Abstract

Cleavage of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) by β- and γ-secretases results in the generation of the amyloid-β protein (Aβ), which is characteristically deposited in the brain of Alzheimer's disease (AD) patients. Inhibitors of 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl (HMG)-CoA reductase (the statins) reduce the levels of cholesterol and isoprenoids such as geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP). Previous studies have demonstrated that cholesterol increases and statins reduce Aβ levels, mostly by regulating β-secretase activity. In this study, we focused on the role of geranylgeranyl isoprenoids GGPP and geranylgeraniol (GGOH), in the regulation of Aβ production. Our data show that the inhibition of GGPP synthesis by statins plays an important role in statin-mediated reduction of Aβ secretion. Consistent with this finding, the geranylgeranyl isoprenoids preferentially increase the yield of Aβ of 42 residues (Aβ42), in a dose-dependent manner. Our studies further demonstrated that geranylgeranyl isoprenoids increase the yield of APP-CTFγ (a.k.a. AICD) as well as Aβ by stimulating γ-secretase mediated cleavage of APP-CTFα and APP-CTFβ in vitro. Furthermore, GGOH increases the levels of the active γ-secretase complex in the detergent insoluble membrane fraction along with its substrates: APP-CTFα and APP-CTFβ. Our results indicate that geranylgeranyl isoprenoids may be an important physiological facilitator of γ-secretase activity that can foster the production of the pathologically important Aβ42.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, statins, mevalonic acid, Amyloid Precursor Protein, AICD, isoprenoid

INTRODUCTION

A large body of evidence suggests that APP metabolism is affected by the alteration of the lipid microenvironment (1). The genetic link between the risk of AD and the ε4 allele of apolipoprotein E (ApoE ε4), a protein involved in lipid homeostasis, was established more than a decade ago (2-5). Epidemiological studies suggest that high levels of cholesterol associated with ApoE ε4 may contribute to the pathogenesis of AD (6, 7). More recently, epidemiological studies by several groups have shown that statins, a group of cholesterol-lowering drugs, can markedly reduce the prevalence of AD (8, 9). However, prospective clinical trials of statins for the prevention of AD will be required to confirm these findings. Multiple studies have also shown that statins modulate APP processing and reduce Aβ generation both in vitro and in vivo (9-18), suggesting that the reduction of AD prevalence may be, at least partly, the result of decreased amyloidogenic APP processing by the treatment with statins.

As discussed in a well-articulated review, a large body of literature has concluded that Aβ42 levels are specifically increased by familial AD (FAD) mutations and the currently favored hypothesis is that oligomeric forms of Aβ are responsible for neurodegeneration in AD (19). As previously reviewed by us, Aβ42 is a minor metabolite of the larger precursor protein, APP, and is generated after cleavage of APP in the ectodomain by β-secretase into sAPPβ and APP-CTFβ, and within the membrane by γ-secretase to Aβ and APP-CTFγ (a.k.a. AICD) (20). Most APP is however cleaved inside the Aβ sequence by α-secretase to sAPPα and APP-CTFα making CTFβ, and therefore Aβ, a minor metabolite of APP. Moreover, most Aβ ends at residue V40 and only a small fraction of Aβ ends at residue A42. The ratio of Aβ42/Aβ40 is however increased in cells bearing FAD mutations, suggesting that Aβ42 is the more pathologically relevant species (21). Treatment of cells with a membrane cholesterol extracting reagent results in a drastic reduction of Aβ production by inhibition of β-secretase processing (22). In addition to total cellular cholesterol, cholesterol esters have also been reported to increase the generation of Aβ (23, 24). Studies using animal models of AD, including rabbits (25, 26), transgenic mice (27-29) and guinea pigs (14), further suggest a complex relationship between plasma cholesterol levels and Aβ generation. In addition, cholesterol appears to increase CTFγ, a metabolite whose role in AD pathogenesis has been poorly studied (30).

Although cholesterol homeostasis clearly plays a role in APP metabolism, whether the cholesterol-lowering effect of statins is the only mechanism by which statins lower Aβ levels is far from established. In this regard, the protective effect of statins was found to be independent of their effect on blood cholesterol levels by one of the early reports (8), suggesting that statins may protect against AD through an alternative mechanism besides their cholesterol lowering effect. It has also been shown that brain cholesterol levels and Aβ levels in the brain are not correlated in transgenic AD mouse model treated with atorvastatin (11) or in mice genetically engineered to have low blood cholesterol levels (31). Furthermore, γ-secretase activity in the detergent insoluble membranes (DIMs; a.k.a. rafts, TIMs, DRMs) is not affected by the reduction of cholesterol levels with cholesterol extracting reagent, suggesting that the γ-secretase activity in DIMs does not depend on cholesterol level per se (32). Statins inhibit HMG-CoA reductase, and thus reduce the synthesis of mevalonic acid and several of its important metabolites including cholesterol and isoprenoids (such as GGPP and farnesyl pyrophosphate; FPP). A recent report shows that GGPP plays an important role in modulating APP processing and Aβ production by statins (33). Other reports, including one from us, have also demonstrated that GGPP preferentially increases the levels of Aβ42 rather than total Aβ, suggesting that GGPP modulates γ-secretase activity or Aβ42 turnover (34, 35). In this study, we have demonstrated that geranylgeranyl isoprenoids stimulate the processing of APP-CTFα and APP-CTFβ by modulating γ-secretase. We have also provided evidence indicating that the active γ-secretase complex is increased in DIMs by treatment with GGOH.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

All chemicals were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA) unless otherwise specified. The rabbit antibody O443 was raised against a maleimide-activated KLH-conjugated synthetic peptide (CKMQQNGYENPTYKFFEQMQN) which corresponds to the C-terminal 20 residues of APP as described previously (36). Other antibodies used were obtained commercially as follows: 6E10 (Covance, Denver, PA), anti-PS1 (Calbiochem; San Diego, CA, USA), and anti-Pen-2 (Signet, Berkeley, CA, USA), anti-nicastrin (cell signaling, Danvers, MA, USA), anti-flotillin-1 (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA); peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA). Lovastatin and simvastatin were purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, USA); ELISA kits for Aβ40 and Aβ42 detection were purchased from IBL Co. Ltd (Gunma, Japan) and Innogenetics (Ghent, Belgium), respectively.

