Abstract

During development, Gamma-aminobutyric acidergic (GABAergic) neurons mature at early stages, long before excitatory neurons. Conversely, GABA reuptake transporters become operative later than glutamate transporters. GABA is therefore not removed efficiently from the extracellular domain and it can exert significant paracrine effects. Hence, GABA-mediated activity is a prominent source of overall neural activity in developing CNS networks, while neurons extend dendrites and axons, and establish synaptic connections. One of the unique features of GABAergic functional plasticity is that in early development, activation of GABAA receptors results in depolarizing (mainly excitatory) responses and Ca2+ influx. Although there is strong evidence from several areas of the CNS that GABA plays a significant role in neurite growth not only during development but also during adult neurogenesis, surprisingly little effort has been made into putting all these observations into a common framework in an attempt to understand the general rules that regulate these basic and evolutionary well-conserved processes. In this review, we discuss the current knowledge in this important field. In order to decipher common, universal features and highlight differences between systems throughout development, we compare findings about dendritic proliferation and remodeling in different areas of the nervous system and species, and we also review recent evidence for a role in axonal elongation. In addition to early developmental aspects, we also consider the GABAergic role in dendritic growth during adult neurogenesis, extending our discussion to the roles played by GABA during dendritic proliferation in early developing networks versus adult, well established networks.

Keywords: GABA, GABAA receptor, dendrite, axon, development, adult neurogenesis, paracrine

Introduction

Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is the main inhibitory neurotransmitter in mature neural networks. However, there is now a plethora of evidence demonstrating that GABAergic signalling plays important functions in the developing CNS and during adult neurogenesis long before synapse formation, exerting numerous trophic, paracrine roles, ranging from controlling cell proliferation and migration to neurite outgrowth, synapse formation and cell death (for review see Ben-Ari et al., 2007; Ge et al., 2007; Wang and Kriegstein, 2009).

GABA can act on three types of receptors, namely GABAA, GABAB and GABAC types. The early trophic effects of GABA are mostly mediated by the activation of ionotropic GABAA receptor linked to a Cl− channel. GABAA receptors are pentomeric complexes composed of several subunits belonging to seven families (α1–6, β1–4, γ1–3, δ, ρ1–2) of membrane proteins, linked to the synaptic anchoring protein gephyrin and to the cytoskeleton. These subunits can assemble in various combinations, which in vivo are generally composed of isoforms of α, β and γ subunits, yielding a large variety of GABAA receptors subtypes (for review see Mohler, 2007). The structural diversity of these isoreceptors determines their functional properties (e.g. channel kinetics, affinity to ligands, desensitization properties), and different cell types can express different GABAA receptor isoforms. Therefore, these cells can also have different sensitivity to GABAergic activation. The precise composition of GABAA receptors subunits is not fixed at early developmental stages; it appears to be a rather dynamic process that may be modulated by GABA itself (Cobas et al., 1991). Although the subunit complexes vary in different cell types, general rules apply to developmental changes in the composition of GABAA receptors. During early development, α2, β2/3 subunits are prominent while the α1 subunit is scarce (Hornung and Fritschy, 1996). As development progresses, there is an increase in α1 subunits with a concomitant decrease in α2 subunits whilst the expression of β2/3 subunits remains unchanged. The switch from α1 to α2 subunits coincides with synapse formation and may be associated with the emergence of synaptic inhibition. The γ2 subunit is highly expressed at early stages, as it is required for postsynaptic, clustering of GABAA receptors (Essrich et al., 1998). Tonic GABAergic activity as it occurs during early development involves different subunits such as δ or α5 (for review see Farrant and Nusser, 2005).

In the mature brain, GABAA receptor activation leads to Cl− influx, resulting in hyperpolarization (inhibition) of the cell. In immature neurons (both during early development and adulthood), however, GABAA receptor activation is depolarizing and mainly excitatory (LoTurco et al., 1995; Ben-Ari et al., 2007; Ge et al., 2007; Wang and Kriegstein, 2009). The depolarizing effect of GABA in developing neurons is due to an efflux rather than influx of Cl− ions following activation of GABAA receptors, because the intracellular Cl− concentration is higher than in mature cells. Such reverse Cl− gradient depends on a high expression of the Na+/K+/Cl− cotransporter NKCC1 (Blaesse et al., 2009), which pumps Cl− inside the immature neuron, and a low expression of the K+/Cl− cotransporter KCC2, which normally extrudes Cl− from mature neurons (Rivera et al., 1999). This Cl−-mediated depolarization provides a strong excitatory drive that can trigger action potentials (Leinekugel et al., 1997) and opening of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels (VDCCs). This, in turn, leads to Ca2+ influx and transient increases in intracellular Ca2+ (Yuste and Katz, 1991; Tozuka et al., 2005; Goffin et al., 2008), which will exert a variety of trophic effects. The shift from GABAergic excitation to inhibition occurs as KCC2 expression and functionality increase with maturation. The role of cation-Cl− co-transporters in controlling the nature of GABAA responses is a universal phenomenon that is well preserved across development, brain areas and animal species (for review see Blaesse et al., 2009).

Depolarizing GABAergic activity is present at the earliest stages of network activity, long before the onset of sensory experience, when the developing CNS is spontaneously active, neurons extend dendrites and axons, and they establish synaptic connections. This was first reported in the hippocampus, where immature pyramidal cells exhibit GABA-mediated giant depolarizing potentials before the maturation of glutamatergic synapses (Ben-Ari et al., 1989). Early spontaneous GABAergic activity has since been reported in many immature systems including the neocortex, hypothalamus, spinal cord, ventral tegmental area, cerebellum, retina and olfactory bulb (for review see Ben-Ari, 2002) as well as during adult neurogenesis (for review see Bordey, 2007).

The GABAergic transition from excitation to inhibition is activity-dependent. An initial in vitro study reported that GABAergic activity regulates its own switch from excitation to inhibition (Ganguly et al., 2001). Although this finding was successively challenged (Ludwig et al., 2003), it was then confirmed in the retina in vivo (Leitch et al., 2005). Interestingly, a recent study reported that spontaneous cholinergic nicotinic activity (in chick ciliary ganglion, spinal cord and hippocampus) triggered the GABAergic shift from excitation to inhibition (Liu et al., 2006). Cholinergic nicotinic blockade (in dissociated cultures or in animals knockout for nicotinic cholinergic receptors) prevented GABAA responses from becoming hyperpolarizing, and this was due to the retention of an immature expression pattern of Cl− transporters. This early cholinergic nicotinic role may be of particular relevance in the retina where the earliest spontaneous network activity consists of acetylcholine (nicotinic)-mediated waves spreading across the retinal ganglion cell (RGC) layer (for review see Sernagor et al., 2001). Interestingly, depolarizing GABAA activity becomes involved in controlling the dynamics of the waves at later stages (Sernagor et al., 2003; Syed et al., 2004). Indeed, as it gradually shifts to become inhibitory, it downregulates retinal waves, causing them to slow down and become narrower until they eventually disappear (Sernagor et al., 2003).

The goal of this review is to recapitulate the current knowledge about the role of GABA in neurite outgrowth during development and in adult neurogenesis. Although many studies addressing these important issues have been published, so far little attempt has been made to put all these observations into a common framework in an attempt to understand the general rules that regulate these basic and evolutionary well-conserved processes.

In Vitro Studies

The first evidence that GABA may affect neurite outgrowth was provided by Eins et al. (1983). Indeed, they demonstrated that differentiated C1300 mouse neuroblastoma cells treated with GABA showed an increase in the length and branching of processes (Eins et al., 1983). A large amount of in vitro evidence has been provided ever since in several brain areas and diverse species.

Cortex

GABA treatment promotes neurite length and branching in mixed (inhibitory and excitatory) cortical neurons in embryonic chick and rat cultures (Baloyannis et al., 1983; Spoerri, 1988), and in rat interneurons in cultures from cortical plate and subplate microdissections (Maric et al., 2001). Conversely, treatment of rat neurons in culture with the GABAA receptor antagonist bicuculline inhibited the extent of neuritic arborization (Ben-Ari et al., 1994; Maric et al., 2001). Interestingly, agents that blocked GABA synthesis caused a reduction of neurite outgrowth. Moreover, in the absence of GABAergic signaling, neuritogenesis was preserved by depolarizing cells and elevating the intracellular Ca2+ concentration. Activation of high-threshold L-type Ca2+ channels per se mimicked the GABA-induced effect. Furthermore, neurite growth could also be antagonized by blocking the Cl− accumulating pump NKCC1 (Maric et al., 2001). Finally, the effects on neurite outgrowth were absent if the GABAA agonist was given after the shift of GABAergic signaling from hyperpolarizing to depolarizing had taken place (Maric et al., 2001). All together, these results suggest an involvement of depolarizing GABA and consequent intracellular Ca2+ elevation for GABAA-mediated effect on neurite growth.

