Abstract

Objective:

The aim of this study was to determine if parental restriction regarding Restricted-rated movies (R movies) predicts lower rates of early-onset alcohol use.

Method:

Students from 15 northern New England middle schools were surveyed in 1999, and never-drinkers were resurveyed 13–26 months later to determine alcohol use. Drinking was determined by the question, “Have you ever had beer, wine, or other drink with alcohol that your parents didn't know about?” R-movie restriction was assessed by the question, “How often do your parents allow you to watch movies that are rated R?”

Results:

The sample included 2,406 baseline never-drinkers who were surveyed at follow-up, of whom 14.8% had initiated alcohol use. At baseline, 20% reported never being allowed to watch R movies, and 21% reported being allowed all the time. Adolescents allowed to watch R-rated movies had higher rates of alcohol initiation (2.9% initiation among never allowed, 12.5% once in a while, 18.8% sometimes, and 24.4% all the time). Controlling for sociodemographics, personality characteristics, and authoritative parenting style, the adjusted odds ratios for initiating alcohol use were 3.0 (95% CI [1.7, 5.1]) for those once in a while allowed, 3.3 [1.9, 5.6] for those sometimes allowed, and 3.5 [2.0, 6.0] for those always allowed to watch R-rated movies. Alcohol initiation was more likely if R-rated movie restriction relaxed over time; tightening of restriction had a protective effect (p < .001). A structural model was developed that modeled two latent parenting constructs: (a) authoritative parenting and (b) media parenting. Both constructs had direct inverse paths to trying alcohol and indirect paths through lower exposure to R-rated movies.

Conclusions:

After accounting for differences in authoritative parenting style, adolescents reporting lesser restrictions for R movies have higher odds of future alcohol use. The structural model suggests that media parenting operates independently from authoritative parenting and should be incorporated explicitly into parenting prevention programs.

Today's youth have unprecedented access to entertainment media (Roberts et al., 2005), and longitudinal research has linked various forms of entertainment media with aggressive behavior (Bushman and Anderson, 2001), sexual behavior (Collins et al., 2004), and tobacco use (Sargent, 2005). Indeed, the available research evidence has led the National Cancer Institute (2008) to declare a causal relation between exposure to movie smoking and youth smoking initiation. Less is known about the relation between movies and youth drinking, but movies are a type of entertainment media with many references to alcohol use, as well as frequent alcohol brand appearances, and about 30% of this exposure comes from “Restricted”-rated movies (R movies; Dal Cin et al., 2008). Early-onset alcohol use is associated with a fivefold increase in the risk of adult alcoholism (Grant and Dawson, 1997), and with increased risk of injuries, violence, homicide, suicide, and drunk driving (Gruber et al, 1996; Hingson et al, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003).

Two studies in the United States and one study in Germany support an association between exposure to movie alcohol use and drinking onset (Dal Cin et al, 2009; Hanewinkel et al, 2008; Sargent et al, 2006). In the German cohort, movie alcohol exposure was also associated with binge drinking onset, and adolescent-reported parental restrictions from viewing adult-rated (FSK 16 and FSK 18 [Freiwillige Selbst-kontrolle der Filmwirtschaft—better known as FSK or as the “voluntary self-regulation of the movie industry”]) movies were associated with reduced exposure to movie alcohol use and with lower risk for drinking (Hanewinkel et al, 2008). Although there is cross-sectional research to suggest the same result for U.S. adolescents (Dalton et al, 2002), no longitudinal research has been published. This study assesses the relation between parental R-movie restriction and risk for early-onset alcohol use, and the degree to which the effect is mediated through R-movie exposure.

Method

Study sample

Study participants included 3,577 youth who had reported never drinking from a survey of 4,655 students (Grades 5–8), conducted at 15 Northern New England middle schools. Baseline never-drinkers were followed up 13–26 months later with a telephone interview, with successful follow-up of 2,406 students. Students lost to follow-up were more likely to have parents who did not complete high school, were higher in rebelliousness, and were more likely to report poor school performance. The association between R-rated movie viewing and attrition was marginally significant (p = .06). They did not differ with respect to authoritative parenting measures or R-rated movie restriction. The study was approved by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at Dartmouth College.

Survey administration

Baseline survey.

