Abstract

We evaluated a brief, embedded teaching strategy for increasing the independence of adults with autism in performing community activities. Initially, community situations were observed to identify an activity that a support staff was performing for an individual. The staff person was then trained to implement SWAT Support (say, wait and watch, act out, touch to guide) involving least-to-most prompting and praise to teach the individual on the spot to complete the activity. SWAT Support was implemented by support staff with 3 adults during break activities at a community job (Study 1), with 1 adult in a grocery store (Study 2), and with another individual in a secretary's office (Study 3). All applications of embedded teaching were accompanied by increased participant independence, which generally maintained across follow-up periods of up to 33 weeks. Results are discussed regarding how practitioners could use the teaching strategy to reduce staff and caregiver completion of activities for adults with autism and increase active community participation.

Keywords: Adults, autism, community participation, embedded teaching

The supports paradigm is a dominant theme underlying service provision for people who have severe disabilities. This paradigm emphasizes the involvement of individuals with disabilities in environments in which people without disabilities spend their time, providing whatever supports are necessary to promote successful participation in those settings (Wolfe, Kregel, & Wehman, 1996). A primary intent is to actively involve people with severe disabilities in typical community environments in contrast to more historically segregated settings (Smith & Philippen, 2005).

Despite widespread acceptance of the community support movement (Smith & Philippen, 2005; Wolfe et al., 1996), challenges with putting this philosophy into practice have been recognized (Thompson et al., 2004). One noted concern is an apparent deemphasis on the skill-acquisition needs of people with severe disabilities (Bailey, 2000). Relatedly, concern exists that support staff may do things for people with severe disabilities rather than teach them skills necessary to participate in ongoing activities (Brown, Farrington, Knight, Ross, & Ziegler, 1999). Our observations as well as others (Cooper & Browder, 1998; Sowers & Powers, 1995) coincide with this contention in that many staff have been observed doing things for individuals, such as ordering their food in fast food restaurants, picking up their tickets prior to entering a movie theater, and opening doors to stores. In these situations, people with severe disabilities tend to fill passive community roles and are prohibited from learning functional skills (Sowers & Powers).

An apparent means of helping individuals with severe disabilities actively participate in community situations is to teach them skills to function in those settings. In this regard, there is a substantial research base on community-based instruction (Inge, Dymond, & Wehman, 1996). Typically with community-based instruction, skills needed in a specific community environment are identified, task analyzed, and then taught in simulation (Lattimore, Parsons, & Reid, 2008; Sowers & Powers, 1995) and/or in the actual setting (Cooper & Browder, 1998, 2001).

Although community-based instruction has been successful in many situations, research on its application seems incomplete for thoroughly assisting people with severe disabilities in functioning more independently in the community. As just indicated, community-based instruction usually involves the identification of relevant community skills and then formally teaching those skills. However, it is improbable that the entire universe of community-participation skills likely to be needed by people with severe disabilities can be identified prior to them accessing various community settings. As individuals encounter new and different community environments, skills needed to actively participate in those settings may arise without prior anticipation by a support staff and may occur infrequently (i.e., limited to a specific setting or activity that is only accessed a few times per month or less). Consequently, providing repeated instructional trials on skills relevant to a particular setting is difficult, as is teaching with a pre-established task analysis.

An alternative approach to community-based instruction would be for support staff to embed brief instructional trials on an impromptu basis as the activities are encountered. Instead of the staff doing an activity for an individual, the staff would briefly instruct the individual in the skills to complete part or all of the activity. Various formats of embedded teaching have been used with children in early intervention settings and classrooms (Johnson, McDonnell, Holzwarth, & Hunter, 2004; Schepis, Reid, Ownbey, & Parsons, 2001). However, like community-based instruction in general, research on embedded teaching has focused on instructional strategies for use within routines that are known beforehand. There has been a lack of emphasis on impromptu, embedded teaching with adults with severe disabilities in community settings.

