Summary

Response regulator proteins exploit different molecular surfaces in their inactive and active conformations for a variety of regulatory intra- and/or intermolecular protein-protein interactions that either inhibit or activate effector domain activities. This versatile strategy enables numerous regulatory mechanisms among response regulators. The recent accumulation of structures of inactive and active forms of multi-domain response regulators and response regulator complexes has revealed many different domain arrangements that have provided insight into regulatory mechanisms. Although diversity is the rule, even among subfamily members containing homologous domains, several structural modes of interaction and mechanisms of regulation recur frequently. These themes involve interactions at the α4-β5-α5 face of the receiver domain, modes of dimerization of receiver domains, and inhibitory or activating hetero-domain interactions.

Introduction

The conserved features of response regulator (RR) receiver domains [1] and the enormous variety of effector domains [2] present an obvious question. How does a common receiver domain mediate phosphorylation-dependent regulation of the activities of the many structurally and functionally diverse effector domains? The answer lies in a simple and versatile strategy. The receiver domain exists in equilibrium between two predominant conformations, designated “inactive” and “active”, with phosphorylation stabilizing the active conformation. Distinct molecular surfaces in these conformations are exploited for regulatory protein-protein interactions specific to the two states.

Biochemical and genetic studies have defined the inhibitory and/or activating nature of regulatory interactions in many different RRs. In recent years, structural descriptions of multi-domain RRs and RR complexes in inactive and active states have provided details that address the molecular mechanisms underlying these regulatory interactions. With >200 RR structures deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB), it is beyond the scope of this review to comprehensively describe regulatory mechanisms of individual proteins. Examination of all available structures reveals a few general principles of regulation and several recurrent structural schemes that provide a framework for understanding and predicting regulatory strategies in different RRs. These themes are the focus of this review.

Activation via domain rearrangements

While the conformations of individual domains of RRs are only subtly different in inactive and active states, the overall structures typically differ dramatically due to different intra- and or inter-molecular domain arrangements. Interactions of receiver domains can either activate or inhibit effector domain activity as described below.

X-ray crystal structures have been central to defining domain arrangements in RRs with the caveat that complementary experiments are important for validating mechanisms suggested by structures. Crystal lattices require intermolecular contacts; not all interactions observed in crystals are physiologically relevant. Receiver domain structures recently determined by structural genomics initiatives have substantially increased the number of structures for which physiological data are lacking. No physiological significance has yet been ascribed to the several domain swapped receiver domain dimers that have been observed [3,4], likely promoted by the high protein concentrations used in crystallization. Protein concentration can also bias conformational equilibrium by promoting dimerization. Indeed, in the absence of interactions that stabilize inactive conformations, OmpR/PhoB receiver domains crystallize as active state dimers, independent of phosphorylating agents or mimics [5–7••]. Furthermore, it must be acknowledged that our structural database is biased towards constructs that have crystallized; thus RRs with flexible linkers are likely underrepresented.

The α4-β5-α5, a locus for interactions

Many structures exist of inactive and active receiver domains participating in intra- and intermolecular inhibitory and activating interactions with themselves and effector domains. In all cases for which physiological relevance is suggested, these interactions involve at minimum a subset of the α4-β5-α5 face of the receiver domain. This is not surprising because this molecular surface is the locus of the greatest differences between the inactive and active conformations [1]. Notably, the Phe/Tyr switch residue of the receiver domain often plays a prominent role, with the outward orientation of Tyr in the inactive conformation allowing stabilizing hydrogen bonds with partners. In many RRs, overlapping surfaces of the α4-β5-α5 face are used for interactions with different targets in the inactive and active states, such that each interaction is effectively a competitive inhibitor of the other. The multiplicity of potential interactions complicates design and interpretation of mutagenesis experiments.

Role of homodimerization in activation

Nearly 50% of RRs, including the OmpR/PhoB, NarL/FixJ, and LytTR subfamilies, contain only a single DNA-binding domain as the effector domain. When it was discovered that many such RRs recognize tandem or inverted repeating DNA elements for transcription regulation [8–11], RR dimerization began to emerge as an important and common regulatory theme. In many RR transcription factors, such as FixJ [12], Spo0A [13,14] and most of the OmpR/PhoB subfamily RRs from E. coli [7••, 15••, 16], phosphorylation mediates dimerization of the receiver domains, which is thought to promote DNA-binding and transcription activation. Similar strategies have also been exploited by RRs containing enzymatic GGDEF domains to bring together two bound GTP molecules for the synthesis of the second messenger, cyclic-di-GMP. Phosphorylation facilitates a monomer-dimer shift in PleD [17] or a dimer-tetramer transition in WspR [18••] to activate diguanylate cyclase activity.