The details and findings of the baseline survey have been previously reported (Dalton et al., 2002). In brief, students completed a confidential paper-and-pencil survey in school that was proctored by study personnel using passive parental consent procedures. The baseline survey included a phone number for future contact and questions about substance use behaviors, demographics, social influences, student attributes, and student-perceived parenting style.

Follow-up survey.

Trained telephone interviewers conducted follow-up surveys using a computer-assisted telephone interview system (Dalton et al., 1999). To protect confidentiality in the home setting, students answered questions by touch-tone entry.

Parental restriction and exposure to R movies

R-movie restriction was determined at baseline and follow-up by the question, “How often do your parents let you watch movies or videos that are rated R (never/once in a while/sometimes/all the time)? Differences in parental restriction over time were indexed by changes in the adolescents' reports of parental R-movie restrictions from baseline to follow-up. Changes were grouped into three categories: (a) more restrictive (any more restrictive category at follow-up), (b) no change (same category at both time points), or (c) more lenient (less restrictive category at follow-up).

Youths' exposure to R movies was also measured, using previously validated methods (Sargent et al., 2008). The validation studies determined that adolescents are accurate in their recollection of whether they have seen a movie title and that they do not overreport. For example, only 3% typically report having seen a sham movie title. A sample of 601 popular contemporary films from the 5 years preceding the baseline survey was selected according to box office success (Sargent et al., 2001). Exposure was determined by asking whether the respondent had ever seen each of a unique set of 23 R-rated film titles that was randomly selected from the larger sample.

Covariates

A number of covariates were also measured. We chose covariates that we thought might confound the relation between R-rated movie restriction and alcohol use but that were not considered part of the causal mediation pathway. Covariates included sociodemographics (gender, school, age, parental education), social influence factors (peer drinking at follow-up), and personal characteristics (rebelliousness, sensation seeking, self-esteem, school performance). We included personality characteristics, such as sensation seeking, because we thought it likely that high sensation-seeking adolescents might seek out R-rated movies and report different restrictions in this area. Authoritative parenting style (Baumrind, 1991) was assessed using a subsample of items developed by Jackson et al. (1998), including domains of maternal responsiveness (e.g., “She makes me feel better when I'm upset,” “She listens to what I have to say”) and demandingness (e.g., “She has rules that I must follow,” “She knows where I am after school”). We included the authoritative parenting measures because prior analyses had indicated to us that these measures are largely independent from media parenting variables in predicting media exposure (Sargent et al., 2003). Items and reliabilities for personality and parenting scales have been published, except one item about liking alcohol or beer was removed from the sensation-seeking index (Sargent et al., 2004). These indices were split at their medians for clarity in the crude analysis of drinking onset but were entered as continuous variables in the multivariate and structural equation modeling analyses.

Outcome assessment

Alcohol drinking was determined by asking: “Have you ever drunk beer, wine, or other drink with alcohol that your parents did not know about?” (yes or no). This phrasing was used to exclude parent-condoned sips of alcohol use at family and religious occasions, a common occurrence that is not as strongly related to risk factors for adverse outcomes (Donovan and Molina, 2008). Only baseline never-drinkers are included in this study. A student who reported drinking alcohol at follow-up was classified as having initiated drinking during the observation period.

Analyses

Chi-square tests compared differences in proportions. Multivariate logistic regressions were conducted to determine the independent association of parental R-movie restrictions at baseline with incident drinking and change in R-movie restriction (between baseline and follow-up) with incident drinking. An overdispersion parameter was used to account for possible clustering by schools.