The purpose of this investigation was to evaluate use of a brief, embedded teaching strategy in community settings with adults who have severe autism. The intent was to identify seemingly simple activities (i.e., those that require a small number of steps to complete and can be completed quickly) that support staff were performing for an individual, and then instruct the staff to use the strategy on the spot to teach the individual to complete the activities. The focus was on adults with severe autism because relatively little research has been conducted with this population (Lattimore et al., 2008; McClannahan, MacDuff, & Krantz, 2002). Additionally, adults with autism are among those for whom the prevailing community-support movement is intended (Smith & Philippen, 2005).

Three studies were conducted. The first study evaluated the embedded teaching strategy in a community job. The effects were then replicated in another community setting (a grocery store). To further examine the potential generality of the embedded teaching strategy, its effects were evaluated with a different adult in a third setting (secretarial office) when applied by a staff who had no previous relevant training.

STUDY 1

Method

Participants and Setting

The 3 participants (supported workers) were men who had been diagnosed with autism on at least two independent evaluations. Each participant was nonvocal and had severe or profound intellectual disabilities. Mel (32 years old) and Ralph (45 years old) responded to simple vocal instructions and communicated with idiosyncratic gestures. Greg (43 years old), who had a severe hearing loss and responded to a small number of manual signs, communicated with a small repertoire of manual signs and idiosyncratic gestures. Each supported worker exhibited stereotypic behavior (e.g., body rocking, finger gazing). These individuals were selected for the investigation because they had autism characteristic of the severe end of the spectrum (Powers, 2000). They also worked part time at a small publishing company in a supported work capacity performing clerical-type tasks such as putting address labels on advertising fliers. Mel and Greg worked two mornings per week, and Ralph worked one morning per week. All experimental procedures except observations were conducted by the job coach who routinely worked with the supported workers. The job coach had 13 years of supported work experience. All aspects of the investigation occurred during the participants' break time in their work area and in an adjacent kitchen/break room at the publishing company.

Target Activities and Behavior Definitions

Target activities were identified prior to initiating baseline by an experimenter who observed the break routine and recorded activities that the job coach completed for a supported worker. Next, those activities performed by the coach for a respective supported worker that involved a small number of actions to complete were behaviorally defined. Two activities were identified and defined for Mel. Take drink was defined as walking to the break room counter, picking up a cup with soda from the counter, and taking it to his break table. Turn on radio was defined as walking to the radio in the break room and turning it on (by plugging it in). Take drink was also defined in the same manner for Ralph and Greg. Additionally, for Greg, getting a sketch pad was defined as walking to an open cabinet in the break room, picking up the sketch pad from the cabinet, taking the pad back to the break table, and setting it on the table (he typically drew on the pad during his break). During the observations prior to baseline, the job coach consistently took the drinks to the workers' table, turned on the radio, and retrieved the sketch pad.

Observation System and Interobserver Agreement

Observations of each target activity were conducted on a probe basis across supported workers and experimental conditions by an experimenter or research assistant. Occurrence of each target activity was recorded within one of five mutually exclusive categories along a continuum of worker independence. The least independent (recorded as “0”) was no opportunity to perform due to the activity being completed by the job coach. The next least independent (recorded as “1”) was a supported worker completing the activity with full physical guidance by the job coach in which the coach maintained physical contact with the worker and guided all worker behavior necessary to complete the activity. A recording of “2” represented more independence in terms of the worker completing the activity with partial physical guidance by the job coach, through which the coach physically guided some but not all of the behaviors to complete the activity. A recording of “3” represented increased independence relative to the preceding categories by the worker completing the behavior following descriptive gestures by the job coach. Finally, a recording of “4” represented the most independence in terms of the worker completing the behavior in response to an instruction to complete the activity.

Interobserver agreement checks were conducted during 32% of all observations, including for each supported worker, activity, and experimental condition. Interobserver agreement was calculated using the formula of number of agreements divided by number of agreements plus disagreements, multiplied by 100%. Occurrence, nonoccurrence, and overall agreement each was 100% for each of the five behavior categories.