GABAB receptors may also play a role in regulating neurite outgrowth as exposure of cortical organotypic slices to a specific GABAB receptor antagonist resulted in a decrease in the length of the leading process in migrating inhibitory neurons (Lopez-Bendito et al., 2003).

Hippocampus

Numerous studies showed that modulation of GABAA-receptor signaling influences neurite growth in hippocampal rodent neurons in cultures. In particular, Barbin et al. (1993) showed a reduction in the number of primary neurites and branching points (resulting in a concomitant decrease of the total neuritic length) upon treatment of cell cultures with bicuculline. Interestingly, the authors reported no effect on neurite outgrowth after treatment with the specific GABAA receptor agonist muscimol, possibly indicating a role for tonic-GABA signaling in the process (Barbin et al., 1993). In the latter study, authors did not differentiate between excitatory and inhibitory neurons in the cultures. Conversely, muscimol did induce an increase in the number and length of primary dendrites in cultured inhibitory interneurons (Marty et al., 1996). Notably, application of muscimol reduced the number of primary dendrites when applied 2 weeks after plating (after the excitatory to inhibitory switch of GABA responses takes place), again suggesting the requirement of depolarizing GABA. Interestingly, in a recent paper, a possible involvement of the α5 subunit (but not β2) of the GABAA receptor was suggested for the GABA-induced effect on neurite outgrowth via lowering of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels in hamster hippocampal neurons treated with a specific α5 inverse agonist (Giusi et al., 2009). The latter results, again, point to a possible involvement of tonic GABA signaling in neuritogenesis.

Cerebellum

GABA treatment triggers dendritic growth and arborization in dissociated cultures of developing cerebellar neurons (Baloyannis et al., 1983). Moreover, cultured cerebellar granule cells (CGCs) have been the focus of further studies demonstrating that GABA has a trophic neuritogenic effect. Indeed, when exposed to GABA for several days, developing CGCs extended significantly more neurites than when grown in control conditions (Hansen et al., 1984). Furthermore, this effect was accompanied by ultrastructural changes such as an increase in the density of cytoskeleton components (neurotubules). Notably, all these effects were not only counteracted, but even severely impaired by depleting the cells of the polyamines putrescine and spermidine (Abraham et al., 1993), indicating that the neuritogenic effects of GABA were linked to protein synthesis and mechanisms regulating cell proliferation. Moreover, the GABAergic effects on immature CGC dendritic proliferation appeared to be triggered by Ca2+ influx through the activation of L-type VDCCs, and they were prevented by Ca2+ channel blockers such as Mg2+ and nifedipine (Fiszman et al., 1999; Borodinsky et al., 2003). Finally, specific blockade of calcium-calmodulin kinase II (CaMKII) and of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2 (ERK1/2) also prevented the GABAergic effects on dendritic growth (Borodinsky et al., 2003), indicating the involvement of Ca2+ induced activation of various kinases during the differentiation of CGC dendrites (Borodinsky et al., 2003).

Different, and even opposite GABAergic effects on dendritic growth were reported in embryonic rat cerebellar and chick tectum cultures grown in different conditions (Michler, 1990). In serum-containing medium, GABA stimulated neurite growth. Conversely, GABA had the opposite effect in serum-free medium, and GABAA receptors agonists had the same effect (despite the fact that GABAA receptors are present in serum-free medium). At the same time, the GABAB receptor agonist baclofen inhibited neurite elongation in serum-free medium and had no effect in the presence of serum, suggesting that the different action of GABA in serum-free medium may be linked to GABAB receptor-mediated mechanisms. These studies underscore that one of the main drawbacks of using dissociated cultures is that it is difficult to replicate in vivo growth conditions, and that many of the apparent contradictions in in vitro studies may be overcome by in vivo experiments.

Retina

The effect of GABA on retinal dendritic growth has not been extensively studied in vitro. Spoerri (1988) reported that GABA had a positive effect on dendritic growth in retinal cultures. Like in CGCs in the cerebellum (Hansen et al., 1984), exposure to GABA led to an increase in microtubules density. Moreover, GABA and the GABAB receptor agonist baclofen both stimulate RGC neurite outgrowth in Xenopus cultures (Ferguson and McFarlane, 2002).

Olfactory bulb

The olfactory bulb is being widely used for studies on adult neurogenesis (see Effect of GABA on Neurite Extension During Adult Neurogenesis in this review), but few papers also reported GABAergic effects on dendritic growth in immature cultures.

Opposite GABAergic effects to those described in systems outlined in previous sections were reported in primary cultures of embryonic accessory olfactory bulb, where blockade (by bicuculline) rather than activation of GABAA receptors induces the formation of filopodia in non GABAergic, presumed mitral cells (Kato-Negishi et al., 2003). However, these same cells were quiescent in control conditions and they developed glutamate-mediated sustained Ca2+ oscillations in the presence of bicuculline, suggesting that GABA is actually hyperpolarizing in these cultures. Hence, in this case the neuritogenic effect of bicuculline is probably associated with GABAergic disinhinbition and consequently glutamatergic excitation rather than with direct GABAergic effects.

Astrocytes may provide a source of GABA while neurons extend dendrites and establish synaptic connections in cocultures of neurons and astrocytes from the neonatal olfactory bulb (Matsutani and Yamamoto, 1998). Indeed, dendritic branching is inhibited by GABAA antagonists (and tetrodotoxin) in neurons growing without contact with other neurons but only with astrocytes. The effect was reversed by growing the cultures in the presence of the GABAA agonist muscimol or by depolarizing the cells with elevated extracellular K+. However, when neurons were grown on a bed of dead astrocytes, all these effects were absent, demonstrating that astrocytes may exert a paracrine neuritogenic GABAergic effect on neurons growing in their vicinity.

Brain stem

GABAA activity seems to have differential effects on dendritic growth in different cell types in brainstem cultures (Liu et al., 1997). Indeed, GABA had positive neuritogenic effects on monoamine (serotonergic and noradrenergic) neurons whilst it had negative effects on GABAergic neurons in the same cultures. The results of this pharmacological study were explained by the authors as dependent on the precise composition of the subunits of the GABAA receptors in different cell subtypes, which may then influence the effect that GABA has on dendritic growth. There is, however, another possible explanation. Indeed, we note that GABA did not appear to be depolarizing in this system because it induced Cl− influx rather than efflux. Moreover, it is not possible to know whether all three cell types really had GABA-mediated Cl− influx because the results were presented for a mixed population of brainstem neurons. It may very well be that a more precise analysis of these responses in the three different cell types would reveal significant differences in the extent to which GABA causes hyperpolarization, and in some cases it may even induce membrane depolarization (and thus Ca2+ influx). So although the possibility that the precise composition of the subunits of the GABAA receptors may indeed influence the effect that GABA has on dendritic growth, it is important first to eliminate the possibility that GABA may exert different levels of depolarization in the three populations of cells. Such differences may explain why the monoamine neurons reacted positively to GABA in terms of dendritic growth whereas the effect on GABAergic neurons was the opposite.

Spinal cord

Similar to the earlier study by Michler (1990) in tectum and cerebellum, GABA had an inhibitory effect on dendritic proliferation in spinal cord cultures kept in heat inactivated-serum medium, and the effect was mimicked by the GABAB agonist baclofen (Bird and Owen, 1998). Here, however, although GABA did not significantly inhibit dendritic growth in serum-containing medium, no GABAA-mediated dendritic proliferation effects were observed. This is the only study that has not reported a GABAA-mediated neuritogenic effect. The reasons are not clear. One possibility is that serum inactivation by heat may have destroyed some essential components in the medium.

Another explanation is that glycine may be the predominant protagonist in the spinal cord during development, playing a role similar to what GABA does in other systems. Indeed, glycine is abundant in the spinal cord, and glycinergic receptors share many developmental similarities with GABAA receptors with respect to their Cl−-mediated depolarizing responses (Wu et al., 1992). One study on developing spinal cord cultures reported interplay between glycine and GABA in controlling neurite outgrowth (Tapia et al., 2001). In that study, at the time of intense neurite outgrowth (5-day-old cultures) both glycine and GABA induced depolarization and Ca2+ influx, and spontaneous synaptic events were predominantly glycinergic (although to a lesser extent also GABAergic). Neurite outgrowth in that system appeared to be promoted only when glycinergic neurotransmission was inhibited, because it was observed either at glycine concentrations that are high enough to desensitize glycine receptors or in the presence of the glycine receptor antagonist strychnine. Interestingly, opening of L-type Ca2+channels via GABAA receptor activation was necessary for the glycinergic effect. Tapia et al. (2001) suggested that the predominant glycinergic synaptic activity shunted neuronal excitability mediated by GABAA receptors, hence setting the intracellular Ca2+ concentration to suboptimal levels for neurite outgrowth. Glycine receptor desensitization or blockade may therefore relieve the system from its inhibitory state by increasing intracellular Ca2+ concentration to optimal levels.

