outcome. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:114–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]