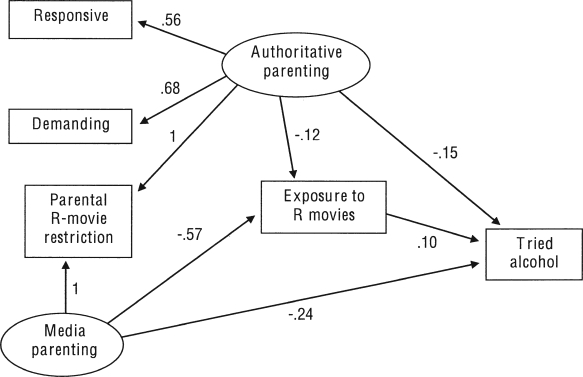

The previously described analyses required the three related parenting constructs (maternal responsiveness, maternal demandingness, and parental R-movie restriction) to compete in a multivariate model. Additionally, it did not assess the degree to which the effect of media restriction on alcohol use is mediated through lower media exposure. To address these issues, a longitudinal structural equation model was fit, as shown in Figure 1, in which authoritative parenting style was modeled as a latent variable representing the shared variance in the baseline measures of R-movie restriction, maternal demandingness, and maternal responsiveness. A latent media parenting variable modeled the unique variance in R-movie restriction that was not shared with latent authoritative parenting style. Both latent parenting constructs were used to predict R-movie exposure and alcohol-use onset. The structural part of the model involving alcohol initiation was fit as a logistic regression with estimates on the log odds scale. All other regression relations in the model were based on the standard normal regression model, including all covariates listed previously. The model was estimated using numerical integration in the MPlus 5.2 software package (Muthén and Muthén, 1998–2007).

Figure 1.

Structural equation model for the association parental restriction of R-rated movies and authoritative parenting with alcohol onset, study location northern New England, 1999–2002.

Results

Exposure to R movies, covariates, and their relations with alcohol onset are described in Table 1. The final sample of 2,406 students was primarily (94.9%) White, gender was equally represented, and the vast majority (84.1%) of students reported that both parents had completed high school. Just 20.1% of fifth through eighth graders were never allowed by their parents to watch R movies at baseline, 30.6% were allowed once in a while, 28.3% sometimes, and 21.0% always. In terms of other social influence risk factors, just 5.7% reported having ever smoked a cigarette at baseline, and almost half reported peer drinking at follow-up.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study sample (n = 2,406)

| Baseline predictor variable | n (%) | Tried drinking incidence (assessed at T2) % | p |

| Grade | <.001 | ||

| Fifth grade | 249 (10.3%) | 3.6 | |

| Sixth grade | 702 (29.2%) | 9.5 | |

| Seventh grade | 779 (32.4%) | 13.4 | |

| Eighth grade | 676(28.1%) | 26.2 | |

| Gender | .06 | ||

| Male | 1,111 (46.2%) | 13.6 | |

| Female | 1,295 (53.8%) | 15.9 | |

| Parent education | ns | ||

| Neither or one completed high school | 383 (15.9%) | 15.7 | |

| Both completed high school | 2,023 (84.1%) | 14.7 | |

| School performance | <.001 | ||

| Excellent | 1,071 (44.5%) | 11.8 | |

| Good | 924 (38.4%) | 15.7 | |

| Average/below average | 411 (17.1%) | 20.9 | |

| Self-esteem | <.001 | ||

| Below median | 1,112(46.2%) | 17.9 | |

| Above median | 1,294(53.8%) | 12.2 | |

| Maternal responsiveness | <.001 | ||

| Below median | 1,259(52.3%) | 17.7 | |

| Above median | 1,147(47.7%) | 11.7 | |

| Maternal demandingness | ns | ||

| Below median | 1,156(48.0%) | 15.6 | |

| Above median | 1,250(52.0%) | 14.2 | |

| Rebelliousness | <.001 | ||

| Below median | 1,620(67.3%) | 11.8 | |

| Above median | 786 (32.7%) | 21.1 | |

| Sensation seeking | <.001 | ||

| Below median | 1,471 (61.1%) | 11.1 | |

| Above median | 935 (38.9%) | 20.6 | |

| Ever smoked a cigarette | <.001 | ||

| No | 2,268 (94.3%) | 13.1 | |

| Yes | 138 (5.7%) | 42.8 | |

| Peer drinking at follow-up | <.001 | ||

| No | 1,259 (52.3%) | 3.0 | |

| Yes | 1,147 (47.7%) | 27.8 | |

| R-movie restriction at baseline | <.001 | ||

| Never allowed | 484(20.1%) | 2.9 | |

| Allowed sometimes | 737 (30.6%) | 12.5 | |

| Allowed once in a while | 680 (28.3%) | 18.8 | |

| Allowed all the time | 505 (21.0%) | 24.4 |

Notes: Study location, northern New England; date, 1999–2002. T2 = Time 2; ns = nonsignificant.