Peripheral nervous system

In chick embryonic ciliary ganglion, cholinergic nicotinic activity induces the GABAergic switch from excitation to inhibition, and the effect is linked to KCC2 downregulation (Liu et al., 2006). Concomitantly, when KCC2 expression is forced prematurely in vitro, the depolarizing effect of GABA vanishes and neurons loose dendritic processes following prolonged exposure to GABA. Interestingly, these neurons also switched from being multipolar to becoming unipolar, as observed in vivo during normal development. If either GABA is omitted from the cultures or KCC2 activity is not induced, neurons remain multipolar. This confirms the neuritogenic role played by GABA while it is depolarizing.

In Vivo Studies

Despite a large body of data indicating a fundamental role for GABA in neurite outgrowth in vitro, in vivo evidence has been provided only in the last few years.

Hippocampus

The first hint came from a study by Groc et al. (2002, 2003), who investigated the role of early GABA and glutamate-driven network activity in the morphological differentiation of CA1 pyramidal cells (by means of neurobiotin filling of electrophysiologically recorded cells). This study reported a strong reduction in the frequency of spontaneous GABA and glutamatergic synaptic currents following injection of tetanus toxin into postnatal day 1 (P1) rat hippocampi. Moreover, consequent blockade of giant depolarizing potentials during the first postnatal week induced a threefold reduction in the total length of basal dendritic trees in pyramidal cells analyzed at the end of the first postnatal week. Interestingly, the apical dendrite, the axons, or the soma grew normally during activity deprivation.

Cortex

More direct evidence pointing towards a role for GABAA receptor in neurite outgrowth in vivo derived from studies performed in the cortex and retina. Indeed, prematurely shifting the GABA reversal potential to a more hyperpolarizing potential (by knockdown of NKCC1 or overexpression of KCC2) in utero resulted in fewer, shorter, and less branched dendrites (Cancedda et al., 2007; Wang and Kriegstein, 2008). The effect seemed to be dependent on the depolarizing action of GABA, as (1) it was mimicked by overexpression of the K+ inward rectifying channel Kir 2.1, which decreased cell excitability by lowering the resting membrane potential of the cell, and (2) it was absent when a mutated version of KCC2 (which was not able to pump Cl− ions) was transfected (Cancedda et al., 2007). Conversely, mice lacking the GABAA receptor α1 subunit, typical of synaptic GABA receptors, displayed dendritic arborization similar to wild type animals (Heinen et al., 2003), once again suggesting that tonic rather than phasic GABAergic transmission may be responsible for the neurogenic effects of GABA.

Retina

Intense RGC dendritic development occurs while the retina generates spontaneous waves (Sernagor et al., 2001). In turtle, peak RGC dendritic proliferation occurs 1 week before hatching (Mehta and Sernagor, 2006a,b), coinciding with the time depolarizing GABAA activity becomes involved in controlling the dynamics of the waves (Sernagor et al., 2003). Chronic exposure to bicuculline by means of the slow release polymer Elvax, inserted in the eye from the time GABA starts to modulate retinal waves, resulted in a significant loss of RGC dendritic branches without affecting the overall coverage of dendritic arbors (F. Chabrol and E. Sernagor, unpublished observations). At the same time, chronic GABAergic depletion (by blockade of GABA synthesis) caused severe arbor shrinkage, but dendrites also exhibited numerous very small dendritic branches covering the entire dendritic tree (F. Chabrol and E. Sernagor, unpublished observation). These observations suggest that as in other systems, GABA has a positive neuritogenic effect on dendritic growth. The appearance of numerous small branches covering the entire tree in GABA-depleted retinas demonstrates that like in the olfactory bulb (Gascon et al., 2006; see Effect of GABA on Neurite Extension During Adult Neurogenesis), GABA has a stabilizing effect on dendritic proliferation.

GABAergic inhibition and dendritic growth

All the studies reported so far have pointed to a possible role for depolarizing GABA in neurite development. A recent paper has addressed the role of GABAergic inhibition on neuronal morphological maturation in Xenopus tadpole in vivo (Shen et al., 2009). In this paper, authors tested whether inhibitory GABAergic synaptic transmission regulates dendritic arbor development in the Xenopus optic tectum by expressing a peptide corresponding to an intracellular loop (ICL) of the γ2 subunit of GABAA receptor in vivo. This peptide completely blocked GABAA-mediated transmission in one third of transfected neurons, and significantly reduced GABAA-mediated synaptic currents in the remaining transfected cells. In vivo time-lapse imaging showed that ICL expressing neurons had more sparsely branched dendritic arbors, which nevertheless expanded over larger neuropil areas than in control neurons. Furthermore, analysis of branch dynamics indicated that ICL expression affected arbor growth by reducing rates of branch addition. These intriguing results share common points with the retina, where chronic blockade of GABAA receptors with bicuculline yield less branched RGC dendritic trees (see previous section). However, in the retina, GABA remained at least partially excitatory in these conditions (Leitch et al., 2005), whereas here GABA appears to be inhibitory, suggesting that GABAergic inhibition normally promotes dendritic growth. One possibility is that extrasynaptic, tonic GABA activity is unaffected because only the γ2 subunit of the GABAA receptor is impaired, that subunit being mostly specifically associated with synaptic receptors (Farrant and Nusser, 2005). As many examples demonstrate in literature, extrasynaptic GABAergic activity may play important trophic roles, including neuritogenesis. So, in the present case, perhaps extrasynaptic GABAergic signaling is less impaired than assumed. The effects reported on dendritic growth may arise from complex interactions between paracrine GABAergic activity and partially disinhibited glutamatergic synaptic activity.

Effect of GABA on Axonal Elongation

If on one hand GABA action through GABAA receptors appears to be a key player in dendritic development, does GABAergic signaling also affect axonal morphological maturation? Recently gathered evidence indicates that this may indeed be the case.

In 2007, Chattopadhyaya et al. demonstrated in organotypic cortical slices that endogenous GABA levels regulate cortical basket-cell axonal branching through the activation of GABAA, and to lesser extent GABAB receptors during the maturation of inhibitory circuits (Chattopadhyaya et al., 2007). Nevertheless, it is worth noting that this study was performed in the adolescent brain, when GABA is inhibitory (Chattopadhyaya et al., 2007). Furthermore, reversing the Cl− gradient in vivo, from the onset of development, by global KCC2 overexpression in newly fertilized zebrafish embryos reduced the elaboration of axonal tracts (Reynolds et al., 2008).

The effect of GABA on axonal growth may be specifically mediated by the α2 subunit of the GABAA receptor, as a α2(but not α5) selective agonist strongly reduced axonal sprouting in cell cultures of hamster hippocampal neurons (Giusi et al., 2009). Furthermore, a new study has recently addressed specifically whether GABA signaling may affect axonal morphological maturation both in vitro and in vivo (Ageta-Ishihara et al., 2009). This study has reported that GABA-mediated increase in intracellular Ca2+ via CaMKs influenced axon elongation in cortical neuronal cultures. In particular, two separate branches of the CaMK family, namely CaMKK-CaMK1α and CaMKK-CaMKIγ, respectively guided axonal and dendritic elongation. Indeed, the GABAA agonist muscimol promoted Ca2+ influx and axonal elongation, and this GABAergic axogenic effect was mediated through the CaMKK-CaMKIα cascade. These in vitro effects were confirmed in vivo, where knockdown of CaMKIα severely impaired the elongation of callosal axonal projections in the somatosensory cortex. Furthermore, GABAA receptors blockade with bicuculline had an inhibitory effect on axonal elongation, confirming that endogenous GABA was necessary for axonal growth. Finally, lowering the intracellular Cl− concentration by forced expression of KCC2 abolished the muscimol-induced effect, which corroborated the idea that the effect was mediated through membrane depolarization and Ca2+ influx. However, very surprisingly, and in contradiction with previous studies, muscimol did not promote dendritic growth in this study. On the other hand, BDNF specifically induced dendritic growth via the CaMKK-CaMKIγ pathway in the same cultures (Takemoto-Kimura et al., 2007). Interestingly, Ageta-Ishihara et al. (2009) also reported that premature elimination of the excitatory GABA drive by forced expression of KCC2 or NKCC1 downregulation in vivo dramatically perturbed the morphological maturation of terminal callosal axonal branches. (H. Mizuno, T. Hirano, and Y. Tagawa, unpublished observation).

Effect of GABA on Neurite Extension During Adult Neurogenesis

Neurogenesis in the adult brain is a process that occurs throughout life in the mammalian hippocampus and olfactory bulb under physiological conditions (Ma et al., 2009). Adult neurogenesis recapitulates the complete process of neuronal development in a mature CNS environment (e.g. proliferation of neural progenitors, migration and differentiation of neuroblasts, and synaptic integration of newborn neurons). Interestingly, depolarizing GABA, as in the embryonic nervous system, has emerged as a key player in multiple steps of adult neurogenesis. In particular, in vivo and in vitro studies demonstrated a role for GABA receptor signaling in neuritogenesis of newborn neurons both in the hippocampus and in the olfactory bulb (Ge et al., 2007).

