Abstract

Recent work from our laboratory in awake behaving animals shows that olfactory bulb processing changes profoundly depending on behavioral context. Thus we show that, when recording from the olfactory bulb in a mouse during a go-no go association learning task, it is not unusual to find a mitral cell that initially does not respond to the rewarded or unrewarded odors but develops a differential response to the stimuli during the learning session. This places a challenge on how to approach understanding of olfactory bulb processing because neural interactions differ depending on the status of the animal. Here we address the question of how the different approaches to study olfactory bulb neuron responses including studies in anesthetized and unanesthetized animals in vivo and recordings in slices complement each other. We conclude that more critical understanding of the relationship between the measurements in the different preparations is necessary for future advances in the understanding of olfactory bulb processing of odor information.

A major leap in our understanding of the olfactory system was provided by the discovery of the olfactory receptor gene family which led to experiments showing that olfactory input results in a spatio-temporal odor map in the glomerular layer of the olfactory bulb that is formed by the projection of olfactory sensory neurons expressing the same olfactory receptor to a small number of glomeruli1-6. Even at the presynaptic stage, this glomerular map is not static and is influenced by active sniffing that changes drastically depending on the context the animal is in, and by centrifugal innervation7,8. To complicate matters further, the input to the olfactory system is not independent of other sensory systems because sniffing is intimately coupled with movement of the whiskers that is important in somatosensory input9. Nevertheless, it is clear that a map of odor features is found in the input to the glomerular layer of the olfactory bulb. In this respect, it can be thought that glomerular odor maps are not too different from the maps found for frequencies in the auditory system in cochlea and for space in the visual system in the retina. However, a marked difference with other sensory maps is that the relationship between the neighboring glomeruli that is relevant for downstream computation is not well-defined10,11. In other sensory systems these relationships (e.g. adjacent frequencies for the auditory system) are well defined. In contrast, although the odor maps are set up on the basis of a chemotopic map with glomeruli responding to certain chemical features found in specific regions, the relationships between these glomeruli that are relevant for processing of the incoming signal can easily change when a novel odor acquires new behavioral relevance. This raises the question of how the odor maps are transformed to mitral and tufted (M/T) cell firing which constitutes the output of the olfactory bulb, an issue that should be addressable in awake behaving recording of olfactory bulb activity.

Given the unusual anatomical connectivity of the first stages of the olfactory system including the massive centrifugal feedback to the olfactory bulb12, it is not surprising that the study of the transformation of the odor signal from the glomerular layer to the level of M/T cell firing in awake behaving animals has been marred by technical difficulties. All work in awake behaving animals at the level of the projection neurons has been done through extracellular recording in suspected mitral cells because the mitral cell layer is easily targeted by electrodes, while distinguishing tufted cell firing from firing of adjacent periglomerular cells is difficult. Pioneering work in awake behaving animals showed that responses in the olfactory bulb of the awake behaving animal are highly dependent on context13-18. Compared to work in anesthetized animals that shows robust responses of mitral cells to odors in a background of low basal firing rates19-22, in putative mitral cells in awake behaving animals firing is sparse and takes place on the background of high basal firing rates23-25. In addition, mitral cell responses to non-olfactory stimuli such as movement of the animal have been clearly documented raising the question of whether the firing of mitral cells in the olfactory bulb represents higher order processing characteristic of cortex11,23,24,26.