Parental R-movie restrictions and exposure to R movies

Stricter restrictions at baseline were associated with less exposure to R movies (p < .001). Youth who reported that they were “never” allowed to view R movies saw only 5.1% of R movies in their sample (95% CI [4.4, 5.9]), the “once-in-a-while” group saw 15.5% [14.6, 16.5], the “sometimes” group saw 23.4% [22.4, 24.4], and the “all-the-time” group saw 30% [28.8, 31.2], suggesting the parental restrictions were associated with lower exposure.

Predictors of drinking onset

Overall, 14.8% of students initiated alcohol use without parental knowledge over the survey interval (Table 1). All the covariates except gender, maternal demandingness, and parent education were associated with drinking onset at the bivariate level. Parental R-movie restriction at baseline was associated with alcohol onset in a graded fashion. Those who reported friend drinking were far more likely initiate drinking by follow-up: Only 2.9% of students who reported that no peers drank at follow-up initiated drinking alcohol, whereas 27.8% of students who reported that peers drank initiated drinking alcohol.

After controlling for baseline covariates and friend drinking at follow-up (Table 2), parental R-movie restriction remained a predictor of trying drinking without parental knowledge (adjusted odds ratio: 3.0–3.5 for all less restrictive categories than none). Other variables associated with increased risk of trying drinking included grade in school, gender, ever tried smoking, and peer drinking at follow-up (Table 2). The authoritative parenting items did not retain a multivariate association with alcohol onset.

Table 2.

Multivariate model, predictors of alcohol onset

| Baseline predictor variable* | Adjusted odds ratio [95% CI] |

| Parental restriction of R-movies at baseline | |

| Never allowed | Reference |

| Allowed once in a while | 3.0 [1.7, 5.1] |

| Allowed sometimes | 3.3 [1.9,5.6] |

| Allowed all the time | 3.5 [2.0, 6.0] |

| Grade | |

| Fifth grade | Reference |

| Sixth grade | 1.9 [1.0,3.7] |

| Seventh grade | 1.8 [0.9,3.5] |

| Eighth grade | 2.6 [1.3, 5.1] |

| Gender | |

| Male | Reference |

| Female | 1.3 [1.1, 1.7] |

| Parent education | |

| Neither or one completed high school | Reference |

| Both completed high school | 1.1 [0.9, 1.5] |

| School performance | |

| Excellent | Reference |

| Good | 1.0 [0.8, 1.3] |

| Average/below average | 1.0 [0.8, 1.4] |

| Maternal responsiveness | 0.98 [0.94, 1.02] |

| Maternal demandingness | 1.01 [0.97, 1.1] |

| Self-esteem | 1.01 [0.98, 1.03] |

| Rebelliousness | 1.04 [0.99, 1.1] |

| Sensation seeking | 1.03 [0.99, 1.1] |

| Ever smoked a cigarette | |

| No | Reference |

| Yes | 1.7 [1.3, 2.3] |

| Peer drinking at follow-up | |

| No | Reference |

| Yes | 5.7 [4.1, 8.0] |

Notes: Study location, northern New England; date, 1999–2002.

Self-esteem (scale range: 0–24), rebelliousness (0–21), sensation seeking (0–15), maternal responsiveness (0–12), and demandingness (0–12) were all entered as continuous variables; therefore, the odds ratio represents the increased odds for a 1-point increase in each scale.

Changes in R-movie restrictions and trying drinking

Nearly half (45%) of the youth surveyed reported no change in R-movie restrictions between the baseline and follow-up surveys. However, 33% reported greater leniency, and 22% reported greater restriction at follow-up. The association of alcohol initiation and change in status of parental R-movie restriction is examined, with the adolescents reporting never being allowed to watch R movies at both baseline and follow-up as the comparison group. As shown in Table 3, for all baseline categories of the restriction, change in parental restriction over time was associated with alcohol use, with more leniency resulting in relatively higher rates of trying alcohol and more restriction resulting rates lower than those in both the no-change and the more-lenient categories. For example, among adolescents reporting that they were allowed to watch R movies once in a while at baseline, 6.9% of those reporting a more restrictive category at follow-up tried drinking, compared with 10% and 16% for no-change and more-lenient categories, respectively, risk trends that were maintained after covariate adjustment.