Dimerization of receiver domains provides a simple means to couple the input phosphorylation with the output activity yet this mechanism can, and often does, integrate with additional regulatory strategies for more complex regulation. In some RRs from the NtrC subfamily [19••, 20, 21•], homodimers form even in the absence of phosphorylation, while phosphorylation alters the mode of dimerization to allow the oligomerization of the central ATPase domains for transcription activation.

Modes of dimerization

Given the diversity of RR domains, a great variety of interaction strategies are expected for different RRs. Many effector domains are actively involved in RR dimerization. For example, DNA binding can promote the dimerization of many RR transcription factors and a dimerizing helix has been identified in some NarL/FixJ subfamily members [22–24]. However, the majority of dimerization interfaces characterized to date are within the N-terminal receiver domain, particularly, the α4-β5-α5 region, which undergoes the largest phosphorylation-induced surface perturbations. The same region is even involved in dimerization of RRs that function independently of phosphorylation [25, 26••], reflecting an evolutionarily conserved dimerization strategy.

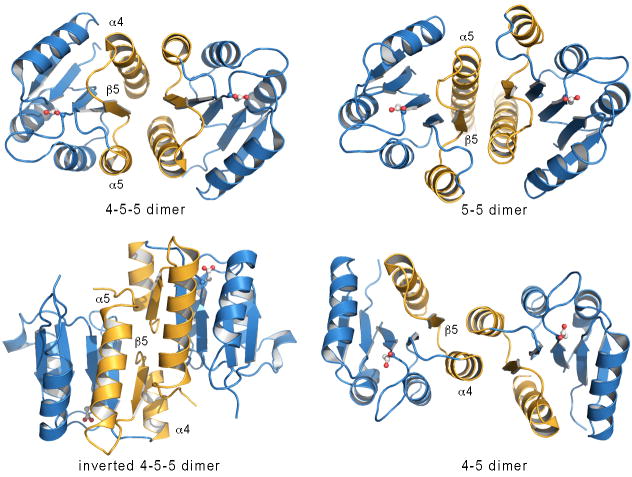

Among currently characterized dimeric RR structures, intermolecular surfaces differ among RRs and a couple of distinct dimerization modes can be readily identified based on the orientation and subsets of the α4-β5-α5 surface involved in interactions (Figure 1). The most abundant mode features a two-fold rotational symmetry with the entire α4-β5-α5 face participating in contacts with the opposite partner. This “4-5-5 dimer” is best represented by the activated receiver domains from the OmpR/PhoB subfamily [5–7••, 27••, 28], which share a conserved α4-β5-α5 face with surprisingly high sequence conservation not seen in other subfamilies. Some RRs from other subfamilies that typically do not contain all of the conserved contact residues also adopt this mode of dimerization, sometimes with skewed positioning of the secondary structural elements [21••, 29••, 30–32]. In contrast to the 4-5-5 dimer in which the two subunits run parallel, juxtaposing the C-terminal effector domains, an “inverted 4-5-5 dimer” interface with an antiparallel orientation of domains exists in three phytochrome-associated RRs from cyanobacteria [33, 34]. The physiological significance of the inverted 4-5-5 dimer is unknown, but interestingly, all occurrences involve single domain RRs that do not pose the dilemma of antiparallel positioning of effector domains.

Figure 1.

Modes of dimerization of RR receiver domains. Representative structures of commonly observed receiver domain dimers (4-5-5, PDB 1XHF; inverted 4-5-5, PDB 1K68; 5-5, PDB 2JK1; 4-5, PDB 1D5W) are shown as ribbon diagrams with the α4-β5-α5 face highlighted in gold and the Asp residue of the phosphorylation site depicted in ball-and-stick mode.

A number of dimer interactions involve subsets of the α4-β5-α5 face, such as the β5-α5 interface (“5-5 dimer”) in HupR [35•] and the α4-β5 interface (“4–5 dimer”) in phosphorylated FixJ (Figure 1) [36]. Apparently, some RRs from the NtrC subfamily assume two interchanging modes of dimerization, a 4-5-5 dimer for the unphosphorylated protein and a 4–5 dimer when phosphorylated [19••, 31, 32]. The surface plasticity might partly result from the presence of an extended α5 helix that can provide additional stabilizing interactions depending on the protein states. This feature of an extended α5 helix is also seen in some full-length RR structures from other subfamilies, such as the RNA-binding AmiR [25], StyR from the NarL/FixJ subfamily [37], and GGDEF-containing RRs, PleD and WspR [18••, 29••, 30]. As many current RR structures contain only the truncated receiver domains, the function and distribution of this extended α5 linker remain to be defined. In addition to the above dimer conformations, a small number of structures display a domain-swapped configuration [3,4] or a dimer interface involving regions other than the α4-β5-α5 face. These alternative interfaces, currently of unknown physiological relevance, further illustrate RR plasticity.