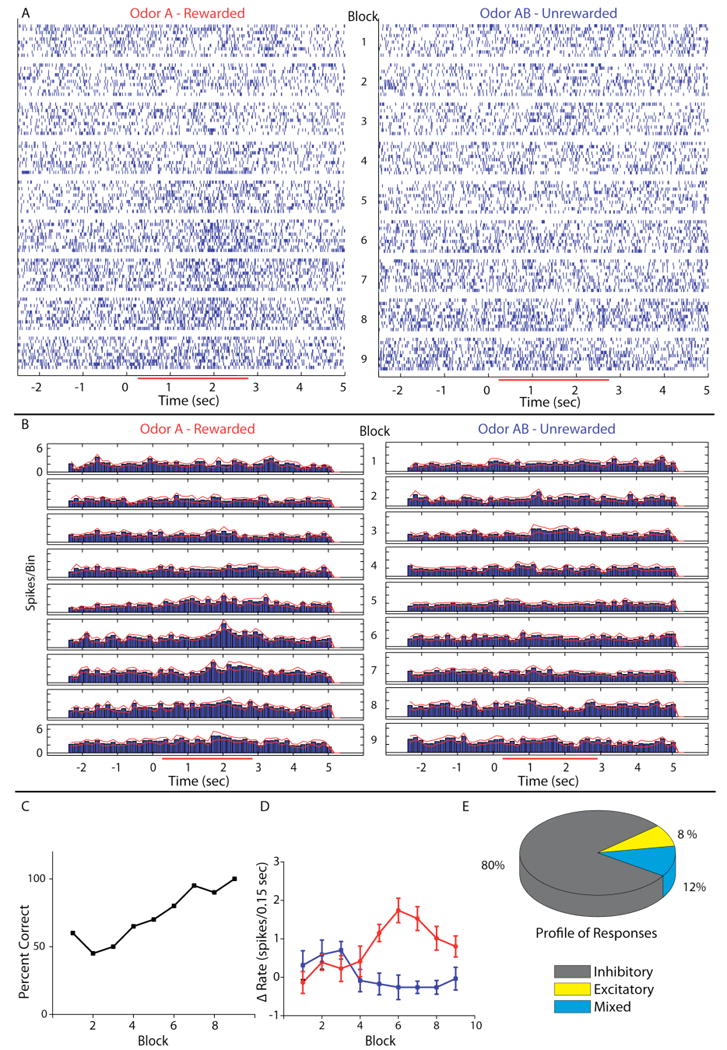

In recent work we characterized the changes in odor responsiveness of suspected mitral cells during learning to discriminate between odors in awake behaving animals27. We used microelectrode arrays with electrodes targeted to the ventral mitral cell layer of the olfactory bulb and screened multiple odors to record responses to odors during a go-no go odor discrimination learning task. Figure 1 shows that the responses of the suspected mitral cells to the two odors being discriminated by the animal (measured as changes in firing rate) become different (diverge) during the time course of the go-no go odor discrimination learning task. Thus, while in the first block of 20 trials (10 for the rewarded odor and 10 for the unrewarded odor) the responses cannot be distinguished, by the fifth block they are statistically different (Figure 1D). These changes are consistent with previous reports of changes in responsiveness during learning by Kay and Laurent24, and a recent report on differences in responses of mitral cells to odors depending on the behavioral context (active odor discrimination vs. passive odor application) by Fuentes and co-workers28.

Figure 1.

Divergence in single unit responses during learning in the odor discrimination task. A. Raster plot of single unit spike times organized per block for the 10 rewarded trials (A – left column) and 10 unrewarded trials (AB – right column). Timing and duration of odor exposure is indicated on the x-axis by the red bar in the online version and the grayscale bar in the printed version (below we denote the color in the online vs. paper versions as two colors separated by a slash: red/gray). B. Peri-stimulus time histogram (PSTH) of the data shown in A. Red/gray lines on either side of the histogram indicate +/- SEM. The bin size in the PSTH is 0.15 sec. This means that the firing rate in Hz is the value in the Y axis × (1/0.15). C. Behavioral performance – percent correct as a function of block number- for the animal from whom the cell in A and B was recorded. D. A plot of the firing rate increase above background to odor A (red/light gray) and odor AB (blue/black) in each block of the behavior. The points represent the firing rate in spikes/0.15 sec bin during odor exposure (0.5 to 2.5 sec) minus the rate in spikes/0.15 sec bin in the period immediately before odor exposure (-1 to 0 sec). Error bars denote the mean +/- SEM of each point (10 trials per point). E. The lower right hand pie chart shows what percent of the responses were inhibitory (gray/dark gray), excitatory (yellow/light gray) or mixed (blue/medium gray). A mixed response was defined as a response to either odor A or AB that had both an excitatory and inhibitory component or a response that was excitatory to one odor and inhibitory to the other odor stimulus. Taken with permission from Doucette and Restrepo (2008).