Procedure

The intervention was introduced in a staggered fashion across supported workers and target activities within a multiple probe design.

Baseline. The supported workers' break time continued according to the usual routine. The job coach was informed that he should conduct the break in the usual manner. The job coach signaled the beginning of the break, removed the work materials from the workers' work table, and prepared and delivered a drink for each worker. As indicated previously, the job coach also turned on the radio for Mel and retrieved the sketch pad for Greg according to his usual custom. This routine had been ongoing for several years (the workers remained at their work table for the break). After approximately 15 min, the job coach removed the break materials, replaced the work materials on the table, and instructed the workers to resume working.

SWAT Support. The intervention consisted of the job coach's systematic use of brief, least-to-most prompting with contingent praise. The three-step prompting process (Wilder, Atwell, & Wine, 2006) was referred to as SWAT Support, an acronym for “say, wait and watch, act out, and touch to guide.” SWAT Support consisted of the following steps. Step 1 (say) involved the job coach vocally instructing the worker to perform the target activity (e.g., “Mel, turn on the radio”). Step 2 (wait and watch) involved waiting at least 3 s for the worker to initiate the task. If the worker did not initiate the first behavior to complete the activity, Step 3 (act out) involved the job coach gesturing the motions necessary to complete the activity (e.g., walking toward and pointing to the radio) while describing the steps and repeating Step 2 (wait and watch). If the worker still did not initiate the first behavior, Step 4 (touch to guide) involved the job coach providing physical assistance by placing his hand(s) on the worker's hand(s) or arm(s) and guiding the worker through part of the first behavior in the activity and then removing his hand(s) to within 8 cm of the worker's arm(s) or hand(s). The job coach re-initiated the guidance if the worker stopped performing the behavior or engaged in an incompatible behavior. The Step 4 process continued until the worker completed each behavior necessary to complete the target activity. Throughout the prompting process, if a supported worker continued engaging in the behaviors necessary to complete the activity, the job coach refrained from interacting with the worker but closely monitored the worker's behavior. Once the worker completed the activity with SWAT Support, the job coach praised the worker's performance (see subsequent discussion of intervention integrity checks and Table 1 for elaboration on the SWAT Support process). Because Greg had a severe hearing loss, the process was altered slightly by using manual signing for Step 1 instead of a vocal instruction and signing “good” instead of delivering vocal praise.

Table 1.

Criteria for Correct Implementation of SWAT Support

| Intervention Step | Criteria |

| 1. Say | Tells participant what to do by identifying target behaviors to complete. |

| 2. Wait and Watch | Looks at participant and waits at least 3 s before proceeding with next prompt. |

| 3. Act Out | Gestures movements necessary to perform the activity, tells what to do, and repeats Step #2. |

| 4. Touch to Guide | Provides physical assistance by placing hand(s) on participant's hand(s) or arm(s) and guides through part of activity and then removes hand(s) to within 8 cm of participant's hand(s) or arm(s); reinitiates physical assistance in same manner only if participant stops performing activity or makes an error; process is repeated until participant completes activity. |

| 5. Praise | Provides praise statement upon completion of activity. |

The job coach was trained in the SWAT Support process through vocal and written instructions and role-play practice with feedback. The training required 10 min. Upon initial implementation of the intervention with the first target activity and worker, the job coach was instructed to proceed per the usual break routine up to the point at which the first behavior of the activity was to be performed and then use SWAT Support to involve the worker. The coach was also instructed to continue performing all other break activities in exactly the same manner as he typically conducted them. For subsequent applications of the intervention across workers and activities, the job coach was just instructed to use SWAT Support with that respective activity and again instructed to continue doing everything else with other activities according to the usual routine. After the break routine, vocal feedback was provided to the job coach by an experimenter regarding the level of independence displayed by the supported worker(s) for each target activity for which SWAT Support had been applied. Additionally, for those observations that included an integrity check (see following discussion), the job coach was provided vocal feedback regarding the SWAT Support steps that he implemented correctly and incorrectly (the latter only if applicable).