Activating strategies via hetero-domain interactions

Different protein-protein interactions involving receiver domains are the basis of RR regulation. Upon phosphorylation, the interaction partner can be the receiver domain itself, as seen in numerous RR homodimers, or a different domain. Irrespective of homo- or hetero-domain interactions, the underlying regulatory principle involves an α4-β5-α5 interaction surface that is altered by phosphorylation. One prominent case is shown by the single-domain RR, CheY, which binds the target helix from the flagellar motor protein FliM at the center of the α4-β5-α5 face [38]. In NtrC, phosphorylation promotes interaction of the receiver helix α4 with the central ATPase domain from another NtrC molecule, resulting in ring assembly and ATPase activity [39••, 40]. In receiver-truncated NtrC proteins, the central ATPase effector domain alone is not competent for oligomerization. Another intriguing example is RcsB from the NarL/FixJ subfamily. It can bind DNA either as homodimers for transcription activation, or as heterodimers with RcsA to regulate a distinct set of genes [41], although the interaction interfaces remain to be characterized.

Inhibiting strategies via hetero-domain interactions

As described above, interactions with phosphorylated receiver domains usually positively regulate effector domain activities. In contrast, hetero-domain interactions with the unphosphorylated receiver domain typically prevent effector domain activity by restricting it at an unfavorable conformation. Phosphorylation relieves inhibition by changing interactions with the altered α4-β5-α5 surface to allow effector domain function. The structural details of various inhibitory strategies have been revealed with the emergence of full-length RR structures. There is no universal inhibition mode conserved even within the same subfamily and diverse hetero-domain interactions specific to individual RRs are observed.

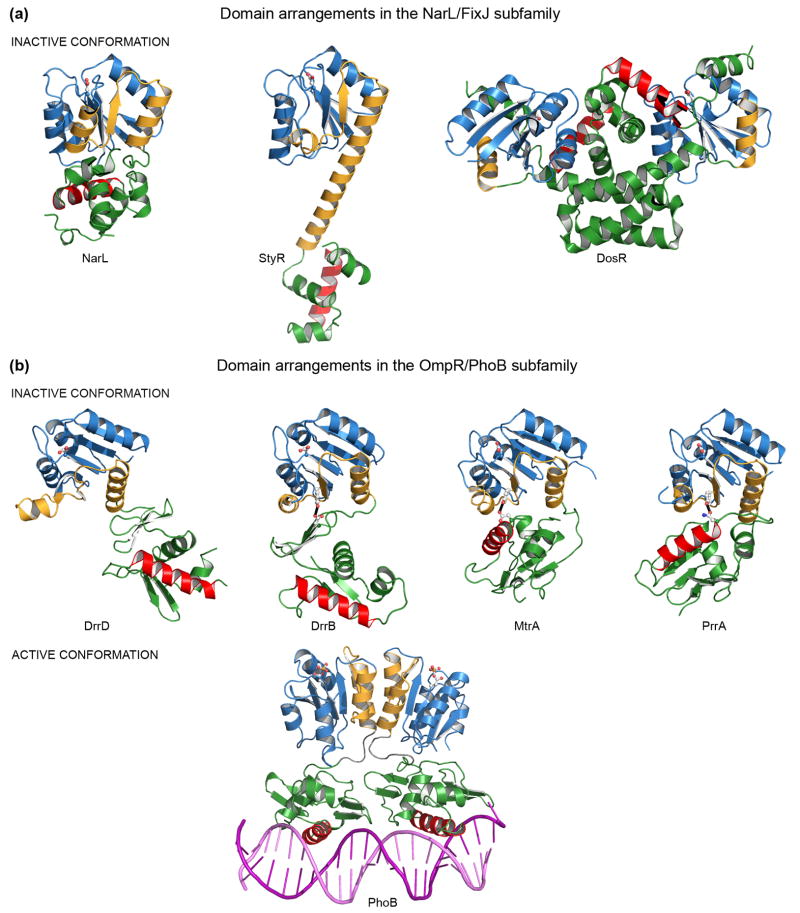

The structure of unphosphorylated NarL exhibits extensive interdomain contacts, including a linker helix interacting with both the C-terminal helix-turn-helix (HTH) domain and part of the α4-β5-α5 region in the receiver domain (Figure 2a) [42]. The rigid positioning of the two domains sterically blocks access to the DNA recognition helix.

Figure 2.