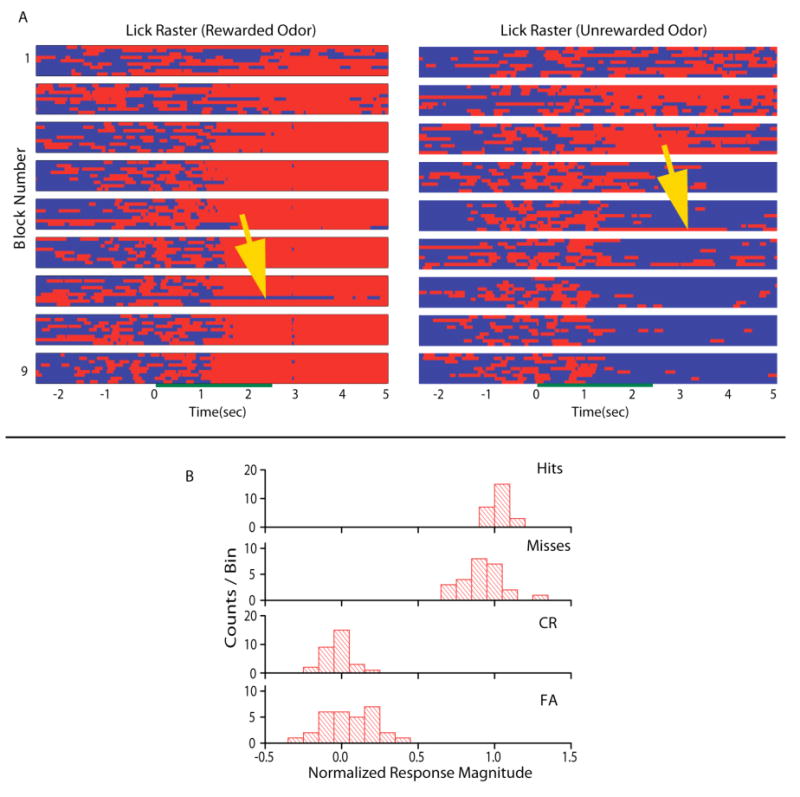

When taken together with the fact that mitral cells are known to respond to contextual events such as the nose poke in an odor discrimination task, the finding of differences in mitral cell responses in different behavioral contexts raises the question of whether those responses are bona fide odor responses as opposed to reactions to events associated with the behavioral task, such as licking for reward in our go-no go odor discrimination task. This is an important concern because it addresses the question of whether the mitral cell odor responses represent a readout of the odor map or a representation of the result of associative processing as in cortical areas in the brain26. In our study we addressed this question by determining whether the odor responses during trials when the animal made erroneous responses in the behavioral task differed from responses in trials where the animal made the correct decision27. We found that the responses of mitral cells were odor responses as opposed to responses to the behavioral events associated with each odor (Figure 2). In addition, principal component analysis of the responses of mitral cells to odors showed that the changes in firing rate are sufficient for an unbiased observer to make a decision on odor discrimination before the animal makes a behavioral decision. Thus, the readout of the odor map in the glomerular layer by mitral cells changes drastically depending on behavioral context in a way that would make it easier for the animal to discriminate between odors during learning.

Figure 2.

Lick and odor responses where the animal made correct or incorrect behavioral responses. A. Trial by trial rasters of lick behavior for the rewarded (odor A – left) and unrewarded (odor AB – right) odors. Red/light gray (online version/paper version) indicates periods of licking and blue/dark gray indicates periods of no licking. Data for ten trials are shown for rewarded and unrewarded odors per block. Blocks are arranged from top to bottom. The green/dark gray bar in the middle of the rasters indicates when the odor was delivered to the chamber. The yellow/light gray arrows point to trials where the animal made a mistake in the lick response. B. Histograms of response magnitude normalized to the average correct rewarded (1) and unrewarded (0) firing rates during the post-stimulus period sorted for the four different types of behavioral outcomes. The normalized response magnitude was calculated for each unit for all blocks in 34 experiments (from 8 animals) where the firing rate differed between unrewarded and rewarded odors in the post-stimulus period, and the animal made at least one incorrect behavioral response. Hits are trials where the animal licks sufficiently to obtain a water reward during a rewarded odor trial. Misses are trials in which the animal fails to lick sufficiently to receive reward on rewarded odor trials. Correct rejections (CR) are trials in which the animal refrains from licking during an unrewarded odor trial. False alarms (FA) are trials in which the animal responds by licking to an unrewarded odor as if it were a rewarded trial. The number of counts per bin represents the number of units displaying a response of a given normalized magnitude. Taken with permission from Doucette and Restrepo (2008).