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of alcohol onset modeling changes in parental R-rated movie restriction over time

| Parental R-rated movie restriction |

Alcohol onset, baseline to T2 |

||

| Baseline value | Change from baseline to T2 (n) | % Trying alcohol | Adjusted odds ratio* [95% CI] |

| Never allowed | No change (229) | 1.3% | Reference |

| More lenient (255) | 4.3% | 2.1 [0.7, 6.9] | |

| Allowed once in a while | More restrictive (58) | 6.9% | 4.5 [1.1, 17.8] |

| No change (318) | 10.0% | 5.1 [1.7, 15.3] | |

| More lenient (361) | 16.0% | 5.3 [1.8, 15.6] | |

| Allowed sometimes | More restrictive (152) | 5.9% | 2.5 [0.7, 8.2] |

| No change (345) | 17.0% | 5.6 [1.9, 16.3] | |

| More lenient (183) | 32.0% | 7.9 [2.7, 23.3] | |

| Allowed all the time | More restrictive (185) | 12.0% | 3.8 [1.3, 11.8] |

| No change (320) | 31.0% | 7.3 [2.5, 21.3] | |

Notes: Study location, northern New England; date, 1999–2002. T2 = Time 2.

Controls for gender, grade in school, parent education, school performance, ever smoking, self-esteem, rebelliousness, sensation seeking, maternal responsiveness and demandingness, and friend drinking.

Structural equation model

Standardized coefficients for key paths for the structural model are shown in Figure 1; all paths in the model controlled for the effects of other covariates included in multivariate models presented in Tables 2 and 3 and were strongly significant (all ps < .001; see Table 4 for details of the model). Both latent constructs—authoritative parenting and media parenting—affected the level of exposure to R movies, and, in turn, R-movie exposure affected the odds of alcohol initiation. These results imply that both parenting constructs indirectly affect alcohol initiation by lowering the level of R-movie exposure, and both directly affect the odds of alcohol initiation over and above their respective indirect effects through R-movie exposure.

Table 4.

Estimates, standard errors (SE), z values, and standardized estimates (std. est.) for structural model

| Variable | Estimate | SE | z | Std. est. |

| Authoritative parenting factor loadings | ||||

| R-rated movie restriction | 1 | 0 | 0.3 | |

| Parent demandingness | 5.71 | 0.23 | 24.36 | 0.68 |

| Parent responsiveness | 4.61 | 0.56 | 8.27 | 0.56 |

| Structural coefficients | ||||

| Parenting to R-rated movie exposure | −0.75 | 0.08 | −9.3 | −0.12 |

| Parenting to alcohol inititiation | −0.93 | 0.19 | −4.84 | −0.15 |

| R-rated movie restriction to R-movie exposure | −0.62 | 0.02 | −28.87 | −0.57 |

| R-rated movie exposure to alcohol initiation | 0.18 | 0.05 | 3.49 | 0.1 |

| R-rated movie restriction to alcohol initiation | −0.44 | 0.08 | −5.86 | −0.24 |

| Means or intercepts or thresholds | ||||

| R-rated movie exposure | 0.92 | 0.03 | 27.34 | 0.81 |

| R-rated movie restriction | 1.48 | 0.04 | 33.39 | 1.42 |

| Parent responsiveness | 9.55 | 0.07 | 139.42 | 3.68 |

| Parent demandingness | 8.27 | 0.07 | 127.01 | 3.13 |

| Alcohol initiation threshold | 1.23 | 0.12 | 10.36 | 0.64 |

| Variances or residual variances | ||||

| Parenting | 0.1 | 0.01 | 10.31 | 1 |

| R-rated movie exposure | 0.86 | 0.02 | 41.38 | 0.66 |

| R-rated movie restriction | 0.99 | 0.02 | 59.72 | 0.91 |

| Parent responsiveness | 4.65 | 0.29 | 16.23 | 0.69 |

| Parent demandingness | 3.78 | 0.34 | 11.25 | 0.54 |

Note: The model controls for gender, grade in school, parental education, school performance, ever smoking, self-esteem, rebelliousness, sensation seeking, and friend drinking.

Discussion

This study confirms a longitudinal association between young adolescents' perceptions of R-movie viewing rules and subsequent alcohol initiation that was first reported in cross-sectional study (Dalton et al., 2006) and for a longitudinal German adolescent study (Hanewinkel et al., 2008) that showed that lower exposure to movies mediates the relation between parental restrictions and behavior. This study confirms a plausible causal pathway, from restriction, to lower exposure to movies and movie alcohol depictions, to lower risk of alcohol use and suggests that the effects of media parenting are distinct from parenting measures that define the authoritative parenting construct.