Domain arrangements in structurally characterized multi-domain RRs of the NarL/FixJ and OmpR/PhoB subfamilies. Receiver domains are colored blue with the α4-β5-α5 face highlighted in gold and the Asp residue of the phosphorylation site depicted in ball-and-stick mode. Effector domains are colored green with the DNA recognition helix highlighted in red. (a) NarL/FixJ subfamily RRs. Inactive RRs (NarL, PDB 1A04; StyR, PDB 1ZN2; DosR, PDB 3C3W) are aligned with similar orientations of their receiver domains, emphasizing differences in DNA-binding domain arrangements with an extended helix α5 in StyR and an effector domain-mediated dimer in DosR. (b) OmpR/PhoB subfamily RRs. Inactive RRs (DrrD, PDB 1KGS; DrrB, PDB 1P2F; MtrA, PDB 2GWR; PrrA, PDB 1YS6) are aligned with similar orientations of receiver domains to show the different relative orientations of the winged-helix DNA-binding domains. All RRs of the OmpR/PhoB subfamily are thought to adopt a similar domain arrangement in the active state depicted by a composite model of PhoB with active receiver domains dimerized with rotational symmetry (PDB 1ZES) joined by flexible linkers to DNA-binding domains bound to tandem repeat DNA half-sites with translational symmetry (PDB 1GXP). Interdomain hydrogen bonds involving the Tyr switch residue in the receiver domain and different residues in the effector domains are shown in DrrB, MtrA, and PrrA.

Subsequent structural analyses of StyR and DosR from the same subfamily revealed dramatic differences in inter-domain interactions, with few contacts in StyR [37] and a large interface in DosR, even at the expense of the receiver structural integrity [43••]. All three RRs are proposed to be activated by phosphorylation-induced domain rearrangements, although structural data are lacking.

Similarly, structures of four inactive OmpR/PhoB subfamily members, DrrB [44], DrrD [45], PrrA [46], and MtrA [47], also display distinct domain arrangements (Figure 2b). It appears that no significant inter-domain interaction occurs in DrrD, whereas extensive interfaces exist between the receiver and DNA-binding domains in DrrB, PrrA, and MtrA. Interfaces of the latter three are different from each other but all involve the α4-β5-α5 face that is believed to be a common dimerization interface of OmpR/PhoB subfamily RRs once phosphorylated. Therefore activation would require a disruption of the inter-domain interface to allow the formation of the active 4-5-5 dimer. Additionally, in MtrA and PrrA, the recognition helices are occluded, implicating a mutual inhibition scheme. The unphosphorylated receiver domain prevents the recognition helix from binding to DNA, and vice versa, the DNA-binding domain can stabilize the unphosphorylated inactive state of the receiver domain. Indeed, autophosphorylation of the full-length MtrA by phosphoramidate occurs much more slowly than in the isolated receiver domain [47].