Hippocampus

Conversion of GABA-induced depolarization into hyperpolarization in newborn neurons in adult hippocampus leads to marked defects on dendritic development in vivo (Ge et al., 2006). Indeed, downregulation of the NKCC1 cotransporter by viral injection reduced the total dendritic length and branch number, as well as dendritic complexity in newborn neurons. In addition, injection of the GABAA receptor agonist pentobarbital promoted dendrite growth of newborn neurons in vivo (Ge et al., 2006). Interestingly, seizure induction, which increases the local hippocampal ambient GABA levels (Ueda and Tsuru, 1995; Patrylo et al., 2001; Cossart et al., 2005; Naylor et al., 2005), greatly accelerated dendritic development of newborn granule cells in adult mice (Overstreet-Wadiche et al., 2006). It is possible that this GABA-induced effect on neurite outgrowth depends on Ca2+ elevation since, as in neonatal development, GABA depolarization increases the intracellular Ca2+ concentration in newborn neurons (Tozuka et al., 2005; Goffin et al., 2008). Moreover, GABA-mediated depolarization was also involved in the phosphorylation of CREB during the first 2 weeks of development in vivo (Jagasia et al., 2009), and CREB phosphorylation in turn promoted dendritic development (Jagasia et al., 2009). Importantly, developmental defects after the loss of GABA-mediated excitation (by NKCC1 knockdown) could be compensated by enhancement of CREB signaling (Jagasia et al., 2009), indicating that the CREB pathway may influence neuritogenesis downstream of GABA-mediated excitation. Furthermore, CREB signaling may eventually converge onto BDNF pathway for the dendritogenic effect, as dendrite branching, length and complexity was seriously affected in mice with postnatal depletion of BDNF (Chan et al., 2008).

Olfactory bulb

Newly generated cells in the subventricular zone (SVZ) of the lateral ventricle migrate to the olfactory bulb trough the rostral migratory stream in adult mammals. GABA mediates the first extrasynaptic responses in these migrating SVZ cells, and at that time, like in immature systems, GABA is depolarizing and opens L-type Ca2+ channels (Carleton et al., 2003; Gascon et al., 2006). Ambient GABA appears to induce dendritic proliferation both in dissociated cultures of neonatal SVZ cells and in olfactory bulb slices. This effect was mediated via activation of GABAA receptors because when the cultures or slices were incubated in the presence of the GABAA antagonist bicuculline, dendritic growth was severely disrupted (mostly by reducing the number and length of primary dendrites), yielding dendritic arbors with much less complexity (Gascon et al., 2006). This effect was pronounced only on newly generated cells but not on older ones. GABA also caused growth cones to become larger. This early effect is not due to changes in growth cones dynamics (formation and retraction of lamellipodia), but rather to an increase in their lifetime and even in their numbers. GABA had a similar stabilizing effect on newly formed dendrites, while bicuculline increased the frequency of dendritic retraction phases. These neuritogenic GABAergic effects were correlated with the stabilization of microtubules (assayed by measuring the amount of polymerized versus non-polymerized tubulin) in newly formed dendrites. This whole chain of events necessitated Ca2+ influx triggered by GABAergic depolarization, because the neuritogenic effects of GABA were abolished when transient increases in intracellular Ca2+ were prevented. Interestingly, GABAB receptor-mediated signaling did not seem to be important for the effect, as the authors found that in dissociated cultures from SVZ-derived neurons of newborn rats, treatment with the GABAB antagonist CGP54626 resulted in no changes in dendritic arbors and lamellipodia dynamics (Gascon et al., 2006). Conversely, CREB phosphorylation may be important for GABA-dependent neuritogenesis, as (1) although CREB is expressed by the SVZ neuroblasts throughout the neurogenic process, its phosphorylation is transient and parallels neuronal differentiation, increasing in cells entering the olfactory bulb and decreasing after dendrite elongation; (2) inhibitors of different protein kinases involved in CREB phosphorylation in the context of neuronal differentiation block morphological development of SVZ-derived neuroblasts in primary cultures (Giachino et al., 2005).

Discussion and Concluding Remarks

This review has gathered evidence for a prominent GABAergic role during neurite growth both in the developing CNS and during adult neurogenesis. Remarkably, the same rules appear to apply to ontogeny and adult neurogenesis, demonstrating universal regulation mechanisms. Type-A GABA activity is the main protagonist, and in a general scheme, it promotes neurite growth through membrane depolarization, Ca2+ influx and downstream intracellular effects.

GABAB receptors may also play a role in neurite outgrowth in some brain areas (but not others; see Fiorentino et al., 2009), but the effects appear to be mediated through fundamentally different metabotropic mechanisms, which do not directly involve changes in membrane potential (e.g., Michler, 1990; Lopez-Bendito et al., 2003). Moreover, no GABAB effects were reported during neurogenesis in the olfactory bulb (Gascon et al., 2006). Hence, GABAB-mediated effects on neurite growth may be fundamentally different in diverse brain areas and during development vs adult neurogenesis.

Tonic versus phasic GABA activity

The neuritogenic effects of GABAA activity appear at very early stages, long before synapse formation (Represa and Ben-Ari, 2005). Several lines of evidence suggest that these effects are mediated by ambient GABA released paracrinally from maturing neurons or from glial cells (Matsutani and Yamamoto, 1998). In the neonatal rat retina, for example, diffuse subunit staining (characteristic of extrasynaptic receptors) for various GABAA receptor subunits precedes the punctate staining pattern (characteristic of synaptic receptors) by a couple of days (Koulen, 1999).

An indication that this tonic GABAergic release may occur at extrasynaptic sites is the fact that it involves GABAA receptors that do not express subunits normally constituting synaptic receptors. More specifically, the γ2 subunit, which is necessary for clustering of postsynaptic GABAA receptors, is not highly expressed at extrasynaptic sites at early developmental stages. One study on the development of dendritic arbors in Xenopus optic tectum reported that synaptic GABAergic inhibition promotes dendritic growth (Shen et al., 2009). In that study, however, synaptic γ2 subunits were specifically impaired, but it is not clear whether tonic release from non-synaptic sites was affected at all, and therefore it is difficult to interpret the results. Finally, knockout of the synaptic α1 subunit had no effect on dendritic growth in the developing visual cortex (Heinen et al., 2003), although it did affect inhibitory activity (Bosman et al., 2002), pointing towards a more prominent role for tonic GABAergic release.

Although in most cases GABA (or GABAA agonists) were reported to have a direct neuritogenic effect, some in vitro studies mentioned that agonists had little or no effect on neurite growth, even though the antagonist bicuculline had a significant inhibitory effect (Barbin et al., 1993; Liu et al., 1997). This suggests that ambient, tonic GABAergic activity plays an important role in promoting neurite growth. It is obvious that there is more ambient GABA in intact tissue, and therefore, in that respect, in vitro acute-slice studies and in vivo reports provide a more direct evidence for a neuritogenic role for paracrine GABA activity than cell cultures studies. In support, tonic GABA currents were recorded in acute slices at ages at which forced expression of KCC2 or downregulation of NKCC1 affected neuritogenesis in newborn neurons both during development and in the adult animal, respectively (Ge et al., 2006; Cancedda et al., 2007). Moreover, chronic GABA-synthesis blockade in the developing retina resulted in severe RGC dendritic tree shrinkage and prevented the stabilization of end-branches in vivo (F. Chabrol and E. Sernagor, unpublished observation).

GABAergic depolarization or hyperpolarization?

All studies reviewed here unanimously state that the neuritogenic effect of GABAA signaling is mediated by membrane depolarization (LoTurco et al., 1995; Ben-Ari et al., 2007; Ge et al., 2007; Wang and Kriegstein, 2009), which is generated via Cl− efflux upon GABAAreceptors activation. This Cl− outflow originates from a reverse Cl− gradient. The intracellular Cl− concentration is indeed higher in immature neurons because of low expression of the KCC2 Cl− extruding pump (Rivera et al., 1999) and/or high expression of NKCC1 that pumps Cl− into neurons (Blaesse et al., 2009).