The study raises the question of how R-movie exposure affects alcohol use. Youth who say that their parents allow them to watch R movies see more R movies and, therefore, more depictions of alcohol use. Previous cross-sectional studies have shown that movie alcohol use is associated with teen alcohol use (Hanewinkel et al., 2008; Sargent et al., 2006). Thus, the mechanism could be social influence via modeling of positive depictions of alcohol use (Roberts et al., 1999) and generation of more favorable attitudes toward use of alcohol. This pathway was confirmed by a recently published structural analysis (Dal Cin et al., 2009). However, there are other pathways that could be active, such as exposure to other “adult” content in R movies, potentially increasing levels of risk taking or deviance over time, which could also lead to alcohol use. Supporting this pathway, Stoolmiller and colleagues (2010) have shown a reciprocal relation between R-movie exposure and sensation seeking, such that growth in the two constructs is correlated over time.

The structural model in this article extends previous results by isolating media parenting as an area separate from authoritative parenting style. The latent variable model demonstrates that more authoritative parenting results in lower use of alcohol during early adolescence, in part because those adolescents view fewer R movies. However, media parenting seems to be a construct with important direct and indirect effects that are distinct from authoritative parenting. The remaining direct effect of media parenting on alcohol initiation suggests that there may be other aspects of media exposure (or how children respond to it) that are impacted when media parenting takes place, fertile ground for further research.

This study has several strengths. The longitudinal design allowed us to ascertain risk variables before the onset of adolescent drinking, and use of a meditational, latent variable analysis allowed us to separate the effect of authoritative parenting from media restriction and suggest a mechanism accounting for the effect. There are also limitations. The study is limited to early onset of alcohol use but is not able to address whether parental movie restriction is related to frequency and quantity of alcohol use, heavy episodic drinking, or problem behavior associated with alcohol use (e.g., not doing as well in school because of alcohol use, doing something regretted while drinking, drinking and driving, or getting hurt or getting arrested while drinking). However, early onset of alcohol use has been shown to be a mediator for later problems (Hawkins et al., 1997). The outcome measure—trying alcohol “your parents didn't know about”—was phrased in an effort to remove adolescents who had consumed alcohol with parents only as part of meals or family or religious occasions; therefore, we cannot comment on how movie restrictions affect other parentally sanctioned drinking, which some view as also linked with drinking problems (Fergusson et al., 1994). hi addition, this question may not capture parent-discovered alcohol use; given that parents are often unaware of their children's alcohol use (Bogenschneider et al., 1998), we think this underestimation is likely to be small.

Use of a single-item measure to assess R-movie restriction could be viewed as a limitation lowering reliability and limiting our ability to detect an effect; despite that limitation, we detected significant relations with alcohol initiation. The single-item measure omitted other media-related parenting factors, such as restriction of other media (e.g., television and videogames) or co-viewing movies. Such media parenting practices are important areas for further inquiry, because they may account for the remaining direct effect of media parenting, over and above that mediated by reduced exposure to R movies.

Regarding covariates, peer drinking was measured only at follow-up; however, that should result in an overestimation of its effect, because peer substance use is a proximal risk factor and can even be viewed as a mediating variable (Dal Cin et al., 2009; Wills et al., 2007, 2008). We also did not assess parental alcohol use or home alcohol access. Although these family variables were associated early alcohol initiation in some studies (Jackson, 1997; Komro et al., 2007), in others, parental use of alcohol was only a weak predictor of youth alcohol use (Beck and Treiman, 1996; Poelen et al., 2007) or had no (or even a negative) relation to this risk behavior (Boyle et al., 2001; Poikolainen et al., 2001; van der Zwaluw et al., 2008; Yu, 2003). This suggests that parental drinking is a less important unmeasured con-founder in the present study. However, there may be other unmeasured confounders; for example, it may be that parents who impose movie restrictions differ from those who do not in ways (unrelated to authoritative parenting) that were not measured. Similarly, adolescents who watch R movies or who perceive restrictions on their viewing may differ from other youth, such as general deviance or exposure to some other causal factor. Finally, the sample within this study is a regional, largely White group; therefore, additional studies in multiethnic samples are warranted.