Integrity checks on the job coach's use of SWAT Support were conducted by an experimenter. Table 1 provides additional information regarding correct use of the process for each respective step. Probes were conducted for each worker and activity during 70% of all intervention sessions. Interobserver agreement checks were conducted on 27% of all integrity checks, including for each worker and activity. Interobserver agreement was calculated as described previously on an intervention step-by-step basis for correct implementation of each step by the job coach. Interobserver agreement averaged 97% (range, 80% to 100%) for occurrence of correct step implementation, 95% (range, 67% to 100%) for nonoccurrence, and 98% (range, 86% to 100%) for overall agreement. Across all integrity checks, the job coach averaged 95% correct implementation of the steps (range, 67% to 100%). Time-measurement probes indicated the SWAT Support process typically required less than 1 min to carry out and never as much as 2 min.

Follow up. Following completion of the intervention, the job coach continued using the SWAT Support process during the break routine. Follow-up observations were conducted at periods ranging from 3 to 33 weeks.

Results

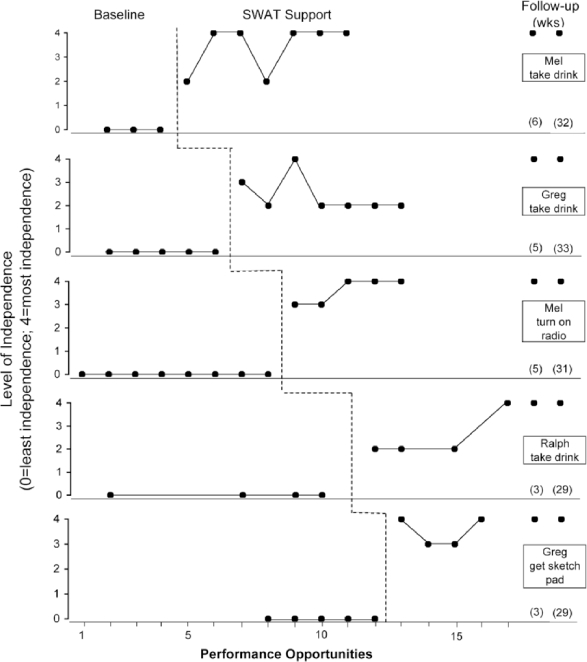

Figure 1 shows the results for the 3 participants. During baseline observations of performance opportunities (maximum of one per each work day per supported worker) for each target activity, the job coach completed every activity for each supported worker. Once SWAT Support was initiated, each supported worker immediately performed some of the behaviors for each activity. The level of independence on the first observation during SWAT Support involved partial physical guidance (score of “2”) for take drink for Mel and Ralph, gesturing (score of “3”) for take drink for Greg and turn on radio for Mel, and complete independence (score of “4”) for get sketch pad for Greg. The level of independence then increased across performance opportunities during SWAT Support for Mel for take drink and turn on radio and for Ralph for take drink, and stayed relatively stable for Greg for take drink and get sketch pad. Each worker maintained or increased to independent performance of each target activity during the follow-up observations.

Figure 1.

Level of independence demonstrated during each performance opportunity by each participant for each activity during baseline and SWAT Support. Level of independence is represented by “0” (least independent – performed by support staff), “1” (performed by participant with full physical guidance), “2” (performed with partial physical guidance), “3” (performed following a gesture prompt), and “4” (most independent – performed following the initial instruction).

Results indicated implementation of SWAT Support was accompanied by increased and maintained independence among all participants in completing the work-break activities in a community job. The support staff person was not provided with a pre-established task analysis of the target activities, only with on-the-spot instruction to use the embedded teaching strategy to help a given supported worker complete a respective activity and to continue using the strategy with the activity in the future. SWAT Support required a brief amount of time to implement and was consistently carried out by the job coach in an accurate manner.

STUDY 2

The purpose of Study 2 was to determine if the support staff who participated in Study 1 could successfully generalize the intervention for one of the participants in a different setting.