The fact that the odor response map at the level of the mitral cell layer is highly plastic has profound implications for the understanding of processing of the odor signal in the bulb and piriform cortex. Taken together, experiments performed in awake, behaving animals make it clear that the olfactory bulb is not a structure where the signal is processed passively. Rather, it is an active filter affected by changes in sniffing and by centrifugal modulation. This poses a challenge for understanding how a particular mechanism (i.e. processing of the signal through dendrodendritic synapses) studied in in vitro preparations may or may not be relevant to the physiology of signal processing in the olfactory bulb in an unanesthetized animal. Therefore, in order to be able to understand the relevance of specific mechanisms involved in processing of signals in the olfactory bulb it is important to relate measurements made in different preparations to the function of the olfactory bulb in the awake behaving animal. Each of the different techniques (in vivo anesthetized recording, olfactory bulb slice measurements and recording from awake, behaving animals) has advantages and limitations, but the relationship of measurements made under different preparations is virtually unknown.

The anesthetized in vivo preparation has the significant advantage that cells can be readily studied using microscopy, patch clamp recording, intracellular and extracellular recording19-22,29-32, and because it is possible to test effects of a large number of odors under carefully controlled stimulus application where sniffing is monitored or controlled externally7,33. In addition, in vivo anesthetized recordings allow correlation of physiological measurements to neuroanatomical context of the neurons34-36. It is clear that ketamine/xylazine anesthesia results in a marked decrease of the basal firing rate, increase in respiration-related bursting in the firing of action potentials and increased responsiveness of the mitral cells to odors23. But, do other anesthetics produce the same effect? Indeed, how do recordings in anesthetized animals relate to the in vivo function of the olfactory bulb in unanesthetized animals? In particular, while some reports of mitral cell responsiveness under urethane appear to resemble ketamine/xylazine anesthesia20-22, other reports show some features resembling awake behaving recordings such as high basal firing rate28. How does recording under anesthetics relate to different states of consciousness in the unanesthetized animal? Recent work from Mori and co-workers shows that the strength of dendrodendritic synapses measured by surveying the effect of paired pulse stimulation of the lateral olfactory tract on the local field potential in the bulb varies drastically between different levels of urethane anesthesia and among different states in unanesthetized animals (different stages of sleep, awake immobile and awake moving) and that these differences are due to modulation through the cholinergic system37. How the function of the olfactory bulb under different states of anesthesia relates to its function under different states in the unanesthetized animal is an important unsettled question.

In the past decade, results from experiments in olfactory bulb slices have provided a substantial leap forward in our understanding of the mechanisms that underlie processing of the odor signal in the olfactory bulb38,39. Studies in the slice facilitate the use of powerful combinations of whole cell patch clamp, functional imaging and mouse genetics to answer questions about mechanisms underlying circuit processing. Yet, it is not entirely clear how the observations in slice preparations relate to the function of bulb circuitry in unanesthetized animals. Olfactory bulb slices do not have olfactory sensory neuron (OSN) input and are typically devoid of centrifugal feedback, with the possible exception (depending on how the slice was cut) of feedback from the anterior olfactory nucleus. Recent studies in awake behaving restrained animals and anesthetized animals with sniff playback have shown that active sniffing changes the input to the olfactory bulb measured at the level of the OSN terminal using calcium imaging7,8. In slices, the periodicity of the input can be mimicked by periodic stimulation of the olfactory nerve40, and although the issue of whether changes in input frequency affects processing has not been explored systematically, it should be possible to address this issue directly. On the other hand, preparation of olfactory bulb slices severs centrifugal inputs to the olfactory bulb. This is expected to have a profound effect on processing because several investigators have previously shown that interrupting centrifugal feedback by lesioning, cooling or pharmacological treatment of the olfactory peduncle results in drastic changes in physiological measures of activity in the olfactory bulb17,41-45.