The mere depolarizing action of GABA rather than the GABAergic nature of the depolarization seems to be the major driving force for the neuritogenic effect. Indeed, when GABAergic activity is abolished by GABA synthesis blockade, neurite growth can be rescued by direct depolarization (with high K+) or by triggering downstream effects such as Ca2+ influx (Maric et al., 2001; see next section). Moreover, overexpression of the K+ inward rectifying Kir 2.1 channel, which strongly decreases membrane excitability in vivo prevents membrane depolarization in newborn neurons, mimicking GABA deprivation in these young cells and leading to inhibition of neurite outgrowth (Cancedda et al., 2007). Direct interference with KCC2 or NKCC1 functionality also triggers changes in neurite growth (Maric et al., 2001; Ge et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2006; Cancedda et al., 2007; Wang and Kriegstein, 2008), demonstrating that it is the depolarizing driving force established by the reverse Cl− gradient that is at work here. Moreover, once GABA has switched to its mature inhibitory role, it can no longer induce neurite growth (Marty et al., 1996; Gascon et al., 2006).

In the few cases where GABA inhibited neurite growth, either direct (Kato-Negishi et al., 2003) or indirect (Liu et al., 1997) evidence demonstrates that the effect was due to hyperpolarizing GABAergic signaling. One study reported that GABAergic inhibition promoted dendritic growth in the Xenopus optic tectum (Shen et al., 2009). However, although this study clearly demonstrates that GABAergic synaptic signaling is hyperpolarizing, it is not clear whether the reduction in dendritic proliferation is indeed due to reduced GABAergic inhibition (because of impairment of the γ2 subunit of the GABAA receptor), as the study provides no evidence for what happens at non-synaptic sites.

Downstream effects of GABAA signaling on neurite growth

How does GABA depolarization influence morphological maturation of newborn neurons? Increase in intracellular Ca2+ due to activation of VDCCs is likely to have a significant role. Indeed, activation of VDCCs mediates GABA-induced promotion of neurite growth in various brain regions, as reported above (Fiszman et al., 1999; Maric et al., 2001; Tapia et al., 2001; Borodinsky et al., 2003; Gascon et al., 2006). Interestingly, all these studies reported that high threshold L-type VDCCs were responsible for the depolarizing GABAergic effect on neurite outgrowth. Nevertheless, as discussed earlier, tonic-GABA signaling appears particularly important for the effect, but only synaptic depolarization seems to be able to reach membrane depolarization levels high enough to activate high-threshold Ca2+ channels. One possibility is that in the very first phase of neuritogenesis, when synapses are not yet formed, small changes in the membrane potential (Wang et al., 2003; Ge et al., 2006) resulting from the activation of low affinity non-synaptic GABAergic receptors may open low threshold VDCCs (typically below −57 mV, which is close to the resting membrane potential of immature neurons (Schmidt-Hieber et al., 2004; Ge et al., 2006; Cancedda et al., 2007). Interestingly, the expression of low-threshold T-channels precedes other VDCCs in embryonic hippocampal, sensory and motor neurons (for review see Lory et al., 2006) and in newborn neurons in the dentate gyrus (Schmidt-Hieber et al., 2004), while these cells extend axons and dendrites. Once phasic synaptic GABAergic inputs are established, the depolarization induced by synaptically released GABA could cause sufficient membrane depolarization to activate L-type VDCCs. Therefore, the studies indicating high threshold L-type VDCCs as mediators of the neuritogenic GABA effects were probably undertaken after the onset or completion of synaptogenesis. Specific experiments aimed at investigating neuritogenesis (with application of T-type Ca2+ channel blockers) before synapse formation may help to resolve the issue.

Besides directly activating L-type VDCCs, phasic GABA-mediated activation can lead to Ca2+ influx by facilitating the opening of NMDA-receptor channels in response to glutamate (Deschenes et al., 1976; Leinekugel et al., 1997; Owens and Kriegstein, 2002; Ben-Ari, 2006; Wang and Kriegstein, 2008), a role taken over by AMPA receptors later in development (Ben-Ari et al., 1997). Indeed, NMDA receptors are functionally silent at negative membrane potentials due to blockade of the channel by Mg2+ (Demarque et al., 2004). Nevertheless, there are some indications that the voltage-dependent Mg2+ blockade is less efficient in neonatal neurons than in adults (Ben-Ari et al., 1988; Bowe and Nadler, 1990; Kleckner and Dingledine, 1991; Takahashi et al., 1996; Hsiao et al., 2002; but see Khazipov et al., 1995). Interestingly, NMDA (but not AMPA) receptors, can specifically influence initial dendritic arbor growth (Rajan and Cline, 1998), indicating that GABA depolarization may also exert its role on neuritogenesis trough activation of otherwise silent NMDA receptors before AMPAergic transmission takes over. Later, when AMPAergic transmission becomes more prominent, it could act in synergy with GABAergic and NMDA signaling to promote a later phase of neuritogenesis (Ben-Ari et al., 1997), by contributing to removal of the Mg2+ block and direct Ca influx, which is enhanced during early developmet in various systems (Otis et al., 1995; Ben-Ari et al., 1997; Gleason and Spitzer, 1998; Ravindranathan et al., 2000; Eybalin et al., 2004; Ni et al., 2007). This hypothesis is favored by the fact that (1) at later developmental stages, both NMDA and AMPA receptors are necessary to enable the completion of neurite development in various systems (Rajan and Cline, 1998; Sin et al., 2002; Haas et al., 2006); (2) AMPAergic transmission is impaired in neurons with downregulation of NKCC1, and these neurons have poorly developed dendrites (Ge et al., 2006; Wang and Kriegstein, 2008).

Interestingly, BDNF may be a downstream effector of depolarizing GABA effect on neurite outgrowth. This is based on two pieces of evidence. (1) BDNF expression and release from target neurons depends on GABAergic depolarization in the first 2 weeks in vitro, whereas GABAergic activity reduces the synthesis of BDNF mRNA in mature neurons (Berninger et al., 1995; Marty et al., 1996; Vicario-Abejon et al., 1998; Giusi et al., 2009). (2) BDNF signaling deprivation leads to dendrite growth impairment in newborn neurons during development and in the adult (McAllister et al., 1996; Berghuis et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2006; Takemoto-Kimura et al., 2007; Bergami et al., 2008; Chan et al., 2008; Ageta-Ishihara et al., 2009; Suh et al., 2009). Interestingly, GABAB receptor can also modulate the production and release of BDNF in an opposite fashion in newborn vs adult neurons (Heese et al., 2000; Ghorbel et al., 2005; Enna et al., 2006; Fiorentino et al., 2009). Despite those indications, however, a direct demonstration that the depolarizing effect of GABA on neurite development depends on BDNF is still missing.

Finally, Ca2+ influx may activate downstream effectors relevant to neuritogenesis both acutely through cytoskeleton rearrangement or long-term by activation of kinases and transcriptional programs (e.g., CaMKII, ERK1/2, CREB; Berninger et al., 1995; Owens et al., 1996; Borodinsky et al., 2003; Fiszman and Schousboe, 2004; Ageta-Ishihara et al., 2009; Jagasia et al., 2009).

Experimental approaches

Most studies reported in this review have used in vitro pharmacological approaches. The rationale for using such strategy is obvious, as it enables relatively easy manipulation of various components of the chain of factors that influence the way GABA exerts its effects (e.g. blockade of specific receptor subunits or binding site, Cl− pumps, Ca2+ channels etc..), and the results reported in these in vitro studies have greatly contributed to our understanding of the mechanisms by which GABA influences neurite outgrowth. Nevertheless, it is still important to address similar questions in vivo, where systems are intact and exposed to their natural environment.

In order to interfere with the GABAergic system in vivo, either genetically manipulated animals or local pharmacological manipulations must be used. The problem with classic genetic approaches is that animals carrying null mutations for important genes involved in GABAergic signaling either die at birth, and if not, they often carry only mild phenotypes into adulthood (perhaps because of functional compensation by other systems (see Owens and Kriegstein, 2002) for an interesting discussion on these issues). Intriguingly, few studies have used classic genetic approaches to investigate how GABA may exert its influence on neurite growth and the reason may well be that many of these models are not inspiring because no obvious phenotype is present in adulthood. Nevertheless, it may well be that more detailed investigation of specific parameters such as dendritic morphometry might reveal important issues in some of these animals. All the same, Heinen et al. (2003) have successfully shown that knockout of the α1 subunit of the GABAA receptor has no impact on dendritic growth, despite the fact that inhibitory synaptic transmission is impaired in these animals (Bosman et al., 2002). This finding is extremely valuable for our understanding of the tonic versus phasic role played by GABA during neurite outgrowth. Recently, in utero electroporation and specific viral infection of newborn neurons in the dentate gyrus have allowed gene expression/knockdown of specific subpopulation of neurons in a time and location restricted fashion, partly avoiding the compensatory mechanisms probably at work in classic genetically modified animals. These new genetic approaches have been successfully used to impair the Cl− homeostatic control system or to increase K+ conductance to reduce cell excitability in the rodent brain in vivo (Ge et al., 2006; Cancedda et al., 2007; Wang and Kriegstein, 2008). Furthermore, Shen et al. (2009) have successfully applied a similar approach to alter the composition of GABAA receptors in the developing Xenopus optic tectum.