Method

Participant and Setting

The setting was a grocery store in the local community where the participant (Mel, who participated in Study 1) accompanied a staff person to purchase food and supplies for Mel's residence. The support staff was the same individual who was the job coach in Study 1.

Target Activity, Behavior Definitions, Observation System, and Interobserver Agreement

Target activities were identified as in Study 1 by an experimenter observing the entire grocery shopping routine, recording activities that the support staff performed for the participant, and then selecting two of the latter activities that involved a small number of actions to complete. One activity was place item in shopping cart, defined as the participant picking up a designated food or supply item from a shelf in the grocery store and placing the item in the shopping cart. The other activity was push cart, defined as pushing the shopping cart down the aisle after all items designated by the support staff were placed in the shopping cart (by either the staff person or participant) at a given stop along the shopping aisle. During the pre-baseline observations, the support staff consistently placed items in the shopping cart and pushed the cart while the participant stood by or followed, respectively.

Observations of the two target activities were conducted as in Study 1, with recordings of the participant's completion of a target activity being scored in one of the five mutually exclusive categories. However, in contrast to Study 1 in which only one performance opportunity was observed per work day per participant, there were multiple opportunities for the target activities to be observed during each shopping trip (range from 4 to 10 opportunities observed across shopping trips). Interobserver agreement checks occurred on 57% of all observations, including both experimental conditions and target activities. There was only one disagreement between observers regarding the participant's response category across all interobserver agreement checks.

Procedure and Design

During baseline, the support staff and participant conducted the grocery shopping activity according to their usual procedures. Every 1 or 2 weeks on average, the support staff obtained a list of items from Mel's residence that needed to be purchased, escorted Mel in a van to the grocery store, and completed the shopping. During the SWAT Support intervention, the support staff used the same prompting and praise procedures described in Study 1. The job coach was first asked to use SWAT Support with the push cart activity and to continue all other actions as he typically performed them. Subsequently, he was asked to use SWAT Support for the place items activity. Following completion of the formal SWAT Support conditions, the support staff was asked to continue using SWAT Support during his grocery shopping trips with the participant. Follow-up observations were then conducted 5 weeks later. The experimental design was a multiple baseline across the two target shopping activities.

Integrity checks on the support staff's application of SWAT Support were conducted as in Study 1 during all observations during the intervention conditions. Interobserver agreement checks were conducted on 29% of the integrity checks, including for both shopping activities, with no disagreements between observers. Across all integrity checks, the support staff correctly completed an average of 91% of the intervention steps correctly (range, 67% to 100%).

Results

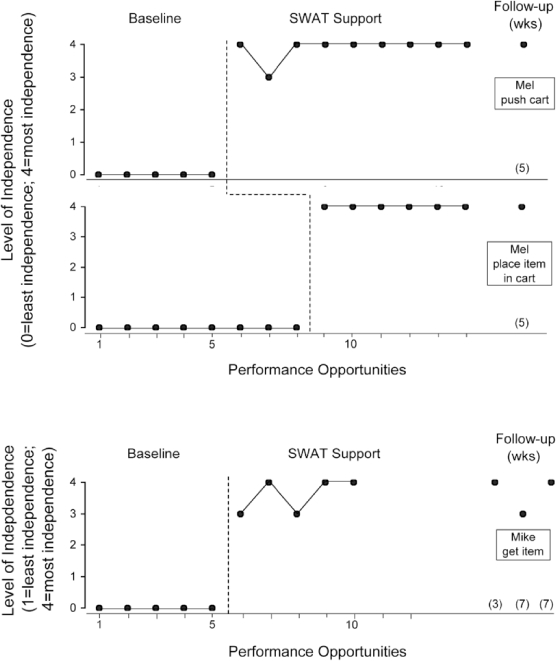

As indicated on Figure 2 (top two panels), the least independent category (“0” — no opportunity; performed by the support staff) was recorded for every performance opportunity for both shopping activities during baseline. In contrast, once SWAT Support was initiated, the participant performed both activities independently (score of “4”) on every occasion except one for the push cart activity (score of “3” – performed following a gesture). Independent performance maintained during follow-up.