Maintenance and treatment of cell culture

HEK 293 cells stably expressing the Swedish mutant form of APPKM670NL (HEK293-APPswe) and CHO cells stably overexpressing wild-type APP (CHO-APPwt; 2B7 a kind gift from Dr. Todd Golde) were maintained in DMEM/F12 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37 °C with 5% CO2. HEK293-APPswe cells were kept in serum-free DMEM/F12 medium with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) when they were treated with lovastatin or simvastatin for 48 h. When cells were treated with GGPP or geranylgeraniol, they were kept in DMEM/F12 with 10% FBS for 24 h. After treatment, secreted Aβ and sAPPα in media, and full-length APP and its C-terminal fragments in lysates, were quantified as previously described (36, 37).

ELISA assay for Aβ quantification

Aβ was measured using ELISA kits purchased from IBL Co. Ltd and Innogenetics according to manufacturer's protocols or an in house sandwich ELISA protocol as described previously (34). The in house assay used end-specific monoclonal antibodies 2G3 (15μg /ml) and 21F12 (5μg /ml) against Aβ40 and Aβ42, respectively for capture of the indicated analytes. A second end-specific monoclonal antibody raised against Aβ1-5 was biotinylated and used in combination with horseradish peroxidase-coupled streptavidin for detection using the chromogenic Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate.

In vitro γ-secretase assay

The efficiency of γ-secretase cleavage of APP-CTFα and APP-CTFβ after treatment with GGOH was directly determined by an in vitro γ-secretase assay as previously described (36). Briefly, cells were homogenized on ice in buffer A (50 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, and 5 mM EDTA, pH 7.4) with a Dounce homogenizer. All subsequent steps were carried out at 4°C unless otherwise indicated. Homogenates were sequentially fractionated by centrifugation at 2,500 × g for 15 min to collect unbroken cells and nuclei, and the post-nuclear supernatants were spun at 15,000 × g for 30 min. The pellets were washed once in buffer A and resuspended in buffer B (50 mM HEPES buffer, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.0, 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM PNT, and 1 mM thiorphan) and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. After incubation, the samples were chilled on ice to stop the reactions, membranes were removed by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 30 min and the final supernatants were analyzed by Western blotting for yield of APP-CTFγ.

Isolation of detergent insoluble membranes

The DIMs were prepared as described by Wada et al with minor modifications (32). All steps were carried out at 4 °C. Confluent cells from two culture plates (100 mm) were washed and scraped into ice-cold PBS and resuspended in 750 μl buffer R (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA) containing 1% CHAPSO and complete protease inhibitors (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA). After 60 min incubation on ice, the cell lysates are adjusted to 45% sucrose with 90% sucrose and placed in the bottom of a 5 ml Beckman ultra-clear centrifuge tube, and overlaid with 2 ml of 35% sucrose in buffer R, followed by 1.5 ml 5% sucrose in buffer R. After centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 16 h at 4 °C in a Beckman SW55 rotor, 10 fractions (500 μl each) were collected from the top of the gradient.

Statistics

The data are presented as Mean ± SD and analyzed by a student's two-tailed t test (p < 0.05 as significant). EC50 was calculated using the PRISM software (Graphpad).

RESULTS

Lovastatin lowers Aβ generation by blocking GGPP synthesis

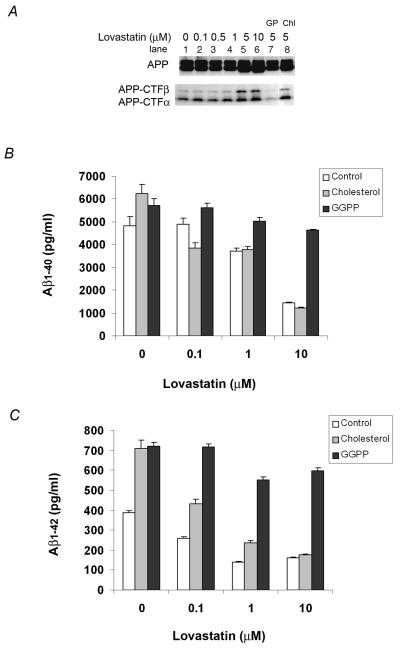

Statins inhibit HMG-CoA reductase, thereby preventing the synthesis of cholesterol and non-cholesterol isoprenoids, including GGPP. To determine the metabolite(s) responsible for the statin-mediated changes in APP processing and Aβ generation, we treated HEK293-APPswe cells with lovastatin alone or lovastatin supplemented with cholesterol or GGPP in serum free medium for 48 h. In agreement with previous reports using primary neuronal cultures as well as a similar HEK293-APPswe system (33), we found that high concentrations of lovastatin (≥5μM; 48h) caused an accumulation of the immature endoplasmic reticulum (ER) form of APP as well as both APP-CTFα and APP-CTFβ (Fig. 1A). GGPP reversed the lovastatin-mediated increase in intracellular APP-CTFs (Fig. 1A, lane 7), but cholesterol did not (Fig. 1A, lane 8). We then determined the effects of lovastatin, GGPP and cholesterol treatments of the same HEK293-APPswe cell line on Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels by ELISA analysis of media (Fig. 1B and 1C). Lovastatin caused a dose-dependent reduction in both Aβ40 and Aβ42. Cholesterol failed to block the lovastatin-mediated reduction in Aβ levels, although it increased Aβ40 as well as Aβ42 in the absence of lovastatin. In contrast, GGPP fully reversed the lovastatin-mediated reduction of both Aβ40 and Aβ42 and also substantially increased the levels of both Aβ40 and Aβ42 over statin inhibitor-free control cells. In the absence of lovastatin, GGPP increased Aβ42 levels to a greater extent than Aβ40 levels. However, in lovastatin-treated cells, GGPP increased both Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels by a similar magnitude, suggesting that the normal cellular levels of GGPP may be saturating with respect to changes in Aβ40 levels. These results suggest that the reduction in Aβ levels by lovastatin is mediated by inhibition of GGPP rather than cholesterol. In addition, although cholesterol and GGPP increase Aβ, the change is probably mediated by independent mechanisms.