Finally, in vivo pharmacological interventions can also contribute to our understanding of the role played by GABA during neurite development. In vivo pharmacology is particularly easy in the retina because it is encased in the eye and it is more readily accessible. In ovo pharmacological manipulations have been particularly successful in turtle embryos where the eye can easily be exposed by opening the egg shell while the embryo develops (Leitch et al., 2005).

Conclusions

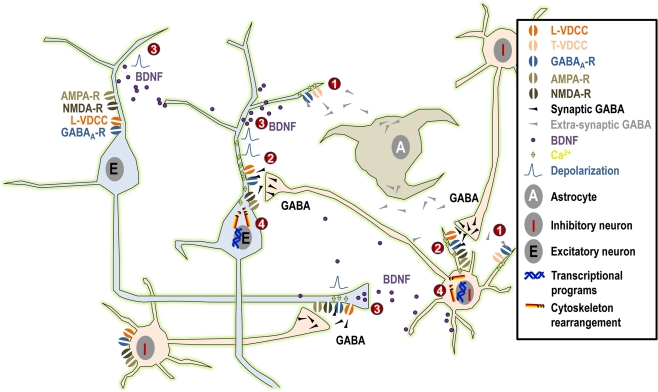

By triggering a chain of events, GABA appears to exert profound effects on neurite outgrowth in immature neurons during embryonic development and in adult neurogenesis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Summary of the possible mechanisms linking GABAA activity and neurite outgrowth. (1) Under normal physiological conditions, tonic GABAergic release from maturing neurons and/or from astrocytes induces small tonic depolarization that may be sufficient to activate low-threshold T-type VDCCs and to promote the initial phase of neurite growth. (2) Subsequently, when synaptic GABA acts in synergy first exclusively with NMDA receptors and at later stages both with AMPA and NMDA receptors, this will result in larger depolarization that may even reach firing threshold. Such larger depolarizing signals may activate high-threshold L-type VDCCs and, together with direct Ca2+ influx through NMDA and AMPA receptors, they may contribute to the maturation of neuronal morphology. (3) Moreover, GABAergic activity together with NMDA and AMPA receptor signaling (possibly through Ca2+ signaling) may influence synthesis and activity-dependent release of BDNF, again influencing dentritic growth. (4) Finally, Ca2+ influx may activate downstream effectors relevant to neuritogenesis both acutely through cytoskeleton rearrangement or long-term by activation of kinases and transcriptional programs.