Figure 2.

Level of independence demonstrated during each performance opportunity by participant Mel (top two panels) and Mike (bottom panel) for each activity during baseline and SWAT Support. Level of independence is represented by “0” (least independent – performed by support staff), “1” (performed by participant with full physical guidance), “2” (performed with partial physical guidance), “3” (performed following a gesture prompt), and “4” (most independent – performed following the initial instruction).

Similar to results of Study 1, results of Study 2 indicated SWAT Support was accompanied by increased independence of the adult with autism in performing two (seemingly simple) activities that previously were being performed for the participant by the support staff. In contrast to Study 1, the participant in the current study appeared to have the skills to complete the activities in his repertoire or readily acquired the skills following an initial vocal instruction. However, he was not given an opportunity to perform the skills during baseline because the staff person was completing the activities. For the most part, the participants in Study 1 appeared to learn to complete the activities across repeated applications of the teaching strategy. Because no formal evaluations were conducted of the participants' skills in completing the activities prior to baseline, the actual degree to which they may have had the skills in their repertoire is unknown. Hence, whether SWAT Support involved teaching new skills versus prompting to use existing skills cannot be conclusively determined.

STUDY 3

To further evaluate the utility and generality of the SWAT Support strategy, we examined its effectiveness in another setting with a different adult with autism and a staff member who had no prior support work experience.

Method

Participant and Setting

The participant, Mike, attended an adult education program at a large multi-service agency that provided supports for people with disabilities from a residential facility and the local community. Mike was 43 years old and had been diagnosed with autism and severe intellectual disabilities. He communicated using short phrases when specifically prompted. Mike usually followed simple, familiar requests from adults. Mike was selected for the study because he had severe autism and was periodically sent by his adult education teacher to the secretarial office with a note to obtain a particular supply item (usually paper cups for use in the classroom). The secretary, who served as the support staff person, was 49 years of age and had 16 years experience as a secretary. She had no formal training in how to teach people with disabilities. The setting was the secretary's office.

Target Activity, Behavior Definitions, Observation System, and Interobserver Agreement

The target activity was getting the supply material on the note provided by the teacher. It was selected because an experimenter had repeatedly observed that the participant entered the secretary's office and gave the note to the secretary, and the secretary then obtained the item from the supply room and gave it to the participant. Subsequently, the target activity, get item, was defined as the participant walking into the supply room behind the secretary's desk and picking up the identified item (following an instruction from the secretary). Observations were conducted as described previously as were interobserver agreement checks (during 46% of observations, including both experimental conditions). There were no disagreements between observers during any interobserver agreement check.

Procedure

During baseline, the supply-retrieval process was conducted according to the usual routine. Mike was sent to the secretarial office to obtain the supply item generally once every 2 weeks or so. Following baseline, the secretary was trained in approximately 15 min to conduct SWAT Support in the same manner as described with the job coach in Study 1. She was then asked to use the process each time Mike arrived to obtain an item after she read what was on his note. Follow-up observations were conducted on three occasions across a 7-week period following the end of the intervention condition. Integrity checks were conducted as described previously during 88% of all intervention applications. Interobserver agreement observations were conducted during 29% of the integrity checks, with no disagreements between observers. The secretary implemented 100% of the intervention steps correctly. The design was a quasi-experimental AB design (Bailey & Burch, 2002, chap. 7).

Results

During baseline, the secretary always completed the get item activity for the participant on all opportunities (resulting in a score of “0” – least independent performance; see bottom panel of Figure 2). Following initiation of SWAT Support, the participant immediately showed more independence in completing the activity following either a gesture prompt (score of “3”) or independently (score of “4”). The participant completed the activity independently on two opportunities and following a gesture on one opportunity during the follow-up observations. The latter opportunity followed a 4-week period during which the participant had no opportunities to complete the activity due to a holiday break. The lack of opportunity to complete the activity may have resulted in the temporary decrease in independent performance.