Conclusion

At least one group of media researchers has contended that parents who do not regulate their children's media consumption “have abdicated an important part of their role as parents” (Vandewater et al., 2005, p. 609). This study lends credence to that statement by showing that a certain type of media parenting, R-rated movie restriction, has direct and indirect longitudinal associations with alcohol use over and above the impact of authoritative parenting.

Footnotes

This research was supported by grant CA77026 from the National Cancer Institute and grant AA015591 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

References

- Baumrind D. The influence of parenting style on adolescent competence and substance use. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1991;11:56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Beck KH, Treiman KA. The relationship of social context of drinking, perceived social norms, and parental influence to various drinking patterns of adolescents. Addictive Behaviors. 1996;21:633–644. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00087-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogenschneider K, Wu M-Y, Raffaelli M, Tsay JC. “Other teens drink, but not my kid”: Does parental awareness of adolescent alcohol use protect adolescents from risky consequences? Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1998;60:356–373. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle MH, Sanford M, Szatmari P, Merikangas K, Offord DR. Familial influences on substance use by adolescents and young adults. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2001;92:206–209. doi: 10.1007/BF03404307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushman BJ, Anderson CA. Media violence and the American public: Scientific facts versus media misinformation. American Psychologist. 2001;56:477–489. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.56.6-7.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Elliott MN, Berry SH, Kanouse DE, Kunkel D, Hunter SB, Miu A. Watching sex on television predicts adolescent initiation of sexual behavior. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e280–e289. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-1065-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Cin S, Worth KA, Dalton MA, Sargent JD. Youth exposure to alcohol use and brand appearances in popular contemporary movies. Addiction. 2008;103:1925–1932. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Cin S, Worth KA, Gerrard M, Stoolmiller M, Sargent JD, Wills TA, Gibbons FX. Watching and drinking: Expectancies, prototypes and friends' alcohol use mediate the effect of exposure to alcohol use in movies on adolescent drinking. Health Psychology. 2009;28:473–483. doi: 10.1037/a0014777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton MA, Adachi-Mejia AM, Longacre MR, Titus-Ernstoff LT, Gibson JJ, Martin SK, Beach ML. Parental rules and monitoring of children's movie viewing associated with children's risk for smoking and drinking. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1932–1942. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-3082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton MA, Ahrens MB, Sargent JD, Mott LA, Beach ML, Tickle JJ, Heatherton TF. Relation between parental restrictions on movies and adolescent use of tobacco and alcohol. Effective Clinical Practice. 2002;5:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton MA, Sargent JD, Beach ML, Bernhardt AM, Stevens M. Positive and negative outcome expectations of smoking: Implications for prevention. Preventive Medicine. 1999;29(6 Pt 1):460–465. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan JE, Molina BS. Children's introduction to alcohol use: Sips and tastes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32:108–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00565.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Lynskey MT, Horwood LJ. Childhood exposure to alcohol and adolescent drinking patterns. Addiction. 1994;89:1007–1016. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb03360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age at onset of alcohol use and its association with DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: Results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1997;9:103–110. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber E, DiClemente RJ, Anderson MM, Lodico M. Early drinking onset and its association with alcohol use and problem behavior in late adolescence. Preventive Medicine. 1996;25:293–300. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanewinkel R, Morgenstern M, Tanski SE, Sargent JD. Longitudinal study of parental movie restriction on teen smoking and drinking in Germany. Addiction. 2008;103:1722–1730. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02308.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Graham JW, Maguin E, Abbott R, Hill KG, Catalano RF. Exploring the effects of age of alcohol use initiation and psychosocial risk factors on subsequent alcohol misuse. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:280–290. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Heeren T, Jamanka A, Howland J. Age of drinking onset and unintentional injury involvement after drinking. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284:1527–1533. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.12.1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R, Heeren T, Levenson S, Jamanka A, Voas R. Age of drinking onset, driving after drinking, and involvement in alcohol related motor-vehicle crashes. Accident Analysis and Prevention. 2002;34:85–92. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(01)00002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R, Heeren T, Zakocs R. Age of drinking onset and involvement in physical fights after drinking. Pediatrics. 2001;108:872–877. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.4.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R, Heeren T, Zakocs R, Winter M, Wechsler H. Age of first intoxication, heavy drinking, driving after drinking and risk of unintentional injury among U.S. college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:23–31. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson C. Initial and experimental stages of tobacco and alcohol use during late childhood: Relation to peer, parent, and personal risk factors. Addictive Behaviors. 1997;22:685–698. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(97)00005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson C, Henriksen L, Foshee VA. The Authoritative Parenting Index: Predicting health risk behaviors among children and adolescents. Health Education and Behavior. 1998;25:319–337. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komro KA, Maldonado-Molina MM, Tobler AL, Bonds JR, Muller KE. Effects of home access and availability of alcohol on young adolescents' alcohol use. Addiction. 2007;102:1597–1608. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén & Muthén. MPlus, Version 5.2. Los Angeles, CA: Author; 1998–2007. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. The role of the media in prompting and reducing tobacco use (NCI Tobacco Control Monograph No. 19, NIH Pub. No. 07–6242) Bethesda, MD: Author; 2008, June. [Google Scholar]