Figure 1. Effects of lovastatin on the steady levels of APP-CTFs and the levels of Aβ.

HEK293-APPswe cells were treated with different doses of lovastatin alone or in combination with 200 μM cholesterol or 15 μg/ml GGPP for 48 h. A) APP and APP-CTFα and APP-CTFβ in cell lysates were detected by Western blotting with the O443 antibody against the C-terminal 20 residues of APP. In lane 7 and 8, cells were treated with 5 μM lovastatin supplemented with 15 μg/ml GGPP (GP) or 200 μM cholesterol (Chl). B) Aβ40 and C) Aβ42 in the media were measured by ELISA.

Dependence of Aβ42 generation on GGPP

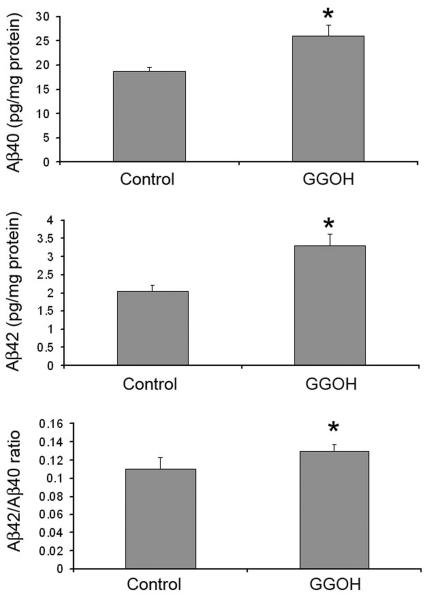

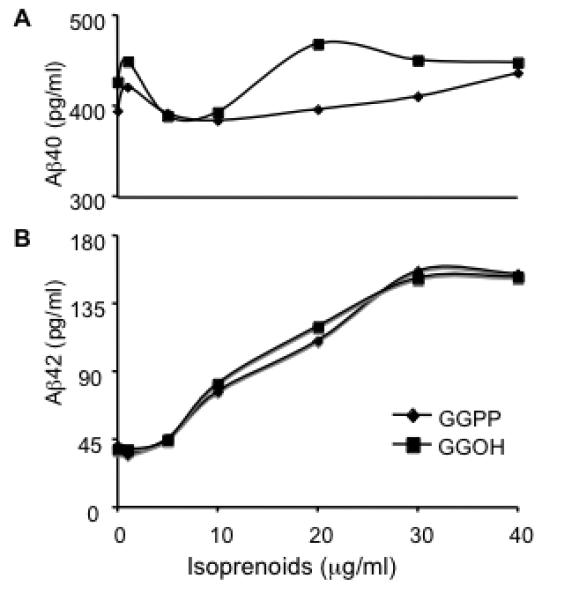

Like cholesterol, GGPP is a bioactive terminal product generated in an independent branch of the sterol/isoprenoid synthesis pathway. GGPP can also be generated from GGOH by a salvage pathway after phosphorylation by GGOH kinase (38). Thus, GGOH has been often used as a functionally equivalent reagent to restore protein prenylation in many studies (39-41). Having found that GGPP may play an important role in the statin-mediated reduction of APP processing to Aβ, we treated CHO cells transfected with wild type APP (CHO-APPwt) with different concentrations of GGPP or GGOH to determine whether the phenomenon of isoprenoid-mediated Aβ increase could be extended to wild type APP and establish a dose dependence on the levels of isoprenoid. After incubation for 24 h, conditioned media from control, GGPP and GGOH-treated CHO-APPwt cells were collected and examined for levels of Aβ40 and Aβ42 by ELISA. Both GGPP and GGOH preferentially increased Aβ42 levels in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2). The EC50s of the GGPP (MW 501.53) and GGOH (MW 290.5) mediated increase in Aβ42 were determined to be 14.5 μg/ml (28.9 μM) and 12.1 μg/ml (41.7 μM), respectively. Because the pharmacokinetic characteristics of GGPP and GGOH in modulating Aβ metabolism are similar, we chose to use GGOH for most of the subsequent experiments.

Figure 2. The concentration-dependent effect of GGPP and GGOH on Aβ generation.

CHO-APPwt cells were treated with different concentrations of GGPP or GGOH for 24 h and Aβ40 and Aβ42 in the media were measured by ELISA.

GGOH increases intracellular and secreted Aβ42

To determine if the rise in secreted Aβ levels is due to the increase in the production of Aβ, or due to the efficiency of its release from cells, we determined the levels of intracellular Aβ after GGOH treatment. Both Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels in cell lysates were increased by the treatment with GGOH with the accompanied increase in the ratio of Aβ42 to Aβ40 (Fig. 3). Since GGPP yields the same increase in intracellular Aβ as culture media, the geranylgeranyl isoprenoids, GGPP and GGOH, increase Aβ42 production rather than stimulate its release from cells.

Figure 3. The effect of GGOH on the generation of intracellular Aβ.

CHO-APPwt cultures were treated with 10 μg/ml GGOH for 24 h. Intracellular Aβ40 and Aβ42 were measured by ELISA assay of cell lysates.