Conclusions and Guidelines for Practitioners

Results of the three studies suggest that the SWAT Support strategy represents a viable means for increasing independence of adults with severe autism in performing selected community activities that are currently being performed for them by others. Each adult showed increased independence each time SWAT Support was implemented across the three settings, and each displayed independent performance across follow-up periods ranging up to 33 weeks. The teaching strategy required a brief amount of time to implement (always less than 2 min) and the 2 support staff consistently implemented the strategy following a brief amount of training (maximum of 15 min). It is particularly noteworthy that one of the support staff (the secretary) had no prior relevant training or experience, yet she learned the SWAT Support procedures quickly and implemented them with high integrity. This finding suggests that behavior analysts can successfully teach a variety of individuals to implement SWAT Support, including caregivers and family members.

In considering the results, it should be noted that independent performance was defined as completing the community activity in response to an instruction by a support staff. Completing the activity in this manner was considered independent (i.e., in contrast to performing the activity in response to a more natural cue in the community setting) because of the situation in which the activity was relevant. The intent of SWAT Support was to be a quick, on-the-spot means of teaching an individual to perform at least part of an activity that a support staff would typically perform for the individual. As indicated previously, there are likely many situations in which activities are encountered in community settings that are not specifically anticipated and that occur infrequently. As such, it may not be viable to target these skills with a task analysis, simulated instructional trials, etc. In these situations, an individual with severe autism would not be expected to initially perform an activity without instruction from a support staff because the individual would likely have no knowledge of what is expected. If some of the activities were encountered repeatedly over time, however, it would be more desirable for an individual to respond to a natural cue to perform an activity. Such an outcome was observed on a number of occasions after the formal SWAT Support condition was completed. For example, Mel turned on the radio (Study 1), Greg got his sketch pad (Study 1), Mel pushed the grocery cart (Study 2), and Mike got the cups after handing the note to the secretary (Study 3) without a staff instruction.

Results of the three studies also suggest some qualifications and directions for future research. First, none of the participants had recent histories of demonstrating problem behavior to escape or avoid instructions. The teaching strategy may be less successful with people for whom instructions tend to occasion problem behavior. Research is needed to evaluate the process with the latter individuals as well as adults with severe disabilities other than autism. Second, the community activities targeted were specifically selected because they involved a small number of behaviors and could be completed quickly. It was assumed that these types of activities would be more amenable to SWAT Support than complex activities. Research would be useful to determine if SWAT Support could be effective with the latter types of activities. Third, SWAT Support was only implemented by 2 staff. Research seems warranted to evaluate the strategy when used by other indiviudals as well as to formally evaluate means of quickly training staff to use the strategy.

Another limitation is that no measures were included to determine whether the 2 staff used SWAT Support when the experimenter was not observing their work with the participants (Brackett, Reid, & Green, 2007). It would be desirable for staff to use the approach routinely. Specific supervisory or self-management procedures may be needed with some staff to ensure such routine application (cf. Brackett et al.).

In light of the results and qualifications just noted, the following suggestions for routine practice are offered. First, support staff should be trained via instructions, role play, and feedback to use the embedded teaching strategy. Subsequently, when a staff person accompanies an adult with severe autism in a community setting, the staff should consider quickly teaching the person to do an activity for him/herself rather than doing a seemingly simple activity for the individual. The acronym “SWAT” (for say, wait and watch, act out, touch to guide) could serve as a mnemonic cue regarding how to prompt the individual through the activity. It is further recommended that SWAT Support be used as a supplement to more traditional, pre-planned community-based instruction (Cooper & Browder, 1998, 2001). At this point it would seem advantageous to use formal community-based instruction for skills that are more complex (e.g., requiring numerous task-analyzed steps) and are known to be needed in a setting that is likely to be encountered routinely. Embedded teaching could be used in addition to formal community-based instruction for simple skills and for activities that are encountered on a first-time or infrequent basis. Using this type of quick, embedded teaching could help resolve concerns over staff doing things for people with severe disabilities that prohibit the individuals from learning functional skills and actively participating in community life (Brown et al., 1999).