The fact that the olfactory bulb slice is devoid of centrifugal input does not mean that the mechanisms studied in the slice do not apply to the awake, behaving animal. However, it is necessary to gain a better understanding of whether the mechanisms studied in the slice are modified by centrifugal innervation and periodicity of the input. For example, in a recent study Arevian and co-workers show that inhibition of mitral cell firing through the granule cell dendrodendritic circuit follows a U shaped dependence on the basal firing rate of the mitral cell46. Presumably, in the intact animal the ∼20 Hz basal firing rate would place the mitral cells at a point in this curve where there is substantial inhibition through the granule cell circuit; otherwise the granule cell circuit would be disengaged, and synchronization through the granule cells would be minimal. But, how is the influence of the granule cell circuit affected by centrifugal modulation, and how does the firing rate dependence of inhibition in the slice relate to the dependence in unanesthetized animals? Likely, the U curve is shifted by piriform and cholinergic centrifugal modulation that affects excitability of GABAergic granule cells47,48.

A particularly promising approach to understanding the role of centrifugal modulation on olfactory bulb circuits is to develop in vitro preparations that preserve centrifugal feedback such as olfactory bulb slices that include connections to piriform cortex used by Balu and co-workers47 to demonstrate that piriform cortex input onto proximal dendrites in the granule cells relieves the tonic Mg block of NMDA receptors (NMDARs) at distal synapses. A related promising preparation is brain explants. In particular, the brain explant of a zebrafish brain offers the advantage that the activity of a large number of mitral cells can be imaged simultaneously49. This has allowed Friedrich and co-workers to show that activity patterns evolve as a function of time and became more informative about precise odor identity. However, to be able to relate the studies in brain explants to the awake behaving studies the status of the centrifugal feedback must be determined/manipulated. These experiments demonstrate the need for further investigation of the relationship between olfactory bulb slices/brain explants and in vivo unanesthetized olfactory bulb physiology. Can the olfactory bulb slice/brain explant environment be changed to resemble the physiology of the unanesthetized animal?

To push the envelope in the understanding of olfactory processing it is also necessary to improve on the current methods for awake behaving recording. Advantages of awake behaving recordings are that cells are in their correct context and all inputs and circuits are intact, cellular responses can be directly related to sensory input and behavioral output. In the case of the bulb, this may be the only approach to understanding how the circuit works because the system works differently in anesthetized animals. However, there are clear disadvantages: Although the system is in a “natural” state, it is difficult to assess systematically what that state is (how much centrifugal input is coming in?). In addition, with current approaches it is difficult to manipulate the system in vivo and therefore difficult to determine mechanisms. Genetically engineered animals probed with improved in vivo physiological approaches are promising tools to help with the challenging problem of obtaining more information from awake behaving preparations in future work.

The study of olfactory bulb physiology using a multipronged approach at different levels including in vitro and in vivo preparations assisted by modeling of olfactory bulb circuitry will be needed to address fundamental questions on olfactory signal processing. Why are the basal firing rates of mitral cells in the olfactory bulb high and the odor responses sparse? Does this enable the circuit to attain stochastic resonance, a phenomenon found in other sensory systems where the presence of noise enables detection of the signal at lower levels50? Or is the higher firing rate necessary for the system to engage the granule cell circuit, and is this engagement modulated by centrifugal input? As indicated above, all measurements in awake behaving animals have been performed in suspected mitral cells. But anesthetized recordings indicate that the other projection neurons of the olfactory bulb, the tufted cells process information differently51. What information on odor stimuli are tufted cells relaying? How is odor information encoded in the mitral and tufted cells, and how is it read out in the piriform cortex and other secondary areas such as anterior olfactory nucleus, amygdala and entorhinal cortex? What is the purpose of the interplay afforded by principal cell feedback onto granule cells that takes place between piriform cortex and olfactory bulb? These are questions that will gain from synergistic approaches using different in vivo and in vitro preparations in rodents and additional studies in animals such as insects and fish where signal processing can be studied more readily in intact preparations.