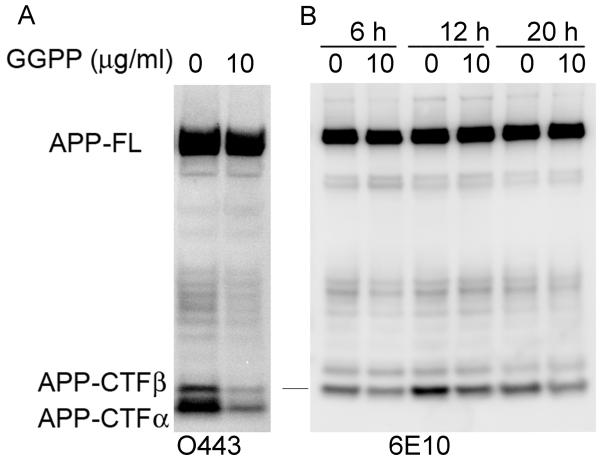

GGPP depletes APP-CTFβ and APP-CTFα

Because Aβ is a product generated by γ-secretase processing of APP-CTFβ, we examined the effect of GGPP and GGOH on the steady levels of APP-CTFβ fragments in CHO-APPwt cells. GGPP treatment reduced the cellular levels of both APP-CTFα and APP-CTFβ (Fig. 4A). This reduction in APP-CTFs was not accompanied by a change in levels of full length APP and is therefore not caused by retention of APP in early trafficking compartments or reduced APP synthesis (Fig. 4A). Similarly, a time-course study revealed that GGOH reduced the levels of APP-CTFβ as early as 6 h after the start of treatment with no visible changes in the levels of full-length APP (Fig. 4B). In conclusion, both GGPP and GGOH increased the levels of Aβ42 (Fig. 2) and decreased the steady levels of APP-CTFβ at the same time, suggesting that the increase in Aβ42 may be due to the stimulation of γ-secretase activity.

Figure 4. The effect of GGPP and GGOH on APP-CTFα and APP-CTFβ.

A) CHO-APPwt cells were treated with 15 μg/ml GGPP for 24 h. APP and APP-derived fragments in cell lysates were determined by Western blotting with O443. B) CHO-APPwt cells were treated with 10 μg/ml GGOH for different durations as indicated. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with O443 antibody, and then Western blotted with 6E10 to determine the levels of APP-CTFβ.

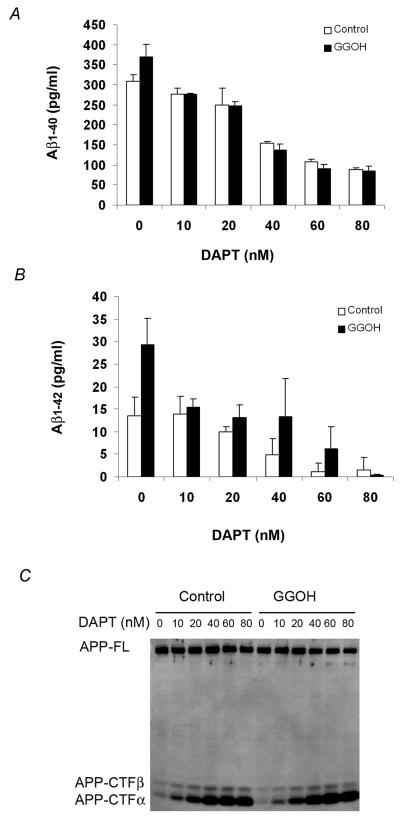

GGOH increases Aβ by stimulating γ-secretase

We observed that GGPP reduced the steady state levels of both APP-CTFα and APP-CTFβ, and at the same time preferentially increased Aβ42. These data prompted us to hypothesize that treatment of cells with geranylgeranyl isoprenoids could cause a stimulation of γ-secretase activity leading to accelerated cleavage of both APP-CTFα and APP-CTFβ and a simultaneous increase in Aβ42. To test our hypothesis that geranylgeranyl isoprenoids facilitate γ-secretase cleavage of APP, we treated CHO-APPwt cells with GGOH in the presence of different concentrations of the γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT. As expected for a γ-secretase inhibitor, DAPT inhibited Aβ40 (Fig. 5A) as well as Aβ42 (Fig. 5B) and increased APP-CTFα and APP CTFβ (Fig. 5C) in a dose-dependent manner. At a low concentration (10 nM), DAPT slightly reduced Aβ40 levels from control cells (open bars), but this reduction was more substantial in GGOH-treated cells (solid bars), effectively leveling the yield of Aβ40 in the two groups (Fig. 5A). As previously reported, DAPT preferentially inhibits Aβ40 more than Aβ42 at low concentration, with 10 nM showing no change in Aβ42 secreted from control cells (Fig. 5B). Nevertheless, even this low concentration inhibited Aβ42 from isoprenoid-treated cells by almost 50% to effectively yield the same level of Aβ42 as control cells (Fig. 5B). In summary, GGPP increases Aβ42 by stimulating γ-secretase activity and this increase can be reversed by treatment with low doses of a γ-secretase inhibitor that does not affect control cells.

Figure 5. γ-secretase-inhibitors block the GGOH-mediated increase in Aβ.

CHO-APPwt cells were treated with 0, or 10 μg/ml GGOH in the presence of different concentrations of γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT for 24 h. A) Aβ40 in the media was measured by ELISA; B) Aβ42 in the media was measured by ELISA; C) The steady levels of APP, APP-CTFα, and APP-CTFβ were determined by Western blot analysis using the O443 antibody.