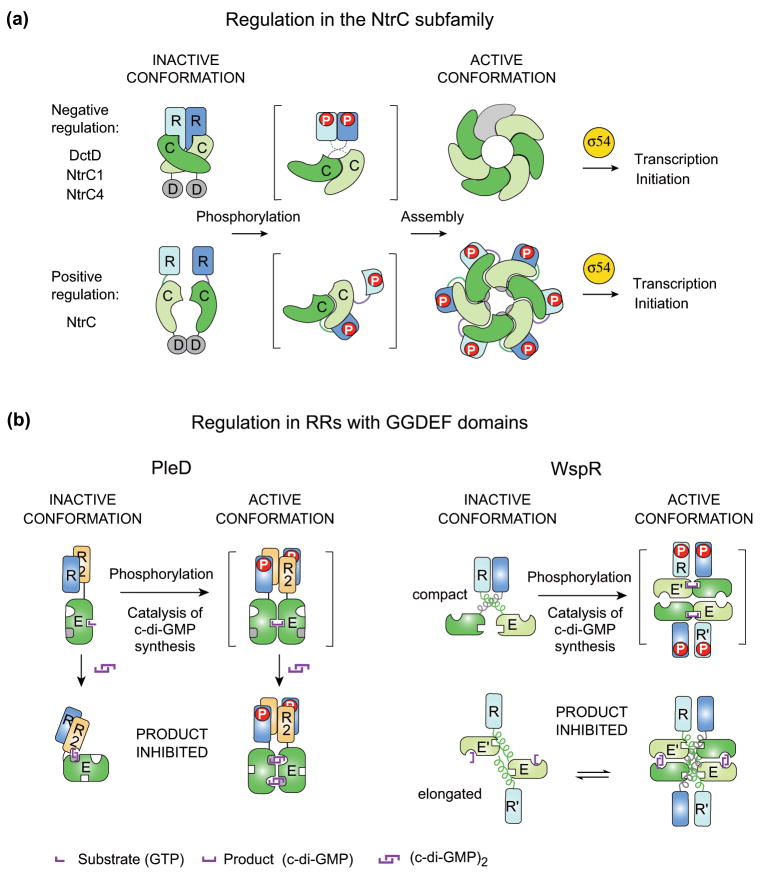

Some RRs of the NtrC subfamily, such as DctD [20, 32], NtrC1 [19••, 31], and NtrC4 [21••], utilize yet another inhibition mechanism. Unlike NtrC, they have intrinsically competent ATPase domains that are held in an inactive state by the 4-5-5 dimer of unphosphorylated receiver domains. Phosphorylation switches the dimer to a different mode, disrupting the inhibition and allowing ring assembly of the ATPase domains (Figure 3a). Although sharing a similar scheme, NtrC4 differs from the other two with somewhat different domain arrangements and weaker inhibition. In RRs containing GGDEF domains, activation relies on oligomerization to bring two active sites in close proximity for GTP condensation, while inhibition is usually mediated by the enzymatic product, c-di-GMP, through immobilization of catalytic domains in an unproductive encounter (Figure 3b) [18••, 29••, 30, 48].

Figure 3.

Regulatory strategies in RRs containing enzymatic domains. Cartoon depiction of regulatory strategies proposed from structural and biochemical studies. Cartoons in brackets represent intermediate or proposed states. (a) NtrC subfamily transcription factors. NtrC subfamily members share a common domain composition of receiver (R), AAA+ ATPase (C) and DNA-binding (D) domains. All rely on the ring assembly of ATPase domains for transcription activation. Receiver domains play a negative role in DctD, NtrC1 and NtrC4 to prevent ring formation while phosphorylated receivers in NtrC assist the assembly. (b) Diguanlyate cyclase RRs. Activation of diguanylate cyclase activity requires a close proximity of two bound GTPs on GGDEF domains (E). Phosphorylation of the receiver domain (R) mediates dimerization in PleD and a dimer-tetramer transition in WspR to allow catalysis of c-di-GMP synthesis. Diguanylate cyclase activity is subject to product inhibition by (c-di-GMP)2 via allosteric interactions. In PleD, (c-di-GMP)2 crosslinks a primary inhibition site (grey) on one GGDEF domain, with a secondary inhibition site either on the adapter domain (R2, a second receiver domain) (lower left corner of PleD panel) or on the other GGDEF domain (lower right corner of PleD panel). In WspR, product inhibition is postulated to be dependent on a tetramer that can further dissociate into elongated dimers in which the active site is blocked by the extended α5 helix.

Conclusions

Different domain arrangements in inactive and active states are the basis for a large variety of regulatory strategies for inhibiting or activating effector domain function by receiver domains. The accumulation of RR structures has revealed several conserved modes of interaction and recurrent themes for regulation. However, except for the active state of OmpR/PhoB RRs, regulatory mechanisms are not conserved in RR subfamilies. While regulatory interactions of the receiver domain uniformly involve at least a subset of the α4-β5-α5 face, the nature of these interactions shows unlimited variety, and future investigations are likely to reveal additional variations (Box 1). Thus regulatory mechanisms can be customized for individual RRs, allowing differences in relative basal (“off”) and induced (“on”) activities as well as different propensities for conversion between the two states.

Box 1. Future research questions.

* What is the repertoire of domain rearrangements that occur in multi-domain RRs and complexes upon activation?

* Can recurring regulatory strategies be classified?

* Can domain arrangements and regulatory mechanisms be predicted from sequence motifs?

* What are the roles of linker regions, especially extended α5 linkers?

* What is the physiological significance of interactions observed in crystal structures?

* Are mechanisms postulated from structures applicable in vivo?

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the NIH (R37 GM47958). AMS is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Abbreviations