Long before synapse formation, tonic GABA binds to low affinity extrasynaptic GABAA receptors and it triggers membrane depolarization through Cl− efflux (the intracellular concentration of Cl− being higher than in mature cells because of low expression of the KCC2 pump and high expression of the NKCC1 pump). This, in turn, opens low threshold T-type Ca2+ channels, resulting in Ca2+ influx and intracellular events that will eventually lead to neurite extension. At later maturational stages, when glutamatergic signaling has developed, GABA may act in concert with NMDA and AMPA neurotransmission, resulting in stronger depolarization and the opening of high-threshold L-type Ca2+ channels. This will result in stronger Ca2+ influx, which may be important for triggering downstream intracellular events that are responsible for the late phases of neurite growth. This process will come to an end when synaptic inhibition matures (through changes in the composition of the GABAA receptor subunits and reversal of the Cl− gradient), leaving the possibility for plastic remodeling of the existing neuritic network by the dynamic balance of neuronal activity resulting from hyperpolarizing GABA and fully developed glutamatergic signaling.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Abraham J. H., Hansen G. H., Seiler N., Schousboe A. (1993). Depletion of polyamines prevents the neurotrophic activity of the GABA-agonist THIP in cultured rat cerebellar granule cells. Neurochem. Res. 18, 153–158 10.1007/BF01474678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ageta-Ishihara N., Takemoto-Kimura S., Nonaka M., Adachi-Morishima A., Suzuki K., Kamijo S., Fujii H., Mano T., Blaeser F., Chatila T. A., Mizuno H., Hirano T., Tagawa Y., Okuno H., Bito H. (2009). Control of cortical axon elongation by a GABA-driven Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase cascade. J. Neurosci. 29, 13720–13729 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3018-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baloyannis S. J., Karakatsanis K., Karathanasis J., Apostolakis M., Diacoyannis A. (1983). Effects of GABA, glycine, and sodium barbiturate on dendritic growth in vitro. Acta Neuropathol. 59, 171–182 10.1007/BF00703201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbin G., Pollard H., Gaiarsa J. L., Ben-Ari Y. (1993). Involvement of GABAA receptors in the outgrowth of cultured hippocampal neurons. Neurosci. Lett. 152, 150–154 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90505-F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y. (2002). Excitatory actions of gaba during development: the nature of the nurture. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3, 728–739 10.1038/nrn920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y. (2006). Basic developmental rules and their implications for epilepsy in the immature brain. Epileptic Disord. 8, 91–102 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y., Cherubini E., Corradetti R., Gaiarsa J. L. (1989). Giant synaptic potentials in immature rat CA3 hippocampal neurones. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 416, 303–325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y., Cherubini E., Krnjevic K. (1988). Changes in voltage dependence of NMDA currents during development. Neurosci. Lett. 94, 88–92 10.1016/0304-3940(88)90275-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y., Gaiarsa J. L., Tyzio R., Khazipov R. (2007). GABA: a pioneer transmitter that excites immature neurons and generates primitive oscillations. Physiol. Rev. 87, 1215–1284 10.1152/physrev.00017.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y., Khazipov R., Leinekugel X., Caillard O., Gaiarsa J. L. (1997). GABAA, NMDA and AMPA receptors: a developmentally regulated ‘menage a trois’. Trends Neurosci. 20, 523–529 10.1016/S0166-2236(97)01147-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y., Tseeb V., Raggozzino D., Khazipov R., Gaiarsa J. L. (1994). gamma-Aminobutyric acid (GABA): a fast excitatory transmitter which may regulate the development of hippocampal neurones in early postnatal life. Prog. Brain Res. 102, 261–273 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)60545-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergami M., Rimondini R., Santi S., Blum R., Gotz M., Canossa M. (2008). Deletion of TrkB in adult progenitors alters newborn neuron integration into hippocampal circuits and increases anxiety-like behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 15570–15575 10.1073/pnas.0803702105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berghuis P., Agerman K., Dobszay M. B., Minichiello L., Harkany T., Ernfors P. (2006). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor selectively regulates dendritogenesis of parvalbumin-containing interneurons in the main olfactory bulb through the PLCgamma pathway. J. Neurobiol. 66, 1437–1451 10.1002/neu.20319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berninger B., Marty S., Zafra F., da Penha Berzaghi M., Thoenen H., Lindholm D. (1995). GABAergic stimulation switches from enhancing to repressing BDNF expression in rat hippocampal neurons during maturation in vitro. Development 121, 2327–2335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird M., Owen A. (1998). Neurite outgrowth-regulating properties of GABA and the effect of serum on mouse spinal cord neurons in culture. J. Anat. 193(Pt 4), 503–508 10.1046/j.1469-7580.1998.19340503.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaesse P., Airaksinen M. S., Rivera C., Kaila K. (2009). Cation-chloride cotransporters and neuronal function. Neuron 61, 820–838 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordey A. (2007). Enigmatic GABAergic networks in adult neurogenic zones. Brain Res. Rev. 53, 124–134 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2006.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borodinsky L. N., O'Leary D., Neale J. H., Vicini S., Coso O. A., Fiszman M. L. (2003). GABA-induced neurite outgrowth of cerebellar granule cells is mediated by GABA(A) receptor activation, calcium influx and CaMKII and erk1/2 pathways. J. Neurochem. 84, 1411–1420 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01638.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosman L. W., Rosahl T. W., Brussaard A. B. (2002). Neonatal development of the rat visual cortex: synaptic function of GABAA receptor alpha subunits. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 545, 169–181 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.026534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowe M. A., Nadler J. V. (1990). Developmental increase in the sensitivity to magnesium of NMDA receptors on CA1 hippocampal pyramidal cells. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 56, 55–61 10.1016/0165-3806(90)90164-T [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancedda L., Fiumelli H., Chen K., Poo M. M. (2007). Excitatory GABA action is essential for morphological maturation of cortical neurons in vivo. J. Neurosci. 27, 5224–5235 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5169-06.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carleton A., Petreanu L. T., Lansford R., Alvarez-Buylla A., Lledo P. M. (2003). Becoming a new neuron in the adult olfactory bulb. Nat. Neurosci. 6, 507–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J. P., Cordeira J., Calderon G. A., Iyer L. K., Rios M. (2008). Depletion of central BDNF in mice impedes terminal differentiation of new granule neurons in the adult hippocampus. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 39, 372–383 10.1016/j.mcn.2008.07.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyaya B., Di Cristo G., Wu C. Z., Knott G., Kuhlman S., Fu Y., Palmiter R. D., Huang Z. J. (2007). GAD67-mediated GABA synthesis and signaling regulate inhibitory synaptic innervation in the visual cortex. Neuron 54, 889–903 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.05.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z. Y., Jing D., Bath K. G., Ieraci A., Khan T., Siao C. J., Herrera D. G., Toth M., Yang C., McEwen B. S., Hempstead B. L., Lee F. S. (2006). Genetic variant BDNF (Val66Met) polymorphism alters anxiety-related behavior. Science 314, 140–143 10.1126/science.1129663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobas A., Fairen A., Alvarez-Bolado G., Sanchez M. P. (1991). Prenatal development of the intrinsic neurons of the rat neocortex: a comparative study of the distribution of GABA-immunoreactive cells and the GABAA receptor. Neuroscience 40, 375–397 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90127-A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cossart R., Bernard C., Ben-Ari Y. (2005). Multiple facets of GABAergic neurons and synapses: multiple fates of GABA signalling in epilepsies. Trends Neurosci. 28, 108–115 10.1016/j.tins.2004.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demarque M., Villeneuve N., Manent J. B., Becq H., Represa A., Ben-Ari Y., Aniksztejn L. (2004). Glutamate transporters prevent the generation of seizures in the developing rat neocortex. J. Neurosci. 24, 3289–3294 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5338-03.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschenes M., Feltz P., Lamour Y. (1976). A model for an estimate in vivo of the ionic basis of presynaptic inhibition: an intracellular analysis of the GABA-induced depolarization in rat dorsal root ganglia. Brain Res. 118, 486–493 10.1016/0006-8993(76)90318-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eins S., Spoerri P. E., Heyder E. (1983). GABA or sodium-bromide-induced plasticity of neurites of mouse neuroblastoma cells in culture. A quantitative study. Cell Tissue Res. 229, 457–460 10.1007/BF00214987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enna S. J., Reisman S. A., Stanford J. A. (2006). CGP 56999A, a GABA(B) receptor antagonist, enhances expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and attenuates dopamine depletion in the rat corpus striatum following a 6-hydroxydopamine lesion of the nigrostriatal pathway. Neurosci. Lett. 406, 102–106 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essrich C., Lorez M., Benson J. A., Fritschy J. M., Luscher B. (1998). Postsynaptic clustering of major GABAA receptor subtypes requires the gamma 2 subunit and gephyrin. Nat. Neurosci. 1, 563–571 10.1038/2798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eybalin M., Caicedo A., Renard N., Ruel J., Puel J. L. (2004). Transient Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors in postnatal rat primary auditory neurons. Eur. J. Neurosci. 20, 2981–2989 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03772.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrant M., Nusser Z. (2005). Variations on an inhibitory theme: phasic and tonic activation of GABA(A) receptors. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6, 215–229 10.1038/nrn1625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson S. C., McFarlane S. (2002). GABA and development of the Xenopus optic projection. J. Neurobiol. 51, 272–284 10.1002/neu.10061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorentino H., Kuczewski N., Diabira D., Ferrand N., Pangalos M. N., Porcher C., Gaiarsa J. L. (2009). GABA(B) receptor activation triggers BDNF release and promotes the maturation of GABAergic synapses. J. Neurosci. 29, 11650–11661 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3587-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiszman M. L., Borodinsky L. N., Neale J. H. (1999). GABA induces proliferation of immature cerebellar granule cells grown in vitro. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 115, 1–8 10.1016/S0165-3806(99)00035-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiszman M. L., Schousboe A. (2004). Role of calcium and kinases on the neurotrophic effect induced by gamma-aminobutyric acid. J. Neurosci. Res. 76, 435–441 10.1002/jnr.20062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly K., Schinder A. F., Wong S. T., Poo M. (2001). GABA itself promotes the developmental switch of neuronal GABAergic responses from excitation to inhibition. Cell 105, 521–532 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00341-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gascon E., Dayer A. G., Sauvain M. O., Potter G., Jenny B., De Roo M., Zgraggen E., Demaurex N., Muller D., Kiss J. Z. (2006). GABA regulates dendritic growth by stabilizing lamellipodia in newly generated interneurons of the olfactory bulb. J. Neurosci. 26, 12956–12966 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4508-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge S., Goh E. L., Sailor K. A., Kitabatake Y., Ming G. L., Song H. (2006). GABA regulates synaptic integration of newly generated neurons in the adult brain. Nature 439, 589–593 10.1038/nature04404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge S., Pradhan D. A., Ming G. L., Song H. (2007). GABA sets the tempo for activity-dependent adult neurogenesis. Trends Neurosci. 30, 1–8 10.1016/j.tins.2006.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghorbel M. T., Becker K. G., Henley J. M. (2005). Profile of changes in gene expression in cultured hippocampal neurones evoked by the GABAB receptor agonist baclofen. Physiol. Genomics 22, 93–98 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00202.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giachino C., De Marchis S., Giampietro C., Parlato R., Perroteau I., Schutz G., Fasolo A., Peretto P. (2005). cAMP response element-binding protein regulates differentiation and survival of newborn neurons in the olfactory bulb. J. Neurosci. 25, 10105–10118 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3512-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giusi G., Facciolo R. M., Rende M., Alo R., Di Vito A., Salerno S., Morelli S., De Bartolo L., Drioli E., Canonaco M. (2009). Distinct alpha subunits of the GABA(A) receptor are responsible for early hippocampal silent neuron-related activities. Hippocampus 19, 1103–1114 10.1002/hipo.20584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleason E. L., Spitzer N. C. (1998). AMPA and NMDA receptors expressed by differentiating Xenopus spinal neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 79, 2986–2998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffin D., Aarum J., Schroeder J. E., Jovanovic J. N., Chuang T. T. (2008). D1-like dopamine receptors regulate GABAA receptor function to modulate hippocampal neural progenitor cell proliferation. J. Neurochem. 