References

- 1.Buck L, Axel R. A novel multigene family may encode odorant receptors: a molecular basis for odor recognition. Cell. 1991;65:175–187. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90418-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buck LB. Information coding in the vertebrate olfactory system Annu. Rev Neurosci. 1996;19:517–544. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.19.030196.002505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malnic B, Hirono J, Sato T, Buck LB. Combinatorial receptor codes for odors. Cell. 1999;96:713–723. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80581-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson BA, Leon M. Chemotopic odorant coding in a mammalian olfactory system. J Comp Neurol. 2007;503:1–34. doi: 10.1002/cne.21396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mori K, Takahashi YK, Igarashi KM, Yamaguchi M. Maps of odorant molecular features in the Mammalian olfactory bulb Physiol. Rev. 2006;86:409–433. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00021.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spors H, Wachowiak M, Cohen LB, Friedrich RW. Temporal dynamics and latency patterns of receptor neuron input to the olfactory bulb. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1247–1259. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3100-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verhagen JV, Wesson DW, Netoff TI, White JA, Wachowiak M. Sniffing controls an adaptive filter of sensory input to the olfactory bulb. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:631–639. doi: 10.1038/nn1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wesson DW, Carey RM, Verhagen JV, Wachowiak M. Rapid encoding and perception of novel odors in the rat PLoS. Biol. 2008;6:e82. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Welker WI. Analysis of sniffing of the albino rat. Behavior. 1964;22:223–244. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schoenfeld TA, Cleland TA. The anatomical logic of smell. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:620–627. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson RI, Mainen ZF. Early events in olfactory processing. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2006;29:163–201. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.112950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shepherd GM, Chen WR, Greer CA. olfactory bulb. In: Shepherd GM, editor. The Synaptic Organization of the Brain. Oxford University Press; New York: 2004. pp. 159–204. [Google Scholar]