- GGDEF

diguanylate cyclase catalytic domain

- RR

response regulator

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Bourret RB. Receiver domain structure and function in response regulator proteins. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2010;13 doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2010.01.015. this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galperin MY. Diversity of structure and function of response regulator output domains. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2010;13 doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2010.01.005. this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewis RJ, Muchova K, Brannigan JA, Barak I, Leonard G, Wilkinson AJ. Domain swapping in the sporulation response regulator Spo0A. J Mol Biol. 2000;297:757–770. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.King-Scott J, Nowak E, Mylonas E, Panjikar S, Roessle M, Svergun DI, Tucker PA. The structure of a full-length response regulator from Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a stabilized three-dimensional domain-swapped, activated state. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:37717–37729. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705081200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bachhawat P, Stock AM. Crystal structures of the receiver domain of the response regulator PhoP from Escherichia coli in the absence and presence of the phosphoryl analog beryllofluoride. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:5987–5995. doi: 10.1128/JB.00049-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Toro-Roman A, Wu T, Stock AM. A common dimerization interface in bacterial response regulators KdpE and TorR. Protein Sci. 2005;14:3077–3388. doi: 10.1110/ps.051722805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7••.Toro-Roman A, Mack TR, Stock AM. Structural analysis and solution studies of the activated regulatory domain of the response regulator ArcA: a symmetric dimer mediated by the α4-β5-α5 face. J Mol Biol. 2005;349:11–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.03.059. The activated receiver domain of E. coli ArcA forms a rotationally symmetric dimer mediated by a network of salt bridges between charged residues on the α4-β5-α5 face. Conservation of these residues in receiver domains of OmpR/PhoB RRs suggests a common mode of dimerization for all OmpR/PhoB subfamily transcription factors. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Makino K, Shinagawa H, Amemura M, Nakata A. Nucleotide sequence of the phoR gene, a regulatory gene for the phosphate regulon of Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1986;192:549–556. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90275-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harlocker SL, Bergstrom L, Inouye M. Tandem binding of six OmpR proteins to the ompF upstream regulatory sequence of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:26849–26856. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.26849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olekhnovich IN, Kadner RJ. Mutational scanning and affinity cleavage analysis of UhpA-binding sites in the Escherichia coli uhpT promoter. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:2682–2691. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.10.2682-2691.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohr CD, Leveau JH, Krieg DP, Hibler NS, Deretic V. AlgR-binding sites within the algD promoter make up a set of inverted repeats separated by a large intervening segment of DNA. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6624–6633. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.20.6624-6633.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Da Re S, Schumacher J, Rousseau P, Fourment J, Ebel C, Kahn D. Phosphorylation-induced dimerization of the FixJ receiver domain. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:504–511. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asayama M, Yamamoto A, Kobayashi Y. Dimer form of phosphorylated Spo0A, a transcriptional regulator, stimulates the spo0F transcription at the initiation of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. J Mol Biol. 1995;250:11–23. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewis RJ, Scott DJ, Brannigan JA, Ladds JC, Cervin MA, Spiegelman GB, Hoggett JG, Barak I, Wilkinson AJ. Dimer formation and transcription activation in the sporulation response regulator Spo0A. J Mol Biol. 2002;316:235–245. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15••.Gao R, Tao Y, Stock AM. System-level mapping of Escherichia coli response regulator dimerization with FRET hybrids. Mol Microbiol. 2008;69:1358–1372. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06355.x. Pairwise analysis of interactions among all E. coli OmpR/PhoB RRs establishes the prevalence of phosphorylation-mediated dimerization in this subfamily of transcription factors. Heterodimerization is observed for only a few specific OmpR/PhoB RR pairs, emphasizing specificity among RRs within a single organism, despite conserved sequences at the α4-β5-α5 dimer interface. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCleary WR. The activation of PhoB by acetylphosphate. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:1155–1163. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paul R, Abel S, Wassmann P, Beck A, Heerklotz H, Jenal U. Activation of the diguanylate cyclase PleD by phosphorylation-mediated dimerization. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:29170–29177. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704702200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18••.De N, Navarro MV, Raghavan RV, Sondermann H. Determinants for the activation and autoinhibition of the diguanylate cyclase response regulator WspR. J Mol Biol. 2009;393:619–633. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.08.030. Structural and biochemical analyses of Pseudomonas WspR allow postulation of a regulatory mechanism involving a product (c-di-GMP)-inhibited dimer-active tetramer equilibrium, with the latter promoted by phosphorylation. As in PleD, inhibition appears to occur through domain positioning that separates the active sites of the GGDEF catalytic domains. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19••.Doucleff M, Chen B, Maris AE, Wemmer DE, Kondrashkina E, Nixon BT. Negative regulation of AAA+ ATPase assembly by two component receiver domains: a transcription activation mechanism that is conserved in mesophilic and extremely hyperthermophilic bacteria. J Mol Biol. 2005;353:242–255. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.08.003. Structural data provide details of receiver domain interactions that underlie the inhibitory mechanism of regulation of NtrC1 activity. An alternate dimer formed by activated receiver domains disrupts an inhibitory receiver-ATPase domain interaction that buries a required oligomerization surface of the AAA+ ATPase domain in inactive NtrC1 dimers. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nixon BT, Yennawar HP, Doucleff M, Pelton JG, Wemmer DE, Krueger S, Kondrashkina E. SAS solution structures of the apo and Mg2+/BeF3−-bound receiver domain of DctD from Sinorhizobium meliloti. Biochemistry. 2005;44:13962–13969. doi: 10.1021/bi051129u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21••.Batchelor JD, Doucleff M, Lee CJ, Matsubara K, De Carlo S, Heideker J, Lamers MH, Pelton JG, Wemmer DE. Structure and regulatory mechanism of Aquifex aeolicus NtrC4: variability and evolution in bacterial transcriptional regulation. J Mol Biol. 2008;384:1058–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.10.024. Structural and biochemical characterization of NtrC4 shows that assembly into an active oligomeric state is inhibited by the unphosphorylated receiver domain, and that phosphorylation relieves this inhibition. Comparison with other NtrC subfamily members reveals both similarities and differences that provide structural and mechanistic diversity to this class of AAA+ transcription factors. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maris AE, Sawaya MR, Kaczor-Grzeskowiak M, Jarvis MR, Bearson SM, Kopka ML, Schroder I, Gunsalus RP, Dickerson RE. Dimerization allows DNA target site recognition by the NarL response regulator. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:771–778. doi: 10.1038/nsb845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wisedchaisri G, Wu M, Rice AE, Roberts DM, Sherman DR, Hol WG. Structures of Mycobacterium tuberculosis DosR and DosR-DNA complex involved in gene activation during adaptation to hypoxic latency. J Mol Biol. 2005;354:630–641. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carroll RK, Liao X, Morgan LK, Cicirelli EM, Li Y, Sheng W, Feng X, Kenney LJ. Structural and functional analysis of the C-terminal DNA binding domain of the Salmonella typhimurium SPI-2 response regulator SsrB. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:12008–12019. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806261200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Hara BP, Norman RA, Wan PT, Roe SM, Barrett TE, Drew RE, Pearl LH. Crystal structure and induction mechanism of AmiC-AmiR: a ligand-regulated transcription antitermination complex. EMBO J. 1999;18:5175–5186. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.19.5175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26••.Hong E, Lee HM, Ko H, Kim DU, Jeon BY, Jung J, Shin J, Lee SA, Kim Y, Jeon YH, et al. Structure of an atypical orphan response regulator protein supports a new phosphorylation-independent regulatory mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:20667–20675. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609104200. HP-RR, a non-canonical OmpR/PhoB RR, which lacks the conserved Asp phosphorylation site in its receiver domain, forms a stable dimer independent of phosphorylation. The dimer is similar to the active state α4-β5-α5 dimer of other OmpR/PhoB receiver domains, but is mediated by non-conserved residues at the interface. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27••.Bachhawat P, Swapna GV, Montelione GT, Stock AM. Mechanism of activation for transcription factor PhoB suggested by different modes of dimerization in the inactive and active states. Structure. 2005;13:1353–1363. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.06.006. Structures of inactive and BeF3−-activated receiver domains reveal two distinct modes of receiver domain dimerization associated with unphosphorylated and phosphorylated PhoB, both of which involve a subset of the α4-β5-α5 surface. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bent CJ, Isaacs NW, Mitchell TJ, Riboldi-Tunnicliffe A. Crystal structure of the response regulator 02 receiver domain, the essential YycF two-component system of Streptococcus pneumoniae in both complexed and native states. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:2872–2879. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.9.2872-2879.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29••.Wassmann P, Chan C, Paul R, Beck A, Heerklotz H, Jenal U, Schirmer T. Structure of BeF3−-modified response reuglator PleD: implications for diguanylate cyclase activation, catalysis, and feedback inhibition. Structure. 2007;15:915–927. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.06.016. The structure of activated Caulobacter crescentus PleD gives insight into the catalytic mechanism of GGDEF diguanylate cyclases and suggests a mechanism for phosphorylation-mediated enzyme regulation. Activated receiver domain rearrangements promote a dimerization mode that brings two catalytic domains into productive contact for condensation of two GTP molecules. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De N, Pirruccello M, Krasteva PV, Bae N, Raghavan RV, Sondermann H. Phosphorylation-independent regulation of the diguanylate cyclase WspR. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e67. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee SY, De La Torre A, Yan D, Kustu S, Nixon BT, Wemmer DE. Regulation of the transcriptional activator NtrC1: structural studies of the regulatory and AAA+ ATPase domains. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2552–2563. doi: 10.1101/gad.1125603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park S, Meyer M, Jones AD, Yennawar HP, Yennawar NH, Nixon BT. Two-component signaling in the AAA+ ATPase DctD: binding Mg2+ and BeF3− selects between alternate dimeric states of the receiver domain. FASEB J. 2002;16:1964–1966. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0395fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Im YJ, Rho SH, Park CM, Yang SS, Kang JG, Lee JY, Song PS, Eom SH. Crystal structure of a cyanobacterial phytochrome response regulator. Protein Sci. 2002;11:614–624. doi: 10.1110/ps.39102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benda C, Scheufler C, Tandeau de Marsac N, Gartner W. Crystal structures of two cyanobacterial response regulators in apo- and phosphorylated form reveal a novel dimerization motif of phytochrome-associated response regulators. Biophys J. 2004;87:476–487. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.033696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35•.Davies KM, Lowe ED, Venien-Bryan C, Johnson LN. The HupR receiver domain crystal structure in its nonphospho and inhibitory phospho states. J Mol Biol. 2009;385:51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.10.027. Structures of isolated receiver domains have provided insight into dimerization modes in this unconventional NtrC subfamily transcription factor that is inactivated by phosphorylation. Cryo-electron micrographs have allowed modeling of domain arrangements in the intact protein, but the oligomeric states of the full-length protein and their function in transcription activation remain to be determined. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Birck C, Mourey L, Gouet P, Fabry B, Schumacher J, Rousseau P, Kahn D, Samama J-P. Conformational changes induced by phosphorylation of the FixJ receiver domain. Structure Fold Des. 1999;7:1505–1515. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)88341-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Milani M, Leoni L, Rampioni G, Zennaro E, Ascenzi P, Bolognesi M. An active-like structure in the unphosphorylated StyR response regulator suggests a phosphorylation-dependent allosteric activation mechanism. Structure. 2005;13:1289–1297. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee S-Y, Cho HS, Pelton JG, Yan D, Henderson RK, King DS, Huang L-S, Kustu S, Berry EA, Wemmer DE. Crystal structure of an activated response regulator bound to its target. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:52–56. doi: 10.1038/83053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39••.De Carlo S, Chen B, Hoover TR, Kondrashkina E, Nogales E, Nixon BT. The structural basis for regulated assembly and function of the transcriptional activator NtrC. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1485–1495. doi: 10.1101/gad.1418306. Docking of individual domain models into structures derived from small- and wide-angle X-ray scattering and electron microscopy define the domain organization in ring assemblies of NtrC. The structural and previous biochemical data allow a detailed model for AAA+ ATPAse ring assembly that establishes the mechanism for positively regulated activation of NtrC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee J, Owens JT, Hwang I, Meares C, Kustu S. Phosphorylation-induced signal propagation in the response regulator NtrC. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:5188–5195. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.18.5188-5195.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pristovsek P, Sengupta K, Lohr F, Schafer B, von Trebra MW, Ruterjans H, Bernhard F. Structural analysis of the DNA-binding domain of the Erwinia amylovora RcsB protein and its interaction with the RcsAB box. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:17752–17759. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301328200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baikalov I, Schröder I, Kaczor-Grzeskowiak M, Grzeskowiak K, Gunsalus RP, Dickerson RE. Structure of the Escherichia coli response regulator NarL. Biochemistry. 1996;35:11053–11061. doi: 10.1021/bi960919o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43••.Wisedchaisri G, Wu M, Sherman DR, Hol WG. Crystal structures of the response regulator DosR from Mycobacterium tuberculosis suggest a helix rearrangement mechanism for phosphorylation activation. J Mol Biol. 2008;378:227–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.02.029. Structures of a full-length NarL subfamily transcription factor DosR reveal an unusual β4α4 fold for the receiver domain. Dimerization is mediated by two linker helices in each protomer that participate in a four-helix bundle domain interface. In inactive DosR, interdomain contacts include an interaction between helix α10 of the effector domain and Asp54 at the phosphorylation site of the receiver domain. Phosphorylation-mediated activation of DosR is proposed to involve disruption of this contact and rearrangement of helix α10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robinson VL, Wu T, Stock AM. Structural analysis of the domain interface in DrrB, a response regulator of the OmpR/PhoB subfamily. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:4186–4194. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.14.4186-4194.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buckler DR, Zhou Y, Stock AM. Evidence of intradomain and interdomain flexibility in an OmpR/PhoB homolog from Thermotoga maritima. Structure. 2002;10:153–164. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00706-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nowak E, Panjikar S, Konarev P, Svergun DI, Tucker PA. The structural basis of signal transduction for the response regulator PrrA from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9659–9666. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512004200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Friedland N, Mack TR, Yu M, Hung L-W, Terwilliger TC, Waldo GS, Stock AM. Domain orientation in the inactive response regulator Mycobacterium tuberculosis MtrA provides a barrier to activation. Biochemistry. 2007;46:6733–6743. doi: 10.1021/bi602546q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schirmer T, Jenal U. Structural and mechanistic determinants of c-di-GMP signalling. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:724–735. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]