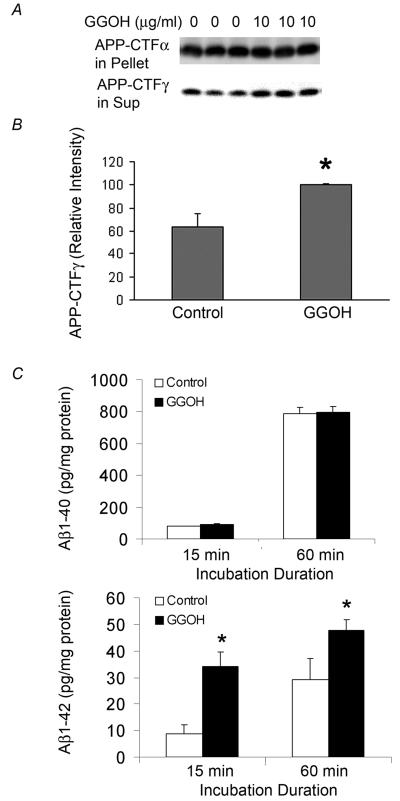

GGOH increases APP-CTFγ and γ-secretase activity

To independently confirm the stimulation of γ-secretase by GGOH treatment, we determined the yield of CTFγ in an in vitro γ-secretase assay established previously in our laboratory (36). Because treatment with GGOH reduces the intracellular levels of the APP-CTFα and APP-CTFβ substrates, the comparison of APP-CTFγ generation in vitro is likely to be compromised by the availability of substrate. We took advantage of the observation (Fig. 5C) that 50 nM DAPT equalizes CTFs in control and GGOH-treated cells to overcome this problem. Membrane fractions were prepared from cells treated with either 50 nM DAPT (control) or GGOH and 50 nM DAPT for 24 h and incubated for 1 h at 37°C as described in the Materials and Methods section. APP-CTFγ generated during incubation in vitro was used as an indicator of γ-secretase activity in the membrane preparation. After γ-secretase cleavage, APP-CTFγ is released from the membrane and can be detected in the supernatant obtained after removing the membranes by centrifugation for 30 min at 15,000 × g. The majority of APP-CTF fragments was not processed, but remained membrane bound and fractionated in the pellet. Following co-treatment with DAPT, the levels of APP-CTF fragments in the pellets of control and GGOH-treated cells were similar. However, the levels of APP-CTFγ in the supernatant, an indicator of γ-cleavage of APP-CTFs during in vitro incubation, were significantly increased in membrane preparations from GGOH-treated cells (Fig. 6A and 6B). This result shows that the generation of APP-CTFγ from the cleavage of APP-CTF fragments during in vitro incubation was accelerated by GGOH treatment in culture, strongly suggesting that GGOH treatment enhances γ-secretase activity. Measurement of Aβ generated during in vitro incubation also showed a preferential increase in Aβ42 (Fig. 6C). Taken together, these results indicated that GGOH increases Aβ generation by altering the γ-cleavage of APP-CTFβ.

Figure 6. The effect of GGOH pretreatment on in vitro γ-secretase activity.

CHO-APPwt cells were treated with 0, or 10 μg/ml GGOH in the presence of γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT for 24 h. A) Levels of APP-CTFγ generated during in vitro incubation and APP-CTFα in pellet were determined by Western blot using O443 antibody. B) The relative density of APP-CTFγ was quantified by densitometry. C) Levels of Aβ40 and Aβ42 were determined by ELISA.

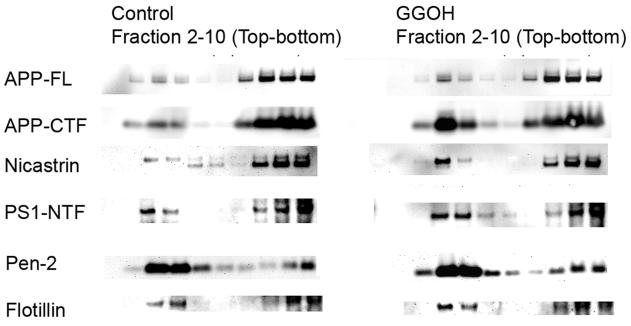

GGOH increases active γ-secretase in DIMs

Previous studies have demonstrated that γ-secretase components form an active complex that is enriched in DIMs where it interacts with the APP-CTFα/β substrate (32, 40, 42, 43). This active complex contains the mature glycosylated form of nicastrin, Pen-2, Aph1, and fragments of presenilin. Immature nicastrin stays in the dense detergent-soluble membrane fractions. To determine whether the GGOH treatment affects the incorporation of active γ-secretase complex into the DIM fraction, we examined the effect of the distribution of γ-secretase components and APP-CTF fragments in DIM after the treatment with GGOH. CHAPSO, a zwitterionic detergent commonly used to examine the association between γ-secretase components in DIMs (32, 40, 42, 43), was used in this experiment, as the detergents more commonly used for extraction of DIMs, such as Triton-X100, disrupt the γ-secretase complex leading to its inactivation. Cell cultures were treated with vehicle control or GGOH in the presence of 50 nM DAPT for 24 h in culture, homogenized in Tris-buffered saline containing 1% CHAPSO on ice and then subjected to flotation fractionation as described in Materials and Methods. As expected, flotillin, a marker of lipid rafts was found in the interface between 5% and 35% sucrose in the buoyant fractions three and four. Multiple γ-secretase components were also found in this fraction (Fig. 7). As expected, immature (core glycosylated) nicastrin, a marker of γ-secretase in early cellular compartments prior to active γ-secretase complex formation, is almost exclusively seen in the detergent soluble fractions in 45% sucrose (Fig. 7, fractions 8-10) acting as an internal control for the purity of the DIM fraction. Treatment with GGOH caused an increase in APP-CTFs in the DIM fractions compared with controls, although the levels and distribution of full length APP was not affected (Fig. 7). Because the γ-secretase-mediated processing of APP-CTF fragments was stopped by DAPT, this result may reflect an increase in γ-secretase-bound APP-CTFs cotransported into the DIM fractions by the treatment of GGOH. Moreover, mature nicastrin, pen-2, and presenilin were also increased in the DIM fractions by the treatment with GGOH, confirming an increase in levels of the active γ-secretase complex in DIMs upon treatment with GGOH (Fig. 7).

Figure 7. GGOH-induced distribution of γ-secretase and APP-CTFs in DIMs.

CHO-APPwt cells were treated with 0, or 10 μg/ml GGOH in the presence of γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT for 24 h. After treatment, cells were lysed in 1% CHAPSO, the lysates were then separated by flotation fractionation. APP, APP-CTF fragments and γ-secretase components in each fraction were detected by Western blotting.