107, 964–975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groc L., Gustafsson B., Hanse E. (2003). In vivo evidence for an activity-independent maturation of AMPA/NMDA signaling in the developing hippocampus. Neuroscience 121, 65–72 10.1016/S0306-4522(03)00366-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groc L., Petanjek Z., Gustafsson B., Ben-Ari Y., Hanse E., Khazipov R. (2002). In vivo blockade of neural activity alters dendritic development of neonatal CA1 pyramidal cells. Eur. J. Neurosci. 16, 1931–1938 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02264.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas K., Li J., Cline H. T. (2006). AMPA receptors regulate experience-dependent dendritic arbor growth in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 12127–12131 10.1073/pnas.0602670103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen G. H., Meier E., Schousboe A. (1984). GABA influences the ultrastructure composition of cerebellar granule cells during development in culture. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2, 247–251, 253–257 10.1016/0736-5748(84)90019-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heese K., Otten U., Mathivet P., Raiteri M., Marescaux C., Bernasconi R. (2000). GABA(B) receptor antagonists elevate both mRNA and protein levels of the neurotrophins nerve growth factor (NGF) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) but not neurotrophin-3 (NT-3) in brain and spinal cord of rats. Neuropharmacology 39, 449–462 10.1016/S0028-3908(99)00166-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinen K., Baker R. E., Spijker S., Rosahl T., van Pelt J., Brussaard A. B. (2003). Impaired dendritic spine maturation in GABAA receptor alpha1 subunit knock out mice. Neuroscience 122, 699–705 10.1016/S0306-4522(03)00477-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornung J. P., Fritschy J. M. (1996). Developmental profile of GABAA-receptors in the marmoset monkey: expression of distinct subtypes in pre- and postnatal brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 367, 413–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao C. F., Wu N., Levine M. S., Chandler S. H. (2002). Development and serotonergic modulation of NMDA bursting in rat trigeminal motoneurons. J. Neurophysiol. 87, 1318–1328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagasia R., Steib K., Englberger E., Herold S., Faus-Kessler T., Saxe M., Gage F. H., Song H., Lie D. C. (2009). GABA-cAMP response element-binding protein signaling regulates maturation and survival of newly generated neurons in the adult hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 29, 7966–7977 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1054-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato-Negishi M., Muramoto K., Kawahara M., Hosoda R., Kuroda Y., Ichikawa M. (2003). Bicuculline induces synapse formation on primary cultured accessory olfactory bulb neurons. Eur. J. Neurosci. 18, 1343–1352 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02901.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khazipov R., Ragozzino D., Bregestovski P. (1995). Kinetics and Mg2+ block of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor channels during postnatal development of hippocampal CA3 pyramidal neurons. Neuroscience 69, 1057–1065 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00337-I [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleckner N. W., Dingledine R. (1991). Regulation of hippocampal NMDA receptors by magnesium and glycine during development. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 11, 151–159 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koulen P. (1999). Postnatal development of GABAA receptor beta1, beta2/3, and gamma2 immunoreactivity in the rat retina. J. Neurosci. Res. 57, 185–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leinekugel X., Medina I., Khalilov I., Ben-Ari Y., Khazipov R. (1997). Ca2+ oscillations mediated by the synergistic excitatory actions of GABA(A) and NMDA receptors in the neonatal hippocampus. Neuron 18, 243–255 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80265-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitch E., Coaker J., Young C., Mehta V., Sernagor E. (2005). GABA type-A activity controls its own developmental polarity switch in the maturing retina. J. Neurosci. 25, 4801–4805 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0172-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Morrow A. L., Devaud L., Grayson D. R., Lauder J. M. (1997). GABAA receptors mediate trophic effects of GABA on embryonic brainstem monoamine neurons in vitro. J. Neurosci. 17, 2420–2428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Neff R. A., Berg D. K. (2006). Sequential interplay of nicotinic and GABAergic signaling guides neuronal development. Science 314, 1610–1613 10.1126/science.1134246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Bendito G., Lujan R., Shigemoto R., Ganter P., Paulsen O., Molnar Z. (2003). Blockade of GABA(B) receptors alters the tangential migration of cortical neurons. Cereb. Cortex 13, 932–942 10.1093/cercor/13.9.932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lory P., Bidaud I., Chemin J. (2006). T-type calcium channels in differentiation and proliferation. Cell Calcium 40, 135–146 10.1016/j.ceca.2006.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoTurco J. J., Owens D. F., Heath M. J., Davis M. B., Kriegstein A. R. (1995). GABA and glutamate depolarize cortical progenitor cells and inhibit DNA synthesis. Neuron 15, 1287–1298 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90008-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig A., Li H., Saarma M., Kaila K., Rivera C. (2003). Developmental up-regulation of KCC2 in the absence of GABAergic and glutamatergic transmission. Eur. J. Neurosci. 18, 3199–3206 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2003.03069.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma D. K., Kim W. R., Ming G. L., Song H. (2009). Activity-dependent extrinsic regulation of adult olfactory bulb and hippocampal neurogenesis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1170, 664–673 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04373.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maric D., Liu Q. Y., Maric I., Chaudry S., Chang Y. H., Smith S. V., Sieghart W., Fritschy J. M., Barker J. L. (2001). GABA expression dominates neuronal lineage progression in the embryonic rat neocortex and facilitates neurite outgrowth via GABA(A) autoreceptor/Cl− channels. J. Neurosci. 21, 2343–2360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marty S., Berninger B., Carroll P., Thoenen H. (1996). GABAergic stimulation regulates the phenotype of hippocampal interneurons through the regulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Neuron 16, 565–570 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80075-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsutani S., Yamamoto N. (1998). GABAergic neuron-to-astrocyte signaling regulates dendritic branching in coculture. J. Neurobiol. 37, 251–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister A. K., Katz L. C., Lo D. C. (1996). Neurotrophin regulation of cortical dendritic growth requires activity. Neuron 17, 1057–1064 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80239-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta V., Sernagor E. (2006a). Early neural activity and dendritic growth in turtle retinal ganglion cells. Eur. J. Neurosci. 24, 773–786 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04933.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta V., Sernagor E. (2006b). Receptive field structure-function correlates in developing turtle retinal ganglion cells. Eur. J. Neurosci. 24, 787–794 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04971.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michler A. (1990). Involvement of GABA receptors in the regulation of neurite growth in cultured embryonic chick tectum. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 8, 463–472 10.1016/0736-5748(90)90078-G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohler H. (2007). Molecular regulation of cognitive functions and developmental plasticity: impact of GABAA receptors. J. Neurochem. 102, 1–12 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04454.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor D. E., Liu H., Wasterlain C. G. (2005). Trafficking of GABA(A) receptors, loss of inhibition, and a mechanism for pharmacoresistance in status epilepticus. J. Neurosci. 25, 7724–7733 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4944-04.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni X., Sullivan G. J., Martin-Caraballo M. (2007). Developmental characteristics of AMPA receptors in chick lumbar motoneurons. Dev. Neurobiol. 67, 1419–1432 10.1002/dneu.20517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otis T. S., Raman I. M., Trussell L. O. (1995). AMPA receptors with high Ca2+ permeability mediate synaptic transmission in the avian auditory pathway. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 482(Pt 2), 309–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overstreet-Wadiche L. S., Bromberg D. A., Bensen A. L., Westbrook G. L. (2006). Seizures accelerate functional integration of adult-generated granule cells. J. Neurosci. 26, 4095–4103 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5508-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens D. F., Boyce L. H., Davis M. B., Kriegstein A. R. (1996). Excitatory GABA responses in embryonic and neonatal cortical slices demonstrated by gramicidin perforated-patch recordings and calcium imaging. J. Neurosci. 16, 6414–6423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens D. F., Kriegstein A. R. (2002). Is there more to GABA than synaptic inhibition? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3, 715–727 10.1038/nrn919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrylo P. R., Spencer D. D., Williamson A. (2001). GABA uptake and heterotransport are impaired in the dentate gyrus of epileptic rats and humans with temporal lobe sclerosis. J. Neurophysiol. 85, 1533–1542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajan I., Cline H. T. (1998). Glutamate receptor activity is required for normal development of tectal cell dendrites in vivo. J. Neurosci. 18, 7836–7846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravindranathan A., Donevan S. D., Sugden S. G., Greig A., Rao M. S., Parks T. N. (2000). Contrasting molecular composition and channel properties of AMPA receptors on chick auditory and brainstem motor neurons. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 523(Pt 3), 667–684 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00667.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Represa A., Ben-Ari Y. (2005). Trophic actions of GABA on neuronal development. Trends Neurosci. 28, 278–283 10.1016/j.tins.2005.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds A., Brustein E., Liao M., Mercado A., Babilonia E., Mount D. B., Drapeau P. (2008). Neurogenic role of the depolarizing chloride gradient revealed by global overexpression of KCC2 from the onset of development. J. Neurosci. 28, 1588–1597 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3791-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera C., Voipio J., Payne J. A., Ruusuvuori E., Lahtinen H., Lamsa K., Pirvola U., Saarma M., Kaila K. (1999). The K+/Cl− co-transporter KCC2 renders GABA hyperpolarizing during neuronal maturation. Nature 397, 251–255 10.1038/16697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Hieber C., Jonas P., Bischofberger J. (2004). Enhanced synaptic plasticity in newly generated granule cells of the adult hippocampus. Nature 429, 184–187 10.1038/nature02553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sernagor E., Eglen S. J., Wong R. O. (2001). Development of retinal ganglion cell structure and function. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 20, 139–174 10.1016/S1350-9462(00)00024-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sernagor E., Young C., Eglen S. J. (2003). Developmental modulation of retinal wave dynamics: shedding light on the GABA saga. J. Neurosci. 23, 7621–7629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen W., Da Silva J. S., He H., Cline H. T. (2009). Type A GABA-receptor-dependent synaptic transmission sculpts dendritic arbor structure in Xenopus tadpoles in vivo. J. Neurosci. 29, 5032–5043 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5331-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sin W. C., Haas K., Ruthazer E. S., Cline H. T. (2002). Dendrite growth increased by visual activity requires NMDA receptor and Rho GTPases. Nature 419, 475–480 10.1038/nature00987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoerri P. E. (1988). Neurotrophic effects of GABA in cultures of embryonic chick brain and retina. Synapse 2, 11–22 10.1002/syn.890020104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh H., Deng W., Gage F. H. (2009). Signaling in adult neurogenesis. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 25, 253–275 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.042308.113256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syed M. M., Lee S., Zheng J., Zhou Z. J. (2004). Stage-dependent dynamics and modulation of spontaneous waves in the developing rabbit retina. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 560, 533–549 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.066597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T., Feldmeyer D., Suzuki N., Onodera K., Cull-Candy S. G., Sakimura K., Mishina M. (1996). Functional correlation of NMDA receptor epsilon subunits expression with the properties of single-channel and synaptic currents in the developing cerebellum. J. Neurosci. 16, 4376–4382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takemoto-Kimura S., Ageta-Ishihara N., Nonaka M., Adachi-Morishima A., Mano T., Okamura M., Fujii H., Fuse T., Hoshino M., Suzuki S., Kojima M., Mishina M., Okuno H., Bito H. (2007). Regulation of dendritogenesis via a lipid-raft-associated Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase CLICK-III/CaMKIgamma. Neuron 54, 755–770 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapia J. C., Mentis G. Z., Navarrete R., Nualart F., Figueroa E., Sanchez A., Aguayo L. G. (2001). Early expression of glycine and GABA(A) receptors in developing spinal cord neurons. Effects on neurite outgrowth. Neuroscience 108, 493–506 10.1016/S0306-4522(01)00348-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]