Footnotes

Appreciation is expressed to Carolyn Green and Cason Reid for their assistance with data collection. Requests for reprints should be sent to Dennis H. Reid, Carolina Behavior Analysis and Support Center, P.O. Box 425, Morganton, North Carolina 28680.

Contributor Information

Marsha B Parsons, J. Iverson Riddle Center, Morganton, North Carolina

Dennis H Reid, Carolina Behavior Analysis and Support Center.

L. Perry Lattimore, J. Iverson Riddle Center

References

- Bailey J. S. A futurist perspective for applied behavior analysis. In: Austin J, Carr J. E, editors. Handbook of applied behavior analysis. Reno, NV: Context Press; 2000. pp. 473–488. (Eds.) [Google Scholar]

- Bailey J. S, Burch M. R. Research methods in applied behavior analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Brackett L, Reid D. H, Green C. W. Effects of reactivity to observations on staff performance. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2007;40:191–195. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2007.112-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown L, Farrington K, Knight T, Ross C, Ziegler M. Fewer paraprofessionals and more teachers and therapists in educational programs for students with significant disabilities. Journal of The Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps. 1999;24:250–253. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper K. J, Browder D. M. Enhancing choice and participation for adults with severe disabilities in community-based instruction. Journal of The Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps. 1998;23:252–260. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper K. J, Browder D. M. Preparing staff to enhance active participation of adults with severe disabilities by offering choice and prompting performance during a community purchasing activity. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2001;22:1–20. doi: 10.1016/s0891-4222(00)00065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inge K, Dymond S, Wehman P. Community-based vocational training. In: McLaughlin P. J, Wehman P, editors. Mental retardation and developmental disabilities. 2nd ed. Austin, TX: ProEd; 1996. pp. 297–315. (Eds.) [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J. W, McDonnell J, Holzwarth V. N, Hunter K. The efficacy of embedded instruction for students with developmental disabilities enrolled in general education classes. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2004;6:214–227. [Google Scholar]

- Lattimore L. P, Parsons M. B, Reid D. H. Simulation training of community job skills for adults with autism: A further analysis. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2008;1:24–29. doi: 10.1007/BF03391717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClannahan L. E, MacDuff G. S, Krantz P. J. Behavior analysis and intervention for adults with autism. Behavior Modification. 2002;26:9–26. doi: 10.1177/0145445502026001002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers M. D. What is autism. In: Powers M. D, editor. Children with autism: A parents' guide. Bethesda, MD: Woodbine House; 2000. pp. 1–44. (Ed.) [Google Scholar]

- Schepis M. M, Reid D. H, Ownbey J, Parsons M. B. Training support staff to embed teaching within natural routines of young children with disabilities in an inclusive preschool. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2001;34:313–327. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2001.34-313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M. D, Philippen L. Autism. In: Wehman P, McLaughlin P. J, Wehman T, editors. Intellectual and developmental disabilities. Austin, TX: ProEd; 2005. pp. 309–323. (Eds.) [Google Scholar]

- Sowers J, Powers L. Enhancing the participation and independence of students with severe physical and multiple disabilities in performing community activities. Mental Retardation. 1995;33:209–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. R, Bryant B. R, Campbell E. M, Craig E. M, Hughes C. M, Rotholz D. A, et al. Supports intensity scale users manual. Washington, DC: American Association on Mental Retardation; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wilder D. A, Atwell J, Wine B. The effects of varying levels of treatment integrity on child compliance during treatment with a three-step prompting procedure. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2006;39:369–373. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2006.144-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe P, Kregel J, Wehman P. Service delivery. In: McLaughlin P. J, Wehman P, editors. Mental retardation and developmental disabilities. 2nd ed. Austin, TX: ProEd; 1996. pp. 3–27. (Eds.) [Google Scholar]