DISCUSSION

Consistent with a recent report (33), we found that treatment of HEK293-APPswe cells with lovastatin caused an increase in the levels of intracellular APP-CTFα and APP-CTFβ, along with a decrease in the levels of Aβ in the media (Fig 1A-C). The increase in intracellular APP-CTFα and APP-CTFβ could either be due to an increase in APP-CTF production or a decrease in APP-CTF turnover. Since the levels of both APP-CTFα and APP-CTFβ are increased, the increased production of the APP-CTFs would imply an increase in both α- and β-secretase activities. Parson et al have recently shown that lovastatin and simvastatin actually inhibit the dimerization of BACE and decrease BACE activity making an increase in activity unlikely (44). We have also measured BACE activity in CHO cells after the treatment with different concentrations of lovastatin and found no increase in BACE activity (data not shown), suggesting that increased APP-CTFβ production may not be the cause of the increase in intracellular APP-CTFβ. Because both APP-CTFα and APP-CTFβ are cleaved by γ-secretase and Aβ is generated following cleavage of APP-CTFβ, an inhibition of γ-cleavage by lovastatin might explain all the changes observed following lovastatin treatment. The recovery of Aβ production as well as reversal of the lovastatin-mediated accumulation of APP-CTFα and APP-CTFβ by GGPP (Fig. 1A-C) suggests a critical role of GGPP in mediating the inhibition of Aβ production by statins. Although cholesterol can increase Aβ yield by unknown mechanisms, it failed to reverse the inhibition of Aβ production by lovastatin (Fig. 1A). Inhibition of isoprenoid synthesis by lovastatin also results in the accumulation of APP, which is reversed by GGPP. However, unlike the reduction of Aβ, the APP accumulation is only seen with the high dose of lovastatin (5 and 10 μM). We thus conclude that this accumulation of APP is a secondary response mediated by a failure of APP trafficking, which is reversed by GGPP treatment. Taken together, these data support our hypothesis that inhibition of GGPP synthesis may play a critical role in statin-mediated changes in APP-processing and Aβ generation, possibly by inhibiting γ-secretase-mediated processing of APP-CTFβ. A similar result was also obtained with FPP (data not shown), suggesting that multiple isoprenoids can foster Aβ production.

Consistent with the concept that inhibiting the synthesis of GGPP will inhibit γ-secretase activity, lovastatin treatment results in an accumulation of intracellular APP-CTFα and APP-CTFβ. Conversely, we find that addition of GGPP or its precursor GGOH reversed the increase of intracellular APP-CTFβ and APP-CTFα (Fig. 4), suggesting that inhibition of isoprenoid synthesis, rather than cholesterol, is responsible for accumulation of CTFα and CTFβ. The observation that inhibition of α-secretase by DAPT can reverse the drop in APP-CTFα and APP-CTFβ levels (Fig. 5C) further support the conclusion that the GGPP-stimulation of Aβ levels is due to increase in γ-secretase activity. Membrane preparations from cells treated with GGOH generate more APP-CTFγ than controls during in vitro incubation indicating that preconditioning of cells with GGOH treatment facilitates γ-secretase cleavage of APP-CTFα and APP-CTFβ (Fig. 6A and 6B). Since GGOH affects both CTFβ and CTFα proportionately, we expect it to also increase the γ-secretase product of CTFα – P3, as well. It will be useful to examine the changes in this peptide to analyze the trafficking and processing of APP by both α- and β-secretase pathways in future studies. Treatment with GGPP or GGOH causes a preferential increase in Aβ42 production (Fig. 2), suggesting that GGPP and GGOH favor the production of the longer, potentially pathogenic Aβ42 fragments, like a number of familial AD mutations. Taken together, our data supports the hypothesis that geranylgeranyl isoprenoids stimulate γ-cleavage of APP-CTF fragments and at the same time preferentially increase the cleavage of APP-CTFβ to Aβ42. Geranylgeranyl isoprenoids may directly modify the γ-secretase complex as previously suggested (35). Alternatively, GGPP may regulate the trafficking of APP-CTFβ and/or γ-secretase components to a specific subcellular site, where APP-CTFβ may not only be cleaved at a faster rate, but also more favorably cleaved at the site of Aβ42. Since GGOH treatment increases the levels of APP-CTFα and APP-CTFβ along with γ-secretase components into the DIM fraction, it is likely that GGPP fosters the formation and/or stabilization of the γ-secretase complex (Fig. 7). DIMs have been previously shown to be a major site for γ-cleavage of APP-CTF fragments and Aβ generation (32, 40, 42, 43). The increased partition of APP-CTF fragments into DIMs by the treatment with GGOH likely provides more substrate to the sites where active γ-secretase exists, thus facilitating the γ-cleavage of APP-CTF fragments. In addition, the incorporation of mature nicastrin and other γ-secretase components into DIMs is also increased by geranylgeraniol, suggesting an increase in the active γ-secretase complex in DIMs. This is consistent with a recent report showing that statins reduce the incorporation of γ-secretase components into DIMs at least partly through the inhibition of GGPP synthesis (40). Thus, the increased availability of GGOH to cells can both increase the incorporation of active γ-secretase complex in DIMs and the availability of its substrates. However, the exact mechanism by which GGPP mediates an increased incorporation of APP-CTF fragments and γ-secretase still needs to be identified. For example, we are currently unable to distinguish between a direct effect of GGPP incorporation into membranes and a GGPP-mediated signaling pathway. Regardless of the mechanism of stimulation, the data showing a higher yield of active γ-secretase in DIM fractions from GGOH-treated cells suggests that the ultimate result is a direct increase in levels of active γ-secretase. We have not examined the effects of GGOH on β-secretase in detail and cannot rule out multiple pleiotropic effects of GGOH, but can confirm that increase in γ-secretase is one of the affected pathways. Since GGPP treatment mimics familial AD mutations by increasing levels of Aβ42 and modulating γ-secretase, these studies may provide novel insights into the mechanisms by which these mutations increase Aβ42 and also identify potential physiological failures that can phenocopy these mutations in typical late-onset AD (19).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Ms. Christina Demos and Meera Parasuraman for help in proofreading the document and Dr. Todd Golde for kindly providing the stable CHO cell line, 2B7, expressing wild type APP. This work was supported by grants from Alzheimer's Association (NIRG-05-12773) and the National Institute of Health (AG023055 and AG028544), a grant (KS) and gift fund (YZ) from Neuroscience Education and Research Foundation (Managed by the Late Dr. Leon Thal).