- Poelen EA, Scholte RH, Willemsen G, Boomsma DI, Engels RC. Drinking by parents, siblings, and friends as predictors of regular alcohol use in adolescents and young adults: A longitudinal twin-family study. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2007;42:362–369. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poikolainen K, Tuulio-Henriksson A, Aalto-Setala T, Marttunen M, Lonnqvist J. Predictors of alcohol intake and heavy drinking in early adulthood: A 5-year follow-up of 15–19-year-old Finnish adolescents. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2001;36:85–88. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/36.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DF, Foehr UG, Rideout V. Generation M: Media in the lives of 8– 18 year olds (No. 7251) Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DF, Henriksen L, Christenson PG. Substance use in popular movies and music. Rockville, MD: Office of National Drug Control Policy, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JD. Smoking in movies: Impact on adolescent smoking. Adolescent Medicine Clinics. 2005;16:345–370. doi: 10.1016/j.admecli.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JD, Beach ML, Dalton MA, Ernstoff LT, Gibson JJ, Tickle JJ, Heatherton TF. Effect of parental R-rated movie restriction on adolescent smoking initiation: A prospective study. Pediatrics. 2004;114:149–156. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JD, Beach ML, Dalton MA, Mott LA, Tickle JJ, Ahrens MB, Heatherton TF. Effect of seeing tobacco use in films on trying smoking among adolescents: Cross sectional study. BMJ. 2001;323:1394–1397. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7326.1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JD, Dalton MA, Heatherton T, Beach M. Modifying exposure to smoking depicted in movies: A novel approach to preventing adolescent smoking. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2003;157:643–648. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.7.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JD, Wills TA, Stoolmiller M, Gibson J, Gibbons FX. Alcohol use in motion pictures and its relation with early-onset teen drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:54–65. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JD, Worth KA, Beach M, Gerrard M, Heatherton TF. Population-based assessment of exposure to risk behaviors in motion pictures. Communication Methods and Measures. 2008;2:134–151. doi: 10.1080/19312450802063404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoolmiller M, Gerrard M, Sargent JD, Worth KA, Gibbons FX. R-rated movie viewing, growth in sensation seeking and alcohol initiation: Reciprocal and moderation effects. Prevention Science. 2010;11:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s11121-009-0143-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Zwaluw CS, Scholte RH, Vermulst AA, Buitelaar JK, Verkes RJ, Engels RC. Parental problem drinking, parenting, and adolescent alcohol use. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;31:189–200. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9146-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandewater EA, Park S-E, Huang X, Wartella EA. “No— you can't watch that”: Parental rules and young children's media use. Americans Behavioral Scientist. 2005;48:608–623. [Google Scholar]

- Wills T, Sargent J, Stoolmiller M, Gibbons F, Gerrard M. Movie smoking exposure and smoking onset: A longitudinal study of mediation processes in a representative sample of U.S. adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:269–277. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Sargent JD, Stoolmiller M, Gibbons FX, Worth KA, Cin SD. Movie exposure to smoking cues and adolescent smoking onset: A test for mediation through peer affiliations. Health Psychology. 2007;26:769–776. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.6.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J. The association between parental alcohol-related behaviors and children's drinking. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003;69:253–262. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00324-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]