- 13.DI Prisco GV, Freeman WJ. Odor-related bulbar EEG spatial pattern analysis during appetitive conditioning in rabbits. Behav Neurosci. 1985;99:964–978. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.99.5.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gray CM, Freeman WJ, Skinner JE. Chemical dependencies of learning in the rabbit olfactory bulb: acquisition of the transient spatial pattern change depends on norepinephrine. Behav Neurosci. 1986;100:585–596. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.100.4.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pager J. A selective modulation of the olfactory bulb electrical activity in relation to the learning of palatability in hungry and satiated rats. Physiol Behav. 1974;12:189–195. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(74)90172-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldberg SJ, Moulton DG. Olfactory bulb responses telemetered during an odor discrimination task in rats. Exp Neurol. 1987;96:430–442. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(87)90060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moulton DG. Electrical activity in the olfactory system of rabbits with indwelling electrodes. In: Zotterman Y, editor. Olfaction and Taste I. Pergamon Press; Oxford: 1963. pp. 71–84. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chaput M, Holley A. Single unit responses of olfactory bulb neurones to odour presentation in awake rabbits. J Physiol (Paris) 1980;76:551–558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harrison TA, Scott JW. Olfactory bulb responses to odor stimulation: analysis of response pattern and intensity relationships. J Neurophysiol. 1986;56:1571–1589. doi: 10.1152/jn.1986.56.6.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kashiwadani H, Sasaki YF, Uchida N, Mori K. Synchronized oscillatory discharges of mitral/tufted cells with different molecular receptive ranges in the rabbit olfactory bulb. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:1786–1792. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.4.1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yokoi M, Mori K, Nakanishi S. Refinement of odor molecule tuning by dendrodendritic synaptic inhibition in the olfactory bulb. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:3371–3375. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wellis DP, Scott JW, Harrison TA. Discrimination among odorants by single neurons of the rat olfactory bulb. J Neurophysiol. 1989;61:1161–1177. doi: 10.1152/jn.1989.61.6.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rinberg D, Koulakov A, Gelperin A. Sparse odor coding in awake behaving mice. J Neurosci. 2006;26:8857–8865. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0884-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kay LM, Laurent G. Odor- and context-dependent modulation of mitral cell activity in behaving rats. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:1003–1009. doi: 10.1038/14801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davison IG, Katz LC. Sparse and selective odor coding by mitral/tufted neurons in the main olfactory bulb. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2091–2101. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3779-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gervais R, Buonviso N, Martin C, Ravel N. What do electrophysiological studies tell us about processing at the olfactory bulb level? J Physiol Paris. 2007;101:40–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jphysparis.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Doucette W, Restrepo D. Profound Context-Dependent Plasticity of Mitral Cell Responses in Olfactory. Bulb PLoS Biol. 2008;6:2266–2285. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fuentes RA, Aguilar MI, Aylwin ML, Maldonado PE. Neuronal activity of mitral-tufted cells in awake rats during passive and active odorant stimulation. J Neurophysiol. 2008;100:422–430. doi: 10.1152/jn.00095.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schaefer AT, Angelo K, Spors H, Margrie TW. Neuronal oscillations enhance stimulus discrimination by ensuring action potential precision. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e163. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wachowiak M, Cohen LB. Correspondence between odorant-evoked patterns of receptor neuron input and intrinsic optical signals in the mouse olfactory bulb. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89:1623–1639. doi: 10.1152/jn.00747.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakashima M, Mori K, Takagi SF. Centrifugal influence on olfactory bulb activity in the rabbit. Brain Res. 1978;154:301–306. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)90702-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagayama S, Zeng S, Xiong W, Fletcher ML, Masurkar AV, Davis DJ, Pieribone VA, Chen WR. In vivo simultaneous tracing and Ca(2+) imaging of local neuronal circuits. Neuron. 2007;53:789–803. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fantana AL, Soucy ER, Meister M. Rat olfactory bulb mitral cells receive sparse glomerular inputs. Neuron. 2008;59:802–814. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin DY, Zhang SZ, Block E, Katz LC. Encoding social signals in the mouse main olfactory bulb. Nature. 2005;434:470–477. doi: 10.1038/nature03414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin DY, Shea SD, Katz LC. Representation of natural stimuli in the rodent main olfactory bulb. Neuron. 2006;50:937–949. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luo M, Katz LC. Response correlation maps of neurons in the mammalian olfactory bulb. Neuron. 2001;32:1165–1179. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00537-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsuno Y, Kashiwadani H, Mori K. Behavioral state regulation of dendrodendritic synaptic inhibition in the olfactory bulb. J Neurosci. 2008;28:9227–9238. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1576-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schoppa NE, Urban NN. Dendritic processing within olfactory bulb circuits. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:501–506. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00228-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lowe G. Electrical signaling in the olfactory bulb. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003;13:476–481. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(03)00092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schoppa NE. Synchronization of olfactory bulb mitral cells by precisely timed inhibitory inputs. Neuron. 2006;49:271–283. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gervais R. Unilateral lesions of the olfactory tubercle modifying general arousal effects in the rat olfactory bulb. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1979;46:665–674. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(79)90104-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gray CM, Skinner JE. Centrifugal regulation of neuronal activity in the olfactory bulb of the waking rabbit as revealed by reversible cryogenic blockade. Exp Brain Res. 1988;69:378–386. doi: 10.1007/BF00247583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gray CM, Freeman WJ, Skinner JE. Induction and maintenance of epileptiform activity in the rabbit olfactory bulb depends on centrifugal input. Exp Brain Res. 1987;68:210–212. doi: 10.1007/BF00255247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fischer T, Zippel HP. The effects of cryogenic blockade of the centrifugal, bulbopetal pathways on the dynamic and static response characteristics of goldfish olfactory bulb mitral cells. Exp Brain Res. 1989;75:390–400. doi: 10.1007/BF00247946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Doving KB. Efferent influence upon the activity of single neurons in the olfactory bulb of the burbot. J Neurophysiol. 1966;29:675–683. doi: 10.1152/jn.1966.29.4.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arevian AC, Kapoor V, Urban NN. Activity-dependent gating of lateral inhibition in the mouse olfactory bulb. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:80–87. doi: 10.1038/nn2030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Balu R, Pressler RT, Strowbridge BW. Multiple modes of synaptic excitation of olfactory bulb granule cells. J Neurosci. 2007;27:5621–5632. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4630-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pressler RT, Inoue T, Strowbridge BW. Muscarinic receptor activation modulates granule cell excitability and potentiates inhibition onto mitral cells in the rat olfactory bulb. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10969–10981. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2961-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yaksi E, Judkewitz B, Friedrich RW. Topological Reorganization of Odor Representations in the Olfactory Bulb PLoS. Biol. 2007;5:e178. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wiesenfeld K, Moss F. Stochastic resonance and the benefits of noise: from ice ages to crayfish and SQUIDs. Nature. 1995;373:33–36. doi: 10.1038/373033a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nagayama S, Takahashi YK, Yoshihara Y, Mori K. Mitral and tufted cells differ in the decoding manner of odor maps in the rat olfactory bulb. J Neurophysiol. 2004;91:2532–2540. doi: 10.1152/jn.01266.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]