REFERENCES

- 1.Sambamurti K, Granholm AC, Kindy MS, Bhat NR, Greig NH, Lahiri DK, Mintzer JE. Cholesterol and Alzheimer's disease: clinical and experimental models suggest interactions of different genetic, dietary and environmental risk factors. Curr Drug Targets. 2004;5:517–528. doi: 10.2174/1389450043345335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corder EH, Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel DE, Gaskell PC, Small GW, Roses AD, Haines JL, Pericak-Vance MA. Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer's disease in late onset families. Science. 1993;261:921–923. doi: 10.1126/science.8346443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poirier J, Davignon J, Bouthillier D, Kogan S, Bertrand P, Gauthier S. Apolipoprotein E polymorphism and Alzheimer's disease. Lancet. 1993;342:697–699. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91705-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burke JR, Roses AD. Genetics of Alzheimer's disease. Int J Neurol. 1991;26:41–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strittmatter WJ, Saunders AM, Schmechel D, Pericak-Vance M, Enghild J, Salvesen GS, Roses AD. Apolipoprotein E: high-avidity binding to beta-amyloid and increased frequency of type 4 allele in late-onset familial Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:1977–1981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jarvik GP, Wijsman EM, Kukull WA, Schellenberg GD, Yu C, Larson EB. Interactions of apolipoprotein E genotype, total cholesterol level, age, and sex in prediction of Alzheimer's disease: a case-control study. Neurology. 1995;45:1092–1096. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.6.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuo YM, Emmerling MR, Bisgaier CL, Essenburg AD, Lampert HC, Drumm D, Roher AE. Elevated low-density lipoprotein in Alzheimer's disease correlates with brain abeta 1-42 levels. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;252:711–715. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jick H, Zornberg GL, Jick SS, Seshadri S, Drachman DA. Statins and the risk of dementia. Lancet. 2000;356:1627–1631. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03155-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolozin B, Kellman W, Ruosseau P, Celesia GG, Siegel G. Decreased prevalence of Alzheimer disease associated with 3-hydroxy-3-methyglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors. Arch Neurol. 2000;57:1439–1443. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.10.1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zamrini E, McGwin G, Roseman JM. Association between statin use and Alzheimer's disease. Neuroepidemiology. 2004;23:94–98. doi: 10.1159/000073981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petanceska SS, DeRosa S, Olm V, Diaz N, Sharma A, Thomas-Bryant T, Duff K, Pappolla M, Refolo LM. Statin therapy for Alzheimer's disease: will it work? J Mol Neurosci. 2002;19:155–161. doi: 10.1007/s12031-002-0026-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parvathy S, Ehrlich M, Pedrini S, Diaz N, Refolo L, Buxbaum JD, Bogush A, Petanceska S, Gandy S. Atorvastatin-induced activation of Alzheimer's alpha secretase is resistant to standard inhibitors of protein phosphorylation-regulated ectodomain shedding. J Neurochem. 2004;90:1005–1010. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolozin B. Cholesterol and Alzheimer's disease. Biochem Soc Trans. 2002;30:525–529. doi: 10.1042/bst0300525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fassbender K, Simons M, Bergmann C, Stroick M, Lutjohann D, Keller P, Runz H, Kuhl S, Bertsch T, von Bergmann K, Hennerici M, Beyreuther K, Hartmann T. Simvastatin strongly reduces levels of Alzheimer's disease beta -amyloid peptides Abeta 42 and Abeta 40 in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:5856–5861. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081620098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buxbaum JD, Cullen EI, Friedhoff LT. Pharmacological concentrations of the HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor lovastatin decrease the formation of the Alzheimer beta-amyloid peptide in vitro and in patients. Front Biosci. 2002;7:a50–59. doi: 10.2741/A739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simons M, Schwarzler F, Lutjohann D, von Bergmann K, Beyreuther K, Dichgans J, Wormstall H, Hartmann T, Schulz JB. Treatment with simvastatin in normocholesterolemic patients with Alzheimer's disease: A 26-week randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:346–350. doi: 10.1002/ana.10292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sjogren M, Gustafsson K, Syversen S, Olsson A, Edman A, Davidsson P, Wallin A, Blennow K. Treatment with simvastatin in patients with Alzheimer's disease lowers both alpha- and beta-cleaved amyloid precursor protein. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2003;16:25–30. doi: 10.1159/000069989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ehehalt R, Keller P, Haass C, Thiele C, Simons K. Amyloidogenic processing of the Alzheimer beta-amyloid precursor protein depends on lipid rafts. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:113–123. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200207113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sambamurti K, Greig NH, Lahiri DK. Advances in the cellular and molecular biology of the beta-amyloid protein in Alzheimer's disease. Neuromolecular Med. 2002;1:1–31. doi: 10.1385/NMM:1:1:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sambamurti K, Suram A, Venugopal C, Prakasam A, Zhou Y, Lahiri DK, Greig NH. A partial failure of membrane protein turnover may cause Alzheimer's disease: a new hypothesis. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2006;3:81–90. doi: 10.2174/156720506775697142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simons M, Keller P, De Strooper B, Beyreuther K, Dotti CG, Simons K. Cholesterol depletion inhibits the generation of beta-amyloid in hippocampal neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:6460–6464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Puglielli L, Konopka G, Pack-Chung E, Ingano LA, Berezovska O, Hyman BT, Chang TY, Tanzi RE, Kovacs DM. Acyl-coenzyme A: cholesterol acyltransferase modulates the generation of the amyloid beta-peptide. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:905–912. doi: 10.1038/ncb1001-905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hutter-Paier B, Huttunen HJ, Puglielli L, Eckman CB, Kim DY, Hofmeister A, Moir RD, Domnitz SB, Frosch MP, Windisch M, Kovacs DM. The ACAT inhibitor CP-113,818 markedly reduces amyloid pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 2004;44:227–238. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sparks DL, Scheff SW, Hunsaker JC, 3rd, Liu H, Landers T, Gross DR. Induction of Alzheimer-like beta-amyloid immunoreactivity in the brains of rabbits with dietary cholesterol. Exp Neurol. 1994;126:88–94. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1994.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sparks DL, Kuo YM, Roher A, Martin T, Lukas RJ. Alterations of Alzheimer's disease in the cholesterol-fed rabbit, including vascular inflammation. Preliminary observations. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;903:335–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Refolo LM, Malester B, LaFrancois J, Bryant-Thomas T, Wang R, Tint GS, Sambamurti K, Duff K, Pappolla MA. Hypercholesterolemia accelerates the Alzheimer's amyloid pathology in a transgenic mouse model. Neurobiol Dis. 2000;7:321–331. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2000.0304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Refolo LM, Pappolla MA, LaFrancois J, Malester B, Schmidt SD, Thomas-Bryant T, Tint GS, Wang R, Mercken M, Petanceska SS, Duff KE. A cholesterol-lowering drug reduces beta-amyloid pathology in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2001;8:890–899. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2001.0422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Howland DS, Trusko SP, Savage MJ, Reaume AG, Lang DM, Hirsch JD, Maeda N, Siman R, Greenberg BD, Scott RW, Flood DG. Modulation of secreted beta-amyloid precursor protein and amyloid beta-peptide in brain by cholesterol. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:16576–16582. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.26.16576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.George AJ, Holsinger RM, McLean CA, Laughton KM, Beyreuther K, Evin G, Masters CL, Li QX. APP intracellular domain is increased and soluble Abeta is reduced with diet-induced hypercholesterolemia in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;16:124–132. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fagan AM, Christopher E, Taylor JW, Parsadanian M, Spinner M, Watson M, Fryer JD, Wahrle S, Bales KR, Paul SM, Holtzman DM. ApoAI deficiency results in marked reductions in plasma cholesterol but no alterations in amyloid-beta pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease-like cerebral amyloidosis. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1413–1422. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63399-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wada S, Morishima-Kawashima M, Qi Y, Misono H, Shimada Y, Ohno-Iwashita Y, Ihara Y. Gamma-secretase activity is present in rafts but is not cholesterol-dependent. Biochemistry. 2003;42:13977–13986. doi: 10.1021/bi034904j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cole SL, Grudzien A, Manhart IO, Kelly BL, Oakley H, Vassar R. Statins cause intracellular accumulation of amyloid precursor protein, beta-secretase-cleaved fragments, and amyloid beta-peptide via an isoprenoid-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:18755–18770. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413895200. Epub 12005 Feb 18717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou Y, Su Y, Li B, Liu F, Ryder JW, Wu X, Gonzalez-DeWhitt PA, Gelfanova V, Hale JE, May PC, Paul SM, Ni B. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can lower amyloidogenic Abeta42 by inhibiting Rho. Science. 2003;302:1215–1217. doi: 10.1126/science.1090154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kukar T, Murphy MP, Eriksen JL, Sagi SA, Weggen S, Smith TE, Ladd T, Khan MA, Kache R, Beard J, Dodson M, Merit S, Ozols VV, Anastasiadis PZ, Das P, Fauq A, Koo EH, Golde TE. Diverse compounds mimic Alzheimer disease-causing mutations by augmenting Abeta42 production. Nat Med. 2005;11:545–550. doi: 10.1038/nm1235. Epub 2005 Apr 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pinnix I, Musunuru U, Tun H, Sridharan A, Golde T, Eckman C, Ziani-Cherif C, Onstead L, Sambamurti K. A novel gamma - secretase assay based on detection of the putative C-terminal fragment-gamma of amyloid beta protein precursor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:481–487. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005968200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skovronsky DM, Doms RW, Lee VM. Detection of a novel intraneuronal pool of insoluble amyloid beta protein that accumulates with time in culture. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:1031–1039. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.4.1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ohnuma S, Watanabe M, Nishino T. Identification and characterization of geranylgeraniol kinase and geranylgeranyl phosphate kinase from the Archaebacterium Sulfolobus acidocaldarius. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1996;119:541–547. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kotti TJ, Ramirez DM, Pfeiffer BE, Huber KM, Russell DW. Brain cholesterol turnover required for geranylgeraniol production and learning in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:3869–3874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600316103. Epub 2006 Feb 3827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Urano Y, Hayashi I, Isoo N, Reid PC, Shibasaki Y, Noguchi N, Tomita T, Iwatsubo T, Hamakubo T, Kodama T. Association of active {gamma}-secretase complex with lipid rafts. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:904–912. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400333-JLR200. Epub 2005 Feb 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ownby SE, Hohl RJ. Isoprenoid alcohols restore protein isoprenylation in a time-dependent manner independent of protein synthesis. Lipids. 2003;38:751–759. doi: 10.1007/s11745-003-1123-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wahrle S, Das P, Nyborg AC, McLendon C, Shoji M, Kawarabayashi T, Younkin LH, Younkin SG, Golde TE. Cholesterol-dependent gamma-secretase activity in buoyant cholesterol-rich membrane microdomains. Neurobiol Dis. 2002;9:11–23. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2001.0470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vetrivel KS, Cheng H, Lin W, Sakurai T, Li T, Nukina N, Wong PC, Xu H, Thinakaran G. Association of gamma -secretase with lipid rafts in post-golgi and endosome membranes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:44945–44954. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407986200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parsons RB, Price GC, Farrant JK, Subramaniam D, Adeagbo-Sheikh J, Austen BM. Statins inhibit the dimerisation of beta-secretase via both isoprenoid- and cholesterol-mediated mechanisms. Biochem J. 2006;399:205–214. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]